James Maliszewski's Blog, page 85

January 22, 2023

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Cat and the Skull

Of all of Robert E. Howard's characters, I would argue that Kull is perhaps his most misunderstood – and not without reason. Though Howard wrote more than a dozen stories featuring the Atlantean king of Valusia, only three of them were published during his lifetime. Compared to, say, Conan or Solomon Kane, who appeared in many more stories, Kull seems almost like an afterthought, a character Howard discarded after the publication of "Kings of the Night" in November 1930.

Of all of Robert E. Howard's characters, I would argue that Kull is perhaps his most misunderstood – and not without reason. Though Howard wrote more than a dozen stories featuring the Atlantean king of Valusia, only three of them were published during his lifetime. Compared to, say, Conan or Solomon Kane, who appeared in many more stories, Kull seems almost like an afterthought, a character Howard discarded after the publication of "Kings of the Night" in November 1930. Conan, who first appeared twenty-five months after Kull's published swan song, plays a huge role in explaining why Kull is largely unknown today. Even among those aware of Kull, there's often a false sense that he's little more than a "rough draft" of the Cimmerian, an impression that isn't helped by the knowledge that Howard re-purposed a rejected Kull story, "By This Axe I Rule!," for Conan's debut, "The Phoenix on the Sword."

This is a great shame in my opinion. As characters, Kull and Conan have similarities, to be sure, but they also have differences. These differences are much more apparent when one reads the various unpublished Kull stories that Glenn Lord found in REH's famous storage trunk. Lord, a fan and fellow Texan, tracked down "the Trunk," as it is sometimes known, in 1965, finding that it contained about half of everything Howard had ever written, most of which had never been published in any form – including numerous Kull stories in various stages of completion.

Two years after the discovery of the Trunk, the anthology King Kull was released by Lancer, who'd already found great success with its line of Conan paperbacks. And just like those Conan paperbacks, this volume included posthumous "collaborations" between Robert E. Howard and editor Lin Carter. In this case, Carter finished three incomplete tales of Kull to varying degrees of success. Among the wholly Howardian stories presented for the first time in King Kull is one entitled "Delcardes' Cat" therein but whose proper title is "The Cat and the Skull."

The start of the tale is compelling.

King Kull went with Tu, chief councillor of the throne, to see the talking cat of Delcardes, for though a cat may look at a king, it is not given every king to look at a cat like Delcardes'. So Kull forgot the death-threat of Thulsa Doom the necromancer and went to Delcardes.

Thulsa Doom! Now, there's a name to seize the imagination. Though generations know him as the antagonist in John Milius' Conan the Barbarian, he is, in fact, the archnemesis of Kull and this story marks his first ever mention (and, as it later turns out, appearance) in fiction.

Kull is no fool and is thus skeptical of the existence of a talking cat. Tu is even more "wary and suspicious" in part because "years of counter-plot and intrigue had soured him." Indeed, he suspected that the supposed talking cat "was a snare and a fraud, a swindle and a delusion," not to mention "a direct insult to the gods, who ordained that only man should enjoy the power of speech." Does this sound at all like the opening of a Conan story? The yarn begins almost whimsically and I cannot deny that I was immediately seized with interest in seeing where Howard took things.

The cat, whose name is Saremes, is the companion – not pet! – of Delcardes, a Valusian noblewoman, who is herself described as "like a great beautiful feline," whose "lips were full and red and usually, as at present, curved in a faint enigmatical smile." She has come to the court of Kull to crave a boon from the king. The boon in question is marriage to Kulra Thoom of Zarfhaana, a match that would be forbidden, because "it is against the custom of Valusia that royal women should marry foreigners of lower rank." Delcardes knows this and argues that "the king can rule otherwise," much to the consternation of Tu, who reminds Kull that such a breach of tradition "is like to cause war and rebellion and discord for the next hundred years."

Kull will have none of this.

"Valka and Hotath! Am I an old woman or a priest to be bedevilled by such affairs? Settle it between yourselves and vex me no more with questions of mating! By Valka, in Atlantis men and women marry whom they please and none else."

Delcardes sees this as the perfect opportunity to remind Kull of the cat who accompanied her. The cat

lolled on a silk cushion, on a couch of her own and surveyed the king with inscrutable eyes ... she had a slave who stood behind her, ready to do her bidding, a lanky man who kept the lower part of his face concealed with a thin veil which fell to his chest.

The noblewoman explains that Saremes was "a cat of the Old Race who lived to be thousands of years old." She then asks him to ask the cat her age.

"How many years have you seen, Saremes?" asked Kull idly.

"Valusia was young when I was old," the cat answered in a clear though curiously timbered voice.

Kull started violently.

"Valka and Hotath!" he swore. "She talks!"

Delcardes laughed softly in pure enjoyment but the expression of the cat never altered.

"I talk, I think, I know, I am," she said. "I have been the ally of queens and the councillor of kings ages before even the white beaches of Atlantis knew your feet, Kull of Valusia. I saw the ancestors of the Valusians ride out of the fear east to trample down the Old Race and I was here when the Old Race came up out of the oceans many eons ago that the mind of man reels when seeking to measure them. Older am I than Thulsa Doom, whom few men have ever seen.

"I have seen empires rise and kingdoms fall and kings ride in on their steeds and out on their shields. Aye, I have been a goddess in my time and strange were the neophytes who bowed before me and terrible were the rites which were performed in my worship to pleasure me. For od eld beings exalted my kind; beings as strange as their deeds."

This is great stuff in my opinion. Apparently, Kull thought so too, because his interest is greatly piqued, so much so that he then asks the cat.

"Can you read the stars and foretell events?" Kull's barbarian mind leaped at once to material ideas.

"Aye; the books of the past and the future are open to me and I tell man what is good for him to know."

It's at this point that Kull's skepticism of the existence of a talking cat – a skepticism that Tu still holds – gives way to hope, hope that Serames might possess knowledge that will enable him to make the right decisions as he ponders how to rule Valusia and meet the challenge of Thulsa Doom the necromancer.

What follows is an odd pulp fantasy tale, one in which the barbarian king of a civilized land spends much time discussing fate, prophecy, and free will with a talking cat. I ask once again, does this sound like a Conan story? "The Cat and the Skill" is a fun story, one that nicely balances thoughtfulness with action, honesty with intrigue. That – and I hope no will be surprised to learn this – Serames is revealed to be a fraud, just as Tu warned, in no way takes away from my enjoyment of the story. What transpires before this revelation is thoroughly captivating and a much-needed reminder that Kull is no "rough draft" of anyone, but rather a uniquely engaging character in his own right.

January 21, 2023

Robert E. Howard, Escape Artist

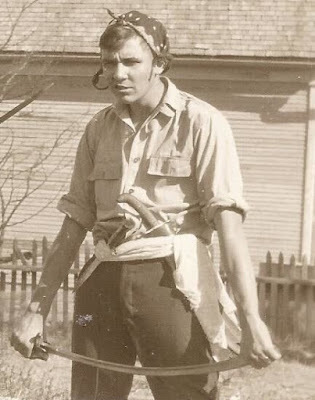

REH (age 18) costumed as a pirate (August 1924)

REH (age 18) costumed as a pirate (August 1924)Adventure

I am the spurThat rides men's souls,The glittering lureThat leads around the world.–Robert E. Howard, Letter to Clyde Tevis Smith (1926)

Today marks the 117th anniversary of the birth of Robert Ervin Howard, creator of such icons of pulp fiction as Conan, Kull, Bran Mak Morn, and Solomon Kane, among many, many more. I don't think it's possible to overstate Howard's importance to the development of sword-and-sorcery literature. The character of Conan is, without a doubt, one of the most well-known fantasy characters of all time and the tales of his adventures established a template that has been widely imitated ever since his first appearance in 1932. These facts alone justify commemorating this day each year.

Of course, like many writers of the past, Howard has his fair share of contemporary detractors, those who criticize not just his writing but also his character. In general, I'm not much given to defending the personalities, choices, or opinions of men who died decades before I was born – not because I cannot recognize their very human flaws but because I know that I, too, might one day be judged by those with the luxury of hindsight. To believe that we, in this present age, have somehow transcended history and, unlike our forebears, hit upon all the Right Ideas that will henceforth be held by all who come after us is the height of hubris. Therefore, I try, not always with success, to limit my criticisms to the fruits of an individual's life.

A common criticism of Howard as man is that, for all the hotblooded machismo of his writings, he was himself a bookish weirdo who lived with his parents for the entirety of his thirty years of life. Howard never travelled outside the state of Texas nor was he a ladykiller, unlike the charismatic adventurers about whom he so often wrote. Instead, say these critics, REH played at being these things, as evidenced by the many photographs that depict the writer wielding a sword, wearing a sarape with a pistol at his hip, or sparring in boxing gloves. He was thus a fake and a fraud, a mama's boy given to bouts of performative masculinity of the sort who ought to be pitied rather than admired.

Like many criticisms, there are germs of truth in even these, but, also like many criticisms, they don't tell the whole story. Howard possessed many idiosyncrasies and his direct experience of the wider world was limited, in some ways more limited even than that of H.P. Lovecraft, which is indeed saying something. However, REH read widely and, through his many friends, both in Texas and across the United States, was able to imagine what it might have been like to sail the seas of Asia with Steve Costigan, to stand his ground against evil with Solomon Kane, and to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth with Conan.

Reading – and, of course, writing – enabled Robert E. Howard to escape from the circumstances of his birth, to escape life in a rough-and-tumble boomtown where someone with his interests and proclivities would always been viewed as an outsider. How many of us reading this have not done the same? One of the lasting joys of the best pulp stories is their ability to transport the reader to exotic locales where he can witness remarkable events and rub shoulders with even more remarkable people. Howard was one of the best tellers of pulp stories who ever lived, perhaps because, before those stories transported his readers, they transported him – away from the Great Depression, his small-minded neighbors, his mother's lingering illness, and the likelihood that he might never amount to anything.

That last fear proved utterly untrue. Though he died never knowing it, Robert E. Howard had a lasting impact on the world, one that can still be felt to this day, especially in this corner of it. Through his stories and the characters they introduced, he not only laid the foundations for an entirely new and popular genre of literature, but he also enabled other bookish weirdos to escape, if only for a little while, from their own circumstances. To me, that's well worth celebrating.

January 20, 2023

How Soon We Forget

TSR, Inc., as a publisher of books, games, and game related products, recognizes the social responsibilities that a company such as TSR must assume. TSR has developed this CODE OF ETHICS for use in maintaining good taste, while providing beneficial products within all of its publishing and licensing endeavors.

In developing each of its products, TSR strives to achieve peak entertainment value by providing consumers with a tool for developing social interaction skills and problem-solving capabilities by fostering group cooperation and the desire to learn. Every TSR product is designed to be enjoyed and is not intended to present a style of living for the players of TSR games.

To this end, the company has pledged itself to conscientiously adhere to the following principles:

1: GOOD VERSUS EVIL

Evil shall never be portrayed in an attractive light and shall be used only as a foe to illustrate a moral issue. All product shall focus on the struggle of good versus injustice and evil, casting the protagonist as an agent of right. Archetypes (heroes, villains, etc.) shall be used only to illustrate a moral issue. Satanic symbology, rituals, and phrases shall not appear in TSR products.

2: NOT FOR DUPLICATION

TSR products are intended to be fictional entertainment, and shall not present explicit details and methods of crime, weapon construction, drug use, magic, science, or technologies that could be reasonably duplicated and misused in real life situations. These categories are only to be described for story drama and effect/results in the game or story.

3: AGENTS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT

Agents of law enforcement (constables, policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions) should not be depicted in such a way as to create disrespect for current established authorities/social values. When such an agent is depicted as corrupt, the example must be expressed as an exception and the culprit should ultimately be brought to justice.

4: CRIME AND CRIMINALS

Crimes shall not be presented in such ways as to promote distrust of law enforcement agents/agencies or to inspire others with the desire to imitate criminals. Crime should be depicted as a sordid and unpleasant activity. Criminals should not be presented in glamorous circumstances. Player character thieves are constantly encouraged to act towards the common good.

5: MONSTERS

Monsters in TSR's game systems can have good or evil goals. As foes of the protagonists, evil monsters should be able to be clearly defeated in some fashion. TSR recognizes the ability of an evil creature to change its ways and become beneficial, and does not exclude this possibility in the writing of this code.

6: PROFANITY

Profanity, obscenity, smut, and vulgarity will not be used.

7: DRAMA AND HORROR

The use of drama or horror is acceptable in product development. However, the detailing of sordid vices or excessive gore shall be avoided. Horror, defined as the presence of uncertainty and fear in the tale, shall be permitted and should be implied, rather than graphically detailed.

8: VIOLENCE AND GORE

All lurid scenes of excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, filth, sadism, or masochism, presented in text or graphically, are unacceptable. Scenes of unnecessary violence, extreme brutality, physical agony, and gore, including but not limited to extreme graphic or descriptive scenes presenting cannibalism, decapitation, evisceration, amputation, or other gory injuries, should be avoided.

9: SEXUAL THEMES

Sexual themes of all types should be avoided. Rape and graphic lust should never be portrayed or discussed. Explicit sexual activity should not be portrayed. The concept of love or affection for another is not considered part of this definition.

10: NUDITY

Nudity is only acceptable, graphically, when done in a manner that complies with good taste and social standards. Degrading or salacious depiction is unacceptable. Graphic display of reproductive organs, or any facsimiles will not be permitted.

11: AFFLICTION

Disparaging graphic or textual references to physical afflictions, handicaps and deformities are unacceptable. Reference to actual afflictions or handicaps is acceptable only when portrayed or depicted in a manner that favorably educates the consumer on the affliction and in no way promotes disrespect.

12: MATTERS OF RACE

Human and other non-monster character races and nationalities should not be depicted as inferior to other races. All races and nationalities shall be fairly portrayed.

13: SLAVERY

Slavery is not to be depicted in a favorable light; it should only be represented as a cruel and inhuman institution to be abolished.

14: RELIGION AND MYTHOLOGY

The use of religion in TSR products is to assist in clarifying the struggle between good and evil. Actual current religions are not to be depicted, ridiculed, or attacked in any way that promotes disrespect. Ancient or mythological religions, such as those prevalent in ancient Grecian, Roman and Norse societies, may be portrayed in their historic roles (in compliance with this Code of Ethics.) Any depiction of any fantasy religion is not intended as a presentation of an alternative form of worship.

15: MAGIC, SCIENCE, AND TECHNOLOGY

Fantasy literature is distinguished by the presence of magic, super-science or artificial technology that exceeds natural law. The devices are to be portrayed as fictional and used for dramatic effect. They should not appear to be drawn from reality. Actual rituals (spells, incantations, sacrifices, etc.), weapon designs, illegal devices, and other activities of criminal or distasteful nature shall not be presented or provided as reference.

16: NARCOTICS AND ALCOHOL

Narcotic and alcohol abuse shall not be presented, except as dangerous habits. Such abuse should be dealt with by focusing on the harmful aspects.

17: THE CONCEPT OF SELF IN ROLE PLAYING GAMES

The distinction between players and player characters shall be strictly observed.

It is standard TSR policy to not use 'you' in its advertising or role playing games to suggest that the users of the game systems are actually taking part in the adventure. It should always be clear that the player's imaginary character is taking part in whatever imaginary action happens during game play. For example, 'you' don't attack the orcs--'your character' Hrothgar attacks the orcs.

18: LIVE ACTION ROLE-PLAYING

It is TSR policy to not support any live action role-playing game system, no matter how nonviolent the style of gaming is said to be. TSR recognizes the physical dangers of live action role-playing that promotes its participants to do more than simply imagine in their minds what their characters are doing, and does not wish any game to be harmful.

19: HISTORICAL PRESENTATIONS

While TSR may depict certain historical situations, institutions, or attitudes in a game product, it should not be construed that TSR condones these practices.

The Latest

While I don't want this blog to become dominated by posts relating to the Open Game License, the truth is that it's a very important topic for those of us in the OSR, because most of our foundational texts (OSRIC, Basic Fantasy, Labyrinth Lord, Swords & Wizardry) were all created through its use. Consequently, any attempt by Wizards of the Coast to "de-authorize" earlier versions of the OGL will have – and already has had – profound repercussions. That's why this stuff is important, even if it's also more than a little confusing at times.

To that end, I would like to direct your attention toward this post by Rob Conley, in which he quite clearly and intelligibly dissects WotC's proposed v.1.2 of the OGL and what its implementation would mean for our little corner of the larger hobby. Rob does a far better job of laying it all out than I ever could and I'm grateful for his continued posts on this matter. I'll almost certainly have some further thoughts of my own later, but, for the moment, I highly recommend the above link.

January 19, 2023

In Defense of Abe Merritt

Today is the 139th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Grace Merritt, better known by his byline of A. Merritt. In past posts commemorating his nativity, I've referred to him as the "forgotten father" of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, since his works, though highly influential during his lifetime – he died in 1943 – aren't much read anymore. Despite this, they exercised a huge influence over the imagination of Gary Gygax. In a comment in Appendix N of the Dungeon Masters Guide, Gygax places Merritt alongside the likes of L. Sprague de Camp, Fletcher Pratt, Robert E. Howard, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft as having played a significant role in his conception of Dungeons & Dragons. That's not only high praise but also, I think, a testament to his unheralded importance as a writer of fantasy.

Today is the 139th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Grace Merritt, better known by his byline of A. Merritt. In past posts commemorating his nativity, I've referred to him as the "forgotten father" of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, since his works, though highly influential during his lifetime – he died in 1943 – aren't much read anymore. Despite this, they exercised a huge influence over the imagination of Gary Gygax. In a comment in Appendix N of the Dungeon Masters Guide, Gygax places Merritt alongside the likes of L. Sprague de Camp, Fletcher Pratt, Robert E. Howard, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft as having played a significant role in his conception of Dungeons & Dragons. That's not only high praise but also, I think, a testament to his unheralded importance as a writer of fantasy.A few months ago, I devoted myself to reading S.T. Joshi's magisterial, two-volume biography of H.P. Lovecraft, I Am Providence. Merritt's name comes up several times throughout, since HPL both admired Merritt's work (particularly The Moon Pool ) and collaborated with him on the round-robin tale "The Challenge from Beyond." The biography notes that, about a month before he died, Lovecraft wrote a letter to C.L. Moore, in which he offered his "final assessment" of Merritt.

Abe Merritt – who could have been a Machen or Blackwood or Dunsany or de la Mare or M.R. James ... if he had but chosen – is so badly sunk that he's lost the critical faculty to realise it ... Every magazine trick & mannerism must be rigidly unlearned & banished even from one's subconsciousness before one can write seriously for educated mental adults. That why Merritt lost – he learned the trained-dog tricks too well, & now he can't think & feel fictinally except in terms of the meaningless & artificial clichés of 2¢-a-word romance. Machen & Dunsany & James would not learn the tricks – & they have a record of genuine creative achievements beside which a whole library-full of cheap Ships of Ishtar & Creep, Shadows remain essentially negligible.I must confess I was somewhat taken aback by Lovecraft's seeming change of heart about Merritt. Even given HPL's well known snobbery and views about the vocation of writing, this assessment comes across as exceedingly harsh, even cruel.At the same time, I can see Lovecraft's point. Merritt's stories do include many of the "artificial clichés of 2¢-a-word romance," from square-jawed heroes to diabolical villains to innocent damsels in distress. The presence in his stories no doubt explains why they were so popular with his readers – and why Merritt enjoyed a much more successful career as a writer than did Lovecraft. Many, if not most, of Merritt's stories touch upon the same themes and play with the same concepts as HPL's tales of cosmic horror, but the cosmicism of Merritt's stories are leavened with the human. They are thus much more approachable and appealing to a wide audience, something Lovecraft never even attempted to understand.

The irony, of course, is that both of Lovecraft's great correspondents and friends, Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith, understood this. Neither shied away from crafting stories that would make them more saleable and popular, even if both would occasionally grumble at having to do so. That's why they both, like Merritt and unlike HPL, were able to provide for themselves and their parents with steady streams of work. Howard, Smith, and Merritt all had no qualms about playing to their markets, even as they produced excellent work that has, in my opinion, stood the test of time.

For me, that's the real point here. Merritt's best stories, like The Moon Pool or The Metal Monster, both of which Lovecraft appreciated, are not lessened by their inclusion of down-to-earth characters and sentiments – what HPL called "pulp hokum" in one of his letters. Their greater accessibility is not a flaw. To put it another way, simply because something is popular does not mean that it is necessarily bad. Lovecraft, I fear, commits the error – I know this because I often guilty of it myself – of assuming that anything that is loved by the masses must by lacking in substance. In addition, he's judging Merritt's success as a writer by his own subjective (and deeply idiosyncratic) standards, which is, in my opinion, deeply unfair.

Yet, for all of this, there can be no question that Lovecraft's own work owed a great deal to the stories of Abraham Merritt. Without The Moon Pool, for example, there might never have been "The Call of Cthulhu," a tale upon which so much of HPL's eventual fame rests. No sneering critiques of his "magazine trick[s] & mannerism[s]" can change that. Nor can they change the fact that writers as diverse as Robert Bloch, Michael Moorcock, Richard Sharp Shaver, Karl Edward Wagner – and, yes, Gary Gygax – thought very highly of him and his imagination. That's not nothing.

In the end, Merritt needs no defense against H.P. Lovecraft or indeed anyone. His work speaks for itself, however poorly known it is in the 21st century. That's why I urge you, if you haven't done so already, to seek out his stories and read them. Most are available for free online and are well worth your time.

By Hand

Last month, I mentioned that I'd be participating in Dungeon23, a challenge to create a 12-level, 365-room megadungeon one room at a time over the course of 2023. One of the reasons I decided to take this up was because I'd already intended to begin more extensive playtesting of the rules for my The Secrets of sha-Arthan RPG this year. Having a large subterranean locale ready for players to explore would help me in this effort, as well as providing me with an opportunity to flesh out the setting further. Thus was born the Vaults of da-Imer.

Though I was very excited by the prospect of detailing the Vaults, one aspect of this project gave me pause: mapmaking. Even in my youth, when I had the time to devote to such things, I was never very good at cartography. Of course, back in those days, I also wasn't very self-aware and so my obvious shortcomings didn't much affect me. I'm not so lucky in my middle age; I am keenly aware of the inadequacy of my mapmaking skills. However, I am elected to proceed nonetheless, drawing the Vault's maps by hand, in the hope that doing so might, if nothing else, encourage me to keep at it until I reach some mediocre level of proficiency.

To that end, here's the first map I drew for the Vaults of da-Imer. It's from a section of Level 1 known as "The Threshold." I've opted to give the Vaults a node-like structure rather than the more traditional approach to dungeons. Hence, Level 1 consists of five complexes of 4–8 rooms, each effectively its own "mini-dungeon" within the larger whole of the Vaults. I've never done a dungeon like this before, let alone one consisting of 365 rooms, so it'll be interesting to see how it turns out in the end.

The Highest Level of All

One of the stranger games to have been released during the first decade of the hobby was Fantasy Wargaming. Though I've never played it (and unlikely to ever do so), the game nevertheless exercises a strange fascination over me. I still have a copy of it on my bookshelf and take it down a couple of times each year to browse. In a strange way, I find re-reading it oddly heartening, because it's quite clear that, for all its many oddities, Fantasy Wargaming was a true passion project by its authors.

One of the stranger games to have been released during the first decade of the hobby was Fantasy Wargaming. Though I've never played it (and unlikely to ever do so), the game nevertheless exercises a strange fascination over me. I still have a copy of it on my bookshelf and take it down a couple of times each year to browse. In a strange way, I find re-reading it oddly heartening, because it's quite clear that, for all its many oddities, Fantasy Wargaming was a true passion project by its authors.

Mike Monaco of the Swords & Dorkery blog is even more enamored of Fantasy Wargaming than I am. That's why he recently wrote a scholarly book on it, published by Carnegie Mellon University's ETC Press. Entitled The Highest Level of All: The Story of Fantasy Wargaming, the book presents the story of the game's creation, as well that of its creators. Because it's an academic work, I'm not sure how widely distributed it will be, but I'll definitely keep my eye out for a copy. This is a topic that greatly interests me and I suspect it will be a fascinating read.

A Touch of the Folkloric

I'm playing in a casual Dungeons & Dragons game with some old friends of mine. In our most recent session, the player characters were traveling by boat toward a frontier town the bulk of whose population had either died or fled the place thirty years prior as the result of a magical plague. The PCs had been warned beforehand that one of the consequences of this large-scale abandonment was that many of the town's domesticated animals had gone feral and now posed a threat to travelers in the area. The characters were also told to be especially concerned about feral pigs, some of whom, it was said, had taken to walking on their hind legs and carrying weapons.

I'm playing in a casual Dungeons & Dragons game with some old friends of mine. In our most recent session, the player characters were traveling by boat toward a frontier town the bulk of whose population had either died or fled the place thirty years prior as the result of a magical plague. The PCs had been warned beforehand that one of the consequences of this large-scale abandonment was that many of the town's domesticated animals had gone feral and now posed a threat to travelers in the area. The characters were also told to be especially concerned about feral pigs, some of whom, it was said, had taken to walking on their hind legs and carrying weapons.

It's funny. This was just a small detail – a wild rumor given to the characters as they stopped by a village they passed on their way toward the aforementioned town. Yet, that rumor was terrifically evocative and compelling to me. It punched far above its weight as a throwaway explanation of the origin and nature of that stalwart D&D enemy, the orc. Admittedly, I've always been a fan of pig-faced orcs, but this little bit of background information grabbed me, so much so that, here I am, writing a post about it.

I think the reason this in-game rumor so seized my imagination is that it felt like something out of real world folklore, a horrific just-so story to explain the inexplicable. That's something D&D has rarely done at all, let alone done well. The game's approach to monsters, as exemplified by the Monster Manual, is too orderly, too rational, almost to the point of being scientific. That's the downside to Gygaxian Naturalism; it denudes the monsters of their montrosity by unambiguously laying out the truth of the matter in black and white. Come to think of it, the same is true of D&D's presentation of magic too, whether in the form of spells or magic items.

To some extent, this is inevitable. Dungeons & Dragons is a game and games have rules. Those rules need to be expressed as clearly as possible and doing so often militates against the sort of ignorance and mystery that's needed for good folklore. Fortunately, the rules of D&D have never been exemplars of clarity, which leaves space for the individual referee to put his own spin on things from time to time, as my friend did last night with his version of orcs. D&D – and fantasy RPGs generally – need more of this kind of thing.

January 18, 2023

Traveller Open Content

Though I'm a committed classic Traveller fan, I've lately been taking a much greater interest in Mongoose Publishing's Traveller line, which I've (largely) found to be a solid updating of both the rules and the Third Imperium (Charted Space) setting. Earlier today, Matthew Sprange posted the following:

In light of recent events, Mongoose Publishing is going to be introducing a brand new Traveller Open Content programme, allowing gamers and publishers to build their own projects using the most recent edition of Traveller rules.

We will be working with existing Traveller OGL publishers to build a new SRD based upon the Traveller Core Rulebook Update 2022, using their feedback to ensure best utility, and a logo licence will be made available to clearly mark compatible products.

At this time, we are looking to the ORC licence to maintain openness, now and in the future.

The current TAS programme on Drivethru, which allows the publishing of material set in the official Charted Space universe, will continue to run separately, but alongside, Traveller Open Content.

More news as it develops!

Retrospective: Greyhawk

After more than 300 posts in this series, it's often difficult to come up with an appropriately interesting subject for each week's Retrospective. As a general rule, I try to stick to RPG products published before 1989 or thereabouts, since that marks the beginning of D&D's Bronze Age and a sea change within the larger hobby. I likewise try to stick to RPG products I owned and/or used at the table, or that were at least important to me in some way, though I've often broken this rule over the years. Ultimately, my point is that choosing a product to discuss each week is more of a chore than one might suppose.

After more than 300 posts in this series, it's often difficult to come up with an appropriately interesting subject for each week's Retrospective. As a general rule, I try to stick to RPG products published before 1989 or thereabouts, since that marks the beginning of D&D's Bronze Age and a sea change within the larger hobby. I likewise try to stick to RPG products I owned and/or used at the table, or that were at least important to me in some way, though I've often broken this rule over the years. Ultimately, my point is that choosing a product to discuss each week is more of a chore than one might suppose.In thinking about what to write this week, I eventually realized that, while Original Dungeons & Dragons has always been a staple of this blog, I'd somehow never written specifically about its very first supplement, 1975's Greyhawk. I'd referenced Greyhawk innumerable times, of course, but I'd never given it a proper Retrospective-style treatment. This is an egregious oversight on my part, not simply because of how important Supplement I is to the history of D&D, but also because I've given both Eldritch Wizardry and Gods, Demigods & Heroes this kind of attention, which seems unfair.

From the vantage point of 2023, nearly a half-century after its initial publication, it's likely impossible to appreciate just how significant the appearance of Greyhawk was at the time. Most of its additions to OD&D, from paladins and thieves to new spells, magic items, and monsters, were all later incorporated into the much more widely read Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules. Consequently, a reader coming to Supplement I for the first time might mistakenly fail to see what the big deal was about this 68-page digest-sized booklet. Yet, in many very real ways, this is the volume that transformed OD&D into the game that most of us recognize today, even those playing editions that wouldn't be released until the 21st century.

How could it not? At 68 pages long, Greyhawk is more than half the length of all three volumes of OD&D. The sheer bulk of the new material more or less guaranteed that any adoption of it would change both the character and complexity of the campaign in which it's used. In his foreword, Gary Gygax – then the humble "Tactical Studies Rules Editor" – agrees, noting that "what is herein adds immeasurably to the existing game." Greyhawk, he later explains, includes "new rules, additions to existing rules, and suggested changes." This is true, as far as it goes, since each section of the supplement carries a parenthetical notation, such as "(Additions and Changes)" or "(Corrections and Additions)." However, the overall thrust of the supplement is one of supersession, with the new material being more than simply suggestions the individual referee can either adopt or not, as he sees fit.

Even if that was not the intention, that seems to have been how Greyhawk was widely received at the time of its publication. It is my understanding – and those older than I, who remember those days, can correct me if I am mistaken – that most referees gleefully incorporated the new material into their campaigns without much complaint. After all, they'd already been adding their creations and those of others, too, so why wouldn't they accept the latest word from OD&D's own publisher? Indeed, the cynic in me can't help but wonder if Greyhawk was published so that TSR could get out in front of the torrent of content for D&D being created by someone other than themselves.

As I stated at the start of this post, Supplement I forever changed the face of D&D. For one, it presented two new character classes, a new race (half-elves), and new options for multiclassing by non-humans that further muddled the question of the "right" way to interpret OD&D's notoriously unclear rules about elves. For another, it expanded the mechanical utility of ability scores and changed the way hit dice and hit point accumulation worked. All of this alone would have been sufficient to make OD&D + Greyhawk a very different game than OD&D alone, but Greyhawk offers up even more game changers, like the new experience point awards for defeating monsters. The new system is much less generous than OD&D original system, which the text of Greyhawk dubs "ridiculous." There's also the alternate weapon (and monster) damage system and an early version of AD&D's weapon vs AC table.

Then, there are the new spells, with their expanded level ranges. Magic-users now have spells have up to 9th level and clerics up to 7th, where before they were limited to 6th and 5th respectively. Among the new spells introduced in this supplement are many mainstays of the game, like magic missile, web, and silence, 15' radius, as well as many more higher-level spells, like the various power words and resurrection. The cumulative effect of all of this is to raise the power and utility of spellcasters, something that remained true for decades afterwards.

The new monsters include numerous D&D hallmarks, like beholders, umber hulks, and gelatinous cubes, not to mention the Queen of Chaotic Dragons (not yet named Tiamat, however). The list of new magic items is similarly filled with things people now associate strongly with the game, like vorpal blades, bracers of defense, portable holes, and decks of many things. Like the new spells, these additions greatly expand the scope of the game in myriad ways. They also contributed to D&D's growing distinctiveness as a thing unto itself rather than just the random mishmash of ideas and concepts liberally swiped from mythology, folklore, comic books, and pulp fantasy.

I cannot state strongly enough how important the publication of Greyhawk was to the history of Dungeons & Dragons. I'd go so far as to say that no supplement published has ever had as wide-ranging and profound an effect on the game's identity or its content. For good and for ill, the Dungeons & Dragons that exists today, both as a game and as a brand, was born in Greyhawk.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers