Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 16

August 23, 2022

[Malta Month] Playing the Siege of Malta

Having now played multiple games on the 1565 Siege of Malta I wanted to take a minute to think about what I’m looking for in a game about the siege and to reflect a bit on how each of the games I played portrays this historical event. I’ve tried to outline several of the key elements or events of the historical siege that I want a game to incorporate in some form. I will discuss why I think they’re important and how each game approaches them. This is not meant to be a critique of the games – if you want my opinions on playing them you should check out the individual posts on each game (easily found via this linke: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/category/Malta+Month) –instead it is more of a (highly subjective) study of how the siege is portrayed in wargaming.

I should also put as a disclaimer here that there is one game about the Siege of Malta that I haven’t played: Knights of Justice a magazine game published in Wargamer Magazine #50 in 1986. Copies of this are hard to come by so I wasn’t able to play it this month. However, I have found someone who can share their copy with me, but not until they have access to their storage in a few months’ time. When I do get a chance to play it, I’ll write up some general thoughts for a much belated Malta Month post and I may revisit this post then to incorporate the final Malta game.

With the context all settled, let’s jump into the history of the siege and what elements I think are important to capture in a game about it. If you haven’t already, I would definitely recommend reading my summary of the events of the siege I posted at the start of the month. It will provide valuable context and can be read here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/cutting-room-floor-malta

Ottoman LeadershipThroughout the Siege of Malta the Ottoman leadership was seriously fragmented. Mustapha Pasha was commander of the ground forces while Piali Pasha commanded the navy – in theory anyway. Mustapha had been placed in overall command by Suleiman, but Piali had married into the Sultan’s family and had a more powerful position in the Ottoman court, making for an awkward balance of power from the start. At the same time, they had both been instructed to listen to what Turgut, the lord of Tripoli and an effective Barbary pirate with a notorious reputation, had to say in all matters. Turgut was also in direct command of the Barbary corsairs, since they would only listen to him, and had the most experience and prestige, making him a third potential commander. The disputes between the three commanders, two after Turgut was killed by a misfired cannon, created plenty of tension during the campaign.

The first, and to my mind most important, point of contention was how to start the siege. Piali Pasha proposed the plan that was eventually implemented, which was to take Fort St Elmo first and then attack Birgu and Senglea. This was because Piali wanted to moor his fleet in the bay north of Mount Scibberas which wasn’t possible as long as Fort St. Elmo still stood. Mustapha wanted to secure the small island of Gozo and then the capitol city of Mdina before turning on the Hospitaller positions around the Grand Harbour. Turgut preferred Mustapha’s plan but was too late to support his argument, Piali’s plan having already been implemented by the time Turgut arrived.

Mustapha’s plan may have succeeded where Piali’s failed so one of the things I’m interested in is how a game can model the counterfactual of what if the Ottomans had chosen a different course of action.

1565 St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t include this at all – there is no option for battling over Mdina so the only plan to enact is Piali’s.

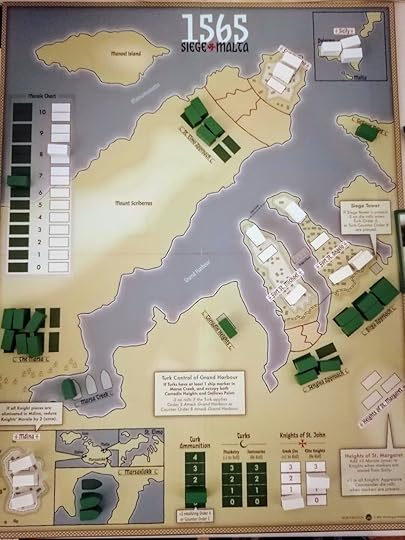

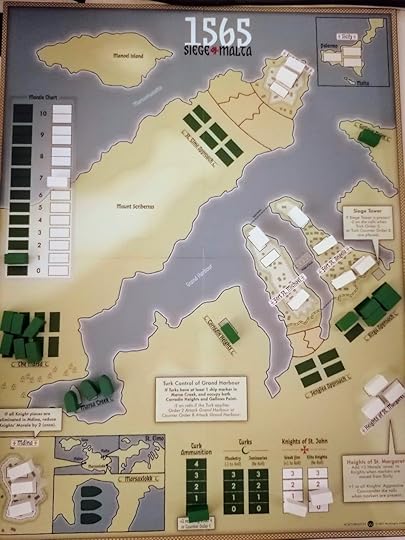

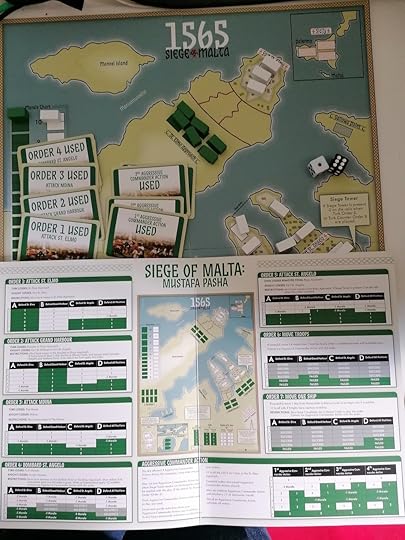

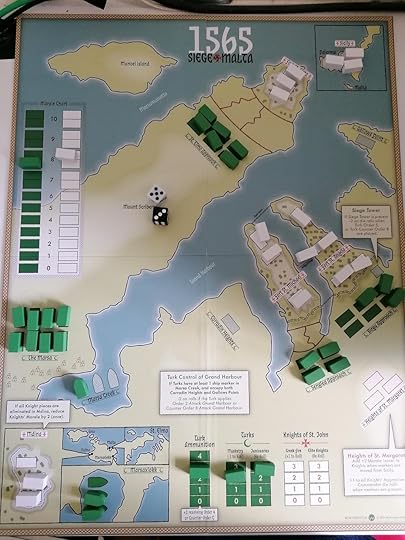

1565 Siege of Malta kind of forces you into a hybrid plan through its action menu. As the Ottoman player you’ll be attacking both Mdina and St Elmo pretty regularly. The mechanics do push you a little towards focusing on one of those two first before going for the harder to capture Senglea and Birgu, but in general you’re forced to spread your actions so wide that it never quite captures the specific focus of the main Ottoman army on one position at a time.

Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most robust version of this challenge with its small deck of Ottoman strategy cards – definitely my favourite solution to this challenge.

None of the games include Gozo as a playable space, so the control of the smaller island is entirely ignored.

The second aspect of Ottoman leadership is the conflict between the main leaders throughout the siege. None of the games really capture this clash of personalities, but it would also be hard to do it without making the Ottoman side more than one player. It’s very hard to force a single player into debating with themself what to do next. St Elmo’s Pay does make the decision to single out Mustapha as the clear leader since he is the permanent leader whose death causes the Ottoman player to lose while Piali is just a card in the deck. I think this works against the history of the siege a bit; I think I would have preferred if instead the Ottomans had two Leader cards they had to juggle somehow. This bothers me less as something missing from the games, though, since many games have to abstract away conflicts in leadership and present a more unified front than was historically the case for ease of play.

Valette’s Resource ManagementThe Hospitallers and their allies were desperately outnumbered in the siege and relied upon their superior defensive position to resist the might of the Ottoman army. They also had to spread their forces over four main locations: Fort St Elmo, Birgu, Senglea, and Mdina. This created a significant strategic challenge in terms of deciding how to distribute their forces. In particular, during the siege of Fort St Elmo Valette had to decide how many soldiers he could afford to send over to the fort knowing that most if not all of them would not return. As the siege dragged on and became more desperate the need to retain control for as long as possible had to be weighed against the limited supply of troops that had to last for the whole siege. This is something I desperately want to see portrayed in any game where I control the Hospitallers – to my mind it is one of the essential decisions facing the defenders of Malta.

To a degree all three games include this decision. Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross as the most complex game unsurprisingly includes the most elaborate and robust version of troop positioning and movement between the locations. 1565 Siege of Malta includes movement of troops between locations as one of the Hospitaller actions but with the relatively low difficulty of playing as the Christians I didn’t feel like I was under pressure to use it all that often.

St Elmo’s Pay has a system for moving units between the three locations, but it doesn’t capture that feeling of being outnumbered as the Christians and having to spread limited resources between the locations. The Ottomans are slightly better at putting out more cards, but with the limit of three cards per a frontier and the generally greater strength of the Christian cards you don’t feel like you’re outnumbered two to one. The fact that strength values at all three Frontiers are resolved simultaneously every round makes it harder to ask the Christian player to prioritise one Frontier the other two. It’s understandable, but again it feels like a legacy of the fact that the system was originally designed for a battle not a siege. In a battle all three wings would fight simultaneously while at a siege like Malta the Ottomans had to prioritise where they were putting their main attack.

The Weight of Time

The Siege of Malta had a massive clock hanging over it the entire time. Unlike with the earlier Siege of Rhodes the Ottomans couldn’t realistically spend the winter in Malta – resupplying by sea would be too difficult and there was nowhere near enough food on the island. They would also be much more exposed, and in the spring a Christian relief force could easily arrive from Sicily well before any reinforcements could come from Constantinople. That meant that they had to take the island before the weather turned and prevented a return voyage to Constantinople. This gave a realistic end date to the siege as sometime in September. Every delay and each setback created more tension for the Ottoman commanders – they may have had more resources, but they didn’t have more time.

The second ticking clock was the Christian relief force. An army was slowly mustering in Sicily throughout 1565. Don Garcia, the commander appointed by Spanish King Philip II, refused to sail for Malta until he had a large enough force to present overwhelming opposition to the Ottomans. He needed a large enough fleet to guarantee that he could break through the Ottoman blockade and then once he landed, he needed a large enough army that it could drive the Ottoman’s off the island. Landing a small force ran the risk of it being entirely wiped out, providing supplies and a morale boost to the Ottomans instead of helping the besieged Christians. Don Garcia also had to weigh the fears Philip II had of an Ottoman or Barbary attack elsewhere in the Mediterranean – if he committed his army to Malta would he expose himself to attack somewhere else? What if he lost is fleet trying to relieve Malta, crippling his kingdoms defences for no gain?

This relief force was a clock for both sides – the Christians were desperate for it to muster and sail while the Ottomans needed it to hit as many delays as possible and to keep up their strength to oppose it should it land. Historically Don Garcia didn’t recruit an army equal in size to the Ottoman’s but by the time he arrived at the start of autumn the Ottomans were so tired and demoralised, and had lost many of their best soldiers, that his smaller but well rested army was more than up to the task of driving them off.

St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t really include any of the temporal elements. There’s no separate tracking of the Sicilian relief force and no clock ticking away forcing the Ottomans to be more aggressive.

1565 Siege of Malta does quite a good job at both of these clocks. The Sicilian Relief arguably arrives a little too quickly – or at least potentially can since it’s based on random card draws – but it certainly includes a system for the slow mustering and then eventual arrival of the relief. One of the things I liked most about 1565 Siege of Malta was how the event deck was used to track victory, the Ottomans lose if it runs out while the Christians win, making the experience of playing the Ottomans a race against the deck while the Christians just want to survive until the last card is done.

Unsurprisingly, Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most complex systems for modelling both of these. It includes 20 individual weeks, and near the end the Ottomans must roll to see if they leave the island. Similarly, there are rules for the eventual arrival of the Sicilian relief force (although I did not get far enough in my game to play with them), and the game can end in a Final Battle phase where both players see if the relief was enough or if the Ottoman’s can emerge victorious despite the strain of the siege. This is by far the most elaborate representation of the clock, and I love it, but it of course comes a the cost of many more rules and a much longer game.

Dramatic Events

The final element I think is essential to capturing the Siege of Malta is some way to incorporate the dramatic events that marked certain points in the siege. To me there are four specific moments and three more generic, recurring events that should be included in some form in the game.

The four specific events are:

1. The dragging of Ottoman ships over Mount Scibberas to launch a combined assault on Birgu and Senglea – and then the dramatic defence against the odds in the face of the combined assault.

2. The death of Turgut and the threat to the lives of the other leaders

3. The piccolo soccorso, or “small relief”, the force of approximately six hundred soldiers who snuck across Malta in the wake of the Ottoman capture of St Elmo and were ferried into Birgu in the nick of time.

4. The cavalry raid out of Mdina into the Ottoman camp during one of the last dramatic assaults on Birgu and Senglea, which was mistaken for the arrival of the main relief force and caused the collapse of the Ottoman attack just when it might finally have succeeded.

In addition to the four above I would like for the game to capture the attempts to undermine the walls, particularly Birgu and Senglea, the endless barrages of the Christians by Ottoman artillery, and the many dramatic last stands where Christian forces who should have been wiped out somehow survived to fight another day.

1565 Siege of Malta has most of the above elements, although I did complain in my review that it felt like the big one-off events (specifically boats over Mt Scibberas and cavalry raid out of Mdina) happened far too often. It doesn’t really have leader death, it’s not that granular in its representation of the two sides, and there’s no piccolo soccorso. It does have bombardment and dramatic attacks on the Christian positions, but not really any system for mining.

St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t do this particularly well. It has artillery cards which represent the bombardment in an interesting way, but you aren’t guaranteed that they’ll show up and play a major role in your game. Same thing with cards for miners. Lots of cards represent characters who can die, but Turgut may never show up (he hasn’t in my games) so his death can hardly be a major event in the siege in most games. It does have the auto-loss if Mustapha or Valette die but that’s kind of the opposite of what I want since it ends the game. I want to see the fallout of that death and have to cope with it. Things like the dragging of the boats, Mdina cavalry attack, and piccolo soccorso don’t fit into the games structure. There are cards for Mdina cavalry and Ottoman ships, but they persist until killed, not as one dramatic attack.

As the most complex and granular game, it’s no surprise that Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most detail for all of these. There are rules for the piccolo soccorso and event cards can cause the dragging ships over Mt Scibberas and the cavalry attack from Mdina. All of the leaders run the risk of death, although interestingly only through Christian card play. Christian events can be used to try and kill all the Muslim leaders, but Valette can only be killed by dramatically coming to the defence against an Ottoman attack, a choice the Christian player makes. Bombardment and dramatic pitched fights play a major role in the game and there are rules for mining, although they are quite simple, and they didn’t come up in my short demo game.

ConclusionThis post isn’t intended to be a review, I already wrote what I thought about each of the individual games. Instead, it is an exploration of the historic siege and what I, in my humble opinion, think are the most important and interesting elements to convey in a game about the siege. These opinions are what have led me to preferring Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross to the other two, but obviously the designers of 1565 Siege of Malta and St Elmo’s Pay have different ideas of what is important when portraying the siege. Which is fine! Hopefully this has been at least an interesting exploration of the topic. If you have different opinions about what you want to see of the siege represented in games, then hopefully it has also provided you some guidance in picking a game for you.

Playing the Siege of Malta

Having now played multiple games on the 1565 Siege of Malta I wanted to take a minute to think about what I’m looking for in a game about the siege and to reflect a bit on how each of the games I played portrays this historical event. I’ve tried to outline several of the key elements or events of the historical siege that I want a game to incorporate in some form. I will discuss why I think they’re important and how each game approaches them. This is not meant to be a critique of the games – if you want my opinions on playing them you should check out the individual posts on each game (easily found via this linke: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/category/Malta+Month) –instead it is more of a (highly subjective) study of how the siege is portrayed in wargaming.

I should also put as a disclaimer here that there is one game about the Siege of Malta that I haven’t played: Knights of Justice a magazine game published in Wargamer Magazine #50 in 1986. Copies of this are hard to come by so I wasn’t able to play it this month. However, I have found someone who can share their copy with me, but not until they have access to their storage in a few months’ time. When I do get a chance to play it, I’ll write up some general thoughts for a much belated Malta Month post and I may revisit this post then to incorporate the final Malta game.

With the context all settled, let’s jump into the history of the siege and what elements I think are important to capture in a game about it. If you haven’t already, I would definitely recommend reading my summary of the events of the siege I posted at the start of the month. It will provide valuable context and can be read here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/cutting-room-floor-malta

Ottoman LeadershipThroughout the Siege of Malta the Ottoman leadership was seriously fragmented. Mustapha Pasha was commander of the ground forces while Piali Pasha commanded the navy – in theory anyway. Mustapha had been placed in overall command by Suleiman, but Piali had married into the Sultan’s family and had a more powerful position in the Ottoman court, making for an awkward balance of power from the start. At the same time, they had both been instructed to listen to what Turgut, the lord of Tripoli and an effective Barbary pirate with a notorious reputation, had to say in all matters. Turgut was also in direct command of the Barbary corsairs, since they would only listen to him, and had the most experience and prestige, making him a third potential commander. The disputes between the three commanders, two after Turgut was killed by a misfired cannon, created plenty of tension during the campaign.

The first, and to my mind most important, point of contention was how to start the siege. Piali Pasha proposed the plan that was eventually implemented, which was to take Fort St Elmo first and then attack Birgu and Senglea. This was because Piali wanted to moor his fleet in the bay north of Mount Scibberas which wasn’t possible as long as Fort St. Elmo still stood. Mustapha wanted to secure the small island of Gozo and then the capitol city of Mdina before turning on the Hospitaller positions around the Grand Harbour. Turgut preferred Mustapha’s plan but was too late to support his argument, Piali’s plan having already been implemented by the time Turgut arrived.

Mustapha’s plan may have succeeded where Piali’s failed so one of the things I’m interested in is how a game can model the counterfactual of what if the Ottomans had chosen a different course of action.

1565 St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t include this at all – there is no option for battling over Mdina so the only plan to enact is Piali’s.

1565 Siege of Malta kind of forces you into a hybrid plan through its action menu. As the Ottoman player you’ll be attacking both Mdina and St Elmo pretty regularly. The mechanics do push you a little towards focusing on one of those two first before going for the harder to capture Senglea and Birgu, but in general you’re forced to spread your actions so wide that it never quite captures the specific focus of the main Ottoman army on one position at a time.

Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most robust version of this challenge with its small deck of Ottoman strategy cards – definitely my favourite solution to this challenge.

None of the games include Gozo as a playable space, so the control of the smaller island is entirely ignored.

The second aspect of Ottoman leadership is the conflict between the main leaders throughout the siege. None of the games really capture this clash of personalities, but it would also be hard to do it without making the Ottoman side more than one player. It’s very hard to force a single player into debating with themself what to do next. St Elmo’s Pay does make the decision to single out Mustapha as the clear leader since he is the permanent leader whose death causes the Ottoman player to lose while Piali is just a card in the deck. I think this works against the history of the siege a bit; I think I would have preferred if instead the Ottomans had two Leader cards they had to juggle somehow. This bothers me less as something missing from the games, though, since many games have to abstract away conflicts in leadership and present a more unified front than was historically the case for ease of play.

Valette’s Resource ManagementThe Hospitallers and their allies were desperately outnumbered in the siege and relied upon their superior defensive position to resist the might of the Ottoman army. They also had to spread their forces over four main locations: Fort St Elmo, Birgu, Senglea, and Mdina. This created a significant strategic challenge in terms of deciding how to distribute their forces. In particular, during the siege of Fort St Elmo Valette had to decide how many soldiers he could afford to send over to the fort knowing that most if not all of them would not return. As the siege dragged on and became more desperate the need to retain control for as long as possible had to be weighed against the limited supply of troops that had to last for the whole siege. This is something I desperately want to see portrayed in any game where I control the Hospitallers – to my mind it is one of the essential decisions facing the defenders of Malta.

To a degree all three games include this decision. Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross as the most complex game unsurprisingly includes the most elaborate and robust version of troop positioning and movement between the locations. 1565 Siege of Malta includes movement of troops between locations as one of the Hospitaller actions but with the relatively low difficulty of playing as the Christians I didn’t feel like I was under pressure to use it all that often.

St Elmo’s Pay has a system for moving units between the three locations, but it doesn’t capture that feeling of being outnumbered as the Christians and having to spread limited resources between the locations. The Ottomans are slightly better at putting out more cards, but with the limit of three cards per a frontier and the generally greater strength of the Christian cards you don’t feel like you’re outnumbered two to one. The fact that strength values at all three Frontiers are resolved simultaneously every round makes it harder to ask the Christian player to prioritise one Frontier the other two. It’s understandable, but again it feels like a legacy of the fact that the system was originally designed for a battle not a siege. In a battle all three wings would fight simultaneously while at a siege like Malta the Ottomans had to prioritise where they were putting their main attack.

The Weight of Time

The Siege of Malta had a massive clock hanging over it the entire time. Unlike with the earlier Siege of Rhodes the Ottomans couldn’t realistically spend the winter in Malta – resupplying by sea would be too difficult and there was nowhere near enough food on the island. They would also be much more exposed, and in the spring a Christian relief force could easily arrive from Sicily well before any reinforcements could come from Constantinople. That meant that they had to take the island before the weather turned and prevented a return voyage to Constantinople. This gave a realistic end date to the siege as sometime in September. Every delay and each setback created more tension for the Ottoman commanders – they may have had more resources, but they didn’t have more time.

The second ticking clock was the Christian relief force. An army was slowly mustering in Sicily throughout 1565. Don Garcia, the commander appointed by Spanish King Philip II, refused to sail for Malta until he had a large enough force to present overwhelming opposition to the Ottomans. He needed a large enough fleet to guarantee that he could break through the Ottoman blockade and then once he landed, he needed a large enough army that it could drive the Ottoman’s off the island. Landing a small force ran the risk of it being entirely wiped out, providing supplies and a morale boost to the Ottomans instead of helping the besieged Christians. Don Garcia also had to weigh the fears Philip II had of an Ottoman or Barbary attack elsewhere in the Mediterranean – if he committed his army to Malta would he expose himself to attack somewhere else? What if he lost is fleet trying to relieve Malta, crippling his kingdoms defences for no gain?

This relief force was a clock for both sides – the Christians were desperate for it to muster and sail while the Ottomans needed it to hit as many delays as possible and to keep up their strength to oppose it should it land. Historically Don Garcia didn’t recruit an army equal in size to the Ottoman’s but by the time he arrived at the start of autumn the Ottomans were so tired and demoralised, and had lost many of their best soldiers, that his smaller but well rested army was more than up to the task of driving them off.

St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t really include any of the temporal elements. There’s no separate tracking of the Sicilian relief force and no clock ticking away forcing the Ottomans to be more aggressive.

1565 Siege of Malta does quite a good job at both of these clocks. The Sicilian Relief arguably arrives a little too quickly – or at least potentially can since it’s based on random card draws – but it certainly includes a system for the slow mustering and then eventual arrival of the relief. One of the things I liked most about 1565 Siege of Malta was how the event deck was used to track victory, the Ottomans lose if it runs out while the Christians win, making the experience of playing the Ottomans a race against the deck while the Christians just want to survive until the last card is done.

Unsurprisingly, Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most complex systems for modelling both of these. It includes 20 individual weeks, and near the end the Ottomans must roll to see if they leave the island. Similarly, there are rules for the eventual arrival of the Sicilian relief force (although I did not get far enough in my game to play with them), and the game can end in a Final Battle phase where both players see if the relief was enough or if the Ottoman’s can emerge victorious despite the strain of the siege. This is by far the most elaborate representation of the clock, and I love it, but it of course comes a the cost of many more rules and a much longer game.

Dramatic Events

The final element I think is essential to capturing the Siege of Malta is some way to incorporate the dramatic events that marked certain points in the siege. To me there are four specific moments and three more generic, recurring events that should be included in some form in the game.

The four specific events are:

1. The dragging of Ottoman ships over Mount Scibberas to launch a combined assault on Birgu and Senglea – and then the dramatic defence against the odds in the face of the combined assault.

2. The death of Turgut and the threat to the lives of the other leaders

3. The piccolo soccorso, or “small relief”, the force of approximately six hundred soldiers who snuck across Malta in the wake of the Ottoman capture of St Elmo and were ferried into Birgu in the nick of time.

4. The cavalry raid out of Mdina into the Ottoman camp during one of the last dramatic assaults on Birgu and Senglea, which was mistaken for the arrival of the main relief force and caused the collapse of the Ottoman attack just when it might finally have succeeded.

In addition to the four above I would like for the game to capture the attempts to undermine the walls, particularly Birgu and Senglea, the endless barrages of the Christians by Ottoman artillery, and the many dramatic last stands where Christian forces who should have been wiped out somehow survived to fight another day.

1565 Siege of Malta has most of the above elements, although I did complain in my review that it felt like the big one-off events (specifically boats over Mt Scibberas and cavalry raid out of Mdina) happened far too often. It doesn’t really have leader death, it’s not that granular in its representation of the two sides, and there’s no piccolo soccorso. It does have bombardment and dramatic attacks on the Christian positions, but not really any system for mining.

St Elmo’s Pay doesn’t do this particularly well. It has artillery cards which represent the bombardment in an interesting way, but you aren’t guaranteed that they’ll show up and play a major role in your game. Same thing with cards for miners. Lots of cards represent characters who can die, but Turgut may never show up (he hasn’t in my games) so his death can hardly be a major event in the siege in most games. It does have the auto-loss if Mustapha or Valette die but that’s kind of the opposite of what I want since it ends the game. I want to see the fallout of that death and have to cope with it. Things like the dragging of the boats, Mdina cavalry attack, and piccolo soccorso don’t fit into the games structure. There are cards for Mdina cavalry and Ottoman ships, but they persist until killed, not as one dramatic attack.

As the most complex and granular game, it’s no surprise that Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross has the most detail for all of these. There are rules for the piccolo soccorso and event cards can cause the dragging ships over Mt Scibberas and the cavalry attack from Mdina. All of the leaders run the risk of death, although interestingly only through Christian card play. Christian events can be used to try and kill all the Muslim leaders, but Valette can only be killed by dramatically coming to the defence against an Ottoman attack, a choice the Christian player makes. Bombardment and dramatic pitched fights play a major role in the game and there are rules for mining, although they are quite simple, and they didn’t come up in my short demo game.

ConclusionThis post isn’t intended to be a review, I already wrote what I thought about each of the individual games. Instead, it is an exploration of the historic siege and what I, in my humble opinion, think are the most important and interesting elements to convey in a game about the siege. These opinions are what have led me to preferring Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross to the other two, but obviously the designers of 1565 Siege of Malta and St Elmo’s Pay have different ideas of what is important when portraying the siege. Which is fine! Hopefully this has been at least an interesting exploration of the topic. If you have different opinions about what you want to see of the siege represented in games, then hopefully it has also provided you some guidance in picking a game for you.

August 18, 2022

Conquest by Juliet Barker

There aren’t a lot of books in English that focus on the end of the Hundred Years War. I suppose there has generally been little interest in revisiting the collapse of English rule in France when there are more glorious times to focus on. Most histories tend to skip forward abruptly after the arrival of Joan of Arc directly to the end of the war, skipping over many important developments in the process. Thankfully there are a few historians that have decided to make a closer study of the period from 1417-1453. Conquest by Juliet Barker focuses just on the war in Normandy, covering the period from Henry V’s conquests starting in 1417 until the collapse of English rule in the Duchy and it’s total reconquest by the French monarchy in 1450. It is well researched and is a much-needed study of this period, but I have mixed feelings on the book as a whole.

Let’s start with the good stuff. Conquest is very thoroughly researched. Barker has made an extensive study of the period and provides an in-depth and detailed narrative of both the major and minor events across over three decades of Anglo-French history. If you wanted a thorough breakdown of what happened – how did the English take control of Normandy and several of its neighbouring counties and then lose it all – Conquest absolutely delivers on that. It was very useful in helping me clarify the timeline on several key events and in identifying some of the less famous figures involved in both conquests of Normandy.

It's also well written – the narrative is clear and easy to follow. While I’m not new to this subject and therefore not necessarily the best judge, I still think that most people could pick up this book and follow it without needing much background in the Hundred Years War as a whole. Having that background is always better and I wouldn’t recommend this as a first book on the subject, but if you already have a copy, you could read it without having that broader context. Writing narrative history is challenging, especially narratives with as many moving parts as the Hundred Years War, so Barker must be praised for how well she manages it. The narrower focus on Normandy helps, there’s no effort to include events in Gascony, which reduces the cognitive load in terms of participants and events.

All that having been said, I would have some reservations about recommending Conquest to general readers. The first and, to me personally anyway, most frustrating issue with the book is the very English nationalist perspective that runs throughout the narrative. This may be the most nationalist history of the Hundred Years War I’ve yet read. What’s particularly odd is that the book is still thoroughly researched and many of the core facts are presented in an even-handed manner, it’s just the interpretation that has a strong English bias. This can create odd moments of cognitive dissonance where the interpretation seems to be strongly at odds with the evidence presented by the same book. Let me use an example.

One of Barker’s more interesting points is the way she shows how the Treaty of Troyes, far from securing a long-term peace actually undermined any effort to resolve the Hundred Years War in its later years. For those who may not know, the Treaty of Troyes was signed in 1420 and in it the future Charles VII, then Dauphin or crown prince of France, was disinherited and Henry V was made King Charles VI’s heir in his place. The treaty also cemented the alliance between the Duke of Burgundy and the English and outlined several principles restricting peace negotiations with the disinherited Dauphin. Famously, Henry V died before Charles VI and passed the claim to the inheritance of the French throne to his son Henry VI. What Barker does an excellent job of showing is how the terms of the Treaty of Troyes, along with the later crowning of Henry VI as King of France in Paris – an act orchestrated by Henry’s brother the Duke of Bedford in his capacity as regent but largely in line with Henry’s original wishes – completely undermined any attempt to make peace in the 1430s and 1440s. The English regency, and then later Henry VI when he came of age, couldn’t make peace without conceding that the terms of the Treaty of Troyes were illegitimate. These acts had locked in their claim to the title of King of France and that claim had been used to justify all the conquest and war that had followed – to make peace with the Dauphin would be to declare all those actions illegal and immoral. This created significant stumbling blocks in peace negotiations and created an environment where the only real option was war, a war the English eventually lost.

All of that analysis is fascinating and provides a great perspective on what is often seen as Henry V’s greatest diplomatic triumph. However, Barker also doesn’t take the logical next step and question whether Troyes really was all that good of a treaty. Was it a diplomatic coup achieved by Henry V in his prime or was it an ill-conceived power grab that burdened his kingdom and his son and would eventually lead to social collapse and Civil War? Much of the evidence in the book seems to argue the latter but Barker cannot help but argue an aggressively pro-Henry V line in which he can have done no wrong. The failures are all in how the successors failed to overcome the flaws in the Treaty of Troyes, not in Henry’s original plan.

A similar problem can be seen in how Barker wants to blame both sides for the breaking of the Truce of Tours and the resumption of the war in 1449. The evidence as documented in the book is damning for the English and shows a French monarchy presented with the perfect opportunity to win the war and choosing to take it. The need to paint the English in a good light at times results in criticising the French for making sound decisions that benefit them because they don’t fit the author’s seemingly arbitrary concept of what was or was not chivalrous. This serves to undercut the book and made it a frustrating read.

Conquest also suffers from many of the issues that I have with narrative history more generally. Narrative history can be very engaging and it’s a useful type of history to have, but it can also be done in a fashion that is far too narrow. I found Conquest to be long in narrative and short in broader analysis. It did a lot to tell me what happened but didn’t do nearly enough to tell me why it happened. This to me is the flaw in narrow narrative history. Answering the why is an important part of historical analysis and I just didn’t feel there was enough of it in Conquest. I could have done with a little less in terms of detailed descriptions of minor border skirmishes and instead some explanation of what these border skirmishes meant and what they tell us more broadly about Anglo-French conflict during this period.

My other criticisms are much more minor. I appreciate that Barker is just focusing on Normandy and that the book is long enough as is, but it really would have benefited from providing some context for what was going on in Gascony as well. French campaigns in Gascony only appear in the narrative very rarely, and the end of the book pretty strongly implies that the war ended in 1450 with the fall of Cherbourg – completely ignoring the fact that fighting in Gascony continued until 1453. It’s not a damning flaw, but it is somewhat misleading particularly if you’re not already familiar with the subject.

I also have mixed feelings about her analysis of the financing of the war. This is more an issue of presentation rather than research. Barker has clearly done a lot of work researching how much the various campaigns cost and presents very detailed information on it throughout the book. What I think is missing is context and, in a few places, analysis. I couldn’t help but contrast this with Jonathan Sumption’s Trial by Battle (see my review here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/trial-by-battle-by-jonathan-sumption). I think Sumption did a much better job at contextualising the immense financial burden of the campaigns of the 1340s. Barker presents you with the evidence showing how expensive campaigning was and the increasing difficulties the English faced in meeting those demands but she never seems to take a moment to explain that these costs were unsustainable. I think this feeds back a bit into the nationalist perspective of the book – to admit that the English couldn’t afford to wage the war would be to admit that the war was unwinnable, something she cannot bring herself to do. As a result, it feels like a layer of analysis is missing from the book. The research has been done and readers can draw their own conclusion, but it would have benefited from a more explicit exploration of the topic.

Overall, while Juliet Barker’s Conquest is a very valuable history covering an important part of the Hundred Years War that doesn’t receive enough attention, I’m not sure if I would recommend it to most readers. Only die hard Hundred Years War enthusiasts or those with a special interest in the war during the fifteenth century should really read it. For most readers I would recommend A.J. Pollard’s John Talbot and the War in France instead (my review here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/john-talbot-and-the-war-in-france-by-aj-pollard).

August 15, 2022

[Malta Month] Preview: Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross by Andy Loakes

Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross (WCSC) is by far the most complex game about the Siege of Malta that I’ve played. This is not a light game to be played in less than an hour. Instead, it is nothing less than the full siege in all its violent glory to be re-enacted over hours of gameplay. WCSC is still in development and Legion Wargames helpfully put me in touch with designer Andy Loakes. Andy kindly shared the draft rules and Cyberboard module being used for playtesting and was even more generous by spending four hours across two weekends to walk me through the game. In that time, we played approximately three weeks of the siege. A full game can last for twenty. That should give some indication of the scale of this experience. I have to say, though, that I had a blast and was engaged the entire time. This is a fascinating game, and I can’t wait to see how it turns out in its final published form.

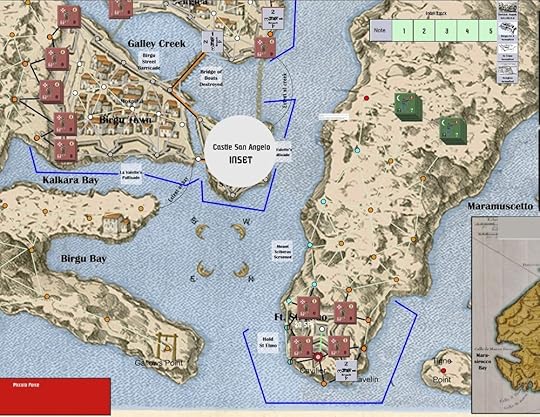

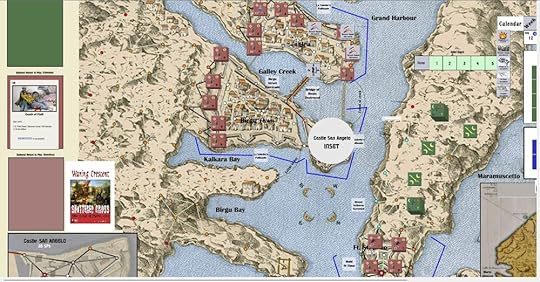

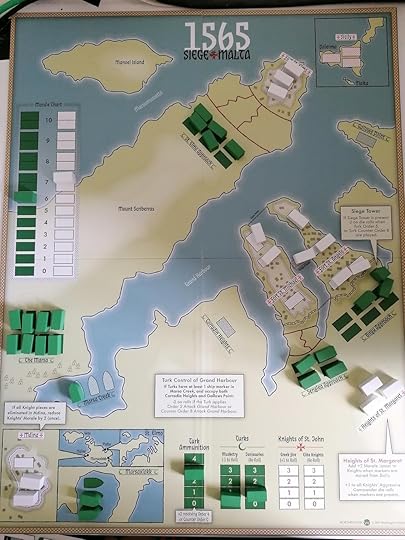

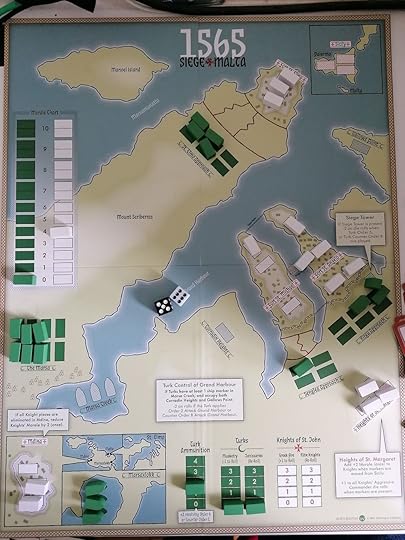

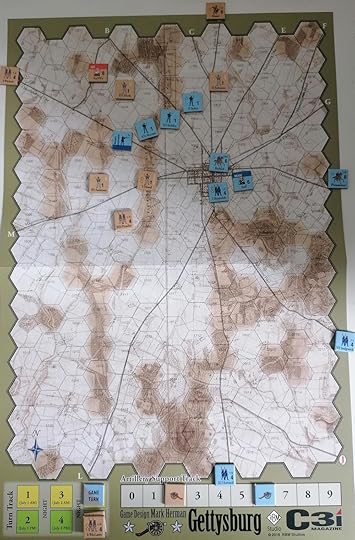

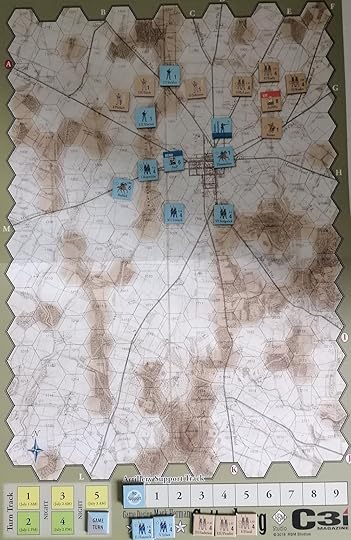

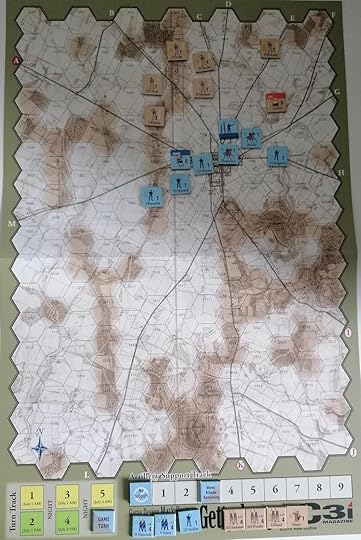

WCSC is very much a game of geography. The main board of WCSC is a point-to-point map of the Grand Harbour including Senglea, Birgu and St Elmo. In the top right corner is a pile of tracks for things like morale, honour, and Ottoman supply. There are also two inset boxes for Mdina and Fort St Angelo. At first read I found the rules for the map quite intimidating. The points are in a variety of colours each with their own rules. Upon playing it, however, I found it quite intuitive. The red points at the edges of the map are where the Ottoman armies can enter play, grey points on top of fortifications obviously represent fortified positions, etc. A few have some specific special rules, for example a series of light blue points along Mt Scibberas are important for establishing whether the Ottomans are screening the harbour preventing the reinforcement of St Elmo, but those only need to come in to play in certain circumstances.

I couldn’t fit the entire board into one image on Cyberboard on my monitor, but here’s the main parts - the three forts and the insets of Mdina and Fort St Angelo. I should also stress that these are all playtest graphics - none of this is is final art!

That really is my impression of the game as a whole: it looked very intimidating at first but was much less complicated than I expected. Don’t get me wrong, this is still by far the most complex game I played this month, but I would say that it’s probably medium complexity for a wargame. There are still a lot of elements to keep track of, such as multiple unit types and the aforementioned tracks, and I expect when playing the final version I will want the rulebook by my side for referencing, but the core gameplay loop is relatively straightforward. On your turn you either play cards for their events or you discard them to take one of a number of actions – usually moving stacks of troops, bombarding walls, making missile attacks on enemy troops, or initiating melee combat. It’s not what I would call simple, but if you’ve played a card driven wargame before a lot of it will be familiar. Even the length, while still impressive, is probably not as bad as my initial play would indicate. Obviously, I was still learning the game and the difficulty of using Cyberboard, a play by email platform, to live play definitely slowed us down a bit, but also the game will probably speed up as you play for reasons I’ll get into later.

But enough of the more generic wargame-y elements of WCSC, let’s get to the good stuff! How does this game model the Siege of Malta specifically? The short version is amazing well, the long version is coming up, so I hope you’re ready!

The Ottomans are tasked with attacking Fort St Elmo first and so deploy two stacks of troops onto the peninsula. Your opponent can only see what is on top of the stack, which creates a subtle fog of war that reveals itself as you fight.

One of the challenges I had long thought would be difficult for a game about the Siege of Malta was how to represent the divisions within the Ottoman strategy. Piali and Mustapha disagreed on the best approach of how to take Malta. Piali’s plan eventually won out despite arguably being the worse option, and history has shown it to have been ultimately unsuccessful. When designing an epic game about the siege how do you account for this? If Piali’s strategy is worse, do you still force the player to execute it or do you design a game where Mustapha’s plan is more viable but risk players never choosing the historic option? The solution in WCSC is so simple I almost feel stupid for how long I’ve been thinking about this question. The Ottoman player is secretly dealt a card from a deck of six which outlines the plan that has been chosen. This deck is weighted in favour of the historic plan but includes two alternatives. The plan takes the form of instructions on the order certain parts of the island must be taken in, e.g. the historic plan requires the taking of St Elmo before assaulting anywhere else. However, the player is not obliged to follow this plan, they can do whatever they want but if they fail to fulfil its requirements, they will lose honour at the end of the game and honour is worth victory points. Players can then choose – if you don’t like the strategy do you discard it in favour of an alternative and just hope that your new plan is effective enough to make up for those lost points? This kind of careful thinking really underpins a lot of the game and it’s what makes it such an interesting representation of the siege.

For our game we played the historic strategy, partly because it is the classic scenario and in part because it largely ignores Mdina. This latter point is important because the rules for sieging Mdina, which are much more abstracted than the other locations, are being significantly revised and tested and it was simpler for our demo game if we just left it alone. I am very much looking forward to seeing how they develop in the final game, though.

The Ottoman attack begins - this may look quick but it took me three cards to move this far as I could only move one point each turn. However, I placed Ottoman control markers behind me which means that any troops that follow my path can move across those spaces for free - I’ve secured ground making it easier to bring more troops forward.

I found the core gameplay of each turn really engaging and as the Ottoman player I thought Andy did a great job of capturing the feeling of not having enough time to prosecute the siege. Starting with the Ottoman player, players take it in turns to first draw as many cards as they want and then to play as many cards as they want to take actions. Once a player has run out of cards or passes then their opponent repeats the process. There are two very important wrinkles that make this system work. The first is that you can’t draw any more after you start playing cards, so you can’t draw a card, play it, draw another, etc. The second is the End of Week cards.

Bringing the second set of Ottoman troops forward was much faster. I then entrenched both forces - a necessary stage before I could begin bombarding the walls with my basilisk and my cannon. The Ottomans have a limited amount of artillery to bring to bear, and if they are captured by a Christian counter attack I could lose them forever so I don’t want to risk exposing them any more than necessary. Walls can be Breached on a level between 1 and 8 - you need to create a very large breach to attack between and until they are nearly totally destroyed the Christians can try and repair them.

If the Ottoman player draws an End of Week card, then an End of Week phase must be resolved, including both players discarding down to 4 cards in hand and shuffling the discard back into the deck. More importantly, though, is that the tracker representing the progress of the siege moves forward one week – bringing it slowly closer to its conclusion. This creates an element of push your luck as the Ottoman Player obviously wants a lot of cards in hand to have a big turn but must avoid those End of Week cards. Some cards are removed from the deck permanently through play over the course of the game, so as the game progresses the deck will become thinner, and those End of Week cards are likely to come up more often. This gives the game the potential to accelerate towards its conclusion in the later weeks.

The Christian player also wants to avoid End of Week cards to some extent – only End of Week cards marked with a Maltese cross affect them, so the chances of triggering an End of Week are lower for them. Still, because the Ottoman player always go first drawing End of Week causes both players to potentially discard cards and then play switches back to the Ottomans. The Christian End of Week also doesn’t progress the week tracker, though, so the Christian player can’t just keep drawing cards to try and accelerate the end of the game.

In addition to pushing the temporal element of the siege to the front and centre in the gameplay, the End of Week cards also represent an interesting element of the historic siege. Some weeks not very much seems to have happened. Successfully prosecuting a siege is a logistical nightmare and some weeks the Ottomans just got bogged down and didn’t get very much done This mechanic creates some great tension in planning your strategy and captures that ebb and flow of a massive siege like Malta.

End of the First Week, some serious bombardment has happened but it still feels like I didn’t do enough given how few weeks it feels like I have. I also managed to increase Ottoman intelligence (track above Mt Scibberas approach) due to the Christians resupplying Fort St Elmo - this is one of two necessary elements to allowing me to screen the harbour and prevent any future reinforcement of the fort.

Combat is also utterly lethal in ways I found very interesting. Ranged combat seems to be more of a mixed bag, taking pot shots with arquebuses keeps your troops relatively safe but may not inflict much harm - particularly for the Ottomans shooting at the more heavily armoured Christians. The real meat of the fighting is in melee – storming walls if you’re the Ottomans or pushing attackers back out of breaches if you’re the Christians. Combat resolution is done via a relatively straightforward Combat Results Tables (CRT) with column shifts based on a number of factors. I’m honestly not much of a fan of CRTs. I like the immediacy of being able to determine results just from the dice, but it’s impossible to get the same level of detail out of a dice only system. I appreciate that the CRTs for WCSC are relatively light on modifiers – you won’t find yourself having to calculate six different elements all of which slightly impact the roll. Instead you work out the rough ratio of troops and then check a few modifiers that cause column shifts. Once you’ve determined the relevant column both players roll using the Attacker and Defender results within that column.

The Ottoman assault on Fort St Elmo begins…kind of. I actually used an Event to displace the Christian troops on that wall section and just marched into the breach - but technically I did start the assault. Now if I fail to take the fort within 5 weeks I will risk losing Morale - this was supposed to be a cakewalk. I’m also limited in how many troops can occupy a Breach so only a fraction of my stack has moved forward.

What I really appreciate is how dangerous combat is for everyone involved. Even on the most unbalanced CRT column, a 5:1 ratio in favour of the attacker, the defender will still inflict casualties 50% of the time. I also really like the system for determining the size of a combat. You calculate the size of the smaller force in terms of overall strength points, i.e. how many troops are present, and that determines how many dice are rolled in combat for both sides. This means that the bigger the fight the more casualties on both sides. I haven’t played enough games to know if this is fairly standard in more complex games with CRTs but it was new to me and I think does a great job of capturing the carnage of combat during the Siege of Malta. In our first combat in a breach my Ottomans were decisively driven back, suffering twice as many casualties as I inflicted – but at the same time I had twice as many troops to lose and I removed one Strength Point worth of Hospitallers (representing approximately 50 knights) to the Walking Wounded chart. These units are in short supply on the Christian side so I probably came out ahead despite my higher losses. This moment felt like the siege to me, throwing away troops I didn’t care about (no Janissaries were included in this assault, I risk losing honour should they retreat from an attack) to grind down the Christians much more limited supply of men.

The Christian counter attack eliminates my initial attack, but we take some of them with us and troops are more precious to them. You can see on the right where losses are tracked - some losses will return to the battle later as they recover but it is a slow process.

Waning Crescent, Shattered Cross really felt like the ideal distillation of the Siege of Malta. It’s not entirely without its drawbacks. As a complex game that probably takes most of a day to play it’s not something I’d likely get to the table very often, but I don’t think I’d need to. For many people this game will be too big and too long and they will have a much better time with one of the other games I reviewed this month – but for me and what I want out of replaying the 1565 siege this seems like the ideal game and I cannot wait for its eventual release.

August 11, 2022

White Mythic Space: Racism, The First World War, and Battlefield 1 by Stefan Aguirre Quiroga

I think some people might see the title of this book and think it does not have any relevance to them or their interests and that’s too bad because White Mythic Space offers a valuable framework for countless situations beyond just those explored within its pages. This is the kind of book that, if there is any justice, will be referenced for decades to come. It’s a fascinating, well written, and approachable work that expanded my understanding of more subjects than I can readily count. I’m going to try, though, because if I just continue sing it vague praises that do it an injustice and wouldn’t make for a very interesting review.

I want to start with the core theme of the book, and the one that I think will be of use to most people: the idea of the White Mythic Space. Stefan Aguirre Quiroga proposes the concept of subjects which white culture believes to be the unique and exclusive property of a homogenous white identity. Essentially, these are topics, be they fantasy or real history, that large proportions of (primarily white) society believes to only include white people. The topic which is explored for much of the book is the First World War and the erroneous belief that only (or nearly only) white Europeans fought in the trenches of the Western Front. However, this concept is hardly limited to this one historical event. Indeed, elsewhere the author has written about the popular backlash to the inclusion of non-white characters in the animated movie Frozen 2 and non-white actors in the recent Amazon series set in Tolkien’s fictional Middle Earth.

Part of what makes the White Mythic Space particularly interesting, and troubling, is that its beliefs persist even in the face of obvious contrary evidence. The presence of non-white soldiers in Europe during the First World War is well documented and (you would think) indisputable and yet there are thousands of people who are unwilling or unable to accept this reality when presented with it in the form of the video game Battlefield 1’s inclusion of non-white soldiers.

As someone who specialises in medieval history, I can immediately see the applicability of the concept of White Mythic Space beyond modern warfare. Arguably few areas are as much a White Mythic Space as medieval Europe. The degree to which the Middle Ages is seen as a White Mythic Space is so strong that it bleeds into pure fiction – nearly all works of fantasy that happen to include elements of medieval Europe in their world building are also automatically White Mythic Spaces. We see this in objections to casting of non-white actors in worlds created by Tolkien or, as Stefan explores in his book, the casting of Marvel’s Thor movies – movies where the (fictional) Norse gods are aliens from another world and not in fact Scandinavian at all. The concept of White Mythic Space provides a valuable framework for analysing the public backlashes to the inclusion of non-white people in these spaces, or more generally to the denial that non-white people were ever present in medieval Europe, and make no mistake, there were non-white people in medieval Europe. Even in my weird narrow field I have found a Peter the Saracen and Benedict the Moor working as crossbow makers in early 13th century England. While we don’t exactly have photos of these men it is hardly a stretch to suggest that they may not have been white.

White Mythic Space contains more than just the conceptual framework of the White Mythic Space. It also contains a thorough exploration of how it applies to the game Battlefield 1 and the backlash it faced for including non-white soldiers among its cast of characters. The book’s structure deftly interweaves criticism of the game itself – noting that its single player campaign is, despite its promotion, distinctly lacking in non-white stories – with analysis of the intense backlash it faced across multiple internet forums. It expands upon previous work analysing the historical accuracy of videogames to introduce a more specific and much needed discussion of how race factors into understandings of historicity and audience expectations when engaging with historical representation in media.

Stefan also sets Battlefield 1 within two broader contexts. The first is the general representation of WW1 in popular media from the immediate aftermath up to a few years after Battlefield 1’s release. The second is within the more specific context of the centenary celebrations of the war, which aligned with Battlefield 1’s release, and how the game fits within the broader re-evaluation of the conflict that this event spurred. I really appreciated how this contextual information helped enhance my understanding of popular representations of WW1 generally and how they specifically related to the game Battlefield 1 (which, for the record, I have played and found reasonably enjoyable).

There’s just so much to like about this book. I’m far from a specialist on any topic covered in its pages but I was easily able to follow it thanks to the clear writing style and intuitive structure. About the only critique I could level against it is that as an academic book published by an academic press it’s very expensive. That’s barely a critique, but it is what would stop me from saying that you need to go out and buy this book right now. Instead, you should try and convince your nearest library to buy it for you, and then borrow it from them!

August 8, 2022

[Malta Month] 1565: St Elmo’s Pay by Tristan Hall

1565: St Elmo’s Pay is the second game in Hall or Nothing Production’s Historic Epic Battle System. The first game was 1066: Tears to Many Mothers, a game about the Battle of Hastings. Both games are relatively quick playing, 30-40 minutes, card games for 1-2 players. While I haven’t played 1066 there are certainly ways in which this system feels like it originated as a model for a battle rather than a large scale siege like Malta. Capturing the epic scope of the Siege of Malta in just a few decks of cards is a daunting task, but despite its limitations I think St Elmo’s Pay does an admirable (if not exactly perfect) job at representing the siege. Before we get to deep into my thoughts about how well it models the siege, let’s talk about the game some.

The initial set up for the solitaire scenario playing as the Ottomans. I have decided that despite Mustapha’s historic preferences I’ve assigned him to take St Elmo first.

In a game of St Elmo’s Pay each player starts by taking their side’s respective decks which include cards representing characters, generic units, events, and tactics used during the siege. Cards are played into one of three rows, each associated with one of the Hospitaller fortresses on Malta: Birgu, Senglea, and St Elmo. Initially players will be trying to resolve objectives in their separate objective decks. These represent key events that occurred during the build up to the siege. Once both players have completed their objective decks the siege begins in earnest. Only at this point do players begin comparing the combat stats in each row. Each unit has two combat stats: Might and Zeal. The player with the higher Might value adds the difference in damage markers to the location in that row, while the player with more Zeal adds just one damage marker. Each of the three fortresses in the middle has a health value and the first player to reach that number wins the location. First player to win two locations wins the game. Players can also win by killing the other player’s leader or if their opponent’s deck runs out. For what it’s worth, while I’ve seen some leaders take significant damage, I’ve never seen much more than half the deck be used over the course of the game. Winning two of the three locations was by far the most consistent victory condition.

I got an early opportunity to kill Francisco Balbi di Correggio and I took it, because without his one Resource the Christians won’t be able to do very much for the first few turns.

The core gameplay is pretty straightforward if you’ve played card games before. Cards have a cost you must pay to play them. You can generate resources to purchase cards by discarding cards from your hand at a one-to-one exchange. Some cards when in play can also be used to generate resources at the cost of not making any other contribution that round. The gameplay of discarding most of your hand to take just a few actions is a great decision space. I liked it back when I played Race for the Galaxy in college, and I like it now. It’s even more intense in St Elmo’s Pay because you won’t ever shuffle your discard into your deck, so any card you use for resources won’t be coming back later. Some cards come in multiple copies, so discarding a card you want won’t necessarily mean that option is gone forever but it’s possible you’ll never see the other copy of that card in your game.

St Elmo’s Pay also comes with a very good solitaire mode. The rules for solitaire play are easy to interpret and play very smoothly – which is not often the case in my experience. A dial is used to track the AI bot’s resources. The slow ticking up of enemy resources gives the game an increasing intensity as the solitaire bot plays better and better cards as the game progresses. Unlike a normal opponent the AI cycles its deck regularly looking for cards to play with its available resources. It makes the game feel a bit more like a race than carefully planned duel of two equal powers, but it’s still a fun experience and plays relatively quickly. I rarely found myself having to check the rulebook for what decision the AI would make, which is always good to see in a solitaire system.

Siege preparations are now very much underway, we’re clearing objectives and filling out our respective forces.

But how does St Elmo’s Pay do at replicating the siege? St Elmo’s Pay takes a very different approach to 1565 Siege of Malta, which I covered last week (link: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/1565-siege-of-malta-by-maurice-suckling). Instead of a zoomed out strategic view of the siege, St Elmo’s Pay is focused on the characters of the siege and makes it more of a clash of personalities than a game of grand strategy. This has benefits and drawbacks in terms of depicting an event like the Siege of Malta.

St Elmo’s Pay does manage to evoke one strategic element well: the emphasis initially on the taking of St Elmo. St Elmo is by far the weakest of the frontiers in the game, and since all frontiers are equal when it comes to victory it naturally encourages players to prioritise it. Do you try and grab St Elmo quickly to get a leg up on overall victory, or do you sacrifice it to try and win the other two even if they’re more challenging overall? It manages to capture some of the strategic push and pull with very little rules overhead. That said, it is far from perfect. There is no representation of Mdina in the game, so the game has no capacity to portray the alternative Ottoman strategy of taking Mdina first before focusing on the Grand Harbour.

The Ottoman’s reach the Great Siege objective which allows me to start engaging in Zeal combat and slowly chipping away at the locations for a turn or two before battle begins in earnest. Might combat only begins when both sides reach the Siege objective. This is interesting in terms of gameplay, but doesn’t feel like it makes much sense as an abstraction of the siege..

What St Elmo’s Pay does well is capture the characters of the siege. The Great Siege of Malta was brimming with larger-than-life individuals and in St Elmo’s Pay they are evocatively portrayed in portraits on their respective cards. Valette and Mustapha face off the entire game, while a rotating cast of characters comes in to support them. Cards can also eliminate characters almost as quickly as they are brought to the fight, which normally I find frustrating but here it captures the extreme violence and luck of the siege. After all, the historic Turgut was killed by the random misfortune of a misfiring gun, so why not capture some of that chaos? It also makes more room for new cards to come into play. I do kind of wish there wasn’t an automatic victory for killing the enemy leader, though. That feels more fitting to a clash of potential monarchs like Hastings than to the Siege of Malta. If either Mustapha or Valette had died their side still would have fought on, it just would have done so without an essential leadership figure to manage them. I think loss of the leader should be a significant disadvantage but not necessarily an instant loss. It also fails to capture the divided command of the Ottoman side - Mustapha is clearly the important leader and it’s very possible that Piali and Turgut will never appear in your game.

The siege begins in earnest! I’m badly losing in Senglea, but the other two are going much better (I foolishly stacked the tokens at St Elmo so it’s hard to see how many there are). The Christian arquebuses are hurting me in Birgu, though, which may limit my ability to hold out there. The choice of red and green for the damage tokens isn’t very color blind friendly.

I like how St Elmo’s Pay captures the build up to the siege. The opening rounds are carefully planning your strategy before the lines clash, and the objectives are snapshots of what happened between the fall of Rhodes and the siege. The one critique I would have is that this feels like it takes up too large a proportion of the game – once the siege itself begins things can move very quickly and the game can be over in a matter of turns. This feels more appropriate to a game about a battle like Hastings, where months of campaign preparation can be decided in a matter of hours. For an event like the Siege of Malta it feels like the siege part should take longer. It also means the temporal stress of the siege, where the Ottomans were worried about running out of time and the Christians just had to hold out until reinforcements came, is completely absent from the game which is a pity because it is such an important part of the story of the Siege of Malta.

I won in St Elmo but lost at Senglea (I should have tracked that with tokens, I should also have done something about that sun glare on the lower right). Some lucky card draws let me relocate Mustapha to the front by swapping him for some already damaged artillery. Can he help me get it over the line?

The story of the siege as shown in St Elmo’s Pay is very abstracted. There are no chronological or plausibility restrictions on when and where cards can be played. As the Hospitallers you could play a unit from the Spanish Relief Force on the first turn, no matter how absurd that is from a historical perspective. The individual spaces are also conceptually confusing. The Ottomans can play ships into the Frontiers, but what exactly does that represent, and more importantly what does it mean if my cavalry are behind my ships and why would that give them a bonus? When playing the game this doesn’t exactly bother me as long as I’m engaged in my individual decisions, but if I zoom out and try to reconstruct the story I’m telling it’s very odd. Similarly, while the event cards reference specific moments in the story of the siege they don’t do very much to conjure the extreme drama or excitement of some of the siege’s turning points. They can go off just about whenever as long as you have enough resources regardless of plausibility.

The game is chronologically and narratively kind of a mess, which makes sense given how the decks are shuffled and randomised every game. The game’s mechanics can create an interesting narrative as each player builds their forces, suffers losses, and clash for control of the central frontiers, but this feels abstracted from the historical narrative the game is about. The cards you play are an essential part of this narrative, but the characters portrayed on those cards don’t line up with their historic roles well at all. This has the effect of making the character and event cards feel more like cameos – a fun historic easter egg to recognise if you already know the history – rather than a means of conveying the greater history of the siege.

A last Ottoman push lets me just barely squeeze out a victory at Birgu thanks to my greater Zeal. My initial impression is that the Ottoman’s might be slightly easier to win with, but even at Normal difficultly my solitaire games have all been pretty close.

I don’t want to sound too negative. St. Elmo’s Pay does a lot with being a card game that is played in 30-40 minutes. It’s not a detailed simulation and it doesn’t attempt to be and there are certainly mechanics in the game that evoke some of the siege’s dynamics. The asymmetry in how the two factions play is also really interesting and provides a lot of potential strategic depth to be explored through multiple plays. On the whole I’m reasonably fond of St. Elmo’s Pay. It does a good job scratching the card gamer itch I’ve been trying to ignore since I stopped playing Magic the Gathering as a teenager. It’s not my favourite game, and I don’t know if it will stay in my collection for years to come (especially given the size of its box), but I’ve had fun playing it and it’s definitely a game I can see myself periodically coaxing a friend into playing with me.

August 4, 2022

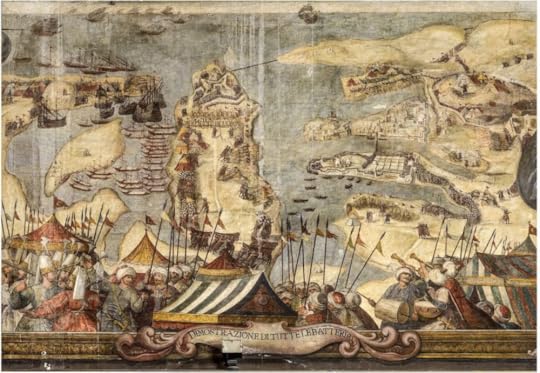

[Malta Month] The Great Siege of Malta by Bruce Ware Allen

I am enthralled by the Great Siege of Malta. It is one of the most engaging historical narratives I’ve ever come across, the kind of story that feels too exciting to be even remotely true. Too long to really work as a movie, it feels perfectly suited to a high drama HBO series – except probably lacking in sufficient opportunities for gratuitous female nudity. It is a story full of sudden dramatic changes in fortune, deaths, betrayals, desperation, and dramatic last stands against all odds. An underdog story of resistance against an unstoppable foe that somehow also manages to show how much that massive foe is struggling against their own difficulties. It is easy to see why it captured imaginations at the time and within months of its conclusion some commentators described it as the greatest siege that ever was.

It is perhaps a little surprising, then, that there aren’t very many books on the siege. For a long time Ernle Bradford’s history, first published in 1961, has been the definitive history. I was therefore pleased to find that Bruce Ware Allen’s The Great Siege of Malta provides a much-needed update to Bradford’s foundational work. While the overall narrative of the siege in Ware Allen’s account doesn’t differ greatly from Bradford’s, the inclusion of a wider range of sources, particularly more Turkish evidence, gives Ware Allen’s version a more well-rounded perspective than was present in Bradford. This is an excellent history of The Great Siege and if you have any interest in the subject, or just enjoy an engaging and exciting historical narrative, this is the first thing you should read!

As is fairly standard with accounts of the Great Siege, Ware Allen begins with Suleiman the Magnificent’s rise to the Ottoman throne and his plan to drive the Knights Hospitaller from their fortress in Rhodes. This successful siege sets the stage for the great conflict many decades later, near the end of the Sultan’s life. Ware Allen also does a good job of bridging the years in between, providing a detailed history of the Knights’ search for a new home, their eventual settlement in Malta, and the struggles they faced in their new home. He also charts the careers of the Barbary pirates, particularly the Barbarossa Brothers, whose disciples would play a key role in the siege and broader Ottoman conflict and diplomacy with major European powers.

This is a traditional narrative history. It is well sourced and very readable, and with the Great Siege there is a ton of narrative to cover so it works well. That said, I’ve now read multiple narrative accounts of the Siege and while I’m engaged every time, I now yearn for some more thematic histories. I want to know how the Siege and its failure fits into broader Ottoman politics, what it tells us about Christian alliances at the time, and the role that groups like the Hospitallers played in the Catholic Church during the Reformation that was raging around these events. Sometimes these ideas manage to peak into Ware Allen’s account, but they are always peripheral to the core story.

This is not a critique of this book, but more a comment of what I hope to see going forward. I think this account of the Siege provides a great narrative basis and could remain the core narrative/political history of the subject for many years to come. I sincerely hope it encourages scholars to start tackling other aspects of The Great Siege in more detail. An event of this magnitude has the potential to teach us about so many aspects of sixteenth-century society.

I also really appreciate how Ware Allen is able to highlight the individuals involved in the siege. While it can at times be a little overwhelming to track all these characters, the writing is good at reminding you of where an individual appeared before and doesn’t just assume that you remember every single name. I also really liked how it highlighted the multi-cultural nature of both forces. It can be too easy to fall into a clash of cultures style account, placing Hospitallers against Turks which misses that the Hospitallers were supported by a multi-national array of mercenaries and Maltese natives while the Ottoman empire was multi-ethnic with many key figures originally of European origin. Ware Allen does a good job of highlighting the various origins of the narrative’s key players which captures some of the messy allegiances present in these conflicts. Great stuff.

The only substantial critique I would offer of Ware Allen’s book is that sometimes when it journeys further afield from the sixteenth century it can make some assertions that I wouldn’t particularly agree with. There is one comment that attempts to draw a parallel between the tactics of the Knights and the Ottomans and those of the ancient Greeks and Persians which feels particularly strained. There are only a handful of cases where this happens and I suspect most people won’t even notice them, so I’m largely nit picking here.

Overall, I really enjoyed Bruce Ware Allen’s The Great Siege of Malta. The Great Siege is a fascinating historic story whose narrative excitement probably overstates its actual impact, but what a great story it is.

August 1, 2022

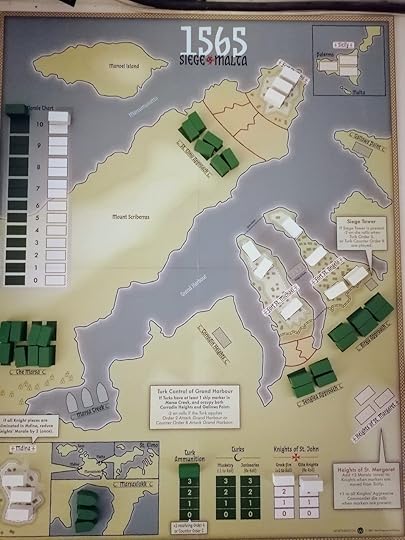

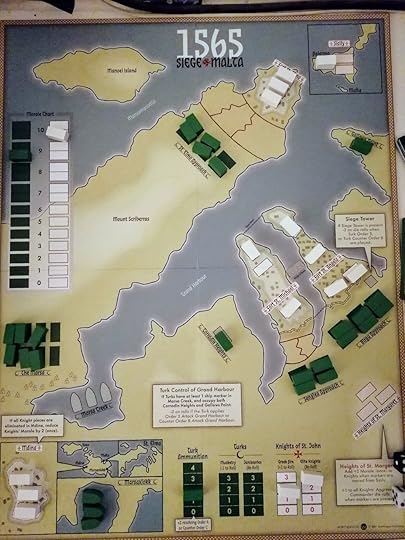

[Malta Month] 1565 Siege of Malta by Maurice Suckling

Making a game about a siege is challenging. Sieges are often by their very nature filled with long stretches of time where one side has little to do but endure. A siege like the Great Siege of Malta, which lasted most of a year, can be a long, slow, tortuous, and brutal event that doesn’t lend itself immediately to being turned into a game. Capturing the scale of a siege while also giving players plenty of choices and things to do to keep them engaged is a challenge. Even when you do find an element to gamify, if the game is multiplayer, you will need something for both sides to do. It’s not very exciting if one player is taking lots of actions and the other player just has to wait until something happens. You can design the best system ever for the attacker to try and topple his opponent’s walls, but if the defender has nothing to do you haven’t made much of a game. This may be why many wargames about sieges seem to be solitaire games. When you only have to create a game for one side and can entirely abstract the other it simplifies the challenge of making a game from the history.

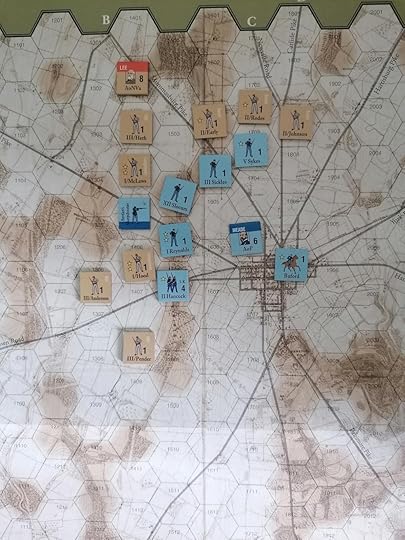

Opening set up for the Hospitaller player - I did forget to put the bridge between Senglea and Birgu because I’m an idiot. In my defense, it didn’t really come up in my game.