Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 3

March 3, 2025

Labyrinth: The War on Terror by Volko Ruhnke

I was twelve when the War on Terror began, not quite fourteen when American invaded Iraq. The political and global climate created in the aftermath of 9/11 defined some of my most formative years – the time in my life when I first became aware of politics and tried to become politically active for the first time. By the time Labyrinth was released in 2010 I was in my twenties and living in Ireland. Labyrinth isn’t unique in being about a still ongoing war whose conclusion was far from determined when it was designed and published, but it is still a rarity within the hobby. That it was on such a major conflict, and one whose casualties extended well beyond a traditional notion of battlefields, certainly drew a lot of attention to it, as did the fact that its designer Volko Ruhnke was an analyst with the CIA at the time. Playing it fifteen years after its initial release, after America’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 marked what is often considered the end of the War on Terror, is an interesting experience. This is not exactly a historical game, it was not made with enough distance from the events it covers for any real historical hindsight, but it captures a certain perspective on events of the time that we can look back on now and try our best to evaluate. It’s also an incredibly well-designed card-drive wargame (CDG).

GMT Games kindly provided me with a complimentary copy of Labyrinth and both its published expansions.

I first became aware of Labyrinth years ago, probably around 2011, and I first acquired a copy in 2016 with the release of the Awakening expansion. Sometime in the next year or so I played half of a game with a friend to learn the rules, but we never managed to schedule time to play a proper game. I ultimately traded it away in an attempt to reduce the size of my collection before moving house. It, along with Falling Sky (another Volko design), were markers of a previous unsuccessful attempt to “get into” wargaming. With the recent reprints of both Labyrinth and Awakening (the first for the latter), I decided that this was my opportunity to rectify my past failure and, equipped as I am with more experience in the hobby, finally play Labyrinth.

While I’m an established fan of Volko’s Levy and Campaign series and I would classify myself as broadly fond of the COIN series, my previous experience with his other CDG, Wilderness War, was not particularly favorable. I found that game incredibly obtuse and far mor complicated than its (relatively) thin rulebook would indicate. A lot of complexity is buried in its deck and after one play I haven’t been particularly excited to revisit it. It even made me wonder if heavier CDGs were my thing. This meant I had some trepidation about revisiting Labyrinth, after all these years would I just hate it?

Where Wilderness War is rooted in the tradition of point-to-point CDGs like We the People/Washington’s War or For the People, Labyrinth seems to draw more from the most famous CDG of all: Twilight Struggle. That is a slightly misleading notion, though, since where I could happily classify Wilderness War within that broader tradition of operational/strategic point-to-point CDGs, Labyrinth stands out far more as a unique take on the genre. It takes elements from Twilight Struggle and its ilk but carves out a distinct position somewhere between the two traditions, one that I’ve not seen before or since (not that I’m the world’s expert on this specific genre). Perhaps that’s because Labyrinth has a clear successor in the COIN series, but while it is easy to see the roots of COIN in Labyrinth it is an oversimplification to view this game as just an origin point. It is very much its own thing.

That’s enough vaguery, at some point we must consider what Labyrinth is. Labyrinth is played on a point-to-point map of boxes representing countries and regions in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, with a few fringe boxes for parts of East Asia and North America. Players compete over the status of Muslim majority countries (excluding Iran), trying to shift their level of governance across four levels ranging from Islamist Rule to Good and between political positions as an Ally, Neutral, or Adversary to the United States.

While played on a point-to-point map, you won’t be moving armies between these locations. Instead they are important for determining adjacency for some die roll modifiers and moving Jihadist cells without making a roll.

Victory is primarily achieved through manipulating these states, the US wants a certain number of national resources (each nation has a value based on its wealth) to be under Good governance while the Jihadist player wants the same but under Islamist rule. Both players also have an instant win condition, either eliminating all Jihadist cells on the map or detonating a WMD in the US. The Jihadist player will move wooden pieces representing cells between these regions, using them to trigger plots or enact terrorist violence, while the US player can drop in cubes representing armed forces into friendly or hostile countries, effecting a regime change in the latter. So far, so CDG: you have actions to take, you can spend Operations Points to take them.

If only it were so easy. In Labyrinth you will be rolling dice, lots of dice, and those fickle little cubes will ruin your plans. The Jihadist player must roll for essentially every action they take, constantly playing the odds and hoping that crucial actions come out in their favor. The US player has far more luck-free actions available but their main path to victory is via the War of Ideas action, which shifts the status of Muslim nations, and that is up to fate. While in individual moments I found myself cursing these rolls, on the whole I love them. You make so many dice rolls over the course of the game that the luck will balance out, assuming you make good choices about when to push your luck to the extreme by hoping for that 1 versus opting for safer plays. You must play your odds and not put all your eggs into one roll.

It dovetails nicely that Labyrinth is a game of creeping progress. Like its Volko-designed COIN descendants, this is a game that develops slowly with players achieving incremental progress rather than big blow out plays that shift the tide decisively in one big moment. Much of what you achieve on a given turn will be undone by your opponent on theirs, but over time you can shift the global position in your favor. It is a game to be played in a broad scope – nudging your way towards victory each turn while also putting out fires as much as possible.

You will have a turns where you achieve absolutely nothing because the dice were not in your favor, but the same is true of your opponent. Global change can feel glacial. That is not to say that Labyrinth is boring. It is incredibly tense. I have never felt secure in my position during a game in Labyrinth, even when it turned out I was only a turn or two away from victory. The dice giveth and they taketh away, and you can play the odds towards victory but you can never be confident in them. I was reminded frequently of a description designer Dan Bullock gave of playing Twilight Struggle for the first time, namely that it was like having a stomach ache for several hours (in a good way). I feel that way about Labyrinth – although I’m probably not as fond of the sensation as Dan was.

The card play helps, somewhat, to mitigate the at times comic chaos of trying to take actions. Each player plays two cards on their turn, resolving the first entirely before playing the second. This is a system I’ve never seen replicated in other CDGs and introduces an interesting tempo to Labyrinth. As in Twilight Struggle and its descendants, enemy events are resolved when you play those cards for Ops, for your events you must choose events or Ops. Because you play two cards, you can sometimes play an enemy event first and then mitigate it’s outcome with a second card play. It can also allow you to set up some key combos as you play back to back cards, using the second to capitalize on the opportunity created by the first. At the same time, you must be afraid of your opponent doing the same to you, particularly as the Jihadist player can achieve automatic victory by detonating a WMD in the US, which always keeps the US player on their toes.

The combo potential of Oil Price Spike is particularly potent. There are two copies in the deck and since they both let you dig into the discard (always a fun, but dangerous, mechanism) and adjust the value of certain countries on the map for victory determination they can give you that final push to victory at a critical moment - if you draw one!

Before you begin a game of Labyrinth you must first decide how long you want it to be – measured in the number of times you will cycle through the deck. I have yet to play a game of three cycles, but most of my games have ended before then anyway. A single deck cycle feels a bit too short given how slowly the game develops – a victory by tiebreakers seems almost inevitable unless someone gets very (un)lucky. Two decks has so far been the sweet spot for me in terms of letting the game breathe and develop. However, at two decks Labyrinth is not a short game. I played most of my games asynchronously via the Steam app – a decent but not perfect implementation in terms of usability – which helped mitigate this to a degree. A game being long is no great criticism, it is almost the norm within wargaming, and each turn of Labyrinth moves along at a good pace when you get going but at the same time I don’t know if I love how long it can take. I have similar feelings about some of the COIN games where I just wish they moved a bit faster, but at least since Labyrinth is two players I don’t have to wait so long for my turn.

I don’t love the multiple cycles of the deck as a system for determining length, though. I appreciate that Labyrinth has a timer – if it was just a “play until someone wins” situation, the games could drag on for an eternity. However, I generally prefer unpredictability in my CDG decks – games like Here I Stand or Successors where the deck is reshuffled every turn.

In Labyrinth, to play well you want to know the contents of the deck, especially if you’re going to (potentially) see every card in it two or three times in a game. At the same time, I haven’t found that many instances of events that totally negate a play (i.e. if a player doesn’t know about that event before the game begins, they’re going to have a very bad time) and the few that exist you can learn quickly.

Perhaps two of the worst offenders that you have to watch out for, since they can instantly change the governance of a country. Ethopia Strikes can undo the enormous effort required in making a country Islamist Rule in the first place, while Musharraf can punish either player but can also be blocked. Still, these are in the minority and they can be managed.

Both sides also have ways of burying events, which is generally a must in games like this but I like how in Labyrinth they’re asymmetrical. In general the events in Labyrinth feel useful but not amazing, so the game strikes a good balance where you will play most of your cards for Ops with one or two key events a turn. I spend more time thinking about the order to resolve the enemy events I have in my hand than my own, which feels pretty par for the course for this style of CDG.

I have played six games of Labyrinth at the time of writing, and in true Volko fashion I feel that I am only now really coming to grips with it. This is partly due to the depth of the design, but just as much it is due to the asymmetry. The US and the Jihadist players are playing fundamentally different games. For my first few plays I was the Jihadist and once I had come to terms with how my faction played I still had no idea what my opponent was doing – which made for a pretty weird first few games. There probably are people out there who can grasp Labyrinth during their first game, but for me it took 3-4 plays to even understand every aspect of how the game works. In this regard the app version isn’t entirely helpful, and I learned a lot by setting up the physical game and playing it solo two-handed. Even then, it took a while for the importance of some systems to sink in. For example, for my first few games I didn’t really understand why the Ally/Neutral/Enemy status mattered for countries as I was entirely focused on level of governance, then I started playing as the US player and it became immediately apparent that the status was incredibly important. There is so much to unpick in this design and the two sides are so different that it could take me dozens of plays to really understand every aspect of Labyrinth.

However, I’m not sure if I want to put in those dozens of plays. I’ve enjoyed every game of Labyrinth I’ve played, but after six games my enthusiasm to play it again is waning. I feel like I’ve seen a lot of what it has to offer and while I could pursue greater mastery of its systems, that isn’t really why I play historical games. Not that I’m finished with Labyrinth, I could still see myself pulling it off the shelf again next year to try it again It is worth revisiting, assuming I have someone to play it with, which isn’t a guarantee given the game’s subject matter. I can’t exactly blame anyone for not wanting to play a game on the War on Terror. I may want to stick my head back into this historical mess every twelve to eighteen months, but not everyone will want to even do it once.

Usually I like to spend some time analyzing how a game captures the history it purports to portray, but that’s not exactly possible with Labyrinth. Labyrinth was published approximately midway through the War on Terror, not that we knew that then, and is ostensibly about the opening chapters of that war, but I don’t think that’s what it’s really about and so I don’t believe it to be particularly valuable to dig deep into how well it captures how the Global War on Terror developed in its opening years. There are historical elements in the game that don’t feel particularly believable – chief among them are how every game I play involves an intense fight over Pakistan whose descent into Islamist Rule releases WMDs for the Jihadist player to use. Similarly, nation building seems far too easy for the US player. Sure the game makes deploying large scale forces to a nation costly and you do risk getting bogged down for a few turns, but the game doesn’t seem capable of replicating the two decades that the US spent trying to reshape Afghanistan only to ultimately, and decisively, fail.

But I don’t think that’s really what Labyrinth is about. Labyrinth is about the neo-con mindset and the worldview within US politicians, military, and intelligence services that motivated the War on Terror and informed their decisions. This is the opening years of the War on Terror as American decision makers saw it. It’s no coincidence that one player plays a coherent political entity, the US, while the other is playing a total fiction, an international network of Islamist jihadists spread across the globe. At no point was any radical Islamist faction ever as unified in its purpose or goals as the Jihadist player in Labyrinth is. This is not wholly uncharted ground – Twilight Struggle famously has systems to represent the Domino Effect, because even though the Domino Effect was nonsense the belief in it was highly influential on US decision makers and Twilight Struggle seeks to capture those decisions and that mindset. Labyrinth takes this to a new level where instead of being just a couple of systems it is the whole game.

This emphasis on a specific near-contemporary mindset is a fascinating choice, and turns the game itself into something of a time capsule when it is played decades later. However, it also makes for a pretty intense playing experience, especially if you have rather mixed to negative feelings about the Global War on Terror, as I do. I believe that all historical games should bring some complex feelings about their subject to the table, history is complicated and messy, but this is history that I lived through and that helped to shape who I am. I think Labyrinth does a pretty good job at keeping these elements on the surface rather than burying them within the game, even if its scale doesn’t leave much room for the human tragedy that accompanied this “war”. It could do more to dial in to the darker elements of US geopolitics of this era, but I also don’t think it makes a simple toy of its subject either.

As a game I enjoy Labyrinth while as a historical artifact I find it engaging and conflicting. It’s not my favorite style of CDG but it is probably my favorite example of its type – if that makes sense. I have been thoroughly engaged every time I played it, but I am also coming to an end of my desire to keep playing. That said, Labyrinth is somewhat of a rarity in the wargaming hobby in that it is blessed with multiple expansions. I have both of the currently published ones, and I am interested in seeing how designer Trevor Bender modifies Volko’s core system to cover new eras of the War on Terror. I am also very interested in how Peter Evans’ prequel expansion will take this system of contemporary political positions and apply it to a period long enough ago that we can actually apply historical hindsight to it – essentially turning the game into a true “historical” wargame.

Labyrinth isn’t a game that I would ever offer an unqualified recommendation of. Its subject matter alone makes it hard to universally recommend – most people will know instantly upon hearing what this game is about whether they would want to play it or not. What I can say is that while my initial enthusiasm for the game from first hearing about it in 2011 had faded in the intervening decade. As I played more CDGs I also began to worry that Labyrinth would not be a game for me. Having played it, I am happy to report that I am incredibly impressed with it. This is a masterful piece of game design that still manages to stand out from the field in modern wargaming. It is also so much more than just an originator that made COIN possible – in fact I probably prefer it to most COIN games I’ve played – it is an amazing and unique game in its own right. If you are a fan of CDGs, or just of interesting game design, and the subject matter isn’t a dealbreaker, then you should definitely try Labyrinth. Probably a couple times, because that first game is really confusing.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

February 12, 2025

Thematic Integration in Board Game Design by Sarah Shipp

Trying to explain to someone who doesn’t play board games why this game about trading feels thematic but that other game about trading has a pasted-on theme is, in my experience at least, a ticket to a conversation that both of you lose interest in once you’re far too deep into it to easily back out. That is why I don’t envy Sarah Shipp’s task in trying to define concepts like a board game’s theme and when theme integrates well with a game’s mechanics. This is the sort of thing that is intuitive to many who have spent time in the hobby – they know thematic games when they see them – but despite what some American jurists might believe this is not particularly firm ground for a working definition. In Thematic Integration in Board Game Design Shipp sets out not only to define and explain these concepts in a manner that can serve as a foundation for future discussion, but then to also provide advice to designers on how best to effectively integrate their game’s theme with the mechanisms and rules.

Most of the book is aimed towards designers rather than people like me who ruin parties by bringing up board game themes. It is far more of a guide to designing thematic games, including literal guides to doing this at the end of the book, than it is a deep discussion of how theme and mechanism interact. Despite that, my favorite parts of the book are probably the early sections where the challenges of defining theme are most prevalent. Shipp is faced with taking terminology that has developed on internet forums and in casual discussion (e.g. “pasted-on theme”) and attempting to refine them for a more robust academic discussion. This is always a fraught process at the best of times and runs the risk of multiple authors introducing different sets of terminology for the same topic, creating endless confusion. Shipp does an excellent job at charting a course with her chosen terms (in particular, talking about themes in layers and how well the games interlock with the theme). Shipp shows an appreciation of the need for academic language without getting lost in the mazes it can create. That’s not to say that the opening chapters don’t at times get a tad labyrinthine, but they generally deposit the reader in a clearing with a working understanding of the language that will be used throughout the rest of the book.

Readers who don’t particularly care about thematic games may object to the fact that the book takes thematic games as an inherently desirable outcome, but then if you are reading a book on integrating theme into board games, maybe you shouldn’t be surprised that it unabashedly supports integrating themes into board games. The chapters on narrative and designing characters within your game were particularly rewarding reading, and I very much appreciated the reminders that a game can have too much theme in addition to having too little. However, the book’s best aspect, to me at least, is how Shipp encourages a wide engagement with art. This is most explicit in the section on research, but throughout the book she encourages readers to watch films, listen to podcasts, read books, and play other games. Familiarity with a wide variety of cultural material is essential to developing good themes and avoiding falling into boring tropes that have been used many times before.

As someone with no published game designs, and no hobby-style designs in the works, I can only provide so much commentary on how well the book works as a how-to guide for designing thematic games. I certainly found the arguments engaging and I found myself periodically spacing out and losing my place on the page because I was thinking about game design – which is usually a good sign, at least for this book’s subject matter anyway. It helps that Shipp herself is a published game designer and does an effective job at using her own designs to make several of her points, so the advice feels like it comes from a place of experience and not speculation.

I have one or two minor nit-picks. Many current hobby board games are mentioned throughout the book, but often how they work is explained only in a cursory fashion. For readers who are already familiar with modern hobby games this will pose no real barrier to understanding, but I could see those from outside the hobby finding it hard to follow in places. Some of the end notes encourage readers to look up Let’s Plays of the games, or try them for themselves, and there are certainly ways for people to get over this hurdle, but I would maintain that it is still a (small) hurdle. Detailed breakdowns of each games’ rules would likely have bloated the book to an unreadable size, but a little more detail would have helped. In particular, many games are simply described using their core mechanic, e.g. X is a deck-building game or drafting game, without defining the mechanism. Even if just a one or two sentence endnote, a little more detail would have been welcome.

I would also have preferred it if the author made more of an effort to mention games’ designers, especially in the section at the end of each chapter that lists the games mentioned in the chapter. It is simply a list of game titles, but I would have expected it to include the designers at a minimum and possibly also publishers, artists, and years first published, for a more complete ludography.

Overall, Thematic Integration in Board Game Design is a great book. There is plenty here to spur the imagination of a current or potential game designer and even as someone who probably won’t work in the space this book focuses on (it’s entirely hobby game focused, very little discussion of wargames or TTRPGs, for example) I still found a lot to benefit from here. It’s a great start to CRC’s new series on tabletop game design. Here’s hoping the trend continues with future volumes.

February 2, 2025

The Army of the Heartland by John Prados

In the niche within a niche that is operational games on the American Civil War the Great Campaigns of the American Civil War (GCACW) series looms above all others. Despite arguably draining much of the oxygen from the field it does not hold a monopoly on the topic. John Prados, the designer of Rise and Decline of the Third Reich among other legendary titles, threw his hat into the ring before GCACW had even fully materialized. The Campaigns of Robert E. Lee was published in 1988 by Clash of Arms games, the same year as Joe Balkoski’s Lee vs Grant – generally considered the predecessor to GCACW – was published by Victory Games. While Stonewalll Jackson’s Way, also by Balkoski, was published in 1992 by Avalon Hill, ushering in the GCACW, it would not be until 1996 that Prados provided his own sequel: The Army of the Heartland, also published by Clash of Arms. Comparing Prados’ games to GCACW is instinctive: both are operational games on the ACW by legendary designers with established pedigrees that were released at approximately the same time. They also share certain design ideas, most notably random movement and the unpredictability of whether an attack will even happen let alone go well, but at their core they are very different designs. Rather than a cousin for GCACW, I see similarities between Prados’ series and another legendary series that first appeared in 1992: Dean Essig’s Operational Combat Series (OCS).

Before we get into it, let me throw out a few qualifiers. This is not a fully formed review – I have only played one and half games of Army of the Heartland at time of writing. Instead, this is a collection of initial thoughts and impressions on a game (and series) that has received relatively little attention. For reasons that will become clear I don’t believe that Army of the Heartland is an all-time great design, it does many interesting things, and I had more fun than I expected with it, but it also has its problems. That said, it deserves a better reputation than it has, and it is a game worthy of study. If it had received a comparable amount of attention and polish that GCACW and OCS have over the past thirty years it could be a real gem.

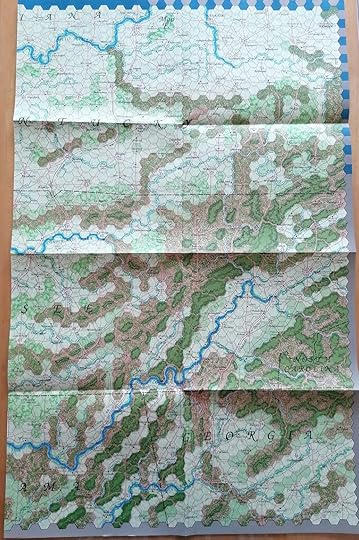

Army of the Heartland is an strategic-operational game on the western theater of the American Civil War covering campaigns from 1861-3. It is played on two maps by Rick Barber, which stretch from Appalachia in the east to the Mississippi River in the west. While this canvas is broad, the focus is really on western Tennessee and Kentucky. Vicksburg lies off the maps western edge, so rather than focusing on Grant’s many campaigns in the Mississippi the emphasis is on the fighting between the Army of Tennessee (after whom the game is named), mostly under Bragg, and several Union generals, notably Buell and Rosecrans, who opposed them in the eastern half of the western theater.

I’m not the most diehard Rick Barber fan but this map is very pretty, and printed on a very nice paper stock. This is the eastern map where you will be spending most of your time.

That’s what the game is about, but it doesn’t say very much about what the game is. Army of the Heartland has a dense and respectably long rulebook, so digging into every detail here would be impractical. Instead, I will focus on the elements that stood out. First and foremost among these are the army displays. Both sides have an approximately A2 sized sheet with boxes for each of their generals (although in the largest scenarios these may need to be shared between multiple generals). Each box contains the units under the general’s command as well as a track for recording the administrative points, morale, number of guns, and amount of ammo that general has. In the case of overall commanders, lower ranking generals may also be included in this box. This immediately gives the game a strong fog of war element as you can only see where the generals are, not the size of their forces or even whether they are commanding multiple lesser generals. It also makes the game an enormous table hog – the size of the displays easily adds the equivalent of one extra map to what was already a two-map game (there are no one map scenarios, but I would argue that given the game’s attention it could have fit on one map), possibly more if you place the displays on opposite sides of the map to make it harder to see your opponent’s. For these reasons, I played Army of the Heartland on Vassal.

The army displays also have some more lovely Rick Barber (I believe) art. From a play experience I see the benefits of these large sheets, but as someone without a large American basement the size of them outweighs the luxury of having that extra space.

The second intriguing mechanism in Army of the Heartland is the bid for initiative. Scenarios give each side a number of operational points and at the start of a turn players will bid points to see who goes first – the winner spending War Effort Points for the privilege. The amount bid, and in subsequent turns where play alternates the amount of the remainder spent, will determine which table you roll on when determining each general’s movement that turn. This is somewhat reminiscent of how GCACW forces you to roll for movement every activation, but instead of taking the value of the d6 you take that result and compare it to a matrix factoring in the general’s movement value and the aforementioned bid. If you roll badly enough (and your general’s movement value is poor enough) you could even render that general inactive, forcing the spend of further War Effort Points at the end of the turn to reactivate them. Sadly, I must report that the Confederacy receives 50% more movement points than the Union. The good news is that this has an interesting impact on the bidding, since it encourages the Union player to bid higher values to get more movement to equal the Confederate player (effectively, they must expend more of his resources to undertake his campaign), which may result in them going first when they don’t want to, but I still wish this was tied to specific scenarios to reflect the greater burden for an army on the offensive rather than always tied to Confederate vs. Union.

In contrast to the above two mechanisms, combat in Army of the Heartland isn’t quite so unusual but I found it blessedly simple. Players add up combat factors, calculate DRMs (the cavalry ones could be simpler if I’m nit picking), and roll a d6 to find their combat result. There is no combat ratio, instead you compare your results – step losses are inflicted on each side and then the absolute value of the difference of the two Retreat results is applied to whoever got the lower amount, so if I rolled two retreats and my opponent rolled one, then they would retreat one hex. There are also potential morale losses and wounding/killing of generals (which is tied to a roll of a six, so you are more likely to win a battle and lose a general than you are to do so while losing one).

Perhaps the best wrinkle in the combat is how it begins. Zones of Control (ZOCs), the six hexes around each general, stop movement and force the enemy army moving into them to attempt an attack. The general rolls a d6 and must roll under their battle rating – if they succeed add an Assault token on them to be resolved after all your moves are finished, if they fail, they lose a morale, suffer a step loss, and retreat. Bonus DRMs accumulate if you can attack the same hex multiple times in a single combat step. The extreme punishment for failing to trigger an attack makes the decision of whether to move adjacent to an enemy intense, particularly if you want to hit one enemy from multiple hexes. This is reminiscent of GCACW’s rules for triggering an assault where a die roll determines how many of your units will participate, but in many ways, it feels worse/more stressful which kind of makes me like it more.

The final core element to the game is the many resources you’ll be tracking as you play. As mentioned, each general has guns, ammo, morale, and administration points. Ammo is spent using guns but if you run out your units fight at half strength, morale will go up and down depending on battle results and other factors (potentially resulting in units becoming broken), while administration points you will spend on various actions. These can be combining and separating armies, overall commanders lending one of their stats to a subordinate, or even attempting to make attacks (you can do the last one without spending points, but at a significant penalty). On top of that both sides have War Effort Points (WEPs), which are set by the scenario and spent to keep generals active, to replace generals, for winning the first activation in a turn, and on various other actions. WEPs approximately represent the supreme command for both sides, the capacity of the respective war departments. I found WEPs to be harder to comprehend – the values are so large (number in the hundreds in some scenarios) and the expenditure so relatively small that I couldn’t fully appreciate their significance. Some of the elements that you spend your various points on are clear and easy to understand, while other actions seem more niche and opaquer as to how they will help you achieve victory.

I quite like the counter art as well. The markers for the generals have their names on the reverse, which indicates their inactive state, so while you can check it will serve you well to be able to recognize the commanders from their beards.

It is primarily this last element that to me evokes the comparison to OCS. While the randomized movement and the difficulty in launching attacks both feel of the same line of thinking as GCACW, the game’s scale is much closer to OCS (hexes are 5 miles, game turns approximately half a week, similar to Lee vs Grant as well) and the focus is much more in-line with OCS, I think. The tracking of resources on individual generals is different from how OCS uses supply tokens to limit your actions, but both are games that put the logistical (and in Army of the Heartland’s case administrative) burden of warfare front and center. Army of the Heartland is also a game deeply concerned with maintaining supply lines, traced back to supply sources, often via depots built out of wagons (extenders anyone?), with some potentially brutal attrition rolls waiting you should you neglect this. That is not to say that GCACW has no concern for supply, but it is often pushed to the advanced rules and some titles (e.g. Hood Strikes North) discard the rules entirely as superfluous – something that I can’t see an entry in Prados’ system doing. In the campaign for Stonewall Jackson’s Way you check supply status twice, in Army of the Heartland you check supply twice each turn.

What Army of the Heartland lacks that OCS and GCACW share is a clear conception of what it is – a point of focus. OCS is a game of supply management and logistics to support its maneuver and exploitation systems while GCACW is first and foremost a game of movement (particularly with its fatigue system, which Army of the Heartland has no parallel to). Both systems have more to them than that, but if you were to pitch the games to someone those are the core elements you would lead with. While I would compare Army of the Heartland to OCS before GCACW, I don’t believe it has the focus of either. It has a jumble of systems and a mountain of chrome that dilutes its attention, resulting in an overall messier game. Of course, it also has not had the same rounds of revisions as the others – it received a second edition in 2004 (which I own), but OCS is on version 4.1 and GCACW is on 1.6 following a significant overhaul in the new versions published by MMP (to say nothing of the changes from Lee vs Grant to GCACW). I can’t help but wonder had Prados’ games received comparable attention and refinement they might have found their voice more clearly, but instead the desire to “simulate” the warfare of the period clouds the games intentions and reduces the quality of the experience.

I also find its victory conditions to be completely lacking. There is an automatic victory for whoever can control both Louisville and Chattanooga, but in many scenarios that is functionally impossible. It is also an odd duck when you consider the scenarios that focus on the western half of the map, such as the one for Shiloh and the Corinth campaign or the one covering the 1861 campaigns. Beyond that most scenarios come down to whoever inflicts the most losses on the enemy, with carve outs for attrition from lack of supply and several other factors – so cutting your opponent’s supply and causing them huge casualties nets you zero victory points (not that I’m bitter about that). This always parses weird to me for ACW games at a higher scale – the attacker nearly always suffered higher casualties historically, and most games replicate that, but ultimately Grant still won in Virginia, so pure attrition doesn’t strike me as a reasonable victory condition, especially with little in the way of alternatives. Given all the (at times nit-picky) detail throughout the rest of the design victory almost feels like an afterthought. While I kind of prefer its simplicity to the dozens of victory factors included in some GCACW scenarios, the latter overwhelms me while and the former leaves me unsatisfied, neither has me fully convinced. Show me the happy middle.

Because it’s what I do, I need to take a moment to talk about how Army of the Heartland portrays its subject. I initially picked up this game for the podcast We Intend to Move on Your Works, and my decision was made solely based on the cover. The front of Army of the Heartland shows the Army of Tennessee marching towards battle proudly waving the Stars and Bars and the “Orphan Brigade” flags against a backdrop of the battle flag. It’s a lot of Confederate flags for one image. I also immediately noticed the choice to name the game after the Confederate army operating in the theater. This is explicitly a game about the Confederacy. That it follows The Campaigns of Robert E. Lee and is in turn followed by Look Away (a reference to the song Dixie) reinforced that impression.

Seriously, look at that cover. Wow.

The game has a few elements that make me wince a little. The fact that Confederates pretty much always move 50% further (the only exception being the result where both sides only get one movement point) rubs me the wrong way much like the faster Confederate movement did in GCACW. I think the movement asymmetry has the potential to be more interesting here thanks to the bidding system, but I still don’t like that it is always the Confederacy who moves further. The ratings for Nathan Bedford Forrest which make him the best combat commander in the game also indicate a familiarity with the work of Shelby Foote, who heaped endless praise on the Klan supporting war criminal. Not that everyone who reads Foote is a monster, but his work is very Lost Cause-adjacent and has never been particularly scholarly.

On the whole, though, I found very little within the design beyond its initial framing that struck me as particularly influenced by The Lost Cause. The historical background at the end of the rulebook is remarkably even-handed. I could nit pick it, but for something that was written nearly thirty years ago by a non-specialist it didn’t throw up any red flags for me. I would like to know why John Prados chose the title and framing he did for the games in this system, but aside from that odd choice I found remarkably little to distress me in the game’s rules. Perhaps a deeper dive will turn up something, there is a lot in this game, but only time (and more plays) will tell.

I’m on the fence about Army of the Heartland. I enjoyed it far more than I expected, and there is an excellent game in there somewhere, but at the same time I don’t know if I want to keep it on my shelf. Its vast size makes it all but impossible that I will ever play the physical game, and the fog of war doesn’t make it particularly good for solo play anyway. I first played the start of the scenario for Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky in 1862, but a string of illnesses interrupted that game and when I found time to resume, I had forgotten most of how the system worked, which required a substantial relearning process. I settled on the shorter Stone’s River scenario for my second attempt (the right choice I think), and once we got going the game played much more smoothly than I anticipated, but the relearning process was brutal. The rulebook is adequate, laid out in the traditional (and not great in my opinion) sequence of play order, but there’s just so much chrome and other little things that I never felt confident that I fully understood it. It also lacks an index, which makes finding specific rules (where in the sequence of play is the rule for unit morale?) a pain. I’ve learned to play more complicated games, but they were also generally more intuitive, and I just see the inertia of not playing Army of the Heartland outweighing my genuine desire to revisit this title.

I think I will try and acquire a copy of Look Away, the third and final entry in this series. Look Away was published in an issue of Against the Odds magazine and so has a smaller footprint – one map with army displays that have been reduced to a single page each. It also covers the Atlanta campaign, which is one I have an enduring interest in. If Look Away convinces me that this system is worthy of return visits then I will open my copy of Army of the Heartland again – who knows, maybe it will even encourage me to punch and clip it in hopes of finding a table large enough to play on.

I can’t universally recommend Army of the Heartland – taken as a whole, I think the design is not quite there. However, it is chock full of interesting ideas and the moment-to-moment gameplay of the turns really is very fun. If you are a fan of operational Civil War games or if you’re a designer looking for a system that with a little refinement could sing, then you should check out Army of the Heartland or one of its siblings. I don’t know if it’s currently up to snuff as a challenger to GCACW, but with the right coach and a few drills it might be a contender.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

January 25, 2025

Most Anticipated Games: 2025 Edition

It’s almost Lunar New Year (shout out to fellow Year of the Snake people), so what better time to take a moment and look to the year ahead? Last year I did a most anticipated games list, and since it was pretty good fun, I decided to do it again! First, though, I want to reflect for a moment on last year’s list and see how I did both in terms of predicting what came out and what I managed to play.

Overall, I picked eleven games for my most anticipated list, of which only six were actually released in 2024, which gives me a hit rate of just above 50%. I expect three of them (Seljuk, Halls of Montezuma, and Cuius Regio) will probably come out this year while the two others (Libertadores del Sur and 1066: Year of Destiny) probably won’t. Of the remaining six games, I managed to play four of them. Pax Penning and Sedgwick Attacks both sit on my shelf of shame, but I am confident I can play at least Sedgwick Attacks this year. Of those final four, Tanto Monta was ultimately disappointing but the other three were a lot of fun. Two of them made my best of list for 2024. 1812: Napoleon’s Fateful March is the one released title from the list that I don’t own, and had I played more than one intro game it may also have made the best of list – it’s a fascinating design but I just haven’t played it enough.

So last year I got about half of my guesses right, slightly worse if you factor in that I ultimately didn’t like one of the games, so I have a target to try an exceed for this year’s predictions. In honor of my forgetting Pax Penning last year and adding it on to the end of the list after I published my post, I am once again choosing eleven games. The list is ordered based on approximately how confident I am in whether the game will come out this year rather than how excited I am for them. Without further ado, then, let’s get to the list:

Most Anticipated Games 2025By Sword and Bayonets by Allen Dickerson (GMT Games)I didn’t get along with Great Battles of the American Civil War when I tried Into the Woods and Dead of Winter, but I’m generally willing to give the series another shot and By Sword and Bayonets is promising to be a good entry point into GBACW. I’m not super excited about the chosen battles, but single map GBACW with a manageable number of units promises to avoid some of the problems I had when learning it before. Who knows, maybe I’ll fall in love and P500 the upcoming entry on The Wilderness.

Korea: the Fight Across the 38th by Trevor Bender (RBM Studios)I’m currently living in South Korea and last year I started what I intended to be a small project looking at operational games on the Korean War – it just so happens that at the same time there has been a surge in games on the topic. There was a solitaire game in a recent issue of Strategy & Tactics magazine, Vuca Simulations is supposed to be publishing an edition of Jun Tajima’s game from Game Journal, and there’s this upcoming game to be included in C3i Magazine. While I’m probably a little more excited for the Vuca game, there’s no real information on when it will come out while this should be out in the spring so it takes a spot on the list. I haven’t played any of the other games in the same system from previous issues, but they have been well received and I’m interested in seeing what this take on Korea looks like.

I would be remiss if I didn’t add that Rodger MacGowan, the man behind C3i Magazine and many other games, and his family lost their house and home office in the Palisades Fire. You can donate to their GoFundMe to help them recover and to get C3i back up and running as soon as possible.

Shakespeare’s First Folio by Kate Bertram and Kevin Bertram (Fort Circle Games)I’ll confess that this wasn’t high on my anticipated list when I first heard about it – I wasn’t sure if this was the kind of game I’d enjoy. However, the buzz I’ve heard from conventions has been great and I’m hoping this year to try some more historical board games of a less wargame-y form, because it’s nice to have something lighter to break up the complex hex and counter games. Also, Fort Circle always does amazing productions on their games and I trust Kevin Bertram to know what he’s doing both as a designer and developer. Ask me in a month and I could probably substitute another Fort Circle game in here instead. The slate of releases they have set for 2025 looks really promising.

Gettysburg the First Day by Steve Carey (Revolution Games)There is very little public information on this game yet, but it was being playtested at SD Hist Con last year and will supposedly be out this year. This is the next volume in the Blind Swords series from Revolution Games. Blind Swords is one of my favorite hex and counter systems and the first day of Gettysburg is an excellent subject to wargame – I love games with a large approach to battle element and the first day has that in spades. This topic was technically covered already by series originator Hermann Luttmann in a game from Tiny Battles Publishing, but I’m excited to see what designer Steve Carey and the development team at Revolution bring to this new take on the battle.

Oblique by Amabel Holland (Hollandspiele)I have a low-key obsession with Frederick the Great, especially since I read Tim Blanning’s excellent biography of him before visiting Berlin a few years ago. I also love games that introduce the challenge of managing supply and even if I don’t always love them I am continually fascinated by Amabel Holland’s designs. I love blocks. All of those elements together mean that I’m very excited to see what Amabel does with Prussia’s gayest king. I must also give an honorable mention to A Battle, Furious, Bloody, Repulsive, Crimson, Gory, Boisterous, Manly, Rough, Fierce, Unmerciful, and Hostile also by Amabel, I’m excited for the return of Shields and Swords as a system but skeptical of the dry erase map, so it only gets honorable mention status while Oblique secures a full spot on the list.

No Turning Back by Dean Essig (Multi-Man Publishing)There is a copy of To Take Washington sitting unplayed on my shelf, so perhaps I shouldn’t be getting too excited about more games in the Line of Battle series, but I’m a sucker for games about The Wilderness and as a newfound fan of OCS I can’t help but be excited by the release of one of the late Dean Essig’s last designs. Do I have room for four maps? Absolutely not. Do I have time to play it? Probably not. Will I pre-order it anyway? Almost certainly.

Thunderbolt Deluxe by Richard Berg, Mark Herman, and Alan Ray (GMT Games)I’m nothing if not a disciple of Berg. I don’t always love his designs (see previously mentioned problems with GBACW) but I think there’s always something interesting to his games and I love his approach to crafting a hypothesis for each of his designs. Thunderbolt is his opus that was left unfinished on his death – a massive operational scale ancients’ game and the final part of his trilogy on the subject. Mark Herman and Alan Ray are finishing the design and GMT are packaging all three games into one box, and I can’t help but be excited to try it even if it ends up being too big and too much.

The Pure Land: Onin War in Muromachi Japan 1465-1477 by Joe Dewhurst (GMT Games)I’m not the biggest fan of the COIN series – I enjoy it but I’m not a super fan, usually I’m content to move on after one to two plays of each entry. However, COIN’s take on pre-Sengoku Jidai Japan is the kind of thing that I can get behind – especially since it seems to tackle the role of the peasantry within the conflict rather than abstracting the populace away. I also generally trust Joe Dewhurst to know what he’s doing based on his previous development work for the series, so I’m tentatively excited. I want to give an honorable mention to Brian Train’s China’s War as well, which is another really interesting topic to tackle in COIN from a designer I have a lot of respect for.

Castelnuovo 1539 by Francisco Ronco (Draco Ideas)I’m a sucker for siege games and I’m a sucker for block games, put them together and you’ve got my attention. This is a game on a somewhat obscure (to English speaking audiences at least) siege of a Spanish garrison in Albania by the Ottoman Empire. Draco Ideas have made some excellent games, the production looks beautiful, and the subject sounds fascinating, fingers crossed the game is good!

Baltic Empires: The Northern Wars of 1558-1721 by Brian Asklev (GMT Games)Big multiplayer game about early modern competition in Europe with art by Nils Johansson? You better bet I’m interested! Brian Asklev designed 1812: Napoleon’s Fateful March which was on my list last year and is a fascinating game, and the buzz I’ve heard about Baltic Empires is that it’s amazing, so I’m incredibly excited. Because it’s a big multiplayer game I don’t know if I’ll get to play it this year (assuming it comes out), but I’m hopeful!

Crown & Courage by Petter Schanke Olsen (Tompet Games)This is only coming to Kickstarter this year, so chances are it won’t deliver within 2025 given how these things go, which is what earns it the bottom slot on the list. While Halls of Hegra, the previous game by this designer and publisher, won’t be making my top 10 favorite games list I was impressed with how it brought Eurogame mechanisms to historical games wrapped in a stunning production covering a subject I knew nothing about. I don’t know a lot about Crown & Courage but it promises to do similar things and so it has my attention.

Top 5 Most Anticipated Games I OwnLast year I also picked five games from my shelves that I was most excited to get to the table in 2024. I managed to play three of the five. Glory we covered on an episode of We Intend to Move on Your Works, I wrote a brief piece about learning Musket and Pike but ultimately I think Banish All Their Fears is more to my taste, and I am currently playing a game of Korea: The Forgotten War. Sadly, neither Give Us Victories nor Granada: Last Stand of the Moors made it to the table, and for that I will have eternal shame. Hopefully this year I can do better than 3/5, but I am reasonably happy with that result all things considered. Continuing the precedent, here are the five games I already own that I am most excited to play in 2025.

Give Us Victories by Sergio Schiavi (Dissimula Edizioni)Look, it’s simple, it was on last year’s list, and I brought it with me to Korea because I failed to play it then. I’ve clipped it and sorted everything into trays and bags. I swear this year I will play this game if it kills me.

The Korean War: June 1950-May 1951 by Joe Balkoski (Victory Games)Next on my list of Korean War games once I’ve finished playing Korea: The Forgotten War. This is often held up as the gold standard for games on the Korean War and my copy of the Victory Games edition is clipped and sorted. Balkoski has certainly proven his operational game design chops to me via the Great Campaigns of the American Civil War series, so I’m very excited to see what he did with “The Forgotten War”.

A Greater Victory: South Mountain, September 14, 1862 by Steve Carey (Revolution Games)I have three Blind Swords games on my shelf right now, and if you’d asked me last year, I probably would have picked one of the others as my most anticipated since they’re on Chancellorsville and Vicksburg, two battles I have a longstanding interest in. However, playing Fire on the Mountain last year left me both unsatisfied with that game and looking for a better take on the Battle of South Mountain, which this promises to be. Who doesn’t love grueling uphill attacks in the woods?

Verdun 1916: Steel Inferno by Walter Vejdovsky (Fellowship of Simulations)A very recent addition to my collection courtesy of the Homo Ludens Secret Santa, this is a beautiful CDG about the Battle of Verdun that looks like it makes lots of interesting decisions. It’s a big ol’ game in terms of table space and CDGs are not my favorite games to play solitaire so I’ll need to persuade someone to be my opponent, but I’m really hoping I can get this to the table. Between this and Labyrinth (which I’m currently playing) 2025 might be the year I get back into CDGs.

Bulge 20 by Joseph Miranda (Bonsai Games)An upside of being in Korea is that it’s suddenly much easier for me to get my hands on otherwise difficult to track down Japanese games. This new edition of a classic game from Victory Point Games got my attention because of Nils Johansson’s amazing art, and while Bulge games don’t usually get my blood going this looks like an interesting design and I love the small package it comes in. This one will require some work as I need to print out English references for the cards, since they’re obviously in Japanese, but the game is supposed to be relatively simple so hopefully I can convince someone to play it with me.

That’s my list, what games are you looking forward to this year and what games that are on your shelf are you hoping to finally dust off and play?

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

January 22, 2025

The Korean War by Bruce Cummings

The greatest gift a work of history can give is to take a subject that you thought you knew something about and to show you that either your knowledge was far from extensive or it was fundamentally flawed. Years ago, Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston’s book on Crécy complicated the narrative of that battle to such a degree that I’m still reeling from the discovery. Bruce Cummings’ history of the Korean War has achieved a similar feat. This slim 250-page volume radically reframes the war in a way that challenged all my base assumptions about what I thought I knew and has made me think about the Korean War in a completely different way. I’m not sure that I will ever be the same. In complicating the war, Cummings’ digs up hard truths that many would prefer to forget, and which are largely absent from a bittersweet if essentially triumphalist narrative of the war that prevails in many other accounts. This book is essential reading, but at the same time I’m not sure if its impact can be felt as keenly if you haven’t already read at least one other book on the subject which makes me hesitate to recommend it as the best introductory history of the topic.

One of my favorite books I read last year was David Halberstam’s The Coldest Winter, a brilliantly written and utterly engaging history of the Korean War by a man who showed significant mastery of the art of popular military history. While Halberstam often eviscerates American decision making and particularly MacArthur and his staff, at the end of the day The Coldest Winter does not particularly question whether the American intervention in Korea was overall a good thing. The North Koreans and the Chinese are portrayed sympathetically but we are told that the Americans, while misguided and often flawed, were on the right side of history. In that way it is broadly a positive history, while Korea was no World War II it also assures its readers that it was no Vietnam. Cummings’ gives his readers no such assurances.

It often goes unspoken, but since the Korean War is still technically ongoing it complicates how we think about what happened in 1950-3. There is a tendency to look at the current state of the peninsula and use that as justification for what happened in the 1950s. South Korea is now a thriving democracy and one of the largest economies in the world, while North Korea is a paranoid totalitarian state that let large swathes of its population starve in the 1990s. This is used to justify the American intervention in 1950 – we saved a democracy and its people even if we were ultimately unable to liberate the entire peninsula from autocratic rule. This is basically Whig historiography, though, where we use the modern end point as justification for the trajectory of history. The Korean War does much to challenge this conception and argues for a very different meaning for the war.

Cummings devotes relatively little time to the narrative of the war. The back and forth along the peninsula occupies just thirty pages. Instead, what he does is force the reader to fundamentally rethink what the war was, what it meant, and what we are refusing to acknowledge. At its core the Korean War was a post-colonial civil war, and in that way, it shares far more with Vietnam than we are usually prepared to admit. Cummings shows how the government of South Korea was assembled haphazardly by the United States after 1945 and was full of Koreans who had collaborated with the brutal Imperial Japanese colonial regime in the preceding decades. Far from a free and democratic society, South Korea was in many ways an extension of the practices of colonial rule – a deeply conservative government that perpetuated violence on anyone accused of dissent or leftist thinking.

In contrast, Kim Il-Sung was a famous freedom fighter against the Japanese and North Korea represented a genuine home-grown anti-colonial movement. The Korean War was a civil war between these freedom fighters and the US-created imperialist regime in the South. In this way Korea is very much like Vietnam, where the USA intervened in support of a failing colonial regime against a movement trying to liberate their country from foreign influenced rule.

Cummings does not attach any particular moral value to this assessment, his work is meant to correct our perspective rather than to judge it. That said, later in the book it becomes very hard to feel that the USA was particularly righteous in this war. Chapter six documents the atrocities of the “air war” in the later stages of the conflict. While many people familiar with the Korean War may know of MiG Alley and the early days of jet fighter aerial combat, those accounts focus on technology porn over the actual costs of the war. The reason those plane to plane dogfights were happening is because the USA was carpet bombing North Korea into oblivion – destroying virtually every village and caring not one bit for civilian casualties. That North Korea hates America is known, but if you consider what America did to them maybe one could consider that there is some justification. America destroyed their nation and forced them to completely rebuild it. In many cases these bombing runs likely constituted war crimes – violating agreements put it in place after World War II with regard to carpet bombing civilian targets.

Chapters five and seven, structurally framing the horrors of the bombing campaign in the book, are equally unrelenting in their discussion of violence against civilians. Chapter five documents the establishment of the South Korean state in 1945 and dives deep into the mass violence committed by the new state, with tacit US approval and support, against its own people. The massacres conducted in the southwest and on Jeju Island are documented in great detail. Chapter seven continues this theme into massacres committed during the war. While North Korean violence against civilians is often brought up in histories of the war, Cummings digs deep into the crimes committed by the South Korean and UN forces and shows that of the two it was the latter that was more violent. Some of the massacres committed by the South were even blamed on North Korean forces to push a narrative of the evil communist invasion. While that does not excuse North Korean atrocities, and Cummings does not suggest it should, it is a key part of the story that is almost always overlooked in narratives of the war.

All this evidence is supported by conclusions from truth and reconciliation committees undertaken by the South Korean government around the turn of the millennium, committees that the United States did not support and in fact largely seems to have hindered (even when the forced declassification of our own reports in 1999 showed that the South Korean evidence was correct). A South Korea that is prepared to stare its own dark past in the face is laid in stark contrast with an America that refuses to acknowledge its own crimes and prefers to believe a lie of a “limited war” to prevent the spread of communism. The Korean War is often known as the “Forgotten War”, but Cummings notes that in many ways it is a war that America has refused to reckon with even when it was happening. Forgotten implies that we ever once knew what it was we did in Korea, and Cummings suggests that we never even reached that basic level of understanding of what Korea meant.

There is more to The Korean War than documenting war crimes, including a fascinating chapter that shows how it was the Korean War rather than WWII or Vietnam that led to the current status quo of the USA acting as policeman to the world with military bases flung across the globe, but I should leave at least some aspects of the book for readers to discover for themselves.

Cummings is an excellent writer, although given its content I would not call this an easy read. He does much to explain the context of Japan, China, and Korea in the lead up to and aftermath of the Korean War so no familiarity with east Asian politics is particularly necessary to read The Korean War, but he doesn’t particularly hold readers’ hands when it comes to US politics. If you don’t have some knowledge of the Truman administration and McCarthyism you might find the names thrown at you to be overwhelming. While a determined reader who is prepared to look up individuals they don’t recognize can tackle The Korean War as their first history of the subject, I think it may be best appreciated as a companion to another work on the subject – a counterpoint of sorts. Given that Cummings offers his own critiques of The Coldest Winter in the book (while at the same time praising Halberstam and having his own positive opinions of the work), I think that presents the ideal companion.

Overall, I can’t recommend The Korean War enough. It has fundamentally changed my perspective of the war but beyond that it has made me rethink how I feel about America’s place in the world. At the end of the book Cummings argues that in time the Korean War will be seen as one of the most important conflicts of the twentieth century, far from forgotten it will be fundamental to our understanding of how the Cold War and post Cold War world order came to be. After reading his book, I think he may be right.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

January 19, 2025

2024 in Review – Top 8 Books

I like to set myself a goal for the number of books I will read in a given year. In previous years this was fifty books, but I found that this constrained my choices as I often passed over big doorstopper volumes because they take too long to read which could imperil my chance of reaching my target. In 2023 I dropped my goal to forty books and barely hit that target, and 2024 proved to be an exact repeat – sliding in to the finish in the last weeks of December. For 2025 I may drop down to thirty-five to allow even more room for the kind of dense books I enjoy. However, I am also hoping to read more fiction, which generally goes much faster than the kinds of history I usually read. I’ve recently been getting more review copies of academic books which has been great (academic books are expensive!) but it also means I’m reading more dense history books and I need to put some more lighter fair in there as well.

On the whole, I wouldn’t classify 2024 as a particularly great year in terms of what I read. I read some excellent books, eight* of which I’ve chosen to highlight below, but I also read a lot of books that were just fine. I don’t think I read anything that I absolutely hated, though, so that’s a win.

Non-FictionI read a real mix of books in 2024. I continue to dabble in American Civil War history for the We Intend to Move on Your Works project, but fewer than in previous years. If any theme was dominant this year it was the range of new books on the history and culture of tabletop games, particularly historical wargames and roleplaying games, that I read last year. I also read quite a few books on the Hundred Years War and the Wars of the Roses as I wrapped up my own book on the Battle of Castillon.

Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground by Stu HorvathProbably my single favorite book I read this year, and almost certainly my favorite review I wrote, this is a fascinating trip through the history of tabletop RPGs delivered by a passionate author. I could heap more praise on it, but please just read the review because I’d just be repeating myself in a worse format. I also have to give honorable mentions to the second edition of Playing at the World and the edited volume Fifty Years of D&D, both of which I adored but of the books on tabletop games I read this year it was Monsters that I enjoyed the most.

Chancellorsville by Stephen SearsAs a central Virginia of a Union-sympathetic persuasion I have a long and complex relationship with the Battle of Chancellorsville. For years I maintained an obstinate ignorance of it in rejection of the often-masturbatory glee that Neo-Confederates dump on “Lee’s greatest victory”. However, when visiting my parents over the summer I decided to grab my dad’s copy of Stephen Sears’ book down from the shelf (having previously enjoyed his book on Gettysburg) and I’m so glad I did, it gave me a newfound respect for the history of the battle and did much to complicate its status as an example of Lee’s genius overshadowing an incompetent Hooker.

A Short History of the Wars of the Roses by David GrummittI’m on the record as not being the biggest fan of the Wars of the Roses. A large part of this has been that histories written by posh English historians of years past assume a baseline familiarity with the personalities and details of the conflict and as a result the narratives are hard to follow and tedious to read. I previously enjoyed David Grummitt’s biography of Henry VI and so I decided to try his history of the Wars of the Roses and was delighted to find an approachable and engaging history that assumes no previous knowledge of who Earl such and such or Duke so and so was – just a delight to read.

The Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge by Joe StaritaThis is a book that was recommended to me many times on a subject I know nothing about and this year I finally got around to reading it. A history of the Lakota people from the mid-19th century through the 1980s told through one single family across three generations, this shows the complexities of American expansion westward and the challenges of being a native under an American imperialist state in an intimate and utterly engaging way. Highly recommended.

FictionI didn’t read as much fiction as I would have liked (which is becoming something of a theme, sadly). This year I revisited some favorite authors and took advantage of a trip back to Charlottesville to browse its excellent secondhand bookshops and pick up some classic paperbacks. As a fan of classic sci fi and fantasy, secondhand bookshops are treasure troves of books to tempt me.

Neutron Star by Larry NivenThe first of my classic paperback haul, I’d never read any Niven before and I was delighted with the experience. Set in his Known Universe, the stories were that flavor of hard sci fi that I find engaging without being tedious. While his protagonists tend to be stiff and largely indistinguishable from each other (a common problem for authors of the era) the setting and plots were enjoyable and different from what I’ve read before. I don’t know how much deeper into Niven’s canon I will go, but I expect to pick up at least one more in the future.

The High Window by Raymond ChandlerNot a lot to say here – I’m a huge fan of Raymond Chandler and I’m slowly reading through his catalogue, taking my time because I know there won’t be any new ones. This year I actually read quite a few modern hardboiled detective stories and while I enjoyed most of them none were as good as Chandler.

A Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality by John le CarreI like le Carre, but I have also found his books to be so bleak that I struggle to read them – too much of a downer for me. I decided to try and tackle the Smiley series, hoping that since Smiley continues to live throughout that they can at least only be so depressing. The first two are honestly more like detective fiction than the later espionage novels that le Carre became famous for. A Call for the Dead is probably the better mystery (and has elements of espionage in it) but I adored how much A Murder of Quality is a hate letter to Eton and posh English boarding schools – you love to see it.

The Face of Chaos ed. Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn AbbeyThis is an odd one, because at times I didn’t really enjoy this book and I’m not sure I would recommend it but I also cannot stop thinking about it. This is the fifth volume in the Thieves World series, a collective fantasy universe that multiple authors contributed to the development of which I learned about from Stu Horvath’s Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground. I snagged a few of these in a secondhand shop, but sadly this was the earliest volume I could find. Jumping in mid-series wasn’t the best experience, and some of the stories are a bit gross in a way that fantasy of this era was, but I remain fascinated by this idea of a shared world that multiple authors helped to advance the shared narrative of. I will absolutely return to Thieves World and I can’t help but wonder what a modern take on this style of publication would look like.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)

January 15, 2025

Wargames According to Mark by Mark Herman

It looks like we are entering something of a golden age when it comes to serious discussions of tabletop games – at least in book form. I’ve had the pleasure of reading a respectable pile of new books on the subject over the past year, including several on historical wargaming. Last year saw the publication of Maurice Suckling’s textbook Paper Time Machines and Riccardo Masini’s philosophical treatise Historical Simulation and Wargames, and, last but not least, renowned designer Mark Herman’s personal memoir/philosophy/reflections on his own design process for historical games.

Published by GMT Games, better known for publishing Herman’s games than for publishing books, this is a hefty volume full of color pictures that draws inspiration from Herman’s frequent contributions to C3i Magazine. In addition to the two hundred odd pages written for the book, Wargames According to Mark includes sixty pages of design notes originally printed in many of Herman’s card driven games (CDGs). The book is subtitled An Historian’s View of Wargame Design (more on that later), highlighting up front that this is explicitly one person’s view of game design. This is not like Paper Time Machines, which hopes to provide a general view for individuals interested in analyzing and possibly designing games, but rather Herman’s own thoughts on how he has designed his own games. While some readers may find insight for their own design work, this is not a how-to guide. Rather, it is more closely aligned to the design notes that are usually included in Herman’s games.

I am of the firm opinion that the kindest thing one can do with someone’s creative output is to take it seriously – and to treat it with respect requires unfiltered honesty. This means giving praise, of course, but also offering commentary and critique where necessary. I enjoyed reading Wargames According to Mark and I would recommend it to anyone who is already interested based on the title and author alone – you won’t be disappointed. It covers a lot of ground and in it I found sections that made me consider viewpoints I never had before while also finding others that made me scratch my head and consider my own conflicting beliefs. I love books that encourage me to engage with them and offer my own critiques, and Wargames According to Mark achieves this with aplomb, kudos to the author.

Mark on HermanWargames According to Mark sits at a crossroads of different book potentialities, a position that I find easier to define by what the book isn’t rather than what it is. It is not a guide to design, that much Herman makes clear from the start. It is also not a history of Herman’s own design career; it dips into aspects of his designs but readers looking for a comprehensive account of the past forty or so years of Herman’s design work may be disappointed. The book is primarily a snapshot of Herman in the here and now with an emphasis on certain threads of his design career.

The book opens with an account of how Herman got into wargame design, including his early career with SPI and how he learned design at the feet of Jim Dunnigan. Fans of SPI and anyone with an interest in how they did design, including some detailed descriptions of pre-computer wargame design, will really enjoy this section. It explains Herman’s design origins and he even walks through the design of one of his games from that era to show the basics of his process. While the theme of him learning his craft at SPI reverberates throughout the book, beyond this section there isn’t a lot of detailed discussion of the actual games he made at this time – fans of Stonewall will not find a detailed breakdown of how that game came to be, for example.

Much of the book focuses on Herman’s favorite designs, which lean towards his more recent work and games on the strategic scale. We the People/Washington’s War, For the People, and especially Empire of the Sun loom large throughout the book, as do Churchill, Pericles, and the relatively recent new edition of Pacific War (technically the oldest game to receive substantial attention in the book). That’s not to say that these are the only games that Herman writes about, many other designs get a look in here or there, but in general if you’re a diehard fan of Great Battles of History or any of Herman’s tactical games (excepting Rebel Fury and its ancestors) you may be disappointed. On the other hand, if you’re an Empire of the Sun mega fan you will be delighted with Wargames According to Mark.

I don’t share Herman’s enthusiasm for strategic games (more of an operational man, myself) and I haven’t played many of the games he discusses in depth in the book, so I couldn’t help but feel that I wasn’t getting the most out of these sections. Discussions of the underpinnings of aspects of Empire of the Sun’s design are harder to appreciate if I’ve never played it and I don’t know much about the Pacific War (although, to be fair, Herman does usually provide some historical context before going on a lengthy piece about design) so it was hard for me to relate the history to the design choices. This is not a criticism, the book is what its author wants it to be, nor did it prevent me from enjoying reading it, but it is to describe how I may not have been the target audience.