Lona Manning's Blog, page 24

January 26, 2021

CMP#26 Pictures of Perfection

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Some of Jane Austen's admirers are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. "Pictures of perfection, as you know, make me sick and wicked" "[Austen's] novels dramatize not social ills, but individual failings: vanity, greed, pride, selfishness, arrogance, folly. For all her humor and wit, she was a rigorous moralist. Adult life demanded adult behavior: self-awareness, propriety, kindness, good sense." --Robert Garnett

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Some of Jane Austen's admirers are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. "Pictures of perfection, as you know, make me sick and wicked" "[Austen's] novels dramatize not social ills, but individual failings: vanity, greed, pride, selfishness, arrogance, folly. For all her humor and wit, she was a rigorous moralist. Adult life demanded adult behavior: self-awareness, propriety, kindness, good sense." --Robert Garnett

In previous posts, I've discussed why I disagree with the notion that Austen promoted politically radical ideas. I’ve quoted and re-quoted that wisdom from Professor Garnett, above, because I think he gets at the heart of Jane Austen.

In previous posts, I've discussed why I disagree with the notion that Austen promoted politically radical ideas. I’ve quoted and re-quoted that wisdom from Professor Garnett, above, because I think he gets at the heart of Jane Austen.Of course Austen’s novels featured love stories -- they were novels, after all, not collections of sermons or texts on seafaring. However, she wasn't all about romance, nor was she trying to upend the social order. She believed in virtue, self-knowledge and self-control -- in other words, morality.

However, after reading Mary Waldron’s Jane Austen and the Fiction of Her Time, I am compelled to add a big “BUT." I think Waldron is correct that Austen did not care for authors who bashed their readers over the head with their morality and their beliefs.

Her aversion to this writing style wasn't because she thought preachiness was bad for book sales. For example, she was critical of Hannah More and Mary Brunton, who easily outsold her (in her lifetime.) (However popular in their day, Hannah More's Coelebs in Search of a Wife and Mary Brunton’s Self-Control are best known today for what Austen said about them in her private letters, a pretty amazing reversal of fame.)

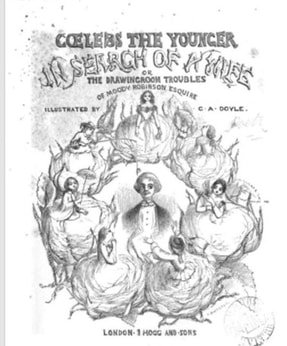

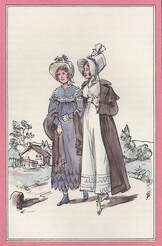

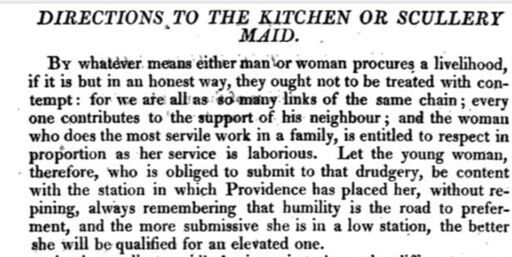

Coelebs was so popular it spawned several sequels and imitations As Mary Waldron explains, Hannah More's best-selling Coelebs in Search of a Wife, is “tiresomely prescriptive” and features a hero who “is about as improbable as a man of twenty-four… could be.” Charles engages in a coolly systematic hunt for a wife who will meet his expectations and Christian principles, but can’t find a suitable girl in the fleshpots of London. He goes to visit Mr. Stanley, his late father’s old friend, and meets Stanley’s daughter Lucilla. Lucilla is the perfect, pious, modest, charitable, feminine, hard-working Regency girl. She is in fact faultless, although it would have been a sin of vanity for her to think so.

Coelebs was so popular it spawned several sequels and imitations As Mary Waldron explains, Hannah More's best-selling Coelebs in Search of a Wife, is “tiresomely prescriptive” and features a hero who “is about as improbable as a man of twenty-four… could be.” Charles engages in a coolly systematic hunt for a wife who will meet his expectations and Christian principles, but can’t find a suitable girl in the fleshpots of London. He goes to visit Mr. Stanley, his late father’s old friend, and meets Stanley’s daughter Lucilla. Lucilla is the perfect, pious, modest, charitable, feminine, hard-working Regency girl. She is in fact faultless, although it would have been a sin of vanity for her to think so.Very little happens to, or between, Charles and Lucilla. Most of the action involves side characters about whom Mr. Stanley moralizes. He talks about his neighbours to illustrate his opinions about religion and raising children, which, under any other circumstances, would make him the most judgmental, inveterate old gossip you’ve ever met in your life.

I actually rather like Hannah More’s writing – she could turn a deft phrase -- and I admire her as a self-made woman, an educator, an abolitionist, and a philanthropist. But however much I admire More, Coelebs is not her best work, best-seller though it was. Coelebs may be a novel, technically, but all the characters, especially Lucilla’s father, are just animated points of view, propounding More's doctrines of Evangelical Anglicanism. (For more about Coelebs, check out this helpful blog). (I've written another comparison of Mansfield Park and Coelebs in this post).

Austen could not accept making the story in the novel subservient to the moralizing, because you end up with a story inhabited by people who bear no relation to real, fallible, humans. “Pictures of perfection, as you know,” she told her niece, “make me sick and wicked.” She thought that faultless heroines like Lucilla Stanley were too far removed from reality, sometimes comically so. And when you start out with perfect characters, there is no opportunity for character development.

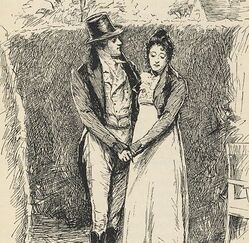

Laura Montreville threatened by Captain Hargrave in "Self Control" Unrealistic situations, no less than unrealistic characters, drew Austen’s derision.

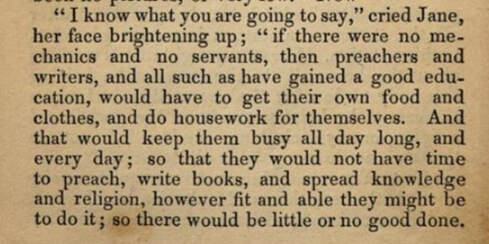

Laura Montreville threatened by Captain Hargrave in "Self Control" Unrealistic situations, no less than unrealistic characters, drew Austen’s derision. In an early chapter of Brunton's Self-Control, the virtuous Laura Montreville has fallen for the passionate Captain Hargrave. She's horrified when she realizes he's not proposing marriage to her, but asking her to be his mistress.

“No words can express her feelings, when, the veil thus rudely torn from her eyes, she saw her pure, her magnanimous Hargrave—the god of her idolatry—degraded to a sensualist, a seducer. Casting on him a look of mingled horror, dismay, and anguish, she exclaimed, “Are you so base?” and, freeing herself, with convulsive struggle, from his grasp, sank without sense or motion to the ground."

Laura shows herself more capable of self-preservation when Hargrave has her abducted and taken by ship to Canada. She stays calm when she hears a rattlesnake in the forest, and she escapes the clutches of her would-be ravisher by paddling down-river in a canoe. Believing that she has perished in the river, Hargrave kills himself in remorse.

In the second edition of Self-Control, Mary Brunton acknowledged that: “objections [have been] stated against the probability of some of the incidents. Had these censures been pointed at the [moral] lessons which the tale was intended to convey, the Author would have felt it was her duty, as well as her earnest desire, to remove them.”

Austen said of this book, “I am looking over Self Control again, & my opinion is confirmed of its’ being an excellently-meant, elegantly-written Work, without anything of Nature or Probability in it. I declare I do not know whether Laura’s passage down the American River, is not the most natural, possible, every-day thing she ever does.” Reading other people's novels, even silly ones, sharpened her own ideas of what a novel should be. As Waldron explains, "[Austen] created a new kind of novel which put all her predecessors and contemporaries more or less in the shade and ensured that her work outlived theirs."

When we compare Austen's novels to those of her contemporaries, we see that she is not unique as a moralist, but she is uniquely good as an author. Her prose is delightful, soothing, elegant, witty, almost hypnotic in its power to draw you in. Her situations are not fantastical. Her scope is domestic and intimate. Her moralizing is gentle, her authorial voice is detached, and her ideas are presented through an imaginative array of different and unique characters.

Instead of Laura and Lucilla, Austen gave the world the delightful, but fallible, Elizabeth Bennet and Emma Woodhouse, and the naïve Catherine Morland. They want to do the right thing, try to do the right thing, but make mistakes along the way. Anne Elliot quietly mourns the man she lost, and Fanny Price… well… Fanny Price -- is she a picture of perfection? We’ll take her up in the coming blog posts. Next post: She is never, ever, wrong. Many actors say that playing the conniving villain is more fun than playing the upright hero, and I think it is very entertaining to write villains as well! I enjoyed writing a short story based on Persuasion from the point of view of Mrs. Clay, the artful gold-digger, which appears in the Quill Ink anthology, Rational Creatures .

Published on January 26, 2021 00:00

January 20, 2021

CMP#25 Righteousness and Reticence

Implicit Values in Austen: Dignified silence Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series.

Implicit Values in Austen: Dignified silence Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series.

Pride and Prejudice 2012 stage production. Photo: Chicago Sun-Times In Jane Austen's time, a gentleman's reputation was so important that he sometimes risked his life for the sake of honour -- with pistols at dawn. Or, as in the case of Colonel Brandon, they dueled to punish someone else's dishonourable conduct.

Pride and Prejudice 2012 stage production. Photo: Chicago Sun-Times In Jane Austen's time, a gentleman's reputation was so important that he sometimes risked his life for the sake of honour -- with pistols at dawn. Or, as in the case of Colonel Brandon, they dueled to punish someone else's dishonourable conduct.However, the plot of Pride & Prejudice turns on another characteristic habit of English gentlemen: Darcy does not deign to explain his past dealings with Wickham. His reticence has consequences: too late, Darcy realizes that Wickham has prejudiced the mind of the woman he loves against him. Stung, he writes Elizabeth a long letter. After realizing she misjudged Darcy and Wickham, Elizabeth tells her sister Jane. They both decide to keep the whole matter to themselves, as Darcy would wish, and to preserve Wickham's character -- after all, he's leaving town anyway.

As Janeites will recall, when Elizabeth learns that Darcy was a witness to Wickham's forced marriage to Lydia, she writes to her aunt, begging for an explanation. Mrs. Gardiner explains that Darcy took the blame for Wickham's seduction of Lydia.

Now we get to the crux of the matter. As Mrs. Gardiner explains: "He generously imputed the whole to his mistaken pride, and confessed that he had before thought it beneath him to lay his private actions open to the world. His character was to speak for itself. He called it, therefore, his duty to step forward, and endeavour to remedy an evil which had been brought on by himself."

This is the "Pride" in "Pride and Prejudice." Darcy has carried his implacable pride too far, which is also why he totally botched his first proposal of marriage to Elizabeth. When they are happily reconciled, he tells her, "by you, I was properly humbled."

Darcy holds his reputation to be so unimpeachable that he will not descend to defend himself. Was this a common attitude at the time or was he unusually aloof?

I found a similar real-life reaction, under very different circumstances, when I was researching the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. This was an incident when thousands of working-class families attended a huge rally in Manchester. The local authorities -- landed gentlemen like Mr. Darcy who served as the town's magistrates and officials -- sent a troop of volunteer cavalry to assist in the arrest of the main speaker of the rally. Panic and bloodshed ensued.

I found a similar real-life reaction, under very different circumstances, when I was researching the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. This was an incident when thousands of working-class families attended a huge rally in Manchester. The local authorities -- landed gentlemen like Mr. Darcy who served as the town's magistrates and officials -- sent a troop of volunteer cavalry to assist in the arrest of the main speaker of the rally. Panic and bloodshed ensued.An indignant public was shocked at accounts of women and children being trampled down in the street or stabbed with bayonets. Francis Phillips, a gentleman who witnessed the incident and subsequently defended the magistrates, explained "it would be derogatory to the dignity of the Magistrates, who felt in the fullest degree the consciousness of rectitude… to descend to a defense of their conduct.”

I came across another fictional example of this kind of proud reticence in Dr. Thorne [1858] a novel by Anthony Trollope, in a passage about a professional feud between doctors: Dr Fillgrave responded in four lines, saying that on mature consideration he had made up his mind not to notice any remarks that might be made on him by Dr Thorne in the public press. The Greshamsbury doctor then wrote another letter, more witty and much more severe than the last; and as this was copied into the Bristol, Exeter, and Gloucester papers, Dr Fillgrave found it very difficult to maintain the magnanimity of his reticence. It is sometimes becoming enough for a man to wrap himself in the dignified toga of silence, and proclaim himself indifferent to public attacks; but it is a sort of dignity which it is very difficult to maintain. As well might a man, when stung to madness by wasps, endeavour to sit in his chair without moving a muscle, as endure with patience and without reply the courtesies of a newspaper opponent."

"where there is a real superiority of mind, pride will be always under good regulation.” Clearly, Darcy is not the only British gentleman who feels it would be beneath his dignity to respond to some idle slur on his character.

"where there is a real superiority of mind, pride will be always under good regulation.” Clearly, Darcy is not the only British gentleman who feels it would be beneath his dignity to respond to some idle slur on his character. In his influential work, A Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), the economist Adam Smith analyzed and explored human nature with observations of people and society. For example, he says we admire someone who reacts to the loss of a loved one with fortitude and self-command. (I think some of the reactions that he assumed were universal were in fact particularly British, such as the British admiration for stoicism and the stiff upper lip. In other cultures, you would be expected to wail loudly and tear your clothes upon the death of a loved one.)

In this passage, Smith explains that the virtuous and wise man might even disdain fame, so long as he approved of his own conduct:

"The love of just fame... is not unworthy even of a wise man. He sometimes, however, neglects and even despises it; and he is never more apt to do so when he has the most perfect assurance of the perfect propriety of his own conduct. His self-approbation, in this case, stands in need of no confirmation from the approbation of other men."

And just like Mary Bennet, Smith distinguishes between pride and vanity.

Smith says of the proud man: "When we compare them with [their critics] they may appear... very much above the common level. Where there is this real superiority, pride is frequently attended with many respectable virtues; with truth, with integrity, with a high sense of honour, with cordial and steady friendship, with the most inflexible firmness and resolution."

Does that sound like anyone we know?

We also learn from Northanger Abbey that it was a popular trope in 18th century novels for a heroine's reputation to be blighted by misunderstanding or rumor. Jane Austen satirizes this when Catherine Morland appears to be lacking a dance partner because John Thorpe keeps her waiting:

We also learn from Northanger Abbey that it was a popular trope in 18th century novels for a heroine's reputation to be blighted by misunderstanding or rumor. Jane Austen satirizes this when Catherine Morland appears to be lacking a dance partner because John Thorpe keeps her waiting:"To be disgraced in the eye of the world, to wear the appearance of infamy while her heart is all purity, her actions all innocence, and the misconduct of another the true source of her debasement, is one of those circumstances which peculiarly belong to the heroine's life, and her fortitude under it what particularly dignifies her character. Catherine had fortitude too; she suffered, but no murmur passed her lips." In addition to not deigning to respond to attacks on one's character, it was vulgar to hunger after fame. Jane Austen published her novels anonymously in her lifetime, and this is typically ascribed to the patriarchal system she lived in. But in the early days of the English novel, it was common for men as well as women to publish anonymously, and this often had to do with dignity and reticence. As Professor John Mullan explained on a BBC In Our Time program, "Writers who achieve popularity and fame have to go through all sorts of maneuvers to claim that they didn't mean it. Great writers of the early 18th century like Pope and Swift sometimes pretend that they didn't write a book or that it got published by accident." In his book Anonymity: a Secret History of English Literature, Mullan adds that in the 16th century, "Ambitious writers who did allow their work to be printed often exhibited reluctance or distaste."

Of the reticence of Jane Austen and other female writers, Mullan says: "Sometimes it is difficult to disentangle gender from class when encountering prejudices against publication. At a time when it was widely considered ungentlemanly for a man to publish under his own name, we should not suppose that clever women would have resented the requirement that they keep their names off what they write... It was in bad taste for a man to publish what he had composed, and doubly unacceptable for a woman."

For a final example of reacting to criticism with "silent contempt," we have the poet and author Anna Laetitia Barbould. She wrote an anti [Napoleonic] war poem, 1811, (which I quoted in my Remembrance Day blog post). When the poem was published, it received a sarcastic and condescending review, calling Barbould to task for writing about public affairs: "She has wandered from the course in which she was respectable and useful... an irresistible impulse of public duty [has] induced her to dash down her shagreen spectacles and her knitting needles and stray outside her domestic sphere of competence."

For a final example of reacting to criticism with "silent contempt," we have the poet and author Anna Laetitia Barbould. She wrote an anti [Napoleonic] war poem, 1811, (which I quoted in my Remembrance Day blog post). When the poem was published, it received a sarcastic and condescending review, calling Barbould to task for writing about public affairs: "She has wandered from the course in which she was respectable and useful... an irresistible impulse of public duty [has] induced her to dash down her shagreen spectacles and her knitting needles and stray outside her domestic sphere of competence."Barbould's friend, fellow author Maria Edgeworth, wrote to her: "I cannot describe to you the indignation or rather the disgust that we felt at the manner in which you are treated in the Quarterly Review... My father and I in the moment of provocation snatched up our pens to answer it, but a minute's reflexion convinced us that silent contempt is the best answer."

We don't know if Barbould agreed, or wished that Edgeworth had spoken up to defend her. Next post: Back to Mansfield Park In my novel A Marriage of Attachment, poor Fanny Price's character is attacked by a woman who is jealous of her. For more about my Mansfield Trilogy, click here.

Published on January 20, 2021 00:00

January 18, 2021

CMP#24 Does Austen care about land enclosure?

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. For some, recent interpretations of Austen appear to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. The Enclosure movement part 3: In my first post on land enclosure in Austen's time, I mostly talked about gypsies and whether the gypsies in Emma tell us anything about land enclosure. The second post looked at whether Mr. Knightley was a villain. In this final post on land enclosure, we'll look at two questions: Do we know how Austen felt about land enclosure? And, was it dangerous to oppose land enclosure? That is, would a person living in Austen's time get in trouble with the authorities, or even socially, for speaking out against land enclosure?

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. For some, recent interpretations of Austen appear to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. The Enclosure movement part 3: In my first post on land enclosure in Austen's time, I mostly talked about gypsies and whether the gypsies in Emma tell us anything about land enclosure. The second post looked at whether Mr. Knightley was a villain. In this final post on land enclosure, we'll look at two questions: Do we know how Austen felt about land enclosure? And, was it dangerous to oppose land enclosure? That is, would a person living in Austen's time get in trouble with the authorities, or even socially, for speaking out against land enclosure?

Gleaners look for stray grains of wheat, 1857. It's been a long time since the West experienced this kind of poverty We should understand that by Austen's time, enclosure was basically a fait accompli. Much of England's farmland was enclosed before Austen was born, including her home village of Steventon. If Highbury and Northanger Abbey and Uppercross were all real places, they likely would be places where the farmland had already been enclosed. According to the National Archives website, because enclosure happened here and there and gradually over centuries, this "piecemeal" conversion "ensured that opposition to the loss of rights was fragmented although there were various enclosure riots at places such as Charnwood Forest (1748-51), West Haddon (1765), Sheffield (1791), and Burton on Trent (1771-72)."

Gleaners look for stray grains of wheat, 1857. It's been a long time since the West experienced this kind of poverty We should understand that by Austen's time, enclosure was basically a fait accompli. Much of England's farmland was enclosed before Austen was born, including her home village of Steventon. If Highbury and Northanger Abbey and Uppercross were all real places, they likely would be places where the farmland had already been enclosed. According to the National Archives website, because enclosure happened here and there and gradually over centuries, this "piecemeal" conversion "ensured that opposition to the loss of rights was fragmented although there were various enclosure riots at places such as Charnwood Forest (1748-51), West Haddon (1765), Sheffield (1791), and Burton on Trent (1771-72)."

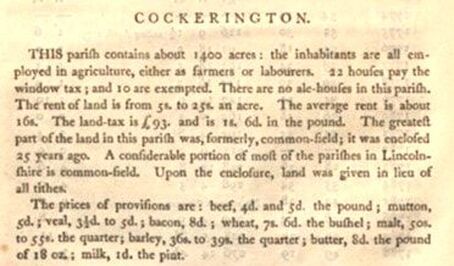

Excerpt from "The State of the Poor" by Sir Frederick Morton Eden, 1797 The clergyman of this parish received land instead of a yearly collection of tithe-produce. What do we know about Jane Austen's attitude toward land enclosure from her novels and letters? Was she pro-enclosure, indifferent, or worried about the effects on peasants and the change that enclosure wrought on Merrie Olde England?

Excerpt from "The State of the Poor" by Sir Frederick Morton Eden, 1797 The clergyman of this parish received land instead of a yearly collection of tithe-produce. What do we know about Jane Austen's attitude toward land enclosure from her novels and letters? Was she pro-enclosure, indifferent, or worried about the effects on peasants and the change that enclosure wrought on Merrie Olde England? Professor Celia Easton has carefully reviewed all of Austen's existing corpus for references to farming and enclosure. In an article for the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), Easton starts with the most explicit mention of enclosure, which is not in Emma, but in Sense & Sensibility. John Dashwood tells Elinor that he's enclosing Norland Common, and the cost of doing so is "a most serious drain" on his income. Later in the novel, the men talk about enclosure over their after-dinner drinks. Austen presents John Dashwood throughout the novel as a selfish and incredibly self-centred person, so his mention of enclosing Norland Common does sound like she disapproves of closing off the common land.

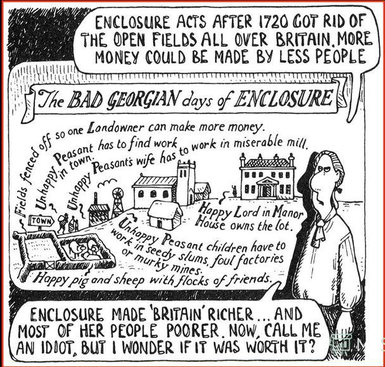

From a history page that is anti-enclosure, click on cartoon for more Next, Professor Easton looks at Mansfield Park. Mr. Rushworth plans to improve the landscaping at his estate. As well, Henry Crawford tells Edmund Bertram how he can fix up the parsonage at Thornton Lacey to look like a gentleman's house by clearing away the farmyard and planting trees. But in these cases, we're talking about ornamental landscaping. We know that some grand English lords had entire villages wiped out to improve the views from the windows of their mansions, to say nothing of the Highland clearances.

From a history page that is anti-enclosure, click on cartoon for more Next, Professor Easton looks at Mansfield Park. Mr. Rushworth plans to improve the landscaping at his estate. As well, Henry Crawford tells Edmund Bertram how he can fix up the parsonage at Thornton Lacey to look like a gentleman's house by clearing away the farmyard and planting trees. But in these cases, we're talking about ornamental landscaping. We know that some grand English lords had entire villages wiped out to improve the views from the windows of their mansions, to say nothing of the Highland clearances.However, I don't think there is any indication that Mr. Rushworth is planning to enclose more farmland; he intends to re-design his existing parkland. Henry Crawford's concerns about Thornton Lacey are strictly aesthetic as well. The farmyard Crawford wants to clear away appears to belong to the parsonage. It doesn't look like any villagers will be affected, which is the question at issue here.

Austen shows affection for Mr. Knightley's old-fashioned home with its unimproved landscaping: "the Abbey, with all the old neglect of prospect, had scarcely a sight—and its abundance of timber in rows and avenues, which neither fashion nor extravagance had rooted up." In fact, comparing Mr. Knightley's home to General Tilney's pride in his modernized Northanger Abbey, we see that Austen is gently mocking about this new-fangled landscaping movement. Both John Dashwood and General Tilney have greenhouses -- and they are both bad guys in Austen. Dashwood and Rushworth have cut down or intend to cut down the old trees which line their avenues. The focus here is on showy landscaping, not enclosure.

(Interesting side note, some of those expansive Capability Brown-landscaped meadows were more than ornamental, they were profitable because sheep could safely graze serenely on them, and the landowner could make money selling wool and mutton. This is the part where people who know what a "ha-ha" is can nod knowingly. Ah yes, the ha-ha.)

Many of Austen's characters enjoy walking outside and enjoying nature -- Fanny Price in particular -- so there is nothing reprehensible about enjoying a beautiful landscape. Perhaps it is all a question of moderation. As Fanny says of Mrs. Grant's shrubbery: "There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! Not too much attempted!”

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot joins in a very long ramble across fields divided by fences and hedges. Anne enjoys the melancholy beauty of autumn, and meditates on how the farmer and his plow attest to the promise of spring, but is there even a hint that the enclosed land she's walking through, the hedgerow she's resting beside, are symbols of the cruel disenfranchisement of the peasants?

And what about Emma, the book that is Exhibit "A" in Dr. Helena Kelly's contention that Austen was anti-enclosure? In the JASNA article, Dr. Easton points out that Emma Woodhouse pays a charitable visit to a poor family, a family that could well have been affected by the loss of common grazing rights, but Easton does not single out any passages in Emma that refer to land enclosure. She evidently does not see the "politicized references" that Dr. Helena Kelly sees.

Old-fashioned tithes A very informative BBC podcast about land enclosure explains that enclosure was beneficial for the clergymen of the Church of England -- like Austen's father. Instead of collecting chickens and bushels of wheat from their parishioners as tithe payments, they were assigned their own land, or received a combination of land and money.

Old-fashioned tithes A very informative BBC podcast about land enclosure explains that enclosure was beneficial for the clergymen of the Church of England -- like Austen's father. Instead of collecting chickens and bushels of wheat from their parishioners as tithe payments, they were assigned their own land, or received a combination of land and money.Simon J. White writes in Romanticism and the Rural Community : “There is little evidence within [Austen's] novels that Jane Austen was radically opposed to enclosure in particular or agrarian reform in general. Indeed, as Robert Clark and Gerry Dutton have found, Austen’s father was ‘as engaged in capitalist agricultural activity as any farmer would be today’."

In Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney has his own "young plantations" (that is, areas that are newly planted or forested) and he concentrates on improving their value as he looks forward to his marriage. Edmund Bertram and Edward Ferrars are also shown as being interested in getting as much value as they can out of the lands (called "glebe lands") they control in the parish. Edmund is learning from Dr. Grant "how to turn a good income into a better" and Edward and Elinor would like "rather better pasturage for their cows." As well, they are intent on making their little parsonage look grander by adding shrubberies and a big curved driveway (a sweep). Professor Easton points out "The fact that clergymen have a particular interest in land enclosure is evident in Jane Austen’s fiction..."

"Very true,” said Harriet. “Poor creatures! one can think of nothing else.” To recap, although we agree that John Dashwood is a jerk, Austen never writes about any displaced peasants who have lost their rights to use common land. As we have seen, she is not sympathetic to gypsies.

"Very true,” said Harriet. “Poor creatures! one can think of nothing else.” To recap, although we agree that John Dashwood is a jerk, Austen never writes about any displaced peasants who have lost their rights to use common land. As we have seen, she is not sympathetic to gypsies. Emma talks to Harriet of what the poor must suffer in winter. But she doesn't add, "If only that vile Mr. Knightley hadn't forbidden them from gathering firewood from the forest!" Dr. Kelly sees subtle criticism; I think the subtleties she sees are in fact non-existent, particularly in Emma.

Which brings us to the final question -- would it have been risky for Austen to protest against land enclosure? Well, that would depend on how far she had gone in her opposition, or what she had proposed as a solution.

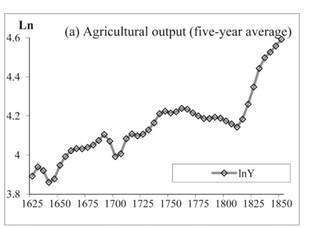

More generally, if you were for land enclosure, you were on the side of the toffs, although land enclosure ended up benefitting everyone in time, as we can see from the chart below which shows the dramatic rise in agricultural output resulting from the agricultural and industrial revolutions.

Ang, James B., et al. “Innovation and Productivity Advances in British Agriculture: 1620–1850.” Southern Economic Journal, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013, pp. 162–186. JSTOR If you were against land enclosure like Thomas Paine, you were on the side of the labouring classes. He proposed a land tax as a sort of reparations for landless people. Paine had already left England to escape persecution for his earlier writings when he published his pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, in 1797. The pamphlet was re-printed in England in 1817 and I can't find any indication that anyone was arrested over it.

Ang, James B., et al. “Innovation and Productivity Advances in British Agriculture: 1620–1850.” Southern Economic Journal, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013, pp. 162–186. JSTOR If you were against land enclosure like Thomas Paine, you were on the side of the labouring classes. He proposed a land tax as a sort of reparations for landless people. Paine had already left England to escape persecution for his earlier writings when he published his pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, in 1797. The pamphlet was re-printed in England in 1817 and I can't find any indication that anyone was arrested over it. Another radical writer, Thomas Spence, thought all land should be kept in common. But he also wanted an end to the aristocracy. He went to prison. William Cobbett, a writer and MP, opposed land enclosure. He went to prison for seditious libel, but over other issues, not land enclosure.

Oliver Goldsmith's 1770 poem, The Deserted Village, mentions a proud nobleman who grabs land to create an artificial lake and extend his parkland, but Goldsmith wasn't locked up for writing it and the poem was popular and frequently reprinted. Goldsmith's poem is a nostalgic lament for a vanished rural village, a way of life that was gone forever. It was not so political as to get Goldsmith into trouble.

If Austen didn't speak out against enclosure publicly, what about privately? After studying Austen's few surviving letters, Professor Easton concludes: "[Austen] clearly welcomed whatever profits her family could gain from the land they owned or leased, although she was not beyond teasing Edward Knight when he hoped to acquire a dead neighbor’s farm."

If Austen didn't speak out against enclosure publicly, what about privately? After studying Austen's few surviving letters, Professor Easton concludes: "[Austen] clearly welcomed whatever profits her family could gain from the land they owned or leased, although she was not beyond teasing Edward Knight when he hoped to acquire a dead neighbor’s farm."According to Professor Easton, "Jane Austen never explicitly condemned the enclosure movement in either her fiction or her letters."

So.... what is the conclusion? Was Austen an anti-enclosure radical? Given the slight evidence of her private letters, I don't think she felt that strongly about the issue.

Dr. Kelly's theory of Jane Austen's secret radicalism comes down to the assertion that Austen was a radical but she couldn't show it. We can never know if Austen wasn't explicit for fear of the consequences. Kelly's theory, as I've mentioned before, is non-falsifiable.

However, since Austen's references to land enclosure are so fleeting and indirect, her novels aren't the first place you'd turn to if you want to read fictionalized accounts of how land enclosure affected the working class. An old favourite of mine is The Camerons by Robert Crichton (1972), which features the Highland Clearances.

And I also recommend a new novel by Elizabeth Grant, An Independent Heart. This beautifully-written story includes a debate over land enclosure and is set during the Regency period. "It is February 1814. Claire Lammond is in London on a family visit. The British army has crossed the Nivelle. Justin Sumners is recalled to England. They meet on the ice of the frozen Thames: two strong, engaging characters whose relationship unfolds against a richly evocative historical background... At its core are family ties: between husband and wife, son and father, children and parents, siblings and cousins, all tested and strained by the demands of politics, love, and duty."

And I also recommend a new novel by Elizabeth Grant, An Independent Heart. This beautifully-written story includes a debate over land enclosure and is set during the Regency period. "It is February 1814. Claire Lammond is in London on a family visit. The British army has crossed the Nivelle. Justin Sumners is recalled to England. They meet on the ice of the frozen Thames: two strong, engaging characters whose relationship unfolds against a richly evocative historical background... At its core are family ties: between husband and wife, son and father, children and parents, siblings and cousins, all tested and strained by the demands of politics, love, and duty." If I come across any other writings of Austen's time which protests against land enclosure, I'll share that information here. Next post:

Published on January 18, 2021 00:00

January 11, 2021

CMP#23 Is Mr. Knightley a villain?

Some Jane Austen fans want to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. In last week's post, I looked at the suggestion that the gypsies in Emma were a veiled reference to the consequences of land enclosure. Is Mr. Knightley a villain? Emma and land enclosure

Some Jane Austen fans want to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. In last week's post, I looked at the suggestion that the gypsies in Emma were a veiled reference to the consequences of land enclosure. Is Mr. Knightley a villain? Emma and land enclosure

"How I love... your father's estate." Some modern readers of Emma don't care very much for its leading man. "[W]hat's so great about a mansplainer grooming the bride that (as he admits at one point) he's loved since she was thirteen?"

"How I love... your father's estate." Some modern readers of Emma don't care very much for its leading man. "[W]hat's so great about a mansplainer grooming the bride that (as he admits at one point) he's loved since she was thirteen?" I don't object in the least if you don't like Mr. Knightley. To each his own. It's also understandable if you can't enjoy Emma because of its preoccupation with social class. If, after watching the 2020 movie version of Emma, you conclude that it's a story about selfish people who treat their servants like machines, I take your point. But, it's quite another thing to insist that Jane Austen intended for us to dislike Mr. Knightley.

George Knightley, the owner of Donwell Abbey, makes his money from his own farmland and from the rents of his tenants. Therefore Dr. Kelly, author of Jane Austen: The Secret Radical, wants to convince us that the leading man in a romantic comedy of manners is actually the villain of a tragedy about land enclosure.

The enclosure movement involved a changeover from open farmland held and worked in common, to a system where fields and forests once used by everybody were fenced off so that poor people could not graze their cows, or gather berries, nuts, or firewood.

And how do we know that Knightley is a villain? Dr. Kelly says Emma is "crammed with references to agricultural improvement, parish boundaries, and hedges; loaded, inevitably politicized references, information that there’s absolutely no other reason to include.”

No reason, that is, unless you are writing a book set in a little English country village where the main male character is the leading landowner and farmer in the area? And what is "politicized," for example, about the the following:

[When John Knightley, a lawyer from London, is visiting with his older brother George] "The brothers talked of their own concerns and pursuits… As a magistrate, [George Knightley] had generally some point of law to consult John about, or, at least, some curious anecdote to give; and as a farmer, as keeping in hand the home-farm at Donwell, he had to tell what every field was to bear next year, and to give all such local information as could not fail of being interesting to a brother... The plan of a drain, the change of a fence, the felling of a tree,.. was entered into with as much equality of interest by John, as his cooler manners rendered possible…” The Agricultural Revolution vastly increased the amount of food produced in the UK That, by the way, is the only reference to a fence in the entire novel. The word “hedge” appears four times, and one of those hedges is the ‘low hedge’ of a miserable cottager, marking the boundary of her own little garden. The word “cards” appears five times in Emma. Mrs. Goddard is invited to the Woodhouses to “win or lose a few sixpences by his fireside.” Why not claim Emma is a novel about the scourge of gambling? There is much ado about Mr. Woodhouse and his fussiness over food. Jane Fairfax turns down Emma's gift of arrowroot. "It was a thing she could not take." Why not say Emma is a novel about eating disorders? There is more attention given to Emma’s shoelace than to parish borders. More attention given to pianofortes, haircuts, shawls, balls and slices of cake. But perhaps this only proves how very heartless and indifferent Mr. Knightley and the others are to the plight of the poor people all around them.

And, the word "enclosure" is not mentioned at all in Emma! As opposed to Sense & Sensibility, where enclosure is mentioned twice. A scholarly article about "Jane Austen and the Enclosure Movement" in the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America discusses references to enclosure in Sense & Sensibility and Northanger Abbey, but doesn't mention the hedges of Emma.

According to Dr. Kelly, we aren't supposed to believe Mr. Knightley when he tells Emma that he loves her. He's marrying her for her land, whatever acreage the Hartfield estate sits on, so he can enclose it and make the poor villagers in the area still poorer. Further, he's a bad landlord who doesn't care about the welfare of his tenants because he "abandons" Donwell Abbey (as though he could not go there during the day--it's within walking distance), to move in with the Woodhouses.

Bill Nighy as Mr. Woodhouse in the 2020 Emma movie Dr. Kelly acknowledges that Mr. Knightley does not make a big deal about his wealth. He doesn't use his carriage very much, he wears thick gaiters because he is always tromping about in his fields. But nevertheless, he is avaricious. Dr. Kelly thinks the following passage is another hint about Knightley’s land enclosure schemes:

Bill Nighy as Mr. Woodhouse in the 2020 Emma movie Dr. Kelly acknowledges that Mr. Knightley does not make a big deal about his wealth. He doesn't use his carriage very much, he wears thick gaiters because he is always tromping about in his fields. But nevertheless, he is avaricious. Dr. Kelly thinks the following passage is another hint about Knightley’s land enclosure schemes:“True, true,” cried Mr. Knightley, with most ready interposition—“very true. That's a consideration indeed.—But John, as to what I was telling you of my idea of moving the path to Langham, of turning it more to the right that it may not cut through the home meadows, I cannot conceive any difficulty. I should not attempt it, if it were to be the means of inconvenience to the Highbury people, but if you call to mind exactly the present line of the path.... The only way of proving it, however, will be to turn to our maps. I shall see you at the Abbey to-morrow morning I hope, and then we will look them over, and you shall give me your opinion.”

The footpath is probably a right-of-way, a shortcut which has been used by local people since time out of mind. However, the meadows are being used for grazing animals or growing hay or something, and it would be both safer for the people and more efficient for the farm to move the path. Mr. Knightley would have to hire local labourers to create a new clearly-marked path that skirts the meadows.

In his annotated Mansfield Park, David M. Shapard points to this same passage as an example of Mr. Knightley’s thoughtfulness to the local people, thoughtfulness which sets him apart from other landowners of his class. He will not move the path until he can demonstrate that it won’t inconvenience anyone.

Is there a secret message here? Not necessarily. Austen uses the footpath for comic reasons. It's part of a running joke in Chapter 12, where Emma and Knightley work together to distract John Knightley whenever he starts getting snappish with Mr. Woodhouse, by constantly changing the subject. And certainly Mr. Knightley emphasizes that he wouldn't do it if he believed it would be inconvenient for the Highbury people.

The Poultry Thief by Louis Theodore Devilly Emma ends with not one but three happy couples, but according to Dr. Kelly, it "ends on a particularly ominous note." This is because the event which makes it possible for Emma to set her wedding day to (the heartless, hypocritical) Mr. Knightley is the theft of poultry from Mrs. Weston. The theft frightens her father and so he welcomes the idea of Mr. Knightley moving to Hartfield to superintend and protect the household. As Dr. Kelly puts it: "Readers already have reason to mistrust the purity of Mr. Knightley’s motives in wanting to marry Emma. That the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man’s terror doesn’t do anything to dispel that lingering sense of unease."

The Poultry Thief by Louis Theodore Devilly Emma ends with not one but three happy couples, but according to Dr. Kelly, it "ends on a particularly ominous note." This is because the event which makes it possible for Emma to set her wedding day to (the heartless, hypocritical) Mr. Knightley is the theft of poultry from Mrs. Weston. The theft frightens her father and so he welcomes the idea of Mr. Knightley moving to Hartfield to superintend and protect the household. As Dr. Kelly puts it: "Readers already have reason to mistrust the purity of Mr. Knightley’s motives in wanting to marry Emma. That the marriage itself is made possible only by criminal acts and an elderly man’s terror doesn’t do anything to dispel that lingering sense of unease."Kelly reckons this theft must have been carried out by a hungry local villager, because the gypsies are gone by this point in the novel. (On the other hand, it might have been a professional gang of roaming poachers, who caught black-market game for London’s dining tables. Maybe they also stole domesticated fowl. “Other poultry-yards in the neighborhood also suffered,” Austen writes. This sounds like a criminal gang working methodically. If a poor villager suddenly had a yard full of turkeys and a full stew pot, the neighbours would have noticed.) Or, p erhaps the turkey thieves were desperate. Perhaps enclosure is happening in Highbury during the period of the novel; it probably is or already has. We can speculate all we want about who purloined the poultry. Were we supposed to feel the theft was "ominous," when the only person who was frightened was Mr. Woodhouse, and (in case the reader was not yet aware) Mr. Woodhouse is an extremely neurotic man?

Or are we supposed to laugh at Austen's ironic twist -- in the end, Mr. Woodhouse's habits of selfish nervousness actually made the marriage possible? The fact is that in terms of her plot, Austen had written herself into a corner. Emma's best trait is her patience and love for her father. Her feelings of duty made it impossible for her to leave his roof: "With respect to her father, it was a question soon answered... a very short parley with her own heart produced the most solemn resolution of never quitting her father — She even wept over the idea of it, as a sin of thought. While he lived, it must be only an engagement."

Austen had to resolve this issue before writing her happy ending, and she did. We should look first at the narrative structure and logic of the novel before delving around for hidden meanings.

"Badly done, Emma!" The most significant thing about Mr. Knightley is not that he wants to move a footpath that is cutting across his meadows, it is not that he throws a “Marie Antoinette"-style strawberry picnic for his privileged social circle, it’s that he is the moral arbiter of Emma.

"Badly done, Emma!" The most significant thing about Mr. Knightley is not that he wants to move a footpath that is cutting across his meadows, it is not that he throws a “Marie Antoinette"-style strawberry picnic for his privileged social circle, it’s that he is the moral arbiter of Emma. Throughout the novel, Mr. Knightley is making judgements. Emma thinks Robert Martin is unworthy of Harriet. Mr. Knightley disagrees. Emma is wrong and Mr. Knightley is right. He's worried about the consequences of Harriet's friendship with Emma. His premonitions are correct. He has a clearer understanding of Mr. Elton's character than Emma. He’s suspicious of Frank Churchill. He's right to be. He realizes Jane Fairfax is hiding a secret. He scolds Emma for making fun of Miss Bates in front of everyone at the Box Hill picnic. Everything Mr. Knightley says about Emma’s faults is correct, and she comes to realize this. His approval means everything to her. If he is a villain, then what is she?

As Professor John Mullan pointed out, there's a problem with insisting that Knightley is not a hero, but actually a villain. Dr. Kelly is ignoring the narrative logic of the story. Where is the payoff for the reader in a story about a man who worries about the heroine, who does kind and thoughtful things for Miss Bates and her mother, who steps up and dances with a humiliated young woman at a public ball, who protects his housekeeper from the interference of Mrs. Elton, who speaks of a yeoman farmer with praise -- but marries Emma just so he can get his hands on her father’s lands?

To make Mr. Knightley into the villain of the tale is to turn it upside down; in fact, to remove any inducement for reading such a strangely constructed book. I am not denying that land enclosure created significant problems for poor people in England through the 18th century, I am just saying that Emma is not about land enclosure and Knightley is not intended to be a villain.

Dr. Kelly also claims that Austen merely hints at radical themes because of the restrictive times in which she lived, when criticizing the authorities could get you in trouble, even sent to prison. That's why we have to read Austen carefully, to divine the hints given within, which Kelly believes Austen's contemporary readers would have understood.

If Austen had been opposed to land enclosure, was it dangerous for her to say so? Next post: How did Austen feel about land enclosure? The poultry thief in the painting appears to be a soldier. One can picture poor soldiers in the militia, stationed about England, unable to resist the temptation to steal food to supplement their rations. And disabled soldiers and sailors who returned from fighting Napoleon were often reduced to begging. In my Mansfield Trilogy, Fanny Price's brother Sam becomes radicalized when he returns to England after the war is over. Click here for more information about my novels

Published on January 11, 2021 00:00

January 4, 2021

CMP#22 Is Emma about land enclosure?

Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Is Emma about land enclosure? “I have the greatest pleasure, my dear Emma, in forwarding to you the enclosed.”

Some modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Is Emma about land enclosure? “I have the greatest pleasure, my dear Emma, in forwarding to you the enclosed.”This is the only time the word “enclosed” appears in Emma, in reference to a letter from Frank Churchill. The word “enclosure” and its alternate spelling “inclosure” do not appear at all.

The enclosure movement was a part of Great Britain's agricultural revolution. Throughout the 18th century and into the 19th, village land which had been held "in common" and which the villagers used for farming, grazing their livestock or foraging for nuts and berries, began to be fenced off by the local gentry. The enclosed fields yielded more crops per acre, as we will see, but it did make life more difficult for the villagers. They could no longer keep a cow for milk for their children, for example, because they had no grazing land. Enclosure was a driving force behind the great migration to the cities at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

Dr. Helena Kelly gives an interesting and informative explanation of land enclosure and agriculture in rural 18th century Britain in Jane Austen: the Secret Radical. But is she correct that Emma, Jane Austen’s fourth novel, is a condemnation of land enclosure?

Short answer: I don't think so.

Long answer: I don't think so, but first, we'll have a digression about gypsies. In Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, Dr. Kelly intersperses her critical analysis of Austen novels with brief fictional sketches of Austen. In one, Austen is walking down a country lane and passes a gypsy girl picking wild strawberries by the side of the road. “The bright dark gaze that turns on her is astonishingly like her own.” Austen bids her “good day,” and walks on. This fictional vignette, however, does not shed light one way or another on Austen’s work or her true attitudes.

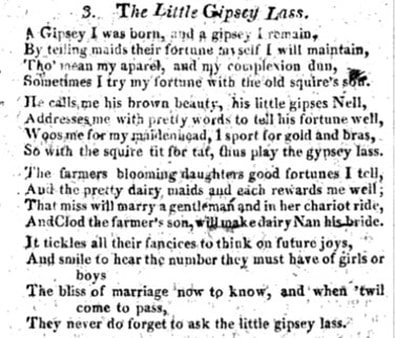

from an 1802 songbook

from an 1802 songbook  In a previous post about Austen’s beliefs around charity to the poor, I pointed out how unsympathetic Austen is to the gypsies who surround Harriet when she is out on a walk, frightening her with their demands for money.

In a previous post about Austen’s beliefs around charity to the poor, I pointed out how unsympathetic Austen is to the gypsies who surround Harriet when she is out on a walk, frightening her with their demands for money.The gypsies are possibly worse off than usual because of enclosure. Some of the fields where the gypsies once camped as they roamed about the countryside would have been prohibited to them. That is why, Kelly suggests, the gypsies “are not at their usual campsite” (wherever that might have been), they are “camped on the side of the road.”

All of this may be the case—the gypsies might be "desperate," they might be precariously camping on a narrow verge between the road and a “slight hedge” over which Harriet’s walking companion escapes. That hedge might have been “slight” because it was newly planted in some new enclosure scheme which cuts poor people off from gathering firewood and scavenging for food, though Austen doesn't say so. The fact remains that Austen is not sympathetic to the gypsies, not in the slightest.

All of this may be the case—the gypsies might be "desperate," they might be precariously camping on a narrow verge between the road and a “slight hedge” over which Harriet’s walking companion escapes. That hedge might have been “slight” because it was newly planted in some new enclosure scheme which cuts poor people off from gathering firewood and scavenging for food, though Austen doesn't say so. The fact remains that Austen is not sympathetic to the gypsies, not in the slightest. Austen wrote: "The terror which the woman and boy had been creating in Harriet was then their own portion. He had left them completely frightened..." They leave Highbury quickly to escape “the operations of justice.” Harriet ends up being the heroine of “Harriet and the Gypsies,” a bedtime story for Emma’s little nephews, and Frank Churchill is the hero who rescued her.

From an 1820 songbook for "gentlemen" So Jane Austen, the secret radical, doesn’t care about poor raggedy little gypsy children. She doesn't portray the Romani as a vibrant people pursuing a time-honoured way of life with their own rich folkloric customs, music, and dress. Instead, they are parasites who beg and steal. How can this episode be portrayed as a criticism of land enclosure?

From an 1820 songbook for "gentlemen" So Jane Austen, the secret radical, doesn’t care about poor raggedy little gypsy children. She doesn't portray the Romani as a vibrant people pursuing a time-honoured way of life with their own rich folkloric customs, music, and dress. Instead, they are parasites who beg and steal. How can this episode be portrayed as a criticism of land enclosure? The best that Dr. Kelly can do with this contradiction to her thesis is to argue that Austen isn’t as derogatory of gypsies as other writers of the period such as Cowper and Wordsworth. Austen presents the gypsies in a “relatively positive” light, as compared to calling them “vermin,” as the popular periodical The Spectator did.

Gypsies appear in various guises in the literature of Austen's time, portrayed as thieves, carefree vagabonds, and as con artists, As well, there is a lot of attention given to gypsy women, who are exotic and possibly sexually available.

In the ballad "A Poor Little Gipsey," (excerpted above) the girl asks men not to "harm," ie to not seduce or rape her, while "The Little Gipsey Lass" portrays the gypsy girl as bargaining with men for her "maidenhead."

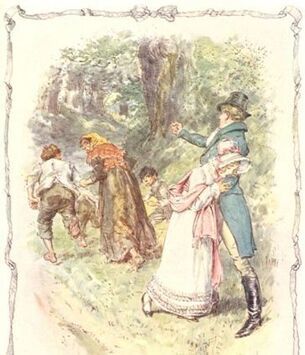

In "The Gipsey Girl," an 1805 poem, "Henry wanders in despair" because he has a hopeless love for a gypsy. Hopeless, of course, because of the ethnic and class divide between them. But plenty of Austen's contemporaries treated gypsies with sympathy, and there is no reason Austen could not have done likewise if she'd been inclined to do so. In the following excerpt from a poem by the clergyman-poet George Crabbe, The Hall of Justice, a gypsy woman, charged with stealing food to feed her starving child, begs to tells her story:

"Young Gypsy Under Arrest" by Berthold Woltze .... In this, th' adopted babe I hold

"Young Gypsy Under Arrest" by Berthold Woltze .... In this, th' adopted babe I holdWith anxious fondness to my breast,

My heart's sole comfort I behold,

More dear than life, when life was blest;

I saw her pining, fainting, cold,

I begg'd--but vain was my request....

.... Taught to believe the world a place

Where every stranger was a Foe

Trained in the arts that mark our race

To what new people could I go?...

Though poor, and abject, and despised,

Their fortunes to the crowd I told;

I gave the young the love they prized,

And promised wealth to bless the old. Henry Hunt, a real, genuine, dyed-in-the-wool radical, was more sympathetic than Austen or Cowper or Wordsworth. In his 1820 memoirs, he mentions that his mother went to help "a poor gypsy woman, who that morning had been delivered of a fine child, under an adjoining hedge, without any other covering but one of their small tents..." Dr. Kelly, arguing that Austen uses the gypsies to point to the issue of land enclosure, argues that they “are not even necessary to move the plot along in Emma; [Austen] could have easily come up with an alternative. They’re in the novel for a purpose.”

Yes, and that purpose is to create an important misunderstanding between Emma and Harriet. Emma thinks that Harriet falls in love with Frank Churchill after he rescues her from the gypsies.

Austen uses gypsies for their exotic qualities; they heighten Frank's rescue of Harriet into a romantic, unusual episode. Reflecting on the incident later, Emma thinks: "Such an adventure as this,—a fine young man and a lovely young woman thrown together in such a way, could hardly fail of suggesting certain ideas to the coldest heart and the steadiest brain... It was a very extraordinary thing! Nothing of the sort had ever occurred before to any young ladies in the place, within her memory; no rencontre, no alarm of the kind;—and now it had happened to the very person, and at the very hour, when the other very person was chancing to pass by to rescue her!"

So if Emma is about land enclosure, who is the horrible person who wants to enclose the fields around Highbury to line his own pockets? Who is behind the drive to starve the gypsies and subdue the peasants? Next post: Is Mr. Knightley a villain?

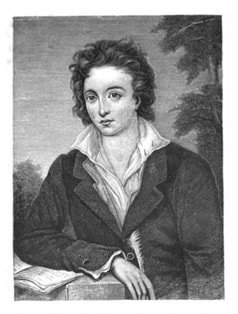

In my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Crawford from Mansfield Park have an argument about land enclosure. Click here for more about my Mansfield Trilogy and here for more about Shelley and the Unknown Lady.

In my novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Crawford from Mansfield Park have an argument about land enclosure. Click here for more about my Mansfield Trilogy and here for more about Shelley and the Unknown Lady.

Published on January 04, 2021 00:00

December 30, 2020

CMP#21 Primogeniture in Sense & Sensibility

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Radical Jane Austen: Primogeniture, part 2

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Radical Jane Austen: Primogeniture, part 2

Esau sells his birthright to his younger brother for a "mess of pottage" Genesis 25 In part one of this discussion of primogeniture, we looked at how the practice of excluding the younger brothers (and all the sisters) from inheriting the family estate became caught up in a debate around revolutionary change. Some public intellectuals, including Mary Wollstonecraft, wanted to follow the French example and abolish primogeniture, but once the French Revolution turned into the Reign of Terror, a strong backlash arose in England.

Esau sells his birthright to his younger brother for a "mess of pottage" Genesis 25 In part one of this discussion of primogeniture, we looked at how the practice of excluding the younger brothers (and all the sisters) from inheriting the family estate became caught up in a debate around revolutionary change. Some public intellectuals, including Mary Wollstonecraft, wanted to follow the French example and abolish primogeniture, but once the French Revolution turned into the Reign of Terror, a strong backlash arose in England. In Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, Dr. Helena Kelly argues that Sense & Sensibility is a covert attack on primogeniture. Dr. Kelly writes: “[Austen] wasn’t alone in questioning the fundamental fairness of primogeniture. The feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft did it too, in her 1792 book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” The phrasing of this sentence might mislead Kelly’s readers into thinking that the only two people in Georgian England who wrote about primogeniture were Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen. That’s obviously not the case.

Many people wrote about primogeniture and inheritance was an anxious topic of discussion among families, especially daughters and younger sons.

Historian Rory Muir has written that there was more open resentment of primogeniture in Tudor and Stuart times, than in Regency times. He suggests it is because there were more opportunities for second sons in Austen's time. Because of war, exploration and colonization, the younger son could join the army or navy or the East India company. Of course this ended up being fatal to many of them.

We don't know if Jane Austen's father had the writings of conservative Edmund Burke or radicals Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft in his library. Regardless, he was an intelligent and well-educated man; he would have been fully aware of the main arguments on each side and I think his daughter would have been exposed to them.

Fundamentally though, Austen didn’t need anyone to explain the downside of primogeniture to her. It affected her family as well. She was upset when her father turned the Rectory in Steventon over to James, the oldest son. Of course, a post as a clergyman cannot be divided among all your children; but Mr. Austen also sold off many of the family possessions, including Jane's pianoforte. Family lore states that Jane fainted when she learned she had to leave her home and turn it over to her brother and sister-in-law. Later, she complained, “The whole World is in a conspiracy to enrich one part of our family at the expence of another.”

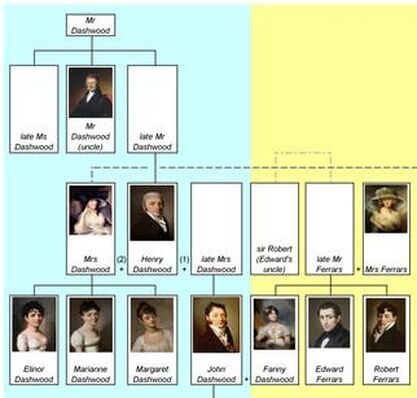

Now that the political and personal context surrounding primogeniture is understood, let’s look at what Austen says and doesn’t say about primogeniture in her novels. Did she, in fact, question the fundamental fairness of primogeniture? The Dashwood sisters in Sense & Sensibility, the children of a second marriage, are left with a small inheritance when their father dies a year after inheriting the estate (known as Norland) from his uncle. Norland goes to the son of his first marriage, John Dashwood.

John Dashwood’s wife Fanny talks him into ignoring his father’s dying injunction to be generous to his step-mother and his half-sisters, and the disinherited widow and daughters are forced to leave Norland (but not before Elinor falls in love with Fanny’s brother Edward).

Dashwood Family Tree, Wikimedia. John Dashwood inherits through his father, who inherits through his uncle.

Dashwood Family Tree, Wikimedia. John Dashwood inherits through his father, who inherits through his uncle.

Fanny Dashwood is a strong influence on her husband John. All of this takes up the first five chapters of the book, with a great deal of detail about the family tree and who inherits what.

Fanny Dashwood is a strong influence on her husband John. All of this takes up the first five chapters of the book, with a great deal of detail about the family tree and who inherits what. Can we truly say Austen is arguing against primogeniture? She describes the situation, but her moralizing is not directed at the law, it is directed at the decisions of the Dashwood family.

First, she faults the old uncle for tying up the estate to pass it down entirely to John Dashwood and to John Dashwood's little boy, "who, in occasional visits with his father and mother at Norland, had so far gained on the affections of his uncle... as to outweigh all the value of all the attention which, for years, he had received from his niece and her daughters."

Then she faults John and Fanny Dashwood for being insensitive and selfish. Mrs. Dashwood does not "dispute" the right of her daughter-in-law Fanny to move in immediately after her husband's funeral: "the house was her husband's from the moment of his father's decease; but the indelicacy of [Fanny's] conduct... was to her a source of immovable disgust."

Then Fanny talks John out of giving his half-sisters a generous settlement. Austen shows us a man who fails to do his moral duty, and she gives us examples of his weak and avaricious nature throughout the book. Nor does she exempt Elinor and Marianne's father, or their mother, “a woman who never saved in her life,” from criticism for failure to prepare for the inevitable. The primogeniture is inevitable, the selfishness and mismanagement are not.

History Today: Younger sons needed a profession As usual, a topic which Dr. Kelly claims is featured in one novel is present in the other novels as well.

History Today: Younger sons needed a profession As usual, a topic which Dr. Kelly claims is featured in one novel is present in the other novels as well. Primogeniture and entail, as scholar Zouheir Jamoussi notes, come up in every one of Austen’s novels—and many, many other novels and plays as well. It's not as if Austen’s readers would have been forcibly struck by her description of a situation they’d never encountered before.

The issue is made more explicit in Pride & Prejudice than in Sense & Sensibility. It is Mrs. Bennet who argues most often, and most loudly, against the fact that her daughters are left out of the inheritance.

Austen's brother Edward Austen became Edward Austen-Knight. There is no evidence that Austen thought the entire institution of primogeniture had to go. She explicitly said "No one could dispute [Fanny Dashwood's] right to come" to Norland before her father-in-law was cold in his grave. Nor does she hint at any alternative to primogeniture. Mrs. Ferrars, the matriarch of the Ferrars family, does have it in her power to divide a large inheritance between her sons. Austen doesn't portray a mother who treats her sons equally--although she could have used her novel to show us how things ought to be. Instead, she portrayed a narrow-minded, vindictive woman who punishes her oldest son by giving the money to his younger brother. As Mrs. Jennings remarks, "Everybody has a way of their own. But I don’t think mine would be, to make one son independent, because another had plagued me.”

Austen's brother Edward Austen became Edward Austen-Knight. There is no evidence that Austen thought the entire institution of primogeniture had to go. She explicitly said "No one could dispute [Fanny Dashwood's] right to come" to Norland before her father-in-law was cold in his grave. Nor does she hint at any alternative to primogeniture. Mrs. Ferrars, the matriarch of the Ferrars family, does have it in her power to divide a large inheritance between her sons. Austen doesn't portray a mother who treats her sons equally--although she could have used her novel to show us how things ought to be. Instead, she portrayed a narrow-minded, vindictive woman who punishes her oldest son by giving the money to his younger brother. As Mrs. Jennings remarks, "Everybody has a way of their own. But I don’t think mine would be, to make one son independent, because another had plagued me.” As this next passage from Sense & Sensibility indicates, Austen seems to regard a more equitable world as pie-in-the-sky wishful thinking.

"I wish," said Margaret, striking out a novel thought, “that somebody would give us all a large fortune apiece!”

“Oh that they would!” cried Marianne, her eyes sparkling with animation, and her cheeks glowing with the delight of such imaginary happiness.

“We are all unanimous in that wish, I suppose,” said Elinor, “in spite of the insufficiency of wealth.”

There is a subtle but definite sarcasm in her editorial insertions: it is "a novel thought" to hope someone will give you a large sum of money. Young Margaret doesn't realize how many before her have had the same idea. But the prospect of receiving a large fortune is "imaginary" for most.

Oddly enough, the impossible did happen to Austen's brother Edward. He was adopted as the heir of some very wealthy relatives. Near the end of Austen's life, another rich uncle died, leaving his fortune to his wife, instead of spreading the wealth around in the family. Austen admitted that she was disappointed. That's still a far cry from advocating that the laws of inheritance be reformed.

Austen portrayed dysfunctional marriages--is she arguing that the institution of marriage should be abolished? Austen wrote about negligent parents—is she against the nuclear family? As reviewer Alexandra Mullen perceptively writes: “the aim of Austen’s satire is not to raze the world to ground zero but to amend, as much as humanly possible, the world we have inherited.” And for Austen, this relates more to private conduct than public institutions. Next post: Is Emma about land enclosure? In my novella Shelley and the Unknown Lady, Mary Crawford is surprised and pleased to learn that the poet she's met in Italy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, is the heir to a baronetcy. Click here for more.

Published on December 30, 2020 00:00

December 29, 2020

CMP#20 Primogeniture

Implicit Values in Austen: Primogeniture as the Status Quo "Well, if they can be easy with an estate that is not lawfully their own, so much the better. I should be ashamed of having one that was only entailed on me.”

Implicit Values in Austen: Primogeniture as the Status Quo "Well, if they can be easy with an estate that is not lawfully their own, so much the better. I should be ashamed of having one that was only entailed on me.”So exclaims Mrs. Bennet in Pride & Prejudice. A bleak future awaits the Bennet girls because Longbourn is entailed on the heirs male, and Mrs. Bennet frets about it frequently. Her two oldest daughters, however, appear to accept that this is just the way things are. Austen goes on to write:

"Jane and Elizabeth tried to explain to her the nature of an entail. They had often attempted to do it before, but it was a subject on which Mrs. Bennet was beyond the reach of reason, and she continued to rail bitterly against the cruelty of settling an estate away from a family of five daughters, in favour of a man [Mr. Collins] whom nobody cared anything about." The life-changing event of getting an inheritance was a common device in many novels and plays. In Northanger Abbey, Elinor Tilney is able to marry the man she loves after Austen ruthlessly dispatches her sweetheart's older brother. A missing heir shows up in the play, “The Heir at Law,” which is the play Tom Bertram wanted to perform at Mansfield Park. Sometimes the heiress is a girl, like Jane Eyre or Anne de Bourgh or Miss Grey with her fifty thousand pounds in Sense & Sensibility.

"Jane and Elizabeth tried to explain to her the nature of an entail. They had often attempted to do it before, but it was a subject on which Mrs. Bennet was beyond the reach of reason, and she continued to rail bitterly against the cruelty of settling an estate away from a family of five daughters, in favour of a man [Mr. Collins] whom nobody cared anything about." The life-changing event of getting an inheritance was a common device in many novels and plays. In Northanger Abbey, Elinor Tilney is able to marry the man she loves after Austen ruthlessly dispatches her sweetheart's older brother. A missing heir shows up in the play, “The Heir at Law,” which is the play Tom Bertram wanted to perform at Mansfield Park. Sometimes the heiress is a girl, like Jane Eyre or Anne de Bourgh or Miss Grey with her fifty thousand pounds in Sense & Sensibility. In this blog series, I've been discussing the values which I think are implicit in Jane Austen-- values such as pride in being English, pride in being an Englishwoman, a belief in the idea of human progress, the maintenance of class distinctions, and decorum in religion. Now I'll turn back to the themes identified in Jane Austen: the Secret Radical by Dr. Helena Kelly. I have previously discussed (and disagreed with) what she has to say about hidden themes in Austen's novels, except for Sense & Sensibility. So here we go.

Dr. Kelly asserts that Sense & Sensibility is a subversive attack on primogeniture, the practice of leaving the family estate to the oldest son, or closest male heir. (An "entail" was an additional restriction put on the estate which controlled who could inherit and what they could do with the property.) Certainly inheritance is the event that kicks off the plot of Sense & Sensibility, but is there a hidden message of protest as well?

Because in fact, advocating against primogeniture was radical in Austen's time.

Elinor (Emma Thompson) explains to her sister Margaret that houses pass from father to son There are obvious pros and cons around primogeniture. The economic argument is that it’s best to keep large estates intact and functioning. Just as you can’t chop a country up in pieces and give one to each prince every time the king dies, you can’t divide up an estate. That is, you could do it, but the downside is pretty apparent. Austen's favourite moral essayist Dr. Samuel Johnson defended primogeniture, arguing that it was good for the younger sons to have to earn their own way in life. Character-building stuff. As Johnson allegedly put it, primogeniture "makes but one fool in a family." The heir was too apt to turn out like Mansfield Park's Tom Bertram, "who feels born only for expense and enjoyment."

Elinor (Emma Thompson) explains to her sister Margaret that houses pass from father to son There are obvious pros and cons around primogeniture. The economic argument is that it’s best to keep large estates intact and functioning. Just as you can’t chop a country up in pieces and give one to each prince every time the king dies, you can’t divide up an estate. That is, you could do it, but the downside is pretty apparent. Austen's favourite moral essayist Dr. Samuel Johnson defended primogeniture, arguing that it was good for the younger sons to have to earn their own way in life. Character-building stuff. As Johnson allegedly put it, primogeniture "makes but one fool in a family." The heir was too apt to turn out like Mansfield Park's Tom Bertram, "who feels born only for expense and enjoyment." However, Adam Smith, a Scottish philosopher we call the father of modern economics, was opposed to primogeniture. Smith decided it encouraged “a certain class of people to live beyond their means and not contribute to progress through investment and improvement.”

Massacre at Nantes. That was the debate about primogeniture leading up to the time of the French Revolution. Then primogeniture became one of several issues which, bundled together, were at the centre of a fierce debate when Austen was a teenager.

Massacre at Nantes. That was the debate about primogeniture leading up to the time of the French Revolution. Then primogeniture became one of several issues which, bundled together, were at the centre of a fierce debate when Austen was a teenager.Revolutionary France put an end to monarchy, the aristocracy, and primogeniture. Some people in England thought that all sounded like a great idea. Then the revolutionaries in France really went to town and abolished the Catholic church, renamed days of the week and the days of the month, and reset the calendar to year zero. In between chopping off a lot of heads and drowning thousands of people in the river at Nantes.