Lona Manning's Blog, page 8

January 10, 2024

CMP#168 "Clouds of Mystery"

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

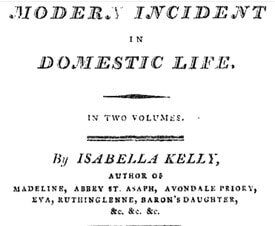

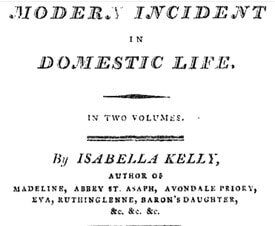

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#168 A Modern Incident in Domestic Life (1803) by Isabella Kelly

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#168 A Modern Incident in Domestic Life (1803) by Isabella Kelly

Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland, engrossed in a mysterious gothic When I finished Volume One of A Modern Incident, I was half-way through the novel and I still had absolutely no idea what was going on. No idea. So far we just had:

Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland, engrossed in a mysterious gothic When I finished Volume One of A Modern Incident, I was half-way through the novel and I still had absolutely no idea what was going on. No idea. So far we just had:Page after page of characters stammering out incoherent remarks (dashes and dots in the original):“Thy looks! –I feel them, --they will d---n me yet!”)“I cannot pray! –I will not—no—Hell is but reprobation—that is mine already—or will be soon --- ---- ---- --- --- Yet, --but him [Mr. Winstanley, that is] I now hate—I know him,--he knows not me,---no, nor my deeds.—One effort yet, to cool this burning fever, to ease this secret torture, --this---this—Oh, Mortimore! –Mortimore!—Thee!—this—and if I fail! –be they blasted in all hope, --and I!—dark perdition cover me for ever—ever--!”“Why Mrs. Courtney uttered such a frantic shriek, or what caused such violent emotion, the reader is left to imagine…” Page after page of characters harboring a secret:“the secrets of another are not my own.”"I have already told you... that I never mean to marry." And characters turning pale and rushing from the room: "With these incoherent and inexplicable words, he rushed with frantic impetuousity from their presence.” Perhaps a gothic novel aficionado would be familiar with the tropes and plot devices that baffled me and would figure out the Big Secret before it was revealed in the penultimate chapter, but I only persisted with the book because it was a quick read; a two-volume novel which had not been reviewed when it came out.

And holy snapping turtles, this had some lurid stuff; at least, lurid compared to the decorous voice of Jane Austen. This has several same-sex teases, and an incest tease, and a ghost-who-turns-out-to-be not a ghost, adultery and seduction, along with forged letters and other skullduggery. Get your smelling salts out for this one. The book got me thinking about Emma, in which the reader is kept in the dark about the Frank Churchill/Jane Fairfax romance until the end. When you get to the revelation in Emma, you realize that there were a lot of clues that you missed: Frank’s abrupt decision to go to London, supposedly to get his hair cut, Jane’s insistence on picking up her own letters at the post office, the way Frank encouraged Emma to think that Jane and Mr. Dixon were attracted to each other… Can this be said of A Modern Incident as well--can the reader keep track of the hints that are dropped?

Let's meet our main characters: a brother and sister team, Frederick and Ellen Mortimore. Frederick is empathetic, gentle, rational, and introverted and Ellen is ardent, impulsive, intelligent, and accomplished. They should arouse our sympathies because they have fallen on hard times, but it was challenging for me to stay engaged when their motivations were withheld by the author, and through various hints we learn that they are not who they claim to be. “I have no patience,--I cannot bear it!” repeated Mortimore, with an energy of voice and manner which made even Ellen’s spirit shrink, “do you forgot who and what you are?”

“No!” cried Ellen, and her colour deepened to crimson, “nor do, nor can I forget who and what you are either!” “She is not my sister.” [Frederick tells Mrs. Winstanley.}

“And you love her?”

“Dearly love her.”

“You prefer her to all her sex?”

“Not entirely.”

“NO! –well, one bed, I suspect has served you both before now?”

“To be candid, one bed served us long.”

"Farewell! Wed not! Remember Ceceline!" “Try to love you!” repeated Mortimore, with irrepressible emotion….“Still!” he repeated, his eyes wild, yet fixed with strange and piercing meaning on [Mrs. Winstanley]. She was dull,--she understood not the silent intellligence.” (Join the club, sister).

"Farewell! Wed not! Remember Ceceline!" “Try to love you!” repeated Mortimore, with irrepressible emotion….“Still!” he repeated, his eyes wild, yet fixed with strange and piercing meaning on [Mrs. Winstanley]. She was dull,--she understood not the silent intellligence.” (Join the club, sister).

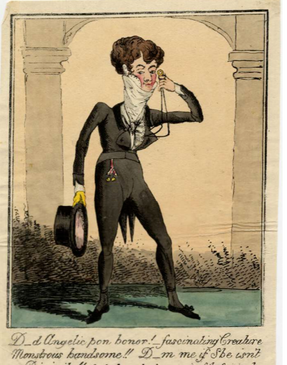

Balm? Sorry, you're on your own The other main character, Mr. Winstanley, “an Englishman of family and high connexions.. [who is] allowed to be the most handsome, sensible, and accomplished man in the Island” also didn’t arouse my sympathy because he was a selfish philanderer. He asks Frederick to tell his pregnant and discarded mistress Annette, that he (Mr. Winstanley) is going to marry a rich widow. Frederick “poured the balm of consolation on [Annette’s] wounded heart” and inspired her to renounce her life of sin. Her baby is born dead, and she disappears from the narrative. If all that's not enough, Mr. Winstanley is a plantation-owner (the story is set in Barbados) as is the kindly older mentor female figure, Mrs. Courtney. More on that later.

Balm? Sorry, you're on your own The other main character, Mr. Winstanley, “an Englishman of family and high connexions.. [who is] allowed to be the most handsome, sensible, and accomplished man in the Island” also didn’t arouse my sympathy because he was a selfish philanderer. He asks Frederick to tell his pregnant and discarded mistress Annette, that he (Mr. Winstanley) is going to marry a rich widow. Frederick “poured the balm of consolation on [Annette’s] wounded heart” and inspired her to renounce her life of sin. Her baby is born dead, and she disappears from the narrative. If all that's not enough, Mr. Winstanley is a plantation-owner (the story is set in Barbados) as is the kindly older mentor female figure, Mrs. Courtney. More on that later.Do I care that Winstanley is harboring a guilty secret? “Distraction!” he shrieked. “I am –I am undone! “…………….bear thy beloved image where passion can no more………. The virtues lingering in thy bosom…..” and “They are dead! –perished” cried he, starting, “I am not human! –What can I do? –Retreat! –Perdition! –What then? –Oh, thought! thought! thought! split not my burning brain!”

How could this book get worse? That’s right, poetry. There’s some poetry. And a ghost. Spoilers from here on:

I’m introducing the spoilers early, to avoid going through the plot of the book twice: Mr. Winstanley changed his name from Fitzalvan when he left England with his mistress, erroneously thinking that his wife was in love with another. He abandoned Ceceline and his children without a word and he changed his name. The young man Frederick Mortimore turns out to be Ceceline in disguise, and Ellen Mortimore is really his son Arthur. They cross-dress throughout the story, so the author can give us scenes like the lovely young Antonia Courtney declaring her love for Ellen:

Image generated by Bing AI “I cannot leave you!” cried Antonia. “Dear, dear Ellen can you leave me! –what will you do?”

Image generated by Bing AI “I cannot leave you!” cried Antonia. “Dear, dear Ellen can you leave me! –what will you do?”“I shall run wild—distracted!”

“Run wild!” repeated she, “let us run any where, so as it is together.—to leave me now, now when I have learned to love you, learned to be almost like you—”

“In pity say no more, Antonia,” interrupted Ellen, her cheeks in a conscious glow, “I cannot bear it.”

“Promise me then to stay with me,” [Antonia pleads, asking Ellen not to take a governess job she’s been offered, fearing that her employer will fall in love with her], you will marry him, and then—”

“Marry him!” cried Ellen, interrupting her, “no, Antonia, I will never marry anyone that would divide me from you,--do not fear,--do not think it.” The revelation that Frederick Mortimore is Winstanley's wronged wife explains this once-incomprehensible speech: “Oh, this, indeed, is insupportable,” cried [Mortimore], staggering against the wall, as he entered the house, “to see it! –hear it! –what, in my very sight! – Oh, Annette, Annette, little do you know –who—Distraction!—What is this?—I cannot bear it!”

Later, Mr. Winstanley is deathly ill and the doctor declares the only possible cure is for somebody to use their human body heat to snuggle in bed with him all night and break his fever. Winstanley’s new wife refuses to do it, his mistress Harriet refuses to do it, so Frederick volunteers to do it. He sends everyone out of the room, then: “He hastily undressed and stepped into the bed, raising his eyes to Heaven… He clasped Winstanley in his arms, and folded him to his throbbing breast….”

We have Mr. Winstanley trying to proposition Ellen, unaware that he’s hitting on his own son. We have his mistress Harriet making a play for Frederick, unaware that it’s her old best friend Ceceline who she betrayed.

"Frederick" finds "Ceceline's" wedding ring. Bing AI generated image. What makes all these teasers acceptable is that it’s all a morality play, it’s all a don’t try this at home, kids. Or this, either. Or things like this. Don't worry, Antonia has really fallen in love with a man and Frederick is the long-lost,

heroically forbearing,

loyal wife of Winstanley. The author injects a sermonette: “Turn, youth!—turn, innocence, and view the picture!—and should your unwary feet, unguided by prudence, unsupported by rectitude, have taken one little step towards error, look back, and, oh. Retreat! –Consider, dishonour is the wreck of peace,--the blight of every hope,--the canker of every joy;--like a malign fiend it pursues through every path in lie,--it goads on to the very bed of death itself—and even there forsakes not, for it survives the grave.”

"Frederick" finds "Ceceline's" wedding ring. Bing AI generated image. What makes all these teasers acceptable is that it’s all a morality play, it’s all a don’t try this at home, kids. Or this, either. Or things like this. Don't worry, Antonia has really fallen in love with a man and Frederick is the long-lost,

heroically forbearing,

loyal wife of Winstanley. The author injects a sermonette: “Turn, youth!—turn, innocence, and view the picture!—and should your unwary feet, unguided by prudence, unsupported by rectitude, have taken one little step towards error, look back, and, oh. Retreat! –Consider, dishonour is the wreck of peace,--the blight of every hope,--the canker of every joy;--like a malign fiend it pursues through every path in lie,--it goads on to the very bed of death itself—and even there forsakes not, for it survives the grave.”Mr. Winstanley survives the fever, thanks to Ceceline, but she catches it and her true identity is unmasked on her death bed with more incoherent stammering; “Oh, mourn not me! –look—your son, as Ellen, he sustained—watched his mother! –Now—now—my latest—only love, I die—dying for you! –Oh, happy—happy!—Your children--- --- my --- --- --- --- --- my god! –my Fitzavern!”

Ceceline’s death is fatal for her husband: “He made one essay to speak, but this lips only moved, and the words choaked him! He raised Ceceline’s head to his bosom—folded the cold corse within his arms—and with one—only one groan—it was his last—he sunk—he was gone—he never breathed again—and Fitzavern was with Ceceline!!! ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ I might have missed it, but I saw no reason why Ceceline and her son had to conceal themselves under clouds of mystery, or why doing so did anything to resolve their problems rather than complicate them. Once Ceceline received a convenient inheritance of fifty thousand pounds from the convenient death of her uncle, she could have shipped herself off to Barbardos and accused her husband of bigamy. Then it would have come out that Harriet, who called herself Mrs. Winstanley, was not legally married to him.

Mr. Winstanley did become a bigamist when he married the rich widow. But instead of going to the minister and preventing this crime from occurring, Ceceline dressed herself up as a ghost (as one does) and appeared before him, futilely warning him not to marry.

The marriage didn’t prosper anyway, because the rich widow’s: “long unrestrained passions, voluptuous living, and high pampered appetites, had left her vitiated mind only fit for the vilest gratifications; and as they ill suited the natural delicacy of Winstanley’s taste,” she paid for a gigolo.

So really, in this novel, people do senseless things and it turns out they accomplish nothing. Except for the deceitful mistress Harriet, I suppose. She succeeded in luring Winstanley/Fitzavern away from Ceceline by forging a letter. She comes to a miserable end, though, we are told.

Gothic titillation and confusing clues. Imagine generated by Bing AI. Catching all the clues

Gothic titillation and confusing clues. Imagine generated by Bing AI. Catching all the cluesI wonder if the young ladies poring over this tale had any notion what “the vilest gratifications” and the "degrading passions" of the rich widow might be. Or how did they interpret "irresistible nature" and "broke forth" in this passage: "The young and interesting Antonia hanging with easy, innocent fondness on his bosom… proved too much for the high and ardent spirits of…. Arthur Fitzavern; --nature, irresistible nature broke forth, and without either motion or speech betraying, Mrs. Courtney penetrated the secret.”

Hopefully the female readers spent more time pondering the double standard the author upholds between male and female conduct. But more than that, I wonder: did the early readers of this book recollect every previously-inexplicable detail that had gone before the Big Reveal, and did they say to themselves, aha, so when Frederick/Ceceline turned pale and rushed away when Harriet Winstanley arrived at Mrs. Courtney’s, it’s because she recognized her old-backstabbing friend. Or, did they turn back to volume one to re-skim all those passages which made no sense before?

Jane Austen is not the first to string clues and hints throughout her tale, but we can read and re-read Emma with pleasure, finding some new nuance to savor every time. Austen can withhold information from us and still create a coherent and interesting story that doesn't rely on salacious details to keep us turning the pages. Content warning: this section reproduces callous references to enslaved people

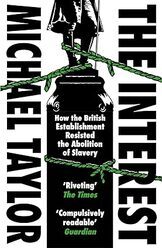

The other aspect of this book which might be of interest is the matter-of-fact portrayal of enslavement in Barbados. No amount of academic detachment is going to prepare you for certain words strung together in a certain way, such as: Mrs. Courtney’s “slaves were numerous, and it was her pleasure to let them live happily. Her plantations were extensive, and they not only sheltered and supplied the sable inhabitants in her service, but also gave employment and independence to many Europeans and their families.”

As well it's jarring, to say the least, to see Winstanley, a plantation-owner, speak blithely to the rich widow about love, slaves and chains:

“Thou art a dear provoking wretch, Winstanley,” [says the widow flirtatiously]

“I would provoke you,” kissing her hand, “to make me a willing slave for life. –How I should glory in my chains!”

“They shall hang easy on you,” cried the lady, “do not fear them—”

“Fear them!” interrupted he, “I die,--I languish for them!”

These passages, and others, tell us that although abolition had been hotly debated, you could still encounter a variety of opinions in the novels of the day, from vehement abolitionism to casual acceptance of enslavement. Whichever side you were on, there was no need to use veiled allusions.

About the author:

About the author:Isabella Kelly (1759–1857) was a prolific authoress, chiefly of Gothic novels, who supported her children after her two marriages did not prosper. She lived in poverty most of her life. She lived to the age of 98, calling herself the last surviving novelist of her era. In A Modern Incident, she worked in some lavish praise of the successful author Matthew “Monk” Lewis, “one whose nature reflects honour on the human kind,” because he had been helping one of her sons find work. James Fordyce, of Fordyce’s Sermons, was her uncle.

Scholar Yael Shapiro points out that Kelly focused on marital troubles in her novels, as opposed to ending her books with weddings: “Where [Gothic best-seller Ann] Radcliffe sets up a sharp dichotomy between good and bad marriages, Kelly’s novels seem to accept men’s controlling behavior as a possible part of any marriage.”

Rachel Feder, in a new book about Jane Austen and cultural tropes (of which much more in future) points out “Gothic novels… simultaneously offered an escape from and a commentary on the real world, which has always been dangerous for women [the real world, that is]. [T]hese stories were often subversive but not particularly progressive.”

That's certainly my take on A Modern Incident." We have some subversive fun with some same-sex and incest teases, (if that's your idea of fun), then the author winds up her tale with more double-standard morality: “Let the sons of pleasure and indulgence, should any such ever turn this melancholy page, learn from the fate of Fitzavern, that if they do not restrain the irregularity of wild desires when they ought, they may not be able to do it when they would.--but that consequences come with ruin, and with despair.

“And let the daughters of pain and disappointment, when dropping a tear to the sorrows, and the memory of Ceceline, not suppose such sorrows were in vain;--they purified her for a society of angels, and purchased her an early immortality.” Shapira, Yael. “Beyond the Radcliffe Formula: Isabella Kelly and the Gothic Troubles of the Married Heroine.” Women's Writing: the Elizabethan to Victorian Period, vol. 26, no. 3, 2019, pp. 245–63.

Previous post: Innocent Ellen, a gothic heroine

Published on January 10, 2024 00:00

CMP# A Modern Incident in Domestic Life

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#168 A Modern Incident in Domestic Life (1803) by Isabella Kelly

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#168 A Modern Incident in Domestic Life (1803) by Isabella Kelly

Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland, engrossed in a mysterious gothic When I finished Volume One of A Modern Incident, I was half-way through the novel and I still had absolutely no idea what was going on. No idea. So far we just had:

Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland, engrossed in a mysterious gothic When I finished Volume One of A Modern Incident, I was half-way through the novel and I still had absolutely no idea what was going on. No idea. So far we just had:Page after page of characters stammering out incoherent remarks (dashes and dots in the original):“Thy looks! –I feel them, --they will d---n me yet!”)“I cannot pray! –I will not—no—Hell is but reprobation—that is mine already—or will be soon --- ---- ---- --- --- Yet, --but him [Mr. Winstanley, that is] I now hate—I know him,--he knows not me,---no, nor my deeds.—One effort yet, to cool this burning fever, to ease this secret torture, --this---this—Oh, Mortimore! –Mortimore!—Thee!—this—and if I fail! –be they blasted in all hope, --and I!—dark perdition cover me for ever—ever--!”“Why Mrs. Courtney uttered such a frantic shriek, or what caused such violent emotion, the reader is left to imagine…” Page after page of characters harboring a secret:“the secrets of another are not my own.”"I have already told you... that I never mean to marry." And characters turning pale and rushing from the room: "With these incoherent and inexplicable words, he rushed with frantic impetuousity from their presence.” Perhaps a gothic novel aficionado would be familiar with the tropes and plot devices that baffled me and would figure out the Big Secret before it was revealed in the penultimate chapter, but I only persisted with the book because it was a quick read; a two-volume novel which had not been reviewed when it came out.

And holy snapping turtles, this had some lurid stuff; at least, lurid compared to the decorous voice of Jane Austen. This has several same-sex teases, and an incest tease, and a ghost-who-turns-out-to-be not a ghost, adultery and seduction, along with forged letters and other skullduggery. Get your smelling salts out for this one. The book got me thinking about Emma, in which the reader is kept in the dark about the Frank Churchill/Jane Fairfax romance until the end. When you get to the revelation in Emma, you realize that there were a lot of clues that you missed: Frank’s abrupt decision to go to London, supposedly to get his hair cut, Jane’s insistence on picking up her own letters at the post office, the way Frank encouraged Emma to think that Jane and Mr. Dixon were attracted to each other… Can this be said of A Modern Incident as well--can the reader keep track of the hints that are dropped?

Let's meet our main characters: a brother and sister team, Frederick and Ellen Mortimore. Frederick is empathetic, gentle, rational, and introverted and Ellen is ardent, impulsive, intelligent, and accomplished. They should arouse our sympathies because they have fallen on hard times, but it was challenging for me to stay engaged when their motivations were withheld by the author, and through various hints we learn that they are not who they claim to be. “I have no patience,--I cannot bear it!” repeated Mortimore, with an energy of voice and manner which made even Ellen’s spirit shrink, “do you forgot who and what you are?”

“No!” cried Ellen, and her colour deepened to crimson, “nor do, nor can I forget who and what you are either!” “She is not my sister.” [Frederick tells Mrs. Winstanley.}

“And you love her?”

“Dearly love her.”

“You prefer her to all her sex?”

“Not entirely.”

“NO! –well, one bed, I suspect has served you both before now?”

“To be candid, one bed served us long.”

"Farewell! Wed not! Remember Ceceline!" “Try to love you!” repeated Mortimore, with irrepressible emotion….“Still!” he repeated, his eyes wild, yet fixed with strange and piercing meaning on [Mrs. Winstanley]. She was dull,--she understood not the silent intellligence.” (Join the club, sister).

"Farewell! Wed not! Remember Ceceline!" “Try to love you!” repeated Mortimore, with irrepressible emotion….“Still!” he repeated, his eyes wild, yet fixed with strange and piercing meaning on [Mrs. Winstanley]. She was dull,--she understood not the silent intellligence.” (Join the club, sister).

Balm? Sorry, you're on your own The other main character, Mr. Winstanley, “an Englishman of family and high connexions.. [who is] allowed to be the most handsome, sensible, and accomplished man in the Island” also didn’t arouse my sympathy because he was a selfish philanderer. He asks Frederick to tell his pregnant and discarded mistress Annette, that he (Mr. Winstanley) is going to marry a rich widow. Frederick “poured the balm of consolation on [Annette’s] wounded heart” and inspired her to renounce her life of sin. Her baby is born dead, and she disappears from the narrative. If all that's not enough, Mr. Winstanley is a plantation-owner (the story is set in Barbados) as is the kindly older mentor female figure, Mrs. Courtney. More on that later.

Balm? Sorry, you're on your own The other main character, Mr. Winstanley, “an Englishman of family and high connexions.. [who is] allowed to be the most handsome, sensible, and accomplished man in the Island” also didn’t arouse my sympathy because he was a selfish philanderer. He asks Frederick to tell his pregnant and discarded mistress Annette, that he (Mr. Winstanley) is going to marry a rich widow. Frederick “poured the balm of consolation on [Annette’s] wounded heart” and inspired her to renounce her life of sin. Her baby is born dead, and she disappears from the narrative. If all that's not enough, Mr. Winstanley is a plantation-owner (the story is set in Barbados) as is the kindly older mentor female figure, Mrs. Courtney. More on that later.Do I care that Winstanley is harboring a guilty secret? “Distraction!” he shrieked. “I am –I am undone! “…………….bear thy beloved image where passion can no more………. The virtues lingering in thy bosom…..” and “They are dead! –perished” cried he, starting, “I am not human! –What can I do? –Retreat! –Perdition! –What then? –Oh, thought! thought! thought! split not my burning brain!”

How could this book get worse? That’s right, poetry. There’s some poetry. And a ghost. Spoilers from here on:

I’m introducing the spoilers early, to avoid going through the plot of the book twice: Mr. Winstanley changed his name from Fitzalvan when he left England with his mistress, erroneously thinking that his wife was in love with another. He abandoned Ceceline and his children without a word and he changed his name. The young man Frederick Mortimore turns out to be Ceceline in disguise, and Ellen Mortimore is really his son Arthur. They cross-dress throughout the story, so the author can give us scenes like the lovely young Antonia Courtney declaring her love for Ellen:

Image generated by Bing AI “I cannot leave you!” cried Antonia. “Dear, dear Ellen can you leave me! –what will you do?”

Image generated by Bing AI “I cannot leave you!” cried Antonia. “Dear, dear Ellen can you leave me! –what will you do?”“I shall run wild—distracted!”

“Run wild!” repeated she, “let us run any where, so as it is together.—to leave me now, now when I have learned to love you, learned to be almost like you—”

“In pity say no more, Antonia,” interrupted Ellen, her cheeks in a conscious glow, “I cannot bear it.”

“Promise me then to stay with me,” [Antonia pleads, asking Ellen not to take a governess job she’s been offered, fearing that her employer will fall in love with her], you will marry him, and then—”

“Marry him!” cried Ellen, interrupting her, “no, Antonia, I will never marry anyone that would divide me from you,--do not fear,--do not think it.” The revelation that Frederick Mortimore is Winstanley's wronged wife explains this once-incomprehensible speech: “Oh, this, indeed, is insupportable,” cried [Mortimore], staggering against the wall, as he entered the house, “to see it! –hear it! –what, in my very sight! – Oh, Annette, Annette, little do you know –who—Distraction!—What is this?—I cannot bear it!”

Later, Mr. Winstanley is deathly ill and the doctor declares the only possible cure is for somebody to use their human body heat to snuggle in bed with him all night and break his fever. Winstanley’s new wife refuses to do it, his mistress Harriet refuses to do it, so Frederick volunteers to do it. He sends everyone out of the room, then: “He hastily undressed and stepped into the bed, raising his eyes to Heaven… He clasped Winstanley in his arms, and folded him to his throbbing breast….”

We have Mr. Winstanley trying to proposition Ellen, unaware that he’s hitting on his own son. We have his mistress Harriet making a play for Frederick, unaware that it’s her old best friend Ceceline who she betrayed.

"Frederick" finds "Ceceline's" wedding ring. Bing AI generated image. What makes all these teasers acceptable is that it’s all a morality play, it’s all a don’t try this at home, kids. Or this, either. Or things like this. Don't worry, Antonia has really fallen in love with a man and Frederick is the long-lost,

heroically forbearing,

loyal wife of Winstanley. The author injects a sermonette: “Turn, youth!—turn, innocence, and view the picture!—and should your unwary feet, unguided by prudence, unsupported by rectitude, have taken one little step towards error, look back, and, oh. Retreat! –Consider, dishonour is the wreck of peace,--the blight of every hope,--the canker of every joy;--like a malign fiend it pursues through every path in lie,--it goads on to the very bed of death itself—and even there forsakes not, for it survives the grave.”

"Frederick" finds "Ceceline's" wedding ring. Bing AI generated image. What makes all these teasers acceptable is that it’s all a morality play, it’s all a don’t try this at home, kids. Or this, either. Or things like this. Don't worry, Antonia has really fallen in love with a man and Frederick is the long-lost,

heroically forbearing,

loyal wife of Winstanley. The author injects a sermonette: “Turn, youth!—turn, innocence, and view the picture!—and should your unwary feet, unguided by prudence, unsupported by rectitude, have taken one little step towards error, look back, and, oh. Retreat! –Consider, dishonour is the wreck of peace,--the blight of every hope,--the canker of every joy;--like a malign fiend it pursues through every path in lie,--it goads on to the very bed of death itself—and even there forsakes not, for it survives the grave.”Mr. Winstanley survives the fever, thanks to Ceceline, but she catches it and her true identity is unmasked on her death bed with more incoherent stammering; “Oh, mourn not me! –look—your son, as Ellen, he sustained—watched his mother! –Now—now—my latest—only love, I die—dying for you! –Oh, happy—happy!—Your children--- --- my --- --- --- --- --- my god! –my Fitzavern!”

Ceceline’s death is fatal for her husband: “He made one essay to speak, but this lips only moved, and the words choaked him! He raised Ceceline’s head to his bosom—folded the cold corse within his arms—and with one—only one groan—it was his last—he sunk—he was gone—he never breathed again—and Fitzavern was with Ceceline!!! ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ I might have missed it, but I saw no reason why Ceceline and her son had to conceal themselves under clouds of mystery, or why doing so did anything to resolve their problems rather than complicate them. Once Ceceline received a convenient inheritance of fifty thousand pounds from the convenient death of her uncle, she could have shipped herself off to Barbardos and accused her husband of bigamy. Then it would have come out that Harriet, who called herself Mrs. Winstanley, was not legally married to him.

Mr. Winstanley did become a bigamist when he married the rich widow. But instead of going to the minister and preventing this crime from occurring, Ceceline dressed herself up as a ghost (as one does) and appeared before him, futilely warning him not to marry.

The marriage didn’t prosper anyway, because the rich widow’s: “long unrestrained passions, voluptuous living, and high pampered appetites, had left her vitiated mind only fit for the vilest gratifications; and as they ill suited the natural delicacy of Winstanley’s taste,” she paid for a gigolo.

So really, in this novel, people do senseless things and it turns out they accomplish nothing. Except for the deceitful mistress Harriet, I suppose. She succeeded in luring Winstanley/Fitzavern away from Ceceline by forging a letter. She comes to a miserable end, though, we are told.

Gothic titillation and confusing clues. Imagine generated by Bing AI. Catching all the clues

Gothic titillation and confusing clues. Imagine generated by Bing AI. Catching all the cluesI wonder if the young ladies poring over this tale had any notion what “the vilest gratifications” and the "degrading passions" of the rich widow might be. Or how did they interpret "irresistible nature" and "broke forth" in this passage: "The young and interesting Antonia hanging with easy, innocent fondness on his bosom… proved too much for the high and ardent spirits of…. Arthur Fitzavern; --nature, irresistible nature broke forth, and without either motion or speech betraying, Mrs. Courtney penetrated the secret.”

Hopefully the female readers spent more time pondering the double standard the author upholds between male and female conduct. But more than that, I wonder: did the early readers of this book recollect every previously-inexplicable detail that had gone before the Big Reveal, and did they say to themselves, aha, so when Frederick/Ceceline turned pale and rushed away when Harriet Winstanley arrived at Mrs. Courtney’s, it’s because she recognized her old-backstabbing friend. Or, did they turn back to volume one to re-skim all those passages which made no sense before?

Jane Austen is not the first to string clues and hints throughout her tale, but we can read and re-read Emma with pleasure, finding some new nuance to savor every time. Austen can withhold information from us and still create a coherent and interesting story that doesn't rely on salacious details to keep us turning the pages. Content warning: this section reproduces callous references to enslaved people

The other aspect of this book which might be of interest is the matter-of-fact portrayal of enslavement in Barbados. No amount of academic detachment is going to prepare you for certain words strung together in a certain way, such as: Mrs. Courtney’s “slaves were numerous, and it was her pleasure to let them live happily. Her plantations were extensive, and they not only sheltered and supplied the sable inhabitants in her service, but also gave employment and independence to many Europeans and their families.”

As well it's jarring, to say the least, to see Winstanley, a plantation-owner, speak blithely to the rich widow about love, slaves and chains:

“Thou art a dear provoking wretch, Winstanley,” [says the widow flirtatiously]

“I would provoke you,” kissing her hand, “to make me a willing slave for life. –How I should glory in my chains!”

“They shall hang easy on you,” cried the lady, “do not fear them—”

“Fear them!” interrupted he, “I die,--I languish for them!”

These passages, and others, tell us that although abolition had been hotly debated, you could still encounter a variety of opinions in the novels of the day, from vehement abolitionism to casual acceptance of enslavement. Whichever side you were on, there was no need to use veiled allusions.

About the author:

About the author:Isabella Kelly (1759–1857) was a prolific authoress, chiefly of Gothic novels, who supported her children after her two marriages did not prosper. She lived in poverty most of her life. She lived to the age of 98, calling herself the last surviving novelist of her era. In A Modern Incident, she worked in some lavish praise of the successful author Matthew “Monk” Lewis, “one whose nature reflects honour on the human kind,” because he had been helping one of her sons find work. James Fordyce, of Fordyce’s Sermons, was her uncle.

Scholar Yael Shapiro points out that Kelly focused on marital troubles in her novels, as opposed to ending her books with weddings: “Where [Gothic best-seller Ann] Radcliffe sets up a sharp dichotomy between good and bad marriages, Kelly’s novels seem to accept men’s controlling behavior as a possible part of any marriage.”

Rachel Feder, in a new book about Jane Austen and cultural tropes (of which much more in future) points out “Gothic novels… simultaneously offered an escape from and a commentary on the real world, which has always been dangerous for women [the real world, that is]. [T]hese stories were often subversive but not particularly progressive.”

That's certainly my take on A Modern Incident." We have some subversive fun with some same-sex and incest teases, (if that's your idea of fun), then the author winds up her tale with more double-standard morality: “Let the sons of pleasure and indulgence, should any such ever turn this melancholy page, learn from the fate of Fitzavern, that if they do not restrain the irregularity of wild desires when they ought, they may not be able to do it when they would.--but that consequences come with ruin, and with despair.

“And let the daughters of pain and disappointment, when dropping a tear to the sorrows, and the memory of Ceceline, not suppose such sorrows were in vain;--they purified her for a society of angels, and purchased her an early immortality.” Shapira, Yael. “Beyond the Radcliffe Formula: Isabella Kelly and the Gothic Troubles of the Married Heroine.” Women's Writing: the Elizabethan to Victorian Period, vol. 26, no. 3, 2019, pp. 245–63.

Previous post: Innocent Ellen, a gothic heroine

Published on January 10, 2024 00:00

January 4, 2024

CMP#167 Ellen, the innocent heroine

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP#167 Book Review: Glenmore Abbey, or the Lady of the Rock (1805) by Mrs. Isaacs

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP#167 Book Review: Glenmore Abbey, or the Lady of the Rock (1805) by Mrs. Isaacs

Fixated on one thing: "Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow," Georgia O'Keefe, 1923 Welcome to the New Year, a time for clean slates. Virgin and unspoiled, as it were. I didn't plan this, but it looks like January will be devoted to novels that obsess on the theme of Female Chastity and Female Reputation, or as they called it, "Fame." In all of January's novels, the big page-turning question is: can the heroine preserve her virtue and/or will the heroine be able to clear her name after her virtue has been impugned? Reading a succession of these novels really brings home the emphasis put on female virtue in the society of the time. And of course, not only the Georgian/Regency era but before and after, up to the sexual revolution of the 1960's. Some novels, like this one, take up the question of illegitimacy as well.

Fixated on one thing: "Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow," Georgia O'Keefe, 1923 Welcome to the New Year, a time for clean slates. Virgin and unspoiled, as it were. I didn't plan this, but it looks like January will be devoted to novels that obsess on the theme of Female Chastity and Female Reputation, or as they called it, "Fame." In all of January's novels, the big page-turning question is: can the heroine preserve her virtue and/or will the heroine be able to clear her name after her virtue has been impugned? Reading a succession of these novels really brings home the emphasis put on female virtue in the society of the time. And of course, not only the Georgian/Regency era but before and after, up to the sexual revolution of the 1960's. Some novels, like this one, take up the question of illegitimacy as well.In my study of 18th-century novels, I don’t usually read Gothic novels because (1) they currently receive plenty of attention in academic circles and (2) I’m studying Jane Austen in the context of the conventions and tropes of the sentimental novel, not the gothic. But Glenmore Abbey popped up in my search results twice for containing some phrases which Austen satirically used. Remember how Mrs. Elton kept boasting about her “resources,” which would keep her occupied and entertained in the small village of Highbury? The same term appears in Glenmore Abbey. And twice, characters are offered the “balm of consolation” poured into “wounded bosoms,” à la Mary Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. Finally, Glenmore Abbey never received a review when it was published, and I like giving attention to such long-ignored books.

But I'm not going to denigrate Mrs. Isaacs for writing with trite clichés, although she certainly does at times: “To do justice to the ruined towers of Glenmore, the pen of ancient romance should delineate the thick clustering turrets, the broken columns, the fallen pillars, and mouldering battlements, that frowned over the gloomy domain. It was extensive and had once been well cultivated, but neglect had rendered it a barren waste, and the high trees, around many of which the climbing ivy had entwined itself, were merely a resort for the seafowl and birds of prey… (etc.)”

Let’s be fair, she’s probably writing for money, and she’s writing to a specific formula, in emulation of the very successful Anne Radcliffe—in other words she is checking the boxes with a tale that includes mystery, suspense, a touch of the supernatural, and moral lessons...

Holyrood Abbey in Scotland Gothic mystery

Holyrood Abbey in Scotland Gothic mysteryOur story opens with young Arthur Fitzelvan, the second son of a second son of an Earl, and the first of four noble families where the oldest son is a waste of space and the second son is principled and decent. Arthur has just inherited a half-ruined Abbey from his dissolute uncle. He pays a visit and hears a haunting female voice singing a plaintive air. He discovers the singer is a beautiful and artless girl. He learns from the aged servants that Ellen is the natural daughter of his late dissolute uncle, who, come to think of it, was harboring a guilty secret when he died.

Ellen has grown up in almost complete isolation in the Scottish Highlands. I think Arthur is the first young man she has actually laid eyes upon. She harbors a secret sorrow because it is believed her mother threw herself off a nearby cliff into the ocean, distraught over her fall from virtue, leaving the infant Ellen behind.

Arthur sets about patching up the Abbey, and he sends Ellen to live with his kind and decent family in England.

Unlike many Regency writers, Mrs. Isaacs only introduces characters when and as she needs them for the plot, and she does not introduce characters just for the sake of ‘’a parade of character types,’’ to borrow Juliet McMaster’s expression. Thus in England we meet other young men and women, (such as Arthur’s sister Adeline, who is harboring a secret sorrow), all of whom play some role in the plot or are involved in a sub-plot. We meet the morally upright Mr. and Mrs. Fitzelvan and Mr. Fitzelvan’s snotty older brother who is angling for a mercenary marriage for his daughter. When the action moves to London, we meet some society folk, like the beautiful Lady Westmere, who is harboring a secret sorrow.

The horrors of ennui: AI generated image Meanwhile Arthur of course is falling for Ellen, but Arthur’s older, cynical friend Mr. Mellors tries to talk him out of it. His issue is not that Ellen is illegitimate and has no fortune—this doesn’t seem to be a problem at all, because she has to swat away several marriage proposals from well-born but unwanted suitors in the course of the book—Mr. Mellors thinks her upbringing was so sheltered that her character and principles must be unformed and untested. All she’s ever done is ramble about the Scottish Highlands with her little dog, making wreaths and daisy chains. And writing poetry, but I will spare you any samples of it.

The horrors of ennui: AI generated image Meanwhile Arthur of course is falling for Ellen, but Arthur’s older, cynical friend Mr. Mellors tries to talk him out of it. His issue is not that Ellen is illegitimate and has no fortune—this doesn’t seem to be a problem at all, because she has to swat away several marriage proposals from well-born but unwanted suitors in the course of the book—Mr. Mellors thinks her upbringing was so sheltered that her character and principles must be unformed and untested. All she’s ever done is ramble about the Scottish Highlands with her little dog, making wreaths and daisy chains. And writing poetry, but I will spare you any samples of it.I very confidently placed down some prediction markers at the end of Volume 1: Ellen will be revealed to be of legitimate and probably noble birth. Also, a mysterious lady who lived near Glenmore Abbey, and a mysterious older man who stalks Ellen in London, (who is harboring a secret sorrow) will prove to be related to her. Let's read on and see if I was right... Reputation assailed

Arthur’s faith in Ellen is shattered when he mistakenly thinks she is carrying on an affair with the local clergyman’s son. I have come to understand this is a common plot convention of the era; the credulous hero who is ready to believe the worst of the heroine. I’ve encountered it in several other novels, including The Children of the Abbey and Secrets Made Public. (And of course Hero and Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing). Ellen forgives Arthur the first time he throws her under the reputation bus, but the second time he refuses to take her word that nothing is going on, she gives up and returns to Scotland with Arthur’s newly-married sister Adeline. Adeline’s husband Sir James seems to be harboring a guilty secret, and Ellen is surprised to hear a haunting female voice singing a plaintive air issuing from somewhere in the ruins of the castle. Then we meet the neighbors: Lord Glendore, (not to be confused with Glenmore) who is harboring a guilty secret, and his sister Lady Eloisa, who was the mysterious lady who lived near the ruined Abbey. Lady Eloisa is harboring a secret sorrow.

It’s very quiet in Scotland, but “happily for Ellen, she had resources within herself, which would never suffer her to know the horrors of ennui,” and as well, Ellen can’t go for her daily walk without seeing some strange goings-on, or meeting a mysterious stranger, like a half-crazy hermit who harbors a secret sorrow, or the older man who was stalking her in London and who came to Scotland to stalk her some more. Then Ellen realizes that Adeline must be harboring a secret sorrow and possibly a guilty secret, because she is sneaking out at night to meet a man. Spoiler time:

All the secret sorrows and guilty secrets arise from several thwarted or unlucky love-matches. We discover that Adeline is not meeting with a lover but with her disgraced older brother who eloped with the clergyman’s daughter. The neighborhood half-crazy hermit is broken-hearted because his fiancée threw him over for a wealthier man while he was abroad.

After the death of Adeline’s husband in a riding accident, Ellen is free to search out the mysterious female voice and discovers—her own mother! Lady Ellen, the heiress of Kincardine, was locked up in the tower some sixteen years ago to punish her for supposedly having an illegitimate child, because, everybody believed Arthur’s dissolute uncle when he accused her of adultery.

This was actually upsetting to me, I confess, because it’s such a horrible thought. As Henry Tilney said, “do our laws connive” at atrocities like this? Surely to goodness this is a criminal act, even in Scotland? But nobody pays the price because Sir James is dead, and gloomy Lord Glendore, also responsible for this crime, suddenly dies. This means General Glendore, the younger son, is now the Earl of Glendore. He was the mysterious older man who was stalking Ellen. The General spent many years abroad because he believed his lovely wife was unfaithful many years ago with his dissolute best friend, and he assumes that she and their baby daughter are dead. I mean, if you can’t believe what your dissolute best friend tells you, who can you believe?

Lady Ellen is restored to him. The authoress does not give Lady Ellen any dialogue, so we don’t know what a woman who spent sixteen years in near-solitary confinement would have to say.

Romance leads to regret: don't elope (AI generated image) Stern morality

Romance leads to regret: don't elope (AI generated image) Stern morality There are several morals to this story: The first is that mercenary marriages are bad. Parents shouldn't be tyrannical and force their offspring into marriages they don’t want. Adeline is miserable because she married Sir James when she really loved the clergyman’s son. That’s why he was secretly meeting with Ellen--to ask her to plead his case with Adeline. Now that she is a widow, society belle Lady Westmere atones for throwing over her fiancée, who became the half-crazy Scottish hermit. They reunite, presumably after he’s had a bath and a shave.

But eloping with the man you love, without parental permission, is even worse than a mercenary marriage. Selina the clergyman’s daughter dies of remorse and thunderstorms (“Heaven itself is armed against me, and denounces a dreadful vengeance on the violation of filial duty!”), and her husband, Arthur’s older brother, follows suit, but not before Ellen “administered the healing balm of consolation” to them.

With so many unhappy marital situations on display, the authoress thought to include an example of a couple who are perfectly happily married, Lady Westmere’s sister and her husband, and we can also include the older Fitzelvans, who endured some poverty in their early years but pulled through happily. And of course we have our happy ending coming up.

Finally, and most importantly, nothing but nothing is more important than a woman’s reputation for chastity, which is tricky when the men in your life are always ready to believe the worst. So, never mind about punishing anyone connected with locking up an innocent woman for 16 years, we’ve got something more important to focus on--long-hidden letters from Arthur’s dissolute uncle which prove that Lady Ellen repelled his overtures. Her reputation is restored, her daughter Ellen’s reputation is restored, Ellen forgives Arthur for not believing her—again—and they live happily ever after. Any other leftover young men and women who haven’t eloped or tried to elope (i.e., who are still alive) also find mates and get happily married.

Is there a secret message to this story, something in protest of the patriarchy? I don’t think so. Injustices are meted out by an unforgiving system to male and female alike (although the females have the worst of it). The author’s message is consistent: we must humbly accept whatever the Divine Disposer of Events sends our way, while maintaining our own integrity.

Artist's conception: AI generated Image About the authoress:

Artist's conception: AI generated Image About the authoress:There is no information for Mrs. Isaacs from the usual bibliographic and literary sources. She did not write prefaces for her novels, so the bottom line is, I know nothing about her. A Bibliographical Guide to Anglo-Jewish History suggests that Mrs. Isaacs might be Jewish, but there is nothing in the novel to indicate this; the clergymen, churches, churchyards, and death-bed scenes, are all Christian. She published seven books, including a compilation of short stories and poems which includes a few noble titles in her list of subscribers. Looking over the list of subscribers, I can’t even tie her down to a particular part of England. She had several different publishers, including Minerva Press.

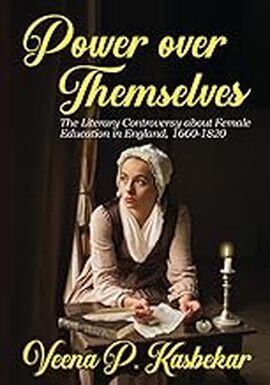

Scholar Veena Kasbekar has this to say about William Lane, the proprietor of the Minerva Press: ‘’Because of the second- or third-rate nature of his publications, Lane’s contribution to women’s literature has not been fairly gauged. Whether or not he exploited them as hack waters, he provided indigent women with a source of income by publishing their works." Previous post: Soaring above mediocrity

Published on January 04, 2024 00:00

December 28, 2023

CMP#166 Sir Edward, the principled hero

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP# 166 Book Review: The Wife and the Lover (1813), (not to mention the idiotic husband)

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP# 166 Book Review: The Wife and the Lover (1813), (not to mention the idiotic husband)

If you really loved me: Image generated by Bing AI The Wife and the Lover is not about a wife who has an affair, as I first surmised. “Lover” in this case refers to a unrequited love, or chivalric love. We first meet the darn-near-perfect hero, Sir Edward Harcourt, talking with his guardian and mentor, Lord Fanshaw. Fanshaw warns Sir Edward, who has recently inherited his baronetcy, to think twice before marrying the beautiful and accomplished Cecilia Fitzallard. Lord Fanshaw does not object to the fact that Cecilia does not come from a distinguished family, or have a large fortune; the problem is that she is rather too full of herself, and apt to take offence where none was intended.

If you really loved me: Image generated by Bing AI The Wife and the Lover is not about a wife who has an affair, as I first surmised. “Lover” in this case refers to a unrequited love, or chivalric love. We first meet the darn-near-perfect hero, Sir Edward Harcourt, talking with his guardian and mentor, Lord Fanshaw. Fanshaw warns Sir Edward, who has recently inherited his baronetcy, to think twice before marrying the beautiful and accomplished Cecilia Fitzallard. Lord Fanshaw does not object to the fact that Cecilia does not come from a distinguished family, or have a large fortune; the problem is that she is rather too full of herself, and apt to take offence where none was intended.Sir Edward, however, is head-over-heels for Cecilia.

Lord Fanshaw’s own wife Horatia accidentally proves that the lord had a point; when Horatia makes some joking remarks about Cecilia, which are carried back to her by a character helpfully named Tabitha Wormwood, Cecilia is incensed. She demands that Sir Edward cut off ties to the Fanshaws immediately and forever.

Our hero can’t do it; he owes the Fanshaws, especially Lord Fanshaw, “both gratitude and esteem." Cecilia, accusing him of not loving her enough, breaks off the engagement. Sir Edward leaves his affairs in the hands of his steward and goes abroad to heal his broken heart.

Cecilia has many other admirers, including a visiting German count who is a renowned soldier back in the German principality of *****. Count Falkenstein had an “unfavorable opinion” of “women in general, nor could he forbear to express his disapprobation of the freedom which the English ladies, both before and after marriage, enjoyed.”

A little foreshadowing here: we are told that the count is honorable, brave, handsome, and noble, but he expects unquestioning obedience from a wife. After he and Cecelia are married, he writes to his relatives back in Germany to assure them that she is not like the other outspoken English ladies: “My lovely bride has a just conception of the gentle duties of her sex, and adores that nice sense of honor which cannot tolerate the levity too prevalent in a country where the fair sex enjoy almost unlimited liberty,”

So, are we setting up for a story where the heroine realizes, too late, that she threw away a wonderful man and rashly married a tyrant? You might think so. You might assume that the narrator is going to take Cecilia’s side in what follows.

Nice going, Mr. "Death before dishonor" The Honeymoon is Over

Nice going, Mr. "Death before dishonor" The Honeymoon is OverCecilia and the count move back to Germany, the honeymoon is over, and they start quarreling, but the narrator faults Cecilia for not being forbearing enough. The count is in a bad mood already because he’s fallen out of favour with his ruler. As for Cecilia, he thinks she’s flirting too much. During one of their quarrels, he exclaims: “From this moment, Cecilia, you are free… I will deliver you from the presence of a husband you no longer love…. I will seek an honorable death in some foreign land. My fortune is your’s. Farewell, for ever!” Does Cecilia say to herself, "I guess I was emotionally manipulating Sir Edward the same way--now I see how wrong I was"? Nope.

Cecilia begs her husband to forgive her, lest she be a victim of “eternal anguish and remorse.” Falkenstein forgives her while acknowledging “Though at moments, I fear, I am captious and unjust, this heart while it beats will throb with affection for the most lovely and beloved of women. Bear with its infirmities, dearest Cecilia, with that sweetness you have, till of late, so often shown..”

The count, we must understand, is not a manipulative, controlling, Teutonic jackass. No, the count is a a hero of sensibility. His honour means more to him than his life. His “heart pants” to “rush on the face of danger… and reap fresh laurels on the field of renown,” yada yada, and Cecilia, with the approval of the narrator, struggles to appease and obey him.

Before long the count, impelled by an insult to his honor, challenges his political rival to a duel, and loses. Cecilia is a widow in a foreign country before she’s 20 years old, and her sister-in-law, like Fanny Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, can’t wait to kick her out of the castle, which now belongs to the count’s six-year-old nephew. Cecilia “was not ignorant that the castle and estate, as the count had left no child, would devolve to his eldest nephew; but… Cecilia could not suppose that [her sister-in-law] could forget what was due to the memory of a generous and noble brother.” Hmmm, is Miss Holcroft saying something about the injustice of primogeniture and the inheritance laws of the principality of ****, or is she just setting up a dramatic plot point? I vote the latter.

Now Miss Holcroft turns to the first in a chain of coincidences. Who happens to be in the adjoining room in the inn where Falkenstein fights his fatal duel? Who rushes to console him in his dying moments? Who brings the mournful news to the castle? Yes, it’s Sir Edward.

Of course he wouldn’t be so crass as to attempt to revive his romance when Cecilia has only just been bereaved. And she is so ashamed of having rejected him over a trifling joke made by Lady Fanshaw that she declares: “pride and propriety raise an insurmountable barrier between us, and we must never meet again!”

Never, you got that? Never, because insurmountable reasons.

Thomas Holcroft (foreground) and William Godwin. National Portrait Gallery And now for something completely different

Thomas Holcroft (foreground) and William Godwin. National Portrait Gallery And now for something completely differentThe authoress now keeps us all in suspense while inserting an Italian semi-gothic subplot or two, involving more duels, rapacious priests, and convents, in which Sir Edward helps a young Italian nobleman. Up until now, The authoress has mostly used narration with little dialogue to tell her story. In this middle section of the novel, we switch abruptly to long stretches of dialogue between Sir Edward and some European nobleman who sit around talking about various things, including dueling.

It is often said that Jane Austen never wrote a scene involving only men. Miss Holcroft has no such reticence--she doesn’t hesitate to give us page after page of male conversation. I surmise it is because her father was the writer Thomas Holcroft, and she grew up in the middle of a tight-knit coterie of London radicals. William Godwin (Mary Wollstonecraft’s husband), was always dropping by and the men would sort out the problems of the world until the small hours of the morning.

We’ll skim through this lengthy dialogue to get back to the main plot, only pausing to notice another example of a character expressing an opinion about the condition of women: Speaking of the Turks, a baron says: “Oh, do not name a set of barbarians… who are not only slaves and infidels, but who are the tyrants of the fair sex: were I, like them, blessed with four wives, instead of being their jailor I would be their humble suitor, and I should love them all so extravagantly that not one of them should suspect she had a rival in my heart.”

This ties in with my observation that people in Austen's time tended to see the women of England as being fortunate to be English, as compared to women in other countries, particularly in the East and the Far East. So, where were we?

I need to back up a bit and mention that Sir Edward does good deeds wherever he goes in the course of the novel, like rescuing a family from highwaymen. Back at university, he helped out a poor fellow student, Theodore Elton, who got suckered into losing a lot of money at gaming. Theodore goes on to become a clergyman, like his father. Wherever Sir Edward goes or whatever kind office he performs, he carries a torch for Cecilia, or as they said in those days, he wears the willow.

So Cecilia leaves Germany with a modest pension. She bumps into a family who know Sir Edward, who tell her what a great guy he is, except, gosh, he sure seems to be harbouring some secret sorrow, and isn’t it too bad he never married? He'd make such a great husband. Back in England, Cecilia unfortunately bumps into Tabitha Wormwood, who puts the worst possible construction on everything that’s happened and spreads her malice around town. The foppish Lord Isleworth also exults over Cecilia’s downfall, because she had turned down his hand before accepting the hand of the foreigner. Cecilia ferociously defends her late husband and sends Isleworth packing.

Another aside: although novels like this are usually set amongst the nobility, many specimens of the nobility are presented as deficient in humanity and good sense, such as Lord Isleworth: he is “half conscious that... though a Peer of the realm, and though possessed of fine horses, a fashionable equipage, a French cook, a Swiss porter, and an Italian valet, and though pampered with every luxury that wealth could procure, with all his fancied importance, in reality, was an insignificant, not to say a contemptible being.” This is not necessarily a condemnation of the aristocracy in general. In these novels, there are Good Aristocrats, who fulfill their duties, and Bad Aristocrats, who are evil, and Foolish aristocrats, who are weak and selfish and foppish. Isleworth is one of those.

The Proposal, by John Pettie, 1869 (detail) “[A]s the reader will probably have divined”

The Proposal, by John Pettie, 1869 (detail) “[A]s the reader will probably have divined”More amazing coincidences follow: Cecilia falls very ill at an inn and is assisted by a young clergyman and his sister. It's Theodore Elton and his sister! She wants to live out of society, so she finds a quiet home with a clergyman and his wife. Their son, also a clergyman, comes to visit, with a young Italian friend. Yes, it’s the Eltons, as well as the young Italian nobleman who Sir Edward helped out of some scrape or other back in Italy.

Both Theodore and Casimir fall in love with our heroine, so she escapes, seeking deeper solitude in the Scottish highlands. And who should she run into in the middle of nowhere but Tabitha Wormwood? This time, she decides to go to Paris and enter a convent. Surely she won’t run into anybody she knows there. But guess who is renting the adjoining room in the inn on the way to London? Hint: Cecelia overhears him talking about his deathless love for her.

Still deeming herself unworthy, Cecilia continues to Calais, where just about everybody shows up, including the Fanshaws (remember them?) and Theodore Elton. And Sir Edward. He drops to one knee and proposes--"accept the vows of your adoring Edward"--and she finally says 'yes.'

The story is quickly wrapped up after that. Elton and the young Italian count conquer their passion for Cecilia and the author awards them with nice wives; we are assured that Lord Isleworth is miserable in his marriage with Lady Augusta Merton… a peeress in her own right: "his lady, like himself, was proud, haughty, narrow-minded, and destitute of every mental or personal grace: he was miserable at home, and comfortless abroad…” Sir Edward and Cecilia are happy ever after because, as Mr. Knightley put it to Mrs. Weston in Emma, Cecilia understands "the very material matrimonial point of submitting your own will, and doing as you were bid."

Miss Holcroft by John Opie About the author: soaring above mediocrity

Miss Holcroft by John Opie About the author: soaring above mediocrityThe Critical Review said of The Wife and the Lover: " Generally speaking, our best novelists are females. Miss Holcroft... does not class with the higher order, but certainly soars above mediocrity... The language is chaste, and so is the moral."

It's been a while since we've had a portrait of one of our forgotten authoresses. Sometimes we don't even know their life dates. Fanny Holcroft (1780–1844), like her father Thomas Holcroft (1745-1809), was painted by Amelia Opie's husband, because her father was part of a coterie of radical intellectuals to which the Opies belonged in the heady days of the French Revolution. "Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven" and Fanny was just old enough to catch the enthusiasm, the ferment of ideas, the hope that a new age was dawning for all mankind. (In comparison, Godwin's daughter Mary Shelley was born in 1797, during the anti-Jacobin backlash, when life for Holcroft and Godwin was much like being a blacklisted Hollywood writer during the Red Scare.)

Thomas Holcroft was a man who put his political principles first, and in consequence, was charged with treason (but the charges were dropped), and he was often on the brink of debtor’s prison. Fanny Holcroft’s confidence in taking her characters to Europe--something Austen would never have attempted--is explained by the fact that her father took the family to Europe for three years, partly because he had become so unpopular in England, and partly to escape his debts.

So why does the daughter of a radical, an associate of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, write a novel advocating wifely submission? Is she rebelling against dad and reverting to a conservative outlook? As it happens, her father also created a long-suffering forbearing wife in his play The Deserted Daughter (1795), and Godwin's publishing company sold books for young ladies which advocated wifely submission. Was it their sincere belief that wives should submit to their husbands? Or were they all writing to the market? Or was it ironic subversion? I doubt it was the third thing, but possibly the second. Scholar Amy Garnai has examined Fanny Holcroft's plays and concluded that in her plays “as well as in her novels, Fanny never moves beyond conventional themes, behaviors, and tropes.”

If Miss Holcroft didn't believe in the message she was preaching in this novel, she had a very good reason for trimming her beliefs to the prevailing winds of opinion. When Holcroft died in 1809, he left six children under the age of ten. Fanny’s stepmother and her step-siblings were literally facing homelessness and starvation. Their friends wanted to help, but were disastrously poor themselves. So, full respect to Fanny Holcroft; she tried starting a school with her stepmother, she worked as a teacher and a music teacher, and lived out the rest of her life in Miss Bates-like genteel poverty. One of her former pupils called her a "Quixote... in Honor and Truth," that is, someone who was so earnestly virtuous, so sweet and idealistic, that she was a bit eccentric.

Fanny Holcroft died “of mania” in 1844, age 64. Incidentally, chalk The Wife and the Lover up as yet another novel in which a character is dispatched to the West Indies purely to remove him from the sphere of action. Once Lord and Lady Fanshaw serve their purpose in the novel's opening, they hop on a boat. Lord Fanshaw is kept offstage, serving as the governor of one of the West Indies colonies until he is needed for the novel's conclusion. And he is a Good Aristocrat, remember. Miss Holcroft was by no means indifferent to slavery--she wrote the abolitionist poem, The Negro, but she used the West Indies to park the Fanshaws in until she needed them.

The West Indies would have had unhappy personal associations for Fanny Holcroft because her half-brother William committed suicide, aged 16, in a ship that was set to sail for the West Indies. He had bought passage with money stolen from his father, and when Holcroft came looking for him, he shot himself. A grim family tragedy. Later, Holcroft thought that Godwin had based a stern father in his novel Fleetwood on this tragedy, and he broke with Godwin. They were only reconciled on Holcroft's deathbed.

Garnai, Amy. Thomas Holcroft’s Revolutionary Drama: Reception and Afterlives. Rutgers University Press, 2023.

The full and fascinating story of William Godwin and his circle is told in William St. Clair's book The Godwins and the Shelleys: A Biography of a Family. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. Previous post: The debate over female education

Published on December 28, 2023 00:00

December 17, 2023

CMP#165 Power Over Themselves

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#165 Book Review: Power Over Themselves: the Literary Controversy about Female Education in England, 1660-1820, by Veena Kasbekar

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#165 Book Review: Power Over Themselves: the Literary Controversy about Female Education in England, 1660-1820, by Veena Kasbekar

Ladies examining a globe: Adam Buck (1759-1833) The debate around female education in the Georgian and Regency periods of England was an astonishingly long-lived and vigorous dispute that was taken up in drawing rooms, newspapers, journals, advice books and even novels of the period.

Ladies examining a globe: Adam Buck (1759-1833) The debate around female education in the Georgian and Regency periods of England was an astonishingly long-lived and vigorous dispute that was taken up in drawing rooms, newspapers, journals, advice books and even novels of the period.In Power Over Themselves, Veena Kasbekar outlines the prominent voices and arguments on each side of the female education debate--I say "each side" because the debate is roughly divided into "radicals" like Mary Wollstonecraft and "reactionaries" like Hannah More. While Kasbekar makes it clear which team she's on, she presents the arguments clearly.

When I started reading novels of the long 18th century, I was surprised how often the topic of education came up, and how often the education the heroine or some other character received, or didn't receive, was mentioned by the author either directly or indirectly. For example, in Mansfield Park, Jane Austen stresses that Maria and Julia Bertram received a thorough education in dates and facts, but imbibed no moral principles. In Persuasion, Anne Elliott's knowledge of literature, poetry, and belles lettres is just about the only thing that can console her in her dreary life.

Kasbekar writes that novels "served an implicit educational purpose by demonstrating how the hero's or heroine's education directly influenced her or his reaction to the vicissitudes of life and love." As in novels, so it was in eighteenth-century life: in Power Over Themselves, Veena Kasbekar recounts how the writers, philosophers, and moralists of the past fiercely debated what sort of education women should receive, what sort of knowledge they were equipped to handle, the purpose of that education, and the dangers of too much education.

I am personally interested in the novels but many types of literature are discussed in Power Over Themselves, including the infamous conduct books and sermons for young women, and guides to female education, written for women by women.

Thanks to Kasbekar's thorough study of the voices of the past, we have an invaluable resource and overview of the debate about female education, from the earliest proponents for education for women, to the reformers of the Victorian age. Most people today have heard of Mary Wollstonecraft, but there is so much more to the story, with names and books and arguments you might not know about. For example, in 1779, a man named William Alexander published A History of Women, from the Earliest Antiquity to the Present Times. Kaskebar explains that ''among other things, he celebrated women's contributions to society and to the progress of civilization itself, especially the invention of spinning and sewing and in the field of medical knowledge.''

Thanks to Kasbekar's thorough study of the voices of the past, we have an invaluable resource and overview of the debate about female education, from the earliest proponents for education for women, to the reformers of the Victorian age. Most people today have heard of Mary Wollstonecraft, but there is so much more to the story, with names and books and arguments you might not know about. For example, in 1779, a man named William Alexander published A History of Women, from the Earliest Antiquity to the Present Times. Kaskebar explains that ''among other things, he celebrated women's contributions to society and to the progress of civilization itself, especially the invention of spinning and sewing and in the field of medical knowledge.'' Kasbekar also takes note, and we should remember, that the debate was mostly confined to the small slice of upper-class and middling gentry. In other words, class as well as gender comes into this. It was more generally agreed that the lower class of women needed an education in some useful trade because they, unlike gentlewomen, needed to work. As well, both sides agreed that a focus on acquiring accomplishments like singing, playing, and drawing, was a frivolous waste of time. ''The radicals were especially scornful of the excesses of the education of the person, which system included a detailed attention to physical appearance, dress, and the accomplishments. By encouraging such an education, argued Wollstonecraft, male writers from Rousseau and Gregory to Edmund Burke... attempted to ensure that women remained artificial, weak creatures, whose sole interest in early life was to secure a husband through the arts of a mistress rather than through reason and virtue.'' Hannah More, the conservative writer, agreed, but for different reasons: ''She objected that girls were educated only for the transient period of youth, for a crowd rather than for living at home, for the world and not for themselves (that is, spiritually), for show and not for use, for time and not for eternity.''

The last section of the book takes us into the Victorian era, when attitudes toward women in the professions, and access to higher education for women, finally began to change, "after two whole centuries of agitation by feminist thinkers."

Power Over Themselves would be a great starting-point for anyone doing research into female education in this period, or the debate around women more generally.

Power Over Themselves, although adapted from a thesis and thoroughly referenced, is refreshingly readable and free from academic jargon or pomposity. If you are undertaking a study of feminism or female education in this era, start with this book!

For some of my past blog posts about female education, start here. Previous post: A biracial hero

Published on December 17, 2023 00:00

December 12, 2023

CMP#164 George Arrandale, the biracial hero

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP#164 Book Review: A Summer at Weymouth (1808)

Clutching My Pearls is dedicated to countering post-modern interpretations of Jane Austen with research that examines her novels in their historical and literary context. I also read and review the forgotten novels of the Georgian and Regency era and compare and contrast them with Austen's. Click here for the first post in the series. Click here for my six critical questions for scholars. CMP#164 Book Review: A Summer at Weymouth (1808)

Irresistible to the ladies A Summer at Weymouth is a novel written in imitation of the immensely popular A Winter in London by Thomas Skinner Surr (1806), which I reviewed here. The novel touches on many of the preoccupations of the day, but first we have to talk about the fact that a love-rival for the heroine is biracial and nobody has an issue with this. “[A]lthough his dark complexion discovered him to be on one side the son of an Indian, the regular beauty of his features, the sensible expression of his fine dark eyes, and the symmetry of his graceful form adorned by the most polished manners rendered him the admiration of all who beheld him.” He is “skilled in the Persian, Arabian, and Indostan music, and sung the songs of those languages with great expression.” He also dances divinely. Our main heroine, Stella Fitzalbion, knew him from boyhood and has a crush on him.