James Maliszewski's Blog, page 74

May 30, 2023

Hubble, Bubble, Toil & Death

Here's an advertisement for the Warhammer scenario pack, McDeath, described as follows:

The evil, sadistic and thoroughly unpleasant McDeath has murdered the rightful King Dunco and usurped his throne. But, in the spirit of great tragedy, the forces of justice are gathered to do battle against McDeath and his depraved minions. Orcs, Men, Dwarfs and Treemen fight it out in a titanic struggle for power, money and alcohol.

The more I learn about stuff like this, the more I realize that I missed out by paying more attention to the early days of Warhammer. Sounds like it was a lot of fun!

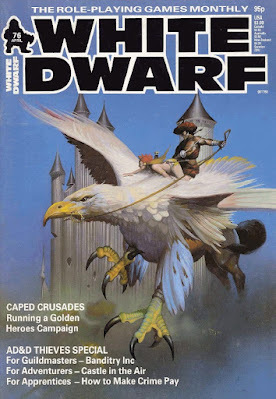

White Dwarf: Issue #76

Issue #76 of White Dwarf (April 1986) features a cover by Peter Andrew Jones, whose art has appeared on the cover of the magazine several times in the past, the most recent being a year before, with issue #64. Like his previous work, this cover is quite striking, depicting a hippogriff – a mythological creature not often shown in fantasy gaming illustrations, so it definitely wins points in my book for its uniqueness (though its inclusion here is in reference to the issue's AD&D adventure).

Issue #76 of White Dwarf (April 1986) features a cover by Peter Andrew Jones, whose art has appeared on the cover of the magazine several times in the past, the most recent being a year before, with issue #64. Like his previous work, this cover is quite striking, depicting a hippogriff – a mythological creature not often shown in fantasy gaming illustrations, so it definitely wins points in my book for its uniqueness (though its inclusion here is in reference to the issue's AD&D adventure).Ian Marsh's editorial notes that the "unannounced demise" of many long-running columns in WD, such as "Starbase" for Traveller, "Heroes & Villains" for superhero gaming, "Crawling Chaos" for Call of Cthulhu, "Rune Rites" for RuneQuest, and, most significantly, "Fiend Factory," a staple of the magazine practically since its inception. Marsh claims that, "with the greater variety of popular games on the market, having a department for each is impractical, and indeed restricts the content of the magazine." Future issues would include articles according to different metrics, such as themes. Issue #76 is the first example of this, focusing as it does on thieves.

The issue begins with a longer than usual "Open Box" that devotes three pages to its many reviews. The first is ICE's Riddle of the Ring boardgame, which received only 6 out of 10. Better reviewed is another ICE product, Ereech and The Paths of the Dead for MERP (9 out of 10). Chaosium's solo Call of Cthulhu adventure, Alone Against the Wendigo, receives 8 out of 10, while the Paranoia scenario, Send in the Clones, is judged slightly more harshly (7 out of 10). TSR's Lankhmar – City of Advenure, meanwhile, gets a rare perfect score (10 out of 10), which is slightly generous in my opinion, but I can't deny that the product is a good one nonetheless. Two adventures for FASA's Dr. Who RPG, The Iytean Menace and Lords of Destiny, are reviewed positively and, oddly, receive a joint rating of 8 out of 10. Finally, there's Hero Games's Fantasy Hero (8 out of 10). That's quite a large number of products for a single issue – and not a single GW product among them!

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" does its usual thing and I do my usual thing of mostly not caring. More interesting to me is the first of this issue's thief-themed articles, "How to Make Crime Pay," by John Smithers. It's written as if it were a lecture given by a guildmaster to apprentice thieves and it's all the better for it. Smithers presents lots of practical advice on how to handle a wide variety of larcenous activities within a fantasy RPG. What makes the article stand out is that its framing device makes it such that the article is useful to both players and referees without having to shift perspectives or divided itself into different sections. Articles of this sort are hard to pull off, so I'm all the more impressed that Smithers succeeded.

"You're Booked" by Marcus L. Rowland is an expansion of Games Workshop's Judge Dredd RPG, introducing the "misunderstood" Accounts Division of Mega-City One's Justice Department. The article lays out the purpose of Acc-Div, as it is known, and how it could be used within a campaign, with several scenario outlines presented as examples. The division is not suitable for Player Judges, but its inclusion in an adventure or campaign could help to flesh out the Justice Department and add a note of levity, as Judges deal with paperwork and expense accounts.

"Glen Woe" is a Warhammer miniatures scenario by Richard Halliwell. It's intended to expand upon the material provided in McDeath – a Shakespeare-inspired scenario pack released around this time. Not being a Warhammer player, I can't to much about the quality of the material presented here, only my amusement at knowing there was ever a miniatures scenario based around MacBeth. "Banditry Inc" by Olivier Legrand looks at thieves guilds within the context of AD&D from the referee's point of view. While hardly revolutionary, it nevertheless raises some useful questions about the organization and operation of the guild that any referee should consider if thieves and thieves guilds become important in his campaign.

"Caped Crusaders" by Peter Tamlyn is a three-page article on "running Golden Heroes campaigns," though most of its advice is equally applicable to superhero campaigns using another RPG system. Tamlyn covers a variety of topics and the quality of his advice will depend, I imagine, on how familiar one is with both refereeing and the superhero genre. I judge it pretty positively myself, though I imagine others might find it old hat. "Thrud the Barbarian," "Gobbledigook," and "The Travellers" are all here, among a handful of only a few remaining connections to the eatly days of White Dwarf. Since I was not a reader of the magazine at this time, I can't help but wonder how much longer they will continue to grace its pages.

"Castle in the Wind" by Venetia Lee, with Paul Stamforth, is a lengthy AD&D scenario aimed at characters of 5th–8th levels. As its title suggests, the adventure concerns the sudden appearance of a "sky castle" above a desert in the campaign area. There are several things that make "Castle in the Wind" stand out aside from its length. First, there's its vaguely Persian setting, a culture that doesn't get much play in fantasy games in my experience. Second, there's the clever design of the sky castle itself (including its hippogriff nests). Finally, there's the open-ended nature of the adventure itself, which spends most of its text presenting a locale rather fleshing out a traditional "plot" for the player characters to follow.

"How Do You Spell That?" presents a collection of six new AD&D spells culled from reader submissions. The article is listed as being part of the "Treasure Chest" column, which surprised me, since so many other standbys of White Dwarf were axed this issue. Part two of Joe Dever's look at oil painting closes out the issue. In addition to the usual color photographs that always accompany it, the article also includes a mixing guide for how best to achieve certain results when using oil paints.

I must admit, I found this issue a bit of a slog. I don't know that it was objectively any worse than most issues. Indeed, I suspect it was probably better than many I'd read in the past. Nevertheless, I can't shake the feeling that the magazine has changed and that change has started to sap my enthusiasm for reading it. Of course, I might simply be tired of this series. Slightly more than three-quarters of the way to 100 issues, I hope I can be forgiven a little White Dwarf fatigue. Still, I will attempt to soldier on for a little while longer.

May 29, 2023

By the Guts of the Green God

I've talked about the Sword of Sorcery comic before. It's a remarkable example of DC's multiple forays into the fantasy genre throughout the 1970s. Like most of the other fantasy comics DC published during that time – Arak, Son of Thunder; Beowulf, Dragon Slayer; Claw the Unconquered, Stalker, The Warlord, and more – Sword of Sorcery didn't last long. However, it has the distinction of having adapted several Fritz Leiber stories to the comics medium, including "Cloud of Hate," which appeared in its fourth issue from October 1973.

As is often the case, the adaptation isn't a straight one, though most of its alterations concern the tale's order of events than their actual content. Likewise, the dialog is not directly taken from Leiber's text, though it's clearly inspired by it. For me, though, the main joy of the comic is its artwork by Howard Chaykin, which is excellent. (In a twist of fate, Chaykin would later return to comics based on Leiber's Lankhmar stories in 2007, only this time as a writer rather than artist.)

As is often the case, the adaptation isn't a straight one, though most of its alterations concern the tale's order of events than their actual content. Likewise, the dialog is not directly taken from Leiber's text, though it's clearly inspired by it. For me, though, the main joy of the comic is its artwork by Howard Chaykin, which is excellent. (In a twist of fate, Chaykin would later return to comics based on Leiber's Lankhmar stories in 2007, only this time as a writer rather than artist.)

DDG Hate

TSR's 1980 AD&D book, Deities & Demigods, includes a chapter devoted to what it calls the "Nehwon Mythos" – characters, monsters, and deities derived from the works of Fritz Leiber's stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. In light of today's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library, I thought it might be fun to post that chapter's write-up of the malevolent entity, Hate.

May 28, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Cloud of Hate

One of the reasons I find pulp fantasies so congenial is that their preferred format, the short story, actively works against tales that are unnecessarily complex and overwrought. Indeed, many of my favorite fantasy stories are little more than situations, in which characters I like encounter a problem and then use their wits in order to overcome it. The stakes are straightforward and largely personal – nothing epic or world-changing, just a simple yarn in which cleverness and swordplay win the day for the protagonist (I don't say "hero," because the best pulp fantasy characters would probably blanch at being called such).

One of the reasons I find pulp fantasies so congenial is that their preferred format, the short story, actively works against tales that are unnecessarily complex and overwrought. Indeed, many of my favorite fantasy stories are little more than situations, in which characters I like encounter a problem and then use their wits in order to overcome it. The stakes are straightforward and largely personal – nothing epic or world-changing, just a simple yarn in which cleverness and swordplay win the day for the protagonist (I don't say "hero," because the best pulp fantasy characters would probably blanch at being called such).Of course, the truly great writers of pulp fantasy were capable of threading the needle, so to speak, by doing everything I just described above and nevertheless finding a way to invest it with greater significance. Fritz Leiber was such a writer and his stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser demonstrate this again and again. Take, for example, "The Cloud of Hate," which first appeared in the May 1963 issue of Fantastic Stories of Imagination. On the one hand, it's just another story of the Twain on the make, but, on another, there are intimations of their adventures having a larger significance, even if they do not realize it.

"The Cloud of Hate" opens, not with the protagonists, but beneath the streets of Lankhmar, in the subterranean Temple of Hates, "where five thousand worshipers knelt and abased themselves and ecstatically pressed foreheads against the cold and gritty cobbles as the trance took hold and the human venom rose in them."

The drumbeat was low. And save for snarls and mewlings, the inner pulsing was inaudible. Yet together they made a hellish vibration which threatened to shake the city and land of Lankhmar and the whole world of Nehwon.

Lankhmar had been at peace for many moons, and so the hates were greater. Tonight, furthermore, at a spot halfway across the city, Lankhmar's black-togaed nobility celebrated in merriment and feasting and twinkling dance the betrothal of their Overlord's daughter to the Prince of Ilthmar, and so the hates were redoubled.

This ritual within the Temple of Hates – what a wonderfully evocative name! – has a purpose beyond mere worship. Led by the Archpriest of the Hates, the worshipers have called forth "tendrils, which in another world might have been described as ectoplasmic" which "quickly multiplied, thickened, lengthened, and then coalesced into questing white serpentine shapes" and then billowed out of the temple to the streets above. Once there, this "billowing white" fog "in which a redness lurked" began to seek out victims among Lankhmar's populace.

It's at this point that the reader is introduced to Fafhrd and the Mouser, who are employed as watchmen during the aforementioned festivities in honor of the Overlord's daughter. The northerner states that "There'll be fog tonight. I smell it coming from the Hlal." His smaller companion is dubious of his prognostication, but Fafhrd insists "There's a taint in the fog tonight." Meanwhile, the fog summoned at the Temple of Hates makes its way into the Rats' Nest tavern, where it finds "the famed bravo Gnarlag." Touching him with a "fog-finger,"

Gnarlag's sneering look turned to one of pure hate, and the muscles of his forearm seemed to double in thickness as he rotated it more than a half turn.

Elsewhere, Mouser asks his friend about their lot in life, specifically why they are not dukes or emperors or demigods. Fafhrd explains that it's because they're "no man's man ... We go our own way, choosing our own adventures – and our own follies! Better freedom and a chilly road than a warm hearth and servitude." Mouser is skeptical of these explanations, pointing out how often they've chosen to serve others, but their philosophizing is interrupted by Fafhrd once again stating that something ill is afoot. His sword, he says, "hums a warning! ... The steel twangs softly in its sheath!" And once again, Mouser expresses disbelief.

The fog continues to make its way through Lankhmar, seeking out first "Gis the cutthroat" and then "the twin brothers Kreshmar and Skel, assassins and alleybashers by trade." In each case, the fog

intoxicated them as surely as if it were a clouded white wine of murder and destruction, zestfully sluicing away all natural cautions and fears, promising an infinitude of thrilling and most profitable victims.

The "hate-enslaved" marched together in the fog "toward the quarter of the nobles and Glipkerio's rainbow-lanterned palace above the breakwater of the Inner Sea." Unfortunately for them, the Twain stand guard this night.

"The Cloud of Hate" is one of Leiber's shorter stories of Nehwon, but that works to its advantage in my opinion. Its brevity enables it to focus on what most matters, namely the inexorable movement of the otherworldly fog across the city of Lankhmar and the point when Fafhrd and the Mouser come into contact with it. This meeting is compelling first because the Mouser is initially so dismissive of the idea that there is anything odd happening and second because the reader has no idea what effect the fog might have on these comrades-in-arms. Would they, like all the others before them, become "hate-enslaved" or might they somehow escape this horrible fate? Leiber's answer to this and other questions is clever and offers insights into two of the most fascinating characters in fantasy – highly recommended.

May 26, 2023

Secrets (Again)

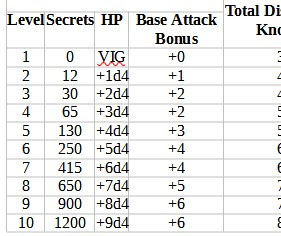

Earlier this month, I posted about my fumbling attempts to come up with an alternative to D&D-style abstract experience points for use in Secrets of sha-Arthan. I received a lot of helpful comments and they, along with private discussions and internal playtesting of the game's draft rules, have begun to bring me closer to a satisfactory solution. That said, there's still a lot of work to be done to get it just right, but then that's the sort of thing with which wider playtesting should help.

It is by now a truism, I think, to state that a roleplaying game's experience/advancement system, whatever form it takes, encourages certain activities and approaches to play by rewarding them. For example, Dungeons & Dragons awards experience points primarily on the basis of treasure, with a smaller but still more significant amount of XP given for defeating opponents. Consequently, D&D, at least in its classical form, is a game where treasure hunting and monster slaying take center stage, since those are the activities by which experience points are earned and characters can advance in levels. Advancement comes through different activities in other games, such as skill use in those derived from Basic Role-Playing.

If you're involved with any RPG long enough, you may notice that players sometimes begin to modify the way they play in accordance with what nets their characters the most in-game rewards. When I was a kid, I distinctly remember occasions when my friends would actively seek out "a few more experience points" by having their characters wander through the wilderness hoping that a random encounter would bring enough XP to achieve the next level. Players of BRP games are, of course, familiar with the phenomenon of "check mongering," in which players seek excuses to make skill checks for their characters, in the hopes of improving them.

I don't necessarily see anything wrong with this kind of emergent behavior. At base, RPGs are games and it's only natural – rational even – that players will try to find ways to use a game's rules to their advantage. Rather than attempting to find ways to disincentivize this behavior in Secrets of sha-Arthan, my instinct is to find ways to harness it to encourage the kind of adventures and campaigns that I enjoy, hence the shift to the accumulation of secrets rather than XP as the method of advancement.

But what qualifies as a secret? There are two kinds of secrets. The first is mundane, namely, a fact about the setting that the character does not yet know. For example, encountering Unmaker cultists for the first time would certainly qualify as a secret in this first sense. For that matter, encountering almost any "monster" for the first time is also a secret. There are many other secrets in this sense – traveling to a far-off city, locating the entrance to a Vault, becoming aligned with a faction or cult, even coming into possession of a magic item.

But what qualifies as a secret? There are two kinds of secrets. The first is mundane, namely, a fact about the setting that the character does not yet know. For example, encountering Unmaker cultists for the first time would certainly qualify as a secret in this first sense. For that matter, encountering almost any "monster" for the first time is also a secret. There are many other secrets in this sense – traveling to a far-off city, locating the entrance to a Vault, becoming aligned with a faction or cult, even coming into possession of a magic item.However, there's a second type of secret, one that's closer to the usual sense in which the word is used. A secret of this type is something genuinely hidden or unknown, knowledge of which is rare within the setting. It's one thing simply to encounter the aforementioned Unmaker cultists, but it's another thing entirely to understand their origins and the nature of their beliefs. Likewise, many creatures, magic items, and spells tie into obscure aspects of sha-Arthan. These are the "true" secrets of the game.

I opted for this approach to character advancement because I hope it will encourage the kind of gameplay I most enjoy. Both my earlier Dwimmermount OD&D campaign and my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaigns are rooted in the uncovering of secrets of their respective settings. Refereeing House of Worms in particular has taught me that piecing together disparate pieces of knowledge about a setting can be very compelling to players. Indeed, it can become a powerful driver of both player and character engagement.

As the players could tell you, House of Worms is comparatively light on combat and treasure seeking; its main focus is and always has been on exploration of its setting and wrestling with the secrets thereof. The campaign's recent shift is toward an even greater focus on these matters and there is (as yet) no sign that this has in any way made the campaign less compelling – quite the opposite, in fact. It's my hope that I can "bottle" this approach in Secrets of sha-Arthan by not only being very explicit about its emphasis on exploration of its setting but also by rewarding such exploration in its advancement system. I can't pretend that it will be easy to do this well, but, armed with more than eight years of experience in this arena, I feel I have as good a chance as anyone to succeed.

Onward!

May 25, 2023

Into the Vaults

I've devoted much of May to writing the latest playtest draft of Secrets of sha-Arthan. The project is coming along quite well, though – as usual – still slower than I would like. Nevertheless, serious progress has been made and I expect to start putting the latest version of the game through its paces sometime this summer.

I've devoted much of May to writing the latest playtest draft of Secrets of sha-Arthan. The project is coming along quite well, though – as usual – still slower than I would like. Nevertheless, serious progress has been made and I expect to start putting the latest version of the game through its paces sometime this summer.As if to buoy my spirits, I was delighted to receive the illustration above from the ever-impressive Zhu Bajiee, who's already produced so much wonderful artwork for SosA. Depicted are a quintet of Vault explorers preparing to face off against some eldritch threat. They are:Vandar Axtargo (center front), a warrior and veteran of the army of the king of Eshkom, now turned mercenary.Wentak (right), a sorcerer whose origins are mysterious but who turned up in the First City about six months ago and soon attached himself to the Supernal Academy of Alatash.Maltisis (center back), a scion of the Arta Char dynasty that has prospered in recent years due to its alliance with the ruling Chomachto.Sharaya (left), an adept of the Jorazi people of the Ridala district of Inba Iro and another recent arrival to da-Imer.Limber-but-Unbending (center left), a Chenot master of the bow who, like so many of his kind, seeks the blessings of the Makers in the Vaults beneath the First City.I'm having a lot of fun fleshing out the setting of the game, which takes a lot of its inspiration from Antiquity, particularly the Hellenistic Age, a period of real world history I find quite fascinating and one that tends to get overlooked, sandwiched as it is between Classical Greece and the rise of Rome. I'll have lots more to say about Secrets of sha-Arthan in the coming months, but, for now, I simply wanted to share this great illustration that I hope provides a little insight into the look and feel of its setting.

May 24, 2023

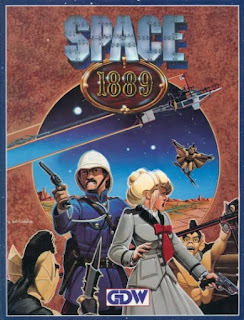

Retrospective: Space: 1889

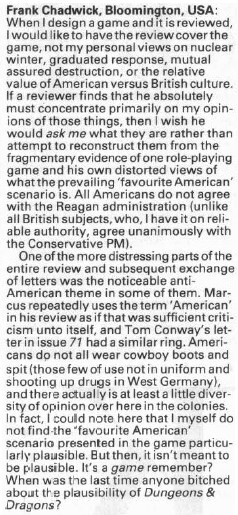

Seeing Frank Chadwick's letter in issue #75 of White Dwarf reminded me that he was one of GDW's top designers during that storied game company's nearly quarter-century of existence. While he's probably best known for his work on board and miniatures wargames like Command Decision and Europa, he was also responsible for, either solely or in part, many of GDW's roleplaying games, starting with En Garde!.

Seeing Frank Chadwick's letter in issue #75 of White Dwarf reminded me that he was one of GDW's top designers during that storied game company's nearly quarter-century of existence. While he's probably best known for his work on board and miniatures wargames like Command Decision and Europa, he was also responsible for, either solely or in part, many of GDW's roleplaying games, starting with En Garde!.

I first encountered Chadwick's name in connection with Traveller and, later, with Twilight: 2000, both of which I played a great deal in my younger days (and nowadays too, as it turns out). In addition, Chadwick designed another of GDW's RPGs, Space: 1889, which first appeared, ironically, in 1988. This is only a year after SF author K.W. Jeter first coined the term "steampunk," though I don't recall its being widely used at the time. Certainly, Space: 1889 never makes use of it, instead referring players to the works of Verne, Wells, and other late 19th century science fiction pioneers as its sources of inspiration.

The premise of the game is that, in 1870, Thomas Edison succeeded – somewhat accidentally – in demonstrating the possibility of navigating the "luminiferous ether" between the planets of our solar system. In doing so, Edison not only opened up new frontiers for exploration (and exploitation), he also made possible contact between human beings and the intelligent inhabitants of Venus, Mars, and even the Moon. By 1889, the Great Powers of Earth were vying with one another for control of these new worlds with a zeal that made the scramble for Africa seem halfhearted by comparison.

One of the things that makes Space: 1889 so interesting is that its setting isn't merely an alternate history where space travel is possible in the Victorian Age. Rather, it's a full-fledge alternate reality where the 1887 Michaelson-Morley experiment did not suggest, as it actually did, that there was no such thing as ether. Chadwick makes use of earlier, now-rejected scientific theories to construct an alternate model of physics for the game's setting, one conducive to the great tales of scientific romance whose echoes can be heard even today in the pulpier corners of science fiction and fantasy. This approach gives Space: 1889 an oddly "grounded" feel to it, because it's clear that thought went into its idiosyncratic "scientific" principles, which are used to good effect throughout.

Indeed, it's the setting that made Space: 1889 so compelling to me at the time of its release – and it's the setting that continues to fascinate me, even today. Like all good wargamers, Chadwick knows his history and the game does a good job, I think, of presenting the late 19th century, warts and all, as an interesting place for science fiction adventure. The rivalries of the Great Powers, for example, serve as the backdrop to much of what happens in the setting, albeit from a decidedly Anglocentric perspective. For instance, Germany is portrayed in a negative light, as is, to a lesser extent, Belgium. That said, the British Empire is not presented in an unambiguously positive light. Like any honest portrayal, its vices are as significant as its virtues.

Even more interesting than the game's use of real aspects of the 19th century is its use of purely imaginative one, such as the various non-human beings that dwell on other worlds. Mars gets a lot of attention in the game, no doubt due to its importance in early science fiction. As often the case in those tales, the Martians of 1889 are an ancient, dying people, heirs to 35,000 years of civilization, at once contemptuous of Earthmen for their comparative barbarism and envious of their expansionist vigor. During the few short years that GDW published Space: 1889 – 1988 to 1991 – Mars received a fair bit of development through adventures and supplements. One of the best, Canal Priests of Mars was written, amusingly enough, by Marcus L. Rowland, the man responsible for the scathingly negative review of Chadwick's Twilight: 2000 in issue #68 of White Dwarf. Rowland would later go on to produce the Forgotten Futures series that looked at Victorian SF as potential settings for roleplaying.

Unfortunately, the cleverness and promise of Space: 1889's setting was hampered by a less than stellar system that, by turns, is either too simplistic or too complex for its purpose. This was something I recognized immediately upon reading the book; it was confirmed in multiple attempts to play the game with friends who were just as enthusiastic about the setting as I. It's a great shame, because the game's setting is well done and ripe with potential, but the game's mechanics were actively off-putting – so much so that I never succeeded in playing Space: 1889 for very long. I understand that, in the years since, there have been a couple of attempts to revive the setting with new rules, though I know nothing of how successful these attempts proved.

In the end, Space: 1889 is one of those roleplaying games that comes along every so often that grabs my attention because of what I see as its promise, but which I eventually discover is somehow inadequate to it in some way. Calling it a "disappointment" is not completely fair, since I nevertheless find many aspects of it genuinely praiseworthy. At the same time, I can think of no other way to sum up my feelings toward it without damning it with faint praise. A pity!

May 22, 2023

White Dwarf: Issue #75

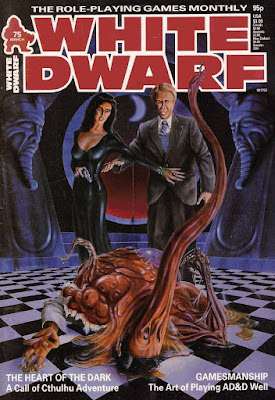

Issue #75 of White Dwarf (March 1986) sports a horror – or I should I say Call of Cthulhu? – themed cover by Lee Gibbons, whose work appeared several times in the past few months, most notably issue #72. This issue marks a changing of the guard at the magazine, with Ian Marsh taking over its reins from Ian Livingstone. In his inaugural editorial, Marsh admits to "an element of trepidation" about his new job, especially at a time when WD is "mutating slowly into a different beastie." He elaborates on this, explaining that there is a "shift away from the usual formulaic style" of the magazine, by which I think he means an end to the regular, monthly columns and other features that have defined its content since the beginning. Regardless, the times, they are a'-changin' at the Dwarf.

Issue #75 of White Dwarf (March 1986) sports a horror – or I should I say Call of Cthulhu? – themed cover by Lee Gibbons, whose work appeared several times in the past few months, most notably issue #72. This issue marks a changing of the guard at the magazine, with Ian Marsh taking over its reins from Ian Livingstone. In his inaugural editorial, Marsh admits to "an element of trepidation" about his new job, especially at a time when WD is "mutating slowly into a different beastie." He elaborates on this, explaining that there is a "shift away from the usual formulaic style" of the magazine, by which I think he means an end to the regular, monthly columns and other features that have defined its content since the beginning. Regardless, the times, they are a'-changin' at the Dwarf."Open Box," for example, consists almost entirely of reviews of Games Workshop products, starting with the Supervisors Kit for Golden Heroes (8 out of 10) and Terror of the Lichemaster (9 out of 10) for use with Warhammer. There's also a review of Judgment Day (9 out of 10), an adventure for Judge Dredd – The Role-Playing Game. Rounding out the GW products covered this issue is its edition of the venerable science fiction boardgame Cosmic Encounter (also 9 out of 10 – I'm sensing a theme here). Finally, there's a look at Chaosium's second Call of Cthulhu companion, Fragments of Fear, which earns 7 out of 10. While it's inevitable that a periodical published by a company involved in the industry it's covering will include reviews of products it also publishes – TSR's Dragon certainly did – I nevertheless can't help but feel a line was crossed this issue, given the preponderance of Games Workshop releases reviewed. Perhaps next issue will be better?

I feel like a bad person for only enjoying Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" when he snarks about books about books and authors I, too, dislike. This month he brings the hammer down on the Darkover novel, Hawkmistress:

There will no doubt be hordes more 'Darkover' tales from Marion Zimmer Bradley: publishers love issuing books very similar to previous ones. Hawkmistress ... despite its veneer of science-fantasy, seems hauntngly familiar. Heroine Romilly wears breeches and gets on well with animals, but Daddy wants her to don girlish clothes and marry. One knows instantly that the chap Romilly finds most loathsome is Daddy's intended bridegroom: and so it proves. With hawk and horse our heroine to find her way in the world.The interesting thing about Langford's critique of the novel is not that he thinks it's bad – he calls its "a readable yarn" – but that it is essentially a romance novel in very thin science fantasy dress, which I think is a fair criticism of her oeuvre (and that of Anne McCaffrey, come to think of it).

"Getting the Fright Right" is this month's installment of Colin Greenland's "2020 Vision" column. It's a collection of reviews of then-current horror movies, broadly defined, ranging from The Return of the Living Dead to Fright Night to Teen Wolf. Greenland's reviews of these films is interesting, because, as the article's title suggests, he takes some time to talk about the proper balance of thematic elements within a horror movie to make it enjoyable for him. I like this approach to reviews, since, even when I disagree with them, I at least understand where the reviewer is coming from and that's quite useful.

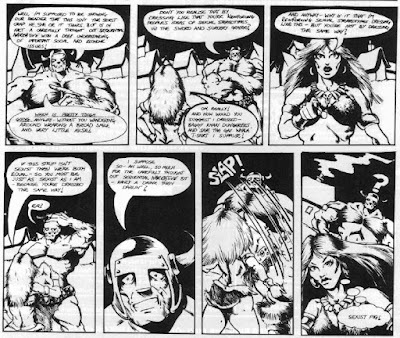

"Thrud Gets a Social Conscience" is this issue's installment of "Thrud the Barbarian," humorously addressing the claim that the comic (and, by extension, the entire genre of sword-and-sorcery) is sexist. This leads to an amusing exchange between Thrud and his occasional female guest star, Lymara the She-Wildebeest, about how her attire reinforces negative sexual stereotypes.

There are also new installments of "Gobbledigook" and "The Travelles," but they're not nearly as amusing.

There are also new installments of "Gobbledigook" and "The Travelles," but they're not nearly as amusing.Oliver Dickinson's "RuneQuest Ruminations" is a look at the third edition of RQ (published by Avalon Hill) with a special focus on those parts of its rules that he found vexing or inadequate in some way. A lot of the article is very "inside baseball" to someone like myself whose experience with RuneQuest is limited. What most comes across, though, is how much of a shock and disappointment this edition of the game was to many of its long-time fans, particularly in the way that it downgraded Glorantha to the status of an afterthought.

"How to Save the Universe" by Peter Tamlyn is a lengthy and thoughtful look at "the delights of superhero gaming." Tamlyn's main point seems to be that there are a lot of different styles of play within superhero RPGs – more than enough to satisfy almost every preference. Consequently, one should not dismiss the entire genre as "kid's stuff." "Gamesmanship" by Martin Hytch is an oddly titled but similarly lengthy and thoughtful look at "injecting a little mystery" back into AD&D adventures. The overall thrust of the article concerns the way experienced players treat so many of the game's challenges in a procedural fashion, quoting rules and statistics rather than entering into the fantasy of it all. It's difficult to summarize Hytch's advice in a short space; suffice it to say that it's mostly quite good and filled with useful examples. I may write a separate post about it, because I think he does an excellent job of addressing the many questions he raises.

"Mass Media" by Andrew Swift looks at the nature of communications technology at various tech levels in Traveller. It's fine for what it does but nothing special. On the other hand, Graeme Davis's "Nightmare in Green" AD&D adventure is phenomenal. Aimed at 4th–6th level characters, it concerns the threat posed a collection of nasty, plant monsters crossbred by a mad druid. I'm a big fan of plant monsters, so this scenario immediately caught my attention, all the more so since some of the monsters are inspired by the works of Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith.

That brings us to another highlight of this issue. You may recall that, back in issue #68, reviewer Marcus L. Rowland gave a very negative review to GDW's Twilight: 2000. This led to a flurry of letters in issue #73, both pro and con Rowland's review. With this issue, Frank Chadwick, designer of the game weighs in and he pulls no punches.

"The Heart of the Dark" by Andy Bradbury is "an illuminatingly different" Call of Cthulhu scenario, because it does not directly feature any encounters with the Mythos or its associated entities. Indeed, the adventure includes no game statistics of any kind "since it is doubtful that they will be needed." This is a pure, roleplaying scenario filled with lots of investigation, social interactions, and red herrings. It's intended as a change of pace

"The Heart of the Dark" by Andy Bradbury is "an illuminatingly different" Call of Cthulhu scenario, because it does not directly feature any encounters with the Mythos or its associated entities. Indeed, the adventure includes no game statistics of any kind "since it is doubtful that they will be needed." This is a pure, roleplaying scenario filled with lots of investigation, social interactions, and red herrings. It's intended as a change of pace "Local Boy Makes Good" by Chris Felton looks at character background in AD&D, with lots of random tables for determining social class, birth order, father's profession, and so on. I suppose this could be of interest to others, but not to me. Finally, Joe Dever begins a new series on preparing and using oil paints for miniature figures. I know nothing about this topic; despite that, I find it weirdly fascinating, like all of Dever's articles in his monthly "Tabletop Heroes" column.

Issue #75 of White Dwarf continues the recent trend of feeling slightly "off" to my sensibilities. There's still plenty of excellent content, but there's also an increasingly detectable undercurrent of change and not for the better. Perhaps I am simply hypersensitive to this because I know that WD will soon be little more than a house organ for Games Workshop and I am constantly one the lookout for signs – any signs – of this imminent transformation. Regardless, I will keep plowing ahead, though, for how much longer, I don't yet know.

May 21, 2023

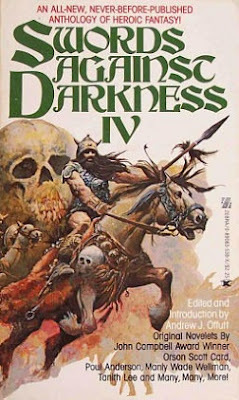

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Edge of the World

1979 saw the publication of not one but two different stories of Kardios of Atlantis by Manly Wade Wellman: "The Seeker in the Fortress" and "The Edge of the World." The former appeared in Gerald W. Page and Hank Reinhardt's Heroic Worlds anthology, while the latter graced the pages of the fourth (and penultimate) entry in Andrew J. Offutt's long-running Swords Against Darkness series. Kardios had appeared in every previous volume of Swords Against Darkness, so it's hardly surprising he'd turn up there again.

1979 saw the publication of not one but two different stories of Kardios of Atlantis by Manly Wade Wellman: "The Seeker in the Fortress" and "The Edge of the World." The former appeared in Gerald W. Page and Hank Reinhardt's Heroic Worlds anthology, while the latter graced the pages of the fourth (and penultimate) entry in Andrew J. Offutt's long-running Swords Against Darkness series. Kardios had appeared in every previous volume of Swords Against Darkness, so it's hardly surprising he'd turn up there again.

"The Edge of the World" receives its title from the "mighty city of Kolokoto," which lay, seemingly literally, at the edge of "a terrifying nothingness" that marked the world's end. Of course, Wellman elicits the reader's skepticism about this supposed fact early on, as he notes that it was "the sixty or so priests who did most of the thinking for Kolokoto's citizens" who declared this to be so. The subsequent unfolding of the story does little to lessen that skepticism.

Kardios enters the story first by word of mouth, as one of the aforementioned priests, Mahleka, has an audience with Kolokoto's "disdainfully beautiful" queen, Iarie. The queen, who is "as dictatorial as she was lovely," sits upon an ebony throne guarded by two tamed monsters.

One of these, the rather molluscoid Ospariel, was carapaced in a green shell, from which peered brilliant eyes above a stir of tentacles. The other, Grob, might be a great crouching ape, if apes had branched horns and were covered with green scales the size of lily pads.

Iarie has summoned the priest to find out the source of a "disturbance among the people," one that she had heard "shouted over the lower market-reaches." Mahleka explains that "the people [have] gathered to welcome Kardios the wanderer."

Iarie has heard the name of Kardios before, who was reputed to have survived the sinking of Atlantis, "overthrown mighty rulers," "conquered monsters," and "brought to an end the worship of several gods." This interests the queen, who asks that the Atlantean be brought before her, but Mihaka, as "her chief and most knowledgeable advisor," is already one step ahead of his mistress. "I've already ordered that done," he explains.

Though initially viewing him with contempt, Iarie soon becomes intrigued by Kardios, especially after learning that he had entertained the people in the marketplace with a song dedicated to the goddess "Ettaire, the bringer of love." She asks him to sing her the same song, which he does. So impressed is she by his skill that she commands him to take dinner with her that very evening, to which Kardios readily agrees.

Over dinner, Kardios and Iarie discuss the religion of Kolokoto and its chief god, Litoviay, who is "worshipped by acts of mischief." This piques Kardios' interest, causing him to wonder why the god's priests forbid anyone to travel over the mountain range that separates the city from the edge of the world. "Why not let the people go over the range and fall into space? That would be in character." Iarie shrugs off such questions, since she is much more interested in making the Atlantean wanderer "especially happy." She sends away her servants and takes Kardios, along with a flagon of wine, to her bedchamber so that they may "talk, mostly of the love-goddess Ettaire, and how best to worship her."

The next morning, Kardios is awakened by "two burly men in black chain mail" holding curved swords. Iarie explains to him that they are her "most discreet guardsmen ... Safe with my secrets, for both are mute." She adds, "Kardios, I'm sorry you woke. I had hoped you would die happy."

"You'd murder me so that I would not tell?" he asked Iarie, and her smile grew the more triumphant.

"How accurately you estimate the situation," she answered him sweetly. "I'm a lonely woman, and from time to time I invite a stranger to divert me overnight. Naturally, I can't let such partners go and gossip about it. What would my people think?"

Kardios manages to knock the two guardsmen unconscious. The queen, undeterred, sets Ospariel and Grob on him, which he also defeats, thanks to his star metal sword. With no more tricks up her sleeve, Iarie resorts to crying rape, which summons more guards to her bedchamber. The Atlantean flees into the depths of the palace to avoid capture, succeeding only because a young weaver-girl named Wanendi gives him a place to hide undetected (once again cribbing a page from Conan – and from himself).

From Wanendi he learns much about the city, its queen, and its place at the edge of the world.

Kolokoto, said Wanendi, had been built many generations ago for the announced purpose of discouraging travelers from falling off the edge of the world. It was a manufacturing city, with a thriving trade in excellent textiles. Royalty and certain merchants got the profits. Weavers like Wanendi managed to live just short of want. Queen Iarie was the latest tyrant to uphold the law of not crossing Fufuna into nothingness, and the mischief-god Litoviay marshalled a line of stone sentinels to enforce that law.

The girl also provides Kardios with some clothing that will enable him to blend in better with the locals. He repays her for this and her other kind deeds with treasure he acquired in Nyanyanya before setting off with the intention of escaping over the barrier mountain range – a feat no one had ever accomplished before. Of course, that's easier said than done ...

"The Edge of the World" is another enjoyable Kardios yarn, engagingly told. I am constantly impressed by how charmingly Wellman spins these tales, filled as they are with the well-worn tropes and clichés of pulp fantasy. It's evidence, I suppose, that a master is capable of producing something worthwhile even out of the basest materials. Once again, I cannot recommend these stories enough. I was very pleasantly surprised by them and I suspect many of you will be as well.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers