James Maliszewski's Blog, page 115

February 25, 2022

Slaying Monsters Should Be Mostly Fun and Games

February 24, 2022

The Eternal Effigy of Alu Zai

by Zhu BajieAmong the most recognizable pieces of sculpture on sha-Arthan is the Eternal Effigy (or da-Rikan) of Alu Zai. A seven foot tall statue of marble, the Eternal Effigy is the work of a nameless pre-Luminous artist whom history has dubbed simply the Sculptor of Alu Zai. As its name suggests, the da-Rikan was found in the ruined coastal city of Alu Zai before being transported to the Repository of the Archons in Omoritash. The Great Effigy is believed to have been destroyed in that city’s sack in 6:12, but rumors persist that it survived and now lies in one of several hidden treasure troves across the True World (depending on the story), waiting to be found again.

by Zhu BajieAmong the most recognizable pieces of sculpture on sha-Arthan is the Eternal Effigy (or da-Rikan) of Alu Zai. A seven foot tall statue of marble, the Eternal Effigy is the work of a nameless pre-Luminous artist whom history has dubbed simply the Sculptor of Alu Zai. As its name suggests, the da-Rikan was found in the ruined coastal city of Alu Zai before being transported to the Repository of the Archons in Omoritash. The Great Effigy is believed to have been destroyed in that city’s sack in 6:12, but rumors persist that it survived and now lies in one of several hidden treasure troves across the True World (depending on the story), waiting to be found again. The original subject of the da-Rikan is unknown. A common opinion is that it depicts Dro Vanta, the tutelary goddess of Alu Zai, whose blessings and protection ensured the city’s prosperity. However, the sages of the Ruketsa school taught that the statue in fact was a product of the False Dawn – a foretoken of the Light of Kulvu from pre-Luminous times. According to this interpretation, the Eternal Effigy is an icon of Asha (harmony), a foundational concept of The Mirror of Virtue. For that reason, the image of the da-Rikan is used to illustrate many of that exalted tome’s principles.

The Mirror of Virtue teaches that the three faces of Asha represent past (the leftmost face), present (forward), and future (right), as the Light of Kulvu illuminates all times and places. Likewise, Kulvuans are enjoined to learn from the past, be mindful of the present, and prepare for the future; doing so is the path to harmony. Asha wears a threefold crown of subaktu-fish, themselves ancient symbols of rectitude, virtue, and wisdom.

Coiled at Asha’s feet is Chuleksakash, a serpentine monster who symbolizes fear, ignorance, and lawlessness. The beast wears the mask of a Man to hide its true nature, which serves as a reminder to Kulvuans that great evil is not always immediately apparent. Fortunately, the Nen Cha or “blade of light” stands ready to fight Chuleksakash, should Asha require it (and despite the brute’s attempt to seize it for itself – another warning to be wary of disharmony). Similarly, two jaran-serpents coil around Asha’s right arm, one placid and the other coiled to strike. The Mirror of Virtue connects this to Urkuten’s Allegory of the Blind Craftsman and the difficulty of distinguishing between two choices that outwardly seem identical.

Asha’s left hand rests atop three star polyhedrons, each of which represents one of the Four Worlds. At the bottom is the Old World, which, though now barred to Man, is nevertheless the place of his origin. Atop it is the False World, whose inherent instability reveals itself by the way it teeters beneath the True World, as represented by the topmost polyhedron. The Mirror of Virtue is silent on the matter of why the World Between is not included in the Eternal Effigy. Needless to say, this has led to much debate among the schools (and, regrettably, the Exegetical War of 1:282–284).

As the Empire of the Light of Kulvu spread, so too did the Great Effigy of Alu Zai, copies of which appeared throughout its territories. In the present cycle, it is strongly associated with both the glories of that fallen dominion and the philosophical faith that animated it for so long.

Cracks in the Wall

Earlier this month, I recounted how a player character in my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, Aíthfo hiZnáyu, had been (seemingly miraculously) returned from the dead and that the process of his resurrection had left him changed. As described in the linked post, Aíthfo was now afraid of fish. More than that, he was convinced that they were following and plotting against him. This made it difficult for him to travel by water, as he felt the fish in the water all around the vessel and this made him uneasy. Likewise, he forbid the catching, let alone eating, of fish in his presence, much to the chagrin of his uncle Grujúng, who frequently whiled away the hours of sea travel by angling over the side of whatever boat upon which he found himself.

Exactly why Aíthfo had such an irrational fear and hatred of fish was unknown. One of the characters, Znayáshu, was convinced that it held a clue as to the nature of his resurrection. As it turns out, Znayáshu – or, more precisely, his player – was correct. I intended this strange behavior to be the first clue as to what had happened to Aíthfo. However, I was the only person in the campaign who knew the truth; not even Aíthfo's player had any certain knowledge, only guesses and theories. This is typical of the way I referee my campaigns: I'm constantly tossing out little tidbits of information to pique player interest and to encourage them to pursue certain avenues of investigation, but it's entirely up to them to piece them together.

Another clue appeared in last week's session, as the characters' vessel put in at the port of the Naqsái city-state of Chámara. Chámara is an important trade hub between the Naqsái peoples of the eastern part of the Achgé Peninsula and the somewhat mysterious Hnákho peoples of the western part. Since the characters were on their way westward to learn more about the Hnákho, whom they believed to have some connection to the legendary Empire of Llyán of Tsámra, stopping by Chámara made good sense. Furthermore, they needed to resupply, since it had been several weeks since they left the city-state of Pichánmush and their fresh water was dwindling.

Upon leaving their ship, Aíthfo noticed something unexpected. Everywhere in the city he looked, he saw flaws, imperfections that he knew for certain he could exploit militarily. There were weaknesses in the construction of Chámara's walls, defects in the rushqá-ceramic armor and weapons its soldiers carried, and faults in the way its streets and thoroughfares were laid out. In an instant, all Aíthfo saw was evidence that this city of some 200,000 Naqsái was ripe for conquest, if only saw what he did. Idly, he reckoned out loud that, with maybe 60 or 70 well-trained Tsolyáni soldiers, he could took on the whole of Chámara and win. It was all so clear to him that he marveled at the fact that no one else had ever noticed it before and exploited it.

Hearing this was enough to convinced Znayáshu of what had happened to him clan mate. The faiths of several Tsolyáni deities forbid their followers from eating fish for obscure doctrinal reasons. One of these deities is Chegárra the Hero-King. The Naqsái have a god of their own called Eyenál, whose characteristics are not dissimilar to those of Chegárra, leading Znayáshu to surmise that perhaps Eyenál is simply the local name of Chegárra. Previously, Aíthfo had been resurrected from the dead by the high priest of Eyenál and this sorcery had resulted in his body being inhabited by some part of Eyenál. Perhaps, Znayáshu reasoned, that part still remained within him and effected his second resurrection, this time manifesting within him different special abilities than he'd displayed previously.

As of yet, there's no proof that Znayáshu's theory is correct, in whole or in part, but it seems to fit the limited evidence the characters currently possess. At the very least, it's a reminder that the gods of Tékumel are both real and have been known to meddle in mortal affairs for their own inscrutable reasons. Given that much of the mess currently engulfing the Achgé Peninsula seems to relate to the activities of She Who Must Not Be Named, the dread Goddess of the Pale Bone, who seeks to eliminate all life from the face of Tékumel, it is not at all unreasonable to assume the other gods would find a way to oppose her, as they have done in the past.

Is that what has happened to Aíthfo? Only time will tell.

February 23, 2022

Mall Memories

In 1981, about a year and a half after I first played D&D, a new mall opened up not far from my home.

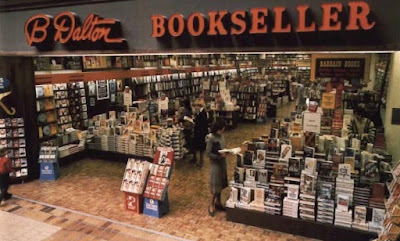

By the standards of the day, the mall was quite large and, as luck would have it, included multiple stores that sold RPGs, wargames, and related paraphernalia. There were, for example, two bookstores whose names are well known to anyone who lived through those years: Waldenbooks and B. Dalton.

By the standards of the day, the mall was quite large and, as luck would have it, included multiple stores that sold RPGs, wargames, and related paraphernalia. There were, for example, two bookstores whose names are well known to anyone who lived through those years: Waldenbooks and B. Dalton.

B. Dalton was the store I relied upon to pick up copies of Dragon magazine, which, for some reason, I had a harder time locating elsewhere in the mall. That said, Waldenbooks generally had a better selection of RPG products, particularly those published by TSR, which were my favorites.

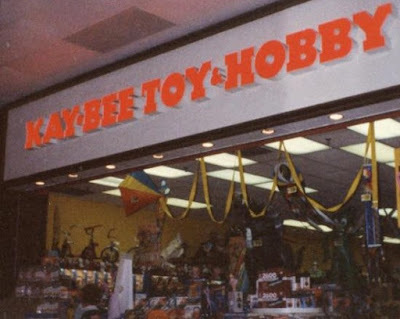

B. Dalton was the store I relied upon to pick up copies of Dragon magazine, which, for some reason, I had a harder time locating elsewhere in the mall. That said, Waldenbooks generally had a better selection of RPG products, particularly those published by TSR, which were my favorites. Also located in the mall was Kay-Bee Toys & Hobby. In fact, at one point, owing to a bizarre turn of events, there were two separate Kay-Bee stores in the mall, each of which had slightly different selections of goods for sale.

I bought my first set of polyhedral dice at Kay-Bee – the notorious "low impact" dice that many of us associate with the Holmes Basic Set. I also picked up quite a few TSR boardgames, like Escape from New York and The Awful Green Things from Outer Space.

I bought my first set of polyhedral dice at Kay-Bee – the notorious "low impact" dice that many of us associate with the Holmes Basic Set. I also picked up quite a few TSR boardgames, like Escape from New York and The Awful Green Things from Outer Space.

The store I liked the most, however, was Games 'n' Gadgets.

Games 'n' Gadgets, as its name suggests, sold a wide variety of entertainments, from boardgames to puzzles to electronic diversions. Naturally, what most interested me were its selection of RPGs, wargames, and miniatures. This is the store where I first picked up Traveller, Gamma World, and too many other non-D&D games to remember. I spent more time staring at its shelves than I can recall; it was a truly wondrous place for me and my friends. Eventually, Games 'n' Gadgets changed its name – to Electronics Boutique and, later, EBGames – and its focus. By the late 1980s, its shelves were taken up almost exclusively by video games and I no longer had much interest in visiting it and an era had come to an end.

Games 'n' Gadgets, as its name suggests, sold a wide variety of entertainments, from boardgames to puzzles to electronic diversions. Naturally, what most interested me were its selection of RPGs, wargames, and miniatures. This is the store where I first picked up Traveller, Gamma World, and too many other non-D&D games to remember. I spent more time staring at its shelves than I can recall; it was a truly wondrous place for me and my friends. Eventually, Games 'n' Gadgets changed its name – to Electronics Boutique and, later, EBGames – and its focus. By the late 1980s, its shelves were taken up almost exclusively by video games and I no longer had much interest in visiting it and an era had come to an end.

February 22, 2022

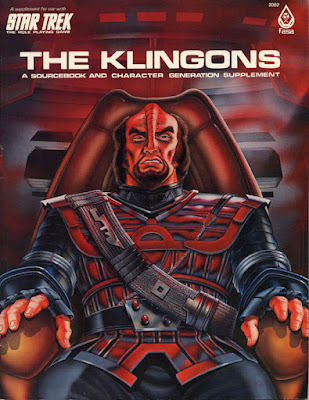

Retrospective: The Klingons

I was quite young when I first encountered Star Trek – perhaps five or six years old. I did so thanks to a paternal aunt who watched it during its original 1966–1969 run, when she was still a teenager. Episodes of the show were a staple of Saturday afternoon syndication during the 1970s and, through them, my aunt introduced me to Gene Roddenberry's masterpiece. I was instantly hooked and, for a long time afterward, I'd proudly call myself a fan.

I was quite young when I first encountered Star Trek – perhaps five or six years old. I did so thanks to a paternal aunt who watched it during its original 1966–1969 run, when she was still a teenager. Episodes of the show were a staple of Saturday afternoon syndication during the 1970s and, through them, my aunt introduced me to Gene Roddenberry's masterpiece. I was instantly hooked and, for a long time afterward, I'd proudly call myself a fan. Consequently, the release of FASA's Star Trek RPG in 1983 was a momentous event, combining as it did my childhood love of the Final Frontier with the hobby of roleplaying to which I'd been later introduced. I can still remember the time spent playing the roleplaying game with my friends and could even now, if pressed, recount in detail the adventures of the USS Excalibur (II) and its crew. Suffice it to say that much fun was had, thanks in no small part to the excellent adventures and source material FASA produced for the RPG over the course of the time the company held the license.

Among these, one of my favorites is the 1983 boxed set entitled simply The Klingons. As you might expect from its title, The Klingons was an expansion of the basic game, enabling players to generate Klingon player characters for use in a Klingon-based campaign. To do this successfully, the expansion had to provide more than just new rules and tables; it also had to provide plenty of details about the Klingon Empire and its society and culture. You must remember that, at the time, there was very little to go on, just a handful of episodes and a single movie in which the Klingons played a role. This meant that it fell to writers John M. Ford, Guy McLimore, Greg Poehlein, and David Tepool to fill in a lot of blanks in the space of the 64-page sourcebook included in the boxed set.

Fortunately, they were more than up to the job and the end result was a remarkable piece of work, one that made the Klingons more than just mustache-twirling villains. Instead, we learn about the Klingon belief in "the naked stars" that keep watch over great deeds performed beneath them, as well komerex zha, "the perpetual game" that governs one's place within the Empire and its hierarchy, and much more. As presented in The Klingons, the Empire operates according to its own internal logic, one based, to a large extent, on the philosophy of "grow or die," hence the Klingon emphasis on – or need for – conquest. Internally, there is a constant jockeying for power between individuals and power groups, with order imposed through a combination of propaganda, fear, and brute force. It's a brutal, cutthroat society but it makes sense by its own lights, which is important for the players to believe in it enough to play an adventure or campaign within it.

The Klingons also includes a couple of sample adventures, each of which demonstrates the kinds of adventures one might undertake as a member of the Klingon Imperial Navy. In a way, they're like a funhouse mirror version of Starfleet. There is new to subjugate and new civilizations to war upon, as well becoming involved in the great game of power and influence within the imperial hierarchy. It's probably not to everyone's taste, but, for many, it's a welcome change of pace from the high-minded ideals of the Federation and the do-gooders of Starfleet.

My friends and I didn't spend much time playing as Klingons, but, when we did, we had fun. More than that, though, it gave us all a better understanding of who these aliens were and how their Empire operated, which was a terrific boon when they served as antagonists in Starfleet adventures. John M. Ford would later write a Star Trek novel, The Final Reflection, which built on the ideas presented in this boxed set. It's probably one of the best Star Trek novels ever written – a low bar, I know – and I've often felt, without much evidence, to be sure, that it has subtly influenced subsequent portrayals of the Klingons in the Star Trek franchise. Regardless of the truth of that, the fact remains that The Klingons is a masterclass in in how to expand upon existing source material to produce something genuinely imaginative for use in a roleplaying game. Nearly three decades later, it has few rivals.

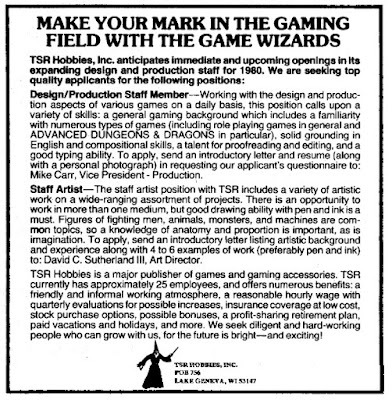

Make Your Mark in the Gaming Field

February 21, 2022

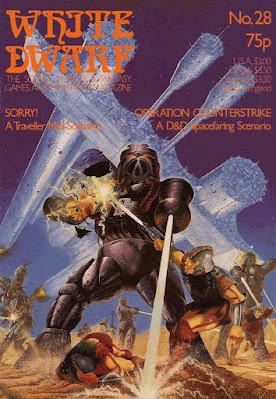

White Dwarf: Issue #28

Issue #28 of White Dwarf (December 1981/January 1982) is the first issue of the magazine not to include its publication date on the cover. I suspect this is part of the ramp up to its going monthly in a few issues. The cover illustration, by Terry Oakes, is another eye-catching science fictional one, something WD did much more often than Dragon, as I've noted on multiple occasions. In his brief editorial, Ian Livingstone alludes to this obliquely when he notes that "role-playing games now cover a multitude of themes." Still, I wonder why it is that SF was so much better covered in White Dwarf than Dragon or Different Worlds. Was there something in the then-current UK zeitgeist that explains it?

Issue #28 of White Dwarf (December 1981/January 1982) is the first issue of the magazine not to include its publication date on the cover. I suspect this is part of the ramp up to its going monthly in a few issues. The cover illustration, by Terry Oakes, is another eye-catching science fictional one, something WD did much more often than Dragon, as I've noted on multiple occasions. In his brief editorial, Ian Livingstone alludes to this obliquely when he notes that "role-playing games now cover a multitude of themes." Still, I wonder why it is that SF was so much better covered in White Dwarf than Dragon or Different Worlds. Was there something in the then-current UK zeitgeist that explains it?The issue begins with a very peculiar article by Andy Slack entitled "The Magic Jar." The purpose of the article is to provide brief conversion guidelines between four different pairs of RPGs: En Garde! to AD&D; Spacequest to Traveller; AD&D to Chivalry & Sorcery; and Spacefarers to Traveller. The guidelines offered are limited primarily to comparing dice probabilities and bits of advice on differences in feel between the paired games. I'm honestly unsure how useful this article would be, but I nevertheless find it fascinating for the games Slack includes. AD&D and Traveller figure prominently, as one might expect. The others are much more obscure today and I can't help but wonder how significant they were at the time of publication.

"Sorry!" is a Traveller scenario by Bob McWilliams specifically written for characters who "shoot first and ask questions later." Basically, McWilliams presents a situation involving multiple alien life forms with which the characters are not familiar and only be observation and thought can they be sure which is – or is not – a threat. Adventures like this are interesting for what they suggest about the play styles of the time. For example, the reference to "shoot first and ask questions later" at the start would imply that The Travellers was more than mere satire.

"Open Box" reviews a variety of game products, starting with the Fiend Folio (8 out of 10), which is it calls "advantageous … [but] not essential to own." ICBM by Mayfair only scores 4 out of 10, in part because it might "have the effect of endorsing Reagan's arms build-up." OK, then. More positively reviewed are Judges Guild's Ley Sector for Traveller (6 out of 10), Marooned/Marooned Alone (10 out of 10), and Library Data (A–M) (9 out of 10), also for Traveller. Finally, there is Undead by Steve Jackson Games (8 out of 10).

"War Smiths" is a new class for AD&D created by Roger E. Moore. It's an unusual class that is somewhat reminiscent of the paladin in that it's a fighter sub-class that can use spells. However, its focus is, as its name suggests, the creation of weapons and armor whose quality improves as they level up. I don't see the necessity for such a class myself, but Moore seems to have done a good job in designing it. I could say similar things about Steve Cook's "On Target," a critical hit system for use with Traveller. "Operation Counterstrike" by Marcus L. Rowland is a D&D adventure for use with the space travel rules he presented in the preceding issues. The adventure is loosely based on The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells – hardly a surprise coming from the writer who'd create the Forgotten Futures RPG.

"Treasure Chest" presents five new magic items, including Jeckyll's [sic] Potion, inspired by The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. It's worth noting that two of the five items are written by Roger E. Moore and another by his wife, Georgia. Meanwhile, "Fiend Factory" details five new sylvan monsters for AD&D, like the (unexpectedly good) black unicorn and birch spirits. While I'm not always keen on the specific monsters featured in these columns, I very much appreciate editor Albie Fiore's use of environmental themes as an organizing principle.

This is another strong issue of White Dwarf. I'm likely biased in this regard, because of my love of Traveller and AD&D, articles for which I generally enjoy. Even so, I don't think it can be disputed that the magazine's quality continues to improve with each issue.

A Tale of Two Adaptations

Interestingly, "The Price of Pain-Ease" was adapted twice in comics form. The first one appeared in the first issue of DC's Sword of Sorcery series (March 1973). Veteran Denny O'Neil is listed as writer, while newcomer Howard Chaykin is the artist. This was, in fact, Chaykin's first significant assignment for DC, so the adaptation has a certain historical importance.

As an adaptation of the story, though, it's awful. O'Neil truncated the story, eliminating the ghosts of Ivrian and Vlana, thereby eliminating much of the tale's melancholy tone, not to mention the central motivation of the Twain. I honestly can't fathom what O'Neil was thinking here, as his excisions undercut everything that make "The Price of Pain-Ease" memorable.

Fortunately, Chaykin at least had a chance to redeem himself, though this time as a writer rather than illustrator. At the start of the 1990s, Marvel's Epic imprint published Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, a four-issue series that adapted many of the stories featuring the titular pair, including "The Price of Pain-Ease," which appeared in issue #3 (January 1991).

Chaykin's adaptation is vastly more faithful to the story than was O'Neil's, which would be enough to set it apart from its predecessor. Almost as remarkable is its artwork, provided by a pre-Hellboy Mike Mignola, with the inking done by the legendary Al Williamson. The Epic adaptations are universally excellent, both in terms of their fidelity and the imagery. Mignola's moody, expressionist style is well suited to Nehwon and especially suits the tone of "The Price of Pain-Ease." All the Epic comics were eventually collected in a single volume by Dark Horse in 2007. It's still in print, so far as I know, and I greatly recommend picking it up, if you've never seen it before.

Chaykin's adaptation is vastly more faithful to the story than was O'Neil's, which would be enough to set it apart from its predecessor. Almost as remarkable is its artwork, provided by a pre-Hellboy Mike Mignola, with the inking done by the legendary Al Williamson. The Epic adaptations are universally excellent, both in terms of their fidelity and the imagery. Mignola's moody, expressionist style is well suited to Nehwon and especially suits the tone of "The Price of Pain-Ease." All the Epic comics were eventually collected in a single volume by Dark Horse in 2007. It's still in print, so far as I know, and I greatly recommend picking it up, if you've never seen it before.

Make Monsters, Not Monstrosities

Larry Elmore joined TSR as a staff artist in late 1981, after which his artwork became a staple of the company's many products, from Dungeons & Dragons to Gamma World and Star Frontiers, among many, many others. My own earliest memories of Elmore's distinctive style are from the pages of Dragon, such as this piece, which appeared in issue #59 (March 1982).

I'm fond of this piece for its humor, a trait I generally associate with the work of the late Jim Holloway. I also have a weird fascination with illustrations that depict ordinary people playing or thinking about roleplaying games, so this one scratches that itch. Take note, too, of Elmore's rendition of Dave Trampier's iconic artwork from the Dungeon Master's Screen, which I think adds to the charm of the whole thing.

I'm fond of this piece for its humor, a trait I generally associate with the work of the late Jim Holloway. I also have a weird fascination with illustrations that depict ordinary people playing or thinking about roleplaying games, so this one scratches that itch. Take note, too, of Elmore's rendition of Dave Trampier's iconic artwork from the Dungeon Master's Screen, which I think adds to the charm of the whole thing.

February 20, 2022

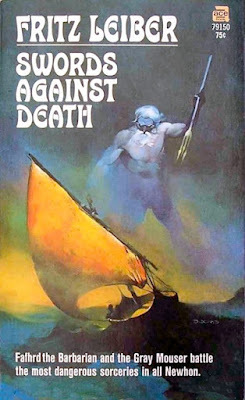

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Price of Pain-Ease

Starting in 1968, Ace Books began collecting Fritz Leiber's stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, many of which had previously been published in various periodicals starting in the late 1930s, into a series of paperbacks. In addition, Leiber penned several new short stories intended to fill in the gaps in the chronology of the Twain's lives, two of which appear in the collection Swords Against Death (1970).

Starting in 1968, Ace Books began collecting Fritz Leiber's stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, many of which had previously been published in various periodicals starting in the late 1930s, into a series of paperbacks. In addition, Leiber penned several new short stories intended to fill in the gaps in the chronology of the Twain's lives, two of which appear in the collection Swords Against Death (1970).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the captious nature of fantasy fans – or indeed fans of any sort – not all of these new tales have been well received. Some of the complaints focus on the content of the additions, which is a little less rollicking than earlier entries in the series, while others focus on their style, which is wordier. Both these complaints have merit, I think, which is why I can't wholly dismiss them as just the cantankerous grumblings of dyspeptic nerds.

Yet, at least in the case of "The Price of Pain-Ease," these complaints sell the story short. Certainly, this story feels different from its predecessors, but, rather than detract from its place within the canon of Nehwon, I think that its differences strengthen it. Take, for example, the opening of the story:

The big barbarian Fafhrd, outcast of the World of Nehwon's Cold Waste and forever a foreigner in the land and city of Lankhmar, Nehwon's most notable area, and the small but deadly swordsman the Gray Mouser, a state-less person even in careless, unbureaucratic Nehwon, and man without a country (that he knew of), were fast friends and comrades from the moment they met in Lankhmar City near the intersection of Gold and Cash Streets. But they never shared a home.

Overly fastidious devotees of Leiber's prose might deem the above in stark contrast with the fast-moving, buoyant tenor of his earlier works. There's no doubt that his style has changed between the publication of "Two Sought Adventure" in 1939 and 1970, but I don't see that as in any way diminishing the yarn he is about to spin, which is every bit as delightfully idiosyncratic – and, above all, human – as any other in the annals of Lankhmar.

The Twain are still mourning the deaths of "their first and only true loves – Fafhrd's Vlana and the Mouser's Ivrian." who had been "foully murdered" in "Ill Met in Lankhmar" and this dark fact hangs like a cloud over the entire story. Drunk after an evening's revels at the Golden Lamprey inn, the friends stumble upon the little estate of Duke Danius, a local aristocrat presently away from the city.

It rested on six short cedar posts which in turn rested on flat rock. Nothing then would do but rush to Wall Street and the Marsh Gate, hire a brawny two-score of the inevitable nightlong idlers there with a silver coin and a big drink apiece and promise of a gold coin and bigger drink to come, lead them to Danius's dark abode, pick the iron gate-lock, lead them warily in, order them to heave up the garden house and carry it out – providentially without any great creakings and with no guards or watchmen appearing.

That's right: Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, with the help of forty men, steal an entire house and transport it to an empty lot behind the Silver Eel tavern. It's a remarkable feat of thievery, even for the greatest thieves in all of Lankhmar, but it's only the beginning of the story. The pair then settle down to living in the Duke's garden home, which turns out to have been the nobleman's love nest, filled as it is with two thick-carpeted bedrooms and whose walls are festooned with erotic murals. It also holds a library of similarly "stimulating" books, which attracts Fafhrd's attention.

The theft was highly successful, they had no trouble from Lankhmar's brown-cuirassed and generally lazy guardsmen, no trouble from Duke Danius – if he hired house-spies, they botched their too-easy job. And for several days the Gray Mouser and Fafhrd were happy in their new domicile, eating and drinking up Danius's fine provender, making a quick run to the Eel for extra wine, the Mouser taking two or three perfumed, soapy, oily, slow baths a day, Fafhrd going every two days to the nearest steam-bath and putting in a lot of time on the books, sharpening his already considerable knowledge of High Lankhmarese, Ilthmarish, and Quarmallian.

Later, Fafhrd discovers a second library, whose books dealt "with nothing but death … at complete variance with the other supremely erotic volumes." The northerner then devotes himself as fervently to these tomes as he had to the more prurient ones he'd found earlier. The two comrades try to enjoy themselves and their stolen home.

However, they didn't invite any girls to their charming new home and perhaps for a very good reason, because after half a moon or so the ghost of slim Ivrian began to appear to the Mouser and the ghost of tall Vlana to Fafhrd, both spirits perhaps raised from their remaining mineral dust around-about, and even plastered on the outer walls. The girl-ghosts never spoke, even in the faintest whisper, they never touched, even so much as by the brush of a single hair; Fafhrd never spoke to Vlana to the Mouser, nor the Mouser to Fafhrd of Ivrian. The two girls were invariably invisible, inaudible, intangible, yet they were there.

After just a few days of these apparitions, both Fafhrd and the Mouser "were rapidly going mad" This compels the pair to seek out – secretly and separately from one another – the aid of "witches, witch doctors, astrologers, wizards, necromancers, fortune tellers, reputable physicians, priests even, seeking a cure for their ills … yet finding none." The apparitions continue and, one night, the Mouser flees from the wraith of Ivrian and into Fafhrd's room, which he finds empty.

Worried, the Mouser heads over to the Silver Eel, where he asks the houseboy there if he'd seen his friend. "Yes," he replies. "He rode off at dawn on a big white horse." But Fafhrd doesn't own a horse. "It was the biggest horse I've ever seen. It had a brown saddle and harness, studded with gold." It's then that the thief notices "a huge jet-black horse with black saddle and harness, studded with silver." Throwing caution to the wind, he approaches the horses, mounts it, allowing it to carry him into the unknown, in the belief that it would lead him to Fafhrd – and perhaps an end to the apparitions that so trouble his sleep and his spirit.

I'm a sucker for moody, melancholic tales and "The Price of Pain-Ease" is very much that sort of story, dealing as it does with the Twain's attempts to get over the deaths of their lovers, deaths for which they blame themselves. The tale's moodiness unquestionably sets it apart from earlier entries in the series and that might not make it to everyone's taste. At the same time, there is plenty of humor – some of it dark – action, and camaraderie, all of which I strongly associate with Leiber's Nehwon works. This very much is a Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story, but it's one written by an older, more experienced Leiber and both in content and style it shows – not that I mind in the slightest.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers