James Maliszewski's Blog, page 77

May 1, 2023

A Musical Odyssey

Every now and again, I come across evidence of a Dungeons & Dragons-related product I'd never heard of. Today, it's First Quest: The Album.

Released in 1985 as a double album (in both vinyl LP and cassette form), it's apparently a narrated AD&D adventure accompanied by instrumental synth music. What's interesting is that, nearly a decade later, in 1994, TSR would sell a different product under the name of First Quest – a boxed introduction to roleplaying games that included an audio CD for use with a starting adventure.

Released in 1985 as a double album (in both vinyl LP and cassette form), it's apparently a narrated AD&D adventure accompanied by instrumental synth music. What's interesting is that, nearly a decade later, in 1994, TSR would sell a different product under the name of First Quest – a boxed introduction to roleplaying games that included an audio CD for use with a starting adventure. Since I have never seen either of these products, I'd be curious to know more about them, especially the 1985 album.

April 30, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Guest of Dzinganji

Having enjoyed re-reading Manly Wade Wellman's "The Dweller in the Temple" for last week's installment of the Pulp Fantasy Library, I decided to work my way through his remaining three tales of Kardios and using them as the basis for new posts. Before turning to the third in the series, "The Guest of Dzinganji," which first appeared in the Andrew Offutt-edited anthology, Swords Against Darkness III in 1978, I briefly wanted to make a couple of general comments about pulp fantasy literature that are relevant to all the stories of Kardios (and, by extension, to many similar pieces of fiction).

Having enjoyed re-reading Manly Wade Wellman's "The Dweller in the Temple" for last week's installment of the Pulp Fantasy Library, I decided to work my way through his remaining three tales of Kardios and using them as the basis for new posts. Before turning to the third in the series, "The Guest of Dzinganji," which first appeared in the Andrew Offutt-edited anthology, Swords Against Darkness III in 1978, I briefly wanted to make a couple of general comments about pulp fantasy literature that are relevant to all the stories of Kardios (and, by extension, to many similar pieces of fiction).First, I think it's easy to overlook just how important anthologies were to the survival and growth of sword-and-sorcery literature during the period between the late 1960s and early 1980s. That's because the native form of this style of fantasy is the short story, the publication of which had previously depended on magazines, many of which, like Weird Tales, declined or ceased publication entirely by the start of the '50s. This turn of events left a void in the market that anthologies would eventually fill. Though published less often than their pulp predecessors, these anthologies were nevertheless significant vectors for the transmission of pulp fantasy sensibilities to a new generation of readers.

Second – and this comment is especially relevant in the case of the present tale – there can be little denying that pulp fantasies frequently used and re-used the same basic plots and story elements. How many of them, for example, involve a lone wanderer entering a new place and stumbling upon some problem whose solution has eluded every previous person who's come across it? This is not a weakness in my opinion, as the enjoyment of almost any story lies not in its specific components but in how the author makes use of them. There can thus be multiple stories with the same basic set-up but whose executions vary considerably, some good and some bad.

In the case of "The Guest of Dzinganji," I feel that Wellman has achieved the former: a good story that makes use of commonplace pulp fantasy elements. These elements are, in fact, so commonplace that Wellman has already made use of them in his previous Kardios yarns. Yet, he somehow manages to use them one more time in this fun little adventure. As with "The Dweller in the Temple," Kardios follows an unknown trail and sings an improvised song as he strums his harp. This time, though, the trail abruptly ends at "an abyss as deep as any he had ever seen."

Down it went, down, down. Standing on the rocky shelf where the trail stopped, he peered. Hazy blue distance below. As he studied that depth, a flat click sounded in the air. He looked up.

Twelve times his length across, another cliff soared into the sky. Against the settling sun moved a dull-shiny something. It hung from chains to a great road or cable that came from far above where the ohter clilff's overhang held it. It was like a great metal basket drifting toward him. He drew back, wondering if his sword would be needed.

Kardios soon realizes that the basket is some kind of conveyance up the cliff-face. As he watches it travel up and down, he hears "a dry voice," which orders him, "Go away and forget." The voice comes from "a man in a ragged gray gown" who sat farther along the ledge between the two cliffs. The nameless old fellow seems to be a seer of some kind, for he knows the name of Kardios, as well as his role in sinking Atlantis. He explains to the wanderer that he has stayed here on the ledge "to warn men to turn back from Flaal. But the tales of treasure draw them. They never return."

The old man urges Kardios not to "let greed tempt you into Flaal."

"What happens to those who go there?"

The white head shook. "My wisdom doesn't reach to Flaal; magic shuts me out. I know only that Dzinganji rules there with a ready ear to listen for visitors and a ready method to entertain them. Dzinganji is a god, Kardios, and an evil one."

"I've met evil gods," said Kardios. "I killed Fith, who oppressed the giant Nephol tribe. I killed Tongbi, who was unpleasantly worshipped in Nyanyanya. What if I kill Dzinganji?"

"I'd be happily amazed. Don't say I didn't warn you."

"I'll never say that," promised Kardios.

This was when Wellman succeeded in completely winning me over. The level of self-awareness that Kardios displays is remarkable, stopping just short of commenting on just how absurd it is that he has yet again run into a so-called god whose villainy demands death at his capable hands. It's a testament to Wellman's skill as a writer that, despite this, the story that follows does not descend into parody; if anything, Kardios's recognition of the situation only serves to make what follows more interesting.

Kardios makes use of the metal basket to reach Flaal, which was "a city, domed and steepled in crystal and gleaming gold and silver. Under the soles of his sandals, the pavement was golden." He had no doubts as to why men were drawn to this place, but it appeared to be completely empty. He called out received "no answer but his own echo." In spite of this, Kardios presses ahead to see what else he might find.

In time, he finds at least one inhabitant of the place.

A superbly proportioned female figure, he saw at once. Her clothing was taut, scanty and many-jeweled. Her pale blonde hair was caught at the temples with a glittering band. Her sandals were cross-gartered in silver to her knees.

"Warm welcome to Flaal, Kardios," said her musical voice. "You're strong and young. You'll be of service to us and your pay princely."

She smiled. Her face was dreamily lovely, her eyes pale blue as the spring sky washed by winter's tears. "My name is Tanda."

Again, the similarities to initial situation in "The Dweller in the Temple" is striking and, in the hands of a lesser writer, would rightly be grounds for criticism, if not outright mockery. Here, it serves to lull the reader into a false sense of déjà vu so that Wellman might catch him off-guard with subsequent revelations – or so it was for me.

Tanda is guarded by two towering warriors clad in golden arm and wielding huge, axe-like weapons. This raises the wanderer's suspicions, all the more so when the woman explains that "Dzinganji created them, to perform his will." When Kardios attempts to press on into Flaal without first agreeing to "make submission" to Dzinganji like all "guests" in the city, the two sentinels attack him. During the battle, he notices that his opponents move strangely and do not seem to bleed when struck. When he emerges victorious, Tanda is unhappy.

"Dzinganji will be displeased," said Tanda in a reproachful voice.

"They were trying to kill me," reminded Kardios, bending above the two silent figures. "Did I truly kill them? Where's the blood?"

There showed only a trickle of clear fluid from the wounds he had inflicted. "It looks more like oil than blood," he said.

"They were machines," said Tanda. "Flaal is guarded by machines."

With that, "The Guest at Dzinganji" takes another unexpected turn and it's not the last. Every step of the way, Wellman zigs rather than zags and the result is a pulp fantasy yarn that is familiar without being hackneyed – and original without straying too far from a tried-and-true formula of the genre. It's good fun and exactly what I want out of stories of this kind.

April 25, 2023

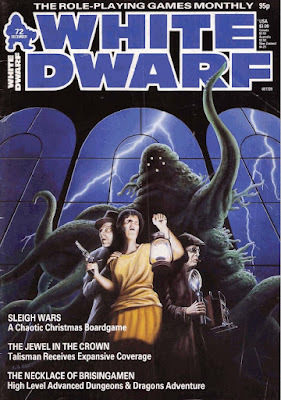

White Dwarf: Issue #72

Issue #72 of White Dwarf (December 1985) features a cover by Lee Gibbons that's striking not just for its style but also its subject matter. Over the course of its run, the subject of most of WD's covers has been fantasy or science fiction, while this one clearly depicts a horror scene, perhaps even one from the Call of Cthulhu game. In any case, I like this cover quite a bit. It's a reminder to me of all the excellent CoC content that appeared in the pages of White Dwarf over the years and kept me reading it for so long.

Issue #72 of White Dwarf (December 1985) features a cover by Lee Gibbons that's striking not just for its style but also its subject matter. Over the course of its run, the subject of most of WD's covers has been fantasy or science fiction, while this one clearly depicts a horror scene, perhaps even one from the Call of Cthulhu game. In any case, I like this cover quite a bit. It's a reminder to me of all the excellent CoC content that appeared in the pages of White Dwarf over the years and kept me reading it for so long."Open Box" kicks off with a review of FASA's Doctor Who Role Playing Game, which the reviewer likes a great deal (8 out of 10). Even more favorably reviewed is Chaosium's Pendragon (9 out of 10) and I find it difficult to argue with such an assessment. The final review is the Pacesetter boardgame, Wabbit Wampage (6 out of 10). I had completely forgotten about the existence of this game, but I now recall seeing many advertisements in Dragon for it (and the Chill-related game, Black Morn Manor) during the mid-1980s. I never played either them, though, from the review, it doesn't seem like I missed much.

I'm going to let Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" pass without comment, because, as is so often the case, none of the books he discusses are ones I've read or about which I have anything to say, good or bad. Far more interesting is Alastair Morrison's "The Jewel in the Crown," which is both an overview of Talisman and an expansion of it. Morrison provides several new spell and adventure cards for use with the game, in addition to a new character – the Samurai. All are given new color cards, complete with (I think) John Blanche illustrations that the reader can either cut out or photocopy from the issue. I've long been a big fan of these kinds of articles. I remember a similar one for Dungeon! that appeared in the first volume of The Best of Dragon of whose rules addition I made use.

"Fear of Flying" by Marcus L. Rowland – there he is again – is a short Call of Cthulhu scenario that takes place aboard a Tarrant Tabor triplane that can carry twelve passengers at a speed of over 100 miles per hour! Naturally, the presence of a carving of Nyarlathotep on board leads to all sorts of Mythos mayhem as the plane makes it way through the air. What makes the scenario memorable is not so much its Lovecraftian elements as its setting, the remarkable aircraft on which the characters are traveling. In my opinion, it's a good use of the 1920s setting, because it highlights the ways that the world of a century ago was both very much like and very much unlike our own. To my mind, that's the best use of any historical seting and one of which I wish we saw more in RPG adventures.

"Scientific Method" by Phil Masters is a brief but interesting look at super-scientists within a superhero setting. What makes the article useful is that Masters looks at both sides of the equation – super-scientist heroes (and sidekicks) as well as villains. Graeme Drysdale's "The Necklace of Brisingamen" is an AD&D scenario for characters of levels 7–10. As its title suggests, it's inspired by Norse mythology, specifically the necklace of the goddess Freya. The adventure concerns a long ago conflict between Freya, Loki, and their followers and how that conflict continues to color contemporary events in and around the village of Stonehelm. This is a lengthy and compelling scenario, one that provides the referee with a lot of material to use, as well as plenty of challenges for the player characters.

"Origin of the PCs" by Peter Tamlyn looks at the virtues and flaws of character generation systems. The article rambles about a number of related topics before coming to the "conclusion" that "character generation is a complex and wide-ranging activity and that different methods will appear best depending on who is using the system, how much time and effort they want and/or need to put into getting results, and what sort of character is to be created." What insight! Much more fun is "Sleigh Wars" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards, a 2–4 player boardgame of "merry Xmas mayhem" in which four "Santas" – Santa Claus himself, Anti-Claus, General Nicholas B. Claus III Jr., and The Ongoing Spirit of Christmas Where It's At At This Moment in Time – compete with another to deliver all their presents before the others. It's a completely ridiculous game, but it looks like fun.

"Recommended Reading" by Marc Gascoigne offers up a couple of new Mythos tomes for use with Call of Cthulhu. "All Part of Life's Rich Pageant," meanwhile, presents a random events table for use with AD&D. The events include such things as "arrested," "conversion attempt," "friendship," and "witness crime," among many others. Each is described, along with ideas on how to implement them in a game. While I could, of course, quibble with some of the entries or with their particular arrangement, it's difficult to find fault with what is essentially an adventure seed generator to aid the referee. As a proponent of the oracular power of dice, I'm largely in favor of tables like this, though one must still be wary of falling prey to randomness fetishism. It's a fine line to walk and each person will draw it in a different place, which is no knock against the general principle.

"Dioramas" is a new series about gaming miniatures by Joe Dever, the first part of which focuses on planning and preparation. Disappointingly, the color photographs that accompany the article aren't of miniature dioramas at all. I hope that future installments might remedy this, since I admire the hard work that goes into the creation of top-notch miniature scenes. The issue also includes more "Thrud the Barbarian," "Gobbledigook," and "The Travellers," the last of which continues its protagonists' playing out of the classic Traveller scenario, Shadows.

As I have written several times previously, this issue is from the period when I was no longer reading White Dwarf regularly but instead only picked up the occasional issue here and there, as I came across them in hobby or book shops. Consequently, my memories of the period are much hazier and I have a lot less affection for these issues. Indeed, it won't be much longer before I'll be in wholly foreign territory: issues I have never seen, let alone read. Once that happens, I'll re-evaluate whether to continue with this series or move on to a different gaming periodical with which I am more familiar, such as Polyhedron.

April 23, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Dweller in the Temple

A frequent counterfactual thought on this blog concerns the state of literary fantasy (broadly defined to include science fiction and horror, among others) had writers like Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft lived beyond the 1930s. I have no firm opinions on the matter, since there are simply too many variables to consider. Indeed, it's quite possible any resulting alternate history in which, for example, REH lived into old age rather than committing suicide in 1936 might nevertheless not be notably different from our own.

A frequent counterfactual thought on this blog concerns the state of literary fantasy (broadly defined to include science fiction and horror, among others) had writers like Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft lived beyond the 1930s. I have no firm opinions on the matter, since there are simply too many variables to consider. Indeed, it's quite possible any resulting alternate history in which, for example, REH lived into old age rather than committing suicide in 1936 might nevertheless not be notably different from our own.

A point in favor of this conclusion is provided by Manly Wade Wellman, who's probably best known among players of Dungeons & Dragons for his stories of Silver John, the wandering Appalachian singer and battler of the occult. Wellman was born in 1903, just three years before Robert E. Howard, and his professional writing career began three years after Howard's own, making them rough contemporaries of one another. Wellman, however, lived a half-century longer than REH and continued to write almost until his death, though his output certainly slowed after the 1960s.

Even so, I'm not sure anyone could argue that Wellman is more well known than Howard (or Lovecraft). This is in spite of the fact that Wellman's work appeared in multiple volumes of Andrew J. Offutt's very influential Swords Against Darkness anthologies published in the late 1970s. (The series is important for the history of D&D because its third volume, which included a yarn by Wellman, was listed in Gary Gygax's Appendix N of "inspirational and educational reading.") If anything, I'd say that Wellman is less well known than either of them, suggesting that long years are no guarantee of greater fame than writers who died comparatively young.

That's too bad, because, in addition to his tales of Silver John the balladeer and occult detective John Thunstone, Wellman also penned six stories about Kardios, a survivor of Atlantis, the last of which was published in 1986, just months after the author's death. Though he first appeared in 1977, Wellman had apparently conceived of Kardios sometime during the 1930s, but had trouble selling him because Robert E. Howard had beaten him to the punch with Kull. However, Andrew Offutt (and, later, Gerald W. Page, Hank Reinhardt, and Jessica Amanda Salmonson) recognized the uniqueness of the character and it's through their efforts that we can read about his exploits today.

"The Dweller in the Temple" quickly demonstrates the uniqueness of Kardios by having the Atlantean do something I cannot imagine Conan or most other mighty-thewed barbarian heroes doing: singing. While traveling along the road alone, he "unslung the harp from behind his broad shoulder and smote the strings. He improvised his own words and melody, while his long sword thumped his leg as though joining in." Kardios' impromptu concert meets with the approval of a dozen or so young men, who "thronged around him, smiling and slapping the hafts of their javelins."

"Three times welcome, my lord," said a spokesman. "We'll escort you to your city."

"City?" echoed Kardios, keeping a hand near his sword hilt. "What city? I didn't even know there was one."

"Just over the hill yonder," said the spokesman, pointing. "Your city of Nyanyanya."

"It must be a fine one for you to name it two or three times," said Kardios. "But I never heard of it until this moment."

"Come and reign there, as was foretold.

Though wary, Kardios acquiesces to their offer, especially after the young men "closed around him like an honor guard ... Those sharp-pointed javelins rode at the ready."

Nyanyanya "was not a large city, but it was beautiful, a grateful refuge for a tired traveler" such as Kardios. He is met there by a crowd of admirers, along with an old man, who identifies himself as Athemar the high priest. Athemar crowns Kardios king by placing a golden circlet on his head, which the wanderer at first takes to be a joke.

"We wouldn't dare joke, Kardios," murmured one of them.

"Never," Athemar assured him. "You see, we have an interesting way of choosing our kings. When one departs, another is mystically brought to us, by decree of the Dweller in the Temple. A committee meets him and brings him to us. It's been like that since Nyanyanya became a city." He stroked his beard. "That was lifetimes ago. But your palace waits for you."

By this point, the Kardios – as well as the reader – is aware that this situation is extremely suspect and indeed probably a trap. Although he recognizes that his life is likely in danger, he does not try to escape. "He would never be happy without knowing the end of this quaint adventure."

Athemar leads Kardios to "a graceful building of the rose-gray stone," where he is shown "a spacious room with a central fountain, chairs and tables and divans, and a red-cushioned throne that seemed chiefly made of emeralds." Before he has a chance to take this all in,

girls entered, spectacularly beautiful girls, gold-haired, jet-haired, jasper-haired, smiling. Their rich, clinging costumes were as brief as the very soul of wit.

"Here are some of your subjects, awaiting your orders," Athemar said to Kardios. "Whatever you may command of them."

The girls all vie for Kardios' attention, encouraged by Athemar, but, taking a page from Conan, he is most interested in a serving girl named Yola, who alone among them seemed genuinely concerned about him. Kardios is correct in this assessment; it is from her that he first learns something of the mysterious Dweller in the Temple about whom the high priest had spoken earlier.

"What's this Dweller in the Temple you worship here in Nyanyanya?"

"Tongbi," she whispered fearfully.

"Tongbi," he repeated the name. "What sort of god is he?"

"A great god. Great and dreadful."

"Why dreadful? Does he kill your people?"

"No." Her hair tossed as she shook her head. "I don't think he ever killed a single citizen of Nyanyanya."

This piques the interest of Kardios, who asks Athemar for more information about Tongbi. The old man is surprised by this.

Athemar frowned. "The girl told you his name?"

"And said that he was powerful, and has never yet killed a citizen of the town. That's to his credit. How ancient a god is this Tongbi, and how is he served?"

A councilor cleared his throat and tweaked his spear-point beard. "You're our king, mighty Kardios," he said. "The king isn't called on to vex himself with religious matters. Athemar and his junior priests do the worshipping and serving of Tongbi."

This is all highly suspicious, of course, and Kardios knows it, but his natural curiosity – and sense of adventure – prevent him from fleeing Nyanyanya. He is determined to get to the bottom of whatever is going on here, as well as the nature of the prophecy that supposedly "foretold" his arrival here.

"The Dweller in the Temple" is a charming, enjoyable romp in the best traditions of pulp fantasy. Kardios handily distinguishes himself from the many rootless, wandering protagonists of the genre, demonstrating not just thoughtfulness – a trait he shares with many others – but also kindness and, above all, humor. Kardios regularly cracks wise and makes light of his circumstances. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he reminds a lot of John the Balladeer, Wellman's more famous creation, right down to his propensity to endear himself to others through song. Also, like the tales of Silver John, this one is written in a light, breezy style that sets it apart from the self-seriousness that too often characterizes fantasies of this kind. If you can find a copy, it's well worth a read.

April 21, 2023

Not Yet Ultimate Campaigns

In yesterday's post, I talked briefly about the concept of an "ultimate campaign," a RPG campaign so good or so exhaustive in its scope and subject matter that it more or less forecloses the possibility of ever again returning to the game and/or game setting with which it was played. I used my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign as an example of an ultimate campaign, but I also referenced the D&D 3e Planescape campaign I played from 2000 to 2004 as another. I could probably add a couple more to the list, like the AD&D 2e Forgotten Realms campaign I refereed throughout the 1990s, but, for the moment, I'm more interested in talking about games and game settings where I have not – yet – experienced an ultimate campaign but would very much like to do so:

Traveller: You'd have thought, given how often I've played this game and how well I know its rules and official setting, I'd have achieved an ultimate campaign by now and yet I have not. The closest I've ever come was, years ago, when I ran The Traveller Adventure to its conclusion. As satisfying as that experience was, it did not prevent my desire to referee (and play in) other Traveller campaigns. I wonder if, given the vastness of subject matter and setting, Traveller might not be susceptible to the creation of an ultimate campaign.Call of Cthulhu: This is another game that I've played extensively over the decades and yet has never yielded an ultimate campaign. This one makes more sense to me, however. Since the game's release, Chaosium has regularly published extensive campaigns for use with CoC. The conclusion of almost any of them could, I would think, result in an ultimate campaign. In my own case, I've never managed to play any of these campaigns to their end, though I have used bits and pieces of them. I don't know if this is a failing unique to me and my gaming groups or if it's a common problem with Call of Cthulhu. Either way, an ultimate CoC campaign remains out of reach.Pendragon: This one is wholly explicable. Since the game's release in 1985, I have participated in three excellent Pendragon campaigns, twice as referee and once as player. In every case, the campaign ended before we reached the end of the death of Arthur, thereby depriving us of proper closure. I hope one day to get a fourth try, because Pendragon really deserves it.Twilight: 2000: I'm currently refereeing a T2K campaign and have hopes that it might become an ultimate campaign. We've only been playing since December 2021, so it's too early to say whether we'll be successful. However, the campaign has good forward momentum, a solid collection of characters, and, perhaps most importantly, a dedicated group of players – all the necessary ingredients for an ultimate campaign. If we can keep this up, who knows where it'll lead?Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of the games appear on my list of Top 10 non-D&D RPGs. They're the roleplaying games about which I think the most and thus about which I have the most flights of fancy regarding potential future campaigns. There are, of course, many other games with which I'd consider myself fortunate to experience an ultimate campaign – RuneQuest comes immediately to mind – but that I don't expect I ever will. At my age – I turn 54 in October – I no longer have an infinity of time to fill with RPGs, so I need to keep my expectations constrained. Mind you, even non-ultimate campaigns are fun, so it's not as if I'll only play a game I think will lead in that direction, though I try to keep my hopes high.How about you? Are there any RPGs whose ultimate campaigns have eluded you? Are there any you'd like to get the chance to experience?

April 20, 2023

The Ultimate Campaign

The longevity of my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign – eight years and counting, as of this post – often raises questions among those who've never participated in a RPG campaign that's lasted that long. One of the most common, believe it or not, is this: when do you think it will end? My answer is always the same, "I have no idea," which is absolutely true. Why that's the case is a topic deserving of its own post (and maybe I'll even write it), but my answer occasions a thought within myself, namely, whenever House of Worms ends, it'll probably be the last time I ever play Empire of the Petal Throne.

Lest anyone get the wrong idea, my thought has nothing to do with the late unpleasantness regarding Tékumel's creator. Rather, I think this way because, whenever and however House of Worms ends, I'm fairly certain that I will have so thoroughly scratched my EPT (and Tékumel) itch that I would find little point in ever returning to it for another campaign. That is, I'll have done everything I'll likely ever want to do with the game and its setting. The conclusion of House of Worms will be – for me anyway – the end of Tékumel as an active RPG setting.

To be clear: I don't see this as a bad thing. Indeed, from my perspective, the idea that I might be "done" with a game or a game setting represents not a lack of interest in them, let alone disappointment or disgust, but rather the opposite: the feeling that I have refereed an "ultimate" campaign. "Ultimate" in this case is simply shorthand for what I already stated above: achieving everything I'll likely ever want to achieve with a given game or game setting. It's the highest compliment I can imagine giving a game or a setting and one I've very rarely bestowed.

Over the years, I've had only a handful of ultimate campaigns, the most recent one prior to House of Worms being early this century, shortly after the release of the Third Edition of Dungeons & Dragons. I refereed a terrific campaign set in the Planescape setting that lasted four years with the same group of five players. At the conclusion of that campaign, I had, in my opinion, so completely made use of the setting, exploring the questions it raised about its idiosyncratic take on AD&D's planar cosmology, not to mention ringing huge changes on it, that I simply cannot conceive of a circumstance where'd want to revisit it, let alone actually do so. What my friends and I did over those four years was, by some definition, perfect and I'd be doing our shared experiences a disservice by going back to it.

I imagine the notion of an "ultimate campaign" might seem strange, even ridiculous, to some readers. One of the promises of the roleplaying medium is that it's infinitely re-usable, which is to say, you can keep playing a given RPG over and over and never exhaust its possibilities. I agree with that and, in fact, consider it one of the greatest virtues of roleplaying games as a form of entertainment. Nevertheless, I also believe that roleplaying can and often does create such singular experiences that they leave those who participate in them unwilling and unable even to contemplate attempting to replicate them. Those experiences engender a recognition that a game or a game setting has now reached its pinnacle for them; it is, for lack of a better word, "done."

Fortunately, there are a more roleplaying games and settings available than any single person could ever use in multiple lifetimes, never mind just one. When House of Worms ends – not if, because nothing lasts forever – that means I'll now have the opportunity to play something else. Whatever it is, I'll make an earnest attempt to play that game through to its end as well, though the likelihood is that I won't quite hit the mark. As I said, ultimate campaigns are few and far between, but I know they exist and I think they are worth aiming for.

April 19, 2023

Arrgh!

From the perspective of the 2020s, it might seem as if the 1970s were another Golden Age of comic books. Certainly, there were a lot of great comic books produced during the decade of my childhood, but it's also the case that the '70s were a period of immense economic decline for comics publishers. Part of the reason that this period might appear, in retrospect, more robust than it actually was is that both DC and Marvel were desperately throwing ideas against the wall in hope that some of them might stick. While some of these attempts were financially successful – Marvel's Conan and Star Wars lines come immediately to mind – most were not.

That's why I'm rarely surprised when I discover the existence of a comic from the 1970s of which I've never heard. Consider, for example, Arrgh!, which ran for five issues between December 1974 and September 1975. Each issue of Arrgh! presented humorous horror stories, often parodies of well-known movies or TV shows. In the case of the penultimate issue of the series, the subject of the parody was none other than my beloved Kolchak: The Night Stalker, here dubbed Karl Coalshaft, "the Night Gawker."

As I said, I had no idea this comic existed until recently, so I never read it. Fortunately, there's an excellent blog devoted to "a historical look at various incarnations of classic TV and movie science fiction/fantasy," Secret Sanctum of Captain Video, that has reproduced the entirety of the Kolchak parody here. The comic's not great literature by any definition, but it made me chuckle a couple of times. Take a look yourself!

As I said, I had no idea this comic existed until recently, so I never read it. Fortunately, there's an excellent blog devoted to "a historical look at various incarnations of classic TV and movie science fiction/fantasy," Secret Sanctum of Captain Video, that has reproduced the entirety of the Kolchak parody here. The comic's not great literature by any definition, but it made me chuckle a couple of times. Take a look yourself!

Retrospective: Shadows

Late last year, I wrote a post in which I enumerated my top 10 classic Traveller adventures, divided into two parts. Both parts were very well received and generated a lot of excellent discussion in the comments, which pleased me. However, reading issue #71 of White Dwarf reminded me just how few of the adventures included in my top 10 have been the subjects of Retrospective posts (only two as it turns out). This post is the first of several intended to correct this oversight on my part.

Late last year, I wrote a post in which I enumerated my top 10 classic Traveller adventures, divided into two parts. Both parts were very well received and generated a lot of excellent discussion in the comments, which pleased me. However, reading issue #71 of White Dwarf reminded me just how few of the adventures included in my top 10 have been the subjects of Retrospective posts (only two as it turns out). This post is the first of several intended to correct this oversight on my part.Shadows is the first part of a "double adventure" released by GDW in 1980. Double adventures were 48-page books consisting of two scenarios printed in a tête-bêche format in imitation of the Ace Doubles published between 1953 and 1973. You can usually gauge a Traveller player's knowledge of the literary history of science fiction by his reaction to the peculiar formatting of the double adventures. Those who look back fondly on the Ace series immediately understood what GDW was doing here, while those without any experience of them were often baffled.

In any case, the other scenario included in this double adventure is Annic Nova, which originally appeared in the first issue of The Journal of the Travellers' Aid Society. To call it a scenario at all is being generous. Even in its slightly expanded and rewritten format, Annic Nova is little more than the description of an odd starship with an accompanying set of deckplans and some unrelated library data. In all the years I've played Traveller, I've never made any use of Annic Nova, so that's all I say on it in this post.

Shadows, on the other hand, is a scenario I've used multiple times to good effect since I first encountered in 1982, as one of the sample adventures included in The Traveller Book. Like many early RPG adventures, Shadows had its origins in a convention tournament, in this case WinterWar 1980, held at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign between January 18 and 20, 1980. Consequently, it includes eight pregenerated characters, as well as a list of available equipment from which to choose before the start of play. It's also largely self-contained in its content and assumptions and playable within a span of two to four hours, depending on the skill and interests of the players.

The basic premise is that, while in orbit around Yorbund, the sensors of the characters' starship detect a strange structure on the planet's surface. The structure appears to be artificial, consisting of three hollow pyramid-like structures. Since there is no record of these structures – Yorbund is largely unexplored, thanks to its insidious, corrosive atmosphere – the characters have an opportunity to be the first people to visit the structure and learn its secrets. When the characters decide to bring their ship in for a closer look, it is fired upon by an energy weapon from the largest pyramid. The ship's computer estimates that, should the ship attempt to leave the area without first disabling the weapon, there is a high likelihood it could be damaged and/or destroyed by subsequent attacks. The characters are thus left with no option but to land and explore the pyramids in hopes of shutting down the weapon.

The initial situation is a bit heavy-handed, but that's the nature of convention scenarios in my experience. At least the characters don't lose their equipment and can undertake their exploration of the pyramids on their own terms. The pyramids themselves are well imagined and described, with plenty of information about their appearance, atmosphere, and lighting, in addition to many maps to aid the referee in his deliberations. The whole place is mysterious and obviously alien. In addition to technological hazards, such as inoperable doors and inexplicable machinery, the place is now home to several species of animals whose presence might hamper progress within. Yorbund is also prone to seismism and unexpected tremors are a further complication with which the characters must deal.

Shadows is sometimes called a "science fiction dungeon" and, on many levels, it's hard to dispute this. Dungeons & Dragons not only invented the concept of roleplaying games, it established the template for RPGs scenarios, regardless of rules system or genre. Many early Traveller adventures are little more than locales without any "plot." The characters are expected to visit some place on an alien world, poke around, and deal with whatever happens as a result – very similar to many dungeons. Shadows is unquestionably in this tradition. Where it differs, in my opinion, is that, unlike many dungeons, there is both an immediate purpose to the characters' exploration – disabling the energy weapon – and a larger mystery to be resolved – the purpose of the structure and its origins.

In my experience of refereeing Shadows, it can be a great deal of fun to play, provided the referee makes a point of emphasizing the creepiness of the environment and the lure of hidden knowledge within. That's why I prefer to call it a haunted house rather than a dungeon. Think the derelict spacecraft in Alien rather than the Caves of Chaos and you're closer to the proper perspective on the scenario, I think. That said, Shadows is still an early RPG adventure, with all that entails, including many details undescribed and left entirely to the referee's own imagination. Whether you see that as a feature or a bug will, I suspect, color your feelings about Shadows. Given that I consider it one of my favorite Traveller adventures, you already know where I stand on this question.

April 18, 2023

White Dwarf: Issue #71

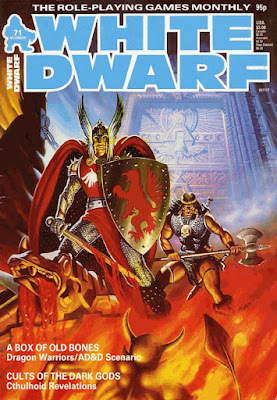

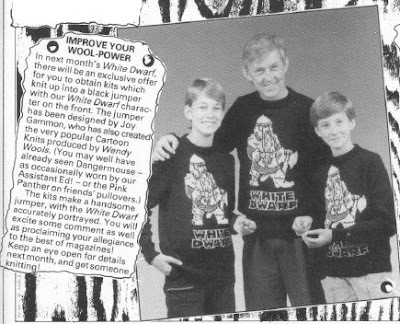

Issue #71 of White Dwarf (November 1985) boasts an eye-catching Alan Craddock cover, featuring a team-up between a heroic knight and a Conan-esque barbarian, as they face off against a demonic horde. Meanwhile, Ian Livingstone's editorial focuses on the expansion of gaming conventions within the UK, which he suggests will result in "gamers up and down the country ... hav[ing] even greater opportunities to participate in their hobby, and meet famous personalities as well as other players." As someone whose own con experiences are quite limited, I'm fascinated by just how important conventions are, not simply to many gamers, but also to the history of the hobby itself. It's a pity I live in a wasteland when it comes to this sort of thing.

Issue #71 of White Dwarf (November 1985) boasts an eye-catching Alan Craddock cover, featuring a team-up between a heroic knight and a Conan-esque barbarian, as they face off against a demonic horde. Meanwhile, Ian Livingstone's editorial focuses on the expansion of gaming conventions within the UK, which he suggests will result in "gamers up and down the country ... hav[ing] even greater opportunities to participate in their hobby, and meet famous personalities as well as other players." As someone whose own con experiences are quite limited, I'm fascinated by just how important conventions are, not simply to many gamers, but also to the history of the hobby itself. It's a pity I live in a wasteland when it comes to this sort of thing.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" kicks off this issue. In addition to his usual reviews of books I've never read and, therefore, don't care about, he spends some time talking about "huge blockbusters arcing down from interliterary space." In reference to Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's Footfall, for example, he elucidates the flaws of blockbuster-style fiction, specifically "momentum takes 100 pages to build, several of the teeming characters are dispensable, and megadeaths are glossed over." These remain issues in this style of popular fiction even today, which is why I prefer short stories over 600-page doorstops.

"Open Box" reviews two gamebooks I've never encountered before: Avenger! and Assassin! (both 8 out of 10). Published by Knight Books, they take place in a world of "Kung Fu meets AD&D," with the viewpoint character being a ninja. The description of the books' unarmed combat system sounds genuinely interesting. Also reviewed is the Paranoia adventure, Vapors Don't Shout Back (7 out of 10), Masks of Nyarlathotep for Call of Cthulhu (9 out of 10), and Thrilling Locations for James Bond 007 (9 out of 10).

"The Face of Chaos" by Peter Vialls is yet another article discussing the contentious topic of alignment in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. I must confess this topic bores me to tears, but, judging by the number of articles written about it over the years, I must be in the minority. In any event, Vialls rehearses all the usual beats – What is alignment anyway? How does Chaos differ from Law? Isn't Neutral a cop-out?, etc. – without offering any answers that are new or interesting. That's no knock against him, of course, just an acknowledgment that, after decades of debate, there's not much insight left to be gleaned, so why not write about something else?

"Not Waving But Drowning" by Dave Lucas presents RuneQuest stats for the fossergrim and nereid. "Cults of the Dark Gods" by A J Bradbury provides historical information on the Assassins and Knights Templar for use with Call of Cthulhu. However, Bradbury doesn't give either group any significant connection to the Mythos, which leaves me wondering about the actual purpose of the article. Fortunately, this month's installment of Thrud the Barbarian leaves no doubt as to its purpose, to wit:

"A Box of Old Bones" by Dave Morris is a low-level adventure written for use with both AD&D and Dragon Warriors. Dual-use scenarios of this sort appeared regularly in the pages of White Dwarf and I have long wondered how often anyone made use of the "lesser" of the two game systems for which it was written. In any case, this scenario is a clever and original one that focuses on the theft of a saint's relics, hence its title. There's no magic or miracles here, only human greed, which I found refreshing – an excellent change of pace adventure.

"A Box of Old Bones" by Dave Morris is a low-level adventure written for use with both AD&D and Dragon Warriors. Dual-use scenarios of this sort appeared regularly in the pages of White Dwarf and I have long wondered how often anyone made use of the "lesser" of the two game systems for which it was written. In any case, this scenario is a clever and original one that focuses on the theft of a saint's relics, hence its title. There's no magic or miracles here, only human greed, which I found refreshing – an excellent change of pace adventure."Avionics Failure" by James Cooke discusses what happens when a Traveller starship suffers damage to its sensors, providing a random failure table to aid the referee in adjudicating the matter. It's not a sexy or groundbreaking article, but it looks useful for ongoing play and that's not nothing. The Travellers comic begins a new storyline, one based on the classic GDW adventure, Shadows. As always, there are lots of fun little bits in the comic. My favorite is the following:

There's yet more Traveller content in this issue, in the form of Marcus L. Rowland's "Tower Trouble." This is a terrific adventure designed for high-skilled criminal characters who are planning a heist on Terra Tower, a beanstalk (as we'd call it today) stretching from Earth's equator to syncrhonous orbit. The scenario is well written, has great maps and referee's advice, and includes pre-generated characters with a lot of individuality. I'm half-tempted to try running sometime as a one-shot, because it looks like fun.

There's yet more Traveller content in this issue, in the form of Marcus L. Rowland's "Tower Trouble." This is a terrific adventure designed for high-skilled criminal characters who are planning a heist on Terra Tower, a beanstalk (as we'd call it today) stretching from Earth's equator to syncrhonous orbit. The scenario is well written, has great maps and referee's advice, and includes pre-generated characters with a lot of individuality. I'm half-tempted to try running sometime as a one-shot, because it looks like fun."Monsters Have Feelings Too Two" by Olive MacDonald is a follow-up to an article originally appearing in issue #38. This time, MacDonald wants to emphasize that intelligent monsters shouldn't be one-trick ponies. They can (and should) be used in a variety of different ways within a campaign. This is why MacDonald uses only a sub-set of the monsters available in any given game he referees, since he finds it more interesting to make those he does use multifaceted. I find this hard to argue with and have long argued that games like D&D probably have too many monsters. "Just Good Fiends" by Ian Marsh looks at a related question: what makes a good monster? While Marsh isn't opposed to the idea of introducing new monsters into a game, he does think that every monster should serve a purpose or fill a niche within a game or campaign setting. This is a solid, thoughtful article on a topic that has long been of interest to me.

"Divine Guidance" presents two new oracular magic items for use with Dungeons & Dragons: the Card of Shukeli and Tellstones. The former is a kind of prophetic Tarot card whose face changes based on the imminent fortune of the person who finds it, while latter are paired stones whose temperatures change based on how close they are to one another ("getting warmer ..."). Joe Dever's "Think Ink," in which he talks about a topic of which I knew nothing: the use of drawing inks to tint painted miniatures. Dever's articles never cease to amaze me with the technical knowledge they impart. It's a reminder (yet again) that I know nothing about miniatures painting. Finally, "Gobbledigook" gets a full page to this month's episode, in which we see graphic evidence that "Goblinz never fight fair!"

April 17, 2023

The Setting of Gamma World (Conclusion)

Having now spent far too much time delving into my collection of Gamma World rulebooks and supplements – and not even having even read them all – I think I'm now in a better position to offer some conclusions regarding its setting. In the interests of clarity and concision, I'll present these as number points.It's often overlooked that Gamma World is a sequel of sorts to James M. Ward's first stab at a post-apocalyptic RPG, 1976's Metamorphosis Alpha. Like its descendant, MA is about mutants in a world gone mad after a civilization-ending disaster. The key difference is that the "world" of Metamorphosis Alpha is an interstellar generation ship launched from Earth in the late 23rd century – a setting that is unmistakably in our future.I mention this because I think it's important to understanding the background to Ward's own conception of the setting of Gamma World, namely that of Metamorphosis Alpha writ large, so as to encompass the entire Earth.However, it's clear that, from a fairly early stage in its development, Gamma World was never the sole product of James M. Ward. At the very least, Gary Jaquet had an influence over its development, as likely did Tom Wham, Timothy Jones, and even Gary Gygax. Each injected their own ideas into the game, diluting Ward's original vision of a high-tech apocalypse occurring several centuries into our future.Consequently, the setting of the 1978 Gamma World rulebook is something of a mishmash, consisting of a strongly high-tech science fictional foundation atop of which were added numerous elements that don't quite comport with it.While the non-Ward elements of Gamma World don't wholly undermine the implication that the setting is a futuristic one, they do muddy the waters quite a bit, thereby lending credence to the common belief that the End comes in the relatively near future rather than the 24th century.There was never a strong editorial hand on the Gamma World game line, especially in its early years. Therefore, each release for the game is sui generis, reflecting the tastes and ideas of the authors who created them. The fact that Ward himself never wrote a single stand-alone scenario for the game line during its first and second editions did little to clarify the situation.Ultimately, there is no single Gamma World setting, however much James M. Ward might have intended otherwise. That said, I personally believe that the game makes the most sense – to the extent that that's even possible – as being set in the aftermath of a future apocalypse. That's certainly the frame I'll use, when I finally get around to starting up a Gamma World campaign. Your mileage may vary.

Having now spent far too much time delving into my collection of Gamma World rulebooks and supplements – and not even having even read them all – I think I'm now in a better position to offer some conclusions regarding its setting. In the interests of clarity and concision, I'll present these as number points.It's often overlooked that Gamma World is a sequel of sorts to James M. Ward's first stab at a post-apocalyptic RPG, 1976's Metamorphosis Alpha. Like its descendant, MA is about mutants in a world gone mad after a civilization-ending disaster. The key difference is that the "world" of Metamorphosis Alpha is an interstellar generation ship launched from Earth in the late 23rd century – a setting that is unmistakably in our future.I mention this because I think it's important to understanding the background to Ward's own conception of the setting of Gamma World, namely that of Metamorphosis Alpha writ large, so as to encompass the entire Earth.However, it's clear that, from a fairly early stage in its development, Gamma World was never the sole product of James M. Ward. At the very least, Gary Jaquet had an influence over its development, as likely did Tom Wham, Timothy Jones, and even Gary Gygax. Each injected their own ideas into the game, diluting Ward's original vision of a high-tech apocalypse occurring several centuries into our future.Consequently, the setting of the 1978 Gamma World rulebook is something of a mishmash, consisting of a strongly high-tech science fictional foundation atop of which were added numerous elements that don't quite comport with it.While the non-Ward elements of Gamma World don't wholly undermine the implication that the setting is a futuristic one, they do muddy the waters quite a bit, thereby lending credence to the common belief that the End comes in the relatively near future rather than the 24th century.There was never a strong editorial hand on the Gamma World game line, especially in its early years. Therefore, each release for the game is sui generis, reflecting the tastes and ideas of the authors who created them. The fact that Ward himself never wrote a single stand-alone scenario for the game line during its first and second editions did little to clarify the situation.Ultimately, there is no single Gamma World setting, however much James M. Ward might have intended otherwise. That said, I personally believe that the game makes the most sense – to the extent that that's even possible – as being set in the aftermath of a future apocalypse. That's certainly the frame I'll use, when I finally get around to starting up a Gamma World campaign. Your mileage may vary.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers