Lona Manning's Blog, page 7

March 20, 2024

CMP#178 Lord Mortimer the gullible hero

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#178 The Children of the Abbey (1796) by Regina Maria Roche

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#178 The Children of the Abbey (1796) by Regina Maria Roche

Alistair Petrie and Samantha Morton as Harriet Smith and Robert Martin in the 1996 Emma In the novel Emma, the subject of novels comes up when Emma Woodhouse asks Harriet Smith about Robert Martin's reading habits. Emma thinks the young farmer is not good enough for her friend Harriet. She asks Harriet, “Mr. Martin, I suppose, is not a man of information beyond the line of his own business? He does not read?" Note that Emma phrases the question in the negative. She's expecting to have her prejudices confirmed.

Alistair Petrie and Samantha Morton as Harriet Smith and Robert Martin in the 1996 Emma In the novel Emma, the subject of novels comes up when Emma Woodhouse asks Harriet Smith about Robert Martin's reading habits. Emma thinks the young farmer is not good enough for her friend Harriet. She asks Harriet, “Mr. Martin, I suppose, is not a man of information beyond the line of his own business? He does not read?" Note that Emma phrases the question in the negative. She's expecting to have her prejudices confirmed.There's a bit of subtle humour too, because surely Emma is asking about serious reading--politics and philosophy and history--but Harriet thinks only of novels and the Elegant Extracts (a sort of Readers Digest Condensed Books of the day). She mentions two potboilers: "He never read The Romance of the Forest, nor The Children of the Abbey. He had never heard of such books before I mentioned them, but he is determined to get them now as soon as ever he can.”

We never learn if Robert Martin ever get a copy of Regina Maria Roche’s lengthy gothic romance novel, The Children of the Abbey, but it was a best-seller. A synopsis published one hundred years after its publication, describes it thus: "The motherless Amanda is the heroine; and she encounters all the vicissitudes befitting the heroine of the three-volume novel. These include the necessity of living under an assumed name, of becoming the innocent victim of slander, of losing a will [that is, the will hidden from her by her evil stepmother], refusing the hands of dukes and earls, and finally, with her brother, overcoming her enemies, and living happy in the highest society forever after. The six hundred pages, with the high-flown gallantry, the emotional excesses, and the reasonless catastrophes of the eighteenth-century novel, fainting heroines, lovelorn heroes, oppressed innocence and abortive schemes of black-hearted villainy, form a fitting accompaniment to the powdered hair, muslin gowns, stage-coaches, postilions, and other picturesque accessories.”

It’s a long book with a lot of twists and turns, so I'll stick to the highlights and some recurring themes and tropes. The villains "are completely depraved and infamous, hardly a resemblance of humanity left in them," to use Jane Austen's words, and the heroine sheds a lot of tears along the way...

Amanda mourns her mother Our story begins....

Amanda mourns her mother Our story begins....Regina Maria Roche’s best-seller starts with a teaser chapter—we meet Amanda Fitzalan (she’s in tears, of course) as she arrives in Wales to live in the humble cottage of some retired family servants. All we know is that she is worried about her father and she is in hiding.

After the teaser chapter, we fill in with some backstory. Amanda’s father Mr. Fitzalan is the ‘’descendent of an ancient Irish family.’’ When he was a young army officer, he eloped with the oldest daughter of the Earl of Dunreath. The lovely Malvina had been, even hated, by her stepmother, who had managed to turn her father against her, in favor of her younger stepsister, Lady Augusta. Malvina had every reason to run away, but in these novels, good fortune seldom pursues girls who elope in defiance of parental authority. Malvina and Fitzalan lived in poverty and their attempts to reconcile with her father all failed. Malvina gave her husband a son (Oscar) and a daughter (our main heroine Amanda), before expiring. The travails of Amanda

Back to Amanda, now grown, living in seclusion in Wales under an assumed name. Wales, like Scotland, is a ‘’back of beyond’’ location in eighteenth-century novels, filled with quaint, rustic folk who speak in dialect.

Amanda is poor but genteel, which means there is no expectation that she would help out with the milking or the sweeping. But what to do with herself? You can’t just ramble around the forest glen wearing a plain but becoming muslin gown, sketching the sublime scenes of Nature and occasionally weeping in ‘’the calm solitude of the evening’’ day after day. Luckily, Amanda’s former servants live close to a nobleman’s house, which is empty most of the year. Amanda is given permission by the housekeeper to use the library and play the pianoforte.

The young and handsome scion of the family, Lord Mortimer, shows up unexpectedly and doesn’t waste time falling in love with Amanda, despite the mystery of her background. So does the local vicar, Mr. Howell (how can he help himself), but it’s Lord Mortimer that Amanda loves in return, though she is of course suitably diffident about it. The travails of Oscar.... and spoilers....

Meanwhile, Amanda’s brother Oscar, a fine young officer, is in Ireland, and he falls in love with Adela Honeywood, the sprightly daughter of a general. Now enter, stage left, (hissssssss) the villain, Colonel Belgrave.

This lecherous goat is the reason Amanda is hiding in Wales, and he sets out to destroy Oscar’s life too, by thwarting his romance with Adela through lies and chicanery and marrying her himself. By the way, the "evil-lecher-uses-his-money-and-power-to-threaten-the-father’s-finances,-the-son’s-army-career,-and-the-daughter’s-virtue” was used by Susannah Rowson for the parents of her heroine in Charlotte Temple, published five years earlier.

More travails for Amanda

A remark by the mother of Amanda’s host family, that Amanda "is not the first poty [body] who has met with a bad man," causes Lord Mortimer to instantly assume that Amanda is a Fallen Woman who is hiding out in Wales from shame, when in fact she’s fled to Wales to avoid the bad man. Boom, he drops her, (or as the kids say today, he ghosts her), for the first but not the last time in this novel.

This is the suspenseful point which keeps us turning the pages: OMG, can Lord Mortimer be persuaded that Amanda is faithful and chaste? There is more villainy, both from Colonel Belgrave and from Amanda’s malicious Scottish relatives, mostly in the form of compromising Amanda’s reputation. Occasionally, Mortimer investigates the accusations made against her, but events conspire to raise his doubts again. And again.

They finally reconcile and are engaged to be married. Then his own father, Lord Cherbury, throws a spanner in the works when he entreats Amanda to break off the match. He, Lord Cherbury needs his son to marry a wealthy heiress to pay off his, Lord Cherbury’s, gaming debts, so could Amanda please just disappear on the eve of her wedding without explaining why? With many tears, Amanda consents (for Lord Cherbury swears he will kill himself if she doesn’t) even though once again it blasts her ‘fair and spotless fame.’ Cheered by the unexpected light, [Amanda] advanced into the room… she found herself not by a picture, but by the real form of a woman, with a death-like countenance!... “Protect me, Heaven!” she exclaimed, and at the moment felt an icy hand upon hers! Her senses instantly receded, and she sunk to the floor. When she recovered from her insensibility … the apparition, with a rapidity equal to her own, glided before her, and with a hollow voice, as she waved an emaciated hand, exclaimed, “Forbear to go… lose your superstitious fears, and in me behold not an airy inhabitant of the other world, but a sinful, sorrowing, and repentant woman… In me,” she continued, “you behold the guilty but contrite widow of the Earl of Dunreath.”

Scooby-Doo plot twists, image generated by Bing AI Amanda is constrained by events to move from place to place, hiding out in a convent, in a remote schoolhouse in the Hebrides, and finally, through some twists of fate, back to the old family castle, working as a governess, her identity a secret.

Scooby-Doo plot twists, image generated by Bing AI Amanda is constrained by events to move from place to place, hiding out in a convent, in a remote schoolhouse in the Hebrides, and finally, through some twists of fate, back to the old family castle, working as a governess, her identity a secret. Happy, noble and rich

There are other details I haven’t mentioned, such as the love-rival Sir Charles Bingley, a nice young man, and we should take note of the gothic aspects of Amanda’s return to the ancestral seat of the Dunreaths. While exploring the ghostly passages of half-ruined Dunreath Abbey on her own (as one does), Amanda comes across a specter! No, it’s not a ghost, it’s a female prisoner—none other than Lady Dunreath, the stepmother who so long ago made life miserable for Amanda’s mother Malvina. Lady Dunreath was locked up by her son-in-law and her evil, ungrateful daughter, to keep her from remarrying and from spilling the beans about the forged last will and testament which deprived Oscar and Amanda of their just inheritance.

Colonel Belgrave, the industriously busy seducer (he goes after several girls in this book), dies of drinking, fever and remorse in France, and Adela is free to marry Oscar.

This brings us another reminder that the theological conventions of this era bring a Reckoning at the Judgement Seat, as well as demonstrations of the highest standards of Christian forgiveness. ‘’But oh,’’ exclaims the father of one of the girls Belgrave seduced and abandoned. ‘’But oh, may he find mercy from that God! May he pardon him, as in this solemn moment I have done! My enmity lives not beyond the grave.’’ However lurid with their fixation on seduction and even assault, these novels conduce to teaching a moral lesson.

Plot device: portraits

Plot device: portraitsPortraits and miniatures play an important role in this story. First, Fitzalan is entranced with Malvina’s portrait, and through it, he betrays his love for Malvina. The evil Belgrave uses a miniature of Amanda to persuade Adela that Oscar has another sweetheart, (when of course she's his sister), and Amanda is mooning over a sketch she has drawn of Lord Mortimer, realizing that “delicacy” demands she destroy it because he’s about to marry Lady Euphrasia: “'Oh! how unnecessary,' she cried... 'to sketch features which are indelibly engraven on my heart.' As she spoke, a deep and long-drawn sigh reached her ear... the feelings of her heart discovered, she started with precipitation from her seat, and looked round her with a kind of wild confusion. But, gracious Heavens! who can describe the emotions of her soul when the original of the picture so fondly sketched, so hastily obliterated, met her eye.” Betrayed by her feelings, Amanda confesses her enduring love for Lord Mortimer, while he reveals he is not going to marry Lady Euphrasia. About the authoress:

Regina Maria Roche (1764–1845) is ranked in the second tier of Gothic novelists, after the queen, Ann Radcliffe. Roche's 1796 novel Clermont was one of the "horrid" novels recommended to Catherine Morland by Isabella Thorpe in Northanger Abbey. Many of her novels were set in Ireland, the home of her birth. The Children of the Abbey was her biggest seller, and I think any author could be proud of a book which stayed in print for more than a hundred years, and was frequently imitated and even plagiarized.

Gothic novels continued to find a readership even as they fell in critical esteem. William Brighty Rands wrote in 1865 that "[b]ooks like The Children of the Abbey, by Regina Maria Roche, have been exposed in decent [book]shop--windows within my own recollection." In 1891, an American critic wrote: "And apparently Children of the Abbey still finds a considerable sale in this country, though it is almost wholly forgotten in England."

It seems Americans had a real predilection for melodrama, given the phenomenal popularity of East Lynne (1861) by Mrs. Henry Wood and the enduring popularity of a tale first published in 1791, Charlotte Temple.

Gothic novels favored remote settings such as Wales, Scotland and farther afield in Europe. Jane Austen did not stray beyond the home counties in the settings for her novels. As she advised her niece, who was working on a novel: ‘’Let the Portmans go to Ireland; but as you know nothing of the manners there, you had better not go with them.’’ Austen let the Dixons and the Campbells go to Ireland in Emma, but her readers did not go with them.

Previous post: Eva the runaway heroine

Published on March 20, 2024 00:00

March 14, 2024

CMP#177 Eva, the runaway heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 177 Eva, the heroine who runs out of her own novel and disappears for quite a while

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 177 Eva, the heroine who runs out of her own novel and disappears for quite a while

Imagine that you have written your first novel and it’s been accepted by Minerva Press, which is, let’s be honest, not a prestigious publisher but still, your novel will be published! And then it does it get published and there’s…. the wrong author’s name on the title page? I don’t know how this happened, but in later years, an authoress named Amelia Beauclerc claimed authorship of this novel, not Emma De Lisle. And why is the book called Eva of Cambria? The character Eva is absent from most of the book and she lives in France and Spain, not Wales.

Imagine that you have written your first novel and it’s been accepted by Minerva Press, which is, let’s be honest, not a prestigious publisher but still, your novel will be published! And then it does it get published and there’s…. the wrong author’s name on the title page? I don’t know how this happened, but in later years, an authoress named Amelia Beauclerc claimed authorship of this novel, not Emma De Lisle. And why is the book called Eva of Cambria? The character Eva is absent from most of the book and she lives in France and Spain, not Wales. We don't meet Eva and there is no mention of her until 185 pages into the story. We start with the history of another family; an older man named Percy Eddington, who never married because he was disfigured in a carriage accident. He lives with his spinster sister Helena, and --crash! What was that?

That was another carriage accident. This one brings a distressed widow and a lovely young lady to their door. Laura becomes Percy’s bride, in a May/September pairing. The Eddingtons are happy, devout, and kind to their tenants; good-hearted Welsh people who like to drink to excess whenever Mrs. Eddington presents her husband with a child. They have three children: Julius, Horatio, and Helen. Synopsis and spoilers follow... More Meet Cutes

Julius and Horatio go to Eton, where they rescue a girl named Arabella. First, Julius rescues her from a rabid dog, then they rescue her from a panderer who is trying to force her into concubinage. Then they head home with a family servant when they rescue our titular heroine, Eva, who is stuck at the bottom of an overturned carriage with a fat French governess standing on top of her. Eva is half-French, very young and very frightened. After subduing the horses and rendering first aid to everyone, there is nothing more two teenage boys can do, so they leave Eva and her governess with a doctor and his wife.

Because of the machinations of an evil (now deceased) step-mother, Eva knows nothing of her parentage. She despises her vulgar and ignorant governess, and fears that she is not being conveyed to the arms of a fond parent, but being taken by Madame La Botte to be given to a nobleman as his concubine. She flees in the dead of night and most fortunately is rescued and taken up by a passing couple, the Byrams, who also rescue her from an over-amorous soldier who enters her bedroom at the inn. The Byrams grow so fond of her they informally adopt her. Mr. Byram is a merchant and the family go overseas and sail out of the book for many chapters.

Julius leaves school, joins the army and goes to America (the book is set at the outset of the American Revolution) where he finds that a corporal's wife is none other than the happily married and respectable Arabella, the girl he rescued at Eton.

Back in England, the rest of the family goes on a tour around the country. Mr. Eddington by chance learns that they are near the home of an old acquaintance of his, Lord Eggerfield, who is twice widowed and living like a hermit while his estate sinks into Gothic ruin. No, that’s not a ghost, it’s Lord Eggerfield, traipsing around the halls at night. And those low moans are not the sound of an imprisoned woman--oh! wait, they are the sounds of an imprisoned woman! it’s the French governess, Madame La Botte, whom Lord Eggerfield blames for the disappearance of his daughter Eva. Mr. Eddington politely points out that it’s illegal to imprison people in England like this. Madame La Botte, who genuinely does not know what happened to Eva, is allowed to return to France.

Meanwhile Horatio rescues a reduced gentlewoman and her daughter Clara from a raging bull, and he falls like a ton of bricks for Clara. His parents aren’t the type to object to a girl just because she has no money, but Horatio and Clara are both so young, that Mr. Eddington feels it would be best if Horatio went off on a tour of Scotland to test his constancy.

Cartoon of 14-year-old Lady Georgiana Gordon (detail) A Real P____n?

Cartoon of 14-year-old Lady Georgiana Gordon (detail) A Real P____n? At this point the author introduces a femme fatale, and because she is called Lady G_____a G____n, I concluded this must be a real person. Since the book was not reviewed when it came out, I have no confirmation, but I think it's Lady Georgiana Gordon, whose mother was a famous Scottish hostess and socialite, even though the dates don't match up. I haven’t seen a real person used in a fictional love triangle this way before. Horatio and Lady G____a meet, not beside an overturned carriage, but at a ball, where Lady G____a does her seductive “tambourine dance.”

Lady G_____a's mother the Duchess invites Horatio to her many entertainments. They speak of a pleasure cruise on the lake, and I was expecting Horatio to have to fish Lady G____a out of the water, but that never happens. Even without being rescued by him, Lady G_____a develops a crush on Horatio, who does not have the finesse to drop his prior commitment to Clara into the conversation. While disapproving of her antics (he thinks that he will never allow his daughters to do likewise), he is still powerfully attracted to her. One night the other men get Horatio roaring drunk, and he ends up kissing Lady G_____a in her boudoir. Horrified at what he has done, he flees back to his parents' house and is scrambling into the window when he is mistaken for a burglar and shot by the gamekeeper. Luckily, the wound is not fatal. When Clara is reunited with Horatio, she is so happy that she retreats, like a good Austen heroine: “a couple of hours spent alone will bring me to a proper recollection of myself; I am now all tumult, confused, and even doubtful of the possibility of such complete felicity.”

Julius and Horatio's younger sister Helen is wooed and won by a Colonel Horace Walpole, visiting on a quick trip from the American campaign.

Name inspiration? Horatio "Horace" Walpole, (1717–1797) father of the Gothic novel Julius and some Coincidences

Name inspiration? Horatio "Horace" Walpole, (1717–1797) father of the Gothic novel Julius and some CoincidencesJulius gets badly injured in the war in America, and the ship on which he is invalided home with another officer is captured by the French. Julius and his friend Manners are paroled (meaning they give their word of honour as officers and gentlemen that they won’t escape) and given into the custody of an English merchant living in Cadiz, none other than Mr. Byram. Mr. and Mrs. Byram and Eva and their niece have been living abroad all these years. Col Manners was the drunken soldier who terrified Eva back in England in the inn, but neither the Byrams nor Eva recognize him. And he has reformed his character, thanks to Julius. Manners falls for the Byram’s niece Harriet, and Julius is entranced with Eva whom he recognizes as the girl he rescued from the carriage accident years ago (though he says nothing). He suspects she must be Lord Eddington’s missing daughter, whom he’s learned about in family letters. So what is she doing here in Cadiz? What has she been up to since she ran away? Is she a fallen woman?

After everyone is stranded in the woods because of a carriage accident, and Eva clings to him in fright, Julius can hardly restrain his feelings: “were it not for the unaccountable mystery about her, he felt that he could love her beyond measure…. Her touch had magic in it: but she might have clasped those arms about some other! Horror and disgust followed the thought.”

Finally, Julius openly questions Eva as to what she's been up to since she disappeared, and while she is briefly astonished and offended, they manage to sort things out and he proposes. But wait! Eva is French and therefore a Catholic. No worries, Mrs. Byram has converted her. Eva “read her renunciation of Popish errors." Eva learns she is Lord Eggerfield's daughter and an heiress and she ran away in error, but really, she was better off growing up with the Byrams, because her father is weird.

Julius and his friend are exchanged for French officers and they go home, bringing their affianced sweethearts with them (and Mrs. Byram as chaperone, of course). The last few chapters see them--and everyone else--married, even Madame La Botte.

Features of interest:

Features of interest:The dramatic parts of the story are told in a fairly laid-back style, and are leavened by comic subplots. Twice, servants impersonating their mistresses elope with fortune-hunting men, thus thwarting the designs of the fortune-hunter.

No mention of slavery in this novel, and the only mention of the West Indies is as a place that soldiers wish to avoid being sent to (the climate was deadly to Englishmen). Slavery and chains are used in the conventional way of describing passion and love, as in “his lovely French enslaver.”

Lord Eggerfield mentions that his missing daughter has a birthmark, but I think the author inserted this detail into the story and never made use of it. Since Eva remembered Madame La Botte, her identity was never in question.

The book is written in 1811, long after the Americans won the Revolutionary War, but we are given the confident point of view of Julius, that the rabble will soon be suppressed. “Alas! My son,” his father thinks. “you write like a brave soldier, but not as a profound politician.”

The book is part travelogue, including a description of quarterly assizes at Newcastle. "They reached Newcastle… the Judges entered the second day after their arrival, and all was bustle, hurry, and confusion—bustle to those who take an early seat in the court, and are fond of trials—hurry to the same people who have to dine, dress, and prepare for a ball—confusion to the dismayed culprits, who stand in suspension between life and death, before clamorous counsellors and jurymen, and a gazing multitude. There is certainly something approaching to the savage, in the gaiety of the world at these awful periods; the Indian war-dance, in the sacrifice of their prisoners, bears some analogy to such meetings.”

In contrast to the many comic portraits of merchants in novels as being vulgar and pushy, Julius gives a spirited defense of them: “No character can be more respectable than that of merchant. Are they not the support of the first nation in the world? Do they not, with a true English spirit, subscribe to reward the relicts [widows] of the warrior, who has spent his last vital blood in the service of his country?”

The real Lady Georgiana Gordon married an English nobleman. She and her mother were quite colourful characters. When Eva of Cambria came out, Lady Georgiana was married and the mother of five children. But the book was set thirty years earlier, in fact when Lady Georgiana was a glint in her father's eye.

Bing AI image conception of Amelia Beauclerc About the Author

Bing AI image conception of Amelia Beauclerc About the AuthorAmelia Beauclerc has created a large cast of characters, from nobility to servants. The heroines are all of peerless virtue but other female characters have flaws and foibles. She's not so talented with dialogue. The main characters all sound the same.

We also have a comic reference to how Madame La Botte's husband beats her "soundly," and a minor character, a woman who is psychologically disciplined into being a proper wife. Her husband was "determined to make a total reform in her Ladyship; and the preliminary article was to be, that he should be master. He was too much of a gentleman to think of using his wife ill; but, as a gentleman, he determined she should respect him, and to be firm against arts, hysterics, or blandishments.”

Despite the title, the protagonists in this novel are the men of the Eddington family, the father and his sons Julius and Horatio. The author is interested in war, travel and horses. We have scenes set at Eton, in male drinking parties, and on board ship. One could hypothesize that "Amelia Beauclerc" was a dude.

The Orlando database of Women's Writing says that Beauclerc's novels were of "oddly varying quality," Possibly, "Amelia Beauclerc" was an all-purpose pseudonym used by the publisher for novels from various aspiring writers. The other pseudonym, Emma De Lisle, was used by Emma Parker, of Wales.

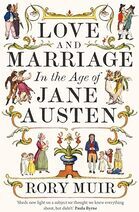

Did men and women only meet because of carriage accidents and runaway animals? Historian Rory Muir has a new book out about marriage and courtship in the time of Jane Austen.

Did men and women only meet because of carriage accidents and runaway animals? Historian Rory Muir has a new book out about marriage and courtship in the time of Jane Austen. This article from Human Progress points out that as human prosperity rises, people stop laughing at the idea of wife-beating:

Previous post: Elfrida, the martyr to rectitude

Published on March 14, 2024 00:00

March 6, 2024

CMP#176 Elfrida, the sanctimonious heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Lately, I've been reading and reviewing lots of old novels, for reasons I'll explain later. CMP#176 Elfrida, or, Paternal Ambition (1786), a novel in two volumes by a Lady

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Lately, I've been reading and reviewing lots of old novels, for reasons I'll explain later. CMP#176 Elfrida, or, Paternal Ambition (1786), a novel in two volumes by a Lady

Marrying for love. Bing AI Image Elfrida, or, Paternal Ambition might be a candidate for academic analysis as a female-written story which quietly subverts the patriarchy, because while the heroine displays conventional heroine behaviour, at times she and other female characters rebel against their restrictive gender roles. We also have an interesting and nuanced (for the times) portrayal of a villain. But otherwise, this story was a disappointment. It began in a sprightly, almost comic fashion, but devolved into a weird, boring melodrama with characters moving from here and there with nothing resolved. At the end of this post, I'll share my evidence for why I think Jane Austen read or at least knew about this novel.

Marrying for love. Bing AI Image Elfrida, or, Paternal Ambition might be a candidate for academic analysis as a female-written story which quietly subverts the patriarchy, because while the heroine displays conventional heroine behaviour, at times she and other female characters rebel against their restrictive gender roles. We also have an interesting and nuanced (for the times) portrayal of a villain. But otherwise, this story was a disappointment. It began in a sprightly, almost comic fashion, but devolved into a weird, boring melodrama with characters moving from here and there with nothing resolved. At the end of this post, I'll share my evidence for why I think Jane Austen read or at least knew about this novel.Elfrida starts with the courtship of Elfrida's parents. Her mother Ella Cluwyd is a lovely girl who falls for the dashing, handsome, but poor Lieutenant Overbury. The lieutenant is such a dish that Ella’s two spinster aunts, who want to thwart the match, get a crush on him, and one of them actually proposes to him. This section is comic, in its quaint way.

Ella is living with the aunts because her father is having a dalliance with a young woman. On the eve of her father’s wedding to this second wife, Lieutenant Overbury discovers a plot hatched by Mr. Cluwyd’s valet to rob the family and kidnap the lovely Ella for the fate worse than death. Overbury, with his sergeant and other soldiers, foil the plot. Even this heroism does not win Overbury the hand of Ella, especially not when a local baronet makes an offer for her...

Schoolyard love triangle. Bing AI image Teenage Love Triangle

Schoolyard love triangle. Bing AI image Teenage Love TriangleElla’s evil young stepmother is not pleased but incensed at the idea: “the chit she had chased from her house… to become a lady, take place of her wherever they met, and carry off the richest man in the county; forbid it malice, envy, revenge, every dire passion!” So, unexpectedly, stepmom becomes an advocate for Ella running away with the lieutenant and deceives them into thinking that Mr. Cluwyd will forgive her and support them financially. He doesn’t, so Mr. and Mrs. Overbury are condemned to a life of poverty on a lieutenant’s half-pay. They raise a lovely daughter, Elfrida. That's the prologue...

Lieutenant Overbury, who was adorable in the prologue, now becomes a tyrant. He is determined that his daughter will have a better life than he was able to give his family. When one of the spinster aunts offers to adopt Elfrida, educate her, and maker her an heiress, he hands his daughter over to her, despite the tearful objections of Ella.

Elfrida is raised on the Cluwyd estate, now re-named Arcadia, and the spinster aunt insists on a co-ed education with two neighbor boys—Frederic Ellison, who is a sadistic bully, and Edmund Wilmot, the vicar’s son, who is all perfection. “The same masters attended the three children.” They study “dancing, painting, music [and] geography” together. Of course Edmund (usually called Wilmot) and Elfrida fall in love as they grow up. But Elfrida sees the walls of propriety closing in on her: “I cannot, however, Wilmot, put on all my fetters at once; my looks, my words, my actions to be fettered, it is too much; and ah! how needless, to oblige me to conceal what passes in my poor heart.”

The aunt marries Frederic the bully's widowed father, uniting the estates, and they decree that Elfrida must marry Frederic (hereafter called Ellison). Counting on two inheritances, Lieutenant Overbury agrees to dispose of his daughter this way. Elfrida shows a bit of spirit and resists for a while. She openly declares her love to WIlmot: “I have ever loved you, and will ever love you… appearances, you know, must be attended to; I feel them, and I will not hesitate to call them so many fetters, and as such I am bound by them, but my mind is free, exteriors cannot affect that, and while I have consciousness it will be all your own.”

Lieutenant Overbury pressures Wilmot to go away so Elfrida can forget him. Elfrida submits and marries a man she has no respect for. “Wilmot has forsaken me, betrayed me, and I will not complain. My father and mother shall have their victim of filial obedience, they shall complete their cruel kindness, they shall see the insufficiency of wealth to support such a heart as mine; for Wilmot, the advocate of all that spoke peace to the jarring passions, Wilmot, that saved, now destroys.”

Once married, she behaves impeccably as a polite and submissive wife. Wilmot resolves to leave the country but first, he discovers that Ellison has seduced a nice girl, had two children with her, then abandoned her to die penniless. He rescues the children from being taken to the workhouse, and gives Hannah Jenkins, a local villager, funds to take care of them. Hannah used to be a servant to the Cluwyds and she is a typical stock servant--fiercely loyal, garrulous, and outspoken. The running comic gag with her is that it takes her forever to explain something.

Woman's work A miserable marriage

Woman's work A miserable marriageAnyway, Ellison, now the heir to his parent’s estate, promptly squanders and gambles away all of his patrimony. Elfrida, as a matter of duty and rectitude, hands over her inheritance from the spinster aunt, which he loses. Now they are penniless and she goes to live with her parents. The loyal (and garrulous) Hannah insists on living with them, though they can barely afford to feed her, let alone pay her. Lt. Overbury is of course distraught and remorseful over the utter failure of his hopes and ambitions for his daughter. She is saintly about it, and immediately sets about earning money. “Tambour, embroidery, netting, I am perfectly mistress of; and, O, insult me not so far as to call it degrading.”

Edmund Wilmot, meanwhile, is preparing to make a return trip to the East Indies, where he has already earned a little money. “the idea of [Elfrida] working for her living, as she calmly called it, made him frantic,” but she would be dishonoured if he gave her money. At a coffee shop in London, he overhears Ellison arguing with another man, Lord S___. Lord S____ offers to forgive Ellison’s gaming debts if he can have his way with Elfrida. That’s the one thing Ellison won’t stand for, so they duel. Wilmot intervenes, but Lord S____ is wounded. Ellison escapes to America.

Lord S____ does not give up his designs on the virtuous Elfrida and expends a lot of time and energy in his efforts to have her. He befriends the family under a false name. He hires a panderer to pose as a nice widow lady to befriend them while they live in Portsmouth, and invites Elfrida and Hannah to go on a day’s pleasure cruise. He waits through five weeks of unsuitable weather, and finally, they set sail.

Once on the open waters, Lord S____ makes his intentions clear, and Elfrida contemplates whether she needs “to throw herself into the sea,” but “condemn[s] herself with the utmost severity for despairing of the protection of Heaven.” Meanwhile, Hannah manages to speak to the pilot and boatswain of their little craft and promises them a rich reward from Mr. Wilmot when he returns from India, if they assist. Turns out they know Mr. Wilmot and think he's a great guy! The pilot hails a passing ship, and Elfrida is hauled aboard, between her fainting fits. “A glass of water,” she says, [feebly, no doubt] “would be a cordial for me.”

Happy Ever After? Bing ai image A Blessed Release

Happy Ever After? Bing ai image A Blessed ReleaseWhen introductions are performed, and Captain Venables learns that Elfrida is the wife of Frederic Ellison, he tells her that her husband was recently killed by “Indians” in America. The family writes to the British Army in America to double-check and the information is confirmed. Elfrida is now a widow, but out of delicacy, she will not stand for any talk of Mr. Wilmot. The Overburys warn Hannah not to “distress our Elfrida.” “A fiddlestick of distress,” [replies the garrulous Hannah] “I say distress, indeed, to be beloved by one of the most handsomest, and the most worthiest men in the world; for my part, I think your fine-lady whims are the next thing to lunacy…”

Well, of course Edmund and Elfrida get married, after much vacillation and delicacy on her side. He has enough money to purchase the Grange, the property that Ellison gambled away. They give a home to Ellison’s two illegitimate children. Good place to finish the novel?

Oddly, no.

Eight years go by. Mrs. Overbury’s father returns to Arcadia, he apologizes for allowing his second wife to alienate him from his daughter, he re-writes his will, and has a touching reunion with the Overburys and the Wilmots and their three lovely children, his great-grandchildren. Good place to finish the novel?

Not yet.

Hannah has bad news. Bing AI image Part three

Hannah has bad news. Bing AI image Part threeSix months later, Hannah receives a letter from -- oh no, it can’t be! Yes! Ellison is still alive! He wasn’t killed by Indians, he was abducted and he lived with them for seven years!

Several pages of hysterical lamentations follow, because this means Elfrida has been living in a state of adultery. She barely takes time to say farewell to Wilmot, the children, and her parents, before she flees to hide herself in London. Though she can never live with Edmund again, she wants to stay away from Ellison. Hannah grabs “a bottle of hartshorn” (yes, I think she’ll be needing it, Hannah) and offers to go with her, but she’s needed to take care of the children.

The kids, no doubt traumatized, are left with their grandparents the Overburys, while everybody else scatters. Wilmot takes his broken heart to America. Ellison also goes back to America, and then Elfrida leaves London and goes to her parents, and then Wilmot and Ellison run into each other in an officer’s mess in America, fight together, and--get this--become friends, Ellison is gravely wounded by an “Indian’s” poisoned arrow-head, and Wilmot nurses him and takes care of him as they head back again to Arcadia, where Ellison takes up residence. And then Wilmot goes to London.

The best I can say for this section of the novel is that the author does portray how a person who has done bad things always tries to justify himself. He is not a moustache-twirling villain; he regrets everything that’s happened, but he still thinks he’s been hard done by. He literally forgot that he had abandoned his two children by the girl he seduced. The children were raised by Hannah and the Overburys. Instead of showing gratitude, he is bitter at Hannah, whom he blames for poisoning his children’s minds against him.

Ellison's daughter weeps when she is told it is her filial duty to attend his sick bed. “If my behavior is sinful, he must answer for it, not me, for he has frighted all tenderness for him from my heart… [she tells Hannah], if I have no great love for him; for, if he is nothing to me, pray what am I honestly to him?” And after all, Ellison's wife, Elfrida, that is, won't come near his deathbed.

Wilmot as usual is kind and forgiving “I, nevertheless, pity him—forgive him, and charge the contraction of his vices, and the obscurity of his virtues, upon a wrong education.” Which is not to say this is all water off a duck’s back to poor Wilmot; he goes quietly insane, but recovers himself.

The Pybus Family, Nathaniel Dance-Holland This time for sure

The Pybus Family, Nathaniel Dance-Holland This time for sureThis section of the novel closes with Ellison’s death, which leaves Elfrida a widow for sure this time. Hannah’s eulogy for him goes thusly: “because he could not be happy himself, [he] took unending delight in destroying the happiness of others, but it was very good of him (she must needs acknowledge) to come and die amongst them, to prevent all doubts and demurs hereafter.”

It occasionally happens that a writer creates a character who develops a life of her own and takes over the story. This happens with the garrulous servant Hannah Jenkins. She pushes more and more to the fore in the novel, and provides a loud, insistent counterpoint to the sentimental conventions upheld by Elfrida. Hannah is having none of Elfrida’s sanctified heroism: “wanting to teach her [that is, Hannah,] sentimentals and dickorums [decorums]—and not to be joyful when she was glad, and sorrowful when she was afflicted—or angry when she was misused—or to hate her enemies, all which was against nature, law and conscience.” I was reminded of the novel Clarentine , and the wise old widow who tells Clarentine when she is being ridiculous.

Another notable thing about this section is that Elfrida becomes more and more unsympathetic because of her "principles of rectitude," which somehow end up with her coming and going as she pleases and abandoning all responsibility. Why is it the height of rectitude to refuse to comfort your husband while he dies, but then, after he dies, insist on a six-month mourning period before re-marrying the man you love and resuming family life with him and your young children? (Her mother persuades her to cut it down to four.)

The author describes Elfrida’s reunion with Wilmot thusly: “whilst Elfrida, by the assistance of her smelling-bottle, preserved herself from fainting,” and you’ve got to wonder if she’s being sarcastic.

All right, Elfrida is now Elfrida Wilmot for sure this time, Mr. Ellison’s two children are a beloved part of the family, the Overburys live to see this happy day, and… the end. Elfrida is "by a Lady," no-one knows who. I found one review: The New Lady's Magazine noticed what I noticed about Ellison being more than a cardboard cutout character. “The great merit of this novel is in drawing and supporting the character of Ellison, in which envy, jealousy, and a sarcastic ill-humour, are combined with some degree of generosity, and a heart not wholly insensible to gratitude… we cannot help suspecting that this picture is drawn from real life… The novel is in general, pathetic and interesting; the story and the characters are in many respects new…”

Werther, Cult of Sensibility Items of Interest:

Werther, Cult of Sensibility Items of Interest:I did wonder why I kept ploughing through the dismal third act, but I got an unexpected reward. I was not aware that one of Jane Austen’s pieces of juvenilia is a short tale called Frederic and Elfrida. It differs in plot from the novel (and of course it’s funny), but I believe that there’s a connection between this novel and Austen’s burlesque. I think we can add this novel to the list of titles that Austen read or knew about.

Austen's Frederic and Elfrida is thought to have been written when Austen was 11 years old, and it is posted online at the Republic of Pemberley. Or you can listen to Dr. Octavia Cox reading it here while reading along with the Austen's fair copy.

Other features:The author inserts a little editorial in praise of George III, the queen, and his family, and wishes that the dissipated aristocracy would imitate their family virtues.There is also a little editorial against reading bad novels but in favor of some good authors. I'll get back to that one day to compare it with Austen's editorial in Northanger Abbey.I think the author gave Ellison a bout of virulent smallpox before his marriage to Elfrida as a way of explaining why he and Elfrida have no children.Elfrida's coed education with two boys might be another progressive signal from the author, but on the other hand, it is presented as having a bad outcome.Like most noblemen in these novels, Lord S___ faces no legal consequences for attempted abduction and assault, although his character is damaged.The characters discuss the influential and best-selling novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, which Wilmot praises, but criticizes for its glamorization of suicide. Werther concerns a man in love with a girl engaged to someone else.This novel has no sub-plots to speak of, no gallery of kooky characters, no auxiliary couples except for some very minor mentions of Captain Venables and his wife. Hannah marries, then actually leaves her husband to stay loyal to the Overbury/Wilmot family and he dies alone. The narrator doesn't comment on the propriety of this. Previous post: A German melodrama

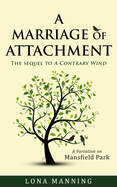

In my Mansfield Trilogy, a variation on Mansfield Park, Lieutenant William Price falls in love with Julia Bertram, but in addition to the difference in their station in life, he resolves not to ask Julia to face the hardships and separations of being a naval officer's wife. She is pressured to marry elsewhere. I tell their story in the second volume of the trilogy, A Marriage of Attachment.

Read more about my books here.

In my Mansfield Trilogy, a variation on Mansfield Park, Lieutenant William Price falls in love with Julia Bertram, but in addition to the difference in their station in life, he resolves not to ask Julia to face the hardships and separations of being a naval officer's wife. She is pressured to marry elsewhere. I tell their story in the second volume of the trilogy, A Marriage of Attachment.

Read more about my books here.

Published on March 06, 2024 00:00

February 29, 2024

CMP#175 Ella, the deserving heroine

As soon as I had dispatched this letter, I drew my sword, and was about to plunge it into my heart! An intense fever seized me at the instant, and prevented me from committing the rash deed! I fell motionless on the bed, and remained some moments in the grasp of death!

As soon as I had dispatched this letter, I drew my sword, and was about to plunge it into my heart! An intense fever seized me at the instant, and prevented me from committing the rash deed! I fell motionless on the bed, and remained some moments in the grasp of death! -- a sample of the prose! Of this book1 CMP#175 Deserving of a better novel, that is: Ella Rosenberg (1808), by William Herbert, Esq.

I can't even I’ve read 100 novels of the long 18th century, and William Herbert’s Ella Rosenberg is a strong candidate for the worst. Thankfully it's short--only two volumes, and most of volume one is taken up with a separate tale which has nothing to do with the main plot. I wouldn’t even bother to write up a synopsis of this novel, except that I had promised to make note of any novel which featured a "fallen woman" who did not subsequently die, and—oops, that’s a plot spoiler. Anyway.

I can't even I’ve read 100 novels of the long 18th century, and William Herbert’s Ella Rosenberg is a strong candidate for the worst. Thankfully it's short--only two volumes, and most of volume one is taken up with a separate tale which has nothing to do with the main plot. I wouldn’t even bother to write up a synopsis of this novel, except that I had promised to make note of any novel which featured a "fallen woman" who did not subsequently die, and—oops, that’s a plot spoiler. Anyway.Ella Rosenberg is a semi-historical melodrama set amidst jealous and bickering German nobility. It’s a Romeo-and-Juliet tale about Harold, who rescues a girl from drowning when her carriage veers in to a canal. He promptly falls madly in love with her, and then he destroys her life. That is, he insists on pressing his suit, and will not listen to his father’s very good advice to establish his military career and grow up a bit, before he thinks about marrying. No, instead, Harold takes his dad’s money, goes AWOL, stalks Ella at her family’s country retreat, enrages her father, a powerful Baron, and pressures Ella to elope with him...

Shelley-like behaviour Deluded Romeo

Shelley-like behaviour Deluded RomeoIs this a story about marrying for love instead of money? At first it appears so: the Baron “considered his daughter as an invaluable treasure, to be disposed of, like an article of merchandize, to the best bidder.” While Harold pleads and Ella agonizes, we have the lengthy interlude of the story of Julia and Hoffman, wherein a virtuous tenant farmer saves the lives of Julia and her noble mother and father, while her cowardly high-born fiancé runs away. Julia and Hoffman end up enjoying Love in a Cottage together.

By the way, Janeites will enjoy this tidbit, given to establish Ella's credentials as a lovely heroine: “her condescension made her idolized by a grateful tenantry, whose cottages she visited in person; and… when she entered the hovel of indigence or sickness... everywhere her footsteps left behind them the traces of pity and the balm of consolation.”

Ella eventually flees with Harold, after he threatens to kill himself, and it becomes immediately obvious that they haven’t thought things through. To be fair, the narrator says so as well, giving one of those "Take heed, young reader!" exhortations. Harold thought his uncle would take them in, but he refuses, because Ella's father is a powerful man. Ella now repents: “to you, have I sacrificed my peace and honor! My innocence and youth have this day been plunged into an abyss of shame, never to rise again! Complete your work—finish what you have began, and triumph over my virtue!"

Having no money (because Harold has managed to spend the 100 gold florins he took from his father) and no place to live, they do not consummate their relationship, and Harold wakes up in a rustic peasant's cottage to find Ella has left him to retire to a convent to atone for her filial disobedience.

AI's conception of the anonymous commenter "Oh Harold, you blackguard"

AI's conception of the anonymous commenter "Oh Harold, you blackguard"Broken-hearted, Harold enlists in the army under an assumed name, and because he can’t make use of the fact that he’s actually the son of a Count, he is stuck without advancement for eight long years. By sheer chance, he finds Ella—Ella Rosenberg that is, because for some reason, Harold calls the woman he loves “Ella Rosenberg” through the entire novel--she is now a successful tragedienne, travelling about the country with a troupe of actors. And you know what that means, it means she’s a fallen woman, a painted doxy. Harold visits her in her dressing room and upbraids her for a few pages for being a strumpet and a floozy. “'O, Ella Rosenberg,' said I, 'you are, indeed, an object of pity! –-Into what an abyss do I see you plunged!—How could you thus, inconsiderately, overstep the boundary of virtue?... But, are you bound for ever to this disgraceful employment?—Is all lost—no hope left?—Is your heart—that heart which formerly was the abode of the most precious innocence, so corrupted, so sunken below its former state, that it cannot recover itself?'” And on and on in the same vein. It is at this point that an exasperated reader wrote: "Oh Harold, you blackguard" in the margin of the digitized copy of the novel I'm reading online.

Ella tearfully explains that no convent would admit her, and she was saved from utter destitution by a kindly lady who saw her by the side of the road and offered to pour the "balm of consolation" on her wounded spirit. She turned out to be not a panderer, as you might expect. "I soon found, with vexation, that her profession was that of a comedian." (Oh no!) So Ella went on the stage.

This is not good enough for our hero, who promptly attacks Ella’s lover when he comes to visit, and wouldn’t you know it, it’s his superior officer. That means he goes straight to a prison cell to await his execution.

Enter the Abbott

Enter the AbbottWhen Harold is led to the scaffold, Ella dramatically rushes up and swallows some poison and dies. This makes the crowd insist that he be reprieved, so back to prison he goes, where he is visited by an abbot who had once been a member of his mother’s household. The abbot conducts him to a lonely prison cell in Horsa, because someone, somewhere, has commuted his sentence. We learn all this from a letter written from the prison cell by the “wretched Harold” himself. The sequel then commences, and everything that happens hereafter is because of the tireless efforts of that abbot who just dropped into the novel on page 152 of Volume 2. After six months in prison, the “benign abbot” informs Harold that he’s free to go. The abbot has also succeeded in melting the obdurate heart of Baron Rosenberg; he blames himself for his daughter’s suicide.

“O, I would give worlds to bring her back to life—to know she is not gone to prefer a filial curse against me at the bar of her heavenly parent!”

Dying repentant, Baron Rosenberg gives “the estate at Dorflein” to Harold with his last breath and asks to be buried there beside his daughter.

Fancy meeting you here: Bing AI image "Vicious" as in "vice"

Fancy meeting you here: Bing AI image "Vicious" as in "vice" There is a brief gothic flicker when Harold, visiting the tomb of his beloved, sees what he thinks is a beautiful statue. But hey, it’s Ella! Ella Rosenberg, to be precise! Not dead! She'd only had a "dreadful fit!" The abbot knew this all along!

No doubt her father would have liked to have known that before he died of grief and remorse over his daughter being buried in unconsecrated ground. On the other hand, the baron was also a murderer, a plot point which the author threw into a parenthetical mid-sentence interjection (see above left, an excerpt from the abbot's monologue).

Let’s skip to the unexpected happy ending: "Thus, sir, I finish my eventful history… grateful, with Ella Rosenberg, to an All-wise Providence, for his goodness, which often permits the feet of the best to slip, but will not suffer them finally to fall!"

So, Ella not only supported herself for eight years, but she is repentant and redeemed from her floozy lifestyle, and becomes a virtuous matron. Possibly the author was able to get away with no harsher punishment for Ella because the tale is set in a foreign country, at some indeterminate time in the past. Otherwise, the critics (if the critics had noticed this novel) would have condemned it, I think, for more than lousy writing. The author actually anticipates criticism on this point, because in a footnote, he writes: “It may be reproachfully urged against the author, that he has made his Ella Rosenberg partly a vicious character; while, on the contrary, all Novel writers depict only the Heroine: but he has rather endeavoured to paint the weakness of nature: and he submits to the Reader, whether experience be not on his side." "Heroine" in that sentence implies a "picture of perfection."

For reasons I can't explain, this novel was chosen by William Hazlitt in 1840 for inclusion in an anthology of novels, "The Best Works of the Best Authors." W. Herbert, Esq.'s name is likely a pseudonym. He also wrote The Spanish Outlaw (1807), also unreviewed.

For reasons I can't explain, this novel was chosen by William Hazlitt in 1840 for inclusion in an anthology of novels, "The Best Works of the Best Authors." W. Herbert, Esq.'s name is likely a pseudonym. He also wrote The Spanish Outlaw (1807), also unreviewed.Our current novel was “founded upon the famous [1807] melodrama of James Kenney, Ella Rosenberg,” according to pioneering scholar of gothic literature, Montague Summers. Well, except that it's very different. To be fair to Summers, he probably never got his hands on a copy of the novel back in 1941, in the pre-digital age.

Ella Rosenberg, the play, is a highly dramatic and emotional variation on King David and Bathsheba, in which a corrupt nobleman tries to destroy one of his officers so he can enjoy his beautiful wife. Virtue triumphs in the end, thanks to the local prince of whatever tinpot German principality the story is set in, and at Covent Garden the title role was played by no less than the great tragedienne Sarah Siddons. It’s such a pure melodrama that it’s rather fun to read. This novel, on the other hand, is funny for all the wrong reasons. But it's another example of how even young girls were expected to show agency in resisting the blandishments of their lovers.

I'm guessing the copycat name was done at the instruction of the publisher, JF Hughes, who was quite the unprincipled scamp. He published novels by "Mrs. Edgeworth" or "Caroline Burney" to trick people into thinking that the novel was by an Edgeworth or a Burney. He retitled a novel A Winter at Bath to imitate a rival publisher's A Winter in Bath. Perhaps the heroine originally had a different name like Friederike, and he said to the compositors: "replace the heroine's name with Ella Rosenberg" and they did the 18th-century version of "find and replace," and instead of "Ella" they always put in "Ella Rosenberg."

Previous post: Double feature: Margiana and Susan

Published on February 29, 2024 00:00

February 22, 2024

CMP#174 Margiana, a Heroine Austen Knew

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#174 A Novel Jane Austen Read and Another Novel She Might Have Read

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#174 A Novel Jane Austen Read and Another Novel She Might Have Read

Jane was hopping mad at Crosby Well, lately we’ve

had novel

after novel which focusses on heroines guarding their chastity at all costs. There were some other implicit values for female behaviour and they feature in the following two novels, one of which Austen read, and another which she might have read. These strictures are: (1) never complain about your husband and (2) never, ever confess your love to a man before he's said he loves you.

Jane was hopping mad at Crosby Well, lately we’ve

had novel

after novel which focusses on heroines guarding their chastity at all costs. There were some other implicit values for female behaviour and they feature in the following two novels, one of which Austen read, and another which she might have read. These strictures are: (1) never complain about your husband and (2) never, ever confess your love to a man before he's said he loves you.Susan, a novel, (1809) author unknown, was published in 1809 by J. Booth. Scholars surmise that the appearance of this novel spurred Jane Austen to write the publisher Benjamin Crosby, who had purchased the manuscript of her novel Susan (the gothic spoof which was finally published as Northanger Abbey), to ask him, when was he going to publish her novel? He, or rather his son Richard, replied that they owned the manuscript, they were under no obligation to publish it, and she could have the rights back by refunding the ten pounds she'd received for the manuscript. The matter rested for a few years more until Henry Austen, Jane's brother, paid the ten pounds and then informed Crosby that the manuscript he had spurned was by the author of the well-received novels Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice.

So we might expect that Jane Austen at least looked at the novel Susan. She also changed the name of her heroine from Susan to Catherine.

But first, let's look at a novel which we're pretty sure Austen read, because she joked about it in another one of her letters: Margiana, or Widdrington Tower (1808), by Mrs. Sykes.

Cross-dressing third heroine Keep a tight control on your heart

Cross-dressing third heroine Keep a tight control on your heartMargiana is a historical gothic romance, set in the 14th century at the outset of the Wars of the Roses. Margiana is beautiful and intelligent. Her younger sister Genevieve is also a beauty, but not as bright and resolute as Margiana. These medieval maidens live by the same rule of conduct which Juliet references when Romeo overhears her declaring her love for him: "Fain would I dwell on form. Fain, fain deny what I have spoke!" Austen also alludes to it in Northanger Abbey: "no young lady can be justified in falling in love before the gentleman’s love is declared."

Margiana's sister Genevieve falls for their cousin Ethelred, but seeks to save her pride by remembering her sister's maxim: "that a woman ought never to put her affections out of her own power, unless she is certain of their being returned, as well as properly placed."

Ethelred rebukes a designing young villainess for making a pass at him: “when a lady obtrudes her affection in a quarter from whence none has ever been offered to her, she excites a sentiment more unlike to love than even hatred itself—contempt.”

Bing AI generated image Never complain, always forebear

Bing AI generated image Never complain, always forebearMargiana’s mother, Lady Widdrington, just like Lady Kenheath in our next novel Susan, loves her husband but nurses a lifelong wounded heart because he doesn’t love her back. Both husbands are disappointed that their wives haven’t presented them with a son. Both husbands had a first love and they married out of convenience, not love.

I’m not saying one novel is copied from another, I am saying that these are common tropes and situations which are recycled and used again and again in novels of this era.

Both this author and the anonymous author of Susan approve of women who put up with neglect and coldness without complaint. “Yet at no time, and to no person, was [Lady Widdrington] ever heard to complain.” She dies, still suffering. While Margiana is filled with filial piety for her father, she also sees he’s a bad husband; the lesson she draws is to be very careful about who you marry--in fact she is leery of getting married at all.

She will get married, but first we've got five volumes to get through, with battles and sieges and castles and prisoners and villains (something Austen joked about) and misunderstandings and hauntings, and surprises and secrets revealed in the final chapters around parentage. Jane Austen joked about travelling to Widdrington and getting locked up in a tower, something that happens to more than one character. I got annoyed with the hero Ethelred when he believed something derogatory to Genevieve’s virtue and would not back down. When she tells him to his face that she did not send him a certain letter, he contradicts her. The novel also features a sprightly, cross-dressing third heroine named Arlette who travels around in male garb.

One last point: This story is set back when everyone was a Catholic, so the authoress assures her readers that her heroine is not only beautiful, but discerning: “the serious principles Margiana had imbibed from her [mother] were those, not of bigotry, but of pure and true religion, unalloyed with the blind superstition of the times." Note, by the way, the word "serious" used as an allusion to religious principles. Austen also used the word this way, as explained by Brenda S. Cox in her book, Fashionable Goodness.

A fuller synopsis of Margiana is available in The Gothic Novel 1790-1830 by Ann B. Tracy.

Now, to the two-volume novel Susan...

Susan volunteers to teach the local children. Bing AI-generated image. Susan is Sweet Sixteen

Susan volunteers to teach the local children. Bing AI-generated image. Susan is Sweet Sixteen The parentage of our titular heroine is ambiguous. Someone pays for her to be reared in innocence and solitude on an island in a remote part of Scotland. Susan is fortunate in her kind and judicious guardian/governess, Mrs. Howard, an army officer’s widow. The house is rented from a Scottish laird, Lord Kenheath. Susan meets him one day when he arrives on the little ferryboat that brings mail and supplies from the mainland. She jumps up like a frightened roe, as a good maiden should, and makes to run away. She slips and nearly falls into the water; he catches her hand and saves her. He admires her extremely, and right away we feel the uneasy vibes.

Kenheath insists on taking her to Edinburgh to stay with him and his wife. This makes Mrs. Howard uneasy, given that Lord Kenheath is a good deal older and Susan is inexperienced in the ways of the world. But she receives a letter affirming that it’s all right with Susan’s mysterious father, whoever he is.

On the way there, the travelers are involved in a carriage accident, one of several which the author resorts to in the story. Her other means of keeping her characters in one place, or keeping them out of the way, is to strike them with illness. Austen gets the Grants out of her way in Mansfield Park by giving Mr. Grant gout, but think about how subtly she does it, compared to (ahem) some other authors. At any rate, in the course of this first accident, Susan is thrown together with Lord Kenheath’s orphaned nephew, Archibald Hamilton, and the two promptly fall in love.

Another relative, Mr. Stuart, also likes the new houseguest. Getting her alone, he asks her if she’d like to become his mistress. This kind of insult always brings out the feisty in our heroines: “The purity of her own bosom had, for some time, prevented her understanding the nature of his proposals; but she was no sooner convinced of their unvarnished meaning, than all the indignant pride of virtue took possession of her soul. In a very few words she expressed her abhorrence and contempt of both himself and his infamous offers, and immediately rushed from his presence.”

Just as in Charlotte Summers, Lord Kenheath advises Susan to not make a scene, that it is better for her reputation if the whole thing is hushed up. So what’s up with this Lord Kenheath? His wife is rather uneasy about his designs on the girl.

Bing AI-generated image Spoilers ahoy

Bing AI-generated image Spoilers ahoyAfter recovering from a serious fever, brought on by shock, Susan just wants to get back to her island, convinced that she won’t be able to marry Archibald since Lady Kenheath wants him to marry her daughter instead. A convenient carriage accident en route to her home brings her to the door of the MacLaurins, an ancient and numerous Scottish family who are gobsmacked by Susan’s resemblance to their long-lost beloved sister/daughter Mary, who eloped with some unknown man years ago.

Susan makes it back to her island, whither she is followed by young Donald MacLaurin, who has also fallen in love with her. A few days later, Archibald appears, to tell Susan that her beloved guardian Mrs. Howard is very ill with a fever, which is why she can't be there on the island during what follows. Archibald encounters Donald, high words ensue, and the two young men fight a duel on the front lawn. Archibald is the more severely wounded, and the only place for him to be treated and nursed is in Susan’s house.

The doctor says Archibald isn’t dying from his dueling wound, he’s dying from a broken heart, but even so, Susan won’t confess her love for him, because that would be immodest. A garrulous house guest, Mrs. Jane MacLaurin, bustles in to assure him that Susan doesn’t love Donald. Susan’s first thought is “Good heavens, Madam! He will certainly think I desired you to say all this. What an opinion must he entertain of me!” But as she thinks it over, she realizes it must be for the best that he learns that she loves him. It might save his life, after all.

The author still spares Susan from making a direct confession of her love. Once she has recovered enough from her own latest bout of fever and fainting fits (brought on by witnessing the duel), she sneaks into Archibald’s bedroom, thinking he is asleep, and sighs that she would willingly die for him. That’s good enough for Archibald, and he recovers.

Secrets Revealed

Secrets RevealedLord Kenheath comes to the island and confesses that yes, Susan is his daughter, born of a secret earlier marriage. His deserted bride died of childbirth and shock after reading in the newspaper that he was engaged to marry an heiress. She died on the very day of his wedding—which is important, because that spares him from being a bigamist and his second daughter from being illegitimate. Lord Kenheath’s behaviour as a youth was absolutely deplorable and he’s still a world-class jerk to his current wife, whose behaviour has been irreproachable. Lord Kenheath is the reason Susan grew up on an island without knowing any family. He's the reason the MacLaurins mourned their beloved, vanished, Mary for years. He's the reason we, the reader, had to experience the good ol' incest tease with both him and Uncle Stuart. So of course our heroine falls to her knees and asks him for his blessing because he’s her father! And she asks the MacLaurins to forgive him for eloping with and then abandoning their beloved Mary. Because that’s how heroines do.

At least both sides of the family now agree that Susan and Archibald should get married, and since they are the legatees of Mr. Stuart, who conveniently died of a fever after a horse-riding accident, they have the means to do so. Cue the bagpipes and the happy peasants dancing on the greensward.

The only resemblance to Northanger Abbey that I can see is surely a coincidental one: After meeting Archibald Hamilton, Susan retires to her bedchamber to dream of him. Northanger Abbey has no fainting fits, no high fevers, no duels, and Catherine Morland knows who her parents are.

Of Susan, the reviewer for the Monthly Review remarked: “The language is always modest, though sometimes ungrammatical; and the tale contains a prodigious number of fevers, together with several faintings, two duels, [I only caught one] and one or two deaths.”

Margiana, or Widdrington Tower, did not receive any reviews when it was published. In fact, it seems none of the three novels Henrietta Masterman Sykes (1766-1823) wrote received reviews, but she has received some critical attention more recently. Her contemporary novel Sir William Dorien (1812) has been called Dickensian. I would say that her prose style is relatively free from trite cliches, she keeps her poetry-writing urges to a minimum, and she is not afraid of taking on complex plots connected to historical events. In this historical novel she refrains from having her characters speak forsoothly.

Margiana, or Widdrington Tower, did not receive any reviews when it was published. In fact, it seems none of the three novels Henrietta Masterman Sykes (1766-1823) wrote received reviews, but she has received some critical attention more recently. Her contemporary novel Sir William Dorien (1812) has been called Dickensian. I would say that her prose style is relatively free from trite cliches, she keeps her poetry-writing urges to a minimum, and she is not afraid of taking on complex plots connected to historical events. In this historical novel she refrains from having her characters speak forsoothly.Jane Austen was a partisan of the Yorks in the Wars of the Roses, or at least she was as a teenager, as revealed in her juvenile composition, The History of England.

I haven't read much of historical fiction from this pre-Walter Scott era, but two of the best-selling authors in this genre were the Porter sisters. Jane Austen scholar Devoney Looser has deeply researched and written a joint biography of Jane and Anna Maria Porter, who wrote innovative titles in this genre. Looser's book, Sister Novelists is a detailed portrayal of a fascinating family and a vibrant age.

I wrote earlier about the forbearing wife here.

Previous post: The first First Impressions

Published on February 22, 2024 00:00

February 15, 2024

CMP#173 The first First Impressions

Marie de Vaublanc had just attained the age of seventeen, till which period sorrow had never obtruded itself on her youthful mind; she knew not, and therefore did not fear, the unsteadiness of Fortune. Alas! To the eye, accustomed only to a continued sunshine, how fearful must be a lowering sky!... --opening of First Impressions CMP#173 Book Review: First Impressions, or, the Portrait (1801)

Marie de Vaublanc had just attained the age of seventeen, till which period sorrow had never obtruded itself on her youthful mind; she knew not, and therefore did not fear, the unsteadiness of Fortune. Alas! To the eye, accustomed only to a continued sunshine, how fearful must be a lowering sky!... --opening of First Impressions CMP#173 Book Review: First Impressions, or, the Portrait (1801)

Hapless heroine thrown upon the world. AI generated image. My latest article in

Jane Austen's Regency World

magazine (Jan/Feb 2024 issue) concerns the novel First Impressions by Margaret Holford. As devoted Janeites know, First Impressions was Austen's original title for Pride and Prejudice, and it's generally thought she changed the title because Holford's novel came out first, in 1801. Perhaps, having heard of the novel, Austen got her hands on a copy, to see how it compared with her own unpublished work. I think there are indications in Pride and Prejudice that Austen indeed read and drew some inspiration from First Impressions. For that matter, astute Janeites will spot a slight similarity between the opening of the novel, which I quoted above, and the opening of another Austen novel. But I won't take that up in this post. Instead, here's a plot synopsis. You'll see that this novel continues our theme of girls who must fight to preserve their virtue. The titillation of the tale arises from the perils to which Maria is exposed, and the moral lessons arise from the lengths to which our heroine will go to preserve her virgin honour.

Hapless heroine thrown upon the world. AI generated image. My latest article in

Jane Austen's Regency World

magazine (Jan/Feb 2024 issue) concerns the novel First Impressions by Margaret Holford. As devoted Janeites know, First Impressions was Austen's original title for Pride and Prejudice, and it's generally thought she changed the title because Holford's novel came out first, in 1801. Perhaps, having heard of the novel, Austen got her hands on a copy, to see how it compared with her own unpublished work. I think there are indications in Pride and Prejudice that Austen indeed read and drew some inspiration from First Impressions. For that matter, astute Janeites will spot a slight similarity between the opening of the novel, which I quoted above, and the opening of another Austen novel. But I won't take that up in this post. Instead, here's a plot synopsis. You'll see that this novel continues our theme of girls who must fight to preserve their virtue. The titillation of the tale arises from the perils to which Maria is exposed, and the moral lessons arise from the lengths to which our heroine will go to preserve her virgin honour. Holford's First Impressions is a four volume novel, and although the action drags a bit in the middle as we suffer along with the heroine through her various vicissitudes, I have to say it starts out with a bang--Holford wastes no time in setting up her heroine to be both penniless and friendless. Her plight is not a very good reflection on the foresight of her late guardian, Madame de Vaublanc, when it comes to estate planning. We have to assume that good old lady didn’t realize her cousin and executor was dishonest and corrupt, although the fact that his name is “Gripe” should have tipped off any cautious woman...

Harassed wherever she goes: The Irritating Gentleman, Woltze Who's up for a reformed rake story?

Harassed wherever she goes: The Irritating Gentleman, Woltze Who's up for a reformed rake story?It is “brutally revealed” to Marie by this lawyer/cousin that she is not a de Vaublanc. They rename her "Maria Clive." No-one knows who her parents are, and the Gripes are not obliged to help her. Mrs. Gripe gives Sense and Sensibility's Fanny Dashwood a run for her money--Marie will be permitted to keep only the clothes on her back.

Maria is told she's been given a job as a governess. She is packed off to a distant English country house but when she arrives there, after travelling unescorted by mail coach, she discovers it’s the home of Sir Edwin, a roguish baronet. The woman from the employment agency was actually a panderer, and Maria—an extremely beautiful girl—has been sent there for the rake's approval.

Luckily for Maria, Sir Edwin is away from home, which gives her time to win over the old housekeeper and convince her that she is not a shameless floozy but a genuine virginal innocent. The neighborhood, however, assumes differently—otherwise why would she be there? No smoke without fire, you know. In addition, Maria's unknown parentage means she might be illegitimate. This, plus her poverty, make her ineligible for a good marriage and highly eligible to be propositioned wherever she goes. Remember how Mr. Knightley in Emma talks about how Harriet Smith will be "retired enough for safety... never led into temptation, nor left for it to find her out." That's what he's talking about.

When Sir Edwin does come home, he is enchanted with Maria and offers her a fortune if she'll be his mistress. She eloquently and vigorously refuses--he is surprised at her, and ashamed of himself. We learn that Sir Edwin, in an act of careless bravado, recently vowed he would marry the first truly chaste and virtuous woman he met, since he believed no such woman could exist. But here she is, a transcendently beautiful girl warbling a Rossini aria at an ivy-covered window. Maria’s vocabulary and formal way of speaking makes it clear that she is genteel, intelligent and well-educated, and whatever her current position in life, she came from better things.

Northanger Abbey's John Thorpe The Perils of a "Picture of Perfection" Heroine