James Maliszewski's Blog, page 68

September 1, 2023

Memories of Game Stores Past II

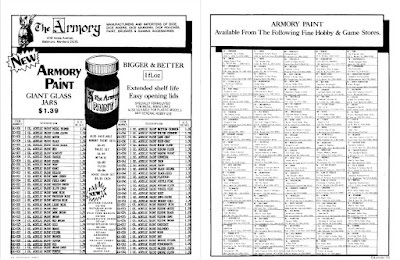

One of the things I most enjoy about reading gaming magazines like Dragon is looking at the advertisements. They're a terrific window on the past, not merely the past of the wider hobby but more specifically of my own personal history with it. Consider this two-page advertisement that appeared in issue #90 (October 1984). (Apologies for the smallness of the image below; I'll soon zoom in on a part of it that's relevant to my post.)

The advertisement is for miniature paints sold by The Armory, a Baltimore, Maryland-based manufacturer, distributor, and importer of RPG products. I have very fond memories of visiting their storefront and warehouse on a couple of occasions when I was a teenager. The warehouse was a warren, filled with rows and rows of shelves among which my friends and I would wander, peering into random boxes to see what treasures they might hold.

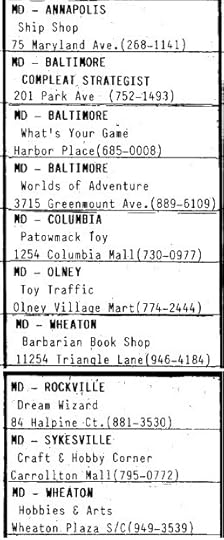

The advertisement is for miniature paints sold by The Armory, a Baltimore, Maryland-based manufacturer, distributor, and importer of RPG products. I have very fond memories of visiting their storefront and warehouse on a couple of occasions when I was a teenager. The warehouse was a warren, filled with rows and rows of shelves among which my friends and I would wander, peering into random boxes to see what treasures they might hold. What struck me about this ad is that its second page includes a listing of the "fine hobby & game stores" in the United States that sold Armory paints. Perhaps because The Armory was itself located in Maryland, there are a significant number of stores in the same state. Here they are:

I remember several of these stores from personal experience of them. The Ship Shop was located not far from the State House and focused primarily on miniatures and wargames, though they also sold some RPGs. A friend of mine worked there during the two years I attended St. John's College. I've talked about The Compleat Strategist before, as well as What's Your Game. Both were located in Baltimore City proper, so I only ever shopped at them when I was visiting my grandparents. I sadly never got to go to the Barbarian Bookshop – great name! – but I know Dream Wizards quite well. When I lived in Washington, DC, I could take the Metro to Twinbrook station to reach it. Of all the stores on this list that I patronized, it's the only one that definitely still exists.

I remember several of these stores from personal experience of them. The Ship Shop was located not far from the State House and focused primarily on miniatures and wargames, though they also sold some RPGs. A friend of mine worked there during the two years I attended St. John's College. I've talked about The Compleat Strategist before, as well as What's Your Game. Both were located in Baltimore City proper, so I only ever shopped at them when I was visiting my grandparents. I sadly never got to go to the Barbarian Bookshop – great name! – but I know Dream Wizards quite well. When I lived in Washington, DC, I could take the Metro to Twinbrook station to reach it. Of all the stores on this list that I patronized, it's the only one that definitely still exists. I find it fascinating the way that, for so many of us in this hobby, our memories are closely tied to the stores where we purchased our games, dice, and miniatures. In part, I think, that's because, in the past, RPGs, even at the height of their first faddishness, weren't available everywhere. Often, you had to travel to out of the way places to find what you were looking for. It was almost an adventure to get hold of this stuff, especially if, like me, you were young and your knowledge of the world beyond your immediate neighborhood was limited. Good times!

August 31, 2023

Secrets of sha-Arthan: Milesho

A milesho by Zhu BajieThe tombs of Inba Iro hold not bodies but cinerary urns filled with the ashes of the honored dead. Sometimes, whether through sorcery or an incursion of the False World, the twisted shade of one so entombed returns to sha-Arthan, seething with hatred for the living and a desire to spread chaos and destruction.

A milesho by Zhu BajieThe tombs of Inba Iro hold not bodies but cinerary urns filled with the ashes of the honored dead. Sometimes, whether through sorcery or an incursion of the False World, the twisted shade of one so entombed returns to sha-Arthan, seething with hatred for the living and a desire to spread chaos and destruction.Called a milesho, this accursed spirit can form a "body" from its burnt remains. The process of doing so takes 1d4 rounds, during which time it cannot attack and can be harmed by normal weapons. A milesho can also disperse its body at will so as to attempt to enter and inhabit (see below) a living being. If it fails to do so, it is then vulnerable to normal weapon for a round, as it reforms from its ashes.

DR 20, LVL 10 (45hp), Att 1 × weapon (1d10) or touch (Vigor drain) or inhabit, AB +8, MV 90' (30'), SV F6 D7 M8 E9 S10 (10), ML 10, NA 1 (1), TT E, N, O

• Undead: Makes no noise, until it attacks. Immune to effects that affect living creatures (e.g. poison). Immune to mind-affecting or mind-reading disciplines and spells.• Mundane weapon immunity: After forming its ashen body, only harmed by spells or magic weapons.

• Weapon: Capable of wielding any weapon available with great power (dealing 1d10 damage, regardless of type). If treasure includes magic weapon, the milesho will make use of it. • Vigor drain: Victim permanently loses 1 VIG per hit. If reduced to 0 VIG, the victim dies. Lost Vigor cannot be restored through the usual methods (advancement, training, etc.), but several mystery cults of the Eternal Gods (see Alignment ) are reputed to have the means of doing so.

• Inhabit: A living being within range must make a mind save or become inhabited. Failure indicates the milesho gains control of the being's body (but not mind, including his spells or disciplines). The ashen spirit retains control until it relinquishes it, the inhabited being dies, or dispel is successfully used against it.

August 30, 2023

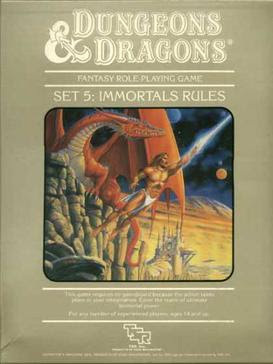

Retrospective: Dungeons & Dragons Immortals Rules

In the early days of the OSR, a common topic of discussion was D&D's endgame. Both OD&D and AD&D assume that player characters, when they have achieved higher level, will settle down to rule baronies and become movers and shakers within the campaign world. There's little disputing this, since even a cursory reading of the rules reveals that this was clearly the intention of the game's creators. Unfortunately, neither game provided much in the way of explicit rules or even guidance on what this intended endgame would look like in practice, which no doubt contributed to its loss.

In the early days of the OSR, a common topic of discussion was D&D's endgame. Both OD&D and AD&D assume that player characters, when they have achieved higher level, will settle down to rule baronies and become movers and shakers within the campaign world. There's little disputing this, since even a cursory reading of the rules reveals that this was clearly the intention of the game's creators. Unfortunately, neither game provided much in the way of explicit rules or even guidance on what this intended endgame would look like in practice, which no doubt contributed to its loss. It wasn't until the release of Frank Mentzer's Companion Rules boxed set in 1984 that D&D players were a clearly stated version of D&D's intended endgame, however inadequate one might judge it (I personally liked it, but I recognize that not everyone feels the same). However, for reasons I've never understood, the Dungeons & Dragons game line, starting with the beloved revisions of Moldvay, Cook, and Marsh, was obsessed with the number 36 as the highest possible level attainable by a character. That's why Mentzer followed the Companion Rules with the utterly pointless Master Rules : to fill in the level progression gap between 25 (the top level of Companion) and 36, the inexplicably Highest-We-Mean-It-This-Time level for D&D.

Given the vacuity of the Master Rules, one might be forgiven for thinking Mentzer had finished with his revision, having provided rules coverage all the way up to the lofty heights of Level 36. You'd be mistaken, of course, because Mentzer had one more trick up his sleeve and it was a doozy. 1986 saw the release of the fifth and final boxed set for Dungeons & Dragons, the Immortal Rules. As its title suggests, this set focused on characters who had achieved, in the words of its preface, that "most ambitious of goals – Immortality itself." Now that's an endgame.

I should immediately note that becoming an Immortal is not the same thing as becoming a god – or at least not exactly. The Immortal Rules appeared during the "angry mothers from heck" era of TSR, when the company was doing everything it could to avoid giving offense to Middle America. That meant eliminating or scaling back anything that skirted too close to religion or religious belief. Hence, Immortals, though they "oversee and control all the known multiverse," are explicitly not its creators. More importantly, Immortals do not seek – or receive – the veneration or worship of mortals. Instead, they have their own goals, which largely consist of exploring and understanding the mysteries of the multiverse and its infinite planes beyond the Prime.

The rules governing Immortals are clearly derivative of those in Dungeons & Dragons – there are, for example, still six ability scores, armor class, hit points, etc. – but most of them have been thoroughly re-imagined or re-contextualized – so much so that they're scarcely the same game anymore. Most importantly, a character accumulated experience points are converted into power points on a 10,000 to 1 basis and those power points are used by the player to purchase talents and abilities for his now-Immortal character. As an Immortal learns more about the multiverse, he acquires more power points, just as normal characters acquire XP. These new points can then be used to buy new abilities and to advance within the Immortal hierarchy.

What Mentzer has done here is effectively turn D&D into a more freeform point-buy system that is wholly unlike the class-based structure of "ordinary" Dungeons & Dragons. I remember, when I first read the rules, shortly after they were published, just how odd it all seemed to me. Now, to be fair, I had absolutely no idea what the Immortals Rules should look like. For that matter, I wasn't even sure that there was much point to rules for player character immortality. All I can say is what I expected and that was something similar to the D&D rules of levels 1–36, though at a greater scale.

That's not say that what Mentzer does in the Immortal Rules isn't interesting, because I think it is. He clearly had a strong idea of what Immortals were within the cosmology he'd created for the game and, knowing that, the kinds of powers and abilities they should possess. Then, as now, the question is one of why? Did anyone really want these rules? Did anyone ever use them in play? I certainly never did. I read them a couple of times and then largely forgot about them – not because they were badly done but because they scratched an itch I'd never had. Re-reading them in preparation for this post, I can't help but think that the Immortals Rules existed only to fulfill some vague sense that D&D had to include rules for immortality eventually.

I suspect my own interest in the Immortal Rules might have increased considerably had Mentzer done a better job of fleshing out just what Immortals did. He talks a lot about exploration of the multiverse and of learning its secrets, but, aside from a few small details here and there, he doesn't provide any practical examples – in a way, recapitulating the problem of D&D's original endgame. It's a shame, because I think there might have been room for a wild and woolly multiversal game at the pinnacle of D&D's level progression. That's certainly in keeping with some of the stuff with which Gygax had long been toying, so it's not in any way alien to Dungeons & Dragons.

Mentzer's reach exceeded his grasp with the Immortal Rules, which is no crime – but it is a disappointment.

August 29, 2023

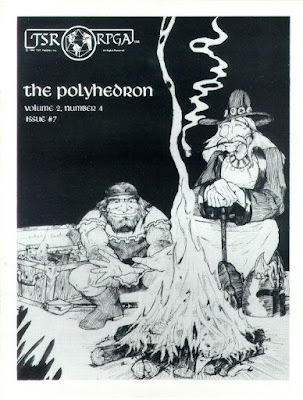

Polyhedron: Issue #7

Issue # 7 of Polyhedron (August 1982) once again features a cover artist – Scott Roberts – with whom I am unfamiliar. I find this fascinating, as it suggests that the staff of the 'zine wanted to cultivate a unique look for the periodical, one that was distinct from that of Dragon, even though both were published by TSR. True or not, this trend lessened somewhat as Polyhedron's run continued, as we'll see in future posts in this series.

Issue # 7 of Polyhedron (August 1982) once again features a cover artist – Scott Roberts – with whom I am unfamiliar. I find this fascinating, as it suggests that the staff of the 'zine wanted to cultivate a unique look for the periodical, one that was distinct from that of Dragon, even though both were published by TSR. True or not, this trend lessened somewhat as Polyhedron's run continued, as we'll see in future posts in this series. The issue begins with Frank Mentzer's last(?) "Where I'm Coming From," in which he briefly recounts the founding of the RPGA and the role he and others played in that. Then, he announces that "it's time for me to move on," as he will soon be "very, very busy working with Gary." He explains that he will "essentially ... be #2 right after Gary when it comes to D&D® rules and AD&D™ games, and so forth." This is obviously a reference to his oversight of the revision of Dungeons & Dragons game, as well as his assistance in getting things like The Temple of Elemental Evil completed, both of which earned Mentzer a lasting place in the history of the hobby.

The letters page includes the following:

This letter hits home, because I remember well the first few years after I discovered D&D and other RPGs. They were most definitely obsessions for me – not to the extent that they affected my schoolwork and other responsibilities, but I certainly devoted a lot of time to playing and preparing to play them.

This letter hits home, because I remember well the first few years after I discovered D&D and other RPGs. They were most definitely obsessions for me – not to the extent that they affected my schoolwork and other responsibilities, but I certainly devoted a lot of time to playing and preparing to play them. "Dispel Confusion" contains a number of interesting questions and answers this issue. For example, one reader asks about the level at which a ranger casts druid and magic-user spells in AD&D. The answer is that, at the time a ranger gains access to a new type of spellcasting, he casts those spells as if he were 1st level in the appropriate class. Thus, a ranger gains druid spells at 8th level in his class but casts those spells as if he were a 1st-level druid. The same is true of magic-user spells, which a ranger gains at 9th level. I believe I already knew this, but it was fascinating to be reminded of it. Additionally, there's this question and answer:

I have no strong feelings about this matter one way or the other, but I do think the reasoning here is worthy of note. Also notable is the way that Mentzer, who provided this issue's answers, mentions that he agrees with "Gary" on this point – another example of the Cult of Gygax that was popularized in the pages of TSR periodicals.

I have no strong feelings about this matter one way or the other, but I do think the reasoning here is worthy of note. Also notable is the way that Mentzer, who provided this issue's answers, mentions that he agrees with "Gary" on this point – another example of the Cult of Gygax that was popularized in the pages of TSR periodicals."RPGA Interview with Mike Carr" is exactly what you'd expect: an extensive interview with Mike Carr, who was at this point Executive Vice President of TSR's Manufacturing Division. From my perspective, the interview is quite good, focusing a lot on the early days of both the hobby and TSR. It's also very clear, as if there were any doubt, that Dawn Patrol means a lot to Carr, since he mentions it often in his answers. "Spelling Bee" looks at clerical and druid spells, providing some thoughts on their use in play. Of interest is the following note about know alignment: "Often cast at the beginning of an adventure, it's aimed at 1, 2, or 3 creatures, all of whom (except the Lawful Goods) should retaliate by disrupting the casting, leaving the area quickly, or some other equally rude action."

Gary Gygax offers a very short piece entitled "Notes from the DM," in which he holds forth on the matter of AD&D's one-minute combat round and "detailed combat." All of this old hat to those of us who've seen Gygax discuss this in other places. However, the fact that he needs to keep trying to justify it goes a long way, I think, to explain why it would eventually be abandoned in contemporary versions of the game (and, it should be noted, in Dungeons & Dragons, including the edition that Mentzer himself would develop).

"Campaign Clues" by Corey Koebernick, husband of Jean Wells, offers advice to Top Secret referees (or Administrators) on starting espionage campaigns. Meanwhile, Bill Fawcett's "Ranch Encounters" is a collection of random encounters for use with Boot Hill. One of the upsides of Polyhedron's narrow focus on TSR RPGs is that each issue is likely to contain articles devoted to some of these "lesser" games that my friends and I played. That's something that mattered a lot to me at the time, since Dragon tended not to include many articles of this sort, at least not when I was a regular reader (the day of the Ares Section being a significant exception).

"Notes for the Dungeon Master" takes a look at higher-level characters. At the start of the article, Frank Mentzer, the author, mentions that "looking at the data we've received from hundreds of DMs worldwide, it seems the average advancement of a character is about 2–3 levels per year." That jibes with my own experience of playing AD&D around this time, though I also recall a few outliers who achieved higher levels, mostly due to being played very often (and perhaps a little greater generosity of XP on my part).

This issue marks the first appearance of the RPGA Gift Catalog about which I've written before. I still get a kick out of looking at it even now, because it's such a wonderful artifact from the days of D&D's faddishness. "Convention Wrapup" briefly reports all the happenings at various conventions across the USA during the previous months. As one would expect, there's much emphasis on RPGA events, including the winners of tournaments, who are listed by name. I always keep an eye out, to see if I recognize any notable individuals among the winners. Finally, there's Roger Raupp's comic, "Nor." Sadly, the comic continues to plod along without any obvious direction and there's still no follow-up to the crashed spacecraft from its very first installment.

Oh well, there's always next issue, the very first one I ever owned.

August 28, 2023

A Means to Freedom

It should come as a surprise to no one who reads this blog that I have never ridden a motorcycle. I have, on the other hand, known a good number of motorcycle enthusiasts, including my childhood next door neighbor, who had been a member of a motorcycle club during his own youth in the '60s. One of the questions I'd eventually ask all these men – and they were always men; I never met a female biker, unless you count my neighbor's wife, who'd sometimes ride along with him – was why they rode and their answer was usually some variation on "I love the freedom."

It should come as a surprise to no one who reads this blog that I have never ridden a motorcycle. I have, on the other hand, known a good number of motorcycle enthusiasts, including my childhood next door neighbor, who had been a member of a motorcycle club during his own youth in the '60s. One of the questions I'd eventually ask all these men – and they were always men; I never met a female biker, unless you count my neighbor's wife, who'd sometimes ride along with him – was why they rode and their answer was usually some variation on "I love the freedom."As if to confirm my own lack of cool, I can't deny that this answer used to baffle me a little bit. Even in 1970s America, which was vastly less obsessed with safety than today, there was already public concern about the deadliness of motorcycles. Consequently, my youthful self absorbed the notion that motorcycles were coffins on two wheels, a notion reinforced by my neighbor's accident, which left him on crutches for a long time and eventually led to his trading his Triumph bike for a "cage."

"Cage" is a relevant bit of slang to this discussion, because it touches on the sense that an automobile is a prison of sorts, trapping the driver inside, and taking away his freedom. I'm not all that fond of cars – even less so since I was hit by one the day before my fiftieth birthday – so even the thought of speeding down the highway with only my clothes and a helmet to protect me is terrifying. But I suppose one man's terror is another man's freedom, or at least that's the impression I've got from talking to avid motorcyclists over the course of my life.

Shortly before my parents were married, my father was inducted into the US Army and received orders to go to Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona, a very short distance from the Mexican border. So, for their honeymoon, he and my mother drove across the country to reach his posting, along the way stopping at a number of fascinating places. This trip, as well as a later one that took my parents to a NATO Joint Forces base in the Netherlands, profoundly affected my father for the rest of his life, largely, I think, because he got to see more of the world than he otherwise would have.

Shortly before my parents were married, my father was inducted into the US Army and received orders to go to Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona, a very short distance from the Mexican border. So, for their honeymoon, he and my mother drove across the country to reach his posting, along the way stopping at a number of fascinating places. This trip, as well as a later one that took my parents to a NATO Joint Forces base in the Netherlands, profoundly affected my father for the rest of his life, largely, I think, because he got to see more of the world than he otherwise would have.One lasting effect was on my Dad's taste in food. He came to love spicy foods, no doubt due to his proximity to Mexico during the first part of his military tour. He passed that love down to me. Judging by what I see on grocery store shelves and on restaurant menus, the love of spicy food seems increasingly commonplace. Nowadays, you can find spiced-up versions of just about anything, from baked goods to desserts to drinks. I've seen jalapeño and chipotle-spiced chocolate, for example, and these are pretty ordinary compared to some of the other foods out there.

Indeed, there seems to be an arms race when it comes to spiciness, with ever more absurdly hot peppers being cross-bred and used for sauces and flavoring. I'm talking peppers rated a million Scoville units or more – stuff that can literally harm your body in certain cases. As I said, I enjoy spicy foods quite a lot, but I simply don't see the appeal of eating peppers so spicy that I doubt one's taste buds can even register their flavor – but maybe that's not the point. Maybe the point is simply to experience something unique, even extreme by the standards of everyday 21st century life.

In one of his letters to H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard wrote:

In one of his letters to H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard wrote:“I think the real reason so many youngsters are clamoring for freedom of some vague sort, is because of unrest and dissatisfaction with present conditions; I don't believe this machine age gives full satisfaction in a spiritual way, if the term may be allowed.”

As one might expect from the creator of the legendary wanderer, Conan the Cimmerian, Howard devoted much thought to the question of freedom and its importance to the well-being of the individual in an increasingly, as he called it, "machine age," by which he meant the ever more regulated, narrow, and "safe" world that was already being birthed during his lifetime. That's why he "yearn[ed] for the days of the early frontier, where men were more truly free than at any other time or place in the history of the world."

Whether one agrees with him or not is immaterial. What's important to remember is that Howard very much believed this and nearly all of his fiction was an attempt to transport readers – and I daresay himself – to times and places that were, in his judgment, freer and, therefore, uplifting to the human spirit. Again, one can quibble as to how well REH achieved this emancipatory goal, but there can be no question in my mind that he saw literature as a possible means of escape from the soul-crushing drudgery of the modern world.

"Who are the people most opposed to escapism? Jailers!" That sentiment, or others similar to it, is often attributed to J.R.R. Tolkien, though other authors (C.S. Lewis, Arthur C. Clarke, et al.) sometimes take his place. Regardless of its origin, it's an interesting point of view and that, I suspect, with some minor caveats Robert E. Howard would have agreed with, as might bikers and pepper-eaters – and roleplayers.

"Who are the people most opposed to escapism? Jailers!" That sentiment, or others similar to it, is often attributed to J.R.R. Tolkien, though other authors (C.S. Lewis, Arthur C. Clarke, et al.) sometimes take his place. Regardless of its origin, it's an interesting point of view and that, I suspect, with some minor caveats Robert E. Howard would have agreed with, as might bikers and pepper-eaters – and roleplayers.I sometimes find myself wondering if the growth in the popularity of not just tabletop RPGs, but fantasy more generally, is a symptom of a larger malaise with modernity, specifically its lack of frontiers or places to adventure. When I was a kid in the '70s, it was still possible – just barely – for me to imagine the opening up of our solar system (and beyond) for exploration. Now, though, I think that's probably a pipe dream, something confined to the realm of science fiction rather than reality.

I'm grateful I had those dreams of traveling to the Moon or Mars when I was younger, just as I'm grateful for the escape provided, then and now, by roleplaying games. Perhaps it speaks poorly of me that I consider many of my RPG experiences as among the most fulfilling and indeed liberating ones I've had in my life. They're not the only ones, of course, but that doesn't change the fact that they've been immensely important to me and, I know, to many of my friends as well.

August 25, 2023

That New Car Smell

Is there anything more intoxicating than the promise of a new campaign? Whether you're the referee or a player, the vast horizon of possibility that a new campaign lays before you is a feeling like no other in the hobby. I thought about this the other day because a friend was preparing to start up a new campaign and I must admit that, in hearing about it, I was more than a little bit envious.As you probably know, I'm currently refereeing two different RPG campaigns: the House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, currently starting its ninth year; and the Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign (now in its second year). Both continue to chug along each week and I – and my players, so far as I can tell – continue to enjoy them. Nevertheless, even I am not immune to the scourge of gamer attention deficit disorder, particularly when I hear about others trying something new with their own group of players.

Is there anything more intoxicating than the promise of a new campaign? Whether you're the referee or a player, the vast horizon of possibility that a new campaign lays before you is a feeling like no other in the hobby. I thought about this the other day because a friend was preparing to start up a new campaign and I must admit that, in hearing about it, I was more than a little bit envious.As you probably know, I'm currently refereeing two different RPG campaigns: the House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, currently starting its ninth year; and the Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign (now in its second year). Both continue to chug along each week and I – and my players, so far as I can tell – continue to enjoy them. Nevertheless, even I am not immune to the scourge of gamer attention deficit disorder, particularly when I hear about others trying something new with their own group of players.It's a fascinating phenomenon. I used to think – and, to some extent, still do – that gamer ADD is largely a consumerist impulse facilitated by how many RPGs are now competing for your time and attention. In the early days of the hobby, this impulse was probably less powerful, though still far from non-existent. I remember how my friends and I used to bounce from one campaign to the next. Of course, back then, we also had a lot more free time to devote to such things, so it was genuinely practical to have multiple campaigns running in parallel to one another.

Nowadays, that's nowhere near as practical. I'm fortunate to have a large pool of devoted and enthusiastic players from which to draw, but very few of them could play in multiple campaigns at the same time. Moreover, I'm fairly certain that, were I to pause one of my current campaigns for any length of time to take up a new game for even a little while, it'd likely deplete the momentum of – and perhaps even interest in – the original. Better instead to avert my eyes and not give into temptation.

Yet the temptation remains.

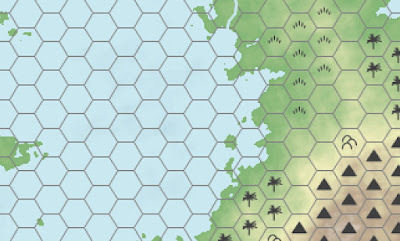

Map Assistance

As I mentioned recently, I'm trying to put together a map for Secrets of sha-Arthan. I've already got a continental outline for the whole world, but my focus at the moment is on a smaller region intended as a "starting area" for new characters and campaigns. Nevertheless, I have several problems and I'm hoping readers might be able to point me in the right direction for solving it.

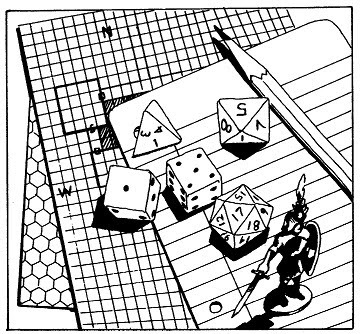

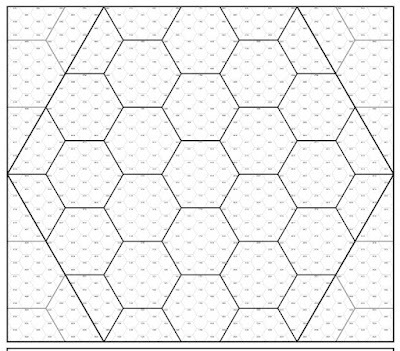

Here's a portion of the continental scale map of sha-Arthan:

Because it's continental scale, those hexes are very large in size – about 90 miles across. That size is based on two factors: that sha-Arthan is roughly the same size as Earth and the number of hexes used in the continental map. I could, I suppose, redraw the continental outlines and then layer on a small hex grid in order to make each hex smaller, but that's something I can't easily do, given my lack of technical skills. If someone can suggest a relatively easy way to do this, so easy that even an incompetent like myself could do it, most of my problems go away.

Because it's continental scale, those hexes are very large in size – about 90 miles across. That size is based on two factors: that sha-Arthan is roughly the same size as Earth and the number of hexes used in the continental map. I could, I suppose, redraw the continental outlines and then layer on a small hex grid in order to make each hex smaller, but that's something I can't easily do, given my lack of technical skills. If someone can suggest a relatively easy way to do this, so easy that even an incompetent like myself could do it, most of my problems go away.Barring that solution, I was intending to break down each 90-mile hex like so:

Done this way, each of the sub-hexes within the 90-mile hexes would be 18 miles across. These 18-mile hexes would be further subdivided into 3.6-mile hexes. Both 18 and 3.6 miles are odd increments, to be sure, but that's what happens if I stick to 90-mile continental hexes. A possible "solution" is to create in-game units of measurements that correspond to 3.6, 18, and 90 miles. On some level, I like that, because it's potentially immersive, but it's also potentially annoying and easy to forget.

Done this way, each of the sub-hexes within the 90-mile hexes would be 18 miles across. These 18-mile hexes would be further subdivided into 3.6-mile hexes. Both 18 and 3.6 miles are odd increments, to be sure, but that's what happens if I stick to 90-mile continental hexes. A possible "solution" is to create in-game units of measurements that correspond to 3.6, 18, and 90 miles. On some level, I like that, because it's potentially immersive, but it's also potentially annoying and easy to forget. Another possibility is to use a different set of divisions for each continental hex. The only reason I went with the five hexes within five hexes set-up above is because I was able to find some templates online. I'm not kidding when I say I am utterly incompetent when it comes to these matters, so it may well be that there are simpler configurations that will serve my purpose – that purpose being breaking down continental scale hexes into small, more manageable ones for use in play.

Any ideas or suggestions you have to share would be appreciated.

August 23, 2023

Retrospective: Traders and Gunboats

I've mentioned before that Star Trek was my first fandom. If you were a kid with an interest in science fiction in the early 1970s, there simply weren't many other options. Despite this, Star Trek wasn't heavily merchandised at the time, certainly not to the extent that Star Wars would be in a few years. Consequently, fans like myself had to make do with a fairly limited selection of Star Trek products to sate our lust for more information about Gene Roddenberry's vision of the 23rd century.

I've mentioned before that Star Trek was my first fandom. If you were a kid with an interest in science fiction in the early 1970s, there simply weren't many other options. Despite this, Star Trek wasn't heavily merchandised at the time, certainly not to the extent that Star Wars would be in a few years. Consequently, fans like myself had to make do with a fairly limited selection of Star Trek products to sate our lust for more information about Gene Roddenberry's vision of the 23rd century.

A couple of items from that limited selection stand out in my memory, both of them created by the German technical artist Franz Joseph Schnaubelt, known by his nom de plume, Franz Joseph. In 1975, Ballantine Books released Joseph's Starfleet Technical Manual and Star Trek Blueprints. Each included lots of beautifully rendered maps and schematics of Star Trek space vessels and technology (and, fascinatingly, served as the basis for Starfleet Battles, but that's another story). Needless to say, I owned and adore both of them, spending countless hours poring over the secrets they revealed about the layout of the USS Enterprise and other Starfleet ships of the line. These books initiated my lifelong love for deckplans of all sorts, but particularly of science fiction vehicles – a love I'd later transfer into the realm of science fiction roleplaying games.

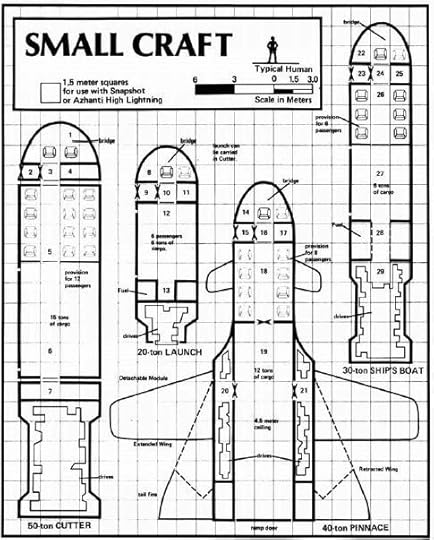

GDW's Traveller, which I first picked up sometime in 1982, was more than accommodating of my love of starship deckplans. Nearly every adventure released for the game, along with many of its supplements, included one or more deckplans of this sort. There were even separate but related games, Snapshot and Azhanti High Lightning, that included deckplans large enough to use with cardboard counters or 15mm miniatures. From the standpoint of someone like myself who loved starship deckplans, Traveller delivered the goods.

Which brings us to the true topic of this post: Supplement 7: Traders and Gunboats. Released in 1980 and written by Traveller's creator, Marc Miller, with assistance from Frank Chadwick, John Harshman, and Loren Wiseman, Traders and Gunboats is a 48-page supplement that provides information on, as its title suggests, merchant starships and patrol craft. The information is not limited solely to game statistics – though there's plenty of such detail – but also includes an equal amount of information on the place of such vessels within GDW's Third Imperium setting. The inclusion of both game mechanical and setting information makes Traders and Gunboats equally useful to players and referees, as well as to those using Traveller's official setting or one of their own creation.

Ultimately, what makes Supplement 7 so appealing to me is its practicality. All of the space vessels described in its pages are small in size. The largest is no more than 1000 displacement tons, but the vast majority are in 100–400 ton range, which makes them perfect for use by – or against – player characters. That's one of the things that's always appealed to me about Traveller: it keeps its focus on the PCs and their adventures. It's true that Traveller can be vast in scope and certainly the official Third Imperium setting encompasses tens of thousands of worlds spread across dozens of sectors of space. Yet, the play of the game remains human-scaled, which is exactly what Traders and Gunboats supports with its information on smaller space vessels.

Of course, as you'd expect, given my preamble, it's the deckplans that still excite me. Here's a sample page featuring a few small (20–50 ton) craft.

Traders and Gunboats includes more than a dozen of these maps, most of which have proven very useful to me over my years of playing Traveller – so useful that I rank it up there with 76 Patrons in terms of how much I've used it at my own table. That's probably the highest praise I can give any RPG product.

Traders and Gunboats includes more than a dozen of these maps, most of which have proven very useful to me over my years of playing Traveller – so useful that I rank it up there with 76 Patrons in terms of how much I've used it at my own table. That's probably the highest praise I can give any RPG product.

August 22, 2023

Polyhedron: Issue #6

Following in the footsteps of its predecessors, issue #6 of Polyhedron (June 1982) features a striking piece of original art for its cover. This time, it depicts a scene from (presumably)

Boot Hill

, as imagined by artist David D. Larson, whose name is otherwise unknown to me. Regardless, it's a terrific illustration and yet another reminder of how much unique artwork graced the pages of Polyhedron.

Following in the footsteps of its predecessors, issue #6 of Polyhedron (June 1982) features a striking piece of original art for its cover. This time, it depicts a scene from (presumably)

Boot Hill

, as imagined by artist David D. Larson, whose name is otherwise unknown to me. Regardless, it's a terrific illustration and yet another reminder of how much unique artwork graced the pages of Polyhedron.

Apropos to my recent post on this topic, the issue opens with a letter from a reader in Georgia, USA: A local religious group is trying to ban DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® from our school and library. Can you help?" The reply – it's unclear whether it's from editor-in-chief Frank Mentzer or editor Mary Kirchoff – is as follows:

Though I can't be certain, I assume the "Duke" mentioned above is Bruce "Duke" Seifried, a friend of Gary Gygax who would join TSR sometime in late '82 or early '83 as the head of its new miniatures division. If so, I'm not certain why concerns about attempts to ban D&D should be directed to his attention, but there is much about the inner workings of TSR that elude me.

Though I can't be certain, I assume the "Duke" mentioned above is Bruce "Duke" Seifried, a friend of Gary Gygax who would join TSR sometime in late '82 or early '83 as the head of its new miniatures division. If so, I'm not certain why concerns about attempts to ban D&D should be directed to his attention, but there is much about the inner workings of TSR that elude me.Frank Mentzer's "Where I'm Coming From" talks about a couple of related matters, starting with "why the various game manufacturers don't get along." Mentzer states that, since publishers are all competing for business, it only makes sense that they wouldn't always see eye to eye. That's why the RPGA doesn't support non-TSR games: the company isn't interested in directing sales to other companies. It's a very honest answer. Mentzer also mentions that TSR continues to expand its library of games, noting that the company has just acquired SPI, making Dragonquest a TSR game and thus eligible for inclusion in the RPGA. Of course, we all know how that turned out ...

The third and final part of the interview with Gary "Jake" Jaquet appears in this issue. I keep saying I ought to write a series of posts about what he has to say in this interview, but I've been distracted lately by other matters and haven't had the time. That said, there are a couple of tidbits worth mentioning here. First, Jaquet explains that he's kept "DRAGON™ magazine's style more conservative" because he views it in the same way a doctor might view a medical journal: "getting information, facts, people's opinions." It's "not a supermarket magazine that has four inch headlines." Second, he states that he prefers Dungeons & Dragons to its AD&D sibling. Here's why:

I suppose, because Jaquet's perspective is similar to mine, I'm naturally inclined to agree with it. Even if you don't share his point of view, I think it's fascinating to see an employee of TSR speaking so frankly about his own assessment of the company's two biggest games. Jaquet comes across in the interview as a plain speaker who isn't all that interested in spouting a party line on any topic and that's very appealing.

I suppose, because Jaquet's perspective is similar to mine, I'm naturally inclined to agree with it. Even if you don't share his point of view, I think it's fascinating to see an employee of TSR speaking so frankly about his own assessment of the company's two biggest games. Jaquet comes across in the interview as a plain speaker who isn't all that interested in spouting a party line on any topic and that's very appealing."Notes for the Dungeon Master" is uncredited, though it seems likely to have been written by Frank Mentzer. This issue, the column focuses on the much-vexed question of "realism" in RPGs. After the ritual invocations of "play the game however you like," the unnamed author suggests that a truly realistic game would be unplayable. In his view, internally consistent and fun rules are more important than fully simulating reality. I find this hard to disagree with this, but it's an old fault line within the hobby, one about which nearly everyone has a strong opinion.

"The Weapons of the Ancients" by James M. Ward presents a collection of new technological weapons for use with Gamma World. Reading these, what's most intriguing is to me is that, with a single exception, none of these weapons has ever appeared anywhere else. As I've said many times before, it's deeply frustrating to me how little support TSR gave Gamma World in terms of supplements and adventures. To see Ward coming up with all these new material for Polyhedron, a niche periodical of the RPGA, rather than for more widely circulated venues, breaks my GW-loving heart.

"Spelling Bee" focuses on illusion and phantasm spells. That the unnamed author, probably Frank Mentzer, spends two pages defining terms, proposing principles, and offering examples demonstrates just how difficult the use of such spells have long been in Dungeons & Dragons (and indeed almost any fantasy RPG). That's not a criticism of the article, which does a fair job of trying to make sense of it all. However, it's true that, in all my decades of playing D&D, few things have continued to cause consternation to myself and players more than illusion spells.

"Dispel Confusion" tackles a few more AD&D rules questions, one of which touches on the aforementioned topic of realism: weak spots in a dragon's hide. It's suggested that the game would be slowed "considerably" by the inclusion of hit location rules, hence their lack of inclusion. "An Ace Against the Odds" by Mike Carr is a solitaire scenario for use with Dawn Patrol. The amount of Dawn Patrol content in Polyhedron really surprises me. Though I was a fan of the game in my youth, I never got the impression it was particularly popular. Perhaps I was mistaken in this assessment. "First Tournament Tips" by Errol Farstad takes a look at the ins and outs of starting up a RPGA-sanctioned tournament at your local game convention. Though brief, it's an interesting article, especially if, like me, you've never dreamed of doing anything like this. Finally, there's another installment of Roger Raupp's "Nor" comic – still no more details about the downed starship from the first installment, alas.

August 19, 2023

H.P. Lovecraft and the Evolution of Genre

Though I'd read some of his earlier, less overtly cosmic stories beforehand, it was the release of Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game in 1981 that ultimately cemented my lifelong affection for H.P. Lovecraft and his works. I doubt this is a unique situation. Indeed, I have long suspected that Call of Cthulhu has probably served as the gateway to Lovecraft for more people since its publication four decades ago than almost anything else. Consequently, on the 133rd anniversary of his birth, I wanted to use Call of Cthulhu as the springboard for some rambling thoughts on the changing meaning of literary genres and the question of the genre in which Lovecraft himself wrote.

Though I'd read some of his earlier, less overtly cosmic stories beforehand, it was the release of Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game in 1981 that ultimately cemented my lifelong affection for H.P. Lovecraft and his works. I doubt this is a unique situation. Indeed, I have long suspected that Call of Cthulhu has probably served as the gateway to Lovecraft for more people since its publication four decades ago than almost anything else. Consequently, on the 133rd anniversary of his birth, I wanted to use Call of Cthulhu as the springboard for some rambling thoughts on the changing meaning of literary genres and the question of the genre in which Lovecraft himself wrote.If you take a look at the subtitle of the 1981 edition of Call of Cthulhu, you'll see that it reads "Fantasy Role-Playing in the Worlds of H.P. Lovecraft" – and so it remained for more than a decade, until the advent of the game's 1992 edition, when the subtitle became "Horror Roleplaying in the Worlds of H.P. Lovecraft." I remember being mildly baffled by this in my youth. I had assumed, based on my initially limited reading of HPL, that Call of Cthulhu would be a horror RPG. In what sense could the game be called fantasy? Bear in mind that, by the time of 1981, the term "fantasy" had already become strongly associated with stories that existed somewhere in that twilight realm located between Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and Howard's tales of Conan the Cimmerian. My bafflement stemmed from this fact.

With age, I've come to understand a couple of additional details that shed some light on this matter. First, in some corners of the hobby, particularly the West Coast but also in the UK, the term "fantasy roleplaying game" – or FRP – was a generic term. In this sense, a fantasy roleplaying game was a category of game, much like a boardgame or video game. Second, and probably relatedly, the term "fantasy" itself could still be used generically, applying very broadly to any fictional work that departs from everyday reality, in one way or another. As I already noted, this usage was not familiar to me in 1981, thanks in no small part to the success of marketers and bookstore managers in dividing and segregating the various strands of fantasy into fantasy proper, science fiction, horror, and so on. I suspect that the fine folks at Chaosium, being older fantasy fans, retained that earlier, broader sense of the term when they subtitled Call of Cthulhu.

But what about Lovecraft himself? How did he view the genre(s) in which he worked? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the matter is complicated. Obviously, Lovecraft lived the entirety of his life before there were any widely accepted distinctions between different types of speculative fiction. They were all still deemed varieties of "fantasy" and Lovecraft would occasionally talk about his work or those of others in his circle as "fantasies." He would, in fact, sometimes call himself a fantaïsiste, an archaic English word borrowed from French for both a dreamer and a creator of fantasies (Lord Dunsany being one of his models in this regard).

At the same time, one of Lovecraft's most celebrated non-fiction writings is his 1927 essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature." In it, he surveyed the development and characteristics of a genre to which he gives various names – the "weirdly horrible tale," the "weird tale," the "literature of cosmic fear," "fear-literature," the "horror-tale," and more. HPL seemed to use the term "weird tale" most frequently to describe his own works, most of which were published, perhaps not coincidentally, in the pages of a magazine bearing the title Weird Tales.

Does the weird tale constitute a genre – or perhaps sub-genre – of its own? Does it have unique characteristics distinct from those of other kinds of speculative fiction? These are good questions without clear answers. As is so often the case, whether one recognizes any answer as dispositive depends on how finely one wishes to slice a great mass of literature. Further, the fineness with which one can categorize literature is itself a product of historical context. It's only with the benefit of hindsight that one possesses sufficient numbers of categories to claim magisterially that, for example, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is a work of science fiction rather than fantasy. At the time the novel was written, such distinctions did not exist or, more importantly, did not matter. Even now, they have no impact whatsoever on one's enjoyment of Verne's tale.

To a great extent, that is also my judgment on the genre of H.P. Lovecraft's works: it doesn't matter. Whether one judges them fantasy, horror, or science fiction by the standards of today makes no difference to my own enjoyment of them. I increasingly feel as if this obsession with categorization, of putting everything into a clearly marked box, is folly – the pastime of pedants and advertising flacks. It's a defect of character to which I am particularly prone, which is why I feel it's important to push back against it. Ultimately, all that should matter is whether one finds a given story worthy – by whatever criteria – and not on the basis the literary genre it supposedly occupies.

All of which is to say: Happy birthday, HPL! Whether you're a writer of fantasy, horror, or science fiction, your works have immeasurably enriched my life and I am glad to have discovered them.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers