Lona Manning's Blog, page 31

October 30, 2017

My Dad at Yonsei University

My father, J. McRee "Mac" Elrod, died last summer at age 84. I have always been in awe of the fact that he and my mother spent five years in Korea soon after the end of the Korean war , as very young teaching missionaries. They came with a red-headed baby boy, my brother Mark, and added two more kids while there -- me and my sister Cara.

When my dad reported for work at Yonsei University on the outskirts of Seoul 60 years ago, the small collection of library books was protected from theft behind a barrier of chicken-wire. The card catalogue, I recall father saying, was ravaged by soldiers taking the cards to line their shoes. In the winter, the ink froze in the inkwells.

My father pioneered the adaptation of Western cataloguing methods for Asian library materials, while still in his early twenties. In fact he was the first Western-trained professional librarian in Korea. He did away with the chicken wire and during his time, the library collection grew from 3,000 to 30,000 volumes.

My father also helped establish the first department of library science at Yonsei University, training future librarians. That department celebrated its 60th anniversary this past summer, and last week I popped over to South Korea to tour the campus and admire his legacy.

My father also helped establish the first department of library science at Yonsei University, training future librarians. That department celebrated its 60th anniversary this past summer, and last week I popped over to South Korea to tour the campus and admire his legacy.The professors of the library science department were very gracious and welcoming to me. I shared some stories about my parents' time in Seoul, and they arranged for some graduate students to show me around. (Just about every person I spoke to in Korea spoke English well.) It was an absolutely gorgeous autumn day.

The original quadrangle of grey brick buildings is still there, looking beautiful in autumn colours. The library used to be housed in one of these buildings. I wish I could say that I remember toddling around those beautiful buildings, those stairs and the portico, but I left South Korea when I was two, and sadly, I don't recall it. But we grew up listening to dad's stories about life in Korea.

What a contrast to compare life in South Korea 60 years ago with the country today! Once ravaged by war (Seoul changed hands multiple times during the conflict), South Korea is now a prosperous modern nation.

Korean painted roof detail I don't want to say "Westernized" because that is not quite accurate and perhaps even patronizing. They maintain their own culture, cuisine and language and have their

own unique alphabet

. A lot of their physical past has been destroyed by war and colonial occupation.

Korean painted roof detail I don't want to say "Westernized" because that is not quite accurate and perhaps even patronizing. They maintain their own culture, cuisine and language and have their

own unique alphabet

. A lot of their physical past has been destroyed by war and colonial occupation.The young kids like hip hop, gangsta clothing, and many of them dye and streak their hair. South Koreans have all the modern conveniences, including screaming fast internet everywhere, modern transportation, toilet seats that will wash and dry your bottom, and their own K-pop music and Korean soap operas, which are also quite popular in China. Here's a link to my favourite historical soap opera.

Visiting the library at Yonsei, I marveled at how different it was from dad's day. They have 3D printers and virtual reality rooms. Probably the old-fashioned books are one of the lesser-used resources in the library!

I remember my dad remarking that you know you're old when you spot some item that you used every day in your youth for sale in an antique shop. For me, growing up in and around libraries, the card catalogue cabinets with their little square drawers were a familiar feature of life before the digital revolution. Now perhaps some young people would not even recognize what they are, or how they were used.

My student guides and I were walking through the lobby at the library and I spotted a section of card catalogue drawers, from dad's time at the library, being used a decorative accent. It even has some of the original library cards inside! How nice that someone thought to save this!

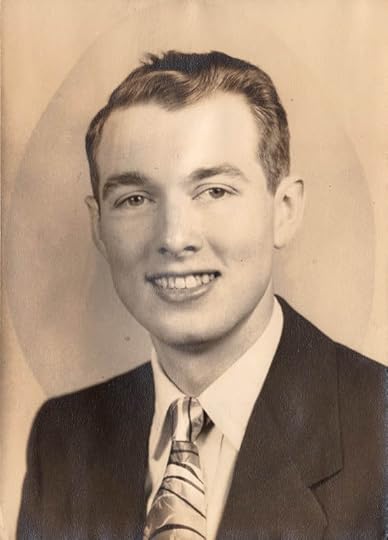

After my father died, we contributed his papers to his alma mater, the University of Georgia, and I contacted the faculty at Yonsei to ask if they could put up a sign or something to commemorate him. We sent them a picture of Dad as a young man, and they made a nice picture with it, which they plan to hang in the library science computer lab, because that's where all the students gather. They hung it up temporarily while I was there.

After my father died, we contributed his papers to his alma mater, the University of Georgia, and I contacted the faculty at Yonsei to ask if they could put up a sign or something to commemorate him. We sent them a picture of Dad as a young man, and they made a nice picture with it, which they plan to hang in the library science computer lab, because that's where all the students gather. They hung it up temporarily while I was there.I love the little bit of a cosmic joke here, because if there is one thing that would drive Dad batty (okay, there were lots of things that would drive Dad batty) it was -- pictures hung too high! So perhaps he will be hanging on the wall -- too high for his tastes, that is -- for years to come at the university where he contributed so much, many many years ago.

The caption on the portrait reads: "J. McRee Elrod (1932-2016) B.A., M.A., M.A., M.S. Methodist missionary, Librarian, Yonsei University, 1955-1960"

The caption on the portrait reads: "J. McRee Elrod (1932-2016) B.A., M.A., M.A., M.S. Methodist missionary, Librarian, Yonsei University, 1955-1960"

Published on October 30, 2017 06:30

October 18, 2017

Don't Miss the Fanny vs Mary Debates -- coming next week

Fanny Price or Mary Crawford — who do you like best? Is Fanny the sweet heroine of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park or is she a two-faced wimp? Is Mary Crawford a charming and misunderstood socialite or is she selfish and immoral?

Fanny Price or Mary Crawford — who do you like best? Is Fanny the sweet heroine of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park or is she a two-faced wimp? Is Mary Crawford a charming and misunderstood socialite or is she selfish and immoral? Kyra C Kramer and I take up our pens in defense of these literary frenemies for a no-holds-barred debate, held over five days on the internet. Follow along and join the debate in the comments!

Monday, October 23rd: Just Jane 1813, Claudine Pepe, justjane1813@gmail.com

Tuesday, October 24th: Diary of an Eccentric, Anna Horner, diaryofaneccentric@hotmail.com

Wednesday, October 25th: Savvy Verse and Wit, Serena Agusto-Cox, savvyverseandwit@gmail.com

Thursday, October 26th: My Jane Austen Book Club, Maria Grazia, learnonline.mgs@gmail.com

Friday, October 27th: Austenesque Reviews, Meredith Esparza, merry816@gmail.com

Published on October 18, 2017 18:38

September 14, 2017

Teachers, Students and Hobby Horses

I wrote my "teaching philosophy" a few years ago and stand by it today. Competence in English can only be attained by students who acquire some cultural literacy,* therefore we should not be afraid of introducing Western culture into the classroom.  Now it's time for me to add a big caveat. I have read blog posts and articles by teachers who say, in effect, "hell yeah, I indoctrinate my students with my opinions." That really concerns me.

Now it's time for me to add a big caveat. I have read blog posts and articles by teachers who say, in effect, "hell yeah, I indoctrinate my students with my opinions." That really concerns me.

These same people would probably have very disparaging things to say about the Christian missionaries who went to China in days gone by, sincerely believing that they were saving heathen souls from damnation. But if you are forcing your worldview on your students, what makes you any different from a missionary? The 'fact' that your opinions are right and theirs were wrong? A recent article in the EL Gazette argues that teachers "should consider introducing social justice issues" into the classroom. It begins: "English language teaching is sometimes regarded as a neutral, value-free endeavour. We teach the medium, not the message."

Okay, so we are teaching grammar and tenses and so forth. Gotcha. But suddenly, one paragraph down, our hypothetical English teacher is denigrated as a mere "technician," "transmitting McDonaldised content (mini-chunks of easily digested junk)."

Ouch!

Suddenly we're teaching grammar.... for The Man!

But, how does the author, J.J. Wilson, deal with the objection that teachers should keep their opinions out of the classroom? He deals with it by explaining that it's impossible: "Everything the teacher does in class reflects her beliefs about education, about people and about the world.... educators cannot help revealing deeply held beliefs." Somehow, the proposition that we can't keep our beliefs out of the classroom becomes, we should bring our beliefs into the classroom. The sentence he uses to make this transition is, and I quote: "And so..... to social justice." And so.... as I read this article, I'm thinking: okay, pejorative language, check, strawman, check, false dilemma, check.

Having established (?) that it is impossible to not be biased, the author then moves on to do some serious question begging, assuming that the reader will agree with him that teachers who are "energised" by the "global malaise" will want to engage their students in "real discussions about real issues." Which means, naturally teaching social justice.

The article discusses how to "subvert the syllabus" and gives examples of how to do it.

Hmmm, 'subvert,' that's an interesting choice of word. Not "introduce" or "adapt." I like teaching word families to my students, so if "subvert" came up, I'd jot the other forms on the board.... Subvert, verb, subversion, noun, subversive, adjective..... To subvert means, the teacher is not doing what he or she was hired to do, and is instead hijacking the classroom for their own agenda. Again, Wilson assumes that we agree this would be a good thing because..... social justice. And this is how the writer describes some hypothetical ESL students: "Many believe in the middle-class aspirational values so common in textbooks. Many do see the world as a white, homogenised, consumerist candy store for grown-ups."

So how to approach this kind of student, a student who'd like to have a job, maybe own a house and have something to live on in old age? I gather that Wilson thinks it's best to not be openly contemptuous or condescending with them. Be gentle. Enlighten them -- but subversively. Do not "proselytise, but tell stories instead." Maybe with some parables, like those Christian missionaries did.

Use questions like: "why an employee in a supermarket is setting out genetically engineered fruit rather than tending her garden, why a line cook is taking orders from strangers instead of cooking for his family, why a woman is watching the children of the wealthy at a daycare centre rather than spending time with her own, why a musician is composing jingles for fizzy drinks rather than jamming with his friends."

Yes, why are people exchanging their specialized services for money to buy the things they want and need, or rather, things they probably shouldn't want, if we are to consult the tastes and opinions of Dr. Wilson?

There are indeed a number of ways to explain how this nightmare scenario came about, and many different facts could be adduced in support of the different opinions we might hold, but just note the enormous amount of question-begging going on here. My question -- and it's an obvious question, I know, but I have to ask it because it does not seem to have occurred to Wilson or his editors -- if he, a social justice warrior, thinks there are "assumptions to be questioned, or misconceptions to be challenged," how can he be certain that a confirmed radical Islamist, a misogynist, a racist, a Flat-Earther, or a fascist, don't completely agree with him about that? And of course they'd also agree that since we cannot purge ourselves of our beliefs, we might as well subvert the curriculum and introduce our beliefs in the classroom. What "misconceptions" do my students hold about abortion, the minimum wage, UFOs, universal health care, taxation, the age of the earth, 9/11, genetically modified food, and the first amendment, that I need to set them straight about?

For the record, I wouldn't be afraid of discussing any of these subjects with older students, because I take care to present, as best as I can, what people say about both sides of the issue, and then ask them how they feel about it.

But it's very obvious from the article that Dr. Wilson regards his own worldview and opinions as the correct ones, because he is against "injustice." To cite just one example, his opinions and mine about the causes of injustice in Palestine and Israel might be very different. Yet, because he uses the magic words, "social justice," he has a license to promote his views as the correct ones.

In my teaching philosophy, I referred disparagingly to the notion that kids today just need to learn "critical thinking," as opposed to learning, you know, facts and stuff like math and history. The EL Gazette article demonstrates why it is essential that students are taught the rudiments of formal logic, and learn how to recognize fallacious and poorly presented arguments. Should they have the misfortune of being trapped in a classroom with a professor who abuses his position in this fashion (which was certainly my experience in college), they will be better equipped to analyze what they are being told, better able to ask questions that test those assumptions and misconceptions.

I enjoyed teaching the rudiments of logic and rhetoric in my ESL debate class. Over at my ESL materials page, there is a "Fact vs Opinion" quiz that I wrote which available for downloading, for intermediate students.

Another exercise I do with students in oral English classes is to ask them, what services should government provide, and list down all of the things they say on the blackboard, and ask them, "should the government take care of old people who have no money?" "should the government do this, or that?" And then I ask them, what percentage of their taxes would they give to the government, to have all the things they say governments should do? The exercise reminds young people about how society is structured, and hopefully gets them thinking about how much government they want, and at what price.

And Dr. Wilson's article would be a very useful reading to bring into a logic and rhetoric class, abounding as it does in examples of logical fallacies. *cultural literacy -- when a word or phrase refers to something that the writer and reader both understand, a shared cultural reference. Terms like "Salem witch hunt" are a type of shorthand to express a bigger idea. What is a hobby horse? The term comes from Laurence Sterne's novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, and it means, someone's pet opinions. And Dr Wilson's pejorative reference to McDonaldised content is another example.

Now it's time for me to add a big caveat. I have read blog posts and articles by teachers who say, in effect, "hell yeah, I indoctrinate my students with my opinions." That really concerns me.

Now it's time for me to add a big caveat. I have read blog posts and articles by teachers who say, in effect, "hell yeah, I indoctrinate my students with my opinions." That really concerns me.These same people would probably have very disparaging things to say about the Christian missionaries who went to China in days gone by, sincerely believing that they were saving heathen souls from damnation. But if you are forcing your worldview on your students, what makes you any different from a missionary? The 'fact' that your opinions are right and theirs were wrong? A recent article in the EL Gazette argues that teachers "should consider introducing social justice issues" into the classroom. It begins: "English language teaching is sometimes regarded as a neutral, value-free endeavour. We teach the medium, not the message."

Okay, so we are teaching grammar and tenses and so forth. Gotcha. But suddenly, one paragraph down, our hypothetical English teacher is denigrated as a mere "technician," "transmitting McDonaldised content (mini-chunks of easily digested junk)."

Ouch!

Suddenly we're teaching grammar.... for The Man!

But, how does the author, J.J. Wilson, deal with the objection that teachers should keep their opinions out of the classroom? He deals with it by explaining that it's impossible: "Everything the teacher does in class reflects her beliefs about education, about people and about the world.... educators cannot help revealing deeply held beliefs." Somehow, the proposition that we can't keep our beliefs out of the classroom becomes, we should bring our beliefs into the classroom. The sentence he uses to make this transition is, and I quote: "And so..... to social justice." And so.... as I read this article, I'm thinking: okay, pejorative language, check, strawman, check, false dilemma, check.

Having established (?) that it is impossible to not be biased, the author then moves on to do some serious question begging, assuming that the reader will agree with him that teachers who are "energised" by the "global malaise" will want to engage their students in "real discussions about real issues." Which means, naturally teaching social justice.

The article discusses how to "subvert the syllabus" and gives examples of how to do it.

Hmmm, 'subvert,' that's an interesting choice of word. Not "introduce" or "adapt." I like teaching word families to my students, so if "subvert" came up, I'd jot the other forms on the board.... Subvert, verb, subversion, noun, subversive, adjective..... To subvert means, the teacher is not doing what he or she was hired to do, and is instead hijacking the classroom for their own agenda. Again, Wilson assumes that we agree this would be a good thing because..... social justice. And this is how the writer describes some hypothetical ESL students: "Many believe in the middle-class aspirational values so common in textbooks. Many do see the world as a white, homogenised, consumerist candy store for grown-ups."

So how to approach this kind of student, a student who'd like to have a job, maybe own a house and have something to live on in old age? I gather that Wilson thinks it's best to not be openly contemptuous or condescending with them. Be gentle. Enlighten them -- but subversively. Do not "proselytise, but tell stories instead." Maybe with some parables, like those Christian missionaries did.

Use questions like: "why an employee in a supermarket is setting out genetically engineered fruit rather than tending her garden, why a line cook is taking orders from strangers instead of cooking for his family, why a woman is watching the children of the wealthy at a daycare centre rather than spending time with her own, why a musician is composing jingles for fizzy drinks rather than jamming with his friends."

Yes, why are people exchanging their specialized services for money to buy the things they want and need, or rather, things they probably shouldn't want, if we are to consult the tastes and opinions of Dr. Wilson?

There are indeed a number of ways to explain how this nightmare scenario came about, and many different facts could be adduced in support of the different opinions we might hold, but just note the enormous amount of question-begging going on here. My question -- and it's an obvious question, I know, but I have to ask it because it does not seem to have occurred to Wilson or his editors -- if he, a social justice warrior, thinks there are "assumptions to be questioned, or misconceptions to be challenged," how can he be certain that a confirmed radical Islamist, a misogynist, a racist, a Flat-Earther, or a fascist, don't completely agree with him about that? And of course they'd also agree that since we cannot purge ourselves of our beliefs, we might as well subvert the curriculum and introduce our beliefs in the classroom. What "misconceptions" do my students hold about abortion, the minimum wage, UFOs, universal health care, taxation, the age of the earth, 9/11, genetically modified food, and the first amendment, that I need to set them straight about?

For the record, I wouldn't be afraid of discussing any of these subjects with older students, because I take care to present, as best as I can, what people say about both sides of the issue, and then ask them how they feel about it.

But it's very obvious from the article that Dr. Wilson regards his own worldview and opinions as the correct ones, because he is against "injustice." To cite just one example, his opinions and mine about the causes of injustice in Palestine and Israel might be very different. Yet, because he uses the magic words, "social justice," he has a license to promote his views as the correct ones.

In my teaching philosophy, I referred disparagingly to the notion that kids today just need to learn "critical thinking," as opposed to learning, you know, facts and stuff like math and history. The EL Gazette article demonstrates why it is essential that students are taught the rudiments of formal logic, and learn how to recognize fallacious and poorly presented arguments. Should they have the misfortune of being trapped in a classroom with a professor who abuses his position in this fashion (which was certainly my experience in college), they will be better equipped to analyze what they are being told, better able to ask questions that test those assumptions and misconceptions.

I enjoyed teaching the rudiments of logic and rhetoric in my ESL debate class. Over at my ESL materials page, there is a "Fact vs Opinion" quiz that I wrote which available for downloading, for intermediate students.

Another exercise I do with students in oral English classes is to ask them, what services should government provide, and list down all of the things they say on the blackboard, and ask them, "should the government take care of old people who have no money?" "should the government do this, or that?" And then I ask them, what percentage of their taxes would they give to the government, to have all the things they say governments should do? The exercise reminds young people about how society is structured, and hopefully gets them thinking about how much government they want, and at what price.

And Dr. Wilson's article would be a very useful reading to bring into a logic and rhetoric class, abounding as it does in examples of logical fallacies. *cultural literacy -- when a word or phrase refers to something that the writer and reader both understand, a shared cultural reference. Terms like "Salem witch hunt" are a type of shorthand to express a bigger idea. What is a hobby horse? The term comes from Laurence Sterne's novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, and it means, someone's pet opinions. And Dr Wilson's pejorative reference to McDonaldised content is another example.

Published on September 14, 2017 23:25

September 5, 2017

The Secret's Out!

On the heels of the very successful The Darcy Monologues, Christina Boyd has conceived and rounded up a new anthology of short stories featuring Jane Austen's "bad boys." And yours truly was asked to contribute a story!  It was a real pleasure and an honour to contribute to this project. And it wasn't easy keeping quiet about this news all summer! If you head over to Babblings of a Bookworm, or Austenesque Reviews, you can enter a draw for a free copy and some other great Austen-themed prizes! This November, you can read the works of eleven different devoted Janeite writers, each one exploring the personality and back story of a different Austen character, such as John Thorpe and Colonel Tilney from Northanger Abbey, Willoughby from Sense & Sensibility, and of course Mansfield Park's Henry Crawford, is represented. It will be very interesting to see what eleven different authors do with their assigned gentleman rogue!

It was a real pleasure and an honour to contribute to this project. And it wasn't easy keeping quiet about this news all summer! If you head over to Babblings of a Bookworm, or Austenesque Reviews, you can enter a draw for a free copy and some other great Austen-themed prizes! This November, you can read the works of eleven different devoted Janeite writers, each one exploring the personality and back story of a different Austen character, such as John Thorpe and Colonel Tilney from Northanger Abbey, Willoughby from Sense & Sensibility, and of course Mansfield Park's Henry Crawford, is represented. It will be very interesting to see what eleven different authors do with their assigned gentleman rogue!

It was a real pleasure and an honour to contribute to this project. And it wasn't easy keeping quiet about this news all summer! If you head over to Babblings of a Bookworm, or Austenesque Reviews, you can enter a draw for a free copy and some other great Austen-themed prizes! This November, you can read the works of eleven different devoted Janeite writers, each one exploring the personality and back story of a different Austen character, such as John Thorpe and Colonel Tilney from Northanger Abbey, Willoughby from Sense & Sensibility, and of course Mansfield Park's Henry Crawford, is represented. It will be very interesting to see what eleven different authors do with their assigned gentleman rogue!

It was a real pleasure and an honour to contribute to this project. And it wasn't easy keeping quiet about this news all summer! If you head over to Babblings of a Bookworm, or Austenesque Reviews, you can enter a draw for a free copy and some other great Austen-themed prizes! This November, you can read the works of eleven different devoted Janeite writers, each one exploring the personality and back story of a different Austen character, such as John Thorpe and Colonel Tilney from Northanger Abbey, Willoughby from Sense & Sensibility, and of course Mansfield Park's Henry Crawford, is represented. It will be very interesting to see what eleven different authors do with their assigned gentleman rogue!

Published on September 05, 2017 06:37

August 25, 2017

Spot the spoof, or, the anguish of the apricots

While reading Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, I had the irresistible idea of trying my own hand at writing a spoof of the type of literary criticism that Helena Kelly employs. It was surprisingly easy -- I had my parodies, published below, written in under an hour. Modern literary criticism contains two basic elements: One, drawing connections between disparate things in the book which have no obvious relevance to the plot or the theme and finding symbolism where none was intended. This is an especially clever technique because it is non-falsifiable. You can pronounce that some inanimate object in the book is freighted with meaning, and nobody can dig the author up out of her grave to contradict you.  Nothing was wanting but to be happy when they got there Secondly, investing classic literature with overtones of modern attitudes towards sex, gender identity, colonialism, imperialism, race and intersectionalism.

Nothing was wanting but to be happy when they got there Secondly, investing classic literature with overtones of modern attitudes towards sex, gender identity, colonialism, imperialism, race and intersectionalism.

Consider the picnic on Box Hill in Emma. We modern readers can't help thinking about the servants preparing, carrying and setting out the meal, and then waiting respectfully at a distance while the ladies and gentlemen sat and ate it, and then cleaning up after the ladies and gentlemen when they were all finished with their nice al fresco repast. But none of that is mentioned in the novel, only a passing reference to servants and carriages at the end of the passage. To Austen, servants were a fact of life. Half of the following excerpts are from Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical and half are parodies that I have written. She is quite serious, and I am just kidding. Can you tell which are which? Give your answers in the comments below! Seriously? 1. Then, too, an astonishing proportion of the surnames in Sense and Sensibility are metallic ones. We have the Steele sisters. We have the Ferrars family (that is, ferrous, containing iron). Willoughby’s rich cousin is called Mrs. Smith—a common name, true, and one that Jane uses in three separate novels, but nevertheless a smith is a worker of metal. Willoughby marries an heiress called Miss Grey, recalling the jeweler Gray’s; the sharing of names is something we’ll return to. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), a “gray” or “grey” is also a spot of discoloration that marks the flaw in a metal, particularly in a gun, and when we first encounter Willoughby, on the rainy hillside above Barton Cottage, he’s carrying a gun. 2. Shoes are more predominate in Emma than they are in any other of Jane's novels, although the word "shoe" itself appears only four times. This should not surprise us, for shoes both display and conceal, reveal and hide. We have Mr. Knightley with his thick leather gaiters, Emma's trouble with her shoes when she is walking with Harriet and Mr. Elton. Miss Bates is obsessed with shoes and whether they have gotten damp or dirty; as a clergyman's daughter, she knew that sandals were connected in the Bible with uncleanliness. If something unpleasant is picked up in the outside world, it can be thoughtlessly discarded by the privileged class in Highbury -- Emma's bootlace is tossed into a ditch, Isabella tells her father, "I could change my shoes the moment I get home." For them, there will always be more bootlaces and shoes. The gypsies, of course, are all bare-footed. 3. One of Miss Bingley's favourite words is 'delighted'. She tells Elizabeth Bennet, "I hear you are quite delighted with Wickham." That word is chosen deliberately. De-lighted of course has a double meaning -- a light can be extinguished, can be put out. Wickham's name is a revelation; "wick" refers to the wick of a candle, which was, apart from firewood, the chief source of light in Jane's world. "Ham" would have reminded astute readers of Ham, the son of Noah. They would have known the bible passage describing how Ham saw the nakedness of his father when Noah was passed out drunk. If Wickham is the senior Mr. Darcy's illegitimate son, could this be the real reason why Wickham has been cast out of Pemberley – does he know unspeakable truths about his own father? Can Wickham shed light on the hidden sins of Pemberley?

Seriously? 1. Then, too, an astonishing proportion of the surnames in Sense and Sensibility are metallic ones. We have the Steele sisters. We have the Ferrars family (that is, ferrous, containing iron). Willoughby’s rich cousin is called Mrs. Smith—a common name, true, and one that Jane uses in three separate novels, but nevertheless a smith is a worker of metal. Willoughby marries an heiress called Miss Grey, recalling the jeweler Gray’s; the sharing of names is something we’ll return to. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), a “gray” or “grey” is also a spot of discoloration that marks the flaw in a metal, particularly in a gun, and when we first encounter Willoughby, on the rainy hillside above Barton Cottage, he’s carrying a gun. 2. Shoes are more predominate in Emma than they are in any other of Jane's novels, although the word "shoe" itself appears only four times. This should not surprise us, for shoes both display and conceal, reveal and hide. We have Mr. Knightley with his thick leather gaiters, Emma's trouble with her shoes when she is walking with Harriet and Mr. Elton. Miss Bates is obsessed with shoes and whether they have gotten damp or dirty; as a clergyman's daughter, she knew that sandals were connected in the Bible with uncleanliness. If something unpleasant is picked up in the outside world, it can be thoughtlessly discarded by the privileged class in Highbury -- Emma's bootlace is tossed into a ditch, Isabella tells her father, "I could change my shoes the moment I get home." For them, there will always be more bootlaces and shoes. The gypsies, of course, are all bare-footed. 3. One of Miss Bingley's favourite words is 'delighted'. She tells Elizabeth Bennet, "I hear you are quite delighted with Wickham." That word is chosen deliberately. De-lighted of course has a double meaning -- a light can be extinguished, can be put out. Wickham's name is a revelation; "wick" refers to the wick of a candle, which was, apart from firewood, the chief source of light in Jane's world. "Ham" would have reminded astute readers of Ham, the son of Noah. They would have known the bible passage describing how Ham saw the nakedness of his father when Noah was passed out drunk. If Wickham is the senior Mr. Darcy's illegitimate son, could this be the real reason why Wickham has been cast out of Pemberley – does he know unspeakable truths about his own father? Can Wickham shed light on the hidden sins of Pemberley?

4. Almost immediately we are reminded of slavery and the complicity of landowners like Sir Thomas; Mrs. Price offers up one of her sons to go to Sir Thomas's West Indian estates – that is, his sugar plantations where his slaves toiled -- and another to go to Woolwich. Woolrich was a military academy. Only a few years previously to the events in Mansfield Park, the British Army had invaded what is now Haiti, intending to brutally put down the slave uprising there.

4. Almost immediately we are reminded of slavery and the complicity of landowners like Sir Thomas; Mrs. Price offers up one of her sons to go to Sir Thomas's West Indian estates – that is, his sugar plantations where his slaves toiled -- and another to go to Woolwich. Woolrich was a military academy. Only a few years previously to the events in Mansfield Park, the British Army had invaded what is now Haiti, intending to brutally put down the slave uprising there.

5. Mansfield Park includes repeated references to “pheasants,” game birds that were difficult to buy and that (like slaves, after the Mansfield ruling) couldn’t be legally recovered if they got away and so had to be carefully kept and carefully bred to maintain an adequate population. Jane barely mentions pheasants elsewhere in her writing. 6. Perhaps we’d do better to view the abrupt shifts, the gaps that open up in the text, as thematic. Persuasion features a lot of sudden drops and breaks. The words “fall” and “fell” appear more often in this short book than they do in Jane’s longer novels. The heroine Anne’s nephew falls from a tree and breaks his collarbone. Her headstrong rival in love, Louisa Musgrove, falls and cracks her skull on the Cobb at Lyme. Her father, Sir Walter, and eldest sister, Elizabeth, scrambling to maintain their social position, take a house on a street in Bath where planned building work had been halted because of landslides.

7. Jane makes a point of telling us that Captain Harville has gathered “something curious and valuable from all the distant countries” he’s visited; he displays them in his rented house in Lyme. Are we meant to imagine that he has already added, or will add, some of the Lyme “curiosities”—fossils—to his collection? There is, too, a faintly reptilian flavor to two of the ships Captain Wentworth has sailed on—the Asp and the Laconia. “Asp” is a poetic term for a snake. Sparta, in Laconia, was associated with serpents. There were dozens of other, non-reptilian ship names Jane could have borrowed or invented, but she doesn’t. 8. But a close reading of Mansfield Park reveals how Austen really intended for us to understand Fanny – there is the public Fanny and the hidden, secret Fanny who takes refuge in the East Room. More than a hundred years before the illness was diagnosed, Jane has given us a portrait of someone with dissociative identity disorder, commonly (and inaccurately) called, having a split personality. The truth is seen -- but not fully understood -- by Mrs. Norris, who says of her: "she likes to go her own way to work…. she certainly has a little spirit of secrecy." And it is Mrs. Norris who says, "Fanny is not one of those who can talk and work at the same time." But Fanny is not merely daydreaming, she has retreated from reality entirely. The uncomfortable truths of Mansfield Park are too painful. Click here for parts one, two and three of my review of Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical Click here for information about my novel, A Contrary Wind: a variation on Mansfield Park

8. But a close reading of Mansfield Park reveals how Austen really intended for us to understand Fanny – there is the public Fanny and the hidden, secret Fanny who takes refuge in the East Room. More than a hundred years before the illness was diagnosed, Jane has given us a portrait of someone with dissociative identity disorder, commonly (and inaccurately) called, having a split personality. The truth is seen -- but not fully understood -- by Mrs. Norris, who says of her: "she likes to go her own way to work…. she certainly has a little spirit of secrecy." And it is Mrs. Norris who says, "Fanny is not one of those who can talk and work at the same time." But Fanny is not merely daydreaming, she has retreated from reality entirely. The uncomfortable truths of Mansfield Park are too painful. Click here for parts one, two and three of my review of Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical Click here for information about my novel, A Contrary Wind: a variation on Mansfield Park

Nothing was wanting but to be happy when they got there Secondly, investing classic literature with overtones of modern attitudes towards sex, gender identity, colonialism, imperialism, race and intersectionalism.

Nothing was wanting but to be happy when they got there Secondly, investing classic literature with overtones of modern attitudes towards sex, gender identity, colonialism, imperialism, race and intersectionalism.Consider the picnic on Box Hill in Emma. We modern readers can't help thinking about the servants preparing, carrying and setting out the meal, and then waiting respectfully at a distance while the ladies and gentlemen sat and ate it, and then cleaning up after the ladies and gentlemen when they were all finished with their nice al fresco repast. But none of that is mentioned in the novel, only a passing reference to servants and carriages at the end of the passage. To Austen, servants were a fact of life. Half of the following excerpts are from Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical and half are parodies that I have written. She is quite serious, and I am just kidding. Can you tell which are which? Give your answers in the comments below!

Seriously? 1. Then, too, an astonishing proportion of the surnames in Sense and Sensibility are metallic ones. We have the Steele sisters. We have the Ferrars family (that is, ferrous, containing iron). Willoughby’s rich cousin is called Mrs. Smith—a common name, true, and one that Jane uses in three separate novels, but nevertheless a smith is a worker of metal. Willoughby marries an heiress called Miss Grey, recalling the jeweler Gray’s; the sharing of names is something we’ll return to. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), a “gray” or “grey” is also a spot of discoloration that marks the flaw in a metal, particularly in a gun, and when we first encounter Willoughby, on the rainy hillside above Barton Cottage, he’s carrying a gun. 2. Shoes are more predominate in Emma than they are in any other of Jane's novels, although the word "shoe" itself appears only four times. This should not surprise us, for shoes both display and conceal, reveal and hide. We have Mr. Knightley with his thick leather gaiters, Emma's trouble with her shoes when she is walking with Harriet and Mr. Elton. Miss Bates is obsessed with shoes and whether they have gotten damp or dirty; as a clergyman's daughter, she knew that sandals were connected in the Bible with uncleanliness. If something unpleasant is picked up in the outside world, it can be thoughtlessly discarded by the privileged class in Highbury -- Emma's bootlace is tossed into a ditch, Isabella tells her father, "I could change my shoes the moment I get home." For them, there will always be more bootlaces and shoes. The gypsies, of course, are all bare-footed. 3. One of Miss Bingley's favourite words is 'delighted'. She tells Elizabeth Bennet, "I hear you are quite delighted with Wickham." That word is chosen deliberately. De-lighted of course has a double meaning -- a light can be extinguished, can be put out. Wickham's name is a revelation; "wick" refers to the wick of a candle, which was, apart from firewood, the chief source of light in Jane's world. "Ham" would have reminded astute readers of Ham, the son of Noah. They would have known the bible passage describing how Ham saw the nakedness of his father when Noah was passed out drunk. If Wickham is the senior Mr. Darcy's illegitimate son, could this be the real reason why Wickham has been cast out of Pemberley – does he know unspeakable truths about his own father? Can Wickham shed light on the hidden sins of Pemberley?

Seriously? 1. Then, too, an astonishing proportion of the surnames in Sense and Sensibility are metallic ones. We have the Steele sisters. We have the Ferrars family (that is, ferrous, containing iron). Willoughby’s rich cousin is called Mrs. Smith—a common name, true, and one that Jane uses in three separate novels, but nevertheless a smith is a worker of metal. Willoughby marries an heiress called Miss Grey, recalling the jeweler Gray’s; the sharing of names is something we’ll return to. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), a “gray” or “grey” is also a spot of discoloration that marks the flaw in a metal, particularly in a gun, and when we first encounter Willoughby, on the rainy hillside above Barton Cottage, he’s carrying a gun. 2. Shoes are more predominate in Emma than they are in any other of Jane's novels, although the word "shoe" itself appears only four times. This should not surprise us, for shoes both display and conceal, reveal and hide. We have Mr. Knightley with his thick leather gaiters, Emma's trouble with her shoes when she is walking with Harriet and Mr. Elton. Miss Bates is obsessed with shoes and whether they have gotten damp or dirty; as a clergyman's daughter, she knew that sandals were connected in the Bible with uncleanliness. If something unpleasant is picked up in the outside world, it can be thoughtlessly discarded by the privileged class in Highbury -- Emma's bootlace is tossed into a ditch, Isabella tells her father, "I could change my shoes the moment I get home." For them, there will always be more bootlaces and shoes. The gypsies, of course, are all bare-footed. 3. One of Miss Bingley's favourite words is 'delighted'. She tells Elizabeth Bennet, "I hear you are quite delighted with Wickham." That word is chosen deliberately. De-lighted of course has a double meaning -- a light can be extinguished, can be put out. Wickham's name is a revelation; "wick" refers to the wick of a candle, which was, apart from firewood, the chief source of light in Jane's world. "Ham" would have reminded astute readers of Ham, the son of Noah. They would have known the bible passage describing how Ham saw the nakedness of his father when Noah was passed out drunk. If Wickham is the senior Mr. Darcy's illegitimate son, could this be the real reason why Wickham has been cast out of Pemberley – does he know unspeakable truths about his own father? Can Wickham shed light on the hidden sins of Pemberley?

4. Almost immediately we are reminded of slavery and the complicity of landowners like Sir Thomas; Mrs. Price offers up one of her sons to go to Sir Thomas's West Indian estates – that is, his sugar plantations where his slaves toiled -- and another to go to Woolwich. Woolrich was a military academy. Only a few years previously to the events in Mansfield Park, the British Army had invaded what is now Haiti, intending to brutally put down the slave uprising there.

4. Almost immediately we are reminded of slavery and the complicity of landowners like Sir Thomas; Mrs. Price offers up one of her sons to go to Sir Thomas's West Indian estates – that is, his sugar plantations where his slaves toiled -- and another to go to Woolwich. Woolrich was a military academy. Only a few years previously to the events in Mansfield Park, the British Army had invaded what is now Haiti, intending to brutally put down the slave uprising there.5. Mansfield Park includes repeated references to “pheasants,” game birds that were difficult to buy and that (like slaves, after the Mansfield ruling) couldn’t be legally recovered if they got away and so had to be carefully kept and carefully bred to maintain an adequate population. Jane barely mentions pheasants elsewhere in her writing. 6. Perhaps we’d do better to view the abrupt shifts, the gaps that open up in the text, as thematic. Persuasion features a lot of sudden drops and breaks. The words “fall” and “fell” appear more often in this short book than they do in Jane’s longer novels. The heroine Anne’s nephew falls from a tree and breaks his collarbone. Her headstrong rival in love, Louisa Musgrove, falls and cracks her skull on the Cobb at Lyme. Her father, Sir Walter, and eldest sister, Elizabeth, scrambling to maintain their social position, take a house on a street in Bath where planned building work had been halted because of landslides.

7. Jane makes a point of telling us that Captain Harville has gathered “something curious and valuable from all the distant countries” he’s visited; he displays them in his rented house in Lyme. Are we meant to imagine that he has already added, or will add, some of the Lyme “curiosities”—fossils—to his collection? There is, too, a faintly reptilian flavor to two of the ships Captain Wentworth has sailed on—the Asp and the Laconia. “Asp” is a poetic term for a snake. Sparta, in Laconia, was associated with serpents. There were dozens of other, non-reptilian ship names Jane could have borrowed or invented, but she doesn’t.

8. But a close reading of Mansfield Park reveals how Austen really intended for us to understand Fanny – there is the public Fanny and the hidden, secret Fanny who takes refuge in the East Room. More than a hundred years before the illness was diagnosed, Jane has given us a portrait of someone with dissociative identity disorder, commonly (and inaccurately) called, having a split personality. The truth is seen -- but not fully understood -- by Mrs. Norris, who says of her: "she likes to go her own way to work…. she certainly has a little spirit of secrecy." And it is Mrs. Norris who says, "Fanny is not one of those who can talk and work at the same time." But Fanny is not merely daydreaming, she has retreated from reality entirely. The uncomfortable truths of Mansfield Park are too painful. Click here for parts one, two and three of my review of Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical Click here for information about my novel, A Contrary Wind: a variation on Mansfield Park

8. But a close reading of Mansfield Park reveals how Austen really intended for us to understand Fanny – there is the public Fanny and the hidden, secret Fanny who takes refuge in the East Room. More than a hundred years before the illness was diagnosed, Jane has given us a portrait of someone with dissociative identity disorder, commonly (and inaccurately) called, having a split personality. The truth is seen -- but not fully understood -- by Mrs. Norris, who says of her: "she likes to go her own way to work…. she certainly has a little spirit of secrecy." And it is Mrs. Norris who says, "Fanny is not one of those who can talk and work at the same time." But Fanny is not merely daydreaming, she has retreated from reality entirely. The uncomfortable truths of Mansfield Park are too painful. Click here for parts one, two and three of my review of Helena Kelly's Jane Austen: the Secret Radical Click here for information about my novel, A Contrary Wind: a variation on Mansfield Park

Published on August 25, 2017 06:00

August 23, 2017

Jane Austen the Secret Radical review, part three of three

Part three: It's as clear as daylight To begin with, I want to repeat some distinctions I made in part two:

Kelly is not saying [Mansfield Park] is a romantic comedy novel that I don't happen to like, because I don't happen to like Fanny and Edmund. It just didn't hit the mark for me.

Nor is she saying, Well, books that mentioned slaves or 12-year-old girls getting married or Jewish money lenders used to be okay, in the past, but those subjects are problematic in today's world. And for some people, a book in which the main characters live off of slavery is too problematic to be read with enjoyment today. I am not going to dispute that. If you don't want to read Huck Finn, or The Merchant of Venice, or Romeo and Juliet or Mansfield Park, I think you are missing out on some great literature, but it's your choice. But, as I said, Kelly is going farther than that.

Kelly is saying, Austen intended for her readers to regard the main characters who get married at the end of the novel -- you know, like people always do at the end of a romantic comedy -- as bad, horrible people. Mansfield Park and Emma may look like romantic comedies on the surface but they are actually condemnations of slavery and the practise of land enclosure. Kelly is positively allergic to the humour in Austen. Of Knightley and Emma's happy union, Kelly writes, "the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man's terror." In case you don't recognize what she's talking about, it's a reference to this:

Kelly is positively allergic to the humour in Austen. Of Knightley and Emma's happy union, Kelly writes, "the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man's terror." In case you don't recognize what she's talking about, it's a reference to this:

Mrs. Weston's poultry-house was robbed one night of all her turkeys--evidently by the ingenuity of man. Other poultry-yards in the neighbourhood also suffered.--Pilfering was housebreaking to Mr. Woodhouse's fears.--He was very uneasy; and but for the sense of his son-in-law's protection, would have been under wretched alarm every night of his life.

Austen treats the theft of the poultry with mock-drama, but of course it's deadly serious to Kelly, a comedy of terrors. Slavery of course, is not funny. According to Kelly, Mansfield Park is "inescapably political," filled with veiled allusions to slavery which her contemporary readers would have understood. Yes, slavery is mentioned briefly and in passing in the novel and yes, Sir Thomas owns slaves. But that is not what the novel is about. And if some readers think I am making light of the subject of slavery in what follows, no. My intention is to make fun of over-exuberant literary detective work.

Slavery of course, is not funny. According to Kelly, Mansfield Park is "inescapably political," filled with veiled allusions to slavery which her contemporary readers would have understood. Yes, slavery is mentioned briefly and in passing in the novel and yes, Sir Thomas owns slaves. But that is not what the novel is about. And if some readers think I am making light of the subject of slavery in what follows, no. My intention is to make fun of over-exuberant literary detective work.

Did you think that when Austen began Mansfield Park with the phrase, "About thirty years ago," her readers would say to themselves, 'Okay, Miss Maria Ward met Sir Thomas Bertram thirty years ago?" No! They would think about slavery!

Her contemporary readers, upon reading the phrase, "About thirty years ago," were supposed to be instantly reminded, and mentally review, the events of the abolition campaign, the Zong case, Cowper's poem, the Haitian slave revolt, all of which transpired during the thirty years before the publication of Mansfield Park. They weren't going to think about Mozart, or how fashions had changed, or how they used to have a full head of hair back then, or how much the pound sterling was worth, or who was on the throne, they were – obviously – going to think about slavery. As you do, you know, whenever someone mentions courtships that occurred in previous decades. To resume, when Fanny has a headache and Edmund gives her a glass of Madeira wine, what are we supposed to think of? Take a guess. That's right – slavery!

To resume, when Fanny has a headache and Edmund gives her a glass of Madeira wine, what are we supposed to think of? Take a guess. That's right – slavery!

Or when Mary Crawford mentions the poet, Hawkins Browne? Well, his son once went to a dinner party with Dr. Johnson and slavery was discussed at that party! And everybody knows about Dr. Johnson. (That much is true, they did).

When young Julia mentions the Roman emperor Severus, what are we supposed to think about? Hint: Severus was an African. Yes, slavery!

No, actually, Severus is mentioned in a passage which is a comedic reference to a common topic of concern at the time -- how to educate girls and how much education girls should have. Instead of didactic passages where the novel's characters sit around and talk about female education, Austen shows, rather than tells, and is poking fun at the same time: "But, aunt, [Fanny] is really so very ignorant!—… I am sure I should have been ashamed of myself, if I had not known better long before I was so old as she is. ... How long ago it is, aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns!"

"But, aunt, [Fanny] is really so very ignorant!—… I am sure I should have been ashamed of myself, if I had not known better long before I was so old as she is. ... How long ago it is, aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns!"

"Yes," added [Julia]; "and of the Roman emperors as low as Severus; besides a great deal of the heathen mythology, and all the metals, semi-metals, planets, and distinguished philosophers."

"Very true indeed, my dears, [says Aunt Norris], but you are blessed with wonderful memories, and your poor cousin has probably none at all…. And remember that, if you are ever so forward and clever yourselves, you should always be modest; for, much as you know already, there is a great deal more for you to learn."

"Yes, I know there is, till I am seventeen….."

This is a funny, brilliant passage. Are we also supposed to be thinking about slavery while we are chuckling quietly? Ah yes, we are not supposed to be laughing. And did you think Mansfield Park ends with a happy couple getting married? No!

And did you think Mansfield Park ends with a happy couple getting married? No!

Timid little Fanny "has married a man who doesn't love her, who is a fool and a hypocrite." Austen has not written a hero and heroine who don't appeal to modern tastes, she deliberately wrote unlikeable main characters.

And did you think they will live happily ever after? No! You have forgotten about the apricots!

Here's the final, thunderously condemnatory passage in Kelly's chapter on Mansfield Park:

Thoroughly perfect, though the Moor Park apricot tree is still in the vicarage garden, a reminder of the evil that everyone knows about but no one is willing to discuss, a tree not of knowledge, but of forgetfulness. With every spoonful of apricot jam, every apricot tart that's served up on the parsonage table, Fanny will eat the fruits of slavery.

And the tree will keep on growing.

Why apricots? Because Kelly claims the word "Moor" in "Moor Park" is a subtle reference to slavery that Austen's readers would instantly understand.

"Is Jane really using this name, and this kind of apricot tree, out of all the alternatives, by accident? Is it just coincidence that it's the same word Shakespeare uses to describe the ethnicity of black Africans?"

But of course it's not the same word, it's a homonym. The Moorpark apricot is named after a landed estate called "Moor Park." "Moor" refers not to black people but wild, windswept heaths, moors, like in Wuthering Heights. Please don't tell Kelly about the word 'niggardly,' she'll have conniptions.

Of course, you can't make a good apricot tart without some sugar. Sugar was actually made by slaves, in horrible conditions. That's what they are making at Sir Thomas' plantation in Antigua. Hmm, the word "sugar" does not appear in Mansfield Park. Maybe if Austen had mentioned someone putting sugar in their tea, that would have been a more intelligible reference – to slavery! Easier to "get" than a homonym. But never mind, apricots = slaves. So what is Mansfield Park, if not a dark, subversive, "deeply troubling," indictment of slavery?

So what is Mansfield Park, if not a dark, subversive, "deeply troubling," indictment of slavery?

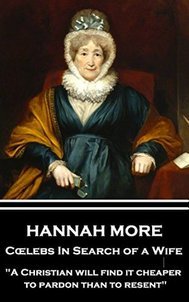

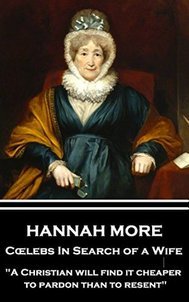

Mansfield Park, as many critics have knowledgeably explained, is Jane Austen's response to a genre of novel called the "conduct novel." Coelebs in Search of a Wife, a best-selling novel of the day, is a prime example. It features serious discussions of religion, piety, education and choosing a good wife or husband, all issues that are featured in Mansfield Park.

Once you know about conduct novels and what they were like, the style, structure and characters of Mansfield Park makes a lot more sense. Coelebs is a highly didactic book in which the characters sit around and talk. Austen is a better writer, she shows her characters wrestling with moral dilemmas, rather than talk about them.

But I'm not going to digress about that. Here is a link to a fantastic essay on the subject written by someone who possesses more than superficial knowledge about Regency times (women were oppressed back then, did you know?).

May I also recommend David Shapard's foreword in his annotated Mansfield Park. But what about the slaves? Well, for plot purposes, Austen had to have Sir Thomas go away for a long time, and she used the fact that he was on a dangerous sea voyage as one reason why the young people of Mansfield Park should not be amusing themselves with a play while their father was in peril of life or death. At the time of writing, because of the Napoleonic Wars, Sir Thomas couldn't go to Europe, so she had to give him a different destination. Slavery, which in fact is mentioned more explicitly by Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Elton in Emma, than by anyone in Mansfield Park, is simply not at the forefront of the story. Fanny and her brother One final oddity of Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, on which I'd like to comment, is that Kelly is elaborately cautious about making assumptions where the biographical details of Austen's life are concerned. She refuses to take the widely accepted stories at face value and in fact arrogantly accuses those who came before her of spreading "lies" about Austen. Do we know for a fact that it was First Impressions that her father offered to a publisher? Do we know for a fact that Harris Bigg-Wither proposed to Austen? No, we don't! It's just family "gossip." Did Edward Austen only give Chawton cottage to his mother and sisters because his wife had died and she could no longer object? "an intriguing coincidence, though one about which we can do no more than speculate."

Fanny and her brother One final oddity of Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, on which I'd like to comment, is that Kelly is elaborately cautious about making assumptions where the biographical details of Austen's life are concerned. She refuses to take the widely accepted stories at face value and in fact arrogantly accuses those who came before her of spreading "lies" about Austen. Do we know for a fact that it was First Impressions that her father offered to a publisher? Do we know for a fact that Harris Bigg-Wither proposed to Austen? No, we don't! It's just family "gossip." Did Edward Austen only give Chawton cottage to his mother and sisters because his wife had died and she could no longer object? "an intriguing coincidence, though one about which we can do no more than speculate."

But, she makes head-shakingly blithe assumptions from clues that only she can perceive in Austen's text. For example, read this passage:

[Henry Crawford] honoured the warm-hearted, blunt fondness of [Fanny's sailor brother William] which led [William] to say, with his hands stretched towards Fanny's head, 'Do you know, I begin to like that queer fashion already, though when I first heard of such things being done in England, I could not believe it; and when Mrs. Brown, and the other women at the Commissioner's at Gibraltar, appeared in the same trim, I thought they were mad; but Fanny can reconcile me to anything.'

Do you conclude, as does Kelly, that the "the intensity of William's reaction suggests that we are dealing here with cropped hair and not just short front ringlets."?

What? He's a young man saying when he first saw a new hairstyle, he thought it looked silly, but now that he sees it on his beloved sister's head, he is okay with it. What is 'intense' about that? Why does Kelly think hair has been cut, rather than styled? The expression, 'appeared in the same trim,' is a nautical expression. 'Trimming the sails,' does not mean cut the sails, right? It means adjusting them. Or is it the word 'queer'? Please tell me it's not the word 'queer' that has Kelly thinking Fanny is now wearing short hair. And in the end, Kelly does not explain what is so significant about short hair. Or maybe Harriet Smith is Jane Fairfax's sister because "Hetty" is the name of Jane Fairfax's grandmother. "Nothing in this book remains a mystery if we read it carefully – Harriet Smith and Jane Fairfax may well be half-sisters."

Or maybe Harriet Smith is Jane Fairfax's sister because "Hetty" is the name of Jane Fairfax's grandmother. "Nothing in this book remains a mystery if we read it carefully – Harriet Smith and Jane Fairfax may well be half-sisters."

Or maybe they are not. And if they were, why would Austen bury but not reveal the secret in Emma, a book that is filled with hints and clues that are all revealed in the end. What narrative purpose would that serve?

Jane Austen: the Secret Radical is not about Austen's innovations as a writer, her technique, her inimitable voice, her way with dialogue, or her characters. It's about a quest to find certain opinions and points of view embedded deeply within Austen's texts. Kelly has claimed to find these secret opinions, and no doubt she is as well-intentioned as was Emma Woodhouse, when she mistakenly thought she was successfully bringing Harriet Smith and Mr. Elton together. But her inclinations have led her astray and she has found clues that aren't there at all.

As for me, "I do not think I am particularly quick at those sort of discoveries. I do not pretend to it. What is before me, I see." Bonus: in my next post, I will reproduce four paragraphs from Helena Kelly's book, along with four parodies of my own. Will you be able to tell the real Kelly analysis from the parody? Stay tuned and see for yourself!

My recommendations for books about Austen:

What Matters in Jane Austen? Twenty Crucial Puzzles Solved, by John Mullan

Jane Austen and the Fiction of Her Time, by Mary Waldron

Only a Novel: The Double Life of Jane Austen, by Joan Aiken Hodge

Click here to learn about my novel, A Contrary Wind: a variation on Mansfield Park

click here for part one and part two of this review of Jane Austen: Secret Radical

Photos of Mansfield Park are from the 1983 mini-series, the only adaption of Mansfield Park that is faithful to the book.

Kelly is not saying [Mansfield Park] is a romantic comedy novel that I don't happen to like, because I don't happen to like Fanny and Edmund. It just didn't hit the mark for me.

Nor is she saying, Well, books that mentioned slaves or 12-year-old girls getting married or Jewish money lenders used to be okay, in the past, but those subjects are problematic in today's world. And for some people, a book in which the main characters live off of slavery is too problematic to be read with enjoyment today. I am not going to dispute that. If you don't want to read Huck Finn, or The Merchant of Venice, or Romeo and Juliet or Mansfield Park, I think you are missing out on some great literature, but it's your choice. But, as I said, Kelly is going farther than that.

Kelly is saying, Austen intended for her readers to regard the main characters who get married at the end of the novel -- you know, like people always do at the end of a romantic comedy -- as bad, horrible people. Mansfield Park and Emma may look like romantic comedies on the surface but they are actually condemnations of slavery and the practise of land enclosure.

Kelly is positively allergic to the humour in Austen. Of Knightley and Emma's happy union, Kelly writes, "the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man's terror." In case you don't recognize what she's talking about, it's a reference to this:

Kelly is positively allergic to the humour in Austen. Of Knightley and Emma's happy union, Kelly writes, "the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man's terror." In case you don't recognize what she's talking about, it's a reference to this:Mrs. Weston's poultry-house was robbed one night of all her turkeys--evidently by the ingenuity of man. Other poultry-yards in the neighbourhood also suffered.--Pilfering was housebreaking to Mr. Woodhouse's fears.--He was very uneasy; and but for the sense of his son-in-law's protection, would have been under wretched alarm every night of his life.

Austen treats the theft of the poultry with mock-drama, but of course it's deadly serious to Kelly, a comedy of terrors.

Slavery of course, is not funny. According to Kelly, Mansfield Park is "inescapably political," filled with veiled allusions to slavery which her contemporary readers would have understood. Yes, slavery is mentioned briefly and in passing in the novel and yes, Sir Thomas owns slaves. But that is not what the novel is about. And if some readers think I am making light of the subject of slavery in what follows, no. My intention is to make fun of over-exuberant literary detective work.

Slavery of course, is not funny. According to Kelly, Mansfield Park is "inescapably political," filled with veiled allusions to slavery which her contemporary readers would have understood. Yes, slavery is mentioned briefly and in passing in the novel and yes, Sir Thomas owns slaves. But that is not what the novel is about. And if some readers think I am making light of the subject of slavery in what follows, no. My intention is to make fun of over-exuberant literary detective work.Did you think that when Austen began Mansfield Park with the phrase, "About thirty years ago," her readers would say to themselves, 'Okay, Miss Maria Ward met Sir Thomas Bertram thirty years ago?" No! They would think about slavery!

Her contemporary readers, upon reading the phrase, "About thirty years ago," were supposed to be instantly reminded, and mentally review, the events of the abolition campaign, the Zong case, Cowper's poem, the Haitian slave revolt, all of which transpired during the thirty years before the publication of Mansfield Park. They weren't going to think about Mozart, or how fashions had changed, or how they used to have a full head of hair back then, or how much the pound sterling was worth, or who was on the throne, they were – obviously – going to think about slavery. As you do, you know, whenever someone mentions courtships that occurred in previous decades.

To resume, when Fanny has a headache and Edmund gives her a glass of Madeira wine, what are we supposed to think of? Take a guess. That's right – slavery!

To resume, when Fanny has a headache and Edmund gives her a glass of Madeira wine, what are we supposed to think of? Take a guess. That's right – slavery!Or when Mary Crawford mentions the poet, Hawkins Browne? Well, his son once went to a dinner party with Dr. Johnson and slavery was discussed at that party! And everybody knows about Dr. Johnson. (That much is true, they did).

When young Julia mentions the Roman emperor Severus, what are we supposed to think about? Hint: Severus was an African. Yes, slavery!

No, actually, Severus is mentioned in a passage which is a comedic reference to a common topic of concern at the time -- how to educate girls and how much education girls should have. Instead of didactic passages where the novel's characters sit around and talk about female education, Austen shows, rather than tells, and is poking fun at the same time:

"But, aunt, [Fanny] is really so very ignorant!—… I am sure I should have been ashamed of myself, if I had not known better long before I was so old as she is. ... How long ago it is, aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns!"

"But, aunt, [Fanny] is really so very ignorant!—… I am sure I should have been ashamed of myself, if I had not known better long before I was so old as she is. ... How long ago it is, aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns!""Yes," added [Julia]; "and of the Roman emperors as low as Severus; besides a great deal of the heathen mythology, and all the metals, semi-metals, planets, and distinguished philosophers."

"Very true indeed, my dears, [says Aunt Norris], but you are blessed with wonderful memories, and your poor cousin has probably none at all…. And remember that, if you are ever so forward and clever yourselves, you should always be modest; for, much as you know already, there is a great deal more for you to learn."

"Yes, I know there is, till I am seventeen….."

This is a funny, brilliant passage. Are we also supposed to be thinking about slavery while we are chuckling quietly? Ah yes, we are not supposed to be laughing.

And did you think Mansfield Park ends with a happy couple getting married? No!

And did you think Mansfield Park ends with a happy couple getting married? No!Timid little Fanny "has married a man who doesn't love her, who is a fool and a hypocrite." Austen has not written a hero and heroine who don't appeal to modern tastes, she deliberately wrote unlikeable main characters.

And did you think they will live happily ever after? No! You have forgotten about the apricots!

Here's the final, thunderously condemnatory passage in Kelly's chapter on Mansfield Park:

Thoroughly perfect, though the Moor Park apricot tree is still in the vicarage garden, a reminder of the evil that everyone knows about but no one is willing to discuss, a tree not of knowledge, but of forgetfulness. With every spoonful of apricot jam, every apricot tart that's served up on the parsonage table, Fanny will eat the fruits of slavery.

And the tree will keep on growing.

Why apricots? Because Kelly claims the word "Moor" in "Moor Park" is a subtle reference to slavery that Austen's readers would instantly understand.

"Is Jane really using this name, and this kind of apricot tree, out of all the alternatives, by accident? Is it just coincidence that it's the same word Shakespeare uses to describe the ethnicity of black Africans?"

But of course it's not the same word, it's a homonym. The Moorpark apricot is named after a landed estate called "Moor Park." "Moor" refers not to black people but wild, windswept heaths, moors, like in Wuthering Heights. Please don't tell Kelly about the word 'niggardly,' she'll have conniptions.

Of course, you can't make a good apricot tart without some sugar. Sugar was actually made by slaves, in horrible conditions. That's what they are making at Sir Thomas' plantation in Antigua. Hmm, the word "sugar" does not appear in Mansfield Park. Maybe if Austen had mentioned someone putting sugar in their tea, that would have been a more intelligible reference – to slavery! Easier to "get" than a homonym. But never mind, apricots = slaves.

So what is Mansfield Park, if not a dark, subversive, "deeply troubling," indictment of slavery?

So what is Mansfield Park, if not a dark, subversive, "deeply troubling," indictment of slavery?Mansfield Park, as many critics have knowledgeably explained, is Jane Austen's response to a genre of novel called the "conduct novel." Coelebs in Search of a Wife, a best-selling novel of the day, is a prime example. It features serious discussions of religion, piety, education and choosing a good wife or husband, all issues that are featured in Mansfield Park.

Once you know about conduct novels and what they were like, the style, structure and characters of Mansfield Park makes a lot more sense. Coelebs is a highly didactic book in which the characters sit around and talk. Austen is a better writer, she shows her characters wrestling with moral dilemmas, rather than talk about them.

But I'm not going to digress about that. Here is a link to a fantastic essay on the subject written by someone who possesses more than superficial knowledge about Regency times (women were oppressed back then, did you know?).

May I also recommend David Shapard's foreword in his annotated Mansfield Park. But what about the slaves? Well, for plot purposes, Austen had to have Sir Thomas go away for a long time, and she used the fact that he was on a dangerous sea voyage as one reason why the young people of Mansfield Park should not be amusing themselves with a play while their father was in peril of life or death. At the time of writing, because of the Napoleonic Wars, Sir Thomas couldn't go to Europe, so she had to give him a different destination. Slavery, which in fact is mentioned more explicitly by Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Elton in Emma, than by anyone in Mansfield Park, is simply not at the forefront of the story.

Fanny and her brother One final oddity of Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, on which I'd like to comment, is that Kelly is elaborately cautious about making assumptions where the biographical details of Austen's life are concerned. She refuses to take the widely accepted stories at face value and in fact arrogantly accuses those who came before her of spreading "lies" about Austen. Do we know for a fact that it was First Impressions that her father offered to a publisher? Do we know for a fact that Harris Bigg-Wither proposed to Austen? No, we don't! It's just family "gossip." Did Edward Austen only give Chawton cottage to his mother and sisters because his wife had died and she could no longer object? "an intriguing coincidence, though one about which we can do no more than speculate."

Fanny and her brother One final oddity of Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, on which I'd like to comment, is that Kelly is elaborately cautious about making assumptions where the biographical details of Austen's life are concerned. She refuses to take the widely accepted stories at face value and in fact arrogantly accuses those who came before her of spreading "lies" about Austen. Do we know for a fact that it was First Impressions that her father offered to a publisher? Do we know for a fact that Harris Bigg-Wither proposed to Austen? No, we don't! It's just family "gossip." Did Edward Austen only give Chawton cottage to his mother and sisters because his wife had died and she could no longer object? "an intriguing coincidence, though one about which we can do no more than speculate."But, she makes head-shakingly blithe assumptions from clues that only she can perceive in Austen's text. For example, read this passage:

[Henry Crawford] honoured the warm-hearted, blunt fondness of [Fanny's sailor brother William] which led [William] to say, with his hands stretched towards Fanny's head, 'Do you know, I begin to like that queer fashion already, though when I first heard of such things being done in England, I could not believe it; and when Mrs. Brown, and the other women at the Commissioner's at Gibraltar, appeared in the same trim, I thought they were mad; but Fanny can reconcile me to anything.'

Do you conclude, as does Kelly, that the "the intensity of William's reaction suggests that we are dealing here with cropped hair and not just short front ringlets."?

What? He's a young man saying when he first saw a new hairstyle, he thought it looked silly, but now that he sees it on his beloved sister's head, he is okay with it. What is 'intense' about that? Why does Kelly think hair has been cut, rather than styled? The expression, 'appeared in the same trim,' is a nautical expression. 'Trimming the sails,' does not mean cut the sails, right? It means adjusting them. Or is it the word 'queer'? Please tell me it's not the word 'queer' that has Kelly thinking Fanny is now wearing short hair. And in the end, Kelly does not explain what is so significant about short hair.

Or maybe Harriet Smith is Jane Fairfax's sister because "Hetty" is the name of Jane Fairfax's grandmother. "Nothing in this book remains a mystery if we read it carefully – Harriet Smith and Jane Fairfax may well be half-sisters."

Or maybe Harriet Smith is Jane Fairfax's sister because "Hetty" is the name of Jane Fairfax's grandmother. "Nothing in this book remains a mystery if we read it carefully – Harriet Smith and Jane Fairfax may well be half-sisters."Or maybe they are not. And if they were, why would Austen bury but not reveal the secret in Emma, a book that is filled with hints and clues that are all revealed in the end. What narrative purpose would that serve?

Jane Austen: the Secret Radical is not about Austen's innovations as a writer, her technique, her inimitable voice, her way with dialogue, or her characters. It's about a quest to find certain opinions and points of view embedded deeply within Austen's texts. Kelly has claimed to find these secret opinions, and no doubt she is as well-intentioned as was Emma Woodhouse, when she mistakenly thought she was successfully bringing Harriet Smith and Mr. Elton together. But her inclinations have led her astray and she has found clues that aren't there at all.