Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 13

February 7, 2023

First Impressions: Gandhi by Bruce Mansfield

I’ve enjoyed every entry in the COIN series that I have played so far. However, I also know that there is no way I could ever own every game in the series - my small European home cannot accommodate them let alone my hectic life. This means that I have spent an inordinate amount of time contemplating which entries in the series I would like to keep on my shelves, playing over and over again, and which I’m happy just experiencing once or twice via someone else’s copy. Pendragon is definitely staying on my shelf for the time being - it’s so different from the rest of the series and I’m a big fan of its late antique/early medieval setting. However, after much debate I decided to trade Andean Abyss away. I enjoyed it and it was very useful for helping me learn (and teach) the system, but my friends didn’t seem to like it as much as I did and playing A Distant Plain made me realise I wanted something a little different. However, I didn’t want to buy my own copy of A Distant Plain because its subject is a little too grim for me to want to play it more than a few times, no matter how much I liked the gameplay. After much internal debate, I decided to pick up Gandhi as my next COIN game. Gandhi’s new non-violent factions and other deviations from the core COIN formula intrigued me but if I’m honest the main appeal of Gandhi lay in two aspects: it isn’t really about war and the short scenario is supposed to be quite good.

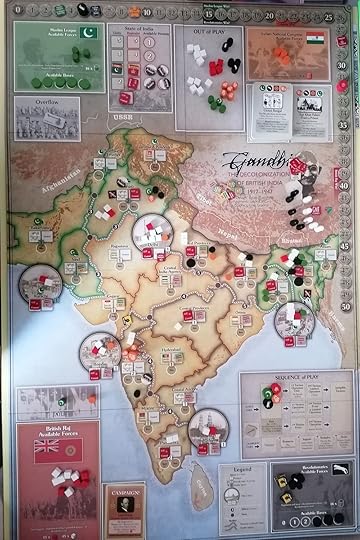

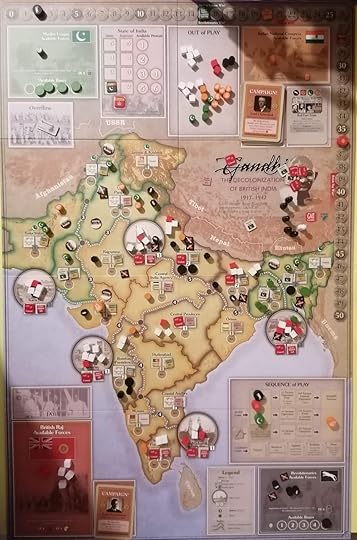

The set up for the short scenario (please ignore any out of place pieces, I had a three year old helper during set up and some incongruities arose)

Now, as you can tell from this blog, I’m not against a good game about war. However, not all my friends are so keen and for a big four player experience like COIN I need more than just myself to get the most out of it. I taught Andean Abyss to my friends and we enjoyed it, but I know the subject matter wasn’t part of the appeal. That’s what I was hoping for from Gandhi - a less violent COIN game for players less interested in games about war. The other aspect of Gandhi that appealed, and which I first saw in Space Biff’s review of it, was that the short scenario is supposed to be quite good. My friends and I are at a stage of our lives where having a full day to play one game is pretty rare so the length component of COIN is a big issue. Andean Abyss kind of only had the long scenario and while Pendragon comes with shorter scenarios, so much of the appeal of that game is seeing the slow collapse of Roman rule over many turns and you miss that in a shorter game. Gandhi having a good and engaging short game that covers a dramatic conflict which is not exactly a war (but also not exactly a peaceful period of history) seemed like a good fit for my group.

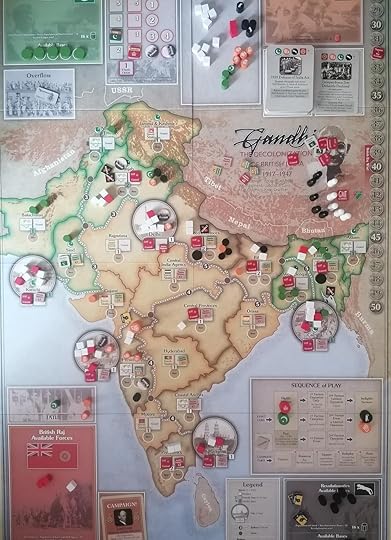

Protests erupt across India and the Raj calls in more troops to try and quell the growing unrest and disaffection.

Now, unfortunately, I can’t yet report on how they have taken to it yet because we haven’t gotten together to play in a little while. However, right after I bought it I was fortunate enough to join a play by email game of Gandhi on Vassal which I supplemented with a four handed solitaire game to get my initial impressions. In my PBEM game I played the Revolutionaries while in the solitaire game I obviously played all the factions. Gandhi does come with a solitaire system that uses a deck of cards as a modified version of the flow charts used in previous games, and I very much hope to learn this system and try it out in the future, but for now I’m still playing it multi-hand. But enough background, what do I think of the game? The short version is that I really like Gandhi but I’m also still only forming my initial impressions.

The addition of non-violent factions didn’t feel as radical as I might have expected, but that may reflect on my still relatively limited experience with the system. In most of my games there was relatively little direct combat among the insurgent factions, excluding one burst of violence near the end of Andean Abyss, so the removal of that option didn’t feel like as fundamental a change to the experience as it looks on paper. That said, the mechanics introduced to replace this more direct form of conflict and the new operations and special abilities added to the factions in Gandhi were all really interesting. The non-violent factions are probably my favourite element of Gandhi even if it is not exactly their inability to attack that makes them so interesting.

End of the first Campaign sees the Revs in the lead but the game could still be claimed by anybody. I think Revs had a natural advantage because of my experience playing them in my PBEM game, plus they’re more similar to insurgents in other COIN games I’ve played. Raj are suffering because I’m bad at being the government player.

I think it’s a nice little touch that the Campaign cards also trigger a change in governor for the Raj - a nice development of Andean Abyss’s change in presidents during Propaganda rounds.

My experience playing the Revolutionaries was one of constantly not having enough funds to do what I wanted to do. While insurgent factions are not often blessed with an abundance of resources the supply felt particularly tight in Gandhi. Similarly, the available pool of units was a really interesting limitation, Players can unlock more pieces over the course of the game, so you can build your strength, but even with the full supply it felt like I didn’t have anywhere near enough. In contrast to playing the Taliban in A Distant Plain, where I could fill the board with a sea of potential terrorists, being the Revolutionaries required careful prioritising of where to focus my forces. In other games I worried about other players removing my pieces, in Gandhi I worried more about just not having enough in the first place. My solitaire experience with the Muslim League and Indian National Congress had me feeling the same limitation not having enough people to complete my plans. This is only a minor deviation from my previous COIN experiences, but it felt significant.

I really loved the mechanics around Unity and Restraint. In general having a set of mechanisms showing the level of disorder in India at the time is really interesting, but what I liked most was how it impacted on the kinds of actions players can take. For Raj and Revolutionaries the cost of actions is at times tied to either Unity or Restraint, so these have a very direct impact on the decisions you make every turn. Similarly, Muslim League and Indian National Congress often have a limit imposed on the number of places they can take their actions - since they have no resources to spend this is the primary limitation on them - based on either Unity or Restraint. The fact that this changes over the course of the game, and generally trends towards a more chaotic India, has fascinating potential for how the game develops. There is definitely a lot of strategic consideration to be made about when to increase/decrease either Unity or Restraint which I must confess I do not fully understand. That not understanding is of course part of the appeal, though, as it’s something I can learn over multiple plays of the game.

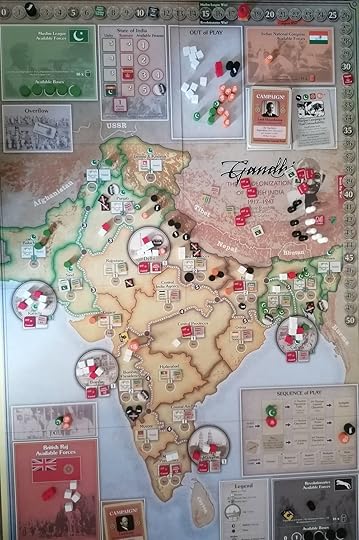

Revolutionaries clear their victory threshold partway through the second Campaign but aggressive play and an unfavourable event have drained their resources to empty. Meanwhile the Muslim League are making steady progress. Can the Revolutionaries hold on? Can anyone stop the Muslim League?

The whole dynamic of Gandhi feels recognisable but unique compared to what I’m used to, and I think this is largely down to the role taken by the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. The two sides are almost allies, both want to increase opposition to the Raj but while the INC cares about opposition everywhere the Muslim League only cares about it in Muslim population regions. The Muslim League also wants to establish separate Muslim States in Muslim population regions. This creates a similar dynamic that I’ve enjoyed in the past, where the two sides are well situated to cooperate but as the game progresses and their victory conditions diverge that cooperation will naturally break down. They also exist sort of between counter-insurgent and insurgent in terms of their role managing the state of the game. They are obviously in opposition to the Raj, and so fulfill something of an insurgent role, but they also play an essential role in suppressing the Revolutionaries, who fulfill a more traditional insurgent role. This places them in an interesting middle ground that felt different from what I’d seen in other COIN games. I think it is these two factions and their role within the game that makes Gandhi feel special and is definitely what I like most about it so far. I think it also maybe makes Gandhi a little more approachable at least in terms of being the Raj. In other COIN games I’ve played it has sometimes felt like the burden of controlling the chaos falls squarely on the COIN faction - I felt this most keenly in Andean Abyss - but in Gandhi while the Raj definitely does need to keep the other factions in line it feels like it is a little more explicit that the other factions all need to keep each other in check, so I think learning to play a COIN faction with the Raj may be a bit easier. But I could be wrong, I am utterly terrible at playing government/COIN factions after all.

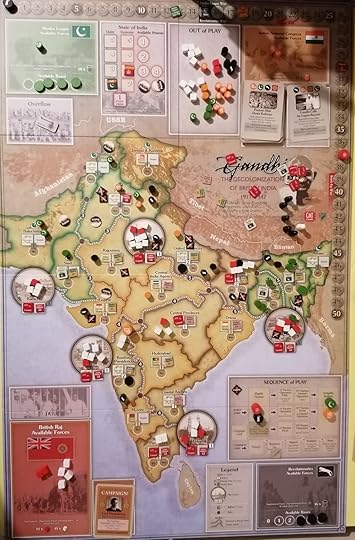

The game ends on the second of three Campaign cards with a Muslim League victory. Both Muslim League and Revolutionaries cleared their victory threshold, but Muslim League win’s on ties - also after taking this photo I did a recount and realised that the Muslim League actually cleared their victory threshold by even more so they would have won even without the tie break.

A few final thoughts in no particular order. For my solitaire game I tried out the short scenario and I was pretty impressed with it - it felt like the game got exciting pretty quickly and the end result was a Muslim League victory on the second out of three Campaign cards. It definitely seems promising as an option for playing COIN in just a few hours.

I have more mixed feelings about playing COIN as a play by email game. I think the system works fine for asynchronous play and I have no critique of my fellow players but playing big multiplayer games asynchronously might not be for me. I found it a bit much downloading all the files and keeping up with the play of the game. I think a prefer the simpler and a little more intimate experience of swapping files with just one other person. I also really missed the kind of wheeling and dealing that can happen around the table during a live COIN game. A lot of COIN strategy is making progress towards winning while also convincing other players that you’re not the threat, it’s actually this other player that’s the real threat. I missed that experience playing it asynchronously. I’ll probably give it another shot sometime in the future. You never know, it could grow on me.

I’m intrigued by what I’ve experienced so far in Gandhi and I’m looking forward to exploring it more. I want to try and learn the solitaire system, something I have previously struggled with, and I really want to play some big four player games as the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress, since they are the most interesting factions to me. I should also try and play some more games as the Raj - I have traditionally been terrible as the COIN faction but I’ll never improve if I don’t practice. Overall, it’s too soon to give much of a judgement on where Gandhi will fit in terms of my preferred COIN games but I’m certainly excited to play more and happy to have it in my collection for the moment.

February 5, 2023

Revisiting Commands and Colors: Ancients by Richard Borg

I played a lot of Commands and Colors: Ancients in college - I convinced the board game society to buy the base game and its first two expansions and for my enthusiasm I was tasked with stickering all three boxes! Luckily I love putting stickers on wooden blocks, so I didn’t mind in the slightest. After I graduated, though, I didn’t play it nearly as much because I didn’t own my own copy and it was harder to borrow the society’s copy when I was no longer an undergraduate (as a post-grad I could be a member but I rarely had the time for hanging around that I used to).

Over December 2022 and January 2023 I got a chance to revisit Commands and Colors as a system thanks to the Homo Ludens Club de Jeu, and it was a blast. While discovering that I could play Memoir ‘44 on my phone via Board Game Arena was definitely the most distracting revelation, I really wanted to make time to play some of the more complex entries in the series. As such, I made an appointment with Joe from the YouTube channel What Does That Piece Do (who had previously served as my opponent for Imperial Struggle) to teach him how to play Ancients since he had only played Memoir before. Joe then had the idea that we should hijack the Homo Ludens YouTube channel for our teach and play, and so we did. You can see the result of that below:

I think it must have been around ten years since I last played C&C Ancients and I had a blast revisiting it. This was always one of my favourite games in the series and I think that remains true. I really want to play more and I’m seriously eyeing up copies so that I can add this to my shelf and hopefully get it played more regularly.

January 31, 2023

Review: Great Heathen Army and the Kingdom of Dyflin by Amabel Holland

Great Heathen Army made my honourable mentions list of favourite games of 2022 and was my fifth most played game last year, so you can probably assume that it’s a game I enjoy. Now that I’ve played through a full campaign of the scenarios in its expansion, Kingdom of Dyflin, I feel like I’m in a better position to share my more mature thoughts in the form of an actual review of the game. For pure playability, in terms of complexity, fun, and speed of play, I think this might be one of my favourite games on medieval warfare and I fully intend to revisit it multiple times in the years to come. I still have a handful of scenarios in the base game I’ve yet to try and there are a good few I’d love to revisit as well. That said, I do have some reservations about Great Heathen Army - it is not a perfect game and some of its problems are what held it back from making my list of favourite games last year.

If you haven’t already you may enjoy reading my first impressions of the game before reading the rest of this review. That post includes a more basic discussion of the game’s mechanics and some comparisons with Men of Iron, the other medieval hex and counter system I have played a lot of. This review will cover some but not all of that ground again, and I will mostly be focusing on elements of the game that I think are interesting to analyse in more detail. You can read my first impressions here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/first-impressions-great-heathen-army

Great Heathen Army’s order system, which it uses to handle activations of your units, remains one of the most interesting parts about the game. Each turn you assign orders to your Wings, which consist of a number of individual units, with the scenario dictating how many orders you can give each turn and the number of Wings that can receive orders. The counters are double sided which makes for an interesting decision because picking one order always limits your choices by removing that token’s reverse side from your pool. The system is easy to learn and teach others as a system but also generally makes for interesting decisions. In particularly I like how Great Heathen Army often gives you more Wings than orders and plenty of scenarios create a bit of asymmetry by allowing one side more flexibility in assigning their orders. Some scenarios even change how many orders a side can give mid-game, which can be really interesting. If I had one critique of this system it would be that I’m not totally sure about the pairing of orders on given counters. Most turns saw me selecting Move + Combat for the Wings I was activating that turn, so most of the time I wasn’t agonising over my decisions. Lots of scenarios also give you duplicates of key orders like Move so you don’t necessarily feel the pinch of not having all the orders you want. The most interesting command was probably the Bonus order which upgrades another order - in particular when to pair that with Combat. Do you want a couple of very good attacks or do you want to move first and get more attacks but they’re not quite as good? This was an interesting decision, especially because scenarios only ever gave me one Bonus order and some even took it away or restricted my access to it in other ways.

A fairly classic set of orders - the Vikings used Move + Fight to close the distance and now the Irish will use Move + Fight on one Wing to push back while the other Wing gets a Horse command because that lets the horses move and fight in one turn.

It may have made more sense if Move and Combat were on the same command, I think that would make the decisions more tense. For example, you can still make a small move if you pick Shield Wall but your attack is weaker (although so is your opponent’s on their turn) as a result so that would make an interesting decision of when is it worth pushing forward in Shield Wall and attacking. It would also mean I would have used Shield Wall more - I didn’t end up using it very often which felt weird for a game about Viking age warfare. I also basically never used Withdraw because there was nothing stopping my opponent from moving forward and attacking again. I should say that this is not meant as particularly strong critique of the game - I really enjoyed the order system overall and this is more of a nit pick. I believe The Grass Crown, the latest entry in the Shields and Swords series (albiet in a slightly new form and covering ancient warfare), may have already changed the layout of order counters. I think that the core of the order system is really interesting but I feel like it could be a little more refined. It’s also possible that because Great Heathen Army was a later entry in an existing system the orders matched the topic a little better in earlier games. I really like this system and I hope Amabel Holland, the designer, decides to return to medieval warfare with a new take on it.

The Grass Crown with its heretical squares and samples of the order tokens on the left. Image courtesy of Pierre, who actually owns it. He says it’s quite good, I haven’t played it though.

The Initiative rule is another aspect of Great Heathen Army I really like but I wonder if it couldn’t be refined a little more. The player who holds Initiative can, at the end of their turn, choose to pass the token to their opponent and then immediately take a second full turn. This is incredibly powerful and I think does a great job of capturing what having the initiative in a battle could yield. The problem is how do you stop people from using it basically every turn? By default Vikings receive a beneficial -1 DRM if they hold the initiative but in my experience it is rarely worth holding on to the token for this bonus alone. Several scenarios have bonus rules that make one side want to hold initiative longer and I think these are a really positive element. In the final battle of Clontarf, which has no such rules, Pierre (my opponent, or possibly victim) and I were basically using the Initiative every turn to take our turns two at a time. This wasn’t strictly a bad experience, but it did feel like it slowed the tempo of the game a bit and I preferred scenarios where deploying the Initiative felt like a more climactic moment. On the whole I really like this system, I just don’t think it’s quite perfect.

I’ve praised it before but after many more games I remain a big fan of Great Heathen Army’s combat results table - a sentence that exudes excessive grognard energy I know. The number of modifiers are relatively few and the shifts between the rows of unit effectiveness feel consequential, both big positives in my book. However, it is the viciousness of the results that I like most. Most rows only have one space with No Effect so most of the time something will happen, and that something can be quite dramatic. The number of Exchange results, which injure both units, makes sending weaker Levy troops to attack enemy Veterans very rewarding - sacrificing a Levy to wound a Veteran is always a good exchange. I also quite like how an Attacker Retreats result forces all attacking units to retreat, which when combined with harsh rules where units that can’t retreat take a loss, can create some very bad outcomes for the attacker especially because the combat modifiers encourage you to gang up and attack with two more units. There are also very few options for recovering strength, limited to only a few special rules in some scenarios, so each result feels impactful. This makes every combat roll interesting and keeps the game moving along at a quick pace without ever entering into a stalemate of troops aimlessly poking at each other to no real effect.

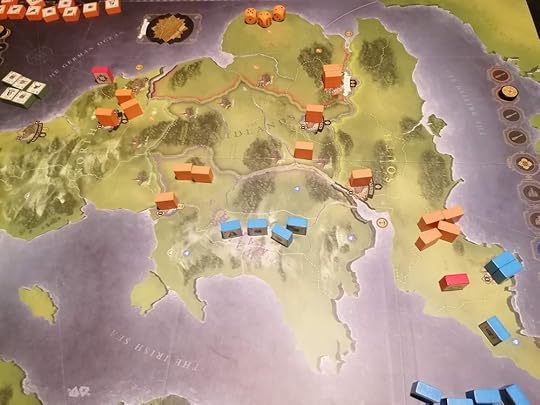

The set up for the second scenario in the base game of Great Heathen Army. I like how it really gets to you into the thick of things very quickly. Also note the d8 in the top left corner. Great Heathen Army uses it instead of the more common d10 and I slightly prefer it, but for entirely tactile reasons. I prefer d8s. I’m sure it does something interesting to the statistical spread but that’s a bit lost on me.

One of my favourite small details in Great Heathen Army is how it handles kings. Kings are Veteran units that are slightly better than other Veterans - they do not lose their combat quality when injured - but they are also worth double the victory points when eliminated. Having high value troops that you want to use but desperately don’t want to lose is a dynamic I adore, but it is not my favourite thing about Great Heathen Army’s monarchs. That belongs to the fact that the crown symbol only appears on the reduced side of the counter. While you know where your kings are during set up, your opponent doesn’t know and you’re not allowed to check once the game has begun. This means that you quickly forget where the kings are and it is often a surprise for both players when a Veteran counter flips to reveal a king. I love this little element of hidden information that spices up the game and can create some very funny moments. More games should hide information on the reverse of counters.

A surprise king is revealed on the left and oh no he is not in a very good position! Meanwhile the Red King’s location remains a secret.

My play through of the scenarios in Kingdom of Dyflin finally let me try the cavalry rules for Shields and Swords and I found them enjoyably simple if not particularly exciting. Cavalry don’t move any further than normal units but they can be activated twice in one turn thanks to their separate Horse Phase (yes, it’s called Horse Phase). This can create some interesting dynamics, particularly in scenarios where you only have one Combat order since the Horse order will let your cavalry move and fight. The choice to incorporate cavalry within existing Wings rather than having their own separate one also makes for interesting choices when it comes to selecting orders. To me, though, the most interesting thing about the cavalry is the rules that let light cavalry (which is all there are in Great Heathen Army, other entries have heavy cavalry) ignore Exchange results on the CRT and retreat instead. This seems like a smaller difference than having a whole extra phase just for them, but I think it made a bigger difference in how I used them. The Horse Phase was like a nice luxury, but knowing that I could avoid a whole result on the CRT was a much more dramatic change to how I used them compared to other units. Like the hidden kings markers, this felt like a nice bit of spice added to the game but nothing that fundamentally changed my experience. They felt like Veterans with special rules rather than a radically different unit type, but I didn’t necessarily mind that. After all, the Viking age wasn’t exactly famous for its cavalry tactics!

For my deep dive into Great Heathen Army I opted to play the scenarios in the Kingdom of Dyflin expansion. I chose this for the fairly simple reason that the expansion covers Viking battles in Ireland. I live in Ireland so that had an instant appeal, plus you don’t get many games about medieval Irish warfare. The Kingdom of Dyflin adds four scenarios to Great Heathen Army, concluding in the Battle of Clontarf - the largest scenario in the Shields and Swords system as it spans two map sheets. I recruited my friend Pierre to command the Vikings as we played through all four battles. This was Pierre’s first experience with the system, but as a fairly experienced hex and counter wargamer he didn’t struggle with the rules. He did struggle with the core wargaming tactic of “rolling well” and lead the Vikings on what must have been some of their most disastrous campaigns.

In Kingdom of Dyflin uses the advanced formation rules, first introduced in Great Heathen Army as an optional variant, as standard rules and I don’t think I’d play the game any other way to be honest. In the advanced formation rules, if any Levy unit is not either adjacent to a Veteran or Cavalry or within two hexes of two other units in its Wing then it is immediately eliminated. This might sound a little confusing but it is pretty clear in play. This can create chains where one Levy is isolated and then its removal means that another one is now isolated and so on down the line. This makes your positioning very important as you need Veterans and Cavalry to keep your Levies on the map. Generally if you’re careful your formations should be fine for most of the game, but in the late game the collapse of one wing can spell the end as 2-3 units evaporate pushing one player over their VP goal. This is actually a pretty satisfying ending I think as it really feels like part of your army has fled the field and your position is doomed. Rules about the coherence of formations is also something I don’t see very often in games like this and I think it captures something that was probably pretty important to warfare during this period. These are not disciplined professional soldiers so keeping them around as things got worse and worse would be increasingly difficult. It also made formation and supporting my weakened lines an incredibly important part of the game as opposed to something like Men of Iron where being Out of Formation feels like a mild inconvenience at worst.

The initial deployment for Cenn Fuait - like all scenarios in Great Heathen Army players have mostly free deployment of their troops. This scenario is interesting because it starts with the Irish on the offensive but once those off map White Vikings arrive the Irish can choose to try and withdraw one of their wings for Victory Points

Kingdom of Dyflin includes four new battles: Cenn Fuait (917), Ath Cliath (919), Glen Mama (999), and Clontarf (1014). These battles include additional rules that made for a really interesting and mostly enjoyable experience. Cenn Fuait has what I think might be the most interesting twist of the lot. In that game the Irish start on the offensive but when the Vikings bring on their third Wing of veterans the game changes and the Irish must designate one Wing as the rear guard and the other as the withdrawing Wing. The Irish player gets a VP for every member of the withdrawing Wing they can move off the map. This creates an interesting dynamic around when does the Viking player bring on reinforcements and risk letting their enemy get away. Similarly, for the Irish you can’t win just by retreating your second Wing so you need to be aggressive to the point where you can withdraw a few units for a possible win. I would definitely revisit this scenario, it’s very cool.

Cenn Fuait: The final Viking Wing has arrived and the Irish position has changed - however retreating all their forces now won’t win the game for the Irish. They need to push what advantage they have before potentially falling back with a few troops to clinch the final victory

In Ath Cliath the Vikings must defend a hill from the Irish while in Glen Mama they must block the Irish from opening a path through the map - representing the Irish trying to clear a road to march down. These two are interesting and they have some intriguing bonus rules, but they aren’t quite as interesting as Cenn Fuait. I had a good time with them and I would definitely try Ath Cliath again - the defend the hill gameplay creates some interesting maneuvering and it played very quickly. I found tracking whether the Irish had opened a hole in the Viking line in Glen Mama a bit tedious so I don’t know if I’m eager to revisit it. It was fun, I didn’t have a bad time, but there are plenty of better scenarios in the base game and Kingdom of Dyflin to keep me occupied without playing this one again.

Cenn Fuait: The final Irish positions - you can see the already dead pile on the maps edge (the Viking dead are off map). While their position has entirely crumbled, retreating those five remaining soldiers over the black and white line will be enough to secure victory.

Clontarf is a monster of a scenario (for this system at least) spanning two maps and using most of the game’s counters. It has a high victory threshold and no special rules to impact it, so it sets up two fairly equal sides to slug it out for supremacy. It’s an interesting scenario due to its scale and I had a lot of fun playing it, but I don’t know that I’d set up Clontarf all that often. Pierre and I used the Initiative token on nearly every turn we had it so more often than not we would each be taking two turns back to back. Given the size of the armies involved this sometimes created pretty substantial downtime, which is something that I think Great Heathen Army generally does a good job at avoiding. I enjoyed the game, but one of the things I really like about Great Heathen Army is that it’s very easy to play in an hour and Clontarf is definitely not that. Without any special rules flair to get me excited to try it again I’m not sure I’ll play Clontarf very often, but since it’s sheer size gives it something of a unique feeling I can’t say I won’t play it again either.

Vikings and Irish square off in Clontarf - it should be noted both that almost all of the map terrain has no affect on gameplay and that the light green horses are part of the Irish Red Wing. I wish the quality of the aesthetics of Great Heathen Army matched the gameplay a little better.

The one big special rule that Clontarf adds is a significant revision of Great Heathen Army’s archery rules. In default Great Heathen Army, archers - who only shoot in the separate Missile Phase and otherwise act as normal Levy troops - cannot inflict any kind of wound on enemy troops. Instead they can suppress enemies which reduces their mobility and makes them more vulnerable to attack. While suppression is a cool mechanism, in practice I never used the Missile Phase. You generally need to roll a 7 or 8 on a d8 (there are some bonuses you can collect to improve that a bit) to successfully suppress an enemy and shooting happens before movement which given that bows barely outrange unit movement makes being in range a challenge. This means you need to carefully align your archers so that they can get shots while also having melee troops nearby to take advantage of the result which will only happen about a quarter of the time. It’s a lot of effort for little to no result.

What Clontarf changes is that instead of suppression you do actual hits on a successful roll. I liked this a lot more. Your chances of hitting are still pretty low but it’s worth trying because the result is so good. Particularly in the mid-game of our battle I started taking pot shots at enemy kings in the hopes of getting lucky (which I did a few times). This rule is probably a little strong to be made default - I would propose maybe just letting missile attacks reduce but not eliminate enemy units - but for the first time I actually used my archers like archers. I was also using the Missile Phase order which gave me more choices on my turn which is always good. Going forward I may try and play a few scenarios with amended archery rules to see if my positive experience applies to other battles as well.

Clontarf: This moment, late in the battle, is when the archers really began to swing the tide. The Irish archers in bright red started taking pot shots at Viking kings, starting with the light blue one on the left, and some good rolls eliminated quite a few Nordic monarchs securing 4 VPs each for the Irish side. As the casualties on the right side of the river show it was reasonably close at this point but those big losses were hard to recover from.

While I really enjoy Great Heathen Army, and the Kingdom of Dyflin especially, I am not without reservations about the game. For me the single greatest downside is that it feels a lot more like a game than a commentary on the history. I feel like I’m playing a really interesting fairly abstract wargame rather than waging medieval warfare. Some of this is in how both sides are almost identical and how the command system abstracts away unit activation significantly from how it would be historically. Another major element is in how you move and position your armies. The punishing retreat rules motivate you to leave a space in your lines so that you can withdraw. Also the ability to move and attack in the same turn and the fact that everyone covers the same fixed distance means that aggressive positioning largely involves putting some units into your opponents threat while lining up a counter punch to hit them once they engage with your line. This isn’t a dynamic I dislike, I actually spent most of my 20s playing a miniatures wargame with exactly that play style, but it doesn’t really feel like the dynamic a Viking army would use. Throwing forward sacrificial bait to pull in a charge might make sense if you were an army of light cavalry fighting the crusaders, but for Viking age foot armies it feels weird and arguably overly complex for the limited discipline of armies of the time. It also resulted in some slightly hilarious looking formations, the kind of thing no reasonable commander would construct.

Clontarf: This formation by the Irish (bottom of the screen) may have been my most unhinged looking across the four game campaign. This is not mid-turn, I chose to arrange them like this and then let Pierre attack me. I would like to note that it actually worked really well, which I’m not sure how I feel about to be honest.

The game also isn’t very attractive. I find the art style broadly endearing, but the fact that both sides’ units mostly look the same is kind of bland and the lack of new units in the expansion to represent the Irish was kind of a bummer. Again, it makes it feel more like an abstract experience. The art doesn’t push me away from the game but neither does it draw me in and make me relate to the units. I processed it more like symbology rather than representations of actual historical humans. In the same vein, more often than not the scenario rules would tell me to ignore the terrain that was printed on the map and treat it basically like an empty board, which further contributed to feeling like I was playing an abstract game.

After your third or fourth battle that’s just this map with the same counters the appeal of the aesthetics begins to fade. This time the battle is Glen Mama, but can you tell at all from the visuals?

None of this should be taken as a scathing indictment of Great Heathen Army, but it does reduce my interest in buying other games in the series. The thinness of the theme means that I’m not desperate to see how this system models a different period of medieval history because I feel like I can kind of guess that it will be kind of similar but with different scenario rules. There’s enough content in Great Heathen Army and the Kingdom of Dyflin to keep me engaged for a while. Also I’m not sure I would play without the advanced formation rules but they aren’t compatible with every entry in the series so that further discourages my interest in those games. Similarly, the art for the units seems pretty consistent across the games which is another mild disappointment. I’m not saying I won’t play any other games, if someone set up a scenario from House of Normandy and asked me to play I absolutely would take them up on that. I’m just not sure I need another on my shelf - I live in a small European house and space is at a premium!

Beyond that, I have a few minor nitpicks, the biggest of which is probably that the CRT page doesn’t have the sequence of play printed on it. The sequence that each order is resolved every turn is very important, for example that missiles and shield wall trigger before movement is essential to the game experience. Since most turns I just did Move + Combat I didn’t memorise the turn order for quite a while so whenever I did mix things up and use different orders I generally found myself double checking what order everything would happen in. It would have saved me time if I didn’t have to flip into the manual to find it. The meanings of the command symbols are printed on the back of the manual, but they aren’t printed in sequence of play order which is a little confusing. This is the pettiest of nitpicks, though, and if I’m down to complaining about this kind of stuff you know the game as a whole is great.

Overall, really enjoyed Great Heathen Army and will continue to play it. I am very interested to see what the future holds for the series, but I probably won’t track down any of the other (now out of print) entries as I feel I have enough in the Great Heathen Army box to keep me entertained for a long time. I would say that the Kingdom of Dyflin battles added a lot to my enjoyment of Great Heathen Army. The four scenarios were among my favourites that I’ve played and I look forward to revisiting them (or nearly all of them anyway) in the future - possibly playing the Vikings this time. While I have my nitpicks about the system they are really minor things that hold a great game back from being an all time classic. I can easily imagine a future entry in the series that improves in these areas being among my favourite games of all time so here’s hoping Amabel keeps designing games like this.

January 23, 2023

First Impressions - Fire and Stone Siege of Vienna by Robert DeLeskie

If the fact that I spent a month playing every game I could find on the 1565 Siege of Malta didn’t give it away, I have a bit of a thing for games about sieges. I think siege warfare is a fascinating and often underrepresented aspect of military history. In my own topic of study sieges were far more numerous and more important than set piece battles but it is the battles that most people have heard of. When it comes to game design battles again dominate, with siege games being relatively few and far between, but I am sympathetic to designers faced with the challenge of making a truly engaging siege game. It is precisely because it is so challenging, though, that I am interested in seeing how game designers approach siege games My fascination with siege games meant that naturally I would be interested in Fire and Stone Siege of Vienna, and it definitely didn’t hurt that the game is gorgeous. That’s why I was very pleased to be invited to be taught the game by the designer and play against Fred Serval on the Homo Ludens YouTube channel. The full video is embedded below and I would recommend watching it, but I also thought I’d give some of my thoughts now that I’ve had time to meditate on my first play of Fire and Stone.

Live teach and play of Fire and Stone on the Homo Ludens YouTube channel featuring yours truly and the designer of the game as guests

One of the most striking aspects of Fire and Stone is it’s focus. Rather than looking at the siege as a whole it zooms in on just one breach and puts you in the shoes of the commanders trying to defend just that section of the Austrian walls. If the Ottomans can succeed at breaking through here they can take the city and so it is up to the Hapsburg commander to hold them back at all costs. I think this is a really smart decision given the kind of game Fire and Stone is intended to be. While I think games can portray the full history of a large scale siege in a very effective way - I’m particularly partial to how the upcoming game Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross, represents all of the 1565 Siege of Malta - doings so generally requires making a very large game. This means large both in terms of rules to capture the many elements of the siege and large in scale, particularly in terms of game length, to fit all that detail in. Fire and Stone is not intended to be a monster of a game, instead it’s meant to be playable in under two hours with relatively easy to understand rules.

To successfully deliver a simple game with a short play time about a large siege like Vienna you have basically two options: strip down the conflict to its barest parts, or consider just covering part of it. While I bet there are games that do the former well, for the most part my experience with games that try to cover an entire siege in a short game have left me feeling a little underwhelmed. Fire and Stone opts for the latter choice and is all the better for it I think. By just giving us one breach it limits the geography we have to contend with and while this does remove some choices from the game - there are no rules for supply or where troops are positioned on the various sections of the wall - this perspective lets it focus on the real meat of the siege: taking fortifications, pushing back assaults, and the brutal attrition of early modern sieges. I think this is an inspired choice and it really makes the game for me.

If it’s not apparent already, I’m really impressed with Fire and Stone. I was intrigued by what it had to offer but I went in to my first game unsure of how I would feel about it. I’m fascinated by siege games but I’m also honestly often underwhelmed by them. As Robert DeLeskie, the game’s designer, says in the video many siege games try and use the language of maneuver in their design when that is really better suited to a set piece battle. I feel like we’re probably on the same page in terms of what we want out of a siege game and that is probably why I like Fire and Stone so much.

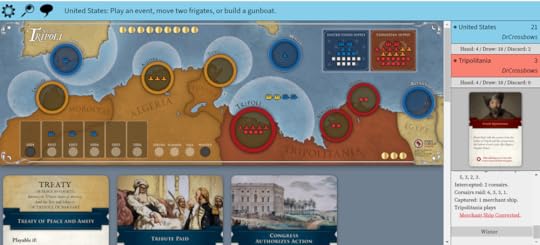

Fire and Stone at it’s core is a relatively simple card driven wargame, probably not much more complicated than something like The Shores of Tripoli. On your turn you can play a card from your hand for its event - which are generally very powerful but also quite situational - or discard it for one of several actions. These actions are slightly asymmetrical but in general they are: bombard the enemy with your guns, launch an attack on one of the board’s few hexes, dig a mine, or build temporary fortifications. There’s a little more to it than that, but not by much. This allows the game to strike a really nice balance between each decision feeling important while also not bogging down as players are paralysed with indecision. The decisions are small, so they’re easy to make, but they’re important so you feel invested in making the right one.

One thing that Fire and Stone does with its deck of cards that I really like is that it has a relatively small deck of events but also you won’t see every card in a given game. A similar structure is true of its small deck of Tactics Cards. This means that it will be beneficial to players to learn their decks, something you can do naturally over a game, but it doesn’t feel like it requires you to learn off what cards will be played in a game. You can be certain that most cards you know will show up in a game, but not every card, and that little bit of uncertainty is an excellent bit of spice to the deck management aspect of the game. While hardly a unique feature of Fire and Stone it’s something a like in the CDGs that I play and it is nice to see it here.

However, the element of the game I like the most is how it represents the attrition of early modern siege warfare. Sieges like this were grueling contests of slowly grinding down your opponent until they couldn’t resist any long. There are no daring feints or dramatic charges that deliver a swift victory at a key moment. This is brutal, slow, grimy siege warfare - no glory to be found! In my game I won - thanks in no small part to some good luck - by grinding down the deck of Ottoman soldiers to the point where my opponent’s ability to launch further assaults was severely diminished. He was making progress, and had even taken the ravelin, but lacked the resources to close the final distance. This felt exactly like how a siege of this period would go and was a really satisfying play experience - for me at least!

In terms of negatives, I suspect for some people the amount of dice rolling might seem objectionable (not me, I love dice) but I do think it is worth considering how low the randomness actually is. Yes you roll fistfuls of dice every time your guns fire but the hits are capped at two for each roll. So having a larger pool of dice does not guarantee you the ability to inflict more hits, it just means that you will reach those two hits more often on average than you would with a smaller pool. This is actually a relatively low luck system, one designed to regress towards the mean much faster than some CRTs I’ve used, disguised as a big dice fest because you’re rolling a large pool of d6s. I think this is really clever, and once again a little reminiscent of The Shores of Tripoli although less random than that game which didn’t cap successful results at all. The satisfaction of rolling lots of dice with less random outcomes, the best of both worlds!

I’ve only played Fire and Stone once so these are really just my very early impressions of the game but I am very impressed with what I’ve seen and I want to play it more because I can tell that there is more depth to the game to be explored. I also have a vacancy in my game collection for an engaging but short siege game which Fire and Stone seems perfectly suited to filling. From my first play I don’t really have any meaningful negatives to mention. It is possible that the Hapsburgs have a more static strategy and maybe if I play the game five or six more times I might grow weary of defending Vienna, but I had a blast playing them this time and if I got another six plays before getting bored that would be a very good return on investment. I’m really excited to explore this game some more and I think I need to try some of Robert DeLeskie’s other games as well.

January 18, 2023

My Favourite Books 2022 Edition

For the last few years I've set myself a goal of reading 50 books a year. While initially pretty achievable, since becoming a parent the challenge of reaching that target has escalated significantly. Last year I barely crept over that line with 51 books read in 2022. While I am pleased to have reached the target, upon reflection I’ve decided to reduce my target to just 40 books in 2023. I read a lot of good books in 2022 but one thing that was clearly missing was big doorstoppers, the kind of books that take me weeks to read. I spent too much time picking books based on reaching my target and not allowing myself to sit and enjoy a book over a longer period. I’m hoping the reduced goal will give me that time while also keeping me motivated and reading every day! Enough musings about my reading habits, though, let’s get on with the list!

I’ve picked a selection of fiction and non-fiction books I really liked in 2022. These are books I read for the first time last year, not necessarily books that were published this year. Same rules as the top games list, basically. While I wrote a review of every non-fiction book I read in 2022, most of which can be found at https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/category/Book+Review, I’ve decided to summarise what I liked about these books again and provided new summaries for the fiction books which I have not previously reviewed.

Non-FictionThe Jacquerie of 1358: A French Peasant’s Revolt by Justine Firnhaber-Baker:

This was the first book I read in 2022 and one of my favourites. A fascinating exploration of the history of medieval France's most famous peasant revolt that breaks myths about how violent it was and provides some great context on what it meant to be a French peasant in the 1350s. While definitely a very academic work I found it relatively easy to read and if like me you enjoy a deep dive into the source material, including considerations for how to engage with it and its limitations, you’re in for a treat because this book has that in spades! History of the medieval peasantry is notoriously difficult due to the limited evidence that we have for them, and in studying the Jacquerie Firnhaber-Baker also opens a door into the lives of the ordinary people of fourteenth-century France. This book is an excellent read and now that it is available in a much more affordable paperback edition I highly recommend it. I got my copy of the book to review it for the journal History, which is why I didn’t publish a review on my blog.

Peacemaking in the Middle Ages: Principles and Practice by Jenny Benham:

January 2022 was a strong month for my book reading as I read this very soon after finishing The Jacquerie. Purchased on a whim during one of the various academic publishing sales that accompanies medieval history conferences (I shop the sales even if I don’t attend the conferences), I was very impressed with this book even as I went in with no clear picture in my mind about what it would cover. This is very much a study of the process of peacemaking in the High Middle Ages and focuses on two case studies, one Anglo-French and one Danish-German, which covers multiple periods of war and peacemaking. The book goes into amazing detail describing things I never would have thought of, such as the geography of how peacemaking was conducted and how medieval people viewed ideas like borders, as well as challenging the teleological bias inherent in much discussion of medieval conflict. That being that just because war was later resumed that a peace negotiation was inherently a failure - particularly when the cause of the new war may be an event entirely out of the control of any negotiating party. A really excellent book that left me with lots to think about.

White Mythic Space: Racism, the First World War, and Battlefield 1 by Stefan Aguirre Quiroga:

Who doesn't want a fascinating exploration of racism, game design, and popular memory of the First World War? If that doesn't sound super interesting to you I don't know if we can be friends. It also helps that Stefan's writing is stellar and the book is immensely readable. A+ no notes, please give me a sequel.

Siege Warfare During the Hundred Years War by Peter Hoskins:

As part of my next book project I spent much of 2022 doing an extended dive into Hundred Years War historiography. While I had a great time with many of these books, and was impressed by the quality of some older histories, I think this is the one that I probably enjoyed the most. I didn't go in expecting much, once you’ve read 4+ surveys of the Hundred Years War you can get a little jaded, but Hoskins delivered a book that felt like it was tailor made to my taste. I’m the insufferable sort who is always harping on about how important siege warfare was and why battles, especially Agincourt, are overrated. Here Hoskins reframes the Hundred Years War to be about it’s famous sieges not its battles and in the process provides a great introduction to late medieval European siege warfare. It’s an engaging read that can really change how you perceive the warfare of this period and the Hundred Years War in particular, highly recommended.

Fiction:Ghost Stories by M.R. James

I always try and read one or two spooky book during October and last year among my choices was a small collection of ghost stories by medievalist and late Victorian author M.R. James. I had heard very good things about his ghost stories but my only real engagement with the form was a few of Dickens’, including his most famous one, so I wasn’t sure what exactly to expect. The result was that I was blown away. It helped that this is exactly my bag - a spooky story about the horrors arising after you find that perfect manuscript you've been desperately searching for? Sign me up! - but on top of that James is a very good writer who constructs a very believable reality to set these stories in. If you’re at all a fan of writers like H.P. Lovecraft or Robert Chambers’ King in Yellow stories you should try M.R. James. Next year I know I’ll be buying a bigger collection.

Cosmic Laughter ed. Joe Haldeman:

I was given this collection of humorous science fiction stories, curated by the great Joe Haldeman, as a Christmas present in 2021 and like many books on this list while I wasn’t sure what to expect I was very pleased with the end result. Published back in the 1970s the stories definitely have an old school sci fi flair to them, think Clarke or Heinlein, but it also made me realise how little funny science fiction I have read. Sure I’ve read some Douglas Adams, but beyond that I’m not sure I could name anything else. Not every story in this book was a home run, but it includes several truly great stories and I really enjoyed my time with them. I wish there was a volume two.

The Honjin Murders by Seishi Yokomizo:

I’ve recently gotten more into murder mysteries. A few years back I got really into classic 1920s detective fiction, Dashiell Hammet and Raymond Chandler et al, but in 2022 I decided I should read some more classic detective fiction - what I tend to think of as “British detective fiction”. My mother-in-law is a big fan of this kind of fiction, she’s read a lot of Agatha Christie, and I had previously gifted her a set of Japanese mysteries that are very much in the vein of Christie. In 2022 she loaned them back to me and my favourite was The Honjin Murder, a locked room mystery set in pre-World War II Japan. It features an eccentric but likeable detective, a tricky mystery, and even includes diagrams of the crime scene! It’s a quick read and not the most complex mystery, but I really enjoyed it and it didn’t overstay its welcome.

The Sunken Road by Ciarán McMenamin:

This past year I also tried to read more historical fiction, something which was helped by a gift I received for Christmas which sent a new historical fiction book to my door every month. Of the ones I received The Sunken Road was my favourite (so far anyway, I haven’t read them all). The narrative skips back and forth between the First World War and the beginnings of the Irish Civil War, following the life of one Irish soldier fighting in both conflicts as well as his best friend and his best-friend’s sister. Themes of sectarian division in Northern Ireland, the messiness of Irish independence, and the horror of war reverberate throughout the text. It’s well written and engaging, but it really won me over when it took a small break to go full Kelly’s Heroes and included a bank robbery in the middle of a battle on the Irish border. It’s understandably a bit of a bleak read, heist sequence aside, and I will not be adding depressing Irish novels about World War I into my regular reading rotation but I really enjoyed it and would recommend it to anyone who likes historical fiction and/or depressing Irish novels.

January 12, 2023

Searching for Black Confederates by Kevin M. Levin

I had heard good things about Kevin Levin’s Searching for Black Confederates from people whose knowledge of the American Civil War and its legacy I hold in high regard, so I was very excited this past December to finally read it. I grew up in central Virginia and the memory of the Civil War was never particularly far away. I remember being taught Lost Cause myths about the Civil War’s origins in school (and then later, thankfully, being un-taught them by a better teacher). I even remember coming across the Black Confederates myth a few times on the Internet in my 20s. That said, while I have strong cultural association with the American Civil War and have picked up a lot of details about it through my childhood and early adulthood, I am not very well read in terms of books on the subject. I read Ron Chernow’s biography of Grant a few years ago and probably read one or two entry level histories in school years ago, but I would not consider myself an expert. In particular, one area I’m hoping to learn more about is the Lost Cause myth and its structure. I know the broad outline, but I’d like to fill in the details and that’s where books like Searching for Black Confederates come in.

For those who may not know the myth that is central to this book’s argument, the Black Confederates story is essentially the idea that somewhere between hundreds to tens of thousands of black southerners fought in the army of the Confederate States of America to defend the South from invasion by Union forces. It should seem fairly obvious that this is patently absurd and utter nonsense, but it has held surprising sway in some corners of the internet over the years. For most of the American Civil War it was illegal under Confederate law to arm black southerners and they were barred from service in the army. The Confederacy did eventually admit black soldiers into its armies during the final phase of the war but there is no evidence that any of the tiny number of black southerners apparently enlisted ever actually mustered as part of the army. What the Confederacy did have was large amounts of slave labour, some brought along by their masters when they enlisted, others press ganged from the surrounding area. What Levin does is more than just point out the failures of the myth, instead he unpicks every detail about why it is false and then examines where the myth came from and traces its legacy through to the present day.

In picking apart the myth of the Black Confederate Levin offers a very detailed study of the role of slaves in the Confederate army, and in particular by examining the lives of specific slaves and their experiences of the war. These are often individuals that Neo-Confederates have attempted to identify as being black Confederate soldiers so these sections do the double job of refuting those specific arguments while also presenting a broader picture of how the Confederate military used slaves and what the experience of being a slave in the army was like. It’s a fascinating examination of an often under-discussed aspect of the Civil War.

From there Levin examines the perception of these camp slaves in the post-war period, in particular how the development of the Lost Cause mythology handled the stories of the now ex-slaves and their relationship with their former masters, both under Jim Crow and during the war. This serves partly as an exploration of the early formation of the Lost Cause and how it was used to justify and enforce Jim Crow but it also feeds into Levin’s broader argument for these early chapters, which is that the notion that black people ever served as soldiers in the Confederate army would have read as completely absurd to the people who participated in the war.

The argument for the existence of Black Confederates is based on faulty reading of quite complex evidence, and in many cases feels a bit like looking at a photocopy of a photocopy of history. Rather than going back to the source, advocates for the story of Black Confederates often rely on (misunderstanding) much later evidence, which they divorce from any context and interpret in a manner that suits them. The politicians of the Confederacy and the veterans who fought to support it would never have given any credence to the idea that black people would have been allowed to serve in the army alongside them as soldiers and Levin clearly shows how controversial any debate around doing just that was on the rare occasions when it happened.

What Levin points out is that the myth of the Black Confederate is a far more recent invention, one formed in the 1970s in a response to both the Civil Rights movement of the previous decade and to stark shifts in scholarly and popular history that saw the tearing down of Lost Cause history and the slow arrival of a more honest and truthful account of the Confederacy and its history. The story of the Black Confederate is nothing more than an attempt to push back against a better understanding of history and a dramatic refusal to come to terms with the horrors of slavery and the Confederacy.

Levin’s book is well written and engaging and a fascinating glimpse not just into a specific aspect of American Civil War history but also into how bad actors deliberately distort history and push narratives for their own political ends. The success of the Black Confederate myth on the internet and its continued survival are stark warnings about how myth can endure in the face of clear refuting evidence. It’s not all doom and gloom, though, as Levin makes it clear that while the Black Confederate myth has succeeded far beyond what its initial proponents probably could have expected, it is still very much a fringe opinion that is pushing back against a tide of changing public perception. While not strictly part of the Lost Cause myth itself, the story of the Black Confederate represents something of a desperate gasp from a dying historiography trying to push back against the march of new (and far superior) historical understanding.

January 9, 2023

First Impressions: Equatorial Clash by Marc Figueras

Equatorial Clash is not the kind of game I am usually drawn to. It’s a modern warfare game depicting events in the 1940s that uses NATO symbols for its units - usually I run from games like that. However, two items drew me to pick it up when I was placing an order with SNAFU games, SNAFU being an excellent online retailer in Spain and publisher of their own line of small to small-ish games. The first, and most striking thing, was the art design by Nils Johansson. Nils is definitely one of if not the most interesting graphic designers working in wargames at the moment and any time I see something he has worked on it will immediately draw a second (or third…or fourth) look from me. The other element was that this was about a conflict I had literally never heard of. Far from being the more conflict of the mid-20th century, this game is about the Peru-Ecuador border war of 1941. Given its amazing appearance and obscure topic, how could I not try it?

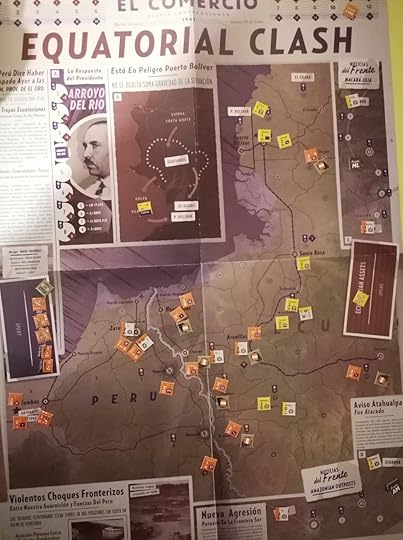

Initial game setup, Peruvian troops massing at the borders while Ecuador attempts to mobilise some opposition. Also, just look at this map, isn’t it great?

I wouldn’t describe Equatorial Clash as fiddly, but it is a game with quite a lot going on. Each round players will swap turns taking impulses where they select from a very wide menu of actions. You are restricted to only taking actions from one scale - e.g. Strategic, Operation, Tactical - but beyond that you can take as many as you want in a given impulse. This was my first time playing a game with any kind of system like this, so I can’t really comment on how like other games Equatorial Conflict is. I found it easy to keep track of the main actions I could do - types of movement, how to fight, that sort of thing - but was somewhat overwhelmed by the available choices beyond that. I focused on the basic actions for the first part of the game and only expanded to the more complex or niche as I learned the systems, which wasn’t bad for learning the game but was probably sub par tactically. There was also a lot of information for me to take on board when learning the game which caused me to overlook some of the rules - some quite significant, others less so.

Four turns in and Peru has breached the border in the south. They probably would have done this much quicker if I’d been better at reading the rules!

My biggest error was in misunderstanding how many Action Points each side has to play with in a given round. I understood rolling a d6 and adding any bonuses for areas on the map under that side’s control, I also remembered (after the first turn) how the politics track affects the Ecuadorian player. What I totally missed for the first half of the game was that the turn track also includes bonus APs for each side, so my early turns involved far fewer Action Points than they should have. While strategically disastrous for the Peruvians who struggled to get their offensive going, it did make the learning a little more manageable. A smaller pool of action points meant that I had a narrower band of actions to choose from and this did help me a bit in avoiding being totally overwhelmed by the menu of options and strategic possibilities present in the game. It also meant that I felt less foolish when I remembered some system I had forgotten, because I probably didn’t have enough spare APs to use it in the previous turn anyway. That said, when I discovered my mistake around turn 7 it nearly tripled the number of APs I had to play with and the game did become significantly more fun and interesting. So my advice would be to play the game correctly, revolutionary I know!

A little over halfway through the game and the Equadorian front is crumbling but Peru will need to penetrate much deeper to call this war a success. Huge amounts of Peruvian troops still haven’t been mobilised.

My other oversight was that you can take multiple actions in one impulse, so long as they are all at the same scale. Again I noticed my error a few turns in, around the time I found out I had far more APs to use than I thought. Initially I was moving all my counters one at a time. My realisation made the whole game make a lot more sense and to be fair, I had suspected I was doing something wrong but was too busy learning all the other systems to really be worried about it. The action selection is really interesting because it’s not like the game is played in strict phases - e.g. there isn’t a single movement phase where you do all your movement. You could choose to move all your counters one at a time, switching back to your opponent every move, or you can do all your moves in one big batch. The thing is that once you Pass that’s it for this round, so there is an incentive to spread your actions out but also you don’t want any of your units to be isolated or to give too much of the initiative to your opponent. It’s a small thing but it made for some interesting decisions.

Having finally figured out how the action points are allotted, the game has picked up the pace significantly. Both sides have assigned troops to fight in the other theaters and Ecuador is even attempting a counterattack along the border. Will it work? Doubtful, but it only has to stall Peru even more.

Equatorial Conflict isn’t necessarily a very complex game, and the rules do a good job of explaining it, but it is a game with a lot of moving parts and playing it solitaire meant that remembering all those parts was all on me. It is also strategically quite complex - I went for a fairly straightforward strategy of just pushing Peruvian troops over the border and taking the closest areas first, but I can easily see how the map and movement rules creates many strategic possibilities. You could get surprisingly deep into this game. This is partly why while I found it perfectly playable as a solitaire experience, I think it will be far better with another player who can help lighten the cognitive load and explore strategic possibilities that may never occur to me.

Peru handily secures the border region and has air dropped in paratroopers in the north in a bid to grab a high value region, but they have been pushed back to a less important part of the map. The war is going in the right direction, but a cease fire could be decided any turn now!

The part of Equatorial Conflict that impressed me the most was the depth of the combat. When reading the rules I was slightly confused about why there were so many kinds of units. Not being familiar with NATO symbols I had to learn them for this game (thankfully there is a breakdown of them on one of the player aids - as an aside the player aids are excellent) and my initial impression was that it felt a bit fiddly having all these unit types for what appeared to be a pretty simple combat system. However, as I played I found the subtle differences in unit strength and type emerged naturally through the gameplay and combat. For example, armour units have great offensive potential but are terrible at absorbing hits inflicted by your opponent and so really have to be supported by infantry. The differences in unit types didn’t need to be spelled out for me, I discovered them naturally through play. This may all be old hat to people who play more modern hex and counter games, but I was really impressed with it.

Cease fire is declared at the end of Turn 11. While Peru is easily pushing Ecuador back from their border it’s not enough to secure victory given their slow start which allowed Ecuador to accumulate VPs early.

One small thing I quite liked about combat was the CRT - specifically how generous it was at allocating hits to both sides in a combat. Going in to a fight with an overwhelming force is great and will likely give you a victory, but it is very unlikely you will escape unscathed. This attrition heavy CRT made each combat feel exciting and created some really interesting results. It avoids being overly random while still also difficult to predict the exact result. I was really impressed.

And on that note, let’s consider the map for a second. I don’t have a whole lot to say about it because I think it pretty much speaks for itself, but it is obviously absolutely gorgeous. The one thing I wasn’t totally clear about was the marking for Swamp and Mountain regions - I think I know which they are but I would have liked a sample in the rulebook because I am notoriously bad at colours. That’s the very slightest of complaints, and even if you ignore the game symbology the map itself makes it pretty clear where mountains and swamp are. Overall, I adore the fake newspaper aesthetic and the integration of the other theaters and tracks on the map is excellent. More games should look like this.

The map is the most immediately stunning part of the production, but the counters are nice and there’s lots of nice little detail in the map that it can be easy to miss when you’re distracted by the whole newspaper of it all.

I went in to Equatorial Conflict without brushing up on the history because I was curious how much of the history I could learn just by the game. It’s rare that I find a game about a topic that I know literally nothing about, so I was intrigued to try a blind play of it. I have to say that having read the background provided in the manual, the game does a pretty good job. Just based on the deployment of troops and victory conditions I could very clearly tell that Peru acted as the main aggressor, invading Ecuadorian territory with the game’s objective being a matter of taking as much territory as possible in the short duration of the war to justify the invasion. It’s hard going, though, and while the positions just across the border are pretty easy penetrating deeper into Ecuadorian territory is challenging. A design evoking the history without needing too much chrome or explanatory text is basically the ideal in my opinion and I think Equatorial Conflict does this excellently.

A side mat tracks VPs, action points remaining in that round, and the possible troops that Ecuador could mobilise if they change their political position - a constant reminder of what you could have!

I also quite liked the counterfactual that is baked into the rules around Ecuador’s president. The president of Ecuador had a poor relationship with the military and wasn’t interested in strengthening their position, in part due to fear of a potential military coup. This meant that Ecuador was very poorly equipped to meet the Peruvian invasion. Equatorial Conflict, however, lets you change this relationship and invest in the military rather than the president which could potentially unlock more units for you to use. Doing so could also prolong the war and will cost you victory points, so it’s a decision that must be heavily weighed. I expect it could also radically change your experience of the game. Ecuador is badly lacking in troops and a game where you take a path of resistance with your tiny forces would be very different from one where you shift the president’s position radically and suddenly have a much larger array of troops to play with.

Overall, I really liked Equatorial Clash. I don’t know that I’ll be playing it solitaire all that many more times, but it is definitely going into the rotation for whenever I can get an opponent who might be interested in it. It’s a fascinating game and if it’s an indication of the kind of designs coming out of SNAFU then I’m very interested in seeing what else they have planned!

January 5, 2023

Life in a Medieval City by Frances and Joseph Gies

You don’t come across popular history quite like this very often. Frances and Joseph Gies produced some of the most popular medieval history of the mid-20th century, and reading it now I can see why. I have previously read their book Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel which was about medieval technology and quite enjoyed that - the scholarship is a little dated in places but it’s a good overview of the subject. I had meant to pick up another one of their books but never quite got around to it until now. I saw a copy of Life in a Medieval City in my local library and took it as a sign. I’m glad I did because this is a great introductory history and I’d definitely recommend it.

From the outset Life in a Medieval City makes a very intelligent decision. Rather than trying to somehow cram an entire millennium and continent’s worth of urban history into one short book the authors decided to take a more focused approach. The book centers on the city of Troyes in northern France in the year 1250 and describes the state of that city at that moment in time. The book is not without some wider, it ventures out to neighbouring territories at times and mentions events that happened a generation or two before and a generation after 1250. Overall, though, the narration focuses on Troyes in the mid-thirteenth century.

The book then walks you through all the important aspects of Troyes during this time - from the layout of the city, to the people who live there and the key features of their day to day life. Understandably given the available evidence it focuses more on the burghers and wealthier members of the city and only gives some glimpses of what life would have been like for the poor people living in the slums. However, overall it provides an excellent insight into the everyday lives of medieval people, far better than pretty much anything else I have read. It also assumes very little in the way of preexisting knowledge, which I found very refreshing. While I’m obviously well versed in aspects of medieval history, urban life wouldn’t be my specialty and sometimes it’s nice for a book to explain things to me in a simple and clear but not patronising manner.

Some caveats must be added, this book was first published in the 1960s and that makes it very old in the scope of modern historical writing. There have definitely been advances in our understanding of medieval lives in that time. That said, I didn’t see many glaring errors - beyond the troubling use of “Moslem” and “Saracen” when the narrative ventures further east or into Iberia - and I think its narrow focus helps to prevent the worst flaws of its age. It’s far from the most up to date work on medieval urban society but it does hold up well as an introduction to the subject - much better than most older histories I have read.

Overall, I was very impressed with Life in a Medieval City and it makes me want to make time to finally read its companion books on medieval villages and castles. This is an excellent work of popular history that’s engaging and well written, well worth a read if its topic interests you.

December 19, 2022

My Top 8 Games of 2022!*

It’s the time of year for Top X lists and as a sucker for the format I couldn’t help but doing one myself. Now look, let’s get this over with straight away: I obviously haven’t played every game that came out in 2022. In fact, I’ve played barely any. I only just got really into historical wargaming this year, so I’ve had a big back log of games to experience. I’m not going to even pretend to list the best games that came out this year. Instead, this list will be my top eight games that I played for the first time in 2022. I chose eight because I’m one of those people who likes to arbitrarily pick a number between five and ten for my top X lists, no other reason. Ranking them has been painful, and if you asked me again in January I’d probably change the order, but at time of publication these are my top eight games that I played this year!

If these games were ranked by how much time I spent thinking about them this one would be a lot higher. Instead I have elected to place it at the bottom not as a reflection of its quality, but rather because it’s not actually a released game and so it feels a little cheeky including it on the list at all. Legion Wargames were nice enough to put me in touch with Andy and he then very kindly spent several afternoons showing me the game and playing through several turns of it. While I only saw a fraction of what this game will be in all its glory (we are still technically playing a PBEM continuation of that game, but I am seriously derelict in taking my turns!) I am now fairly obsessed with this game. When I decided to spend a month playing games about The Great Siege of Malta I didn’t really expect to find something that did such a good job at capturing the scale of the siege as well as all the messy details. This is definitely one of my most anticipated games of whatever year it eventually comes out, and I make no promises not to cheekily include it on that year’s end of year list as well.

This is a playtest version of the game map, not final art. I really like how it focuses on the main bay where most of the siege took place but also makes room to include Mdina and other more peripheral elements. This is essential to they systems that can allow you to deviate from the historic plan the Ottoman commanders used.