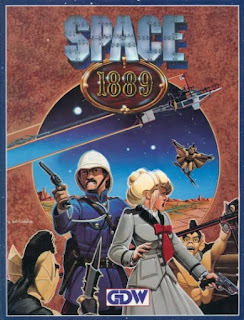

Retrospective: Space: 1889

Seeing Frank Chadwick's letter in issue #75 of White Dwarf reminded me that he was one of GDW's top designers during that storied game company's nearly quarter-century of existence. While he's probably best known for his work on board and miniatures wargames like Command Decision and Europa, he was also responsible for, either solely or in part, many of GDW's roleplaying games, starting with En Garde!.

Seeing Frank Chadwick's letter in issue #75 of White Dwarf reminded me that he was one of GDW's top designers during that storied game company's nearly quarter-century of existence. While he's probably best known for his work on board and miniatures wargames like Command Decision and Europa, he was also responsible for, either solely or in part, many of GDW's roleplaying games, starting with En Garde!.

I first encountered Chadwick's name in connection with Traveller and, later, with Twilight: 2000, both of which I played a great deal in my younger days (and nowadays too, as it turns out). In addition, Chadwick designed another of GDW's RPGs, Space: 1889, which first appeared, ironically, in 1988. This is only a year after SF author K.W. Jeter first coined the term "steampunk," though I don't recall its being widely used at the time. Certainly, Space: 1889 never makes use of it, instead referring players to the works of Verne, Wells, and other late 19th century science fiction pioneers as its sources of inspiration.

The premise of the game is that, in 1870, Thomas Edison succeeded – somewhat accidentally – in demonstrating the possibility of navigating the "luminiferous ether" between the planets of our solar system. In doing so, Edison not only opened up new frontiers for exploration (and exploitation), he also made possible contact between human beings and the intelligent inhabitants of Venus, Mars, and even the Moon. By 1889, the Great Powers of Earth were vying with one another for control of these new worlds with a zeal that made the scramble for Africa seem halfhearted by comparison.

One of the things that makes Space: 1889 so interesting is that its setting isn't merely an alternate history where space travel is possible in the Victorian Age. Rather, it's a full-fledge alternate reality where the 1887 Michaelson-Morley experiment did not suggest, as it actually did, that there was no such thing as ether. Chadwick makes use of earlier, now-rejected scientific theories to construct an alternate model of physics for the game's setting, one conducive to the great tales of scientific romance whose echoes can be heard even today in the pulpier corners of science fiction and fantasy. This approach gives Space: 1889 an oddly "grounded" feel to it, because it's clear that thought went into its idiosyncratic "scientific" principles, which are used to good effect throughout.

Indeed, it's the setting that made Space: 1889 so compelling to me at the time of its release – and it's the setting that continues to fascinate me, even today. Like all good wargamers, Chadwick knows his history and the game does a good job, I think, of presenting the late 19th century, warts and all, as an interesting place for science fiction adventure. The rivalries of the Great Powers, for example, serve as the backdrop to much of what happens in the setting, albeit from a decidedly Anglocentric perspective. For instance, Germany is portrayed in a negative light, as is, to a lesser extent, Belgium. That said, the British Empire is not presented in an unambiguously positive light. Like any honest portrayal, its vices are as significant as its virtues.

Even more interesting than the game's use of real aspects of the 19th century is its use of purely imaginative one, such as the various non-human beings that dwell on other worlds. Mars gets a lot of attention in the game, no doubt due to its importance in early science fiction. As often the case in those tales, the Martians of 1889 are an ancient, dying people, heirs to 35,000 years of civilization, at once contemptuous of Earthmen for their comparative barbarism and envious of their expansionist vigor. During the few short years that GDW published Space: 1889 – 1988 to 1991 – Mars received a fair bit of development through adventures and supplements. One of the best, Canal Priests of Mars was written, amusingly enough, by Marcus L. Rowland, the man responsible for the scathingly negative review of Chadwick's Twilight: 2000 in issue #68 of White Dwarf. Rowland would later go on to produce the Forgotten Futures series that looked at Victorian SF as potential settings for roleplaying.

Unfortunately, the cleverness and promise of Space: 1889's setting was hampered by a less than stellar system that, by turns, is either too simplistic or too complex for its purpose. This was something I recognized immediately upon reading the book; it was confirmed in multiple attempts to play the game with friends who were just as enthusiastic about the setting as I. It's a great shame, because the game's setting is well done and ripe with potential, but the game's mechanics were actively off-putting – so much so that I never succeeded in playing Space: 1889 for very long. I understand that, in the years since, there have been a couple of attempts to revive the setting with new rules, though I know nothing of how successful these attempts proved.

In the end, Space: 1889 is one of those roleplaying games that comes along every so often that grabs my attention because of what I see as its promise, but which I eventually discover is somehow inadequate to it in some way. Calling it a "disappointment" is not completely fair, since I nevertheless find many aspects of it genuinely praiseworthy. At the same time, I can think of no other way to sum up my feelings toward it without damning it with faint praise. A pity!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers