Lona Manning's Blog, page 17

February 14, 2022

CMP#88 Men Do Not Want Silly Wives

"Mr. Palmer's temper might perhaps be a little soured by finding, like many others of his sex, that through some unaccountable bias in favour of beauty, he was the husband of a very silly woman—but she knew that this kind of blunder was too common for any sensible man to be lastingly hurt by it."

"Mr. Palmer's temper might perhaps be a little soured by finding, like many others of his sex, that through some unaccountable bias in favour of beauty, he was the husband of a very silly woman—but she knew that this kind of blunder was too common for any sensible man to be lastingly hurt by it."-- Elinor Dashwood's thoughts in Sense & Sensibility CMP#88 Men of Sense Do Not Want Silly Wives Despite what Jane Austen says in Northanger Abbey about men preferring ignorance, if not outright imbecility in women, Austen pokes gentle fun at ignorant women. There's her description of Catherine Morland's chaperone in Bath: "Mrs. Allen was one of that numerous class of females, whose society can raise no other emotion than surprise at there being any men in the world who could like them well enough to marry them. She had neither beauty, genius, accomplishment, nor manner." And: "the remarks and ejaculations of Mrs. Allen, whose vacancy of mind and incapacity for thinking were such, that as she never talked a great deal, so she could never be entirely silent; and, therefore, while she sat at her work, if she lost her needle or broke her thread, if she heard a carriage in the street, or saw a speck upon her gown, she must observe it aloud, whether there were anyone at leisure to answer her or not." Mr. Knightley and Emma wrangle over Harriet Smith's marital attributes. "Men of sense, whatever you may chuse to say, do not want silly wives," he tells her. Austen also uses Mr. Knightley to refute Emma's claim that men only value beauty and sweet temper in women. Professor John Mullan calls Harriet Smith “the most sublimely stupid human being in the history of world literature." When Mr. Knightley and Emma are arguing after Harriet turns down a marriage proposal from a yeoman farmer, Knightley says that Harriet: "is not a sensible girl, nor a girl of any information. My only scruple in advising the match was on {Robert Martin's] account, as being beneath his deserts, and a bad connexion for him. I felt that, as to fortune, in all probability he might do much better; and that as to a rational companion or useful helpmate, he could not do worse."

Emma counters that "Harriet...is not a clever girl, but she has better sense than you are aware of, and does not deserve to have her understanding spoken of so slightingly..." She goes on to argue that most men are not interested in intellect in their wives anyway, they are attracted to beauty and "sweetness of temper."

“Upon my word, Emma, to hear you abusing the reason you have, is almost enough to make me think so too," [Mr. Knightly retorts.] "Better be without sense, than misapply it as you do."

Fanny Burney satirically tackles this same question in Evelina when Lord Merton declares "a woman wants nothing to recommend her but beauty and good nature." “But I am a sad weak creature—don’t you think I am, my Lord?” [says Lady Louisa after declining an offer to go for a walk]

“O, by no means, (answered he), your Ladyship is merely delicate; --and, devil take me, if ever I had the least passion for an Amazon.”

“I have the honour to be quite of your Lordship’s opinion, (said Mr. Lovel, looking maliciously at Mrs. Selwyn); for I have an insuperable aversion to strength, either of body or mind, in a female.”

“Faith, and so have I, (said Mr. Coverley); for, egad, I’d as soon see a woman chop wood, as to hear her chop logic.”

"So would every man in his senses,” said Lord Merton, “for a woman wants nothing to recommend her but beauty and good-nature; in every thing else she is either impertinent or unnatural. For my part, deuce take me if ever I wish to hear a word of sense from a woman as long as I live!”

“It has always been agreed,” said Mrs. Selwyn, looking round her with the utmost contempt, “that no man ought to be connected with a woman whose understanding is superior to his own. Now I very much fear, that to accommodate all this good company, according to such a rule, would be utterly impracticable….” An Austen heroine might be in error (such as Emma with her propensity for arranging other people's lives), or she might be so timid that no-one knows how bright she is (like young Fanny Price) but Austen heroines are not simpletons. They valued intelligence in others and in themselves.

In Sense & Sensibility, when Elinor tries to resign herself to Edward Ferrars' marriage to Lucy Steel, the first thing she thinks of is that Lucy is intelligent: "Lucy does not want sense, and that is the foundation on which every thing good may be built... he will marry a woman superior in person and understanding to half her sex; and time and habit will teach him to forget that he ever thought another superior to her.” Men of Sense in Other Novels

Other leading men in novels of this time agree with Mr. Knightley--men of sense do not want silly wives. They do not find imbecility or ignorance charming. In The Denial (1790), the hero refuses to marry an heiress--though she is the choice of his father--because of her ignorance, an ignorance he discovers during his first formal visit with her: “Pray, Ma’am, said I,” “which is your favourite amongst the modern Dramatic Authors?”

She fixed her eyes on me, but made no reply.

After a serious pause of some seconds, she answered, “Pray Sir, what are they?”

Amazement struck me almost speechless, when I reflected that a young lady of the age of twenty, with a fortune of fifty or sixty thousand pounds, should betray such total ignorance on a subject which is not unknown even to many children at school.

Despairing of success on a topic of literature, I asked her… what was her opinion of the new dresses exhibited on the last Court-day, as they were detailed to us in the public prints?

I had scarcely finished my question, when her countenance brightened, and she displayed so intimate a knowledge….

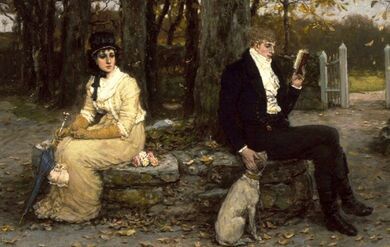

The Waning Honeymoon (detail) In A Tale of Warning, or, The Victims of Indolence (1814), an army officer marries a beautiful girl on short acquaintance only to discover she is poorly educated and only wants to read novels. She thinks that adult married life will be like a romance novel. After the honeymoon, "When her husband ceased to address her like a hero of romance, and wished to converse rationally, she had nothing to say...."

The Waning Honeymoon (detail) In A Tale of Warning, or, The Victims of Indolence (1814), an army officer marries a beautiful girl on short acquaintance only to discover she is poorly educated and only wants to read novels. She thinks that adult married life will be like a romance novel. After the honeymoon, "When her husband ceased to address her like a hero of romance, and wished to converse rationally, she had nothing to say...."In Coraly (1819), Major De Montford finds himself falling for a poor clergyman's daughter, not just because of her beauty but because of her mind: “He could scarcely believe that the lovely unadorned girl whom he met in her morning walks, with a straw hat and linen gown… was the same intelligent being who could in the evening converse with her father, with a clearness of understanding, and a degree of knowledge, which soon accounted to De Montford why that father was so well contented with no other companion.”

In Maria Edgeworth's Belinda (1801), Clarence Hervey realizes that his friend Belinda is the girl he really wants to marry: "In comparison with Belinda, [his ward] Virginia appeared to him but an insipid, though innocent child; the one he found was his equal, the other his inferior; the one he saw could be a companion, a friend to him for life, the other would merely be his pupil, or his plaything. Belinda had cultivated taste, an active understanding, a knowledge of literature, the power and habit of conducting herself; Virginia was ignorant and indolent, she had few ideas, and no wish to extend her knowledge…” This realization dashes cold water on his marriage plans because “a wife without capacity or without literature could never be a companion suited to him, let her beauty or sensibility be ever so exquisite and captivating.”

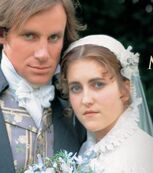

Mr. and Mrs. Palmer, one of Austen's mismatched couples, in Ang Lee's Sense & Sensibility Belinda also gives us a portrait of the ideal wife in the character of Lady Anne Percival, who is well-informed and literate (with the important proviso that she was "without any pedantry or ostentation.") This makes her "the chosen companion of her husband’s understanding, as well as of his heart. He was not obliged to reserve his conversation for friends of his own sex, nor was he forced to seclude himself in the pursuit of any branch of knowledge.”

Mr. and Mrs. Palmer, one of Austen's mismatched couples, in Ang Lee's Sense & Sensibility Belinda also gives us a portrait of the ideal wife in the character of Lady Anne Percival, who is well-informed and literate (with the important proviso that she was "without any pedantry or ostentation.") This makes her "the chosen companion of her husband’s understanding, as well as of his heart. He was not obliged to reserve his conversation for friends of his own sex, nor was he forced to seclude himself in the pursuit of any branch of knowledge.” Charles, the protagonist of the best-selling Coelebs in Search of a Wife, rejects all the shallow London sophisticates he meets in his search. “How dull do we find it, when civility compels us to pass even a day with an illiterate man? Shall we not then delight in the kindred acquirements of a dearer friend? Shall we not rejoice in a companion who has drawn, though less copiously, perhaps, from the same rich sources with ourselves; who can relish the beauty we quote, and trace the allusion at which we hint?... a man of taste who has an ignorant wife, cannot, in her company, think his own thoughts, nor speak his own language... He must be continually lowering and diluting his meaning, in order to make himself intelligible. This he will do for the woman he loves, but in doing it he will not be happy."

Charles warns that other serious consequences arise when a wife can't understand her husband: "She, who cannot be entertained by his conversation, will not be convinced by his reasoning…” This is reminiscent of the passage in Mansfield Park when Sir Thomas attempts to persuade Lady Bertram that it is right and proper for Fanny to go to Portsmouth to see her family. She submits, but she is not convinced: But he was master at Mansfield Park. When he had really resolved on any measure, he could always carry it through; and now by dint of long talking on the subject, explaining and dwelling on the duty of Fanny’s sometimes seeing her family, he did induce his wife to let her go; obtaining it rather from submission, however, than conviction, for Lady Bertram was convinced of very little more than that Sir Thomas thought Fanny ought to go, and therefore that she must. In the calmness of her own dressing-room, in the impartial flow of her own meditations, unbiassed by his bewildering statements, she could not acknowledge any necessity for Fanny’s ever going near a father and mother who had done without her so long, while she was so useful to herself. Mary Crawford must have planted a bee in Fanny's bonnet about the Miss Owens, with whom Edmund spends several weeks when he goes to be ordained as a minister. After he returns, she can't help asking him, “The Miss Owens—you liked them, did not you?”

“Yes, very well." Edmund answers, but he prefers women of superior intellect. The Miss Owens are "[p]leasant, good-humoured, unaffected girls. But I am spoilt, Fanny, for common female society. Good-humoured, unaffected girls will not do for a man who has been used to sensible women. They are two distinct orders of being. You and Miss Crawford have made me too nice.”

Finally, given the disparities in education between boys and girls, marrying someone with whom you can't have a serious, rational conversation must have been the fate of many men in Austen's time, or as she sarcastically put it, "this kind of blunder was too common for any sensible man to be lastingly hurt by it."

A genteel education might be appropriate for the heroine of a novel, but it wasn't appropriate for a girl lower down on the social rung--that only led to trouble. Social class and education is the topic of the next post. In the final volume of my Mansfield Trilogy, we meet Portia Owen, one of the three Owen sisters, who has been carrying a torch for Edmund. Click here for more about my novels.

Podcasters Harriet and Ellen point out that Jane Austen portrayed several less-than-ideal marriages where there was a disparity between the intellect of the husband and wife. Mr. Bennet in Pride & Prejudice, Mr. Palmer in Sense & Sensibility, and Sir Thomas in Mansfield Park all marry women whose understanding and information is much inferior to theirs. Of the three husbands, only Sir Thomas "treats Lady Bertram with absolute respect." Unlike Mr. Bennet and Mr. Palmer, he never belittles her in front of others.

The intellect and discrimination of Austen heroines is such that they tend to be intellectually isolated. When Fanny Price goes in the barouche to Sotherton, "She was not often invited to join in the conversation of the others, nor did she desire it. Her own thoughts and reflections were habitually her best companions." I should have used that quote in my guest post on the "Isolation of the Austen Heroine."

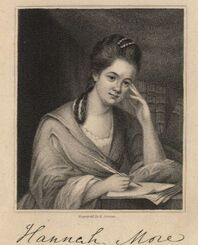

Coelebs in Search of a Wife was written by Hannah More, who is sometimes dismissed today as an reactionary anti-feminist. I think that doesn't do her justice. She and her sisters ran a very successful school for girls in Bristol, and she funded the creation of many schools to teach reading and writing to the poorest of the poor. She was a champion of education, in addition to being a leading light of the abolition movement.

While sweetness of temper might not be enough, it is also highly valued. Austen makes a shrewd authorial observation when she discusses Henry Crawford’s appreciation of Fanny Price’s virtues. "The gentleness, modesty, and sweetness of her character were warmly expatiated on [by Henry to his sister Mary]; that sweetness which makes so essential a part of every woman’s worth in the judgment of man, that though he sometimes loves where it is not, he can never believe it absent."

Harriet Smith and Robert Martin

Harriet Smith and Robert Martin

Published on February 14, 2022 00:00

February 5, 2022

CMP#87 The Misfortune of Knowing Something

"Lady Middleton... did not really like [Elinor and Marianne] at all. [T]hey neither flattered herself nor her children... and because they were fond of reading, she fancied them satirical: perhaps without exactly knowing what it was to be satirical; but that did not signify. It was censure in common use, and easily given."

"Lady Middleton... did not really like [Elinor and Marianne] at all. [T]hey neither flattered herself nor her children... and because they were fond of reading, she fancied them satirical: perhaps without exactly knowing what it was to be satirical; but that did not signify. It was censure in common use, and easily given."-- Sense & Sensibility CMP#87 The Misfortune of Knowing Something

Lydia: vain, ignorant, and idle The topic of female education crops up in each of Jane Austen's novels, either implicitly or explicitly. Lady Catherine enquires into the education of the five Bennet girls and she is shocked to hear they never had a governess. “No governess! How was that possible? Five daughters brought up at home without a governess! I never heard of such a thing."

Lydia: vain, ignorant, and idle The topic of female education crops up in each of Jane Austen's novels, either implicitly or explicitly. Lady Catherine enquires into the education of the five Bennet girls and she is shocked to hear they never had a governess. “No governess! How was that possible? Five daughters brought up at home without a governess! I never heard of such a thing."In Emma, Mr. Knightley tells Emma's former governess: "She will never submit to any thing requiring industry and patience… Emma is spoiled by being the cleverest of her family. At ten years old, she had the misfortune of being able to answer questions which puzzled her sister at seventeen.” In Northanger Abbey, Elinor and Henry Tilney talk with Catherine Morland about reading history books as well as novels.

More broadly, there are references in Austen to girls going astray, either through not learning enough, or from learning the wrong things. Lydia Bennet is "vain, ignorant, idle, and absolutely uncontrolled," and Elizabeth begs her father to step in and correct her. Marianne in Sense & Sensibility is too indulgent of her wild sentimental feelings.

Anne Elliot of Persuasion seems to have her head screwed on straight. Her education furnishes her with quotes from the best poets and essayists for contemplation and consolation. In Mansfield Park, as we've been discussing, there are more explicit remarks from Austen about education than in any other of her novels.

Antoine-laurent Lavoisier And His Wife. She assisted him in his experiments In

my introduction

to this series on the theme of education in Mansfield Park, I opined that the novel’s central theme is the consequences of faulty education which neglects the forming of character. I've quoted some of the many novels of this period which touched on, and even hinged on, the problems arising from faulty or inadequate or misguided education for daughters of the gentry. In the various scenarios of these novels, sometimes a girl's education was neglected, sometimes girls were exposed to dangerous ideas, sometimes they spent hours acquiring showy accomplishments, sometimes they were allowed to be spoiled and vain, sometimes girls learned nothing about practical household management. In other words, education for girls could go wrong in many different ways, and parents had to be careful to steer the correct course.In Waldorf: Or, the Dangers of Philosophy (1798) young Lady Sophia dies as a result of listening to a handsome free-thinker's agnostic rhetoric. The poor girl's “weak brain” is overcome; she goes insane and then dies: “[D]oubts and fears operated with equal violence; ancient prejudice on one hand, and Waldorf’s arguments on the other, distracted her… [and] reduced her to a dreadful decline, wasting sickness preyed on her bloom…Struggling reason was dashed from her throne, and the wretched girl became a victim to the tenets of Waldorf.” The protagonist of Thinks I To Myself (1811) refuses to marry Grizilda Twist, the heiress next door: “Nothing, I think, can ever possibly persuade me to marry a woman so erroneously and so foolishly educated.”In A Winter in London (1806) Mr. Ogilvy thinks girls should not study science. “Have they not music and dancing? Have they not the exercise of fancy and taste in all the articles of dress… besides, I would even allow them a dip into botany and horticulture; --all this may do well enough for amusement. But let me not hear the studies of abstruse sciences called feminine amusements, and the severest labours of human intellect termed pastimes for ladies!”

Antoine-laurent Lavoisier And His Wife. She assisted him in his experiments In

my introduction

to this series on the theme of education in Mansfield Park, I opined that the novel’s central theme is the consequences of faulty education which neglects the forming of character. I've quoted some of the many novels of this period which touched on, and even hinged on, the problems arising from faulty or inadequate or misguided education for daughters of the gentry. In the various scenarios of these novels, sometimes a girl's education was neglected, sometimes girls were exposed to dangerous ideas, sometimes they spent hours acquiring showy accomplishments, sometimes they were allowed to be spoiled and vain, sometimes girls learned nothing about practical household management. In other words, education for girls could go wrong in many different ways, and parents had to be careful to steer the correct course.In Waldorf: Or, the Dangers of Philosophy (1798) young Lady Sophia dies as a result of listening to a handsome free-thinker's agnostic rhetoric. The poor girl's “weak brain” is overcome; she goes insane and then dies: “[D]oubts and fears operated with equal violence; ancient prejudice on one hand, and Waldorf’s arguments on the other, distracted her… [and] reduced her to a dreadful decline, wasting sickness preyed on her bloom…Struggling reason was dashed from her throne, and the wretched girl became a victim to the tenets of Waldorf.” The protagonist of Thinks I To Myself (1811) refuses to marry Grizilda Twist, the heiress next door: “Nothing, I think, can ever possibly persuade me to marry a woman so erroneously and so foolishly educated.”In A Winter in London (1806) Mr. Ogilvy thinks girls should not study science. “Have they not music and dancing? Have they not the exercise of fancy and taste in all the articles of dress… besides, I would even allow them a dip into botany and horticulture; --all this may do well enough for amusement. But let me not hear the studies of abstruse sciences called feminine amusements, and the severest labours of human intellect termed pastimes for ladies!”

The Harp Lesson , Mme. de Genlis and Mlle. d’Orléans Ausschnitt., by Jean-Antoine-Théodore Giroust The Well-Educated Heroine

The Harp Lesson , Mme. de Genlis and Mlle. d’Orléans Ausschnitt., by Jean-Antoine-Théodore Giroust The Well-Educated HeroineIn her introduction to a modern edition of the French novel Adelaide and Theodore, Gillian Dow tells us that the novel illustrates the “responsibility” of “individual families to educate their daughters. A well-educated daughter will, like Adelaide, live a happy and contented life as a devoted wife and mother, a woman who is also the intellectual companion of her husband. A badly educated daughter can only come to ruin and despair.” When Madame de Valcy destroys her fortune and her marriage, the root cause is traced back to her faulty upbringing.

But... isn't it an article of faith among us moderns that under the bad old patriarchy, women were kept in ignorance and discouraged from learning anything? We can't touch on this topic without recalling Austen's famous remark in Northanger Abbey: "A woman especially, if she have the misfortune of knowing anything, should conceal it as well as she can... I will only add, in justice to men, that though to the larger and more trifling part of the sex, imbecility in females is a great enhancement of their personal charms, there is a portion of them too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance."

Despite our views of the past and despite Austen's tongue-in-cheek assertion, the reality is more nuanced. The heroines of sentimental novels were usually portrayed as being intelligent and accomplished, which tells us that some learning, at least, was seen as a desirable thing for genteel females. Often, however, their intelligence and breeding was portrayed as being acquired intuitively. Emmeline, in The Orphan of the Castle, has an “uncommon understanding” and “a kind of intuitive knowledge.” She “comprehended everything with a facility that soon left her instructors behind her.”

In Clarentine , a would-be seducer flatters the heroine that he cannot understand how she came to be so very accomplished: “brought up in such profound retirement; living in a place whence all professional excellence was so far removed [ie far away from the benefit of good masters to teach her] and where, consequently, you had as few means of improvement, as incitements to emulation—how, I beseech you—how did you acquire talents so bewitching, and manners so irresistible? Am I, at last, to believe in all I have heard reported of innate and intuitive endowments? Am I to suppose you were born with all these advantages?”

Austen parodies this type of accomplished heroine In Northanger Abbey, writing that her heroine Catherine Morland “never could learn or understand anything before she was taught; and sometimes not even then, for she was often inattentive, and occasionally stupid.”

"The Sweet Delights of Love" with a scolding wife Austen was not the only author who poked fun at these "pictures of perfection." For example, the young heroine of I'll Consider Of It (1812) could play the pianoforte a little, “but as she did not excel, and could not endure the fatigue and trouble of learning music… she always declared her inability when called upon to perform. She was very fond of working in the garden, digging, hoeing, riding on horseback, feeding poultry, and playing with dogs and cats; she was not fond of working at her needle, and she hated the trouble of writing a letter...”

"The Sweet Delights of Love" with a scolding wife Austen was not the only author who poked fun at these "pictures of perfection." For example, the young heroine of I'll Consider Of It (1812) could play the pianoforte a little, “but as she did not excel, and could not endure the fatigue and trouble of learning music… she always declared her inability when called upon to perform. She was very fond of working in the garden, digging, hoeing, riding on horseback, feeding poultry, and playing with dogs and cats; she was not fond of working at her needle, and she hated the trouble of writing a letter...”This description is not unlike Austen’s portrait of Catherine Morland: "The day which dismissed the music-master was one of the happiest of Catherine’s life... Writing and accounts she was taught by her father; French by her mother: her proficiency in either was not remarkable, and she shirked her lessons in both whenever she could... she was moreover noisy and wild, hated confinement and cleanliness, and loved nothing so well in the world as rolling down the green slope at the back of the house."

These heroines, in other words, are humorously chided for not applying themselves to their studies and tasks.

So plenty of heroines were presented as being reasonably well-educated and intelligent, and as we will see in the next post, there were plenty of heroes who wanted intelligent wives. In the Bristol Heiress: or the Errors of Education (1809) a handsome young clergyman falls for the lovely heiress, who is off to enjoy the season in London. He’s worried that London will corrupt and seduce her. “Must we not then, under such circumstances, tremble for women?” he writes to a friend. “Reason tells us we must. Our education is better than theirs; we are taught to think, they are left only to feel. Why is it not considered as a duty by every parent, to improve the reasoning faculties of the female mind, and thus give more real worth to that sex, whose influence penetrates deeply into almost all the affairs of civilized life?”

Even Thomas Gisborne, author of An Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex, does not object to cleverness in women. He writes that men who don't like being married to clever women are “absurd.” What is more objectionable to men is bad temper. “[I]f strength of understanding in a woman be the source of pride and self-sufficiency; if it renders her manners over-bearing, her temper irritable, her prejudices obstinate; we are not to wonder that its effects are formidable to the other sex… But is arrogance, is impatience of contradiction, is reluctance to discern and acknowledge error, the necessary or the usual fruit of strong sense in the female mind? Assuredly not…. Let talents be graced with simplicity, with good humour, and with feminine modesty; and there will seldom be found a husband whose heart they will not warm with delight.”

What do the novels of the day have to say about the qualities of an ideal wife? Next time. In my Mansfield Trilogy, the recurring characters of Lord and Lady Delingpole are notorious among their friends for their public squabbling. Click here for more about my novels.

Published on February 05, 2022 00:00

February 1, 2022

CMP#86 Brilliant Accomplishments

“A little learning has been deem’d a curse

“A little learning has been deem’d a curseBut sure, accomplish’d smattering is worse!

Modern Accomplishments: or, The Boarding School, a tale in verse by Joseph Snow CMP#86 Brilliant Acquirements We know all about the ideal accomplished woman from the famous dialogue in Chapter 8 of Pride and Prejudice in which Miss Bingley, Mrs. Hurst and Mr. Darcy outline the long list of requisite attributes. In Emma, Mr. Knightley bluntly tells Emma that her neglect of Jane Fairfax was only because Jane was the "really accomplished young woman, which she wanted to be thought herself."

In the previous posts, we've been discussing the theme of education, which was a popular theme for novels in Austen's time, including Austen's own Mansfield Park. Many novels also took up the topic of female accomplishments, which is not surprising considering that genteel young ladies were usually the main characters in these stories. What you might find surprising is the frequent criticisms of a system of education which placed so much emphasis on these "brilliant acquirements." "A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word..." When it comes to the topic of female accomplishments, it is easy to find authors and essayists of Austen's time decrying the entire system of female education which emphasized accomplishments, and I share some examples below. Everyone seems to agree that the practice was an expensive waste of time, was part of a cynical and mercenary husband-hunt, encouraged vanity and discouraged the acquisition of more useful knowledge and life skills. In fact I think it would be more difficult to find an author speaking in favour of girls acquiring and showing off their feminine accomplishments...

Mesdemoiselles Duval by Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou Yes, some authors praised their characters for being highly accomplished. If the heroine of a novel is accomplished, we must understand that it is but the finishing gloss on her excellent education, intelligence and virtues, as with this description from the 1787 novel The Platonic Marriage: “This lovely woman carries in her mind the perpetual sunshine of innocence and virtue, heightened by a piety which appears to be ever habitual, while mistress of every accomplishment which can possibly adorn her sex, she seems unconscious of possessing any…"

Mesdemoiselles Duval by Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou Yes, some authors praised their characters for being highly accomplished. If the heroine of a novel is accomplished, we must understand that it is but the finishing gloss on her excellent education, intelligence and virtues, as with this description from the 1787 novel The Platonic Marriage: “This lovely woman carries in her mind the perpetual sunshine of innocence and virtue, heightened by a piety which appears to be ever habitual, while mistress of every accomplishment which can possibly adorn her sex, she seems unconscious of possessing any…"Jane Austen parodied this sort of description in her hilarious juvenile short story, Love and Freindship. Laura says of herself: "Of every accomplishment accustomary to my sex, I was Mistress... In my Mind, every Virtue that could adorn it was centered; it was the Rendezvous of every good Quality and of every noble sentiment."

The anonymous author of Fanny, or the Deserted Daughter (1792), praises the heroine's "highly accomplished" friend Lady Susan who: "not only played and sung with a grace and excellence peculiar to herself, but she painted in all styles with wonderful success. Her flowers… nearly imitated nature… her landscapes were equally beautiful, and her figures uncommonly elegant and expressive. She excelled in all works of ingenuity; nor did she disdain the inferior knowledge of a woman, plain-work, accounts, and the regulation of a family." But the author also has Lady Susan shrug off her accomplishments "except needle-work" as ultimately useless. "[N]one of these are truly valuable or perhaps at all conducive to the happiness of life...”

Based on her friend's advice, and taking into consideration her own lower status in society, Fanny Vincent decides not to pursue playing and drawing, just as Fanny Price rejects learning these arts in Mansfield Park. Accomplished but not educated

A common criticism of pursuing accomplishments was that girls spent too much time on these showy talents and ignored more academic pursuits. The father in Emily, a Moral Tale, writes disapprovingly of “the eagerness for acquiring accomplishments…. girls are obliged to employ by far too much of their time in attempting to be proficient in dancing, drawing, and more particularly in music.”

In her early juvenile novella Catherine, Austen created a character named Camilla Stanley who ignored "useful knowledge and Mental Improvement" in favour of "learning Drawing, Italian, and Music, more especially the latter, and she now united to these Accomplishments, an Understanding unimproved by reading and a Mind totally devoid either of Taste or Judgement."

The heroine of Coraly [1819] has her priorities straight. Her “ understanding , naturally good, had received every instruction which the most competent tutor could bestow. Her studies had indeed been more deep and solid than those usually pursued by a female... Of what, indeed, are called accomplishments, Coraly was but slightly stored and truth obliges me to confess, that, with the sole exception of music, I do not believe she had any. I am in doubt whether this description will gain her admirers with either sex; for I am convinced, that men hate women who meet them on equal terms and the women are great advocates, in the present day, for accomplishments."

It’s no surprise that evangelical author Hannah More comes out against accomplishments in her writings, or at least, accomplishments in lieu of solid education and moral training. The father in Coelebs in Search of a Wife opines: “the education which now prevails, is a Mohammedan education. It consists entirely in making woman an object of attraction. There are, however, a few reasonable people left, who, while they retain the object, improve upon the plan. They too would make woman attractive; but it is by sedulously laboring to make the understanding, the temper, the mind, and the manners of their daughters, as engaging as these Circassian parents endeavor to make the person."

The reference to "Mohammedan education" is a reflection of the then widely-held belief that Islam denied that women had immortal souls. In the scornful words of Joseph Snow, those who emphasized accomplishments like painting or drawing instead of moral education ought to admit that they were like the Muslims. Oh let us then, disdaining reason's pow'rs,

Confess the creed of Mahomet is ours

That woman bound to this contracted span

Was form’d by nature, as the slave of man;

Forbid to soar beyond her earthly sphere,

No future hope is her’s, no future fear

Her views, her prospects, all are center’d here;

Like flow’rs to blossom, and like flow’rs decay

For her, no “bright reversion” is in store

She blooms, she withers and awakes no more!

(For more about how British people viewed the status of women in their country versus other countries, see here .)

Gillray, Harmony Before Marriage Snow acknowledges that this moral criticism of accomplishments is so common as to be “trite:” “The observation is so trite, as almost to require an apology for its repetition, that the education of women, is more calculated to gratify the sensual indulgencies of the Haram, than to form the “friend, the companion, and the wife."

Gillray, Harmony Before Marriage Snow acknowledges that this moral criticism of accomplishments is so common as to be “trite:” “The observation is so trite, as almost to require an apology for its repetition, that the education of women, is more calculated to gratify the sensual indulgencies of the Haram, than to form the “friend, the companion, and the wife." Similarly, Mr. Stanley, the father in Hannah More's Coelebs in Search of a Wife, opines: “A man of sense, when all goes smoothly, wants to be entertained; under vexation to be soothed; in difficulties to be counselled; in sorrow to be comforted. In a mere artist can he reasonably look for these resources?”

Another often-repeated truism is that girls devoted thousands of hours to acquiring accomplishments, then dropped them after marriage. In Practical Education, Maria Edgeworth writes that despite the “four or five hours a day” that women devote to music before marriage, “What motive has she for perseverance [after marriage]? She is, perhaps, already tired of playing to all her acquaintance… She will prefer the more indolent pleasure of hearing the best music that can be heard for money at public concerts.”

In Emma, Mrs. Elton predicts that she will, like her friends and female relatives, let her musical skills lapse after marriage. “I think, Miss Woodhouse, you and I must establish a musical club,” she proposes to Emma, “Something of that nature would be particularly desirable for me, as an inducement to keep me in practice; for married women, you know—there is a sad story against them, in general. They are but too apt to give up music.” Vanity baits for young ladies and traps for men

Yet another objection to accomplishments was that they encouraged girls to be vain and anxious for admiration and display when they should be blushing and timid. More from Snow's poem:

Gillray's sequel: A woman neglects her housekeeping and her husband is no longer entranced by her singing

Gillray's sequel: A woman neglects her housekeeping and her husband is no longer entranced by her singing Her's is not now, that unaffected mien,

Which shrinks retiring—blushing to be seen;

Is not, that gentle tenderness, which gains

The heart by silent progress, and—retains;

That bloom of mind which to the last endures,

Nor her’s the witching softness that secures.

But ‘tis that dazzling beauty’s bold display

Which rules o’er all with more despotic sway;

Proud and impatient, jealous of its rights,

The admiration which it claims—excites,

A force that seizes, and applause exacts,

Pow’r that subdues—not magic that attracts.

Another author spoke out against the entire marriage market in which young women displayed themselves in hopes of making a brilliant match. In an essay titled “Arabella Single’s history,” Laetitia-Matilda Hawkins features a woman who is sick of the marriage market and the way girls were expected to display themselves. “I was made to squall and thrum the pianoforte to my Lord and Sir Harry, and my good parents congratulated themselves with thinking I was in the way to be talked of.”

On the other side of the coin, Lord Mountmorris, a minor character in Fatherless Fanny, rues the day he married a beautiful girl who "concealed a heart more treacherous than a serpent's." He laments, '[I]f I had not been ensnared by beauty and a vain show of accomplishments, I had not been the miserable wretch you now behold me.”

"Here's harmony! Here's repose!" Mansfield Park and accomplishments

"Here's harmony! Here's repose!" Mansfield Park and accomplishmentsMansfield Park is one of many novels and stories of the period in which the quiet girl of solid intelligence and worth competes against a vivacious, flashy girl with alluring accomplishments. For example, scholar Kenneth Moler has pointed out the many parallels between Mansfield Park and a Maria Edgeworth story titled Madame Panache. In that story, Mr. Mountague is torn between the elegant Lady Augusta and the quietly virtuous Helen Temple. In the same way Edmund Bertram makes excuses for Mary Crawford on account of her upbringing, Mr. Mountague thinks the fact that Lady August “has been educated by a vulgar, silly, conceited French governess... is her misfortune, not her fault."

In Jane Austen’s Art of Allusion, Moler writes that Austen demonstrates “the distinction between accomplishments and more worthy qualities of mind and heart.”

“Fanny, not destined by the Bertrams to be a fine lady, never becomes the accomplished woman that her cousins are… Fanny is established as the antitype to the merely accomplished woman. She lacks her cousins’ polish, but she possesses ‘delicacy of taste, of mind, of feeling.’"

Moler points to the after dinner scene in chapter 11 as an illustration of the false glitter of Mary Crawford's charms: "While Fanny lingers at one side of the room, meditating and moralizing on the beauties of a starlit night, in a fashion of which Hannah More would have heartily approved... Mary is displaying her accomplishments in a 'glee' at the pianoforte. Edmund is at first stationed at Fanny's side, sharing her feelings, but as the glee progresses" Edmund is drawn away from the window, toward Mary at the piano like a moth to a flame. Then, we read: "Fanny sighed alone at the window till scolded away by Mrs. Norris’s threats of catching cold."

Did accomplishments really help to attract or retain male admiration? Mary Crawford’s talents on the harp helped catch Edmund Bertram, but I think he was mostly drawn to her witty mind. Maria Edgeworth skeptically asked: “In enumerating the perfections of his wife, or in retracing the progress of his love, does a man of sense dwell upon his mistress’s skill in drawing, or dancing, or music?” Finally, the rage for accomplishments was seen as permeating downward through society, with harmful results. The father in Emily, a Morale Tale, opines: “I can see no objection to a girl in a genteel situation in life, learning and pursuing any [accomplishment], if she have a genius for it; but in the name of propriety, I wish to protest against that indiscriminate rage for accomplishments, which now pervades all ranks, from the daughter of a duke to the daughter of a farmer; as if female education could not be complete, unless all girls above the degree of a peasant, were educated exactly in the same manner, and the whole harmony and welfare of society depended upon being taught to play upon the piano-forte, and sing Italian songs.” The next two posts will be about what a man of sense wants in a wife, and the right education for your class. In A Contrary Wind, my variation on Mansfield Park, Fanny Price takes up the piano, but for her own pleasure. Click here for more about my novels.

Moler, Kenneth L. Jane Austen's Art of Allusion. University of Nebraska Press, 1968.

Published on February 01, 2022 00:00

January 27, 2022

CMP#85 A Digression on Female Virtue

I'm discussing Mansfield Park and its theme of education. Here is a digression on female virtue as it relates to this theme. The fall of Maria Bertram is a central event in the book, and it comes about because of her pride, her passion, and--as

Austen tells us

--because her moral education had been neglected. "But how little of permanent happiness could belong to a couple who were only brought together because their passions were stronger than their virtue, she could easily conjecture.”

I'm discussing Mansfield Park and its theme of education. Here is a digression on female virtue as it relates to this theme. The fall of Maria Bertram is a central event in the book, and it comes about because of her pride, her passion, and--as

Austen tells us

--because her moral education had been neglected. "But how little of permanent happiness could belong to a couple who were only brought together because their passions were stronger than their virtue, she could easily conjecture.”-- Elizabeth Bennet, thinking about Lydia and Wickham, in Pride & Prejudice

CMP#85 A Digression on Female Virtue

Introduction

IntroductionI've been reading some recent online discussions about a modern-day Henry Crawford called West Elm Caleb , so this seems like a good time to talk about Austen and sexuality.

Jane Austen’s depictions of human nature are timeless, even if the customs and beliefs of the long 18th century are not.

Since Austen's time, economic and social changes have overthrown the centuries-long enforcement of female chastity before marriage. (And yes, Austen knew there was a double standard in play here, and she mentions this in Mansfield Park.)

Not every modern consumer of Jane Austen novels or adaptations understands just how radically our social mores have changed since her time. For the 1995 BBC Pride and Prejudice mini-series, screenwriter Andrew Davies added additional dialogue not found in the novel, to underscore the crisis bought on when Lydia ran off with Wickham. “Oh, Jane,” Elizabeth exclaims to her sister. “Jane, do you not see that more things have been ruined by this business than Lydia’s reputation?” Later, Jane comes to Elizabeth and confirms, “You meant, I suppose, that you and I… and Mary and Kitty… have been tainted by association; that our chances of making a good marriage have been materially damaged by Lydia’s disgrace.” The sisters are not spelling this out for each other's benefit, but for the viewer's.

Henry and Maria, 1999 film version A Licentious Disposition

Henry and Maria, 1999 film version A Licentious DispositionElizabeth and Jane's dilemma is an aspect of the nature-versus-nurture debate as it affected Regency attitudes towards unchaste women. (I am using the value-laden terms of that age while discussing that age.) People in Austen's time debated the influence of nature versus nurture just as we do, though they used different terms.

In prior ages, restraints on female sexual activity protected family fortunes as well as family bloodlines. By "bloodlines," I am referring to the crisis in the Bennet family, the fact that all of the Bennet sisters are "tainted by association" because of Lydia's actions. If Lydia Bennet has loose morals, perhaps all the Bennet sisters do. Perhaps it’s a family predilection. Such a girl wouldn't be welcome as a daughter-in-law. Licentious behavior could be an inherited trait.

This is the question Mr. Collins takes up in his letter to Mr. Bennet after Lydia runs off with Wickham. Was it parental overindulgence that led to Lydia's downfall or was she "naturally bad"?

This is why Austen’s audience wouldn’t have been at all surprised at “the unhappy resemblance between the fate of mother and daughter,” ie., the two Elizas, in Sense & Sensibility. Colonel Brandon’s lost love Eliza commits adultery because of her unhappy marriage. She has a daughter who, in turn, is seduced by Willoughby and is expecting a child. Colonel Brandon laments: "so imperfectly have I discharged my trust!” He blames himself for not being there to safeguard both of the Elizas from falling from virtue.

In Emma, pretty little Harriet Smith can’t expect to marry a member of the gentility because her own parentage is unknown. As well, since her mother bore an out-of-wedlock child, it’s possible that she inherited her mother’s licentious disposition. The best thing for 17-year-old Harriet, as Mr. Knightley tells Emma, is to get her married young, before she encounters the temptations that seduced her mother: “Let her marry Robert Martin, and she is safe, respectable, and happy for ever." Living out in the country as a farmwife under the same roof as her mother and sisters-in-law will keep her away from temptation. Cultural Amnesia?

One can scarcely over-exaggerate the emphasis given to the importance of female chastity in English literature. You can align yourself with those values, or you can rail against the hypocrisy and the double standard, as you please, but being culturally literate means having a grounding in the customs and beliefs of the past.

Our new prosperity and our new attitudes are overthrowing cultural mores that have persisted for thousands of years, mores that were enforced by men and by women. We've now arrived at a culture where some young women think they need to defend their lack of interest in casual sex--to protest that they are not prudes. There is a newly-minted term for their preference: "demisexual," which means "lack of sexual attraction to others without a strong emotional connection."

Did we need a new word for this? It's like the advertisement I just saw for "re-usable tissues," an environmentally-conscious alternative to disposable tissues. Um, we used to call them "handerkchiefs."

I understand that "demisexual" gives a medical/scientific gloss to human behaviour and it is a value-free term. Other terms describing sexual activity are value-laden: chaste, virtuous, maidenly, frigid, prude -- slut, skank, licentious, wanton, promiscuous. But it's still seems bizarre to me to discuss sexual preferences without reference to our past, our culture, or our evolutionary imperatives.

The online articles I've seen on demisexuality do not even mention the historical context of opinions around casual sex. "Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot of information available about what it's like being demisexual," says Web MD, as though being indiscriminate in your choice of sexual partners has always been the default position for females. In fact, for most of human history, including prehistory, obtaining a committed long-term partner was essential for a woman's very survival and that of her children.

But if this is not apparent to a new generation trying to decide if they are allosexual, graysexual, demisexual, or whatever, maybe it would be helpful to spell out some historical and religious context.

Obama might have promised cradle-to-grave security for women, but 18th century politicians didn't

It's Easier to Be Compassionate in a Wealthy Society

Obama might have promised cradle-to-grave security for women, but 18th century politicians didn't

It's Easier to Be Compassionate in a Wealthy Society

Some modern readers are inclined to defend the rebellious Lydia or the charming, cynical Mary Crawford, who calls her brother's affair with a married woman an act of "folly." (In contrast, the heroine we love to love, Elizabeth Bennet, calls Lydia and Wickham's behaviour "infamy.") Today, we are more apt to condemn the historical restrictions on female sexual activity as patriarchal and repressive.

But before blaming everything on the patriarchy, I think we should at least take into consideration that we live in a much more prosperous age, incredibly more prosperous, in fact. Human behaviour is influenced not only by social and cultural factors, but by economic ones as well. Today, single mothers are not sent off to the workhouse or left to beg at the side of the road. Today, a range of social programs make it possible to rear children without a bread-winning father in the house. As well, we have birth control and can dismiss traditional strictures against casual sex as "slut shaming."

In Austen's day, there was no comparable social safety net and no reliable birth control. In Austen's day, sexual activity outside of a committed relationship meant the very real risk of contracting venereal disease, which was difficult and dangerous to cure. It meant social ostracism and for all but a privileged few, utter privation.

I'm not trying to push back against today's social programs, I'm just pointing out that if we judge Regency attitudes in the light of our post-Christian modern attitudes, the conversation isn't very meaningful if we completely untether that discussion from the history of economic and technological change.

Religious and social consequences

Religious and social consequences

Although we live in a post-Christian society, our cultural institutions are based on Christianity and so is our literature. To be educated means having a grounding in that culture. I'm not saying you need to be Christian. Not at all. I am saying that understanding the literature of the past means having some cultural literacy. For example, a culturally literate person understands what the picture at the right refers to.

I'm also not saying that everybody in the past abstained from extra-marital sex. Just because monogamy was the cultural ideal, that doesn't mean that everyone lived up to that ideal. Of course there were hypocrites, and shotgun weddings, and prostitutes, and discreet hospitals for unwed mothers.

Austen disapproved of the rich and titled class who could have affairs and have illegitimate children without facing the economic or social consequences that the lower classes faced. As an example, here's a post by Austenesque author Regina Jaffers concerning a Regency scandal in high life involving double adultery. Austen herself commented on this scandal: "What can be expected from a Paget, born and brought up in the centre of conjugal infidelity and divorces? I will not be interested about Lady Caroline. I abhor all the race of Pagets." She also held the Prince of Wales in utter contempt.

Maria Bertram of Mansfield Park is not a poor peasant girl. She does not face starvation for leaving her marriage, but her father refuses to shelter her under his roof, as she is a bad example and an "insult to the neighbourhood." Taking her back would be giving his "sanction to vice."

Maria's actions put her outside of respectable society, they affect her economically, and finally--and to Austen, most importantly--there are the religious sanctions. Austen is unequivocal that Maria's adulterous affair is not only socially indefensible; it is a sinful act, a "sin of the first magnitude."

It's not for me to defend or critique religious belief, but just for the record, Austen was a sincere and, I think, an orthodox Anglican . This means she believed that sinful behaviour led to consequences on earth and (in the absence of repentance) in the hereafter.

More than 60 years ago, the great Christian apologist CS Lewis understood that the idea of fornication-as-vice was becoming alien to the modern mind: “As long as this sin might socially ruin a girl by making her the mother of a bastard, most men recognized the sin against charity which it involved, and their consciences were often troubled by it. Now that it need have no such consequences, it is not, I think, generally felt to be a sin at all.”

Uncharitable indeed. In 1813, a girl named Fanny Amlett was executed by public hanging for drowning her newborn child. She had been seduced and abandoned by a naval officer.

Today, we're a long way from the world of Mansfield Park. We're a long way from Edmund's horrified reaction to Mary Crawford's cool discussion of adultery: "So voluntarily, so freely, so coolly to canvass it! No reluctance, no horror, no feminine, shall I say, no modest loathings? This is what the world does. For where, Fanny, shall we find a woman whom nature had so richly endowed? Spoilt, spoilt!... oh, Fanny! it was the detection, not the offence, which she reprobated."

Edmund believes that it would only be natural for females to recoil with loathing from the idea of casual sex and infidelity. Not only were Christian women trained to think this way (nurture), these feelings were inherent to their very nature, and Mary's faulty upbringing has spoiled--ruined, destroyed--her character and possibly her soul. To Recap

Jane Austen makes it very clear that Maria Bertram Rushworth's personality (her nature) had a lot to do with her fall from grace. "The high spirit and strong passions of Mrs. Rushworth, especially, were made known to [her father Sir Thomas] only in their sad result." I started this post by saying that Austen's depictions of human nature are timeless. The fact that the behaviour of the man known as West Elm Caleb has stirred up so much indignation is an indication to me that human nature hasn't changed that much. "If your Miss Bertrams do not want to get their hearts broke," Mary Crawford might say today, "let them avoid West Elm Caleb."

Maria Bertram's personality plus her faulty upbringing led to her downfall, and this is the moral lesson of Mansfield Park. I will resume the theme of education in Mansfield Park in the next post. In an earlier post, I wrote about melodramatic novels in which the threat to female virtue is "The Fate Worse Than Death." Colonel Brandon explicitly tells Elinor that the sorrow he experienced when Eliza was married to his brother was nothing compared to how he felt when he heard of her divorce, ie, when he learned that she had committed adultery. It was her fall from virtue which threw him into permanent gloom, not their foiled elopement. "The shock which her marriage had given me,” he continued, in a voice of great agitation, “was of trifling weight—was nothing to what I felt when I heard, about two years afterwards, of her divorce. It was that which threw this gloom,—even now the recollection of what I suffered—”

"Christianity is the assumption that underlies the entire novel," says Karen Swallow Prior of Pride and Prejudice in her new podcast, 'Jane and Jesus.'

Published on January 27, 2022 00:00

January 24, 2022

CMP#84 Cultivating the Mind

"Mrs. Bennet... was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper."

"Mrs. Bennet... was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper."-- Jane Austen describing Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice CMP#84 Cultivating the Mind

In the previous posts, we have looked at the way novelists of Austen's day wrote about the natural dispositions and innate intelligence (or lack thereof) of their characters. Of course, merely being blessed with intelligence, aka "a good understanding," was not sufficient. That understanding had to be enriched and cultivated with knowledge, or “information.”In Pride & Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet has "little information." She's narrow-minded and ignorant.Elizabeth Bennet lists Darcy's "information" as one of his attractive attributes: "She began now to comprehend that he was exactly the man who, in disposition and talents, would most suit her. His understanding and temper, though unlike her own, would have answered all her wishes... and from his judgement, information, and knowledge of the world, she must have received benefit of greater importance." Fanny Price's father "did not want abilities but he had no curiosity, and no information beyond his profession; he read only the newspaper and the navy-list; he talked only of the dockyard."Henry and Mary Crawford are intelligent and well-educated, as Austen makes clear. Mary quotes poetry and invents a satire of that poetry on the spot. Henry converses knowledgably about Shakespeare and even how best to conduct a church service, "shewing it to be a subject on which he had thought before, and thought with judgment." Mary and Henry are lacking, however, in moral judgement, a topic we'll turn to later in this series.

Rousseau's Emile, learning from nature In Austen's time, many novels and stories centered around the problems created when parents neglected their children's education. This theme is found both in adult novels and in works aimed at children.

Rousseau's Emile, learning from nature In Austen's time, many novels and stories centered around the problems created when parents neglected their children's education. This theme is found both in adult novels and in works aimed at children. In Ashton Priory, (1792) “Eliza is endowed with a good natural understanding… but… from the character of her parents…. it can have derived no advantages from cultivation…”In Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnavern , “Frederick and Gertrude St. Austyn joined to good persons understandings which, had they been properly cultivated, might have proved an honour to society; but the follies of their parents slurred the fair tablets which nature had rendered capable of receiving the noblest impression.”In The Brothers, a Novel for Children, (1794) the author contrasts George, “who did not want natural understanding, though it was lost in idleness and neglect” with his brother Harry who “cultivate[s] that understanding which nature had given him.” There was no such thing as universal public school education at this time. Educating children was the responsibility of the parents so it's not surprising that there was much debate about how best to go about it. The French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau was credited with popularizing the idea that children should be allowed to study what interests them, so that their natural curiosity would be awakened.

Colonel Lorton, the father in Emily, a Moral Tale [1809], thinks that is so much hogwash: “He thought that Rousseau’s plan of education, founded as it is upon no good principle, can be conducive to no good end. It shows great ignorance of human nature, because it is evident if a child is left to the unrestrained exercise of its own caprice and passions, it is likely to be more wild and mischievous than any other young animal... [he rejected] without hesitation all such fanciful schemes of education, [and] considered moral discipline as essentially conducive to the right conduct of the human mind…”

It seems Jane Austen also disagrees with Rousseau. When Catherine Morland refers school lessons as "a torment," Henry Tilney responds: “That little boys and girls should be tormented, is what no one at all acquainted with human nature in a civilized state can deny.”

He acknowledges that learning how to read is a boring and laborious task, but “it is very well worth-while to be tormented for two or three years of one’s life, for the sake of being able to read all the rest of it.”

Edward Austen treated his sisters to lunch at an inn when they were at boarding school Boarding Schools

Edward Austen treated his sisters to lunch at an inn when they were at boarding school Boarding SchoolsBoys usually acquired their education at boarding schools, or occasionally with a tutor, as Edward Ferrars does in Sense and Sensibility. When Austen says "the young people were all at home" when young Fanny first came to Mansfield Park, she means that Fanny arrived during school holidays, when the teen-age Tom and Edmund were not away at school.

Emma is glad that the Westons have a daughter because she will not go away: “It would be a great comfort to Mr. Weston… to have his fireside enlivened by the sports and the nonsense, the freaks and the fancies of a child never banished from home.”

