James Maliszewski's Blog, page 71

July 17, 2023

REVIEW: The Staffortonshire Trading Company Works of John Williams

Roleplaying games set in the past of the real world, whether played straight or including an element of the fantastical, have always been hard sells. A big reason for this, I think, is that gamers, even well-read ones with access to the vast store of information that is the Internet, often lack for practical resources to support play in past ages. By "practical resources," I mean the kinds of things that RPGs with wholly imaginary settings include without a second thought, like appropriate equipment lists, details about law and order, information about society and culture – or maps.

Roleplaying games set in the past of the real world, whether played straight or including an element of the fantastical, have always been hard sells. A big reason for this, I think, is that gamers, even well-read ones with access to the vast store of information that is the Internet, often lack for practical resources to support play in past ages. By "practical resources," I mean the kinds of things that RPGs with wholly imaginary settings include without a second thought, like appropriate equipment lists, details about law and order, information about society and culture – or maps.Now, maps might seem like a small thing, perhaps even a relatively unimportant one. After all, we all know what a castle or a mansion or a church looks like, right? Even assuming that's true – which experience has taught me it is not – the matter isn't as simple as it might appear, especially when you're dealing with locales within a specific time and place. One might know what a mansion house looks like in, say, England during the 1920s, but what about the 1820s? What about a mansion house in France or Germany or the United States? With enough qualifiers and specificity, the questions become a lot more vexed and the work of the referee much more onerous.

Enter The Staffortonshire Trading Company Works of John Williams (hereafter simply Works) by Glynn Seal. Written for and published by Lamentations of the Flame Princess, it's a beautifully made – and supremely useful – 126-page hardcover volume consisting of nearly 100 maps of 17th-century buildings and sailing vessels from Europe, North Africa, Asia, and the New World. The book's framing device, as presented in its introduction, is that the maps were all made by the Englishman John Benjamin Williams in 1674. Williams was employed as a cartographer and architect by the Staffortonshire Trading Company, a vocation that took all across the globe, from England to North America to Europe and into the Ottoman Empire and beyond. During his time with the trading company, Williams also acted as a spy for English crown, thereby providing an explanation for some of the more unusual places he visited – and created maps for – during his travels.

The included maps are quite varied, covering fairly mundane locations (shops, houses, churches), more socially sophisticated ones (mansions, colleges, palaces), highly specialized ones (ships, water mill, lighthouse), and the truly unusual (cockfighting theater, mineshaft, whaling station). Furthermore, a number of singular locations also receive attention, such as Dudley Castle, the Kremlin, the Palais de Tuileries, and the Jamestown settlement of colonial Virginia. As you can see, the locales are remarkably diverse, both in terms of purpose and geography. There's naturally a heavy focus on western Europe, with England and France predominating, but that doesn't in any way detract from the utility of this book to anyone playing or refereeing a game set in the 17th century.

All of the maps include a key and a scale and many of them also include an illustration depicting the building or vessel. These illustrations are as useful as the maps themselves, since they serve as visualization aids – something that's very important in historical RPGs in my experience. After all, it's one thing to know what a generic mansion or church looks like, but what did such things look like in the 1600s? Beyond that, these illustrations include significant additional details, like the materials used in their construction, which adds to the sense of time and place that are vital to the success of historical roleplaying game adventures.

Of course, this attention to detail should come as no surprise. Glynn Seal, the author and cartographer of Works, has previously produced numerous fantasy RPG products whose maps are similarly detailed and useful. Likewise, Lamentations of the Flame Princess products are always exceptionally well made, with superb paper quality and binding. This one is no exception, featuring as it does thick, parchment like paper that adds to the illusion that this is a book from the 17th century. Merely as an artifact, Works is a joy to hold and peruse. That it's also so useful to players and referees of any RPG set in the 17th century, only increases its value.

The Staffortonshire Trading Company Works of John Williams is available in both print and PDF formats. If you're interested in seeing what the interior of the book looks like, Glynn Seal has provided lots of photographs and a helpful video here.

Rhubarb

Though my series of White Dwarf retrospectives is complete, I continue to examine the advertisements that appeared in the magazines. I do this partly out of pure nostalgia – I enjoy being reminded of important RPG releases from my youth – but I also do it because, as a UK periodical, WD regularly had advertisements I never saw elsewhere.

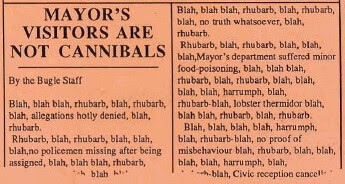

A good case in point is one for TSR's Marvel Super Heroes game. The ad consisted of the front page of The Daily Bugle, featuring several headlines and news articles. One of them is entitled "Mayor's Visitors Are Not Cannibals," which I've reproduced below.

What's fascinating about the "story" above is that it contains only a handful of intelligible words, with the rest of its text consisting of "blah," "harrumph," and "rhubarb" written over and over. "Rhubarb," for those who don't know, is the UK equivalent to the American "walla," a word repeated over and over again by extras in order to mimic the murmur of conversation by a crowd. Its appearance here is quite funny to me, since it's being used in written form to fill out the text of an imaginary article in an advertisement rather than as audio filler.

What's fascinating about the "story" above is that it contains only a handful of intelligible words, with the rest of its text consisting of "blah," "harrumph," and "rhubarb" written over and over. "Rhubarb," for those who don't know, is the UK equivalent to the American "walla," a word repeated over and over again by extras in order to mimic the murmur of conversation by a crowd. Its appearance here is quite funny to me, since it's being used in written form to fill out the text of an imaginary article in an advertisement rather than as audio filler.

July 16, 2023

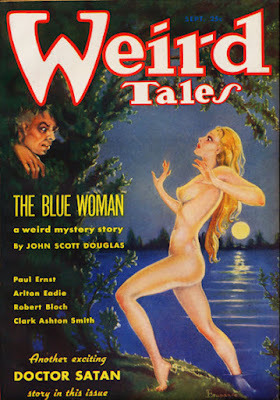

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Shambler from the Stars

Robert Bloch's youthful friendship with H.P. Lovecraft is an important and well-known part of his biography. It was Lovecraft, after all, who not only encouraged him in his early efforts at writing fiction but who also introduced him to his circle of friends and colleagues, like August Derleth, Clask Ashton Smith, and Donald Wandrei, many of whom would, in turn, play significant roles in his subsequent growth as a writer. Despite this, it was HPL whom Bloch most admired and whom he considered his true mentor, so much so that news of Lovecraft's death in 1937 came as "a shattering blow" that caused him much distress.

Robert Bloch's youthful friendship with H.P. Lovecraft is an important and well-known part of his biography. It was Lovecraft, after all, who not only encouraged him in his early efforts at writing fiction but who also introduced him to his circle of friends and colleagues, like August Derleth, Clask Ashton Smith, and Donald Wandrei, many of whom would, in turn, play significant roles in his subsequent growth as a writer. Despite this, it was HPL whom Bloch most admired and whom he considered his true mentor, so much so that news of Lovecraft's death in 1937 came as "a shattering blow" that caused him much distress. Ironically, less than two years earlier, in the September 1935 issue of Weird Tales, Bloch jokingly killed Lovecraft – or rather his fictional avatar – in a short story entitled "The Shambler from the Stars." The story is told from the perspective of an unnamed narrator living in Milwaukee who is attempting to make a living as "a writer of weird fiction." However, we soon learn that the narrator is not a very good writer.

My first attempts soon convinced me how utterly I had failed. Sadly, miserably, I fell short of my aspired goal. My vivid dreams became on paper merely meaningless jumbles of ponderous adjectives, and I found no ordinary words to express the wondrous terror of the unknown. My first manuscripts were miserable and futile documents; the few magazines using such material being unanimous in their rejections.

Bloch is poking fun at himself and his own early efforts to become a writer after the fashion of his idol, H.P. Lovecraft. Indeed, what makes this story so charming are its passion and its sincerity. It seems quite clear to me that Bloch is using "The Shambler from the Stars" to tell, in fictional and darkly humorous form, the story of his struggles to become a journeyman writer of the weird.

I wanted to write a real story; not the stereotyped, ephemeral sort of tale I turned out for the magazines, but a real work of art. The creation of such a masterpiece became my ideal. I was not a good writer, but that was not entirely due to my errors in mechanical style. It was, I felt, the fault of my subject matter. Vampires, werewolves, ghouls, logical monsters—these things constituted material of little merit. Commonplace imagery, ordinary adjectival treatment, and a prosaically anthropocentric point of view were the chief detriments to the production of a really good weird tale.

I must have new subject matter, truly unusual plot material. If only I could conceive of something utterly ultra-mundane, something truly macrocosmic, something that was teratologically incredible!

I longed to learn the songs the demons sing as they swoop between the stars, or hear the voices of the olden gods as they whisper their secrets to the echoing void. I yearned to know the terrors of the grave; the kiss of maggots on my tongue, the cold caress of a rotting shroud upon my body. I thirsted for the knowledge that lies in the pits of mummied eyes, and burned for wisdom known only to the worm. Then I could really write, and my hopes be truly realized.

I can't speak for anyone else, but I find the above paragraphs quite moving – and beautiful. They speak eloquently of the insatiable, almost destructive, drive felt by anyone who's ever desired to create something of last value. In the case of the story's narrator, the drive soon proves to be destructive indeed. He seeks out "correspondence with isolated thinkers and dreamers all over the country to aid him in his quest for "something utterly ultra-mundane" to serve as the basis for the "real story" he longed to write.

There was a hermit in the western hills, a savant in the northern wilds, a mystic dreamer in New England. It was from the latter that I learned of the ancient books that hold strange lore. He quoted guardedly from the legendary Necronomicon, and spoke timidly of a certain Book of Eibon that was reputed to surpass it in the utter wildness of its blasphemy. He himself had been a student of these volumes of primal dread, but he did not want me to search too far. He had heard many strange things as a boy in witch-haunted Arkham, where the old shadows still leer and creep, and since then he had wisely shunned the blacker knowledge of the forbidden.

Again, Bloch draws on his own life, fictionalizing his correspondence with Lovecraft and the role the Old Gent played, metaphorically, in opening his eyes to the "strange lore" and "primal dread" of the universe. The New England dreamer provides the unnamed narrator with "the names of certain persons" he thought helpful to his quest. Unfortunately, none of these contacts, whether "universities, private libraries, reputed seers, and the leaders of carefully hidden and obscurely designated cults" was willing to aid him. Their replies to his queries "definitely unfriendly, almost hostile" and he almost abandons all hope of ever learning anything "truly macrocosmic" on which to draw for his weird fiction.

The narrator does not give up, however. He travels to Chicago and finds "a little old shop on South Dearborn Street," which contains "a great black volume with iron facings." The book bears the title De Vermis Mysteriis – "Mysteries of the Worm" – and was written by a Belgian sorcerer named Ludvig Prinn. Though a truly "phenomenal find," as it is precisely the kind of blasphemous tome his New England correspondent recommended he seek out, the narrator cannot read it, because its contents are entirely in Latin, a language he could not understand. So close and yet so far!

For a moment I despaired, since I was unwilling to approach any local classical or Latin scholar in connection with so hideous and blasphemous a text. Then came an inspiration. Why not take it east and seek the aid of my friend? He was a student of the classics, and would be less likely to be shocked by the horrors of Prinn's baleful revelations. Accordingly I addressed a hasty letter to him, and shortly thereafter received my reply. He would be glad to assist me—I must by all means come at once.

It should come as no surprise to learn that his meeting with his correspondent at his home – in Providence, Rhode Island, no less! – does not go well, particularly for his correspondent, as I mentioned at the start of this post. Nevertheless, Bloch does a creditable job of holding the reader's attention as he describes the inevitable disaster that unfolds when the two men finally meet in person – a meeting that never occurred in the case of Bloch and Lovecraft, I should add, to the former's lifelong regret.

Much like Derleth's "The Lamp of Alhazred," "The Shambler from the Stars" serves as a tribute to Lovecraft and his role in fostering the career of a younger contemporary. As a result, the grisly demise of his literary stand-in was intended affectionately, which exactly how HPL did take it. In fact, Lovecraft was so taken with Bloch's yarn that he would pen a sequel, "The Haunter of the Dark," that would appear a little over a year later and be the very last original story he'd ever write.

July 14, 2023

I Hate Shopping

If there's one aspect of roleplaying games that I intensely dislike, it's buying equipment. In general, I find it a dreary waste of time and avoid it whenever possible, both as a player and as a referee. This is especially true in the case of science fiction RPGs, where the range of potential purchases is generally vastly greater than that available in a fantasy game (though there are, of course, exceptions) – as is the pain I suffer when having to endure it.

If there's one aspect of roleplaying games that I intensely dislike, it's buying equipment. In general, I find it a dreary waste of time and avoid it whenever possible, both as a player and as a referee. This is especially true in the case of science fiction RPGs, where the range of potential purchases is generally vastly greater than that available in a fantasy game (though there are, of course, exceptions) – as is the pain I suffer when having to endure it. I was reminded of my loathing for this aspect of gaming last weekend during the latest session of the otherwise thoroughly enjoyable Traveller campaign in which I am playing. Currently, there's a slight lull in the action, as the characters prepare to leave the planet on which they've been adventuring and head off to another one. Since the planet in question is both highly populated and technologically advanced, thoughts naturally turned toward the acquisition of additional gear. This led to the majority of the evening spent with players' noses in their copies of the Central Supply Catalogue, scouring it for every last bit of equipment that might give their characters an edge in future.

I, on the other hand, spent most of the evening reading a book at my desk, waiting for the pain to end. Occasionally, a fellow player would suggest to me a piece of equipment that he thought my character ought to buy and I'd briefly look up from my book to investigate the matter in my own copy of the CSC before deciding that I lacked sufficient interest in the fine gradations of high-tech weaponry to care. Further, there's the fact that the Mongoose Traveller rules, while more than adequate to the task, have added a little more complexity to equipment statistics than I like.

For example, a friend suggested that my character, a retired Army officer skilled in the use of heavy weapons, get a plasma gun, which first becomes available at the tech level of the planet on which we currently found ourselves. However, a plasma gun has the "very bulky" trait, which means my character must wear battle dress to use it effectively. Alas, my character lacks training in battle dress. "No problem," says, another friend, "You can add gyroscopic stabilization to the gun to reduce it to merely 'bulky,' which negates the need for battle dress in exchange for a penalty to the attack roll." I counter that penalty would negate my skill levels in heavy weapons." "True," is the reply, "but the increase in damage compared to your current weapon more than makes up for it." And so it goes throughout the night.

I don't wish to appear petulant, though I suppose that's as good a description as any of my emotional state that evening. The simple truth is that I'm rarely interested in the fine print of game statistics and games that include extensive lists of equipment necessarily add to rules complexity in order to differentiate all the new gear they introduce. That's fine for those who enjoy that sort of thing, but I've never really been one of them. It's rare, in my experience, that these subtle distinctions between types of, say, laser rifles or swords make enough difference in play to justify the extra time spent poring over books to find them.

Perhaps there's something wrong with me, since a large number of gamers, particularly those who play SFRPGs, love their equipment listings – and indeed entire books of new equipment. I wonder if my having been introduced to the hobby through Holmes Basic, where most weapons do 1d6 damage regardless of size or cost, has warped my mind so that I don't see much value in devoting lots of time to equipment acquisition. Am I alone in feeling this way?

July 13, 2023

Trivial Pursuits

The other day a friend of mine whom I have not seen in many years paid a visit and, along with two other friends, we had lunch together. One of those other friends brought with him a copy of the Dungeons & Dragons edition of the game Trivial Pursuit. I think I may have been dimly aware of its existence, but I'd certainly never played it before. I seem to recall that, a couple of years ago(?), Hasbro produced a whole slew of oddly D&D-branded editions of classic boardgames, like Clue and Monopoly, so I'm not at all surprised that there'd be a D&D Trivial Pursuit as well – and, unlike the others, it makes some degree of sense, since D&D certainly has a fair share of trivia associated with it.

The other day a friend of mine whom I have not seen in many years paid a visit and, along with two other friends, we had lunch together. One of those other friends brought with him a copy of the Dungeons & Dragons edition of the game Trivial Pursuit. I think I may have been dimly aware of its existence, but I'd certainly never played it before. I seem to recall that, a couple of years ago(?), Hasbro produced a whole slew of oddly D&D-branded editions of classic boardgames, like Clue and Monopoly, so I'm not at all surprised that there'd be a D&D Trivial Pursuit as well – and, unlike the others, it makes some degree of sense, since D&D certainly has a fair share of trivia associated with it.That said, I was initially reluctant to participate in the game. As long-time readers know, I have a strong aversion to the lifestyle brandification of everything these days, especially hallowed nerd pastimes. On the other hand, it was all in good fun. Curmudgeon I may be, but even I couldn't permit myself to sneer in the corner while everyone else was enjoying themselves. Furthermore, I was pretty sure I could win, since my brain is jampacked with useless information about Dungeons & Dragons. If I couldn't put that information to good use winning a friendly game in a bar on a Tuesday afternoon, what good was it anyway?

I hadn't played Trivial Pursuit in likely decades. I had forgotten just how tedious it is, with its requirement that a piece has to land on one of the special designated spaces before a player can acquire a "wedge" for the category associated with it. This results in nigh endless wandering around the board until you roll the right number. The D&D version mixes this up a little by introducing the use of more dice – d4, d6, d8, d10, and d12 – which allows the player to tailor the range of results and thus (theoretically) make it easier to reach one's desired space on the board. Nevertheless, my friends quickly ruled that a player could get a wedge from any space of the appropriate color. Otherwise, we'd probably have been playing for even longer.

The categories of the trivia were, I think, six in number: history, magic and miscellany, monsters, characters, dungeons and adventures, and cosmology. Like all editions of Trivial Pursuit, they ranged from the truly obscure ("What was the name of the needlepoint company TSR acquired in 1982?") to the blindingly obvious ("What spellcasting class can use create food and drink?"). I naturally did well in the history category, which included lots of questions about the early history of the hobby ("What was the name of Brian Blume's brother?" and "What was the name of the King of the Orcs in the Blackmoor campaign?"). The other categories proved hit or miss for me, since they included an inordinate amount of questions pertaining to 5th Edition – not a shock, I guess, but I know next to nothing about it.

In the end, I did in fact win the game, though it was actually close. I had much more fun than I expected I would and would definitely play it again. In the course of play, I discovered that I know a disturbingly large amount about both the Forgotten Realms and Dragonlance settings. Conversely, I don't know nearly as much about the specifics of magic items and magic spells. I also learned that I should have invested more time in my youth reading D&D novels, because many of the questions in the "characters" category seemed to involve characters who appeared in them.

As I get older and my memory becomes less acute, I am regularly amazed – disappointed? – by how much I can still remember about trivial things like D&D. For example, I am still capable of recognizing an episode of the original Star Trek series after seeing only its first minute or so, but I sometimes struggle to recall why I've entered a room. It's maddening the way memory works and I imagine it will only get more maddening as my senescence creeps ever closer. Fortunately for me, games like the D&D edition of Trivial Pursuit exist, so I can feel, if only for a little while, that I hadn't wasted my youth by learning all this stuff.

July 12, 2023

Retrospective: Monstrous Compendium

Though it's not an absolute rule, one of the guiding principles behind my selection of a gaming product for discussion in a Retrospective post is that it was originally published during the first decade of the hobby, which is to say, between 1974 and 1984. Obviously, if you scour the more than 300 entries in this series, you'll find plenty of examples of things published outside that time period, particularly when it comes to companies like TSR, GDW, and Chaosium, all of which published games I continue to hold dear. Nevertheless, I still try to stick to that ten-year period, if only to narrow my range of options.Every now and then, though, events suggest a subject for a post that is very much beyond the scope of this blog. That happened the other day, as I was re-arranging some shelves and set my eyes upon the oversized white binder of the Monstrous Compendium for AD&D Second Edition. Unlike my copies of the 2e Player's Handbook and Dungeon Master's Guide, which are within easy reach, the Monstrous Compendium binder is placed up high, buried under a number of other books and boxes. I put it up there a few months ago, after briefly looking at its entry on giant centipedes, which was probably the first time I'd done so in years.

Though it's not an absolute rule, one of the guiding principles behind my selection of a gaming product for discussion in a Retrospective post is that it was originally published during the first decade of the hobby, which is to say, between 1974 and 1984. Obviously, if you scour the more than 300 entries in this series, you'll find plenty of examples of things published outside that time period, particularly when it comes to companies like TSR, GDW, and Chaosium, all of which published games I continue to hold dear. Nevertheless, I still try to stick to that ten-year period, if only to narrow my range of options.Every now and then, though, events suggest a subject for a post that is very much beyond the scope of this blog. That happened the other day, as I was re-arranging some shelves and set my eyes upon the oversized white binder of the Monstrous Compendium for AD&D Second Edition. Unlike my copies of the 2e Player's Handbook and Dungeon Master's Guide, which are within easy reach, the Monstrous Compendium binder is placed up high, buried under a number of other books and boxes. I put it up there a few months ago, after briefly looking at its entry on giant centipedes, which was probably the first time I'd done so in years. As I pondered this fact, I started to think that I ought to write a post about the MC, even though it appeared in 1989 and was published for an edition of Dungeons & Dragons that I usually don't cover (usually). 2e occupies a strange place in the pantheon of D&D editions. A TSR edition bearing the unmistakable DNA of its more celebrated predecessors, it's rarely mentioned in most discussions of "old school D&D." The reasons for that are many and probably worthy of a separate post (or posts). Suffice it to say that I don't presently have any plans to expand Grognardia's ambit to include much 2e content. However, I do reserve the right to talk about it from time to time, as I have already done, when I think the edition touches on a topic worth discussing.

In the case of the Monstrous Compendium, there are at least a couple of topics worthy of examination. The MC was conceived as a successor to not just the original 1977 Monster Manual but to all the monster books previously published, as well as the sections at the back of many adventure modules that detailed new foes. The Big Idea of the Compendium was that it was tedious, not to mention unwieldy, for the referee to be forced to consult multiple books and supplements in the course of a game session. Wouldn't it be better, went the logic of 2e's designers, if the Dungeon Master only needed to look at the handful of pages containing the game statistics of the monsters he needed for the session?

That's why the Monstrous Compendium consisted of a large binder, complete with cardstock dividers festooned with D&D art. Monster descriptions appeared on loose, three-hole punched sheets that could then be added to the binder. The idea was that, before playing, a referee could simply remove those sheets he needed and leave the rest in the binder, thereby lessening the burden of carrying multiple reference works. As expansions of the MC appeared, each with its own set new loose sheets, they could be added to the binder, too, slotted in alphabetically so that the end result was, if you'll pardon the expression, a truly monstrous compendium of all the game's foes.

It's frankly a great concept and one that sold me on the Monstrous Compendium sight unseen. Unfortunately, the actual design of the loose sheets left much to be desired. First and foremost, very few monsters have descriptions lengthy enough to occupy both the front and back of a single sheet. This means that, for example, "goblin" is on one side of a sheet and "golem, general" – the first part of a three-page spread – is on the other. While there are a few monsters that do have entries that cover both the front and the back of the same sheet, this is uncommon. This arrangement makes it impossible to add new monsters from expansions into the alphabetical order of the initial release, not to mention undermines the notion that the loose sheets give the referee the ability to choose only those monsters he wishes to use.

Being a lover of order, I can't tell you how much this drove me up a wall. As I said, I was completely sold on the idea of the Monstrous Compendium. Truth be told, I still am. However, as released, it simply did not live up to that promise and indeed worked against it. The situation was only made worse with each new expansion, since my binder grew ever more full with more loose sheets, each of which had to go in its own separate section segregated by one of those cardstock dividers. Eventually, I had to buy additional binders, since I believe TSR only ever released one more of them (with Dragonlance monsters). In the end, I had just as many "books" to lug around as before and these were nowhere near as sturdy as the older AD&D volumes.

This brings me to the second topic I briefly wanted to discuss in relation to this product: the ever-greater commodification of D&D (and RPGs more generally). One of the "problems" with roleplaying games, from the point of view of their publishers anyway, is that, once one owns the basic rules material, there's never any need to buy anything more. That's why, since fairly early on in the history of the hobby, publishers have contrived ways to extract more money from players. I suspect that the design of the Monstrous Compendium was at least partially intended as a way to get players to buy more stuff – regular updates and expansions, more binders, etc.

That intention was hampered by the shortsighted design of the MC itself, resulting in TSR's eventual abandonment of it with the release of a hardcover volume called the Monstrous Manual in 1993, followed by a number of softcover appendices to it in the years that followed. I'm amazed that TSR didn't course correct sooner than this, but the management of AD&D in the '90s was haphazard at the best of times. It's a shame, because, as I noted earlier, I think a more "user friendly" approach to monsters has a certain appeal. Alas, the Monstrous Compendium did not provide that approach, which is why it remains, to this day, one of the most disappointing D&D products I've ever bought.

July 11, 2023

White Dwarf: Final Thoughts

Having come to the end of my look back at the first 80 issues of White Dwarf last week, I thought, before launching a new series, I'd offer some final thoughts on the UK's most successful and influential "games monthly."

Having come to the end of my look back at the first 80 issues of White Dwarf last week, I thought, before launching a new series, I'd offer some final thoughts on the UK's most successful and influential "games monthly."As I noted in my original retrospective on White Dwarf almost fifteen(!) years ago, I was an irregular reader of the magazine during my youth. I'd pick up an issue here or there, as I could find them and subscribed to it between 1983 and '85, but I was never as devoted to White Dwarf as I was to Dragon during my formative years in the hobby. Consequently, until I'd made the effort to work my way through its first 80 issues for this series, I can't honestly say that I had a truly good sense of White Dwarf' and its place in the history of the hobby. With the benefit of my recent education, I know a little better, though still in a slightly more "academic" way than those of you, both in Britain and elsewhere, who experienced the magazine in its original run.

I'm left with three insights I'd like to share. The first is a direct result of my having grown up on the other side of the Atlantic, namely, that White Dwarf was a window on another part of the hobby that I otherwise would never have seen. Hard as it is to remember now, given the speed and ease of contemporary telecommunications, the world of the late '70s and early '80s was much more divided and diverse. Certainly, there were global fads and trends, but they took longer to spread and, even when they did, they often manifested in unique ways in each country where they took hold. This is something I genuinely miss about the past, especially when compared to bland corporate slurry that predominates in so many fields today.

White Dwarf revealed to me, growing up in suburban Baltimore, Maryland, what roleplaying was like in Great Britain. I was frequently surprised not merely by the differences in content – the preponderance of RuneQuest articles during the time I was a subscriber, for example – but also by the differences in subject matter and presentation. White Dwarf's artwork was utterly unlike anything I'd seen in Dragon – dark, bizarre, and waggish, by turns gothic and punk. I didn't always like it, but it always held my attention, no doubt because it was genuinely different than the increasingly safe, antiseptic house style of TSR. Likewise, the content of most issues displayed a similar difference from what I was used to – a greater use of history, horror, and, of course, humor. Reading White Dwarf, there was never any question I was reading the product of another culture and that was (and is) quite appealing.

My second insight is that White Dwarf seems to have retained the madcap, chaotic energy of the early hobby longer than did Dragon or indeed most of the hobby on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. To some extent, this slightly scruffy, rough around the edges style became Games Workshop's brand identity, so it's possible that this seeming atavism might simply have been very good marketing. Still, there's no denying that it's slightly intoxicating, even at several decades' remove. One of the things I really enjoyed about reading and re-reading the issues I covered in this series is once again feeling the vigor and enthusiasm of youth. I could sometimes feel the excitement of an article's author, the desire to share this absolutely crazy idea he hit upon one day while playing D&D with his mates one Saturday night. It's amazing stuff and, while this didn't always translate into a good or even usable article, I can't help but appreciate the fervor that engendered it.

Thirdly, and relatedly, I'd say that, when White Dwarf started to decline, its decline seemed far starker than that of Dragon. In part, I think that's because WD stayed closer to the wild, untidy roots of the hobby for longer into its run, making its eventual transition to a slick, safe house organ that much more apparent. Despite this, the magazine continued to offer up excellent articles until the very end of the time that I was reading it. Indeed, I have little doubt that, had I continued to do so, I'd have continued to find good material in its pages, maybe even great material. Yet, I also know that, by the tail end of the 1980s, White Dwarf was no longer the shambolic, quasi-amateur periodical that it had been at the start of the decade and that's a shame. What I most liked about White Dwarf, then and now, was its vitality. After a certain point – precisely when is probably hard to pin down – it was no longer a feral animal but a caged one.

Like Dragon, White Dwarf is one of the places where the hobby as we know was nurtured. It was the crucible of so much that has subsequently come to be known as "British fantasy," as well as the launching pad for the careers of many writers who would later gone to have a profound influence not just on the hobby but on fantasy and science fiction as well. Though it's still running to this day – the same cannot be said of Dragon or indeed any gaming magazine of my youth – it's a hollow imitation of what it was once was, not to mention a reminder of just how good it was in its early days. We shall not see its like again.

July 10, 2023

"So OSR That It Died and Came Back"

That said, the entire video, lasting about an hour, is worth watching, especially if, like me, you're out of the loop about the current state of the OSR blogosphere. I found this very helpful, since I'm no longer as plugged into the Old School scene as I used to be. Much of that is the result of simply falling out of the habit during this blog's hiatus, but some of it is due to a sense, perhaps false, that blogging is no longer as integral to online discussion of RPGs, OSR or otherwise, as it once was. The very fact that I'm discussing a video demonstrates, I think, that the center of gravity has shifted over the last few years toward that medium, leaving blogs and forums, which were once the crucibles of the OSR, lagging behind.

Unless I'm wrong, of course. As I said, I no longer have my finger on the pulse of anything really, including the OSR or its many descendent esthetic movements. It's very possible – likely even – that I am misinterpreting the present situation. From where I'm sitting, though, it seems as if almost everyone has a Youtube channel or a podcast (even I have a podcast, albeit one with a very narrow focus) and that it's on those platforms where the kinds of in-depth analyses and discussions that used to characterize the blogosphere are taking place. That's why I've often considered doing something more seriously with them myself, but the truth is I am probably too old and resistant to change (not mention largely lacking in the technical skills necessary to do this successfully) to make it work, hence my sticking with this blog rather than "upgrading" as others have done.

