Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 2

July 6, 2025

Hunt for Blackbeard by Volko Ruhnke

At time of writing my Volko Ruhnke’s Hunt for Blackbeard is on track to become my most played game since records began (c.2019, when I installed the BG Stats app on my phone). For all that, I’m not sure it is an all time favorite game for me. It’s just so…more-ish. This is enabled in part by the excellent implementation on Rally the Troops, which is also how I’m reviewing a game which has yet to receive it’s physical release. This means there won’t be any section on the physical production, how it feels to play, or what the blocks taste like. Sorry! In its digital form at least, this cat-and-mouse pirate hunting game flies by in a mere moment but has you wondering what if you did it differently next time. It is by far the shortest and simplest game from designer Volko Ruhnke (known for COIN, Levy and Campaign, and big boy CDGs), but it is not without many of his signature elements as a designer. I’m largely ambivalent about hidden movement games, but I’m logging game after game here, so there must be something noteworthy about this one, right?

Hunt for Blackbeard is a two-player asymmetric hidden movement game. One player is the Hunters, whose job it is to either locate and arrest/kill Blackbeard or, at a minimum, to disrupt his ability to do piracy. Blackbeard, meanwhile, is either trying to do piracy or to invest his ill-gotten gains into a legitimate retirement before he can be tracked down and arrested/killed for getting those gains in the first place. Blackberad must complete an ever growing selection of objectives from one of two tracks (piracy vs. pirate’s life), usually by assigning action pawns to them and ending the turn in a specified location (either a specific place or a type of place, i.e. in Bath Town or in any Town space). Some of these objectives will reveal Blackbeard’s current location, likely putting him in harms way and escalating the game’s tension if he can’t lose his pursuers. Some will also give him loot which he can spend on his retirement or, more likely, on weapons to fight the Hunters should they find him.

Your sideboard as Blackbeard, you will become intimately acquainted with it. The top two rows track your two possible life paths, the middle shows your available resources, and weaponry goes at the bottom.

Blackbeard receives a new pair of objectives each turn, which makes it a challenge for the player to plan ahead. This is clearly by design, though, and really helps to deliver a sense of tension in the game. You don’t have enough time or action pawns to wait and see what comes out of the objective deck. As Blackbeard you have to be completing objectives pretty much every turn, and if you fall behind the pressure can become incredibly intense. At some point you may be wondering if your best option is to try and get caught and risk it all in a big fight at sea, assuming the Hunters oblige you and don’t just hang out and capitalize on your failed attempt to secure your future.

The Hunters, meanwhile, can interview informants to examine spaces where Blackbeard may be or have recently been, and even place revealed locations under surveillance which will tell them if Blackbeard passes that way again. They can also scout locations near either of their two ships or their constable making his way overland and should they find somewhere Blackbeard was they can potentially daisy-chain a series of cost free searches to find out where he’s ended up (assuming they don’t pick the wrong path).

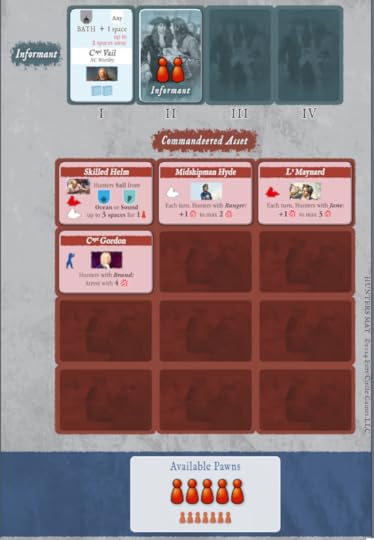

The Hunter’s sideboard. You can only commandeer equipment at your starting location, so you best pick what you’ll need for the whole game. You have more pawns than Blackbeard, but you have Informants to spend them on and three pieces to move so the costs quickly mount if you try and do everything.

Hunt for Blackbeard doesn’t drip feed information like some hidden movement games, allowing the Hunters to slowly deduce where their piratical prey is likely to be lurking. Instead, the game is played over just four turns, which could take as little as fifteen minutes with Rally the Troops doing all the heavy lifting. Blackbeard must complete half of his objectives on one of his possible life paths (pirate or retiree) in that time while the Hunters must either find him or disrupt him sufficiently that he can’t finish his objectives. As each side has a limited number of action pawns per turn, this gives you a very tight budget for your action economy in the game. You will only be able to do so much, and as Blackbeard you need to spend those actions wisely without exposing yourself while the Hunters feel each wasted search right in their pawn filled pocketbook.

Blackbeard has a bad habit of sometimes just getting caught without really making any mistake. In my first two games I was the Hunters and I happened to wander to where Blackbeard was on my first turn without having conducted any searches. This is, obviously, incredibly anticlimactic. Similarly, catching Blackbeard is largely decided by dice (unless you manage to try and arrest him with no path to escape should he elude you), and if things go very badly for the Hunters Blackbeard can capture their ships instead, winning the game for himself.

I was Blackbeard and I felt so clever that I left the Ocracoke Inlet and my opponent failed to find me. Then they arrested me on the next turn. Woops!

While both can potentially be frustrating, neither undermines my enjoyment of the game. Hunt for Blackbeard is so quick that I don’t mind just starting it again if a game ends prematurely. I’ve found that while no individual game is guaranteed to be great, the disappointments are brief and the good games have come to significantly outnumber the bad. I also happen to quite like dramatic dice-offs at the ends of games, like in Fort Circle’s first game, Shores of Tripoli, which is often decided (in my experience) by a desperate assault on Tripoli. It adds some excitement to the game’s final moments, and who really cares who wins anyway?

Should players fear that Hunt for Blackbeard is too simple or too random, there are numerous options for mixing up how you play the game. I have not tried the option where largest dice pool wins contests rather than rolls, because I didn’t get into tabletop games to not roll dice, but I have played several games using the Advanced Game rules. These are less a new set of rules and more a number of new equipment cards that both sides can recruit. The Blackbeard player can recruit Israel Hands who will go to a location on the map and potentially fulfill an objective there. They can also even separate Blackbeard from his ship and put him in town, potentially completing an objective in one place while the Adventure distracts the hunters. There are some other options as well, but these two are the most interesting I think.

The Advanced Game adds more options for you to explore as a player, which I think is a large part of the appeal of Hunt for Blackbeard, but neither felt completely game changing and honestly I will probably only use them some of the time. I do also have a minor gripe, in that the icons representing Israel Hands and Blackbeard Alone on the objective cards are too similar and I have confused them on a couple of occasions, which is just mildly irritating.

If we’re discussing minor gripes, I also find the tasks for Blackbeard that impose penalties until they are completed to be a bit of an irritant. They have great narrative potential but they can be quite frustrating if you draw too many of them in a single game. More so than that, though, is that I think they can often restrict your possible path to victory. If you draw several negative events that happen to be on the Pirate’s Life track, that kind of locks you into pursuing that path for victory this game. Given how so much of the joy in Hunt for Blackbeard is in picking a path and trying to make it work, I don’t love it when the game basically picks for me. The game is short and it’s easy to just set up and play again, so this is more of a nit pick than a grievance, but I did feel the need to hoist my flag and complain a little about it.

Hunt for Blackbeard is, of course, a historical game with at least one foot firmly planted in the wargame side of the tabletop hobby (no surprise there given its designer). While it borrows mechanics from far outside the traditional wargame space, I can see its lineage in the desire to tell an interesting story and make you feel like pirates or pirate hunters rather than in boring and mundane stuff like competitiveness and balance. Not to say that it is unbalanced, or that you can’t play it competitively, but just that it is more interested in telling you about Blackbeard’s final moments than it is in whether the “better player” always wins a given game. The better player will generally win in the aggregate, but each game has the potential to swing wildly against one side or the other.

This is perhaps its greatest strength, though. It is deeply historical. As Blackbeard you feel like a pirate trying to secure his legacy in what could be his final days. Death looms overhead as you desperately try and secure what you need without being spotted. As the Hunters you can afford to be a little more patient, after all you only really need to get lucky once, but as the game progresses that pressure will mount. You can feel the governor back at his desk waiting for your report, and he will not be happy should you fail. It doesn’t feel like A Pirate Game, in the general sense, it feels like the Final Days of Blackbeard, in the specific, and I think it’s better for it. There aren’t a lot of historical games like this, both mechanically and in terms of playtime, and as someone who loves first and foremost to feel the history in the game I’m playing this really hits a spot that had previously maybe been unfulfilled.

It also possesses several other, let’s call them Volko-quirks (Volquirks? Is that anything). First, the rulebook is…okay. I have historically noted that Volko’s rulebooks work great as references, legal-ish documents of how the game systems works, but are generally very bad at explaining to you what the game actually is. You finish them knowing how all the systems work, but not how that fits together into a game. Hunt for Blackbeard is clearly an attempt to change this, but with mixed success. It is much easier to understand what the game is from the rules, but it loses some of that Law of the Game quality which left me a little confused about how certain things work. I think the interspersing of game variant options next to the relevant rules was more confusing than helpful - I might have preferred them all be in an Optional Rules section at the end of the rulebook. Thankfully Rally the Troops was there to make sure I didn’t make a wrong turn anywhere, but without those guardrails I’m not sure I would have fully understood it from the rulebook. The core is simple and relatively easy to parse, it’s just little aspects of the system that I didn’t understand, in part because I haven’t played anything like this so I didn’t have a firm reference for what to expect. It’s far from the worst rulebook I’ve ever read, but I’d also say it’s no Votes for Women in terms of clarity of the rules.

The second Volko-quirk is that this is a game that I feel like I only really began to understand what I was doing after nearly ten plays. This was most prevalent in his previous Levy and Campaign games, where for the first half a dozen games you’re doing well if you manage to avoid starving your own soldiers. In Hunt for Blackbeard I felt like I was stumbling blind and hoping to walk into the pirate as the hunters or like I was stealing cookies and hoping nobody in the house was awake to see me as the titular pirate. Strategy wasn’t exactly top of my mind, I was just trying stuff and crossing my fingers. Now that I’ve logged a fair few plays as both sides I’m beginning to understand how to think in the big picture. I know the available objective/informant cards better, I can see the bottlenecks on the map, and I understand the underlying probabilities around arrest/escape/boarding attempts a bit better.

This is something I actually quite like about Volko’s designs - sure it takes a while to become proficient but that feeling of developing proficiency is so very satisfying. Being able to play these games on Rally the Troops is a huge help towards achieving that, although more so in the case of a long and complex game like Nevsky than in something light and fast like Hunt for Blackbeard. You could sit down with a friend and develop your own little meta in Blackbeard over the course of an afternoon. It offers so many different options and strategies for you to explore, so each game can be something significantly different but also so tight and fast that you can quickly finish it and build on top of it with another game. Two players could quickly develop strategies, counters, and new strategies in only a few hours. I’m sure a dedicated player could work out a handful of optimal opening plays, but to me the joy comes in the exploration and Blackbeard offers so much exploration for such a small game. When the physical game is available I hope I can find someone to spend a day exploring it again with me.

Hunt for Blackbeard is not my favorite game. It’s probably not even my favorite game I’ve played this month. It is, however, my most played game of at least the last two years. I could sit down and enumerate minor criticisms of it - how sometimes the strategy doesn’t feel that deep and early bad luck can stagger Blackbeard before he ever gets started - but I’m not sure those really matter. I say this with love and praise: Hunt for Blackbeard is like really good snack food. It’s not going to fill you like a gourmet meal, but after each bite you think “yeah, you know what, I’d have a little more of that” and before you know it you’re a dozen games deep and you see the North Carolina coast when you close your eyes. Sure you could just pick one strategy and play it every game, but that’s boring. Hunt for Blackbeard has given you a canvas (a small one, but a canvas nonetheless) and you should experience the joy of painting it with something new each time. After all, who cares who wins if the story is good?

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

June 29, 2025

What’s in a Name – Defining the Hundred Years War

Nobody caught up in the chaos and bloodshed in France between the years 1337 and 1453 ever referred to what was happening around them as The Hundred Years War. Neither did future generations, until the early nineteenth century, when the name was coined by French historians (technically as La guerre de Cent Ans), from where it spread across Europe and the world. Since the concept of The Hundred Years War is entirely a historiographical construct, it was only a matter of time before people began to question whether it made sense. After all, the kings of England and France had fought numerous wars before the Hundred Years War and would continue to do so after, so what made the Hundred Years War a coherent conflict? Buckle up kids, because this might take a while.

Defining the Hundred Years WarBefore we get into the historiographical weeds, it would be worthwhile to lay some groundwork, especially if you, the reader, are not already intimately familiar with medieval European history.

The conflict we call The Hundred Years War began in 1337 when Edward III, the King of England, declared that he was the true King of France and that the then French king, Philip VI, was a usurper. Even that, though, is a bit like starting in the middle. To understand why Edward III did this requires reaching even further back into Anglo-French history. One could in theory reach back as far as 1066 (and we’ll get there) but for these purposes it is enough to go back as far as the reign of Philip IV of France, who was king from 1284 until his death in 1314.

Philip IV is a pretty wild guy, infamous for dissolving the Knight’s Templar and helping to create the Avignon Papacy, but it is his children that we are really interested in here. If we leave aside the ones who died in childhood, Philip had four children: Louis, Philip, Charles, and Isabella. Isabella married Edward II, King of England from 1314 to 1327, and will be important later, but first let’s deal with the sons.

Louis became King Louis X on the death of his father but died only two years later in 1316. He left behind a pregnant wife and a daughter, Joan, from a previous marriage. His wife gave birth to a son who was declared King Jean, but he died aged only four days. This left the inheritance in dispute, as Louis’ only other heir was his daughter. In stepped his brother, Philip, and it was agreed post-facto that no woman could inherit the throne of France, so Philip became Philip V of France. Philip’s reign proved similarly short, and he died in 1322 after only six years on the throne. He left behind only daughters, who were quickly passed over thanks to the precedent that their father had helped to establish. Charles IV stepped in to take over for his brother, but in a familiar refrain he died in 1328 after six years on the throne and, you guessed it, left behind only daughters.

Now, this left France with a bit of a quandary. All the legitimate sons of Philip IV had died, and none had left a male heir (something that had literally not happened in centuries). There was, however, still Isabella. While it had been agreed that a woman could not inherit the throne, nothing was settled on whether she could pass a claim to the throne on to her descendants, and Isabella had a son (the future Edward III of England). However, Isabella was also an adulteress who the year previously had joined with her lover to depose (and murder) her husband and put her son on the throne of England as a puppet boy-king. That, along with a general desire to not unite the thrones of England and France, pushed the nobility of France towards considering yet another redefinition of how inheritance worked for the French throne.

The nobility of France elected to move further afield in the family and, using another post-facto justification to declare that women couldn’t pass on the royal claim, picked Philip of Valois, the son of Philip IV’s younger brother and so cousin to the previous three kings of France. Philip, of course, happily took them up on their offer and was crowned Philip VI.

For the time being the matter seemed settled but in 1330 Edward III led a coup against his mother and her lover. He executed the latter and established himself as the sole ruler of England at the young age of 17. I’ll leave aside the many, often inexplicable, events of the following seven years but let’s just say that by 1337 Edward had secured his rule in England and was considering the merits of reevaluating the decision back in 1328 to pass him over for the throne of France.

So, that’s how it began. In brief, here’s how it went:

The early years were kind of a mess as Edward pursued an expensive and ineffective strategy of securing alliances with Philip’s various foreign enemies. It looked like things might end before they really got started until Edward pivoted to a strategy of aggressive (and much cheaper) raiding in France which ultimately culminated in battle at Crécy in 1346 where Edward secured a famous victory over Philip (which was also incredibly lucrative for the English). The Black Death put a halt to fighting for most of the next decade, but a subsequent victory at Poitiers in 1356 saw Edward’s son, the Black Prince (a nickname he never would have used), capture the now deceased Philip’s son, King Jean II.

A literal king’s ransom via the Treaty of Bretigny in 1360 saw Edward surrender his claim to the French throne in exchange for a massive inheritance of French lands in Aquitaine that the English kings had once ruled but lost slowly over the years. These lands were meant to be held independent of the French King, effectively removing them from France entirely. However, the treaty agreement was a bit of a mess, with the final version never quite being fully signed by both parties, which left a crack through which the next French king, Charles V, would rip it asunder.

The 1370s-1400s saw a slow decline in English power in France as Charles V and, briefly, his son Charles VI reclaimed significant French holdings from the English. England under Richard II, Edward’s grandson, experienced significant turmoil and he was eventually deposed by his cousin Henry, crowned Henry IV, in 1399. Meanwhile Charles VI developed a form of severe mental illness which plunged France into civil discord and eventually war.

It was in this climate of discord that Henry’s son, also named Henry, inserted himself. Henry V famously won victory at Agincourt in 1415, but it was his campaign of sieges from 1417-22 that won him significant lands in France. However, these campaigns also brought about his early death. In 1420 he had married Charles VI’s daughter and their son, also Henry, would inherit another strong claim to the French throne. Even after his death Henry’s brothers managed to oversee further expansion of English control in northern France, but it was a losing battle. English finances could not afford to conquer all of France, and they relied upon the ongoing civil war to bolster the borders of their newly conquered lands.

Charles VI’s son, the Dauphin Charles (the fifth of his sons to hold that title), managed to rebuild his power outside of English held lands (primarily in Bourges and Poitiers) and, to make a very long story much shorter, reconciled with his Burgundian cousins in 1435 to end the civil war, restructured the French military to be the most sophisticated in Europe in the 1440s, and drove the English king from France from 1449-53 – leaving only a small region around the city of Calais still in English hands.

So, that’s an incredibly oversimplified account of nearly two hundred years Anglo-French history. As you can imagine there are a lot of different ways this could be split up by historians.

There are, essentially, three main schools of thought in how to deal with this period of Anglo-French history. There is, of course, the label of the Hundred Years War but I think it makes the most sense to come to that one last. First let’s consider the two main alternatives, which are essentially people who think that the Hundred Years War is way too long of a period, and it should be split up, and those who think that the Hundred Years War is far too short of a period and it should be stretched out.

A hundred years? That’s way too many!One argument, which I have a lot of sympathy for, is that 116 years is an unwieldy amount of time to have to deal with. In general, histories of the war we break it up into phases, and this argument pushes forward the idea that we should go even further and split those phases into distinct topics unto themselves. This generally involves a minimum of two distinct wars, the phase under Edward III and his grandson Richard II vs the “Lancastrian phase” under the three Henries (IV-VI). However, one can get even more granular if they want! For example, one could split Edward III’s reign into multiple phases, such as the early failed alliance-based strategy, the early chevauchee era, the post-Black Death era, and finally the period of decline at the end of his life. How much you want to slice it depends a lot on the individual historian and their perspective.

Unfortunately, nobody can really agree on exactly where to break up the Hundred Years War. Even besides the many possibilities I named, all the examples I gave above are extremely Anglo-centric. If one takes the view of the French, the break points don’t align nearly so neatly with the reigns of English kings. This creates even more places where we can argue over how to split it.

No single theory of how to re-divide the Hundred Years War has fully caught on, which means that this practice is generally reserved for more focused studies on just one subject that is best examined in detail without having to deal with the wider implications of the century. While I am partial to the idea of splitting the Hundred Year War approximately down the middle, I think the deposing of Richard II in 1399 is a good break point, I’m also not sufficiently convinced that it is significantly better than the traditional definition. It’s great for detailed academic studies, but as we’ll get to later, I think the old definition’s merits have yet to be overcome.

A Hundred Years Is Actually Way Too ShortThe English and French monarchs had beef going back at least as far as when the upstart duke of Normandy decided to make himself a king in 1066, so why should we limit ourselves to just this century? While few historians would push for the Almost-Four-Hundred-Years War as an alternative, many have argued that we should expand our scope to include a much wider period. Michael Livingston, no stranger to challenging the status quo, has a new book coming out arguing for a two-hundred-year war covering 1292-1492, which shows that this strain of argument remains alive and well.

A more common extension is to push its start earlier, to around the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II in the twelfth century and the creation of the so-called Angevin Empire (another historiographical construct) as the turning point. Philip II’s wars to reclaim French lands from the English monarch c.1200 certainly resemble the kind of inter-royal conflict that we see in the Hundred Years War. Others might only go back as far as Edward I’s conflict with Philip IV in the thirteenth century, since the peace that involved the marriage of their two children helped to create the problems that would generate the Hundred Years War.

The problem, as I see it, with this approach is that it risks diluting its subject matter and removing the elements that make the period of 1337-1453 stand out as a distinct section of Anglo-French conflict.

Partly, this is just practical. It’s already a challenge to fit 116 years of complex history into a single book. The wider a historian’s scope the harder it is going to be to cover that subject in detail. One could tackle this with a huge a multi-volume history, but that by its nature must carve the topic up (usually with each book needing to stand at least partially on its own, for commercial reasons if no other), and then it looks more like the subdivided approach above. While arguably not a great excuse for a scholarly framework, we can’t fully avoid the practical concerns if we want our history to be read and engaged with by others.

Beyond that, though, you quickly run the risk of oversimplifying because in linking together multiple centuries of history you are naturally going to highlight the continuity, the shared elements between periods, and you will lose the differences because there isn’t space for them. The 1200s were a very different century to the 1400s! You would naturally be quite skeptical if someone told you that The Seven Years War (1756-63) and World War II (1939-45) were part of the same conflict, but they’re less than 200 years apart, fewer years than Bouvines (1214) and Agincourt (1415). I think the Hundred Years War as a topic is already so long that it causes compression in our understanding of the times involved (histories often jump from Crecy to Poitiers despite there being a decade in between), and a wider view simply doubles down on this problem.

It's still standard for a history of the Hundred Years War to include some information about events before and after the war (mine certainly does, and it’s just a history of one battle), which on some level admits that we must view the conflict within a wider context. But then, this is standard in history: context is king and there is no part of history that can be written about with no context at all. What makes this approach different from just a standard history is in the emphasis it places on continuity between earlier or later periods and the time we call the Hundred Years War. It’s more than just adding context, it’s redrawing the borders.

As is maybe clear, I’m not exactly a fan of this approach, but I actually think the strongest argument against it is the argument for the traditional view.

Why the Hundred Years War?Let’s get the weaker argument out of the way first: the Hundred Years War has brand recognition. It might seem trivial, but I think it matters. There are real benefits to the fact that when I say “the Hundred Years War” to someone, they have a general idea what I mean. A similar logic is why I still used the term “longbow” in my work even if I think it’s not the most accurate way to describe that weapon (we should call it a yew self bow). It is easy to parody academics by pointing out their love of arguing over what words mean and boring definitions (which, for the record, I do enjoy),but we still need some general agreed frameworks to use if we’re going to be able to talk to each other.

Since it’s such a recognisable name, the barrier to reject it is much higher. In changing it you are introducing needless complexity, so you should prove that the existing framework is actually making historical analysis or understanding worse, it can’t just be neutral it must actively be bad.

That’s just the practical side of things. In reality, I think the argument for the Hundred Years War as a single conflict remains incredibly compelling. In this period, we can see a significant transformation in the shape of Anglo-French conflict. While these two monarchs fought before and after this period, the nature of those fights were fundamentally different from each other because of what happened in this century (plus or minus sixteen years).

When William the Conqueror became King of England, and more importantly when his heirs recombined the titles of Normandy and England, he created a natural conflict. Kings don’t like being vassals as well as kings, and as Duke of Normandy the Kings of England were vassals of the French king. As the English kings expanded their holdings in France to include Anjou and Aquitaine, among others, that just created even more potential friction points. This relationship naturally raised questions about the extent and limits of vassal relationships, especially when that vassal potentially holds more land and wealth than his overlord. You can see similar problems between the kings of England and Scotland, where the Scottish kings often owned lands in England and were thus English vassals as well as kings – something that would ultimately cause a century-plus long series of Anglo-Scottish wars (coincidence?).

Throughout this period, though, the English king acted in France as one of the senior princes of the kingdom. Edward III being excluded from consideration for the French throne was one thing, but they also largely ignored his potential contribution as Duke of Aquitaine. He was one of the chief princes of France, he should have had a say in the next king. While there are arguably good reasons to have excluded him giving what was happening in England, he arguably also had a legitimate greivance as well.

This changed when Edward declared himself the true king of France. Sure, he was still a senior prince of France throughout this period, but he was not just a prince in open rebellion with an established path to reconciliation (princes were always rebelling), he was saying that the sitting king had no right to be his overlord. Matters were made even worse (I would argue) with the coronation of Henry VI. Edward III was able to give up his claim in 1360 because it had largely been a political position, but when Henry VI was actually crowned king, that was a harder thing to go back on. English negotiators trying to find a peaceful solution could never agree that their monarch wasn’t the true King of France, but those representing Charles VII required that as a baseline, which made any peaceful settlement basically impossible.

This set the two monarchs on a crash course. While the Anglo-Scottish conflict was eventually (mostly) resolved by the combination of the two thrones (leaving aside things like the Jacobite rebellions), in France the opposite solution was employed: the two were ripped asunder forever. The English kings had previously managed to reclaim some of the lands that the French monarchs had seized from them, but that would no longer be the case after 1453. That’s because previously the English king had at least some claim to the titles, and the dispute was really over what its borders would look like (to somewhat oversimplify the matter). However, after 1453 the English king was no longer a prince of France – all of his titles were gone and his one remaining landholding, around Calais, was a foreign city largely populated by English immigrants (the native French population having long since been expelled). It was a colonial bastion in foreign lands.

So, while the English and French would continue to fight wars and the English monarch would only give up the claim to be the true ruler of France some years after Louis XVI lost his head, the loss of that princely status had changed the nature of those conflicts. The Hundred Years War is a period of change, a transformation in the relationship of these two powers that took over a century to complete. That, to me, is why it still makes the most sense to view the Hundred Years War as a singular event even if it also remains practically useful to split it into sections for analysis and to consider the wider context beyond its nominal beginning and end.

If you made it all the way to the end, thanks for reading! If you found this interesting, I would point you to my latest book on the Battle of Castillon. Castillon was the final battle of the Hundred Years War and often seen as marking the end of the war. In my book I, of course, discuss the specifics of the battle but I also reach beyond that to discuss the war’s origins and what it means for a historiographical concept to have an ending (kind of like what I wrote about here). Please do check it out!

Castillon: The Last Battle of the Hundred Years War covers the origins of the Hundred Years War, the Edwardian and Lancastrian phases of the war, the Military Revolution of the fourteenth century and Charles VII’s radical restructuring of the French military in the fifteenth century, as well as a detailed study of the battle and how we can know what happened on that day in Gascony. It is far reaching and comprehensive in how it analyses this key battle and will give readers a substantial understanding in not just Castillon but in late medieval Anglo-French warfare in general.

Order Now!I also highly recommend the following books on this and related topics:

Curry, Anne, The Hundred Years War, 2nd edition (London, 2003)

Green, David, The Hundred Years War: A People's History, (Padstow, 2014).

Grummitt, David, Henry VI, (New York City, 2015).

LaBarge, Margaret Wade, Gascony: England’s First Colony 1204-1453, (London, 1980).

Prestwich, Michael The Three Edwards: War and State in England 1272-1377, 2nd ed. (1980, New York, 2003).

Prestwich, Michael, A Short History of The Hundred Years War, (London, 2018).

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

June 21, 2025

How to Pick a Good History Book

One of the more niche skills I, and many others, have acquired in studying for a PhD in history is the ability to identify whether a history book is likely to be good or not. This is also something of a curse, since whenever some non-historian friend shows me a new book they’ve bought or are excited to read, I must suppress (something I don’t always succeed at) the urge to pontificate on the merits of such a book. To do so is, more often than not, to take on the role of a vibe killer by pointing out why X popular history book is fundamentally flawed (looking at you Guns, Germs, and Steel, you know what you did). This leads to a natural follow up, though, of how could I help someone find better history books – how can I share this skill of identifying whether a book is likely to be good or not with others who are interested in reading good history books but didn’t spend years of their life getting a fancy piece of paper to hang on their wall? It’s a rather difficult skill to articulate, but in this post, I’m going to do my best to explain my methods and to also discuss the importance of good history.

To a degree this is an impossible task, because historians never read just one book. There are very few subjects where I can point to just one book and say, “this is the one you need to read”. This is especially true of larger subjects where there are many, many books. I’ll talk about this more later, but history is a dialogue between scholars and no one person has a monopoly on it. Each book brings something different to the discussion and engaging in multiple viewpoints (within the scope of real history, conspiracy theorists not invited) is essential to a good understanding of a topic. This is why even after I’ve read a dozen or more books on a topic like the American Civil War, I can still feel like I am a relative novice on that subject.

However, I fully acknowledge that your average person on the street does not want me to recommend six to eight books to them. They have their lives to live, and they want one, maybe two if I can really sell it to them, books on a subject to read before bed. That is partly why in this post I’m hoping to empower individuals to find their own books without having to engage in the eternal struggle of having your historian friend try and distil a field down to one book. You don’t need to pick out the book on a topic, because no such book exists. Instead, I want to help you find a good book, which can maybe be the first step towards that obsessive reading that drives so many historians.

I want to acknowledge the subjective nature of what I’m doing here. In my definition a good book is one that will teach the reader something about history that is largely, at time of reading, accepted to be true by most scholars of that subject. History is an eternal debate whose relationship to “truth” is ever fluctuating (more on that later), so I don’t want the notion of a good book to be taken in an absolute, objective sense. Similarly, readers can learn a lot from a book I would classify as bad, i.e. one that lacks scholarly rigor or contains significant numbers of falsehoods, but I would in general steer beginner readers away from the more troublesome books on a topic. For the purposes of this article a good book should also be able to largely stand on its own and not require an onerous amount of prior knowledge of the subject (a tall order, I know).

I’m going to outline my general approach to selecting a book on a subject that is new to me which usually helps to secure a book of good quality. I will note now that it is not a guaranteed success – several terrible books have successfully met these criteria, and some stellar history has failed to. Instead think of it as playing the odds, with these criteria I find my chances are at their best when going into a new field with no prior experience.

In summary, to be expanded upon afterwards, here is how I judge books:

Was this book, or a similar book by the same author, recommended to me by someone whose knowledge on this topic I respect?

Was the book published in the last thirty years?

Is it from a respectable publisher (usually academic, but not always)?

Does the author hold a higher degree in history and/or are they an academic at a respectable institution?

Has the author written other books on this topic? Is this a deviation from their normal work?

How long is the book? How expensive? Is it in my local library?

Was this book, or another similar book, recommended to me?This is the best and most consistent way to get a good book: be recommended it by someone who knows what they’re talking about. Sadly, this is also one of the hardest to achieve, because unless you know someone who happens to specialise in your new area of interest you’re going to have to track an expert down. If you do happen to know a specialist, please, please ask them about the subject. I guarantee you they are begging for people to listen to them recommend books and talk about it – everyone in their immediate life is probably sick of hearing about it! If you don’t happen to have an expert in your wider social circle, I recommend borrowing one from someone else’s. I usually steal mine from r/askhistorians.

The booklist on r/askhistorians is a treasure trove of books you haven’t heard of but should probably read. While somewhat irregularly updated, most of its sections contain a plethora of works that have been reviewed and discussed by people who know what they’re talking about, and they even include little blurbs to tell you why the book is good. The real challenge for me is limiting myself to just one of the amazing selection of books they show me! If the booklist should fail you, you can also ask for a recommendation on the subreddit itself, although if your topic is sufficiently niche you may not receive an answer.

Now, should you be without a local expert and if your chosen topic is not well covered by the r/askhistorians community (or if you have a Reddit allergy, I can’t blame anyone for that), then we must move on to the next criteria.

Was the book published in the last thirty years?It can seem a bit snobbish or biased to exclude books of an older vintage, but it is generally the case that more recent books contain better scholarship. The explanation for this is honestly pretty straightforward: the people writing books now have more books and more research to inspire and guide their own work than those who came before them did. We have also seen a greater diversity of scholars entering academia in the past thirty or so years (before it all caught fire, but that’s a separate diatribe), which has in turn led to exciting re-examinations of things once believed to be true. More diverse voices and perspectives using existing research have built better foundations for future scholars to work from – good history begets more good history.

This is sort of what historians mean when they talk about historiography. Technically, historiography is the study of what previous historians wrote about a subject – i.e. instead of reading a historian because you want to know about the Wars of the Roses you are reading his or her work because you want to know what they thought about the Wars of the Roses, disconnected from what may or may not have happened.

Historiography is fundamental to the practice of history and is also an excellent way to show how perspectives on history have changed over the centuries. Every generation of scholarship is infused with the biases and interests of the time it was written, but it is usually only obvious what those were years later when we look back. This in turn gives us reason to reevaluate what was written before and use that information to inform future work.

I have at times seen the belief from non-historians that basically what historians do is they pull out the existing puzzle pieces of “objective facts” about a topic and then they use those pieces to arrange their own story about the past. I cannot stress how far from the truth this is. There is no supply of objective historical fact – what we “know” about the past is inherently filtered through biases before it ever reaches our eyes.

There is more available information on the past than any one person can sift through in a lifetime. Each new history not only builds upon the work that comes before but also often introduces or reevaluates existing evidence, changing our perspective significantly. The more works that have been published in a field the more information we can draw on when we discuss it (since historians must rely on each other as much as we rely on primary sources). Older histories by their vary nature were working with a more limited pool of information and context – sometimes they are still great, but they cannot magically overcome that limitation.

Now, there are many excellent older historical works that still hold up to this day – especially in more niche fields that don’t see a lot of active publication. However, in general a book published in the last twenty to thirty years has the benefit of more research and scholarship to draw on than one written forty or more years ago, in addition to the fact that in general academia has improved significantly in the quality and rigor of its work over the same time. This is even more true if you are interested in reading about a country or people that was subject to European colonialism – the works written when they were still colonies are often highly problematic.

This is, of course, not a guarantee. Some recent books are awful, or at last sub-par, which is why you should pair this consideration with my next two.

Is it from a respectable publisher?But what is a respectable publisher? In general, an academic publisher should ensure a level of rigor to the research. In the past, academic texts had a reputation for often being dry or boring to read. While books like this certainly are still published, more and more I’ve found that contemporary academics pride themselves on being able to effectively communicate their work to a wider audience. It may not be Mark Twain, but most academic books are a perfectly good read.

However, academic books can also be incredibly expensive. Some presses have made an effort to remain relatively affordable, but many increasingly target a niche market of scholars and university libraries who have book budgets they can spend on volumes that cost upwards of a hundred dollars or more. In general, unless you are a specialist yourself, I would skip these triple digit books – they are less likely to be written for a general audience and are usually not going to be worth the cost to a non-specialist.

Many academic publishers specialise in specific subjects and are worth a look if that overlaps with your interest. Boydell and Brewer have a great selection on Medieval Europe while University of North Carolina does great work on the American Civil War, for example. University of Chicago, Yale University Press, and MIT University Press have all generally impressed me with the quality of their output without necessarily charging eye-watering prices.

While certainly some good scholarship has come from self-published histories – one of my all-time favourite books, Playing at the World, was basically self-published in its first edition – in general these are few and far between. Especially now in the age of AI and easy self-publishing of eBooks I would be wary of something that hasn’t been put out by at least a mid-tier press.

Large publishers or specialist publishers, think Penguin or Random Houe for the former and Osprey or Pen and Sword for the latter, can put out good books but it depends a lot on the author. With these books you can be confident that they will be proofread, and the actual physical book should be of good quality, but if you want to be confident of the scholarship inside you should look to the next two categories.

Does the author hold a higher degree in history and/or are they an academic at a respectable institution?Many excellent historians have no formal academic training in the subject and quite a few PhD holding Doctors of History are complete cranks, but in general the process of receiving a higher degree in history (be it a masters or PhD) will give the author the research and writing skills that will help them to create good history.

While more conspiracy theorists and backwards racists than I would like are employed by major academic institutions, for the most part existing within the scholarly community imposes on historians an expectation that their work will meet a certain standard and not embarrass themself or the discipline of history. Also, those who work full time at a university have more time and funding to devote to research and writing than many outside of academia do (excluding that minority of popular authors who somehow manage to make a living writing history). No, I’m not jealous, I swear. I love paying for all my books out of my own pocket.

Outside of traditional academia, some journalists write amazing history and some write absolute trash. If the author of a book I’m interested in is a journalist one of the first things I do is flip to the back and look at the referencing. I don’t need to read it in detail, but in general of the journalist is doing the work of actual references and bibliography I place a higher level of trust in them than someone who maybe isn’t bothering. I will say that in general journalists are better writers than historians.

While no surefire guarantee, an academic background or position is usually a nudge in favour of an author, suggesting that their work will at least be pretty good.

Has the author written other books on this topic?There is a certain type of academic, or other intelligent person, who is great on one subject but doesn’t really know how to stay in their lane. This person assumes that expertise in one field gives them expertise in another when this is basically never the case. Now, many a scholar has mastered more than one field, so publishing a book in two subject areas isn’t a red flag. However, it is essential to consider how closely related those fields are and the tone of those works.

For example, a physicist publishing a history book on the development of the atomic bomb is a logical connection – expertise in physics could help them understand and explain the bomb. However, if their book claims to reveal some heretofore unknown dark secret or to completely revolutionise our understanding of mid-twentieth century history, proceed with caution. The belief that one can completely redefine someone else’s field (especially with just one book) suggests the kind of arrogance that is usually driven by ignorance.

In general, an author who has written multiple books on a subject (e.g. the Civil War or labour movements in the nineteenth century) is more likely to be a trusted source on that subject that someone who has written primarily in another, unrelated field.

It is useful to pair this with an examination of how those books were published, though, since you don’t want to confuse someone who churns out poorly written and edited slop with a scholar who has devoted years to their subject. Publishing a lot on a subject is not a guarantee of expertise.

Also, just be really careful about economists writing history. I don’t want to be engaging in stereotype too much, but a lot of them write really trash history.

How long is the book? How expensive? Is it in my local library?Okay, you’ve made it this far and you’re still not sure about whether this book is the one you want. There’s only so much prep you can do, at a certain point you just got to take a swing and see if it’s a hit. You’ve hopefully managed to nudge the odds a little in your favor with the previous criteria, so this is just some final mitigating factors.

How long is the book? I’m much more willing to take a chance on an interesting looking book that’s 200-300 pages long than I am on one that’s 800 pages. If I’m going to commit to a doorstopper, I really want it to be good. Getting 200 pages into a book and finding out it kind of sucks is no fun at all.

How much does it cost? Similar to the above, if a book is ten bucks, well maybe it’s worth a shot. If a book is fifty dollars, then it’s probably not. However, if the book can be found in my local library (or requested via inter-library loan), that’s another matter. Taking a chance on something that’s free is really no harm at all.

In ConclusionWell done for making it this far. I left off a few other possible avenues – such as digging up academic book reviews in peer reviewed journals – usually due to them being either too niche or too difficult for an ordinary person to access. Reviews are often paywalled, which is egregious if you ask me.

Hopefully, after reading this, you feel empowered to find good books and enjoy them but not overwhelmed by my abundance of wordy criteria. I want to end on the note that there is no shame in reading a bad book, we’ve all done it, but I want you to read good books and be confident that you have. Even more than that, though, I want you to read many books. No single book can give you true understanding of a subject – you must read both widely and deeply for that. It’s not for everyone, but I promise you it can be incredibly rewarding.

Finally, finally, here, in no particular order, are a few of my favourite history books. I’ve tried to pull from a range of subjects, so hopefully some will strike your fancy. I highly recommend them:

Playing at the World 2nd ed. By Jon Peterson

Searching for Black Confederates by Kevin Levin

The Korean War by Bruce Cummings

The Dull Knives of Pine Ridge by Joe Starita

Robert E. Lee and Me by Ty Seidule

The Jacquerie of 1358 by Justine Firnhaber-Baker

White Mythic Space by Stefan Aguirre Quiroga

Blood Royal by Robert Bartlett

The Evolution of Modern Fantasy by Jamie Williamson

The Battle of Crécy, 1346 by Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston

Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors by Brian Catlos

Frederick the Great: King of Prussia by Tim Blanning

The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch

Race and Reunion by David Blight

When Montezuma Met Cortés by Matthew Restall

Inventing the Renaissance by Ada Palmer

And if you’ve made it to this very end, may I recommend my own books? They meet some, but not all, of the criteria I’ve used in this article, but despite that I personally think they’re pretty good. They are:

The Medieval Crossbow: A Weapon Fit to Kill a King

Castillion: The Final Battle of the Hundred Years War

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

May 30, 2025

My First KBO Game

I didn’t really grow up with baseball, or at least watching baseball. I’m still American, so my dad taught me how to throw and how to (kind of) hit a baseball, but I never played outside of our yard, and we never watched games. I can put most of the blame for the latter on the fact that we had no team for most of my childhood – Virginia lacks any major sports teams and Washington, DC (my dad’s hometown and source of our local major sports teams) was in its 33 lacuna of no baseball until I was fifteen, by which point I was a bit too busy to become invested in another sport. I’ve had a passing interest in baseball, and I followed the Nationals 2019 triumph, but only via the newspapers. However, when we were planning our move to Korea, I had heard that attending a baseball game in Korea was a must. While we were surviving our first Korean winter (I say surviving, my partner and daughter loved the freezing cold, me not so much) I was eagerly looking forward to the start of baseball season.

Our local team, the Hanwha Eagles of Daejeon, are historically a bad team. They last won the championship in 1999 and rarely if ever make it to the post season (which requires the team be in the top half of Korea’s ten team league). I am no stranger to following terrible teams, I was raised on Washington Football after all, and the benefit of a bad team is that tickets should hopefully be easy to come by. I thought we’d have no trouble getting tickets to watch the local team lose. This proved to be an erroneous expectation.

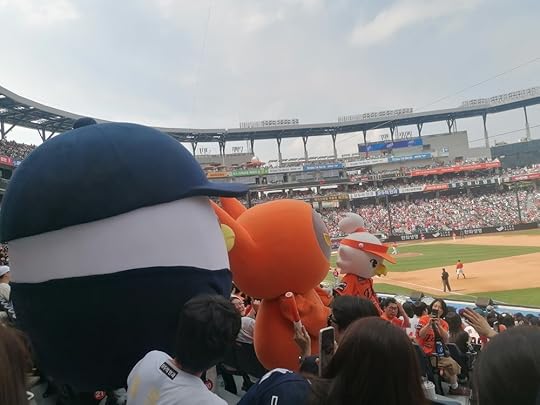

While the team may not have been good, their mascot game was and remains incredibly strong.

Initially, I did not notice the impending difficulties. While I was excited for the start of baseball, I was also starting a new job in the spring which took up much of my attention. I also wasn’t sure how best to watch baseball – we don’t have a TV in our tiny apartment and Korean streaming services have proven confusing, in no small part thanks to my inability to read hangul. At the start of May we took advantage of a long weekend courtesy of the double holiday of Buddha’s Birthday and Children’s Day (plus the not holiday but maybe it should be of my own birthday) to travel from Daejon to Gwangju, in the southwest of the peninsula. By coincidence, our local Eagles were traveling in the same direction to play Gwangju’s Kia Tigers (last year’s season champions, generally considered the best team in the league, but who are doing poorly this year). The wave of orange clad Eagles fans that accompanied us on our train journey motivated me to track down some baseball while we were relaxing in our hotel room, and slowly but surely the three of us were hooked. Initially we couldn’t find the Eagles game, so we rooted for Daegu’s Samsung Lions against the Doosan Bears from Seoul (when in doubt, root against the big city team), but on subsequent days I was able to find the Eagles. When we came home on Tuesday, I signed up for a TV streaming service for the princely sum of $3 a month so we could watch the games live.

Once we started following the Eagles more seriously, it was time to start looking for tickets to see them live. This is where things got complicated. You see, usually the Eagles are a bad team. This year, though, things are different. When we started watching them, they were on the tail end of what turned out to be an impressive 12 game win streak. They were also, for a time, top of the league and at time of writing are still solidly in the top three. Few things can get fans more excited than a historically bad team suddenly having a hot season.

This matter was compounded by the fact that Hanwha just built a brand-new state of the art stadium in Daejon, and this was its debut season. Curiosity about the new stadium’s features alone would drive more ticket sales. My expectation that we could pick up tickets to see a pretty bad baseball team whenever we wanted were dashed as tickets to Eagles games sell out in under 10 minutes. If you sign in to the ticket purchasing app at the exact time the tickets go on sale, there is no guarantee you’ll get them. It’s brutal out there.

The old stadium was the smallest in the league, this new one is one of the largest. Here it is from behind home plate (not where our seats were) and it really is very nice. There’s a picnic area out in left field and we'd love to get tickets to sit there, but getting any ticket is a challenge let alone a specific one!

If I had been on my own, my quest would likely have ended here. Thankfully, I had a secret weapon: my partner is big concert (and Kpop) fan. She saw Suga in New York and J-Hope in Seoul, in addition to several classic bands like Fleetwood Mac and U2 in Dublin. She’s good at buying tickets to events that will sell out and sell out quickly, is what I’m saying. Even still, baseball proved a challenge. Unlike most concerts nowadays, and especially the Korean concert she went to, there is very little to stop people from buying huge numbers of baseball tickets and reselling them on second-hand sites. We saw some listings where people had 40+ tickets for sale. So even if she could get within the first several thousand people in the queue to buy tickets, that was no guarantee that there would be seats left by the time it came to her. In the end it was her skills navigating the second-hand sites that got us tickets. They were more than we would have paid if we bought them direct, which is annoying, but they still were not too expensive once all things are said and done (certainly much cheaper than Major League tickets in the US). We had tickets for Hanwha Eagles vs. SSG Landers in Daejeon on Friday the 16th of May at 6:30pm.

Reader. It rained.

It was a tough week even before that. I was swamped in work and the Eagles ended their 12-game winning streak with three straight losses to the Doosan Bears, a team from Seoul and the ninth ranked team out of ten. It was rough. Thankfully our game would be against a new team, and we had that to look forward to, but the weather warnings were ominous. On the day it looked like all the other games in Korea would be cancelled but SSG vs. Hanwha would go ahead – right up until around two hours before the game was due to start. We got a mild consolation prize in the form of not having to leave my daughter’s kindergarten festival early, so we got to see her and her classmates perform some chaotic noise that was a lot like singing (and incredibly cute). Unfortunately, in Korea there is no rain check – we got a refund, but we would have to buy tickets again from scratch!

The tickets for the make-up game on Saturday afternoon went on sale at 9pm and despite getting into the queue as soon as humanly possible we were unable to secure tickets. After around two hours on the second-hand site my partner was able to get us new tickets for the makeup game, the first of a doubleheader. The new tickets even cost less than our old ones and were better seats (just past first base rather than outfield), but at the cost of several stressful hours. Still, we were on for baseball again and 2pm was a better time given that we were attending with a 5-year-old – she’s no stranger to staying up late but getting home at around 10pm after a 6:30 game is still a recipe for an over-tired kid and a difficult bedtime.

On Saturday the 18th, almost exactly two weeks after we started our journey into KBO fandom, we hopped in a taxi and made our way to the new Hanwha Life Eagles Ballpark to watch some baseball!

Having never attended a Major League Baseball game, only one or two Minor League games on school trips as a pre-teen, I have no direct source of comparison for what attending a KBO game was like. Even free of comparison I am struggling to describe the experience. It was amazing, I can say that for certain, and also far more physically demanding than I had expected.

When the Eagles were at bat, we sang. Our seats were in the middle of the cheering section and everyone stood, danced, chanted, and sang. Each batter had his own chant, some had more than one, and most had some form of dance choreography to go with the songs and chants. These could be simple, but some were very complicated. I never mastered when exactly we had to duck down during center fielder Florial’s song. Cheerleaders modelled what we were supposed to do and the lyrics to some of the songs were displayed on the stadium’s wall opposite us (in hangul of course), but mostly we copied the people sitting around us and tried our best to fit in. It was noisy, energetic, and a great time. The crowd’s dedication was truly impressive – no lacklustre performances to be found. Pure dedication to cheering the team on at bat.

The giant flags the fans waived at certain times (clearly on some kind of schedule that I was not aware of) were truly impressive. Believe me when I say that these were the smaller flags people had - some of them were so large it was hard to photograph.

I struggled with the dancing and made no attempt to sing the Korean parts of the songs, preferring instead to join in with the bits in English or the player’s names which were usually shouted the loudest anyway. At times I also found myself paying far more attention to the cheering and dancing, and my own feeble attempts to mirror them, than to the actual baseball being played. My partner, a seasoned Kpop fan and frequent noraebang attendee, was far more ably equipped for this side of the experience, and in fact preferred it to the baseball.

We were granted a bit of a reprieve when the Eagles were pitching, but thanks to our current star pitcher Cody Ponce that usually wasn’t for very long – he pitched a no-hitter for the first seven innings (tying the league record for most strikeouts in a single game and beating the previous Hanwha record of 17 set by his current teammate years previously) so we would quickly be back on our feet to sing again. At some points we would even stand to cheer Ponce on, especially in the later innings as he approached the league record of 18 strikeouts.

As this moment approached everyone got really excited - the crowd even booed when it looked like Ponce would leave the game after 17 strikeouts. I’ll admit that we didn’t exactly know what was happening, but the energy was electric.

While Ponce probably deserves credit for winning the game and all that, the real MVP of my baseball game was the guy in the row in front of us. Part of a group of middle-aged Korean men who clearly came to games often, he led crowd chants, high fived everyone around him (including us) every time there was a big play, and just generally brought an infectious energy of excitement (and despair, when plays went badly) to the rest of us. His greatest service, though, was to my daughter.

My daughter is five years old and certainly some kind of neurodivergent (she’s too young for a formal diagnosis). This was most relevant at the baseball game because she was struggling with the noise of the crowd and the sea of people around her – she is cripplingly shy, hiding whenever she receives unexpected attention (a frequent hazard when one is an adorable five-year-old, especially in Korea). By the second inning she was already kind of done with being at the baseball game. It was hot, it was loud, and she wanted to go home. This was obviously a terrible outcome for us – tickets were not easy to come by, and we were having a great time, but spending a day with a suffering child is no fun for anyone and we were trying to figure out ways to make the experience better for her.

Insert heroic guy in his pink Eagles jersey from the row in front of us. At the start he gave my daughter a pair of adorable little keychains, but his true service came around the third or fourth inning (I forget exactly which) when he returned to his seat with bright orange slushies for his friends – and three for us! Handed over with bright smiles (I speak almost no Korean, my partner was away investigating a snack she could get our daughter, and my daughter, while she speaks passable Korean, was far too shy to talk to a stranger) this gift almost single-handedly redeemed the day for my daughter. All she really needed was some cold sugar water to shift her mood and even after it was gone, she experienced baseball with a newfound enthusiasm. She even high-fived the guy and his friend (a stunning event, this girl does not interact with strangers) several times and his friend gave her a card with Cody Ponce in it at the end of the game. Truly these men were the baseball ahjussi that she needed to show her that this could be fun.

The hero and child whose day he saved (both anonymized for their protection and/or just to protect their privacy). Also pictured, me making a stupid face and my partner making a much more normal one.

While the row in front of us consisted of the middle-aged male crowd I was raised to expect from sporting events, on my left we had an example of maybe KBO’s largest fanbase at the moment: Korean women in their 20s. The woman next to me, who was eating a truly impressive multi-course Korean meal I think she bought somewhere in the stadium, spent the first half of the game in a state of relative calm. She danced and sang with the crowd, but in contrast to the heroic older men in front of us her participation was relatively sedate. This is no dig at her, if anything my energy was much more in line with hers than with the men in front of us, but it belied a deeper enthusiasm that only manifested as the game develop.

The Landers didn’t get a single hit first seven innings, but the Eagles had only scored one run in that time, so the game was still tight. Cody Ponce had delivered a remarkable record, but by the eighth inning you could see the exhaustion arriving. The game got more exciting, but in a stressful way. A heroic throw from right field all the way home, combined with a brilliant bit of movement from the catcher, spared us disaster as the runner was tagged out after a huge hit got the batter to second base, but we were all screaming the whole way. It was at this point that my neighbour’s enthusiasm showed. She had clearly been waiting for the moment of maximum tension before she exploded into screams of despair at every missed ball by the Eagles, switching to elation at the dramatic save by the outfielder/catcher pair. While relief pitcher Kim Seo-hyeon (on my short list for favorite player) was a safe pair of hands to finish the game with, it was a tense final two innings as we failed to get any more runs. My neighbour’s transformation in many ways mirrored my own experience – it is one thing to be up 1-0 during a potential no-hitter in innings 1-6, but to only have one point spare at the end of the game is another matter.

Seo-hyeon came through for us, though, and delivered the game at the top of the ninth – we screamed, we high fived, we celebrated, and we rushed to get the five-year-old to the toilet. She had first indicated she might need it during the climactic moments of the final inning and had to learn an important lesson about timing.

Kim Seo-hyun delivering victory to the Eagles.

Hanwha would go on to lose (decisively) the second game of the double header. We watched the second half of that game, which was played in the rain, at home with our dinner thankful that we had missed both the defeat and the inclement weather.

The experience of watching the game live was fundamentally different from watching it on the TV. The live experience was significantly more human. There were our fellow fans in the crowd, of course, and the interaction with them, but the chants also helped to reinforce the personalities of the individuals who were playing the game. On TV I struggle to know the names of the players because the displays, and the player’s jerseys, are all in hangul (which I’m embarrassed to say I still can’t read, but I’m trying!) In the stadium the main board displays the names in the Latin alphabet with pictures of each player, so I learned the names and positions much faster than I had watching from home where we usually identify players by their numbers or a distinctive feature (first baseman, and team captain, Chae Eun-seong’s glasses being a notable example).

The display board was a huge help, especially when I needed to know what name to sing when we were at bat.

While I maybe had a harder time following the grand scope of the game, placing each at bat or pitch within its full context and seeing how it was developing, I more strongly felt the struggle between players and empathised and rooted for them as individuals. Both experiences have their merits, and while I preferred the in-person game to watching it at home I’m not sure I could handle going to a game like this six days a week (assuming I could even get tickets of course)!

In the days leading up to the game, I was talking to a student at the university I teach at about sports and he told me he can’t stand watching KBO because he doesn’t think the quality of play is good enough to be enjoyable. He prefers basketball anyway and even in that sport he follows individual players rather than teams. Later I thought on this and how there are many ways to engage with sports.

Once upon a time I think I enjoyed watching individual prowess on display and probably preferred the Olympics to all other sporting events, but over time that has changed. Possibly this is my aging, but I bet no small part of it is also me becoming jaded as scandals have shown how many top athletes are basically cheating to achieve their records. Instead of rooting for someone who may be doping or otherwise engaging in nefarious practices to secure that tiny edge that makes all the difference in top tier sports, I prefer to invest in the human stories of players who are good, but maybe not the best. This is possibly also part of why I enjoyed the human connection I felt at the live KBO game so much – sure our star pitcher is an ex-MLB player who moved here after ending his tenure in the Japanese league, but here it doesn’t matter because here we’re all rooting for the home team, and he can help us finally win!

The level of play in KBO is certainly not the same as in MLB, but there is something wonderfully human about it. Also, if I’m completely honest, the games are more fun when people make mistakes. I’m not necessarily here to see the greatest game of baseball ever played. I’m here to see the home team win!

I very much hope to attend another game this season. It’s still relatively early in the season with nearly a hundred games remaining, so I’m optimistic we will be back at Hanwha Ballpark again. For the moment, my partner will keep an eye on tickets (tickets are released for sale exactly a week before each game) and hopefully we can get lucky. In an ideal world we could go every two weeks, but I doubt we will be so lucky. If you do get a chance yourself, I recommend attending a KBO game. It’s a hell of an experience.

May 25, 2025

The Wilderness Campaign ed. Gary W. Gallagher

As I child I spent many days in The Wilderness. My father was something of a Civil War buff and on the weekends he would, in moments of desperation, put my brothers and I in the car and drive us to a nearby battlefield where we could run around to our heart’s content. As a result, I have visited the battlefields of central Virginia countless times. The Wilderness was always my favorite. I could say it was because of some enduring fascination with those violent days in May 1864, but in reality, that came later. The Wilderness is fundamentally just a dense forest, and as a kid who liked being outside in the woods that made it infinitely more appealing than an open field.

For all the time I’ve spent wandering those woods (most recently in 2023 with my daughter, because these traditions must be passed down), my knowledge of the battle was pretty limited. On my last trip I decided to correct this by grabbing a book on The Wilderness from the Chancellorsville visitor’s center (there isn’t a dedicated center for The Wilderness, but Chancellorsville is spitting distance). That book was The Wilderness Campaign, a collection of chapters edited by the eminent Civil War scholar Gary W. Gallagher, whose edited volume on the Lost Cause I really enjoyed.

Edited volumes can be a bit of a gamble, at least when it comes to learning about a new subject. I have read, and enjoyed, many edited volumes that while they contained interesting chapters the overall work failed to cohere together enough for me to consider it a good book on its stated subject. In these cases, the individual articles provide great insight into aspects of the subject, but there is no connective tissue, and certain concepts may be overlooked. Those books can still be excellent, but they are a supplement to other reading, not an introduction for a relative neophyte.

What I prefer, though, are books that manage to focus on individual aspects of their subject in each chapter, but the chapters as a whole have been carefully selected to create a coherent work. The Wilderness Campaign is an excellent example of this latter type. The first three chapters discuss the lead up to the Overland Campaign through discussion of Grant’s relationship with the press, and the expectations that were set for his coming East, a reexamination of the morale of the Army of Northern Virginia in early 1864, and a thorough analysis of the how the Army of the Potomac was reorganized to prepare for the coming campaign. The battle itself is told almost vignette style thanks to chapters on the poor performance of the new Union cavalry officers (most notably Sheridan) taking command in the Army of the Potomac, the performance of the Confederate generals Ewell and A.P. Hill’s in the battle, a narrative discussion of the actions of the Texas brigades and their “Lee to the Rear” incident, the hard fighting of the Vermont brigade, and finally the dramatic Confederate flank attack that ended in General Longstreet’s serious wounding. Together these chapters create a larger picture of the battle as a whole.

While not necessarily as comprehensive as Rhea’s hefty volume on the battle, which I will have to tackle soon I expect, The Wilderness Campaign does some deep digging, and I think encourages lively reconsideration of long held truths about the war in 1864. I don’t want to drone on about each individual chapter, but here are a few I had some thoughts on.

Brooks D. Simpson’s chapter on Grant and the northern press was a thoroughly satisfying deep dive into a subject that is often mentioned but only briefly in other works. The role of the press and public opinion in influencing military policy cannot be ignored, but most general histories of the Civil War don’t have space to really dig into it so it was great to read a deeper exploration of its impact on this campaign. It is particularly relevant to the beginnings of the Overland campaign as Grant came east with such high expectations but knew that the summer ahead would be a brutal slog, not a quick victory. I will also confess that it had not occurred to me just how much of an influence Napoleonic era warfare had on public perception of the Civil War, as writers and their audience were both constantly looking for an American Waterloo.

I’m partial to any dedicated re-examination of a long-held historical truth, so of course I devoured Peter S. Carmichael’s chapter on Ewell and Hill and their performance at The Wilderness. These two generals have never had a particularly sterling reputation, and Carmichael is not determined to redeem them in general. Rather, Carmichael sets out a strong argument that their specific performance at The Wilderness was not so poor as is often held and that historians have too often relied on the memoirs of their subordinates, who were incredibly hostile to both generals. Carmichael shifts much of the blame for Ewell and Hill’s failures at The Wilderness back up the chain to Lee – a figure that postwar historiography was determined to absolve of all mistakes – and points to effective command in the moment by both generals in less-than-ideal circumstances. I found this a compelling argument that added a lot of nuances to a narrative that often tends towards simplicity.