Lona Manning's Blog, page 26

November 9, 2020

CMP#12 "Woman Holds a Second Place No More"

Clutching My Pearls is an ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit beliefs in Jane Austen: Englishwomen are better off than other women In my previous post, we looked at how English people of Austen's time viewed their country and their culture in relation to the rest of the world.

Clutching My Pearls is an ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit beliefs in Jane Austen: Englishwomen are better off than other women In my previous post, we looked at how English people of Austen's time viewed their country and their culture in relation to the rest of the world. When we look back to Austen’s time, we see patriarchy embodied in both law and custom. It's routine for modern commentators to emphasize the subordinate legal and social position of women 200 years ago. It's routine for the heroine of a historical romance novel to shake her unruly curls and declare, "I will not be auctioned off like some prize heifer!" while her emerald-green eyes blaze with defiance.

But when we look at what Englishmen and women of Austen’s class said about themselves at the time, when we look at how they compared themselves to other countries and cultures, it is clear that people of her era firmly believed that English gentlewomen were the most privileged women on earth.

Hannah More, in "Essays on Various Subjects" The British wrote in stark terms about the lives of women in other parts of the globe and further, they argued that the subservient role of women went hand-in-hand with the inferiority of that society.

Hannah More, in "Essays on Various Subjects" The British wrote in stark terms about the lives of women in other parts of the globe and further, they argued that the subservient role of women went hand-in-hand with the inferiority of that society. In Africa, women drudged and toiled, doing all the manual labour for the tribe, while the warriors lounged around between battles. Indian widows were burned alive on their husband’s funeral pyres. In the Catholic countries, women were oppressed both by the church and their families.

Mary Wollstonecraft may have been a fierce critic of her own society, but she thought Islamic countries were worse, because she (and others) believed Islam denied that women even had souls.

The popular writer and moralist Hannah More described Englishwomen as emancipated women.

“In this land of civil and religious liberty,” More wrote, “where there is as little despotism exercised over the minds, as over the persons of women, they have every liberty of choice and every opportunity of improvement…”

This confident opinion in the superiority of life for women in England was expressed in books and plays.

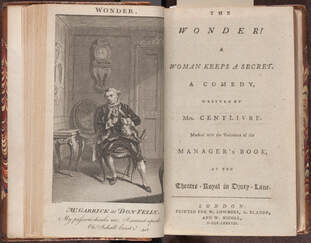

In The Wonder: A Woman Keeps a Secret, a (1714) play by Susanna Centlivre, Portuguese women speak enviously of their English counterparts. “Ah, Inis!” Isabella exclaims to her maid. “What pleasant lives women lead in England, where duty wears no fetter but inclination! The custom of our country enslaves us from our very cradles, first to our parents, next to our husbands, and when Heaven is so kind as to rid us of both these, our brothers still usurp authority and expect a blind obedience from us: so that maids, wives or widows, we are little better than slaves to the tyrant, man.”

In The Wonder: A Woman Keeps a Secret, a (1714) play by Susanna Centlivre, Portuguese women speak enviously of their English counterparts. “Ah, Inis!” Isabella exclaims to her maid. “What pleasant lives women lead in England, where duty wears no fetter but inclination! The custom of our country enslaves us from our very cradles, first to our parents, next to our husbands, and when Heaven is so kind as to rid us of both these, our brothers still usurp authority and expect a blind obedience from us: so that maids, wives or widows, we are little better than slaves to the tyrant, man.”This doesn’t mean that the English believed men and women equal in the sense of being the same. The title of Centlivre’s play is a joke on the idea that women can’t keep a secret—so when one does, it’s a “wonder.” People in Austen’s time believed men and women were different in abilities and preferences, and not simply because society had made them so. Of course they acknowledged that society, education and upbringing had a huge influence. Education for females was a major topic of debate at the time, and it’s a consistent theme in Austen’s novels. But they also believed that certain attributes naturally belonged to men and others belonged to women. Opinions around this are much more confused and confusing today.

Jane Austen’s family used to engage in amateur theatricals when she was a child. The Wonder, or a Woman Keeps a Secret, was performed at her home in Steventon. Austen’s brother James wrote an epilogue for the play, which was performed by the leading lady; their pretty, witty, cousin Eliza de Feuillide, who is thought by many to be an inspiration for Mary Crawford in Mansfield Park.

Eliza Hancock De Feuillide

Eliza Hancock De Feuillide  James Austen, Jane's oldest brother In Barbarous times, e’er learning’s sacred light

James Austen, Jane's oldest brother In Barbarous times, e’er learning’s sacred lightRose to disperse the shades of Gothic night

And bade fair science wide her beams display,

Creation’s fairest part neglected lay....

...Such was poor woman’s lot – whilst tyrant men

At once possessors of the sword and pen

All female claim with stern pedantic pride

To prudence, truth and secrecy denied,

Covered their tyranny with specious words

And called themselves creation’s mighty lords –

But thank our happier Stars, those times are o’er;

And woman holds a second place no more.

Now forced to quit their long held usurpation,

Men all wise, these ‘Lords of the Creation’!

To our superior sway themselves submit,

Slaves to our charms, and vassals to our wit;

We can with ease their ev’ry sense beguile,

And melt their Resolutions with a smile. Imagine the vivacious Eliza de Feuillide, speaking the words penned for her by James Austen, (who was in love with her.) And imagine young Jane watching everything.

James' message is that Mankind has arisen, through the aid of Science, from a past barbarous age. In the distant past, when men were savage warriors, they could not even appreciate the virtues or talents of women. And women were long denied education because men possessed the sword and the pen. He finishes with a flourish of gallantry toward lovely womankind reminiscent of Mr. Elton's charade. Man's boasted power and freedom, all are flown/Lord of the earth and sea, he bends a slave, /And woman, lovely woman, reigns alone.

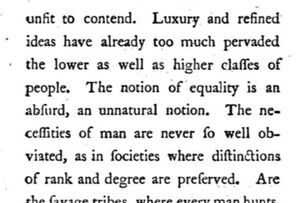

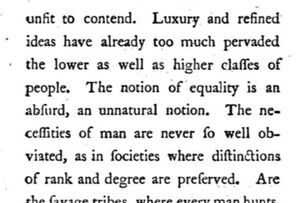

I haven’t made a survey of all eighteenth-century literature, so it’s presumptuous of me to connect the dots here, but James Austen's ideas exactly coincide with the explanation of social history given in Lord Kames’ influential book, Sketches of the History of Man (1774). Below is a sample. I imagine that some people today are reduced to a state of spluttering rage when they read Lord Kame but these were the views of educated people in Jane Austen's time. Lord Kame also criticized the restricted life led by women in Asia, and says their education gave them "no improvement of the rational faculties."

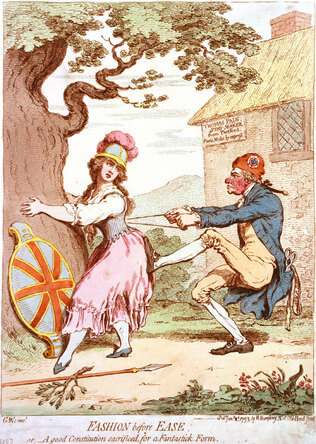

Lord Kame on the inferior position of women in aboriginal societies In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen breaks the fourth wall with her famous (and famously acidic) remarks about men preferring stupid women, writing "In justice to men... there is a portion of them too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance." However, this says more about Austen's opinion of most men than it does her opinion of women. Mr. Darcy, of course, says that an accomplished woman (though denied the opportunity to attend Cambridge or Oxford, of course) improves her mind with extensive reading.

Lord Kame on the inferior position of women in aboriginal societies In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen breaks the fourth wall with her famous (and famously acidic) remarks about men preferring stupid women, writing "In justice to men... there is a portion of them too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance." However, this says more about Austen's opinion of most men than it does her opinion of women. Mr. Darcy, of course, says that an accomplished woman (though denied the opportunity to attend Cambridge or Oxford, of course) improves her mind with extensive reading.

“The Comforts of Matrimony — A Smoky House and Scolding Wife,” 1790. Austen clearly believes that women are rational creatures, capable of thought, capable of receiving an education. Women are called upon to act morally, which means she believes that women have moral agency.

“The Comforts of Matrimony — A Smoky House and Scolding Wife,” 1790. Austen clearly believes that women are rational creatures, capable of thought, capable of receiving an education. Women are called upon to act morally, which means she believes that women have moral agency. "Rational" is a term of high praise in Austen. Mr. Knightley says Emma's governess, "a rational, unaffected woman," didn't need Emma's interference in her love life. After Robert Martin consults him about marrying Harriet Smith, he remarks to Emma, "as to a rational companion or useful helpmate, he could not do worse." When Harriet attempts to get over her crush on Mr. Elton, she asks Emma to witness "how rational [she had] grown."

Likewise, to be "irrational" is a strong term of disapproval. When Emma realizes how deluded she's been, she scolds herself, "How inconsiderate, how indelicate, how irrational, how unfeeling had been her conduct!"

In Pride & Prejudice, Elizabeth begs Mr. Collins to see her as "rational creature" when she turns down his proposal. Mr. Bennet tells Kitty she can't go out until she's spent at least ten minutes a day in a rational manner.

Austen also describes her most likeable characters as "sensible." The late Lady Elliot and her friend Lady Russell are sensible, so of course is Charlotte Lucas. Marianne Dashwood is "sensible and clever."

With the exception of Catherine Morland --Henry Tilney loves the "excellencies of her character"-- Austen's heroines are sensible, rational creatures and the men who love them respect their intelligence.

There's more to be said about women's inferior position in England, and whether Jane Austen has secret messages in her novels concerning this issue but for now, we should understand that it is a distortion of history to suppose that all Englishwomen saw themselves as miserably oppressed, or that the men of her time really preferred imbeciles for wives. The reality is more nuanced.

Next post: A state of utter barbarism.

In my book, A Marriage of Attachment, a woman is terrified that her husband will take her wages, which he is entitled to by law, but which she needs to support their children. For more about my novels, click here.

Published on November 09, 2020 00:00

November 5, 2020

CMP#11 Better to be English

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction to the series. Implicit values in Austen: Better to be English

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction to the series. Implicit values in Austen: Better to be English

"It was a sweet view—sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright, without being oppressive." So says Jane Austen of the view from Donwell Abbey in Emma. Jane Austen was proud of her country and proud of being English. English law was superior. English manners and customs were on the whole superior to other nations.

"It was a sweet view—sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright, without being oppressive." So says Jane Austen of the view from Donwell Abbey in Emma. Jane Austen was proud of her country and proud of being English. English law was superior. English manners and customs were on the whole superior to other nations. When Catherine Morland talks herself down from her Gothic fantasies in Northanger Abbey, she recalls what Henry Tilney told her: "Remember, we are English." Austen's narrative voice adds, (in phrases a bit wittier than we would expect to find in Catherine's interior monologue): "But in the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves, and neither poison nor sleeping potions to be procured, like rhubarb, from every druggist." Yes, the Hanoverian royal family was nothing to boast about. Austen hated Prince George, appointed Regent of England during his father's mental illness. But as she looked around the globe, no other kingdom compared to England.

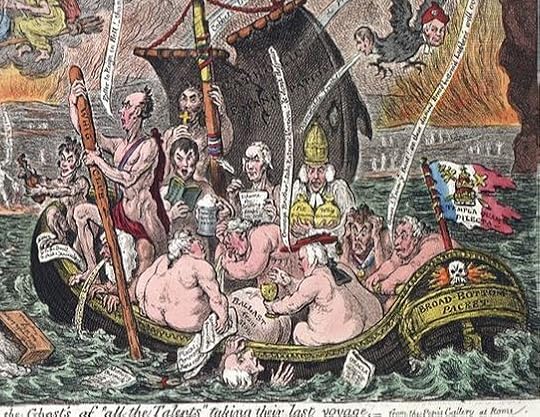

And England stood alone against Napoleon for most of her adult life. When your country is under threat, when the other countries of Europe have been subjugated by a conqueror and you are fighting on, this would tend to increase your own patriotic zeal.

A scene from "The Monk" Joan Austen-Leigh quotes two samples of her letters to show Austen's cheerful English chauvinism: Jane writes to Cassandra, “We found Edward [Lefroy] very agreeable. He is come back from France, thinking of the French as one could wish, disappointed in everything.” And to Alethea Bigg: “I hope your letters from abroad are satisfactory. They would not be satisfactory to me, I confess, unless they breathed a strong spirit of regret for not being in England.”

A scene from "The Monk" Joan Austen-Leigh quotes two samples of her letters to show Austen's cheerful English chauvinism: Jane writes to Cassandra, “We found Edward [Lefroy] very agreeable. He is come back from France, thinking of the French as one could wish, disappointed in everything.” And to Alethea Bigg: “I hope your letters from abroad are satisfactory. They would not be satisfactory to me, I confess, unless they breathed a strong spirit of regret for not being in England.” England was the centre of the universe, not just for Austen but for all her characters. When Elizabeth, or Elinor, or Emma, or Anne, refers to "everybody" or "people" as in "society," as in "what will people think," the term they use is "the world." England is the world, and more specifically, the stratum of society in which reputation and honour and decorum matters, is "the world." The rest is unimportant.

"The world" is mentioned in Pride & Prejudice 63 times, 78 in Emma. Some examples:"He was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world.""...you have been the principal, if not the only means of dividing them from each other—of exposing one to the censure of the world for caprice and instability, and the other to its derision for disappointed hopes...” Of course, many people used the phrase. It was a common expression: "The world will little note or long remember..." said LIncoln at Gettysburg. But there, he is referring to posterity, not Mrs. Grundy.

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks, John Millar During Austen's lifetime, the English could not travel outside of the kingdom, unless they made the long trek to America, or to India or China. Europe was pretty much out of bounds, because of the long-running wars with France. Naturally, educated Englishmen were curious about life in other countries and they enjoyed armchair travelling.

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks, John Millar During Austen's lifetime, the English could not travel outside of the kingdom, unless they made the long trek to America, or to India or China. Europe was pretty much out of bounds, because of the long-running wars with France. Naturally, educated Englishmen were curious about life in other countries and they enjoyed armchair travelling. The craze for Gothic novels was at also its height at this time--escapist literature about exotic landscapes and passionate foreigners, including wicked (Catholic) abbots and nuns.

In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price retreats to the East Room to read Lord McCartney's account of his embassy to China.

That the people in one country were different than the people in another country, and that England was the best of countries, was a self-evident proposition in Austen's time. People in different countries were also different in manners, customs, laws, habits. ("Manners" had a broader application than what we mean by "good manners" today) Mary Crawford tells her sister that she has "the address of a Frenchwoman" if she can persuade brother Henry to get married.

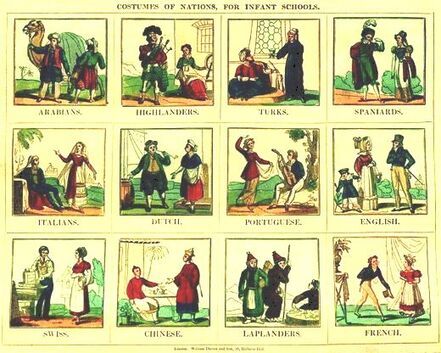

Illustrations in a children's schoolbook And if cultures were different, it also followed that they could be compared, ranked, praised, criticized. The Chinese were industrious, the French frivolous. Anybody could see this, anybody could say so.

Illustrations in a children's schoolbook And if cultures were different, it also followed that they could be compared, ranked, praised, criticized. The Chinese were industrious, the French frivolous. Anybody could see this, anybody could say so. And there was as well--naturally enough-- speculation about the causes of the differences between different nations and different parts of the globe. The people who lived in the warmer Mediterranean countries were more slothful and indolent than people in England.

There was a genuine curiosity to figure out how the world worked, to understand how and why societies organized themselves so differently around the globe. Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776 - 1788) was an exploration of how a mighty empire fell.

The Origin of the Distinction of Ranks by John Millar (1778) discussed how societies progressed from hunter-gatherer, to agricultural, and so on; how trade arose and how these economic innovations affected human relations in society at large. That is, these proto-anthropologists made connections between social organization, culture, and technological advancement. Just as it was indubitable that many empires had risen and fallen, it was also indubitable that there was such a thing as progress.

Sketches of the History of Man (1774) by Lord Kame compared the industry, the habits, even the cleanliness, of different nations and tribes. Lord Kame does not hesitate to pronounce that the Japanese were cleaner even than the Dutch, while the Tartars were crawling with vermin.

Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations (1776), compared and analyzed the industry and trade arrangements of different nations.

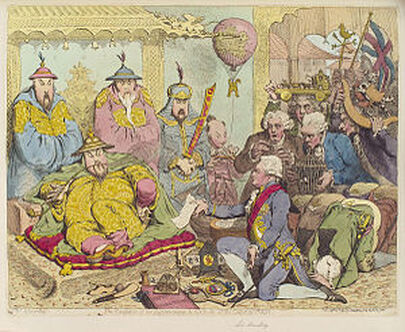

Lord McCartney's reception in Beijing Despite what we are told about Westerners always looking down on other nations, British travelers abroad sometimes praised what they saw. A diplomat reporting on Lord McCartney's voyage admits: "However much Europeans may plume themselves on their superior knowledge of agriculture, gardening, and ornamental design, the Chinese, in most respects, would bear away the palm."

Lord McCartney's reception in Beijing Despite what we are told about Westerners always looking down on other nations, British travelers abroad sometimes praised what they saw. A diplomat reporting on Lord McCartney's voyage admits: "However much Europeans may plume themselves on their superior knowledge of agriculture, gardening, and ornamental design, the Chinese, in most respects, would bear away the palm." This same writer was surprised to see women in the streets in Beijing. "An opinion has prevailed in Europe, that Chinese woman live secluded from view. The fact is otherwise... amid the immense concourse that were assembled to view our procession, perhaps there were more women in proportion than we should have seen in any principal town in Europe." These were probably Manchu women an ethnic group which had conquered the Han majority. Manchu women did not practice foot-binding, either.

In How To Be An AntiRacist, best-selling author Ibram X. Kendi approvingly quotes the anthropologist Ashley Montagu, "All cultures must be judged in relation to their own history, and all individuals and groups in relation to their cultural history, and definitely not by the arbitrary standard of any single culture.”

In How To Be An AntiRacist, best-selling author Ibram X. Kendi approvingly quotes the anthropologist Ashley Montagu, "All cultures must be judged in relation to their own history, and all individuals and groups in relation to their cultural history, and definitely not by the arbitrary standard of any single culture.” Kendi goes on to add, "To be antiracist is to see all cultures in all their differences as on the same level, as equals. When we see cultural difference, we are seeing cultural difference—nothing more, nothing less.”

But Montague's statement differs significantly from Kendi's. Montagu says cultures can be evaluated and compared, so long as we aware of our cultural blinders. Kendi explicitly removes the possibility of holding up aspects of one culture as better or worse than another. He also conflates culture with race.

Does Kendi really see all cultures "on the same level, as equals"? Does anyone? As regards what aspects? In their social organization? In their ability to provide the necessities of life? In their technological capacity? In their tolerance for non-members? Jane Austen would not have thought this way. She would not have seen any benefit to thinking this way, either.

Jane Austen was pro-British. Does that make her a bigot? This is a painful question for some people. I for one regard Austen as a clever and well-educated woman of her time and place, who shared in the opinions of her time and place. She believed that her culture, with its written language, legal codes, specialized trades and division of labour, its educational and charitable institutions, was not merely different from, say, a nomadic tribe in the desert--it was better, and that people who lived there, even the lower classes, were lucky to be born British.

I don't feel obligated to do any special pleading for her, or grope to find a benign interpretation for Darcy's remark that every savage can dance. Next post: Woman, lovely woman, reigns alone

In my Mansfield Trilogy, Mary Crawford is eager to go abroad once peace is declared, and like many other Englishmen and women, she goes to Italy. There she meets Percy Bysshe Shelley, who is contemptuous of the Italians because in his mind they do not measure up to their fore bearers, the Romans. I also tell this story as a stand-alone novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady.

Published on November 05, 2020 00:00

November 2, 2020

CMP#10 "Where the clergy are what they ought to be"

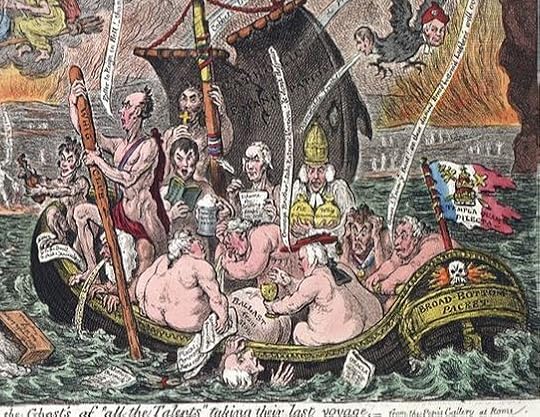

Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is an ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Jane Austen: "As the clergy are... so are the rest of the nation" In the previous post, I looked at how Jane Austen handles religion in her novels. Some scholars have pointed to Austen's foolish clergyman (Mr. Collins and Mr. Elton) as evidence that Austen didn't like clergymen, or was critical of the Church of England. Was it dangerous to be critical of the clergy? Was it a radical position to take?

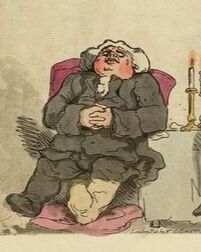

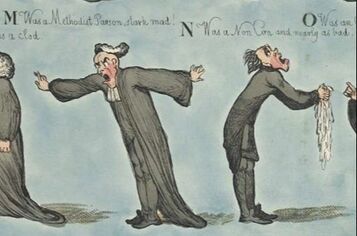

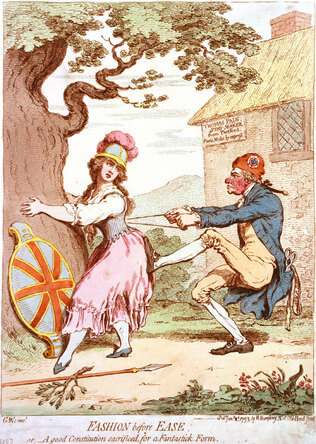

Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is an ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Jane Austen: "As the clergy are... so are the rest of the nation" In the previous post, I looked at how Jane Austen handles religion in her novels. Some scholars have pointed to Austen's foolish clergyman (Mr. Collins and Mr. Elton) as evidence that Austen didn't like clergymen, or was critical of the Church of England. Was it dangerous to be critical of the clergy? Was it a radical position to take?The cartoon below, showing a clergymen enjoying an after-dinner snooze, suggests that it was acceptable to poke fun at clergymen, within certain limits. A copy of this print was purchased by the Prince of Wales. (The vicar's foot is bandaged and resting on a pillow because he's suffering from gout caused by his over-rich diet.)

A Vicar, detail of Rowlandson cartoon, 1785 There are several discussions about clergymen in Mansfield Park (in addition to conversations about church services in general) which might yield a clue as to Austen's true opinions. The arguments against clergymen are voiced by Mary Crawford--the worldly, cynical girl from London--and the arguments in favour are put forward by Edmund Bertram, who is the hero of the novel (though many readers think he's a prig and a bore.)

A Vicar, detail of Rowlandson cartoon, 1785 There are several discussions about clergymen in Mansfield Park (in addition to conversations about church services in general) which might yield a clue as to Austen's true opinions. The arguments against clergymen are voiced by Mary Crawford--the worldly, cynical girl from London--and the arguments in favour are put forward by Edmund Bertram, who is the hero of the novel (though many readers think he's a prig and a bore.)Edmund calls Mary Crawford's criticisms of the clergy "commonplace," which suggests that it was not at all unusual in Austen's time to hear the opinions that she mentions. Even so, I was surprised to find, in the memoirs of Henry Hunt, the exact same points Mary Crawford makes. I am not suggesting Hunt cribbed his dialogue out of Mansfield Park. I think the resemblance shows how commonplace the censures were.

Henry Hunt was a radical politician, sent to prison after being convicted of seditious conspiracy. He published his memoirs from prison in 1820. Just as Jane Austen puts the anti-clergy arguments into the mouth of Mary Crawford, Hunt's vehicle is his father, who appears to have been a rustic country squire, perhaps something like the older Mr. Musgrove in Persuasion.

The first charge against the clergy is lack of ambition and laziness. Mary Crawford complains, “It is indolence, Mr. Bertram, indeed. Indolence and love of ease; a want of all laudable ambition, of taste for good company, or of inclination to take the trouble of being agreeable, which make men clergymen. A clergyman has nothing to do but be slovenly and selfish—read the newspaper, watch the weather, and quarrel with his wife. His curate does all the work, and the business of his own life is to dine.”

Hugh Blair, 1718 - 1800, Scottish minister and author of popular sermons Similarly, Henry Hunt's father--evidently to test his character--offers to buy him a living, and tells him, "you will have nothing else to do, for six days out of the seven, but hunt, shoot, and fish by day, and play cards and win the money of the farmer's wives and children by night.." Edmund Bertram answers Mary: “There are such clergymen, no doubt, but I think they are not so common as to justify Miss Crawford in esteeming it their general character. I suspect that in this comprehensive and (may I say) commonplace censure, you are not judging from yourself, but from prejudiced persons, whose opinions you have been in the habit of hearing."

Hugh Blair, 1718 - 1800, Scottish minister and author of popular sermons Similarly, Henry Hunt's father--evidently to test his character--offers to buy him a living, and tells him, "you will have nothing else to do, for six days out of the seven, but hunt, shoot, and fish by day, and play cards and win the money of the farmer's wives and children by night.." Edmund Bertram answers Mary: “There are such clergymen, no doubt, but I think they are not so common as to justify Miss Crawford in esteeming it their general character. I suspect that in this comprehensive and (may I say) commonplace censure, you are not judging from yourself, but from prejudiced persons, whose opinions you have been in the habit of hearing."While Henry Hunt's mother tells her husband, "[R]eally my dear, although there is too much truth in the picture you have drawn, yet you have been a little too severe upon the clergy, when speaking of them in the mass. There are many excellent and worthy men, who follow the precepts of their great master, who are an ornament to that society to which they belong... [and] do great credit to the profession..."

"Do not tell me about ornaments to society," the father replies, "the best of them are drones of society [because]... they feed upon the choicest honey, collected by the labour of the industrious bees..."

This part about the bees and honey is a reference to tithes. Clergymen were usually supported by taking a percentage (traditionally ten percent) of the food and other manufactures of the parish, known as tithes.

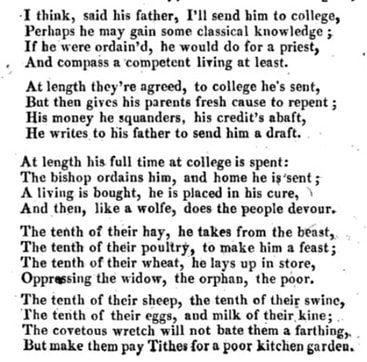

from "Tithes Abolished and Priestcraft Detected" There was, naturally enough, a lot of resentment about tithes, as it involved declaring all the produce of your farms and fields.

from "Tithes Abolished and Priestcraft Detected" There was, naturally enough, a lot of resentment about tithes, as it involved declaring all the produce of your farms and fields.An angry manifesto titled "Tithes Abolished and Priestcraft Detected," (1814, the same year as Mansfield Park) inveighed against tithes and also against dissolute and lazy clergymen. The author, Edward Tovey, who appears to have been a fire-and-brimstone Evangelical, attacked the system of selecting clergymen, because young men with absolutely no vocation for the church could get a degree and then be ordained.

In the poem excerpted at left, the parents of a wild and not-very-bright child are at a loss how to train him for a profession, and decide to set up him as a clergyman. Once ordained, he oppresses his flock with his demands for tithes. I have not been able to discover if Tovey's call to overthrow the entire system of the Church of England got him into trouble with the authorities. Tovey's book goes much farther than Henry Hunt-- and Hunt was able to publish his memoir from prison. Hunt goes farther than Jane Austen. Her portrait of the self-important, fawning Mr. Collins is nothing like what Tovey or Hunt have to say about the clergy. The excellence of her writing, her genius at creating comic characters, means we know about Mr. Collins and Mary Crawford today, while few people know about Hunt and Tovey.

What is noteworthy is that Mary Crawford--who represents the point of view of a worldly cynic--makes the same criticisms as a country squire (Henry Hunt's father) and an evangelical like Edward Tovey. These censures of the clergy were commonplace, indeed. There was obviously an ongoing social debate about tithes, pluralism (the practice of holding more than one living), absentee clergymen, incompetent clergymen, and so forth. Participating in that conversation did not mark you out as radical.

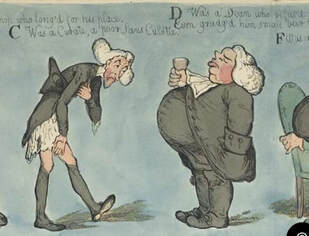

The starving, downtrodden curate works for the selfish clergymen in "A Clerical Alphabet." Another criticism is that clergymen didn't even exert themselves to write their own sermons. "Supposing the preacher to have the sense to prefer Blair's to his own," Mary quips, a reference to Hugh Blair, whose sermons were very popular.

The starving, downtrodden curate works for the selfish clergymen in "A Clerical Alphabet." Another criticism is that clergymen didn't even exert themselves to write their own sermons. "Supposing the preacher to have the sense to prefer Blair's to his own," Mary quips, a reference to Hugh Blair, whose sermons were very popular. Henry Hunt's father tells him, "All that will be expected of you is to read prayers, and preach a sermon, which will cost you three pence a week." Edward Tovey also accuses the clergymen of buying his sermons "at twice ten pence a score."

Many clergymen left the sermonizing to their curates, a subordinate who was typically paid a pittance out of the income of the parish. In Sense & Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings exclaims "Then, Lord help 'em! how poor they will be!" when she thinks Edward Ferrars will marry on a curate's salary.

A detail from "A Clerical Alphabet." showing a greedy clergymen with his tithes. Click on the photo to see the complete cartoon. In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford assumes Edmund will install a curate in the nearby village of Thornton Lacey and be an absentee clergymen. "He will have a very pretty income to make ducks and drakes with, and earned without much trouble. I apprehend he will not have less than seven hundred a year... and as of course he will still live at home, it will be all for his menus plaisirs; and a sermon at Christmas and Easter, I suppose, will be the sum total of sacrifice.”

A detail from "A Clerical Alphabet." showing a greedy clergymen with his tithes. Click on the photo to see the complete cartoon. In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford assumes Edmund will install a curate in the nearby village of Thornton Lacey and be an absentee clergymen. "He will have a very pretty income to make ducks and drakes with, and earned without much trouble. I apprehend he will not have less than seven hundred a year... and as of course he will still live at home, it will be all for his menus plaisirs; and a sermon at Christmas and Easter, I suppose, will be the sum total of sacrifice.”Henry's brother-in-law Dr. Grant, also a clergyman, talks to Edmund about “how to make money; how to turn a good income into a better." Dr. Grant is giving Edmund tips about the living he is about to step into; in other words, how to collect the tithes and improve the yield of his own acreage.

Well, if tithes are all right with Edmund, they are all right with Fanny, our heroine. And Jane Austen, as we recall, laughed at the suggestion that she should include the abolition of tithes in one of her novels and wrote a little satire about it. We might also recollect this is how her father, whom she loved and respected, supported his family.

We might also recollect that in Protestantism, a clergyman is not to be regarded as infallible. The individual has their own relationship with God. As Fanny Price says, with typical Austenian euphemism, "We have all a better guide in ourselves, if we would attend to it, than any other person can be."

The Church of England denied the Methodist minister John Wesley a pulpit, so he preached in the open air. Mary Crawford's chief objection to Edmund's becoming a clergymen, of course, is that she wants to marry someone who will cut a dash in society. "A clergyman is nothing," she tells him. Henry Hunt's father says the same: "If you have any ambition to be a shining character in the world, that is the very last profession I would recommend."

The Church of England denied the Methodist minister John Wesley a pulpit, so he preached in the open air. Mary Crawford's chief objection to Edmund's becoming a clergymen, of course, is that she wants to marry someone who will cut a dash in society. "A clergyman is nothing," she tells him. Henry Hunt's father says the same: "If you have any ambition to be a shining character in the world, that is the very last profession I would recommend." Edmund answers, "A clergyman cannot be high in state or fashion. He must not head mobs, or set the ton in dress." And he makes the same point that Mr. Hunt's mother makes--a clergyman has the power of doing good. In fact, Edmund goes much farther: "But I cannot call that situation nothing which has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally, which has the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence."

From this speech, Mary should have understood that Edmund actually believed in the doctrines he was speaking of. Despite his use of euphemisms, he took his faith seriously.

And so, I would suggest, did Jane Austen. Some clergymen might fall short of what they should be, but Austen was more apt to criticize clergymen as individuals, rather than inveigh against the system as a whole. She also shows us good clergymen. (I will get into the issue of whether Edmund Bertram is a good clergyman and a worthy hero, another day.) We don't meet Captain Wentworth's clergyman brother in Persuasion but were are told he reacted charitably when a "farmer's man" (a labourer) broke "into his orchard; wall torn down; apples stolen; caught in the fact" and declined to prosecute. He "submitted to an amicable compromise."

Further reading When Mary says, "a clergyman is nothing," she is referring to his status in society. There is no "heroism, danger, bustle, fashion" in being a clergyman, as opposed to being a soldier or a sailor. It's an unmistakable sign (well, unmistakable to everyone but Edmund, that is) of Mary's utter worldliness. She is entirely unsuited to become a clergyman's wife. She also denies that the clergy can really have much effect on public morals--how much good can a few sermons do, especially when contrasted with the actual behaviour of clergymen who do not practice what they preach?

Further reading When Mary says, "a clergyman is nothing," she is referring to his status in society. There is no "heroism, danger, bustle, fashion" in being a clergyman, as opposed to being a soldier or a sailor. It's an unmistakable sign (well, unmistakable to everyone but Edmund, that is) of Mary's utter worldliness. She is entirely unsuited to become a clergyman's wife. She also denies that the clergy can really have much effect on public morals--how much good can a few sermons do, especially when contrasted with the actual behaviour of clergymen who do not practice what they preach? Edmund replies with the "respect the office, not the person," argument. "No one here can call the office nothing... The manners I speak of might rather be called conduct, perhaps, the result of good principles; the effect, in short, of those doctrines which it is [the clergymen's] duty to teach and recommend; and it will, I believe, be everywhere found, that as the clergy are, or are not what they ought to be, so are the rest of the nation.”

Next post: Rule Britannia Dissenting Protestants like the Quakers were at the forefront of the campaign to end the slave trade. In my Mansfield Trilogy, Mrs. Butters, the widow of a shipbuilder who made ships for the slave trade, gives much of her fortune to the abolition campaign. Click here for more about my books.

Published on November 02, 2020 00:00

October 26, 2020

CMP#9 Decorum in Religious Matters

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. When I say "my take," I very much doubt that I could find anything new or different to say about Austen, not after her admirers have written so much. But I am not trying to be new, rather I am pushing back at post-modern portrayals of Austen as a radical feminist. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Decorum in Religious Matters

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. When I say "my take," I very much doubt that I could find anything new or different to say about Austen, not after her admirers have written so much. But I am not trying to be new, rather I am pushing back at post-modern portrayals of Austen as a radical feminist. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Decorum in Religious Matters

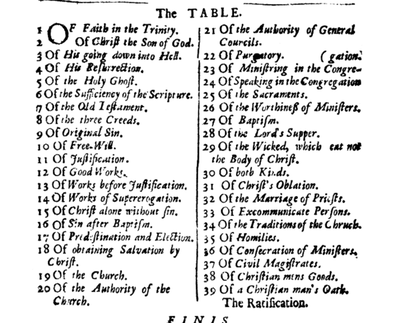

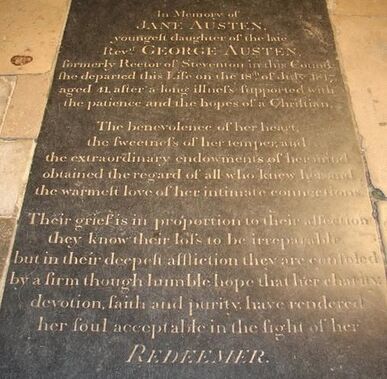

The Thirty-Nine Articles People who write about Austen are not very pleased with her first two biographers--her brother Henry and her nephew James Austen-Leigh. Along with Austen's sister Cassandra, they stand accused of obscuring the real Jane Austen. Cassandra destroyed most of Austen's letters, and Henry and Austen-Leigh portrayed her as a retiring spinster who did not live a "life of event." Her gravestone proclaims "the sweetness of her temper." Really? Jane Austen, who wrote with a quill dipped in vinegar?

The Thirty-Nine Articles People who write about Austen are not very pleased with her first two biographers--her brother Henry and her nephew James Austen-Leigh. Along with Austen's sister Cassandra, they stand accused of obscuring the real Jane Austen. Cassandra destroyed most of Austen's letters, and Henry and Austen-Leigh portrayed her as a retiring spinster who did not live a "life of event." Her gravestone proclaims "the sweetness of her temper." Really? Jane Austen, who wrote with a quill dipped in vinegar?The family biographers and the gravestone also emphasize her Christian faith. Henry, who became a clergyman himself, wrote that “her opinions accorded strictly with those of our Established Church."

Dr. Helena Kelly, however, knows better. In Jane Austen: The Secret Radical, she writes: "What we can say, with confidence, is that [Austen]'s opinion didn't really accord anything like as strictly 'with those of our Established Church,' as Henry claims." For one thing, Austen is "scornful" of the clergy. (Kelly includes Edward Ferrars and Edmund Bertram along with Mr. Collins and Mr. Elton in her list of bad clergymen.)

As it happens, Edmund Bertram and Mary Crawford actually discuss whether clergyman are good people in Mansfield Park. I explore that discussion in the next post. For now, consider the fact that showing unquestioning reverence to clergymen is not required in the Church of England. The 39 Articles, a list of official church doctrines, includes article 26, which acknowledges that some clergymen are unworthy of their calling, but this does not affect the truth of the sacraments.

Mr. Bennet scoffs at Mr. Collins when he writes to advise him to never let Lydia darken his door again: He reads a portion of Collins letter: ""You ought certainly to forgive them, as a Christian, but never to admit them in your sight, or allow their names to be mentioned in your hearing." Then adds, "That is his notion of Christian forgiveness!"

Mr. Collin's take does not shake Mr. Bennet's understanding of what Christian forgiveness is.

If Henry Austen is correct, if his sister's beliefs accorded "strictly with those of our Established Church," then she subscribed to the 39 articles. For example, article 19 states that "the Church of England is the one true Church, and its teachings are necessary for salvation," which has implications when we come to talk about savages and heathens down the line.

I think Paula Byrne's biography Jane Austen, a Life in Small Things, makes a convincing case that Austen was a devout Anglican because it draws on examples from her private correspondence. Byrne mentions a letter Austen wrote to her sister, concerning a local woman who had run away with a lover. Austen comments that the Sunday before the woman eloped, she "staid the Sacrament," that is, she took Holy Communion at church.

This looks like a reference to Article 29: "The Wicked who Partake of the Last Supper Do Not Eat the Body of Christ." Mrs. Powlett was unfaithful to her husband and was planning to leave him when she took her wafer and wine.

Austen distinguishes between actually calling upon one's Creator ("Oh God, her father and mother!") and profane cursing. When Fanny Price's father says, "by God," Austen spells it "by G—!" Article 39 of the 39 Articles specifies no "rash swearing."

Mrs. Musgrove weeps for poor Dick But if Austen was devout, why is she so reticent about her Christian faith in her writing? In my first readings of Austen, I came to notice that nobody seems to be very religious. Not even the clergymen, especially not Henry Tilney. Austen's characters sometimes mention God, but she doesn't use the words "Jesus," "Messiah," or "Redeemer" in any of her novels. And as someone (I forget who) pointed out, when her heroines are facing a crisis, they retire to their bedchambers to think, they don't go consult their clergyman or go to a chapel to pray. And apart from references to "Christian names," Austen seldom mentions Christianity.

Mrs. Musgrove weeps for poor Dick But if Austen was devout, why is she so reticent about her Christian faith in her writing? In my first readings of Austen, I came to notice that nobody seems to be very religious. Not even the clergymen, especially not Henry Tilney. Austen's characters sometimes mention God, but she doesn't use the words "Jesus," "Messiah," or "Redeemer" in any of her novels. And as someone (I forget who) pointed out, when her heroines are facing a crisis, they retire to their bedchambers to think, they don't go consult their clergyman or go to a chapel to pray. And apart from references to "Christian names," Austen seldom mentions Christianity. Austen's characters refer to divine intervention in human affairs by using using the terms "Providence" and "providential" or "Heaven." (This is by no means unique to Austen, however, many people did the same.)

When Edmund Bertram finally (!) realizes what a cad Henry Crawford is, he is relieved to know that Fanny Price did not fall for him. “Thank God,” said he. “We were all disposed to wonder, but it seems to have been the merciful appointment of Providence that the heart which knew no guile should not suffer."

Mrs. Musgrove sighs, "Ah! Miss Anne, if it had pleased Heaven to spare my poor son, I dare say he would have been just such another [as Captain Wentworth] by this time."

When Mary Musgrove discovers that the stranger who just left the inn at Lyme is her cousin, Captain Wentworth flippantly says: "Putting all these very extraordinary circumstances together, we must consider it to be the arrangement of Providence, that you should not be introduced to your cousin."

When Louisa Musgrove survives the fall from the Cobb, "the rejoicing, deep and silent, after a few fervent ejaculations of gratitude to Heaven had been offered, may be conceived."

God (usually as in "Thank God" and "Oh, God!") is mentioned nine times in Persuasion, five times in Pride & Prejudice, three times in Mansfield Park, and so forth. Mrs. Bennet and Lydia are apt to exclaim, "Good Lord!" and "O, Lord!"

Dr. Johnson (1709 -- 1784) Austen's favourite prose writer was Dr. Samuel Johnson, a figure so well known in English literature that he is referred to as "the Doctor." Johnson was a devout Anglican who took a rational approach to religion. That is, he believed there was abundant evidence for the truth of the Gospels and that Christianity appealed to logic as well as emotion.

Dr. Johnson (1709 -- 1784) Austen's favourite prose writer was Dr. Samuel Johnson, a figure so well known in English literature that he is referred to as "the Doctor." Johnson was a devout Anglican who took a rational approach to religion. That is, he believed there was abundant evidence for the truth of the Gospels and that Christianity appealed to logic as well as emotion.Scholar Lance Wilcox says of Johnson: "He presents the Church of England as a bulwark against 'infidelity, superstition, and enthusiasm': eighteenth-century code words for deism, Catholicism, and dissenting Protestantism, respectively."

So Austen's favourite prose author was opposed to dissenters, those who worshipped independently of the official state church. He was not alone. In The Club, a joint biography of Dr. Johnson, Boswell, and other men in their circle in 18th century London, historian Leo Damrosch explains, "Throughout the seventeenth century it was taken for granted that religious commitment depended upon faith, an interior conviction of divinely revealed truth. But in the eighteenth century that premise seemed increasingly suspect to many people, because it smacked of the 'enthusiasm' --from a Greek word meaning 'possessed by a god' -- that had energized the Puritan revolution and turned Britain upside down.' The Puritans, we remember, executed King Charles the First and established a Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. Life in Britain at under Cromwell was rather like living under the Taliban. People must have wondered if no music, no fashion, no sports, no Christmas, no theatre, no pubs, was really what God wanted for His people.

The Republic was overthrown and the Monarchy was restored in 1660, but civil wars are not easily forgotten and people remained suspicious of religious zeal.

Detail of "A Clerical Alphabet" (1795) with a Methodist Parson "stark mad!" and a Non-conformist Minister, "nearly as bad" A new evangelical movement arose in Austen's lifetime, one which appeared to threaten the absolute authority of the Church of England. Some famous evangelicals include William Wilberforce, the abolitionist, and Hannah More, a very successful writer, (although Wilberforce and More were Anglicans).

Detail of "A Clerical Alphabet" (1795) with a Methodist Parson "stark mad!" and a Non-conformist Minister, "nearly as bad" A new evangelical movement arose in Austen's lifetime, one which appeared to threaten the absolute authority of the Church of England. Some famous evangelicals include William Wilberforce, the abolitionist, and Hannah More, a very successful writer, (although Wilberforce and More were Anglicans).Then there were the dissenting ministers, such as the raving Methodist minister and the non-conformist minister in the "Clerical Alphabet." [Click on the picture to see the entire alphabet which makes fun of Anglican clergymen of all ranks as well.]

Hannah More 1745 - 1833 Hannah More saw nothing wrong with displaying religious zeal: "I am at a loss to know why a young female is instructed to exhibit… her skill in music, her singing, dancing, [and her] taste in dress… while her piety is to be anxiously concealed and her knowledge affectedly disavowed, lest the former should draw on her the appellation of an enthusiast, or the latter that of a pedant.”

Hannah More 1745 - 1833 Hannah More saw nothing wrong with displaying religious zeal: "I am at a loss to know why a young female is instructed to exhibit… her skill in music, her singing, dancing, [and her] taste in dress… while her piety is to be anxiously concealed and her knowledge affectedly disavowed, lest the former should draw on her the appellation of an enthusiast, or the latter that of a pedant.”In respect of female knowledge, at least, we know that More and Austen saw eye to eye! But recall the explanation about the meaning of "enthusiasm." Hannah More is saying that openly pious women were thought of as enthusiasts, and enthusiasts were thought of as dissenters.

Jane Austen wasn’t comfortable with the Evangelical movement, a dislike that appears be more about modes of worship than doctrinal disputes. One gets the feeling that Austen (and probably her father and her family) thought overt, emotional displays were vulgar, or perhaps that those who protested their religious faith the loudest, were the least to be trusted.

However, Dr. Kelly argues that Austen was a dissenter. She thinks the words "humble Christian" in Austen's obituary are "problematic" and revealing. She points out that the "words 'humble Christian' had been strongly associated with writers who questioned Church of England orthodoxy," such as Methodists and Evangelicals.

Dr. Kelly thinks that Jane Austen arranged to be buried in Winchester Cathedral as a final act of defiance, not piety. Kelly believes that Mansfield Park is so anti- Church of England that mentioning Mansfield Park on her gravestone would have been Austen's way of thumbing her nose at the Anglican church for so long as her gravestone and the Cathedral exists. In other words, she wanted to be buried there out of spite, as a private joke. But it was "a joke that failed" because her relatives did not mention her radical novels on her gravestone inscription.

Dr. Kelly thinks that Jane Austen arranged to be buried in Winchester Cathedral as a final act of defiance, not piety. Kelly believes that Mansfield Park is so anti- Church of England that mentioning Mansfield Park on her gravestone would have been Austen's way of thumbing her nose at the Anglican church for so long as her gravestone and the Cathedral exists. In other words, she wanted to be buried there out of spite, as a private joke. But it was "a joke that failed" because her relatives did not mention her radical novels on her gravestone inscription. Frankly, I cannot roll my eyes hard enough at this assertion, which has to do with Kelly's contention that Mansfield Park has symbolic references to the sugar plantations in the West Indies owned by the Church of England. These are references which I think Kelly has projected into the book.

It is interesting, and possibly significant, that Austen's gravestone does not mention her novels, but an obituary sent to the newspapers reveals her authorship. I might return to that later.

I think Austen's strongest expression of religiosity comes from Marianne in Sense & Sensibility, when she apologizes to Elinor for over-indulging in grief when Willoughby abandoned her, which led to her illness and nearly her death.

I think Austen's strongest expression of religiosity comes from Marianne in Sense & Sensibility, when she apologizes to Elinor for over-indulging in grief when Willoughby abandoned her, which led to her illness and nearly her death. "I wonder at my recovery,—wonder that the very eagerness of my desire to live, to have time for atonement to my God, and to you all, did not kill me at once."

Here, "wonder" means she is surprised that her passionate desire to live didn't kill her. She wants to atone, a more serious and profound word than mere apology. Marianne's feels her love for Willoughby can never be overcome but vows it will be "regulated, it shall be checked by religion, by reason, by constant employment." Religion goes hand-in-hand with reason, as it did for Dr. Johnson.

And a striking mention of Christianity comes when Henry Tilney realizes that Catherine Morland suspects his father murdered his mother. He gravely says: “If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to—Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians..."

And a striking mention of Christianity comes when Henry Tilney realizes that Catherine Morland suspects his father murdered his mother. He gravely says: “If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to—Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians..." Finally, Austen was not the only person to criticize the clergy. It was not illegal to criticize the clergy. It was not even socially unacceptable to criticize the clergy. We know this because Mary Crawford, a sophisticated Londoner, shows open disdain for the profession. In Mansfield Park, Edmund Bertram tells Mary Crawford that her criticisms of the clergy were "commonplace." If criticizing the clergy was commonplace, then it was hardly radical for Jane Austen to do so. I will expand on the topic of these commonplace censures in the next post. Next post: The clergy. We think of the previous age as being one in which religion played a larger role in daily life and in social and government institutions than it does today. For example, you could not attend Oxford or Cambridge unless you were a member of the Church of England and proclaimed your belief in the 39 Articles. I refer to this requirement in my novel A Marriage of Attachment when Lord Lynnon talks about his friend Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was expelled from Oxford for writing a pamphlet in support of atheism. Click here for more about my novels.

Published on October 26, 2020 00:00

October 23, 2020

CMP#8 "Mr. Elton is so good to the poor!"

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: A Duty to the Poor

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: A Duty to the Poor

Poverty was a fact of life in Georgian and Regency England. The standard of living for most people was at a subsistence level. Apart from a roof over their head, the average family had very few possessions. Austen and her family did not think of themselves as wealthy, but they bought books and were able to travel, and this alone put them in a different class from about 90% of their fellow Britons. It is estimated that one in seven people in Britain turned to public welfare at one time or another for food and money to survive, and yet, England was regarded as more prosperous than other nations -- that is, you had a better chance of not living in abject misery if you were British, as opposed to being French or Italian.

Poverty was a fact of life in Georgian and Regency England. The standard of living for most people was at a subsistence level. Apart from a roof over their head, the average family had very few possessions. Austen and her family did not think of themselves as wealthy, but they bought books and were able to travel, and this alone put them in a different class from about 90% of their fellow Britons. It is estimated that one in seven people in Britain turned to public welfare at one time or another for food and money to survive, and yet, England was regarded as more prosperous than other nations -- that is, you had a better chance of not living in abject misery if you were British, as opposed to being French or Italian.In Jane Austen's day, there were strict distinctions made between the “deserving poor” and those who brought misfortune upon themselves through laziness and idleness. When catastrophe befell a family, if the mother died in childbirth or the father was injured at work, stricken families relied upon their local parish authorities for relief.

Charity was given out at the parish level, not as part of a national welfare plan. That’s because everybody in your village knew you, and knew your habits, and they knew if you were hardworking and therefore deserving, or if you were improvident, shiftless and dissolute. (And yes, as today, rich people could live recklessly without facing the consequences that poor people face.) It also meant that the parish was not obliged to look after strangers. Too many poor people would drive up the poor rates.

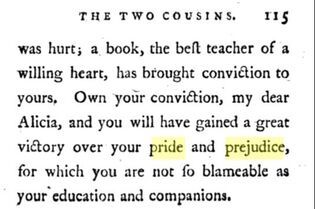

In The Two Cousins , (1794) the virtuous Mrs. Leyster finds a woman and her baby unconscious in the snow. She summons her servants to carry them to her home and when the women recovers, Mrs. Leyster learns that she is the widow of a carpenter who broke his arm and then succumbed to consumption (tuberculosis). The widow left her parish to take up a promised job, which fell through. Destitute and starving, she and her child would have died but for their rescue. Mrs. Leyster sets her up in a small cottage business -- but only after first confirming the truth of her story and the respectability of her character.

It was feared that over-generous, over-abundant charity would invite more idleness and vice.

"The Rake's Progress," W. Hogarth "It is not my way to find fault with People because they are poor, for I always think that they are more to be despised and pitied than blamed for it, especially if they cannot help it," says a titled lady in one of Austen's lively sketches written in her youth.

"The Rake's Progress," W. Hogarth "It is not my way to find fault with People because they are poor, for I always think that they are more to be despised and pitied than blamed for it, especially if they cannot help it," says a titled lady in one of Austen's lively sketches written in her youth.It's true enough, though. Back then, nobody would describe an alcoholic living on the street with the non-judgmental term "experiencing homelessness." They might reach out to help such a person, as an act of Christian charity, but they would also warn against the vice of drunkenness.

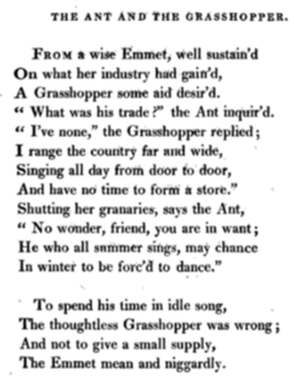

Georgian and Regency attitudes toward the poor can be summed up in Aesop’s fable of the grasshopper and the ants. Below is a poem from 1809, in which Sir Brooke Boothby uses the dialect word “emmet” for ant. The grasshopper is thoughtless for not preparing for the winter, but the ant is also criticized for not helping the grasshopper.

("Niggardly” has a completely separate etymological derivation from that other word you are thinking of. “Niggardly” is from Old Norse, presumably from the Vikings. )

It was the moral duty of rich families to dispense charity in their respective parishes, as we see Emma and Harriet doing in Emma, and Lady Catherine deBourgh doing in Pride & Prejudice. We know that they dispense advice along with the alms.

It was the moral duty of rich families to dispense charity in their respective parishes, as we see Emma and Harriet doing in Emma, and Lady Catherine deBourgh doing in Pride & Prejudice. We know that they dispense advice along with the alms. When Austen breaks the fourth wall and directly editorializes to her readers, we must assume that the topic she is talking about, the point she is making, is important to her, otherwise she would not break the fourth wall.

So she bestows some rare praise on Emma and while doing so, shares her opinions about poor people. She says approvingly that Emma “was very compassionate; and the distresses of the poor were as sure of relief from her personal attention and kindness, her counsel and her patience, as from her purse. She understood their ways, could allow for their ignorance and their temptations, had no romantic expectations of extraordinary virtue from those for whom education had done so little; entered into their troubles with ready sympathy, and always gave her assistance with as much intelligence as good-will.”

On this particular errand, however, we learn that Emma is glad that another motive for her charity arises -- the chance to show Harriet off to Mr. Elton in a good light.

Ready sympathy for the poor We are told in Persuasion that Admiral Croft and his wife gave “the poor... the best attention and relief” after they rented Kellynch Hall from the feckless Sir Walter Elliot. No doubt the Admiral and his wife are kinder and more generous to Sir Walter's tenants than Sir Walter himself.

Ready sympathy for the poor We are told in Persuasion that Admiral Croft and his wife gave “the poor... the best attention and relief” after they rented Kellynch Hall from the feckless Sir Walter Elliot. No doubt the Admiral and his wife are kinder and more generous to Sir Walter's tenants than Sir Walter himself. When Marianne marries Colonel Brandon, she becomes “the patroness of a village,” in other words, she willingly takes on the duty of looking after the well-being of the local people. Perhaps she will be like Austen's much-beloved older friend, Mrs. Anne LeFroy, a clergyman's wife, who lived in the neighbouring parish. As described in Paula Byrne's biography of Austen, LeFroy personally inoculated the poor in her parish against the smallpox. She started a cottage industry for the women and girls to raise straw for straw plaiting, used in hats and baskets. She opened a school for the village children and taught reading herself.

Even the miserable Mrs. Norris superintends the "poor basket" at Mansfield Park. The ladies of the park make clothing for poor people when they are not embroidering footstools or making fringe. It is a given, a routine activity for genteel women.

Mr. Darcy's housekeeper at Pemberley, Mrs. Reynolds, mentions Mr. Darcy's charity before any other virtue in response to Mrs. Gardiner's “His father was an excellent man."

“Yes, ma’am, that he was indeed; and his son will be just like him—just as affable to the poor.”

These charitable impulses, however, were not extended to Gypsies. In Austen's England, they were regarded as a race of parasites, people who followed a vagabond lifestyle and survived by begging and stealing. Rumours persisted that the gypsies stole little children. They were permanent outsiders from society.

These charitable impulses, however, were not extended to Gypsies. In Austen's England, they were regarded as a race of parasites, people who followed a vagabond lifestyle and survived by begging and stealing. Rumours persisted that the gypsies stole little children. They were permanent outsiders from society. They are exotic and unexpected in the quiet village of Highbury, "Nothing of the sort had ever occurred before to any young ladies in the place," and they are not welcome.

Harriet was soon assailed by half a dozen children, headed by a stout woman and a great boy, all clamorous, and impertinent in look, though not absolutely in word.—More and more frightened, she immediately promised them money, and taking out her purse, gave them a shilling, and begged them not to want more, or to use her ill.—She was then able to walk, though but slowly, and was moving away—but her terror and her purse were too tempting, and she was followed, or rather surrounded, by the whole gang, demanding more.

In this state Frank Churchill had found her, she trembling and conditioning, they loud and insolent.

Harriet is shown here as acting like a silly goose, but there is also nothing sympathetic in Austen's portrayal of the gypsies. They are described as impertinent and insolent.

Austen says the gypsies "did not wait for the operations of justice; they took themselves off in a hurry," that is, before Knightley or anyone can get up a posse to drive them out. (Recall that bylaw officers and police do not exist at this period in history.) Austen does not explain or justify the response of the village. She would not have expected her readers to disagree with the response. Austen’s view of the poor was a paternalistic one, or to use the term she would use, a condescending one. Helping the poor -- at least, the poor of one's own parish--is one of her implicit values, it is something a good person does, even without explicit reference to religion.

Which is a bit of an odd thing -- Austen was undoubtedly a Christian and a member of the Church of England, but she seldom mentions religion directly. Why is this?

Next post: Decorum in Religion In my novel, A Marriage of Attachment , Fanny Price works for a charitable society, teaching sewing skills to poor girls. The "Society for Bettering the Condition and Increasing the Comforts of the Poor" was a real society, patronized by William Wilberforce. The Society looked for practical ways to educate and help the lowest ranks of society. Click here for more info about my books.

Published on October 23, 2020 00:00

October 20, 2020

CMP#7: Poverty and marriage

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Marry Prudently One reason for Austen's enduring popularity is the timelessness of her novels. She creates characters and situations that are familiar to us. We talk about her characters as though they were real people. We even argue about them. But in this post I want to talk about how Austen's world was different from ours. In a previous post, I talked about the economic realities of Austen’s time. All her novels are placed before the great explosion in national income which occurred with the Industrial Revolution. When we look at the world 200 years ago, it was not a world where everybody had adequate shelter, food, clothing and medical care. There was no police force to investigate crime. Many people agreed with Thomas Malthus that starvation was effectively the only way growing populations would be curbed.

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Marry Prudently One reason for Austen's enduring popularity is the timelessness of her novels. She creates characters and situations that are familiar to us. We talk about her characters as though they were real people. We even argue about them. But in this post I want to talk about how Austen's world was different from ours. In a previous post, I talked about the economic realities of Austen’s time. All her novels are placed before the great explosion in national income which occurred with the Industrial Revolution. When we look at the world 200 years ago, it was not a world where everybody had adequate shelter, food, clothing and medical care. There was no police force to investigate crime. Many people agreed with Thomas Malthus that starvation was effectively the only way growing populations would be curbed. At the conclusion of Persuasion, Austen writes: "When any two young people take it into their heads to marry, they are pretty sure by perseverance to carry their point, be they ever so poor, or ever so imprudent, or ever so little likely to be necessary to each other's ultimate comfort. This may be bad morality to conclude with, but I believe it to be truth."

Notice that even before compatibility, Austen lists poverty as a serious barrier to marriage, and she considers this to be a moral question. Even as a teenager, Austen understood that married people needed something to live on. In her youthful burlesque, Love and Freindship, the passionate Edward disdains to ask his father for an allowance when he marries against his parent’s wishes. He tells his sister: "Support! What Support will Laura want which she can receive from him?"

"Only those very insignificant ones of Victuals and Drink," (answered she).

"Victuals and Drink! (replied my Husband in a most nobly contemptuous Manner) and dost thou then imagine that there is no other support for an exalted Mind (such as is my Laura's) than the mean and indelicate employment of Eating and Drinking?"

"None that I know of, so efficacious," (returned Augusta).

"And did you then never feel the pleasing Pangs of Love, Augusta? (replied my Edward) Does it appear impossible to your vile and corrupted Palate, to exist on Love? Can you not conceive the Luxury of living in every Distress that Poverty can inflict, with the object of your tenderest Affection?"

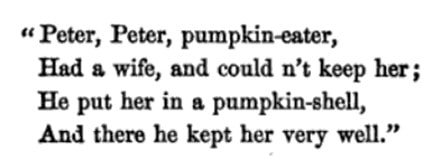

In this old nursery rhyme, "keep" means support, not retain In Emma, Robert Martin, a yeoman farmer, comes to consult with Mr. Knightley before he proposes to Harriet Smith. Knightley tells Emma, "I had no hesitation in advising him to marry. He proved to me that he could afford it; and that being the case, I was convinced he could not do better."

In this old nursery rhyme, "keep" means support, not retain In Emma, Robert Martin, a yeoman farmer, comes to consult with Mr. Knightley before he proposes to Harriet Smith. Knightley tells Emma, "I had no hesitation in advising him to marry. He proved to me that he could afford it; and that being the case, I was convinced he could not do better."In Sense & Sensibility, the usually cheerful Mrs. Jennings soberly predicts that Edward Ferrars and Lucy Steele "will set down upon a curacy of fifty pounds a-year, with the interest of his two thousand pounds, and what little matter Mr. Steele and Mr. Pratt can give her.—Then they will have a child every year! and Lord help 'em! how poor they will be!"

Mrs. Croft, a sensible and likeable woman, declares in Persuasion, "To begin without knowing that at such a time there will be the means of marrying, I hold to be very unsafe and unwise, and what I think all parents should prevent as far as they can."

Sir Thomas Bertram of Mansfield Park “is an advocate for early marriages, where there are means in proportion." Early marriage helps a young man avoid temptation, of course. Sir Thomas “would have every young man, with a sufficient income, settle as soon after four-and-twenty as he can.” Note how he repeats himself on the matter of income. And while Austen presents Sir Thomas as a man with faults, she does not portray him as malicious or wrong-headed in his basic principles.

Parents had strong views about who their children would marry, because the right marriage could increase the security and prosperity of the entire family but an imprudent marriage could lead to disaster, as is illustrated by the contrast between the fates of the three Ward sisters in Mansfield Park.

Life is a matter of trade offs, as Charlotte Lucas could tell us The fierce moral codes of Austen's day arose from an economic imperative as well as a religious one. In the long 18th century, in a world where a single mother is dependent upon meagre parish relief, society had a vested interest in discouraging the proliferation of single mothers.

Life is a matter of trade offs, as Charlotte Lucas could tell us The fierce moral codes of Austen's day arose from an economic imperative as well as a religious one. In the long 18th century, in a world where a single mother is dependent upon meagre parish relief, society had a vested interest in discouraging the proliferation of single mothers. The result of this social and legal clampdown, obviously, is that there were a lot of unhappy marriages and just general hypocrisy.

If women were not in a position to get married, they were expected to remain chaste. However, the middle and lower classes of Austen's time were well aware of the prevalence of infidelity and illegitimacy in the upper classes. What was preached for the lower classes was flouted by the privileged few. King George III's three sons had over 50 illegitimate children. He had only one legitimate grandchild, Princess Charlotte.

But all choices are a matter of trade-offs, even today. One of the downsides of modern sexual license is that fewer children today know the stability of growing with the same two parents. Today half the children in England are born out of wedlock and the percentages are even higher in other countries.

Past and Present 3 by Augustus Egg, 1858 Since the 18th century, therefore, we have seen a relaxing of strict moral codes, and more honesty in general about sexual activity. We have also seen a great rise in prosperity. Only a prosperous society can afford to subsidize hundreds of thousands of households that cannot support themselves. Remember the chart. As we have seen, the message is repeated throughout Austen -- don't get married if you are not in a position to support your wife and any children that come along. Before Edward and Elinor get their happy ever after in Sense & Sensibility, Austen spells out, in detail, how much money they will have. Colonel Brandon gives Edward a living in Delaford which he reckons would enable a bachelor to live comfortably but "it cannot enable him to marry." The lovebirds also have three thousand pounds between them, which, invested at four or five percent, brings them another 160 and 200 pounds a year, "and they were neither of them quite enough in love to think that three hundred and fifty pounds a-year would supply them with the comforts of life." Fortunately, Edward's mother provides another ten thousand pounds which will give them another 400 a year.

Past and Present 3 by Augustus Egg, 1858 Since the 18th century, therefore, we have seen a relaxing of strict moral codes, and more honesty in general about sexual activity. We have also seen a great rise in prosperity. Only a prosperous society can afford to subsidize hundreds of thousands of households that cannot support themselves. Remember the chart. As we have seen, the message is repeated throughout Austen -- don't get married if you are not in a position to support your wife and any children that come along. Before Edward and Elinor get their happy ever after in Sense & Sensibility, Austen spells out, in detail, how much money they will have. Colonel Brandon gives Edward a living in Delaford which he reckons would enable a bachelor to live comfortably but "it cannot enable him to marry." The lovebirds also have three thousand pounds between them, which, invested at four or five percent, brings them another 160 and 200 pounds a year, "and they were neither of them quite enough in love to think that three hundred and fifty pounds a-year would supply them with the comforts of life." Fortunately, Edward's mother provides another ten thousand pounds which will give them another 400 a year.Austen is at pains to prove to her reader that Elinor and Edward are not doing anything rash. Perhaps she was thinking of her own family--her father married her mother on the narrow income of a clergyman, had eight children, and when he died, Mrs. Austen, Jane and Cassandra were not only homeless but thrown into dependence on Jane's brothers.

Strict moral codes were not just a tool of the Patriarchy to oppress and control women for the fun of it. They were intended to prevent the creation of too many mouths to feed.

Next post: Attitudes towards the poor.

Here's another, earlier post about Austen, marriage and romance novels.

Published on October 20, 2020 00:00

October 1, 2020

CMP#6 What is Pride & Prejudice about? R-E-S-P-E-C-T

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series.

In my previous post, I looked at (and rejected) the theory that Pride & Prejudice takes an anti-aristocracy approach. After all, Elizabeth and Jane marry wealthy men. Mr. Bingley's father acquired his wealth in trade but Mr. Bingley is going to settle down on an estate and be a gentleman. John Green of the YouTube video series Crash Course points out that "Wickham, the upstart who comes from the servant class, is the villain" in the novel.