James Maliszewski's Blog, page 73

June 15, 2023

Creating Fonts

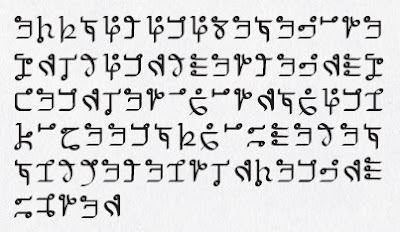

How difficult is it to create a font set from a set of characters? I ask because, with the help of Zhu Bajiee, there is now a script for the Onha language of my

Secrets of sha-Arthan

setting and I'd like to make wide use of it in the production of the game. Having a custom Onha font set would help with this considerably.

How difficult is it to create a font set from a set of characters? I ask because, with the help of Zhu Bajiee, there is now a script for the Onha language of my

Secrets of sha-Arthan

setting and I'd like to make wide use of it in the production of the game. Having a custom Onha font set would help with this considerably.However, as is usually the case in these matters, my technical know-how is exceedingly limited. I don't know the first thing about the creation of fonts, which is why I'm prevailing upon my readers to point me in the right direction.

Thanks in advance!

June 13, 2023

Retrospective: The Throne of Bloodstone

While I unqualifiedly count myself as a fan of the articles Ed Greenwood wrote about his home campaign, the Forgotten Realms, in the pages of Dragon, my feelings about TSR's version of it are decidedly more mixed. For the most part, the original boxed campaign setting developed by Jeff Grubb and published in 1987 is quite good, retaining most of the elements that, I think, made the Realms unique, or at least distinct from previous TSR AD&D settings, like

The World of Greyhawk

or Krynn. However, a lot of the products later released under the Forgotten Realms banner did not, in my opinion, jibe well with Greenwood's vision for his setting, no doubt because TSR saw the Realms as a "kitchen sink" setting where anything that was possible under the AD&D could be found somewhere.

While I unqualifiedly count myself as a fan of the articles Ed Greenwood wrote about his home campaign, the Forgotten Realms, in the pages of Dragon, my feelings about TSR's version of it are decidedly more mixed. For the most part, the original boxed campaign setting developed by Jeff Grubb and published in 1987 is quite good, retaining most of the elements that, I think, made the Realms unique, or at least distinct from previous TSR AD&D settings, like

The World of Greyhawk

or Krynn. However, a lot of the products later released under the Forgotten Realms banner did not, in my opinion, jibe well with Greenwood's vision for his setting, no doubt because TSR saw the Realms as a "kitchen sink" setting where anything that was possible under the AD&D could be found somewhere. This desire to reshape the Forgotten Realms into something more generic (or perhaps utilitarian) was obvious from the very beginning, even in the '87 boxed set. In his introduction from that set, Jeff Grubb points out the various ways Greenwood's Realms were changed to accommodate the ideas of others, such as the fact that "the land that is now Vaasa and Damara was only recently (in game design terms) covered by an unnatural glacier." Vaasa and Damara, you may recall, made their first appearance before the publication of the Forgotten Realms boxed set, in 1985's Bloodstone Pass. That module, written by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson, was itself intended to support the Battle System miniatures rules, as were its two immediate sequels, The Mines of Bloodstone (1986) and The Bloodstone Wars (1987).

By design, the setting presented in Bloodstone Pass is vanilla fantasy that could easily be dropped into any campaign setting. That's not a criticism and, from a sales point of view, was probably a point in its favor, broadening its pool of potential customers. With the publication of the Forgotten Realms in 1987, though, TSR found a way to cram a lot of stuff into it, in the process diluting its uniqueness. That's why the campaign box set pushes back the Great Glacier and plops Vaasa and Damara into the ice-free real estate so revealed. This change struck me then, as it does now, as utterly unnecessary, since there was nothing about the Bloodstone Lands that felt as if they could be part of the Realms. But commerce pays no heed to esthetics and I doubt anyone at TSR at the time worried about such trivial concerns.

Which brings us to the fourth and final module in the H-series: The Throne of Bloodstone. Written, like all its predecessors, by Niles and Dobson, and published in 1988, module H4 was, then and now, notorious among AD&D fans, for its stated level range – 18–100. You read that correctly; this adventure was explicitly presented as a challenge for 100th-level characters. There are even sample characters of this level provided at the end of the book, in addition to a few pages of advice to the Dungeon Master on running characters of such stratospheric levels of experience.

Why, you might ask, did the module do this? What sort of challenge could possibly justify the need for such potent characters? To start, the characters are tasked with defeating the Witch-King Zhengyi of Vaasa, a 30th-level magic-using lich who, it is revealed, is a devotee of the demon lord Orcus. In the course of this task, the characters discover a gate that leads to the Abyss, the outer planar home not only of the Lord of the Undead but of all the demon lords and princes. Traveling there to do battle with the forces of Chaotic Evil might well be a task worthy of 100th-level characters, but why go there at all, especially if the threat of Zhengyi were already eliminated?

That's where Throne of Bloodstone takes a very odd turn. Not long after discovering the gate, "a short, stocky little man with huge angel's wings wearing white robes" appears. Did I mention he also "calmly puffs on a cigar?" This is St. Sollars, a minor deity introduced all the way back in Bloodstone Pass. He speaks to the characters – in a strange Bugs Bunny-style Brooklyn accent – and explains that "the big boss, ol' Bahamut, don't much like Orcus," whom he calls "the meanest dude this side o' the Pecos." The Platinum Dragon would like the characters to help him deal with Orcus by "corral[ing] that big skull stick o' his," which is to say, he wants them to steal the wand of Orcus.

The whole thing is beyond bizarre – especially St. Sollars, who feels like he's walked in from a completely different roleplaying game (or maybe Dave Trampier's Wormy). I honestly have no idea how to take all of this. Is it meant tongue in cheek, a kind of verbal winking at the players and the DM, since the very idea of 100th-level adventure is already somewhat absurd? Is this some sort of cryptic allusion that simply escapes me? I just don't know, but then my sense of humor is notoriously lacking. Whatever it means, the task St. Sollars offers the characters sets up the remainder of the module, which is vast in its scope.

The characters pass through the gate and arrive in Pazunia, the first layer of the Abyss. From there, they must make their way – somehow – to the layer ruled by Orcus. Doing so is, naturally, a very dangerous endeavor, since they must pass through many, many other layers to reach their final destination. The result is a kind of tour of the Abyss, with stops at the realms of Demogorgon, Yeenoghu, Lolth, Juiblex, Baphomet, Graz'zt, and so many more. What's interesting is that, while the characters can do battle with many of these fiendish AD&D luminaries, they can also parley with some of them, perhaps even ally with them, since they, too, have bones to pick with Orcus.

As I said, Throne of Bloodstone is vast in scope. The characters, even 100th-level ones, could spend an immense amount of time traveling, exploring, fighting, and negotiating on the various levels of the Abyss that are lightly detailed in this module. It's practically a campaign in itself – and it all happens before the characters even reach the plane of Orcus. Once there, the challenges are immense, with undead beings everywhere, in addition to the requisite demons and, of course, Orcus himself. It's genuinely awe-inspiring, the kind of thing that many an AD&D no doubt dreamed of one day doing with his high-level character.

The problems with Throne of Bloodstone are many, starting most obviously with whether it's even possible to run a game at this level. I'm not saying it isn't, only that I do not know and I suspect that neither do Douglas Niles or Michael Dobson – or indeed anyone else. That's one of the other problems: was this ever playtested? Does that even matter? Sometimes, the strength of a module's ideas are what matter and there's certainly a lot of interesting, or at least inspiring, ideas in this one. Of course, most of those ideas are barely detailed. Throne of Bloodstone is more of a sketch of a lengthy, high-level mini-campaign than an adventure module in the traditional sense.

That's why it's well nigh impossible to judge this thing. I have never played it and, for years, I scoffed at it, citing it as an example of just how much AD&D had lost its way by the late '80s. Nowadays, I am not so sure. Throne of Bloodstone is such a strange, wonderful, contradictory mess. Everything about it, from its premise to its contents is, on first blush, quite laughable and yet, having re-read it in preparation for this post, I can't simply dismiss it out of hand. Certainly, it'd require a lot work on the part of the DM to use effectively and, even then, I am not sure it could ever work in practice as well as I imagine it could – but it might be worth a try ... ?

June 11, 2023

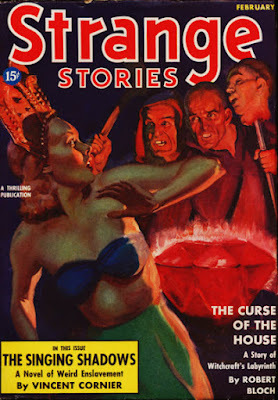

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Sorcerer's Jewel

Nowadays, Robert Bloch is best known for his authorship of the 1959 novel, Psycho, memorably made into a film by Alfred Hitchcock the following year. However, Bloch had a long and successful career as a writer of pulp stories, starting "The Feast in the Abbey," which appeared in the January 1935 of Weird Tales. Much of his earliest work is strongly influenced by that of H.P. Lovecraft, whom he considered his mentor and friend. Though the two writers never met, they began a correspondence in 1933 that would last until HPL's death in 1937, when Bloch was only 20 years old.

Nowadays, Robert Bloch is best known for his authorship of the 1959 novel, Psycho, memorably made into a film by Alfred Hitchcock the following year. However, Bloch had a long and successful career as a writer of pulp stories, starting "The Feast in the Abbey," which appeared in the January 1935 of Weird Tales. Much of his earliest work is strongly influenced by that of H.P. Lovecraft, whom he considered his mentor and friend. Though the two writers never met, they began a correspondence in 1933 that would last until HPL's death in 1937, when Bloch was only 20 years old.A great deal of Bloch's Lovecraftian stories could, in charity, be called pastiches. Like August Derleth, whom Bloch did meet (largely because they lived only about 100 miles apart), Bloch's juvenile writings include lots of unnecessary allusions and references to Lovecraft's various alien gods and entities. Bloch was particularly fond of Nyarlathotep, writing several stories that feature the Crawling Chaos or his mortal agents. Flawed though they are, many of these stories nevertheless feature intriguing concepts and situations that provide glimpses into the writer Bloch would one day become.

One Bloch's better early stories in my opinion is "The Sorcerer's Jewel," which first appeared in the February 1939 issue of Strange Stories (which also featured another tale by Bloch, "The Curse of the House," in the same issue). To some degree, that's because the story is only tangentially connected to the Cthulhu Mythos and that gives Bloch some space to develop his own ideas more fully. And while those ideas certainly owe a debt to Lovecraft, notably the short story, "From Beyond," Bloch makes them him own.

The story begins memorably.

By rights, I should not be telling this story. David is the one to tell it, but then, David is dead. Or is he?

That's the thought that haunts me, the dreadful possibility that in some way David Niles is still alive-in some unnatural, unimaginable way alive. That is why I shall tell the story; unburden myself of the onerous weight which is slowly crushing my mind.

David Niles, we soon learn, was a photographer, as well as the roommate of the unnamed narrator. We also learn that Niles was

a devotee of the William Mortensen school of photography. Mortensen, of course, is the leading exponent of fantasy in photography; his studies of monstrosities and grotesques are widely known. Niles believed that in fantasy, photography most closely approximated true art. The idea of picturing the abstract fascinated him; the thought that a modern camera could photograph dream worlds and blend fancy with reality seemed intriguing.

This devotion on the part of Niles is why he had chosen the narrator as his roommate: he was a student of metaphysics and the occult and could serve as his "technical advisor" as he quested discover "the soul of fantasy" through photography. Initially, Niles attempts to do this through the use of "photographic makeup" on "models whose features lent themselves to the application of gargoylian disguises." Later, he tries his hand at models crafted from clay and placed in elaborate papier-mâché sets. Both approaches disappoint him.

"I've been on the wrong track," he declared. "If I photograph things as they are, that's all I'm going to get. I build a clay set, and by Heaven, when I photograph it, all I can get is a picture of that clay set – a flat, two-dimensional thing at that. I take a portrait of a man in makeup and my result is a photo of a man in makeup. I can't hope to catch something with the camera that isn't there. The answer is – change the camera. Let the instrument do the work."

Niles then opts for another approach: the use of new camera lenses, some of which he ground himself, hoping that he might be able to see something different through their use. With time, his efforts begin to pay off, producing "startling" results.

"Splendid," he gloated. "It all seems to tie in with the accepted scientific theories, too. Know what I mean? The Einsteinian notions of coexistence; the space-time continuum ideas."

"The Fourth Dimension?" I echoed.

"Exactly. New worlds all around us-within us. Worlds we never dream of exist simultaneously with our own; right here in this spot there are other existences. Other furniture, other people, perhaps. And other physical laws. New forms, new color."

"That sounds metaphysical to me, rather than scientific," I observed. "You're speaking of the Astral Plane-the continuous linkage of existence."

Being "a skeptic, a materialist, and, above all, a scientist," Niles is quite dismissive of the narrator's occult notions, calling them "the psychological lies of dementia praecox victims." This raises the narrator's hackles. He launches first into a discussion of "crystal-gazing," the means by which "men have peered into the depths of precious stones, gazed through polished, specially cut and ground glasses, and seen new worlds." He even attempts to back up his claims by reference to the laws of optics, stating that "the phenomenon of sight has very little to do with either actual perception or the true laws of light."

The narrator offers to prove his point to Niles by visiting his friend, Isaac Voorden who has "some Egyptian crystals" once used seers for divination purposes. He proposes to then have Niles gaze into the crystals himself, where he might see things "you and your scientific ideas won't so readily explain." Unexpectedly, Niles agrees to this proposition.

The next day, the narrator visits his Voorden's antiques shop, where he had also collected "statuettes, talismans, fetishes and other paraphernalia of wizardry." After explaining what he wanted and why, Voorden admit that he had a stone that "should prove eminently suitable."

The Star of Sechmet. Very ancient, but not costly. Stolen from the crown of the Lioness-headed Goddess during a Roman invasion of Egypt. It was carried to Rome and placed in the vestal girdle of the High-Priestess of Diana. The barbarians took it, cut the jewel into a round stone. The black centuries swallowed it.

"But it is known that Axenos the Elder bathed it in the red, yellow and blue flames, and sought to employ it as a Philosopher's Stone. With it he was reputed to have seen beyond the Veil and commanded the Gnomes, the Sylphs, the Salamanders, and the Undines. It formed part of the collection of Gilles De Rais, and he was said to have visioned within its depths the concept of Homonculus. It disappeared again, but a monograph I have mentions it as forming part of the secret collection of the Count St. Germain during his ritual services in Paris. I bought it in Amsterdam from a Russian priest whose eyes had been burned out by little gray brother Rasputin. He claimed to have divinated with it and foretold –"

I broke in again at this point. "You will cut the stone so that it may be used as a photographic lens, then," I repeated. "And when shall I have it?"

The Star of Sechmet is "the Sorcerer's Jewel" of the title and, unsurprisingly, it works every bit as well as the narrator had hoped and indeed more so – as David Niles soon finds out at the cost of his sanity and his life.

Since I've included a link to the entire text of the story, I won't say any more about its plot. I doubt anyone familiar with this type of horror tale will be surprised by anything that occurs, but I think Bloch presents it in a compelling and enjoyable way. As I have written many times before in this space, originality is often overvalued, especially when compared to execution. I've reached the point in my life where I am rarely impressed by mere novelty and care far more about the skill with which a familiar story or concept is employed. By that criterion, "The Sorcerer's Jewel" is well worth a read.

June 8, 2023

Manual of Fear and Death

The first AD&D book I ever owned was the Monster Manual. I bought it with money my grandmother had given me for Christmas 1979, ordering it through the Sears catalog. Once my copy arrived, sometime in early January 1980, I spent untold hours poring over its contents. Though I, of course, loved all the descriptive material contained in the book's 112 pages, it was the illustrations that truly seized my imagination – so much so that, to this day, it's difficult to conceive of many Dungeons & Dragons monsters in any way other than how Dave Sutherland, Dave Trampier, Tom Wham, and Jean Wells drew them.

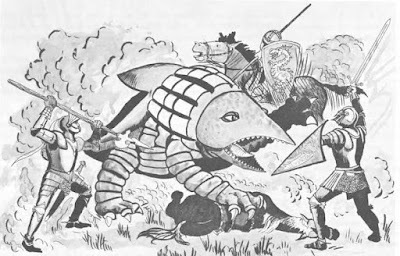

One aspect of the Monster Manual's artwork that grabbed my youthful attention was how often it depicted fear and death. Consider, for example, the piece accompanying the book's title page:

Here, we get three knights in historical armor facing off against a bulette. Beneath the landshark's front right claw, you can see the corpse of a horse (perhaps belonging to one of the two unmounted knights in the foreground). It's a small detail, seemingly unimportant, but it's the first example of a recurring motif in the Monster Manual's illustrations: facing off against monsters is perilous.

Here, we get three knights in historical armor facing off against a bulette. Beneath the landshark's front right claw, you can see the corpse of a horse (perhaps belonging to one of the two unmounted knights in the foreground). It's a small detail, seemingly unimportant, but it's the first example of a recurring motif in the Monster Manual's illustrations: facing off against monsters is perilous.

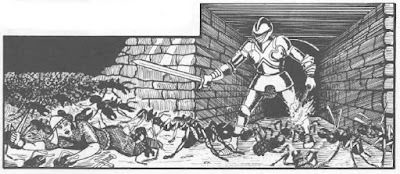

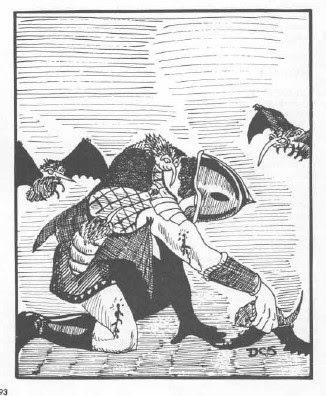

Again and again, you see this throughout the book: monsters frightening, harming, or killing those who dare to challenge them – often in unexpected places, like this one.

Those are giant ants and look how they use their large numbers to overwhelm their opponents, as do stirges in another memorable illustration.

Those are giant ants and look how they use their large numbers to overwhelm their opponents, as do stirges in another memorable illustration.

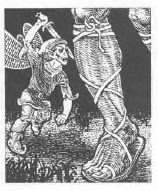

Of course, not all low-level monsters rely solely on numbers to get the better of their enemies. Take a look at this pixie.

Of course, not all low-level monsters rely solely on numbers to get the better of their enemies. Take a look at this pixie.

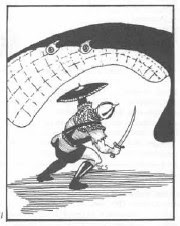

Being surprised by a lurking monster is another common element of Monster Manual illustrations, like the classic mimic preparing to punch the unfortunate thief attempting to open a "chest."

Being surprised by a lurking monster is another common element of Monster Manual illustrations, like the classic mimic preparing to punch the unfortunate thief attempting to open a "chest."

But there are many others in this style as well.

But there are many others in this style as well.

I could offer many more examples from the book and I'm sure readers will remember some of their own favorites. I adored these kinds of illustrations as a younger person, in large part because they emphasized the danger posed by monsters, even things as seemingly innocuous as giraffes.

Everything in the Monster Manual was a potential threat to life and limb and I can't tell how exciting that was to me as a budding Dungeon Master. While I was never a killer DM, I nevertheless did revel in seeing the looks of horror on players' faces as they realized what their characters were up against. Descending into a dungeon or wandering off into the wilderness is supposed to be frightening to some degree. A big part of the appeal of games like D&D, especially for young people, is being able to face those frights vicariously. That's part of why horror movies continue to be so popular, I imagine, particularly as the real world becomes ever safer and more sanitized. Something in our nature atavistically craves, maybe even needs fear and danger. Monsters in fantasy roleplaying games should give us a chance to experience both.

Everything in the Monster Manual was a potential threat to life and limb and I can't tell how exciting that was to me as a budding Dungeon Master. While I was never a killer DM, I nevertheless did revel in seeing the looks of horror on players' faces as they realized what their characters were up against. Descending into a dungeon or wandering off into the wilderness is supposed to be frightening to some degree. A big part of the appeal of games like D&D, especially for young people, is being able to face those frights vicariously. That's part of why horror movies continue to be so popular, I imagine, particularly as the real world becomes ever safer and more sanitized. Something in our nature atavistically craves, maybe even needs fear and danger. Monsters in fantasy roleplaying games should give us a chance to experience both.

June 7, 2023

Retrospective: Cyborg Commando

Catching lightning in a bottle is a wildly improbable thing to do once, so I don't think reflects poorly on a creator not to be able to do it a second time. Consequently, I find it difficult to judge the post-TSR career of Gary Gygax as harshly as some, even though his achievements after his October 1985 departure from the company he founded more than a decade prior could, at best, be described as uneven. Still, there's something genuinely admirable about the naive optimism Gygax must have possessed in thinking that his new business venture, New Infinities Productions, had a snowball's chance of lasting longer than the barely three years it actually did.

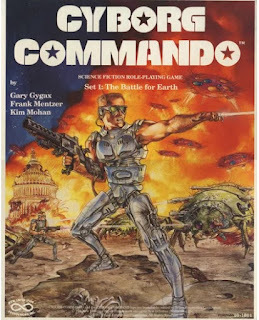

Catching lightning in a bottle is a wildly improbable thing to do once, so I don't think reflects poorly on a creator not to be able to do it a second time. Consequently, I find it difficult to judge the post-TSR career of Gary Gygax as harshly as some, even though his achievements after his October 1985 departure from the company he founded more than a decade prior could, at best, be described as uneven. Still, there's something genuinely admirable about the naive optimism Gygax must have possessed in thinking that his new business venture, New Infinities Productions, had a snowball's chance of lasting longer than the barely three years it actually did. Of course, the company's likelihood of success might have been greater had its inaugural first (and only) original roleplaying game hadn't been Cyborg Commando. Published in 1987, Cyborg Commando is a near-future science fiction RPG written by Gygax, Frank Mentzer, and Kim Mohan. Its premise is that, in the year 2035, Earth is invaded by extraterrestrial beings called Xenoborgs. In order to combat them, mankind turns to the nascent technology of cybernetics to create the titular cyborg commandos – human brains placed inside advanced robotic bodies arrayed with the most advanced weaponry available. Players assume the roles of these commandos as they attempt to rid Earth of the Xenoborgs and drive them back into space. (Since the initial boxed set is subtitled "Set 1: The Battle for Earth," I can only assume there were plans to expand the game's scope beyond this planet.)

Cyborg Commando consisted of a 48-page player's book (CCF Manual), a 64-page referee's book (Campaign Book), a 16-page booklet of introductory scenarios, and ten-sided dice in a box. This arrangement closely mimics TSR's own products at the time, but that should come as no surprise since New Infinities seems to have been staffed almost entirely by ex-TSR employees. That said, the game materials are noticeably less attractive and professionally done than those of TSR of the same era, particularly when it comes to the artwork. I wouldn't describe anything as awful, only a bit less "slick," no doubt due to the smaller production budget of the company.

The CCF Manual provides a brief overview of the game's setting and history, as well as the purpose of the Cyborg Commando Force to which all the player characters belong. The bulk of the book is devoted to the game's rules, which are a bit of a mess. The game uses ten-sided dice in a variety of ways: simple (1d10), added (1d10 + 1d10), and multiplied (1d10 × 1d10). The last use is particularly interesting to me, because I would have expected the game to use a straight percentile roll, but, perhaps in an attempt to "innovate," the designers opted to go another route. Helpfully(?), the CCF Manual includes several probability graphs to show the likelihood of results of each type of die roll. Though I am sure some players would find information of this sort useful, the inclusion of these tables is sadly representative of the game as a whole: too much detail about some things and not enough about others.

Character generation and combat both come in "basic" and "advanced" versions, with the latter building on the former. In principle, Cyborg Commando is completely playable using either version of the rules. However, much of the game's text and presentation seems to favor the advanced version, if only because of the additional detail it offers. A good example of this can be seen in the skill lists, where the advanced rules included many, many more skills than the basic version. Of course, the advanced version includes such skills as "general creativity," "domestic arts I," "domestic arts II," "obstetrics & gynecology," and "error avoidance," so I'm not entirely sure much of value would be lost by sticking to the basic versions. I mention all of this not mock Cyborg Commando. Rather, I hope it gives you some sense of the game system's strange obsession with minutiae that I can hardly imagine would ever come up in play at the table.

Of course, this obsession is not limited merely to the rules. The Campaign Book abounds in this level of useless detail as well. For example, nearly half of that volume consists of information on the populations of the countries of the world, along with their latitude and longitude coordinates, major cities, and CCF bases. Yet, for all that, this information consists of little more than tables and maps. It's a lot of heat but not much light for the referee hoping to get a sense of what the Earth of 2035 is actually like for the purposes of running adventures and campaigns in Cyborg Commando.

The other half of the Campaign Book is more genuinely useful. It details the Xenoborgs, including their biology, society, and culture. In addition, this section delves more deeply into the aliens' polymorphism, revealing that their leaders, the so-called Masters, are a type of Xenoborg not yet seen on Earth. The Masters are directing the invasion of the planet for its resources, hoping to make use of them to further the expansion of its star-spanning empire, which consists of hundreds of worlds across the galaxy. There are also sections about the FTL Q-drive the Xenoborgs use, which, as I noted earlier, seems to suggest that New Infinities hoped that Cyborg Commando would eventually expand beyond Earth.

That was not to be and it's not hard to see why. Cyborg Commando contains a handful of genuinely interesting ideas but the vast majority of it is muddled, half-baked, or silly. Judged even by the standards of 1987, it's not a good game and I suspect that even the folks at New Infinities knew this. The game received a small amount of support in the form of three adventure modules and some novels, but, by 1988, the company seems to have pinned its hopes on doing knock-off D&D support material – the Fantasy Master line – that might garner attention due to the names attached to them (Gygax, Mentzer, etc.). When that didn't happen, the company, along with Cyborg Commando, was largely forgotten. I wish I could say that was a shame.

June 6, 2023

White Dwarf: Issue #77

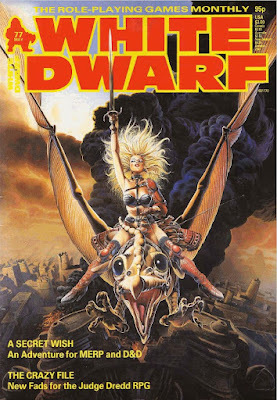

Issue #77 of White Dwarf (May 1986) features an immediately recognizable cover illustration by Chris Achilleos. The image is probably best-known for its appearance on the September 1981 issue of Heavy Metal, though it has appeared in many other places over the years. I've noted before that, compared to Dragon, WD more regularly used re-purposed artwork for its cover illustrations, though I've never come to a satisfactory conclusion as to why this was the case. My best guess is that it was a matter of simple economics, reprinted art being perhaps cheaper than commissioning original art, but I honestly don' know if that's the case. In any event, this particular cover induces a bit of cognitive dissonance in me, since I so strongly associate it with Heavy Metal, not White Dwarf.

Issue #77 of White Dwarf (May 1986) features an immediately recognizable cover illustration by Chris Achilleos. The image is probably best-known for its appearance on the September 1981 issue of Heavy Metal, though it has appeared in many other places over the years. I've noted before that, compared to Dragon, WD more regularly used re-purposed artwork for its cover illustrations, though I've never come to a satisfactory conclusion as to why this was the case. My best guess is that it was a matter of simple economics, reprinted art being perhaps cheaper than commissioning original art, but I honestly don' know if that's the case. In any event, this particular cover induces a bit of cognitive dissonance in me, since I so strongly associate it with Heavy Metal, not White Dwarf.

Issue #77 is also the last issue under the editorship of Ian Marsh. Marsh only took over in issue #74, so his departure so soon after his installation comes as a bit of a shock. In his final editorial, Marsh states that "the other staff of the magazine" would also be leaving, though he doesn't specify which ones. He seems to obfuscate on the reasons for all these departures, simultaneously reminding readers that Games Workshop was moving to Nottingham and that he and the others "have decided not to accompany it on this move," while also couching their decision as being for nebulous "reasons of our own." The next issue will have a "fresh team" headed up by Paul Cockburn.

The issue proper begins with the reviews of "Open Box." The first of these is Mayfair's DC Heroes, which receives a quite favorable (8 out of 10) review by Marcus L. Rowland, who continues to be the workhorse of the magazine. The Stormbringer adventure Stealer of Souls likewise scores 8 out of 10, while The Sea Elves, a supplement for the Elfquest RPG gets 7 on the same scale. Another Chaosium product, Alone Against the Dark for Call of Cthulhu earns 9 out of 10, but Yellow Clearance Black Box Blues for Paranoia receives only 7 – another example, I think, of where the numerical scores don't quite align with the text of the review itself. Finally, there are reviews of two supplements for FASA's Doctor Who RPG: The Daleks (7 out of 10) and The Master (6 out of 10).

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is mostly forgettable to me, as usual, but he does take note of the death of Frank Herbert, opining that Chapter House: Dune, to which he gave a "mildly favorable" review back in issue #65 might be the end of "galactic power-politicking" in the Dune universe. How I wish that had been true! Colin Greenwell's "2020 Vision" reviews a few movies, most notably Young Sherlock Holmes, a forgettable, even laughable, Steven Spielberg movie that nonetheless does feature one of the earliest examples of a computer-generated character in the history of cinema – a dire portent of things to come.

"The Crazy File" by Peter Tamlyn provides a handful of new "crazies" – zealous devotees of social fads – for use with the Judge Dredd – The Role-Playing Game. The article contains no game statistics; it's pure background information intended to give the referee something inspirational for use in his own adventures and campaigns. "Spellbound" by Phil Masters looks at "magic in superhero games." Again, there's nothing mechanical here. Instead, it's an overview of how magic has been used in comics over the years and then offers advice and examples of how to make use of it in one's own original superhero RPG adventures and campaigns. It's well done in my opinion and helped by the fact that it's not geared toward any particular superhero RPG.

"The Final Frontier" by Alex Stewart does something similar for Star Trek gaming: it's an overview of the unique characteristics of Gene Roddenberry's science fiction setting and how they can best be used to create enjoyable adventures and campaigns. As a fan of Star Trek – or at least I once was – I think the article is pretty well done for what it is, though I do find myself wondering about its intended audience. White Dwarf used to have lots of these introductory articles in its early days. To see them return so late in its run strikes me as odd, though I'm sure there's a logic to it that eludes me. Graham Staplehurst's "A Secret Wish" is an adventure that's written for both D&D and Middle-earth Role Playing. The scenario itself assumes the players take on the role of hobbits and deals with the disappearance and return of Glorfindel. How well it jibes with the actual history of Middle-earth as laid out by Tolkien, I can't rightly say, though, to me, it reads a bit like a work of fan fiction rather than something that could have come from the mind of the Professor himself. "A Cast of Thousands" by Graeme Davis is yet another look at NPCs and how to give them "personality." It's fine, though, as is so often the case with articles like this, I find it difficult to sift through the conventional wisdom repeated for the hundredth time from the genuine insights.

"The Cars That Ate Sanity" by Marcus L. Rowland is a set of car chase rules for use with Call of Cthulhu. Is this something anyone needed? I don't mean to be flippant, but I cannot recall any car chases in Lovecraft's fiction. Maybe my memory is failing me again. Chris Felton's "Gaming for Heroine Addicts" – a clever title – is about how avoid "sexism" in one's games and make them more enjoyable to women. As you might expect, the article is a very mixed bag of topics, not to mention perspectives. I'm not sure the article offers a coherent viewpoint on any of its topics, which range widely and make many assumptions about RPGs, men, women, and everything in between. I've already spent more time thinking about it than it probably deserves.

Joe Dever's "Tabletop Heroes" looks at the best techniques for photographing one's painted miniatures. I found it fascinating and very much appreciated the little diagrams that accompanied the article. They showed the placement of lighting, camera, and background and did a great job of illustrating the principles Dever discusses. "The Travellers," "Gobbledigook," and "Thrud the Barbarian" are all here as usual. "Thrud" pokes fun at superheroes by having the tiny-headed barbarian face off against the All-American Legion of Incredibly Stupid Heroes, such as

After reading Ian Marsh's farewell editorial, I now feel an obligation to read at least a few more issues. I'm genuinely curious now to see how much will change under a "fresh new team" at the helm of White Dwarf. If nothing else, it'll be fascinating purely from a historical perspective. Till then!

After reading Ian Marsh's farewell editorial, I now feel an obligation to read at least a few more issues. I'm genuinely curious now to see how much will change under a "fresh new team" at the helm of White Dwarf. If nothing else, it'll be fascinating purely from a historical perspective. Till then!

June 5, 2023

Haunting Horrors of the Past Rise Again!

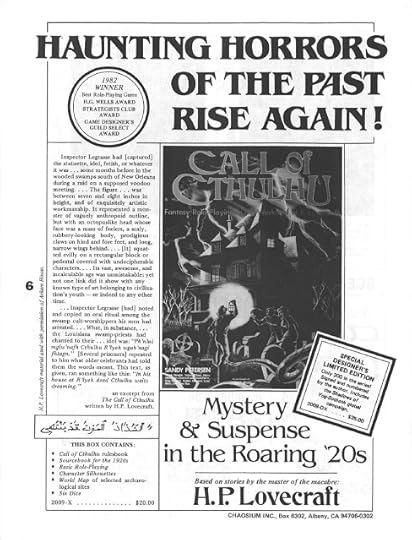

I always enjoy looking at old consumer product catalogs, especially those associated with RPG companies. Here's a good example from Chaosium's Winter 1982 catalog, advertising the original Call of Cthulhu boxed set, along with a "special designer's limited edition" set of 200 copies that, for $5 more than the standard one, is signed by the author and includes Shadows of Yog-Sothoth to boot – not a bad deal! [My aged eyes are mistaken; the price is $35 for the limited edition, which isn't quite as good a deal as I thought – JM]

June 4, 2023

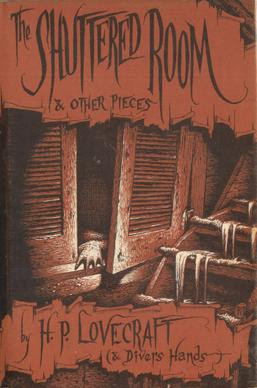

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Shuttered Room

After last week's review of

The Fungi from Yuggoth

, I found myself thinking about poor old August Derleth and the vitriol he's received over the years from admirers of H.P. Lovecraft. On many levels, I completely understand the venom directed at him. His vision of what he termed "the Cthulhu Mythos" stands in stark contrast to HPL's understanding of his own work. While Lovecraft espoused a cosmicism verging on the nihilistic, Derleth offered instead a more conventional (and pulp fiction-inspired) good versus evil philosophy, one in which brave men of erudition, armed with all manner of occult armament, go toe to toe with the alien forces of the Mythos and win. To purists, this is an unforgivable sin.

After last week's review of

The Fungi from Yuggoth

, I found myself thinking about poor old August Derleth and the vitriol he's received over the years from admirers of H.P. Lovecraft. On many levels, I completely understand the venom directed at him. His vision of what he termed "the Cthulhu Mythos" stands in stark contrast to HPL's understanding of his own work. While Lovecraft espoused a cosmicism verging on the nihilistic, Derleth offered instead a more conventional (and pulp fiction-inspired) good versus evil philosophy, one in which brave men of erudition, armed with all manner of occult armament, go toe to toe with the alien forces of the Mythos and win. To purists, this is an unforgivable sin.I find it difficult to disagree with the purists, simply on the level of basic reading comprehension. Derleth does not seem to have understood Lovecraft or his worldview – or, if he did, he chose to set aside that understanding, substituting in its place something he felt more suited to turning the Mythos into a money-making operation. That Derleth spent decades asserting the sole right of his publishing venture, Arkham House, to control of Lovecraft's copyrights and legacy only adds more fuel to the anti-Derlethian fire that continues to rage to this day.

Yet, for all that, I find it difficult to condemn him for the role he played in warping the popular understanding of H.P. Lovecraft and his works. As I have argued elsewhere, his pulp-inflected version of the Cthulhu Mythos deviates wildly from Lovecraft's original, almost to the point of becoming a parody of it, but, without it, I don't think, for example Call of Cthulhu would have been possible, let alone most other pop culture examples of so-called "cosmic horror." I don't think this can be reasonably disputed, though I am sure there are purists who would be willing to give up Call of Cthulhu or Hellboy or Quake in exchange for a world free from Derleth's abhorrent misinterpretations of Grandpa Theobald's unwavering cosmicism.

I am not one of them, which is why I still retain some fondness for some of Derleth's Mythos fiction, including his many "posthumous collaborations," like "The Shuttered Room," which first appeared in a 1959 anthology of the same name. The story concerns the return of Abner Whateley to his hometown of Dunwich after years away "at the Sorbonne, in Cairo, in London." Abner, we learn, was different from the other Whateleys in that, from early childhood, he wanted to get as far away from the lands of his ancestors as possible. He feared "the wild, lonely country" of his birth and his "grim old Grandfather Whateley in his ancient house attached to the mill along the Miskatonic." Only family business could bring him back.

And nothing was stranger than that Abner Whateley should come back from his cosmopolitan way of life to heed his grandfather's adjurations for property which was scarcely worth the time and trouble it would take to dispose of it. He reflected ruefully that such relatives as still lived in or near Dunwich might well resent his return in their curious inward growing and isolated rustication which had kept of the Whateleys in this immediate region, particularly since the shocking events which had overtaken the country branch of the family on Sentinel Hill.

If this set-up seems all too familiar, it's because it is. Leaving aside Derleth's lifelong obsession with "The Dunwich Horror," the HPL story that provided him with the foundation stones for his interpretation of the Mythos, the set-up of "The Shuttered Room" is one we've some many times before in Lovecraft's stories – and Derleth's imitations of them. From "The Festival" and "The Call of Cthulhu" to "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" and many others, a recurring plot element of Lovecraft's work is the return of a protagonist to the home of his ancestors or relations that leads to unexpected (and frequently unwelcome) revelations about the world and himself. I can't really fault Derleth for making use of it here, since he was only following in the footsteps of his friend and mentor. Nevertheless, its use does make it clear that "The Shuttered Room" is yet another pastiche rather than something more original.

Abner his inherited his grandfather's old home upon his death. Once he arrives there, he finds an envelope, inside of which is a letter written in "spidery script" that explains why his grandfather, Luther, had insisted he come back to Dunwich after so many years away.

Grandson:

When you read this, I will be some months dead. Perhaps more, unless they find you sooner than I believe they will. I have left you a sum of money – all I have and die possessed of – which is in the bank at Arkham under your name now. I do this not alone because you are my one and only grandson but because among all the Whateleys – we are an accursed clan, my boy – you have gone forth into the world and gathered to yourself learning sufficient to permit you to look upon all things with an inquiring mind ridden neither by the superstition of ignorance nor the superstition of science. You will undersrand my meaning.

It is my wish that at least the mill section of this house be destroyed. Let it be taken apart, board by board. If anything in it lives, I adjure you, solemnly to kill it. No matter how small it may be. No matter what form it may have, for it seem to you human it will beguile you and endanger your life and God knows how many others.

Heed me in this.

The letter reminds Abner of how, when he was a boy, his "enigmatic, self-righteous" grandfather had reacted strongly at the mention of his mother's sister.

The old man had looked at him out of eyes that were basilisk and answered, "Boy, we do not speak of Sarah here."

Aunt Sarey had offended the old man in some dreadful way – dreadful, at least, to that firm disciplinarian – for from that time beyond even Abner Whateley's memory, his aunt had only been the name of a woman, who was his mother's older sister, and who was locked in the big room over the mill and kept forever invisible within those walls, behind the shutters nailed to her windows. It had been forbidden both Abner and his mother even to linger before the door of that shuttered room, though on one occasion Abner had crept up to the door and put his ear against it to listen to the snuffling and whimpering sounds that went on inside, as from some large person, and Aunt Sarey, he had decided must be as large as a circus fat lady, for she devoured so much, judging by the great platters of food – chiefly meat, which she must have prepared herself, since so much of it was raw – carried to the room twice daily by old Luther Whateley himself, for there were no servants in that house, and had not been since the time Abner's mother had married, after Aunt Sarey had come back, strange and mazed, from a visit to distant kin in Innsmouth.

And there it is! One of the reasons I chose to write about "The Shuttered Room" is because it's a great example of one of Derleth's great flaws: his fanboyish desire to find a way to connect the disparate parts of Lovecraft's works into a unified whole. Hence, in this story, he finds a way to link "The Dunwich Horror" to "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" – in addition to extensive borrowings, references, and allusions to many, many HPL stories and ideas. "The Shuttered Room" is thus a showcase of Derleth's almost adolescent adoration of Lovecraft.

And yet, for all of that, it's not a terrible story. Indeed, it's cleverer than one might imagine, since the story's revelations about Abner's grandfather, Aunt Sarey, and why the mill section of the house must be destroyed are not quite what you might expect. Indeed, Derleth almost comes close to offering an inversion of and commentary upon "The Dunwich Horror." At the very least, this isn't a simple retelling of his favorite Lovecraft tale, which sets its apart from much of his other contributions to the Mythos.

This isn't to say that "The Shuttered Room" is a great work, but it's nevertheless engaging in a predictable sort of way – the literary equivalent of "comfort food." It's also the kind of story that hits home, I think, just how much Call of Cthulhu and contemporary "Lovecraftian" media owes to Derleth. "The Shuttered Room" is not a story HPL himself could have written, but it could easily be the basis for a CoC scenario, an episode of The X-Files, or a Stuart Gordon movie. Sometimes, that's enough.

June 1, 2023

Erol Otus Webstore

Several of you have sent me a link to the official Erol Otus webstore, where the celebrated old school RPG illustrator is now selling a small selection of products featuring his artwork, including the T-shirt above. With luck, more products will become available in the future, though a lot depends, I suppose, on what rights Otus might have retained of his TSR era pieces.

Several of you have sent me a link to the official Erol Otus webstore, where the celebrated old school RPG illustrator is now selling a small selection of products featuring his artwork, including the T-shirt above. With luck, more products will become available in the future, though a lot depends, I suppose, on what rights Otus might have retained of his TSR era pieces.

May 31, 2023

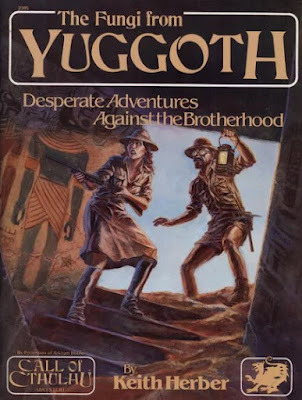

Retrospective: The Fungi from Yuggoth

I find it a great irony that, while Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu has undoubtedly played an outsized role in the increased visibility and recognition of the works of H.P. Lovecraft in popular culture, the game itself owes more to August Derleth's idiosyncratic interpretation of HPL's Mythos than it does to the views of the Old Gent himself. This is no criticism, just a statement of facts as I look back on more than four decades' worth of Call of Cthulhu adventures and campaigns, starting with Shadows of Yog-Sothoth in 1982. Except for a handful of exceptions, Chaosium's vision differs only in details from that of Derleth's lurid, melodramatic The Trail of Cthulhuhe Trail of Cthulhu, in which scholar-adventurer Laban Shrewsbury battles the forces of the Mythos (and its human toadies) across time and space.

I find it a great irony that, while Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu has undoubtedly played an outsized role in the increased visibility and recognition of the works of H.P. Lovecraft in popular culture, the game itself owes more to August Derleth's idiosyncratic interpretation of HPL's Mythos than it does to the views of the Old Gent himself. This is no criticism, just a statement of facts as I look back on more than four decades' worth of Call of Cthulhu adventures and campaigns, starting with Shadows of Yog-Sothoth in 1982. Except for a handful of exceptions, Chaosium's vision differs only in details from that of Derleth's lurid, melodramatic The Trail of Cthulhuhe Trail of Cthulhu, in which scholar-adventurer Laban Shrewsbury battles the forces of the Mythos (and its human toadies) across time and space.

I was reminded of this recently when I re-read Keith Herber's eight-chapter campaign, The Fungi from Yuggoth. First published in 1984, the book carries the subtitle "Desperate Adventures Against the Brotherhood." This is both a reference to its primary antagonists, the Brotherhood of the Beast, and a signal that, like Shadows of Yog-Sothoth before it, The Fungi from Yuggoth is more of a Mythos-tinged Republic serial than a subtle evocation of Lovecraft's cosmicism. I reiterate: this is no criticism. However, I feel it's important to deflate the all-too-common pretension that Call of Cthulhu has ever been a particularly faithful adaptation of the worldview of Lovecraft's tales to the roleplaying medium, as products like this one make clear.

The premise of the campaign is that, in the 18th century B.C., an Egyptian priest called Nophru-Ka – not to be confused with the dark pharaoh Nephren-Ka, who is apparently a different person altogether – uttered a cryptic prophecy that was eventually preserved in the Necronomicon. As interpreted by the madmen who founded the secret society known as the Brotherhood of the Beast, the prophecy spoke of a time when a descendant of Nophru-Ka, who would usher in a new world ruled by the beings of the Mythos. At the start of the campaign (mid-1928), the Brotherhood long ago found Nophru-Ka's descendant, Edward Chandler, whom they have been grooming for his prophesied role since he was a child. Naturally, it's up to the Investigators to prevent this.

In typical Call of Cthulhu – and cliffhanger serial – fashion, preventing the ascendancy of Edward Chandler requires the Investigators to travel across the globe, searching for clues, artifacts, and allies to aid them in their efforts. Over the course of the campaign's eight chapters, the Investigators travel from New York to places as different as Boston, Transylvania(!), Egypt, Peru, and San Francisco, with an optional stopover at the Great Library of Celaeno in the Hyades Cluster, some 150 light years away from Earth (a site invented by August Derleth in the aforementioned The Trail of Cthulhu). Along the way, they tangle with an equally diverse group of foes: gangsters, cultists, mummies, Deep One hybrids, the titular Fungi, and more. There's plenty going on in this campaign and I have no doubt whatsoever that it would be a lot of fun to play.

At the same time, The Fungi from Yuggoth, with its global conspiracy to shepherd the rise of a Mythos Antichrist, doesn't feel much like Lovecraft. There are plenty of plot elements derived from Lovecraft in its eight chapters, but they're strung together in a way that feels like more an Indiana Jones movie than something coming from the pen of HPL. As I re-read the book, I could practically hear the John Williams soundtrack and see an animated red line traveling across a globe, marking each city or location the Investigators visited in their "desperate adventures against the Brotherhood." All that's missing are the Nazis, though, since the campaign takes place in the late 1920s, that's understandable (though one of the main cultists is German).

The Fungi from Yuggoth is weapons grade Derlethium – and that's fine. As I stated at the beginning of this post, nearly every Call of Cthulhu adventure ever published, including the deservedly praised Masks of Nyarlathotep, is, at base, a pastiche of Derleth's pastiches of Lovecraft. Many of these products, including The Fungi from Yuggoth, are very well done. As roleplaying game scenarios, they're some of the best things the hobby has ever produced and I do not hesitate to recommend them. I have enjoyed Call of Cthulhu since its original release in 1981 and hope to one day get the chance to enjoy it again.

In all those years, however, I don't believe I've ever played an adventure or a campaign that offered more than the occasional genuinely Lovecraftian moment. The rest of my experiences were of pulp adventure with a Mythos twist. That's probably for the best. I'm not sure that an "authentic" experience of Lovecraft's nihilistic cosmicism would be a lot of fun to play out at the table. Ultimately, that's probably why nearly everything Chaosium has ever published for Call of Cthulhu unintentionally looks to Derleth for its inspiration: it's just more fun.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers