James Maliszewski's Blog, page 82

February 26, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Gallery: Hiero's Journey

Since this will likely be the last Pulp Fantasy Gallery post for a while, I thought I'd change things up a bit and go for something a little different this week. Sterling Lanier's 1973 novel, Hiero's Journey, is a work of post-apocalyptic science fantasy of which I am very fond. It also enjoys the unique distinction of being mentioned by name in both Gary Gygax's Appendix N and Tom Wham and Timothy Jones's foreword to the first edition of Gamma World.

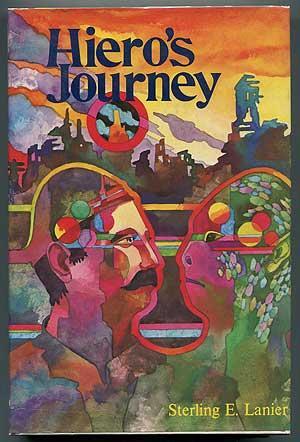

While I'll have a lot more to say about Gamma World over the course of the next week or so, right now I want to focus only on the cover illustrations to Hiero's Journey. Here's the original one, from a hardcover published by Chilton with artwork by Jack Freas. The cover would be re-used for a 1975 hardcover from Sidgwick & Jackson.

The following year, Bantam released a paperback edition as part of its "Frederik Pohl Selection" series. The cover artist is unknown.

The following year, Bantam released a paperback edition as part of its "Frederik Pohl Selection" series. The cover artist is unknown.

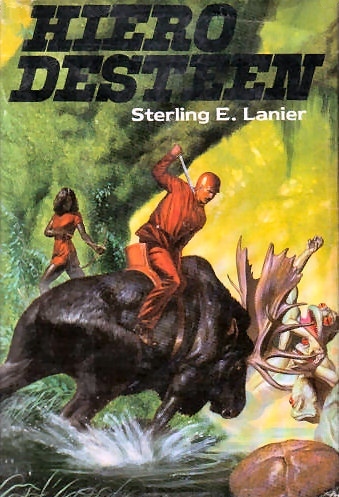

1976 saw the arrival of yet another paperback, this time from Panther, with art by Gino D'Achille. This is the first cover that clearly depicts something from the novel. Note, too, the cover blurb invoking The Lord of the Rings, which, by this time, had become the gold standard for the broader "fantasy" genre.

1976 saw the arrival of yet another paperback, this time from Panther, with art by Gino D'Achille. This is the first cover that clearly depicts something from the novel. Note, too, the cover blurb invoking The Lord of the Rings, which, by this time, had become the gold standard for the broader "fantasy" genre.

Del Rey/Ballantine's 1983 edition is the one I owned as a kid. The cover is especially memorable to me, thanks to the artwork of Darrell K. Sweet. This cover would be re-used several times over the course of the next decade.

Del Rey/Ballantine's 1983 edition is the one I owned as a kid. The cover is especially memorable to me, thanks to the artwork of Darrell K. Sweet. This cover would be re-used several times over the course of the next decade.

Thanks to the Science Fiction Book Club, the novel gets a new cover by Kevin Johnson in 1984.

Thanks to the Science Fiction Book Club, the novel gets a new cover by Kevin Johnson in 1984.

A new Panther edition appeared in 1985, with yet another cover by Gino D'Achille, making him the only artist to illustrate the novel twice. Interestingly, his second cover looks to be a variation on the scene depicted on the 1976 edition.

A new Panther edition appeared in 1985, with yet another cover by Gino D'Achille, making him the only artist to illustrate the novel twice. Interestingly, his second cover looks to be a variation on the scene depicted on the 1976 edition.

February 25, 2023

Battleground

Though I am fairly certain I'd seen this before – indeed I had to check the archive of this blog to be sure I'd not posted on it long ago – a close friend of mine recently pointed me toward this series of videos that present episodes from the 1978 UK television program, Battleground. Each episode focuses on a different battle, such as the Battle of Edgehill from the English Civil War, the Battle of Waterloo from the Napoleonic Wars, or the Battle of Gettysburg from the US Civil War, and then shows a tabletop miniatures version of that battle as played out by two opponents.

Though I am fairly certain I'd seen this before – indeed I had to check the archive of this blog to be sure I'd not posted on it long ago – a close friend of mine recently pointed me toward this series of videos that present episodes from the 1978 UK television program, Battleground. Each episode focuses on a different battle, such as the Battle of Edgehill from the English Civil War, the Battle of Waterloo from the Napoleonic Wars, or the Battle of Gettysburg from the US Civil War, and then shows a tabletop miniatures version of that battle as played out by two opponents.The episodes are weirdly engrossing, particularly to someone such as myself, whose direct experience of miniatures wargaming is very limited. They all include a historical overview of the battle in question by the show's presenter, Ed Woodward, followed by the wargame proper. Though the quality of the posted videos is not high, you can nevertheless appreciate how much work went into the terrain and the miniatures used in them. Frankly, watching videos like this makes me wish I had the time, space, and money to devote myself to the hobby, because it looks like a lot of fun.

Anyway, take a look at Woodward's introduction to the series. It's short, very charming, and gives a good sense of the general tenor of the entire series. If you like it, you can then watch whole episodes, using the link above.

February 23, 2023

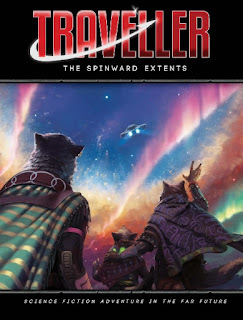

REVIEW: The Spinward Extents

When it comes to Traveller, my preference these days is for what has come to be called "classic" Traveller – GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future as published between the years 1977 and 1986. This is the period during which I first became acquainted with the game, so my preference is at least partly born out of nostalgia for those heady days of my youth. At the same time, I also have a genuine philosophical preference for the earliest iteration of Traveller, as I think it's the most elegant and easy-to-use of all editions of the game. Like OD&D, which preceded it by only three years, I find classic Traveller a great foundation on which to build freewheeling and enjoyable SF RPG campaigns.

When it comes to Traveller, my preference these days is for what has come to be called "classic" Traveller – GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future as published between the years 1977 and 1986. This is the period during which I first became acquainted with the game, so my preference is at least partly born out of nostalgia for those heady days of my youth. At the same time, I also have a genuine philosophical preference for the earliest iteration of Traveller, as I think it's the most elegant and easy-to-use of all editions of the game. Like OD&D, which preceded it by only three years, I find classic Traveller a great foundation on which to build freewheeling and enjoyable SF RPG campaigns.Because classic Traveller is no longer in print – though you can purchase PDFs (and some POD books) of its entire run through DriveThruRPG – it's not necessarily the best choice for enticing newcomers to take a look at the game. Fortunately, Mongoose Publishing has been producing a new, very playable edition of Traveller since 2008. Though it's not my preferred version, I nevertheless enjoy it and am, in fact, currently playing in a campaign that uses its rules. Currently in its second, revised edition, Mongoose Traveller (as it is sometimes known) is probably the best edition and most accessible version of the game since classic, thanks in no small part to its continued support in the form of supplements and adventures.

One of its most recent supplements is The Spinward Extents , a massive, 368-page hardcover book devoted to describing the disputed border region between the Third Imperium, the Zhodani Consulate, the Aslan Hierate and the Vargr. Given my avowed love of frontiers, this is like catnip to me. The fact that the tome also updates and expands upon the old Paranoia Press sectors, the Beyond and the Vanguard Reaches, only added to its appeal. The Paranoia Press sectors long had a reputation among Traveller fans for being a bit wilder and woollier than the more sober and even staid tone of GDW's own pre-generated sectors. I was thus intensely curious to see what Mongoose had decided to do with them, hoping that they might find a way to keep the reckless inventiveness of the original material while squaring it better with the overall tenor of the Third Imperium setting.I am very pleased to say that my hopes were largely fulfilled. Though not without flaws, The Spinward Extents is a fine supplement, providing the referee everything he needs in order to run many adventures and indeed entire campaigns in the Beyond and Vanguard Reaches sectors. Before discussing the meat of the book itself, I'd like to write briefly about its physical qualities. As I already noted, the book is big, perhaps a little too big in my opinion. The book's size makes it a little unwieldy as a reference book, particularly given that its index cursory and its table of contents non-existent. This makes finding specific information within its nearly-400 pages difficult at times, though not impossibly so.

The Spinward Extents is full-color throughout, in very stark contrast to the restrained, mostly black and white interiors of classic Traveller materials. That said, the layout is clean and legible. Illustrations of varying quality abound, most of them depicting sophonts, planetscapes, and new starships. Each of these starships also gets deckplans, which are generally serviceable, though rarely as attractive as those of GDW's heyday. The same is true of the sector and subsector maps, which are much "busier" than I'd prefer. Speaking of which, the book also includes two poster-sized maps of the Beyond and the Vanguard Reaches. Despite my qualms about the esthetics of their presentation, they do a very good job of providing a macro-view of the region's sectors.

As one might expect, the book is divided roughly into two parts, with each half devoted to one sector. Each half uses a similar format, starting with a brief introduction, followed by a historical timeline of important events, and then descriptions of the major interstellar states within the sector. One of the main attractions of a region of space like this is its political diversity (and instability) compared to the sclerotic Imperium. Many government descriptions also include starship designs unique to their forces, along with game stats and the aforementioned illustrations and deckplans. Non-governmental organizations (and their starships and special equipment) also receive descriptions, as do non-human sophonts.

Each of the sectors' sixteen subsectors gets several pages devoted to it, starting with an overview and a listing of its Universal World Profiles, the string of letters and numbers that describe a star system's primary inhabited body (planet or asteroid belt). Between three and six worlds are singled out for additional detail, in order to give some sense of the flavor of each subsector. In some cases, a world description might include additional game-related material, like a mapped location, an animal native to it, or yet more unique starships – there are a lot of new starships in this book. The material in the subsector write-ups forms the bulk of The Spinward Extents and is quite varied, giving players and referees alike plenty of ideas for characters and scenarios. All in all, it's reasonably well done.

As I said earlier in this review, my hopes were The Spinward Extents were largely fulfilled and that's no mean feat. I am a diehard Traveller fan of long standing, who knows the Third Imperium setting like the back of my hand. I am thus the proverbial tough audience for products like this and my complaints are mostly quibbles about esthetic choices. Reading this book left me wanting to start a campaign in this region of space, since it offered me plenty of little seeds that I could easily imagine flowering into exciting science fiction adventures. Even more, I found myself interested in Mongoose's other supplements, something I never expected to happen. In the end, I suppose that's the highest recommendation of all.

Gary Gygax on the BBC

A Complete Timeline of Early D&D Scenarios

Over at his blog, Explore: Beneath & Beyond, Joe Nuttall has put together an excellent series of posts in which he presents a complete timeline early D&D scenarios from 1971(!) to 1979. If you're at all interested in the early history of the hobby, I highly recommend that you take a look at them, along with Joe's other content.

Be warned: time flies while reading these posts! I must confess I lost a couple of hours while I was reading and re-reading their details. Good stuff!

Gygax vs Gygax

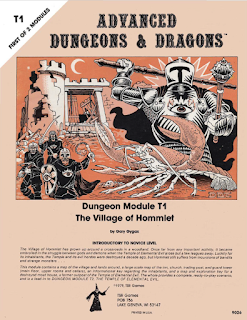

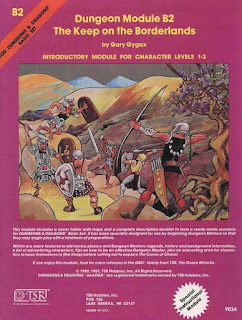

Earlier this year, I commented on the fact that most of Gary Gygax's published D&D modules were aimed at the higher levels of play. Yet, he also wrote two adventures geared toward beginning-level characters that are widely recognized as absolute classics, The Village of Hommlet and The Keep on the Borderlands. Indeed, they're among the most well known Dungeons & Dragons adventures ever published and, even now, exercise considerable influence over how both game designers and game players conceive of a beginner's adventure.

Earlier this year, I commented on the fact that most of Gary Gygax's published D&D modules were aimed at the higher levels of play. Yet, he also wrote two adventures geared toward beginning-level characters that are widely recognized as absolute classics, The Village of Hommlet and The Keep on the Borderlands. Indeed, they're among the most well known Dungeons & Dragons adventures ever published and, even now, exercise considerable influence over how both game designers and game players conceive of a beginner's adventure.As one might imagine, there are a number of similarities between the two adventures, starting with the fact that they both first appeared in 1979. In addition, each proclaims itself to be an "introductory" module. Further, their basic scenarios are very much alike: the titular isolated community is menaced by the lurking threats of Chaos and Evil and it is up to the newly arrived player characters to investigate and, if possible, stem their growing tide. In prose to rival his description of the Drow city of Erelhei-Cinlu, Gygax explains the broad situation thusly in The Keep on the Borderlands:

The Realm of mankind is narrow and constricted. Always the forces of Chaos press upon its borders, seeking to enslave its populace, rape its riches, and steal its treasures. If it were not for a stout few, many in the Realm would indeed fall prey to the evil which surrounds them. Yet, there are always certain exceptional members of humanity, as well as similar individuals among its allies – dwarves, elves, and halflings – who rise above the common level and join battle to stave off the darkness which would otherwise overwhelm the land.Truly evocative stuff in my opinion, providing some insight into how Gygax conceived of the "world" of Dungeons & Dragons and the role of adventurers within it.

Nevertheless, there are quite a few differences between the two modules and it's these that most interest me. The most immediately apparent one is the game line for which each was published. The Keep on the Borderlands bears a banner in its upper lefthand corner, "For Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set," while The Village of Hommlet prominently displays the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons logo – a logo so large, in fact, that it dwarfs the actual title of the module itself. Though I cannot be certain, I suspect that it's this difference – Basic D&D versus AD&D that might explain many of the other differences.

Take, for example, the quote from The Keep on the Borderlands above. The equivalent bit of background in The Village of Hommlet is much longer and not nearly so evocative, reading more like a history – and a dry one at that – of Hommlet and the battle against the forces of the Temple of Elemental Evil: "Hommlet grew from a farm or two, a rest house, and a smithy. The road brought a sufficient number of travellers and merchant wagons to attract tradesmen ..." and so on. There's nothing wrong with this, of course, but it's not particularly inspiring. It comes across like a lecture by a sage rather than a call to adventure.

On the other hand, Hommlet's background is so much more specific than that presented in The Keep on the Borderlands. Whereas module T1's background section gives us lots of names – Oerik, Verbobonc, Nyr Dyv, Dyvers, Nulb, and more – B2 instead offers us "the Realm of mankind," "the Keep," "the Borderlands," and "the Caves of Chaos." Certainly these have a mythic quality to them, like something out of a fairytale or legend, but their purposeful lack of specificity works against the kind of groundedness I feel is necessary to prevent a fantasy setting from "floating away," if you get my meaning.

This lack of specificity applies to the entirety of The Keep on the Borderlands. There are, for instance, no named NPCs in the entire module. Gygax only gives us "the smith," "the barkeep," "the scribe," "the castellan." Even "the Mad Hermit" lacks a name, as does "the evil priest" who oversees "the temple of evil chaos" within the Caves of Chaos. In Hommlet, though, we meet many named individuals, like the brothers Elmo and Otis, Ostler Gundigoot, proprietor of the Inn of the Welcome Wench, Black Jay the herdsman, Canon Terjon, Burne and Rufus, and many more. Hommlet feels very much like a real place, one whose inhabitants are more than just cardboard cut-outs..

Mind you, these differences might simply reflect different intentions. The Keep on the Borderlands is much more clearly intended to be a teaching module, as the extensive Notes for the Dungeon Master make clear. The lack of specificity may have been intended so that individual referees could more easily alter the module and its contents to suit his own tastes and the nature of his own campaign. Meanwhile, The Village of Hommlet, while still introductory in nature, is intended, at least in part, to The World of Greyhawk setting and its conflicts.

Also, as I mentioned earlier in this post, I suspect the fact that B2 is a Basic module while T1 is an Advanced one likewise plays a role. While both The Village of Hommlet and The Keep on the Borderlands are intended for beginning characters, only module B2 is also intended for beginning players. Module T1 is an adventure for the 1st-level characters of already experienced players overseen by an already experienced referee. The Keep on the Borderlands, contrariwise, truly was written as "Baby's First D&D Module" for everyone involved, hence its lack of specificity. Neither approach is inherently superior to the other. Rather, they are written according to the needs of very different audiences, as they should be.

February 22, 2023

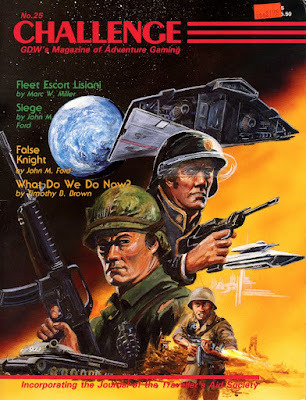

Retrospective: Challenge

The first issue of The Journal of the Travellers' Aid Society appeared in 1979 as a (theoretically) quarterly magazine devoted to GDW's science fiction RPG, Traveller. At that time, Traveller was the company's only actively supported roleplaying game, so it made sense that its sole periodical would be devoted wholly to it. With the publication of Twilight: 2000 in 1984, however, the situation had changed and GDW decided that a gaming magazine with a wider scope was needed.

The first issue of The Journal of the Travellers' Aid Society appeared in 1979 as a (theoretically) quarterly magazine devoted to GDW's science fiction RPG, Traveller. At that time, Traveller was the company's only actively supported roleplaying game, so it made sense that its sole periodical would be devoted wholly to it. With the publication of Twilight: 2000 in 1984, however, the situation had changed and GDW decided that a gaming magazine with a wider scope was needed.

That magazine was Challenge and its advent in 1986 was initially controversial, at least among Traveller fans. Its inaugural issue was not designated "No. 1" but rather "No. 25," on the basis that it was a continuation of JTAS rather than being its replacement. This was done in large part to assuage the concerns of Traveller fans who feared that GDW was abandoning their beloved game in favor of Twilight: 2000. To further allay their fears, issue no. 25 devoted all of its Traveller articles in a separate section in its center pages that mimicked the format and layout of the original JTAS. Loren Wiseman's opening editorial even notes that "the center 8 pages are designed to be removed" by "those not interested in Twilight: 2000," thereby preserving the illusion that JTAS still existed.

This situation did not last long, however. The combination of the popularity of Twilight: 2000 and the release of its sci-fi sequel, Traveller: 2300, later that same year put an end to this internal JTAS section after only three issues. If GDW received any complaints about this, the company could quite correctly argue that the coverage of Traveller had not decreased on an issue-by-issue basis, only that other GDW games were now placed on equal footing. Moreover, given that Challenge was appearing bimonthly rather than quarterly as JTAS had been, the amount of new Traveller material released each year was actually increasing. It helped, too, that the quality of Challenge's Traveller articles remained high, thanks in no small part to the many JTAS writers who continued to pen material for the new magazine.

Even so, the Traveller fans were correct in their original anxieties. As time went on and GDW expanded its catalog of roleplaying games, the amount of space devoted to Traveller – and eventually its ill-named successor, MegaTraveller – started to decline. The articles remained quite good, by and large, but there were a lot fewer of them, a situation that only worsened when Challenge expanded its coverage yet again, in 1988, to include non-GDW games, like Battletech, Star Trek, and Star Wars, among many others. It was around this time that the magazine changed its subtitle from "GDW's Magazine of Adventure Gaming" to "GDW's Magazine of Futuristic Gaming" (and, later, "The Magazine of Science-Fiction Gaming"), since its focus remained RPGs that could broadly be called "sci-fi" in their content.

Devoted fan of Traveller that I was – and am – I was never as put off by this expansion of scope as were some of my older contemporaries. The mere fact that I now had a gaming magazine devoted solely to science fiction games was more than enough to win my allegiance. Challenge was thus an excellent companion to Dragon, whose focus on SF had always been spotty (all the more so after the ending of the "Ares Section" not long after Challenge first appeared). Consequently, it soon became my favorite RPG periodical.

Challenge was also where I first tried my hand at professional RPG writing. My very first published credit, "Contact: Answerin" appeared in issue no. 55 (December 1991) and, over the next few years, right up until the magazine's demise in 1995, my byline appeared quite regularly in its pages. This fact probably plays some role in my affection for Challenge, though not all of it. The magazine excelled in the area of adventures, with a good amount of its regular content being clever scenarios for a wide variety of SF RPGs. It also included equally clever rules expansions and options, which were just as welcome at my table.

Until I started writing this post, I'd half-forgotten how much I'd enjoyed reading and writing for Challenge. As with my thoughts about its publisher, GDW, thinking back on Challenge – and the times during which it flowered – ushers in some feelings of wistfulness and melancholy in me. Ah, well ...

February 21, 2023

For Every Era ...

As I mentioned in my Retrospective post, I haven't played a lot of GURPS, though I've long admired the ambition of its design. I recall seeing advertisements for the game in various gaming magazines long before I ever opened a copy of the rulebook. This one, from early 1985, really piqued my interest in GURPS, in large part because of the artwork, which had the kind of sober, serious – even a little dull – style that I often find compelling.

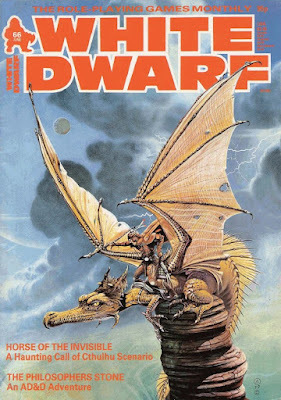

White Dwarf: Issue #66

Issue #66 of White Dwarf (June 1985) is once again graced by a Chris Achilleos cover illustration. I've always been very fond of his artwork and this piece is no exception. This issue also marks another step, albeit a small one, down the road toward Games Workshop's transformation into an all-Warhammer-all-the-time company. Ian Livingstone's editorial opines that "there is obviously a resurgence of interest in wargaming," with the growing popularity of Warhammer Fantasy Battle being offered as evidence of this. I suspect his prognostication would ultimately prove correct. Warhammer's success was real and lasting; it played a huge role in revitalizing the field of miniatures wargaming, a segment of the larger hobby that continues to be very successful (and profitable) today.

Issue #66 of White Dwarf (June 1985) is once again graced by a Chris Achilleos cover illustration. I've always been very fond of his artwork and this piece is no exception. This issue also marks another step, albeit a small one, down the road toward Games Workshop's transformation into an all-Warhammer-all-the-time company. Ian Livingstone's editorial opines that "there is obviously a resurgence of interest in wargaming," with the growing popularity of Warhammer Fantasy Battle being offered as evidence of this. I suspect his prognostication would ultimately prove correct. Warhammer's success was real and lasting; it played a huge role in revitalizing the field of miniatures wargaming, a segment of the larger hobby that continues to be very successful (and profitable) today. Speaking of miniatures wargaming, this issue's "Open Box" kicks off with a positive (7 out of 10) review of FASA's Battledroids, the earliest iteration of the Battletech line of games. Slightly more glowing (8 out of 10) is its review of the second edition of Warhammer Fantasy Battle Rules. There's also a review of the 48K Spectrum version of Talisman (7 out of 10). Rounding out the reviews are The Halls of the Dwarven Kings (8 out of 10) and not one but two Fighting Fantasy gamebooks: House of Hell and talisman of Death (both 9 out of 10). I owned and enjoyed House of Hell, which has a modern day haunted house setting. It also included a Fear score that increases as the reader's character deals with more frights within the titular locale. Once the score reaches a high enough number, the character is "scared to death." The mechanic introduces an interesting dynamic, as the reader tries to avoid encounters, since each one contributes to the Fear score and its inevitable consequences.

Dave Langford's "Critical Mass" laments the "fantasy explosion" in publishing with words I could almost have written: "SF is my true love ... Fie on fantasy: for me the highest literary values consist of megalmaniac computers, hyperspatial leaps and colliding black holes." He then goes on to review multiple fantasy books he considers "consistently better than the SF." Interestingly – or perhaps simply indicative of my own cramped tastes – the only one of these great fantasies he mentions that I recognize is Piers Anthony's On a Pale Horse, the first of his "Incarnations of Immortality" series – and I don't count myself a fan. Langford nevertheless does review a few SF books, including E.C. Tubb's twenty-second Dumarest of Terra novel, The Terra Data. In his review, he notes that "beyond rotten sentences [it] has a plot resembling the previous ones: hero Dumarest tepidly pursued by omniscient yet inept Cybers, fights through unconquerable barriers of padding to obtain secret whereabouts of lost Earth, only to suffer his 22nd failure. Soporific." Cruel but accurate (and I say this as a fan of Tubb).

"The Road Goes Ever On" by Graham Staplehurst is a very nice overview/review of Iron Crown Enterprise's Middle-earth Role Playing and some of its supplements. Reading it again almost made me want to dust off my copy of MERP and give it a whirl again. Part Four of the "Thrud the Destroyer" saga continues, as the evil necromancer To-Me Ku-Pa employs dark sorcery to summon "the essence of evil throughout time." Behold!

"A Web in the Dark" by Simon Burley presents rules suggestions for adapting Spider-Man and similar superheroes to Games Workshop's Golden Heroes (which I need to review one day). "Once Risen, Twice Shy" by Steve Williams and Barney Sloane is a fun collection of documents – news clippings, handwritten notes, reports – that outline a grisly scenario for use with Call of Cthulhu. It's all quite well done and evocative. My only complaint is that the layout of the issue would make it difficult to easily photocopy and use the documents in play. Meanwhile, "Ambush!" by D.P. O'Connor is a three-page treatment of how best to simulate ambushes in Warhammer miniatures battles.

"A Web in the Dark" by Simon Burley presents rules suggestions for adapting Spider-Man and similar superheroes to Games Workshop's Golden Heroes (which I need to review one day). "Once Risen, Twice Shy" by Steve Williams and Barney Sloane is a fun collection of documents – news clippings, handwritten notes, reports – that outline a grisly scenario for use with Call of Cthulhu. It's all quite well done and evocative. My only complaint is that the layout of the issue would make it difficult to easily photocopy and use the documents in play. Meanwhile, "Ambush!" by D.P. O'Connor is a three-page treatment of how best to simulate ambushes in Warhammer miniatures battles. "The Horse of the Invisible" by A.J. Bradbury is an excellent Call of Cthulhu scenario adapted from the William Hope Hodgson story of the same name. The adventure is lengthy, detailed, and, above all, dangerous – as the best CoC adventures are – well done. "The Philosopher's Stone" by David Whiteland is another lengthy and detailed scenario, this time for AD&D characters of levels 1-2. As its title suggests, the adventure involves alchemy and quite cleverly makes use of alchemical mixtures and reactions as part of resolving it. I loved this scenario in my youth and used it to good effect in kicking off a new campaign in my high school era setting.

"The Silent Hater" is a well done installment of "Fiend Factory," which strings together five different AD&D monsters and a map to create the outlines of an adventure for the enterprising referee to drop into his campaign. This is "Fiend Factory" at its best in my opinion and I was always glad to see them. On the other hand, "The Rings of Alignment" by Graeme Drysdale does little for me. There are five such artifact-level rings – one each for Law, Chaos, Good, Evil, and Neutrality – each with their own powerful guardian and special powers to those who wear them, either singly or in conjunction with others. I suppose such magic items have their place in certain kinds of campaigns, but I've rarely found them all that useful.

"Open House" is Joe Dever and Gary Chalk's report Citadel Miniatures' "Open Days," which attracted over 2000 gamers to the company's factory to participate in miniatures battles and painting competitions. The article includes photos of some of the winners of the latter and they are, of course, quite impressive. I find myself, as always, wishing I'd taken up miniatures painting when I was younger. Oh well! Closing out the issue are new episodes of both "The Travellers" and "Gobbledigook."

All in all, this is another worthwhile issue, filled with several excellent articles. That said, the increasing presence of Warhammer and related things is quite clear. I can't say that I blame Games Workshop for emphasizing their own products, especially at a time when they're growing in popularity. However, never having been a miniatures wargamer of any kind, let alone a player of Warhammer Fantasy Battles, I could see the writing on the wall. It wasn't too much longer before I ceased reading White Dwarf and turned my attention elsewhere.

February 20, 2023

The Inspirations of Gamma World

Based on the comments to the second part of my recent post on My Top 10 Non-D&D RPGs, my opinion that Gamma World should be viewed more as an example of the "dying earth" fantasy genre than as an example of straight-up post-apocalyptic science fiction was well received. This got me to thinking a bit more about Gamma World and its inspirations. While I suspect I'll dig more deeply into this in future posts, for the moment I wanted to present what editors Tom Wham and Timothy Jones had to say on this matter.

In their May 21, 1978 foreword to the first edition of the game, they write:

Drawing inspiration from such works as The Long Afternoon of Earth by Brian Aldiss, Starman's Son by Andre Norton, Hiero's Journey by Sterling Lanier, and Ralph Bakshi's animated feature film Wizards, the referee of a GAMMA WORLD campaign fleshes out the game, adding any details he or she deems necessary, and thereby creating a unique world in which day-to-day survival is in doubt. The rules are flexible enough to allow for a variety of approaches to the game – anything from strictly "hard" science-fiction attention to physical probabilities to a free-flowing Bakshian combination of science-fiction and fantasy.

What's apparent from this section of the foreword is that, as written, Gamma World was intended to be a fairly open-ended set of rules without a specific feel beyond whatever the referee introduced into his own campaign. In this respect, it's not unlike Dungeons & Dragons (and indeed most other early RPGs). The explicit inspirations mentioned above are eclectic, though none of them strike me as particularly "hard science fiction." The fact that every edition of the game that I ever owned (1st through 3rd) called itself a science fantasy game is telling.

Still, I think this is a topic worthy of further discussion. I believe there is more going here than is popularly imagined. If nothing else, it'll be yet more grist for my delving into the literary origins of roleplaying games.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers