Lona Manning's Blog, page 3

May 6, 2025

CMP#217 Eliza Kirkham Mathews Attributions

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#217 A Tribute to Eliza Kirkham Mathews, or rather, Attributions to Eliza Kirkham Mathews

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#217 A Tribute to Eliza Kirkham Mathews, or rather, Attributions to Eliza Kirkham Mathews

EKM at work in York. ChatGPT Image I'm briefly interrupting my read-through of novels which may have been written by the authoress of The Woman of Colour, to return to an authoress for whom I have a real soft spot. Not long ago, I posted about the obscure Regency poet and novelist Eliza Kirkham Mathews (EKM) (1772-1802), who lingers in my affections, not for her writing--which never, in my opinion rises above mediocrity--but for the touching story of her brief life. She is best known for her 1801 novel, What Has Been, a heartfelt but hackneyed sentimental novel with many autobiographical elements. Chawton House is bringing out a scholarly edition of this novel this September (see below for more info).

EKM at work in York. ChatGPT Image I'm briefly interrupting my read-through of novels which may have been written by the authoress of The Woman of Colour, to return to an authoress for whom I have a real soft spot. Not long ago, I posted about the obscure Regency poet and novelist Eliza Kirkham Mathews (EKM) (1772-1802), who lingers in my affections, not for her writing--which never, in my opinion rises above mediocrity--but for the touching story of her brief life. She is best known for her 1801 novel, What Has Been, a heartfelt but hackneyed sentimental novel with many autobiographical elements. Chawton House is bringing out a scholarly edition of this novel this September (see below for more info).I was both interested and touched to learn that some of EKM’s unpublished manuscripts survive to this day. The London-based firm, Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers, recently offered for sale one of Mathews’ manuscripts, probably written when she was in her early twenties. It is a gothic novel, titled Romance of the Turret or, Anecdotes of a Catholic Family. According to Jarndyce, the novel features a vulnerable foundling heroine, a haunted Abbey, a garrulous servant, an evil priest, an incest tease, and some violent subplots. In other words, it’s a typical Gothic novel. The manuscript has been acquired by Yale University and is held at its Lewis Walpole library.

Someone valued this manuscript enough to carefully preserve it. If EKM wrote it around 1798, then it was after her 1797 marriage to Charles Mathews, a comic actor. The newly-married couple visited his family in London, then Mathews joined a provincial theatre circuit which toured Hull, then York. While he was making his name on the stage, Eliza aspired to earn income with her pen... Naturally, the curators at Jarndyce wanted to publish a list of EKM’s published works in their advertisement—the problem is, there is a lot of confusion around what EKM wrote and what has been misattributed to her, and in at least one case a title she wrote was attributed to someone else. I mentioned this confusion in an earlier post. I agree with the Orlando Database of Women’s Writing in the British Isles that there is no question about some of doubtful attributions, and yet, in library catalogues, you will still see titles attributed to EKM which were actually written by Laetitia Matilda Hawkins. As well, a novel written by EKM has been attributed to Anne Jackson, the second wife and biographer of Charles Mathews.

35 Stonegate, York, circa 1802 ChatGPT image Searching for the author's fingerprint

35 Stonegate, York, circa 1802 ChatGPT image Searching for the author's fingerprintSo, I decided to experiment with AI to help me compare the themes, style, sentence structure and grammar of these mis-attributed works to EKM’s writing. I don’t leave it all up to AI, however, as I have learned that it is not a magic bullet for analysis. I have read every novel I discuss and scrutinized. Basically, AI is teaching me about grammar (i.e. sentence structure), style, and how to describe the differences that I observe between the various novels.

The best sample we have of Mathews’ writing is her novel What Has Been, published shortly before she died. The preparation and publication of What Has Been is documented in the memoir of Charles Mathews, as recounted by his second wife, Anne Jackson Mathews. Therefore, the text of this novel can be compared to the other works attributed to EKM. Further, EKM used some of her own poetry and her own life story, which establishes her authorship.

I asked ChatGPT to compare What Has Been to the novel Constance, published anonymously in 1785. Although every library catalogue I’ve seen attributes Constance to Mathews, one strong argument against her authorship is that EKM was only 13 years old in 1785. Therefore, these two novels provide a good starting point to experiment with Chat GPT's discrimination in comparing texts.

After using Constance to demonstrate how the two novels came from different hands, I’ll compare What Has Been to a gothic novel titled The Phantom, which was published in 1825. After that, we’ll look at two Gothic (or at least Gothic-y) novels probably written by EKM, and her children's books.

Apothecary's trade card, British Museum More about Eliza Kirkham Mathews

Apothecary's trade card, British Museum More about Eliza Kirkham MathewsNovelistic melodrama? Well, Eliza herself was thrown penniless upon the world in her early twenties. After losing every member of her immediate family, EKM supported herself by working as a school teacher. When she married the aspiring actor Charles Mathews, she had no money and he had only 12 shillings a week to live upon. In 1801 EKM was living in York with Charles, and after an evening of making people laugh at the Theatre Royal, he would return to the small upstairs apartment he shared with Eliza, where she was wasting away from tuberculosis. Soon the couple were sinking into debt while Eliza wrote furiously in their little apartment at 35 Stonegate. His second wife suggests that EKM kept the secret of the household debts from her husband, and sacrificed her health in a vain attempt to succeed as an author.

Eleven days before Eliza died, Charles wrote a friend: “I have had the best advice I could procure; but all the medical men I have employed are of the opinion she cannot recover, and it appears to me impossible that she can.” In addition to the sleepless nights and anxiety over his wife, money troubles plagued him: “You may judge yourself how heavily it must fall on a country actor—six months’ apothecaries bills, with the mortifying reflection that all such assistance is in vain.” I believe that then, and subsequently, Charles really felt for Eliza and wanted to help her make her dreams of published authorship come true. True, in the memoir written by the second Mrs. Mathews, she indicates that neither Charles, nor his brother William who acted as Eliza’s agent in London, were much impressed with What Has Been. The Orlando database is properly indignant on EKM's behalf about Anne Mathews’ condescending attitude; but I have to say I agree with Charles and his brother. What Has Been is a conventional, stilted, and hackneyed work whose main interest derives from its autobiographical elements.

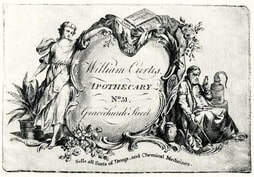

The opening of Romance of the Turret (the unpublished manuscript)

The morning was cheerless; surrounding objects but faintly distinguished when the carriage which was to convey Margaret De Berry from the scenes where she had passed the happy and sportive days of childhood drew up to the residence of her late beloved friend and generous benefactress [Miss Mortimer]. Margaret’s heart trembled within her and the long restrained tears fell from her eyes as she descended the stairs and stopped to take a last look and last farewell of the apartment which was once occupied by her departed friend. “Alas! Sighed she “never more shall I listen to the tones of that soothing voice which has so often conveyed instruction to my mind—never more shall I gaze…."

This is an opening like the novel First Impressions or Emily Willis (and no doubt many others) in which a girl has been kept in ignorance of her parentage and tragically loses her guardian and mentor at the outset of the novel, plunging her unprotected into the world. Her place in life is uncertain and she might even be illegitimate: "‘[I]n what dreadful mystery is my fate involved?’ Margaret asks. "‘Was the being who gave me birth one who had forfeited the respect of her family and friends? Am I the wretched offspring of guilt?’"

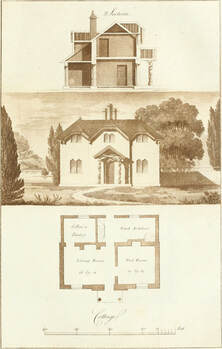

35 Stonegate today Scholarly edition of What Has Been

35 Stonegate today Scholarly edition of What Has BeenHere is more information about the forthcoming academic edition from Chawton House Library, published through Routledge: "What Has Been, originally published in 1801, is an affecting, lively, and accessible read for scholars and students of the long eighteenth century. This critical edition includes an extensive introduction, notes, and appendices [by Jonathan Sadow and Elizabeth Neiman]. Eliza Kirkham Mathews' portrait of a struggling female novelist connects and also distinguishes What Has Been from novels by now-canonical female authors of this period. Simultaneously, it provides a new vantage-point for assessing obscure or long-forgotten novels. This volume will be of great interest to teachers and scholars of the long-eighteenth century and Romantic era, and on such far-ranging topics as the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century novel, British Romanticism, feminism, women's literature, the gothic, and the 'novel of purpose' or Jacobin/anti-Jacobin novel."

As I discussed in my own review of What Has Been, Emily Ormand, the main character, must support herself or starve, but she can't bring herself to work as a governess or a seamstress. She hopes to become a novelist. In the book, she receives encouragement from a London publisher, but he tells her that her book "wants connection." I have looked up other examples of the phrase "wants connection," and the context in which the phrase was used, in other journals of the period, and am satisfied that it means the book lacks continuity. Her plots do tend to lack connection--she will introduce and drop characters, introduce characters who play no real part in the plot for example, she includes a Gothic inset narrative which has nothing to do with the main story. This scene between Emily and her publisher surely derives from Eliza's own life as are other autobiographical details in the book. Some have suggested it is a portrait of William Lane, the proprietor of the Minerva Press, or perhaps it is a tribute to Thomas Wilson, a publisher in York, who brought out four children's books attributed to her. Previous post: The Aunt and the Niece Next post: Constance vs What Has Been--different hands?

Published on May 06, 2025 00:00

April 30, 2025

CMP#216 Clara, the "interesting" heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#216 The [Villainous] Aunt and the [Boring?] Niece (1804), by Anonymous

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#216 The [Villainous] Aunt and the [Boring?] Niece (1804), by Anonymous

Felicity Jones and Sylvestra Le Touzel as Catherine Morland and Mrs. Allen A naïve young lady travels to Bath with an older female companion and ventures into society. She meets a charming and witty young man. But will her dreams of romance be destroyed when it is discovered that she is not from a wealthy and distinguished family?

Felicity Jones and Sylvestra Le Touzel as Catherine Morland and Mrs. Allen A naïve young lady travels to Bath with an older female companion and ventures into society. She meets a charming and witty young man. But will her dreams of romance be destroyed when it is discovered that she is not from a wealthy and distinguished family?This is not Northanger Abbey, this is The Aunt and the Niece. The Aunt and the Niece was anonymously published in 1804, and was subsequently attributed to the author of Eversfield Abbey (1806), The Woman of Colour (1809), and other novels. If the attribution chain is correct, this authoress moved from Minerva Press (considered to be a low-brow publishing house) to the respectable John Crosby and then to Black, Perry, and Kingsbury, publishers who did not specialize in fiction. Then she went back to Minerva for two more novels. The authoress could be Mrs. Bayfield, but Mrs. E.M. Foster is also tangled up in this chain of attributions--or it might even be a third person whose name has been lost.

The Aunt and the Niece is a brisk-moving two-volume novel with a satisfying amount of drama. Typically of novels of this period, it relies upon untimely death and misunderstanding for its plot, and coincidence for its resolution. The villains are satisfyingly despicable. In fact, the authoress throws some shade at her readers when she suggests that they won't be as interested in the virtuous characters...

Published anonymously Don't laugh, good reader!

Published anonymously Don't laugh, good reader!The authoress turns from describing the machinations of the scheming villains to “return to our interesting heroine.” She adds: “don’t laugh, good reader! –interesting to us, else these her memoirs would not have been written.” This appears to be a meta comment on sentimental novels and "pictures of perfection" heroines. Likewise, the author declines to fully describe the exemplary conduct of the rector in the quiet village where Clara and her mother retreat from the cruel world, because “whatever may be his virtues and his merits, there is little with which to gratify the taste of our polished damsels. We acknowledge ourselves to be in a very awkward predicament, and it is very uncertain if we shall ever recover ourselves.”

The hero, Horace Fairfax, was born in the West Indies, and so he is something of a “hot-brained exotic.” The authoress seems to feel that she ought to have given him more to do in the story. He is attracted to the heroine and then, as is typical, he is briefly estranged from her when she is caught up in a compromising situation. “We have once before apologized about our hero, but if our readers will take him upon trust, we will assure them he promises to be every thing he can wish.” And yet, he is not very different from many other heroes of this era, and he is rather more likeable and charming than many. I think the playful, teasing dialogue between Horace and Clara in Bath convincingly shows two young people who are attracted to one another.

Giving up her independence: Bing AI image The Hand of Providence

Giving up her independence: Bing AI image The Hand of Providence Like the other books in the Foster/Bayfield series which I’ve been examining, there is a strong message of Christian resignation in The Aunt and the Niece. The "Divine Disposer of Events" controls everything, and when bad things happen to good people as –-hoo boy, they certainly do--“Providence always acts in the wisest manner, though we cannot pierce through the veil... we must take care not to arraign Providence.”

This pious resignation might be assumed to include acceptance of the social status quo, but there are two passages where the female villain receives some backhanded sympathy from her author: First, Catherine Fitzallen resents her younger brother Frederic for being the pampered heir: “Seeing in her brother the being who had defeated all her expectations [of being the heiress]… and with a feeling similar to envy, beholding him rioting in dissipations which her sex, and the common usages of society, forbade her to join in, no wonder that Catherine Fitzallan’s disposition grew daily worse.”

Another moment of back-handed sympathy comes after Frederic dies in a pointless duel with his tutor Clifford and Catherine does become the heir. But when she marries Clifford, he took “direction of [Catherine’s] affairs into his own hands… and thus shewing the once independent, now enslaved, Catherine, that the moment a wife marries, she has no longer property, power, even a will of her own.”

So why did Catherine marry the man who killed her brother in a duel, who was her social inferior, and a tyrant? Her husband is blackmailing her! He was the one who deceived Frederic’s widow Angelina into believing that their marriage was just a mock ceremony. She mistakenly thinks their baby daughter, our heroine Clara, is illegitimate. Catherine's reign at Fitzallen Castle is over if the truth comes out. But the secret is safe, because the clergyman who performed the secret ceremony sailed for the West Indies the very next day--

The... West Indies, you say? Yes, where he married a plantation heiress and sired a son. A son? Is his name Horace, by any chance?

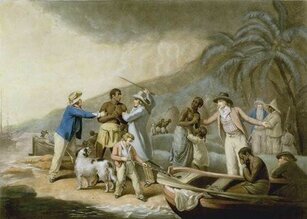

John Raphael Smith after George Morland, The Slave Trade, 1791, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection Small world!

John Raphael Smith after George Morland, The Slave Trade, 1791, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection Small world!Speaking of coincidences, The Woman of Colour also features a character named Angelina who is a poor dependent orphan living with a rich family and bullied by that family's daughter because she's jealous that the man she loves prefers Angelina. Both Angelinas escape their situations by entering into a valid, but clandestine marriage and both are tricked into believing that their husbands deceived them with a sham marriage ceremony.

Also, the evil Catherine of this novel and the heroine Olivia of WOC both learn that their husbands are married to someone else and their marriages really are invalid. And of course, both novels have characters from the West Indies. Unlike The Woman of Colour, however, The Aunt and the Niece has no word of sympathy, or any word at all, for or about enslaved persons. The only use of “enslaved” refers to Catherine’s marriage. In this novel the West Indies is, as is typical, just a convenient place to park a character until he is needed for plot purposes. In this case Horace’s dad returns and assures Angelina that she was lawfully married to Frederic and the Fitzallen estate belongs to her daughter. Clifford escapes when his duplicity is unmasked, Catherine kills herself, and Horace and Clara are happy ever after.

Anti-Catholic imagery: detail of "An escape a la Francoise," Library of Congress Other themes

Anti-Catholic imagery: detail of "An escape a la Francoise," Library of Congress Other themesFainting: Both Clara and her mother faint at times of stress and high drama, for example, when the unprincipled Lord Darnley tries to abduct Clara to have his wicked way with her. There is no indication that either one of them hit the carpet when they get the good news about the inheritance from Reverend Fairfax. At other times, it is quite a burden on the alarmed bystanders to have to drag their supine bodies to the nearest bed or sofa and summon a physician. Fainting appears to be a way of demonstrating helpless vulnerability and a lack of agency in trying situations. I disagree with a recent book which suggests that fainting is a subversive commentary on the use of tight corsets or stays.

Education: The Aunt and the Niece stresses the importance of education in forming character. The author interjects: “‘And did this unheard-of malignity [in Catherine] proceed from natural depravity?’ we may ask, ‘from inherent turpitude?’ –Alas! we know not how to answer. Children of sin from our birth, how early its fatal shoots spring up in the heart we know not… if temperate pruning will not do, even the axe should be laid at the source of the evil—this is certain, and Sir Hugh and Lady Fitzallan, when too late, had reason to wish that mildness had given place to severity, in their treatment of their daughter.” Catherine might have been born a sociopath, but her parents were too gentle with her, and too lax with Frederic. Nature versus nurture, folks. For more about the recurring theme of education in sentimental novels, see my series here.

Thee/Thou: The authoress also follows the common device of having her characters break into biblical language and refer to themselves in the third person in moments of high drama. When the bereaved Angelina kneels by Frederic’s coffin, she exclaims: “the wretched Angelina must now separate from him for ever…. Destitute, fatherless as thou appearest, my babe,” added she, pressing her lips to those of her infant, “yet hast thou an Heavenly Father—one who will still care for thee!” Then she faints.

A French fifth column: Politics briefly intrudes when a minor character, the bigamous Clifford’s French wife, laments that her fellow emigres have behaved badly in England: “Alas! I am the type of my unfortunate, my ungrateful nation… Generously your country [has] opened its arms, and sheltered all our wandering outcasts; and what was its return? –Oh horror! Horror! –shame on civilized, on human beings! –they stung their benefactor; they planted their insidious poison and their fatal tenets [of republicanism] in the heart of that land which supported them, and tried to subvert its laws, its liberty, its religion!” That would put this author in the anti-Jacobin camp.

Illegitimacy: The assumption that Angelina, herself illegitimate, would naturally go on to give birth to an illegitimate daughter, fed into the widely-held belief that wanton behaviour in women was a heritable trait. This is why, in Emma, Mr. Knightley tells Emma that Harriet will be “safe” and beyond the reach of temptation if she marries Robert Martin and goes to live with Martin’s mother and sisters. Further, a girl like Clara, intelligent, well-educated, and genteel, makes for an attractive mistress for a gentleman like Lord Darnley, as opposed to picking up some doxy from the streets. Thus foundling heroines are in constant danger of being insulted by gentleman-cads. Luckily, Clara is not illegitimate and retrieves her good name and the family fortunes. Contemporary Review of The Aunt and the Niece

The Critical Review gave The Aunt and the Niece a favourable if brief review: "Among the numerous works which issue from the prolific brains of those who seek their almost daily bread at the great manufacture in Leadenhall-street, it would be singular if there were not some that rose pre-eminently. Perhaps the volumes before us do not claim such warm panegyric; but, in the plot and management of the story, the author rises above the vulgar herd. The event is sufficiently obvious from the beginning; but the éclaircissement is conducted with skill, neither hurried by precipitation, nor are the means so obvious as to be easily anticipated [really?]. The characters, though sketches only, are well discriminated."

Previous post: Eversfield Abbey In my novel, A Contrary Wind, a variation on Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford spins a web of lies to keep Edmund Bertram for herself. I took the title from Henry Crawford's remark to Fanny, "I think if we had had the disposal of events—if Mansfield Park had had the government of the winds just for a week or two, about the equinox, there would have been a difference. Not that we would have endangered [Sir Thomas's] safety by any tremendous weather—but only by a steady contrary wind, or a calm. I think, Miss Price, we would have indulged ourselves with a week’s calm in the Atlantic at that season.”

Click here for more about my novels.

Published on April 30, 2025 00:00

April 22, 2025

CMP#215 Agnes, the uninvited houseguest

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#215 Eversfield Abbey (1806), or, Agnes, the Uninvited Houseguest

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#215 Eversfield Abbey (1806), or, Agnes, the Uninvited Houseguest

Clandestine marriage, Bing AI image In the last post, I explained that I am reading my way through the novels attributed to Mrs. E.M. Foster and Mrs. E.G. Bayfield, who as far as I know were two different people, although they have been credited with many of the same titles, such as Eversfield Abbey.

Clandestine marriage, Bing AI image In the last post, I explained that I am reading my way through the novels attributed to Mrs. E.M. Foster and Mrs. E.G. Bayfield, who as far as I know were two different people, although they have been credited with many of the same titles, such as Eversfield Abbey.Eversfield Abbey is not a gothic novel, although the heroine, Agnes Eversfield, does venture out alone to the family chapel when she notices candles burning there in the middle of the night. She encounters no mad monks or ghosts but, hiding behind her mother’s memorial urn, she is shocked to see her widowed father marrying a French émigré in a secret midnight ceremony. Mr. Eversfield has been inveigled into the match by the connivance of Father St. Quintin and she feels powerless to interfere.

Agnes is the only child and is therefore the heir to the Eversfield estates--unless of course, another little Eversfield comes along. Dad wants to see her marry her cousin, Sir Barnard. However, just like Mr. Eversfield, Sir Barnard is a Catholic. Our heroine is a Protestant because her late mother was a Protestant. In other words, this novel takes up the issue of mixed marriages which would have been much more controversial at this time. Before her death, Agnes’s mother urged her husband to not pressure Agnes into marrying a Catholic, not even their beloved nephew, without Agnes’ full consent. Agnes loves her cousin like a brother, while he greatly admires her beauty and intelligence and does intend to marry her when they are both older. Fate intervenes...

French émigrés

French émigrés The previous Foster novel I read featured three characters from the West Indies. This novel features three émigrés fleeing the French Revolution. Agnes’s father is a kindly but weak man and when his lifelong spiritual advisor and mentor, Father Netherex, exits the story to look after an ailing brother in Scotland, he welcomes a stranger as a substitute. The insinuating St. Quintin introduces a widowed mother and daughter, who claim to be exiled French aristocrats. From there, Agnes must contend with a cascade of unfortunate events.

Mme. Villeroy, as we saw, soon marries Mr. Everfield in a hasty midnight ceremony and her pretty daughter Julie captivates Sir Barnard. Agnes watches all this happen with much dismay but her respectful duty to her father prevents her from protesting. Her one consolation is the mutual admiration that grows between herself and Sir Barnard’s friend Hampden Carlisle. Hampden is brusque but highly principled. He spends most of the novel convinced that Agnes is in love with her cousin, and god forbid Agnes should openly and plainly tell him that no, she doesn’t love her cousin in that way. “To time then she trusted for an éclaircissement, for it was impossible for her to take any steps toward it.” Just impossible!

The subplot involves another cousin—the witty, headstrong Mary Hotham who rebelliously elopes with a tradesman’s son. Mr. Eversfield generously buys him a lieutenant’s commission to set up the young couple in respectable circumstances. At the request of Mary's mother, Agnes goes to visit them. Hoping for the best, she is disappointed and then repulsed by Lt. Benson’s vulgarity and profligacy.

Hampden Carlisle’s older brother just happens to be Benson's superior officer, and this older brother is a rake who sets his sights on the newlywed Mary. Mary, meanwhile, quickly realizes she married a boorish idiot, but she is too proud to admit it or to go back to her mother to beg for forgiveness.

A word on 19th century visiting etiquette; it seems a little odd that Agnes goes to visit Mary and her husband without even sending a line in advance. She stays with them for weeks, disapprovingly watching and sometimes remonstrating as they burn through Mary’s five hundred pound inheritance. So just as in Light and Shade and Black Rock House , the reader is entertained (yawn) with scenes featuring the drunken and self-indulgent antics of British army officers as they go from the ballroom to the playhouse to the gaming tables.

Class snobbery

Class snobbery The author is not subtle about mocking the boorish manners of the lower classes, as in the case of Mrs. Jenkins, a pushy and vulgar Bristol cheesemonger’s wife, the sister of Lt. Benson. “The ignorant confidence of Mrs. Jenkins disgusted our heroine…the manners of this woman were of a description to which Agnes had hitherto been an utter stranger. –She had often visited the huts of the ignorant and the poor; she had heard their coarse language, and witnessed their uncouth manners, but humility, a consciousness of inferiority, and a wish of obliging, had in general marked their deportment; and the disgust with which she recoiled from Mrs. Jenkins, she had never yet experienced towards the poorest peasant, or any human being.”

“The wife of a cheesemonger may be a very respectable and estimable woman,” [Agnes tells herself] “and ill should I have profited by the good counsels of my [dead mother] if I could not look with satisfaction and pleasure on the sons and daughters of industry! The profession of a soldier, though it has given [Mary’s husband] Benson a red coat, cannot give him either the ideas or the manners of a gentleman; he is still fitted only to move in the sphere of his sister, and that sister would always have disgusted me...” Mrs. Jenkins is also fat, with a “waddling figure” and “short fat arm[s].”

Style: Long sentences and lots of italics French gold-diggers

Style: Long sentences and lots of italics French gold-diggers Meanwhile, Agnes’s new French stepmother drops her mask of refined piety and plunges into a vortex of dissipation in Bath where she parties and gambles all night. Sir Barnard marries young Julie and immediately regrets it when she also shows herself in her true colours. What a mess. The stress causes the roses to flee from Agnes’ cheeks (as with most novels of this era, much attention is paid to the heroine’s complexion, whether it be forlorn and pale or “celestial ruby red.”) At one point, Hampden undiplomatically tells her: “Your appearance tells me that you have to thank me for a sleepless night.”

Mr. Eversfield, despairing, returns to Eversfield Abbey, leaving his heartless wife in Bath. Agnes rushes back to his side. In her haste, she decides to travel alone and unprotected. She stays overnight at an inn in Bristol where Sir Barnard just happens to be passing through and where Hampden Carlise just happens to drop in. He catches Agnes and Sir Barnard holding hands as they console one another. As she leaves, Hampden berates Agnes: “I beseech you, Agnes Eversfield, tempt not your fate—by the pity, the reverence which I once felt for you… I then beheld you as a suffering angel—but now—to pursue—to follow a man who is become the husband of another!”

Falsely accused, Agnes is too upset and insulted to explain herself. Luckily Sir Barnard and other witnesses clear her name. Hampden sends her a letter of apology. I will say that unlike many other heroes, Hampden is a man of action, always showing up in moments of crisis.

Sir Barnard despairs but is rescued by Father Netherex Villainy unmasked

Sir Barnard despairs but is rescued by Father Netherex Villainy unmaskedLt. Benson, having spent all of Mary’s money, abandons her. She is about to become Captain Carlisle’s mistress when Hampden shows up and pleads with his brother and with Mary to back away from the fateful step. Overcome with shame for her filial disobedience, her spendthrift folly and her brush with adultery, Mary runs away. She hides her identity and works briefly as a housemaid in a remote farmhouse, where she swiftly dies of consumption and remorse.

Mr. Eversfield has a stroke and lies dying as word comes that St. Quintin has been unmasked as an imposter—he’s not a priest at all, but a dissolute French aristocrat. The three French emigres flee with all the money and jewelry they can lay their hands on. The mother was in fact an Italian opera singer, the mistress of St. Quintin, and Julie was her daughter by a German fiddler. “[T]he daughter of a fiddler and a singer-–and my wife!” Sir Barnard exclaims. “Does such a creature bear my name! Heavenly powers! I cannot live to bear it!”

Fortunately, the real Catholic priest, Father Netherex, returns at last to point out that since St. Quintin was not a priest, the marriages are invalid. He also offers spiritual consolation: “We are born to suffer, for this we are sent into the world, and he that best bears the portion of human woe assigned him here, is the best prepared to enter those blessed mansions where sorrow can never come.”

Sir Barnard is a free man, but Agnes is already head over heels for Hampden Carlisle and he for her. Once she is past her mourning period for her father, they marry, and we are told that Sir Barnard might marry Hampden’s sister if she will agree to marry a Catholic. Contemporary review of Eversfield Abbey

The Monthly Review said: “Strong colours are here employed in pourtraying the opposite characters of the heroine Agnes Eversfield, and her cousin Mary Hotham; the one is a pattern of piety, meekness, forbearance, resignation, patience, and obedience to her parents; while the other is confident, impetuous, inflexible, excentric [sic], romantic, and undutiful. In the happiness which attends the former, and the misery which overwhelms the latter, the young female reader may learn an excellent lesson to direct her through life.” You might think from this description that Agnes is an irritating milquetoast, but she is not. She is compassionate, but also rational and resolute, within the strict gender roles prescribed for her time.

The Woman of Colour's title page claims that it was written by the author of "Ebersfield [sic] Abbey," "Light and Shade," and "The Aunt and the Neice." All three novels were published anonymously.

Previous post: Review of Light and Shade Tom Bertram is the insouciant oldest son of the Bertram family, in Mansfield Park. In my short story about Tom in the Quill Ink anthology: Dangerous to Know: Jane Austen’s Rakes & Gentlemen Rogues, Tom falls in love with a beautiful French émigré who is not quite what she seems. More about the Quill Ink anthologies here.

An earlier guest post by me about the émigrés who fled to England during the French Revolution.

Published on April 22, 2025 00:00

April 10, 2025

CMP#214 Mrs. Foster has thoughts

“Purvis," said Mrs. Robinson, putting her spoon into her cup, "you positively make no more tea for me; you have no compassion on my poor nerves.”

“Purvis," said Mrs. Robinson, putting her spoon into her cup, "you positively make no more tea for me; you have no compassion on my poor nerves.” -- from Light and Shade, at a tea party scene where the guests include Sir Montagu D'Arcy

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

CMP #214: Mrs. Foster has thoughts: review of Light and Shade, 1803

CMP #214: Mrs. Foster has thoughts: review of Light and Shade, 1803 Of the several thousand novels published during the long eighteenth century, The Woman of Colour has a special place in the hearts of the academy because the protagonist is a woman of colour. I reviewed the novel here. Some academics speculate that the author of The Woman of Colour might actually be a woman of colour. I will weigh up the case for that, but Mrs. E.M. Foster and Mrs. E.G. Bayfield are top candidates for the answer to the question: “who wrote The Woman of Colour”?

Therefore, I am following the tangled trail of title page attributions and—here’s a novel thought—actually reading the books authored by Foster and Bayfield to look for similarities with The Woman of Colour in language, plot, tropes, and themes...

Trope-tastic

Trope-tasticFor example, I previously read Miriam, another of Mrs. Foster’s novels ( and reviewed it here ). In both that novel and in Light and Shade, we have a strong emphasis on submission to the will of God. We have a leading man haunted by a secret sorrow. We have an orphaned heroine. We have some remarkable coincidences of the “small world” variety. We have contrived misunderstandings between hero and heroine which delay their happiness until the last chapters of the final volume. You might think that I am being condescending here, but actually, I enjoyed the story and whizzed through all four volumes. I guess the reason that romance authors keep repeating these tropes is because they work! The reader is engaged by them.

I am not going to reiterate the entire plot, except to remark that it has more drama than you will find in Austen. There are several romantic triangles, three elopements, a madwoman in the attic and a murder. Instead, I want to share another aspect of this novel: in contrast to Austen, a lot of Light and Shade is taken up with current events and Mrs. Foster’s opinion of them, The narrator frequently breaks away to, as they used to say in those days, “shoot folly as it flies,” (quoting Pope) or to “lash the follies of the times" (quoting Otway). For example, the narrator praises the hero as one whose manners were a happy balance between “the formal precision and officious politeness of the last age, and the churlish rudeness and studied negligence which so disgraces this.”

The villain of the novel is a farmer who tries to profit off rising wheat prices when the poor people in his county are starving. The heroine indignantly thinks: “[T]he man who can inhumanly treasure up that [wheat], waiting for a higher price, when he may already get an almost exorbitant one for every grain of it; the man who can, unmoved, behold the poor around him, dying for want to that bread which he withholds from them; he who refuses to part with a scanty portion… to the labourer who tilled the ground, who sowed, who reaped it for him…"

In other words we have a female author who is not afraid of expressing her opinions. Of course, these editorials, along with the minor characters who are brought on to illustrate some specific vice or folly, help to expand the story to four volumes. But these digressions are also what make the forgotten sentimental novels of Austen’s time a repository of opinion on the issues and fads of the past. So, without further ado, Mrs. Foster’s thoughts on:

Impetuous West Indian, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University West Indians

Impetuous West Indian, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University West IndiansThere are three wealthy West Indians in this novel, and they are all portrayed as being impetuous, unthinking, and careless with their money. Cary Saville, a young heir, “was a West-Indian, with all the quickness and instability of the character; his understanding was not of that cast which is competent for sound judgment or deep disquisition, it was rather the volatile spirit, which hastily skimmed he superficies of a subject, and staid not to examine causes or effects…. He was profuse even to prodigality….” Two heiresses (one with a “clear brown” complexion and "black" eyes), impulsively elope without the consent of their parents or guardian. Authors in general disapprove of elopements and usually mete out disaster to the female characters who indulge in them. Murtha Stanley dies and her cousin Jemima Caruthers is headed for divorce and disgrace as the novel closes.

There is no condemnation of slavery in this novel, or mention of emancipation. On the other hand, the narrator specifies that a minor off-stage character, Mr. Selwood, “returned from India some years [ago] with a handsome fortune, honourably acquired." The emphasis on “honourably” must be an implicit reference to controversy around the English presence in India. Proto-feminism

Volume I chronicles the blighted hopes of Clara Mortimer, whose heart is broken when Cary Saville, her childhood sweetheart, marries Murtha instead. After Cary and Murtha run through their fortunes and die of the mad whirlpool of dissipation (as one does), Clara brings up their surviving daughter, named Cary after her father. Herself an orphan, left with a modest inheritance from her late guardian, Clara realizes that there are advantages to being alone in the world: “When she reflected on her own situation, a feeling of liberty, of independence, unknown before, infused a warm glow on her heart; to have her time her own, to nurse her darling girl, to visit the houses of the poor peasantry, to take long and solitary rambles unchecked by the idea of hours, or of being unaccountable to any being for her absence; surely all this would be delightful.” Clara Mortimer looks for a good education for Clary and finds a headmistress who “cultivated the humane propensities of the heart, but at the same time she repressed the enervating indulgence of sensibility and sentiment and… urged a decisive, a steady, and a rational deportment.”

The ideal marriage

Though this is a marriage plot novel, there are several unhappy marriages and Foster doesn’t shy away from depicting domestic abuse. A minor character “had more than once had the cowardice and barbarity to strike his helpless wife.” His second wife becomes a hopeless drudge, worn down by endless pregnancies and unending labour.

In Mansfield Park, Austen mentioned the double standard around infidelity. Mrs. Foster is even more explicit: “Though Mrs. Robinson be excluded from the company of modest women; yet such is the corruption and contradiction of the times, all doors are opened to Major Turton; and the hours are consumed by his miserable victim [i.e. Mrs. Robinson] in the sharpest mental misery [i.e. jealousy and shame].”

These tragic examples of unhappy marriage demonstrate why heroines must choose their husbands carefully, because the law and the Church of England decreed that husbands must be obeyed. For our happy ending, Cary Saville "(now Lady Aubrey) remembers that she is the ‘weaker vessel.’ In all cases of doubt it is at once her pride and delight to apply for the advice and the approving assent of her husband.”

"A boarding school miss taking an evening lesson," Lewis Walpole library, Yale University Modern education

"A boarding school miss taking an evening lesson," Lewis Walpole library, Yale University Modern education“[A] boarding-school education is now so much the fashion (or, if you like it better, the rage), that from the shoe-maker to the tailor all the young ladies are sent to the academy and seminary to be instructed in affectation, and in a perfect contempt of the plebian occupation of their Papas.”

In my earlier series on female education , I learned that many novels were taken up with the issue of how females should be educated. Mrs. Foster spends a lot of time on this. You’ll recall Austen’s mini-editorial about boarding schools in Emma; Forster goes on for several chapters about how females should be raised as “reasonable" beings. She uses some heavy-handed satire to portray two defective boarding schools.

Charity

In my earlier series on charity, I explored how authors used charitable visits to establish the bona fides of the virtuous heroine. Often, charity is reserved for the “deserving poor,” but the virtuous characters in Light and Shade don’t make this distinction. When Farmer Greenfield declares the poor “are a pack of abusive unthankful wretches,” the benevolent Sir Edward shoots back with: “We will not talk of their deserts… there are good and bad indiscriminately mixed in all ranks of life.”

Narrative technique

Forster’s narrator frequently interrupts the story to address the reader and to imagine the reader answering back and commenting upon the story. Her imagined reader exclaims “I’m sick to death of the vile low stuff, the highest character here is a vile country parson…” The narrator comes back with “I am willing to ask Miss Quality-Airs… if she would require an author or an authoress to write on subjects with which he or she is wholly unacquainted. The painter of Nature must often descend to the lower walks of life…”. Then she explains that the heroine’s hero will soon show up. Another author who used this technique was Jane Smith, using her alter ego of Prudentia Homespun.

Mrs. Foster deliberately referenced contemporary controversies. If Jane Austen had done the same; had she devoted her attention to this season’s fashion or this month’s political scandal, perhaps her works would not have survived to become called “timeless” classics.

Featured in Light and Shade: the craze for Perkins Patent Metal Tractors, a quack cure for everything About the author

Featured in Light and Shade: the craze for Perkins Patent Metal Tractors, a quack cure for everything About the authorNothing is known about Mrs. E.M. Foster, I believe, except from the opinions that can be gleaned from her novels. Devoutly Christian, she was socially conservative in many ways but also has been described as a proto-feminist. She authored 14 novels. The title--Light and Shade--is Foster’s reference to the fact that she did not create characters who were “pictures of perfection.” She wrote some historical novels but she specialized in relatively realistic social dramas.

The Critical Review commended Light and Shade as being “lively, pleasing, and interesting.” I agree—except for the scenes set in Teignmouth with a gaggle of good-for-nothing fashionable swains, I was interested in the story and the outcome. The Critical Review surmised that some of the “peculiarly striking” characters “must be portraits,” that is, they must be portraits of real people the author knew. I had the same thought, particularly in regards to the minor character of Purvis, a well-intentioned but weak young man who fritters away his inheritance.

So, what about similarities to The Woman of Colour? I will do some more research before sharing my conclusions.

Previous post: Guest post: Dick and Richard

Previous post: Guest post: Dick and Richard

Published on April 10, 2025 00:00

April 1, 2025

CMP#213 Guest post: Dick and Richard

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Today I am pleased to share a thought-provoking guest post by Prof. Lily A. Soda, on the hidden political message behind Austen's harsh comments about Dick Musgrove in Persuasion. CMP#213 Guest Editorial: The reason for Dick Musgrove in Persuasion

Fat Shaming: Mrs. Musgrove's "large fat sighings" over Dick Many of Jane Austen’s devoted readers feel surprise and consternation over the passages in Persuasion about "troublesome, hopeless" Dick, the deceased son of the Musgrove family, along with the mocking depiction of his sorrowful mother. Austen doesn’t pull her punches in describing Dick as “stupid and unmanageable" and as someone who "had been very little cared for at any time by his family, though quite as much as he deserved.” His death far from home was “scarcely at all regretted.”

Fat Shaming: Mrs. Musgrove's "large fat sighings" over Dick Many of Jane Austen’s devoted readers feel surprise and consternation over the passages in Persuasion about "troublesome, hopeless" Dick, the deceased son of the Musgrove family, along with the mocking depiction of his sorrowful mother. Austen doesn’t pull her punches in describing Dick as “stupid and unmanageable" and as someone who "had been very little cared for at any time by his family, though quite as much as he deserved.” His death far from home was “scarcely at all regretted.” Some scholars have surmised that, had Austen not been in the throes of her final illness, she would have revised her callous descriptions or excised them altogether. Others have speculated about why Austen inserted these harsh passages in a novel famous for its gentle heroine and its wistful tone.

Could it be that these strongly-worded passages hint at something Austen felt strongly about? Her seemingly out-of-place attack on the Musgroves is intended to catch the reader’s attention, to provoke them to pause and probe beyond the liminal space of the Musgrove's drawing room and to confront the costs of empire which supports their way of life. Indeed, we were mistaken in taking these passages at face value.

Dick Musgrove may well have been a satiric, inverted portrait of a real-life Richard who served in the Navy—Richard Parker, infamous in Austen’s time but forgotten today.

In 1797, the British were weary of the ongoing conflict with France, the resources of the Navy were stretched to the limit and the respectful petitions of sailors for a raise in pay were ignored. In April, hundreds of British sailors mutinied at Portsmouth (known of course to Austen readers as Fanny Price’s birthplace). This mutiny, known as the Spithead mutiny, was peacefully settled with some concessions. In May, the crews of ships anchored in the Thames also staged a mutiny, known as the Nore or Sheerness mutiny. They blockaded the Thames and prevented ship traffic from reaching or leaving London.

In 1797, the British were weary of the ongoing conflict with France, the resources of the Navy were stretched to the limit and the respectful petitions of sailors for a raise in pay were ignored. In April, hundreds of British sailors mutinied at Portsmouth (known of course to Austen readers as Fanny Price’s birthplace). This mutiny, known as the Spithead mutiny, was peacefully settled with some concessions. In May, the crews of ships anchored in the Thames also staged a mutiny, known as the Nore or Sheerness mutiny. They blockaded the Thames and prevented ship traffic from reaching or leaving London. The Sheerness sailors conducted their mutiny along democratic lines, electing delegates from each of their ships to form a council. They chose seaman Richard Parker to be their mediator with the Admiralty.

The Austen family would have read, but not necessarily trusted, the pro-government accounts of the mutinies published in the Hampshire Gazette and the Chronicle. An anonymous letter to the editor from “a naval officer” urged the senior officers to show parental kindness to the sailors who had previously demonstrated their “gallant conduct and obedience.” “[R]emember the only difference between you and them is education—They neither want for good sense, or Affection for their King and Country.” It is not impossible that Jane Austen’s lieutenant brother, Francis Austen, was the author of that letter. At the time of the mutiny, he was serving on the Seahorse, capturing French vessels for prize money, just as Captain Wentworth did in Persuasion. The anonymous letter mirrors the advice given to Francis by his own father when he embarked on his naval career, urging him to show "kindness" to his "inferiors," because "they have a claim" on his regard and consideration.

Just like her brother, Austen could not openly criticize the Admiralty for the privations, hardships and injustices suffered by the common sailors. She had to respond obliquely. Hence, her disguised portrait of Richard Parker. It can be no coincidence that the leader of the mutineers and Austen’s errant midshipman were both named “Richard,” and both were subject to "removals," as Austen puts it, to many different ships. While Austen only mentions the Laconia for Dick Musgrove, Parker served on the Mediator, Ganges, Bulldog, Blenheim, Assurance, Hebe, Royal William, and finally the Sandwich--a rotting, verminous, seriously overcrowded craft.

Parker's execution Why does Austen mention letters in particular?

Parker's execution Why does Austen mention letters in particular?In other respects, however, Austen inverts her portrait of Richard Parker, the better to cloak her attack on the Admiralty. The narrator makes a pointed reference to Dick Musgrove’s letters home to his family, describing all but two as “mere applications for money,” a satiric allusion to the fact that Richard Parker authored the written demands of the mutineers. However, the real Richard was not a semi-literate buffoon, but a man better educated than most of his shipmates. He would not have written a phrase like “two perticular about the school-master,” as Dick Musgrove did. In fact, Parker was probably chosen to be the spokesman because of his superior literacy and experience. Austen is satirically referencing the disdain and contempt in which Parker and his fellow mutineers were held by the Admiralty.

Further, Austen surely took the name of William Elliot’s friend “Colonel Wallis,” from Captain James Wallis, a well-liked captain whose departure (by promotion) from the Tisiphone, led its crew to join the mutiny at Sheerness.

The Sheerness mutineers were suspected by the authorities of having revolutionary (Jacobin) sympathies. The authorities threatened everyone with capital punishment and the mutiny collapsed.

Unknown to the public when Persuasion was first published, but revealed with the later publication of Austen’s letters, is yet another connection between her fictional sailor and the real Richard Parker. Parker’s court-martial was presided over by Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley, whose nephew, General Sir Charles William Pasley, authored a book on the British empire which Austen read and described to her sister Cassandra. At this court-martial, Parker protested that he managed to “prevent a number of evil consequences” and restrained the most reckless impulses of the mutineers. Nevertheless, he was found guilty. of High Treason. Even Parker’s enemies acknowledged that he conducted himself in a "firm and manly" fashion during the trial and met his sentence of death “with a degree of fortitude and undismayed composure, which excited the astonishment and admiration of every one present.”

"the fine wind which had been blowing on her complexion" A lion-hearted Richard

"the fine wind which had been blowing on her complexion" A lion-hearted Richard Persuasion's narrator remarks that Dick Musgrove was never called “Richard” because he was no “better than a thick-headed, unfeeling, unprofitable Dick Musgrove, who had never done anything to entitle himself to more than the abbreviation of his name, living or dead.” The flip side of Austen’s quip is that the name must be earned. In his courageous defiance of the class-ridden and corrupt government, Richard Parker earned the admiration of working-class Englishmen. Unlike Dick Musgrove, who was "scarcely at all regretted" in death, throngs came to pay respect to Parker's corpse after his wife had managed to wrest it from the authorities and briefly display it at a tavern near Tower Hill. His legend lived on in an 1830 play and an 1851 novel, and, of course, in Persuasion.

The narrator’s savage deprecation of Dick Musgrove in Persuasion makes sense when understood as a lacerating indictment of the way that the Admiralty blackened Richard Parker’s character during his court-martial and after his execution. Likewise, Mrs. Musgrove is revealed as a sort of female John Bull figure. Austen is not fat-shaming Mrs. Musgrove, she is using the idea of corpulence to symbolically represent the complacent members of the public who neither know nor care how the British Navy is regulated. Mrs. Musgrove and her husband were “little… in the habit of attending to such matters… unobservant and incurious… as to the names of men or ships” until the death of their son Dick forcibly draws their attention to the issue. Their tears for their "worthless" son ironically both reveal and conceal the injustices that outraged Austen.

With her subversive critique, Austen paid homage to the brave mutineers of 1797 who risked their lives to demand their rights. Readers of Persuasion know that the "fresh-feeling" sea breezes of Lyme are responsible for restoring Anne Elliot's faded beauty. The slang term amongst the mutineers for their uprising was "the Breeze," no doubt a reference to the winds of radical change. Thus Austen pays tribute to the hope of radical reform in the reviving breeze that brings Anne Elliot back to life. More on the Nore Mutiny:

Doorne, Christopher, et al. “A Floating Republic? Conspiracy Theory and the Nore Mutiny of 1797.” The Naval Mutinies Of 1797, Boydell and Brewer Limited, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781782040057....

Manwaring, G.E., and Dobree, Bonamy. The Floating Republic: An Account of the Mutinies at Spithead and the Nore in 1797. Pen & Sword Books, 2004. "“The fact that the mutiny at the Nore was not settled, as that at Spithead had been, but crushed and savagely punished, was almost certainly the reason why mutinies continued to break out sporadically for two or three years over the whole Fleet.”

Fun Facts: One of the ships that mutinied at Sheerness was commanded by the infamous Captain Bligh of Bounty fame. So two different crews mutinied against him.

Since the Sheerness mutiny, the British Navy no longer rings five bells for the fifth dogwatch (6:30 pm), as that was the signal for the mutiny to start.

Previous post: The Barbadoes Girl

More guest editorials here .... and here .... and here... and here

Published on April 01, 2025 00:00

March 22, 2025

CMP#212 Waltzing Matilda, the reformed heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#212 Waltzing Matilda: Moral Perils in The Barbadoes Girl (1816) by Barbara Hofland

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#212 Waltzing Matilda: Moral Perils in The Barbadoes Girl (1816) by Barbara Hofland

Matilda sees snow for the first time Disclaimer: When I quote opinions from this two hundred-year-old book, I am not endorsing them.

Matilda sees snow for the first time Disclaimer: When I quote opinions from this two hundred-year-old book, I am not endorsing them. In an early post on this blog, I referenced Matilda, or, the Barbadoes Girl (1816) by the prolific author Barbara Hofland as an example of a book which openly discussed enslavement, plantations, and the slave trade. I was countering the argument that Jane Austen had to pull her punches when discussing slavery. Hofland's pro-abolition opinions, stated openly by the "good" characters in the book, were not controversial at the time, even in a book written for children.

The abolitionist message of this book reflects the reality that evangelical Christians were the driving force behind the anti-slavery crusade in England. That said, the moral issue of slavery and the welfare of enslaved persons is subordinate to the personal reformation of the main character, a spoiled daughter of a planter who repents of her bad temper and selfish behavior after she is taken into a loving Christian household. In addition, the topic of slavery is left behind in favour of a different moral danger in the last chapters of the book.

Matilda, or, The Barbadoes Girl was reprinted for over fifty years, which is pretty good innings for an author. In most editions, the title is simply The Barbadoes Girl. I have not found any contemporary reviews. One American journal praised Mrs. Hofland’s “interesting little stories which are not less marked with tenderness than with morality” but the reviewer admitted he had not had time to read The Barbadoes Girl. Here is a synopsis...

London 1866 edition A spoiled little brat

London 1866 edition A spoiled little bratThe Harewoods, an “amiable and happy family” with two boys (Edmund and Charles) and one girl (Ellen) take in the "daughter of a deceased friend" from Barbadoes; i.e. she is the daughter of a plantation-owner. Little Matilda Hanson is an heiress, but her widowed mother must stay behind in the West Indies for a time to wrap up her husband's affairs. Meanwhile the Harewoods give Matilda and her maidservant a home in England.

Zebby the maid is presented in a manner typical of the era--she is as an affectionate, simple-minded, loyal, pidgin-speaking family retainer: “Me makee de bed, sweepy de stair, do all sort ting.” Matilda quickly proves to be spoiled, arrogant and indolent. A special word about that indolence. In this book, as in others, it is a given that “bodily indolence” is “natural to her as a West-Indian,” and her lack of physical vigor is put down to growing up in that hot climate. If we had ever met the "chilly and tender" MIss Lambe of Austen's unfinished novel Sanditon, would she too, have been naturally indolent?

At any rate, Matilda has been petted and spoiled by the house servants in her native Barbados. The Harewoods are dismayed by the way “she now conducted herself constantly toward the menials” in their household. The crisis comes when she flings a glass of beer in Zebby's face at the dinner table. Mrs. Harewood removes Zebby from Matilda’s control by hiring her as a housemaid.

In time, and thanks to the good influence of the Harewood children and their parents, Matilda begins to understand the error of her ways.

Discussion of emancipation and its consequences for planters

Discussion of emancipation and its consequences for planters Zebby also plays a part in Matilda's self-reform. The Harewoods charitably purchase a mangle (a device for squeezing water out of wet laundry) for a local woman to help her set up as a laundress. Zebby offers to help with the laundry. Zebby tells Matilda that the reason she is happy to help others is because they are kind and friendly to her, whereas Matilda is cruel and insulting. (This passage includes an eyebrow-raising assertion: “It is well known that the negroes are naturally extremely averse to all bodily labour, and that, although their faithfulness and affection are such as to render them capable of enduring extreme hardship and many painful privations, yet they are rarely voluntarily industrious.”)

This novel was published in 1816, after the slave-trade was abolished but some years before enslavement was abolished in Britain and her colonies in 1833. It’s clear, however, that the Harewoods confidently expect emancipation to occur and speak of it as something that the government will do. Mr. Harewood hopes “the blacks will… become diligent servants and happy householders, no longer the slaves of tyrants, but the servants of upright masters.” Edmund is concerned for the consequences to the planters: “People say this will come upon them as a retribution for past sins.” Unlike his brother Charles, who thinks “they all deserve to be ruined," Edmund regrets that people who inherited plantations, that is, who never chose the source of their wealth, should be penalized. Mr. Harewood thinks that the dissolution of slavery, even if conducted gradually, will lead to much dislocation and suffering. (As it happened, the British government paid compensation to slave holders for the loss of their property.).

Matilda vows she would rather become a governess to support her mother than see the institution of slavery continue. “I only want to see my dear mamma, and to comfort her, and to tell her that I would not be the mistress of bought slaves for all the world; for I now know that in the sight of God they are my equals, and if good, my superiors. I know that Jesus Christ died to save them as well as me.”

Mrs. Harewood comforts her by making a distinction which, I’ve learned, was significant to people at the time but which I think the vast majority today would dismiss as irrelevant, namely, the ethical difference between being a slave-trader and a slave-owner: “be it your comfort to know, that although your father was a proprietor of West India estates, yet his fortune was not accumulated by the infamous traffic to which we allude." Furthermore, she explains that he was not brutal to his slaves because "he had an estate in this country, which enabled him to support an expensive establishment, without recurring to those practices too common among planters in your country.” We learn that Matilda's mother has sold the family property and invested the proceeds.

The Harewoods and the narrator don't judge Matilda or her mother for the past, but the subject is soon thrown in her face. Slave-shaming?

The topic of slavery arises again when the Harewoods throw a ball for the young people of their acquaintance (the main characters here are in their early teens or younger) and three snobbish house guests decide to attack Matilda for coming from a slave-holding family. These teenagers are not presented as abolitionists, but as bullies maliciously exploiting an embarrassing subject so they can assert their own class superiority. They use startingly brutal language which underlines my contention that authors were not forced to use oblique language around slavery. “Now, I don’t doubt, Miss Hanson being so wise in other matters, can tell you exactly how much pain is necessary to kill a slave, how many stripes a child can endure, and how long hunger, beating and torturing, may be applied without producing death, and prove that in case they do destroy a few blackies, that don’t signify, if they can afford to buy more.”

Little Ellen protests, calling on her father to correct the bullies. She expects him to assert that “people in the West Indies do not torture their poor slaves for nothing but their own wicked pleasure.”

Harewood demurs: “as I have never been in the West Indies, I have no right to contradict such evidence as has been brought forward by respectable witnesses.” And certainly, he goes on, Englishmen in England are capable of cruelty when unchecked by reason and religion. He adds--in a long convoluted sentence that I doubt many adolescents could understand today--that the children flinging ugly words at Matilda would be just as inclined to inflict sadistic physical pain on her if they could, and therefore they have more in common with evil slave-drivers than with the "self-condemned, but self-correcting" Matilda.

Matilda's remorse, or is she just trying to avoid looking at those sideburns? Wait 'til they hear about twerking

Matilda's remorse, or is she just trying to avoid looking at those sideburns? Wait 'til they hear about twerkingNow we come to the final chapters of the book in which the subject of slavery is superseded by a new danger to the morals of society--waltzing! The young people are all grown up. Edmund has become a lawyer, and Charles hopes to join the diplomatic service. Matilda lives with her mother and she and Ellen are young beauties going into society. Matilda’s new moral struggle has to do with overcoming her personal vanity and abstaining from waltzing in public. She argues with her mother: “Indeed, mamma, I see nothing against it—I think it very graceful.” Her mother responds that she regards girls who waltz “with disgust and sorrow: and though I sincerely despise all affectation of more exalted purity than others, I yet will never hesitate to give my voice against a folly so unworthy of my sex, and which can only be tolerated by women whose vanity has destroyed that delicacy which is our best recommendation.”

When Ellen’s mother and Matilda’s mother allow their daughters to go to a ball chaperoned by a society lady, Matilda is tempted to join in a waltz with a young baronet with a risqué reputation.

“As the arm of Sir Theodore encircled her waist, deep confusion overwhelmed her, she blushed to a degree that was absolutely painful” and she exits the dance floor in shame. To her great chagrin, her behaviour was witnessed by Charles and Edmund and their friend Mr. Belmont, all down from university. Matilda manages to exchange a few quick words with Charles to convince him as to her regret and remorse. The following morning, he speaks up on her behalf when the Harewood family gravely discusses her misdemeanor.

Taking your vows seriously

Taking your vows seriouslyThere follows some titillation and misunderstanding on all sides as to whether it is Charles or Edmund that Matilda loves. Yes, this kind of misunderstanding is a trite cliche, but I rather enjoyed it.

We discover that Matilda loves Edmund and he loves her. Edmund was naturally diffident about declaring himself since he would hardly be able to marry for years on his income as a barrister, while Matilda is an heiress. Fortunately, Matilda’s mother approves heartily of the match, and so does Zebby: “All right—all happy—Missy have goodee friend, goodee husband—him alway mild and kind; Missy very goodee too—some time little warm, but never, never when she lookee at massa; him melt her heart, guide her steps, both go hand in hand to heaven.”

Young Ellen's hand is sought by their university chum Mr. Belmont. Here we see another example of the curtailed and understated wedding proposal and marriage scene: “Ellen gave one glance towards her mother—it answered all her wishes; she turned, deeply blushing, to Mr. Belmont, and timidly, yet with an air of perfect confidence, tendered him her hand; she would have spoken, but the variety of emotion so suddenly called forth… overpowered her, and he received thus a silent, but a full consent to his wishes.”

Our heroines are well aware that their marriage vows mean placing themselves under the authority of their husbands: “the lovers of Matilda and Ellen were each urgent for their respective marriages; but the awfulness of that sacred engagement into which they were about to enter, the consciousness the entertained of the goodness of their parents, and the happiness of the state they were quitting, held the young ladies for some time in a state of apparent suspense and almost incertitude... and when at length the solemn ceremony took place, it was to each party rather a day of serious thoughtfulness and fearful anxiety, than one of exultation and exhibition.”

Resigned to subordinating herself to her virtuous husband, "Matilda looked to Edmund as the guardian of her conduct." Both of the happy couples are benevolent, "happy in themselves, and a blessing to the circle around them."

'National Galleries of Scotland' About the author:

'National Galleries of Scotland' About the author:Barbara Hofland (1770--1844) stated she wrote Matilda’s story “to instruct rather than to amuse.” She was a prolific and successful authoress who used fiction to spread her evangelical Christian message. She was born into the merchant class and her first marriage lasted only two years, ending with her husband’s death. Some of her books feature widows who have to carry on raising and providing for their children when they are left destitute, and most are set amongst the middle-classes. She married for a second time to a landscape artist but she was the chief breadwinner. She also wrote poetry, textbooks, and newspaper columns. Like Austen, in her lifetime she advertised her books anonymously but by listing her best-selling titles such as "The Clergyman's Widow," etc.

Published on March 22, 2025 13:36

March 11, 2025

CMP# 211 Book Review: Jane Austen's Bookshelf

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. This post is a review of the newly-published Jane Austen's Bookshelf which discusses some of the better-known female writers that Austen read. My blog focusses on more obscure authors, some of whom enjoyed great success in their day and were read until well into the 19th century, such as Elizabeth Helme and Elizabeth Meeke. For more, see the "authoresses" link at the upper right hand side of the page. CMP#211 Eight pioneering women writers who were on Jane Austen's bookshelf

So where are you in your journey from Austen fan to Austen superfan? Have you worked out the Austen family tree? Do you smile politely when someone quotes Austen's "little bit of ivory" at you, because you've already heard or read it a hundred times? Have you read any or all of the novels mentioned in Northanger Abbey? Did you know that "Lover's Vows," the play performed by the young people in Mansfield Park, was a real play?

So where are you in your journey from Austen fan to Austen superfan? Have you worked out the Austen family tree? Do you smile politely when someone quotes Austen's "little bit of ivory" at you, because you've already heard or read it a hundred times? Have you read any or all of the novels mentioned in Northanger Abbey? Did you know that "Lover's Vows," the play performed by the young people in Mansfield Park, was a real play?In my opinion, Jane Austen's Bookshelf by Rebecca Romney is geared toward people who are not far along in their Austen journey, but are ready and eager to learn more. On the other hand, well-informed Janeites might find that it covers familiar territory, while others might be bemused by the proposition that Maria Edgeworth and Frances Burney are forgotten writers whose connection to Austen was waiting to be rediscovered.

I don't mean that as a criticism of a well-written and deeply researched book, which this is. For someone wanting to learn more about Austen and her literary world, Jane Austen's Bookshelf is packed with revelations for the reader (I'll get back to that later) and a valuable guidebook to the literature of her time. A busy tapestry of a book

Romney was already an expert on books as physical objects, but in Jane Austen's Bookshelf she shares what she has learned about the women writers who pioneered the novels which Austen read and admired. Not every writer can expound on academic topics for a general reader--I think Romney manages this very well. Jane Austen's Bookshelf is an ambitious weaving together of many different threads:A mini-biography of Jane Austen and a discussion of her novels,Mini-biographies of eight women writers of Austen's era, some of which rival the plot of any 18th-century novel,Discussions of how these other writers might have influenced and inspired Austen, A reiteration of the feminist explanation (cf Dale Spender 1986) for why and how Austen's reputation rose while the others sank in critical esteem and recognition (hint: it was the chauvinism),Contextual information about the late Georgian/Regency era in terms of marriage, class, and money, and the debate over novel-reading,The world of rare book sales and collection, andThe author's evolution from a conservative and religious background to a feminist awakening. Romney weaves these threads with skill. She moves adroitly from one topic to another as she chronicles her learning journey.

From tunnel vision to broader context

From tunnel vision to broader contextThis journey is exemplified by Romney's discoveries around the phrase "Pride and Prejudice." At first, she--like me--assumed it was a clever coinage of Austen's own. Then she learned that "the phrase 'pride and prejudice' came from Burney’s second novel, Cecilia (1782)."

Now, some fans might wobble at this stage. It can be a little painful to give up the idea that Austen was a completely unique genius who owned nothing to anybody. I felt this myself when I came across the phrase "pride and prejudice" in The Two Cousins (1794). But if you are intrigued, like Romney, you dive in. She found the phrase “pride and prejudice” in Charlotte Smith's The Old Manor House (1793) as well. Then she learned Hester Thrale used the phrase in her diary. "Across editions, across generations, I followed the evidence. I might not ever know the true answer to the source of Austen’s phrase, but the investigation itself thrilled me."