Lona Manning's Blog, page 28

February 29, 2020

Featured at Austenprose!

I'm excited to be featured at Austenprose, one of the more erudite Jane Austen blogs out there, with a brief excerpt from A Different Woman. Thanks very much to blog proprietress Laurel Ann Nattress.

I'm excited to be featured at Austenprose, one of the more erudite Jane Austen blogs out there, with a brief excerpt from A Different Woman. Thanks very much to blog proprietress Laurel Ann Nattress.The cover of this final book in the Mansfield Trilogy carries on with the "tree" theme. Once again I worked with Dissect Designs. The emphasis on the four different seasons is our attempt to convey that this book is more of a collection of separate stories, wrapping up the story lines of the various characters. Fanny and William Gibson, Edmund Bertram and Mary Crawford, Maria Bertram Crawford and Fanny's brother John Price. A lot going on in this last book!

Published on February 29, 2020 09:09

January 16, 2020

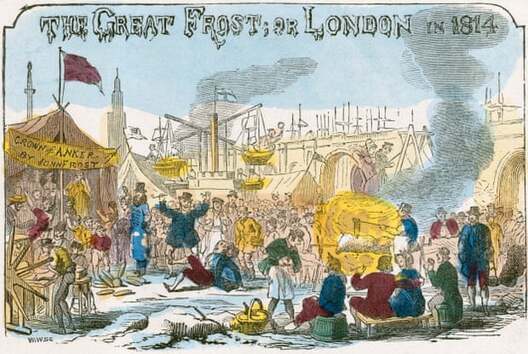

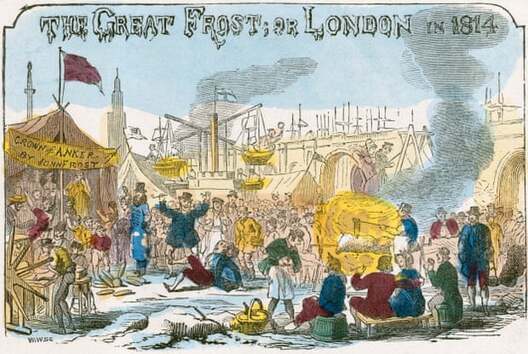

FROST FAIR -- an excerpt from my forthcoming novel

The finale to my Mansfield Trilogy is on the way!

Here is an excerpt from A Different Woman about John Price, Fanny Price's brother, bumping into his older brother Richard on a cold winter's day in London. Richard is a third mate with the East India Company. He's back from Cathay, and the two brothers decide to walk onto the Thames, which is frozen over. A Frost Fair is being held on the river.

The two brothers walked down the quay and awkwardly slid down the causeway to the frozen river. The Thames was black with people and tents; they could hear a fiddler playing an Irish air, and young girls shrieked with laughter on the swings. They could smell wood-smoke and roasting meat.

The two brothers walked down the quay and awkwardly slid down the causeway to the frozen river. The Thames was black with people and tents; they could hear a fiddler playing an Irish air, and young girls shrieked with laughter on the swings. They could smell wood-smoke and roasting meat.

Richard hailed the sight of a temporary tavern made of two canopies stitched together, called the “North-West Passage.” John ignored his invitation to go in for a drink and instead wandered slowly along the row of stalls that stretched almost across to the opposite bank.

The usual foul stench of the river was subdued by the cold, and the thick layer of ice beneath his feet. As to the thickness of the ice, he had no qualms about walking where so many others went, but he wished to know its precise thickness, merely as a knowable fact, because not knowing that fact was like an itch he could not scratch. He supposed someone in authority had drilled a hole and had measured the ice, to ensure the safety of the populace, and he hoped the information might be supplied somewhere, or had been printed in the papers.

Out of habit, he also watched the people, training himself to spot pick-pockets. Everyone appeared to be in excellent spirits. Rationally, though, John could see no advantage to walking out on a frozen river to go shopping. The same articles were for sale on the ice that one might buy anywhere, on any day—honey in the comb, candles, gloves. And yet everyone treated the occasion like a festival day. Just the novelty of being able to walk on the Thames, and suddenly everyone was willing to pay a higher price for gingerbread. There was no understanding people sometimes.

He came across a small bundle of rags which someone had left upon a low wooden stool. The bundle moved and he saw it was a tiny, hunchbacked old woman. Two crutches lay on the ice in front of her. She extended a bony hand with long dirty fingernails. “Your fortune, young sir?”

“Pardon?” said John.

“I can trace your fortune, sir. Give me your palm.”

John’s hands were firmly tucked in his pockets, out of her grasp.

He looked at her. “You can see into the future?”

“Yes, sir. I have the sight.”

“Then why are you dressed in rags if you know which horse will win at Newmarket?”

The woman gave John a piercing look. “Sir, I do not see horses, I see destinies.”

“So can I. I can tell you what yours is, for I am about to report you to the river police. You will be brought up at the Old Bailey, and you will be placed in the stocks. I’m surprised you did not know that.”

The woman swore a colourful string of oaths at him, snatched up her stool and crutches, and scurried away with surprising rapidity.

John continued his exploration of the fair and came across a stall of books. Out of habit, he started glancing over the titles laid out on the wooden counter.

“Well, hello yourself, John Price,” said a female voice. He looked up and saw a small figure swaddled in blankets and scarves standing behind the counter, and recognised Prudence Imlay, whose father owned his favourite book shop.

“Oh, hello Miss Imlay,” John answered. “How do you like being on the river?”

“I am slowly freezing to death,” answered Miss Imlay calmly. “And I might as well not have bothered to drag all these books down here. These, on the other hand, are extremely popular.” And she held out a poster with an engraving of London Bridge and a bit of doggerel:

The season cold

You now behold

A sight that’s very rare

All in a trice

Upon the ice

Just like a Russian fair.

“What a terrible verse,” said John.

“I know. I wrote it,” answered she. “The first time I have sold my writing to the public and it has to be this.”

John wanted to say something encouraging. “Maybe if you write something better, the public will like it as well.”

“Are you going to buy a book, John Price?”

“Not today. I spent all my money at the King’s Arms.”

“Oh!” she said, surprised. “That’s not like you, surely.”

“For my brother,” he amended.

“Ah, well, you seldom buy our books anyway. Father says you treat our shop like a lending library.”

“That is why I take care to visit when he is not there,” said John. “And anyway, I prefer it when you are there.”

Miss Imlay looked away, then looked back.

“I think you are getting too cold,” said John, “your cheeks are turning red. If they turn white, then it is frostbite. You should be careful.”

Richard appeared out of the throng, and saluted John with another hearty slap on the back.

“Ho, John, you artful bugger! Not so backward with the ladies after all!” And he turned to bestow a devastating smile on Miss Imlay. He looked at her, and his smile dissolved.

“Oh,” he said, taking in the red smallpox scars which disfigured her entire face.

The girl flushed again, and turned away. “I think I shall start packing up. The sun is going down.” She bent down and disappeared behind the counter.

“Do you want any help, Miss Imlay?” asked John.

“No, thank you,” came her voice. “I can do it myself. My father is meeting me at the quay.”

“Very well, good afternoon,” said John, and he and Richard walked away.

“Poor girl—what a shame,” said Richard, his loud voice carrying across the ice. “Nice eyes. Pretty hair, too. Too bad about her face.”

“What about her face?” asked John.

“The pock-marks, what d’you think I meant!” Richard laughed. “There isn’t enough ale in London to make her into a beauty.”

“That is just her skin,” answered John. “That is not... that is not... what she looks like.” He tried to explain but Richard was not listening anyway. He was reverting to the subject of his missing seaman's chest.

“Three of us from the Neptune brought our chests to the warehouse on the same day. Billy Simpkins, Tom Prunty and me. Last October it was.”

Something was making John feel uncomfortable. He was not sure what it was. He thought he should go back to talk to Miss Imlay. “You go on, Richard,” he said. “Meet me back here tomorrow at the North-West Passage. Around midday.”

He ran, slipping and sliding, back along the rows of stalls, dodging children and stray dogs.

Prudence Imlay was still clearing the books off the counter.

“Even if you do not need help, Miss Imlay,” said John, “I can help you. That is, do you want help?”

Prudence tossed her head, but made no reply.

“Is something wrong? Are you angry?” asked John.

“Leave it to you, John Price, to not know when somebody is angry,” said Prudence. “A fine thief catcher you would make, if you do not know if someone is angry, or happy, or sad.”

“Are... you feeling sad?”

Prudence sighed. “I caught the smallpox when I was a child, and I did not die, but I know what I look like, and—and—that is just the way things are and I cannot change it. And I do not want to talk about it.”

“All right,” said John. He was rather relieved, because he was not good at that sort of talking. “Are you sure you do not want any help?” He was going to add, “books are heavy,” but decided that she, a book-seller’s daughter, already knew books were heavy.

“Not today, John,” said Prudence. “Go away.” The King's Arms was a real tavern and lodging-house for sailors. The London Mudlark found an ale jug from the King's Arms while scavenging along the banks of the Thames. More about the 1814 Frost Fair at Madame Gilflurt's blog.

The East India Company sent trading ships to India and China to bring back silk, shawls, spices and more.

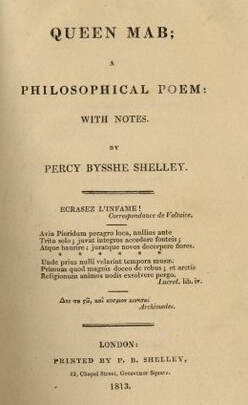

My novel, A Different Kind of Woman, is available for pre-order on Amazon now! In the exciting conclusion of the Mansfield Trilogy, the lives and destinies of Jane Austen’s well-known characters are deftly blended with dramatic historical events. Fanny Price is torn between her love for William Gibson and her duty to her family. In London, Fanny’s brother John meets his match in a feisty bookseller’s daughter. And Edmund Bertram’s wife Mary meets the charismatic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and risks everything to gain the power and influence she craves.

In the exciting conclusion of the Mansfield Trilogy, the lives and destinies of Jane Austen’s well-known characters are deftly blended with dramatic historical events. Fanny Price is torn between her love for William Gibson and her duty to her family. In London, Fanny’s brother John meets his match in a feisty bookseller’s daughter. And Edmund Bertram’s wife Mary meets the charismatic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and risks everything to gain the power and influence she craves.

Regency England comes alive in this tale of love, loss and second chances set against the real-life backdrop of political turmoil in England.

Here is an excerpt from A Different Woman about John Price, Fanny Price's brother, bumping into his older brother Richard on a cold winter's day in London. Richard is a third mate with the East India Company. He's back from Cathay, and the two brothers decide to walk onto the Thames, which is frozen over. A Frost Fair is being held on the river.

The two brothers walked down the quay and awkwardly slid down the causeway to the frozen river. The Thames was black with people and tents; they could hear a fiddler playing an Irish air, and young girls shrieked with laughter on the swings. They could smell wood-smoke and roasting meat.

The two brothers walked down the quay and awkwardly slid down the causeway to the frozen river. The Thames was black with people and tents; they could hear a fiddler playing an Irish air, and young girls shrieked with laughter on the swings. They could smell wood-smoke and roasting meat.Richard hailed the sight of a temporary tavern made of two canopies stitched together, called the “North-West Passage.” John ignored his invitation to go in for a drink and instead wandered slowly along the row of stalls that stretched almost across to the opposite bank.

The usual foul stench of the river was subdued by the cold, and the thick layer of ice beneath his feet. As to the thickness of the ice, he had no qualms about walking where so many others went, but he wished to know its precise thickness, merely as a knowable fact, because not knowing that fact was like an itch he could not scratch. He supposed someone in authority had drilled a hole and had measured the ice, to ensure the safety of the populace, and he hoped the information might be supplied somewhere, or had been printed in the papers.

Out of habit, he also watched the people, training himself to spot pick-pockets. Everyone appeared to be in excellent spirits. Rationally, though, John could see no advantage to walking out on a frozen river to go shopping. The same articles were for sale on the ice that one might buy anywhere, on any day—honey in the comb, candles, gloves. And yet everyone treated the occasion like a festival day. Just the novelty of being able to walk on the Thames, and suddenly everyone was willing to pay a higher price for gingerbread. There was no understanding people sometimes.

He came across a small bundle of rags which someone had left upon a low wooden stool. The bundle moved and he saw it was a tiny, hunchbacked old woman. Two crutches lay on the ice in front of her. She extended a bony hand with long dirty fingernails. “Your fortune, young sir?”

“Pardon?” said John.

“I can trace your fortune, sir. Give me your palm.”

John’s hands were firmly tucked in his pockets, out of her grasp.

He looked at her. “You can see into the future?”

“Yes, sir. I have the sight.”

“Then why are you dressed in rags if you know which horse will win at Newmarket?”

The woman gave John a piercing look. “Sir, I do not see horses, I see destinies.”

“So can I. I can tell you what yours is, for I am about to report you to the river police. You will be brought up at the Old Bailey, and you will be placed in the stocks. I’m surprised you did not know that.”

The woman swore a colourful string of oaths at him, snatched up her stool and crutches, and scurried away with surprising rapidity.

John continued his exploration of the fair and came across a stall of books. Out of habit, he started glancing over the titles laid out on the wooden counter.

“Well, hello yourself, John Price,” said a female voice. He looked up and saw a small figure swaddled in blankets and scarves standing behind the counter, and recognised Prudence Imlay, whose father owned his favourite book shop.

“Oh, hello Miss Imlay,” John answered. “How do you like being on the river?”

“I am slowly freezing to death,” answered Miss Imlay calmly. “And I might as well not have bothered to drag all these books down here. These, on the other hand, are extremely popular.” And she held out a poster with an engraving of London Bridge and a bit of doggerel:

The season cold

You now behold

A sight that’s very rare

All in a trice

Upon the ice

Just like a Russian fair.

“What a terrible verse,” said John.

“I know. I wrote it,” answered she. “The first time I have sold my writing to the public and it has to be this.”

John wanted to say something encouraging. “Maybe if you write something better, the public will like it as well.”

“Are you going to buy a book, John Price?”

“Not today. I spent all my money at the King’s Arms.”

“Oh!” she said, surprised. “That’s not like you, surely.”

“For my brother,” he amended.

“Ah, well, you seldom buy our books anyway. Father says you treat our shop like a lending library.”

“That is why I take care to visit when he is not there,” said John. “And anyway, I prefer it when you are there.”

Miss Imlay looked away, then looked back.

“I think you are getting too cold,” said John, “your cheeks are turning red. If they turn white, then it is frostbite. You should be careful.”

Richard appeared out of the throng, and saluted John with another hearty slap on the back.

“Ho, John, you artful bugger! Not so backward with the ladies after all!” And he turned to bestow a devastating smile on Miss Imlay. He looked at her, and his smile dissolved.

“Oh,” he said, taking in the red smallpox scars which disfigured her entire face.

The girl flushed again, and turned away. “I think I shall start packing up. The sun is going down.” She bent down and disappeared behind the counter.

“Do you want any help, Miss Imlay?” asked John.

“No, thank you,” came her voice. “I can do it myself. My father is meeting me at the quay.”

“Very well, good afternoon,” said John, and he and Richard walked away.

“Poor girl—what a shame,” said Richard, his loud voice carrying across the ice. “Nice eyes. Pretty hair, too. Too bad about her face.”

“What about her face?” asked John.

“The pock-marks, what d’you think I meant!” Richard laughed. “There isn’t enough ale in London to make her into a beauty.”

“That is just her skin,” answered John. “That is not... that is not... what she looks like.” He tried to explain but Richard was not listening anyway. He was reverting to the subject of his missing seaman's chest.

“Three of us from the Neptune brought our chests to the warehouse on the same day. Billy Simpkins, Tom Prunty and me. Last October it was.”

Something was making John feel uncomfortable. He was not sure what it was. He thought he should go back to talk to Miss Imlay. “You go on, Richard,” he said. “Meet me back here tomorrow at the North-West Passage. Around midday.”

He ran, slipping and sliding, back along the rows of stalls, dodging children and stray dogs.

Prudence Imlay was still clearing the books off the counter.

“Even if you do not need help, Miss Imlay,” said John, “I can help you. That is, do you want help?”

Prudence tossed her head, but made no reply.

“Is something wrong? Are you angry?” asked John.

“Leave it to you, John Price, to not know when somebody is angry,” said Prudence. “A fine thief catcher you would make, if you do not know if someone is angry, or happy, or sad.”

“Are... you feeling sad?”

Prudence sighed. “I caught the smallpox when I was a child, and I did not die, but I know what I look like, and—and—that is just the way things are and I cannot change it. And I do not want to talk about it.”

“All right,” said John. He was rather relieved, because he was not good at that sort of talking. “Are you sure you do not want any help?” He was going to add, “books are heavy,” but decided that she, a book-seller’s daughter, already knew books were heavy.

“Not today, John,” said Prudence. “Go away.” The King's Arms was a real tavern and lodging-house for sailors. The London Mudlark found an ale jug from the King's Arms while scavenging along the banks of the Thames. More about the 1814 Frost Fair at Madame Gilflurt's blog.

The East India Company sent trading ships to India and China to bring back silk, shawls, spices and more.

My novel, A Different Kind of Woman, is available for pre-order on Amazon now!

In the exciting conclusion of the Mansfield Trilogy, the lives and destinies of Jane Austen’s well-known characters are deftly blended with dramatic historical events. Fanny Price is torn between her love for William Gibson and her duty to her family. In London, Fanny’s brother John meets his match in a feisty bookseller’s daughter. And Edmund Bertram’s wife Mary meets the charismatic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and risks everything to gain the power and influence she craves.

In the exciting conclusion of the Mansfield Trilogy, the lives and destinies of Jane Austen’s well-known characters are deftly blended with dramatic historical events. Fanny Price is torn between her love for William Gibson and her duty to her family. In London, Fanny’s brother John meets his match in a feisty bookseller’s daughter. And Edmund Bertram’s wife Mary meets the charismatic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and risks everything to gain the power and influence she craves.Regency England comes alive in this tale of love, loss and second chances set against the real-life backdrop of political turmoil in England.

Published on January 16, 2020 17:54

December 26, 2019

"That my beloved Shelley should stand thus slandered"

As I discussed in previous blog posts, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley named himself as

the father of a baby girl

in Naples in February of 1819. Whether or not he was truly the father is unknown, but historians are certain that the mother couldn't have been his wife Mary Shelley. However, some people think the mother might have been Claire Clairmont, Mary's step-sister, who accompanied them to Italy. (The portrait to the left was painted in Rome by their friend Amelia Curran. Claire didn't care for this portrait.)

As I discussed in previous blog posts, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley named himself as

the father of a baby girl

in Naples in February of 1819. Whether or not he was truly the father is unknown, but historians are certain that the mother couldn't have been his wife Mary Shelley. However, some people think the mother might have been Claire Clairmont, Mary's step-sister, who accompanied them to Italy. (The portrait to the left was painted in Rome by their friend Amelia Curran. Claire didn't care for this portrait.)Claire already had a daughter by Lord Byron, and she went with Shelley to Venice, ostensibly to visit her little daughter. So Claire was travelling with Shelley for several weeks without Mary, something which would raise eyebrows even today.

In Venice, Claire and Shelley met the English consul-general, Richard Hoppner and his wife. A year and a half later, Shelley paid another visit to Lord Byron, and Byron told him that Mr. Hoppner had sent him a letter with some shocking gossip. (Byron had held on to this gossip for a year before Shelley heard of it.) To recap the gossip chain here: Shelley fired his manservant, Paolo Foggi. At the same time, Foggi married the Shelley's nursemaid, Elise Duvillard. The following summer, Elise was in Venice and gossiped about the Shelleys and Claire to the Hoppners. Mr. Hoppner wrote a letter to Byron which showed to Shelley a year later. Most of Mr. Hoppner's letter is available online, here on page 20. (pdf)

Shelley wrote a letter to Mary, telling her about the Hoppner letter:

Elise says that Clare was my mistress – that is all very well & so far there is nothing new: all the world has heard so much & people may believe or not believe as they think good. – She then proceeds to say that Clare was with child by me – that I gave her the most violent medicines to procure abortion– that this not succeeding she was brought to bed & that I immediately tore the child from her & sent it to the foundling hospital ... as to what Reviews and the world say, I do not care a jot, but when persons who have known me are capable of conceiving of me--not that I have fallen into a great error, as would have been the living with Claire as my mistress, but that I have committed such unutterable crimes as destroying or abandoning a child, and that my own! Imagine my despair of good! Imagine how it is possible that one of so weak and sensitive a nature as mine can further run the gauntlet through this hellish society of men! Shelley's very excited here, so I will recap. He is saying, "people said I slept with your sister, but meh, we've heard that before, amirite? I don't care if the Literary Review back in England hints I've committed incest when they review my poetry, but what really upsets me is that anyone could think I'm the sort of person who could procure an abortion or abandon a child in a foundling home!"

Elise says that Clare was my mistress – that is all very well & so far there is nothing new: all the world has heard so much & people may believe or not believe as they think good. – She then proceeds to say that Clare was with child by me – that I gave her the most violent medicines to procure abortion– that this not succeeding she was brought to bed & that I immediately tore the child from her & sent it to the foundling hospital ... as to what Reviews and the world say, I do not care a jot, but when persons who have known me are capable of conceiving of me--not that I have fallen into a great error, as would have been the living with Claire as my mistress, but that I have committed such unutterable crimes as destroying or abandoning a child, and that my own! Imagine my despair of good! Imagine how it is possible that one of so weak and sensitive a nature as mine can further run the gauntlet through this hellish society of men! Shelley's very excited here, so I will recap. He is saying, "people said I slept with your sister, but meh, we've heard that before, amirite? I don't care if the Literary Review back in England hints I've committed incest when they review my poetry, but what really upsets me is that anyone could think I'm the sort of person who could procure an abortion or abandon a child in a foundling home!" First, let's pause to exclaim, along with Victorian-era Shelley biographer Thomas Cordy Jeaffreson , "Shelley said what to his wife?" Shelley, (the poet who according to his idolators might have been the Savior of the World), positively tells her that, if he had lived in adultery with her sister-by-affinity under her own roof, he would have been guilty of nothing worse than a 'great error.'

Baby hatch at the Church of the Annunziata in Naples No, the biggest outrage to everyone involved--Elise, the Hoppners, Byron and the Shelleys--was the imputation that Claire tried to obtain an abortion with Shelley's help (by bringing her to Venice) and when that failed, he abandoned the child. Everyone, the Shelleys, the Hoppners, even Byron express their revulsion at this.

Baby hatch at the Church of the Annunziata in Naples No, the biggest outrage to everyone involved--Elise, the Hoppners, Byron and the Shelleys--was the imputation that Claire tried to obtain an abortion with Shelley's help (by bringing her to Venice) and when that failed, he abandoned the child. Everyone, the Shelleys, the Hoppners, even Byron express their revulsion at this.Incidentally, at this time in Italy and in many places, churches made provision for desperate women to abandon their babies safely. (Of course when I say "safely," there was still a horrific infant mortality rate at the time). They could come to the church or foundling home in secrecy, deposit the baby anonymously in a device that resembled a lazy susan, and the baby would be taken into the foundling home and raised by nuns.

This kind of arrangement still survives in mainland China to this day. Parents can give up children whom they cannot provide for, or who are born out of wedlock without fear of reprisal.

However, Shelley did not dispose of Elena Adelaide in this fashion, although the possibility exists that he might have taken her from a foundling home. So Shelley could have replied with perfect honesty, "Hey, I never abandoned a child in a foundling home!" But he didn't say anything. He left it up to his wife. Shelley wrote Mary, as we have seen, repeating the details of the allegations. He then asked her to answer the Hoppner letter and defend his honour. which she promptly did, in a passionate letter.

Most of Mary's letter is taken up with telling Mrs. Hoppner how much she loves Shelley and how inconceivable it is that anyone could believe this terrible gossip about her wonderful husband, gossip which is so dreadful she would rather die than repeat it: I write to defend him to whom I have the happiness to be united, whom I love and esteem beyond all living creatures, from the foulest calumnies... to you I swear by all that I hold sacred upon heaven and earth, by a vow which I should die to write if I affirmed a falsehood, I swear by the life of my child, by my blessed, beloved child, that I know the accusations to be false. She also gave some background on Elise and Paolo Foggi, to explain why Mrs. Hoppner should never have believed them. As for the idea of Claire being pregnant, she pointed out that the three of them lived together, and although Claire was ill for a few days that winter, she couldn't have been in an advanced stage of pregnancy or given birth at home (which of course is how people gave birth back then) without Mary noticing.

Mary asserts: "I am perfectly convinced in my own mind that Shelley never had an improper connexion with Claire... Claire had no child."

Shelley buffs have said, "Ah-ha, she said, 'Claire had no child," she didn't say, 'there was no child.' And somebody must have had one, because there was a baby-- Elena Adelaide ." Further, Mary does not directly address the accusations about abandoning a child or an abortion, except to say it couldn't possibly be true and the idea is so vile that she can't even write the words. And so the story of Shelley and the mysterious lady and the mysterious baby basically ends there, except for a little bit more to do with Elise, which I discuss below.

People who have tried to sort out truth from falsehood and fact from gossip in this affair are confounded by the behaviour of everyone involved.

If Elise entered a shot-gun marriage with Paolo Foggi, why didn't they keep the baby?

Why would Shelley put his name on the birth certificate unless it was his child or unless he intended to adopt the baby and raise it as his own child. And if he needed or wanted to adopt a baby girl the night before he left Naples, why?

If Claire was the mother, why was she content to abandon the child with a Neapolitan family? She was heart-broken when she had to give her daughter Allegra to Lord Byron to raise; she greatly regretted doing so.

If Claire wasn't Shelley's mistress, why didn't Mary and Shelley insist that she write a letter to the Hoppners, telling them to stop spreading horrible gossip about her? These rumours affected her reputation as much as Shelley's and were more damaging for a lady than for a man.

OTOH, if Claire was Shelley's mistress, why did Shelley turn to his wife to defend him and why did she agree to do it?

If Elena Adelaide was a Neapolitan foundling whom Shelley adopted to help console Mary for the loss of their daughter Clara, why isn't that mentioned in the letter to the Hoppners? It would explain where the bizarre story came from and put the matter to rest.

Why did Shelley leave it up to his wife, who didn't go to Venice, to insist that he and Claire didn't have an affair? Was he just too distraught? Was he implying that the whole worrisome, ghastly business was beneath his notice? Is asking your wife to mop up a mess like this a very nice thing to do?

What if Shelley wanted Mary to write the denial precisely because she didn't know the whole truth? Whereas if he wrote a denial, he knew he would be lying about some or all of it?

And don't forget the mysterious lady. Why was Shelley telling Lord Byron and others that he was being pursued by a mysterious lady?

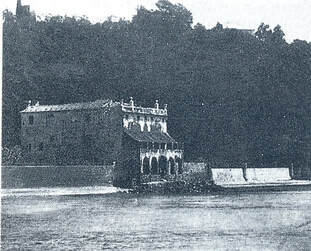

Casa Magni, Shelley's last home More perplexing behaviour: In 1820, Shelley and Mary were complaining that Paolo Foggi was blackmailing them and they had to

resort to a lawyer

to deal with it. Yet after Foggi was supposedly silenced, Foggi's wife Elise continued to write to Mary and ask for money. According to Mary, this was not an extortion letter, but a begging letter. As she told Mrs. Hoppner, "The other day I received a letter from Elise, entreating with great professions of love, that I should send her money!"

Casa Magni, Shelley's last home More perplexing behaviour: In 1820, Shelley and Mary were complaining that Paolo Foggi was blackmailing them and they had to

resort to a lawyer

to deal with it. Yet after Foggi was supposedly silenced, Foggi's wife Elise continued to write to Mary and ask for money. According to Mary, this was not an extortion letter, but a begging letter. As she told Mrs. Hoppner, "The other day I received a letter from Elise, entreating with great professions of love, that I should send her money!"As Shelley biographer Richard Holmes notes, "this was done in a quite innocent and beseeching way and without a hint of blackmail." This is further evidence, as far as I'm concerned, that there never was a blackmail attempt--the supposed blackmail by Paolo Foggi was just an invention of Shelley's to explain why he had to see his lawyer in Pisa. A further mystery--a mystery in the sense that it goes against what we know of human nature--in 1822, Elise and Claire met again in Florence. They met almost every day for a number of weeks. This despite the horrible things Elise had supposedly told the Hoppners about her, which included: having an affair with her sister's husband, and insulting and taunting her sister Mary every day with how Shelley didn't love her any more. For what it's worth, Elise denied ever saying any of those things to the Hoppners. In my forthcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman , I have provided some answers to these mysteries. Previous posts in this series:

Shelley and the Mysterious Lady

Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Who was Elena Adelaide?

A Falsified Birth Certificate

What happened to Elena Adelaide?

Paolo Foggi, that superlative rascal

Published on December 26, 2019 12:04

December 10, 2019

Paolo Foggi, "that superlative rascal"

Percy Bysshe Shelley This blog post is the seventh in my series about some enduring mysteries in the life of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Scroll down for links to the entire series.

Percy Bysshe Shelley This blog post is the seventh in my series about some enduring mysteries in the life of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Scroll down for links to the entire series.The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Shelley, along with her step-sister Claire Clairmont and their two little children, spent the summer of 1818 in the resort town of Bagni di Lucca, in Italy.

Naturally, their lovely villa came equipped with a cook and housemaid. They also had a nursemaid for the children. Mary's favourite nursemaid, the Swiss nanny Elise, was in Venice looking after Claire Clairmont’s daughter by Lord Byron, but an English girl named Milly stayed with them in Bagni di Lucca. And they had a man-servant, an Italian named Paoli Foggi.

Foggi was more or less in charge of running the household, dealing with tradesmen, doing the shopping and so forth. When Shelley and Claire Clairmont decided to go to Venice because she was worried about leaving her daughter Allegra in Byron’s custody, Foggi went to the nearby town of Lucca to arrange for transportation.

By the winter of 1819, the Shelleys were unhappy with Foggi, and dismissed him. Mary Shelley later explained that he had been stealing from them and furthermore, the nursemaid Elise Duvillard had “formed an attachment” to him; in other words, he’d gotten her pregnant and “we had them married.”

In recalling these events, Mary Shelley wrote that Elise was “in danger of a miscarriage” when she married Paolo Foggi. The newly-married couple left the Shelleys’ service and went to Rome. Was Elise pregnant when she left? Had she miscarried? Or did she deliver her baby in Naples before leaving for Rome? If she had given birth to a living baby that winter, then Foggi could not have been the father, as Elise was in living in Venice most of the previous year, looking after Allegra.

Some scholars have speculated that Elise is the

mother of Elena Adelaide

. But if the Paolo-Elise marriage was a shotgun marriage, then why would they leave their baby behind and why did Shelley claim to be the father

on the birth certificate

? And, if Elena Adelaide was Elise’s child, why did she later claim that Shelley and Claire Clairmont had a baby and abandoned it in a foundling home? Why bring up these accusations if the baby was in fact her child, by Foggi or by Shelley?

Some scholars have speculated that Elise is the

mother of Elena Adelaide

. But if the Paolo-Elise marriage was a shotgun marriage, then why would they leave their baby behind and why did Shelley claim to be the father

on the birth certificate

? And, if Elena Adelaide was Elise’s child, why did she later claim that Shelley and Claire Clairmont had a baby and abandoned it in a foundling home? Why bring up these accusations if the baby was in fact her child, by Foggi or by Shelley?In June 1820 Shelley told his friends the Gisbornes : “The rascal Paolo [Foggi] has been taking advantage of my situation at Naples in December 1818 to attempt to extort money by threatening to charge me with the most horrible crimes.”

Shelley does not specify what this “situation” was but it probably involves his Neapolitan “ward” Elena Adelaide.

The odd thing about this, which I've never seen any biographers discuss, is that successful blackmailers say, “give me money or else I will spill the beans on you.” But Foggi and Elise had already spilled the beans—they had already told the English-consul general in Venice, Richard Hoppner, that Shelley had gotten Claire pregnant, attempted to abort the child in Venice, then she gave birth and they abandoned the baby in Naples. Hoppner was so scandalized by this gossip that he wrote Lord Byron:*

“at the time the Shelleys were here [in Venice] [Claire] was with child by Shelley: you may remember to have heard that she was constantly unwell, & under the care of a Physician, and I am uncharitable enough to believe that the quantity of medicine she then took was not for the mere purpose of restoring her health. I perceive too why she preferred remaining alone at Este notwithstanding her fear of ghosts & robbers, to being here with the Shelleys.” The lurid details are here, on page 20 (pdf). Hoppner says, "This account we had from Elise (the nursemaid) who passed here this summer..."

Shelley and Mary lived here for a time in Livorno So we know Elise and perhaps Paolo were in Venice, spilling the beans, by May of 1820 or earlier. On June 15, Shelley made a flying visit to Livorno, then came back to Pisa and ordered Mary to pack up--they moved to Livorno. (Claire was living with an old friend from England at this point).

Shelley and Mary lived here for a time in Livorno So we know Elise and perhaps Paolo were in Venice, spilling the beans, by May of 1820 or earlier. On June 15, Shelley made a flying visit to Livorno, then came back to Pisa and ordered Mary to pack up--they moved to Livorno. (Claire was living with an old friend from England at this point).Shelley biographers repeat the explanation that Shelley and Mary Shelley gave to the Gisbornes: They needed the services of their lawyer Frederico Del Rosso in Livorno because Paolo Foggi sent “threatening letters saying he would be the ruin of [Shelley] and “laid an information” that is, laid some charges against Shelley. Del Rosso dealt with it somehow and Foggi was ordered to leave Livorno “in four hours.”

Was it that simple to "crush" a lowly servant who was making life unpleasant for a high-born Englishman? And how would ordering Foggi to get out of town prevent him from spreading his rumours or attempting blackmail? Rather, it would ensure that he would be even angrier. If he had travelled from Naples, to Rome, to Venice and then to Livorno, why would being told to get out of Livorno shut him up? This doesn’t make much sense to me. But this is the version given in Shelley biographies.

However, it appears the only source Shelley scholars have for the Foggi blackmail plot, is the letters Percy and Mary Shelley wrote to the Gisbornes. No threatening letters have survived and unfortunately neither have Del Rosso’s office files. So we have Shelley, at the exact same time he gets word that Elena Adelaide is very ill and may be dying, telling his wife, “Honey, we've got to move to Livorno right away. That pest, Paolo Foggi. has been sending me threatening letters.” (The Gisbornes were in England at that time, so the Shelleys moved into their empty house.)

Then Shelley comes back from the lawyer’s office and tells her, “Problem solved, honey. The lawyer told Foggi to get out of town.” Mary Shelley believes him and that’s what she writes to the Gisbornes.

We know Shelley was hiding his arrangements about Elena Adelaide from Mary. He sent money for Del Rosso to pay for “expenses in Naples,” via the Gisbornes, and he told them, “If it is necessary to write again on the subject of Del Rosso” to send a letter to the post office for “Mr. Jones” and he would pick it up there.

Livorno courthouse ceiling . So yes, Paolo Foggi complained and gossiped about Shelley but was he really the reason Shelley had to see Del Rosso at the end of June 1820?

Livorno courthouse ceiling . So yes, Paolo Foggi complained and gossiped about Shelley but was he really the reason Shelley had to see Del Rosso at the end of June 1820?In my forthcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman, I have given the Shelleys some information of their own with which to threaten Foggi, to get him to be quiet.

A year later, Shelley visited Lord Byron and Byron showed Shelley the letter from the Hoppners that he'd received eleven months before, detailing the rumours about Shelley and Claire and an abandoned baby. The result was two remarkable letters, one from Shelley to Mary and one from Mary Shelley to Mrs. Hoppner, which we’ll take a closer look at in the next post.

Next: “That my beloved Shelley should stand thus slandered!”

Shelley biographer Richard Holmes writes at length about the Elise/Claire/Elena Adelaide/Shelley mystery in his biography of Shelley and also in Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer.

*Actual timeline

May 1820 or earlier- Elise spills beans to Hoppners

June 1820 – Shelley receives letters from Paolo, threatening to spill the beans?

July 9, 1820 -- Elena Adelaide dies

Sept. 1820 – Hoppners tell Byron about the beans which were spilled

August 1821 – Shelley visits Byron and sees Hoppner letter

Previous posts in this series:

Shelley and the Mysterious Lady

Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Who was Elena Adelaide?

A Falsified Birth Certificate

What happened to Elena Adelaide?

Published on December 10, 2019 16:17

December 5, 2019

What happened to Elena Adelaide?

Young mother by Jules Breton Well, in a previous blog post in this series I already mentioned the sad fact that a little girl named Elena Adelaide died young in Naples in 1820. Her birth certificate said her father was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and who her mother was is something of a mystery. In fact we can't be positive that Shelley was the father. Everything else on the birth certificate is wrong -- he said the mother was his wife Mary Shelley, but he gave the wrong age, messed up the spelling of her name, and probably lied about the birth date as well.

Young mother by Jules Breton Well, in a previous blog post in this series I already mentioned the sad fact that a little girl named Elena Adelaide died young in Naples in 1820. Her birth certificate said her father was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and who her mother was is something of a mystery. In fact we can't be positive that Shelley was the father. Everything else on the birth certificate is wrong -- he said the mother was his wife Mary Shelley, but he gave the wrong age, messed up the spelling of her name, and probably lied about the birth date as well.The baby was left behind in Naples, fostered out to a local family in a working-class neighbourhood when the Shelleys moved away, after having spent the winter of 1818/1819 there.

It seems likely that Shelley really wanted to keep the child—the birth certificate proves that he was taking responsibility for the infant—and he had to improvise a solution and find another home for the baby when Mary Shelley refused. Mary Shelley's journal, which is usually very terse, notes there was “a most tremendous fuss” (her euphemism for a fight or a quarrel) when she and Shelley left Naples at the end of February 1819. As we have seen, Mary Shelley was not Elena's mother and it seems she did not have any emotional connection to the baby, otherwise the baby wouldn't have been left behind in Naples.

In June 1820, Shelley wrote that Elena was ill with “a severe fever of dentition. I suppose she will die, and leave another memory to those which already torture me. I am awaiting the next post with anxiety, but without much hope. What remains to me? Domestic peace and fame? You will laugh when you hear me talk of the latter…” Soon after came word of her death.

Shelley was not in Naples when the baby girl died. The death was reported to the authorities by a cheese-maker and a potter—working-class people. The address given for her was in a working-class section of Naples. There was no doctor's certificate, but a civil servant attested that he went to the home to see the dead child.

Her death did not necessarily come as a result of ill-treatment or neglect. High child mortality was a miserable fact of life in the days before vaccinations and public hygiene, and many children died young. Jane Austen's novels mention children dying and mothers dying in childbirth as a routine occurrence. This period of life was attended by much more anxiety than today. People of that time believed there was a connection between teething (dentition) and the fevers, illnesses and death of their children. The second summer of childhood, when the first molars emerge, was a time for catching measles, fevers, meningitis, typhoid. That's why my pioneer ancestors always breastfed past the second summer, to maintain the baby's immunity.

Mary Wollstonecraft On little Elena's death certificate, the names of the parents were given as "Bercy Schelly and Maria Gebuin, residents of Livorno."

Mary Wollstonecraft On little Elena's death certificate, the names of the parents were given as "Bercy Schelly and Maria Gebuin, residents of Livorno."Shelley was not present when this form was filled out. Scholars assume that “Gebuin” is another attempt at Godwin, Mary Shelley's maiden name. (see the previous post on Elena Adelaide's birth certificate and baptism certificate).

Livorno is where the Shelleys' friends, the Gisbornes, lived. (Shelley and Mary lived in Pisa.) Maria Gisborne was a friend of the Godwin family. In fact William Godwin, Mary Shelley's father proposed marriage to her after Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin died. She turned him down.

When Percy and Mary Shelley moved to Italy with their two children, they met up with the Gisbornes and it was a great comfort to Mary Shelley to have a loving, motherly figure like Maria Gisborne who had known her when she was a motherless infant.

"Gebuin” is at least as close to “Gisborne” as “Godwin.”

Neapolitan cheese vendor The names on the death certificate were supplied by the cheese-maker or the potter. One of them was probably Elena Adelaide's foster father. They had probably met Percy Shelley when he made his arrangements for the baby's care, but not Mary Shelley, and certainly they didn't know Maria Gisborne of Livorno. So they got their information from Percy Shelley.

Neapolitan cheese vendor The names on the death certificate were supplied by the cheese-maker or the potter. One of them was probably Elena Adelaide's foster father. They had probably met Percy Shelley when he made his arrangements for the baby's care, but not Mary Shelley, and certainly they didn't know Maria Gisborne of Livorno. So they got their information from Percy Shelley. Putting Maria Gisborne down as the parent on the death certificate is not to suggest that Shelley had an affair with Maria Gisborne. My theory is that Shelley provided the name “Maria Gisborne of Livorno” to the foster family as a person to contact if necessary. Another person involved in caring for Elena Adelaide also lived in Livorno, a lawyer named Del Rosso. He was the Gisbornes' lawyer as well.

I think Shelley gave Maria Gisborne's name to the Neapolitan foster family as a form of insurance; in the event of his own death—and he often believed he was near death—Elena's caregivers would have someone to contact concerning Elena. (As it happened, he survived Elena, but not for long.) He involved the Gisbornes in the banking and legal arrangements he made for the baby and mentioned her in letters to them. The letter about teething, mentioned above, that Shelley wrote shortly before Elena Adelaide's death, was written to Maria Gisborne.

Maria Gisborne, however, was more of a friend of Mary Shelley's than Percy, given her long friendship with the Godwin family. She would have wanted an explanation for why Percy Shelley was taking care of a baby whom he called his "ward."

I hypothesise that Shelley told the Gisbornes who Elena Adelaide's mother really was, or at least he told Maria Gisborne (Mr. Gisborne was seen by the Shelleys as being a bit dim-witted). That's one of the scenes in my upcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman.

In addition to his sorrow over the loss of Elena Adelaide, the mysterious events of that winter in Naples would come back to haunt Percy Shelley in other ways. Next post: Paolo Foggi, "that superlative rascal"

Previous posts in this series:

Shelley and the Mysterious Lady

Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Who was Elena Adelaide?

A Falsified Birth Certificate

Published on December 05, 2019 09:23

December 1, 2019

A Falsified Birth Certificate

There is an

enduring literary mystery

around Percy Bysshe Shelley and a baby girl born in Naples in the winter of 1818/19. The date on the birth certificate – December 27 – does not agree with the age given on her death certificate.

On both documents, the father of the child is given as Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley took financial responsibility for little Elena Adelaide even though she never lived with Percy and his wife Mary.

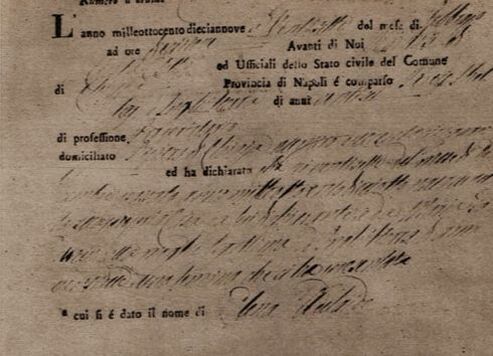

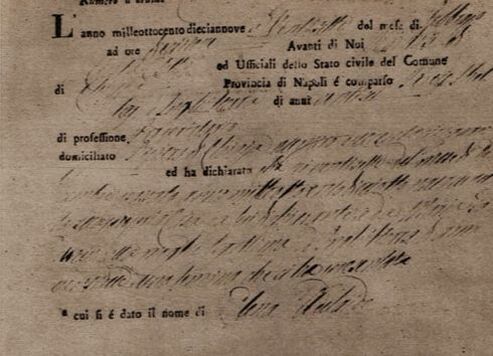

The birth certificate, retrieved from the Neapolitan archives in the 1930’s, is reproduced here. You can just make out the name "Elena Adelaide" at the bottom in this image with an elaborately drawn "E" and "A" and "d" Detail of Elena Adelaide's birth certificate Unfortunately the writing in this reproduction, taken from N.I. White's 1940 biography of Shelley, is very faint, but we are told that the mother's name is given as “Marina Padurin.’ You can see the large swoop-down of the letter "M" on the fourth line from the bottom.

Detail of Elena Adelaide's birth certificate Unfortunately the writing in this reproduction, taken from N.I. White's 1940 biography of Shelley, is very faint, but we are told that the mother's name is given as “Marina Padurin.’ You can see the large swoop-down of the letter "M" on the fourth line from the bottom.

Ivan Roe, writing in 1955, said that “Godwin” has been misread as “Padurin,” “a slip resulting from unfamiliarity with the Italian script used in the certificate."

Yet subsequently, many biographers have reported that the name is given as “Marina (or Maria or Mary) Padurin.” Padurin is a Russian surname and no-one has suggested a Shelley connection to this name.

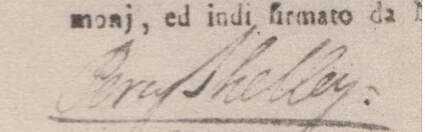

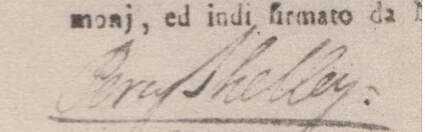

Even though it is agreed that Mary Godwin Shelley could not be the mother of Elena Adelaide and may even have been kept in the dark about Shelley claiming paternity for the child, many scholars have assumed that Shelley intended to give his wife's maiden name for the birth certificate. Shelley's signature on the birth certificate Shelley biographer Richard Holmes thinks “Padurin” is a “phonetic rendering” of “Godwin.” Biographer James Bieri also thinks the clerk must have mis-heard “Godwin” as “Padurin,” that is, mis-heard a two-syllable name as a three-syllable one, and likewise mis-heard 'p' for 'g', 'd' for 'w' and inserted an 'r' where there was none. I am not convinced of this explanation and it is certainly a slur against the capabilities of 19th-century Italian civil servants.

Shelley's signature on the birth certificate Shelley biographer Richard Holmes thinks “Padurin” is a “phonetic rendering” of “Godwin.” Biographer James Bieri also thinks the clerk must have mis-heard “Godwin” as “Padurin,” that is, mis-heard a two-syllable name as a three-syllable one, and likewise mis-heard 'p' for 'g', 'd' for 'w' and inserted an 'r' where there was none. I am not convinced of this explanation and it is certainly a slur against the capabilities of 19th-century Italian civil servants.

Shelley spoke Italian and was standing right in front of the registrar, giving him the information. His signature appears on the birth certificate. So if he meant "Godwin," why did he say "Padurin" or allow the clerk to write "Padurin"?

And if he meant to give his wife Mary as the mother, why did he give the wrong age? Why was the mother’s age given as 27 when Mary Shelley was 21 at the time? Beatrice Cenci Mary Shelley biographer Emily W. Sunstein suggests “Padurin” should be “Paterin,” which is the name given to an obscure medieval Christian sect that Mary Shelley was researching around that time, planning to use them in one of her novels.

Beatrice Cenci Mary Shelley biographer Emily W. Sunstein suggests “Padurin” should be “Paterin,” which is the name given to an obscure medieval Christian sect that Mary Shelley was researching around that time, planning to use them in one of her novels.

I have my own fanciful explanation, which I think is as plausible as claiming that Padurin is a phonetic rendering of Godwin. “Padurin” should be “Pandurin,” a combination of Pandemos and Uranus, a combination of the different types of love described by Plato, which Shelley had been studying and translating the previous year. Only one letter is missing. Shelley had a lifelong habit of bestowing nicknames on his friends and family members.

However, it must be acknowledged that there is also a baptism certificate which apparently lists the mother as "Mary Godwin." Shelley took the baby to the church in the Parish of St. Joseph where she was baptised, presumably as a Catholic. The baptism certificate says the baby was "lawfully begotten," that is, Elena Adelaide is the daughter of Percy Shelley and his wife, which we know cannot be true, at least as far as Mary is concerned. The baby was baptised on February 27th, the same day that Percy Shelley went to the registrar and registered the birth.

Elena Adelaide was listed as being fifteen months and twelve days old when she died on June 9th, 1820, which would place her birth at the end of February, and Shelley registered her birth at the end of February, but said she was born on December 27th. Did he, in addition to lying about the mother, lie about her date of birth?

James Bieri suggests that “Shelley possibly selected December 27 as the child's birth date in order to conceal association with its actual mother.” A child due in February would have been conceived in the summer, when Shelley spent some time apart from his wife. A child born in December would have been conceived the previous spring, which would have been an alibi for Shelley, because he was living with his wife at the time.

We know from their journals that a doctor came to the Shelley’s house to see Claire on December 27th and that she had been having unspecified health problems through the previous fall.

And Richard Holmes points to a reference to December 27th as an important date in Shelley’s tragic verse play, The Cenci , a date singled out with “transparent bitterness.” The evil Count gloats as he announces the death of two of his rebellious sons:

All in the self-same hour of the same night

Which shows that heaven has special care for me

I beg those friends who love me, that they mark

The day a feast upon their calendars.

It was the twenty-seventh of December.

It is as though the date has special dark significance for Shelley.

And again, the number "27" is reported as the mother’s age on the birth certificate. Neither Mary Shelley, nor her sister Claire Clairmont, nor the nursemaid Elise, who was pregnant that winter, were 27 years old. Perhaps Elena Adelaide's real mother, whoever she was, was 27 years old.

Next: Who was Elena Adelaide's mother? I have a candidate in my upcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman.

(PS, warning, the true story of Beatrice Cenci is very tragic, so don't read about her if you don't want to feel very sad.) Previous posts in this series:

Shelley and the Mysterious Lady

Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Who was Elena Adelaide?

On both documents, the father of the child is given as Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley took financial responsibility for little Elena Adelaide even though she never lived with Percy and his wife Mary.

The birth certificate, retrieved from the Neapolitan archives in the 1930’s, is reproduced here. You can just make out the name "Elena Adelaide" at the bottom in this image with an elaborately drawn "E" and "A" and "d"

Detail of Elena Adelaide's birth certificate Unfortunately the writing in this reproduction, taken from N.I. White's 1940 biography of Shelley, is very faint, but we are told that the mother's name is given as “Marina Padurin.’ You can see the large swoop-down of the letter "M" on the fourth line from the bottom.

Detail of Elena Adelaide's birth certificate Unfortunately the writing in this reproduction, taken from N.I. White's 1940 biography of Shelley, is very faint, but we are told that the mother's name is given as “Marina Padurin.’ You can see the large swoop-down of the letter "M" on the fourth line from the bottom.Ivan Roe, writing in 1955, said that “Godwin” has been misread as “Padurin,” “a slip resulting from unfamiliarity with the Italian script used in the certificate."

Yet subsequently, many biographers have reported that the name is given as “Marina (or Maria or Mary) Padurin.” Padurin is a Russian surname and no-one has suggested a Shelley connection to this name.

Even though it is agreed that Mary Godwin Shelley could not be the mother of Elena Adelaide and may even have been kept in the dark about Shelley claiming paternity for the child, many scholars have assumed that Shelley intended to give his wife's maiden name for the birth certificate.

Shelley's signature on the birth certificate Shelley biographer Richard Holmes thinks “Padurin” is a “phonetic rendering” of “Godwin.” Biographer James Bieri also thinks the clerk must have mis-heard “Godwin” as “Padurin,” that is, mis-heard a two-syllable name as a three-syllable one, and likewise mis-heard 'p' for 'g', 'd' for 'w' and inserted an 'r' where there was none. I am not convinced of this explanation and it is certainly a slur against the capabilities of 19th-century Italian civil servants.

Shelley's signature on the birth certificate Shelley biographer Richard Holmes thinks “Padurin” is a “phonetic rendering” of “Godwin.” Biographer James Bieri also thinks the clerk must have mis-heard “Godwin” as “Padurin,” that is, mis-heard a two-syllable name as a three-syllable one, and likewise mis-heard 'p' for 'g', 'd' for 'w' and inserted an 'r' where there was none. I am not convinced of this explanation and it is certainly a slur against the capabilities of 19th-century Italian civil servants.Shelley spoke Italian and was standing right in front of the registrar, giving him the information. His signature appears on the birth certificate. So if he meant "Godwin," why did he say "Padurin" or allow the clerk to write "Padurin"?

And if he meant to give his wife Mary as the mother, why did he give the wrong age? Why was the mother’s age given as 27 when Mary Shelley was 21 at the time?

Beatrice Cenci Mary Shelley biographer Emily W. Sunstein suggests “Padurin” should be “Paterin,” which is the name given to an obscure medieval Christian sect that Mary Shelley was researching around that time, planning to use them in one of her novels.

Beatrice Cenci Mary Shelley biographer Emily W. Sunstein suggests “Padurin” should be “Paterin,” which is the name given to an obscure medieval Christian sect that Mary Shelley was researching around that time, planning to use them in one of her novels. I have my own fanciful explanation, which I think is as plausible as claiming that Padurin is a phonetic rendering of Godwin. “Padurin” should be “Pandurin,” a combination of Pandemos and Uranus, a combination of the different types of love described by Plato, which Shelley had been studying and translating the previous year. Only one letter is missing. Shelley had a lifelong habit of bestowing nicknames on his friends and family members.

However, it must be acknowledged that there is also a baptism certificate which apparently lists the mother as "Mary Godwin." Shelley took the baby to the church in the Parish of St. Joseph where she was baptised, presumably as a Catholic. The baptism certificate says the baby was "lawfully begotten," that is, Elena Adelaide is the daughter of Percy Shelley and his wife, which we know cannot be true, at least as far as Mary is concerned. The baby was baptised on February 27th, the same day that Percy Shelley went to the registrar and registered the birth.

Elena Adelaide was listed as being fifteen months and twelve days old when she died on June 9th, 1820, which would place her birth at the end of February, and Shelley registered her birth at the end of February, but said she was born on December 27th. Did he, in addition to lying about the mother, lie about her date of birth?

James Bieri suggests that “Shelley possibly selected December 27 as the child's birth date in order to conceal association with its actual mother.” A child due in February would have been conceived in the summer, when Shelley spent some time apart from his wife. A child born in December would have been conceived the previous spring, which would have been an alibi for Shelley, because he was living with his wife at the time.

We know from their journals that a doctor came to the Shelley’s house to see Claire on December 27th and that she had been having unspecified health problems through the previous fall.

And Richard Holmes points to a reference to December 27th as an important date in Shelley’s tragic verse play, The Cenci , a date singled out with “transparent bitterness.” The evil Count gloats as he announces the death of two of his rebellious sons:

All in the self-same hour of the same night

Which shows that heaven has special care for me

I beg those friends who love me, that they mark

The day a feast upon their calendars.

It was the twenty-seventh of December.

It is as though the date has special dark significance for Shelley.

And again, the number "27" is reported as the mother’s age on the birth certificate. Neither Mary Shelley, nor her sister Claire Clairmont, nor the nursemaid Elise, who was pregnant that winter, were 27 years old. Perhaps Elena Adelaide's real mother, whoever she was, was 27 years old.

Next: Who was Elena Adelaide's mother? I have a candidate in my upcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman.

(PS, warning, the true story of Beatrice Cenci is very tragic, so don't read about her if you don't want to feel very sad.) Previous posts in this series:

Shelley and the Mysterious Lady

Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Who was Elena Adelaide?

Published on December 01, 2019 19:43

November 20, 2019

Who was Elena Adelaide?

As I discussed in the first blog post in this series about Percy Bysshe Shelley, he told his cousin and Lord Byron that he'd been pursued by a beautiful lady. Here is a synopsis from an early biography:

"According to the account which Shelley gave to Byron and Medwin, he re-encountered in Naples the married lady who had proffered her love to him in 1816. She... informed him of the persistent though hopeless affection with which she had tracked his footsteps." -- A Memoir of Shelley, by William Michael Rossetti, (1886) Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder Whether or not there really was a mysterious lady, there was a mysterious baby girl.

Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder Whether or not there really was a mysterious lady, there was a mysterious baby girl.

Something—nobody knows what exactly—happened in Naples in the winter of 1818 concerning Shelley and a baby girl. There is some question about how much of the whole story Mary Shelley ever knew, and she later suppressed the few details that were available.

During the winter of 1818/19 Shelley was living in Naples with his wife (Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein,) his wife's step-sister Claire, who was possibly pregnant, and a pregnant nursemaid. By the time he left Naples in February, he had taken financial responsibility for a new-born baby girl.

Until 1936, Shelley scholars had no information about the identity and even the confirmed existence of the little girl that Shelley referred to in a few surviving letters as his 'Neapolitan ward.'

Academics surmised that this ward was a foundling whom Shelley impulsively adopted to soothe this wife after the loss of their daughter Clara. Throughout his life, Shelley had strong impulses to “rescue” girls, so buying or otherwise obtaining an attractive Italian infant would not have been out of character for him. However, the baby Elena Adelaide did not become part of the family and was left behind in Naples, where she was evidently left with a working-class Neapolitan family.

The child remained “a vague wraith” (in the words of scholar Richard D. Altick) until Shelley biographer Newman Ivey White and an Italian professor combed through the Neapolitan archives and found a birth certificate for Elena Adelaide, listing Percy Bysshe Shelley as the father, and the mother as one “Marina Padurin.” We'll return to that name Marina Padurin later. There was also a baptism certificate, again stating that Percy Shelley was the father and the mother was his wife, Mary Godwin (which was, of course, Mary's maiden name). Also, sadly, there is a death certificate, for Elena Adelaide, like three other children associated with this family, died very young in Italy. Shelley registered the child's birth and baptism with the authorities, and he did so the night before he left Naples with Mary and Claire, leaving the baby behind.

Shelley registered the child's birth and baptism with the authorities, and he did so the night before he left Naples with Mary and Claire, leaving the baby behind.

The parentage of Elena Adelaide is a mystery, and there are several theories, but wide agreement that Mary Shelley was not the mother of the child. She wasn't pregnant that winter. There is no record of her giving birth, and obviously, she wouldn't leave Naples and leave her new-born child behind to be raised by a foster family. So, if the documents claimed that Mary Shelley was the mother, the documents are false. It is possible that Mary Shelley didn't even know about these documents. However, Mary's journal records that she and Shelley had a "most tremendous fuss" when they left Naples. That was Mary's euphemism for a fight.

So who were Elena Adelaide's parents. Was Shelley really the father? Who was the mother? Was it Claire? Was it the nurse-maid Elise? Was it the mysterious lady ?

\Next blog post, we'll take a closer look at the birth certificate

.

[1] page 104, Richard D. Altick, The Scholar Adventurers, Ohio State University Press, 1987. Post one: Shelley and the mysterious lady

Post two: Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

Post three: In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

"According to the account which Shelley gave to Byron and Medwin, he re-encountered in Naples the married lady who had proffered her love to him in 1816. She... informed him of the persistent though hopeless affection with which she had tracked his footsteps." -- A Memoir of Shelley, by William Michael Rossetti, (1886)

Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder Whether or not there really was a mysterious lady, there was a mysterious baby girl.

Photo credit: Wolfgang Moroder Whether or not there really was a mysterious lady, there was a mysterious baby girl.Something—nobody knows what exactly—happened in Naples in the winter of 1818 concerning Shelley and a baby girl. There is some question about how much of the whole story Mary Shelley ever knew, and she later suppressed the few details that were available.

During the winter of 1818/19 Shelley was living in Naples with his wife (Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein,) his wife's step-sister Claire, who was possibly pregnant, and a pregnant nursemaid. By the time he left Naples in February, he had taken financial responsibility for a new-born baby girl.

Until 1936, Shelley scholars had no information about the identity and even the confirmed existence of the little girl that Shelley referred to in a few surviving letters as his 'Neapolitan ward.'

Academics surmised that this ward was a foundling whom Shelley impulsively adopted to soothe this wife after the loss of their daughter Clara. Throughout his life, Shelley had strong impulses to “rescue” girls, so buying or otherwise obtaining an attractive Italian infant would not have been out of character for him. However, the baby Elena Adelaide did not become part of the family and was left behind in Naples, where she was evidently left with a working-class Neapolitan family.

The child remained “a vague wraith” (in the words of scholar Richard D. Altick) until Shelley biographer Newman Ivey White and an Italian professor combed through the Neapolitan archives and found a birth certificate for Elena Adelaide, listing Percy Bysshe Shelley as the father, and the mother as one “Marina Padurin.” We'll return to that name Marina Padurin later. There was also a baptism certificate, again stating that Percy Shelley was the father and the mother was his wife, Mary Godwin (which was, of course, Mary's maiden name). Also, sadly, there is a death certificate, for Elena Adelaide, like three other children associated with this family, died very young in Italy.

Shelley registered the child's birth and baptism with the authorities, and he did so the night before he left Naples with Mary and Claire, leaving the baby behind.

Shelley registered the child's birth and baptism with the authorities, and he did so the night before he left Naples with Mary and Claire, leaving the baby behind.The parentage of Elena Adelaide is a mystery, and there are several theories, but wide agreement that Mary Shelley was not the mother of the child. She wasn't pregnant that winter. There is no record of her giving birth, and obviously, she wouldn't leave Naples and leave her new-born child behind to be raised by a foster family. So, if the documents claimed that Mary Shelley was the mother, the documents are false. It is possible that Mary Shelley didn't even know about these documents. However, Mary's journal records that she and Shelley had a "most tremendous fuss" when they left Naples. That was Mary's euphemism for a fight.

So who were Elena Adelaide's parents. Was Shelley really the father? Who was the mother? Was it Claire? Was it the nurse-maid Elise? Was it the mysterious lady ?

\Next blog post, we'll take a closer look at the birth certificate

.

[1] page 104, Richard D. Altick, The Scholar Adventurers, Ohio State University Press, 1987. Post one: Shelley and the mysterious lady

Post two: Shelley: Pursued or Pursuer?

Post three: In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

Published on November 20, 2019 15:54

November 19, 2019

In the Deep Wide Sea of Misery

This is the third in a series of blog posts about some autobiographical mysteries in the life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, which I make use of in my forthcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman.

After traipsing around Italy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairmont rented a villa in the spa town of Bagni di Lucca in the summer of 1818. They lived there with their little son, baby daughter, and some servants. This was a very young household: Mary Shelley was 20, her husband a few years older.

After traipsing around Italy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairmont rented a villa in the spa town of Bagni di Lucca in the summer of 1818. They lived there with their little son, baby daughter, and some servants. This was a very young household: Mary Shelley was 20, her husband a few years older.

In mid-August, Shelley and Claire abruptly left for Venice. Claire was anxious to see her little daughter Allegra, the result of a brief and one-sided fling with Lord Byron.

Claire had unhappily and unwillingly given custody of the baby to Byron. She was essentially destitute, he was rich; she was obscure, he was famous, she trusted he could give the child a better life and she was grateful he acknowledged paternity. Mary Shelley generously gave up her children’s Swiss nurse-maid so Allegra could have a familiar face taking care of her when she was sent to a father she'd never known.

Shelley biographers state that Claire insisted on going to Venice because the Shelleys had received alarming letters from the nurse-maid, advising them that Byron had casually handed off Allegra to the British consul-general and his wife, while he was busy debauching himself all over Venice.

Once in Venice, Shelley wrote to Mary and asked her: "Well tell me, dearest Mary, are you very lonely?.... What acquaintances have you made?” In fact, the Shelleys deliberately hung back from making new acquaintances. They held Italians in contempt and didn't think much better of their fellow English tourists. The feeling was mutual: because the Shelleys were non-conformists and Shelley was an avowed atheist, respectable people shunned them. The modern equivalent would be socialist vegans setting up a small commune in some middle-class community, with rumours going around that they practised free love.

Did Shelley ask Mary about new acquaintances because he was worried she was lonely in his absence, or was he worried that she might meet someone he didn’t want her to meet? Lord George Byron Three days later, Shelley wrote to Mary Shelley again and told her to leave Bagni di Lucca and come to him immediately because Byron offered to let them live in his country villa in Este, and he would permit Allegra to come visit with them there. Mary complied, even though their baby girl was ill.

Lord George Byron Three days later, Shelley wrote to Mary Shelley again and told her to leave Bagni di Lucca and come to him immediately because Byron offered to let them live in his country villa in Este, and he would permit Allegra to come visit with them there. Mary complied, even though their baby girl was ill.

Picture a six days' journey in a carriage, with no air-conditioning, on rough roads, in Italy in August with a very sick baby.

Some historians have explained that Shelley needed to get Mary to Este in a hurry because Claire was desperate to spend time with baby Allegra, but Byron wouldn't let the child visit with Claire unless Mary Shelley was also in residence. But while Mary was making her arduous and miserable journey, Shelley admitted to Byron that Mary was not with him, as he had implied, rendering that hasty and miserable journey unnecessary.

It's odd, anyway, that Mary's presence was so crucial because Byron thought the Shelleys were abysmally poor parents who half-starved their children. Would a week or more have made such a difference? Why was Shelley so insistent on hurrying?

Poor baby Clara contracted dysentery. She survived the six day trip to Este, but was very weak.

A few weeks later Shelley left Mary behind again and went to Padua with Claire, ostensibly in search of a good doctor for her. He wrote to Mary and ordered her to bring the baby to Padua. Then they went on to Venice, to consult Lord Byron's doctor. The baby did not survive the trip. She died in her mother's arms.

What accounts for Shelley's urgent insistence that Mary come from Bagni di Lucca immediately, despite little Clara being ill?

I provide a new answer in my forthcoming novel, A Different Kind of Woman. Post one: Shelley and the mysterious lady

Post two: Shelley--pursued or pursuer?

After traipsing around Italy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairmont rented a villa in the spa town of Bagni di Lucca in the summer of 1818. They lived there with their little son, baby daughter, and some servants. This was a very young household: Mary Shelley was 20, her husband a few years older.

After traipsing around Italy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her step-sister Claire Clairmont rented a villa in the spa town of Bagni di Lucca in the summer of 1818. They lived there with their little son, baby daughter, and some servants. This was a very young household: Mary Shelley was 20, her husband a few years older.In mid-August, Shelley and Claire abruptly left for Venice. Claire was anxious to see her little daughter Allegra, the result of a brief and one-sided fling with Lord Byron.

Claire had unhappily and unwillingly given custody of the baby to Byron. She was essentially destitute, he was rich; she was obscure, he was famous, she trusted he could give the child a better life and she was grateful he acknowledged paternity. Mary Shelley generously gave up her children’s Swiss nurse-maid so Allegra could have a familiar face taking care of her when she was sent to a father she'd never known.

Shelley biographers state that Claire insisted on going to Venice because the Shelleys had received alarming letters from the nurse-maid, advising them that Byron had casually handed off Allegra to the British consul-general and his wife, while he was busy debauching himself all over Venice.

Once in Venice, Shelley wrote to Mary and asked her: "Well tell me, dearest Mary, are you very lonely?.... What acquaintances have you made?” In fact, the Shelleys deliberately hung back from making new acquaintances. They held Italians in contempt and didn't think much better of their fellow English tourists. The feeling was mutual: because the Shelleys were non-conformists and Shelley was an avowed atheist, respectable people shunned them. The modern equivalent would be socialist vegans setting up a small commune in some middle-class community, with rumours going around that they practised free love.

Did Shelley ask Mary about new acquaintances because he was worried she was lonely in his absence, or was he worried that she might meet someone he didn’t want her to meet?