Lona Manning's Blog, page 6

May 27, 2024

CMP#188 What Has Been, continued

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. This post continues the synopsis and review of What Has Been, an 1801 sentimental novel by Eliza Kirkham Mathews. CMP#188 What Has Been: the short life and forlorn hopes of Eliza Kirkham Mathews, part 2

Continued from the previous post: The letter telling poor Emily that the man she loves drowned in a shipwreck is actually the evil work of a friend of Mr. St. Ives. The scheming Mr. Besfield wants to tighten the net around Emily until she consents to become his mistress. When she promises to pay her aunt's and her mother's debts and then her bank goes bankrupt, leaving her with nothing, he sees his chance. Her misfortunes, she tells Besfield, “have rendered her a creature, lost to joy in this world… but she preferred imprisonment, death, all the accumulated sorrows which injustice or cruelty could devise, to loss of honour!”

Continued from the previous post: The letter telling poor Emily that the man she loves drowned in a shipwreck is actually the evil work of a friend of Mr. St. Ives. The scheming Mr. Besfield wants to tighten the net around Emily until she consents to become his mistress. When she promises to pay her aunt's and her mother's debts and then her bank goes bankrupt, leaving her with nothing, he sees his chance. Her misfortunes, she tells Besfield, “have rendered her a creature, lost to joy in this world… but she preferred imprisonment, death, all the accumulated sorrows which injustice or cruelty could devise, to loss of honour!”“Proud, imperious girl!” [Besfield retorts] while his eyes glared wildly in their sockets. “beware of what you do, for remember no insult to me goes unrevenged!”

We later learn that with the connivance of Mr. St. Ives, the evil Besfield kidnapped Frederick and locked him up in a cottage. Frederick defies him: “You threaten to destroy the peace and innocence of the lovely Emily Osmond. Reptile! One glance from her eyes, beaming beauty and virtue, shall disarm thee of all power to injure her unsullied purity!"

To hide from the villain Besfield and from debt-collectors, Emily flees to the mouldering old family castle and the affectionate embrace of the two garrulous but loyal old domestics. Naturally, since she's a heroine and they are servants, they look after her, serving her meals, etc. Not that she eats much--she's usually too upset to eat. She spends her time looking out of the window sighing, and going for pensive walks and--oh, lord--composing sonnets. Emily never volunteers to dust the library books or anything. (I know I've banged on about this before, but really, imagine being so genteel that you don't know how to wash a plate or boil an egg and just take it for granted that someone else will do it for you.)

Gothic elements

Gothic elementsAnyway, Emily has some gothic adventures. She finds an old manuscript in a chest; the brief but pathetic history of her ancestor, Mildred St. Maur, who was cast off by the family. “Be calm, my heart, awhile, that I may trace my sad, sad, tale of woe…”

There is no indication that she uses her ancestor’s manuscript in her own novel, or for that matter, that she realizes -–hey, my own life is exactly like a novel! I might as well write down what is happening to me, right now! We have no details about the “work of fancy” she is writing.

One night, she hears noises and fears the bailiffs have broken in to the castle to arrest her: “Undetermined how to act, she raised the almost expiring candle in the socket, and was returning to her chamber, when, lifting her eyes, she beheld the figure of a tall man standing at the door. Uttering a piercing shriek, and only anxious to escape the stranger, Emily lifted the tapestry, and ran, or rather flew into the great gallery, where, stumbling over something which lay in her way, the candle was extinguished, and in the next moment she felt herself clasped in the arms of a man, and lifted from the ground.” End of volume I, folks! Surprise! Spoilers!

But don’t worry, it’s Frederick! He escaped from Mr. Besfield’s clutches!

Frederick begs Emily to marry him. So what if they don't have any money? “I will be your protector, friend, and husband; the labour of these hands shall procure the necessaries of life.” he vows. “Those,” said Emily, “are the fallacious visions which hope presents to your enthusiastic fancy. Alas! We are surrounded by melancholy realities.” She marries him, though, with much foreboding.

The love birds sneak out of the castle and set up in London where Frederick reluctantly looks for employment as a clerk but since he has no references he can’t find a job. Emily keeps her stiff upper lip as Frederick despairs. She urges him to keep trying: “perseverance and resolution conquer every difficulty.” It turns out that Frederick is so committed to female equality that he's fine with his wife being the chief breadwinner! So he convinces himself that she can write a best-seller.

“Is it possible,” replied Frederick, “that you, Emily, can wish me to become the slave of commerce, when so many more eligible plans are open for our future subsistence? Do not entertain so contemptible an idea of your own talents, as to suppose they will not effectually emancipate us from the dread of poverty, and render our future lives comfortable!”

Lawson and Agatha subplot

Lawson and Agatha subplotA new London friend, Mr. Lawson, lures Frederick into gambling and socializing until the wee small hours. His real target is Emily. When he has her alone, he expresses sympathy, and offers to be her “friend in the absence of your husband.” “Can a woman, possessing the exalted understanding which you do, be so prejudiced by that hydra-headed monster, custom, as to prevent you from using your reasoning faculties? Or are you frightened by the bugbear religion, which priests hold forth to ensnare weak and enthusiastic minds?" But the old “marriage is just priestcraft” argument doesn’t work on our Emily. So he turns to threats. He has lent money to Frederick and will send him to debtor’s prison: “by Heaven I swear, such shall be his fate, if you longer resist my entreaties!”

“Then I will meet it with fortitude,” replied Emily, “and welcome any affliction, rather than purchase safety and affluence at the price of dishonour!”

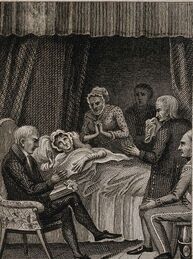

Lawson’s discarded and dying mistress Agatha shows up. He is filled with remorse when she forgives him on her deathbed: “But hark! I am called to heaven! Even now a band of angels strike on their golden viols. Ye bright intelligences, I come to bliss!... Nothing but virtue can secure peace in this world; delay not the hour of repentance. God—bless—you!” Lawson also dies, of remorse.

I'll have more about how Mathews used this subplot to introduce feminist and anti-slavery themes in a future post.

Bing AI Image More troubles before our happy ending

Bing AI Image More troubles before our happy endingThings still get worse for Emily and Frederick. They can’t pay their rent, they start pawning their clothes to get food to eat. (The grasping landlords and landladies in this novel for some strange reason begrudge providing free shelter to their social superiors). Emily does not take in sewing. She works on her novel and gives birth to a son, who sickens and dies.

Frederick is wrongfully accused of murder because he was in a church graveyard, surreptitiously burying his infant son at midnight, when a murder occurred nearby. This final blow—no money at all and Frederick in prison--will surely force Emily into the arms of that lascivious vulture, Mr. Besfield. No, she wanders the streets of London until collapsing at the doorway of a respectable dwelling which turns out to be the new home of her cousin Dorothea, who has just received a convenient inheritance!

But that’s not all! Emily’s wealthy uncle Mr. Hartfield realizes that he can’t stand Mrs. Elton, who is only dancing attendance on him in hopes of inheriting his money, and sets out to find Emily and discover first-hand whether all the nasty things Mrs. Elton said about her are true.

With the help of a friendly lawyer, Mr. Hartfield gets Frederick out of prison. They all shake the dust of the city from their feet. “Great cities,” said Mr. Hartford, “are nothing more than a sink for vice and folly… commerce! Civilization! Why, they have introduced more vices and follies than can ever be known in a country where agriculture is its chief support.” He makes Emily and Frederick his heirs and they live comfortably and happily with the garrulous but loyal old domestics at the old family castle.

“Emily still dedicated some hours in the day to study; her pen rendering her talents a means of enlarging their income, and the instruction she diffused useful to society at large. The subjects she chose tended to expand the understanding, meliorate the heart, and ‘justify the ways of God to man.’” Frederick, we suppose, lives the cultivated life of a gentleman that he was born to live.

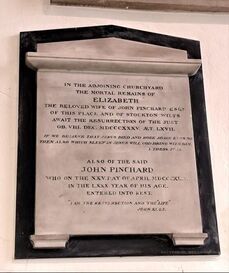

St. Mary Castlegate church in York, where Eliza was buried. Wikimedia photo by Chris06 Portrait of an aspiring author

St. Mary Castlegate church in York, where Eliza was buried. Wikimedia photo by Chris06 Portrait of an aspiring authorEmily never publishes her novel in this book, but she does receive encouragement from a publisher. Mathews breaks into the narrative to address the reader directly : “And here let me gratify the ardent desire I feel of describing a man, for whom all who know him must feel the highest veneration…. He appeared about forty-five, yet in truth was seven years older…” This may be a flattering portrait of William Lane, the proprietor of the Minerva Press. Eliza might have met him in person when, as a newlywed, she visited London with her husband to meet his family. Perhaps she had an early draft of her novel and made the rounds of the publishers.

The publisher in the book praises Emily’s draft manuscript, “which evinces purity of mind in the author, and derives… the brightest instructions in the ways of virtue and religion—though it abounds in highly coloured imagery, sentiment, and intelligence, it is, in its present state, unfit for the press—it wants connection." He encourages her to revise it “then return it to me, and I will become its purchaser.”

I don’t know what he means by “connection.” Maybe he meant the dangling sub-plots and the characters who come and go. My theory is that William Lane, well acquainted with what the patrons of his circulating libraries liked or didn’t like, gave specific directions to his authors: “Can you work in a castle, Mrs. Mathews? Maybe an old manuscript? We'll need some comic relief--put in a garrulous old domestic. And instead of just one vile seducer, how about another one for the second volume?” In fact, we know from that Eliza's brother-in-law was her agent with Minerva Press in London when she was in York. He reported that the publisher's wife made "some sensible suggestions" for "alterations," which he (the brother in law) put in. "I hope it has improved it." Previous post: What Has Been, part one

Published on May 27, 2024 00:00

May 20, 2024

CMP#187 Emily, the heroine who writes a novel

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

“[D]o not impose on yourself false hopes, which may never be realized. You well know I allude to your genius for writing… let the chief part of the day be dedicated to the humble, but truly respectable employments of the needle.”

--well-meant advice in What Has Been which was probably given to the actual authoress. CMP#187 What Has Been and the sad life of Eliza Kirkham Mathews, part one

Following her Muse no matter what I’ve tried twice before to read What Has Been (1801), a sentimental novel by Eliza Kirkham Mathews (1772-1802), but couldn’t get past the trite and mawkish prose of the opening scene. The heroine, Emily, only eighteen years old, weeps at the deathbed of her sister Matilda, the last member of her family.

Following her Muse no matter what I’ve tried twice before to read What Has Been (1801), a sentimental novel by Eliza Kirkham Mathews (1772-1802), but couldn’t get past the trite and mawkish prose of the opening scene. The heroine, Emily, only eighteen years old, weeps at the deathbed of her sister Matilda, the last member of her family.“Emily! Emily!” replied the almost exhausted Matilda, “forbear to embitter the last hours of my existence by useless regrets, or vain ebullitions of passion. Alas! My sister, let not your affection for me prompt you to execrate the unhappy Herbert, for unhappy he must be, since he has… forgotten the solemn vows he once made me, and in the hour of pain and misery, left me to reflect on his broken faith. But mine, Emily, is a death of triumph, for I die innocent.”

Raised in genteel circumstances, Emily is left alone and practically destitute.

But once I learned the real-life circumstances of Eliza Kirkham Mathews, I harbored a soft spot for her. She actually lived through the harrowing family loss and fall from gentility to poverty that she depicts in What Has Been. After losing her father, mother, and brother, she watched her sister Mary sink into a consumptive's grave, leaving her for a time alone in the world. She married, but poor Eliza coughed herself to death in rented rooms in York, scribbling away to the end. Okay, so she was not a great talent--she is no Keats--but the sad tale always stayed with me, and it caught Virginia Woolf’s attention as well, because she tells it in a short story called “Sterne’s Ghost” which you can read here.

Unregulated sensibility We know about Eliza’s life through the memoir of her husband, Charles Mathews, a celebrated Regency-era comic actor. His memoirs were written by his second wife. Anne Jackson Mathews, who knew Eliza. She gives a sympathetic yet condescending account of Eliza’s aspirations: “[H]er habits of confinement, (for she still clung to the fallacious hope of gain by her pen, and was constantly devoted to its exercise,) and her anxiety to contribute to her husband’s narrow and inadequate means was such, that she neither allowed herself air nor proper exercise… she grew weaker and weaker….”

Unregulated sensibility We know about Eliza’s life through the memoir of her husband, Charles Mathews, a celebrated Regency-era comic actor. His memoirs were written by his second wife. Anne Jackson Mathews, who knew Eliza. She gives a sympathetic yet condescending account of Eliza’s aspirations: “[H]er habits of confinement, (for she still clung to the fallacious hope of gain by her pen, and was constantly devoted to its exercise,) and her anxiety to contribute to her husband’s narrow and inadequate means was such, that she neither allowed herself air nor proper exercise… she grew weaker and weaker….”Both Eliza and her alter-ego Emily in her novel What Has Been came from Exeter, both had good educations, both hoped to make money by writing a novel. Eliza’s true-life story reminds us that the orphaned heroine narratives of the sentimental novel have their basis in the grim reality of the times. However, I doubt that Eliza in real life was pursued by a relentless villain intent upon her seduction and ruin, nor that her mother's family owned a tumble-down castle maintained by a pair of garrulous but loyal old domestics, and we know that a convenient fortune did not arrive like manna from heaven to save her from destruction.

Was Eliza inspired to write a typical sentimental novel plot or was she writing to the market? I suspect the latter. What Has Been is a Minerva Press novel; a publishing house that specialized in sentimentality and gothic thrills bound up with conventional morality. The heroine Emily's need to make money is one of the recurring motifs of the novel, and like her creator, she hopes to become a professional writer. We can learn about the social attitudes of the time from even third-rate novels. Other themes in the novel are: sensibility is harmful if not regulated, and life is a vale of tears which only religious fortitude can help you endure. Previous posts have dwelt on threats to female virtue. Instead, let’s focus on the attitudes towards employment and social class on display here.

Good advice from Mrs. Elton Okay, get your hankies ready!

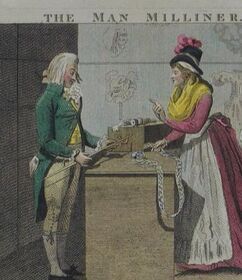

Good advice from Mrs. Elton Okay, get your hankies ready!After burying the last member of her family, Emily accepts an offer to stay with an impoverished aunt and cousin, even though they really can’t afford to support her. Her cousin Dorothea politely but honestly tells Emily that her dream of supporting herself as a writer is just that, a pipe dream. "What publisher will buy a first work unrecommended?" The female villain of the novel, a wealthy aunt named Mrs. Elton, also discourages Eliza. She once made Eliza's late mother's life miserable with her jealousy and gossip. Now she drops in to say: “So, Emily Ormond, you have been writing I see, child; but a needle, in my opinion, would become your fingers infinitely better—you that are dependent on the bounty of those who can scarcely support themselves… I cannot see what hinders you from working.” She thinks Emily should apprentice herself to a milliner or mantua-maker (hatmaker or dressmaker.)

“‘Indeed, Madam,’ returned Emily, checking the pride which swelled in her bosom, and crimsoned her cheeks, ‘I have no taste for those professions… it would be more respectable to superintend the education of some genteel children, or—my pen might procure me a comfortable subsistence.’”

“‘Ha! Ha! Ha!” vociferated Mrs. Elton. “Miss Emily will commence author, and live upon the produce of her prolific brain in an apartment next the sky… I really beg your pardon… I knew not that I was in the company of a genius.”

But for now, Emily feels too afflicted after nursing her dying sister ”from taking a situation honourable and independent… In which I can preserve my character and my conscience unsullied, and live unassisted by those, who, when my prospects in life were bright and alluring, called themselves my friends, but who now, in the days darkened by sorrow and poverty, regard me not; or if they do, it is only to wound my feelings by insulting pity or satirical advice!”

In other words, “go sit on a tack, Aunt Elton.”

Bing AI image Enter romance

Bing AI image Enter romanceMrs. Elton blames Emily for being too proud to work, thanks to having a mother who was the daughter of a baronet, and being educated above her station in life. And truth to tell, Emily can’t abide the thought of becoming a governess, and dreads it as much as Jane Fairfax does in Emma.

While Emily hesitates, our hero appears, in the form of a young man who is the ward of a relative on her mother’s side. Frederick Mandred is "descended from an ancient family" but has no fortune. He is a ward of Mr. St. Ives and works for him as a clerk. Mrs. St. Ives sends Frederick to escort Emily to visit them, and she gratefully accepts. (Frederick also lives with the St. Ives family). Emily's visit stretches out to an unspecified number of months, I think for the better part of a year, while Emily occasionally tries to talk herself into looking for work.

Mr. St. Ives, being in trade, is not completely genteel. Emily is quite indignant on Frederick’s behalf when he and she come in late for breakfast from a ramble on the beach and he is scolded for being late for work: “‘my counting-house is always opened at eight o’clock, and at that hour I expect to find all my clerks at their duty.’”

“Emily felt her hand tremble; and she had nearly spilt her coffee, when, timidly lifting her eyes towards Frederick, she beheld his cheeks clothed with the blush of indignation, and his whole frame agitated with restrained passion, which each moment she expected to hear burst from his bosom; but a manly silence sealed his lips.”

More trouble arises because Frederick falls in love with Emily and she with him. They have much in common: they both feel “rapturous enthusiasm” for “the enchanting scenery around them." “While her beauty pleased the eye, her ingenuous mind and excellent understanding captivated the heart, and interested the judgment.” And her forlorn situation is like catnip to him, because he is a man of sensibility.

Bing AI image This totally unexpected turn of events enrages Mr. St. Ives, who had arranged for Frederick to marry a local heiress and bring some money into his failing business. Frederick compounds the trouble by speaking to Emily at her bedroom door one night! “This is no time for the false refinements of delicacy, by Heaven: I shall go mad!” he exclaims. Up pops the master of the house. “Frederick Mandred!” vociferated Mr. St. Ives, “is this the return you make for the kindness I have ever treated you with? But come, leave the chamber of the young serpent who has seduced you from your duty, and robbed me of my peace.”

Bing AI image This totally unexpected turn of events enrages Mr. St. Ives, who had arranged for Frederick to marry a local heiress and bring some money into his failing business. Frederick compounds the trouble by speaking to Emily at her bedroom door one night! “This is no time for the false refinements of delicacy, by Heaven: I shall go mad!” he exclaims. Up pops the master of the house. “Frederick Mandred!” vociferated Mr. St. Ives, “is this the return you make for the kindness I have ever treated you with? But come, leave the chamber of the young serpent who has seduced you from your duty, and robbed me of my peace.”“Sir,” said Frederick, “breath not a word against her purity, she is spotless as an angel, and by Heaven, shall be my wife!”

Alas, Emily has outstayed her welcome. “To remain longer beneath the same roof with [Frederick] Mandred, after the declaration of love which he had made her, was the height of folly and imprudence; neither could her independent spirit brook the cool looks, and coarse manners of Mr. St. Ives; she saw he wished her to begone [after living at his expense for the better part of a year] but, alas! Whither was she to go? She had no home, no parent, no sister to receive her. Those who paid homage to her [well-born] mother… never now bestowed a thought on the poor orphan, Emily Ormond, unless it was to remark her imprudence in remaining inactive at Mrs. St. Ives’s when so many reputable professions offered themselves to her choice.”

Mrs. St. Ives also drops a hint: “Upon my word… a young woman, so very destitute as you are, ought certainly to exert some of the abilities, which nature has so very liberally bestowed on her, for her own support, and not expect—I beg your pardon, her friends to maintain her.”

Emily vows (and not for the first time) “From this moment I will depend on myself alone, my own industry shall procure me subsistence, and I will forego all claims on my rich relations…” She decides to “retire to an obscure village, where she knew she could be boarded cheap, and from the production of her needle earn an humble maintenance. “ But she learns that her poverty-stricken aunt is in arrears on her rent (“fine words butter no parsnips” snarls the landlord). Auntie is in danger of eviction or going to debtor’s prison. Emily pledges to give her the small inheritance she’ll earn when she turns nineteen, which, after clearing off her late mother’s debts as well, will leave her with nothing.

Emily vows (and not for the first time) “From this moment I will depend on myself alone, my own industry shall procure me subsistence, and I will forego all claims on my rich relations…” She decides to “retire to an obscure village, where she knew she could be boarded cheap, and from the production of her needle earn an humble maintenance. “ But she learns that her poverty-stricken aunt is in arrears on her rent (“fine words butter no parsnips” snarls the landlord). Auntie is in danger of eviction or going to debtor’s prison. Emily pledges to give her the small inheritance she’ll earn when she turns nineteen, which, after clearing off her late mother’s debts as well, will leave her with nothing.The aunt, Emily, and her cousin Dorothea all resolve to move to some cheap cottage, but just then, the aunt has a stroke and lingers on for weeks before dying. Dorothea luckily gets an offer to go to Switzerland as a companion to a wealthy family, but that leaves Emily alone with no money or friends. Emily does have a wealthy uncle but thanks to the malicious gossip of Mrs. Elton, he thinks Emily is a hussy and a fallen woman (that Frederick-at-the-door incident) and has cut off all communication with her. Oh, and did I mention she received a letter telling her Frederick was dead? That he drowned while on a voyage to Ireland on behalf of Mr. St. Ives? (Well, we don’t believe that for a moment, do we, folks?)

The story continues in my next post:

Charles Mathews, (1776-1835) courtesy National Portrait Gallery Echoes of Austen

Charles Mathews, (1776-1835) courtesy National Portrait Gallery Echoes of Austen Mrs. Elton asks the wealthy uncle Mr. Hartford, “if you liked the apricots which I sent you? I assure you they were [her daughter] Harriet’s own preserving, and never was a being more anxious to suit another’s taste than she is yours.” Anyone mentioning apricots makes me think of Mansfield Park. Mrs. Elton is the same species of bully/fawning flatterer like Mrs. Norris.

Emily tries to talk herself into working as a governess, but is repulsed at the idea: “Shall I attend to the education of children… be subjected to the caprice and insolence of parents, listen to the frivolities of visitors, and be admitted into their society as an inferior? Gracious God! I cannot support the thought.” The narrator calls Emily’s pride in her family descent an “error.”

When Jane Austen visited her brother Henry in London, she saw Charles Mathews perform on at least two occasions, as we know from her letters.

Previous post: Mary Jane Mackenzie's Geraldine

Published on May 20, 2024 00:00

May 13, 2024

CMP#186 Mary Jane MacKenzie's Geraldine

“If one scheme of happiness fails, is it not wise to try another?”

“If one scheme of happiness fails, is it not wise to try another?”-- Geraldine: or Modes of Faith & Practice CMP#186 Authors After Austen: Mary Jane Mackenzie

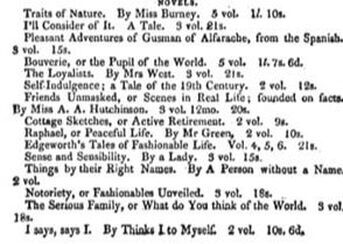

Mary Jane Mackenzie must have been thrilled with the positive review she received for her debut novel Geraldine. The Lady's Monthly Museum hailed "with pleasure the appearance of a tale which may be put into a youthful hand, not only without danger, but with a rational hope that its contents will make a favourable impression on the side of virtue. To this high degree of praise the novel before us is entitled; it is evidently the work of an author who units talent to sound judgment and true Christian principles.”

Mary Jane Mackenzie must have been thrilled with the positive review she received for her debut novel Geraldine. The Lady's Monthly Museum hailed "with pleasure the appearance of a tale which may be put into a youthful hand, not only without danger, but with a rational hope that its contents will make a favourable impression on the side of virtue. To this high degree of praise the novel before us is entitled; it is evidently the work of an author who units talent to sound judgment and true Christian principles.”Blackwood's Magazine said: "This is the best written Novel, except Anastasius, that has been published in London for several years. The conversational style, one of the best I have seen–clear, natural, and unaffectedly elegant, and full of the spirit of good society." The Monthly Review said: "Her novel is one of the few which possess the rare merit of entertaining and amusing us, while they are devoted to a moral and religious object.”

Geraldine, or Modes of Faith and Practice, was published in 1820 by the prestigious publishing house of Cadell & Davies, who also published the best-selling Christian author Hannah More (and this is the publishing house that turned down Pride & Prejudice years before it was finally published).

The novel also contains some echoes of Austen--in my opinion. Let's see if you agree.

The cave of Trophonius in Livadeia, Greece. Etching by Elizabeth Byrne, 1813, after E.D. Clarke. Wellcome Collection. Fanny is the flirty one, Geraldine is the quiet one

The cave of Trophonius in Livadeia, Greece. Etching by Elizabeth Byrne, 1813, after E.D. Clarke. Wellcome Collection. Fanny is the flirty one, Geraldine is the quiet oneGeraldine centers on the travails of a young heroine, Geraldine Beresford. In Volume I, the heroine’s beloved mother has died, and her father wants to travel around the continent to forget his grief. He parks Geraldine, who is about fourteen, with his sister Mrs. Mowbray, her husband, and her three cousins, who are all older than her.

One striking feature of this novel is that the dialogue--which Blackwood's Magazine praised--is crammed with poetical, classical, literary, and biblical allusions and quotes. The novel opens with a conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Mowbray. Over a few pages, Mrs. Mowbray refers to a ‘veiled prophet,’ Horne Tooke, Johnson, Lowth, Mrs. Shandy, Griselda, ‘two stars kept their motion in one sphere,’ ‘bestow her tediousness,’ Glumdalclitch, and ‘sonnet to his mistress’s eyebrows.’ Mary Jane Mackenzie, whatever her merits as a writer, wasn’t shy about sharing her erudition. She presumes her readers will understand what a reference to the "Cave of Trophonius" is about. The characters in Geraldine also debate about the theatre, poetry, music, whether French cuisine and music is better than English, and religion.

Geraldine, being young and unused to the world, is taken aback by the glamour and worldly cynicism of her Mowbray relatives. She keeps quiet in the first scenes of the novel. At a dinner party she is “allowed the privilege of listening as quietly as she pleased.” Her cousins are Geraldine, Fanny, and Montague.

Georgiana, the eldest daughter, marries a nabob (a man who made his fortune in India), and she goes to India with him. The narrator makes it clear that this marriage is motivated by worldly ambition. Geraldine, meanwhile, quietly loves her cousin Montague.

The other sister Fanny is a witty flirt. Montague brings home a friend, Mr. Spenser, who “has lately succeeded to an unencumbered estate of 2,000 a year.” He and Fanny fall rapidly in love. Mr. Mowbray is worried that Spenser’s adoration of his daughter is intense rather than lasting, but he reluctantly allows the marriage. Fanny and Spenser go to live in Richmond and Geraldine misses her. “Geraldine, after the bustle attendant upon the dignity of a bride-maid was over, felt at leisure to regret Fanny exceedingly. The sight of the room she had occupied, and all the little vestiges it contained; the work-box, that had been thought unworthy of a bride—and the flower-stands, which had been pronounced unfit for Richmond, excited very painful emotions.”

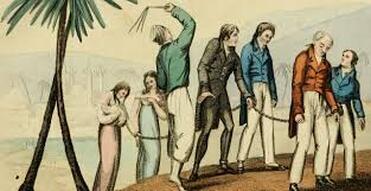

English brides arrive in India Religious fanatics and more Austen echoes

English brides arrive in India Religious fanatics and more Austen echoesA few years pass. Sometimes the Mowbrays visit their neighbours, the Wentworths. Miss Wentworth is a puritanical fanatic who frightens her little sister with threats of hellfire. Mrs. Wentworth who is an indolent lady who doesn’t pay any attention to her children. We also meet a minor character named Miss Crawford.

Geraldine grows up into a lovely young lady. She has a handsome inheritance, since she is her father’s only heir, so the Mowbrays don’t object when their son Montague proposes to her. But then Montague becomes infatuated with a designing widow, and Geraldine breaks off their engagement.

We learn that while Geraldine’s late mom was intelligent and respectable, dad is not a shining character. Mrs. Mowbray says of her late sister-in-law: “She contrived to give dignity and importance—nay, even a sort of lustre, to [her brother's] character.” Mr. Mowbray, a sort of sarcastic Mr. Bennet type, says, “even the leaden mantle of mediocrity did not weigh him down in his wife’s time.”

The Mowbrays receive word that Geraldine’s father has been spending all his money in Italy and running his estate into debt. “Our measures must be prompt and decisive, Geraldine,” Mrs. Mowbray tells her. “if we can persuade your father to return immediately to England, all may yet be well." Mrs. Mowbray resolves to go to Italy and takes Geraldine and young Mr. Maitland, the clergyman, with her.

Old History (detail) Alexander Jakesch Spoilers ahead

Old History (detail) Alexander Jakesch Spoilers ahead In Italy, Geraldine and her aunt discover that her father was tricked into marrying a young woman who then spent all his money. He is dying, and Geraldine gets to his bedside just in time to say goodbye.

Mrs. Mowbray laments, “His fortune, thanks to the ingenious extravagance of this ‘foreign wonder’ is reduced to a complete wreck." So now Mrs. Mowbray doesn’t want Geraldine to marry her son.

Mr. Maitland the clergyman suddenly becomes the romantic lead. On the voyage back to England, he falls in love with Geraldine but he hides his affection, because she's still carrying a torch for Montague.

Meanwhile, the marriages of the Mowbray girls go badly. The climate of India has destroyed the health and good looks of the oldest daughter Georgiana. Fanny is miserable because her husband has lost interest in her and he’s having affairs. She in turn finds a lover and elopes with him! When the news reaches Mrs. Mowbray, “She was astonished and grieved… but it was not the sin, it was the disgrace by which she was chiefly affected. She pronounced it to be a shocking affair, a very shocking affair indeed; but she felt more irritated by the folly, the imprudence, the absurdity of Fanny, than humiliated by her [daughter’s] guilt. To forfeit such a station, to forsake a husband who neither limited her expenses, controlled her wishes, nor interfered with her pleasures, because he happened not to be immaculate, was either an act of positive madness, or of folly the most inexcusable.”

Geraldine, on the other hand, is horrified. “Affected even to agony, she wept over the fall, shuddered at the guilt, and trembled for the future destiny of Fanny… this irretrievable evil might be attributed to her wretchedly defective education.”

Fanny’s elopement leads to retribution for some, repentance for others. In the conclusion, Geraldine rejects the charming but unstable Montague Mowbray and marries the worthy Mr. Maitland.

Portrait of a young woman with Bible, Jan Braet von Überfeldt, 1866 Other features

Portrait of a young woman with Bible, Jan Braet von Überfeldt, 1866 Other featuresSlavery and empire: Before her marriage, Geraldine's mother loved one Mr. Fullarton, but lack of money prevented their union. After Mr. Fullarton's romance with Geraldine's mother was thwarted, he inherited a “small estate in the West Indies." This is another example of sending a character abroad until you need them back for plot purposes, a very common device discussed previously . However, Mackenzie also makes use of the West Indies connection to be more explicitly anti-slavery than Austen chose to be in Mansfield Park. Fullerton sold his property but "he [was] anxious, if possible, to secure the freedom and comfort of the slaves employed on it." After all, selling your plantation because you are opposed to slavery doesn't do anything for the enslaved people working there and quite likely could make their condition worse.

Strong religious message: Upon his re-entry into the novel, Mr. Fullarton counsels Geraldine on avoiding the vices and snares of this world. Geraldine's Church of England piety is contrasted with the frivolous and worldly Mowbrays on the one hand, and the puritanical Miss Wentworth on the other--hence the subtitle, Modes of Faith and Practice. The ultra-religiosity of Miss Wentworth is shown to be a form of vanity.

English pride: Although Mr. Wentworth is lampooned as a bluff and ignorant John Bull type, throughout the novel everything English is held up as superior and safer than foreign countries and foreign ideas, and the countryside, of course, is better than the wicked city.

Charitable cliches: I previously quoted the passage in Geraldine in which the heroine fondly remembers how the villagers blessed and thanked her charitable mother.

Harriet Auber, Mackenzie's companion About Mary Jane Mackenzie

Harriet Auber, Mackenzie's companion About Mary Jane MackenzieMary Jane Mackenzie (1783--1857) does not appear in the Orlando: Women's Writing in the British Isles Database of the University of Cambridge. Her family lived near the Tower of London and attended All-Hallows-by-the-Tower church, the oldest or one of the oldest churches in London. The extensive literary and classical allusions in her novels suggests that she had a good education and was an avid reader.

Mary Jane never married and the downfall of Mr. Mowbray in Geraldine bears some resemblance to the troubles which beset her own family. Mackenzie was thrown into alarming poverty but fortunately her friends and admirers collected monies to provide her with a modest pension. In the last part of her life, she lived with her friend Harriet Auber, a hymnist and author of religious tracts. They were known for their sweet natures and their piety. They lived quietly in Ware and Great Amwell near Hoddeston, in Hertfordshire, and they both published anonymously. Mackenzie published another novel, Private Life, and some religious books for young people, as well as pieces for magazines.

This LitHub article says: Austenites, stop hating on Thomas Cadill because he turned down Austen's manuscript. He was actually very supportive of women writers.

Scholar Rachel Howard describes Geraldine as a "conversion novel," (in other words, a novel in which a character has a "come to Jesus" moment), and it is described as a sub-genre of the "moral-domestic" novel. She spotted the many of the same Austen parallels that I did.

Howard, Rachel. Domesticating the Novel : Moral-Domestic Fiction, 1820-1834. 2007. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series.

Published on May 13, 2024 00:00

May 6, 2024

CMP#185 Olivia, the Heroine of Colour

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#185: Book Review: The Woman of Colour, by Anonymous

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#185: Book Review: The Woman of Colour, by Anonymous

The Woman of Colour, first published in 1809, has drawn a lot of interest in academic circles because the heroine is a mixed-race woman of colour. It was certainly an unusual and perhaps daring choice to have a main character who is a sympathetic, intelligent, educated woman of colour who can quote Shakespeare, Cowper and Milton, The novel is remarkable in that sense, and it is unusual because it does not end with a marriage, but it is not, as we will see, remarkable for its literary quality. It is in other respects a typical sentimental and didactic novel of the long 18th century.

The Woman of Colour, first published in 1809, has drawn a lot of interest in academic circles because the heroine is a mixed-race woman of colour. It was certainly an unusual and perhaps daring choice to have a main character who is a sympathetic, intelligent, educated woman of colour who can quote Shakespeare, Cowper and Milton, The novel is remarkable in that sense, and it is unusual because it does not end with a marriage, but it is not, as we will see, remarkable for its literary quality. It is in other respects a typical sentimental and didactic novel of the long 18th century.Olivia is the illegitimate daughter of an enslaved woman and a plantation-owner. This sounds like a pretty serious bar to admittance in "good" society. But she is also heiress to 60 thousand pounds, three times more than Mary Crawford had in Mansfield Park, and ten thousand more than Miss Grey had in Sense and Sensibility. Further, we should not be surprised to learn that Olivia’s mother was “majestic,” beautiful,” “sprung from a race of native kings and heroes,” and a convert to Christianity.

Once you know Olivia’s mother is descended from African royalty and she's an artless and confiding Christian girl in love with a white man, and if you know your 18th century tropes, you will know she's dead: “In giving birth to me she paid the debt of nature and went down to that grave, where the captive is made free!”

This is an epistolary novel, so the voice you hear is Olivia Fairfield, writing to her “earliest and best friend," her governess Mrs. Milbanke. Let's hope the ship she's sailing on has fewer holes in its hull than this book has plot-holes, the first one being: If Mrs. Milbanke is a governess, why doesn't Olivia just pay for her to come along on the voyage? She really does need a respectable older escort in a situation like this. But of course Mrs. Milbanke is a device for exposition, not a character in the novel.

Olivia writes to Mrs. Milbanke that her father’s last will and testament ordained that she can keep her inheritance only if she settles down in England and marries her (white, of course) cousin Augustus Merton; if they don’t marry, the money goes to his (already married) older brother George, who will decide how much of the money Olivia gets to keep. That's why she's sailing for England.

Why did dad make such a strange will? Because reasons. Let’s just roll with it...

“You will ask me why I recapitulate these events? Events which are so well known to you.”

“You will ask me why I recapitulate these events? Events which are so well known to you.”And why is Olivia explaining biographical facts to her governess, facts Mrs. Milbanke would be perfectly aware of?

Umm, because the author isn't skilled enough to work the exposition naturally into the narrative, maybe? Nope, it’s because “I love to dwell on the character of my mother; it is that here I see the distributions of Providence are equally bestowed, and that it is culture not capacity which the negro wants!”

So right away we have strong references to Christianity and a plea explicitly founded on that religion for the natural rights of people of color. We'll return to that.

At any rate, our heroine is enjoying the company of some fellow passengers on the journey to England: the ailing Mrs. Honeywood and her adult son, who looks at Olivia and sighs a lot, heaven only knows why. At least, Olivia doesn't know why.

The good ship ***** docks in Bristol, where Olivia parts with the Honeywoods (for now) and, with understandable trepidation, meets her uncle Merton, her sister-in-law, Mrs. George (Letitia) Merton, and her intended bridegroom Augustus. She likes Augustus! She thinks they might be compatible. He doesn’t seem that enthused though, which she fears might be his reluctance to marry a woman of color. He is melancholy and he sighs a lot.

Next we have the most-discussed scene in the novel, where the despicable sister-in-law makes a point of serving Olivia a big bowl of rice at dinner, with the professed but insincere objective of making her comfortable, because rice is what negroes eat. Then the Mertons’ little boy comes in exclaiming over the dirtiness of her servant Dido’s skin. Olivia sweetly and calmly explains to him that their darker skin colors are not caused by dirt.

The scene with little George reminded me of other books I have read, aimed at children, in which a wise adult explains to a startled or disdainful white child that negroes are normal human beings who just happen to look different. If I come across any other examples, I will list them. The difference between this scene and similar scenes is that Olivia is advocating for herself--no helpful white person is doing it for her.

In-laws in trade (shudder)

In-laws in trade (shudder)Olivia and Augustus tie the knot within the allotted time set out in her father’s will, even though it is clear he is harbouring a secret sorrow. He treats her well. They take a honeymoon trip to visit the “lions” of London, which is a slang term for the sights of London. She enjoys London, but no more than is proper for a heroine, because heroines must have a decided preference for the country. We also have some samples of the rude things that people say about the "sable goddess" behind her back but within her hearing in public places.

George Merton and his wife are objectionable company. Letitia is lazy, languid and obviously holds Olivia in contempt; George is engaged in grubby commerce, which holds no interest for Augustus. Olivia, whose fortune, let’s remember, comes from the labour of enslaved people, says this of her intended spouse and she evidently means it as a compliment:

“The plodding track of cent. per cent. and addition on addition, never suited the taste of Augustus, and leaving his brother to accumulate thousands upon thousands, he is content to live on the fortune which my father’s will bequeathed to him with his wife. The wise father [that is, Mr. Merton, Sr.] and the plodding brother, may laugh, but they cannot persuade him, that a ‘man’s life consisteth in the abundance of things which he possesseth,’ when the Word of God, and his own heart, both teach him the contrary.”

Olivia shows similar disdain for other characters in the book who are from the merchant classes.

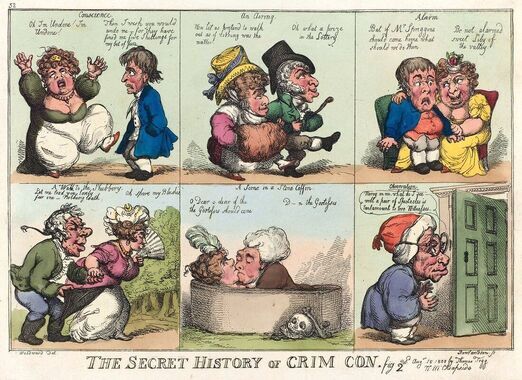

Mutton Dressed as Lamb, Fashion History Museum And objectionable neighbours

Mutton Dressed as Lamb, Fashion History Museum And objectionable neighboursSo it’s off to the countryside, living on the interest of a mere 60,000 pounds (3,000 a year, more than Bingley’s fortune in Pride and Prejudice) where: “the conversation of my husband, a contemplation of the beauties of nature, the society of rational and well-informed friends; books, music, drawing, the power of being useful to my fellow creatures,--to my poorer neighbours;--the exercise of religious duties,--and the grateful heart, pouring out its thanks to the Almighty Bestower of such felicity!”

It turns out that rational and well-informed friends are a little thin on the ground in the country, or at least, Olivia’s letters to Mrs. Milbanke back in Jamaica are taken up with describing the objectionable and ridiculous characters: there’s Colonel Singleton, an ageing lothario who thinks he’s devastating to the ladies. His spinster sister, Miss Singleton, makes herself “ridiculous” with her “poor shriveled and thin neck“ on display, along with her “bared ears, and elbows, and back, and bosom.” She plays no significant part in the story and is just there to be laughed at and held up as an example to avoid.

Of slightly more importance to an upcoming sub-plot are Lord and Lady Ingot, a couple with an immense East Indian fortune. More grubby commerce. A reminder though, that it's typical for novels of this era to feature a gallery of kooky characters who exhibit a variety of faults, as we find in Austen as well (just think of the people Anne Elliott has to contend with in Persuasion). It's also typical for people who made their money in trade to be portrayed as vulgar social climbers. At any rate, the antics of these characters fill out the pages between Olivia's wedding and the big Surprise that is coming.

On the "rational and well-informed" neighbours side, we have Mr. Bellfield, (the upright and old-fashioned uncle to Lord Ingot), plus Mr. Waller, (tutor to the Ingot’s teenage son), the clergyman Rev. Lumley, and his family. Mr. Waller is sweet on Caroline Lumley, which gives us a minor romantic subplot.

Olivia and Caroline, as good heroines, engage in acts of charity. They work on establishing a “School of Industry” for the poor of the village, and all their doings are relayed back to Mrs. Millbanke in Jamaica. Spoilers ahead! Spoilers ahead!

This happy life in the country doesn’t last long. First, a mysterious woman, a “fair incognita,” comes to stay with a small child in a cottage nearby, arousing the curiosity of the entire neighbourhood. Olivia's sister-in-law Letitia comes for a visit, even though it’s obvious she hates Olivia and Olivia despises her.

An extremely fierce storm rages through the neighbourhood, and the next morning, Mrs. Merton is strangely happy and interested when Olivia and Augustus decide they had better visit the fair incognita to see if she is all right. Just as they arrive, the F.I. rushes out, distressed (we later learn it is because the lothario Colonel Singleton has been pestering her) and runs into Augustus, who is… her husband!!!

Olivia is “ruined,” because she is not married after all. She refuses to believe that Augustus could have willfully deceived her, but she receives no explanation for how this could have happened.

The sure refuge of the poor but virtuous heroine, a cottage in Wales. Moss Cottage, by John Steeple Where do you go in a case like this? Wales, of course!

The sure refuge of the poor but virtuous heroine, a cottage in Wales. Moss Cottage, by John Steeple Where do you go in a case like this? Wales, of course!Olivia removes herself swiftly from her once-happy home, not before receiving a letter from the leering Colonel Singleton, offering to take her “under his protection,” if you get my drift. Her in-laws George and Letitia receive her fortune, and she has only a small pension to live on. She takes a cottage in Wales with the faithful Dido.

But ere long, the faithful Dido discovers that Mr. Honeywood, their old shipboard companion, is one of the neighbours. When he visits to condole with Olivia, she responds: (and this is the theology of the author in a nutshell): “It is not for us, narrow-sighted beings as we are, to inquire into the dispensations of an all-wise and all-just God! Afflictions fit us for another world—for a statement of enjoyment; they make us eager to quit these scenes of transient sorrow, and to go to the regions of eternal bliss!”

Olivia’s mulatto skin and her “ruined” state do not dissuade Honeywood from proposing marriage because he fell in love with her on the voyage to England, though Olivia had no idea! He also has a convenient inheritance due to the convenient death of a hitherto-unmentioned relative, which is certainly more genteel than just earning the money in trade. Honeywood proposes marriage in an impassioned and lengthy speech, which Olivia transcribes for Mrs. Millbanke back in Jamaica, but she rejects him: “I now, and to the last moment of my existence, shall consider myself the widowed wife of Augustus Merton.” (That doesn't mean she wishes him dead. She wishes him happy, but he is dead to her.)

Further, she asks Mr. Honeywood not to visit any more; it would not be proper for her to receive him as a visitor, since they are both single, and the neighbours would talk. Backstory time

Next, Olivia learns the backstory of Augustus, which explains everything. We turn back the clock a few years: her evil sister-in-law was the spoilt daughter of a rich tradesman in the city of London. Letitia was sent to the wrong kind of boarding school, the kind which only feeds her vanity. The family takes in a poor orphaned niece, the daughter of a clergyman, Angelina Forrester, who becomes the Cinderella of the household. Angelina is forced to read sentimental novels from the circulating library aloud to Letitia by the hour.

Letitia's father and old Mr. Merton are business partners and they hit on the idea of marriage between their offspring. Letitia prefers the youngest son, Augustus, but Augustus refuses the match because he doesn't like her. He falls in love with Angelina. They secretly marry.

When Letitia and her mother find out, they arrange for Augustus to be sent to Ireland on business. Then they deceive Angelina into believing that Augustus tricked her into a sham marriage ceremony with a fake minister. The Fate worse than Death! That means she's a ruined woman! They pay for Angelina, now pregnant, to go away into Wales. “She only wished to hide her shame and sorrow in obscurity!” A convenient bout of smallpox kills all the servants with any knowledge of what has transpired, and Augustus is told that Angelina is dead, too.

Augustus is therefore acquitted of having deceived Olivia as to the existence of his first wife.

So… instead of being a knave, he’s a bit of a fool? Never mind, let’s roll with it.

Letitia goes on to marry the eldest son, George, yet she still burns to revenge herself further on Augustus for rejecting her. With the news about the Jamaican heiress, her opportunity comes, plus she has the chance to poach Olivia’s fortune.

But... wait a minute... the sister-in-law could have revealed that Angelina was alive right away, and she’d have gotten the money right away, because Augustus couldn't marry Olivia if he was already married.

Then we wouldn’t have the central drama of the story, would we?

Deathbed repentance Confession and Repentance

Deathbed repentance Confession and RepentanceOlivia learns all this weeks later, after Letitia Merton--wait a minute, when Angelina ran into the arms of Augustus, why didn't he exclaim: “They told me you were dead!” and why didn't she say, “Well, did you ask where I was buried, or speak to the attending physician when you got back from Ireland, or anything?” This could have been cleared up in two minutes and it dragged out for weeks and weeks?

That's right, the full story doesn't come out until Letitia Merton “was seized by a violent and alarming illness" and confessed the entire plot. She produced “proofs of her guilt.”

Oh, now we’re asking for proof? Why didn't anyone ask for proof before?

Facing Almighty judgement, Mrs. Merton repents, and Olivia forgives her.

We also discover that the upright and decent old Mr. Bellfield--wait a minute. If Augustus thought he was a widower, why didn't Olivia notice when he signed the marriage register as a "widower." He had nothing to hide in that respect. So why--

Never mind. As I was saying, decent, upright Mr. Bellfield turns out to be the great-uncle of Mr. Honeywood and the nephew of the Ingots. Mr. Bellfield moves to Wales to live with Honeywood, because he is much kinder than those vulgar Ingots. He visits Olivia and pleads Honeywood’s suit, but she refuses again.

Olivia is called upon throughout to exert the highest levels of moral fortitude, which calls for a lot of referring to herself in the third person. Her faithful servant Dido also speaks of herself as “Dido” and in the third person, (“me don’t mind that though”). Olivia does it out of literary convention and Dido is doing it because, although she's lived amongst English-speaking people all her life, she hasn't mastered subject versus object pronouns--and no wonder, if the people around her start talking to each other third-person style whenever they get worked up. "Is it the venerable, the good Mr. Bellfield that seeks to persuade this beating heart to become an apostate to its first love?" {Olivia says to Mr. Bellfield]

"Is it Miss Fairfield," [Bellfield responds sternly] "is it Miss Fairfield who talks of a passion [for Augustus, married to someone else] which she ought never to name?--which she ought to exert all her fortitude, all her resolution, to extirpate for ever from her heart?"

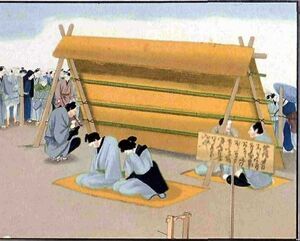

Missionaries spreading Christianity Religious moral

Missionaries spreading Christianity Religious moral After all the unhappy marriages we've read about in this book (including Mrs. Honeywood’s ill-starred marriage to a West Indian planter), the wrap-up gives us some happy unions. In addition to the reunited Augustus and Angelina, Mr. Waller is given a good living and he marries Charlotte Lumley.

But what about Olivia? Will she relent and marry Mr. Honeywood? No, she says that had Augustus died, she would never have remarried: "this bosom could never have known another lord." The fact that he is not dead makes no difference to her. She explains this several times.

She returns to Jamaica and her friend Mrs. Milbanke, with some of her fortune restored, to do some Uplifting: “I shall again zealously engage myself in ameliorating the situation, in instructing the minds—in mending the morals of our poor blacks.” Despite what's happened to her in England, Olivia gives the nation a respectful benediction because it has produced a few excellent men, like Augustus, Mr. Bellfield, and Rev. Lumley.

We conclude with the double lessons the author hoped to convey: (1) “there is no situation in which the mind (which is strongly imbued with the truths of our most holy faith, and the consciousness of a divine Disposer of Events) may not resist itself against misfortune, and become resigned to its fate" (and 2) "teach one skeptical European to look with a compassionate eye towards the despised native of Africa..." I surmise that the author was bold enough to suggest that a woman of color could marry a white man on a basis of social equality, but in the end, she did not insist upon the point. Olivia's notable piety and her life of celibacy can be compared to Yamboo, another novel with a saintly black main character. He inherits an English estate but does not dream of presuming to marry the (white) woman he loves. The person of color can be accepted into English society--but only so far... Modern approaches to the novel

The modern reissue of The Woman of Colour is issued by Broadview Press, edited and with an introduction by Lyndon J. Dominique. This edition includes some valuable appendices with a listing of other books of the era which include people of colour. You can find some more examples here as well in my earlier posts. In his introduction, Dominique points out that the Jamaican legislature strictly limited the amount of monies the mixed-race children of white Jamaicans, or blacks in general, could inherit. Although this isn't spelled out in the book, perhaps this accounts for Olivia's father's strange will.

Lyndon J. Dominique discusses The Woman in Colour in this online lecture, adroitly managing to interpret the motivations of the main character without once referencing the Christian faith she explicitly cites throughout the novel. He also defines the word "accursed" as meaning "a strong dislike for someone." The book discussion starts at 17:00.

About the author

The question of authorship of A Woman of Colour is an open question because of a tangled history of attributions of titles, including some deceptive attributions, on the title pages of other novels of the period, coupled with the common custom of using anonymity. This is why several now-obscure authors have been credited with this title, such as Mrs. E.M. Foster and Mrs. E.G. Bayfield. I discussed another novel attributed to Bayfield, The Splendour of Adversity (1814), here. This article by the Women's Print History Project explains the tangled attribution chain and even includes a flowchart!

Although written in the first person, which implies that it was written by a woman of color, the novel is presented in the "here are some letters which I've found/been given" style, aka a framing device. The author presents herself as the "editor" of the work, and leaves it open as to whether Olivia Fairchild is a "real or imagined" person. Presenting a novel as a collection of real letters, or somebody's real diary, was not uncommon in the 18th century, but I think both epistolary novels and the "this is a true story" gambit were outdated by 1809. Previous post: Cecily, the resilient heroine

Published on May 06, 2024 00:00

April 30, 2024

CMP#184 Cecily, the heiress who bounces back

“[W]hen young women of respectable situation, either tolerate or applaud vice, the wretched morals of the age are fixed beyond redemption.”

“[W]hen young women of respectable situation, either tolerate or applaud vice, the wretched morals of the age are fixed beyond redemption.” -- Mr. Delamere, in a typical prosing mood, in Cecily Fitz-Owen CMP#184 Book Review & synopsis: Cecily Fitz-Owen; or, a Sketch of Modern Manners (1805)

A kindly advisor Like our previous author, the anonymous author of Cecily Fitz-Owen had a lot he wanted to get off his chest, and so the story of our heroine Cecily’s search for true love is interspersed with much commentary and moralizing on various topics from both the narrator and Cecily's friends the Delameres. Janeites will recall that Austen playfully joked that her novel Pride and Prejudice needed more such digressions: "it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story: an essay on writing, a critique on Walter Scott, or the history of Buonaparté, or anything that would form a contrast." But she didn't mean it, of course. Austen is not as didactic as other authors, as I've learned. The didactic tone and the overall technique of this novel reminds me of Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife, except that Cecily Fitz-Owen has a little more plot and arguably is better written than Coelebs.

A kindly advisor Like our previous author, the anonymous author of Cecily Fitz-Owen had a lot he wanted to get off his chest, and so the story of our heroine Cecily’s search for true love is interspersed with much commentary and moralizing on various topics from both the narrator and Cecily's friends the Delameres. Janeites will recall that Austen playfully joked that her novel Pride and Prejudice needed more such digressions: "it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story: an essay on writing, a critique on Walter Scott, or the history of Buonaparté, or anything that would form a contrast." But she didn't mean it, of course. Austen is not as didactic as other authors, as I've learned. The didactic tone and the overall technique of this novel reminds me of Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife, except that Cecily Fitz-Owen has a little more plot and arguably is better written than Coelebs.Another comparison to consider-- are there any intelligent, older people who give excellent advice and admonition to any of our Austen heroines? Mrs. Gardiner comes to mind as playing a small role in that way, but apart from that, I can't think of anything in Austen that's comparable. Leaving out love interest mentors, like Mr. Knightley, that is.

With so many digressions, the author has not left much room to devote to Cecily. I’m going to skip over the digressions, the “Sketch of Modern Manners” part, and focus on Cecily Fitz-Owen for now, then get back to the digressions, because they are of social interest.

Bing AI image An eligible heiress and the dangers of novel-reading

Bing AI image An eligible heiress and the dangers of novel-readingCecily, an orphaned underage heiress, has two guardians, a lawyer and an ambitious churchman. She mostly lives with Rev. Trollope and his equally ambitious wife. Cecily’s first venture into romance teaches her how treacherous the world can be. While staying with the Trollopes, a handsome and engaging relative comes to visit. Cecily falls for Captain Thomas Crawford and the Trollopes happily anticipate folding Cecily's fortune into their family.

When Cecily goes to visit another family, the captain follows and urges her to elope with him, but she refuses. Later, she accidentally overhears Crawford arguing with a young woman named Fanny O'Byrne. He had promised Fanny marriage; she lived with him and bore him a daughter. He tells Fanny he will support her and their child with “a liberal allowance” once he marries the heiress. He then discovers Cecily fainted at full length in the grass.

Crawford realizes he has ruined his chances with Cecily forever, (“Eternal furies blast you!”) and we last hear of him shipping out to the East Indies (the novelistic equivalent of exiting stage left).

Cecily consoles poor Fanny and hears her backstory. She is from modest means and was apprenticed to a milliner: “The young women in the shop were in the constant habit of reading novels—The amusement was too gratifying for me not to partake of it; and I here found, in volumes without end, that love was the great object of life—that every woman, the least interesting, must be deeply plunged in the passion.”

Although Fanny is a fallen woman, Cecily and Mrs. Delamere combine to set her up in business “as a person for whom we felt an interest,” on the condition that should she ever receive an offer of marriage, she must disclose “the errors of her youth” to her potential husband. Fanny then drops out of the narrative.

Stock character: the gluttonous clergyman Enter our hero--and some mystery

Stock character: the gluttonous clergyman Enter our hero--and some mystery Without any great fanfare--no encounter such as a carriage accident or a near-drowning--Cecily meets another young man, Henry Darleville. Henry is withdrawn and perpetually morose because he was brought up in utter seclusion by his reclusive mother who arrived in the neighbourhood under mysterious circumstances. Henry adored his mother and with her death, he’s left without anyone in his life, having also, as we learn, lost his best friend and his first love (to worldly ambition, not death). Mr. Delamere kindly advises him to get out and mingle in the world.

Meanwhile, Cecily’s two guardians try to pressure Cecily into marriage with Rev. Trollope’s noble relative, Lord Layton. But Layton has led a dissolute life and Cecily, with the backing of the Delameres, firmly refuses him.

Trollope is frustrated because he hoped to benefit from facilitating the match of the heiress and the nobleman: “Thus might all greatness be put a stop to, and everything lost through the idle delicacies of a foolish girl, and the squeamish fastidiousness of a canting moralist [ie Mr. Delamere]."

Trollope still hopes to become a bishop: dreams of preferment “floated in his brain—when the shrill voice of Mrs. Trollope was suddenly heard crying—'Dean, why Dean, the tea has been ready this half hour!' Canons and prebends in long succession—doors suddenly expanded—the organ’s swell echoing along the aisles—the awe-struck multitude—all, all vanished—and the Dean sat down to tea with Mrs. Trollope.” But just like the ambitious Dr. Grant in Mansfield Park, Dean Trollope is soon a victim of his appetite: “The dean sat down to a repast which bishops might have envied. The bottled ale was excellent—the ducks roasted to a turn—the fricasseed veal and scalloped oysters were not to be resisted—and, to crown the whole, such stewed cheese had never been tasted; no, not even at the table of his Grace the Archbishop…”

The following morning, Dean Trollope’s “six brown bays [of his coach and six] were waiting…[but] The Dean was already called another way, had already commenced another journey. In the middle of the night the gout had seized his stomach; and, at half past eight o’clock in the morning—he died!” The mystery unveiled! (ie, spoilers)

Lord Layton, the rejected suitor, goes off and drinks himself to death. His father, Lord Merefield, summons Henry Darleville to his side and asks to hear his backstory. Turns out Merefield was quite struck by how much Darleville resembles.... himself! Henry explains his mother never told him who she was or who his father was, but she left a sealed packet with him that was only to be opened if someone who claimed to know her asked to see it. (Henry is such a mama’s boy). “That mother, that dear and tender mother, fond idol of my affection!-"

“—Was my wife!” groaned Lord Merefield, “my disgraced, my innocent, my murdered wife!” –clasping his hands on his forehead, he rushed out of the room, leaving Darleville aghast, stupefied with horror and surprise.”

Meaning, in other words, that his recently deceased wastrel son was the product of Lord Merefield’s second, bigamous marriage, while Henry, the son of his first wife, is the proper heir.

It turns out Henry’s mother agreed to leave her home after Lord Merefield saw her being embraced by her long-lost first love (who did not die in a shipwreck, as she thought). Since she had fainted when she saw William Daubeney, she was not responsible for the embrace--he embraced her. But Merefield assumed the worst, of course, and even questioned the paternity of the child she was carrying.

Henry’s mother never attempted to reconcile with her husband, she never prevented him from entering into a second, bigamous marriage, she never saw her long-lost love William again. She spent the rest of her life being gently sorrowful behind the high walls of her country home, and condemning her son, the true heir, to COVID-like social isolation for his entire life. Because this, folks, is true feminine delicacy. “”[W]hilst her husband continued to view her as a criminal, could she wish her name, her history, to appear to the world! One thing only she intreated—if, by any happy accident, [her husband] should become convinced of her innocence, she implored him to inform her that her purity was no longer doubted.”

Anyway, now that Henry's the new Lord Layton and the future Lord Merefield, Henry is worthy to address Cecilia. Her guardian, lawyer Fusby, gets busy drawing up the elaborate marriage articles, and the pair are happily wed. Cue the Welsh harpists and dancers legging it to Of Noble Race was Shenkin. As a love story, Cecily Fitz-Owen is rather tqme. You don't really see hero and heroine falling in love with each other.

Cecily, our heroine, is no shrinking violet. She is observant, compassionate, and she shows firmness in turning down unwanted suitors.

Henry Darleville the hero is not called upon to do anything but try and cheer up a little. He, like Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility, is released by circumstances. Like Edward he shuns a public life and just wants domestic happiness.”

The narrator tends to hop from one topic to another, but there are many fine flourishes of prose, such as in the Dickensian opening description of Cecilia’s guardians: “Counsellor Fusby talked! Counsellor Fusby blustered! Counsellor Fusby fumed! But all was going wrong, till, on cross-examining the adversary’s evidence, three witnesses were leered out of their testimony by the wily glance of his eye, and there more were sunk to the bottom of the witness-box by the dignity of his frown."

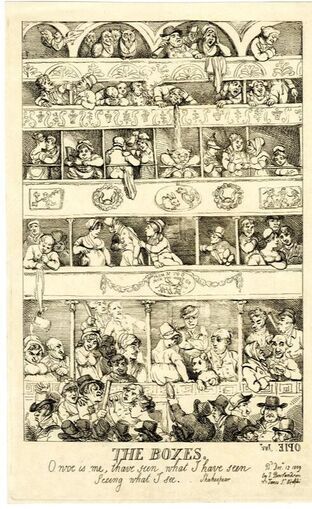

Other featuresWe have many examples of marriages contracted for mercenary or ambitious motives in this novel. Marrying without love is bad, but so is expecting to live on love and romance. Cecily’s wise mentor Mrs. Delamere (who enjoys one of the few happy marriages in the book) advises Cecily to cultivate her own interests and not live exclusively for her husband. This way, they won’t get tired of each other and secondly, if she is widowed, she will have avocations and people to live for. Cecily also learns a valuable lesson when she briefly visits an unhappy couple, the Treadrairs: “the systematic art of habitually teasing—of consenting to be perpetually miserable, on condition of being able to inflict perpetual misery on others, was, to her, equally new and horrible. In Mrs. Treadrair was beheld a disposition, wantonly prepared to feel anger at whatever should occur; resolutely bent on being dissatisfied, and the only gratification she could enjoy in return, was the satisfaction to think, that whilst she vented her spleen on others, she, in some degree, decreased her own misery, and, in a still greater degree, created misery in them.”I can’t believe what it was like to attend a playhouse in those days. Everybody just chatted throughout the performance! The author describes the conversations that go on all around the heroine and her mentor host and hostess, but the Delameres also carry on long conversations with Cecily, explaining the characters and faults of the people she’s overhearing. We have effete fops from the city: (“Why, just so: --breakfast at two;--Park—Broad-Street—St. James’s—auction—curricle—picture-gallery, till six; --dine till ten;--play—opera—coffee-house, till twelve’ –gaming till four; --and da capo—da capo—da capo.—Oh, tis horrid!”) or ignorant country squires who talk of nothing but horses and hunting. There's gamblers, there's a know-it-all. The women are all equally contemptible or silly.Some modern scholars have claimed to find lesbian undertones in Emma and Mansfield Park. Hey guys--check out how Henry talks about parting from his best friend Henry Carlton “the hour of parting was to me an hour of anguish” and reuniting with him: “I folded him in my arms.”The author works in an incest tease--oddly popular in those days--because Henry Darleville’s first love Julia is the daughter of Sir William Daubeney. When Henry’s mother hears the name “William Daubeney,” she faints, and Sir William turns pale when he meets Henry. The mystery is only cleared upon later, but leaves the reader to speculate that Julia and Henry are half-siblings.Fornication and adultery and social class: Fanny O'Byrne the milliner lived in sin with Captain Crawford. Had she been a woman of higher social standing, I think the author would have been obliged to kill her off. Because of their disparity in social class, Cecily can become Fanny's patron, but never her friend. Julia, the hero's first love, makes a glittering marriage and then commits adultery just one time with Henry Carlton. Out of remorse she goes off and lives in seclusion in the country. She and Henry Darleville, her first love, will never find their way back to each other. She is now beyond the pale.

Other featuresWe have many examples of marriages contracted for mercenary or ambitious motives in this novel. Marrying without love is bad, but so is expecting to live on love and romance. Cecily’s wise mentor Mrs. Delamere (who enjoys one of the few happy marriages in the book) advises Cecily to cultivate her own interests and not live exclusively for her husband. This way, they won’t get tired of each other and secondly, if she is widowed, she will have avocations and people to live for. Cecily also learns a valuable lesson when she briefly visits an unhappy couple, the Treadrairs: “the systematic art of habitually teasing—of consenting to be perpetually miserable, on condition of being able to inflict perpetual misery on others, was, to her, equally new and horrible. In Mrs. Treadrair was beheld a disposition, wantonly prepared to feel anger at whatever should occur; resolutely bent on being dissatisfied, and the only gratification she could enjoy in return, was the satisfaction to think, that whilst she vented her spleen on others, she, in some degree, decreased her own misery, and, in a still greater degree, created misery in them.”I can’t believe what it was like to attend a playhouse in those days. Everybody just chatted throughout the performance! The author describes the conversations that go on all around the heroine and her mentor host and hostess, but the Delameres also carry on long conversations with Cecily, explaining the characters and faults of the people she’s overhearing. We have effete fops from the city: (“Why, just so: --breakfast at two;--Park—Broad-Street—St. James’s—auction—curricle—picture-gallery, till six; --dine till ten;--play—opera—coffee-house, till twelve’ –gaming till four; --and da capo—da capo—da capo.—Oh, tis horrid!”) or ignorant country squires who talk of nothing but horses and hunting. There's gamblers, there's a know-it-all. The women are all equally contemptible or silly.Some modern scholars have claimed to find lesbian undertones in Emma and Mansfield Park. Hey guys--check out how Henry talks about parting from his best friend Henry Carlton “the hour of parting was to me an hour of anguish” and reuniting with him: “I folded him in my arms.”The author works in an incest tease--oddly popular in those days--because Henry Darleville’s first love Julia is the daughter of Sir William Daubeney. When Henry’s mother hears the name “William Daubeney,” she faints, and Sir William turns pale when he meets Henry. The mystery is only cleared upon later, but leaves the reader to speculate that Julia and Henry are half-siblings.Fornication and adultery and social class: Fanny O'Byrne the milliner lived in sin with Captain Crawford. Had she been a woman of higher social standing, I think the author would have been obliged to kill her off. Because of their disparity in social class, Cecily can become Fanny's patron, but never her friend. Julia, the hero's first love, makes a glittering marriage and then commits adultery just one time with Henry Carlton. Out of remorse she goes off and lives in seclusion in the country. She and Henry Darleville, her first love, will never find their way back to each other. She is now beyond the pale.

About the author/contemporary reviews

About the author/contemporary reviews The author is anonymous and no other novels have been attributed to him/her. Somewhere along the line, the author was identified by one name: “Frank,” but that name does not appear on the title page and I don’t how this suggestion originated.