What are your thoughts on this? Do blogs still have relevance or have they been superseded by videos and podcasts?

July 9, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Thief of Forthe

The death of Robert E. Howard on June 11, 1936 was a huge blow, not simply to his many friends and admirers, but also to the incipient genre of sword-and-sorcery. While it would be an exaggeration to claim that REH is solely responsible for its creation and popularization, there can be little question that his tales of Conan the Cimmerian played an outsize role in popularizing them among the readers of Weird Tales in the 1930s.

The death of Robert E. Howard on June 11, 1936 was a huge blow, not simply to his many friends and admirers, but also to the incipient genre of sword-and-sorcery. While it would be an exaggeration to claim that REH is solely responsible for its creation and popularization, there can be little question that his tales of Conan the Cimmerian played an outsize role in popularizing them among the readers of Weird Tales in the 1930s. Consequently, as news of Howard's death spread, several authors stepped forward in an attempt to fill the void he left in the Unique Magazine's pages. One of these was Clifford Nankivell Ball, who, by his own admission, had been "a constant reader" of Weird Tales since 1925. A huge fan of Conan's adventures, he mourned the demise of REH in the magazine's letters column, the Eyrie, in early 1937. However, rather than simply mourn, Ball wrote six original sword-and-sorcery short stories of his own, all of which were published in WT between May 1937 and November 1941.

Though Ball's first published story was "Duar the Accursed," far more interesting to me is his second effort, "The Thief of Forthe," which appeared two months later, in July 1937. Apparently, editor Farnsworth Wright must have also thought well of the story, since he gave it the cover illustration for the issue – and by Virgil Finlay no less! The titular thief is Rald, "prince among thieves," who, at the start of the tale, has been summoned into the presence of the magician Karlk.

The magician was of slender frame, of small features, and delicate hands and feet. He had never appeared in any other costume than the one he now wore – a long robe of ebon silk almost touching the ground as he walked, held by a twisted cord at the waist. A black cowl covered his head; the heavy beard and hirsute growth bear the ears left only the flashing malignant eyes and the thin nostrils visible. There were many whispers to the effect that Karlk was not really of the race of men and that if anyone would have the unthinkable courage to uncover this person, he would discover, not a human form, butn some monstrosity impossible for the mind of mankind to imagine.

Rald, meanwhile, wore only a "breech-clout ... and the sandals on his feet," as well as a "slender sword dangling by his side." He is "clean-shaven, his hair bound in the back by a gold chain," with "great scars" across his body to indicate that "he had known the clash of steel in combat." Most importantly, his "well-shaped skull gave proof that brain backed his brawn." This is an important detail, since Rald demonstrates again and again throughout the story that he became "prince among thieves" as much by the use of his wits as by his sword.

He asks the magician why he has summoned him, to which Karlk replies simply, "I wish you to steal something for me."

Of course you want me to steal! For what other purpose would you summon Rald? What seek you, wizard, that your magic cannot obtain? Some of [King] Thrall's jewels? – a stone or two from the Inner Temple? No women, mind you! I don't deal in them. What is the bargain and what is my reward?

Rald expanded his chest; he was proud with the pride of an expert in his profession.

Karlk laughed shortly, wickedly. "Jewels? The prizes of the temples? Ha! From the playgrounds for children unlearnt in the mysteries of the skies! I see a great prize, something so earthly my unearthly hands cannot touch it without the aid of your nimble fingers, oh Rald! I seek the kingdom of Forthe!"

Shocked, the notorious thief started upright in the stone chair. Bewilderment strained his countenance; incredulity stamped horror on his features as he sought to comprehend blasphemy.

"Forthe!" he exclaimed. "Forthe! Why – none but the Seven Gods could steal Forthe from King Thrall of the Ebon Dynasty!"

"Except Karlk," amended the magician.

What Ball might lack in polish, he makes up for in enthusiasm – and intriguing ideas. I must confess that, before I began "The Thief of Forthe," I was unsure what to expect. The fact that Ball was a self-professed fanboy of Robert E. Howard who'd never written a word of fiction before 1937 didn't fill me with much hope. Likewise, the start of the tale, with its ponderous descriptions and portentous dialog, led me to expect very little of value. Yet, as I reached the section above, in which Karlk explains to an unbelieving Rald his intentions, I can't deny that my interest was piqued.

"Steal Forthe!" muttered Rald. "Rebellion – treachery – millions to bribe – for what? A powerful kingdom – aye! But who shall rule it, granting you gain it? You with the blood of its peoples on your hands and the terror of yourself in their hearts?"

The magician's voice became a whisper. "King Rald!" he said.

Mine is not the only interest that was piqued. Karlk's bargain is that, in exchange for his assistance in helping Rald steal the kingdom of Forthe from its current ruler, he would be granted a "voice behind the throne," as well as "just a little more freedom for – experiments." Rald is not keen on this bargain, but he "dreamed a dream of empire, as many powerful men had done before" and so agreed to enter palace to steal "the legendary Necklace of the Ebon Dynasty."

The Necklace was composed of a string of fifty diamonds, each one itself worthy of the ransom of a king, and the lot, in their magnificent entirety, of fabulous value. But the chief virtue of the heirloom lay not in its marketable worth, but in the legendary credits supposedly bestowed upon it by the multiple blessings of the Seven Gods when, eons ago, they granted the rights of kingship to the Ancient One who had been the first King of Forthe and the subsequent founder of the dynasty.

Naturally, Karlk imagines that, once Rald is acclaimed king by virtue of his possession of the Necklace of the Ebon Dynasty, he would have no trouble bending the thief to his will, "pull[ing] strings to make the puppet dance."

"The Thief of Forthe" is clearly the work of a novice writer, imitating the style and subject matter of a more accomplished author whom he admired. Despite this, the plot is genuinely interesting and the twists and turns it takes unexpected but fairly satisfying. The story, though rough, holds a lot of promise. I can't help but wonder what might have become of Ball had he continued writing after 1941. With more experience, I suspect he might well have honed his craft and come closer to achieving his goal of filling the void left by Robert E. Howard. As it is, he is mostly an intriguing "what if" in the annals of pulp fantasy. A pity!

July 7, 2023

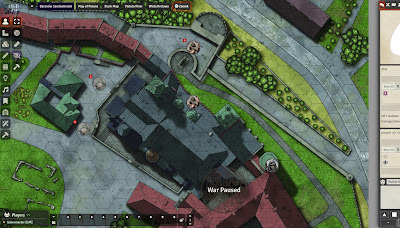

The Old Man and the VTT (Part II)

You may recall that, at the end of last year, I expressed some dissatisfaction with the Foundry virtual tabletop that I was using for my weekly Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign. Though extremely powerful in its functionality, it was also unwieldy and poorly documented, leading to a great deal of frustration on my part. Nevertheless, I decided to continue to use it in the hopes that, over time, I'd grow more adept at using it to its full potential. After all, a great deal of effort had obviously gone into the creation and development of both the Foundry and the Twilight: 2000 add-on module and I wanted to give them both a fair shake.

You may recall that, at the end of last year, I expressed some dissatisfaction with the Foundry virtual tabletop that I was using for my weekly Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign. Though extremely powerful in its functionality, it was also unwieldy and poorly documented, leading to a great deal of frustration on my part. Nevertheless, I decided to continue to use it in the hopes that, over time, I'd grow more adept at using it to its full potential. After all, a great deal of effort had obviously gone into the creation and development of both the Foundry and the Twilight: 2000 add-on module and I wanted to give them both a fair shake. A couple of sessions ago, as the characters prepared to infiltrate Baranów Sandomierski Castle, I finally reached the limit of my patience with the VTT. I won't waste time with a summary of all the issues I encountered during that session. I will only say that they were sufficient that I seriously considered abandoning the campaign entirely. Before I took such a rash step, however, I spoke to my players about my frustrations and discovered that they largely felt similarly about the situation. Since everyone was enjoying the campaign, we simply decided to abandon the use of the VTT for future sessions, opting instead for simple sketch maps on a Jamboard rather than anything more elaborate (this is what I've done in my House of Worms campaign for years now).I know that many people, even people as ancient as myself, regularly make use of virtual tabletops with great success and that their enjoyment of games is greatly enhanced by them. I'm sincerely happy for such people. For myself, though, the opposite has largely been the case. Over the years that I've played online, I have never found an elaborate VTT to offer any significant benefit beyond the storage of character sheets and as a dice roller in games that use funky dice (as Twilight: 2000's current edition does). Most of the time, the VTT worked against my enjoyment of play, in large part because of how arcane they were to operate.

I certainly understand the theoretical appeal of a virtual tabletop. As its name suggests, it's an attempt to emulate the look and feel of playing in person while seated around a common table. As I've said repeatedly on this blog over the years, playing in person is the ideal way to play a roleplaying game and, until the last decade or so, I never even considered playing any other way. That's why I'm sympathetic to the intention behind VTTs and why, in my naivete, I have attempted to make use of them in my online games. None, in my experience anyway, have come close to bringing an online game any closer to being an in person game. If anything, what they have done is make it all the more plain that I am not playing a game face-to-face. They've made it all feel like a clunky, analog video game and what's the point in that?

I've often commented that one of the few unalloyed goods that the Internet has given us is the ability to connect with people all over the globe who share our interests. I've made many wonderful friends over the years because of the Internet, most of whom I'd never have met otherwise. I'm deeply grateful for that. Yet, even as Internet technology has improved, it has still not improved enough that I feel as if a virtual tabletop is a good option for playing a RPG with friends. If refereeing the House of Worms campaign over the last eight years has taught me anything – and it's taught me a lot – it's that simple is best. The online experience can never replicate, let alone replace, being there in the flesh, rolling actual dice with your friends, of course, but the fewer layers of mediation between you and your friends, the closer you come to it. That's why I'm giving up on the Foundry for Barrett's Raiders and going as bare bones as possible. In retrospect, that's probably what I should have done from the beginning.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers