Stuart Ellis-Gorman's Blog, page 10

August 28, 2023

Discussing the Lost Cause with Beyond Solitaire

I was lucky enough to be invited to appear on Dr. Liz “Beyond Solitaire” Davidson’s podcast a few weeks back. We discussed my ongoing project on the Lost Cause in historical wargaming as well as a range of subjects, including why we are drawn to difficult subjects and why we might want to play and write about games we know that we won’t actually enjoy playing. It was a great discussion and I think provides some excellent context to the We Intend to Move on Your Works project. You can listen to the podcast via all main podcast distributors or you can watch it on YouTube below:

August 22, 2023

Review - Longstreet Attacks by Hermann Luttmann

Few names loom larger in the, for lack of a better word, wargame-ology of current American Civil War games than Hermann Luttmann. A Most Fearful Sacrifice, his enormous game on the full battle of Gettysburg, has won countless awards and is easily among the most talked about games of 2022. Before that he was widely known for his Blind Swords system, which includes several battles from the Franco-Prussian War but is dominated by American Civil War games. Seeing as I am currently undertaking a tour of ACW designs it was inevitable that I would play a few Luttmann designs. As my entry point into the ludography of Luttmann I selected Longstreet Attacks. This wasn’t because I thought it to be the best entry into the system, many people have said it is not, but rather a choice based on the game’s subject. I wanted to play something Gettysburg to mark the 160th anniversary back in July and I thought playing a game about the second day on the 2nd of July would be appropriate. I managed to approximately time the beginning of my game with the timing of the famous attack, but the actual playing of the game took a fair bit longer than Longstreet’s disastrous assault did. I also think the figure of Longstreet and his position in the Lost Cause myth is an interesting one, and something that is very germane to my project.

Blind SwordsFor those who may not know, Blind Swords is a chit pull, regimental level tactical hex and counter game system of I would say medium complexity. Lighter than Great Battles of the American Civil War, but by not without its chrome and complexity. The core is pretty easy to grasp, but there’s enough little nuance in the rules that you may find yourself having completely forgotten some small element until after you finish playing a game – I certainly did. To my mind, there are three things that stand out in Blind Swords and that I found utterly gripping, and please bear with me, they are: the chit pull, the combat results table, and the orders system. Wargaming baby, I’m nothing if not consistent in my love of the seemingly mundane at least!

I wouldn’t say I have a ton of experience with chit pull, but I’ve certainly played other systems that use it. I’ve played a few Great Battles of the American Civil War games, with its very complex chit pull, and I’ve dabbled in some lighter games where you just dump everybody in the cup and resolve to see what order each unit activates in. I mention this because I think the chit pull in Blind Swords is the most interesting version I’ve encountered so far by a mile. It’s relatively simple (although the Vassal mods implementation of it is a bit fiddly) but also really engaging. This is due to both how it handles events and how each activation is resolved.

I’ll start with the latter first. Unlike in something like GBACW where if you pull a division, you activate every unit in that division, in Blind Swords you first have to roll a die to determine if you activate fully or have to take a limited activation and then you only pick one brigade under that commander to activate. Then you mark that brigade as having been activated and if you have brigades under that commander that still need to activate you put the chit back in the cup to draw again in the future. I really like this, it makes the back and forth much faster as you’re usually only activated between two and five units on each chit pull, not entire wings of your army. It also makes for a more interesting flow to the battle, as you never know when another brigade in that division will activate or even if they will fully activate – so how risky do you want to play? A big aggressive move earlier could see that brigade stranded without support as your opponent plans their counterattack. It keeps the tension high on each chit pull and is overall a really satisfying experience.

The events also add a lot of excellent spice to the gameplay. Each turn you will place a number of events from your side into the cup, usually some you get to pick while others are added at random from the available pool. When you pull events, some will trigger immediately while others can be held and played later. This adds a lot more variety to what can happen in each round and for the most part the events are interesting without being game breaking. What I liked even more, though, was the Fog of War event that always goes into the cup. When this is drawn you roll on a table and an event triggers for one of the players. The best of these by far is the one that lets you move an enemy unit one space. Few things are more satisfying than taking control of an enemy piece. It is not only satisfying, though, it is also a great example of the chaos of battle and how sub-optimal decisions can be made in the heat of the moment. Game systems can struggle to capture one leader making a poor decision or an error that the commander, with their wider perspective, never would but by handing control to your opponent for one move you can create that sensation of a subordinate completely screwing up. If I had to distill Blind Swords down to one inspired rule, it would be this – I love it.

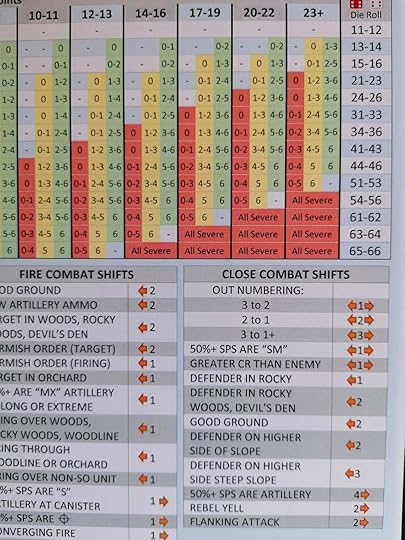

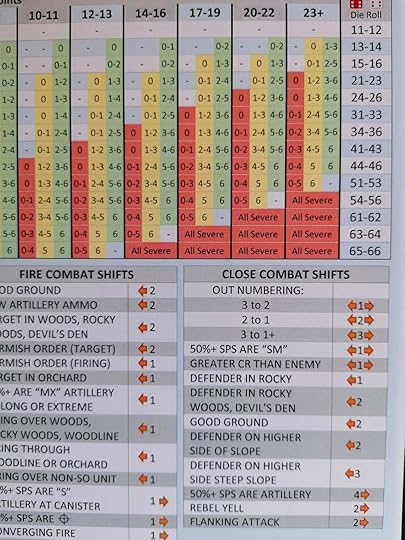

I am less certain that I am in love with the combat results table, but I am certainly intrigued by it. After calculating your attack strength you roll a d66, meaning you roll two d6 one of which represents a tens and the other a ones digit, so you get a number between 11 and 66. You then consult that row of the CRT against the column for your strength and look for the cohesion rating of your target – if you hit it will be in a colored band that will tell you what table you’re opponent has to roll on to see how their unit responds to being shot at. This could have no effect, or it could be utterly disastrous. I’m honestly not convinced by the first table; I think it works but I don’t love it. My issue is less with the table and more with how central the Cohesion Rating is to many of the game’s systems and the mixed feelings I have about it – but I’ll talk more about that later in the review.

An excerpt from the first of the two CRTs. You can see the dice results on the righthand column, the columns for attack strength, and the colored boxes for target CR values. You can also see here the many, many column shifts you factor in each combat, which can be a little overwhelming at times.

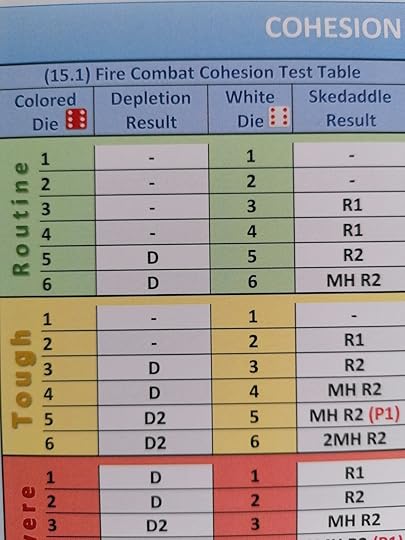

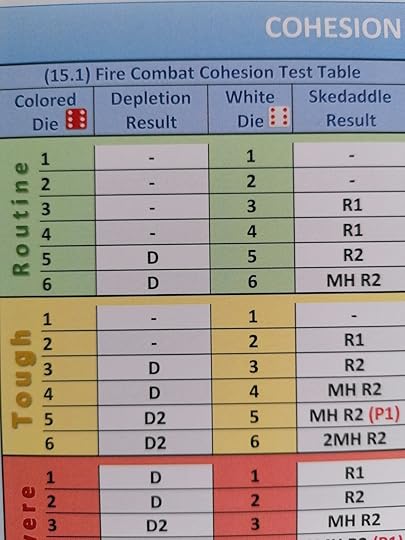

The second table, though, I think I love that. The defender must now also roll two d6s, one of which will determine whether his units are Battleworn (flipped over to a weaker side) and the other (brilliantly known as the Skedaddle Table) determines whether they retreat and if so, how far. Splitting these two outcomes and having them be randomly determined separately is great, I love it. It can create interesting situations where units take a ton of punishment but refuse to give up their position, or where completely healthy units break and run but are perfectly healthy and able to be sent back into the fight. It generates a valuable diversity of outcomes to combat with only a minimum amount of rules overhead – the best of both worlds.

The table that defenders will be rolling on - this one is for ranged combat, close combat has a separate one. I love the use of Skedaddle here. If I had a critique it is with the choice to use a D for Depletion as the result that inflicts a Battleworn status. We spent most of our game saying Disordered or Disrupted instead of Battleworn because of this.

Now, let’s talk orders. I think orders in wargames are really interesting. Last year I picked The Flowers of the Forest as my favorite game I played that year, and that’s a game entirely about giving orders and then regretting them utterly. Blind Swords is not that, and in fact is quite forgiving in how it handles orders but still manages to be interesting. When you activate a brigade, you pick an order from the four options: Attack, Defend, Maneuver, or Regroup. What order you pick will determine what they can do with their activation, with no order allowing you to do everything you want. The key factors you have to balance are how far you can move, what kinds of attacks you can make, and what options you have for rallying and rebuilding injured units. While Attack and Maneuver will be by far the most frequently used in any game, the situational usefulness of the other two cannot be denied and they certainly gave me food for thought as I was planning my strategy. This system isn’t the greatest thing in wargaming, but it does strike just the right balance between complexity and generating interesting decisions and I think that is worth praising.

Before we get on to my main critique of Longstreet Attacks, I wanted to do a quick bullet list of my nitpicks with Blind Swords. These are not irredeemable flaws, but they are things that annoyed me enough that they provided a mild detriment to my truly loving what is otherwise an excellent system. My complaints are thus:

I hate calculating strength ratios. When I saw the initial combat system for Blind Swords, I was excited that it used unit strength, and then I saw that you have to calculate strength ratios to determine column shifts in close combat. I hate this.

Cohesion Rating is a cool stat, but it feels a bit too critical. CR 4 and 5 units are so much better than CR 2 ones. CR not only determines how likely you are to be hit in combat, it also can trigger column shifts in close combat and having a CR of 2 or less makes you susceptible to Panic results triggered by neighboring combats. It just feels a little too critical of a stat and that makes the variability present in some units a bit frustrating, which is something I’ll go into more below, but it was a frequent source of frustration for me.

The leader death rules are pretty underwhelming. Given the high rate of wounding and death for officers in the ACW this is now something I look for in the games I play. Leader death is a possibility from drawing the Fog of War chit, with a separate table to see who, if anyone, died. It doesn’t happen all that often, and in my game the only leader who died was replaced by a leader with the exact same activation stat. This was pretty underwhelming and basically had no impact on the game, which was disappointing. I’d like to see it trigger more often.

The games are too long. The grand campaign of Longstreet Attacks took me over a dozen hours and from what I can see this seems to be pretty standard for the system as a whole. If my opponent and I had played in person in one sitting, as opposed to over Vassal across a number of evenings, it would have gone faster but I have yet to see a Blind Swords ACW game with a full battle playable in under four hours and that’s a bit of a bummer. Don’t get me wrong, I love a long game some of the time but it’s not an every week kind of gaming experience and long games have to be really amazing to warrant me returning to them again and again.

Those are my main nit-picks. The core system is good but we’re not here to just talk about Blind Swords in the abstract. This is a review of Longstreet Attacks specifically, so what did I think of that game specifically? The short version is that while I really like Blind Swords as a system and I’m sure there is a Blind Swords game out there for me, I’m sure that that game is not Longstreet Attacks. The long version is below.

Longstreet AttacksI want to open with the fact that I think Longstreet Attacks is a fine game. I enjoyed my time playing it. If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have played it for nearly as long as I did. I found the Little Round Top scenario a little tedious, but it was also a learning scenario so that’s kind of understandable. The main campaign battle was definitely more interesting, but I also found it at times very frustrating. This was the kind of frustration where I wanted to love this game, but there were elements of it that prevented me from doing so and that drove my frustration with it. It’s a very specific kind of frustration, maybe the worst kind, and I want to try and explain why. I’m going to open with a few minor critiques of things that just didn’t work for me, but I can understand may be the result of my own personal preferences, before getting to the real meat of my problem with Longstreet Attacks: the narrative of the battle that its systems create.

While I think it seems natural to pick Little Round Top as an intro scenario with its small counter density, the terrain proved incredibly frustrating while I was playing the game and in both games (this and the grand battle) the Confederates barely launched a sustained assault due to be bogged down in the rocky terrain.

In terms of pure mechanics, the element of Longstreet Attacks that frustrated me the most was its victory conditions. Across the map are scattered various victory point hexes for one side or the other, or both, that grant VPs at the end of each turn. There are also three hexes that if the Confederacy can take them will generate an automatic victory. I’m generally not a fan of victory points in wargames and I’m really not a fan of wargames that generate points every turn for controlling a space. I need a solid justification for why controlling this hex is so important to overall victory and if it’s going to be for a number of turns, I really need to understand why controlling this hex for 20 minutes (the in-game turn length in Longstreet Attacks) matters as much as who controls it at the end of the game. Victory conditions are something I have a mild obsession with, and I don’t like ones that are too game-y. I want the terms of victory to convey something about the historical objectives of the two sides.

This gets to my other problem with Longstreet Attacks’ victory conditions, and one that I accept is derived from my own opinions on what I want to see in a historical game. The victory point hexes are scattered in a way that nudges players towards control of areas that were central to the historic battle. To put it another way, the victory conditions are set to direct players towards recreating the historical course of the assault. This means that hexes that objectively would be worthless to control in terms of overall strategic value to the battle can be worth quite a lot of points because historically that was a point of fierce fighting. This feels too artificial to me. I want the game to have victory conditions that make me understand the strategic goals of the battle, not ones that try to move me along on rails to recreate what the historical commanders did. I know for other people this won’t be as big of a problem, but this is my review and so I get to say I don’t like it.

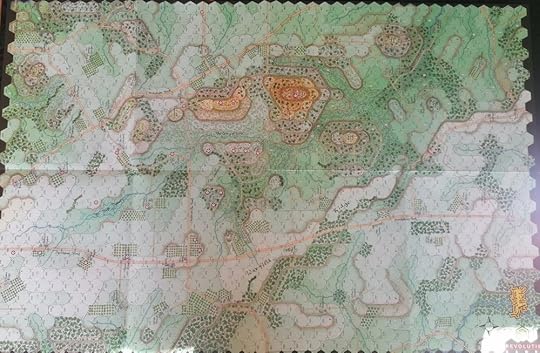

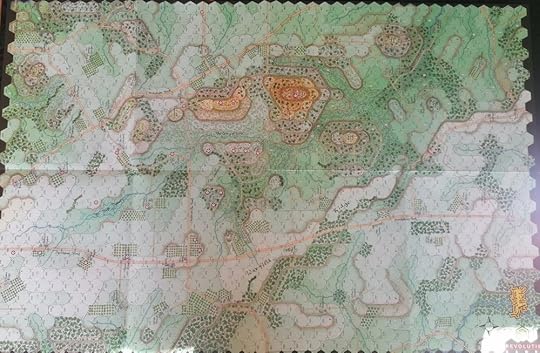

I haven’t really brought it up in the review because I think its already widely covered elsewhere, but the game does come with this very nice Rich Barber map. If I had to be a slight heretic I would say that I found the terrain around the Round Tops to be a bit too busy and hard to read at times, but there’s no denying the map’s overall aesthetic appeal.

The victory conditions frustrated me because they felt more tedious and less interesting than I wanted, but they were not my greatest issue with Longstreet Attacks. My objection to Longstreet Attacks could arguably be oversimplified into the idea that the Union units Cohesion Ratings are too low, and the Confederates’ ratings are too high, but it’s more than that. Explaining it, however, is going to take a bit of time so I ask you please for your indulgence.

I want to talk about the narrative of Longstreet Attacks, and in examining that narrative I am only considering the emergent story that comes through via the game’s mechanisms. Not the framing that might be in the rulebook or with the scenario description, nor any designer notes. Instead, I just want to consider what version of Longstreet’s attack on the 2nd of July this game told me when I spent many hours of my life playing it. To understand why I care so much about this we need to talk a little bit about Longstreet as a man and his unusual position within the historiography of the American Civil War.

Longstreet was a general who spent almost the entire war serving under Robert E Lee. Lee affectionately called Longstreet his “Old War Horse” and he was one of the few generals who was able to complain to Lee about his strategies and openly disagree with the general. They were very close, especially after the death of “Stonewall” Jackson in May of 1863, and so you would expect Longstreet to hold a similarly hallowed position within the halls of Confederate memory as Lee and Jackson do. You would be wrong, and to understand why you need to know what Longstreet did after the war. To cut a very long story very short, Longstreet moved to Louisiana, joined the Republican party, and argued in support of other ex-Confederates joining the party and accepting Reconstruction – not out of the pure goodness of his heart, mind, he believed it necessary to dilute black involvement in politics, but still a radical approach for a man of his legacy. This put him in direct conflict with Redeemers like the KKK, the White League, and other organizations that sought to violently restore a white supremacist order to the southern United States. This came to a dramatic head in 1874 at the Battle of Liberty Place, when an armed group of white supremacists attempted to storm the Louisiana capital and depose the Reconstruction era government there. Longstreet, as an officer in the state militia, led a force of mixed-race militiamen to oppose them. Over a hundred men died, Longstreet was captured trying to negotiate with the White League, and President Grant eventually sent in Federal troops to quell the unrest. An ex-Confederate hero leading black troops against his fellow white southerners was an unforgivable sin. Former comrades in arms, including notorious Lost Cause promoter Jubal Early, denounced Longstreet and set about rewriting the annals of history to make him a scapegoat for the failures of the Confederacy. Most prominent among these was the great defeat at Gettysburg, now placed solidly at the feet of one General Longstreet.

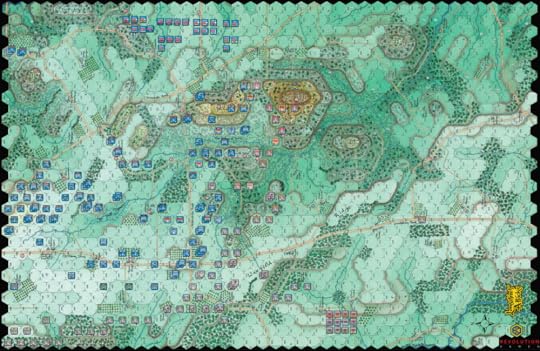

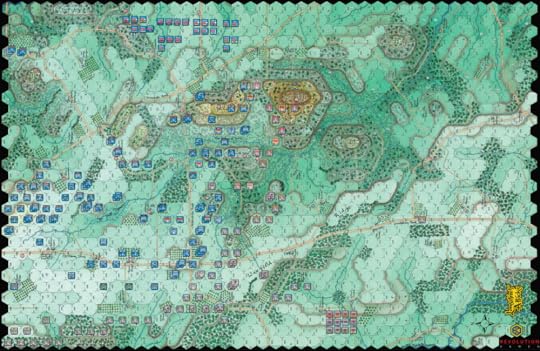

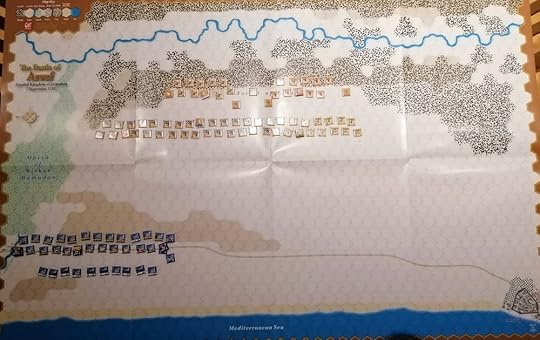

The beginning of McLaws attack in our game. Hood has stalled out trying to take the Round Tops and Devil’s Den (he eventually took the latter but it was a very long time coming). McLaws would prove far more successful against the Union center. It may look like he is outnumbered but those Union counters don’t stand much of a chance against his attack.

The reason this is relevant for Longstreet Attacks is that there are kind of two conflicting possible narratives for what this attack means. Longstreet famously (or infamously, depending on your perspective) did not like the plan of attack on the 2nd of July 1863. He thought it risky and unlikely to work and argued strenuously with Lee for a different plan – ideally a movement of the whole army towards the Union rear to cut off their access to Washington and force them to attack the new Confederate position instead. Lee refused to consider this idea, and Longstreet was forced to go ahead with his assault. The assault ultimately failed, securing no significant ground and causing the death and wounding of hundreds of soldiers the Confederacy couldn’t afford to lose. Yes, the Union suffered casualties too, but not enough to seriously endanger the Army of the Potomac. This narrative is one where Longstreet’s attack is a doomed assault, well executed but ill-conceived from the start. Not quite so disastrous as Pickett’s Charge, but still a flawed strategy that came at enormous cost.

The alternative narrative accuses Longstreet of dragging his feet, launching his attack too late in the day and failing to really put his heart into the attack. It was doomed not because it was tactically unsound but because its commander did not believe in it and botched the operation. No surprise this was the narrative pushed by Early and other architects of the Lost Cause, and for a long time it was the dominant narrative, but it was built on a foundation of lies (often literally, such as a fictional order that Longstreet was to launch his attack at dawn. He was to ready his troops at dawn, not attack). My problem with Longstreet Attacks the game is that in many ways it feels more in line with this narrative than with the actual history, an experience that was exacerbated by my choice to read Stephen Sears’ massive history of Gettysburg at the same time I was playing Longstreet.

In Longstreet Attacks the Confederate units are just better than the Union ones. They often have higher strength, and they always have a higher cohesion rating. Unless they suffer morale penalties from combat most of the units are immune to a Panic result in combat. The smell of the notorious Confederate sentiment “one southerner could whip any ten Yankees” comes off the game in waves. One cannot deny that the Confederate generals gave the attack their all and that many units withstood stunning amounts of punishment to attack Union positions, but the defenders were no callow bunch of cowards breaking at the first sign of attack. The battle on the Union left was chaotic because General Sickles had left his position and stretched his lines too thin. Arguably the low cohesion ratings could reflect this poor position and chaotic command, except that even the units that were outside of Sickle’s Corp often have this same poor cohesion rating – it is a trait of the Union army not just those units that were in chaos. And surely that chaos could be reflected in the game’s use of Disruption morale penalties rather than baked in stats. It seems a bit egregious that often Confederate units on their reduced Battleworn side are still superior to many Union regiments – especially when cohesion rating is so crucial to determining when a hit is inflicted in combat.

My somewhat crude illustration showing the distribution of Cohesion Ratings between the two sides. The far left are units with CR 5 while the far right are those with a CR of 2. It can be hard to fully grasp the significance of this without knowing from experience how much better a CR of 4 is over a CR of 2. It also doesn’t show the strength distribution, where many of the higher CR Union units are either very low strength and/or sharpshooters, who only have a single step of strength. This is only infantry counters, artillery are mostly CR 3 on both sides.

To avoid getting too lost in the weeds let me try and distill the matter. Playing as the Union in Longstreet Attacks I did not feel like I was a general trying to fix a mistake made by my inferior officer, i.e., Sickles. I felt like a man tasked with taking green troops into combat and repeatedly frustrated by their failure to perform while my opponents stormtroopers ran roughshod over my positions. My only saving grace being the terrain and a desperate prayer for night to come soon and bring an end to the attack.

I made little progress in stemming the Confederate attack – for all its strengths Blind Swords seems like a system poorly suited to highly attrition conflict. Battleworn status can be recovered more easily if your CR is higher, like for nearly all Confederate units, and there is no permanent loss that cannot be restored in time. Confederates could push my lines back so far that the handful of units I forced to be Battleworn could end up being far enough from the front line to rebuild the next turn, undoing all my hard work. This may be a slightly more fundamental issue with Blind Swords, at least as it is in this early entry. It’s not built for sustained attrition and may not be suited to horrifically bloody engagements like the second day of Gettysburg. Perhaps it is for that reason that there are no Blind Swords games on other particularly violent engagements like Shiloh, Antietam, or the many battles of the Overland Campaign. Not every system can do everything and this may be a limitation of Blind Swords.

Near the end of our game of Longstreet Attacks. McLaws has successfully pushed back the Union center - many of those units are broken and useless in combat. Anderson is having a harder time on the Union right, while Hood’s attack on Little Round Top never really came to anything and now Law is engaging in a wildly ahistorical flanking maneuver that has placed him awkwardly in the middle of the Union activation chits. While the position is bad, this a strong Union victory as the attack went too slow to secure the VPs it needed to win.

I also saw no sign of fatigue in the Confederates as the game progressed, no indication that their losses were adding up, no indication that the assault was running out of steam and that it was asking more of its men that they could deliver. Instead, it seemed as if the only way to stop the Confederate attack was for night to come, suggesting that maybe had Longstreet attacked earlier he would have been victorious. I got no sense that maybe Longstreet would see that his attack had failed, his forces were stalling, and he had no reserves to commit, and order a withdrawal of his units. No, given infinite time these Rebels would nearly always overrun the Union army, and to me that reeks of the story of Jubal Early and his cohort discarding history to settle a personal vendetta. And it saps my ability to enjoy the game.

ConclusionIn my final assessment I did really enjoy Blind Swords as a system, but I found the emergent narrative of Longstreet Attacks somewhat poisoned my ability to love it. I was frustrated, and not in a fun way. Blind Swords is a system that really embraces the chaos of warfare and historical simulation, and that is something I love dearly. I think historical games need chaos because history is not predictable. However, I also think historical games need to be honest about what they are saying, and I think the romanticism of the Confederate attack presented in Longstreet Attacks pushes aside the actual history and muddles the game as a whole. Playing it while reading a very thorough history of the battle at the same time made its flaws that much more apparent and made me less inclined to forgive them. Longstreet Attacks is not a failure of a game, and I am glad I played it, but I also know I will not play it again. However, I am very excited to try more Blind Swords games. I have a copy of A Greater Havoc sitting on my shelf waiting for me to find some time to try it. I believe that there is at least one Blind Swords game out there for me, but I know that Longstreet Attacks is not that game.

Longstreet Attacks by Hermann Luttmann

Few names loom larger in the, for lack of a better word, wargame-ology of current American Civil War games than Hermann Luttmann. A Most Fearful Sacrifice, his enormous game on the full battle of Gettysburg, has won countless awards and is easily among the most talked about games of 2022. Before that he was widely known for his Blind Swords system, which includes several battles from the Franco-Prussian War but is dominated by American Civil War games. Seeing as I am currently undertaking a tour of ACW designs it was inevitable that I would play a few Luttmann designs. As my entry point into the ludography of Luttmann I selected Longstreet Attacks. This wasn’t because I thought it to be the best entry into the system, many people have said it is not, but rather a choice based on the game’s subject. I wanted to play something Gettysburg to mark the 160th anniversary back in July and I thought playing a game about the second day on the 2nd of July would be appropriate. I managed to approximately time the beginning of my game with the timing of the famous attack, but the actual playing of the game took a fair bit longer than Longstreet’s disastrous assault did. I also think the figure of Longstreet and his position in the Lost Cause myth is an interesting one, and something that is very germane to my project.

Blind SwordsFor those who may not know, Blind Swords is a chit pull, regimental level tactical hex and counter game system of I would say medium complexity. Lighter than Great Battles of the American Civil War, but by not without its chrome and complexity. The core is pretty easy to grasp, but there’s enough little nuance in the rules that you may find yourself having completely forgotten some small element until after you finish playing a game – I certainly did. To my mind, there are three things that stand out in Blind Swords and that I found utterly gripping, and please bear with me, they are: the chit pull, the combat results table, and the orders system. Wargaming baby, I’m nothing if not consistent in my love of the seemingly mundane at least!

I wouldn’t say I have a ton of experience with chit pull, but I’ve certainly played other systems that use it. I’ve played a few Great Battles of the American Civil War games, with its very complex chit pull, and I’ve dabbled in some lighter games where you just dump everybody in the cup and resolve to see what order each unit activates in. I mention this because I think the chit pull in Blind Swords is the most interesting version I’ve encountered so far by a mile. It’s relatively simple (although the Vassal mods implementation of it is a bit fiddly) but also really engaging. This is due to both how it handles events and how each activation is resolved.

I’ll start with the latter first. Unlike in something like GBACW where if you pull a division, you activate every unit in that division, in Blind Swords you first have to roll a die to determine if you activate fully or have to take a limited activation and then you only pick one brigade under that commander to activate. Then you mark that brigade as having been activated and if you have brigades under that commander that still need to activate you put the chit back in the cup to draw again in the future. I really like this, it makes the back and forth much faster as you’re usually only activated between two and five units on each chit pull, not entire wings of your army. It also makes for a more interesting flow to the battle, as you never know when another brigade in that division will activate or even if they will fully activate – so how risky do you want to play? A big aggressive move earlier could see that brigade stranded without support as your opponent plans their counterattack. It keeps the tension high on each chit pull and is overall a really satisfying experience.

The events also add a lot of excellent spice to the gameplay. Each turn you will place a number of events from your side into the cup, usually some you get to pick while others are added at random from the available pool. When you pull events, some will trigger immediately while others can be held and played later. This adds a lot more variety to what can happen in each round and for the most part the events are interesting without being game breaking. What I liked even more, though, was the Fog of War event that always goes into the cup. When this is drawn you roll on a table and an event triggers for one of the players. The best of these by far is the one that lets you move an enemy unit one space. Few things are more satisfying than taking control of an enemy piece. It is not only satisfying, though, it is also a great example of the chaos of battle and how sub-optimal decisions can be made in the heat of the moment. Game systems can struggle to capture one leader making a poor decision or an error that the commander, with their wider perspective, never would but by handing control to your opponent for one move you can create that sensation of a subordinate completely screwing up. If I had to distill Blind Swords down to one inspired rule, it would be this – I love it.

I am less certain that I am in love with the combat results table, but I am certainly intrigued by it. After calculating your attack strength you roll a d66, meaning you roll two d6 one of which represents a tens and the other a ones digit, so you get a number between 11 and 66. You then consult that row of the CRT against the column for your strength and look for the cohesion rating of your target – if you hit it will be in a colored band that will tell you what table you’re opponent has to roll on to see how their unit responds to being shot at. This could have no effect, or it could be utterly disastrous. I’m honestly not convinced by the first table; I think it works but I don’t love it. My issue is less with the table and more with how central the Cohesion Rating is to many of the game’s systems and the mixed feelings I have about it – but I’ll talk more about that later in the review.

An excerpt from the first of the two CRTs. You can see the dice results on the righthand column, the columns for attack strength, and the colored boxes for target CR values. You can also see here the many, many column shifts you factor in each combat, which can be a little overwhelming at times.

The second table, though, I think I love that. The defender must now also roll two d6s, one of which will determine whether his units are Battleworn (flipped over to a weaker side) and the other (brilliantly known as the Skedaddle Table) determines whether they retreat and if so, how far. Splitting these two outcomes and having them be randomly determined separately is great, I love it. It can create interesting situations where units take a ton of punishment but refuse to give up their position, or where completely healthy units break and run but are perfectly healthy and able to be sent back into the fight. It generates a valuable diversity of outcomes to combat with only a minimum amount of rules overhead – the best of both worlds.

The table that defenders will be rolling on - this one is for ranged combat, close combat has a separate one. I love the use of Skedaddle here. If I had a critique it is with the choice to use a D for Depletion as the result that inflicts a Battleworn status. We spent most of our game saying Disordered or Disrupted instead of Battleworn because of this.

Now, let’s talk orders. I think orders in wargames are really interesting. Last year I picked The Flowers of the Forest as my favorite game I played that year, and that’s a game entirely about giving orders and then regretting them utterly. Blind Swords is not that, and in fact is quite forgiving in how it handles orders but still manages to be interesting. When you activate a brigade, you pick an order from the four options: Attack, Defend, Maneuver, or Regroup. What order you pick will determine what they can do with their activation, with no order allowing you to do everything you want. The key factors you have to balance are how far you can move, what kinds of attacks you can make, and what options you have for rallying and rebuilding injured units. While Attack and Maneuver will be by far the most frequently used in any game, the situational usefulness of the other two cannot be denied and they certainly gave me food for thought as I was planning my strategy. This system isn’t the greatest thing in wargaming, but it does strike just the right balance between complexity and generating interesting decisions and I think that is worth praising.

Before we get on to my main critique of Longstreet Attacks, I wanted to do a quick bullet list of my nitpicks with Blind Swords. These are not irredeemable flaws, but they are things that annoyed me enough that they provided a mild detriment to my truly loving what is otherwise an excellent system. My complaints are thus:

I hate calculating strength ratios. When I saw the initial combat system for Blind Swords, I was excited that it used unit strength, and then I saw that you have to calculate strength ratios to determine column shifts in close combat. I hate this.

Cohesion Rating is a cool stat, but it feels a bit too critical. CR 4 and 5 units are so much better than CR 2 ones. CR not only determines how likely you are to be hit in combat, it also can trigger column shifts in close combat and having a CR of 2 or less makes you susceptible to Panic results triggered by neighboring combats. It just feels a little too critical of a stat and that makes the variability present in some units a bit frustrating, which is something I’ll go into more below, but it was a frequent source of frustration for me.

The leader death rules are pretty underwhelming. Given the high rate of wounding and death for officers in the ACW this is now something I look for in the games I play. Leader death is a possibility from drawing the Fog of War chit, with a separate table to see who, if anyone, died. It doesn’t happen all that often, and in my game the only leader who died was replaced by a leader with the exact same activation stat. This was pretty underwhelming and basically had no impact on the game, which was disappointing. I’d like to see it trigger more often.

The games are too long. The grand campaign of Longstreet Attacks took me over a dozen hours and from what I can see this seems to be pretty standard for the system as a whole. If my opponent and I had played in person in one sitting, as opposed to over Vassal across a number of evenings, it would have gone faster but I have yet to see a Blind Swords ACW game with a full battle playable in under four hours and that’s a bit of a bummer. Don’t get me wrong, I love a long game some of the time but it’s not an every week kind of gaming experience and long games have to be really amazing to warrant me returning to them again and again.

Those are my main nit-picks. The core system is good but we’re not here to just talk about Blind Swords in the abstract. This is a review of Longstreet Attacks specifically, so what did I think of that game specifically? The short version is that while I really like Blind Swords as a system and I’m sure there is a Blind Swords game out there for me, I’m sure that that game is not Longstreet Attacks. The long version is below.

Longstreet AttacksI want to open with the fact that I think Longstreet Attacks is a fine game. I enjoyed my time playing it. If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have played it for nearly as long as I did. I found the Little Round Top scenario a little tedious, but it was also a learning scenario so that’s kind of understandable. The main campaign battle was definitely more interesting, but I also found it at times very frustrating. This was the kind of frustration where I wanted to love this game, but there were elements of it that prevented me from doing so and that drove my frustration with it. It’s a very specific kind of frustration, maybe the worst kind, and I want to try and explain why. I’m going to open with a few minor critiques of things that just didn’t work for me, but I can understand may be the result of my own personal preferences, before getting to the real meat of my problem with Longstreet Attacks: the narrative of the battle that its systems create.

While I think it seems natural to pick Little Round Top as an intro scenario with its small counter density, the terrain proved incredibly frustrating while I was playing the game and in both games (this and the grand battle) the Confederates barely launched a sustained assault due to be bogged down in the rocky terrain.

In terms of pure mechanics, the element of Longstreet Attacks that frustrated me the most was its victory conditions. Across the map are scattered various victory point hexes for one side or the other, or both, that grant VPs at the end of each turn. There are also three hexes that if the Confederacy can take them will generate an automatic victory. I’m generally not a fan of victory points in wargames and I’m really not a fan of wargames that generate points every turn for controlling a space. I need a solid justification for why controlling this hex is so important to overall victory and if it’s going to be for a number of turns, I really need to understand why controlling this hex for 20 minutes (the in-game turn length in Longstreet Attacks) matters as much as who controls it at the end of the game. Victory conditions are something I have a mild obsession with, and I don’t like ones that are too game-y. I want the terms of victory to convey something about the historical objectives of the two sides.

This gets to my other problem with Longstreet Attacks’ victory conditions, and one that I accept is derived from my own opinions on what I want to see in a historical game. The victory point hexes are scattered in a way that nudges players towards control of areas that were central to the historic battle. To put it another way, the victory conditions are set to direct players towards recreating the historical course of the assault. This means that hexes that objectively would be worthless to control in terms of overall strategic value to the battle can be worth quite a lot of points because historically that was a point of fierce fighting. This feels too artificial to me. I want the game to have victory conditions that make me understand the strategic goals of the battle, not ones that try to move me along on rails to recreate what the historical commanders did. I know for other people this won’t be as big of a problem, but this is my review and so I get to say I don’t like it.

I haven’t really brought it up in the review because I think its already widely covered elsewhere, but the game does come with this very nice Rich Barber map. If I had to be a slight heretic I would say that I found the terrain around the Round Tops to be a bit too busy and hard to read at times, but there’s no denying the map’s overall aesthetic appeal.

The victory conditions frustrated me because they felt more tedious and less interesting than I wanted, but they were not my greatest issue with Longstreet Attacks. My objection to Longstreet Attacks could arguably be oversimplified into the idea that the Union units Cohesion Ratings are too low, and the Confederates’ ratings are too high, but it’s more than that. Explaining it, however, is going to take a bit of time so I ask you please for your indulgence.

I want to talk about the narrative of Longstreet Attacks, and in examining that narrative I am only considering the emergent story that comes through via the game’s mechanisms. Not the framing that might be in the rulebook or with the scenario description, nor any designer notes. Instead, I just want to consider what version of Longstreet’s attack on the 2nd of July this game told me when I spent many hours of my life playing it. To understand why I care so much about this we need to talk a little bit about Longstreet as a man and his unusual position within the historiography of the American Civil War.

Longstreet was a general who spent almost the entire war serving under Robert E Lee. Lee affectionately called Longstreet his “Old War Horse” and he was one of the few generals who was able to complain to Lee about his strategies and openly disagree with the general. They were very close, especially after the death of “Stonewall” Jackson in May of 1863, and so you would expect Longstreet to hold a similarly hallowed position within the halls of Confederate memory as Lee and Jackson do. You would be wrong, and to understand why you need to know what Longstreet did after the war. To cut a very long story very short, Longstreet moved to Louisiana, joined the Republican party, and argued in support of other ex-Confederates joining the party and accepting Reconstruction – not out of the pure goodness of his heart, mind, he believed it necessary to dilute black involvement in politics, but still a radical approach for a man of his legacy. This put him in direct conflict with Redeemers like the KKK, the White League, and other organizations that sought to violently restore a white supremacist order to the southern United States. This came to a dramatic head in 1874 at the Battle of Liberty Place, when an armed group of white supremacists attempted to storm the Louisiana capital and depose the Reconstruction era government there. Longstreet, as an officer in the state militia, led a force of mixed-race militiamen to oppose them. Over a hundred men died, Longstreet was captured trying to negotiate with the White League, and President Grant eventually sent in Federal troops to quell the unrest. An ex-Confederate hero leading black troops against his fellow white southerners was an unforgivable sin. Former comrades in arms, including notorious Lost Cause promoter Jubal Early, denounced Longstreet and set about rewriting the annals of history to make him a scapegoat for the failures of the Confederacy. Most prominent among these was the great defeat at Gettysburg, now placed solidly at the feet of one General Longstreet.

The beginning of McLaws attack in our game. Hood has stalled out trying to take the Round Tops and Devil’s Den (he eventually took the latter but it was a very long time coming). McLaws would prove far more successful against the Union center. It may look like he is outnumbered but those Union counters don’t stand much of a chance against his attack.

The reason this is relevant for Longstreet Attacks is that there are kind of two conflicting possible narratives for what this attack means. Longstreet famously (or infamously, depending on your perspective) did not like the plan of attack on the 2nd of July 1863. He thought it risky and unlikely to work and argued strenuously with Lee for a different plan – ideally a movement of the whole army towards the Union rear to cut off their access to Washington and force them to attack the new Confederate position instead. Lee refused to consider this idea, and Longstreet was forced to go ahead with his assault. The assault ultimately failed, securing no significant ground and causing the death and wounding of hundreds of soldiers the Confederacy couldn’t afford to lose. Yes, the Union suffered casualties too, but not enough to seriously endanger the Army of the Potomac. This narrative is one where Longstreet’s attack is a doomed assault, well executed but ill-conceived from the start. Not quite so disastrous as Pickett’s Charge, but still a flawed strategy that came at enormous cost.

The alternative narrative accuses Longstreet of dragging his feet, launching his attack too late in the day and failing to really put his heart into the attack. It was doomed not because it was tactically unsound but because its commander did not believe in it and botched the operation. No surprise this was the narrative pushed by Early and other architects of the Lost Cause, and for a long time it was the dominant narrative, but it was built on a foundation of lies (often literally, such as a fictional order that Longstreet was to launch his attack at dawn. He was to ready his troops at dawn, not attack). My problem with Longstreet Attacks the game is that in many ways it feels more in line with this narrative than with the actual history, an experience that was exacerbated by my choice to read Stephen Sears’ massive history of Gettysburg at the same time I was playing Longstreet.

In Longstreet Attacks the Confederate units are just better than the Union ones. They often have higher strength, and they always have a higher cohesion rating. Unless they suffer morale penalties from combat most of the units are immune to a Panic result in combat. The smell of the notorious Confederate sentiment “one southerner could whip any ten Yankees” comes off the game in waves. One cannot deny that the Confederate generals gave the attack their all and that many units withstood stunning amounts of punishment to attack Union positions, but the defenders were no callow bunch of cowards breaking at the first sign of attack. The battle on the Union left was chaotic because General Sickles had left his position and stretched his lines too thin. Arguably the low cohesion ratings could reflect this poor position and chaotic command, except that even the units that were outside of Sickle’s Corp often have this same poor cohesion rating – it is a trait of the Union army not just those units that were in chaos. And surely that chaos could be reflected in the game’s use of Disruption morale penalties rather than baked in stats. It seems a bit egregious that often Confederate units on their reduced Battleworn side are still superior to many Union regiments – especially when cohesion rating is so crucial to determining when a hit is inflicted in combat.

My somewhat crude illustration showing the distribution of Cohesion Ratings between the two sides. The far left are units with CR 5 while the far right are those with a CR of 2. It can be hard to fully grasp the significance of this without knowing from experience how much better a CR of 4 is over a CR of 2. It also doesn’t show the strength distribution, where many of the higher CR Union units are either very low strength and/or sharpshooters, who only have a single step of strength. This is only infantry counters, artillery are mostly CR 3 on both sides.

To avoid getting too lost in the weeds let me try and distill the matter. Playing as the Union in Longstreet Attacks I did not feel like I was a general trying to fix a mistake made by my inferior officer, i.e., Sickles. I felt like a man tasked with taking green troops into combat and repeatedly frustrated by their failure to perform while my opponents stormtroopers ran roughshod over my positions. My only saving grace being the terrain and a desperate prayer for night to come soon and bring an end to the attack.

I made little progress in stemming the Confederate attack – for all its strengths Blind Swords seems like a system poorly suited to highly attrition conflict. Battleworn status can be recovered more easily if your CR is higher, like for nearly all Confederate units, and there is no permanent loss that cannot be restored in time. Confederates could push my lines back so far that the handful of units I forced to be Battleworn could end up being far enough from the front line to rebuild the next turn, undoing all my hard work. This may be a slightly more fundamental issue with Blind Swords, at least as it is in this early entry. It’s not built for sustained attrition and may not be suited to horrifically bloody engagements like the second day of Gettysburg. Perhaps it is for that reason that there are no Blind Swords games on other particularly violent engagements like Shiloh, Antietam, or the many battles of the Overland Campaign. Not every system can do everything and this may be a limitation of Blind Swords.

Near the end of our game of Longstreet Attacks. McLaws has successfully pushed back the Union center - many of those units are broken and useless in combat. Anderson is having a harder time on the Union right, while Hood’s attack on Little Round Top never really came to anything and now Law is engaging in a wildly ahistorical flanking maneuver that has placed him awkwardly in the middle of the Union activation chits. While the position is bad, this a strong Union victory as the attack went too slow to secure the VPs it needed to win.

I also saw no sign of fatigue in the Confederates as the game progressed, no indication that their losses were adding up, no indication that the assault was running out of steam and that it was asking more of its men that they could deliver. Instead, it seemed as if the only way to stop the Confederate attack was for night to come, suggesting that maybe had Longstreet attacked earlier he would have been victorious. I got no sense that maybe Longstreet would see that his attack had failed, his forces were stalling, and he had no reserves to commit, and order a withdrawal of his units. No, given infinite time these Rebels would nearly always overrun the Union army, and to me that reeks of the story of Jubal Early and his cohort discarding history to settle a personal vendetta. And it saps my ability to enjoy the game.

ConclusionIn my final assessment I did really enjoy Blind Swords as a system, but I found the emergent narrative of Longstreet Attacks somewhat poisoned my ability to love it. I was frustrated, and not in a fun way. Blind Swords is a system that really embraces the chaos of warfare and historical simulation, and that is something I love dearly. I think historical games need chaos because history is not predictable. However, I also think historical games need to be honest about what they are saying, and I think the romanticism of the Confederate attack presented in Longstreet Attacks pushes aside the actual history and muddles the game as a whole. Playing it while reading a very thorough history of the battle at the same time made its flaws that much more apparent and made me less inclined to forgive them. Longstreet Attacks is not a failure of a game, and I am glad I played it, but I also know I will not play it again. However, I am very excited to try more Blind Swords games. I have a copy of A Greater Havoc sitting on my shelf waiting for me to find some time to try it. I believe that there is at least one Blind Swords game out there for me, but I know that Longstreet Attacks is not that game.

August 15, 2023

Review - Men of Iron by Richard Berg

I have written and thought more about Richard Berg’s Men of Iron than I have any other wargame I’ve ever played. The Men of Iron tri-pack was the game that brought me fully into wargaming. It was my first hex and counter game. While not my most played game if individual plays are measured, in terms of hours invested it almost certainly is. I have a relationship with this game series is what I’m saying. When I first bought that tri-pack I didn’t have any plans to write a review of the games therein. I’ve documented many of my individual plays of certain battles and that was my plan to continue going forward – not writing up literally every play but certainly every scenario that I thought I had something to say about. However, as I play more Men of Iron, I keep thinking about what I love about the system and what frustrates me about it, and I’m increasingly tempted towards making my own version of Men of Iron. That has nudged my thoughts more in the direction of what I think is the appeal of the system and what its failings are, and at a certain point that’s basically just a review so I thought I’d put that down on a page, and once I’ve done that I might as well share them with the world.

At this outset I do want to emphasize that this is far from my final thoughts on Men of Iron. I’ve played over a dozen games, so these are far from first impressions, but I also have no plans to stop playing and many more scenarios to try, so these are more like my thoughts midway through my journey. I believe them to be sufficiently robust that they won’t change much as I play more, but if they do then I suppose I’ll have to write a new review after thirty or forty plays. With that disclaimer, let’s get this thing under way!

What is Men of Iron?For those of you who may be new here, Men of Iron is a tactical hex and counter system for medieval battles designed by legendary (and divisive) designer Richard Berg. A battle is playable in between one and four hours with most battles being in the one-to-two-hour area. It’s relatively low counter density, with no stacking, and I would say approximately mid-weight in terms of complexity. Definitely not heavy, but fiddly enough to not quite qualify as light either. There are currently four entries in the series (more on that below) with a fifth on the way from a different designer since Berg passed away a few years ago. While Men of Iron may share some qualities with other Richard Berg systems, it is also very much its own thing. Just because you like other Berg designs doesn’t mean you will like Men of Iron, and vice versa (I for one am no fan of Great Battles of the American Civil War and have not been very tempted by Great Battles of History, two flagship Berg designs). It was my entry into hex and counter wargaming, so I certainly think its suitable for that purpose, but I also wouldn’t say it is the best introduction to this side of the hobby. It’s great if medieval battles are your thing, less so if they’re not.

My first ever time playing the system, this takes me back. The little Agincourt scenario may not be my favorite, but it was a great way to learn the system.

What’s good about it?Lots! But there’s also just a lot to the system, Berg was not a man to do something halfway, and I don’t want to dedicate hundreds of words to each and every little mechanic in Men of Iron. For me, the strength of Men of Irons is greater than the sum of its parts, so I’m going to highlight a few specific elements that stand out to me as distinctly Men of Iron and particularly good. After that I will move on to the reason I think Men of Iron is great, and the reason I keep opening up its box and setting up one more scenario.

The weapon’s matrixThis is a simple chart that you consult every time one of your units attacks an enemy unit in close combat. You find which column the attacking unit is in, then trace your way down to the row with the defender, and there you will find a dice roll modifier. It’s super simple and allows for a very quick calculation of the initial parameters for every combat. You then consult the armor value printed on the target counter and you’re most of the way towards resolving your close combat. It’s really intuitive and as I’ve played more hex and counter wargames, I’ve found few systems that I like as much as this. It helps keep the counters from getting too cluttered while also allowing for an interesting diversity of units in the battles. It’s great.

Victory ConditionsI am obsessed with victory conditions from a narrative perspective, i.e., what does victory mean? I often care more about the story of victory than I do the balance. By my metric, Men of Iron’s victory condition is near perfection. When units are eliminated or retired their controlling player will incur Flight Points, which are tracked on a sheet separate to the game map. At the start of each player’s activations, you both roll a d10 and (temporarily) add it to your current Flight Point total. If the result is greater than your flight threshold for that battle, you lose. If it is less, you ignore the die roll entirely and keep playing. I love this because it combines an easy to track victory condition with an element of randomness that means you’re never sure when you’ll lose, only that you’re close to it. I also love it because it captures what the key condition to winning a medieval battle was: not being the side that ran away. The moment an army breaks and runs, it is over, and they have lost. Many factors can contribute to why they would retreat, but fundamentally the point of the battle is to make your enemy run away and Men of Iron brings that to the fore. It’s excellent.

The Infidel flight track, you can see the relative position of the two markers. This was for Antioch, and the roll has put the Crusaders over their threshold of 20 but kept the Turks below their threshold of 35, yielding a Turkish victory.

Continuous Attack!When you eliminate an enemy unit in close combat, most of the time you’re going to generate a Continue Attack result. This means that the unit in question must attack again at the end of this close combat phase, and with a penalty. This is not optional. When combined with the fact that you must advance into a vacated space in close combat, this can result in your units being way out of formation after an offensive. It can also allow for decisive and crushing attacks where one unit goes on a rampage and cleans up a series of disordered enemy archers or infantry. It can create thrills and anxiety in equal measure and it’s so far outside of your control that it can sometimes feel like rather than playing Men of Iron you’re just trying to desperately hold on while the game takes you on a rollercoaster of chaos. Some people may hate the sound of that, but to me it’s both extremely entertaining and really captures the limits on control that defined much of medieval warfare. These were not drilled and disciplined professional soldiers, and they didn’t act like it.

Robert the Bruce goes berserk, racking up a Continued Attack -2 as he carves his way through the center of the English lines at Bannockburn.

The NarrativeThis is the big one, the thing that always drags me back to Men of Iron. Men of Iron tells great stories. The combat results table is punishingly random – I’ve set up so many careful attacks only to roll a zero and disorder my own King’s unit, but I’ve also seen Robert the Bruce cut through three English units in one turn. Men of Iron is full of interesting decisions around where to position units, how to structure your attacks, what order to move units in, but once you’ve done all that the game dumps a massive helping of chaos into those plans and throws them back at you. You then have a chance, via the Continuation system, to activate another group of units but that is again dictated by the dice. This level of randomness will absolutely rub people the wrong way, but for me chaos is essential to historical wargaming. History is a fickle beast and there’s no way for one person to entirely predict or control its flow. Men of Iron is a game that asks you to make the best strategy you can and then slaps you with results and asks you to just deal with it. This can be incredibly frustrating at times, but at the end of each game I feel like I experienced something. This game tells stories and while that story might be one of disastrous failure it is still incredibly memorable.

And that’s just the core system! Each battle throws a new twist at you. New circumstances, special rules, optional rules to examine hypotheticals or alternative historical interpretations, and new units and leaders. All of these elements ensure that each time you set up Men of Iron you’re going to be telling another story and experiencing a different kind of history. While not every scenario is created equal, I’ve found all of them to at least be interesting and the truly great ones to be utterly compelling. I think it’s hard to convey how I can get so excited about pushing cardboard chits around a map and then screaming at a couple of d10s, but it really works for me. I’m totally engaged and invested in what happens in a game of Men of Iron and that is down to an amazing alchemy that the system has.

The concluding position of my most recent game of Bosworth. Henry VII made an amazing series of Continuation rolls and was able to seize the initiative and launch a very effective flanking movement, collapsing the Yorkist position and threatening their rallying position.

I’ve been trying to unpick exactly what that alchemy is, and I think it comes down to the game’s flow. Men of Iron doesn’t have strict turns, instead players will intermittently alternate activations. Your first activation, either of the game or when play passes back to you, is called a Free Activation and it lets you pick one Battle (the medieval term for what in other games would be a brigade or corps of troops under one leader) and activate it. They move and, if they are archers, conduct missile fire and then, once all movement is finished, you conduct melee combat. Once that is resolved, you can attempt to activate another Battle by rolling under that Battle’s leader’s continuation value. If you succeed, you repeat that process with that Battle, if you fail play passes to your opponent. There’s a little more to it than that, but that’s the gist. What’s great is that this can create a really uneven tempo to the game, where maybe on one turn you just activate one Battle but on another you activate three. It’s impossible to know how many activations you’ll get before your opponent can go and this creates an interesting thought process as you decide what to prioritize and what can be ignored for now. It also naturally allows the system to create big Moments, where you get a key activation you needed, or your opponent fails to capitalize on a successful round of close combats. It’s that interplay of total control (picking a free activation, deciding where to move) with total chaos (continuation, combat results) that makes Men of Iron’s magic work. It does mean that the system is somewhat susceptible to failure – a run of bad luck can spoil it – but given how many dice rolls you’ll make in a single game it will generally balance out in the aggregate.

What’s not so good?Lots, if I’m honest, but not enough to make me feel anything less than love for Men of Iron. I have many nitpicks with the system, things that hold it back from being truly amazing. I want to reemphasize that none of these complaints are enough to override what I like about Men of Iron, or to stop it from being one of my all-time favorite hex and counter systems, but they are absolutely problems with the game. My nitpicks are, ranked in approximate order of annoyance:

There are too many damn DRMs. My description of the combat matrix left out that once you’ve done those two steps there’s like a dozen more potential DRMs. A modifier for if you’re shooting into the flank of a horse unit, Richard? Really? The frustration of setting up a big attack only to roll a zero is significantly amplified if you just spent two minutes counting up DRMs on that combat. It’s too much, it should be simpler.

The rule for attacking when your unit is outnumbered is needlessly confusing. A unit is supposed to make every eligible attack they can, but also each enemy unit can only be targeted by one melee attack per combat round. In a one-on-one situation, this is fine, it makes sense. But when the defenders outnumber the attackers, things get very confusing very quickly and even after many plays, I’m still not sure I entirely understand it. I can see why Shields and Swords just went with each unit makes one attack in combat, it’s much easier to parse.

The rally mechanic kind of only serves to drag the game out without necessarily making it more exciting. When a unit suffers the Retire result, they are placed next to a standard, either for their Battle or for their overall side depending on scenario, and as a Free Activation you can rally all the Retired units. While they are Retired, they each count one point towards your side’s Flight total. The problem is that bringing Retired units back into the fight is so slow – they are all Disordered and usually far from the front lines plus you’ve spent an entire activation just un-Retiring them. In my experience using the Rally action rarely changes the outcome of a battle but it absolutely can make the game longer, and that’s a real bummer. Nobody wants a game to overstay it’s welcome and the Rally mechanic risks causing a game to overstay its welcome.

Archery is too damn powerful. I’ve written about this extensively in other pieces, so I won’t repeat myself here, but archery is just too strong and as a guy who wrote a whole book on the crossbow this annoys me.

Terrain is often secondary in the scenarios. This isn’t true of every battle, but in many of them the terrain is confined to the borders of where the action will take place, or there’s only a handful of terrain hexes to consider. Woods and hills weren’t invented in the modern era and medieval battles were not just fought on flat, open plains. I want to see more terrain in my battles.

The Antioch scenario has some lovely art on the map, but that camp is completely inaccessible and the entire battle is pretty much completely fought in the open plain.

Continuation just doesn’t quite work. When Continuation fires it’s amazing, but, in most battles, it is just too unlikely. I had a game where my opponent and I swapped about a dozen activations without either of us making a single Continuation roll. This becomes a big problem in battles where you have a lot of Battles (how’s that for a sentence). Often it makes more sense to keep activating one or, at most, two Battles over and over again than it does to risk activating a Battle near the rear of your lines and hope for a Continuation to allow you to push the offensive elsewhere. I think that Continuation would have benefited from being more likely in the first instance and then suffering a much steeper decline in likelihood (by default most leaders have a Continuation rating of 2-4 and each successful Continuation inflicts a cumulative -1 penalty on all subsequent ones). While I like that Men of Iron embraces randomness, I think the balance on Continuation is kind of off and it can create some very weird game experiences as some Battles just sit in the rear and never move because it’s not worth it to risk activating them first and you never succeed on a Continuation with them. In a scenario where you only have 2-3 Battles per side this is usually less of a problem, but in the huge scenarios with 4+ Battles you can end up just not activating units for the entire game and producing these really wonky looking formations and weird narratives. I do want to reiterate that I like the Continuation system, I just think that it could use a little more development to help it truly sing.

What’s the best one?Well hypothetical straw-man version of myself, what a loaded question. They’re obviously all great, but I know that when you have a system with four published games there is a need to rank them. I won’t be doing that. However, I will meet you halfway, fictional self, and provide a brief rundown of my thoughts on each volume (so far).

Men of IronThe original flavor covers battles from the late-13th through the 14th and into the early-15th century (if you have the tri-pack, which includes the Agincourt scenario originally published in C3i Magazine). Of the topics covered by Men of Iron games, this is the one closest to my heart. That’s why it pains me to say that this is probably the worst entry in the series. The battles lean towards one side holding a static formation while the other player attacks them, which largely reflects the historical combat of the period but can get a bit boring by the third or fourth time you experience it. Archery is also at its most overpowered in this entry and the scenario design as a whole is just not great. It’s not bad, but it’s also not great. There are a few standout battles, like Bannockburn, that are truly phenomenal but there are also battles like Falkirk that are a bit boring. Overall, a mixed bag.

InfidelThe second entry in the series covers the battles of the Crusades. There are more large-scale battles, with maps that cover twice as much space as those in Men of Iron original flavor. The big change here is the abundance of horse archers and the extreme asymmetry they bring to the two sides. Archery has also been toned down some, which is nice. Overall, I think Infidel is a better game than original Men of Iron, but I’m also not sure if I like it more. The scenario design is more interesting, but I find the many, many horse archers to be a bit tedious at times. Riding in wave after wave of mounted troops, shooting, and then running away is just really annoying – both as the person on the receiving end and as the one resolving it. To be fair, this tactic was incredibly irritating on purpose and so in that way the game kind of reflects history – it was in part intended to provoke a break in the Crusader’s ranks. That said, I don’t know how much I enjoy doing it as a player of a game. I think my fondness for the fourteenth-century battles of original Men of Iron means that I slightly prefer that entry even if Infidel is a better game.

The enormous Arsuf scenario from Infidel (apologies for the glare, my lighting set up wasn’t great here). Infidel has several scenarios of this scale, which allows for the greater mobility of the Muslim horse archers to shine (and annoy).

Blood & RosesMen of Iron does the Wars of the Roses! I’m honestly not very interested in the Wars of the Roses; they just don’t do anything for me. I’m not sure why. This is too bad because Blood & Roses is a clear improvement to the system. It introduces Army Activations, that let you move but not fight with your whole army and thus help to fix the problem of totally neglecting some of your Battles for an entire scenario. It also has an improved CRT that introduces a Disorder or Retreat result – something that makes close formations less punishing (in previous entries being forced to Retreat could instantly eliminate a unit and so you had to unrealistically spread out your units) and allows players a bit more choice in how to respond to a combat result. Also, the archery table is great – longbows shoot super far but are way less effective. Mechanically this is the best entry in the tri-pack, but my ambivalence towards the Wars of the Roses makes it harder for me to get very excited about any of the battles no matter how well designed they may be.

ArquebusArquebus brings Men of Iron to the Italian Wars of the late-15th and early-16th centuries and is the only entry (so far) not in the tri-pack. This expands upon the developments of Blood & Roses and adds systems for units being trapped in melee engagements. It also introduces combined melee/ranged units with the early development of pike and shot tactics. I think this might be my favorite entry in Men of Iron. I’m fascinated by the Italian Wars and the gradual change in tactics that happened over the decades the conflict lasted. So already it’s a bump up above Blood & Roses there. It also has some truly excellent scenario design, particularly Fornovo, which is probably the single best scenario I’ve played. I can really see the refinement that went into the system for its fourth entry. I do have some reservations, though. So far, I’ve mostly only played the small and medium sized scenarios. I think Men of Iron struggles with larger battles, for the reasons I outlined above, and Arquebus has the biggest battles of any entry. Until I’ve played all these huge battles I won’t know if my fears are justified, but it is a small reservation I have.

Look at that river! Who wouldn’t want to desperately try and march an army across it? This is such a great scenario!

ConclusionMen of Iron is a system that is defined by an agony of choice. You always have more you want to do than you can reasonably expect to achieve. You want to activate every Battle in your army, but you almost certainly won’t be able to, so who do you prioritize? When picking enemy targets, who do you go for first? Should you push more aggressively or try and make some space so some of your units can recover from being Disordered? Each moment is filled with tension, and I find every play of Men of Iron to be an exciting and engaging narrative. It also has an addictive gambling quality, because of that one time you will successfully make all those Continuation rolls and achieve all your hopes, but that will be such a rare event you’ll continue chasing it like an addict at a slot machine. For all of its Berg-ian excess and systems that just don’t quite work, I love it to pieces, and I will continue to play it for years to come. Do I recommend it? I don’t know honestly – I love it, but you may not. Decide for yourself, I’ve got another scenario to set up.

July 26, 2023

Review - Jeff Davis by Ben Madison

Cards on the table: I went into Jeff Davis already disliking the subject but still hoping to experience an interesting design within a distasteful shell. What I ultimately found was a universally terrible experience. Jeff Davis a game with what seems to me to contain no redeeming value. It is filled with bad history and an underwhelming and boring play experience. I want to put this up front to make this clear – I do not like Jeff Davis, both the person and the game. That does not mean that you have to dislike it, although I struggle to see how someone could find a positive in this mess, but if you read on any further I expect that you do so because you are interested in why I hold these views and what I see in Jeff Davis that I find so repulsive. Please do not read this with the hope of seeking validation for your own positive opinions of the game nor to simply make a bullet list of all the ways you think I am wrong. Save us both some time and go do something else with your day.

I played Jeff Davis multiple times, pulling levers and trying various strategies to see what the game contained. This is not an opinion arrived at simply by looking at the game’s concept (objectionable as it is), but rather an informed opinion based on spending far too many hours with this mediocre trash of a game. For the record, not that it matters, I did manage to “win” the game once.

The GameBefore we get to the subject matter and how I think Jeff Davis falls short in portraying the American Civil War while still supposedly attempting to tackle historical hard truths, I thought it would be worthwhile to consider the game itself.

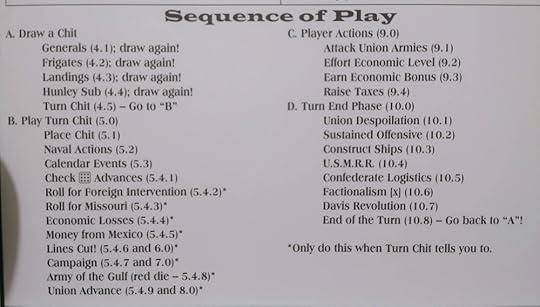

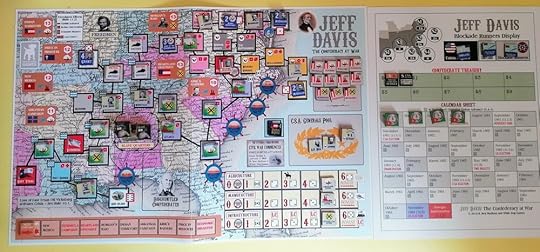

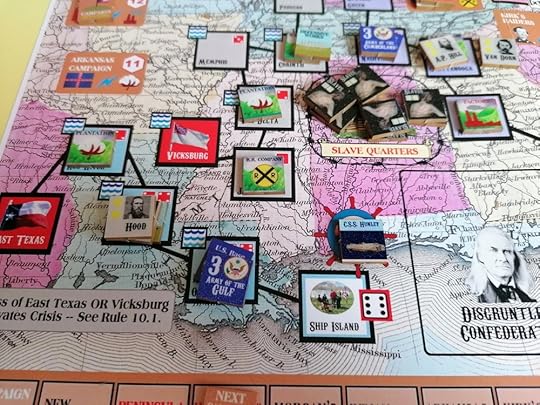

Jeff Davis is a variant of the States of Siege game system, first designed by Darin Leviloff and published by Victory Point Games. These games vary in their topics, but all share a few core mechanisms. The game map is split across several tracks converging on one central point. Enemy forces advance along these tracks and the player must hold them off until the game ends. Each turn starts with the drawing of a card or chit that tells you which tracks advance and then if any events or other special rules come into play this turn. The player is then usually given a chance to respond to these events by rolling dice to try and push back enemy units or to manage a variety of resource or political tracks. For a review of a more traditional example of the form, I would point you to my coverage of Worthington’s reprint of Malta Besieged.