James Maliszewski's Blog, page 79

April 6, 2023

Prelude to the Apocalypse

From the introduction to the first edition of Gamma World (1978), describing the events that laid the groundwork for the destruction of human civilization:

Having conquered the rigors of simple survival, man was able to turn his energies to more esoteric considerations – theology, political ideology, social and cultural identification, and development of self-awareness. These pursuits were not harmful in themselves, but it soon became fashionable to identify with and support various leagues, organizations, and so-called "special interest groups." With the passage of time, nearly all of the groups became polarized, each expressing and impressing its views to a degree that bordered on fanaticism. Demonstrations, protests, and debates became the order of the day. Gradually, enthusiasm changed to mania, then to hatred of those who held opposing views. Outbreaks of violence became more frequent, and terrorists spread their views with guns and bombs.

The Setting of Gamma World (Part II)

The first edition of Gamma World was published in 1978, but did not receive any official support from TSR until 1981, when the company released both the Referee's Screen and Legion of Gold. What makes the former worthy of discussion is its inclusion of an 8-page "mini-module," written by Paul Reiche III and developed by Lawrence Schick. Entitled "The Albuquerque Starport," it offers not really an adventure but the description of three different locales, each of which could serve as the basis for one or more scenarios on their own, or in tandem.

The first edition of Gamma World was published in 1978, but did not receive any official support from TSR until 1981, when the company released both the Referee's Screen and Legion of Gold. What makes the former worthy of discussion is its inclusion of an 8-page "mini-module," written by Paul Reiche III and developed by Lawrence Schick. Entitled "The Albuquerque Starport," it offers not really an adventure but the description of three different locales, each of which could serve as the basis for one or more scenarios on their own, or in tandem.

As its title suggests, "The Albuquerque Starport" takes the futuristic setting of Gamma World as a fact. Indeed, the mini-module places it front and center, since the three locales it describes are the starport itself, a passenger space shuttle, and a space station in orbit above the Earth. All of these locales include details and elements that hit home that GW's apocalypse occurred several hundred years in our future. Indeed, I'll go so far as to say that "The Albuquerque Starport" is the most clearly futuristic of all the products released for the first edition of the game.

That said, the starport section is probably the weakest in this regard, since it is clearly modeled on what commercial airports were like at the time it was written. There is, for example, a restaurant (with cash register), a gift shop, and baggage claim area. However, in many cases, Reiche made an effort to "futurize" what he describes. Thus, the restaurant is "totally automated" and served by robots, as is the kitchen that serves it ("filled with all manner of cooking apparatus, including a quark-powered cooker, a selenium stone, and a maxi-boron boiler."). You'll still find references to "paperback novels" in the gift shop, as well as paper, pencils, and keys – why not staged I.D. devices? – that reflect a 20th century reality, alongside the robots, broadcast power receiving stations, and nervium-12 anti-theft gas.

The description of the shuttle is short, but, by necessity, it demonstrates the high-tech nature of the pre-apocalyptic world. Aboard the vessel, there are "tri-vid amusement games," a null-grav jump shaft instead of an elevator, "acceleration couches," and similar wonders of the Ancients. Like so many things in the mini-module, the shuttle is fully automated, which is convenient, since it means the player characters aren't required to figure out its workings in order to be able to make use of it. That's both a dramatic contrivance and precondition for their reaching the third section of the mini-module, the space station.

The space station is where "The Albuquerque Starport" tells us the most about the setting of Gamma World. The docking pods of the station, whose floors are covered by "bright shag rug[s]," – a concession to the 1970s? – have posters that advertise "the splendors of the cloud cities of Jupiter, the intra-ring pleasure ports of Saturn, and many other famous vacation spots around the solar system." With that, Reiche paints a picture of a solar system-spanning human civilization that I've always found very intriguing.

Shortly thereafter, he describes "matter transmitter pads" that "once transported shuttle passengers to the large outbound starships located farther out in orbit," Star Trek-style. The reference to starships is suggestive, implying that mankind had in fact traveled beyond the aforementioned pleasure ports of Saturn to other star systems. This implication is proven to be correct, when the dreaded Canpous plague is described as "an alien disease brought back to Earth by long-range scoutships in the early 2300's." The star Canopus is more than 300 light years away from our solar system. Even if these long-range scoutships were unmanned, it suggests, at the very least, that, prior to the End, humans were well on their way toward exploring the galaxy.

Finally, the space station section includes "The Moon Survival Store," where "specialized survival gear for travelers going to the moon" can be found – once again implying regular travel beyond the Earth. There are a variety of high-tech pharmaceuticals to be found, in addition to clothing made from "rayon, nylon, dacron, ultron, and other man-made fabrics." None of these things play a significant role aboard the station and are unlikely to be important to the player characters. Nevertheless, they help to paint a picture of a futuristic world – or at least what someone from the late '70s or early '80s might have imagined such a world to look like.

As a kid, I simply adored "The Albuquerque Starport," though I doubt I could have articulated why beyond, "I like spaceships" or something equally banal. Now, as I look at it more critically, I realize that its appeal lies in the way it brings the futuristic elements of Gamma World's setting to the foreground. In addition, it expands that setting beyond Earth and starts my mind wondering, "What happened to Earth's interplanetary settlements and installations? Did they survive the End intact or did they suffer their own catastrophes?" That it does both these things in the span of only six pages of text makes it all the more remarkable.

April 5, 2023

The Setting of Gamma World (Part I)

A little while ago, I wrote a short post about the inspirations of Gamma World. My original purpose was to draw attention to the handful of explicit (primarily literary) inspirations mentioned in the 1978 game's foreword. In doing so, though, I found myself thinking more and more about the seeming disjunction between the way the game presents itself and the way it was viewed by players and referees at the time (and in the years since).

A little while ago, I wrote a short post about the inspirations of Gamma World. My original purpose was to draw attention to the handful of explicit (primarily literary) inspirations mentioned in the 1978 game's foreword. In doing so, though, I found myself thinking more and more about the seeming disjunction between the way the game presents itself and the way it was viewed by players and referees at the time (and in the years since). The first thing that immediately stands out is that the apocalypse of Gamma World occurs in the early 24th century (2322, at least according to the first edition) rather than in the present day or near future. This is the justification for the inclusion of laser weapons and robots and hover cars, for example. I suspect it's also a consequence of the fact that Gamma World's precursor, Metamorphosis Alpha, being set aboard a generation ship, included lots of high technology as well. At the same time, I've come to think that, to the extent it actually has one, James M. Ward's "vision" for Gamma World is closer to Jack Vance's The Dying Earth than The Road Warrior (and not just because the latter postdates the former).

Despite this, Gamma World doesn't always do a very good job of getting point across. Indeed, if you take a look at all the products released for the first edition of the game – the boxed set, the Referee's Screen, Legion of Gold, and Famine in Far-Go – you'll quickly detect a certain schizophrenia about its setting. On the one hand, there are plenty of examples of the science fictional high technology that one would expect for a world several centuries hence. On the other, there are plenty of nods to familiar, 20th century things that, frankly, make little or no sense within that context. This inability to stay consistent about the setting of the game, I think, contributed to many popular misapprehensions about the game.

For the most part, the original Gamma World rulebook knows what it's about and sticks to the idea that the game takes place in the aftermath of a civilization-shattering disaster in the 24th century. There are thus references to robotic farms and spaceports, in addition to the usual wondrous devices of the Ancients, like blasters, powered armor, and energy cells. There's also much talk of robots, cyborgs, androids, and what we would today call artificial intelligences. The picture the rulebook paints is largely one of a futuristic world fallen to barbarism.

I say "largely," because there's a section, at the very end of the book that, in my opinion, weakens the game's commitment to this futuristic world. That section is its "treasure list," consisting of 100 random items the player characters might find among the ruins. These "treasures" are distinct from the weapons, armor, and other devices in that they are usually of much less obvious utility. They're "artifacts of the Ancients" only in the sense that they represent goods and items from the World Before. In most cases, they're little more than curiosities of the past.

In principle, that's a terrific thing. Every human civilization has left behind plenty of artifacts to be found by later ages. Examining these artifacts are part of what enables us to learn about those dead civilizations and so it should be in a post-apocalyptic setting. However, many – in fact, the majority – of the treasures included in this list are items that make little or no sense in the context of a technologically advanced, futuristic society. Worse still, quite a few of them come across as jokey. So, you get things like a pencil sharpener, a slot machine, a cash register, and a cuckoo clock, alongside pewter TSR belt buckle, hand-painted miniature lead figurines, and a rollerball trophy.

What's most striking about these treasures is that, with a handful of exceptions, they're items that only make sense in a 20th century context rather than being products of a more technologically advanced society. Certainly, one can come up with all sorts of explanations/justifications for why they can still be found in the setting, but I can't help feel this was a missed opportunity to introduce some original – and weird – products of the World Before. This feeling isn't lessened by all the little silly and self-referential items, like the belt buckle and miniatures.

These criticisms aside, the Gamma World rulebook otherwise does a good job of sticking to its script. The setting it describes is that of a fallen high-tech civilization and its artifacts reflect this. The end result is a world that is almost as alien to its players as it is to the primitive player characters living in its ruins. Gamma World calls itself a "science fantasy roleplaying game" not so much, I think, because the technology of the Ancients is scientifically implausible, but rather because the Earth its setting is now utterly fantastical, thanks to the effects of the apocalypse that engulfed it.

Retrospective: Unearthed Arcana

Believe it or not, I've never done a formal Retrospective of 1985's Unearthed Arcana. Like me, you might have thought I'd done so, but what you're remembering is an early, rather hyperbolic post entitled "Why Unearthed Arcana Sucked." Since I'm already in the midst of writing several posts that revisit topics I've covered before on this blog, I thought it might be worthwhile to begin by tackling UA, since it's an important book for both the history of AD&D and for the OSR.

Believe it or not, I've never done a formal Retrospective of 1985's Unearthed Arcana. Like me, you might have thought I'd done so, but what you're remembering is an early, rather hyperbolic post entitled "Why Unearthed Arcana Sucked." Since I'm already in the midst of writing several posts that revisit topics I've covered before on this blog, I thought it might be worthwhile to begin by tackling UA, since it's an important book for both the history of AD&D and for the OSR. Re-reading my original 2008 post in preparation for this one, I couldn't help but wince a little. It's not so much that I have changed my mind on most of the topics I addressed in it, but rather that I wouldn't phrase my objections so intemperately. The original post and comments are nevertheless worth reading. They're a useful window into the mindset of the early OSR and the diversity of opinion that existed within it on a whole host of topics. Valuable though that 2008 post is as a historical text, it doesn't represent my considered evaluation of Unearthed Arcana and its place in the history of Dungeons & Dragons (and the hobby more generally).

Before proceeding into the meat of the matter, some background. I was an avid reader and subscriber of Dragon for a five-year period starting in 1982. During that time, one of my favorite recurring columns was Gary Gygax's "From the Sorcerer's Scroll." In those columns, Gygax would often share previews of new rules additions to AD&D, many of which he said would be formally added into the game with the publication of its eventual second edition. I often introduced some of these additions into my ongoing campaign and found I liked some more than others – I generally disliked the new character classes, but I mostly approved of the new spells, for example. This was fine, because none of the options were yet "official" and I could pick and choose which ones to use.

Owing to a number of real world factors – primarily, TSR's financial troubles and Gygax's attempts to save it – plans changed. The additions Gygax originally intended for a new edition of AD&D were all bundled together, along with some additional material, to fill out a new 128-page book called Unearthed Arcana. The book was announced with great fanfare in the pages of Dragon and, of course, I snapped it up as soon as I found a copy at my local B. Dalton. I then spent untold hours poring over it so that I could incorporate its "new discoveries ... [and] a wealth of just uncovered secrets" into my own campaign.

Unfortunately, the book I took home and read that day in 1985 was nowhere near as good as I imagined it would be. To be fair, I'm not sure that it could have ever lived up to my expectations and I suspect that my disappointments then have forever colored my feelings about Unearthed Arcana. Even so, the book presents numerous problems that I do think are worthy of discussion. The most immediate of these is that, as printed, it's riddled with typos, omissions, and outright errors, probably due to the haste with which the book was put together. I still keep a two-page list of additions and corrections to UA that appeared in the November 1985 issue of Dragon inside the front cover of my copy. These problems made using a lot of its contents frustrating and led to numerous misunderstandings.

A much bigger problem is that Unearthed Arcana represents a clear and significant shift in the power level of AD&D characters. Both the barbarian and cavalier classes, for example, are very potent, with a wide range of abilities. Many of the new demihuman races are similarly more powerful, particularly in light of the wider range of classes available and levels attainable by non-human characters. Combined with weapons specialization (for fighters and rangers), mightier magic items, and greater flexibility for spellcasters (thanks to cantrips and new spells), the overall effect of Unearthed Arcana is to push AD&D in a direction that's generally higher-powered.

Now, many players might not mind this and I don't think there's necessarily anything wrong with this approach. However, I think I'm correct in saying that the direction UA heralded was a clear change from the earlier presentation of AD&D. Gygax states in his preface to the book that "the AD&D® game system is dynamic. It grows and changes and expands." That's a fair point. I have no doubt that, for many who had been playing AD&D since its completion in 1979, welcomed the growth and changes Unearthed Arcana brought with it. For me, then and now, it was a step too far, evidence that, after a certain point, you can change a thing too much for it to remain the thing it once was.

In retrospect, it seems odd that I should feel this way about UA. As I explained at the beginning of this post, I loved Gary Gygax's columns in Dragon, even the ones whose content I didn't use in my own campaign. Individually, they possessed a freshness that was very appealing. They suggested that AD&D still had new horizons to cross, new frontiers to explore. When assembled together, all the little additions Gygax had released piecemeal over the years now seemed to lack that freshness that had once appealed to me. They seemed not merely stale but ponderous and even restrictive. It's difficult to explain, but, somehow, the transformation of Gygax's proposals into "official" rules laid down in a hardcover book had robbed them of the fun and vibrancy they once possessed in my mind.

As I flip through Unearthed Arcana today, I find it difficult to dislike most of its contents. Taken individually, like the original articles in which they appeared, most of them are fine as optional additions or expansions of the AD&D rules. I can easily imagine using many of the spells or magic items, for instance, and I still think the thief-acrobat is a fun addition for certain kinds of campaigns. As a whole, though, UA remains disappointing to me and I'd never use all of its contents. Perhaps if Gygax had had more time to develop them, I might feel differently, but, as it is, Unearthed Arcana is the book that started to shake my confidence in Gygax, TSR, and D&D itself – which goes some way to explain why I've often been so immoderate in expressing my negative opinion of it.

April 4, 2023

You're Next, Punk!

White Dwarf: Issue #70

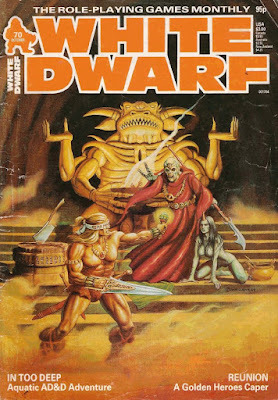

Issue #70 of White Dwarf (October 1985) has a very striking cover by Brian Williams. Though the idol in the back recalls gaming's best cover ever, I find myself drawn to the blindfolded barbarian in the foreground. Why is he blindfolded? What is the significance of the runes written on that blindfold? What is that glowing device in his left hand? It's a very evocative piece and all these unanswered questions only makes it more compelling.

Issue #70 of White Dwarf (October 1985) has a very striking cover by Brian Williams. Though the idol in the back recalls gaming's best cover ever, I find myself drawn to the blindfolded barbarian in the foreground. Why is he blindfolded? What is the significance of the runes written on that blindfold? What is that glowing device in his left hand? It's a very evocative piece and all these unanswered questions only makes it more compelling.Ian Livingstone's editorial mourns the loss of Imagine magazine, which ceased publication with its thirtieth issue. His words seem genuinely heartfelt, especially when he notes "the good relationship between the White Dwarf staff and their opposite numbers." At the same time, Livingstone uses this occasion to downplay any suggestion that there is a decline in interest in the hobby of roleplaying. He likewise crows that "White Dwarf's circulation continues to increase," which, while undoubtedly true, seems – to me anyway – to be in slightly poor taste, given the circumstances.

"Tongue Tied" by Graeme Davis deals with the questions of languages and literacy in AD&D. Davis offers a simple but "realistic" system for handling fluency and the learning of new tongues. It's probably more than is needed by most players of AD&D, but it looks to do a good job at emulating "the polyglot flavour of Howard's Hyborian Age or Moorcock's Young Kingdoms." I may look at it more closely as I ponder similar issues in The Secrets of sha-Arthan .

As usual, we get new installments of "Thrud the Barbarian," "Gobbledigook," and "The Travellers." The latter concludes its series of presenting Traveller statistics for the comic's many characters by giving us a look at "the galaxy's most repugnant pervoid," Jason Dinalt – no, not that one – and Felix the Dawlri, an "albino koala bear/tribble." We also get several superhero-related features, starting with Paul Ryder's "The Coven," a cabal of villainous magicians for use with Golden Heroes. There's also "Reunion" by Simon Burley, an adventure dual statted for both Golden Heroes and Champions. The scenario is a follow-up to the introductory one included with Golden Heroes, so I suspect it would hold much less appeal to a Champions referee (unless he happens to own GH as well).

"Open Box" looks at a lot of D&D-related items, starting with three Expert-level modules: Quagmire!, The War Rafts of Kron, and Drums on Fire Mountain, all of which receive scores of 8 out of 10. Dragons of Mystery for the Dragolance series does not fare nearly as well, receiving only 6 out of 10, which is frankly a much higher score than its text would suggest. The reviewer says that "its actual use and value is questionable" along with many other harsh truths. Battle System , meanwhile, gets a better hearing (8 out of 10). I was surprised by this, given that Battle System was something of a rival to GW's own Warhammer rules. Finally, there's The Lost Shrine of Khasar-Khan, the second entry in "The Complete Dungeon Master" series (8 out of 10).

"The Price is Right" by Marcus Rowland is a follow-up of sorts to last month's "The Surrey Enigma." The article describes in full the pre-decimal UK monetary system, along with a price list of common items. I'm a sucker for articles like this, so I found it quite useful. Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" is here once more and, as usual, I couldn't muster the interest to do more than skim its three columns. Oh well. "Dead or Alive" by Diane and Richard John presents a new career for Traveller: the bounty hunter. Along with the usual information on terms of service and skills, there's also a nice variant of the classic type-S scout ship – with deckplans!

The third part of Peter Blanchard's "Beneath the Waves" series focuses on "creatures from the depths." This includes not just the usual underwater menaces, like cephalopods and sharks, but also sentient species, such as aquatic elves, mermen, and sahuagin. As with earlier installments, this is a solid article but much too short; it only scratches the surface of its subject. "In Too Deep," also by Blanchard, is an AD&D adventure for 4th–5th level characters. The scenario concerns a maritime expedition for spices, the politics of the merchants guild, renegade mermen, and other submarine shenanigans. There are plenty of twists and turns in the adventure and I think it does an effective job of showing how to integrate underwater threats into an AD&D campaign.

"Monstrous NPCs" by Paul Ormston offers up three fully fleshed-out monster NPCs, each a unique individual with his own personality, history, and goals. There's a lizard man prince, a jovial stone giant, and an intellect devourer masquerading as a human. Though each description is short, they're all interesting. They also nicely demonstrate that even monsters can benefit from characterization. "Chop and Change" is Joe Dever's article on modifying miniature figures by adding or subtracting elements from the original molds. He includes several photos of conversion techniques in action, including one of a dinosaur playing a saxophone that I found rather amusing for some reason.

All in all, I mostly enjoyed reading this issue of White Dwarf, though I continue to see signs that the magazine is in the midst of its transformation into the Games Workshop house organ it will one day become.

All in all, I mostly enjoyed reading this issue of White Dwarf, though I continue to see signs that the magazine is in the midst of its transformation into the Games Workshop house organ it will one day become.

April 3, 2023

Armor as Damage Reduction

One of the first blogposts of the OSR that I remember being widely celebrated and discussed was "Shields Shall Be Splintered!" by Trollsmyth. If you've somehow never read it before, take a moment to follow the link and do so. The post isn't long and the idea behind it is a simple but clever one.

One of the first blogposts of the OSR that I remember being widely celebrated and discussed was "Shields Shall Be Splintered!" by Trollsmyth. If you've somehow never read it before, take a moment to follow the link and do so. The post isn't long and the idea behind it is a simple but clever one.

I found myself thinking about Trollsmyth's post again recently, as I was re-reading a section of Unearthed Arcana that I rarely see discussed. In the Dungeon Masters' Section of the book, you'll find descriptions of new armor types. Among these are field plate armor and full plate armor, which, in addition to filling out the AD&D armor class table all the way to AC 0, introduce two new mechanics into the game that, so far as I recall, doesn't exist anywhere else: armor as damage reduction and damage to armor.

Here's how those mechanics are described in the description of field plate:

For every die of damage that would be inflicted upon the wearer from any attack, physical or magical, the armor will absorb 1 point of the damage. (On a damage roll of 1, the wearer would take no damage.) For example, the armor will absorb 1 point of damage from the strike of a long sword, and the damage from an ice storm (3–30, or 3d10) would be reduced by 3 points, and the damage from the breath weapon of a 9 HD dragon is reduced by 9 points. However, after the armor absorbs 12 points of damage in this fashion, it is damaged and must be repaired. Until repairs are made, it cannot absorb further damage and is considered one armor class worse in protective power. Damaged field plate may be repaired by a trainer armor [sic] at a rate of 100 gp per point of absorbing power restored, and one day of time per point restored.

Full plate armor functions more or less identically, though its absorption is 2 points per die of damage and it has a total absorption capacity of 26 points before it needs repair.

A couple of thoughts occurred to me as I re-read this section. Firstly, I had apparently forgotten the rules associated with these new armor types. I suspect that's because, like so many things that later appeared in Unearthed Arcana, I remember more strongly the original appearance of field and full plate in Gygax's "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" column in issue #72 of Dragon. Unless my recollection is gravely in error, those new types of armor did not provide any reduction to the damage inflicted on their wearers. Instead, they were simply better types of plate with accordingly better AC ratings. Damage reduction/absorption is thus something new to UA (though, as always, I am happy to be corrected on this point).

Secondly, I had long understood the rating of a type of armor in AD&D (and D&D, for that matter) to represent how difficult it was to damage its wearer. Characters with lower AC ratings were not "harder to hit," but harder to damage. I know that D&D often speaks of a "to hit" roll, but I take that to be shorthand for "to hit in a way that results in damage." If so, does an additional layer of damage absorption make any sense? Does this addition to the way hits and damage work in AD&D do violence to the combat rules or only to my peculiar interpretation of what hit and damage rolls represent in AD&D?

Armor as damage reduction isn't a new idea. Many RPGs that followed in D&D's wake – RuneQuest being one of the best examples – view armor in this fashion. However, those games broadly divorce the difficulty of striking an opponent in combat from the armor that they wear. D&D has always been a bit more vague on this subject, partly in the interests of efficiency. Whatever else you might say about D&D combat, it's fast. D&D has always sacrificed "realism" for speed of play, which I think is the right call in most cases. That's why I find the damage absorption rules for field and full plate rather odd. To my mind, they don't fit with the overall philosophy of D&D combat.

Of course, re-reading this section of Unearthed Arcana also made me wonder if Gygax's thinking had changed on the matter of armor and/or combat. If so, what might we have seen in his version of Second Edition? Might we have seen a broader implementation of damage reduction in the game? It's a question with no definitive answer, but it's fun to ponder nonetheless.

Starfield

The influence of Dungeons & Dragons on popular culture is immense and incontrovertible, with D&D-derived ideas and terminology spreading far and wide. This is particularly true of video and computer games, whose designers long ago looked to D&D for inspiration for both concepts and game mechanics. Consider, for example, how many such games include character classes, hit points, and experience points, just to cite three obvious examples of what I'm talking about.

The influence of Dungeons & Dragons on popular culture is immense and incontrovertible, with D&D-derived ideas and terminology spreading far and wide. This is particularly true of video and computer games, whose designers long ago looked to D&D for inspiration for both concepts and game mechanics. Consider, for example, how many such games include character classes, hit points, and experience points, just to cite three obvious examples of what I'm talking about.It's much rarer to see the influence of other roleplaying games in the wider culture, even within nerdy domains like video games. Examples exist, of course – I believe the Fallout series has some connection to GURPS? – but they're comparatively rare. That's why I was quite surprised to discover that Bethesda Game Studio's upcoming science fiction roleplaying game, Starfield, is inspired by GDW's Ttraveller.

I'm no longer a huge player of video or computer games, but this news certainly has piqued my interest. I played the first Paragon Traveller computer game in the early 1990s and enjoyed it well enough for what it was, but, in the years since, I can't recall any SF video games that showed much similarity to Traveller, either in concept or in game mechanics. If Starfield turns out to be such a game, I'll certainly take notice. The game won't be released until September, so I'll have to wait and see how things unfold.

April 2, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Tomb-Spawn

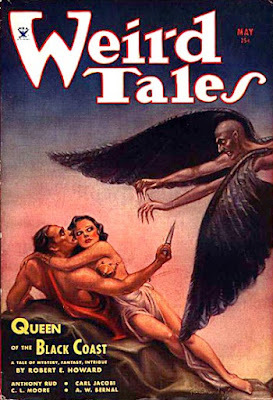

If the May 1934 issue of Weird Tales looks familiar, it should. That's because it may well be one of the most famous in the entire run of the Unique Magazine: the first cover appearance by Robert E. Howard's Conan the Cimmerian, courtesy of Margaret Brundage. Of course, the issue in question featured more than "Queen of the Black Coast," justly famous though that tale is. Also to be found in its pages is Clark Ashton Smith's "The Tomb-Spawn," a short but nevertheless satisfying story set in Zothique.

If the May 1934 issue of Weird Tales looks familiar, it should. That's because it may well be one of the most famous in the entire run of the Unique Magazine: the first cover appearance by Robert E. Howard's Conan the Cimmerian, courtesy of Margaret Brundage. Of course, the issue in question featured more than "Queen of the Black Coast," justly famous though that tale is. Also to be found in its pages is Clark Ashton Smith's "The Tomb-Spawn," a short but nevertheless satisfying story set in Zothique."The Tomb-Spawn" introduces two brothers, Milab and Marabac, who are jewel merchants from Ustaim. They had traveled by caravan to far-off Faraad, in search of goods to take home with them for sale. While relaxing with other foreign merchants in one of Faraad's wine shops, they listened intently to a local storyteller. He regaled them with the legend of the wizard-king Ossaru, who "once ruled over half the continent of Zothique."

According to these legends, Ossaru was "half immortal" and favored by "Thasaidon, black god of evil." Even more significantly, Ossaru "was companioned by the monster Nioth Korghai, who came down to Earth from an alien world, riding a fire-maned comet."

"Ossaru, by his skill in astrology, had foreseen the coming of Nioth Korghai. Alone, he went forth into the desert to await the monster. in many lands people saw the falling of the comet, like a sun that came down by night upon the waste; but only King Ossaru beheld the arrival of Nioth Korghai. He returned in the black, moonless hours before dawn when all men slept, bringing the strange monster to his palace, and housing him in a vault beneath the throne-room, which he had prepared for Nioth Korghai's abode.

"Dwelling always thereafter in the vault, the monster remained unknown and unbeheld. It was said that he gave advice to Ossaru, and instructed him in the lore of the outer planets. At certain periods of the stars, women and young warriors were sent down as a sacrifice to Nioth Korghai; and these returned never to give account of that which they had seen. None could surmise his aspect; but all who entered the palace heard ever in the vault beneath a muffled noise as of slow beaten drums, and a regurgitation such as would be made by an underground fountain; and sometimes men heard an evil cackling as of a mad cockatrice.

In time, the monster "sickened with a strange malady" and died. Ossaru then surrounded the body of Nioth Korghai "with a double zone of enchantment, circle by circle" within the vault where had dwelled. Later, when Ossaru himself died, his remains, too, were placed within the same vault, beside the alien beast that had served him.

The legend does not end there, however. According to the storyteller,

No man has ever found their tomb; but the wizard Namirrha, prophesying darkly, foretold many ages ago that certain travelers, passing through the desert, would some day come upon it unaware. And he said that these travelers, descending into the tomb by another way than the door, would behold a strange prodigy. And he spoke not concerning the nature of the prodigy, but said only that Nioth Korghai, being a creature from some far world, was obedient to alien laws in death as in life. And of that which Namirrha meant, no man has yet guessed the secret."

Milab and Marabac then set off from Faraad toward Ustaim, traveling once more by caravan in the company of other merchants. Unfortunately for them, their caravan is ambushed by a horde of the "wild and half-bestial" Ghorii: " Akin to the ghouls and jackals, they were eaters of carrion; and also they were anthropophagi, subsisting by preference on the bodies of travelers, and drinking their blood in lieu of water or wine." The Ghorii quickly kill the brothers' companions and would have killed them as well, had the camels they were riding not been so frightened that they bolted away from the scene of the ambush.

As their camels flee in unexpected direction, Milab and Marabac spy "the white walls and domes of some inappelable city" that appears to be much closer than it actually was. By the time they finally reach it, a couple of days later, they are in need of food and water. Desperate, they enter the heart of this once-great metropolis, looking for a possible source of refreshment.

Wandering hopelessly on, they came to the ruins of a huge edifice which, it appeared, had been the palace of some forgotten monarch. The mighty walls, defying the erosion of ages, were still extant. The portals, guarded on either hand by green brazen images of mythic heroes, still frowned with unbroken arches. Mounting the marble steps, the jewelers entered a vast, roofless hall where cyclopean columns towered as if to bear up the desert sky.

The broad pavement flags were mounded with debris of arches and architraves and pilasters. At the hall's far extreme there was a dais of black-veined marble on which, presumably, a royal throne had once reared. Nearing the dais, Milab and Marabac both heard a low and indistinct gurgling as of some hidden stream or fountain, that appeared to rise from underground depths below the palace pavement.

Eagerly trying to locate the source of the sound, they climbed the dais. Here a huge block had fallen from the wall above, perhaps recently and the marble had cracked beneath its weight, and a portion of the dais had broken through into some underlying vault, leaving a dark and jagged aperture. It was from this opening that the water-like regurgitation rose, incessant and regular as the beating of a pulse.

If I have a complaint about "The Tomb-Spawn," it is the lack of subtlety Smith displays in setting up the situation in which Milab and Marabac find themselves. I wish that he had somehow been able to present the legend of Ossaru in such a way that its eventual discovery by the brothers did not seem so obvious. He makes some effort at justifying the course of the tale through Namirrha's prophecy, but that is, in my opinion, a weak, even lazy, artifice on his part.

Fortunately, Smith outdoes himself when it comes to the conclusion of "The Tomb-Spawn." What the brothers find in the vault beneath the dais is delightfully frightful and more than worth the wait. I don't wish to oversell it, but I believe it's one of Smith's creepier creations. Take the time to follow the link at the start of this post and read the tale – as I said, it's not very long – to see if you agree.

April 1, 2023

A Grognardia Shout-Out

There's apparently a D&D movie in the theaters, something of which I was dimly aware but never took much serious interest in, for reasons I've elucidated in the past. Consequently, I haven't paid attention to the commentary surrounding it and thus would have completely missed out on Ed Park's review/meditation on "the magic and melancholy of Dungeons & Dragons" had it not been pointed out to me. Park's article has much to recommend it. For my present purposes, though, its main virtue is its reference (and link) to this blog in its third paragraph.

As worldly fame goes, it's not much, but, right now, I'll take it.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers