Lona Manning's Blog, page 25

December 9, 2020

CMP#18 Not in front of the servants

Implicit values in Austen: Not in front of the servants

Implicit values in Austen: Not in front of the servants  “The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma sat down to think and be miserable.” -- Jane Austen, Emma In my previous post, I talked about how servants were a fact of life for Jane Austen, and looked at how she used them in her novels. Here I look at the reality of living with servants.

“The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma sat down to think and be miserable.” -- Jane Austen, Emma In my previous post, I talked about how servants were a fact of life for Jane Austen, and looked at how she used them in her novels. Here I look at the reality of living with servants. The gentry literally could not function without servants. They were a vast and silent army. At least one in ten and probably more people worked as servants in Austen’s time. If you went on vacation, you took your servants with you.

How did John and Isabella Knightley and their five children and their servants get to Hartfield with only one carriage? They didn’t. The servants and some of the children went by coach and were met somewhere between London and Hartfield by Mr. Woodhouse’s carriage and driver, who brought them the rest of the way. Austen actually clears up this little detail:

Mr. Woodhouse "thought much of the evils of the journey for [Isabella], and not a little of the fatigues of his own horses and coachman who were to bring some of the party the last half of the way; but his alarms were needless; the sixteen miles being happily accomplished, and Mr. and Mrs. John Knightley, their five children, and a competent number of nursery-maids, all reaching Hartfield in safety." In Austen Years: A Memoir in Five Novels, Rachel Cohen notes that in Austen, many important conversations are had, and many resolutions occur, when the characters are walking outside.

Since Austen’s characters share their homes with servants, it’s not surprising that they resort to country lanes and shrubberies for important conversations.

We learn from Austen that it is vulgar to talk in front of the servants, or to make them into your confidantes. Vulgar, good-natured Mrs. Jennings gossips with her maid when there is no-one else to talk with.

We learn from Austen that it is vulgar to talk in front of the servants, or to make them into your confidantes. Vulgar, good-natured Mrs. Jennings gossips with her maid when there is no-one else to talk with. Lydia Bennet is also someone who disregards this rule, both at home and abroad:

“Now I have got some news for you,” said Lydia, as [the sisters] sat down at table [at the inn]. “What do you think? It is excellent news—capital news—and about a certain person we all like!”

Jane and Elizabeth looked at each other, and the waiter was told he need not stay. Lydia laughed, and said:

“Aye, that is just like your formality and discretion. You thought the waiter must not hear, as if he cared! I dare say he often hears worse things said than I am going to say. But he is an ugly fellow! I am glad he is gone. I never saw such a long chin in my life."

Later, after Elizabeth reads Lydia's letter about her elopement with Wickham, she exclaims, “Oh! thoughtless, thoughtless Lydia..." And soon she wonders, “was there a servant belonging to it who did not know the whole story before the end of the day?”

“I do not know. [answers Jane]. "I hope there was. But to be guarded at such a time is very difficult. My mother was in hysterics... "

Letter from Mr. Gardiner It is soon made clear that all the servants know about the scandal, of course, with Mr. Bennet leaving for London and returning empty-handed, and Mrs. Bennet lying prostrate in her bedchamber.

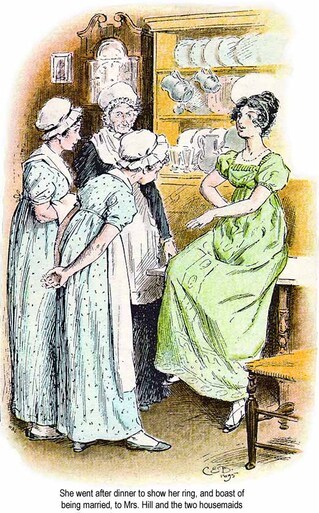

Letter from Mr. Gardiner It is soon made clear that all the servants know about the scandal, of course, with Mr. Bennet leaving for London and returning empty-handed, and Mrs. Bennet lying prostrate in her bedchamber.After several days of anxiety, Mrs. Hill, the housekeeper, can't refrain from asking Jane and Elizabeth: “I beg your pardon, madam, for interrupting you, but I was in hopes you might have got some good news from town, so I took the liberty of coming to ask.”

She uses that apologetic phrase, "taking the liberty," to excuse herself for asking about the family's personal life. The girls are so excited to hear that an express letter has arrived from town, that they run to look for their father, "too eager... to have time for speech."

The butler sees them running from room to room, guesses what they are doing, and says, “If you are looking for my master, ma’am, he is walking towards the little copse.” [And because we think of the Bennets as poor, as people who should be economizing for the future, are we surprised that their household includes a butler?]

Back outside the girls go, to have their private conversation with their father in the open air, and go over the amazing news in the letter -- Lydia and Mr. Wickham have been found, and they are to marry.

The good news of Lydia's impending marriage to "one of the most worthless young men in Great Britain" means that the family can tell the servants and the entire neighbourhood. "Oh! Here comes Hill!" exclaims Mrs. Bennet. "My dear Hill, have you heard the good news? Miss Lydia is going to be married; and you shall all have a bowl of punch to make merry at her wedding.” Hardly any of us, certainly not me, knows what it would be like to share your house with servants. You can’t undress yourself and get yourself ready for bed without their help. You try not to cry until they are “sent away.” Leaving a mess behind in your hotel room for a hotel cleaner who will never see you again, is not to be compared with the intimacy of living together with someone who empties your chamber pots and knows when you’re having your period. As we've seen, you don’t want to discuss sensitive family matters in their hearing.

And of course, it's hard to have an affair or elope with servants around. Lydia managed to run away with Wickham, but the "want of common discretion, of caution" exposed Henry Crawford's dalliance with Maria Bertram. Maria put "herself in the power" of her mother-in-law's servant.

Lack of discretion also ruined Colonel Brandon's planned elopement with Eliza, the girl he loved. "We were within a few hours of eloping together for Scotland," he tells Elinor. "The treachery, or the folly, of my cousin's maid betrayed us."

Mrs. Yonge, Georgiana Darcy's governess, is actually an accomplice in Wickham's plans to elope with the young heiress -- another rare example of a servant showing agency in Austen's novels, although fortunately the plot is foiled. Mrs. Yonge, although important to the plot, never appears in person in Pride & Prejudice.

Upright Anne Elliot in Persuasion would never have eloped with anyone, and she wouldn't have put herself in the power of a servant, either. There is no mention of Anne having a lady's maid. She doesn't seem to pay much attention to servants. Her friend Mrs. Smith asks her, ‘Did you observe the woman who opened the door to you, when you called yesterday?’

Anne has no idea. "No. Was not it Mrs. Speed, as usual, or the maid? I observed no one in particular."

Servants are impossible to ignore in modern filmed adaptations of Austen novels.

Servants are impossible to ignore in modern filmed adaptations of Austen novels.The Muse and Hearth podcast comments that the servants are “visible at every turn, they’re almost distracting from the main characters" in the latest movie version of Emma. Footman stand at attention in the parlor, rather than out in the corridor, hearing every word that passes. Mr. Knightley strides around naked in front of his valet. Emma imperiously directs the servants with wordless little gestures.

The movie turns Mr. Woodhouse's gentle selfishness into tyranny for comic effect -- but also to make a social statement.

Mr. Elton unveils Harriet's portrait and flings the covering at a servant without turning around. She is startled, but she catches it. The moment is a comic one but it also serves to reinforce our ideas about how servants were treated in the past.

As Muse and Hearth remark, there is nothing wrong with making a movie that portrays the servants as real characters who intrude on the story and react to the action, but the fact is, this is not how Austen portrays servants. This interpretation strays a bit from Austen. Next post: What happened to all the servants? Paolo Foggi, Percy Bysshe Shelley's real-life servant from history, appears in my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady. He turns from being an ingratiating servant to wanting to get his revenge. Click here for more about Shelley and the Unknown Lady, which will be on special promotion next week.

Published on December 09, 2020 00:00

December 6, 2020

CMP#17 Servants in Austen's Novels

Implicit Facts in Austen: Servants in the background "There was certainly at this moment, in Elizabeth’s mind, a more gentle sensation towards [Mr. Darcy] than she had ever felt at the height of their acquaintance. The commendation bestowed on him by Mrs. Reynolds was of no trifling nature. What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?" -- Pride & Prejudice

Implicit Facts in Austen: Servants in the background "There was certainly at this moment, in Elizabeth’s mind, a more gentle sensation towards [Mr. Darcy] than she had ever felt at the height of their acquaintance. The commendation bestowed on him by Mrs. Reynolds was of no trifling nature. What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?" -- Pride & Prejudice

"Do We Ever See the Lower Classes?" In discussing servants, it is tempting to repeat everything John Mullan says in his excellent book, "What Matters in Jane Austen?" and cite every example he cites. Once you start looking, there are dozens of references to servants in A Austen. Although we learn the names of some of them -- Mrs. Reynolds the housekeeper at Pemberley, Wilcox the coachman in Mansfield Park -- usually they’re nameless and silent. When Henry Crawford returns to Mansfield Parsonage after visiting his uncle, he brings at least two servants with him, possibly more. We just get a glimpse of them as they push Henry’s carriage into the stables.

"Do We Ever See the Lower Classes?" In discussing servants, it is tempting to repeat everything John Mullan says in his excellent book, "What Matters in Jane Austen?" and cite every example he cites. Once you start looking, there are dozens of references to servants in A Austen. Although we learn the names of some of them -- Mrs. Reynolds the housekeeper at Pemberley, Wilcox the coachman in Mansfield Park -- usually they’re nameless and silent. When Henry Crawford returns to Mansfield Parsonage after visiting his uncle, he brings at least two servants with him, possibly more. We just get a glimpse of them as they push Henry’s carriage into the stables.Frank Churchill evidently brings several horses and at least one manservant on one of his visits to Highbury. After concluding his visit, Austen wrote: “The pleasantness of the morning had induced him to walk forward, and leave his horses to meet him by another road, a mile or two beyond Highbury.” His horses could hardly arrange to meet him by themselves, so there must be a groom looking after them. The horses are mentioned, the servant isn’t.

Pamela, the titular heroine of Samuel Richardson's influential 1740 novel, was a servant-girl who marries her master. The brief appearance by Mrs. Reynolds in Pride & Prejudice is a significant one, because her endorsement of Mr. Darcy as "the best landlord, and the best master," helps Elizabeth realize how much she's misjudged him. But this is an exception. Servants seldom speak in Austen, and they are used, as we will see, for narrative purposes.

Pamela, the titular heroine of Samuel Richardson's influential 1740 novel, was a servant-girl who marries her master. The brief appearance by Mrs. Reynolds in Pride & Prejudice is a significant one, because her endorsement of Mr. Darcy as "the best landlord, and the best master," helps Elizabeth realize how much she's misjudged him. But this is an exception. Servants seldom speak in Austen, and they are used, as we will see, for narrative purposes. It would be easy to assume that Austen didn't focus on servants because a) either she wasn't interested in servants or b) her readers weren't interested in servants.

In her private life, Austen did mention the family servants in her letters; they were part of the household. When she visited her rich brother at his grand estate, she met and befriended her brother's governess. She left a gift of fifty pounds to her brother Henry's servant in her will.

What about (b)? Is it true that Austen's readers didn't want to hear about the servants? Well, actually, servants made frequent appearances in English literature and drama. Servants are essential as messengers such as Juliet's Nurse, but they also provide comic relief, and sometimes comment on the shortcomings of their masters and mistresses.

In Lover's Vows, the play that the young people plan to perform in Mansfield Park, Tom Bertram plays a comical butler who can't resist reciting poetry. When Elizabeth Inchbold translated the play from the German, she enlarged the butler's part. Laurence Stern's extremely popular novel, Tristram Shandy, features Susan the chambermaid and Corporal Trim, servant to Uncle Toby. Pamela: or Virtue Rewarded, which was a huge hit with the public, is about an ordinary servant girl who resists her master's advances. He ends up offering her marriage. Teague, "a blundering and bewildered, hard-drinking but loyal Irish footman... regularly featured in various literary formats well into the nineteenth century," according to scholar Patricia Godsave.

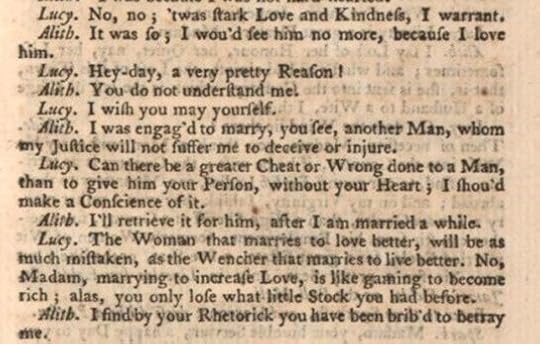

Servants weren't always stupid, they could be shrewd. There was nothing uncommon in portraying a servant as wiser and more ingenious than their master and mistress, especially in comic plays. The pretty, saucy, maidservant was a staple figure in plays and operettas, including Shakespeare and bawdy Restoration comedies. Lucy, a maidservant in the comic play The Country Wife has "extraordinary" agency: "she is indispensable to the love story, saves her mistress from a disastrous marriage... and acts as the deus ex machina that resolves all the problems at the end of the play."*

Lucy the maidservant scolds her mistress Alithea in The Country Wife Indeed, the more we look at the minor role of servants Austen's novels, the more "problematic" (to use the current parlance) is the contention that Austen was secretly in favour of social reform. Because she could have written novels that featured servants, as her predecessors and contemporaries did. But she didn't.

Lucy the maidservant scolds her mistress Alithea in The Country Wife Indeed, the more we look at the minor role of servants Austen's novels, the more "problematic" (to use the current parlance) is the contention that Austen was secretly in favour of social reform. Because she could have written novels that featured servants, as her predecessors and contemporaries did. But she didn't. In Austen, servants serve the mechanics of the plot just as their real-life counterparts served their masters and mistresses. For example, Austen breaks off a serious talk between Edmund and Fanny with “the appearance of a housemaid [who] prevented any farther conversation."

Mrs. Dashwood's manservant Thomas brings the unhappy (and happily false) news that Edward Ferrars has married Lucy Steele. But we don't learn anything about Thomas. He is not a character we can analyze in terms of his wishes, wants, and traits. "Mrs. Dashwood could think of no other question, and Thomas and the tablecloth, now alike needless, were soon afterwards dismissed."

Emma, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion all contain more details about servants than can be found in the earlier novels, but if you look closely, these glimpses are used as a device for revealing something about the main characters.

"I suppose you know, ma'am, that Mr. Ferrars is married." Mrs. Musgrove and her daughter-in-law criticize each other behind their backs and the way they manage their servants is just one of their many grievances: "I make a rule of never interfering in any of my daughter-in-law's concerns, for I know it would not do;" says Mrs. Musgrove, "but I shall tell you, Miss Anne... that I have no very good opinion of Mrs. Charles's nursery-maid... she is always upon the gad; and... she is such a fine-dressing lady, that she is enough to ruin any servants she comes near. " Mr. Woodhouse's character is revealed as he proses away about the daughter of his coachman going into service: “I would not have had poor James think himself slighted upon any account; and I am sure she will make a very good servant... she always curtseys and... I observe she always turns the lock of the door the right way and never bangs it.”

"I suppose you know, ma'am, that Mr. Ferrars is married." Mrs. Musgrove and her daughter-in-law criticize each other behind their backs and the way they manage their servants is just one of their many grievances: "I make a rule of never interfering in any of my daughter-in-law's concerns, for I know it would not do;" says Mrs. Musgrove, "but I shall tell you, Miss Anne... that I have no very good opinion of Mrs. Charles's nursery-maid... she is always upon the gad; and... she is such a fine-dressing lady, that she is enough to ruin any servants she comes near. " Mr. Woodhouse's character is revealed as he proses away about the daughter of his coachman going into service: “I would not have had poor James think himself slighted upon any account; and I am sure she will make a very good servant... she always curtseys and... I observe she always turns the lock of the door the right way and never bangs it.” Fanny Price is "greatly surprised" when, after a long delay, a servant brings in the tea things at her parents house. She had assumed the "trollopy-looking maidservant" who answered the door must surely be the subordinate servant in this two-servant household, but the girl with the tea-tray looks even worse than the first one. Austen illustrates the poverty and mismanagement in the Price household and Fanny's sinking feelings upon realizing it.

Note that Austen's narrative voice does not extend any sympathy to these two servants, apart from mentioning that their mistress does not know how to manage them properly. Mrs Price is "dissatisfied with her servants, without skill to make them better, and whether helping, or reprimanding, or indulging them, without any power of engaging their respect."

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris in the 1983 Mansfield Park Who shows the most interest in the servants and comments on them the most? Apart from Mrs. Price, it's her sister Mrs. Norris, Austen's most odious villain. But it's all of a piece with her desire to micromanage everything and everybody in her sister's household, “Come, Fanny, Fanny, what are you about? We are going. Do not you see your aunt is going? Quick, quick! I cannot bear to keep good old Wilcox waiting. You should always remember the coachman and horses."

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris in the 1983 Mansfield Park Who shows the most interest in the servants and comments on them the most? Apart from Mrs. Price, it's her sister Mrs. Norris, Austen's most odious villain. But it's all of a piece with her desire to micromanage everything and everybody in her sister's household, “Come, Fanny, Fanny, what are you about? We are going. Do not you see your aunt is going? Quick, quick! I cannot bear to keep good old Wilcox waiting. You should always remember the coachman and horses."She boasts of her "triumph" over the carpenter's ten-year-old son when she suspects him of trying to get a free meal in the servant's hall. Mrs. Norris's hypocrisy -- for she takes everything she can from the Bertrams -- is on full display here. The fact is though, that she knows the name of the carpenter's son, and his age, and undoubtedly Lady Bertram doesn't have the slightest idea who Dick Jackson is.

In Austen's world, people who talk a lot about servants or with servants are petty-minded and vulgar. Compare Mrs. Norris to Sir Thomas. He is extremely displeased by the fact that his son Tom has ordered the estate carpenter to build a stage in the billiard-room in his absence, but none of his ire falls on the servant: "It appears a neat job, however, as far as I could judge by candlelight, and does my friend Christopher Jackson credit.”

Charlotte Palmer and her mother Mrs. Jennings show off the new baby to the housekeeper Mrs. Elton doesn't even know the name of one her own servants, but she gossips about Mr. Knightley's. "[T]he Donwell servants... are all, I have often observed, extremely awkward and remiss.—I am sure I would not have such a creature as his Harry stand at our sideboard for any consideration." Mr. Knightley puts her down pretty bluntly when she tries to interfere in his household: “I will answer for it, that [Mrs. Hodges] thinks herself full as clever, and would spurn any body's assistance.”

Charlotte Palmer and her mother Mrs. Jennings show off the new baby to the housekeeper Mrs. Elton doesn't even know the name of one her own servants, but she gossips about Mr. Knightley's. "[T]he Donwell servants... are all, I have often observed, extremely awkward and remiss.—I am sure I would not have such a creature as his Harry stand at our sideboard for any consideration." Mr. Knightley puts her down pretty bluntly when she tries to interfere in his household: “I will answer for it, that [Mrs. Hodges] thinks herself full as clever, and would spurn any body's assistance.” Mistreatment of servants is one of the way Austen illustrates bad character. The worst employer in Austen is General Tilney, who berates a servant for not announcing Catherine Morland before she enters the room. Catherine assures him that it was all her fault --she rushed in without waiting to be announced,

"[a]nd if Catherine had not most warmly asserted his innocence, it seemed likely that William would lose the favour of his master forever, if not his place, by her rapidity."

The way characters talk about and interact with servants reveal their good and bad qualities, but these vignettes are not an obvious commentary on the unfairness of the social order. The gardener who gives Mrs. Norris a lovely specimen of heath -- we don't know if he really agreed with her diagnosis of his grandson's illness. We don't know if the grandson got better. The story moves on. It wasn't about the gardener, it was about Mrs. Norris. In one rare instance, we learn what a servant is thinking; when Sir Thomas Bertram summons Fanny to have a private conference with her suitor, Henry Crawford:

"Austen’s monsters are invariably attentive to the lower orders, for thus they exercise their self-importance." -- John Mullan, What Matters in Jane Austen"[Baddeley the butler] said, “Sir Thomas wishes to speak with you, ma'am, in his own room.” Then it occurred to [Fanny] what might be going on; a suspicion rushed over her mind which drove the colour from her cheeks; but instantly rising, she was preparing to obey, when Mrs. Norris called out, “Stay, stay, Fanny! what are you about? where are you going? don't be in such a hurry. Depend upon it, it is not you who are wanted; depend upon it, it is me” (looking at the butler); “but you are so very eager to put yourself forward. What should Sir Thomas want you for? It is me, Baddeley, you mean; I am coming this moment. You mean me, Baddeley, I am sure; Sir Thomas wants me, not Miss Price.”

But Baddeley was stout. “No, ma'am, it is Miss Price; I am certain of its being Miss Price.” And there was a half-smile with the words, which meant, “I do not think you would answer the purpose at all.”

Mrs. Norris, much discontented, was obliged to compose herself to work again..." Baddeley’s half-smile also betrays the fact that, however much the masters and mistresses want to hide their private affairs from their servants, concealment is impossible. Next post: Not in front of the servants In A Contrary Wind, the first book in my Mansfield Trilogy, we learn what Christopher Jackson, the carpenter, thinks about the time Mrs. Norris accused his son of trying to cadge a meal in the servant's quarters, and how the servants felt when she finally went away. Click here for more about my novels.

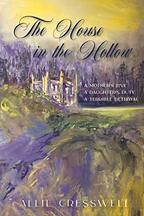

For a beautifully-written, well-researched novel that portrays upstairs/downstairs life in the Regency, I highly recommend Allie Cresswell's novel, The House in the Hollow. The lives and fates of the young heroine and her servants are intertwined. The details of servant's life are integral to the plot and not gratuitous. Annie, a foundling taken in from the poor house, starts at the bottom as a scullery maid. When her young mistress is kind and encouraging, she wins Annie's undying loyalty. The reader can identify with the upstairs heroine and the downstairs heroine in this absorbing story.

For a beautifully-written, well-researched novel that portrays upstairs/downstairs life in the Regency, I highly recommend Allie Cresswell's novel, The House in the Hollow. The lives and fates of the young heroine and her servants are intertwined. The details of servant's life are integral to the plot and not gratuitous. Annie, a foundling taken in from the poor house, starts at the bottom as a scullery maid. When her young mistress is kind and encouraging, she wins Annie's undying loyalty. The reader can identify with the upstairs heroine and the downstairs heroine in this absorbing story.* Godsave, Patricia A., "The Roles of Servant Characters in Restoration Comedy, 1660 - 1685." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018.

Published on December 06, 2020 00:00

December 3, 2020

CMP#16 Civil and Civilization

Explicit Values in Austen: Civility Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Click here for an outline of the series. “And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance.” -- Darcy to Elizabeth

Explicit Values in Austen: Civility Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Click here for an outline of the series. “And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance.” -- Darcy to ElizabethIn my previous post I looked at how important civility was to Jane Austen. Civility -- treating others with consideration, patience, kindness -- was a moral duty and the mark of a civilized person.

The Rambling is an online periodical dedicated to scholarship about the long 18th century. A 2019 article in the The Rambling discusses a "problem" with civility, a problem that is based in its origin.

Professor Urvashi Chakravarty asserts that criticizing people for uncivil behaviour (for example, a waitress refusing to serve a member of the Trump administration) is a form of racialized oppression. And she implies that oppression is the origin of civility, the very purpose of civility.

In “The Problem of Civility: a Genealogy,” Chakravaty engages in some word play around 'civil' to build her case. The word 'civil’ is based on the Latin civilis, meaning “relating to the citizens.” Civilis gives us civility and civilization. Civis gives us citizen and civic. And English has evolved to give us two different meanings for ‘civil:’ (1) an adjective meaning politeness and (2) an adjective referring to civic (government) matters, as in "civil rights."

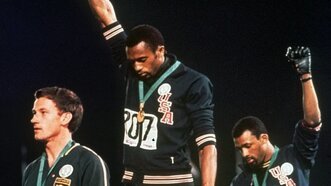

These Olympic athletes suffered socially and professionally for protesting during the medal ceremony Civility is upheld through social sanctions, starting with the mother who squeezes our shoulder firmly and says, "And what do we say to Aunt Phyllis for knitting you such a lovely sweater?" On the other hand, the rights and duties of the citizen are enumerated by codes of law. Citizenship is a type of membership.

These Olympic athletes suffered socially and professionally for protesting during the medal ceremony Civility is upheld through social sanctions, starting with the mother who squeezes our shoulder firmly and says, "And what do we say to Aunt Phyllis for knitting you such a lovely sweater?" On the other hand, the rights and duties of the citizen are enumerated by codes of law. Citizenship is a type of membership.This is interesting for those of us who like to know about the etymology of words, but is there anything illuminating or profound about mixing up (or “conflating” as Chakravarty puts it) the two different definitions? Sure, I could say there is nothing civil about smashing store windows so why do we call it civil disobedience. But I haven’t proved anything. I haven’t made an argument. I’ve merely displayed my ignorance of the two different meanings of ‘civil.’ Or my fondness for really lame puns. It’s as irrelevant as pointing out that “Mrs.” is short for "Mistress." A man’s wife is not his mistress, despite the word origin.

But Professor Chakravaty does conflate the two definitions in her article. She implies that civility is deliberately used by the civil powers to marginalize and oppress. In a minute I’ll discuss the history of civility, but first, I note that Chakravaty goes beyond conflating the two different meanings of 'civil' -– she brings in 'servility' as well. “’Civil’ and ‘servile,’” she writes, “the terms slip from one to the other.”

Anne Elliot, Captain Wentworth and the Musgroves visited Lyme in Persuasion Well, except that civilis pertains to citizens and servile comes from servilis which means, ‘pertaining to slaves.’ So apart from the fact that civility and servility come from two different Latin root words with diametrically opposed meanings, and apart from the fact that “servile” means something different from either of the two meanings of 'civil,' yes, you can “slip” from being civil to being servile.

Anne Elliot, Captain Wentworth and the Musgroves visited Lyme in Persuasion Well, except that civilis pertains to citizens and servile comes from servilis which means, ‘pertaining to slaves.’ So apart from the fact that civility and servility come from two different Latin root words with diametrically opposed meanings, and apart from the fact that “servile” means something different from either of the two meanings of 'civil,' yes, you can “slip” from being civil to being servile. You could be the proprietor of the inn at Lyme, bowing and smiling, as he welcomes the visitors from Uppercross, apologizing because its "so entirely out of season," and his street is "no thoroughfare of Lyme," and there is "no expectation of company.” The inn-keeper takes his civility too far, into the realm of servility. Yes, people sometimes do this. But servility is not the same thing as civility, not in Latin, not in English and not in reality, however much slipping you do.

Professor Chakravarty also says -- as though it were somehow significant -- “the assonance between [‘civil’ and ‘servile’] is immediately heard, noted, ratified.” Yes, ‘civil’ sounds a little like ‘servile.’ And ‘assonance’ sounds like ‘asinine.’ So what? This might do for analyzing a poem, but this is not an indictment of anything.

According to Chakravarty, upholding norms of civility is really -- and quite deliberately -- about repression. Civility “works in service of regimes of privilege, power, and whiteness, mobilizing an insidious strategy to thwart change by silencing the voices of dissidence and difference.”

According to Chakravarty, upholding norms of civility is really -- and quite deliberately -- about repression. Civility “works in service of regimes of privilege, power, and whiteness, mobilizing an insidious strategy to thwart change by silencing the voices of dissidence and difference.”Civility is also used to divide one class from another. “To invoke the “civil” has always been [emphasis added] to demarcate the boundaries of those who do not and cannot belong: the slave, the stranger, the outcast. To rely on civility is to enact and re-enact the forms of psychic, social, and legal violence that have always separated the ‘civil’ body from the uncivil one.” (There’s that ‘conflation’ of the two meanings of ‘civil’ again).

If civility isn’t oppressing you by forcing you to behave, it’s excluding you when you don't behave the right way. Civility gets you coming and going. If there is an actual benefit, a good faith reason, for people to treat each other with politeness and consideration, Chakravarty does not mention it.

Nobody would dispute that civility can be used as a weapon. Anne Elliot thought Captain Wentworth’s “cold politeness” and “ceremonious grace” was “worse than anything.”

Nobody would dispute that civility can be used as a weapon. Anne Elliot thought Captain Wentworth’s “cold politeness” and “ceremonious grace” was “worse than anything.”But was civility developed for the purposes of exclusion and oppression, of “civic erasure”? This would come as a surprise to William Wilberforce. “God Almighty has set before me two great objects,” he wrote in 1787, “the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.” He also formed a Society for the Suppression of Vice and we can see him lampooned in this cartoon.

By “manners,” Wilberforce meant a great deal more than keeping your elbows off the table. "Manners" is more akin to codes of conduct, which includes how we treat one another, which brings in civility.

I think we can agree that Wilberforce did not believe civility was useful for oppressing slaves. Hannah More, his ally in the abolition movement, wrote several conduct books which linked civility with morality and virtue, not servility. Wilberforce and his allies had a profound impact on British society. The Enlightenment also played a role. And so did coffee.

Further, the rise of politeness led to more social levelling, not more social exclusion. Prior to the mid-17th century, courtliness was for the courtier, for people at the top of the aristocratic tree. But the writings of Lord Shaftesbury, who I mentioned in my previous post and the philosopher John Locke brought about a revolution in manners based on the idea that human beings can be empathetic and good to one another. Shaftesbury wrote “All politeness is owing to Liberty." His view of civility is the polar opposite of the view that civility is a tool of oppression.

Further, the rise of politeness led to more social levelling, not more social exclusion. Prior to the mid-17th century, courtliness was for the courtier, for people at the top of the aristocratic tree. But the writings of Lord Shaftesbury, who I mentioned in my previous post and the philosopher John Locke brought about a revolution in manners based on the idea that human beings can be empathetic and good to one another. Shaftesbury wrote “All politeness is owing to Liberty." His view of civility is the polar opposite of the view that civility is a tool of oppression.According to scholars who have studied the rise of politeness in England (and yes, this is actually a field of study and debate), “politeness was associated with improvement in the sense not just of refinements of style but of moral and other reform.”

In “Politeness and the Interpretation of the British Eighteenth Century,” [The Historical Journal: Cambridge, 2002] Lawrence Klein writes that “the social and intellectual elite of Edinburgh famously adapted the pleasures of polite conversation for the pursuit of public improvement. In Scottish thinking, in particular, politeness was grafted on to schemes of human economic and political development to convey the cultural modernity of commercial polities.”

Thanks to the popularity of coffee-houses, people from different social levels began to meet and mingle, to read and discuss the news and ideas of the day, while drinking a stimulating beverage which, unlike alcohol, did not lead to public brawls. According to Professor John Mullan, in a BBC discussion of the rise of politeness, these new public spaces meant that people could "meet on equal terms” despite differences in status. And because there was a new merchant class moving up in the world, there was an interest in acquiring “polish” and good manners.

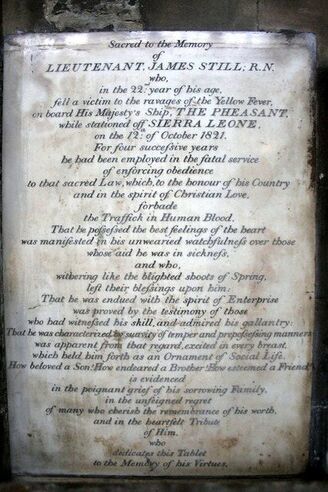

18th century tone policing: Jane Austen's father on the benefits of being polite. When Francis Austen, (Jane Austen’s brother), joined the Navy in 1788, his father sent him a “memorandum” filled with loving advice. After urging Francis to pray regularly, Rev Austen wrote about the importance and the usefulness of good manners. He reminded his son to show respect to his superiors and “every appearance of unselfishness” to his messmates. “With your inferiors,” he goes on, “perhaps you will have but little intercourse, but when it does occur there is a sort of kindness they have a claim on you for, and which, you may believe me, will not be thrown away on them.”

18th century tone policing: Jane Austen's father on the benefits of being polite. When Francis Austen, (Jane Austen’s brother), joined the Navy in 1788, his father sent him a “memorandum” filled with loving advice. After urging Francis to pray regularly, Rev Austen wrote about the importance and the usefulness of good manners. He reminded his son to show respect to his superiors and “every appearance of unselfishness” to his messmates. “With your inferiors,” he goes on, “perhaps you will have but little intercourse, but when it does occur there is a sort of kindness they have a claim on you for, and which, you may believe me, will not be thrown away on them.”Far from regarding civility as something to be used as a weapon against the lower ranks, Reverend Austen preached that the lowly sailors “have a claim” to kindly treatment.

Politeness was therefore both a cause and a symptom in a society that was slowly—very slowly—becoming more egalitarian. Obviously, the urbane and civilized conversation in the coffee houses excluded the people back in Jamaica who were growing the coffee. But as we have seen, the people who were reforming manners in Austen's time were the same people who were urging that slavery was a moral abomination which should be outlawed.

Miss Grey sneering at the rustic Dashwood girls for not having pronouns in their bios. Not all uncivil behaviour is a form of protest by a member of a marginalized group, is it? More often it's just someone being rude and selfish, like a loutish youth not giving the pregnant lady a seat on the bus. What then? Am I "erasing" the loutish teenager when I expect him to give up his seat? Am I enacting social violence on him? Am I first supposed to enquire into his antecedents and calibrate the degree of his marginalization with my own?

Miss Grey sneering at the rustic Dashwood girls for not having pronouns in their bios. Not all uncivil behaviour is a form of protest by a member of a marginalized group, is it? More often it's just someone being rude and selfish, like a loutish youth not giving the pregnant lady a seat on the bus. What then? Am I "erasing" the loutish teenager when I expect him to give up his seat? Am I enacting social violence on him? Am I first supposed to enquire into his antecedents and calibrate the degree of his marginalization with my own? I don't dispute that there are social penalties in our culture for uncivil behaviour, and there are also consequences for civil disobedience. But don’t all cultures have conceptions of good or bad or appropriate manners? How could a society hold itself together without norms of civil behavior? It seems very short-sighted, ahistorical and insular to conflate ‘civility’ with ‘whiteness.' To argue that civility itself is problematic is to ignore many countervailing examples from history. Next post: Service and Servility -- first of a series on servants in Austen (how assonant!) In my novel, A Different Kind of Woman, the Bristol Chapter of the Society for the Suppression of Vice steps in to stop French prisoners of war from selling obscene carvings and drawings. Click here for more about my novels. Full Disclosure: The Rambling has nice and friendly proprietors, a charming snail logo, and they published my "literary novel book review" generator in their first issue, which is very funny -- check it out.

For a deeper dive on the importance of civility and the history of politeness (Lord Shaftesbury), try this article by Alexander Zubatov.

Published on December 03, 2020 00:00

November 30, 2020

CMP#15 Civility and Civilization

Explicit Values in Austen: Civility and Civilization

Explicit Values in Austen: Civility and Civilization

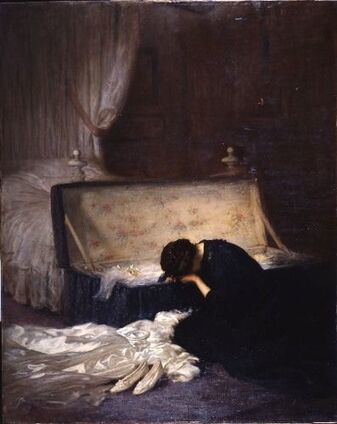

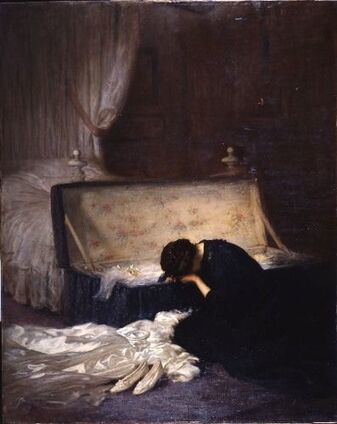

Marianne heartbroken over Willoughby It’s clear that good manners are very important to Jane Austen. She makes this explicit in Sense & Sensibility through the contrasting behaviour of the Dashwood sisters. Marianne's romantic notions about authenticity lead to careless, even rude, behavior. A modern novel might feature a heroine who "finds" herself. Marianne is a heroine who must learn to find happiness through thinking of others besides herself.

Marianne heartbroken over Willoughby It’s clear that good manners are very important to Jane Austen. She makes this explicit in Sense & Sensibility through the contrasting behaviour of the Dashwood sisters. Marianne's romantic notions about authenticity lead to careless, even rude, behavior. A modern novel might feature a heroine who "finds" herself. Marianne is a heroine who must learn to find happiness through thinking of others besides herself.Big sister Elinor wants Marianne “to treat our acquaintance in general with greater attention.” Evidently she’s brought this failing up often enough so that Edward Ferrars is aware of it, after having lived with the family a few weeks. During his later visit to Barton Cottage, he teases, "'You have not been able to bring your sister over to your plan of general civility. Do you gain no ground?'

'Quite the contrary,' replied Elinor, looking expressively at Marianne."

Marianne falls in love with the dashing Willoughby and is heartbroken when he leaves. She has no patience for company, and gives offense by turning down Lady Middleton’s offer of a card game: “Marianne... with her usual inattention to the forms of general civility, exclaimed, 'Your Ladyship will have the goodness to excuse ME—you know I detest cards. I shall go to the piano-forte..."

Elinor catches Lady Middleton’s reaction, and tries to smooth things over with a compliment:

"'Marianne can never keep long from that instrument you know, ma'am, and I do not much wonder at it; for it is the very best toned piano-forte I ever heard.'"

Marianne avoids company, especially Colonel Brandon Hoping to be re-united with Willoughby, Marianne eagerly accepts an invitation from the kindly but vulgar Mrs. Jennings to go to London. Her behaviour en route gives Elinor a clear preview of the type of house guest her sister will be. “She sat in silence almost all the way, wrapt in her own meditations, and scarcely ever voluntarily speaking, except when any object of picturesque beauty within their view drew from her an exclamation of delight exclusively addressed to her sister. To atone for this conduct therefore, Elinor took immediate possession of the post of civility which she had assigned herself, behaved with the greatest attention to Mrs. Jennings, talked with her, laughed with her, and listened to her whenever she could…”

Marianne avoids company, especially Colonel Brandon Hoping to be re-united with Willoughby, Marianne eagerly accepts an invitation from the kindly but vulgar Mrs. Jennings to go to London. Her behaviour en route gives Elinor a clear preview of the type of house guest her sister will be. “She sat in silence almost all the way, wrapt in her own meditations, and scarcely ever voluntarily speaking, except when any object of picturesque beauty within their view drew from her an exclamation of delight exclusively addressed to her sister. To atone for this conduct therefore, Elinor took immediate possession of the post of civility which she had assigned herself, behaved with the greatest attention to Mrs. Jennings, talked with her, laughed with her, and listened to her whenever she could…”When the faithless Willoughby breaks Marianne’s heart. She wants to go home instantly – “tomorrow.”

"To-morrow, Marianne!" [Elinor exclaims] "It would be impossible to go to-morrow. We owe Mrs. Jennings much more than civility; and civility of the commonest kind must prevent such a hasty removal as that."

Marianne even accuses others of incivility. She complains of Mrs. Jennings: "Her kindness is not sympathy… All that she wants is gossip, and she only likes me now because I supply it.” And when Colonel Brandon visits, she snaps, “A man who has nothing to do with his own time has no conscience in his intrusion on that of others." Marianne’s indulgence in her emotions nearly leads to her death. After her recovery, she apologizes to Elinor, and one of the offenses she charges herself with is leaving Elinor to do all the heavy lifting in their social interactions: “Whenever I looked towards the past, I saw some duty neglected… Your example was before me; but to what avail?... Did I imitate your forbearance, or lessen your restraints, by taking any part in those offices of general complaisance or particular gratitude which you had hitherto been left to discharge alone?—No;—not less when I knew you to be unhappy, than when I had believed you at ease, did I turn away from every exertion of duty or friendship...”

Sometimes the ”post of civility” is an exertion, and Austen doesn’t pretend otherwise. Austen herself, from what we can gather, devoted many a tedious hour to chatting with people, especially during her residence in Bath, when she would have preferred to be doing almost anything else. Her compensation was making catty remarks in her letters to Cassandra: "Wednesday. -- Another stupid party last night; perhaps if larger they might be less intolerable, but here there were only just enough to make one card-table, with six people to look on and talk nonsense to each other."

Austen doesn’t insist upon smiling, gracious behaviour to everyone and in all circumstances. Elinor speaks sternly and bluntly to Willoughby when talking over his treatment of Marianne and Eliza. Sometimes Elinor says nothing, as when Edward's brother Robert did not deserve “the compliment of rational opposition.” And then there is her little dig at Lady Middleton’s children, "I confess that while I am at Barton Park, I never think of tame and quiet children with any abhorrence."

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671 - 1713) As Paula Marantz Cohen points out in a 2019 Wall Street Journal article, other Austen characters -- like Mr. Elton in Emma and Mary Crawford in Mansfield Park -- drop their assumed pose of civility when they are angry and embarrassed. Their true nature is revealed “when their guard is down or when they are no longer invested in getting what they want… In Austen, manners for bad people are only skin deep.”

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671 - 1713) As Paula Marantz Cohen points out in a 2019 Wall Street Journal article, other Austen characters -- like Mr. Elton in Emma and Mary Crawford in Mansfield Park -- drop their assumed pose of civility when they are angry and embarrassed. Their true nature is revealed “when their guard is down or when they are no longer invested in getting what they want… In Austen, manners for bad people are only skin deep.”Professor Cohen sees the questions of civility and good manners in Austen as being more than skin deep, more than superficial. Good manners are a reflection of our inner character. She thinks our own “longing for civility in an age of coarseness and meanness” is “central to [Austen’s] popularity."

Austen's belief in the moral importance of civility probably owes something to Lord Shaftesbury. Austen might never have read Shaftesbury's works, but his ideas were diffused in the culture, just as we know about Darwin’s theory of evolution without actually reading his books. Shaftesbury argued that people did not always act out of self-interest, that we are born with an instinct for benevolence -- doing good for others brings us pleasure. He saw civility as more than a mere gloss on behaviour, though he uses the analogy of a polished stone to describe how civility works to improve human interaction in society:

"We polish one another, and rub off our Corners and rough Sides by a sort of amicable Collision. To restrain this, is inevitably to bring a Rust upon Men’s Understanding. ‘Tis a destroying of Civility, Good Breeding, and even Charity itself…”

Historian Christine Zabel explains: “For Shaftesbury, it is clear, politeness was a concept that went far beyond mere rules of good conversation or behavior… politeness was directly linked to political liberty” and freedom of speech. Civility was a mark of civilized society.

But not all academics today take such a positive view of civility, or its effect in society. Next post: Civil and Servile

In my short story "By A Lady," Elizabeth and Darcy have been happily married for several years. They are invited to Rosings by Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Elizabeth is determined to make amends to Anne de Bourgh, who she feels she slighted in the past. "“My conscience does not reproach me on the score of what I did,” [Elizabeth tells Darcy], “but of what I thought. I was uncharitable. I was unkind... I derived more pleasure from disliking her and building on my prejudice than in trying to draw her out. I could easily have made the attempt. Instead I told myself she was stupid, dull, and haughty.”

In my short story "By A Lady," Elizabeth and Darcy have been happily married for several years. They are invited to Rosings by Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Elizabeth is determined to make amends to Anne de Bourgh, who she feels she slighted in the past. "“My conscience does not reproach me on the score of what I did,” [Elizabeth tells Darcy], “but of what I thought. I was uncharitable. I was unkind... I derived more pleasure from disliking her and building on my prejudice than in trying to draw her out. I could easily have made the attempt. Instead I told myself she was stupid, dull, and haughty.” "By A Lady" is part of the Yuletide anthology and makes a great Christmas gift for the Janeite on your list. Proceeds from the e-book and paperback go to Chawton House, the Center for Early Women Writers.

Published on November 30, 2020 00:00

November 26, 2020

"Caught in the act of greatness"

Virginia Wolf famously said of Jane Austen that "of all great writers she is the most difficult to catch in the act of greatness."

Perhaps, but we can certainly catch her in the act of cleverness -- for example, in the way she uses weather to shape events.

"Austen makes her plots turn on the weather," writes John Mullan in his insightful and delightful What Matters in Jane Austen? "Having arranged her characters and defined their situations, having planned her love stories and hatched the misunderstandings that might impede them, she lets the weather shape events. It is her way of admitting chance into her narratives." The weather naturally plays a important part in Regency life and in Austen's novels. In a world where roads were unpaved, and a large portion of the population were farmers, and there was no central heating and double-glazed windows, people were not as isolated from the effects of a rainy day or a hot day as we are today.

The weather naturally plays a important part in Regency life and in Austen's novels. In a world where roads were unpaved, and a large portion of the population were farmers, and there was no central heating and double-glazed windows, people were not as isolated from the effects of a rainy day or a hot day as we are today.

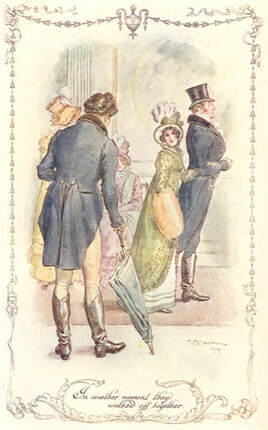

But Jane Austen subtly, cleverly, uses the weather to bring events about. Professor Mullan illustrates this with the example of the rainy day in Bath when Anne Elliot, her sister Elizabeth and the artful widow Mrs. Clay go shopping on Milson Street with Mr. Elliot. It begins to rain and Austen arranges matters so that after some bustle about carriage rides and errands, Anne and Captain Wentworth encounter one another in a shop. He watches as Anne walks off with Mr. Elliot with the "manner of the privileged relation and friend." The captain's walking companions remark on how Mr. Elliot is obviously taken with his cousin Anne.

Another example of using weather to shape events is the light snowfall in Hartfield on the night of the Westons' dinner party which results in Mr. Elton being alone in a carriage with Emma.

A further example, which was so subtle I hadn't noticed it, occurs also in Persuasion. Near the end of the novel, the rain prevents Anne from setting out for the White Hart Inn to meet the Musgroves, where she knows she will also encounter Captain Harville and Captain Wentworth.

Austen uses the rain to "arrange her characters" and bring about the emotional climax of the novel: [Anne] could not keep her appointment punctually, however; the weather was unfavourable, and she had grieved over the rain on her friends' account, and felt it very much on her own, before she was able to attempt the walk. When she reached the White Hart, and made her way to the proper apartment, she found herself neither arriving quite in time, nor the first to arrive. The party before her were, Mrs Musgrove, talking to Mrs Croft, and Captain Harville to Captain Wentworth; and she immediately heard that Mary and Henrietta, too impatient to wait, had gone out the moment it had cleared, but would be back again soon, and that the strictest injunctions had been left with Mrs Musgrove to keep her there till they returned. She had only to submit, sit down, be outwardly composed..." Because Mary and Henrietta had gone out, Anne does not sit and talk with them. The climax of the book can only happen because Anne is free to hear the conversation between Mrs. Croft and Mrs. Musgrove, and is free to talk with Captain Harville by the window, and is overheard by Captain Wentworth. If Henrietta and Mary had been in the room, that wouldn't be possible. Henrietta would be talking about her wedding, Mary would be complaining about something. Both of them would be demanding Anne's attention.

Instead, Anne is free to hear Mrs. Croft decidedly pronounce: "To begin without knowing that at such a time there will be the means of marrying, I hold to be very unsafe and unwise, and what I think all parents should prevent as far as they can." "Anne found an unexpected interest here. She felt its application to herself, felt it in a nervous thrill all over her; and at the same moment that her eyes instinctively glanced towards the distant table, Captain Wentworth's pen ceased to move, his head was raised, pausing, listening, and he turned round the next instant to give a look, one quick, conscious look at her." Then, of course, follows the interesting conversation with Captain Harville, Anne's confession that women love longest, when existence or when hope is gone, followed by what is known in Austenlandia as The Letter.

"Anne found an unexpected interest here. She felt its application to herself, felt it in a nervous thrill all over her; and at the same moment that her eyes instinctively glanced towards the distant table, Captain Wentworth's pen ceased to move, his head was raised, pausing, listening, and he turned round the next instant to give a look, one quick, conscious look at her." Then, of course, follows the interesting conversation with Captain Harville, Anne's confession that women love longest, when existence or when hope is gone, followed by what is known in Austenlandia as The Letter.

But none of that could have happened in that way, without a little rain shower!

The rainy day on Milsom Street also features in my short story about Mrs. Clay in the Rational Creatures anthology, but it is told from Mrs. Clay's point of view. Click here to see more about Rational Creatures.

Perhaps, but we can certainly catch her in the act of cleverness -- for example, in the way she uses weather to shape events.

"Austen makes her plots turn on the weather," writes John Mullan in his insightful and delightful What Matters in Jane Austen? "Having arranged her characters and defined their situations, having planned her love stories and hatched the misunderstandings that might impede them, she lets the weather shape events. It is her way of admitting chance into her narratives."

The weather naturally plays a important part in Regency life and in Austen's novels. In a world where roads were unpaved, and a large portion of the population were farmers, and there was no central heating and double-glazed windows, people were not as isolated from the effects of a rainy day or a hot day as we are today.

The weather naturally plays a important part in Regency life and in Austen's novels. In a world where roads were unpaved, and a large portion of the population were farmers, and there was no central heating and double-glazed windows, people were not as isolated from the effects of a rainy day or a hot day as we are today.But Jane Austen subtly, cleverly, uses the weather to bring events about. Professor Mullan illustrates this with the example of the rainy day in Bath when Anne Elliot, her sister Elizabeth and the artful widow Mrs. Clay go shopping on Milson Street with Mr. Elliot. It begins to rain and Austen arranges matters so that after some bustle about carriage rides and errands, Anne and Captain Wentworth encounter one another in a shop. He watches as Anne walks off with Mr. Elliot with the "manner of the privileged relation and friend." The captain's walking companions remark on how Mr. Elliot is obviously taken with his cousin Anne.

Another example of using weather to shape events is the light snowfall in Hartfield on the night of the Westons' dinner party which results in Mr. Elton being alone in a carriage with Emma.

A further example, which was so subtle I hadn't noticed it, occurs also in Persuasion. Near the end of the novel, the rain prevents Anne from setting out for the White Hart Inn to meet the Musgroves, where she knows she will also encounter Captain Harville and Captain Wentworth.

Austen uses the rain to "arrange her characters" and bring about the emotional climax of the novel: [Anne] could not keep her appointment punctually, however; the weather was unfavourable, and she had grieved over the rain on her friends' account, and felt it very much on her own, before she was able to attempt the walk. When she reached the White Hart, and made her way to the proper apartment, she found herself neither arriving quite in time, nor the first to arrive. The party before her were, Mrs Musgrove, talking to Mrs Croft, and Captain Harville to Captain Wentworth; and she immediately heard that Mary and Henrietta, too impatient to wait, had gone out the moment it had cleared, but would be back again soon, and that the strictest injunctions had been left with Mrs Musgrove to keep her there till they returned. She had only to submit, sit down, be outwardly composed..." Because Mary and Henrietta had gone out, Anne does not sit and talk with them. The climax of the book can only happen because Anne is free to hear the conversation between Mrs. Croft and Mrs. Musgrove, and is free to talk with Captain Harville by the window, and is overheard by Captain Wentworth. If Henrietta and Mary had been in the room, that wouldn't be possible. Henrietta would be talking about her wedding, Mary would be complaining about something. Both of them would be demanding Anne's attention.

Instead, Anne is free to hear Mrs. Croft decidedly pronounce: "To begin without knowing that at such a time there will be the means of marrying, I hold to be very unsafe and unwise, and what I think all parents should prevent as far as they can."

"Anne found an unexpected interest here. She felt its application to herself, felt it in a nervous thrill all over her; and at the same moment that her eyes instinctively glanced towards the distant table, Captain Wentworth's pen ceased to move, his head was raised, pausing, listening, and he turned round the next instant to give a look, one quick, conscious look at her." Then, of course, follows the interesting conversation with Captain Harville, Anne's confession that women love longest, when existence or when hope is gone, followed by what is known in Austenlandia as The Letter.

"Anne found an unexpected interest here. She felt its application to herself, felt it in a nervous thrill all over her; and at the same moment that her eyes instinctively glanced towards the distant table, Captain Wentworth's pen ceased to move, his head was raised, pausing, listening, and he turned round the next instant to give a look, one quick, conscious look at her." Then, of course, follows the interesting conversation with Captain Harville, Anne's confession that women love longest, when existence or when hope is gone, followed by what is known in Austenlandia as The Letter.But none of that could have happened in that way, without a little rain shower!

The rainy day on Milsom Street also features in my short story about Mrs. Clay in the Rational Creatures anthology, but it is told from Mrs. Clay's point of view. Click here to see more about Rational Creatures.

Published on November 26, 2020 00:00

November 23, 2020

An interesting find in Naples

I'm interrupting my "Clutching My Pearls" series for some exciting Shelley news!

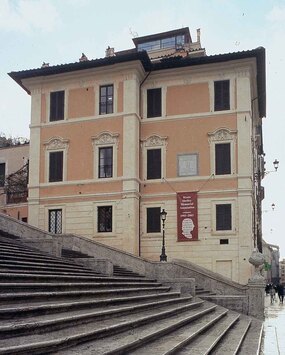

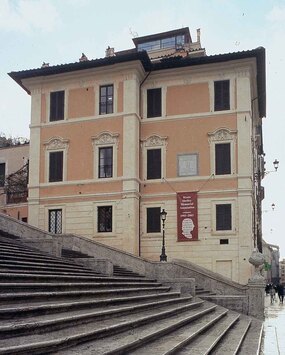

The Journal of the Keats-Shelley Association for 2019, which came out this month, features an article by Donatella Sisti, which tells of her interesting discovery relating to the "Neapolitan Mystery." I used this mysterious episode in the life of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in my novella and in my Mansfield Trilogy, so I was very excited to hear this article and couldn't wait to read it! I assume that the full article is available only to subscribers to the Keats-Shelley journal, or to people with library access, but there is a link here.  The Keats-Shelley Memorial Association maintains the house in which the poet John Keats died in Rome So Percy Bysshe Shelley either fathered or adopted a little girl in Naples in the winter of 1818/1819. We don't know if his wife Mary Shelley knew about this child, or how much she knew, but historians agree she could not have been the mother of the baby. My earlier posts will give a recap of the questions that linger around this child, who died before her second birthday.

The Keats-Shelley Memorial Association maintains the house in which the poet John Keats died in Rome So Percy Bysshe Shelley either fathered or adopted a little girl in Naples in the winter of 1818/1819. We don't know if his wife Mary Shelley knew about this child, or how much she knew, but historians agree she could not have been the mother of the baby. My earlier posts will give a recap of the questions that linger around this child, who died before her second birthday.

She was christened "Elena Adelaide Shelley" and she was evidently placed with a working-class Neapolitan family. She didn't live with the Shelleys and they were not in Naples when she died.

An enterprising scholar and Shelley enthusiast, Donatella Sisti, searched the national archives of Naples to see if she could find anything that would shed further light on the mystery. She had the name of the midwife from the birth certificate and the names of some working-class Neapolitans who served as witnesses for the death certificate. Sisti searched for these names in the archives, including the police reports, of the time but found nothing.

She then turned to the actual neighbourhood where Elena Adelaide lived. Aware that Naples would have had church parish records in addition to government archives, Sisti located the relevant church archives for the area--and found the burial certificate of Elena Adelaide. Her burial was conducted by the priests of the Church of Santi Francesco e Matteo (St. Francis of Assisi). How exciting to uncover this long-hidden document!

Interior of the Church (Chiesa) dei Santi Francesco e Matteo, Naples, photo Wikicommons Sisti reports that the parish records gives the mother's name as "Maria Getwin," yet another variation on the mother's name, which appears to be an approximation of "Godwin," Mary Shelley's maiden name.

Interior of the Church (Chiesa) dei Santi Francesco e Matteo, Naples, photo Wikicommons Sisti reports that the parish records gives the mother's name as "Maria Getwin," yet another variation on the mother's name, which appears to be an approximation of "Godwin," Mary Shelley's maiden name.

The death certificate gives her age as consistent with the date her birth certificate was applied for, not the date on which she was supposedly born, which was December 27 (the older blog posts discuss this discrepancy).

Another question that intrigues me is, if the little girl died on June 10th, which seems incontrovertible, why did Shelley, who lived to the north of Naples at that time, still think she was merely ill in July? How long did it take for the bad news to reach him?

And was it a mere coincidence, that the "superlative rascal," Paolo Foggi, was ramping up his blackmail efforts at the exact same time? Did Foggi learn of Elena Adelaide's death before Shelley?

There is, as Sisti notes, no grave, no plaque, no place for people to leave a flower in Elena Adelaide's memory. Her bones are collected together with the bones of other children in a common ossuary.

I think that Sisti's discovery helps to settle the controversy of the mother's name in the birth, baptismal and death certificate. It is spelled differently in every instance, for example as "Padurin" and "Gebuin." Some, including me, have surmised that the mother's name was not given as "Godwin," others have argued that the variations are erroneous transcribings of "Godwin." I think this burial certificate naming the mother as "Maria Getwin" tilts the argument toward "Godwin."

It would be useful to know if listing the mother's maiden name, even if she was married, was routine in documents of this kind.

Shelley, his wife Mary, her sister Claire and their servants were all travelling around Italy, to Milan, Pisa, and Livorno, in the spring of 1818. They spent the summer at Bagni di Lucca, a spa town in Tuscany. If the child was born sometime during the winter of 1818/19, then she was conceived in May or June 1818. If Shelley was the father, as he claimed on the birth certificate, then the mother was also at one of those places before going to Naples.

I tell a fictional version of the Neapolitan mystery in my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady. A briefer version also appears in A Different Kind of Woman, the last novel in my Mansfield Trilogy.

Congratulations to Donatelli Sisti for uncovering this document and adding to Elena Adelaide's story!

I'll go back to clutching my pearls over Jane Austen in my next post.

The Journal of the Keats-Shelley Association for 2019, which came out this month, features an article by Donatella Sisti, which tells of her interesting discovery relating to the "Neapolitan Mystery." I used this mysterious episode in the life of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in my novella and in my Mansfield Trilogy, so I was very excited to hear this article and couldn't wait to read it! I assume that the full article is available only to subscribers to the Keats-Shelley journal, or to people with library access, but there is a link here.

The Keats-Shelley Memorial Association maintains the house in which the poet John Keats died in Rome So Percy Bysshe Shelley either fathered or adopted a little girl in Naples in the winter of 1818/1819. We don't know if his wife Mary Shelley knew about this child, or how much she knew, but historians agree she could not have been the mother of the baby. My earlier posts will give a recap of the questions that linger around this child, who died before her second birthday.

The Keats-Shelley Memorial Association maintains the house in which the poet John Keats died in Rome So Percy Bysshe Shelley either fathered or adopted a little girl in Naples in the winter of 1818/1819. We don't know if his wife Mary Shelley knew about this child, or how much she knew, but historians agree she could not have been the mother of the baby. My earlier posts will give a recap of the questions that linger around this child, who died before her second birthday.She was christened "Elena Adelaide Shelley" and she was evidently placed with a working-class Neapolitan family. She didn't live with the Shelleys and they were not in Naples when she died.

An enterprising scholar and Shelley enthusiast, Donatella Sisti, searched the national archives of Naples to see if she could find anything that would shed further light on the mystery. She had the name of the midwife from the birth certificate and the names of some working-class Neapolitans who served as witnesses for the death certificate. Sisti searched for these names in the archives, including the police reports, of the time but found nothing.

She then turned to the actual neighbourhood where Elena Adelaide lived. Aware that Naples would have had church parish records in addition to government archives, Sisti located the relevant church archives for the area--and found the burial certificate of Elena Adelaide. Her burial was conducted by the priests of the Church of Santi Francesco e Matteo (St. Francis of Assisi). How exciting to uncover this long-hidden document!

Interior of the Church (Chiesa) dei Santi Francesco e Matteo, Naples, photo Wikicommons Sisti reports that the parish records gives the mother's name as "Maria Getwin," yet another variation on the mother's name, which appears to be an approximation of "Godwin," Mary Shelley's maiden name.

Interior of the Church (Chiesa) dei Santi Francesco e Matteo, Naples, photo Wikicommons Sisti reports that the parish records gives the mother's name as "Maria Getwin," yet another variation on the mother's name, which appears to be an approximation of "Godwin," Mary Shelley's maiden name.The death certificate gives her age as consistent with the date her birth certificate was applied for, not the date on which she was supposedly born, which was December 27 (the older blog posts discuss this discrepancy).

Another question that intrigues me is, if the little girl died on June 10th, which seems incontrovertible, why did Shelley, who lived to the north of Naples at that time, still think she was merely ill in July? How long did it take for the bad news to reach him?

And was it a mere coincidence, that the "superlative rascal," Paolo Foggi, was ramping up his blackmail efforts at the exact same time? Did Foggi learn of Elena Adelaide's death before Shelley?

There is, as Sisti notes, no grave, no plaque, no place for people to leave a flower in Elena Adelaide's memory. Her bones are collected together with the bones of other children in a common ossuary.

I think that Sisti's discovery helps to settle the controversy of the mother's name in the birth, baptismal and death certificate. It is spelled differently in every instance, for example as "Padurin" and "Gebuin." Some, including me, have surmised that the mother's name was not given as "Godwin," others have argued that the variations are erroneous transcribings of "Godwin." I think this burial certificate naming the mother as "Maria Getwin" tilts the argument toward "Godwin."

It would be useful to know if listing the mother's maiden name, even if she was married, was routine in documents of this kind.

Shelley, his wife Mary, her sister Claire and their servants were all travelling around Italy, to Milan, Pisa, and Livorno, in the spring of 1818. They spent the summer at Bagni di Lucca, a spa town in Tuscany. If the child was born sometime during the winter of 1818/19, then she was conceived in May or June 1818. If Shelley was the father, as he claimed on the birth certificate, then the mother was also at one of those places before going to Naples.

I tell a fictional version of the Neapolitan mystery in my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady. A briefer version also appears in A Different Kind of Woman, the last novel in my Mansfield Trilogy.

Congratulations to Donatelli Sisti for uncovering this document and adding to Elena Adelaide's story!

I'll go back to clutching my pearls over Jane Austen in my next post.

Published on November 23, 2020 00:00

November 18, 2020

Some thoughts about the Wollstonecraft statue

I had some thoughts about the new sculpture commemorating Mary Wollstonecraft. It started as Twitter post, then it got too long and I thought, nah, Facebook post, then it got longer and I thought, nah, blog post, and then it got longer and it became a published article! You can read it here:

Published on November 18, 2020 07:54

CMP#14 Enlightening the heathens

Implicit Beliefs in Austen: Enlightenment to the Heathen? Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here for the first in the series.

Implicit Beliefs in Austen: Enlightenment to the Heathen? Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here for the first in the series.

Sylvestra Le Touzel as Fanny Price, 1983 My previous post was a bit of a digression concerning Noble Savages; the idea that aboriginal peoples were innocent and virtuous.

Sylvestra Le Touzel as Fanny Price, 1983 My previous post was a bit of a digression concerning Noble Savages; the idea that aboriginal peoples were innocent and virtuous. In long 18th century prose, however, we more typically find the terms “barbarous” and “savage” used to condemn poor behaviour, and this is how Austen uses these words.

In Sense & Sensibility, Marianne thinks a “barbarous” rival has damaged her reputation with Willoughby. Willoughby’s farewell letter to her was “barbarously insolent.” And when she learns her sister Elinor’s secret, she condemns herself. “How barbarous have I been to you!” The term is used light-heartedly in Pride & Prejudice, when the newly-engaged Bingley spends all his time with Jane Bennet “unless when some barbarous neighbour, who could not be enough detested, had given him an invitation to dinner which he thought himself obliged to accept."

Catherine Morland suspects General Tilney of murdering his wife, a “barbarous proceeding.” Henry Tilney refers specifically to the laws, manners and customs of England to criticize the wildness of her suppositions. “Remember that we are English, that we are Christians.”

The most explicit reference to barbarism occurs in Mansfield Park. When Fanny Price learns that her newly-married cousin Maria has run away with Henry Crawford, she is stupefied. She sees it as “too horrible a confusion of guilt, too gross a complication of evil, for human nature, not in a state of utter barbarism.” [emphasis added]

As mentioned in a

previous post

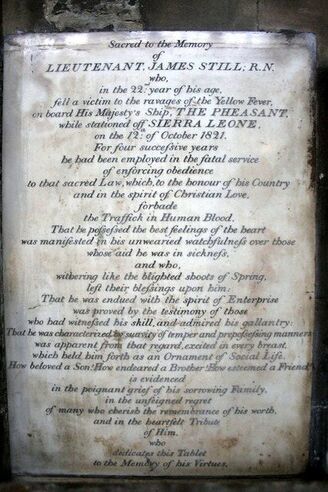

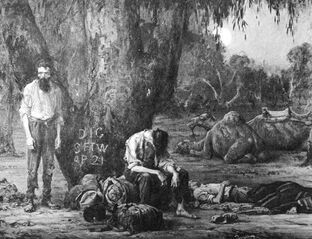

, it was a matter of Church of England doctrine that salvation, that is, eternal life in heaven, was only possible through faith in Jesus Christ. If the heathens and savages didn't hear about the gospel, they had no chance of being saved. That's why the hero in the novel A Middy of the [Anti] Slave Squadron, mentioned in my previous post, prays that God will have mercy on the poor heathen African princess who died for him.

As mentioned in a

previous post

, it was a matter of Church of England doctrine that salvation, that is, eternal life in heaven, was only possible through faith in Jesus Christ. If the heathens and savages didn't hear about the gospel, they had no chance of being saved. That's why the hero in the novel A Middy of the [Anti] Slave Squadron, mentioned in my previous post, prays that God will have mercy on the poor heathen African princess who died for him. Since no-one was proposing that colonists should vacate the premises forthwith and return the conquered territory to the original inhabitants, it began more and more to appear that the best solution for the problem of the conflict between the Old World and the New was to assimilate, civilize and Christianize the aboriginals.

William Wilberforce, the great abolitionist, also supported the cause of spreading the gospel through India and Africa. Not everyone agreed, but it was a widely popular cause and it went hand-in-hand with the abolition movement.

Austen described herself as being "in love" with the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who wrote the History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade. Perhaps she was involved in the domestic campaign against slavery, as many women were -- although in a letter, she exults in the fact that she is going to her rich brother's house where she can enjoy his tea and sugar. (In Austen's day, there was an "Anti-Saccharite" movement which called a boycott of sugar made by slaves.)

The abolition movement in the United Kingdom and later in the United States was driven by dissenting Protestants, such as the Quakers. Supporters of abolition could be found among conventional Anglicans, but it was the Evangelicals who made slavery morally indefensible, shifting public opinion in favour of ending the slave trade.