Lona Manning's Blog, page 9

October 31, 2023

CMP#159 Isabel & Elizabeth, the dutiful heroines

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#159 More reviews for forgotten books

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#159 More reviews for forgotten books

Morally improving The

previous forgotten book I reviewed,

The Metropolis, dwelt on the seamier side of London life; the fleshpots of Covent Garden and the propensity of wealthy people to destroy their lives over a game of cards. The next novel I picked up, alas, instantly delved into the same theme, but there is a big difference between the two titles which is worth noting in light of the debates which were raging at that time over the

morality and propriety

of reading novels.

Morally improving The

previous forgotten book I reviewed,

The Metropolis, dwelt on the seamier side of London life; the fleshpots of Covent Garden and the propensity of wealthy people to destroy their lives over a game of cards. The next novel I picked up, alas, instantly delved into the same theme, but there is a big difference between the two titles which is worth noting in light of the debates which were raging at that time over the

morality and propriety

of reading novels.The Metropolis received no reviews but if it had, I think the reviewers would have called it a book--to use their phrase--that you could not safely put into the hands of your daughter or sister. It is too detailed in its depiction of vice, and the vices and crimes committed in the book (fornication, gambling, cheating at gambling, highway robbery) are not sufficiently condemned or punished. The Decision (1811), while going over much of the same ground, and in fact including a main character who commits criminal acts, would be safe for a girl to read because it is overtly religious and didactic. A reviewer said: “We trace in these volumes a laudable endeavour to convey as much moral instruction as could be admitted into a work of fancy.” Yes, The Decision is stuffed like a plum pudding with the wholesome raisins of morality. The title refers to the heroine's decision to put her father's wishes ahead of her own, and later, to turn down a fortune in exchange for marriage.

The Decision begins with a long and confessional letter from Charles Arundel to his old friend Mr. Beverly. Arundel married for love but becomes a gambler and a philanderer. At his dying uncle’s bedside, he sees that he’s been cut out of the will, which would lead to his ruin. He destroys the will and even poisons the uncle. He lives with his guilt until later on in life, after he is widowed, he decides to go to the West Indies and meet the young relative whose father was unknowingly cut out of the will.

The mention of the West Indies will bring thoughts of slavery to mind for the attentive modern reader, but there is no mention of slavery or colonial exploitation as a sin or even as a cause of remorse in this book--a book which features many people who do things that they regret, such as marrying for ambition. Once again the West Indies are a plot device to remove the father from the action, so the heroine can live with the Beverly family. Guilty secrets

When Charles Arundel goes to the West Indies to atone for the crimes of his younger days. He leaves his daughter Isabel with Mr. Beverly and his family. Isabel is lovely and intelligent, a fact that doesn’t escape the notice of Mr. Beverly’s son Valcourt, but he is already engaged to a society belle. Rounding out the characters, we have some sisters and the mother, Mrs. Beverly, who makes life miserable for her husband with her extravagance and socializing. She believes she's entitled to do as she likes because she brought a fortune to the marriage, but she runs the family into debt. A reminder that the often-repeated notion that “women couldn’t inherit” back then is incorrect, and that wives could bankrupt and ruin their families just as husbands or irresponsible sons could. We’re told she ruins several tradesmen’s families when she doesn’t pay her bills. The Beverly women, and Valcourt's vain and shallow fiancée are contrasted with the virtuous and principled Isabel. We learn all about the faults of Mrs. Beverly--a cold wife, a partial and ill-judging mother--through the gossipy and unflattering things Isabel writes in her letters to her father about her host family. Mrs. Beverly's sins are first punished by the death of her youngest son, whom she both over-indulged and neglected. Mr. Arundel arranges matters so that Isabel pays the price for his wrongdoings. Stir in a few more rivals for Isabel's hand, and add a series of impediments keeping the hero and heroine apart. For once I’m not going to give all the plot spoilers; suffice it to say I thought it was good melodramatic fun and there was only one amazing coincidence. Being virtuous does not spare the main characters from suffering and hardship, but misbehaviour brings others sorrowing to their graves. It’s a lively soap opera interspersed with moral lessons. Silly and old-fashioned? Sure, but don't the phony videos posted on social media, showing people who behave badly getting their comeuppance, show that people are just as drawn to morality plays today?

Willoughby (1823)

Willoughby (1823)The same anonymous author also wrote Willoughby, or Reformation, the influence of religious principles (1823), The Acceptance (1810), and Caroline Ormsby or the real Lucilla, interspered with sketches moral and religious (1811). “Lucilla” is a reference to the heroine of Hannah More’s staggeringly popular novel, Coelebs in Search of a Wife, which spawned a host of imitators. I just peeked into Caroline Ormsby, but I read Willoughby to see how this Willoughby compared with Austen's character. Willoughby Coventry is the only son of a respectable family. From the outset of the novel, Willoughby is a dissolute, gambler and a selfish coward. The subtitle promises us that Willoughby will redeem himself, but why I should care whether he redeems himself or not, I don’t know.

The Coventry family--and the father--are finished off with more financial blows; a shipwreck in which they lose some property, and a bank failure. Willoughby responds with nervous collapse and is no help in supporting his mother and sister. He somehow manages to win the affections of a silly young heiress, because he is “fascinating” and “handsome.” The author wasn't able to show the fascinating side of this character, though, we are just told he's fascinating. The young bride exults, Lydia-like, in having her way: “When I look at the ring on my finger, and think I am married, it is so droll, I quite laugh at the idea.” Alas, the marriage soon goes sideways, and Willoughby continues to be a waste of space. He finally pulls himself together after a near-death experience in the third volume, and after his wife’s death, he finds happiness with a worthy woman.

Willoughby’s virtuous sister Elizabeth, on the other hand, doesn't hesitate to take a job as a governess to help support her mother and announces that it is no degradation to do so.

Our anonymous author specializes in virtuous females who are brought into desperate straits by the bad decisions of their male relatives, but these heroines are always resigned and saintly and display unconditional love for their wretched fathers. In The Decision, Isabel resolves to obey her dying father's injunction to marry her cousin Horatio, even though she's in love with Valcourt Beverly and he with her: “watching the altered looks and languid breath of her father, she almost gloried in the sacrifice of her own happiness, could it ensure to him the blessing of peace in these last eventful hours.”

In Willoughby, an off-stage character named Matilda consents to marry a rich man she doesn’t love to pay off her father’s gambling debts. Her husband dies, her father dies, and she dies of grief, so it’s hard to see what she gained by her sacrifice. But the author praises her up as a saint. This is evidently female behavior to emulate. Elizabeth at least ends up happily married with a convenient fortune. Deservedly forgotten?

This author espouses beliefs and a worldview which might appeal to some traditionally-minded readers, but I'm coming to feel that the moral codes promoted in these sentimental novels will prevent a revival of this and other forgotten authors. My own interest arises out of looking at what these novels say about the preoccupations of the society they were written for, what publishers offered to readers, what critics praised or condemned, and how it compares to Austen.

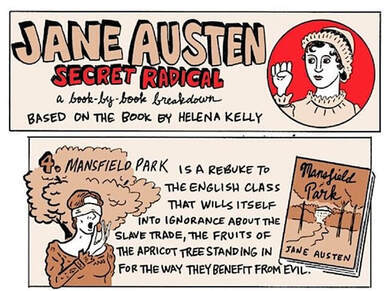

Austen handles the same topics and Christian beliefs but she's quite subtle and indirect: you can catch the faintest allusion to redemption and salvation in Mansfield Park, her most didactic novel, when Fanny Price is worried that her cousin Tom Bertram’s illness might be fatal. “Without any particular affection for her eldest cousin, her tenderness of heart made her feel that she could not spare him, and the purity of her principles added yet a keener solicitude, when she considered how little useful, how little self-denying his life had (apparently) been.” That “keener solicitude” might sail right past a reader not familiar with Christian doctrines.

Jane Austen also kept the sordid stuff off stage in her novels. Willoughby’s seduction of Eliza, Maria Bertram Rushworth’s adultery with Henry Crawford, and Lydia living in sin with Wickham--they are all discussed at second-hand, not directly narrated. We never enter a bordello or a gaming hell with Austen.

Snakes and Ladders

Snakes and LaddersAfter reading a lot of these novels, it really strikes me how often authors resort to beggaring a family through gambling debts or bank failures, or enriching a family through unexpected bequests of East and West Indian fortunes. It’s like a Regency game of snakes and ladders with heroes and heroines either tumbling down into financial ruin or suddenly climbing up to fabulous wealth, as their authors roll the dice and move them around the board. The Decision features a long-lost relative (actually in this case, an old friend) returning from the East Indies with a fortune to bestow on the heroine in time for her marriage. This is an exceedingly common plot device of the time. In Willoughby, one of Elizabeth's suitors comes into a fortune (one of those convenient uncles) and she is able to marry and give a home to her mother.

Austen found a different way to impoverish the Dashwood girls in Sense and Sensibility, but a small West Indian fortune comes to the rescue for Mrs. Smith in the final page of Persuasion.

In all three of these novels--The Decision, Willoughby, and Mansfield Park--the fact of slavery and colonialism is present in the background, but not held up for examination or condemnation. No consequences flow from the fact that the wealth which props up these families comes from chattel slavery despite the fact that these novels grapple with the questions of correct moral conduct as a central theme. Other authors did condemn slavery, and it is interesting to see such a wide disparity of consciousness about slavery in the novels of this era. About the author

The works of this novelist have been misattributed to female authors such as Grace Kennedy, Barbara Hofland, and Jane West. But the reviewers of Caroline Ormsby speak of the author as a "he." The confusion seems to arise out of the fact that there were multiple novels titled Decision. Another possible clue is found in the second volume of Caroline Ormsby, which includes a letter from a mother to a daughter, advising her to avoid attempting to become a novelist, lest she neglect her domestic duties and make herself ridiculous. This, I suppose, makes it more likely that the author is a male, but I still suspect the writer is a female. However, I can't imagine any academic championing her as an author worth re-discovering.

We know nothing about the author of these books other than the fact that (s)he was conventionally religious. (S)he includes a minor character, a fanatical Methodist woman who despises all earthly enjoyments, in Willoughby. (S)he gives away nothing about herself in her prefaces, and merely repeats the moral lessons she intends to promote in the story. Her/his books were published by Henry Colburn. Previous post: Brian, the lucky hero

Published on October 31, 2023 00:00

October 26, 2023

CMP#158 Brian, the lucky hero

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

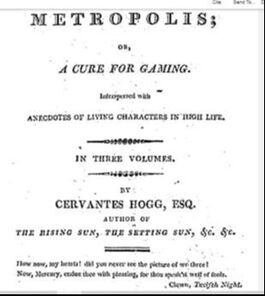

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#158 A first review of The Metropolis, or, a Cure for Gaming: Interspersed with Anecdotes of Living Characters in High Life (1811), by Cervantes Hogg (pseud)

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#158 A first review of The Metropolis, or, a Cure for Gaming: Interspersed with Anecdotes of Living Characters in High Life (1811), by Cervantes Hogg (pseud)

This is the first review that The Metropolis, a novel published two hundred and twelve years ago, has received, but it’s just as well the author didn’t hang around for my verdict. I don’t think I can be objective because so much of the story is taken up with scenes of gaming (card playing, dice, and horse-racing). I have trouble mustering interest, let alone sympathy, for people who stay up until four in the morning, playing at cards until they destroy themselves.

This is the first review that The Metropolis, a novel published two hundred and twelve years ago, has received, but it’s just as well the author didn’t hang around for my verdict. I don’t think I can be objective because so much of the story is taken up with scenes of gaming (card playing, dice, and horse-racing). I have trouble mustering interest, let alone sympathy, for people who stay up until four in the morning, playing at cards until they destroy themselves. The title tells you that London is the real subject of the novel; that is, the vortex of dissipation that is Regency London. "Anecdotes of living characters in high life" tells us the story portrays the upper classes behaving badly, so the readers from the growing middle classes could tut-tut over baronets who were boobies, and silly knights who were selfish gourmands, and duchesses who gambled their fortunes away. Even the Prince of Wales (that is, George just before he became Prince Regent), makes an appearance and is upbraided for his faults.

So this is one of those novels that purports to combat vice by describing vice. Since gambling strikes me as being, as one wag put it, a tax on the mathematically incompetent, I am not titillated by descriptions of it. I'm just alternately bored and disgusted.

The author also commits poetry--he includes a long and tragic poem about a young man who ruins others and ruins himself by gaming. The poem provides the strong moral lesson which is missing from the main storyline; serious moral lessons were essential to getting a good review in those days. With so many people opposing novel-reading, defenders of the novel countered that that a well -told story could effectively convey a moral lesson.

But Metropolis's plot provides, at best, a morally ambiguous tale.

Accosting girls in the hallways and lobbies of the theatres A Lucky Break

Accosting girls in the hallways and lobbies of the theatres A Lucky BreakBrian Bonnycastle is the son of an impoverished vicar with a large family. “A rich merchant, a Mr. Hewson, of St. MaryAxe, London, an old acquaintance of the vicar, had offered to ease him of part of his heavy family, by taking Brian, the eldest son, into his counting-house, which offer of disinterested friendship Mr. Bonnycastle had joyfully accepted.” Mr. Hewson is portrayed as intelligent, upright, kind, and humane, unlike so many portraits of vulgar merchants of the time. Brian lives with the family and naturally, he falls in love with the beautiful Charlotte Hewson, and she with him. He feels his love is hopeless, given that she’s a wealthy heiress and he’s a clerk, but he is startled into confessing his love for her after coming to her defense at the opera.

Almost any time the heroine of a sentimental novel goes to the opera or theatre, something unpleasant happens, usually involving some boorish and drunken “gentleman” who takes liberties with her. In this case, the boorish gentlemen somehow know that Charlotte is a merchant’s daughter and one of them insults her thus: “As she turned away to avoid their impertinent gaze, one of them raised the edge of her hat,” praises her beauty, and asks her to become his mistress: “Will you be my chere amie, and exchange a shop for elegant apartments?”

The Rise and Fall of Brian

The Rise and Fall of BrianBrian punches the cad in the face, whereupon our hero is challenged to a duel, which he accepts. An army captain, overhearing the confrontation, offers himself as Brian’s second. Both combatants are wounded. Luckily for the naïve Brian, his new friend Captain Fascine finds him an excellent surgeon to remove the bullet and heal the wound. Fascine will become the secondary hero and fall in love with Charlotte’s best friend, the saucy Miss Thrum.

The uproar over the duel means that Brian’s love for Charlotte, and her love for him, are out in the open and (to my surprise) the wealth disparity is not an impediment. Mr. Hewson blesses the engagement, in recognition of Brian's many virtues and his great promise. So what does Brian do? He immediately throws it all away, through the bad influence of Charlotte’s brother, who has returned from the Grand Tour. He takes Brian along to his favorite London brothels and gaming dens. From this point in the novel, we spend a lot of time in Covent Garden and other spots. The narrative is never explicit or graphic, but we learn that our hero sleeps with prostitutes and acquires a mistress, named Mrs. Fisher.

Joan Greenwood as Lady Bellaston in the 1963 Tom Jones movie Third-rate Fielding?

Joan Greenwood as Lady Bellaston in the 1963 Tom Jones movie Third-rate Fielding?As the story progresses, more characters are introduced; a duchess who is a gambling addict, a girl sold into a loveless marriage, a baronet’s widow who is an Amazon, a gluttonous knight, and a clever servant who speaks with a strong West Country accent: (Wull ye take me up or no, Zur? I hopes I ben’t rude, but I don’t like to hear my mare run down").

Brian is rescued from his downward course when he’s taken up by a reformed gambler named Verjuice. Well, reformed in a very particular sense. Verjuice opens Brian’s eyes to the fact that he’s being fleeced by his Covent Garden friends. He teaches Brian how to out-sharp the sharpers; and instead of losing money, he and Verjuice start building up a handsome stake.

Brian wants to win Charlotte back but he knows he'll never be allowed to marry her so long as he is nothing more than a professional gambler. He proposes that he should “bestow my money [i.e. bribe] any person possessed of sufficient interest to procure me a genteel post under Government.” Although nothing comes of this, his mistress Mrs. Fisher uses her “interest” to get a promotion for Brian’s friend Captain Fascine. This is all related in a matter-of-fact way because this is how you get ahead in Regency England. No-one condemns it. I think Austen, likewise, treats the question of interest and promotion as a fact of life in Mansfield Park, though some have claimed to find hidden hints that she criticized the status quo. We might note that Jane’s father applied to anyone of influence in his personal network to help advance the naval careers of his sons and the family rejoiced whenever they did advance. A fact of life.

Nothing come of that scheme. Brian continues to gamble and he becomes entangled with a duchess behind Charlotte's back. Is this an attempt at creating a Tom Jones-like scenario? He is also shown as a kind-hearted person who performs acts of generosity and heroism. Rewards, in the form of useful coincidences, arise from Brian's actions. He helps a poor widow and the lodger at her house turns out to be a helpful ally. And no prize for guessing that the two young ladies Brian rescues from a runaway carriage are Charlotte and her friend Miss Thrum. Through various clumsy plot contrivances, Brian gains back the good will of the Hewsons and his own father, while he accumulates enough money through gambling to launch a respectable career as a banker.

Con man as hero Moral ambiguity

Con man as hero Moral ambiguitySo Brian is redeemed without having to go through much suffering. Any redeeming features to this novel? Academics might find it interesting as an example of a novel where the main characters (Brian and especially Verjuice) are of humble birth, and the merchant class is treated with respect while the high-born are mostly foolish or venal and where the parents of the two loving couples let their daughters marry for love. Charlotte's brother, who reforms himself and apologizes for drawing Brian “into the vortex of his dissipation,” comes back to England with a Spanish heiress. The fact that she is Roman Catholic is not an issue. Therefore you could argue that this novel champions social equality, companionate marriage, and an end to religious bigotry. However, I don't think we can credit Barrett with trying to inject liberalism into the sentimental novel. I think his aim was to write a whimsical, picaresque tale with more realistic moral ambiguity than one finds in most English novels of the period.

I always take note of any references to slavery and there are none in this novel. Two West Indians are mentioned only in connection "with the idea of rum, sugar, indigo, cotton, [which in turn] begets that of wealth, [therefore] the new comers instantly attracted the side-glances of the [other gamesters].” They turn out to be not West Indians at all but disguised professional sharpers.

If you are interested in Regency slang, this novel abounds with it. Mrs. Fisher suggests that Brian “take a ride,” meaning, that he turn highwayman. “Have you not been a gamester? And that, I am sure, is the worst calling of the two.” She also dismissively calls her former lover, the one she rejected for Brian, a “scrub.” She don’t want no scrubs. Mrs. Fisher is not punished by the author for being a fallen woman. She does not die of remorse. In fact she moves up in the world, becoming the mistress of H___ R______ H______. Some attention is paid to the Napoleonic wars and the disruption it caused to merchants.

George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent, aka H____ R______ H______ About the author

George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent, aka H____ R______ H______ About the author"Cervantes Hogg" is the pseudonym of Eaton Stannard Barrett (1786–1820), an Irishman whose writing career focused on political satire in prose and verse. Though Metropolis didn't draw any notice, some of his other publications did. The Rising Sun (1808) drew a scathing review from The Satirist, or Monthly Meteor: “This wholesale dealer in scandalous anecdotes… presents himself to the world as a Satirist, armed in the cause of virtue, and ready to combat the monster vice, in all its horrid forms. If to display vice, in her most disgusting undress, be to serve the cause of virtue, he might indeed boast of being her champion…[b]ut indeed, to enumerate all the gross depravity which fills up the first volume, would be to make ourselves accomplices in this outrage against decency.” An old book catalogue describes The Rising Sun as "A severe satire on George IV, when Prince of Wales, and most of the leading characters of the period.” The Royal Collection Trust has a copy, perhaps thumbed by George himself. Novels like Metropolis which excoriated the upper classes and even included satirical portraits of real people were a popular sub-genre, after the runaway success of the novel A Winter in London (1806).

Barrett had one best-seller: The Heroine, or: Adventures of a Fair Romance Reader (1813), based on the trope of girls thinking that novels are just like real life. See also Charlotte Lennox's The Female Quixote (1752). Jane Austen loved both of these books and Northanger Abbey is her entry into this sub-genre.

Wikipedia states, "little is known of Barrett's life. He appears to have died of tuberculosis in 1820, and yet he is mentioned as an author in a publication called The American Farmer, printed in Baltimore and dated 1823. Given his reported financial difficulties, it is possible, though unproven, that he fled to America to escape his debtors. His death was recorded in The Ladies' Monthly Museum, as having taken place in Glamorgan."

Hogg/Barrett explicitly editorializes against gambling for women: “The disgusting influence of this sordid vice is so pernicious to female minds, that they lose their fairest distinctions and privileges, together with the blushing honours of modesty and delicacy: a female mind deprived of these jewels, is one of the most desolate scenes in the world; and the ruinous consequences of gaming have already materially affected the character and deportment of the gentler sex; already the finest qualities of womanhood are perishing under its blast…”

Hogg/Barrett explicitly editorializes against gambling for women: “The disgusting influence of this sordid vice is so pernicious to female minds, that they lose their fairest distinctions and privileges, together with the blushing honours of modesty and delicacy: a female mind deprived of these jewels, is one of the most desolate scenes in the world; and the ruinous consequences of gaming have already materially affected the character and deportment of the gentler sex; already the finest qualities of womanhood are perishing under its blast…”This is a question sometimes discussed in Austen circles: are we supposed to believe that Mr. Knightley, Mr. Darcy, and all the other heroes, are virgins? If they are not virgins, then their choice of sexual partners would be limited to willing women of their own station (adultery or perhaps a merry widow), servants and girls from the lower classes (abuse of power), prostitutes or kept mistresses.

Previous post: Charles, the priggish hero

Published on October 26, 2023 00:00

October 19, 2023

CMP#157 Charles, the Priggish Hero

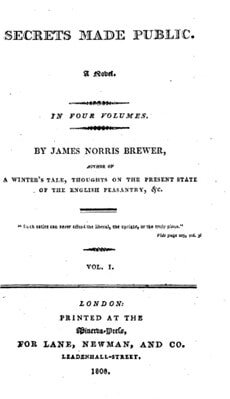

CMP#157 Secrets Made Public by James Norris Brewer, a first review for an 1808 novel This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

CMP#157 Secrets Made Public by James Norris Brewer, a first review for an 1808 novel This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

Author James Norris Brewer uses lecherous Methodists and radical freethinkers to liven up his tale of star-crossed lovers who get married in the third volume and have some more problems to sort out in the fourth volume in addition to uncovering the Big Secret that is quite obvious from the first volume. The narrator's voice is sardonic, while our hero and heroine indulge in the highest flights of exquisite sensibility. Consequently, the novel is an odd mix of overblown sentimental language, interspersed in a rather discordant way with the author’s animadversions on Mary Wollstonecraft, Methodists, social climbers and other bees in his bonnet, such as the drinking habits of Oxford scholars.

Author James Norris Brewer uses lecherous Methodists and radical freethinkers to liven up his tale of star-crossed lovers who get married in the third volume and have some more problems to sort out in the fourth volume in addition to uncovering the Big Secret that is quite obvious from the first volume. The narrator's voice is sardonic, while our hero and heroine indulge in the highest flights of exquisite sensibility. Consequently, the novel is an odd mix of overblown sentimental language, interspersed in a rather discordant way with the author’s animadversions on Mary Wollstonecraft, Methodists, social climbers and other bees in his bonnet, such as the drinking habits of Oxford scholars. The heroine, Ellen Fitzjohn, was left in the hands of strangers as a newborn. Her mother was a soldier’s wife who died giving birth while travelling with her husband's regiment; the distraught husband was forced to march away to embark for the East Indies. (This soldier, everybody notes, has the air of a gentleman and not a common private.) Baby Ellen fortunately catches the eye of the local baronet, a lonely widower. He adopts her and raises her as his own daughter.

Ellen grows up to be beautiful and virtuous. One day she goes to a nearby river to go fishing with an old family retainer; the bank gives way and she is swept off to certain death by drowning but luckily, a handsome youth who lives nearby leaps in and rescues her. With such an introduction, it is inevitable that Ellen and Charles Balfour fall in love...

Troublemaking widow Cast of Characters

Troublemaking widow Cast of CharactersEllen is devoted to her old guardian, Sir Octavius Langdale, but it’s more of a challenge for Charles to display filial piety toward his own father. His eccentric, taciturn dad is the second son of a wealthy family. The oldest son married against his father’s wishes, then joined the army, and nobody is quite sure what happened to the errant couple after that, with suspicion falling on Charles’s father, who inherited the estate.

There’s some Northanger-like speculation here: surely, an English gentleman could not commit such a dastardly crime as to do away with his sister-in-law and her child, the true heir? Could he? “In this free and happy island, the Baron’s castle no longer contains dungeons, or harbours mystery and assassination. The actions of both high and low, however vindictive may be the temper of the one, or refractory that of the other, are performed, without reserve, in the open face of day. But, according to the tenor of his accusations, here stood a man of English birth, born to the customs of freedom and the openness of honour, who had stained the character of his country, by descending to worse than Neapolitan intrigue.”

But—if Mr. Balfour didn’t kill his sister-in-law and her baby after his older brother joined the army under a fake name and disappeared, then what became of them? It’s a real mystery.

Meanwhile, there’s a newcomer to Sir Octavius’s home. Mrs. Fortescue, the daughter of his late wife’s best friend, “not yet four-and-twenty,” who is received “with paternal kindness” after she is widowed. Mrs. Fortescue sets about trying to corrupt the ideals of young Ellen, because she--gasp—is a disciple of Mary Wollstonecraft, who comes in for quite a walloping in this novel.

(A reminder that after Mary Wollstonecraft died, her husband William Godwin published her biography, which caused a scandal with its frank disclosure of her personal life , including her illegitimate daughter, her suicide attempts, and her brief but intense obsession with a married man. At the time Secrets Made Public was published, Mary Wollstonecraft was persona non grata with respectable men and women.)

“O may the day at length arrive when woman shall attain her due rank in the social compact!” [Mrs. Fortescue exclaims to Ellen] “When the writings of her who boldly stepped forward the champion of her sex—the exalted author of the Rights of Woman—when those lines of eloquence and truth shall be copied in letters of gold!—I fear, my dear, that divine work, the Rights of Woman, has never been put into your hand.” Mrs. Fortescue also refers to the opinions of the Comte de Volney on prayer, a hint that she disbelieves the Christian religion, and like Mary Wollstonecraft’s husband, she thinks the institution of marriage is a prison: “Can anything be more preposterous than the prescribing of human laws for the conduct of natural affections?... Can human laws dictate its progress to the sentiment of the heart? Is there not—now tell me candidly—something ridiculous in the modes of courtship and of union observed between the sexes? –The lady must not feel a passion before the gentleman avows his; and having once received his addresses, she must like him better than every other man in the world; while, to complete the catalogue of contradictions, the natural affection of the couple must not… attain the summit of its climax, till certain forms have told it that it may proceed!”

Luckily for her virtue, Ellen disregards this dangerous nonsense.

Charles is disillusioned when he goes to Oxford ' To round out the characters, we must mention the son of Sir Octavius. Robert Langdale is a wastrel and a ne’er do well, who cares only for horses, hounds, and the hunt. Yet Sir Octavius decides that Robert and Ellen should marry, and his generous bequest to Ellen is based on his assumption that she'll marry Robert. Ellen secretly loves Charles Balfour, but she tries to steel herself to obey her guardian’s injunction. “Forlorn and unfortunate that I am!” cried she, “how shall I tell my only friend, when he expects from me the obedience which he is entitled to exact—how shall I tell him that a passion has stolen into my breast, which would render obedience criminality? And a passion nurtured on unhallowed, chimerical grounds; yet which has power to sway my whole soul, and banish every other feeling, save those of honour.”

Charles is disillusioned when he goes to Oxford ' To round out the characters, we must mention the son of Sir Octavius. Robert Langdale is a wastrel and a ne’er do well, who cares only for horses, hounds, and the hunt. Yet Sir Octavius decides that Robert and Ellen should marry, and his generous bequest to Ellen is based on his assumption that she'll marry Robert. Ellen secretly loves Charles Balfour, but she tries to steel herself to obey her guardian’s injunction. “Forlorn and unfortunate that I am!” cried she, “how shall I tell my only friend, when he expects from me the obedience which he is entitled to exact—how shall I tell him that a passion has stolen into my breast, which would render obedience criminality? And a passion nurtured on unhallowed, chimerical grounds; yet which has power to sway my whole soul, and banish every other feeling, save those of honour.”Charles meanwhile has been packed off to Oxford, which he enters with great enthusiasm: “'Hail!' cried he, 'ye venerable abodes of all that can dignity the mind of man, of all that purifies nature and exalts intellect! –Great treasury of human wit! Sublime depository of lettered research, all hail! –Taste, science and art, combine to embellish your retreats, and sanctify each august cloister! Spirits of Newton, of Bacon, of Locke, of Johnson! Do ye not dwell, with paternal rapture, amid these hallowed domes? –Oh, bowers consecrated by the visions of the poetical, by the reflections of the philosophic, I recognize you with aspiring pride, and triumphantly profess myself one of the most emulous of your votaries!'”

Disappointment follows, as Charles discovers every gathering of scholars is devoted to drinking and making stupid puns and dirty jokes, and everybody thinks he's a nerd.

Best-seller: Children of the Abbey The tribulations of Ellen

Best-seller: Children of the Abbey The tribulations of EllenAfter Sir Octavius dies, the scheming Mrs. Fortescue abandons her advocacy of Free Love in favor of becoming a baronet’s wife, and she cajoles Robert to the altar. In losing her unwanted fiancé, Ellen loses the home she grew up in, and her bequest from Sir Octavius. She then, in the manner of sentimental heroines thrown on hard times, is forced to seek shelter in the homes of objectionable people—in this case, the guardians appointed by Sir Octavius’s will. They are vulgar merchants whose vast income comes from trade. But the titled people she meets are also objectionable. Ellen spends some unpleasant few weeks in London, fending off the advances of a stuttering Marquis who is described as a Methodist but he is a lying lecher.

By way of seduction, he asks her [The stuttering, of course, is for comic effect]: “'[D]i-di-di-did you ever read the Children of the Abbey?' 'No, my Lord!' replied she, averting her face, with unqualified disdain. 'The-the-then you have a great pleasure to come,' said he, 'de-depend on it.'" Later, the Marquis ambushes our heroine in the library and assaults her, raining down kisses on her virgin lips and bosom. His Methodist servant enters and blames her, accusing her of seducing his master “like Potiphar’s wife,” but her servant Betty comes to the rescue and sees the Marquis off before the worst occurs.

Luckily, Ellen meets up with her true love Charles, who must attend the courts in London at the behest of his father because of a mysterious overseas plaintiff who is bringing a court challenge against his claim to the family estate (Hmm, whatever did become of that missing older brother? Hmmm.) Charles’s father suddenly allows him to marry the dowerless Ellen, after keeping the lovers apart for years, and at the end of the third volume the couple live happily in the countryside in Wales. But this is not the end of our tale. The author says he is "entitled to the praise of novelty" for extending the story beyond the wedding. To set up for the fourth volume, Charles and Ellen are told they must move to the environs of London because of the ongoing court troubles. Here is Charles’s speech on the occasion: “My dear Ellen!... we must cultivate in our own bosoms the germ of genuine felicity which renders the pomp of courts, or the simple quiet of the cottage, the glittering splendours of the city, or the more precious charms of rocks, vales, and woods, like these--every extraneous circumstance—objects alike of secondary moment, or only transient importance.”

The village of C_____ Big Secret Reveal!

The village of C_____ Big Secret Reveal!The first part of the fourth volume is given over to a satirical portrayal of the vulgar citizens of the suburb of “C_____, a village of some notoriety in the modern maps of London and its environs.” The author evidently means to lampoon a real place and real people. It's interesting he comes down so hard, and at such length, on people from the mercantile classes because surely there are many novel-readers in their ranks: “Ellen soon found that the company of those persons who composed the major part of the village, was peculiarly disgusting to a mind blest with intelligence, and habituated to the society of the polished and urbane. The insolence of newly-acquired wealth among the low-born and illiterate, is too well known to need delineation; and Ellen, in this populous neighbourhood, saw it in all its various modifications…”

The lovebirds have each other, anyway, until the Methodists and Mrs. Fortescue (now Lady Langdale) team up to attack them. (Robert is busy drinking himself to death and Lady Langdale is carrying a torch for the dishy Charles.) They manage to fool Charles into thinking Ellen has been unfaithful and he treats her horribly. I thought he was a rather ridiculous windbag before, and he really lost me here: “O derogate soul of humanity! To what depths canst thou sink, when in so fair a form, in so bright a semblance of perfection, thou thus easily accomadatest thyself to the burthen of vice, to the loathsome trappings of hypocrisy!”

The misunderstanding is cleared up, Ellen is vindicated, she instantly forgives Charles--even though the shock of his cruelty almost killed her--and finally the big Secret is made Public. In fairness to the author, I will say he managed to fool me as to the real identity of an older man who shows up in the fourth volume to rescue Charles and Ellen’s child from a runaway horse. Surely, I thought, this is the long-lost father of Ellen? No, it wasn’t.

However, yes—the big Secret is that Ellen and Charles are cousins (but of course that’s not an issue). She’s the daughter of Charles's long-lost uncle, who now calls himself Colonel Vansittart, for some reason. He thought his child had died at birth. He's another example of how authors of this time sent characters to the East or West Indies to have them out of the way until they were needed for plot purposes. Looking at you, Sir Thomas.

Abolitionist author

Abolitionist author Anti-slavery is certainly not a central theme of this novel, but James Norris Brewer (1777-1839) comes out swinging against it in a brief passage in the middle of his wrap up about who gets the Langdale estate: “five thousand acres, spread beneath the burning sun of the cane-islands, and fifteen hundred negroes, condemned to daily toil on the sanguinary plantations, shall be deposited, in the shape of a parchment title-deed, in the iron-chest of Willoughby Bronze, Esquire, and planter, of the island of Jamaica; and in the next, 'presto, begone!' the land, the negroes and every thing (except the title deed), shall be conveyed, by a single fall of the hammer, into the pocket of John Brown, stock-broker or army-agent, and esquire by courtesy of his accommodating country.”

Willoughby Bronze is not a character in the story, and appears to be a name representing all gentlemen plantation owners, who, objectionable as they are, are not as objectionable to James Brewer as upstart social climbers who acquire enough money to buy plantations.

Earlier in the story, Charles is sent by “the mandate of his father... to an estate in the western plantations, under the pretence of that part of the family property requiring the immediate inspection of a person interested in its successful regulation.” I presume this is a reference to a West Indian plantation. The author also says Charles would rather be poor than have his father's tainted West Indian money: “still he retained, in all its fervour, that glowing sentiment, which bade him prefer honourable penury to injustice coupled with the wealth of empires.” Which, after all, is more than Edmund Bertram ever says in Mansfield Park.

Brewer wrote at least eight novels and contributed to a number of travel guide books. His wife came from Clapham (Clapham, a village near London starting with C?). Perhaps Brewer was familiar with the abolitionists and social reformers known as the

Clapham Saints.

Brewer wrote at least eight novels and contributed to a number of travel guide books. His wife came from Clapham (Clapham, a village near London starting with C?). Perhaps Brewer was familiar with the abolitionists and social reformers known as the

Clapham Saints.

Secrets Made Public was not reviewed in its time. Someone offered an anonymous review to The Universal Magazine but the publishers refused, “upon the principle of never admitting any criticisms upon books without a knowledge of the writer” so we’ll never know if the anonymous reviewer was filled with praise or criticism for the work. We might note that Brewer was himself a contributor to The Universal Magazine.

Secrets Made Public might interest academics studying Mary Wollstonecraft's reputation in the decades following her death, and the way Methodists were portrayed in fiction in this time, and it is another entry in the list of novels which criticized slavery. The author's preface (which also appeared as an article in The Universal Magazine) gives advice on how to write a novel and defends novels as vehicles for moral instruction: “It would be difficult, I believe, to find one English Novel which does not endeavour to exhibit, in its catastrophe, the beauty of virtue and the deformity of vice.”

"Catastrophe" was used by some people the way we'd use "climax" or "denouement," which is kind of fun. I will say that Brewer attempts to tie his characters and episodes together and use his satiric characters in the plot, as opposed to being walk-ons for entertainment. He's trying to create a story in which all of the elements tie together, but blending a conventional sentimental novel with extended passages of social criticism made me wonder who the intended audience was. Previous post: Harriot the resourceful heroine For more examples of the critical way Methodists were portrayed in novels of this era, see my earlier blog series. Here are more examples of authors who spoke out against slavery.

The anti-novel attitudes of sentimental heroines, as famously discussed by Austen in Northanger Abbey, is a funny and recurring feature in novels of this era. James Brewer's heroine disdains to read The Children of the Abbey. Harriet Smith approvingly mentions The Children of the Abbey in Emma: [Robert Martin] “never read the Romance of the Forest, nor The Children of the Abbey. He had never heard of such books before I mentioned them, but he is determined to get them now as soon as ever he can.”

"The Children of the Abbey was one of the most enduringly popular Minerva novels; published in 1796, it had reached its tenth edition by 1825 and was still in print in 1882." (Howells, Coral Ann. Love, Mystery and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.) Brewer's plot does not rise to the Gothic heights of The Children of the Abbey. His villains are motivated by their faulty ideological beliefs, and Charles's father, while a very flawed individual, is not a murderer. Like Austen, he rejects the wilder, more fanciful conventions of the gothic.

People often talk about the parents in Austen (such as the flawed Mr. Bennet and the self absorbed Sir Walter Elliot) and how few fond mothers there are in her works. Some ask, what is it with Austen and parents? It seems to me that authors of this period simply killed off parents who weren't essential to the plot. Sometimes their death, as in the case of Ellen's mother, is the inciting event.

Here's the passage from Northanger Abbey in which Austen talks about the heroines of novels refusing to read novels. She's absolutely right, and it shows Austen's familiarity with the novel tropes of her day: Yes, novels; for I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding—joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard?

Published on October 19, 2023 00:00

October 11, 2023

CMP#156 Harriot, the Resourceful Heroine

I read The Duped Guardian as part of my research into references to Lord Mansfield for my

backgrounder series

about Mansfield Park as a possible

allusion to Lord Mansfield

and the Somerset case. about how I explored the possible connection. This 1785 book contained a mention of "Mr. Mansfield," but I discovered it referred to a different lawyer named Mansfield, so I did not include this novel in my list of novels which mention Lord Mansfield. Here is my book review anyway. CMP#156 The Duped Guardian (1785), by Mrs. H. Cartwright, with bonus rabbit hole

I read The Duped Guardian as part of my research into references to Lord Mansfield for my

backgrounder series

about Mansfield Park as a possible

allusion to Lord Mansfield

and the Somerset case. about how I explored the possible connection. This 1785 book contained a mention of "Mr. Mansfield," but I discovered it referred to a different lawyer named Mansfield, so I did not include this novel in my list of novels which mention Lord Mansfield. Here is my book review anyway. CMP#156 The Duped Guardian (1785), by Mrs. H. Cartwright, with bonus rabbit hole

Shocking revelations for our heroine There are actually two duped guardians in this brisk two-volume tale. There are two heroines: both orphans, both heiresses, both controlled by guardians appointed by their late fathers’ wills. Both guardians want to keep the handsome inheritance and dispose of the girl quickly. There are two interlaced plots: one is all melodrama, the other is fairly comical (and in fact was "borrowed" from a comic play ).

Shocking revelations for our heroine There are actually two duped guardians in this brisk two-volume tale. There are two heroines: both orphans, both heiresses, both controlled by guardians appointed by their late fathers’ wills. Both guardians want to keep the handsome inheritance and dispose of the girl quickly. There are two interlaced plots: one is all melodrama, the other is fairly comical (and in fact was "borrowed" from a comic play ). Mrs. Cartwright orchestrates a story in which perils arise, and problems are resolved in a graceful and orderly fashion, like people dancing a minuet. Although there is drama, there is no great feeling of despair or tension, and this might be because the heroine, Harriot Pelham is intelligent and resourceful. She and her sidekick friend Lady Laura Antrim don't lose their heads or faint in a crisis, but rise to the occasion with female solidarity.There is a secondary heroine, Clara Aubry, a Harriet-Smith-like picture of ignorance, only fifteen years old, of whom one character says: “innocence, when it is accompanied by a naïve goodness of heart, has charms irresistible.” Given Clara's imbecility, Harriot needs an intelligent friend and confidante to write her letters to (since this is an epistolary novel), which is where Lady Laura comes in. She's the saucy sidekick of the story. They both look out for Clara.

Harriot‘s guardian is her brother-in-law, Mr. Hoyle, with whom she lives, along with her older sister Caroline. Let’s plunge into the action: Thanks to a carelessly dropped letter, Harriot discovers that Mr. Hoyle is conspiring with a female panderer to abduct her, take her to a secluded mansion, rape her, and then stick her in a convent when he’s tired of her. Then he'll take her inheritance. She is determined to avoid distressing Caroline by revealing that her husband is a monster, so when she’s caught weeping, she pretends that she’s been crying over the pages of a tragedy. This brings a gentle rebuke from Caroline about indulging in “fictitious misery,” a reference to the common trope that novel-reading was harmful.

After the initial horrible shock, Harriot pulls herself together...

Laura refers to some current events, including the first hydrogen balloon flight. Spoilers follow

Laura refers to some current events, including the first hydrogen balloon flight. Spoilers followHarriot resolves to take her pin money and live in seclusion under an assumed name in the countryside until she comes of age and can control her own fortune. With admirable sang-froid, she sneaks away with her wardrobe, art supplies, and even her guitar, before anybody realizes she’s gone. This is certainly more prudent than the escapes conducted by some other heroines who flee with only the clothes on their back and hardly a sixpence to their name.

The farm couple are also, by coincidence, providing a home for the sweet and artless Clara. Clara has been left in the country to grow up ignorant not only of society, but also of basic literacy. Dr. Lovegold, her avaricious guardian, and Lord Wormeaten, the subtly-named lecherous old nobleman he plans to marry her to--think women are easier to control if they are ignorant. Harriot promptly sets about teaching Clara how to write and sketch. She also befriends a little neighborhood boy, the neglected son of an unlikable widow. Harriet stays in touch with her friend Laura by letter, filling her in on what's happening.

Dr. Lovegold shows up at the farmhouse and takes her back to his home in anticipation of her marriage to old Lord Wormeaten. On their trip home, a dashing young hero named Charles Luttrell spots Clara going by in her carriage and falls instantly in love with her. He pretends that he’s dying of consumption, so he can gain entrance to the doctor’s house and court Clara. End of Vol. 1. All Will Be Revealed

Since this is an epistolary novel, we get our information when one character writes an extremely detailed letter explaining what is going on to some other character. But these individual characters have limited knowledge of the whole picture, which Mrs. Cartwright tries to make the most of. Thus, Charles Luttrell decides that his friend Lady Laura would be the perfect person to shelter Clara until she’s old enough to get married, but he doesn’t realize that she lives with the lecherous Lord Wormeaten. While this limited knowledge adds to the suspense, it sometimes just ends up making everyone look extremely obtuse. (“You say you’ve met a beautiful young girl who's about to be forced into marriage with an ancient nobleman? What a coincidence! My guardian, an ancient nobleman, tells me he’s about to marry an innocent young girl.”)

Just desserts for the bad guys What about Harriot?

Just desserts for the bad guys What about Harriot?Meanwhile, what of Harriot? When Harriot fled her sister’s house, she left a note letting her foul brother-in-law know that she was on to his diabolical scheme. He therefore has a strong motive to track her down and hush her up. By a lucky chance she learns that one of the unlikable widow is her brother-in-law’s accomplice. Harriot high-tails it out of the farmhouse before the two of them can snatch her. She seeks refuge in a convent in France.

The introduction of a convent into the narrative apparently obliges the authoress to drop in an extended editorial from Harriot on the superstitions and errors of the Catholic faith and the hypocrisy and avarice of Abbesses. I suspect it’s nothing personal, Mrs. Cartwright is just checking the boxes here. The real reason that the author has whisked Harriot across the Channel is because it provides a convenient way to kill off the evil brother-in-law and his accomplice. They pick up on her trail, hire a boat to follow her, and drown in a storm.

Harriot is now free to go back to her sister—who will never learn about her husband’s true nature. Meanwhile Clara has placed herself under the protection of Charles Luttrell, the man who loves her, who is—coincidentally—Lord Wormeaten’s nephew and his heir. Luckily, Lord Wormeaten is very good about the whole thing. The threat that he has posed through the whole book suddenly dissolves when he realizes he's been ridiculous to want to marry a child bride at his age. He urges Charles to marry Clara before he, Lord Wormeaten, dies so he can bless their union. Charles, by the way, did express his scruples about scooping up a fifteen-year-old heiress before she’s had a chance to look around her, but, satisfied that she loves him, and with the encouragement of his uncle, they marry.

Laura, the saucy sidekick, also marries the man of her choosing without any opposition, and all’s right with the world. Oh--wait a minute, what about Harriot? Although she has someone who loves her, Edwin Solmes, he’s not given a chance to do anything heroic, and Harriot, according to novelistic convention, is not allowed to confess her love for him. We don’t meet him until near the end of the book and we don't learn anything about him except that he's very pleased to see Harriot again. He "run'[s] on with such a rhapsody of thanksgivings” to the “Almighty Disposer of Events,” that Harriot jokes “it’s a doubt with me, Laura, whether the youth is not turned Methodist .”

Yes, as a novel, The Duped Guardian is deficient. Dramatic impediments are set up, and then waved away. But if Jane Austen wrote a story like this, the modern critical reaction would be to regard it as a protest novel--a feminist manifesto against the laws that kept females under subjugation to their parents and guardians and a bold argument for female education. The critics would extol the tale because it downplays the love stories in favor of showing our two female best friends capably handling a variety of crises. (For another novel of this type, though far more convoluted, try The Gypsy Countess ). Harriot even has the time and compassion to sponsor her late brother-in-law's illegitimate child, now orphaned because of the shipwreck. In addition to showing female agency in the face of patriarchal oppression, the novel features a minor subplot about a nobleman who marries a girl of humble birth for love alone.

Sir James Mansfield. Not THAT Mansfield.

"Mr. Mansfield is to abdicate his reign"

Sir James Mansfield. Not THAT Mansfield.

"Mr. Mansfield is to abdicate his reign"

I only opened this book to check out the reference to a “Mr. Mansfield” which appears in Volume I, and I ended up reading the whole thing. It was breezy good fun.

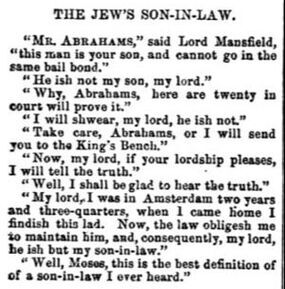

Now, what does Laura mean by her passing reference to “Mr. Mansfield”? I'm sure it's a saucy reference because she's the saucy sidekick. She tells Harriot that Lord Wormeaten wants her out of the house before his new bride arrives “for fear I should endeavour to inculcate more fashionable propensions on her inexperienced mind, it is a determined point that I should never see her; to which end, he has very genteelly desired me to accommodate myself with some other friend till the arrival of that period, when Mr. Mansfield is to abdicate his reign, and my ladyship is in possession of the family Mansion.” [italics in original]

Mr. Mansfield is not a character in the book. It appears to be a reference to a real person whom the readers would know. But it's not Lord Mansfield, because Lord Mansfield was never “Mr. Mansfield.” His name was William Murray and Mansfield is the name of first, his baronial title, and then his earldom. Therefore, no one would refer to him as “Mr. Mansfield.”

I think Laura is referring to James Mansfield (1734 -1821), who was an eminent British jurist who served as a lawyer, a judge, as solicitor-general (at the time of this novel), and as an MP. His career overlapped that of Lord Mansfield.

Frances Mary Harford by Romney Ripped from the headlines

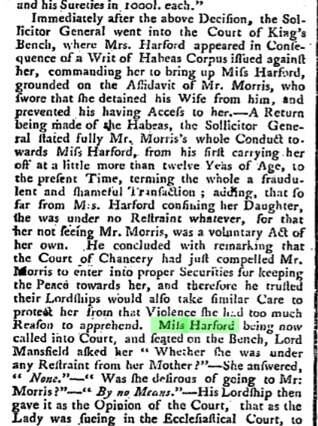

Frances Mary Harford by Romney Ripped from the headlinesAnd I think I've discovered what the reference to abdicating his reign means. Laura is saying that when young Clara is brought to Lord Wormeaten's house, no-one will protect her from being pressured into marriage. Lady Laura is alluding to a recent sensational court case in which James Mansfield, as Solicitor-General, protected the rights of a young heiress named Frances Mary Harford, the illegitimate daughter of Lord Baltimore. Lord Baltimore had left Frances 30,000 pounds, which is the same amount that Clara Aubry has in the novel.

Robert Morris, a thirty-year-old barrister, and one of the executors of Lord Baltimore's will, took young Frances out of her boarding school by claiming to be her guardian and he fled with her to Europe when she was only twelve-and-a-half. “The tender years of Miss Harford, her innocence and unsuspicious temper, Mr. Morris took advantage of, by intoxicating her little head with notions of fine buckles, Ranelagh and masquerades." Moving from place to place, Morris arranged for two hasty wedding ceremonies. Once she came of age, and presumably regretted what happened, her foreign weddings were declared null and void because she had been underage and the weddings would not have been considered legal in the countries in which they were held. Frances was legally freed from Mr. Morris in May, 1784 and she remarried two months later and lived abroad with her second husband, a diplomat.

This provides an example that not all mentions of the name "Mansfield" have to do with Lord Mansfield or Somerset v. Stewart, even when law cases are involved.

Elizabeth Younge Pope, who played the role of the saucy Miss Archer in "More Ways Than One." About the author:

Elizabeth Younge Pope, who played the role of the saucy Miss Archer in "More Ways Than One." About the author:Mrs. H. Cartwright (dates of birth and death unknown) wrote a book about female education, a hot topic at the time, as well as several novels and essays. The Orlando database of women writers says she is “otherwise unidentified." The Feminist Companion to Literature in English notes that Mary Wollstonecraft threw shade at Mrs. Cartwright's novel The Platonic Marriage in her own novel, Maria. Ernest Albert Baker, in his 1936 History of the English Novel, describes Mrs. Cartwright as “an indifferent specimen of the third rate” among novelists of her era. I will say in her defense that heroines showed pluck, so I put her amongst the proto-feminists. I mean, if we are going to praise Austen as a feminist because she has Anne Elliot observe to Captain Harville that women "live at home, quiet, confined," then surely this tale of two women who thwart the criminal behavior of some powerful men deserves a mention.

The Duped Guardian received two short and half-hearted reviews. The Monthly Review said: “the work is neither tedious nor insipid; it may afford amusement to please an idle mind, and instruction to warn a thoughtless one.” Note that nobody said, "But whoa, there's a bit too much anti-patriarchal stuff in here."

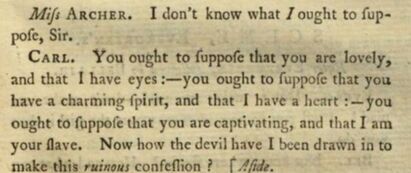

The Critical Review pointed out that Mrs. Cartwright borrowed her plot about Clara, “the artless niece of the artful physician,” from “Mrs. Cowley’s last comedy, viz. ‘More Ways Than One.’” That appears to be the case. In the 1783 play, a suitor pretends to be sick to win the heart of Arabella, the ward of Dr. Feelove, who is trying to get her married off while holding on to as much of her 30,000 pound fortune as he can. The play's Mr. Evergreen became the novel's Lord Wormeaten, and saucy sidekick Miss Archer became saucy sidekick Laura Antrim. It is interesting how freely people borrowed plots and ideas from one another in this era, when they weren't openly plagiarizing.

Ladies, get you a man who says he's your slave: More Ways Than One Mentions of slavery & colonialism

Ladies, get you a man who says he's your slave: More Ways Than One Mentions of slavery & colonialism The only mention of “slave” in The Duped Guardian is the typical declaration, made by the male lover, that he is the "slave" of his mistress, and the only mention of colonialism is when more than one character uses the phrase, not for the wealth of the Indies would I do such-and-such. No-one appears to have a colonial fortune.

Previous post: Mansfield and the cultural discourse *More on Sir James Mansfield Sir James Mansfield is connected to the Somerset v. Stewart case because he was one of the lawyers for the enslaved man Somerset! A 19th century biography tells us: “Though Sir James Mansfield was not engaged in many great trials, he was yet employed in two of the celebrated causes of his time; one involving a political principle and the other a great social evil.”

The Somerset case was not the “great social evil” or the “political principle.” The “political principle“ refers to an action brought by radical politician John Wilkes “for false imprisonment,” and the “great social evil” refers to bigamy. Mansfield defended the “Duchess of Kingston, when that singular lady was tried by the Peers for bigamy, in 1776.” The Somerset case was not even worth mentioning as one of the “celebrated causes of his time.”

The Somerset case dates from 1772, and though this landmark case might be well-known to every well-educated Janeite today, it doesn’t necessarily follow that in the years and decades following 1772, Somerset v. Stewart was the first thing that popped into people’s minds whenever the name “Mansfield” arose, as I've discussed in previous posts.

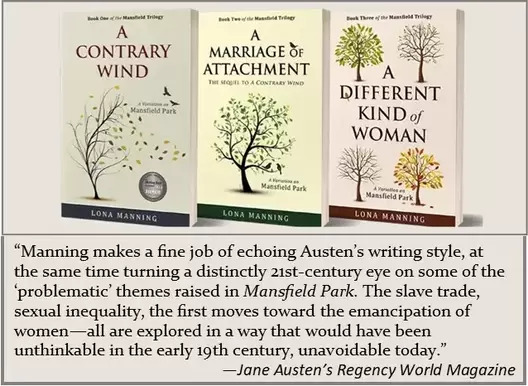

Sir James Mansfield also presided over the trial of John Bellingham, who was convicted for assassinating Prime Minister Spencer Percival in the House of Commons lobby on May 11, 1812. Bellingham, not surprisingly, was sentenced to death, even though questions were raised about his sanity. Bellingham appears as a character and the Percival assassination features in my second novel, A Marriage of Attachment.

For more about my books, click here.

Robert Morris brought a court action attempting to force his (now grown) child-bride to be returned to him. James Mansfield, as Solicitor-General, put a stop to that.

Robert Morris brought a court action attempting to force his (now grown) child-bride to be returned to him. James Mansfield, as Solicitor-General, put a stop to that.

Published on October 11, 2023 04:34

October 5, 2023

CMP#155 Mansfield and the Cultural Discourse

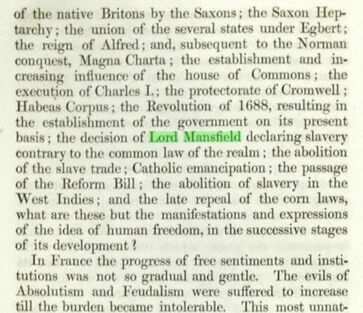

"I would suggest that [Austen] was quite deliberately gesturing at the cultural discourse that [Mansfield] represents, at his name’s indexical link to a particularly charged national moment... It is worth contemplating what Austen’s contemporaries would have understood that gesture to mean, given the reputational baggage of the name “Mansfield” in Regency zeitgeist and politics.

"I would suggest that [Austen] was quite deliberately gesturing at the cultural discourse that [Mansfield] represents, at his name’s indexical link to a particularly charged national moment... It is worth contemplating what Austen’s contemporaries would have understood that gesture to mean, given the reputational baggage of the name “Mansfield” in Regency zeitgeist and politics. -- Danielle Christmas, "Lord Mansfield and the Slave Ship Zong,"

Persuasions online Vol 1, number 2, 2021 CMP#155 Lord Mansfield and the Cultural Discourse

Granville Sharp helped the enslaved James Somerset bring his master to court I've been delving into digital archives to contemplate what "the reputational baggage of the name 'Mansfield'” in "Regency zeitgeist and politics," might have been. What was the "cultural discourse" around the name "Mansfield"? Yes, Lord Mansfield's rulings in Somerset and the Zong case might be a big part of our zeitgeist in Jane Austen circles in this age of racial reckoning, but as I have learned: the name "Mansfield" without any indication that it carried cultural baggage. It was just a

solid English name.

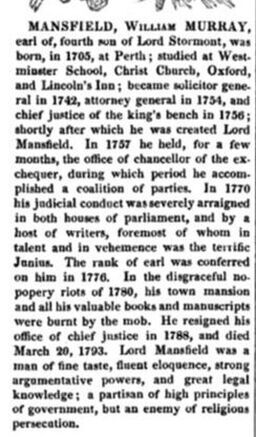

People referenced Lord Mansfield (1756–1788) in relation to many legal issues, including investments, insurance, libel, religious freedom, and so on, and made mention of his probity and patience. But it's not easy to find references to Somerset v. Stewart before 1840 in the popular literature. They probably exist, but I haven't found any. (I am not speaking of law books which are not read by a general public) So what would "Austen's contemporaries" have "understood that gesture" [of putting the name Mansfield in her title] to mean"? Based on my survey of digital archives. Lord Mansfield's rulings in the Zong case (1783) and the Somerset case (1772) were not a significant part of his posthumous reputation in the first half of the 19th century. Mansfield Park was first published in 1814.

Granville Sharp helped the enslaved James Somerset bring his master to court I've been delving into digital archives to contemplate what "the reputational baggage of the name 'Mansfield'” in "Regency zeitgeist and politics," might have been. What was the "cultural discourse" around the name "Mansfield"? Yes, Lord Mansfield's rulings in Somerset and the Zong case might be a big part of our zeitgeist in Jane Austen circles in this age of racial reckoning, but as I have learned: the name "Mansfield" without any indication that it carried cultural baggage. It was just a

solid English name.

People referenced Lord Mansfield (1756–1788) in relation to many legal issues, including investments, insurance, libel, religious freedom, and so on, and made mention of his probity and patience. But it's not easy to find references to Somerset v. Stewart before 1840 in the popular literature. They probably exist, but I haven't found any. (I am not speaking of law books which are not read by a general public) So what would "Austen's contemporaries" have "understood that gesture" [of putting the name Mansfield in her title] to mean"? Based on my survey of digital archives. Lord Mansfield's rulings in the Zong case (1783) and the Somerset case (1772) were not a significant part of his posthumous reputation in the first half of the 19th century. Mansfield Park was first published in 1814.

"Ich bin ein Berliner" What's your "Top of Mind" for John F. Kennedy?

"Ich bin ein Berliner" What's your "Top of Mind" for John F. Kennedy?Let’s take a more contemporary example: the reputational baggage of JFK. I’m old enough to remember when John Fitzgerald Kennedy was president. Though I was a young child, I remember the day of his assassination vividly. And I remember how people spoke of him and how his reputation gradually changed.

During the 60’s he was a secular saint. But what comes to mind now when someone mentions JKF? What is your top-of-mind association? That he was the first Catholic president? His inaugural speech ("Ask not what your country can do for you")? That brief shining moment known as Camelot? His glamorous wife Jackie? The Bay of Pigs? The Cuban Missile Crisis? The Vietnam War? His NASA pledge? His war record in WWII? His speech in Berlin? Little John-John saluting at his funeral? Or, do you think of his multiple extra-marital affairs? His sharing a mistress with a mob boss? The way his medical problems were kept a secret from the public? The Kennedy clan shenanigans in general? The evidence that his Pulitzer prize-winning book was ghostwritten?

if I saw a novel titled "Kennedy Park," I would expect the author to work in some reference to the allusion in the novel's denouement. I'd expect some kind of tie-in, not an allusion which is just left hanging there. I also would not expect that my top-of-mind recollection about Kennedy--or Mansfield--would be the same as everybody else's top of mind recollection. I will grant you that the fact of the Antigua plantation means there is a slavery connection which possibly connects to the title. But it's hard for me to believe that an author of her skill and polish would just leave the allusion hanging there.

Horace Walpole (1717–1797) Lord Mansfield's reputation when alive

Horace Walpole (1717–1797) Lord Mansfield's reputation when alive When Lord Mansfield was alive and serving in Parliament, he was a target for the political opposition. We don't need to become experts in Lord Mansfield and his career to appreciate the fact that, in common with all politicians, his motives and integrity were questioned, and his policies and his court rulings were attacked. The English radical Thomas Paine was dismissive of him: “The talents of Lord Mansfield can be estimated at best no higher than those of a sophist.”

Horace Walpole, English man of letters, apparently loathed Lord Mansfield. Walpole’s language suggests a political animus, and without delving deeper into the whole thing, I provide this quote simply to give a sample as evidence that Mansfield was not universally revered: “The dismay and confusion of Lord Mansfield was obvious to the whole audience; nor did one peer interpose a syllable in his behalf; even the Court (whom he had been serving by wresting the law, and perverting it to the destruction of liberty, and his guilt in which practices was proclaimed by his dastard conscience) despised his pusillanimity and meanness…” and much more in the same vein.

An anonymous writer named Junius conducted blistering political attacks on Lord Mansfield, but these occurred before the Somerset case, so there is no reference to them.

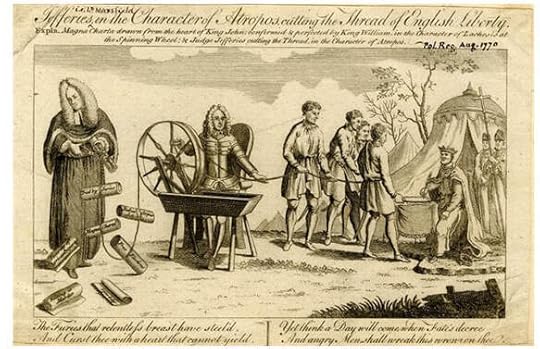

Mansfield was a well-known national figure long before his rulings on the Zong case and the Somerset case drew publicity in the ongoing abolition debate, so therefore his name was associated with many political and legal issues. Lord Mansfield, like all politicians, was satirized and attacked in contemporary political cartoons. The British Museum explains this cartoon as follows: "Satire on Lord Mansfield and his judgements allegedly undermining British liberty. The thread of liberty is drawn from the heart of King John and spun by William III (Lachesis, measuring the thread) so as to bind scrolls representing 'Habeas Corpus', 'Free Elections', 'Magna Charta', 'Trial by Juries', 'Bill of Rights' 'Security of private Property', 'Killing no Murder and 'Appeals', the last three having been cut from the thread by Lord Mansfield ('[Judge] Jefferies in the Character of Atropos') who now holds his shears against the 'Bill of Rights'. From the Political Register, 1770."

The Furies that relentless breast have steel’d, and curst thee with a heart that cannot yield

The Furies that relentless breast have steel’d, and curst thee with a heart that cannot yieldYet think a Day will come when Fate’s decree, and angry men shall wreak this wrong on thee. "Lord Mansfield is no lawyer"

Here is an 1781 editorial which opposes the Somerset case and calls Lord Mansfield a "republican" who "under the vile pretence of unalienable rights" has set a dangerous precedent which "deprives the master of his legal property."

Brief 1831 biography doesn't mention Somerset. Today even a brief biography of Mansfield would. Posthumous Reputation

Brief 1831 biography doesn't mention Somerset. Today even a brief biography of Mansfield would. Posthumous Reputation The first full-length biography of Mansfield came out five years after his death and was written by John Holliday: The life of William late Earl of Mansfield, 1797. It runs to more than 500 pages, and it does not mention "slave," "slavery," or "Somerset" in the the text or the index, although many other of his cases are discussed. Neither is the now-infamous Zong c ase mentioned. This biography came out in subsequent editions and years as well.

In between 1797 and the 1830's, you can find mentions of the Somerset case in relation to the abolitionist who spearheaded the campaign to bring the case to court: Granville Sharp. Here is a typical example. which quotes a memoir of Sharp. Sharp wanted posterity to remember his role in the case. But "Sharp Park" doesn't have the same ring to it as "Mansfield Park." As well, it is mentioned in accounts of famous trials.

Other, briefer biographies of Lord Mansfield were included in encyclopedias and compendiums, with mentions of the Somerset case emerging in the 1840's:The Cabinet Cyclopaedia by Henry Roscoe, 1830, features a 57 page biography of Mansfield in an anthology of biographies. Roscoe mentions decisions which touch on religious liberty and civil rights, as well as libel and insurance, but no mention of Somerset v. Stewart.A Dictionary of Biography. Comprising the most eminent characters of all ages, nations, and professions ... Embellished with numerous portraits. Richard Alfred Davenport, ed. R. Griffin & Company: Glasgow, 1831 and reprinted in several editions. One quarter-page biography, no mention of Somerset.Lives of eminent and illustrious Englishmen, ed. by G. G. Cunningham. United Kingdom, 1836. 10 page biography of Lord Mansfield doesn’t mention Somerset.Lives of the Most Eminent British Judges, by Henry Roscoe, duplicate of the 1830 article above.Lives of Eminent English Judges of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. By William Newland Welsby. T. & J. W. Johnson, 1846. 80 page biography in an anthology. Detailed review of his life and his cases. No mention of Dido, but mentions his nieces. This anthology does mention the Somerset case but in connection with an earlier judge, Sir John Holt, not in Mansfield's biography. “Great as are the respect and gratitude with which all right-minded Englishmen must regard the memory of the Lord Chief Justice Holt, both as a criminal judge and an interpreter of constitutional law, he has no less a title to the veneration of every philanthropist, as the first judge who declared the soil of Britain incapable of being profaned by slavery….” Speaking of Holt, “in a subsequent case in 1707” Lord Holt declared, “no man can have a property in another, but in special cases, as in a villein, or a captive taken in war; but there is no such thing as a slave by the law of England.” It was not, nevertheless, until the solemn decision of the same Court in Somerset’s case in 1772, that this became an unquestioned principle of law, and could be made the exulting theme of the most thoroughly English among our modern poets [Cowper].”Baron Campbell, John Campbell. The Lives of the Chief Justices of England: From the Norman Conquest Till the Death of Lord Mansfield. Discusses and praises the Somerset case. John Murray, 1849.Leslie Stephen’s definitive Dictionary of National Biography (1895-1900) does include the Somerset case in its biography of Lord Mansfield. But as we've seen, biographers earlier in the century did not regard the Somerset case as one of Mansfield's most prominent decisions.

Alvan Stewart (1790-1849) After the Regency

Alvan Stewart (1790-1849) After the RegencyIn 1845, American lawyer and abolitionist Alvan Stewart praised Lord Mansfield for the Somerset decision and placed it in historical context: “But oh! What shall we say of the sublime humanity of Lord Mansfield and his compeers, who were not afraid to confess they had been wrong, and had the magnanimity to say it before a slaveholding age? This day saw the longest stride which British greatness ever took on the highway of human glory.