Lona Manning's Blog, page 20

July 27, 2021

CMP#62 Shocking Compared to Whom?

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Click here for the first post in the series.

CMP#62

Shocking Compared to Whom?

You could not shock her more than she shocks me;

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Click here for the first post in the series.

CMP#62

Shocking Compared to Whom?

You could not shock her more than she shocks me;Beside her Joyce seems innocent as grass.

It makes me most uncomfortable to see

An English spinster of the middle-class

Describe the amorous effects of ‘brass’,

Reveal so frankly and with such sobriety

The economic basis of society.

-- from "letter to Lord Byron", by W.H. Auden

Many-tongued Rumour “[Jane] Austen is a novelist who tells you exactly how rich each of her characters is.”

Many-tongued Rumour “[Jane] Austen is a novelist who tells you exactly how rich each of her characters is.”So says an October 2020 New Yorker article, and who would dispute it? Mr. Darcy's entrance into the ballroom was followed by a "report which was in general circulation within five minutes... of his having ten thousand a year." Everyone seems to know how much money everybody else has: Mr. Collins knows Elizabeth is only entitled to one thousand pounds in the four percents after her mother’s death.

A poem by W.H. Auden, quoted above, surmises that Austen might be shocked to meet Lord Byron in heaven, but she is herself shocking because she's so frank and unsentimental about "the economic basis of society." However, as I’ve come to realize, the statement: “Jane Austen’s novels are preoccupied with money” is incomplete and somewhat misleading. The statement should be, “Jane Austen’s novels, like most novels of her time, were preoccupied with money.”

Many, many, novels of this period include exact descriptions of incomes, expectations, disappointments, and inheritances, especially as they relate to someone’s ability to get married. You can literally pick any18th-century novel at random and find passages referring to these things. And, just as in Sense & Sensibility , the financial circumstances of the main characters are often laid out in the introductory passages. Here is a sampling:

Reading the Will (detail), Otto Erdmann, 1886 In Jane West's A Gossip's Story (1796), people talk about Marianne, the heiress of fifty thousand pounds: "Rumour on this occasion acted in her usual way, increasing it to one hundred thousand pounds, for the many-tongued goddess always enlarges the possessions of the wealthy."

Reading the Will (detail), Otto Erdmann, 1886 In Jane West's A Gossip's Story (1796), people talk about Marianne, the heiress of fifty thousand pounds: "Rumour on this occasion acted in her usual way, increasing it to one hundred thousand pounds, for the many-tongued goddess always enlarges the possessions of the wealthy." Sarah Scotts’ 1766 novel Sir George Ellison opens with the situation and family tree of a man descended from “an ancient and opulent family,” who decided to give his son George "two thirds of the sum of £4,000 pounds of which he was possessed." More last-will-and-testament-type prose follows: the father “took a bond from his son, which secured to [his siblings] in case of their father’s death, their share of the 4000 pounds to be paid them in two years after his decease, if by that time of age, and obtained his promise, that during those two years, the money should bear six per cent interest, thus providing for their convenience as much as could be done without hurting their elder brother, whom possibly a more speedy payment might distress.”

In Charlotte Smith’s Celestina (1791), the author explains why the family estate is sadly encumbered. She goes back to before the time of Charles the First, down through the great-grandfather and grandfather of the last owner, “but the manners of the times in which he lived; and a disposition gay and volatile, had led the last possessor into expenses, which, if they did not oblige him to sell, had obliged him to mortgage great part of this, as well as all his other estates; and being charged at his death with twelve hundred a year to his widow, and the interest of ten thousand pounds given to his daughter, they slowly and with difficulty produced, under the management of very careful executors, little more than sufficient to pay such charges, and the interest of the money for which they were mortgaged...[and so on]”

In Elizabeth Helme’s Louisa, or, the Cottage in the Moor (1787), a widow named Mrs. Rivers narrates her backstory to Louisa. In introducing herself and her own circumstances, she goes back to her grandfather and, over several pages, explains his social standing, the source of the family income, the grandfather's lack of thrift, his purchase of an army commission for his son, the income her mother brought to the marriage, her parents' income and how they handled their money--and all of this to a total stranger who has stumbled upon her cottage! "My father was the only son of a gentleman of small fortune, who had a place in one of the public offices, which brought him about four hundred pounds a year. By living up to the full of what he possessed, he had it only in his power to procure a pair of colours for his son. [who advanced in the army, then returned home] “where, after remaining two years, he closed his only parent’s eyes (his mother expiring in giving him birth). [He went abroad and] married the daughter of an officer lately dead, who had two thousand pounds in the British funds.... (etc.)"

These novels reflected the reality of their times; birth and income were crucial matters in 18th century England. Your parentage determined whether you were of the gentility or the nobility, and your ability to live in the rank to which you had been born depended on your income, which could basically only come from land, inheritance, a fortune derived from the East or West Indies, or some genteel profession.

These novels reflected the reality of their times; birth and income were crucial matters in 18th century England. Your parentage determined whether you were of the gentility or the nobility, and your ability to live in the rank to which you had been born depended on your income, which could basically only come from land, inheritance, a fortune derived from the East or West Indies, or some genteel profession.In the New Yorker article referenced above, professor Louis Menand explains the "joke" behind Austen's remark that Augusta Hawkins brought “so many thousands as would always be called ten” to her marriage with Mr. Elton. "Austen’s nineteenth-century readers would have known... a fortune of ten thousand pounds represents the minimum point on the money curve.” Ten thousand pounds invested at five percent yields 500 pounds a year. In Alfred, or the Wilds of Strathnarven, a long-lost rich uncle in declares upon meeting his poverty-stricken niece that he would give her £10,000 on her wedding-day. In real life, the governor-general of Bengal, Warren Hastings, gifted £10,000 to his god-daughter Eliza, Jane Austen's cousin.

While 500 pounds a year wouldn't fund a lavish lifestyle, it would provide that cushion of safety that kept you in the genteel class. As Elinor and Marianne's conversation in Sense & Sensibility makes clear, you'd need more than £500 a year to live in style. Marianne named £2,000 a year as "a competence," the minimum amount of money you'd need to rise above sordid considerations about money. Otherwise, “money can only give happiness where there is nothing else to give it."

In fact, this "was a substantial sum," Shannon Chamberlain writes, "enough to place a family in what we would now call the one percent." When we understand how few people had £2,000 or more annually, we understand why Marianne is being so silly.

In Constance (1785), the heroine’s father has that desirable £2,000 a year, but he lives beyond his income; he dies, leaving his widow and daughter in debt. The author gives us the details: “Five thousand pounds in the funds had been left to [Constance’s mother] by a relation soon after her marriage, the interest of which her husband [had promised to] accumulate as a fortune for his daughter,” but dad invested it all in a canal scheme.

The widow moves in with her relatives, rents out the mansion, and hopes the canal will pay off one day. She's left with £300 a year and Constance gets £100.

To reiterate, this kind of specificity about money, which we are told is a feature of Austen's novels, is easily to be found in many novels.

If we are talking about Austen's literary merits, I think she is without question the best writer of her era, and one of the best writers of any era. But when you say "Austen talks about money," I think it's only fair to ask, compared to whom?

Nevertheless, many modern critics claim that Austen's references to money have a special significance. Next post. "Funnily enough," says John Mullan, "in our world, people are much more secretive about money than they were in Jane Austen's world, partly because of circumstances; marriage settlements made semi-public the amount money people were worth when they got married."

Genteel women had few opportunities to earn money and of course jobs like governess or school-teacher were poorly paid. Earning money was basically seen as degrading, not liberating. In the second book of my Mansfield series, A Marriage of Attachment, Fanny Price finds a job working for a charity that teaches fine sewing skills to poor girls on the outskirts of London. In A Different Kind of Woman, the third book in the series, we meet two other female characters who work; one in a bookstore and another as a piano teacher. Click here for more about my books.

Published on July 27, 2021 00:00

July 21, 2021

CMP#61 The Inscription on Austen's Grave

"But behold me Immortal:" Jane Austen in Winchester Cathedral Three days before her death, Jane Austen wrote

a witty poem

about St. Swithin, the patron saint of Winchester from which I take the quote: "But behold me immortal." Austen died on July 18, 1817 and was laid to rest on July 24.

"But behold me Immortal:" Jane Austen in Winchester Cathedral Three days before her death, Jane Austen wrote

a witty poem

about St. Swithin, the patron saint of Winchester from which I take the quote: "But behold me immortal." Austen died on July 18, 1817 and was laid to rest on July 24.

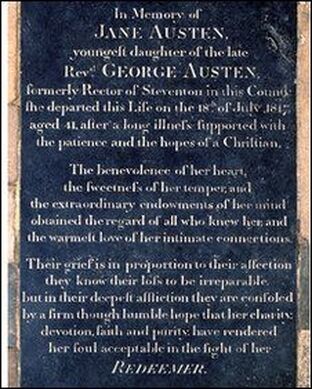

As we know, the fact of Austen's being a novelist is not mentioned on the stone slab that covers her grave and this has been the subject of much commentary, speculation, and even criticism.

As we know, the fact of Austen's being a novelist is not mentioned on the stone slab that covers her grave and this has been the subject of much commentary, speculation, and even criticism. The critic Margaret Kirkham says Austen's plaque is "certainly remarkable in its insistence upon Christian virtue and total silence about the literary distinction which had, presumably, earned her the honor of a cathedral burial."

It seems to me that that your gravestone would be the most unremarkable place for your relatives to insist on your Christian virtues. Kirkham's implication, I suppose, is that the Austens are protesting too much. And we don't know if Austen's burial in the cathedral had any connection to her authorship. (See my previous post for some surmises on why Austen was buried in the cathedral.)

However, other female authors, as we will see, were also praised for their Christian virtues on their gravestones. As for the contention that it was "remarkable" for all mention of Austen's writing to be omitted, we'll look into that as well.

Lately, I've been diving into the novels of the long 18th century and comparing them to Austen's. (For example, here and here ). It occurred to me to ask: did other authors announce their authorship on their tombstones? I started checking, but quickly realized I was asking an apples-to-oranges question. The other authors were known as authors in their lifetimes. Some were very famous. Sometimes the inscription in question is not on their tombstone, but on a memorial plaque. Sometimes the inscription is contemporaneous with their burial, and sometimes it's erected after their death by admirers. That said, if you'd like a nice graveyard tour, come along with me: First stop on our tour is St. Pancras Old Church in Somers Town, London. Mary Wollstonecraft's tomb is famous in literary history because it was here that little Mary Godwin learned to read by tracing the shape of the letters on her mother's tomb, and it was here that the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley courted her. And it was here, some say, that the young couple consummated their love.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 - 1797)

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 - 1797)

Wollstonecraft's monument was set up by some friends and admirers and it states that she is the "author (not authoress) of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman." Mary Wollstonecraft was exhumed by Mary Shelley's daughter-in-law and her remains were re-buried in Bournemouth, but the original monument remains at St. Pancras.

In Austen's time, the best-known female authors were Frances Burney and Maria Edgeworth. Austen admired them both. Their novels are still read today.

In Austen's time, the best-known female authors were Frances Burney and Maria Edgeworth. Austen admired them both. Their novels are still read today. Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849) is buried in the Edgeworth family vault in the church of St John’s, Edgeworthstown, Ireland. I haven't found any mention of a memorial plaque or a special inscription to Maria Edgeworth either on the vault or in the adjoining church.

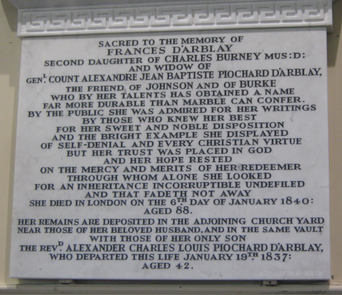

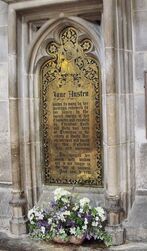

Frances Burney, Madame D'Arblay (1752–1840), was the author of Evelina, Cecilia, and Camilla, among other writings. Her family sarcophagus in Walcot Cemetery in Bath is plain, but her heirs installed a large memorial plaque in their parish church. This plaque was lost during renovations, and the Fanny Burney society raised funds for a replacement. The plaque mentions "her writings" and her fame but it also stresses Burney's sweet and noble disposition and her faith in her Redeemer, just as Austen's plaque does.

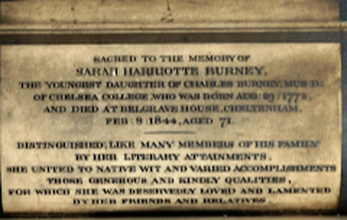

Burney's half-sister Sarah Burney, (1772 – 1844) was also a novelist. I've previously written about her novels

Clarentine

and

Traits of Nature

. Her memorial plaque has been lost though there is a surviving photo of it, shown at right.

Burney's half-sister Sarah Burney, (1772 – 1844) was also a novelist. I've previously written about her novels

Clarentine

and

Traits of Nature

. Her memorial plaque has been lost though there is a surviving photo of it, shown at right. Sarah's plaque spoke of "her literary attainments," which I think is a tasteful way of saying she wrote sentimental novels without saying she wrote sentimental novels.

Given the long-standing criticisms about novels as being inappropriate reading-matter, especially for young women, I have wondered if church authorities wouldn't want novels mentioned on a plaque. Austen scholar EJ Clery thinks this may have been the reason the Austens didn't mention it: "Novels had been her trade, but to the prejudiced, ‘novel’ still carried associations of triviality and dissipation. Henry evidently felt that praise for ‘the extraordinary endowments of her mind’ was a strong enough indication."

Mary Brunton (1778 – 1818), also has a memorial plaque near her grave and here we have an example of one which mentions authorship, even a book title. It says she is the "authoress of Self Control." Mary Brunton's novels had dramatic incidents but were very moralistic and overtly Christian; does this make it more acceptable for a plaque in a churchyard?

Mary Brunton (1778 – 1818), also has a memorial plaque near her grave and here we have an example of one which mentions authorship, even a book title. It says she is the "authoress of Self Control." Mary Brunton's novels had dramatic incidents but were very moralistic and overtly Christian; does this make it more acceptable for a plaque in a churchyard?Self Control, which was a best-seller in its day, is now most famous for what Austen said about it: "I am looking over Self Control again, and my opinion is confirmed of its being an excellently-meant, elegantly-written work, without anything of nature or probability in it. I declare I do not know whether Laura's passage down the American river is not the most natural, possible, everyday thing she ever does." Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743 - 1825) has a memorial plaque in the Newington Green chapel (Newington Green is where the new statue of Mary Wollstonecraft has been erected). Her actual grave looks like a brick storage shed. I've mentioned Barbauld's abolitionist writings in earlier posts as well as her anti-war poem 1811. The plaque praises her writings and her social activism.

ANNA LETITIA BARBAULD,

ANNA LETITIA BARBAULD,Daughter of John Aikin, D.D.

And Wife of The Rev. Rochemont Barbauld,

Formerly the Respected Minister of this Congregation.

She was born at Kibworth in Leicestershire, 20 June 1743,

and died at Stoke Newington, 9 March 1825.

Endowed by the Giver of all Good

With Wit, Genius, Poetic Talent, and a Vigorous Understanding

She Employed these High Gifts

in Promoting the Cause of Humanity, Peace, and Justice,

of Civil and Religious Liberty,

of Pure, Ardent, and Affectionate Devotion.

Let the Young, Nurtured by her Writings in the Pure Spirit

of Christian Morality;

Let those of Maturer Years, Capable of Appreciating

the Acuteness, the Brilliant Fancy, and Sound Reasoning

of her Literary Compositions;

Let the Surviving few who shared her Delightful

and Instructive Conversation,

Bear Witness

That this Monument Records

No Exaggerated Praise. Felicia Dorothea Hemans (1793–1835) was a well-regarded and popular poet. Her best-known poem is The Boy Stood on the Burning Deck.

Her inscription quotes one of her poems:

In the vault beneath/Are deposited the mortal remains of

Felicia Dorothea Hemans/She died May 16th 1835/Aged 41 Calm on the bosom of thy God

Fair spirit rest thee now!

Even while with us thy footstep trod

His seal was on thy brow

Dust to its narrow house beneath

Soul to its place on high

They that have seen thy look in death

No more may fear to die

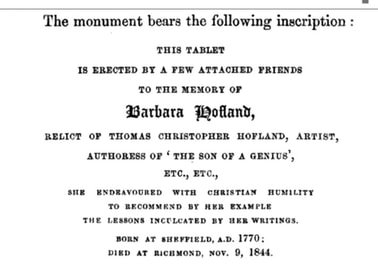

I wonder if Austen had been a composer of sacred verse, rather than a novelist, would that have been mentioned on her inscription? Barbara Hofland (1770 - 1844) was a prolific author and the memorial sculpture set up in her honour mentions her authorship. This is three decades after Austen's death and perhaps the big debate around the pernicious effect of novels had died down somewhat. Hofland's novels, like Mary Brunton's, were very didactic and overtly Christian.

I wonder if Austen had been a composer of sacred verse, rather than a novelist, would that have been mentioned on her inscription? Barbara Hofland (1770 - 1844) was a prolific author and the memorial sculpture set up in her honour mentions her authorship. This is three decades after Austen's death and perhaps the big debate around the pernicious effect of novels had died down somewhat. Hofland's novels, like Mary Brunton's, were very didactic and overtly Christian.

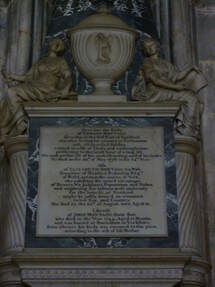

Let's look at what was said about Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, (1718-1800). Her memorial plaque commemorating her, her husband, and their infant son, is also in Winchester Cathedral.

Let's look at what was said about Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, (1718-1800). Her memorial plaque commemorating her, her husband, and their infant son, is also in Winchester Cathedral.Wikipedia describes her as "a British social reformer, patron of the arts, salonnière, literary critic and writer, who helped to organize and lead the Blue Stockings Society." However, her memorial plaque, while laudatory, is not nearly so specific as Wikipedia in respect of her accomplishments. It says she possessed "the united advantages of beauty, wit, judgement, reputation and riches, and employing her talents most uniformly for the benefit of mankind, might be justly deem'd an ornament to her Sex, and Country." While she was famous during her lifetime there is no mention of her published works, which, like Austen's, were published anonymously. We have to remember that well-born people in those days took a very different public attitude toward literary fame, however they might have felt about it privately. As a gentlewoman, putting her name on her writing--even acknowledging that she published--was beneath Montagu's dignity. "It was merely a matter of form," John Mullan explains.

(Hmm, that inscription does remind one of Emma, doesn't it? Handsome, clever and rich...) Here are more writers whose authorship is not mentioned on their gravestones: Mary Shelley (1797-1851) is buried in Bournemouth with her father William Godwin, her mother Mary Wollstonecraft, and her son and daughter-in-law. Her gravestone has all the family names and the dates , plus the information that she is the widow of Percy Bysshe Shelley . Her gravestone does not say "author of Frankenstein."

Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855) was a prolific author. Her best known work is Our Village. She's also famous for her letters. But she is perhaps best known today

for a passing remark

she made about Austen in her private letters.

Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855) was a prolific author. Her best known work is Our Village. She's also famous for her letters. But she is perhaps best known today

for a passing remark

she made about Austen in her private letters. Mitford's simple grave marker appears to only state her name and dates.

Amelia Opie (1769 – 1853) was best known for her novel Adeline Mowbray. She was a Quaker. Like Hannah More (below), she was an abolitionist.

Amelia Opie (1769 – 1853) was best known for her novel Adeline Mowbray. She was a Quaker. Like Hannah More (below), she was an abolitionist. “Should any wanderer, at some future day, desire to visit the grave of Amelia Opie, he will find, at the extreme left side of the ground, beneath an elm tree that overshadows the wall, a small slab, bearing the names of [her father] James Alderson and Amelia Opie, with the dates of their births and deaths.” -- from Memorials of the Life of Amelia Opie.

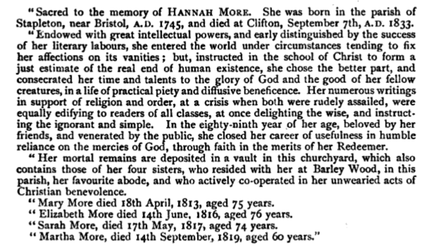

Hannah More (1745 – 1833) was prolific, successful, and famous in her lifetime. She was also notably pious. Her tombstone carries only her name and dates.

Hannah More (1745 – 1833) was prolific, successful, and famous in her lifetime. She was also notably pious. Her tombstone carries only her name and dates.  Hannah More is buried with her five sisters in All Saints Churchyard Wrington, in Somerset. Their tomb slab lists only their names and dates. More's tomb says nothing about her virtues or her accomplishments. More practised an austere form of Anglicanism, and I can't see her arranging to promote her virtues or her writing on her tombstone. "Just as I am, without one plea," as the

good old Methodist hymn

says.

Hannah More is buried with her five sisters in All Saints Churchyard Wrington, in Somerset. Their tomb slab lists only their names and dates. More's tomb says nothing about her virtues or her accomplishments. More practised an austere form of Anglicanism, and I can't see her arranging to promote her virtues or her writing on her tombstone. "Just as I am, without one plea," as the

good old Methodist hymn

says. However, years after her death a memorial plaque was installed in the church by her admirers, that explains her "numerous writings" were edifying to the "ignorant and simple."

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), poet and novelist, is buried with his wife in in the romantic Gothic ruins of Dryburgh Abbey in Scotland in a plain sarcophagus with only their names and dates. When Scott died, he was so famous that it wasn't necessary to explain who he was on his tomb. He also has a memorial in Edinburgh which is the largest memorial to an author in England, and the second largest in the world.

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), poet and novelist, is buried with his wife in in the romantic Gothic ruins of Dryburgh Abbey in Scotland in a plain sarcophagus with only their names and dates. When Scott died, he was so famous that it wasn't necessary to explain who he was on his tomb. He also has a memorial in Edinburgh which is the largest memorial to an author in England, and the second largest in the world. Other authors outlived their fame. The novelist Selina Davenport (1779-1859), died after years of poverty and has no headstone. Charlotte Lennox (1730-1804) author of The Female Quixote, a book that inspired Austen's Northanger Abbey, was famous in her lifetime but died poor and was buried in an unmarked grave in Broad Court cemetery in Covent Garden.

All the authors we've looked at in this post were known as authors in their lifetimes. Austen's authorship was revealed at the time of her death in an obituary placed by the family in a London newspaper and later, in the two novels (Persuasion and Northanger Abbey) which were published posthumously.

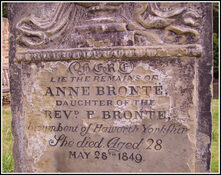

All the authors we've looked at in this post were known as authors in their lifetimes. Austen's authorship was revealed at the time of her death in an obituary placed by the family in a London newspaper and later, in the two novels (Persuasion and Northanger Abbey) which were published posthumously.Anne Bronte (1820-1849), like Austen, died away from home. Her gravestone, erected by her sister Charlotte, did not mention her authorship. Anne was not famous when she died, though I believe she had been revealed as being the author "Acton Bell." A more recent plaque adds the information that she was a poet and novelist.

Charlotte (1816-1855) and Emily Brontë (1818-1848), are buried in a vault beneath their church. There is a tablet in the church for them and a memorial tablet with their names and dates at Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey. So the female English novelists who come closest to Austen in lasting fame did not have gravestones that announce their authorship, either. In conclusion, we can at least say that it wasn't a given that authors were listed as authors on their gravestones. But the reasons for this may vary -- poverty at death, a level of fame that rendered explanations unnecessary, religious scruples about turning your gravestone into a billboard, interment in a common family vault, or choices made by the surviving relatives.

At least the inscription on Austen's gravestone shows the great love her family had for her. As with Anna Letitia Barbould and Hannah More, her talents are modestly referred to as endowments. That is, she was endowed by her Creator with genius. Was it modesty that prevented her from asking that her identity as a novelist be revealed on her gravestone? And yet, she is buried in the Cathedral--is this a quiet pride, a knowledge that she would be remembered? Austen knew all of these emotions could coexist at once in "a mixture of pride, love, and delicacy."

In the next few posts, I will continue to compare Austen to some of her contemporaries. In this post it was gravestones, next we'll move on to social activism.

This website has more graves of poets and writers. 75 more here , and few of them mention their authorship. The 17-year-old poet Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) was buried in a pauper's grave. His story is told here.

Published on July 21, 2021 00:00

July 18, 2021

CMP#60 Private Virtues, Public Renown

"In May 1817 she was persuaded to remove to Winchester... All that was gained by the removal from home was the satisfaction of having done the best that could be done, together with such alleviations of suffering as superior medical skill could afford."

"In May 1817 she was persuaded to remove to Winchester... All that was gained by the removal from home was the satisfaction of having done the best that could be done, together with such alleviations of suffering as superior medical skill could afford." -- Memoir of Jane Austen, by her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh Private Virtues, Public Renown

Austen stayed in lodgings near Winchester Cathedral Jane Austen spent the final two months of her life in Winchester, 16 miles away from her home in Chawton. The official family version is that Austen "was persuaded" to go to Winchester for medical help. When she left Chawton for the last time on May 24th, no doubt everyone was hoping for a medical miracle. Within a fortnight, however, Austen's medical practitioner in Winchester concluded that her case was hopeless. She lingered on until mid-July, dying on July 18th.

Austen stayed in lodgings near Winchester Cathedral Jane Austen spent the final two months of her life in Winchester, 16 miles away from her home in Chawton. The official family version is that Austen "was persuaded" to go to Winchester for medical help. When she left Chawton for the last time on May 24th, no doubt everyone was hoping for a medical miracle. Within a fortnight, however, Austen's medical practitioner in Winchester concluded that her case was hopeless. She lingered on until mid-July, dying on July 18th.If nothing could be done for Austen in Winchester, could there be another reason why Austen chose to remain there, to spend her last days in a strange town? Instead of dying in her own bed at home? Even the extra expense of taking lodgings was no idle consideration for this family. Perhaps her rich brother Edward stepped up to help or perhaps Jane paid for the lodging, food, doctor and nurse out of her own earnings, but this was a family of very modest means that had recently suffered the catastrophe of brother Henry's bank failure and had been disappointed by last will and testament of a wealthy uncle.

So why the 11th-hour trip to Winchester? I incline toward the theory that it was because of a wish on Austen's part to put distance between herself and her mother. Austen's mother was thought to be a bit of a hypochondriac. Personally, I think a woman who has borne eight children deserves to be a hypochondriac if she wants to be. However I suspect the reality of her daughter's illness was something she was unwilling or unable to face. For a year, Austen herself had tried to minimize and dismiss her recurring symptoms and her slow decline. By the spring of 1817, the truth could no longer be hidden.

Was Austen sparing her own feelings by leaving home to die, or was she sparing her mother's feelings? Or both? Jane's mother was 78 years old at the time, and although she lived for another ten years, we might suppose that keeping constant attendance by her dying daughter's bed would have been an enormous strain for her. Jane saw to it that this never happened. Nor, it seems, was it essential to Jane Austen that her mother be with her during those last days. That role was filled by Cassandra, was assisted by their sister-in-law and a maid.

Naturally enough, Austen and Cassandra tried to soothe and reassure their mother. Austen biographer Claire Tomalin says Austen's mother "was sent optimistic bulletins" from Winchester. But she did not go to visit her daughter in Winchester.

"Your grandmamma has suffered much," Austen's brother Henry wrote to his niece, after they got the bad news from Dr. Lyford in early June, "but her affliction can be nothing to Cassandra's." Other family members came and went during those last weeks and days, to say good-bye. The surviving record shows Austen's thoughts were engaged with being "fit to appear before [God] when I am summoned," in accordance with the Christian doctrines in which she believed. Winchester cathedral was on her mind as well. She composed a witty poem about St. Swithin, patron saint of the cathedral, shortly before her death. In one of her last letters, she joked that "Mr. Lyford says he will cure me, and if he fails, I shall draw up a memorial and lay it before the Dean and Chapter, and have no doubt of redress from that pious, learned, and disinterested body." Lying in her rented rooms, she must have been within the sound of the cathedral bells. The prospect of being laid to rest in the cathedral was probably another motive for Austen's remaining at Winchester.

Austen died on July 18th, 1817 and was buried early in the morning on the 24th. Her older brother James wrote a poem in tribute to her: "But to her family alone / her real, genuine worth was known."

And someone arranged a burial place for her which was more elaborate, more public, than any other member of the family received.

"Why was Austen buried in Winchester Cathedral?" This FAQ is from

Winchester Cathedral's website,

but the posted answer is rather unsatisfactory. It merely says that Austen moved to lodgings in Winchester shortly before her death and was buried in the cathedral, "a building she greatly admired."

"Why was Austen buried in Winchester Cathedral?" This FAQ is from

Winchester Cathedral's website,

but the posted answer is rather unsatisfactory. It merely says that Austen moved to lodgings in Winchester shortly before her death and was buried in the cathedral, "a building she greatly admired."But this does not answer the question. Not everyone who dies in Winchester or admires the cathedral is buried there. Claire Harmon's biography of Austen says that only three people were buried in the cathedral that year.

The graves of Austen's sister and mother in Chawton. And if you look at the list of

eminent people who have been buried

there over the centuries, you have to wonder how the Rev. George Austen's daughter had enough "pull" to join that select group. In addition to

Anglo Saxon kings

, a more recent example during Austen's time was Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, founder of the Bluestockings.

The graves of Austen's sister and mother in Chawton. And if you look at the list of

eminent people who have been buried

there over the centuries, you have to wonder how the Rev. George Austen's daughter had enough "pull" to join that select group. In addition to

Anglo Saxon kings

, a more recent example during Austen's time was Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, founder of the Bluestockings. It is generally supposed that Austen's brother Henry pulled some strings for his sister. His career as a banker had ended by that time, but he was an accomplished--even shameless--networker and string-puller. As well, the inscription prominently mentions Austen's late father, who might have had connections in the Anglican establishment who still remembered him with respect. Another possible connection was through Elizabeth Heathcote, who lived near the cathedral, a friend of Jane and Cassandra. In fact, she was the sister of Harris Bigg-Wither, the man who proposed marriage to Austen. Mrs. Heathcote was the widow of a clergyman.

So, in addition to asking, why did Austen go to Winchester, we can add the questions: where did she want to be buried, and did she know her family was going to reveal the secret of her authorship after her death?

There is no consensus among Austen scholars and devotees about the answers. EJ Clery believes that Henry was probably behind the cathedral burial: "To bury her in the Cathedral was an act of faith in her future fame." Claire Tomalin thinks Henry might have overruled his sister's wishes: "splendid as [the cathedral] is, she might have preferred the open churchyard at Steventon or Chawton."

The most vexed question is: what about the wording of the inscription on the slab which marks her final resting place? It stresses her virtues and the family's grief, but does not mention her authorship. Suffice it to say many people have questioned and criticized Austen's family for not mentioning Austen's authorship on the tombstone. Why bury her in such a public place, and only expiate on her private virtues? That question will be considered in my next post. In the meantime, two other points about her fame and her resting place:

Austen's authorship was revealed in newspaper obituaries after her death. From there, her fame grew slowly and steadily through the 19th century. An article in Texas Studies in Literature and Language by Janine Barchas and Devoney Looser describes how, "As Austen's fame increased, the need for a monument, shrine, or celebration on a similar scale was periodically debated in the press." Austen adherents looked at the large monument raised to Sir Walter Scott in Edinburgh and argued that Austen deserved a monument of her own. "The proceeds from [her nephew's] biography were eventually used to install a brass memorial tablet beside her grave in the cathedral. The wording of the brass plaque is as follows:

Austen's authorship was revealed in newspaper obituaries after her death. From there, her fame grew slowly and steadily through the 19th century. An article in Texas Studies in Literature and Language by Janine Barchas and Devoney Looser describes how, "As Austen's fame increased, the need for a monument, shrine, or celebration on a similar scale was periodically debated in the press." Austen adherents looked at the large monument raised to Sir Walter Scott in Edinburgh and argued that Austen deserved a monument of her own. "The proceeds from [her nephew's] biography were eventually used to install a brass memorial tablet beside her grave in the cathedral. The wording of the brass plaque is as follows: 'Jane Austen known to many by her writings, endeared to her family by the varied charms of her Character and ennobled by Christian faith and piety, was born at Steventon in the County of Hands Dec. xvi mdcclxxv, and buried in this Cathedral July xxiv mdcccxvii “She openeth her mouth in wisdom and in her tongue is the law of kindness.” Prov xxxi. v. xxvi'"

The family emphasized 1) their love for her, 2) her Christian virtues, and 3) her charming personality. The plaque just reiterates what was said on the tombstone. The only addition is the vague: "known to many by her writings."

Later still, there was a public subscription drive to add a stained glass window . More recently, an attempt to erect a statue in Austen's honour was cancelled. Lastly, in an earlier blog post on religion, I mentioned Dr. Helena Kelly's theory that Austen must have intended for her novels to be included in the inscription and that's why she wanted to be buried in Winchester Cathedral. Specifically, she wanted the title of Mansfield Park inscribed as a lasting and pointed rebuke to the Anglican church. This theory relies upon the following suppositions:Mansfield Park is a radical anti-slavery novel.The references to slavery are nonetheless veiled because it was dangerous and unpopular to speak out against slavery.Mansfield Park is specifically a critique of the Church of England's ownership of slave plantations, the Codrington plantations. Having Mansfield Park on her tombstone would have been widely understood as a rebuke to the Anglican church.Austen was the sort of person who would arrange to turn her tombstone into a lasting protest sign in a beautiful sacred space where people had worshipped for 800 years. "Jane, in her wilder moments, could have delighted in getting the title of her anti-church, antislavery novel into a cathedral run by slave owners." I think every one of those assertions is based on zero evidence and ignores much counter-evidence, and (2) in particular is factually incorrect. Next post: "Behold Me Immortal"

An earlier post written for the anniversary of Austen's death is here.

Austen's brother, Rear Admiral Charles Austen, died at sea. A recent article shows his long-forgotten memorial in Sri Lanka.

Barchas, Janine and Devoney Looser. "Introduction: What's Next for Jane Austen?" Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 61 no. 4, 2019, p. 335-344. Project MUSE

Published on July 18, 2021 00:00

July 15, 2021

CMP#59 Jaw-Dropping 18th Century Kiddie Lit

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times in which she lived. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times in which she lived. Click here for the first in the series. This post features another now-obscure female writer of Austen's time. For more, click on "Authoresses" in the Categories. The Rotchfords: a Graphic Novel, and I Don't Mean a Comic Book

You've been warned... The Rotchfords (1786)

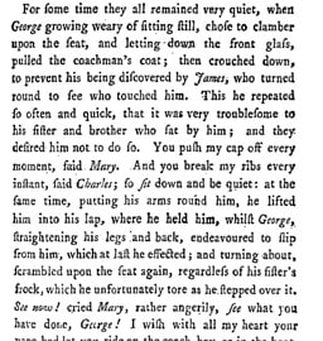

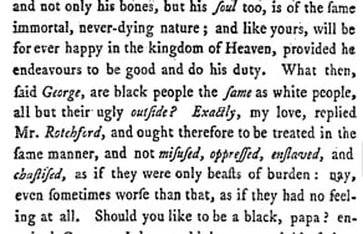

is a children’s book by Dorothy Kilner (1755 –1836) about an upright Christian family. Like almost all children’s literature of the Regency and Victorian period, the book is heavily finger-waggy; it is filled with useful moral lessons for the little ones. One of the lessons Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford teach their children is that Blacks are people too.

You've been warned... The Rotchfords (1786)

is a children’s book by Dorothy Kilner (1755 –1836) about an upright Christian family. Like almost all children’s literature of the Regency and Victorian period, the book is heavily finger-waggy; it is filled with useful moral lessons for the little ones. One of the lessons Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford teach their children is that Blacks are people too.While it's good to know that books for children talked about showing humanity to Black people, the graphic detail, the portrayal of the Black servant Pompey, and the actions of the father, are rather jaw-dropping.

Pompey’s recitation of the cruelties he’s witnessed and experienced in the West Indies and in England is brutally frank for a children’s book. As scholar Wylie Sypher wrote in 1942, The Rotchfords goes “from the pathetic to the shocking in the harrowing Pompey episode." And Pompey’s story is just one bizarre episode in a bizarre book – bizarre to our modern sensibilities, that is. Athough Dorothy Kilner and her sister-in-law Mary Anne Kilner wrote children's books which portray real children behaving in realistic ways (for example, squabbling as they ride in the carriage), The Rotchfords reminds us that the 18th century featured more random pain and death, more casual cruelty, and more hunger and misery than we witness at first hand today.

Some examples: the youngest Rotchford boy learns the hard way that you don’t lark about in a carriage – he impulsively sticks his arms though a glass barrier and cuts himself badly. One of his arms has to be amputated, and this was before anesthesia. On another occasion, Mr. Rotchford tells his son about a bad-tempered man who beat his grandson to death for stealing peaches. Moral: don’t steal and don’t lose your temper.

Think that was harsh? Try this: A few days after a local boy pulls the tail off her pet squirrel and then strangles it to death, Kitty is surprised to see it decomposing and being eaten by worms and maggots. She asks her father, “could you have thought it possible for it to alter so?”

Mr. Rotchford uses the dead squirrel to teach a lesson about the uselessness of vanity.

No seat belts in Georgian carriages, so little George jumps around and bothers his brother and sister. Charles raises the glass barrier so Charles will stop bothering James the coachman, but tragedy follows. Patting Kitty on the cheek, dad assures her, “'you yourself will undergo as great an alteration in a very few days after your death. All [your] bloom, my love… will then be entirely gone…'

No seat belts in Georgian carriages, so little George jumps around and bothers his brother and sister. Charles raises the glass barrier so Charles will stop bothering James the coachman, but tragedy follows. Patting Kitty on the cheek, dad assures her, “'you yourself will undergo as great an alteration in a very few days after your death. All [your] bloom, my love… will then be entirely gone…' “'And will such nasty fat-looking maggots eat me up too?” daughter Harriot asks.

“'Yes, indeed,” said Mr. Rotchford, chucking her under the chin as he spoke, ‘they will not pay respect even to your dead body; but will eat my little Harriot with as much relish as if she was but a squirrel….'"

At the time of its publication, the critics did not comment on the graphic nature of The Rotchfords. Amputation, beating children to death, and torturing squirrels, are "common occurrences" in Georgian England. But they thought the dialogue was unpolished.

Black servant as ornamental status symbol Mr. Rotchford’s interactions with Pompey also seem incredibly callous to our modern sensibilities. (Some enslaved men were given Roman names like "Pompey" and "Caesar.") Rotchford and his son Charles come upon 12-year-old Pompey weeping and shivering at the side of the road. He tells how his master, Mr. Chromis, overworked him, beat him and denied him food. Starving, he stole some food and then a little money. Mr. Chromis kicked him out of the house.

Black servant as ornamental status symbol Mr. Rotchford’s interactions with Pompey also seem incredibly callous to our modern sensibilities. (Some enslaved men were given Roman names like "Pompey" and "Caesar.") Rotchford and his son Charles come upon 12-year-old Pompey weeping and shivering at the side of the road. He tells how his master, Mr. Chromis, overworked him, beat him and denied him food. Starving, he stole some food and then a little money. Mr. Chromis kicked him out of the house.Mr. Rotchford replies: “I am sorry for it, but I cannot help it, you ought not to have robbed your master.”

Since this occurs after Lord Mansfield's Somerset decision , Pompey is not a slave. The issue is, will anyone feed him or give him a job? Apparently this was a big problem for hundreds of free Blacks after the Somerset decision. If they left their former owners, they could not necessarily find or keep another job, and since they were not considered to be members of any parish, they could not obtain parish charity. At the same time The Rotchfords was published (1786), the abolitionist Granville Sharp was collecting donations to send 400 indigent Blacks to Africa to start a colony at Sierra Leone.

Young Charles Rotchford pleads for Pompey, and his father answers, “I do not want a black boy; besides, by his own account, he has been dishonest, and robbed his master.”

Charles continues to ask for mercy for Pompey, who, let’s remember, is a crying, starving, half-naked child. Finally Mr. Rotchford smiles and tells Charles, “Believe me, I had no intention of leaving him there to perish, but I wished to hear your sentiments upon the subject.” Thanks to Pompey's suffering, Charles has passed the moral test. They take Pompey home, where he is fed and clothed and handed over to the gardener to be his under-servant.

The youngest Rotchfords are alarmed by Pompey's appearance. I've seen this in other books of this era; British children are portrayed as being surprised or frightened at the appearance of Black people, or thinking the black colour will wash off their skins. Mrs. Rotchford reminds the children that standards of beauty are different in different parts of the world and it's not Pompey's fault that his lips stick out. “Is that any reason why [Pompey] should not be treated with kindness?"

Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford are uncompromising about the cruelty and immorality of the slave trade in their lectures to their children. And Pompey tells how he and his mother were abducted from their homes in Africa. His mother fell ill in the West Indies but was whipped in the sugar fields. His older brother was tortured to death for trying to protect her from the overseer’s lash. Then Pompey was sold to a man who brought him to England to be a page boy, but he was passed on to Mr. Chromis, who abused and starved him.

Pompey forthrightly says that he doesn’t like Christians because of what Christians have done to him and his family. Mrs. Rotchford acknowledges: “At present, I am not at all surprised, that he should entertain an ill opinion of a religion, [whose] members he has found to be barbarous, tyrannical and unjust…”

Mrs. Rotchford also lectures her children about the guilt of the slave-trader versus the lesser guilt of the slave-owner.

As scholar George E. Boulukos explains, and as The Rotchfords illustrates, slave-traders were held as being more blameworthy than slave-owners at this time. Slave-traders were motivated purely by greed, but slave-owners "might buy [enslaved persons] with a good intention of preventing their falling into cruel hands, and meeting with unkind treatment, and mean afterwards to give them their freedom, as I believe they have to most of them. We must not, therefore, my dears, presume to condemn every body as wicked, who may be in possession of a negroe, without knowing how, or for what reasons..."

Little George is surprised that Pompey's blood is red like his... Mr. Rotchford continues to express his doubts about allowing Pompey to stay with them. He writes to his former master, Mr. Chromis, to check the truth of Pompey's version of events. Mr. Rotchford's goal was "to endeavour to find out [Pompey's] sentiments and temper; whether he appeared as if indeed desirous of pleasing, and being good; or whether he only liked to stay for the sake of his food... For this reason, therefore, and not for the sake of occasioning him one moment’s suspense or pain, I refrained from telling him my design, till I saw how the thoughts of his departure would affect him; and whether he would esteem his continuing here an obligation worthy of being requited by his gratitude and fidelity.”

Little George is surprised that Pompey's blood is red like his... Mr. Rotchford continues to express his doubts about allowing Pompey to stay with them. He writes to his former master, Mr. Chromis, to check the truth of Pompey's version of events. Mr. Rotchford's goal was "to endeavour to find out [Pompey's] sentiments and temper; whether he appeared as if indeed desirous of pleasing, and being good; or whether he only liked to stay for the sake of his food... For this reason, therefore, and not for the sake of occasioning him one moment’s suspense or pain, I refrained from telling him my design, till I saw how the thoughts of his departure would affect him; and whether he would esteem his continuing here an obligation worthy of being requited by his gratitude and fidelity.”Pompey, in other words, must prove that he is not motivated by mere selfish considerations such as avoiding starving to death by the roadside.

This seems appalling, and yet, how much of Pompey's treatment can we ascribe to the fact of his being Black? Would the Rotchfords have taken in any and every hungry, half-naked boy that they saw? Elsewhere in the book we read about a another hungry child: "As I was walking down the lane this morning before breakfast, [Charles tells his father] I met Bob Swift, as naked and in as bad a condition as Pompey was when we found him, crying most piteously, and gathering sticks for his mother. He begged me to give him an halfpenny… then again, I recollected that you positively ordered none of us to give more to the Swifts, because they have been extremely wicked, and ungrateful.”

It's a harsh world. Pompey has been kidnapped from his home, orphaned and abused, and he'll never see his home or family again, but he must earn his keep.

Mr. Rotchford relents and says Pompey can stay. “'Me be good! me be good!,'” Pompey promises, "kissing his master’s hand, and jumping about the room, hallowing, singing, dancing, and shewing every sign of immoderate joy that he could express; then throwing himself on the floor, he clasped and kissed Ms. Rotchford’s knees; then did the same to Charles.

The Rotchfords ends abruptly, and we are not told what becomes of Pompey as he grows; whether he is paid a wage, whether he stays with the family for the rest of his life, or whether he learns a trade.

Dorothy Kilner (1755 - 1836) The Rotchfords was reprinted and excerpted into the 19th century. Professor Srinivas Aravamudan included the Pompey episode in the anthology series Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period. As he pointed out: “While sterile critical debates have raged over the extent to which a novel such as Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) is anti-slavery in its sensibility… much of this recent criticism has not expanded into a reconsideration of the wider arena."

Dorothy Kilner (1755 - 1836) The Rotchfords was reprinted and excerpted into the 19th century. Professor Srinivas Aravamudan included the Pompey episode in the anthology series Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period. As he pointed out: “While sterile critical debates have raged over the extent to which a novel such as Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) is anti-slavery in its sensibility… much of this recent criticism has not expanded into a reconsideration of the wider arena." And when we look at this wider arena we can clearly see that it was not taboo to write about slavery, as I've noted before . The author of The Rotchfords, Dorothy Kilner was writing to make money, not alienate her readers. There was a market and an audience for pro-abolition literature. The review was critical of Kilner's prose style, but made no objection to the anti-slavery material.

Moira Ferguson calls Kilner's lectures, placed in the mouths of Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford, “one of the fiercest fictional statements by a female writer before abolition.”

Scholar Cheryl Turner describes Kilner as one of the "obscure novelists who have virtually disappeared from our literary histories." Kilner published under the pseudonyms M.P. and Mary Pelham, hiding her authorship to maintain her middle-class respectability. Her best-known work was The Life and Perambulations of a Mouse. If it's true that this was the first children's book written from the perspective of an animal (the most famous example of this genre is Black Beauty), then Kilner was an innovator as well.

Ferguson, M. (2014). Subject to others : British women writers and colonial slavery, 1670-1834, Routledge.

Sypher, W. (1969). Guinea's captive kings : British anti-slavery literature of the XVIIIth century. Octagon Books.

Turner, Cheryl. (1993). Living by the Pen: Women Writers in the 18th Century (1st ed.). Routledge.

Published on July 15, 2021 00:00

July 12, 2021

CMP#58 The Dangers of Novels, part 3

And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. -- from Jane Austen's defense of the novel in Northanger Abbey CMP#58 The Dangers of Novels, part 3

Abelard & Heloise In my last two blog posts (part 1 here) and

(part 2 here)

I've been discussing the dangers of novel-reading as Jane Austen's contemporaries viewed the problem.

Abelard & Heloise In my last two blog posts (part 1 here) and

(part 2 here)

I've been discussing the dangers of novel-reading as Jane Austen's contemporaries viewed the problem.A 1799 book review in The Quarterly Review explains the biggest concern -- impressionable young people are so caught up in sentimental romance, that real life seems tame in comparison: “those romantic visions which throw into a dead gloom the brightest scenes of real life. And yet, “real life is the very thing which novels affect to imitate; and the young and inexperienced will sometimes be too ready to conceive that the picture is true, in those respects at least in which they wish it to be so. Hence both their temper, conduct and happiness may be materially injured."

Real life, even real love, and the realities of married life, are nothing like a sentimental novel. The Quarterly Review warns that novels teach susceptible young ladies to believe that “no sacrifice can be too great for real love; that real love such as subsists, and ever will subsist, between herself and the best of men, is adequate to fill every hour of her existence, and to supply the want of every other gratification, and every other employment.” This was, as I said, a wide-spread concern, and susceptible women of this type frequently figured in novels and plays.

The 1796 play, The Generous Attachment, takes on the dangerous romance issue and also touches on the concern that fictional suffering in novels made women indifferent to real suffering.

In the opening scene, Mr. Mortimer interrupts his wife while she is reading (and presumably weeping) over a Gothic novel. She complains: “here have you now, by your boisterous intrusion, disturbed my mind from the delightful tract of sensibility it was thrown into, from musing over the distresses of the charming Emily in that exquisite production of female genius The Mysteries of Udolpho.”

“I wish, Mrs. Mortimer,” he answers, “you would extend your feelings of sensibility to living objects as well as fancied woes, and imaginary distresses.”

She retorts: “ideas are floating on my imagination, and I am building castles in the air with the man I could love, with a total forgetfulness of the man I am married to... and from the regions of delight to which I was ascending, [you] bring me down to a level with the inhabitants of this world, and only to consider myself as plain Mrs. Mortimer."

“And if you were only to consider yourself as plain Mrs. Mortimer, my dear, I believe no one who knows you, would accuse your consideration of telling a falsity.”

This satire was a little too heavy-handed even for Georgian audiences, because I can find no record that this play (which was published at the author's expense), was ever performed.

The Reader of Novels by Antoine Wiertz c 1853 Author Elizabeth Helme, who was a more successful author, frequently moralized against the dangers of novels.

The Reader of Novels by Antoine Wiertz c 1853 Author Elizabeth Helme, who was a more successful author, frequently moralized against the dangers of novels. Her book Instructive Rambles extended, in London and the adjacent villages (1811) is not a novel but it contains short fictional anecdotes including the sad tale of a poverty-stricken widow who lays the beginning of her downfall to the fact that she read too many novels when young. Her mother had the habit, so she followed her parent's example:

After being widowed, the mother "retired into the country; and naturally of a pensive disposition, her only amusement was reading; and a wish, perhaps, to banish unpleasant thoughts, led her to the perusal of books which, though they might sometimes beguile an uneasy hour, were undoubtedly unfit for me to be suffered to indulge in; which was frequently the case.

"From reading these, as I grew up, I formed fallacious opinions of human nature; and too ignorant and unacquainted with life to draw a middle line, my inflated imagination presented my fellow creatures as either perfect beings or monsters of deformity. Romances had represented some characters as perfectly happy; and resolved to be so myself…”

The foolish girl enters into marriage but: “Alas! I was disappointed; the shadow again beguiled me; my husband possessed neither religion, good-humour, nor humanity. Charmed with his fine person, I had never considered further… He was also a gamester…”

The same author wrote in her novel Modern Times (1814) about a spoilt young girl whose “education had been erroneous in the extreme… she had been indulged in an indiscriminate perusal of novels, and her ideas had kept pace with this species of literature.” As a result, she is susceptible to flirtation: “Her head was stored with lovers—honorable and dishonorable, the mere distinction of which, to a young, giddy and vain girl, like Fanny Neville, appeared immaterial…”

In her novel Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarvon (1799), the young heroine Gertrude falls a victim to this hyper-romanticism and secretly pledges her love to her brother's tutor, who only wants her money. Gertrude's aunt laments: “her brain was heated, and her mind empoisoned with the romantic pursuits she was continually imbibing.” The phrase "her brain was heated," suggests a quasi-scientific view of the effect of titillating novels on an impressionable girl's mind. My brother has alerted me to this warning from the April 1849 Scientific American: Dr. W.H. Stokes advises that: “Another fertile source of this species of derangement [moral insanity] appears to be an undue indulgence in the perusal of the numerous works of fiction, with which the press is so prolific of late years, and which are sown widely over the land, with the effect of vitiating the taste and corrupting the morals of the young. Parents cannot too cautiously guard their young daughters against this pernicious practice.” The quote is from his annual report for the Mount Hope Institute for the Insane. Dr. Stokes reported his institute "had seen several cases of moral insanity, for which no other cause could be assigned but excessive novel reading."

Austen agrees that what we read affects our character and our mood: in Persuasion, heroine Anne Elliot recommends that Captain Benwick read more inspiring memoirs and moral essays and less romantic poetry: "she thought it was the misfortune of poetry to be seldom safely enjoyed by those who enjoyed it completely; and that the strong feelings which alone could estimate it truly were the very feelings which ought to taste it but sparingly."

Spinsters, or old maids, were fair game for comedy in Georgian England Although Austen defended novels as a species of literature deserving of respect, she also laughed at them. In Love and Freindship, her hilarious parody of sentimental novels, Austen blames the insanely reckless behaviour of her protagonists on novels. The hero tells his father he will not marry the woman of his father's choice, "No! Never shall it be said that I obliged my Father."

Spinsters, or old maids, were fair game for comedy in Georgian England Although Austen defended novels as a species of literature deserving of respect, she also laughed at them. In Love and Freindship, her hilarious parody of sentimental novels, Austen blames the insanely reckless behaviour of her protagonists on novels. The hero tells his father he will not marry the woman of his father's choice, "No! Never shall it be said that I obliged my Father."“Sir Edward was surprised; he had perhaps little expected to meet with so spirited an opposition to his will. 'Where, Edward in the name of wonder (said he) did you pick up this unmeaning gibberish? You have been studying Novels I suspect.' I scorned to answer: it would have been beneath my dignity. I mounted my Horse and followed by my faithful William set forth for my Aunts.”

Austen's not the only one who had a good laugh at sentimental novels. in the 1799 play Laugh When You Can, one of the comic characters is Miss Gloomly, a prolific writer or dramatic works. MIss Gloomly scolds a young man to "leave off grinning and smiling."

"Excuse me," he answers, 'it’s impossible."

"Impossible!" she exclaims. "Read my works, and then see if it’s impossible."

Miss Gloomly wants to marry Mr. Mortimer, but, as her maid Dorothy says, “Mr. Mortimer won’t hear of a divorce [from his wife].”

"Brute! idiot!" the scorned Miss Gloomly responds. "And did he send no message, Dorothy?"

"None, madam," answers Dorothy, "and when I asked him if this was treatment for the author of Artemisia, the Victim of Sensibility, and The Confusions of the Soul--"

"Effusions, girl!" snaps MIss Gloomly. "How often must I correct you? Effusions of the Soul, besides, elegies, sonnets, and other pathetic and moral publications."

In Austen's final and unfinished work, Sanditon, sentimental novels are again slighted. Heroine Charlotte Heywood visits a circulating library that also sells useless but pretty trinkets. She feels that at the ripe old age of 23 she should resist the lure of the "drawers of rings and brooches." She also considers but rejects a sentimental novel. "She took up a book; it happened to be a volume of Camilla. She had not Camilla's youth, and had no intention of having her distress; so she... repressed further solicitation and paid for what she had bought."

Camilla, the titular heroine of Fanny Burney's popular novel, was only 17. Camilla was one of the works Austen named in Northanger Abbey as a "work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." But then, Charlotte Heywood does not reject Camilla on the grounds of its merits as literature, she rejects it because she can't relate to the heroine.

Charlotte's verdict on Camilla is one of several hints that Sanditon would involve a satirical handling of the melodramatic plots of sentimental novels. Perhaps she, too, was going to explore the way novels were confused for real life. She had already had fun with Gothic novels in Northanger Abbey. As we have seen, many other authors wrote about novels in their novels. Sadly, we'll never know what Austen would have done with this theme.

Published on July 12, 2021 00:00

July 8, 2021

CMP#57 The Dangers of Novels, part 2

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality. Much has been written about Austen.

Click here

for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality. Much has been written about Austen.

Click here

for the first in the series."I own I do not like calling [Camilla] a Novel: it gives so simply the notion of a mere love story, that I recoil a little from it. I mean it to be sketches of Characters & morals, put in action, not a Romance." -- Frances Burney (1795) CMP#57 "It Is Only a Novel" In an earlier post, I looked at a dramatic, romantic, (and oh-so-French) epistolary novel which received a disapproving review from The Quarterly Review. The review began:

“Novels are read so generally and with such avidity by the young of both sexes, that they cannot fail to have a considerable influence on the virtue and happiness of society. Yet their authors do not always appear to be sensible of the serious responsibility attached to their voluntary task.”

The problem with the novel Amelia Mansfield was that it glorified romantic love over everything else in life. The hero and heroine bring tragedy upon themselves and everyone around them -- not behaviour that parents would want their sons and daughters to emulate.

As I discussed in my previous post , concerns about the consequences of reading novels were widespread in Austen's time, so much so that the morality of books was a constant theme in novels and reviews of novels. For example, an early review of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein sniffed that whatever might be the talents of the author, the book "inculcates no lesson of conduct, manners, or morality." The famous eating scene from the 1963

movie version of Tom Jones The Quarterly Review article goes on to mention Henry Fielding in particular of being “notoriously guilty” of impropriety: "other writers also, from whom better things might have been expected, have stained their pages with indelicate details."

Henry Fielding wrote the bawdy comedy The History of Tom Jones (1749). Jane Austen’s brother said of Austen that “She did not rank any work of Fielding quite so high [as she did the novelist Richardson]. Without the slightest affectation she recoiled from every thing gross. Neither nature, wit, nor humour, could make her amends for so very low a scale of morals.”

So Austen agrees with the Quarterly Review according to Henry (and not everybody believes everything Henry had to say about his sister). Although Austen may have turned away from bawdy or vulgar novels, we know for a fact that she laughed at novels with overwrought depictions of virtue and delicacy. In her famous defense of the novel in Northanger Abbey, Austen makes the humorous point that the oh-so-virtuous heroines of novels of the day disdained novel-reading as a past-time: I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding—joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? It's true that novelists often criticized novels -- in their novels! In Paul and Virginia (the French novel Paul et Virginie (1788)), it's the hero who is disgusted; Paul is worried when the girl he loves leaves their tropical paradise to go live with a rich aunt in France. He is afraid she will be corrupted. He “felt disgusted by the perusal of our fashionable novels, filled with licentious manners and axioms" and he assumes that "these romances gave a true picture of society in Europe.”

Paul and Virginia, innocent and uncorrupted by novel-reading In Sarah Burney's Traits of Nature (1812), the hero warns the heroine Adela: “Suffer me to give you, what you so seldom require, a little caution…” He explains that while she was busy, “a servant brought in a parcel of books” from their friend Mrs. Elmer.

Paul and Virginia, innocent and uncorrupted by novel-reading In Sarah Burney's Traits of Nature (1812), the hero warns the heroine Adela: “Suffer me to give you, what you so seldom require, a little caution…” He explains that while she was busy, “a servant brought in a parcel of books” from their friend Mrs. Elmer.“I mechanically opened one of the volumes, and saw the title of a work, which, though written by a female, I am well persuaded you would never wish to read. It is probable that Mrs. Elmer has lent these books without having given herself time to ascertain their character—but she is wrong in having done so—and you, dear Miss Cleveland, will require no further hint, to avoid throwing away your leisure upon such unworthy trash.”

Adela thanks him and promptly wraps up the novels to return them to Mrs. Elmer.

Adela takes a moderate view of novels in general; they are fine for occasional relaxation. But alas, her mother doesn’t exert herself to read anything better than novels: “The indolent and unhappy recluse [Adela’s mother], incapable of bestowing upon superior works the degree of attention, and the spirit of perseverance which they demanded, had long accustomed herself to the exclusive perusal of Novels and Romances. Adela could with pleasure, occasionally in an evening, after a day more usefully spent, have read aloud some of these, and interested herself in the ingenuity of their fictitious perplexities: but, from morning till night, and week after week, to pursue no other species of lecture, was a punishment to her of the most mortifying kind.”

What's worse, her mother's friend frequently visits to read improper fiction and poetry, which makes Adela uncomfortable. Mom becomes defensive: “Adela grieved at these symptoms of diminished affection [from her mother]; but she could not, even in her humblest moments, condemn herself... and was persuaded, that whatever might be the rights and privileges of a parent, it was impossible they should be so unlimited as to authorize the contamination of that mental purity which it was every woman’s duty to preserve unblemished…."

Sorrows of Young Werther Another criticism of novels was that people got so caught up in imaginary drama, they ignored real life. They wept over the plight of Clarissa, but had no compassion for the beggar at the gate. In Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarven, Mrs. St. Austyn is disappointed in her marriage, and resents being “buried in a wilderness from all the joys of society.” Because she has an “inherent weakness of understanding” (ie she is not very bright) she neglects “those resources that can truly enliven solitude; and she knew no gratification superior to what a novel could afford: thus her heart was never wounded with real domestic distress, her sensibility being entirely reserved for the pompous sorrows of favourite valiant heroes and beauteous matchless heroines.” She recoils from the duty of listening to the problems of her tenants: “Does not the parish provide plentifully for the poor?”

Sorrows of Young Werther Another criticism of novels was that people got so caught up in imaginary drama, they ignored real life. They wept over the plight of Clarissa, but had no compassion for the beggar at the gate. In Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarven, Mrs. St. Austyn is disappointed in her marriage, and resents being “buried in a wilderness from all the joys of society.” Because she has an “inherent weakness of understanding” (ie she is not very bright) she neglects “those resources that can truly enliven solitude; and she knew no gratification superior to what a novel could afford: thus her heart was never wounded with real domestic distress, her sensibility being entirely reserved for the pompous sorrows of favourite valiant heroes and beauteous matchless heroines.” She recoils from the duty of listening to the problems of her tenants: “Does not the parish provide plentifully for the poor?” In the Pharos, a collection of essays, the conservative writer Laetitia-Matilda Hawkins includes an essay in letter form from a fictional husband whose wife becomes addicted to novel reading. She grows pale, sick and weak and sunk in “causeless sorrow,” over the imaginary tribulations of the heroines and heroes. “She had no tenderness for the real misfortunes of anybody; had a girl died of a broken heart… perhaps my Mimosa would have wept for her; but when her maid was at the point of death in a fever, her mistress [assumed she didn't need help] such strong vulgar creatures could battle any disease; but however the poor girl died."

Mimosa even dislikes her new-born son because he is healthy and therefore vulgar. “She saw her child at a stated hour once a day, and the whole of her leisure was again devoted to that infernal rhapsody the Sorrows of Werther and half a hundred such books."

The letter concludes, “Surely it is the duty of every moral writer to endeavor the extirpation of this silly, this noxious taste, or we shall, in the next age, not have one woman untainted by the infection. What wives, mothers and daughters we may see, when this rage is at its height, I tremble to think on." While some people were convinced that novels made girls and women like the fictional Mimosa indifferent to real flesh-and-blood people, social scientists now think the opposite is the case: reading novels increased our capacity to feel empathy for others. Stephen Pinker, in The Better Angels of Our Nature, cites Lynn Hunt's theory that when people read epistolary novels and wept over the travails of Clarissa or Pamela, it widened their perspective on life. "Realistic fiction, for its part, may expand readers' circle of empathy by seducing them into thinking and feeling like people very different from themselves." The rise of literacy, the popularity of newspapers, serialized novels and other recreational reading made people more empathetic, not less. The PBS Nova episode: "The Violence Paradox," uses the example of Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), a novel that was tremendously influential in the cause of abolition.

In Austen's time, however, novels provided plenty of fictionalized examples of girls who read too many novels and developed an unrealistic view of life. I'll share some examples in the next post. A Contrary Wind, the first novel in my Mansfield Trilogy, has some "indelicate details," I must confess. But what can a writer do when Henry Crawford is on the loose in London? Click here for more about my books.

Published on July 08, 2021 00:00

July 6, 2021

CMP#56 The Dangers of Reading Novels, part 1