James Maliszewski's Blog, page 72

July 7, 2023

The Old Man and the VTT (Part II)

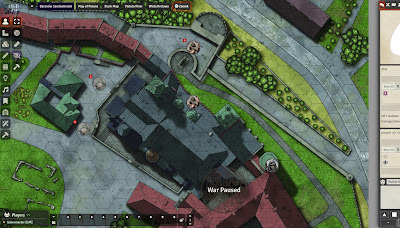

You may recall that, at the end of last year, I expressed some dissatisfaction with the Foundry virtual tabletop that I was using for my weekly Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign. Though extremely powerful in its functionality, it was also unwieldy and poorly documented, leading to a great deal of frustration on my part. Nevertheless, I decided to continue to use it in the hopes that, over time, I'd grow more adept at using it to its full potential. After all, a great deal of effort had obviously gone into the creation and development of both the Foundry and the Twilight: 2000 add-on module and I wanted to give them both a fair shake.

You may recall that, at the end of last year, I expressed some dissatisfaction with the Foundry virtual tabletop that I was using for my weekly Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign. Though extremely powerful in its functionality, it was also unwieldy and poorly documented, leading to a great deal of frustration on my part. Nevertheless, I decided to continue to use it in the hopes that, over time, I'd grow more adept at using it to its full potential. After all, a great deal of effort had obviously gone into the creation and development of both the Foundry and the Twilight: 2000 add-on module and I wanted to give them both a fair shake. A couple of sessions ago, as the characters prepared to infiltrate Baranów Sandomierski Castle, I finally reached the limit of my patience with the VTT. I won't waste time with a summary of all the issues I encountered during that session. I will only say that they were sufficient that I seriously considered abandoning the campaign entirely. Before I took such a rash step, however, I spoke to my players about my frustrations and discovered that they largely felt similarly about the situation. Since everyone was enjoying the campaign, we simply decided to abandon the use of the VTT for future sessions, opting instead for simple sketch maps on a Jamboard rather than anything more elaborate (this is what I've done in my House of Worms campaign for years now).I know that many people, even people as ancient as myself, regularly make use of virtual tabletops with great success and that their enjoyment of games is greatly enhanced by them. I'm sincerely happy for such people. For myself, though, the opposite has largely been the case. Over the years that I've played online, I have never found an elaborate VTT to offer any significant benefit beyond the storage of character sheets and as a dice roller in games that use funky dice (as Twilight: 2000's current edition does). Most of the time, the VTT worked against my enjoyment of play, in large part because of how arcane they were to operate.

I certainly understand the theoretical appeal of a virtual tabletop. As its name suggests, it's an attempt to emulate the look and feel of playing in person while seated around a common table. As I've said repeatedly on this blog over the years, playing in person is the ideal way to play a roleplaying game and, until the last decade or so, I never even considered playing any other way. That's why I'm sympathetic to the intention behind VTTs and why, in my naivete, I have attempted to make use of them in my online games. None, in my experience anyway, have come close to bringing an online game any closer to being an in person game. If anything, what they have done is make it all the more plain that I am not playing a game face-to-face. They've made it all feel like a clunky, analog video game and what's the point in that?

I've often commented that one of the few unalloyed goods that the Internet has given us is the ability to connect with people all over the globe who share our interests. I've made many wonderful friends over the years because of the Internet, most of whom I'd never have met otherwise. I'm deeply grateful for that. Yet, even as Internet technology has improved, it has still not improved enough that I feel as if a virtual tabletop is a good option for playing a RPG with friends. If refereeing the House of Worms campaign over the last eight years has taught me anything – and it's taught me a lot – it's that simple is best. The online experience can never replicate, let alone replace, being there in the flesh, rolling actual dice with your friends, of course, but the fewer layers of mediation between you and your friends, the closer you come to it. That's why I'm giving up on the Foundry for Barrett's Raiders and going as bare bones as possible. In retrospect, that's probably what I should have done from the beginning.

July 5, 2023

Six Months In

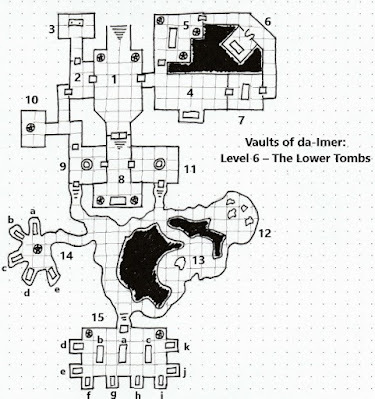

It's now been six months since the start of Dungeon23. Though I tend to be skeptical of these kinds of bandwagon-y Internet "challenges," I nevertheless decided to participate in this one, because I thought it a worthwhile endeavor in its own right – the creation of a twelve-level, 365-room dungeon over the course of a year – and because I thought its pace – one room a day – was sustainable. Sitting here at the beginning of the second half of the year, I still think that. In fact, I'm very glad that I've stuck with this, even if it's occasionally been harder to do than I'd anticipated.

It's now been six months since the start of Dungeon23. Though I tend to be skeptical of these kinds of bandwagon-y Internet "challenges," I nevertheless decided to participate in this one, because I thought it a worthwhile endeavor in its own right – the creation of a twelve-level, 365-room dungeon over the course of a year – and because I thought its pace – one room a day – was sustainable. Sitting here at the beginning of the second half of the year, I still think that. In fact, I'm very glad that I've stuck with this, even if it's occasionally been harder to do than I'd anticipated.As you may recall, I chose to use Dungeon23 as an opportunity to develop the Vaults of da-Imer, a subterranean area beneath the former capital of the Empire of Inba Iro. My hope was that my daily work would eventually provide me with an adventuring locale in which to playtest Secrets of sha-Arthan, as well as give me the opportunity to flesh out parts of its setting. I also felt it inculcated good discipline in me by ensuring that, no matter what, I wrote something every day if I wasn't going to fall behind on the whole project.

That's not quite what happened, alas. At the moment, for example, I am five days behind in my pace, but I have little doubt I'll be able to catch up soon. Part of the problem for me is that I am no cartographer. Drawing maps is something about which I do not feel confident. Likewise, I opted for an approach that broke down each month's level into two to four "complexes," each consisting of somewhere between 8 to 15 rooms. While a great idea from the perspective of variety, not to mention providing multiple pathways to explore the Vaults, it increased my workload significantly, hence my occasional backlogs of work.

On the other hand, I've completed six levels and 181 individual rooms so far. That's not nothing. I doubt I'd have made it this deep into the Vaults of da-Imer if I didn't have the artificial frame of Dungeon23. I remain reasonably confident that, at the end of this year, I'll complete all twelve levels and 365 rooms. The end result won't be pretty, but it'll be a substantial amount of raw material from which to build something more polished. Even now, I often find myself going back and adding to or editing previous entries, as better, more complete ideas come to me. Frustrations aside, this has been a worthy project. I hope others have found it similarly useful to them.

Retrospective: SoloQuest

For obvious reasons, the last few years have seen a resurgence of interest in solo adventures for use with roleplaying games. Adventures of this sort have a long pedigree, going back at least as far as 1976's Buffalo Castle for Tunnels & Trolls. Other attempts to present a referee-less scenario for use by a single player followed, employing a number of different approaches, some of them quite exotic, like invisible ink and a "magic viewer."

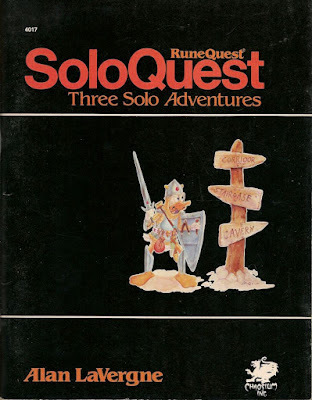

For obvious reasons, the last few years have seen a resurgence of interest in solo adventures for use with roleplaying games. Adventures of this sort have a long pedigree, going back at least as far as 1976's Buffalo Castle for Tunnels & Trolls. Other attempts to present a referee-less scenario for use by a single player followed, employing a number of different approaches, some of them quite exotic, like invisible ink and a "magic viewer." The most successful ones, however, followed in the footsteps of Buffalo Castle (or perhaps Sugarcane Island?) by presenting a series numbered paragraphs read according to the narrative choices of the reader. This is the format adopted by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone's phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy series of gamebooks, for instance. It's also the format Chaosium employed for its own forays into the field of solo gaming, starting with SoloQuest in 1982.

Written by Allen LaVergne, who was a player in Steve Perrin's Pavis campaign, SoloQuest presents three adventures for RuneQuest suitable for use by a single player without the need for a referee. The scenarios are not specifically connected to Glorantha and the book's introduction suggests they're completely usable by a character from any RuneQuest setting. The first of these scenarios is "DreamQuest," the most straightforward of the three. Its premise is that the character's favored god appears to him in a dream and asks him "to fulfill a mission, a symbolic reenactment of [the] god's conquests. Unlike most dreams, in this one there are real risks to run and real rewards to gain."

What follows is a series of combat encounters, in which the character's dream self must overcome ever more powerful opponents. There are twenty such encounters, ranging from Sardanik Scrolleater, an armored baboon with a spear, to Errol, a swashbuckling manticore, to Huey and Looie, a pair of ducks, and many more, culminating in the final battle – against the character's doppelganger. Almost all of these encounters are idiosyncratic in one way or another, reflecting the opponent's personality and nature. They typically include an outline of the opponent's tactics in combat and some even note the conditions under which combat might be avoided. "DreamQuest" isn't really an adventure so much as an excuse to run some battles using the RQ rules. How much one enjoys that will likely determine how much one enjoys the scenario as a whole.

The second adventure is "Phony Stones," which concerns the sale of "bogus statues of Issaries" to naive individuals hoping that, by buying them, they might be initiated into the god's cult. The temple of Issaries is thus offering a sizable reward for anyone who can find and capture the perpetrator of this deception. The setting of the adventure is a small town of about 50 residences, which the character will need to investigate to unravel this mystery. Unfortunately, the limitations of the solitaire format hamper one's ability to do so as effectively one might during refereed play. For example, interactions with NPCs are largely pre-scripted, meaning you can only perform whatever actions the numbered paragraphs offer you, which, in many cases, are very few. The end result is fairly unsatisfying, even compared to your average Fighting Fantasy book.

The third adventure is "Maguffin Hunt." The Duke of Jawain hires to the character to enter the hideout of a band of dwarves who have stolen his maguffin. Despite the fact that the duke "will provide a very detailed description of the maguffin," nowhere does the text actually do so. I am left to presume that this ambiguity is intentional, allowing it to be whatever the player imagines it to be. If so, the scenario never makes this clear, which is all the more vexing since, at its conclusion, the character discovers the dwarves no longer even have it. They've sold it to a third party and there's not a hint as to the identity of the buyer. Even so, "Maguffin Hunt" is a little more enjoyable than "Phony Stones," since it's largely a series of combat encounters, which the solo format handles reasonably well, rather than the frustratingly limited investigations of the previous adventure.

Ultimately, that's the biggest problem with SoloQuest: its scenarios rarely rise above the level of scripted combats, which strikes me as almost criminal when dealing with a game like RuneQuest, whose strength has always been its richly detailed settings and interesting characters. Of course, how one would succeed in presenting such things within the context of a solitaire adventure is a vexing question even in 2023. The computer RPGs of the present are vastly more sophisticated and complex than something like SoloQuest and yet even they often struggle with presenting an imaginary world and its inhabitants with the kind of depth to be found in even a mediocre tabletop session with other human beings. Consequently, I can't judge SoloQuest too harshly for its shortcomings, though I nevertheless wish it were better than it is.

July 4, 2023

More Fear and Death

Last month, I shared some illustrations from the AD&D Monster Manual to draw attention to how many of them depicted scenes in which a monster menaced, injured, or even killed an adventurer. There were so many illustrations of this sort that I couldn't include them all – and that's a shame. With that in mind, here are a few more of my favorites.

I wanted to start with this page of the MM, since three out of the four monster illustrations on it show off their dangers. I've always been particularly fond of the gas spore piece, though the giant gar is far more terrifying.

Speaking of terrifying fish, how about this giant pike? Did Gary Gygax like to fish? I can't help but wonder if his experiences with carnivorous fish might have influenced his decision to include them in the Monster Manual.

Speaking of terrifying fish, how about this giant pike? Did Gary Gygax like to fish? I can't help but wonder if his experiences with carnivorous fish might have influenced his decision to include them in the Monster Manual.

Treants are not monsters that, in my experience, get much respect. Part of it, I imagine, is that they're Chaotic Good in alignment and few players ever worry about running afoul of them. Still, as this illustration shows, they're not to be trifled with (having upwards of 12 Hit Dice will do that).

Treants are not monsters that, in my experience, get much respect. Part of it, I imagine, is that they're Chaotic Good in alignment and few players ever worry about running afoul of them. Still, as this illustration shows, they're not to be trifled with (having upwards of 12 Hit Dice will do that).

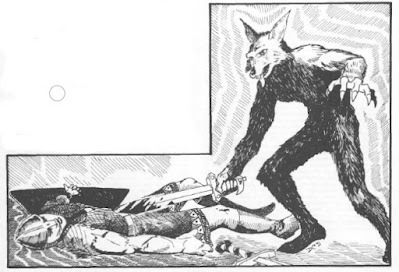

Here's a jackalwere (presumably) killing an adventurer. This piece is one of the most immediately gruesome in the whole book.

Here's a jackalwere (presumably) killing an adventurer. This piece is one of the most immediately gruesome in the whole book.

Here's another favorite. I absolutely love Tom Wham's take on the illithid using his mind blast to attack a trio of rather hapless adventurers. I also dig the funky, abstract art he's got on the wall of his lair, with what appears to be an incense brazier alight beneath it. Who knew mind flayers were so chic?

Here's another favorite. I absolutely love Tom Wham's take on the illithid using his mind blast to attack a trio of rather hapless adventurers. I also dig the funky, abstract art he's got on the wall of his lair, with what appears to be an incense brazier alight beneath it. Who knew mind flayers were so chic?

I'll conclude this post with another piece that's long fascinated me: Dave Trampier's depiction of a bugbear giving a fighter a whack in the face with a mace or some similar bludgeoning weapon. That's going to leave a mark!

I'll conclude this post with another piece that's long fascinated me: Dave Trampier's depiction of a bugbear giving a fighter a whack in the face with a mace or some similar bludgeoning weapon. That's going to leave a mark!

July 3, 2023

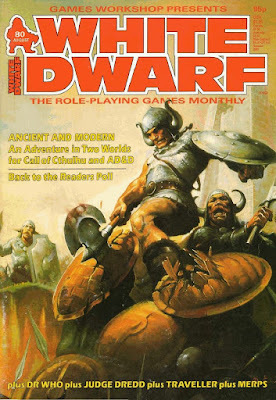

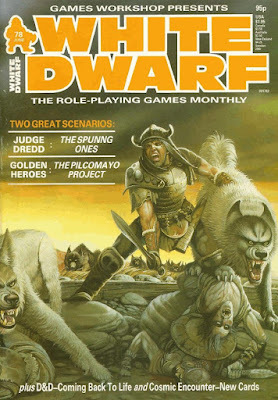

White Dwarf: Issue #80

And so, with issue #80 (August 1986), we come to the end of my retrospective on Games Workshop's White Dwarf. Even so, I'll likely have some concluding thoughts on the entire series next week, since I feel, after so many months of posts on the magazine, there's still a lot to be said about it. This issue features a strong cover illustration that recalls the work of Frank Frazetta – no surprise there, since the artist, Ken Kelly, was the nephew of Frazetta's wife and had the chance to study Frank's works and technique up close and personal.

And so, with issue #80 (August 1986), we come to the end of my retrospective on Games Workshop's White Dwarf. Even so, I'll likely have some concluding thoughts on the entire series next week, since I feel, after so many months of posts on the magazine, there's still a lot to be said about it. This issue features a strong cover illustration that recalls the work of Frank Frazetta – no surprise there, since the artist, Ken Kelly, was the nephew of Frazetta's wife and had the chance to study Frank's works and technique up close and personal.Paul Cockburn's editorial focuses on a new Reader's Poll included at the end of the issue. The poll is quite lengthy, lengthier than many previous ones, in part, I suspect, because Games Workshop was trying to understand its current readership as it charted its course into the future. After nearly ten calendar years of publication, White Dwarf had changed a great deal, as had Games Workshop itself. It, therefore, makes sense that the company would want to take stock of its readers in order to better serve them.

"Open Box" kicks off with a very positive review of Games Workshop's printing of the third edition of Call of Cthulhu. Normally, I'd have a critical word or two about WD's habit of advertisements dressed up as a reviews, but, in this case, I'll make an exception. The GW hardcover printing of CoC's third edition is indeed an excellent product, one of the best versions of the game ever, in fact. I only wish I still had my copy. Also reviewed are two adventures for FASA's Doctor Who RPG, The Hartlewick Horror and The Legions of Death. The former receives greater praise, primarily because it's less complex and more suitable to referees of all levels of experience. Palladium's The Mechanoids gets a negative review, with the reviewer (Marcus L. Rowland again) suggesting that it'd work better as a war game than as an RPG. Destiny of Kings for AD&D is favored over Swords of the Daimyo (also for AD&D). Realms of Magic for Marvel Super Heroes is treated positively for the most part, though the reviewer (Peter Tamlyn) expresses some dissatisfaction with the added complexity this supplement introduces. He also criticizes the excessive use of the trademark symbol throughout the text, necessitated, no doubt, by Marvel's lawyers. Finally, there's Avalon Hill boardgame, Dark Emperor, by Greg Costikyan, which merits only middling praise.

Nigel Cole's "Combat in Doctor Who" attempts to correct some errors and oversights in FASA's RPG. Meanwhile, "Something Special" by Hugh Tynan introduces ten new special abilities for use by characters in Judge Dredd the Role-Playing Game. "Clouding the Issue" by Chris Barlow takes a look at the various detection spells available in AD&D with an eye toward sorting out the inconsistencies. "Crime Inc." by Graeme Davis presents a system for creating organized crime groups for use with any 20th century RPG. The system takes into account a group's size to give the referee an idea of how many members of various ranks it possesses, along with the extent of its reach into illicit activities. It's nothing fancy, but it looks genuinely useful in fleshing out enemy groups for a wide variety of RPGs.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" returns to form by providing capsule reviews of a plethora of books, most of which I've never read, the exception being The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers. It's funny: I've rarely been a fan of Langford's columns, but, despite that, I think I'll miss reading them nonetheless. I suppose that's mostly a function of the fact that they've been a fixture of the magazine since issue #39, which grants them an almost-venerable status. On the other hand, I've always liked both "Thrud the Barbarian" and "Gobbledigook" (the latter reduced to half a page in this issue), so it makes sense that I might feel a pang of regret in saying goodbye to them.

"The Reliant" by Thomas M. Price presents an escape craft, complete with deck plans, "for SF role-playing games," though the titular spaceship is presented using terminology and concepts clearly derived from Traveller. "Roleplaying for Everyone" by Peter Tamlyn is a thoughtful essay on the development and expansion of the concept of roleplaying. Tamlyn looks at the evolution of RPG design and how it has facilitated (or impeded) the adoption of the hobby by a large segment of the public. He also examines the growth of solo gamebooks, like Fighting Fantasy, and ponders what impact they, along with the then-new How to Host a Murder games might have. It's a solid piece that's mostly interesting from a historical perspective, since it was written nearly forty years ago, but I found it a worthwhile read nonetheless.

The best thing in this issue, in my opinion, is Graham Staplehurst's adventure "Ancient & Modern." Described as "a scenario for schizophrenic roleplayers," it draws on work of author Brian Lumley, specifically his tales of the primal continent of Theem'hdra, a kind of Conan-meets-the-Cthulhu-Mythos sort of sword-and-sorcery setting. "Ancient & Modern" takes place in two times, the ancient past and the present day, with players portraying two sets of characters using two different game systems, most likely AD&D for the former and Call of Cthulhu for the latter, though the scenario is written to accommodate other possibilities. The outcome of events in Theem'hdra affect those in the 20th century, so there is a direct connection between the two halves of the scenario. I've long wanted to referee a scenario of this sort before, so I was very intrigued by "Ancient & Modern."

Closing out the issue is another installment of "'Eavy Metal," complete with many color photographs of beautifully painted miniature figures. As I'm certain I've said many times before, I genuinely appreciate articles like this, because I've never been very good at painting minis. Seeing what others more skilled than I have done with them is a treat and an education about a side of the hobby with which I have very little experience.

There you have, the final issue of White Dwarf that I'll be reading as part of a series of posts. I do wish that this had been a more remarkable issue than it was, so that it might have weakened my resolve to move on to something else. Alas, it was not and so I now must bid farewell to White Dwarf. For the most part, I enjoyed this trip down memory lane and am glad that I took the time to do it. After a final post next week, in which I attempt to sum up my various thoughts about WD and its place in the larger hobby, I'll move on to another topic. Polyhedron perhaps?

June 28, 2023

The Nerdish Accent

Anyone who knows me also knows that I'm a stickler for proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation. This is an obsession of long standing, going all the way back to my childhood. As to its origin, I cannot truly say, except that, growing up, I used to spend a lot of time reading the copy of The Random House Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language that we kept in our living room. That tome, with its gilt title and thumb index, certainly played a role in my fascination with alphabets and writing systems, so I wouldn't be at all surprised if it likewise influenced my enduring love of language. Of course, a much simpler explanation is simply that I read a lot as a young person, like most nerds of my generation (or, come to think of it, the generations before mine). The books I read, especially the fiction, often included unusual, exotic, and highly specific words of the sort that Gary Gygax employed in his own writings.

Anyone who knows me also knows that I'm a stickler for proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation. This is an obsession of long standing, going all the way back to my childhood. As to its origin, I cannot truly say, except that, growing up, I used to spend a lot of time reading the copy of The Random House Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language that we kept in our living room. That tome, with its gilt title and thumb index, certainly played a role in my fascination with alphabets and writing systems, so I wouldn't be at all surprised if it likewise influenced my enduring love of language. Of course, a much simpler explanation is simply that I read a lot as a young person, like most nerds of my generation (or, come to think of it, the generations before mine). The books I read, especially the fiction, often included unusual, exotic, and highly specific words of the sort that Gary Gygax employed in his own writings. While my reading vocabulary was naturally enriched by the grandiloquent authors whom I favored, that didn't always translate directly into speech. It's one thing to know what a word means, but it's another thing entirely to know how it's pronounced. I can distinctly recall my youthful mispronunciation of the word "dilettante," for example, and it was far from the only example of where my literary precociousness had not given me a concomitant verbal acuity. If my own experiences are any guide, this was a fairly common occurrence. The "nerdish accent" is a highly individualized thing, but its one certain characteristic is that it reveals a person whose vocabulary, acquired through wide reading, is quite large but whose ability to pronounce much of that vocabulary is quite limited, owing to his never having heard the words spoken by another human being.

My friends and I would often argue with one another about the way that some obscure word used in Dungeons & Dragons was pronounced, like dais or grimoire or guisarme (not to mention made-up words of the sort that appeared in the Monster Manual). This would inevitably lead us to a dictionary to determine the truth of the matter, assuming that the word wasn't too obscure to be found there. What's interesting is that, even to this day, I still regularly encounter nerds of my vintage who mispronounce words in this fashion. Though my inner pedant bristles at this, I simultaneously find it a charming reminder of my own younger days, when I, too, did not know the proper way to pronounce many of the words I read.

The nerdish accent seems less common among those much younger than myself. Instead, what I notice is a rather different phenomenon: the inability to properly spell a word that one has only ever heard spoken by others. On those occasions when I look at forums, for instance, I regularly see the most bizarre misspellings, like "persay" for "per se," which suggests to me that audio and video are now much more important in the transmission of knowledge than they were in my day. A nerd of the past would have been much more likely to mispronounce that Latin phrase (as "per see" perhaps) than to misspell it. Nowadays, it seems like it's the spelling that's the source of error, not the pronunciation.

I suppose this shift – if indeed it is a shift – points to the influence of the Internet. Personal computers barely existed in my own childhood and the Internet wouldn't become widely accessible, let alone a driver of popular culture, for decades after my own fascination with language began. Books were the only means I had to learn about most topics of interest to me. That's less the case now and I suspect any decline in the prevalence of the nerdish accent might reflect the weakening of the primacy of the book, though it's a complex issue and likely has many causes.

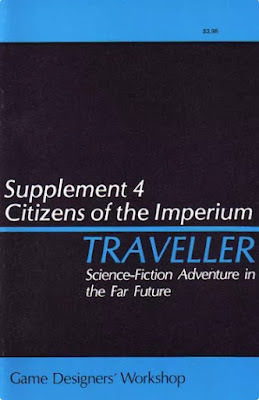

Retrospective: Citizens of the Imperium

During the decade between 1977 and 1987, Game Designers' Workshop released thirteen supplements for use with what is now known as "classic" Traveller. As you might expect, these supplements are a mixed bag, ranging from the essential to the merely useful to the forgettable. I own them all, of course, because I've been a huge fan of the game since I first encountered it a little more than forty years ago. Even so, there are only a handful of these supplements I always use when playing and high on that list is Citizens of the Imperium.

During the decade between 1977 and 1987, Game Designers' Workshop released thirteen supplements for use with what is now known as "classic" Traveller. As you might expect, these supplements are a mixed bag, ranging from the essential to the merely useful to the forgettable. I own them all, of course, because I've been a huge fan of the game since I first encountered it a little more than forty years ago. Even so, there are only a handful of these supplements I always use when playing and high on that list is Citizens of the Imperium.First published in 1979, Citizens of the Imperium is 44-page digest-sized book completely devoid of any artwork, either on its cover or in its interiors. That's par for the course for most classic Traveller supplements – and quite a few adventures, too, come to think of it – unless you consider maps, deckplans, or mathematical formulae illustrations. It's frankly impossible to imagine a RPG supplement being released nowadays without even a single illustration, but, at the time, I can't recall anyone commenting on it, let alone being put out by it. Yet more evidence that the past really is a foreign country.

The book consists of two large sections, as well as two smaller ones. The first large section is the most important, introducing as it does twelve new starting careers for player characters, most of which are civilian in nature. This is significant, because the original Traveller rules only provided for three military careers (Army, Navy, Marines) and one paramilitary career (Scouts), with only the Merchants and nebulously-defined-but-probably-criminal "Other" career as non-military alternatives. Citizens of the Imperium widens the field considerably, offering barbarians, belters, bureaucrats, diplomats, doctors, flyers, hunters, nobles, pirates, rogues, sailors, and scientists as possibilities, though some are more clearly attractive than others (I have never, in all my years of playing Traveller, seen anyone roll up a bureaucrat, but I'm nevertheless glad the option exists).

The second large section is more or less an adjunct to the previously published 1001 Characters, in that it presents 40 pre-generated examples of each career type, to be used either as player or non-player characters. Difficult as it is to imagine from the vantage point of a world with ubiquitous personal computers and similar devices, this section would have been a genuine godsend to the harried referee. I know I regularly made use of it in creating NPCs for my campaigns and I suspect I was not alone in doing so. Much more so than Dungeons & Dragons, Traveller regularly included "time saver" material like this in its books, supplements, and adventures, which made sense, since what we now call "sandbox" play with the default campaign playstyle.

The two smaller sections of Citizens of the Imperium are, in different ways, worthy of note. The first provides rules for low-tech missile weapons – bows and crossbows – for use by characters in the game. I suspect the presence of both barbarians ("rugged individuals from primitive planets") and hunters ("individuals who track and hunt animals") suggested their inclusion (though Traveller was already notable among SF RPGs for including a wide range of low-tech melee weapons). The second small section presents eight heroes and villains "drawn from the pages of science-fiction" in Traveller terms. This section is important for anyone interested in assembling an "Appendix T" for the game, which is to say, a list of its literary antecedents. We get the game's interpretation of Harry Harrison's Slippery Jim di Griz, Keith Laumer's Retief, and James White's Senior Physician Conway, alongside Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, and several others. It's one of my favorite sections of the book, if only because it's a reminder of what inspired Marc Miller and the crew at GDW when making the game.

My complaints about Citizens of the Imperium are few and curmudgeonly. The introduction of new careers paved the way for the introduction of new skills, a baleful trend inaugurated by Mercenary and continued by many more books, supplements, and adventures. I say "baleful," because one of the glories of classic Traveller in my opinion is its relative simplicity, including a relatively spare skill list. The introduction of more – and more specific – skills undermined that simplicity to the game's detriment. Still, it's easy enough to ignore most of the new skills and focus instead on the careers, most of which increased the range of options available to players without adding any mechanical complexity to the game.

June 26, 2023

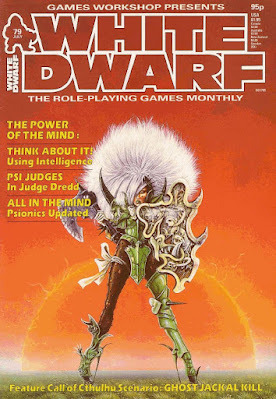

White Dwarf: Issue #79

With issue #79 of White Dwarf (July 1986), I reach the penultimate issue I'll cover in this series. Though I'm glad to have done it – and I hope it's been profitable for those of you reading along – I can't deny that my enthusiasm has been waning for some time now. Sadly, this issue did little to make me regret my decision to end the series with #80, though there are a couple of bright spots – like John Blanche's cover illustration ("Amazonia Gothique"), which I like for reasons I can't fully articulate.

With issue #79 of White Dwarf (July 1986), I reach the penultimate issue I'll cover in this series. Though I'm glad to have done it – and I hope it's been profitable for those of you reading along – I can't deny that my enthusiasm has been waning for some time now. Sadly, this issue did little to make me regret my decision to end the series with #80, though there are a couple of bright spots – like John Blanche's cover illustration ("Amazonia Gothique"), which I like for reasons I can't fully articulate.This issue marks the first one featuring Paul Cockburn as editor. His inaugural editorial mentions that there will be still more changes in store for the magazine, though these will "come in bit by bit." Cockburn also notes that Citadel Miniatures would, from this point on, include "a small warning, intended to prevent figures being sold to that part of the public who might actually be harmed by lead content." He elaborates that there had recently been a Citadel ad in a magazine "aimed at a very young audience," which necessitated this warning. Maybe I'm just old and contrarian, but I felt a slight pang of sadness upon reading this. By 1986, the Old Days (and Old Ways) were already fading ...

"Open Box" takes a look at two related Palladium products, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Other Strangeness and its post-apocalyptic supplement, After the Bomb. Both products are positively reviewed, but the reviewer, Marcus L. Rowland, expresses a preference for the "present day setting of the original game," which he feels offers "more opportunities for plot development and diversity." Also reviewed is Secret Wars II for Marvel Super Heroes, which is judged "an awful lot better than Secret Wars I." Never having seen the original, it's not clear to me whether this is faint praise or not. Two Chaosium releases, Black Sword (for Stormbringer) and Terror from the Stars (for Call of Cthulhu) get positive reviews, as does West End's Ghostbusters. Acute Paranoia, a supplement for (naturally) Paranoia earns a more middling appraisal, largely due to its "disappointing" mini-scenarios.

"Where and Back Again" by Graham Staplehurst is one of the aforementioned bright spots of this issue. Dedicated to "Starting a Middle-earth Campaign," the article lays out all the decisions a referee looking to run a RPG campaign set in Tolkien's world must make. Staplehurst covers subjects like "style" (i.e. campaign frame), rules, and even source material. He also raises the question of how closely one might wish to hew to Middle-earth as described by the good professor and the consequences for choosing to deviate from that particular vision. It's a solid, thoughtful article on a topic that has long interested – and vexed – me.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" has only rarely been something I've enjoyed and this issue's installment does little to change my mind. More enjoyable (to me anyway) is his second contribution to the issue, an odd little article entitled "Play It Again, Frodo." Ostensibly, Langford's assignment is to demonstrate "how closely role-playing and literature are entwined" in order to help readers convince their "serious" friends that gaming isn't a silly hobby. He attempts to do this through a series of vignettes based around famous books or movies – Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Conan, The Lord of the Rings, etc. – where he postulates that events go other (and humorously) than how they do in the originals. The idea here is that roleplaying allows to do things "your way" rather than being bound by the dictates of an omnipotent author.

"20-20 Vision" by Alex Stewart reviews science fiction and fantasy movies. The bulk of this issue's column is devoted to the film, Highlander, in which "a medieval Scottish warrior with a French accent" is befriended by "Sean Connery's Glaswegian conquistador." Stewart calls the movie "a stylish, raucous and utterly preposterous D&D scenario transplanted bodily into contemporary New York." That's probably the most succinct (and amusing) way I've heard Highlander described and it does a good job, I think, of capturing the essence of its cheesy glory.

"All in the Mind" by Steven Palmer offers an alternate psionics system for use for AD&D. Palmer's system interests me for its relative simplicity – the article is only four pages long, as well as for its more flavorful elements. For example, there's a discussion of the heritability of psionic powers, as well as the inherent connection between twins. Neither of these elements plays a major role in his system, but the fact that they're mentioned at all is in stark contrast to the dreary, tedious treatment of psionics in the Players Handbook.

"Ghost Jackal Kill" by Graeme Davis is a Call of Cthulhu scenario that's presented as a prequel to The Statue of the Sorcerer, a Games Workshop CoC adventure. The scenario is set in San Francisco and involves not only the Hounds of Tindalos, one my favorite type of Mythos entities. It also features real-world historical figures, specifically the actress Theda Bara and writer Dashiell Hammett. Normally, I tend to be leery of the inclusion of such people in RPG adventures, but, in this case, I think it works, particularly Hammett, who did actually work as a detective for the Pinkertons and drew on those experiences for his fiction. In any case, it's a good, short scenario and another of the issue's stand-outs in my opinion.

"Think About It" by Phil Masters examines the purpose and use of the Intelligence score (or its equivalent) in roleplaying games. Because it's an overview of a large topic, it's necessarily brief in its examination, but it does a good job, I think, of presenting different options and approaches to handling Intelligence in RPGs. "'Eavy Metal" provides tips on converting miniature figures, along with some nice color photographs.

"Psi-Judges" by Carl Sargent – a name that would feature prominently on the covers of many RPG products throughout the late '80s and into the 1990s – is an expansion of Judge Dredd: The Roleplaying Game focused on, of course, psi-judges. Interestingly, it's equal parts a rules expansion and a roleplaying expansion. There's information on how to play a psi-judge in the game, alongside discussions of game balance and other matters. "Gobbledigook" and "Thrud the Barbarian" are still here, but I can't deny that I miss the presence of "The Travellers." The comic's absence really hits home to me just how much White Dwarf has changed from the days when I read (and enjoyed) it regularly.

One more week!

June 20, 2023

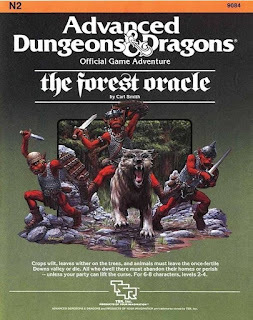

Retrospective: The Forest Oracle

According to the scheme I laid down long ago in Ages of D&D, the year 1984 is the start of the game's Silver Age. The hallmarks of this age are a concern for "dramatic coherence" and "believable" worlds, as well as an esthetic of "fantastic realism." Despite this, Carl Smith's AD&D module, The Forest Oracle, released during the first year of this new era, possesses none of these hallmarks, being instead, by turns, mundane, nonsensical, and – worst of all – dull.

According to the scheme I laid down long ago in Ages of D&D, the year 1984 is the start of the game's Silver Age. The hallmarks of this age are a concern for "dramatic coherence" and "believable" worlds, as well as an esthetic of "fantastic realism." Despite this, Carl Smith's AD&D module, The Forest Oracle, released during the first year of this new era, possesses none of these hallmarks, being instead, by turns, mundane, nonsensical, and – worst of all – dull. On the face of it, this is precisely the kind of module I should like. I'm a professed admirer of low-level adventures, particularly those featuring rural communities beset by the forces of Evil. It's not for nothing, after all, that I judge Gary Gygax's The Village of Hommlet not merely a great module, but my favorite of the game's Golden Age. To my way of thinking, there's something particularly appealing, indeed almost mythical, about the set-up of so many of these low-level adventures that I can't help but look on them beneficently.

The premise of The Forest Oracle is that the Downs, "a hidden vale farmers claimed from the wilderness long ago" lies under a curse that causes fruit to rot, plants to die, and animals to flee. When the characters arrive in the Downs, they meet a kindly old wizard, Delon, who tells them that he believes a "gypsy witch" pronounced the curse after the people here refused to aid her. He then asks the characters to travel into the Greate Olde Woode – no, I am not making this up – to visit the druids who dwell there. Perhaps their powers will be able to lift the curse. (Delon is unable to do this himself, because he is old and feeble.)

What follows is a series of linear wilderness encounters and fetch quests, as the PCs are shuttled from place to place to the accompaniment of badly written boxed text. I give the module points for even having wilderness encounters, since that's not common in low-level scenarios. I'm also willing to cut it some slack regarding its blandly atrocious naming practices (Greate Olde Woode, the Downs, the Wild River, the New Wilderness Road, Quiet Lake, etc.), because it's explicitly intended to be easy to integrate "into any existing campaign," since it's "an independent adventure, and not part of any series." Presumably, this is meant to make it easy for the Dungeon Master to insert in his own setting, replacing the insipid names with more appropriate (and flavorful) ones.

Unfortunately, The Forest Oracle is just so straightforward and unimaginative that, even grading on a curve, it's still an almost complete failure. I say "almost," because there are glimmers of clever ideas here and there, like the flesh golem used as a guard by an ogre or the nymph who needs help in freeing her lover from an enchantment, but they're often handled in the most banal (and occasionally nonsensical) ways. It's almost as if the writer went out of his way to choose the least interesting versions of every idea he came up with. A perfect example of this is the hackneyed "gypsy curse" aspect of the adventure. I assumed that the story Delon tells about this is untrue or at least misinformed in some way, since it'd open up other possibilities for the true cause of the blight affecting the Downs. Nope! Madame Riva is responsible for the curse, though she regrets it now and aids the characters in removing it – but only if they do a favor for her first ...

It's all so tiresome. Back and forth, bouncing around from quest giver to quest giver, funneled from one linear locale to another, battling fairly typical low-level enemies – orcs, goblins, giant rats, and so on. Now, to be clear, I don't dislike such enemies; what I object to is their being used in trite, unimaginative ways, which is exactly what we get here. Again and again and again. The cumulative effect is enough to overcome my natural tendency to want to "fix" even a bad adventure module, to find some way to use it as the "raw material" from which to build something more to my taste.

Compared to many, I'm generally quite forgiving of this sort of thing. I don't enjoy trashing a game or a module. I derive little pleasure in pointing out the missteps of a designer or writer, perhaps because I know only too well how easy it is for something that sounds great in one's mind to go terribly wrong in the process of committing it to paper. I'm not sure that's what happened to The Forest Oracle, but I simply don't care. Looking around online, I discovered that I'm not the only person who feels this way about the module. Indeed, I discovered, much to my surprise, that The Forest Oracle is widely considered among the worst Dungeons & Dragons adventures TSR ever published. I'm not sure I'd go that far – Castle Greyhawk is right there, after all – but there can be little argument that it's very, very bad.

White Dwarf: Issue #78

I've got to be honest: reading White Dwarf for these posts is not as much fun as it used to be. Partly, I think I'm simply tired of the magazine, which I've been reviewing for almost two years now. At the same time, I'm finding the individual issues are much more miss than hit, in no small part due to the shift in content toward games that don't interest me very much. That's not necessarily a comment on White Dwarf itself. However, the end is nigh for this series. I'll try to tough it out till issue #80, so I can end it on a nice round number. Any more than that is beyond my patience.

I've got to be honest: reading White Dwarf for these posts is not as much fun as it used to be. Partly, I think I'm simply tired of the magazine, which I've been reviewing for almost two years now. At the same time, I'm finding the individual issues are much more miss than hit, in no small part due to the shift in content toward games that don't interest me very much. That's not necessarily a comment on White Dwarf itself. However, the end is nigh for this series. I'll try to tough it out till issue #80, so I can end it on a nice round number. Any more than that is beyond my patience.Issue #78 (April 1986) features a cover by Chris Achilleos and a new editor, Paul Cockburn. Prior to coming to White Dwarf, Cockburn was an editor and writer at TSR UK's Imagine, which ceased publication in October 1985, with its thirtieth issue. In his editorial, Ian Livingstone, states that "it looks like everything is changing around here except the name" and he's not mistaken. The whole look of WD is different with this issue – the graphic design is more "professional" and there's a lot more color, for instance. Whether that's good or bad is a matter of taste, I suppose. I can only say that, for me, these "improvements" are a vivid signal that the times, they are a-changin' and I hate change.

With this issue, "Open Box" abandons numerical ratings for its reviews, which I applaud. As commenters have repeatedly pointed out to me, those ratings were not made by the reviewers themselves but by someone on the magazine's editorial team, hence their frequent inconsistencies with the actual text of the reviews. The first product examined is Night's Dark Terror, which the reviewer liked as much as I. Cthulhu by Gaslight is also reviewed positively, though somewhat less enthusiastically. The Nobles Book for Pendragon receives an even more muted thumbs up, while Dragons of Glory is recommended only for "the Dragonlance fanatic," which, I think, is quite fair.

Paul Mason's "Cosmic Encounter" is not, strictly speaking, a review of the classic science fiction boardgame. Instead, it's an overview of the game's rules and play, no doubt with an eye toward enticing readers to purchase Games Workshop's new edition of the game. Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is, oddly, more readable now than in previous issues. Whether that's due to a better layout or the fact that Langford – in this issue anyway – reviews fewer books, I can't rightly say. It's a pity that, with one exception, none of his reviews stuck with me. The one that did, for Gary Gygax's Artifact of Evil, which Langford criticizes for its "brutalities visited upon the English language" and for being little more than "an AD&D campaign write-up." I wish I could disagree.

"Solar Power" by Gary Holland is an occasionally amusing bit of original fiction about Norbert Parkinson, a man whose maladaptive development leads to a psychosis in which "he lives in a world occupied by elves, goblins, dragons, evil wizards and diverse other fantasy figures ..." It's fun enough for what it is, I suppose. Meanwhile, Graeme Drysdale's "Ashes to Ashes" is supposed to be "a closer look at resurrection in AD&D." In fact, it's a fairly cursory examination of all the magical spells by which a character can be returned to life in AD&D (reincarnation, raise dead, and resurrection) along with some comments and advice about their advantages and drawbacks. Again, fine for what it is, but nothing special.

Peter Tamlyn's "The Pilcomayo Project" is an adventure for Golden Heroes. The scenario is long – 7 pages – and takes place in Bolivia, where a Neo-Nazi supervillain and his robot stormtroopers are attempting to locate the legendary city of El Dorado. It's four-color nonsense, of course, but probably enjoyable in play. I find it notable, though, that, unlike previous superhero scenarios in White Dwarf, this one is not dual statted for Champions, only Games Workshop's own Golden Heroes – a sign of the times, no doubt!

"The Spunng Ones!" by Marcus Rowland is an adventure for Judge Dredd the Role-Playing Game. This is another long one (8 pages) but it's absurd in a way that only a Judge Dredd story can be. A gang of criminals have given an experimental food additive called "Spunng" to a group of "fatties." Spunng converts their fat deposits into rubbery flesh that is also bullet proof. The fatties the engage in a crime spree the player Judges must stop. As I said, absurd, but that's Judge Dredd for you. "'Eavy Metal" takes a look at Judge Dredd miniatures and includes photos of a Sector 306 diorama built for Games Day '85. As always, it's a pleasure to see the amazing work others put into their miniatures.

This issue includes a full-page "Gobbledigook" comic, along with a re-telling of The Lord of the Rings had "Thrud the Barbarian" been involved. Hint: it doesn't go well for the Dark Lord. Sadly, the issue also marks the end of "The Travellers" comic, which had long been a favorite of mine. If I didn't already have other reasons for wanting to give up on this series, the departure of "The Travellers" might be sufficient.

Two more to go, two more to go. I just need to keep telling myself that ...

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers