The Wages of Naturalism

I think it's fair to say that my post on Gygaxian Naturalism way back in the first year of this blog is one of, if not the, most influential posts I've ever written. I regularly come across people using the terminology, often with no knowledge of its origins, on blogs, forums, and elsewhere. I think that's terrific. I imagine most writers dream of creating something that becomes sufficiently widespread that their own role in creating is forgotten or, perhaps more charitably, subsumed by the creation itself. In any case, I take no small pleasure in having put a name to and explicated a concept that retains some degree of currency in unrelated discussions almost a decade and a half later.

Ironically, my own feelings about the consequences of Gygaxian Naturalism are in flux and with each passing day becoming more negative. To be clear: I'm still very much a proponent of consistent worldbuilding, which is what I think Gygaxian Naturalism is at its root. However, I increasingly feel as if many designers have mistaken consistency, which is generally an unalloyed good, for realism, by which I mean (in this case) operating according to rational – or even scientific – principles. In general, I don't think fantasy is very well served by most expressions of realism, as they will ultimately undermine the fantasy.

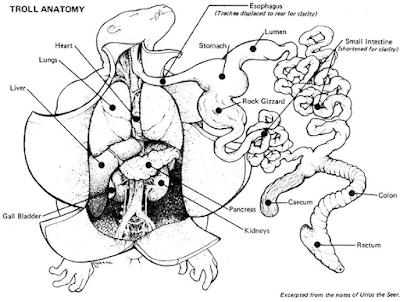

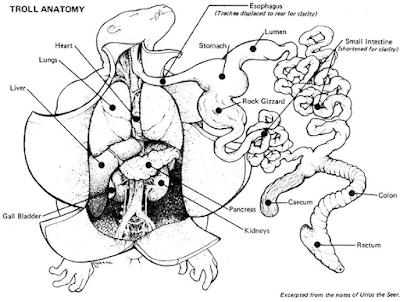

Maintaining consistency and coherence without toppling over into monomanical realism is not easy, so I try not to come down too harshly on lapses. Take, for example, this illustration (by Lisa A. Free) that appeared in the 1982 RuneQuest release, Trollpak, which is widely considered a masterclass in how to present a nonhuman species for use in a roleplaying game.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.

Consider, too, this illustration from issue #72 (April 1983) of Dragon: Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.

Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.

Obviously, everyone draws the line of what constitutes "undermining" fantasy in a different place. But I nevertheless can't help but feel that the tendency toward describing fantastical beings by recourse to rationalistic, scientific categories is an error – an error not just in applying the principle of coherent worldbuilding that undergirds Gygaxian Naturalism but also in understanding fantasy itself. Once upon a time, science fiction was considered a species of the wider genre of a fantasy. SF took place in an imaginary world, as all fantasies do, but one whose imaginary elements were theoretically explicable by recourse to scientific axioms. The anatomical drawings above seem to be tentative examples of applying science fictional principles to fantasy.

I'm not yet convinced that the approach pioneered by Trollpak or "The Ecology of the Piercer" is the inevitable endpoint of Gygaxian Naturalism. At the same time, I could cite plenty of other examples down through the years that suggest that, for many people, consistency and coherence can only be understood in terms of rationalism and science, even when discussing a purely fantastical world and its inhabitants. I struggle with this myself, so I appreciate the difficulties, even as I regret the outcome.

Ironically, my own feelings about the consequences of Gygaxian Naturalism are in flux and with each passing day becoming more negative. To be clear: I'm still very much a proponent of consistent worldbuilding, which is what I think Gygaxian Naturalism is at its root. However, I increasingly feel as if many designers have mistaken consistency, which is generally an unalloyed good, for realism, by which I mean (in this case) operating according to rational – or even scientific – principles. In general, I don't think fantasy is very well served by most expressions of realism, as they will ultimately undermine the fantasy.

Maintaining consistency and coherence without toppling over into monomanical realism is not easy, so I try not to come down too harshly on lapses. Take, for example, this illustration (by Lisa A. Free) that appeared in the 1982 RuneQuest release, Trollpak, which is widely considered a masterclass in how to present a nonhuman species for use in a roleplaying game.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.

Taken in itself, this anatomical diagram of a troll is a wonderful piece of work that helps ground one of Glorantha's most fearsomely antagonistic species in an almost palpable reality – and that's part of my problem with it. As a setting, Glorantha has a (fairly) consistent tone, one grounded in myth. That's a huge part of its appeal to me. Illustrations like the one above, though, they detract from that mythic feel. Seeing one of the Uz laid out like, dissected and tagged like a cadaver from a Renaissance sketchbook, doesn't, in my opinion, add to the consistent worldbuilding of Glorantha, even if it does shed light on how trolls are able to eat anything. Instead, it actively detracts from any conception of trolls as weird or wondrous inhabitants of the Underworld.Consider, too, this illustration from issue #72 (April 1983) of Dragon:

Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.

Almost anyone who was a reader of Dragon at the time should remember this piece of art, which accompanied "The Ecology of the Piercer" by Chris Elliott and Richard Edwards. At the time it first appeared, I absolutely adored this article and, judging from the fact that it inspired a regular feature in the magazine for many years to come, I suspect I was not alone in my feelings. Like the troll diagram, that of the piercer attempts to present a interpretation of a well-known monster that works pretty well on a rational, scientific level but that, in so doing, also undermines its weirdness and wonder.Obviously, everyone draws the line of what constitutes "undermining" fantasy in a different place. But I nevertheless can't help but feel that the tendency toward describing fantastical beings by recourse to rationalistic, scientific categories is an error – an error not just in applying the principle of coherent worldbuilding that undergirds Gygaxian Naturalism but also in understanding fantasy itself. Once upon a time, science fiction was considered a species of the wider genre of a fantasy. SF took place in an imaginary world, as all fantasies do, but one whose imaginary elements were theoretically explicable by recourse to scientific axioms. The anatomical drawings above seem to be tentative examples of applying science fictional principles to fantasy.

I'm not yet convinced that the approach pioneered by Trollpak or "The Ecology of the Piercer" is the inevitable endpoint of Gygaxian Naturalism. At the same time, I could cite plenty of other examples down through the years that suggest that, for many people, consistency and coherence can only be understood in terms of rationalism and science, even when discussing a purely fantastical world and its inhabitants. I struggle with this myself, so I appreciate the difficulties, even as I regret the outcome.

Published on April 04, 2022 10:00

No comments have been added yet.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers

James Maliszewski isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.