Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 11

June 19, 2023

Arquebus: Fornovo 1495 by Richard Berg

It’s been a while since I played Men of Iron and I’d been been hankering to try some more Arquebus so I took a break from playing a small mountain of American Civil War hex and counter games for a brief holiday in sixteenth-century Italy. I decided to try the Fornovo scenario for the very boring reason that it was the first battle in the play book and I’m glad I did because this is probably one of the most interesting Men of Iron scenarios I have ever played. It reminded me of everything I really like about Men of Iron, as well as some of the elements of the system that I don’t think work so well. Those wrinkles weren’t enough to stop me from enjoying Fornovo a lot and putting it high on my list of scenarios I want to try again.

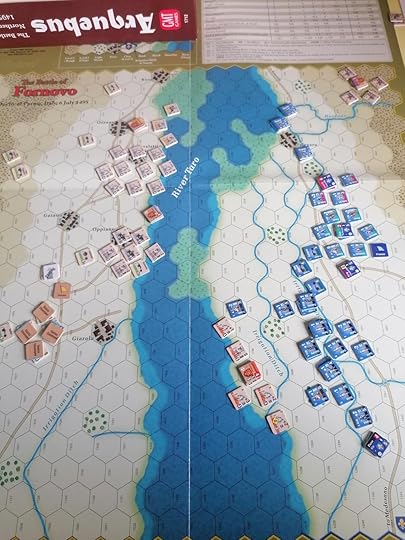

The initial set up for Fornovo - Venetian alliance on the left and French on the right. If the French can march their army off the bottom of the map they can automatically win the game.

My early impressions of Arquebus were really positive back when I played Cerignola many months ago and my second experience is equally positive. I can see the further development of the core system present in Arquebus from the original Men of Iron system. The new element that I interacted with the most this game was the Engaged combat result. This result on the CRT can lock your units into melee, forcing them to make attacks whether you want to or not and increasing the cost of withdrawing from combat. I really enjoyed putting down the Engaged markers to show sustained fighting, it gave the game a nice sense of narrative.

I liked Engaged as a mechanism, even if I felt it was perhaps a little too forgiving. Maybe this is my desire for narrative over strategy, but I would kind of prefer it if it was impossible to willingly withdraw from an Engaged marker – essentially you are now locked down and must fight until someone is eliminated or is forced to retreat. Since I was playing solitaire anyway I pretty much treated Engaged as working this way – who was going to stop me? It was nice to have more potential outcomes on the CRT, although I did find myself missing Blood and Roses result that lets the defender choose Disorder or Retreat. I don’t think Engaged, or Arquebus’ CRT in general, was a radical shift in my experience of the system, but I like the CRT in Arquebus more than I like the one in Men of Iron and Engaged results are a part of that.

The Venetians make their initial crossing, but can this lone Battle halt the departure of the French army and survive to be reinforced? Meanwhile, up top the French have moved their supply wagons to try and deny the Venetians the chance to loot them.

What I really loved about Fornovo, though, was the map. I have joked more than a few times with friends about the lack of terrain in medieval (and ancient) wargames. Quite a few scenarios in the Tri-Pack have lovely terrain scattered around the edges of the map and, conveniently, little to nothing the main play area. That’s a bummer, terrain was just as much a feature of pre-modern warfare as it has been of the modern era, and I want to see it in games more. They didn’t have large empty fields set aside for both sides to agree to fight in – the factors of terrain could be crucial to a battle’s outcome. Fornovo has a large river running straight down the middle of the map and as you play the river will rise, making it increasingly harder to manage. The Venetians have to cross the river and attack the French and as the Venetians you will be spending a lot of the game wading through river and swamp and making rolls to see if your troops are disordered as they climb up the steep banks on the far side.

The river is not particularly complex rules wise – it is governed by just a handful of extra special case rules that are easy to remember and intuitive – but it immediately defines Fornovo as a different game from what I had played before, in a good way. It really showed how having even a simple piece of terrain that the players have to interact with can really change the shape of the experience and open up many What If options for how to play differently. I really like Men of Iron but there are more than few scenarios where I’m not very interested in replaying them because the approach between the two armies will probably be almost identical in every game. Movement is the aspect of hex and counter gaming that I love most, and I want more elements that force me to make interesting decisions during my movement. The river in Fornovo is a great example of this, and while I know to an extent designers are limited by historical events I would love to see more efforts to create scenarios for this system that find ways to include interesting decisions in how the two armies approach each other.

The water level in the river rose significantly, causing significant delays to the arrival of Venetian reinforcements as foot units struggled to wade across. Meanwhile the first Battle to cross is holding on but things aren’t looking good for them.

Fornovo’s victory conditions also interact with the river in interesting ways. It uses the standard flight points system common to other scenarios, but also if the French player can move sixty flight points worth of their units off the bottom edge of the map, they will automatically win the game. Interestingly, this is if they can move sixty points or more. Moving fifty flight points gets you nothing. This creates a great decision space, because you want to move your army slowly towards the point where you can flee the map, but you don’t really want to start pulling units off the map until you are confident you can move enough to win. If you move too many units early, then you may find yourself lacking troops you may need to fight the Venetians. This also puts an immediate pressure on the Venetian player to get across the river to prevent the French player from using Army Activations to march their entire army to the edge of the map. This can push the Venetians into making some reckless moves to rush across the river. In my game some overly aggressive Venetian play resulted in several eliminated units, which eventually cost the Venetians the game without the French marching hardly any units off the map. By having multiple paths of victory to consider, and in particular having a time pressure on a scenario with large amounts of terrain to slow players down, really makes Fornovo one of the best Men of Iron scenarios I’ve played.

The Venetians have crossed in force, but they have many routed units and the first Battle to cross has been eliminated. The French must now decide if they march most of their army away to try and secure an automatic victory, or turn and confront the remaining Venetians to win on flight points.

Arquebus, or Fornovo at least, may address my periodic whinging about terrain in Men of Iron but it doesn’t fix some of my problems with Men of Iron as a system. My main problem is probably still Continuation – a system that I think comes close to working but isn’t all there. Thought has clearly been put into the Continuation values for the various leaders in Fornovo, including the inclusion of several leaderless Battles that can only be activated with a Free Activation, which is great to see. I really like the tension in the decision of who to pick for an attempted Continuation roll. However, I think Continuation is a little too unreliable to really work. I’ve had games where my opponent and I played for at least a dozen activations without a single Continuation – at which point it didn’t even feel like Continuation existed. I would really like to see a system for Continuation that makes a second activation much more likely and then drops off more precipitously after that – possibly even including a punishment for going for too many continuations rather than passing. Continuation is great when it works, I just don’t think it works often enough. I’ve even begun brainstorming some modifications to it which I will (hopefully) try and test later this year.

The final game state - France went for a bit of both. Several units have left the map, but the main force has turned and removed just enough Venetians to put their army to flight. A solid French victory.

I’ve thought about whether I want to keep my full set of Men of Iron long term or if I would be happy reducing my collection down to just one box at some stage – once I’ve played every scenario at least once of course. Fornovo makes a strong argument for Arquebus being the lone box I’d keep and pushes it towards being possibly my favourite entry in the series. There’s just a lot to like about Arquebus and Fornovo specifically. I had a ton of fun with this battle, and I need to get Arquebus more often. My complaints about Continuation aside, Men of Iron is a system that knows not to let complicated mechanisms get in the way of the fun and delivers a consistently enjoyable gaming experience – especially solitaire. I was already a big fan of Men of Iron and Arquebus has really reinvigorated my enthusiasm for the series.

June 16, 2023

First Impressions - Tetrarchia by Miguel Marqués

I was lucky enough to be invited to guest on a teach and play of Tetrarchia Second Edition, published by Draco Ideas. I’ve been interested in trying this game after I was very impressed with Draco Ideas’ game 1212 Las Novas de Tolosa, and I was excited to give it a shot. You can see our full replay as well as an extended discussion on a variety of topics in the video below:

June 12, 2023

Review - Andean Abyss by Volko Runke

It happened! COIN came to the internet’s best online wargame platform, Rally the Troops, in the form of the series originator Andean Abyss. In many ways this is the obvious choice for Rally the Troops, it’s both a great place for those interested in learning the system and out of print with little promise of a reprint soon, so not in direct competition with sales. It also offered me the first time to try and dive deep into a COIN game and see how I feel about the system after repeated plays. The requirement to get four players and dedicate most of a day has made consistent plays of COIN games a challenge. I have dabbled with solitaire play, and enjoyed that, but I’m terrible at flow-charts and multi-hand solitaire is a very different kind of experience. So, I’ve been logging many, but not an insane number, of Andean Abyss plays over the past month or so, what have I learned?

The Game

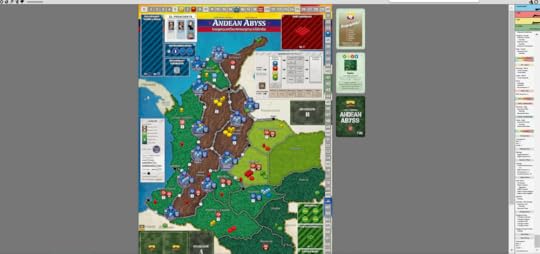

While not my favorite game in terms of aesthetics, I still really enjoy looking at Andean Abyss and it can be very striking in its own way.

I haven’t played all that many COIN games but even I can tell when playing Andean Abyss that this is the originator of the system. It feels like the Ur-COIN, the foundation that the rest have built themselves on top of. Each faction feels the most like itself. I don’t know a better way to put it than that. This is the COIN system at its most pure, and that makes it perhaps the most interesting to me as a game to play many times over and over again. It doesn’t bring a new twist on the formula or some little tweak that maybe I could develop a jaded familiarity with. What Andean Abyss brings is the whole package – the COIN system itself. Four different factions, three of which play similarly but all of which have very different paths to victory. Games can have a shared rhythm to them, but each one will play out differently. It’s not hard to see why there are more than a dozen of these games with no end in sight, the core system is strong.

For me the most interesting element of COIN is probably the action selection system. The first player’s ability to dictate what options are available to the second player, cutting off some options by restricting their own choices, is genuinely fascinating and I’m not sure I’ll ever get bored of it. I also enjoy the fact that only two players act each round, so by taking an action now you know that you won’t be acting for at least one more turn. This system is not without its hiccups. The fact that initiative is dictated by cards can create a sequence of turns where you just are never first player and thus don’t get to act very often at all. I think this can be particularly pronounced if the Events on the cards are themselves not very good – if the first player takes the Event you can still have a great turn, or alternatively if they let you take the event that can be great. I have found in other COIN games I’ve played that it is possible to be locked into several turns of Limited Operations (actions that affect only one of the board’s many spaces), which is a bummer, but in my recent run of Andean Abyss plays I haven’t found it to be as much of a problem. This could be blind luck or reflect the fact that I’ve been playing with more newer players who seem more likely to take either the Event or make big plays, leaving more options open to the second player, but it is also possible it reflects good card design and until I have better evidence I will give the credit to Volko – to potentially be rescinded if I ever learn otherwise! Even after many plays the deck doesn’t feel boring – I’ve seen every card it has to offer but I still enjoy playing it which is testament to a strong system that uses its cards well but is not totally reliant upon them to deliver the gaming experience.

The interplay of the factions is the thing that I think most people notice in COIN and that is not without good reason. While hardly fundamental to the experience, see for example The British Way designer Stephen Ranganzas’ talk on modelling COIN, the 2+ player experience is still relatively rare in wargaming, and it is often a joy to experience. While it takes some getting used to, I enjoy COIN’s reliance on the players to keep each other in check. I also enjoy that it generally discourages punishing whoever is in last place, as you never know when you might need them to cripple the leading player and, besides that, while they are down and out, they are generally not much of a threat. Coin also allows a certain amount of resource exchange which can be useful for making deals between players, perhaps bolstering someone who is falling behind to help them attack the leading player. I haven’t experienced much of it in my playing of Andean Abyss, but perhaps as I become more familiar the possibility of swapping resources in exchange for support or certain actions will become more common. It certainly featured in my one game of A Distant Plain and was an interesting element of the system there, and there’s no reason not to do it in Andean Abyss.

It's hard to know what else to say about a now genre defining game from over a decade ago. Andean Abyss remains a truly impressive piece of design and thanks to Rally the Troops it has literally never been easier to play it. It contains staggering nuances that are better experienced than told of but also does not rely on surprise to keep itself exciting, making it potentially eternally replayable.

The Platform

It is actually very challenging to get the entire map from Rally the Troops to display in a single image - usually you just look at one section but it does have functionality to show you a wider picture. Hopefully this gives some indication of how clean the presentation on the website is - but I promise the blurriness is all my fault!

Rally the Troops is an amazing website, and I will say nothing ill of Tor’s implementations of the games on it. They’re the best I’ve ever encountered, and I wouldn’t trade them for anything. That disclaimer out of the way, I want to say that my experiences playing Andean Abyss on Rally the Troops have been mixed at times. The reason for this comes down to the two different ways to engage with Rally the Troops: as a platform to play with friends or as one to play pick-up games with strangers. Playing Rally the Troops with friends is great. 10/10, no notes, would (and will) do again. Playing random pick-up games, however, I have found to be more of a mixed bag.

I did not exactly discover this while playing Andean Abyss. In my deep dive into the Columbia Block games on the site I had a better time playing with my friends than with strangers, but in those cases it was more a matter of my being utterly crushed at a game I was trying to learn rather than a strictly negative experience. The internet strangers who handed my ass to me at Crusader Rex or Julius Caesar were very friendly about it and I hold no ill will against them, but it was also a rough way to learn those games and I preferred playing with people more on my level. That said, I’ve had many fun games against strangers, especially with Shores of Tripoli whose quick play time keeps my crushing defeats short! However, Andean Abyss hasn’t been like this. Not only has it not been a case of crushing defeats, in fact the early balance of the game feels way off as people are only just learning it. Rather, it is that a core element is missing from the experience: the other players.

COIN games are generally four player experiences and often rely on players at the table balancing the game against each other. The factions may not all be created equal, and the game is reliant on the players knowing this and jointly acting to execute whoever the leader is while other players craft schemes over how to exploit the upcoming power vacuum. This is much harder to do when everyone is playing asynchronously on their phones rather than around a shared table. Rally the Troops does include a chat function, but it’s no substitute to the free-flowing discussions that can make a COIN game exciting. In games like this I really enjoy doing my best to persuade the other players around the table that I’m no real threat, and shouldn’t we all be really worried about that player over there? This is much harder to do in asynchronous play with strangers I barely talk to. The burden of communication is higher, and they have far more time to study the board state and ignore what I am saying.

I would like to stress that this is not a flaw with Rally the Troops – you could easily play on the platform while in a Discord chat group or voice channel and effectively replicate the experience of a shared table. Instead, it is a problem with how I often play games on Rally the Troops – taking turns on my phone when they crop up and not really thinking about the game outside of that. If I’m playing games with friends, I chat to anyway then the opportunity to discuss the game comes up naturally and fills some of this gap, but when playing with strangers it creates a more isolating game experience. This isn’t to say that it is necessarily a bad way to play. As I said, I’ve had lots of great games on Rally the Troops and I wouldn’t change anything about the platform. This is just something that I’ve noticed more when playing Andean Abyss. While I really appreciate how Rally the Troops has given me the opportunity to play Andean Abyss many more times than I would have otherwise, it is also not a substitute for the shared experience of playing a game like this in person and I intend to keep playing COIN games that was as much as I can. However, I will also be playing more Andean Abyss on Rally the Troops – although I will probably mostly play with my friends for the time being.

Repeated PlaysI really like Andean Abyss and I’m so glad I’ve been able to explore it as much as I have thanks to Rally the Troops. I owned a physical copy of the game, but only managed to get it to the table with friends once. Rally the Troops enabled me to experience so much more of its depth. That having been said, as I play COIN more, I find that I’m not as drawn to repeated plays as I would have thought. A game series filled with multiple asymmetric factions in each box practically cries out for players to try them all and discover the depth in each one. However, I have found that because COIN really requires a deep familiarity with every faction at the table, especially after the first couple of learning games, each game feels a bit like you are playing all the factions – you are just only in direct control of one of them. You try and push your opponents into certain plays and direct them towards taking actions that benefit you (or at least hurt you less) while bolstering your own position. This is a great dynamic, but it also means that I feel like I’ve played each of the factions in Andean Abyss more times than I technically have. Playing the AUC, I spend so much time thinking about the potential FARC actions that after a game I feel like I’ve intimately experienced both factions, even if I was only in control o fone.

Unlike a game like, say, Here I Stand where I feel like I’ve barely learned my faction after a game let alone the others, I feel a much greater familiarity with the COIN factions. Some of this may be the lack of separate board positions – players in COIN games generally use the whole board, maybe not equally but certainly to some extent, so there isn’t that obvious difference in how we experience the shared gaming experience. This isn’t really a criticism of the COIN series, but rather is an indicator of the fact that I after a few games of any given COIN title I’m usually more interested in trying a different one than I am in logging a half a dozen or more plays in that first game. I like the thrill of the new history, the new tweaks to the system, the new map, and then after a few plays I feel like I’m ready for the next one.

That having been said, as Andean Abyss is the most foundational COIN of them all, I still had a lot of fun playing it repeatedly and I will continue to play it thanks to the convenience of Rally the Troops. I’m just not sure I would be playing it more if I couldn’t play it on my phone – or at the very least I’m not sure I would be seeking it out. It’s not like these are light card games I can throw in my backpack and play in the pub. Playing a full-length COIN game takes many hours and perhaps some light coercion among my friend group. Coordinating that is a lot of work, and in that environment, I think I’d prefer to try something new than keep digging into the one we have already played.

That does lead into my one small issue with Andean Abyss, especially in person: it’s really quite long. It manages to stay enjoyable throughout the experience, but this is a long game where you will spend most of it taking only four actions – or fewer. As the Cartels I do a lot more Rallying than I do Attacking. This isn’t a terrible thing – the games would probably be much worse if you were given a menu of half a dozen or more actions. Four makes it manageable and keeps it feasible for you to learn all the factions’ core capabilities in one game. However, it is also an experience that I think I would generally prefer to last 90-150 minutes rather than four hours. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes all-day COIN is great and I like the ability to have these big games unfold over the course of an afternoon or even a full day, but I don’t want it to be the primary way I experience it. I know Andean Abyss comes with a short scenario, but it feels a bit truncated as an experience, I think. Rally the Troops, by removing the requirement to play all at once, reduces this burden but it is something that would discourage me from playing Andean Abyss again in person. It’s also a reason I’m excited for titles like The British Way or People Power which are offering ways to engage with COIN but with a much shorter time investment.

ConclusionAndean Abyss is a good game and Rally the Troops is a great platform. It’s basically the chocolate and peanut butter of wargames – except, that’s definitely Nevsky, so maybe it’s more like the bacon and eggs of wargaming: two great breakfast foods that pair together wonderfully. This metaphor is a mess. Look, stop reading and go play Andean Abyss – it’s free on Rally the Troops and you can even play multi-hand solitaire if jumping straight into a game with other people is too intimidating. While you do that I’ve got some other COIN games I need to try..

June 2, 2023

Review - Here I Stand by Ed Beach

I first played Here I Stand five years ago at a time when I was far less familiar with wargames. In fact I had recently purged my small game collection of every wargame I owned but Here I Stand because I had given up on finding time and people to play them with. Despite this, in 2018 I made the effort of gathering six of my friends and spending the entire day playing Here I Stand. It was amazing. It took us over eight hours. In the end I emerged victorious as the French, securing an instant victory moments before the Ottomans won on VPs earned mostly through piracy. I spent the next 24 hours buzzing with excitement and exhaustion after that phenomenal day of gaming. I had to get it back to the table, I needed that experience again. Finally, a child, a pandemic, and five years later I managed to play it again and let me tell you, it was just as good the second time!

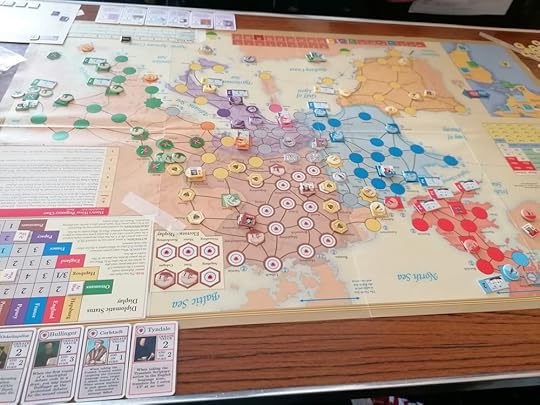

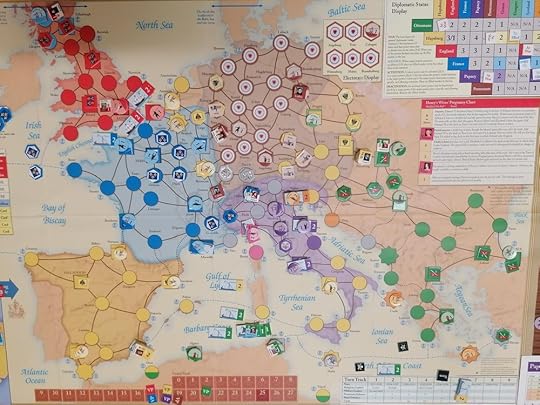

Travel back in time to the distant past of 2018 and my very first game. Just looking at it gets me excited all over again.

I finally managed to play Here I Stand again thanks to Chimera Con - a single day board game convention in Dublin dedicated to long multiplayer games. Unsurprisingly, Here I Stand is a perennial favourite and this year there were two tables of it running at the con. Instead of playing the full scenario which starts in 1517 and lasts for hours and hours, we were playing the tournament scenario which begins in 1532 and lasts for three game turns; turns four through six of the main scenario. I also wanted to change up my experience by playing one of the religious factions, since France had been pretty much pure military, and so I was assigned the Protestants. We played for the much more manageable time of just under five hours - still a long game, but short enough that many of us managed to play other games in the afternoon. Once again, after finishing the game I was buzzing with excitement and exhaustion for at least 24 hours. I may have only played two games of Here I Stand, but I’ve spent thirteen hours of my life playing those games and many more obsessing over it. I cannot imagine that my opinions will change substantially no matter how many more times I play it, and I have some thoughts I need to put down on (digital) paper.

My glorious victory! Henry VIII successfully took Edinburgh but not without losing Calais and most of England. The square locations are Key locations which are worth victory points and if any one (non-Protestant) player can place all their Keys on the map they immediately win the game.

Some Necessary BackgroundHere I Stand is a six-player card driven wargame about European conflict between the years 1517 and 1555. Each player controls one of six major powers: England, France, the Hapsburgs, the Ottoman Empire, the Papacy, or the Protestant Reformation. As befits a game with this many players covering such a wide topic, Here I stand is a game of substantial complexity. However, that complexity can be a little misleading. While the game as a whole is full of many different systems for modelling a range of potential actions, no player will interact with every one of these in a single game. The only person who really needs to know how every aspect of Here I Stand works is whoever has the onerous job of teaching the game to the rest of the table.

As an example, I was the Protestants in my most recent game. As the Protestants I had no access to ships, and thus I never needed to know how the several pages of naval rules worked. In contrast, my neighbour (both geographically in the game and at the table we were playing on), the Ottomans, needed to know the naval rules intimately but had no need to learn the rules for religious conflict, which made up most of my actions. Now, it is strategically beneficial to understand how each faction works so you can keep track of how they might be scoring points over the course of the game, but it is not necessary and that is a key distinction. You can play Here I Stand by only know about two-thirds of the rules, and that’s not nothing!

This asymmetry helps to keep the game manageable and is core to how it crafts an interesting experience. On their turn each player plays one card from their hand, either for the event or, more usually, for action points they can use during their turn. Each faction has a menu of actions they can spend points on but what options are available to an individual faction and, occasionally, the cost of those actions varies. This isn’t really where the game’s asymmetry comes in, though. These actions are the tools you use to play the game, but in most cases the game has just limited your actions to only those most relevant to your goals. To reuse a previous example, as the Protestant player I couldn’t build ships, but I also had no real motivation to want to do so, so removing this option was no great hindrance to me. How you win the game is where things get interesting.

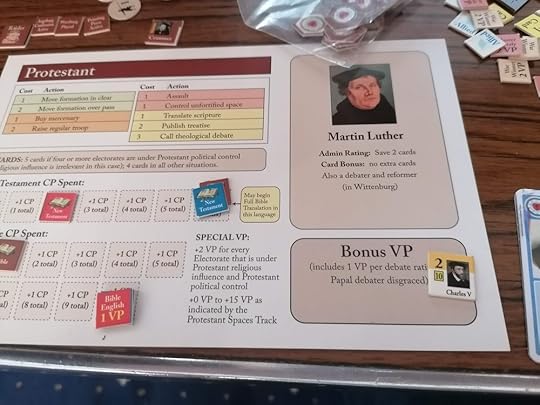

I do seem to be routinely end up viewing the board upside down when playing Here I Stand. Maybe some day I will sit on the other side of the table. This is the initial set up of the 1532 scenario. Also notice the custom debater cards that the person running the game provided - much easier to read than the tiny counters that come with the game.

The boring answer is that you generally win by getting victory points. However, how you get victory points can vary substantially between factions. All factions have some way to get VPs through controlling points on the board, but while most factions share a goal of fighting over key cities this is not universal. Beyond that, each faction generally has a way to earn their own VPs either through religious influence, building chateaus and cathedrals, having children, or piracy. Probably the most interesting element to Here I Stand’s victory conditions is how VP accumulation feels at the same time very slow and, occasionally, terrifyingly fast. This is a game where each VP can feel like a hard fought achievement but then at the same time in turn of my most recent game (a turn being approximately 5-7 card plays for each faction) the English player picked up like eight victory points, going from last to tied for first.

I could espouse at length about how this happens via the chaotic nature of conquest in Here I Stand and the occasional opportunities to seize a fistful of VPs that may come along only once per game, simultaneously lurching you ahead and putting a target on you, but I think describing the nitty gritty would be a disservice. What matters more is the excitement of it! Laying careful plans to slowly pull yourself ahead a few VPs at a time is great, particularly as you know that with the slow shifts in VP that the game allows it can be very hard to claw a leading player back down once you start pushing ahead. At the same time, if you are sitting near the back of the pack watching someone creep ahead you could potentially feel dispirited because you’re stuck behind, but all is not lost! Everyone’s focus being on the leading player could give you an opportunity to jump ahead by attacking a vulnerable point that someone forgot about! Here I Stand is not like the ever-popular multiplayer wargame COIN series in this regard. In my experience, a COIN game generally features players jockeying for the lead and then, as soon as someone gets too far ahead, everyone turning on them and pummeling them into submission. The goal in COIN is usually to be within striking distance of winning, but not actually winning, so that you can jump across that finish line at just the right moment.

Here I Stand absolutely has an element of players trying to keep an eye on who is in the lead and finding ways to pull them back, but it gives players nowhere near as many tools to do that with. For one thing, you can’t just attack players whenever you want – you have to have declared war on them at the start of that turn or have one of the very few cards in the game that let you declare war during a turn. If one player is creeping ahead it often falls to one or two of the other players to keep them in check, leaving the other three to plot how best to use this opportunity to secure their own fortunes. This means that more often than one player being dragged down a huge number of VPs, efforts will be put in place to curtail their advancement only for a new threat to emerge suddenly and distract the table anew. This dynamic is made possible thanks to the number of players and the limitations imposed, both mechanically and geographically, on each of those players. In both of my games one player managed to reach their victory threshold, and thus drew the ire of the table, only for a new threat to emerge in the final turn – in one case the new threat came out victorious while in the other it came up just short but both times it created a thrilling final act for the game!

Take for example my recent game. I was pulling ahead as the Protestant player and that meant that the Papacy and the Hapsburg player had to try and curtail my advancement. The papacy could try to reduce the reach of my religious conversions while the Hapsburgs could take electorates from me, netting them VPs and denying me ones. However, in doing this all attention turned away from England who chose then to launch a major invasion of France (who had left several cities largely undefended to pursue conquests in Italy), which saw them acquire VPs in spades while no one could stop them because they were only at war with France who was stuck in Italy!

My personal player mat. I also managed to gloriously capture Charles V in battle in the opening turn of the game. Both of my games have opened with victories over the Emperor in an early pitched battle - battles can be very swingy!

Tragically my opponent had a Ransom event and got Charles back without having to pay me anything during the diplomacy phase

A Note on Game SizeHere I Stand has a deserved reputation of being a game of enormous scale. This is both deserved and undeserved and I hope to explain why. Firstly, yes, Here I Stand requires six players. Do not be deceived by the box claiming it can be played at between two and six. This is a game destined to be a six-player experience and that is how I would recommend playing it.

As to its length, however, I have some thoughts. The full scenario is a day long experience, have no doubt about that. It lasts nine turns, and each turn will take you at least an hour to resolve, possibly quite a bit more. Even though there is a decent chance that your game won’t last all the way until turn nine, usually someone wins before then, it will still take many hours. It also won’t stop you from needing to put aside a full day to play the game, because even if you finish on turn seven you need to allow for the possibility of the full nine.

The early actions when everyone is still feeling out everyone else’s position. Our game began with most factions being at peace and trying to bolster their own positions before things heated up in the later turns.

However, let me point you in the direction of the tournament scenario as an interesting alternative. In the tournament scenario you start the game in 1532, on turn four, and you play for three turns of the game. For my most recent game using this scenario we played for about five hours to resolve these three crucial turns during what would be the main scenario’s mid-game. I had worried that it would feel like a truncated experience, but honestly, I felt like it gave me most of what I love about Here I Stand in a much more manageable amount of time. I was really impressed, and I would recommend that people give it a shot – whether you are someone who wants to try this game but is struggling to find the time or if you’re a veteran who is always looking to play it more. It makes very few changes to the core game – players start with a few more cards on the first turn and on the final turn a key event is placed in the English player’s starting hand rather than shuffled into the deck – and gives you so much of that Here I Stand goodness in a half day experience.

That said, I won’t stop wanting to play the full scenario just because the tournament one is so good. There are a few elements that are missing from the tournament scenario and that will mean that I want to play both. In the early game, I missed the more antagonistic relationship between France and the Papacy of the 1517 start that isn’t present in 1532 – namely that the two are at war and France has invaded Italy. The tournament scenario also gives very few opportunities for dynastic change among the players which is an element of the game I really like. You will definitely see a new pope – in our game it happened immediately – and could potentially see a new English monarch or Protestant leader but neither is very likely. These rules don’t necessarily create a radical shift in the game, but if you’re into Here I Stand for the historical narrative (and why else would you be playing it?) then you will be missing out on some of that grand scope the game provides by including dynastic change among its mechanics.

The end of Turn 4, or the first turn of the tournament scenario. The VPs were still pretty tight but Ottoman piracy was proving an early threat.

What Doesn’t Quite WorkOkay, so I adore this game to the point of obsession, but I am not going to sit here and tell you that it is flawless. This has not stopped me from loving the game, but I must confess that the religious conflict mechanics are a little bit…eh. For context, there are two main ways that the Catholic and Protestant players can convert regions of the board to either of their religious beliefs. They can take actions that let them try and convert specific points on the board or they can engage in religious debates.

The end of turn 5 (second turn of the scenario). The Protestants are making great progress in France and have pulled ahead to tie with the Ottomans. Now I just need to convince everyone at the table that the Ottomans are more of a threat than I am!

Let’s talk first about converting spaces. Converting a space is a contested roll between the Catholic and Protestant player. Whoever is attempting the conversion selects a space and then both players calculate their dice pool based on a variety of factors such as adjacent spaces, presence of troops who support that religion, adjacency of key religious figures, any card effects that are in play this round, etc. Once each player has a total number of dice, they roll looking for the highest single die. Highest result, with whoever wins ties changing over the game, succeeds and the space is either converted or remains the same. I really like this mechanic and it’s a lot of fun…if you’re one of the players involved. Only two players take this action, and the Protestant player will take it far more, sometimes resolving six or more attempts in one turn while everyone else sits around and waits. It’s very time consuming and can cause the game to drag, particularly if you’re not invested in the result. As the Protestant player in my most recent game I had a blast doing this, but I could see the rest of the table groan whenever I had a big turn coming where I was going to try and convert a lot of spaces. It’s a cool mechanic but eliciting this response in a six-player game is not ideal.

The debate rules I like quite a bit less. The Protestant and Catholic player can call debates between their two sides, and these can be used to convert large swaths of territory all in one go and potentially secure victory points by burning or denouncing the opposing debater. The debates themselves work a bit like combat, players get pools of dice and try to score “hits” by rolling fives and sixes on them, but with more steps used to determine who the two debaters will be rather than just knowing who the two armies are because they’re on the board. This mechanism is clearly central to the vision of the game’s design – the Protestant player’s home card (a card that is always available to them every turn) includes specific abilities for using Martin Luther in debates. That said, they have not played a very significant role in either of my games. The rules are complicated and there’s a non-zero chance that after all the steps involved in determining debaters and dice pools and such you will end up with a draw or a very minimal result. The promise of burning heretics at the stake lying sadly out of reach. The two religious factions also have a huge pool of potential debaters, many of whom have useful abilities for other parts of the game, and they can be overwhelming to keep track of. I can’t help but think the potential for them to die has bolstered their number creating the vast surplus of counters for the two players to track. Maybe as I play Here I Stand more I will find a new appreciation for the debate rules, but in a game that is so hard to get to the table it just doesn’t feel like the debate rules totally work. They’re not fundamentally broken or anything, but they feel off and, again, they also take up quite a bit of time and often only interest two of the players at a table of six.

These religion rules are something that was apparently significantly streamlined in Virgin Queen (the sequel to Here I Stand) and I am desperate to play it and see for myself. Tragically, Virgin Queen was already out of print back when I first played Here I Stand half a decade ago and there is still no clear timeline on a new edition going forward. Maybe some day I will decide to go mad and drop a stack of cash on one of the few copies available on the second-hand market, but until then I live in hope that GMT will finally reprint it.

End of turn 6, final turn of the tournament scenario. England makes a heroic push to pull up to be tied for first, but loses on the tiebreaker as I was further ahead in the previous turn. France is converted to Protestantism and under English rule!

To ConcludeLet’s be honest, Here I Stand is obviously not a game for everyone. It’s huge, it’s long, it has forty pages of rules, over a hundred cards, and don’t get me started on the many little counters with their own special rules you have to juggle. It’s nowhere near the most complicated game out there, it’s honestly middle of the road as far as card drive games go, but it is still a lot to take on board even before you start factoring in that a short game takes four to five hours. That all having been said, I feel confident saying that Here I Stand is one of my favourite games of all time. Nothing else I have played gives me the same feeling of excitement as it does. After each game I spend the next 24-36 hours buzzing with excitement at what I just experienced. It sucks you in to its historical sandbox and gives you the freedom to pull some levers while also helping to guide you into understanding even some of what was happening during a particularly chaotic period in European history. Is it perfect? Absolutely not. But I love it, nonetheless.

If after reading this entire review you think that Here I Stand sounds like a dreadful way to spend an afternoon or day, then please do not waste that time with it. Do not let my love for this game convince you to try it if you don’t think you would enjoy it. However, if after reading all of this you think that Here I Stand sounds fascinating, then you must play it. Nothing else will give you this experience, you must seek it out. Either way, trust your gut and what it tells you about Here I Stand. Mine tells me it’s hungry for more.

May 25, 2023

Joan of Arc: A History by Helen Castor

Helen Castor’s biography of Joan of Arc is a good account of The Maid’s life that doesn’t get too lost in the weeds and stands out in part as a result of her interesting choice of framing for the narrative. I enjoyed reading it but at the same time I think I may have somewhat ruined books like this for myself by digging a little too deep into the mines of history. As a result it left me a little unsatisfied in ways that will probably not affect most readers.

This is a fairly straightforward narrative history of the life of Joan of Arc and the times in which she lived. Castor does a good job establishing the necessary context of the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War that is crucial to understanding Joan of Arc and her importance which makes this a reasonably approachable book for people not already familiar with the Hundred YearsWar. What makes the narrative particularly interesting, though, is in how Castor engages with the sources for Joan’s life. Joan was famously burned at the stake in English-ruled France, but that followed a very lengthy and involved trial of her for heresy and sorcery. The records of that trial survive, as do records from a posthumous re-trial ordered by King Charles VII after the English had been driven from France. The evidence from these trials has traditionally been used to explore Joan’s early life, which is missing from other sources, as well as providing more context to what Joan thought as well as how she was remembered by those who met her. This is not unreasonable, but as Castor points out the trials were looking back on Joan’s legacy after the fact and thus can lead us into a teleological view of her life and personality - i.e. one defined by what we already know she did. Instead, Castor takes a framework based on the chronology of the sources - so after establishing appropriate context she begins when Joan first appears in the chronicles and only describes Joan’s early life at the end of the book when covering the trial. This is a novel approach and one that works very well.

That said, the problem I have with this book, and it is a personal problem, is that except for the trials there is very little source criticism in it. The thing I love most about Anne Curry’s books is when she gets into the nitty gritty of what the chronicles and other sources are, their strengths, weakness, when they were written, and their life since their writing. I love this kind of deep dive into source material and Castor is not doing that in this book. Now, she is not doing it for understandable reasons: most popular history readers don’t want that. This is what I mean when I say I may have slightly ruined these kinds of books for myself. I don’t always want to be reading academic history, but when I’m reading popular history I miss some of that more academic analysis.

A more serious criticism of the book would be that Castor owes a non-zero amount to Shakespeare in her characterization of Charles VII and his reign. The book falls into a portrayal of the French king as adrift between his advisors, in this case Castor places emphasis on his mother-in-law as the primary mover. I think that M.G.A. Vale’s biography of the king, written way back in the 1970s, did a great job of disproving the idea of Charles as man controlled by those around him, but Shakespeare is hard to overcome and I found it a bit frustrating to see in this book. I know from the bibliography that Castor is not unfamiliar with Vale’s work, so this is not an oversight but I would suspect more the result of how including a bit of that Shakespeare makes for a more interesting narrative that better fits the kind of book this is. It’s not a deal breaker, and hardly unique to Castor, but it is a bit of a personal bugbear of mine.

Overall, as a popular history of Joan of Arc this is a good read especially for people who aren’t already familiar with the Hundred Years War. For me, I think I prefer Kelly DeVries’ biography, but that is more of a pure military history and thus appeals to my military historian tendencies. I suspect that most people would get more out of Castor’s book than DeVries’.

May 22, 2023

Review - Seven Pines or Fair Oaks by Amabel Holland

My ongoing exploration of American Civil War games has once again brought me back to hex and counter after a run of operational games and I am pretty excited to be here. I love operational games, but there is something satisfying about a tactical hex and counter game, and I say this as someone who generally doesn’t find battles to be the most interesting lens through which to view military history. I think it’s because I love kinetic movement in my games and hex and counter is so good at that. I was also excited to be playing another Amabel Holland game. She is always an interesting designer and I adored Great Heathen Army, another hex and counter design from her, so I was excited to see what she brought to a more modern conflict.

Seven Pines; or, Fair Oaks (Seven Pines from now) is a game in the (now pretty much defunct) Shot and Shell Battle Series which covers battles from the mid-nineteenth century. It is a brigade level tactical hex and counter game with scenarios covering both days of the battle as well as a few alternative history scenarios. It plays relatively quickly, you could finish a game in under two hours if you know what you’re doing, and it’s not particularly complex. That said I did struggle with the rules in places and there was a lot of little pieces to remember that tripped me up from time to time. I would put some blame for this on the rulebook, which I found useful for getting the overall idea of how the game is played but frustrating when I was trying to find specific rules during play.

Overall, I’m not a fan of games that use a series rulebook as well as a second game specific rulebook that outlines the rules you need to know for this volume. I have two main grievances against this all too common practice. The first is that I have to learn a bunch of rules that end up being wrong or irrelevant. For example, in learning Seven Pines I read quite a few rules about how cavalry functioned only to discover that Seven Pines had no cavalry so that wouldn’t come up. Similarly, I learned that roads use half a movement point, except that in all of Seven Pines scenarios the roads are considered Muddy and cost a full movement point. A single rulebook that described the game I am about to play would be preferable. I also find them extremely frustrating to reference, because if I look a rule up in the main rulebook I also need to check the game specific rules to make sure it actually works that way in this game. Despite playing a lot of wargames I don’t actually enjoy flicking through rulebooks that much. I can understand why series rules can be a boon to game publishers, but as a consumer I do not care for them. That said, Seven Pines is far from the worst offender in this category and I appreciate that my dislike is not going to stop publishers from doing this.

Our first game at a little past the midway point in terms of gameplay if slightly beyond it in terms of absolute turns. While not an overwhelming number of counters, there is still a lot to keep track of here in terms of status, added effects like entrenchment or Elan, the special rules governing one division that required swapping counters or the rules limiting when Sedgwick could arrive. It’s far from a complex wargame, but it is one with a lot of little elements that are pretty key to the experience and so I found myself flicking through the rules a fair bit.

Rules layout nitpicks aside, Seven Pines is a very interesting game built on a fairly simple set of core rules. Movement is determined by unit type and the terrain modifiers are easy to remember which makes moving across the map quick and eliminates any need for a terrain chart. Combat is resolved by calculating the strength of the attacker, a sum of several factors, and then subtracting from that the sum of a die roll plus the defending unit’s strength. the defender rolling a die (or two) and adding their strength to that. The result is then referenced against a CRT based on what type of combat it was. While it’s a small thing it is interesting to have the die roll be totally in the hands of the defender - the attacker’s strength is entirely non-random, only the defense is unpredictable. I’m not sure I’ve played a game that does this and it caused a subtle shift in how we perceived combat. It was pretty cool.

The most interesting aspect of the design, though, is the activation system. There is a chart on the play aid made up of nine boxes (numbered zero to eight) divided into three main sections - red, yellow, and green. The on map brigades are grouped under a counter representing their overall commanders which is located on this chart. On your turn you choose a commander to activate, flip their counter over to indicate that they have activated this turn, and then move them one box down on the activation chart. You then take actions with all of their respective units and play passes to the other player. You do this in sequence until each division has either been activated or you have passed, nudging any un-activated divisions one space back up the chart. If your division commanders reach the zero box you will have to rally them before they can be activated again, and if they are there at game end your opponent receives a pile of VPs.

The opening turns of my Vassal playthrough, this is a fairly manageable array of counters and you can see at the board edges where reinforcements will come from - although it will be quite a few turns before they show up.

This system creates an immediate pressure as you want to activate every division each turn but each activation pushes them closer to being useless, or even a liability. Losing brigades will also push you further down the track and there are limits on your ability to move between color bands, as well as restrictions imposed on cooperation combat modifiers based on what band you are in. This system is really interesting and makes for some great decisions and tension about when you need to keep pushing your activations and when are safe enough to pass. There is also an element of gambling, as when you activate a commander in the number one box you roll a d6 to determine if they can activate. On a result of one you fail to activate and the division falls into the zero box, but any other result lets them activate and doesn’t move their counter at all. The tension on whether to keep pushing your luck or play it safe is really interesting. That said, we did find it to be a little extreme as the penalty can be very harsh and the chance a bit low. I know Amabel tends to like these harsher designs, but to my unrefined palate I would have liked a little more malleability to this roll - possibly it increases in risk each time you succeed or something. I would also like to see it show up in more places, maybe each time you cross a color band there’s a similar roll. But perhaps these ideas would dilute the mechanic and take the excitement from it.

The first scenario does a great job of easing you into the game by slowly adding more divisions as they arrive at the battle which gives the game an interesting tempo. You spend the first half of the game with only a handful of counters on the map before escalating to a much larger fight for the climactic finish. One thing I really like about American Civil War games is this system of reinforcements trickling as the battle escalates. In contrast I found the scenario of the second day overwhelming. I was playing the second day solitaire and having every unit on the map and within attacking distance of an enemy unit caused my brain to short circuit. I think in a solitaire game I prefer a slightly narrower range of options when it comes to deciding what to activate and lots of decisions around what to do with those activated units. In this scenario it felt like the opposite - all the decision space was in who and when to activate with the actions largely being Attack or Run Away. This surprised me as when I was playing my first game I thought this would be a great solitaire system but then when I tried it didn’t click with me at all.

In comparison to scenario one above, here is the set up for the battle’s second day which I played solitaire. Everyone is already on the map and the positions are very close to begin with. I found this a little overwhelming as a solitaire experience and a bit more of a grind when I was playing it.

The CRT is really interesting (do I say this a lot?). Shooting combat from infantry is very effective at causing disruption but rarely inflicts a step loss, while in contrast artillery are far more likely to do step losses at range but only sometimes disrupts. This may seem like an obvious bonus for artillery, but there are some interesting wrinkles the game adds to this. To move adjacent to enemy artillery you must charge them and charge attacks are first met by defensive fire. If the attacker is disrupted by defensive fire they cannot make an attack. However, taking significant losses does not stop an attack. This means that a charge against infantry is more likely to fail because you’re more likely to become disrupted but while charging artillery will be costly you are more likely to make an attack and potentially succeed in taking the position. This is a really interesting difference that isn’t obvious when first reading the rules. I love these kinds of things because you discover them as you play and it’s like the game letting you in on a secret.

I also quite like how Seven Pines handles unit steps. The game comes with an abundance of generic Step Counters which you pile beneath your units to represent their strength. When you take a step loss instead of flipping the counter or substituting another counter of the same unit you remove one of those counters from the stack. As I’ve been playing more hex and counter I’ve been interested in ways to model more than two states for each counter (i.e. a normal side vs. a disrupted/disordered side) and this is a fun system that is enhanced by the thickness of the counters that Hollandspiele uses.

You can easily see the relative strengths of the units at just a glance as the ones with more steps tower over the others. It’s a pretty cool effect and I liked this aesthetic - although with thinner counters I could see it being pretty frustrating.

Overall I had fun playing Seven Pines but I also don’t think it is a game I particularly want to revisit. There are elements of the system that my enthusiasm for faded as I played and there are ways that it models history that make me a lot less likely to want to play it again.

My main issue with Seven Pines is that it just felt a little too game-y. I admit that this is entirely a factor of my own desire to engage with games like this as historical arguments rather than purely games, but that is who I am so I found it frustrating. The activation system is very interesting but I don’t really understand what it is meant to model in the history of the battle and so it felt more like a game mechanism than something that gave me insight into how the historical actors made their decisions. I also found the choices of which brigades were assigned elite status, and how that elite status worked, to be kind of strange. The elite units were interesting mechanically but a little baffling historically.

What bothered me the most, however, was the lack of command control and the absence of generals. At the scale the game is on the units are lumped in with the brigades and brigades can all operate entirely separately within a division. This allows for an unrealistic level of independent movement on behalf of each counter and the creation of some very unusual battlefield positions. There are no leaders on the map that have to issue orders to their units so there is no need to keep units close together except that it is easier to get a combat bonus by working with units in the same division. It didn’t capture the chaos or confusion of these battles. The lack of leaders on the map is also strange given that the most famous result of this battle is the wounding of Confederate General Joe Johnston, which allowed for Robert E. Lee to take command and caused pretty significantly changed the Virginia theatre as a result. I found the fact that Johnston and McClellan are not really present in the game disappointing.

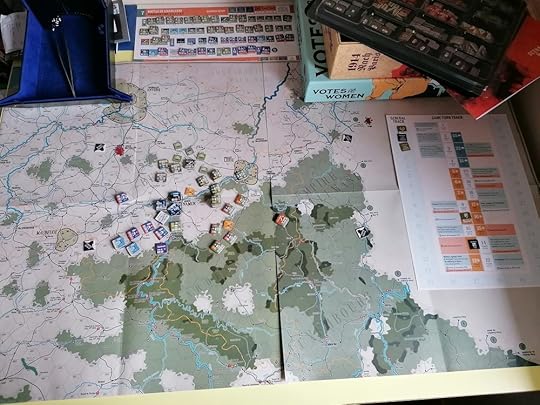

The combat also began to drag on me a bit. I think it’s interesting and in my first game I really enjoyed it. Where I struggled was when I tried to play Seven Pines solitaire. I’ll confess to not being great at math, and I struggled to do the calculations on my own. In combat you add up the attacker’s strength, which starts with step counters plus the star rating of the unit and then a series of modifiers based on various special rules, context, etc. From this you then subtract a die roll, either one or two d6 based on context, to which is added the defender’s step counters. I struggle to keep the two numbers in my head simultaneously, by the time I finished calculating the second number I’d forgotten the first, and so even though this calculation is not nearly as complex as, say, 1914 Nach Paris, I probably struggled with it more. Maybe I should have done like I did in 1914 and used my phone to track the values. This wasn’t as much of a problem in a two player game where we each tracked our own unit’s strength, but with a game like this if I can’t enjoy playing it solitaire it is going to severely limit its shelf life.

My second game quickly found me in this situation - lots of potential attacks to grind out a slow win for one side or the other. This ended up feeling rather tedious. Some of this was the result of the scenario design - I much preferred the first one - but I think it also reflected a waning enthusiasm for the game itself on my part.

Overall, I enjoyed my time with Seven Pines but I won’t be rushing to unpack it again. I found my excitement diminishing as I played it more, which isn’t a great sign. It’s a fascinating bit of game design and I’m really happy I played it - and I did genuinely enjoy my first game of it. It has a lot going for it and if you like hex and counter American Civil War games it is probably worth your time to try it once - I’m just not sure it is worth more of your time than that.

May 18, 2023

The Confederate Battle Flag by John Coski

I want to be positive to begin with, because I will say some unkind things in this review. This was a deeply frustrating book to read and at times a labor just to get to the very end. However, I learned a lot about the history of the Confederate flag from reading it. I feel much more informed about its history and better qualified to examine its role in American society than I was before I read it. In that regard this book was an unqualified success - I got out of the experience what I most hoped to when I started reading it. However, getting there was something of a chore. I don’t mean in terms of the writing, which is largely fine even if it can drag at times with the inclusion of too many case studies with too much superfluous detail. Instead, it is in Coski’s analysis of the history of the flag that the problems begin to arise.

Many of my frustrations with this book are arguably best summarised by this passage:

The motives of each state for embracing the St. Andrew’s cross battle flag as part of its official symbollism are murky and open to debate. Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina did so during the eventful 1950s and 1960s. The coincidence of the Civil War Centennial and the civil rights movement makes it difficult to discern whether the states intended the battle flag as an historical war memorial or as a gesture of defiance to federally mandated integration— John Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag, p. 237

This is not the only time Coski expresses an opinion in this vein and it is made particularly baffling because throughout the text Coski emphasises the links between the adoption and wider use of the Confederate battle flag and opposition to the Civil Rights Movement. While there may not be a smoking gun showing that the incorporation of the battle flag into several southern states’ flags was a racist reaction to federal pressure to provide equal rights to black Americans, the evidence is still overwhelming and to deny it is to be deliberately obtuse. Coski’s reluctance to see what is clearly before him was a particularly stark contrast with my recent reading of Ty Seidule’s Robert E. Lee and Me. Seidule was able to see what was happening in similar cases with perfect clarity. In fact, at times Coski is able to clearly identify the issue, such as in this passage:

Confederate symbols in public spaces - often vestiges of the flag fad era - can exist unnoticed for decades. They are tangible reminders of the former prominence of Confederate veterans and their progeny in southern life - and, not coincidentally, of the exclusion of African Americans from mainstreem public life during the Jim Crow era.— John Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag, p. 275

The book thus frequently comes across as in conflict with itself. Coski is reluctant to acknowledge what seems obvious for pages and then will do so in a paragraph before going back to denying it in the next chapter. It does not help that the book contains little to no information about Reconstruction or the Jim Crow south. In fact, the book is almost entirely lacking in wider context for any of the anecdotes or case studies contained within it. Readers will really need to already be steeped in the history of neo-Confederate movements of the 20th century to get much out of this book, because you will have to provide your own analysis to supplement or correct what is contained within its pages. While no expert myself, I have read enough to have noticed the glaring absences in Coski’s text.

A particularly worrying trend that runs through the book but most prominently emerges in its concluding chapters is the indication that Coski believes, on some level, that the cause of the American Civil War was a dispute over states’ rights. While it is clear from the text as a whole that he does not deny slavery’s role in causing the war, it seems that he believes - or at least argues - that the issue of states rights was at least of comparable importance to slavery in causing the war. This factors into his explanations as to why individuals might wave a Confederate flag as a non-racist symbol. In my eyes, this ignores vast amounts of research on the origins of the American Civil War and engages in a level of Lost Cause-ism.

This is aggravated even further by the fact that discussion of the Lost Cause is almost entirely absent from the book. One would think that an account of the changing meaning of the flags of the Confederacy would tackle how the Lost Cause shaped American’s understanding of the war but in this case you would be wrong. The book skips over most of the early twentieth century and spends far more time on free speech disputes during the 1990s than it does to Jim Crow or the Lost Cause. The analysis of a case study of a black man shooting and killing a white man for, apparently, waving the Confederate flag on his truck is given far more prominence than cases of lynching and repression of Black Americans during the Jim Crow era.

The book also seems to overly emphasise white voices and those of neo-Confederate heritage groups over those of black Americans who have suffered under the white supremacist policies that have dominated America and particularly the southern states that made up the Confederacy. These voices are not entirely absent, but the book does not really engage with scholarship on racism in America and skips past the Jim Crow era with very little description. It often takes a framing that steps very close to the line, without fully embracing it, of suggesting that Black people were fine with Confederate flags before the 1950s, so why all the fuss in the 1990s? It makes little effort to consider the context under which Black Americans lived their lives in those preceding decades and what these symbols might mean to them.

While Coski insists in the introduction that he is adopting a purely relativist approach, i.e. that the Confederate flag has no objective meaning but means what supporters/detractors think it does and can contain these many meanings simultaneously, he does periodically engage in the notion that historical commemoration of the flag is an objective and unobjectionable use of it. Thus the use of the flag by neo-Confederate groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans or the United Daughters of the Confederacy should be seen as neutral and only perverted by groups like the KKK. While some passages contradict this notion, a common theme in a book full of self-contradiction, it is nevertheless present and frustrating.

I also resent the notion presented periodically that the Confederate battle flag as an emblem of white southern identity. While I acknowledge that Coski is framing it this way to clarify that most black southerners would not identify with the flag, it also concedes to the idea that all southerners were Confederates or are Confederate sympathisers. Parts of the South didn’t secede, some key Union generals were southerners, and not every modern southerner is a neo-Confederate and I think this framing erases that internal conflict in favour of portraying the South and the Confederacy as being almost the same thing. This is the perspective that neo-Confederate groups want, and I don’t intend to concede that position to them.

Fundamentally, Coski has done an excellent job at pulling together many threads of how the Confederate flag has been used by historical actors from the Civil War through the turn of the 21st century. However, the pattern he has woven with those threads is of a more questionable quality. In terms of analysis this book was a very frustrating read, swaying wildly between interesting points and analysis that seemed to fly in the face of the obvious. Coski bends over backwards to make this an issue where “both sides” can be in the wrong, and in so doing delivers an unsatisfying and limited analysis of the Confederate Flag’s role in modern society. I learned a lot from this book and it helped expand my understanding of the flag’s history, but I also found myself frequently annoyed and frustrated by it and would not recommend it to pretty much anyone. If you feel you need to know more about the context of the Confederate Battle Flags’ resurgence after the war then this book will give you that, but that is some very niche knowledge and unless you have a reason for needing that knowledge I wouldn’t recommend reading this book to acquire it.

May 8, 2023

Half of a Review of The Late Unpleasantness by Steve Ruwe

I want to open with two confessions straight out of the gate. The first is that I have only played half of Steve Ruwe’s The Late Unpleasantness: Two Campaigns to Take Richmond. As the sub-title implies, there are two games in this box and I have only played one of them. The two campaigns are If It Takes All Summer, on Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign, and The Gates of Richmond, on the Seven Days Battles in 1862. I have only played the latter, but I feel like my experience with it is sufficient to review that part of the game even if this is not a review of the whole box. My second confession is this: I didn’t really enjoy The Gates of Richmond. Usually games I don’t enjoy I don’t write about, because expressing my lack of enjoyment isn’t very much fun for me and this blog is first and foremost a hobby. However, in this case I had what I felt were sufficient thoughts on the game and its representation of history that it would be worth writing about it, even if in the end I don’t think the game itself is very interesting to play.

The Game

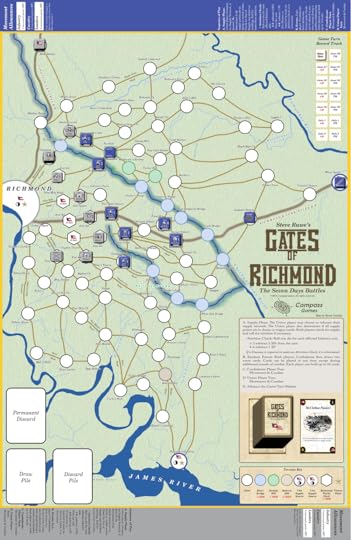

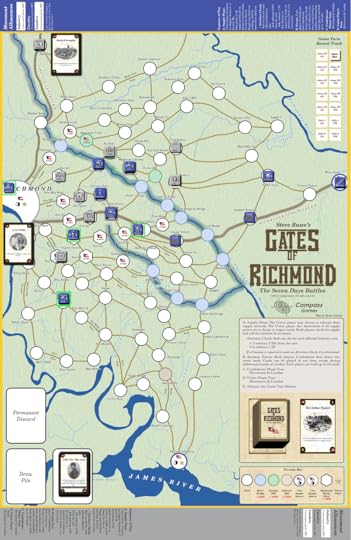

The initial set up - there is a reasonably important element of free deployment for both sides. This is revealing all the units - in theory you should mask what units are where but we both found it clunky and eventually abandoned it.

I want to talk a bit about the game itself and why I don’t think it quite works before moving on to what I think is interesting about it and why I wanted to write about my experience playing it. The Late Unpleasantness: Gates of Richmond is an operational level game of the Seven Days Battles in 1862 between Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan. The Seven Days Battles made Lee’s reputation and was yet another major setback for the United States after the disaster of First Bull Run the previous year. The game is played at Division level with a relatively low counter number on a point to point map. It uses a fairly simple fog of war system, including dummy units, supply rules, and some card play (but it is not a card driven game). All the relevant rules to play the game fit in to about 8 pages, which is a positive. The core problem with The Late Unpleasantness is that it’s disparate elements don’t fit together very well and the whole experience is a bit wonky, which made for an overall unsatisfying game in my opinion. To my eyes the three main flaws with the game are the cards, the usability, and how it chooses to represent the history. It is not entirely without positives, though, and there is an element of the combat system that I did actually quite like.

The cards in The Late Unpleasantness are just really unsatisfying. Both players draw from a shared deck but many cards only benefit one side, so you can end up with a hand of cards that are just useless to you. You start with eight cards and can play as many as you want almost whenever you want (with one exception to be covered later), furthermore the usefulness of the cards varies wildly. These elements can create some extremely swingy outcomes. They should at a minimum have been separate decks for the two sides and the cards needed a lot more refining and development, but honestly you could probably just remove them from the game and have a better experience.

End of Turn 1 - AP Hill pushes the Union flank and Lee and Stuart push past to threaten Union supply. Instead of focusing on the idea of destroying the United States’ army, the goal of Lee in this game is takin the supply points which I wasn’t a fan off if I’m honest.

In terms of how the game handles fog of war, this game should have been a block game. Each Division is only one counter and having divisions with counters representing current strength stacked under them and fog of war counters on top is just very clunky. This game should have used blocks and a separate sheet to track damage, like the Conquerors series from Shakos games. While this wouldn’t fix all of its problems it would have been a step in the right direction by making the game much easier and smoother to play.

In terms of how the game represents history, I am sympathetic to the challenges the designer faced. The history of the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles is a tricky thing to represent. Most historians blame the disastrous outcome for the US as being the result of General McClellan’s unwillingness to fight. He outnumbered the Confederates but due to his own reluctance, deception on the part of the Confederates, and Lee’s aggression he was ultimately defeated. The challenge for game designers is that the solution to the Peninsula Campaign, and in particular this phase of it, is obvious to anyone who has studied history. McClellan should have attacked the Richmond works - they were badly undermanned and only looked strong due to trickery on the part of the Confederate commander. McClellan almost certainly could have punched through them and taken the city - but he didn’t believe he could and so he didn’t. The only way to capture the history of this campaign is to make the player think like McClellan. This game doesn’t do that, and so our game ended with my opponent punching through Richmond’s weak defenses - something that was only slightly delayed by rule that causes 50% of attacks on these positions to fail - and take the city on like turn 3. It was pretty underwhelming and did make me wonder if the game’s system was designed around the more aggressive tactics of Grant’s Overland Campaign and only moderately adjusted for this radically different campaign.

Some good rolls allow the US Army to break a hole in the Richmond defenses and then a card that gives +1 movement allows a Union division to march straight into Richmond unopposed, ending the game late in the second turn. A very underwhelming finish.

These are not the sum total of this game’s flaws. It feels weird to me that the map is clearly for a longer Peninsula Campaign but the scenario on the box is just the Seven Days Battles - the game would be better if it started earlier and I wonder if the designer’s unfortunate early death may have cut short the development of a more robust campaign scenario. The rest of the game just doesn’t quite click, but it is not without a few diamonds, small though they may be.

Overall, I’m not very impressed with combat in this game but I will spare you a list of its faults and focus instead on what I liked. Each CRT result has a column you roll on to determine if the battle has concluded. You roll a d6 and it will tell you if one side or the other retreats, or if you keep fighting. I quite like the idea that at the start of a fight you might not know how many rounds it will last. There are options open to you to try and abandon a battle that is still going but they are no sure thing, and together I think these systems represent an interesting way to inject a bit more chaos and unpredictability into the combat - which are things that I like in my wargame! Unfortunately, I think they are let down by the rest of the design, but if there is one idea I would be curious to see used elsewhere this is it.

The Lost CauseOne of my current topics of fascination is how the Lost Cause is represented in tabletop wargames. I want to preface this now that while I will be talking about neo-Confederate ideas and myths, I’m not declaring that the designer or publisher of this (or other) games are dyed in the wool neo-Confederates. The Lost Cause has been pervasive throughout American culture for well over a century. It is possible to believe its tenants without fully supporting its cause but if we never take the time to interrogate those tenants and how the appear in our lives we will never uproot it’s malicious influence on our society.

To my eyes The Late Unpleasantness has two noticeable elements of Lost Cause-ism in it - its name and the representation of the respective leadership between the two sides.