Lona Manning's Blog, page 21

June 10, 2021

CMP#52 In Defense of Colonel Brandon

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here for the first in the series.

Colonel Brandon: Old-Fashioned Guy or Moral Monster?

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here for the first in the series.

Colonel Brandon: Old-Fashioned Guy or Moral Monster?

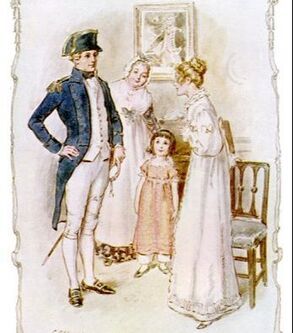

Marianne gets a letter from Willoughby Scholars generally agree that Sense & Sensibility began life as an epistolary novel, a novel in letters. This is a form of novel which was rapidly losing popularity at the time, which may be why Austen re-drafted it as a narrative.

Marianne gets a letter from Willoughby Scholars generally agree that Sense & Sensibility began life as an epistolary novel, a novel in letters. This is a form of novel which was rapidly losing popularity at the time, which may be why Austen re-drafted it as a narrative.It is puzzling to try and backwards-engineer the Sense & Sensbility we have today as an epistolary novel – who is writing letters to whom? The critic Brian Southam surmised that Elinor and Marianne each had a girl friend, a confidante, that they wrote to, which means that in the re-write these best friends were excised. I doubt it; I don't think Austen would eliminate two major characters from a book. I think it's more likely that Marianne and Elinor are separated for most of the time and are writing to each other. Perhaps only Marianne went to London with Mrs. Jennings, in pursuit of Willoughby, and poured out her hopes, her fears, and her final betrayal in letters to Elinor.

With such a version, you wouldn't need Margaret, the third sister, as a character because as I noted in my Mother's Day post , Margaret's only useful function in the novel is to keep her mother company when both of the older girls go to London. So perhaps Austen didn't edit out two female friends, maybe she edited in Margaret.

The novel as we know it is told through Elinor’s consciousness. And since she doesn’t confide in anyone, what would her letters say? “Having a quiet time in Devon, I visited with Lucy Steele, everything's fine, don't worry about me”? I can't explain how Austen would have handled the Edward-Lucy-Elinor plot with letters.

But there are some recognizably 18th century vestiges in the novel. One is the frequency of the Johnsonian cadence .His abilities in every respect improve as much upon acquaintance as his manners and person.In showing kindness to his cousins therefore he had the real satisfaction of a good heart; and in settling a family of females only in his cottage, he had all the satisfaction of a sportsman…My gratitude will be insured immediately by any information tending to that end, and hers must be gained by it in time. We met by appointment, he to defend, I to punish his conduct.Do not, my dearest Elinor, let your kindness defend what I know your judgment must censure. Another 18th century remainder is the “inset narrative.” That’s when one character takes center stage and explains their backstory, as Colonel Brandon does in Sense & Sensibility. The device of the inset narrative would have been a familiar one to Austen's readers; it appears in other 18th century novels. In Jane Austen and the Fiction of Her Time, Mary Waldron gives the examples of the novels of Henry MacKenzie, or Maria Edgeworth's Belinda. Austen breaks up this story-within-a-story with exclamations and reactions from Elinor, and she tells us that Brandon has to interrupt himself to try and regain his composure. In the original version, his tale could have been told in more detail in a series of letters to Elinor, with breaks at the dramatic parts: ("even now the recollection of what I suffered—”)

Marianne has no time for Colonel Brandon In the inset narrative, Colonel Brandon tells Elinor about how his elopement with Eliza, the girl he loved, was thwarted. He left England with a broken heart and went with his regiment to the East Indies. He came back to find Eliza dying, and she entrusted her illegitimate daughter to him. He brought her up, that is, he provided for her in the same way that Harriet Smith was provided for in Emma. Who knows what he planned to do for her when she grew up and got engaged? But instead, Eliza was seduced by Willoughby. “Such,” said Colonel Brandon, after a pause, “has been the unhappy resemblance between the fate of mother and daughter! and so imperfectly have I discharged my trust!”

Marianne has no time for Colonel Brandon In the inset narrative, Colonel Brandon tells Elinor about how his elopement with Eliza, the girl he loved, was thwarted. He left England with a broken heart and went with his regiment to the East Indies. He came back to find Eliza dying, and she entrusted her illegitimate daughter to him. He brought her up, that is, he provided for her in the same way that Harriet Smith was provided for in Emma. Who knows what he planned to do for her when she grew up and got engaged? But instead, Eliza was seduced by Willoughby. “Such,” said Colonel Brandon, after a pause, “has been the unhappy resemblance between the fate of mother and daughter! and so imperfectly have I discharged my trust!” Brandon fought a duel with Willoughby: “we met by appointment, he to defend, I to punish his conduct. We returned unwounded, and the meeting, therefore, never got abroad.” Perhaps Willoughby fired first and missed, and Brandon fired his pistol into the air in a gesture of contempt. And for what it's worth, Brandon has presumably faced danger in battle while Willoughby loafed around in England.

The man that Marianne thinks is her beau ideal turns out to have feet of clay. As Mary Waldron says, Willoughby talks romantically but acts rationally in abandoning Marianne for a wealthy heiress.

Colonel Brandon's story, then, is like the plot of a sentimental and tragic novel. He loved Eliza, and now he loves Marianne, with a chivalric kind of love. He has an elevated, idealistic view of Womankind. He is horrified when he hears of Eliza’s divorce because he knows it means she’s committed adultery. This is enormously painful to him; better that she had died like a sentimental heroine than stooped to this kind of dishonour. On top of that, he gives a valuable living away to Edmund Bertram – a man he barely knows -- in the assumption that he is helping him marry the girl he loves.

Brandon loves Marianne silently and hopelessly. It's so poignant when John Dashwood says to him: “one must allow that there is something very trying to a young woman who has been a beauty in the loss of her personal attractions. You would not think it perhaps, but Marianne was remarkably handsome a few months ago; quite as handsome as Elinor. Now you see it is all gone.” Austen doesn't give us Colonel Brandon's answer. He's just standing there quietly, his heart bleeding for Marianne.

Willoughby never was the romantic hero. Willoughby was an imposter. Colonel Brandon stands revealed as the true romantic hero.

But not according to Helena Kelly, who casts a jaundiced eye on all of Austen's heroes except for Darcy in her book, Jane Austen: the Secret Radical. She suspects Brandon of lying about his relationship with Eliza. She thinks he seduced Eliza and got her pregnant, then scampered off to India when she got married to his brother. When he judges Eliza for slipping from the paths of virtue, he's covering up his own guilt in the matter.

Brandon is already in Kelly’s bad books because of his India connection. Serving with the army or with the East India Company’s army in India means that he’s a colonial exploiter. "Brandon is tainted by association."

Battle of Assaye in India It's true that public opinion about India was mixed in Austen's time and it became a long-standing political issue as well. I could go on a long digression about India and colonialism. But the question is, how did Brandon's colonial connection go down when Austen published the book? The knock

against "nabobs"

-- guys who got rich in India -- is that they were vulgar social climbers. Some people also condemned the exploitation of India. But on the other hand, the East Indies was an outlet and an opportunity for the younger sons of the gentry, and Austen's readers were the gentry.

Battle of Assaye in India It's true that public opinion about India was mixed in Austen's time and it became a long-standing political issue as well. I could go on a long digression about India and colonialism. But the question is, how did Brandon's colonial connection go down when Austen published the book? The knock

against "nabobs"

-- guys who got rich in India -- is that they were vulgar social climbers. Some people also condemned the exploitation of India. But on the other hand, the East Indies was an outlet and an opportunity for the younger sons of the gentry, and Austen's readers were the gentry. I'll refer you again to historian Rory Muir's book, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune: How Younger Sons Made Their Way in Jane Austen's England. Our Colonel Brandon, like all younger sons, had to find a profession, and in those days, his options were severely limited: basically the army, the navy, the church or the law. He was limited by social strictures and, because it was a pre-industrial age, there weren't that many job choices out there. Brandon can't start his own environmental consultancy or IT start-up. So he did what thousands of younger sons did -- he joined the army. Austen's readers would have been thoroughly familiar with this scenario -- it was what many of the young men in their own families had done or would do. It would be a mistake to think that many readers blamed Brandon for going to India, even if British involvement with India was criticized at the time.

Brandon is not a "nabob" -- that is, he didn't go to India to get rich, he went over as an officer in an army. So too did the foremost hero of the age, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington . He was a younger son, too.

Austen sent Brandon abroad for plot purposes, then elevated him from younger son to estate owner by killing off his brother. That's just straightforward plotting stuff. Brandon inherited the estate five years before the commencement of the book, which would have been when his ward Eliza, the daughter of Eliza, was ten years old or so. Dr. Kelly suggests that Eliza Jr. had a moral right to her mother's inheritance, which Brandon's father snagged for the family. We're left to surmise how Eliza Jr. and her daughter live out their lives. Mrs. Jennings thinks Eliza Jr. would have been apprenticed out at small cost -- apprenticed to a milliner, perhaps. I've no doubt Eliza Jr. and her child would be well-supported financially by Brandon, but socially, she's off the board in terms of making a genteel marriage.

Austen sent Brandon abroad for plot purposes, then elevated him from younger son to estate owner by killing off his brother. That's just straightforward plotting stuff. Brandon inherited the estate five years before the commencement of the book, which would have been when his ward Eliza, the daughter of Eliza, was ten years old or so. Dr. Kelly suggests that Eliza Jr. had a moral right to her mother's inheritance, which Brandon's father snagged for the family. We're left to surmise how Eliza Jr. and her daughter live out their lives. Mrs. Jennings thinks Eliza Jr. would have been apprenticed out at small cost -- apprenticed to a milliner, perhaps. I've no doubt Eliza Jr. and her child would be well-supported financially by Brandon, but socially, she's off the board in terms of making a genteel marriage.But the real question is, does Austen portray Colonel Brandon as a secret villain, or does she portray him with sympathy? In both of these things -- his excursion to India and his reaction to Eliza's fall from virtue, Brandon is behaving as a man of his time. So I doubt that Austen's readers would have condemned him for it. In the beginning of this series, I tried to make the case that we may think of ourselves as morally better than 18th century people, but we are certainly much, much, richer . We have birth control and a social safety net and the consequences for someone like Eliza are very different today.

The practical objection to recasting Colonel Brandon as a moral monster is that it makes no sense in terms of the emotional payoff and the narrative structure of Sense & Sensibility. And while Austen does have an ironic tone, you don't write a paragraph like this at the end of your book and intend it ironically:

"Colonel Brandon was now as happy, as all those who best loved him, believed he deserved to be;—in Marianne he was consoled for every past affliction;—her regard and her society restored his mind to animation, and his spirits to cheerfulness; and that Marianne found her own happiness in forming his, was equally the persuasion and delight of each observing friend. Marianne could never love by halves; and her whole heart became, in time, as much devoted to her husband, as it had once been to Willoughby."

My final argument in favour of Colonel Brandon? Two words. Alan Rickman. Ellen and Harriet, the podcasting ladies behind Reading Jane Austen, have a great series on Sense & Sensibility (and they have done Pride & Prejudice too!) Click here for their website. They did a deep dive on the Colonel Brandon/Eliza Williams timeline and you can find it here.

Dame Emma Thompson changed Eliza William's backstory in the 1995 movie. (Here is the scene where Mrs. Jennings tells Elinor about Eliza). She wasn't an heiress, so no-one filched her money. "Eliza was poor," says Mrs. Jennings.

The real-life abolitionist, James Stephen, tells his backstory to Fanny Price in my novel, A Contrary Wind. Stephen was quite the scamp in his youth! Click here for more about my novels.

Published on June 10, 2021 00:00

June 7, 2021

CMP #51 The Vortex of Dissipation!

This is the second in my series about women writers of Austen's time.

This is the second in my series about women writers of Austen's time. Click on the "Authoresses" category on the right for more.

Elizabeth Helme (1753?-1814?) wrote several best-sellers.

This discussion of Helme's novel Modern Times contains spoilers. 18th century Women Writers, Vortex of Dissipation Edition “Devereux Forester’s being ruined by his Vanity is extremely good; but I wish you would not let him plunge into a ‘vortex of Dissipation’. I do not object to the Thing, but I cannot bear the expression;–it is such thorough novel slang–and so old, that I dare say Adam met with it in the first novel he opened."

-- Jane Austen, giving advice to her niece about novel-writing, September 28, 1814 Maybe Jane Austen had Elizabeth Helme’s Modern Times: or, The Age We Live In, in mind when she gave her writing advice to her niece. Modern Times was published in April of 1814 and contained four "vortexes," including two "vortexes of dissipation."

If Austen had read Helme's book, she might have wondered, in her turn, if Helme had read Sense & Sensibility; Modern Times features a family named Willoughby and the main character is a Colonel Brandon type. Sir Charles Neville wasn’t allowed to marry the girl he loved so he joined the army and went abroad for many years. Plus there are two sisters and the older one is virtuous and sensible while the younger one isn't. But otherwise Modern Times, and Helme, are very different from Austen.

Modern Times is dedicated by permission to the Countess Cowper. Emily Lamb, Countess Cowper, was at the very top of the social and political tree, a patron of Almack’s, and later the wife of a prime minister. Her mother was notorious for her many love affairs and Countess Cowper herself had a long-standing relationship with Lord Palmerston, whom she married after Lord Cowper died.

Emily, Countess Cowper

Emily, Countess Cowper (1787–1869) by William Owen I only mention this because Countess Cowper had no objection to giving her blessing to a book which portrayed the nobility as decadent, selfish, immoral, people. The idea that it was daring or revolutionary in Austen’s time to attack the extravagance and corruption of the titled classes is just not accurate. Decrying the excesses of the rich and privileged was an extremely common topic for a novel, almost expected, one might say. Novels were expected to convey a moral lesson and the nobility were an easy target. (For more spendthrift, stupid nobles, check out Maria Edgeworth's Belinda or her Castle Rackrent.) Readers of the day loved to tsk-tsk over the rakish young viscount who loses everything at the gaming table, or Lady So-and-So who bankrupts herself giving lavish entertainments to vie with another society hostess. These characters populate the pages of Modern Times. Helme moralizes over them but she provides the salacious details as well. Apart from Sir Charles, the virtuous people in Modern Times are all from the middling classes. Elizabeth Helme probably never saw a lavish masked ball or a high-class gambling den in her life, but unlike Austen, Helme never drew back from depicting scenes and places where she had never been. A brief flashback segment of the novel is set in the West Indies, where a dissolute, vapid baronet and his selfish, shallow, wife and their spoiled, bratty daughter (check, check and check) live for a few years after they've squandered their inheritance. I think the main reason the author sends them to the West Indies is that in novels, its a place where people got rich quickly. The baronet obligingly gets rich and then dies, so Lady Neville and Fanny go back to England to be reunited with the older daughter Elizabeth. At the same time the widow meets up with her brother-in-law Sir Charles. He is upright and decent, so she dislikes him, but she has to be civil because he controls the family purse-strings.

In the opening scene of the novel, the carriage conveying the widow, her spoilt daughter, and Sir Charles arrives at the old family estate. From the road overlooking the church yard they observe a funeral procession for a servant, with Elizabeth walking behind the coffin. Mom is horrified: “Can a daughter of mine… trudge on foot, like a common pauper, to the funeral of a domestic!”

A Brontë could have made so much of a scene like this – the tolling church bell, the mourners, the beautiful girl walking behind the coffin, the carriage silhouetted against the setting sun. However, Helme is not Brontë. Though Helme was praised for the moral tone of her novels, one of her reviewers said she should not “flatter herself with any expectation of figuring among the foremost of our literary countrywomen."

At any rate, Lady Neville, upon learning that smallpox is raging in the village, quickly turns the carriage around, but Sir Charles jumps out to comfort his niece Elizabeth, and to visit the grave of his long-lost sweetheart. Then we meet the virtuous clergyman Mr. Willoughby and his family, and the virtuous but poor clergyman Mr. Griffiths and his family.

Then, long story short, everybody goes to live in London where some idle cads who have gambled their inheritances away set their sights on the young heiresses Elizabeth and Fanny. Fanny and Elizabeth are kept in the background for long stretches of the novel; as though Helme wasn’t interested in them or didn’t know how to make them interesting. The girls do the usual heroine stuff: they are covered with confusion, they blush, they turn of a deathly pallor and faint dead away when the plot calls for it. Sir Charles helps the virtuous poor: he hires Miss Griffiths as governess for the girls and pays her a handsome wage, he purchases army commissions for Charles Willoughby and Edward Griffiths, the clergymen's sons.

Sir Charles also patiently helps several high-born characters who have messed up their lives. Lady Belvue owes a fortune to various tradesmen and she has lost a fortune at the gaming tables but when bankruptcy and disgrace are staring her in the face, she vows to reform: “Alas! Sir Charles, harpies, vultures, sharpers have been, I shame to say, so long my associates, that all rectitude, all sense of moral and religious obligation has been obliterated and lost in the overwhelming vortex of gaming and dissipation!”

Likewise, the vortex of London is initially alluring for Fanny. Her head is turned by all the attention she gets, but not for long.

Some of the action of Modern Times takes place in Hyde Park where Lady Neville goes in her carriage to see and be seen. Fanny and Elizabeth's careless suitors accidentally cause the carriage horses to bolt. The girls are thrown into the Serpentine but are rescued from drowning by the poor but gallant Charles Willoughby and Edward Griffiths.

Some of the action of Modern Times takes place in Hyde Park where Lady Neville goes in her carriage to see and be seen. Fanny and Elizabeth's careless suitors accidentally cause the carriage horses to bolt. The girls are thrown into the Serpentine but are rescued from drowning by the poor but gallant Charles Willoughby and Edward Griffiths.

“Fanny had been born amidst folly, and nurtured by caprice and extravagance; most fortunately for her, a strong natural sense, though not early cultivated, and some happy concurring circumstances, timely rescued her from impending danger, and was finally conducive to her quitting the paths of error, and becoming a rational being.”

“Fanny had been born amidst folly, and nurtured by caprice and extravagance; most fortunately for her, a strong natural sense, though not early cultivated, and some happy concurring circumstances, timely rescued her from impending danger, and was finally conducive to her quitting the paths of error, and becoming a rational being.” There are three weddings at the end (Miss Griffiths the governess finds love as well), but unlike Colonel Brandon, Sir Charles Neville doesn't remarry and there is no hint of a romance for him. He is too old, perhaps, to ever feel or inspire affection again.

Since Modern Times is a posthumous novel, possibly Elizabeth Helme was dying when she wrote it; the happy wrapping-up at the end is rather abrupt. Out of the blue, a long-lost relative returns from India with a staggering fortune and the virtuous get their reward here on earth. Although Helme is critical of slavery in the West Indian part of the narrative, she still uses the a "golden nabob" as a plot device. As I’ve learned, “Uncle So-and-So died and left you his dubiously-acquired fortune” is an exceedingly common plot device for the era and even Charlotte Brontë wasn't above using it in Jane Eyre. What little we know about Elizabeth Helme makes her a sympathetic character. She was from a lower social class than Austen but she acquired enough education to produce translations of French novels. She and her schoolmaster husband had five children. She was more successful than Austen in her lifetime, but for at least the last ten years of her life, she lived in poverty with a "complicated and hopeless dropsical and liver complaint."

The University of Cambridge Orlando database sums up Helme thusly: “Her novels abound in cliché but deploy their derivative plots, characters, and diction with attractive energy and conviction. She is interested in problems of class, race, and social justice, though given to finding easy fictional solutions for them.”

I was going to write about the ways (in terms of style and theme) that Austen differs from Helme, but I'll save it for another post!

When the news of the victory at Waterloo reached England, many towns held celebratory bonfires to mark the defeat of Napoleon after decades of war. There's one such bonfire in my novel, A Different Kind of Woman, where Mary Crawford has to deal with an unwanted admirer who makes trouble for her. Click here for more about my books. Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen, her values, and the values of the age in which she lived. Click here for the first in the series.

Published on June 07, 2021 00:00

June 1, 2021

CMP#50 Putting Them Out in the World

This blog post features a lesser-known (today that is) author of Austen's time, the prolific Barbara Hofland, who wrote many tales emphasizing Christian morality. “It is amazing,” said [Mrs. Norris], “how much young people cost their friends, what with bringing them up and putting them out in the world! They little think how much it comes to, or what their parents, or their uncles and aunts, pay for them in the course of the year. Now, here are my sister Price's children; take them all together, I dare say nobody would believe what a sum they cost Sir Thomas every year, to say nothing of what I do for them.” -- Mansfield Park Putting Them Out in the World: Choosing a Career for your Children in Regency Times

This blog post features a lesser-known (today that is) author of Austen's time, the prolific Barbara Hofland, who wrote many tales emphasizing Christian morality. “It is amazing,” said [Mrs. Norris], “how much young people cost their friends, what with bringing them up and putting them out in the world! They little think how much it comes to, or what their parents, or their uncles and aunts, pay for them in the course of the year. Now, here are my sister Price's children; take them all together, I dare say nobody would believe what a sum they cost Sir Thomas every year, to say nothing of what I do for them.” -- Mansfield Park Putting Them Out in the World: Choosing a Career for your Children in Regency Times

My article about considerations around the choice of career in Regency times is in the current issue of

Jane Austen’s Regency World

magazine. Because finding the right profession is such a broad topic, I limited the scope of the article to a discussion about Fanny Price’s six brothers, who were started in their professions thanks to the generosity of their uncle Sir Thomas Bertram.

My article about considerations around the choice of career in Regency times is in the current issue of

Jane Austen’s Regency World

magazine. Because finding the right profession is such a broad topic, I limited the scope of the article to a discussion about Fanny Price’s six brothers, who were started in their professions thanks to the generosity of their uncle Sir Thomas Bertram.Helping young people get a start in life was referred to as “putting them out in the world.” Generous patrons would sometimes help promising young people, even if they weren’t related. Darcy’s father is very generous to Mr. Wickham, the son of his steward, though of course Wickham throws it all away. In Coelebs in Search of a Wife, the young hero is impressed and touched when he sees his future bride shows charitable kindness to Dame Alice, an old pensioner in the village. Dame Alice is cared for by a little granddaughter, and the question is, what will become of her after the old woman dies? “I ventured, with as much diffidence as if I had been soliciting a pension for myself, to entreat that I might be permitted to undertake the putting forward Dame Alice's little girl in the world, as soon as she should be released from her attendance on her grandmother.” The hero is offering, in other words, to find employment for her. Probably he will pay for her apprenticeship in some trade. And yes, he's doing it to impress the girl he's courting, but still, it's nice of him to help a little village girl in a world with no public schools and limited resources.

The Merchant's Widow leaves London with her 7 children Historian Rory Muir’s book

Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune

is a valuable reference for understanding how people provided for their children, specifically younger children who, unlike the first-born son, would not inherit an estate. Even after entering certain professions, such as the church, medicine, or the law, there was by no means an assured income, and many young men had to postpone marriage or never marry at all.

The Merchant's Widow leaves London with her 7 children Historian Rory Muir’s book

Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune

is a valuable reference for understanding how people provided for their children, specifically younger children who, unlike the first-born son, would not inherit an estate. Even after entering certain professions, such as the church, medicine, or the law, there was by no means an assured income, and many young men had to postpone marriage or never marry at all. After I wrote my article about the Price brothers, I came across an 1814 book by Barbara Hofland, The Merchant’s Widow, which centers around this problem. The Daventrees are higher up on the social scale and much richer than the Prices. But there's a bank collapse, the merchant dies, and the widow is left with a reduced income and seven children. Mrs. Daventree retires into the country with her children and a few loyal servants. She lives modestly but she is still clinging on to her social class as a gentlewoman.

Her quandary is how to educate Henry, Charles, Sophia, Louisa, Edward, Anne and Eliza and equip them with a profession so they can provide for themselves when they grow up. She can only afford to send one son at a time to boarding school (higher education for boys usually meant going away to school), so Henry goes first. Charles, the second-born son, she sends to the local “grammar school,” since he wants to become a sailor, a profession which “did not call so much for a finished as a rapid education.”

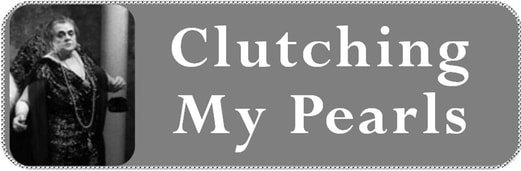

A standard will template from 1810 provides for allowing funds for putting younger sons out in the world. Mrs. Daventree wonders if any of her old city friends could “be of essential advantage to her son.” Having good connections, or “interest,” was of paramount importance, as we know from Mansfield Park. Sir Thomas doesn't have "interest" in the Navy and can't help his nephew William. Luckily, Mrs. Daventree knows a kind and upright Admiral who sponsors Charles for the Navy. But what can be done for her first-born? He wants to become a physician, and although “he could study at Edinburgh for a comparatively small expense... many years must elapse, even after he had attained knowledge, before he can hope for practice." Mrs. Daventree cites "a vulgar proverb:" "a physician seldom gains his bread till he has lost his teeth,” that is, he won't make enough to live on until he is old.

A standard will template from 1810 provides for allowing funds for putting younger sons out in the world. Mrs. Daventree wonders if any of her old city friends could “be of essential advantage to her son.” Having good connections, or “interest,” was of paramount importance, as we know from Mansfield Park. Sir Thomas doesn't have "interest" in the Navy and can't help his nephew William. Luckily, Mrs. Daventree knows a kind and upright Admiral who sponsors Charles for the Navy. But what can be done for her first-born? He wants to become a physician, and although “he could study at Edinburgh for a comparatively small expense... many years must elapse, even after he had attained knowledge, before he can hope for practice." Mrs. Daventree cites "a vulgar proverb:" "a physician seldom gains his bread till he has lost his teeth,” that is, he won't make enough to live on until he is old.Paying for Henry’s schooling also means there is no money left over for Edward, the third son, who wants to become an architect. The widow laments that “[Henry’s] desire of pursuing a learned profession seemed to preclude the younger... since, with the utmost economy, her income would not allow her to support two sons at school at the same time, without condemning herself and daughters to be mere household drudges.” In other words, she would have to dismiss all her servants and keep house herself which indeed was a full time job involving much rough manual labour, unlike today. Mrs. Daventree is not shirking the housework because of genteel fastidiousness: she knows Sophia and Louisa must also have free time to pursue their own educations.

Doomed romance: Jane Austen and Tom LeFroy All of the children are noble-minded and virtuous in the face of their straitened circumstances. The girls plan to become governesses as soon as they are old enough, so they can earn money to support the education of their brothers. Sophia sells her beautiful long hair so Henry can have medical textbooks. Charles rises in the Navy and wins some prize money, which he turns over to his family. Henry, as the first-born son, is entitled to inherit his mother’s “jointure,” that is, all her investment income upon her death. He vows to “disclaim” it by “legal deed, at the close of my minority.” The money shall be distributed equally between the remaining children.

Doomed romance: Jane Austen and Tom LeFroy All of the children are noble-minded and virtuous in the face of their straitened circumstances. The girls plan to become governesses as soon as they are old enough, so they can earn money to support the education of their brothers. Sophia sells her beautiful long hair so Henry can have medical textbooks. Charles rises in the Navy and wins some prize money, which he turns over to his family. Henry, as the first-born son, is entitled to inherit his mother’s “jointure,” that is, all her investment income upon her death. He vows to “disclaim” it by “legal deed, at the close of my minority.” The money shall be distributed equally between the remaining children. Sophia and Louisa are beauties, as well as being virtuous and talented, and Mrs. Daventree is anxious for them: “Though aware that Sophia was worthy the love of any man, yet she knew that portionless, dependent girls are rarely married for love, and even when they are, very seldom enjoy the happiness they may, perhaps, highly merit…”

Louisa is admired by Frederic, the nephew of her employers, and so his aunt and uncle send him back to London to prevent the young people from entering into a hopeless romance (which I've mentioned in a previous post). The uncle tells Mrs. Daventree: “I honour your character, and I like your daughter Louisa very much; but I think it right to tell you, that Frederic Barnet has it not in his power to marry for seven years to come, he being educated for the bar. I therefore warn you against admitting him into your house; at the same time, I beg leave to repeat, that I hereby mean no possible disrespect to you or Louisa, whose conduct under my roof was equally sensible and modest, and whose welfare I consider in this advice.”

We Janeites are of course reminded of the real-life situation of Jane Austen and Tom LeFroy. The circumstances are very similar. The adults intervene and quash a budding romance because there is no money for marriage and it would be folly to let an attachment grow.

Henry, the budding physician, is likewise unable to fall in love. Frederic’s uncle emphasizes the problem: “Young men in professions can’t afford to marry; now there’s your son [Henry] the doctor, as fine a young fellow as the sun shines on, why, he musn’t marry these twenty years."

Sophia, too, is in love and she's suffering, just like Louisa.

Fortunately -- and unlike the doomed romance of Jane Austen and Tom Lefroy -- news arrives that an old uncle has died abroad, leaving Henry a stupendous fortune.* Henry promptly shares it with his mother and siblings and now everyone can marry the person they love.

To paraphrase Mansfield Park, there are not so many childless rich uncles in the world as there are poor young people to deserve them.

Barbara Hofland (1770 - 1844) was a prolific writer of books of all kinds -- books for young people, such as The Merchant's Widow, children's books, and guide books. The Orlando database of women writers states that she was "born into the urban lower middle class, [but] slipped a little further down the status ladder while running her own shop. Later she struggled to remain in the upper middle class, to which both her husbands belonged." She was herself a young widow left with an infant son to provide for. It appears that she worked and wrote all her life until her death. At different times she was a shop-owner. a boarding-school proprietor and a teacher as well as a writer. She wrote over 60 books which were widely translated. *As I've mentioned before, the lucky and unexpected inheritance is an exceedingly

common plot device

in novels of this period, and often there's no reference to the origin of the wealth, ie slavery. However, Mrs. Hofland wrote at least one other novel, The Barbadoes Girl, which is

explicitly anti-slavery.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in.

Barbara Hofland (1770 - 1844) was a prolific writer of books of all kinds -- books for young people, such as The Merchant's Widow, children's books, and guide books. The Orlando database of women writers states that she was "born into the urban lower middle class, [but] slipped a little further down the status ladder while running her own shop. Later she struggled to remain in the upper middle class, to which both her husbands belonged." She was herself a young widow left with an infant son to provide for. It appears that she worked and wrote all her life until her death. At different times she was a shop-owner. a boarding-school proprietor and a teacher as well as a writer. She wrote over 60 books which were widely translated. *As I've mentioned before, the lucky and unexpected inheritance is an exceedingly

common plot device

in novels of this period, and often there's no reference to the origin of the wealth, ie slavery. However, Mrs. Hofland wrote at least one other novel, The Barbadoes Girl, which is

explicitly anti-slavery.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in.Click here for the first in the series.

Published on June 01, 2021 10:43

May 31, 2021

Voices of Peterloo

Video performances bring the people of Peterloo to life

The event known to history as the

Peterloo Massacre

took place on August 16, 1819, when a large gathering of working class men, women and children was illegally attacked and dispersed. They had come to hear the famous radical orator Henry Hunt speak about parliamentary reform and had assembled peacefully in their thousands in St. Peter's field in the industrial city of Manchester. Manchester at that time

had no parliamentary

representation at all, let alone votes for working people.  The magistrates of Manchester, watching the assembly from an upstairs window, panicked and sent a troop of undisciplined and possibly drunk Yeoman Cavalry into the crowd to arrest Hunt before he could speak. The cavalry, composed of the sons and social peers of local mill owners, decided to confiscate the banners from the assembly, and they pushed their way into the tightly-packed crowd, hacking with their swords. Mayhem ensued, hundreds were injured and at least 19 were killed.

The magistrates of Manchester, watching the assembly from an upstairs window, panicked and sent a troop of undisciplined and possibly drunk Yeoman Cavalry into the crowd to arrest Hunt before he could speak. The cavalry, composed of the sons and social peers of local mill owners, decided to confiscate the banners from the assembly, and they pushed their way into the tightly-packed crowd, hacking with their swords. Mayhem ensued, hundreds were injured and at least 19 were killed.

The melee became known as "Peterloo" in a mocking reference to Waterloo, contrasting the soldiers at Waterloo with the brutality of the Yeoman cavalry who attacked defenseless people. I included the Peterloo Massacre in the final book of my Mansfield Trilogy. After researching the original accounts of the massacre and the events leading up to that day, I felt that there were sincere and well-meaning people on both sides as well as people determined to manipulate public opinion by pushing their own agendas. I did not see it simply as Goodies (the working class) vs the Baddies (the government and the capitalist mill-owners).

Speaking for myself, I am more interested in understanding the point of view of the authorities than I am in condemning them. Plus, I wanted to represent the views of both sides in my novel, not create a one-sided piece of agitprop like Mike Lee's Peterloo movie of 2018. "Unhappily, for a long series of years, but since the commencement of the French Revolution, a malignant spirit has been abroad in the country, seeking to ally itself with every cause of national difficulty and distress... it has employed itself in exaggerating calamity and fomenting discontent... a very large proportion of them indeed have parliamentary reform in their mouths but rebellion and revolution in their hearts."

-- Lord Sidmouth, speaking of the radical movement. I just learned about a YouTube series from the National Archives UK; 18 brief videos giving the voices of government officials, Manchester locals, newspaper reporters, and the working class activists, which gives a sample of what people were thinking and saying before, during, and after the Peterloo Massacre. I had read many of these accounts before, but it's interesting to hear them performed by excellent actors and actresses.

In addition to being fascinating source material, these videos are great for people (like me) who love a good, long rolling 19th century sentence and 19th century modes of expression. The series includes the correspondence of government officials who were worried about radical uprisings. There had been reports of working men meeting in common lands and engaging in drill practice in a military fashion. Many feared the country was on the brink of revolution, and people hadn't forgotten the horrors of the French Revolution. Fears of instability and anarchy made it easy to paint all reformers as dangerous radicals.

The government of the day used spies to attend radical meetings and sometimes used agent provocateurs, just as the United States government infiltrated the radical movements of the sixties. Here is a very entertaining letter from travelling actors, offering to spy for the government and report any seditious activity. "Educated for superior professions, we, from various circumstances, have adopted the stage for sustenance." They explain that their sympathies are with the government but they can mix unsuspected with the working class. ""We could prove beneficial in stemming the torrent of insurgency..."

#18 is one of two readings in this video series (the other is #10) where the re-enactor portrays his character as a sneering, evil, Bad Guy. In real life, most people believe they are acting out of good intentions, even if they are deluding themselves. Law enforcement and keeping the peace was a very different matter back then because it was conducted by amateurs. The magistrates of Manchester were propertied gentlemen of the area. It was their duty to act like a grand jury in hearing criminal cases, dealing with minor matters themselves and deciding who should be kept in custody for the quarterly assizes. They were the eyes and ears on the ground and at this time, the gentry were spooked about the possibility of bloody revolution breaking out across the country. It was legal for the people to hold meetings and to draw up petitions, but there had been some vandalism and rioting in Manchester in the past and furthermore, this assembly was on a scale unheard of in England to that time -- perhaps 60,000 people. Therefore, the prospect of this massive rally was worrisome -- what if turned into a riot? And rightly or wrongly, the magistrates feared that it could, in the blink of an eye. As a modern parallel, consider how often experts have warned about an impending right-wing uprising in the United States and how differently a liberal or a conservative might react to that rumor. That might give you some idea of the frame of mind of the Manchester magistrates upon hearing that thousands of men were drilling in the fields in the communities outside the city.

If the crowd did get out of hand and started smashing, looting and burning, there was no such thing as a professional, trained police force in those days. The magistrates relied on deputy constables (ordinary men sworn into service for the occasion) and amateur militia. This all led to disaster at Peterloo. The chief constable (a nasty bully who was despised by the working class people of Manchester) was ordered to go through the crowd and arrest Henry Hunt before he could even begin to speak. He refused to do it without armed backup. So the magistrates summoned the local yeoman cavalry, who were waiting nearby in case of trouble on the day of the rally. There was a professional newspaperman, John Tyas, present on the hustings that day. He reports Henry Hunt gave himself up peaceably. Then some of the cavalry shouted, "have at their flags" and rode into the crowd. "This set the people running in all directions... the Manchester yeomanry lost all command of temper." "Was that meeting at Manchester an unlawful assembly? We believe not... Was anything done at this meeting before the cavalry rode in upon it, contrary to the law or in breach of the peace? No such circumstances are recorded in any of the statements which have yet reached our hands." Here is the petition of Mary Fildes, who was on the platform with Henry Hunt at the rally. She was a working-class woman and the president of the Manchester Female Reform Society. She was holding one of the banners (inscribed with slogans asking for political reform) and she was attacked by the cavalry. Like the other Manchester attendees, she reports that the cavalry attacked the people without provocation.

The magistrates later testified that they thought it was the cavalrymen, individually surrounded on all sides by thousands of angry people, who were the ones in danger of harm, and that's why they called up additional troops to rescue them. However it happened, panic ensued and I believe most of the injuries were sustained by people rushing to get away. Although yes, some of the cavalry were deliberately attacking the crowd with edge of their swords, not the flat.

Accounts of what actually happened at Peterloo varied, as did the reactions. In the aftermath, the government cracked down severely on civil liberties, suspending habeas corpus for a time.

It remains a mystery to me why the magistrates, having allowed the assembly to happen, (they had already cancelled and forbidden a previous meeting) chose to cut it short just as it was beginning, before there was any sign of trouble whatsoever. Because of course this caused frustration and anger in the crowd. The magistrates broke up a legal and peaceful assembly -- but the government had to stand by them after the fact. Below is an excerpt from a speech by George, Lord Canning in the house on November 24, 1819, defending the decision of the Magistrates. He also mentions a technique I think is still prevalent today in political life. George, Lord Canning ( 1770 – 1827) Here is an earlier blog post in my Clutching My Pearls series, discussing Jane Austen's attitude toward the militia and that conversation about a riot in London in Northanger Abbey.

George, Lord Canning ( 1770 – 1827) Here is an earlier blog post in my Clutching My Pearls series, discussing Jane Austen's attitude toward the militia and that conversation about a riot in London in Northanger Abbey.

This BBC In Our Time radio podcast explains some of the nuances of this period of history; the authorities were coping with the war and its aftermath, and not every working-class person held radical views.

The magistrates of Manchester, watching the assembly from an upstairs window, panicked and sent a troop of undisciplined and possibly drunk Yeoman Cavalry into the crowd to arrest Hunt before he could speak. The cavalry, composed of the sons and social peers of local mill owners, decided to confiscate the banners from the assembly, and they pushed their way into the tightly-packed crowd, hacking with their swords. Mayhem ensued, hundreds were injured and at least 19 were killed.

The magistrates of Manchester, watching the assembly from an upstairs window, panicked and sent a troop of undisciplined and possibly drunk Yeoman Cavalry into the crowd to arrest Hunt before he could speak. The cavalry, composed of the sons and social peers of local mill owners, decided to confiscate the banners from the assembly, and they pushed their way into the tightly-packed crowd, hacking with their swords. Mayhem ensued, hundreds were injured and at least 19 were killed. The melee became known as "Peterloo" in a mocking reference to Waterloo, contrasting the soldiers at Waterloo with the brutality of the Yeoman cavalry who attacked defenseless people. I included the Peterloo Massacre in the final book of my Mansfield Trilogy. After researching the original accounts of the massacre and the events leading up to that day, I felt that there were sincere and well-meaning people on both sides as well as people determined to manipulate public opinion by pushing their own agendas. I did not see it simply as Goodies (the working class) vs the Baddies (the government and the capitalist mill-owners).

Speaking for myself, I am more interested in understanding the point of view of the authorities than I am in condemning them. Plus, I wanted to represent the views of both sides in my novel, not create a one-sided piece of agitprop like Mike Lee's Peterloo movie of 2018. "Unhappily, for a long series of years, but since the commencement of the French Revolution, a malignant spirit has been abroad in the country, seeking to ally itself with every cause of national difficulty and distress... it has employed itself in exaggerating calamity and fomenting discontent... a very large proportion of them indeed have parliamentary reform in their mouths but rebellion and revolution in their hearts."

-- Lord Sidmouth, speaking of the radical movement. I just learned about a YouTube series from the National Archives UK; 18 brief videos giving the voices of government officials, Manchester locals, newspaper reporters, and the working class activists, which gives a sample of what people were thinking and saying before, during, and after the Peterloo Massacre. I had read many of these accounts before, but it's interesting to hear them performed by excellent actors and actresses.

In addition to being fascinating source material, these videos are great for people (like me) who love a good, long rolling 19th century sentence and 19th century modes of expression. The series includes the correspondence of government officials who were worried about radical uprisings. There had been reports of working men meeting in common lands and engaging in drill practice in a military fashion. Many feared the country was on the brink of revolution, and people hadn't forgotten the horrors of the French Revolution. Fears of instability and anarchy made it easy to paint all reformers as dangerous radicals.

The government of the day used spies to attend radical meetings and sometimes used agent provocateurs, just as the United States government infiltrated the radical movements of the sixties. Here is a very entertaining letter from travelling actors, offering to spy for the government and report any seditious activity. "Educated for superior professions, we, from various circumstances, have adopted the stage for sustenance." They explain that their sympathies are with the government but they can mix unsuspected with the working class. ""We could prove beneficial in stemming the torrent of insurgency..."

#18 is one of two readings in this video series (the other is #10) where the re-enactor portrays his character as a sneering, evil, Bad Guy. In real life, most people believe they are acting out of good intentions, even if they are deluding themselves. Law enforcement and keeping the peace was a very different matter back then because it was conducted by amateurs. The magistrates of Manchester were propertied gentlemen of the area. It was their duty to act like a grand jury in hearing criminal cases, dealing with minor matters themselves and deciding who should be kept in custody for the quarterly assizes. They were the eyes and ears on the ground and at this time, the gentry were spooked about the possibility of bloody revolution breaking out across the country. It was legal for the people to hold meetings and to draw up petitions, but there had been some vandalism and rioting in Manchester in the past and furthermore, this assembly was on a scale unheard of in England to that time -- perhaps 60,000 people. Therefore, the prospect of this massive rally was worrisome -- what if turned into a riot? And rightly or wrongly, the magistrates feared that it could, in the blink of an eye. As a modern parallel, consider how often experts have warned about an impending right-wing uprising in the United States and how differently a liberal or a conservative might react to that rumor. That might give you some idea of the frame of mind of the Manchester magistrates upon hearing that thousands of men were drilling in the fields in the communities outside the city.

If the crowd did get out of hand and started smashing, looting and burning, there was no such thing as a professional, trained police force in those days. The magistrates relied on deputy constables (ordinary men sworn into service for the occasion) and amateur militia. This all led to disaster at Peterloo. The chief constable (a nasty bully who was despised by the working class people of Manchester) was ordered to go through the crowd and arrest Henry Hunt before he could even begin to speak. He refused to do it without armed backup. So the magistrates summoned the local yeoman cavalry, who were waiting nearby in case of trouble on the day of the rally. There was a professional newspaperman, John Tyas, present on the hustings that day. He reports Henry Hunt gave himself up peaceably. Then some of the cavalry shouted, "have at their flags" and rode into the crowd. "This set the people running in all directions... the Manchester yeomanry lost all command of temper." "Was that meeting at Manchester an unlawful assembly? We believe not... Was anything done at this meeting before the cavalry rode in upon it, contrary to the law or in breach of the peace? No such circumstances are recorded in any of the statements which have yet reached our hands." Here is the petition of Mary Fildes, who was on the platform with Henry Hunt at the rally. She was a working-class woman and the president of the Manchester Female Reform Society. She was holding one of the banners (inscribed with slogans asking for political reform) and she was attacked by the cavalry. Like the other Manchester attendees, she reports that the cavalry attacked the people without provocation.

The magistrates later testified that they thought it was the cavalrymen, individually surrounded on all sides by thousands of angry people, who were the ones in danger of harm, and that's why they called up additional troops to rescue them. However it happened, panic ensued and I believe most of the injuries were sustained by people rushing to get away. Although yes, some of the cavalry were deliberately attacking the crowd with edge of their swords, not the flat.

Accounts of what actually happened at Peterloo varied, as did the reactions. In the aftermath, the government cracked down severely on civil liberties, suspending habeas corpus for a time.

It remains a mystery to me why the magistrates, having allowed the assembly to happen, (they had already cancelled and forbidden a previous meeting) chose to cut it short just as it was beginning, before there was any sign of trouble whatsoever. Because of course this caused frustration and anger in the crowd. The magistrates broke up a legal and peaceful assembly -- but the government had to stand by them after the fact. Below is an excerpt from a speech by George, Lord Canning in the house on November 24, 1819, defending the decision of the Magistrates. He also mentions a technique I think is still prevalent today in political life.

George, Lord Canning ( 1770 – 1827) Here is an earlier blog post in my Clutching My Pearls series, discussing Jane Austen's attitude toward the militia and that conversation about a riot in London in Northanger Abbey.

George, Lord Canning ( 1770 – 1827) Here is an earlier blog post in my Clutching My Pearls series, discussing Jane Austen's attitude toward the militia and that conversation about a riot in London in Northanger Abbey.This BBC In Our Time radio podcast explains some of the nuances of this period of history; the authorities were coping with the war and its aftermath, and not every working-class person held radical views.

Published on May 31, 2021 00:00

May 27, 2021

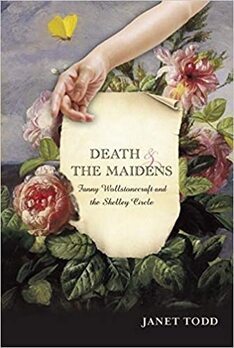

Book Review: Death and the Maidens

Death and the Maidens: Fanny Wollstonecraft and the Shelley Circle, by Janet Todd "In 1816 Shelley’s 21-year-old wife Harriet, whom he had deserted for Godwin’s daughter Mary, committed suicide. Her death came only a few weeks after 22-year-old Fanny’s. In the world of pragmatic compromise envisaged by Jane Austen at about the same time, enthusiastic Harriet as Marianne Dashwood from Sense & Sensibility should have lived to find a kinder man, while compassionate Fanny could and should have gained the rewards earned by her namesake Fanny Price in Mansfield Park. Instead both encountered Shelley’s Utopian absolutism."

Not the current cover, but this one's prettier! This is the story of the famous Shelley/Wollstonecraft/Godwin romance/scandal, told with an emphasis on two young women who were caught between idealistic and unrealistic Romantic anarchism on the one hand and an unforgiving social code on the other. One of the things that make this true story so fascinating to me is its applicability to the "Let's live in a commune" "free love" resurgence of the late 1960's and 70's which also ended mostly in squalor and broken relationships.

Not the current cover, but this one's prettier! This is the story of the famous Shelley/Wollstonecraft/Godwin romance/scandal, told with an emphasis on two young women who were caught between idealistic and unrealistic Romantic anarchism on the one hand and an unforgiving social code on the other. One of the things that make this true story so fascinating to me is its applicability to the "Let's live in a commune" "free love" resurgence of the late 1960's and 70's which also ended mostly in squalor and broken relationships.

Fanny Wollstonecraft was Mary Wollstonecraft's illegitimate daughter by a faithless lover, and Harriet Westbrook Shelley was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley's first wife. There are, I believe, no surviving portraits of either of them.

Poor Fanny grew up in a blended household. Her step-father was the philosopher William Godwin. Mary Wollstonecraft was briefly his lover, then his wife. She died after giving birth to Mary, the future author of Frankenstein. Godwin later married a neighbor who had two children by two different fathers, leading to a household in which none of the six children had the same set of parents.

Janet Todd uses the surviving written records and makes intelligent surmises to fill in the gaps, recreating the emotions and attitudes of the unhappy, cash-pinched household on Skinner Street and the fatal last journey that Fanny took before she killed herself.

"Her voice did quiver as we parted," wrote Shelley, but he never confessed the details of that last conversation. Based on the available evidence, it is very likely that Fanny was in love with Shelley. Todd also traces what may be some faint lingering remembrances of Fanny in the later novels of her half-sister Mary Godwin Shelley.

Pretty young Harriet Westbrook, Shelley's first wife, has had her defenders and detractors and her story is also told here, including what her detractors said about her final months, versus what is actually known. Harriet fell under Shelley's spell when she was a teenager. I have sometimes thought about her emotional journey; she was a runaway bride at 16 and a suicide at 21. She would have started out idolizing her husband and believing that he was destined to do great things with his poetry, and bring about a new world based on equality and freedom. She enthusiastically adopted his political views and tried to learn Greek and Latin. Then she would have slowly realized that he could not handle money or make rational decisions about where to live or who to live with. Perhaps she came to see that his judgement about people was not infallible; or at least, she might have noticed that he had a tendency to go from enthusiastically praising someone to scornfully rejecting them. Certainly once she became a mother she had to come down from Shelley's elevated spiritual plane and worry about practical matters, such as paying the bills.

I also enjoyed learning additional details about the school teacher Eliza Hitchener, who went from being idolized to being detested by Shelley, as well as more about Mary Wollstonecraft's sisters Eliza and Everina who had to distance themselves from their sister's reputation, and what this meant for their niece Fanny.

This might not be the book you turn to for an introduction to the story of Shelley and his circle, nor, I think, is it intended to be. Its focus is to respectfully and sympathetically tell the story of Fanny and Harriet, who certainly deserve to be remembered.

Not the current cover, but this one's prettier! This is the story of the famous Shelley/Wollstonecraft/Godwin romance/scandal, told with an emphasis on two young women who were caught between idealistic and unrealistic Romantic anarchism on the one hand and an unforgiving social code on the other. One of the things that make this true story so fascinating to me is its applicability to the "Let's live in a commune" "free love" resurgence of the late 1960's and 70's which also ended mostly in squalor and broken relationships.

Not the current cover, but this one's prettier! This is the story of the famous Shelley/Wollstonecraft/Godwin romance/scandal, told with an emphasis on two young women who were caught between idealistic and unrealistic Romantic anarchism on the one hand and an unforgiving social code on the other. One of the things that make this true story so fascinating to me is its applicability to the "Let's live in a commune" "free love" resurgence of the late 1960's and 70's which also ended mostly in squalor and broken relationships.Fanny Wollstonecraft was Mary Wollstonecraft's illegitimate daughter by a faithless lover, and Harriet Westbrook Shelley was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley's first wife. There are, I believe, no surviving portraits of either of them.

Poor Fanny grew up in a blended household. Her step-father was the philosopher William Godwin. Mary Wollstonecraft was briefly his lover, then his wife. She died after giving birth to Mary, the future author of Frankenstein. Godwin later married a neighbor who had two children by two different fathers, leading to a household in which none of the six children had the same set of parents.

Janet Todd uses the surviving written records and makes intelligent surmises to fill in the gaps, recreating the emotions and attitudes of the unhappy, cash-pinched household on Skinner Street and the fatal last journey that Fanny took before she killed herself.

"Her voice did quiver as we parted," wrote Shelley, but he never confessed the details of that last conversation. Based on the available evidence, it is very likely that Fanny was in love with Shelley. Todd also traces what may be some faint lingering remembrances of Fanny in the later novels of her half-sister Mary Godwin Shelley.

Pretty young Harriet Westbrook, Shelley's first wife, has had her defenders and detractors and her story is also told here, including what her detractors said about her final months, versus what is actually known. Harriet fell under Shelley's spell when she was a teenager. I have sometimes thought about her emotional journey; she was a runaway bride at 16 and a suicide at 21. She would have started out idolizing her husband and believing that he was destined to do great things with his poetry, and bring about a new world based on equality and freedom. She enthusiastically adopted his political views and tried to learn Greek and Latin. Then she would have slowly realized that he could not handle money or make rational decisions about where to live or who to live with. Perhaps she came to see that his judgement about people was not infallible; or at least, she might have noticed that he had a tendency to go from enthusiastically praising someone to scornfully rejecting them. Certainly once she became a mother she had to come down from Shelley's elevated spiritual plane and worry about practical matters, such as paying the bills.

I also enjoyed learning additional details about the school teacher Eliza Hitchener, who went from being idolized to being detested by Shelley, as well as more about Mary Wollstonecraft's sisters Eliza and Everina who had to distance themselves from their sister's reputation, and what this meant for their niece Fanny.

This might not be the book you turn to for an introduction to the story of Shelley and his circle, nor, I think, is it intended to be. Its focus is to respectfully and sympathetically tell the story of Fanny and Harriet, who certainly deserve to be remembered.

Published on May 27, 2021 00:00

May 20, 2021

CMP#49 18th Century Adventurous Wives

[image error] Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series.

Elizabeth Gunning Plunkett overcame an early scandal -- or perhaps she used her notoriety -- to become an author. This discussion of her novel The Gypsy Countess (1799) contains spoilers. An Innovator in Unfolding Plots -- plus, 18th Century Girl Power! When The Gypsy (or Gipsey or Gipsy) Countess was published in 1799, Jane Austen had already written the first drafts of what would become Pride & Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility, and Northanger Abbey, but she was a dozen years away from becoming a published author. The style, tone, and realism of Austen, versus the melodrama of The Gypsy Countess, really underscores how Austen was radically different from her contemporaries.

When The Gypsy (or Gipsey or Gipsy) Countess was published in 1799, Jane Austen had already written the first drafts of what would become Pride & Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility, and Northanger Abbey, but she was a dozen years away from becoming a published author. The style, tone, and realism of Austen, versus the melodrama of The Gypsy Countess, really underscores how Austen was radically different from her contemporaries.

The Gypsy Countess is not an all-the-way Gothic novel in the sense of having haunted houses and evil priests, but it pulsates with mystery and melodrama. The youngest of the three heroines, Ellen Cary, weeps her way through the book. To be fair, she has been separated from the man she loves by treachery and she’s being kept captive in an insane asylum. There are not one but two evil step-mothers, and as is typical, many of the plot twists rely upon coincidental encounters.

Having said that, I have not come to disparage The Gypsy Countess but to praise it. Two aspects of this book really deserve some credit, I think. The first is the independence and wit of the main two female characters. Chawton House, the Center for Early Women's Writing (and former home of Jane Austen's wealthy brother) just held a virtual conference on the topic of "Adventurous Wives." The keynote address talked about some of the adventurous 18th century women who showed intrepidity and courage.

I nominate Julia, the Gypsy Countess of Gunning's story, to the list of adventurous literary wives. She is the one who rescues her friend Ellen from the insane asylum. Although each of the three heroines in the book is madly and deeply in love with her respective sweethearts, the men they love don’t play any role in the rescue and not much of a role in the revelations of the plot. Gunning keeps them offstage for most of the story. it’s the strong relationships between the three women that are in the foreground throughout the story.

Julia and her sister-in-law Rosanna are married and wealthy. This means they have more agency than an unmarried heroine would. They can travel alone, (as long as they have an escort of male servants.) They can make things happen. They can generously reward the poor but honest people who help them. The notable feature of The Gipsy Countess is the way Gunning handles her multiple storylines. The Gipsy Countess is an epistolary novel. The biggest best-sellers of the 18th century were epistolary novels such as Samuel Richardson’s novels Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison. But by the end of the century, the epistolary novel was dying out.

We learn from Julia's first letters to her brother Henry that they recently found each other after a long separation. He's going back to India and she’s agreed to write out the story of her life and send it on the next ship bound for India. This scenario is the framing device used to introduce a complicated plot, with several subplots which involve both the past and the present: The story of how Julia was kidnapped by gypsies as a child, with an additional subplot, the backstory of Margaret, the Queen of the Gypsies.The story of the Ossington family, which includes Rosanna, and eventually, the story of Julia’s courtship and marriage.The perils of their beautiful neighbour Ellen Cary, which includes Ellen’s backstory in India, andThe present day story of Julia’s reunion with her brother Henry and her married life today. There is an extra bonus romantic happy ending and another long-lost sibling tacked on to the end.

There is an extra bonus romantic happy ending and another long-lost sibling tacked on to the end.

Many 18th century novels have mysteries and undisclosed secrets, usually about the true parentage of the heroine or hero, that sort of thing. But I haven’t seen a novel of this vintage that reveals the past bit by bit to explain the present in the way this novel does. Tristram Shandy has a lot of digressions, but plot isn't important in Tristram Shandy. Here, plot is paramount.

In addition to switching rapidly between the storylines, the story also switches between narrators. Julia divides the letter-writing duties with her sister-in-law; For example, when little Julia is rescued by Lord Ossington only to disappear the next morning, the narrator is Rosanna. This heightens the drama, because Rosanna tells the story from her point of view – she is a young girl who doesn’t know where her new friend has gone. If Julia had told that part of the story, there would be no suspense. Later, the third heroine, young Ellen, is added to the medley of letter-writers.

However, all this switching between plots and narrators, alternating between the past and the present, was too much for a contemporary critic: “The first two volumes of this novel contain too much dissertation and digression; and narratives, little connected, displace each other by turns, as if for the express purpose of preventing a continuation of interest.”

Critic Godfrey Frank Singer, writing in 1933, didn’t like it either: “the intermingling of the story of the present with the story of the past becomes so confused that the reader is at a loss to make out just what is taking place.”

If you think all this is difficult on the reader, imagine what it was like for Henry, the supposed recipient of all these letters, who just wants Julia to tell him what happened after she was abducted by gypsies. Plus, halfway into the narrative, he learns that Julia’s neighbor is, coincidentally, the girl he has loved and lost. And she’s disappeared without a trace. If we are tempted to skip to the end to find out what happened, I'm sure Henry must have skipped to the end of the huge bundle of letters his sister prepared for him.

But I think Elizabeth Gunning deserves credit for devising something much more complicated than a straightforward narrative or a even a narrative with a framing device or an inset story. I’ve never come across such an ambitious exposition scheme in an 18th century novel.

Singer, the 1933 critic, also adds, “Miss Gunning undoubtedly wins for herself in this novel the distinction of being the most long-winded writer in the eighteenth century after Richardson himself.” The long-windedness has to do with the emphasis that these novels of sentiment place on the emotions of the characters and the emotional identification the reader was supposed to feel for them. Julia and Rosanna and Ellen often interrupt their narration to explain, at some length, that they are so excited or happy or anxious or miserable that they can scarcely write coherently to explain what has just occurred.

The emphasis on emotions means there's a lot of tears, trembling, turning of a deathly paleness, followed by cheeks turning scarlet as heroines (their younger, unmarried selves) are covered with "confusion." And these strong emotions were displayed by some of the male characters as well. As James Boswell observed: "It is peculiar to the passion of Love, that it supports with an exemption from disgrace, those weaknesses in a man which upon any other occasion would render him utterly contemptible." In addition to death, coincidence and misunderstanding, Gunning uses lingering illness and fever a number of times when she needs to delay a plot resolution.

But Gunning’s goal wasn’t to achieve realism or probability. Her goal was to write a dramatic tale with lots of plot twists and to wring the maximum amount of emotion out of her story. And when the chips are down, Julia and Rosanna behave with courage and good sense.

If you are looking for strong, loyal, heroines in your 18th century literature, The Gypsy Countess and its author deserve respect. Gunning’s very sophisticated plot structure makes The Gypsy Countess an interesting footnote in the history of the novel. The Gunning Scandal Notes:

The Gunning Scandal Notes:

The fear of abduction by gypsies was the "stranger danger" of the 18th century. Incredibly, we are told that Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, the "Invisible Hand" guy, was abducted by gypsies as a child. In an earlier blog post I talked about 18th century attitudes towards the Roma. In this novel, Gunning is really rather friendly toward the gypsies. Or rather, it turns out that Margaret, Queen of the Gypsies, isn’t a gypsy after all. Cassandra, the gypsy who looks after Julia as a child, is described very affectionately. There are no hard feelings over the kidnapping and no retribution is exacted.

Elizabeth Gunning moved in high society more than Austen ever did, and her backstory is as interesting and almost as improbable as the plots of her novels. As a teenager, she was involved in a mysterious scandal involving fake love letters that has never been explained. Her mother was also a novelist.

The Gypsy Countess is one of the books I highlighted in my blog post about authors who used colonialism, empire and making large fortunes for plot purposes, not as a social or political commentary. India had plot value as a remote and exotic location where characters can disappear until you need them back again. In The Gypsy Countess we hear about the cruel and selfish behaviour of several Indian “nabobs” (people who made their fortunes in India), but the cruelties described are those visited on the fair and defenseless Ellen, not cruelties to the natives of India. The knock against nabobs is that they are vulgar upstarts with more money than class.

One of the nabobs gets in trouble for trading on the black market. He wrote that he was “Conscious that I had not confined my efforts to acquiring wealth exactly within the bounds prescribed by the Company… though I could have named a thousand precedents who had beaten the same forbidden ground with myself.” Gunning’s readers would have understood the reference to the East India Company, the monopoly it then held on trade out of India, and the corruption endemic to the enterprise. In those days a trip to India took about six months. You sailed all the way down around the tip of South Africa, with a stop at St. Helena on the way there and back.

For more about the epistolary novel, John Mullan and some other people have an interesting discussion in this BBC "In Our Time" podcast.

There was one passage in The Gypsy Countess that reminded me of Jane Austen’s juvenilia, when Austen wrote, “run mad as often as you chuse, but do not faint” because the habit is sadly fatal. Julia needs to give Ellen the good news that Henry is on his way -– he’s not going to India after all--but Ellen is in a feeble state after being rescued from the insane asylum. “I shall content myself with the credit of having made the communication with so much adroitness, that although my lovely sister-elect frequently changed colour, and sometimes shed tears, she neither fainted or was hysterical, of which, on both accounts, I had entertained very uneasy suspicions, her strength being in no condition to contend with such violent assailants.” If you haven’t read Austen’s parody of the sentimental novel, Love and Freindship , it’s hilarious. Austen sends up the emotionality, the elevated sentiments, and the improbable plot twists of novels of sentiment. I think she enjoyed novels like The Gipsy Countess, while laughing at them, too. Professor Elaine Chalus, the keynote speaker for the Adventurous Wives conference, is an expert on the life and diaries of Elizabeth Wynne Fremantle. Betsey Fremantle and her husband have a walk-on part in my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady, and I wish I could have found a way to include their backstory. Betsy was living with her family in Livorno, Italy, when Napoleon invaded. The family was rescued by Captain Thomas Fremantle and and he and Betsy were married the following year.

Elizabeth Gunning Plunkett overcame an early scandal -- or perhaps she used her notoriety -- to become an author. This discussion of her novel The Gypsy Countess (1799) contains spoilers. An Innovator in Unfolding Plots -- plus, 18th Century Girl Power!