Of course, girls sometimes did go to boarding schools, including Cassandra and Jane Austen .In I’ll Consider Of It, a grandfather disputes with his daughter over the education of his granddaughter Emily: “this was a point they never could agree upon—he hated all boarding-schools; but was particularly averse to his grand-daughter being kept any longer, now she was grown a fine tall girl, in a place where he declared she would now learn nothing but deceit and vanity, without any kind of domestic economy.”In The Advantages of Education, the mother rescues her daughter from just such a fashionable boarding school and commences her upon a solid course of reading and moral reflection.In Middlemarch, set in the 1830s, Rosamond Vincy learns how to get in and out of a carriage elegantly at her boarding school. More about “accomplishments” in another post. In Emma, Austen is at pains to contrast Mrs. Goddard’s boarding school with fashionable establishments: "not of a seminary, or an establishment, or any thing which professed, in long sentences of refined nonsense, to combine liberal acquirements with elegant morality, upon new principles and new systems—and where young ladies for enormous pay might be screwed out of health and into vanity—but a real, honest, old-fashioned Boarding-school, where a reasonable quantity of accomplishments were sold at a reasonable price, and where girls might be sent to be out of the way, and scramble themselves into a little education, without any danger of coming back prodigies." Governesses and Home Schooling

"So much mischief may be done by a silly governess in a single quarter of an hour!” exclaims the narrator in Maria Edgeworth's short story, Madame Panache. Well, the governess is French, so what can you expect? In I'll Consider of It, Miss Clarkson's grandfather's friend advises against hiring a French governess. “And do not all young girls show a predilection for reading novels and romances? therefore, to form the mind of her pupil, Madame [the hypothetical French governess] will very good-naturedly, procure for her all the love-breathing, unshackled romances which France has produced; from the Eloise of Rousseau, to the Delphine of Madame de Stael and perhaps will not scruple to put into her hands the more loose and easy writings of the licentious and immoral Louvet!”

“Horrible!” exclaimed the Captain. [the grandfather]

“And yet,” said the Major, “the picture is not too highly coloured; would to Heaven it were! But such are the beings to whom the education of children belonging to the first people in the land is entrusted.” If governesses refrained from corrupting the morals of their charges with French novels, then they might be expected to teach biography and memoir, history, modern languages, astronomy and geography, in addition to enough arithmetic so girls could keep their personal or household accounts. Some girls also studied botany, but other sciences were not considered suitable for females.

The wealthy Bertram family hire Miss Lee to educate Maria and Julia. The Bertram girls have the advantage of "early information." (If not moral instruction), and they are proud of the education they have acquired. A governess is a central character in this children's book about the importance of a thorough, moral education for girls.

I quoted this passage last month in a book review but it is so apropos I'll quote it again here: In A Winter in London, two old curmudgeons talk about the new-fangled craze for female education:

“I don’t approve of the present system, of making prattling philosophers in petticoats.” [says Mr. Ogilvy] I see no good that is to result to society from having our wives or daughters discharging electric or Galvanic batteries at our heads, or of converting our cookmaids into chemical analysers of smoke and steam.”

“But are not the scientific pursuits of the present day at least as beneficial to society as the old amusements of working carpets and chair bottoms?” doctor Hoare asks, but he is just kidding. He concurs that “it is impossible there should be a difference of opinion” on the subject of females studying the sciences.

Latin and Greek

Latin and GreekStudying Latin and Greek was controversial for women. In Coelebs in Search of a Wife, it accidentally slips out that Lucilla, the candidate for wifehood, has been studying Latin. She blushes and leaves the room. Her father Mr. Stanley approves of her modesty, for “a discreet woman will never produce in company” her knowledge of “a learned language” as opposed to “those acquirements which are always in exhibition” such as music and drawing.

Ladies who made it known they could speak Latin and Greek were derided as female pedants . For boys, however, education in those days strongly emphasized Latin. Our Austen heroes with the possible exception of Captain Wentworth (who might have gone to sea as a boy, not to university) would have been able to read Latin and to quote and refer to classical literature in Latin. Our clergyman heroes, Edmund Bertram, Edward Ferrars, and Henry Tilney, would have also studied Greek.

Of course, not everybody profited by their classical education. We can't imagine Mr. Rushworth quoting Cicero. The long-standing joke was that the sum total of classical knowledge schoolboys took away was the answer to the question , "Who dragged whom around the wall of what?"

Because Jane Austen's father kept a small school in his home, I feel certain young Jane would have overheard the lessons which were probably held six mornings a week. She would have heard the daily rhythmic chanting of the boys construing their Latin grammar.

Dr. Helena Kelly points out that Austen "certainly knew a little Latin. One of the notebooks in which her youthful writing is preserved is inscribed, in Latin, “Ex doni mei patris” (Given to me by my father), and she includes Latin phrases in her letters on more than one occasion."

However, Austen disclaimed all knowledge of the higher branches of education when she turned down a suggestion that she write a serious novel about a clergyman: "Such a man's conversation must at times be on subjects of science and philosophy, of which I know nothing; or at least be occasionally abundant in quotations and allusions which a woman who, like me, knows only her own mother-tongue, and has read little in that, would be totally without the power of giving. A classical education, or at any rate a very extensive acquaintance with English literature, ancient and modern, appears to me quite indispensable for the person who would do any justice to your clergyman; and I think I may boast myself to be, with all possible vanity, the most unlearned and uninformed female who ever dared to be an authoress."

Educational fads and fashions

Educational fads and fashions The Regency period saw many books published for home educational use. Mary Shelley's father, the philosopher William Godwin, operated a publishing business and bookstore with his second wife, specializing in juvenile literature such as Charles and Mary Lamb's Tales from Shakespeare. Moralizing novels, some of which are quoted in this series, were judged safer for children than fantasies and fairy tales. In Traits of Nature, Young Christina Cleveland remarks to her cousin Adela, "fairy-tales are forbidden pleasures in all modern school-rooms. Mrs. Barbauld, and Mrs. Trimmer, and Miss Edgeworth, and a hundred others, have written good books for children, which have thrown poor Mother Goose, and the Arabian Nights, quite out of favour;—at least, with papas and mamas." Finally, I'll quote a passage from Coelebs in Search of a Wife [1809], which illustrates what many people thought about educational fads for girls, but also so we can appreciate the difference between a didactic novel and the more natural, skillful, and witty way Austen treats this same subject in Mansfield Park. In Coelebs, a girl named Amelia Rattle (hint, hint) is brought into the novel just to give this speech. She plays no role in the plot: “'I have not been idle, if I must speak the truth,' [says Amelia]. 'One has so many things to learn, you know. I have gone on with my French and Italian of course, and I am beginning German. Then comes my drawing-master; he teaches me to paint flowers and shells, and to draw ruins and buildings, and to take views.' [She adds that he “begins” projects for her, which will then be passed off as her own work, of course.]

'And then,' pursued the young prattle, 'I learn varnishing, and gilding, and japaning. And next winter I shall learn modelling, and etching, and mezzotinto and aquatints…Then I have a dancing-master, who teaches me the Scotch and Irish steps, and another who teachers me attitudes, and I shall soon learn the waltz… Then I have a singing-master, and another who teaches me the harp, and another for the piano-forte. And what little time I can spare from these principal things, I give by odd minutes to ancient and modern history, and geography, and astronomy, and grammar, and botany. Then I attend lectures on chemistry, and experimental philosophy, for as I am not yet come out, I have not much to do in the evening… as soon as I come out, I shall give it all up, except music and dancing.'

All this time Lucilla sat listening with a smile, behind the complacency of which she tried to conceal her astonishment.” This leads us, of course, to a discussion of "accomplishments." Jane Austen and her contemporaries also used the word "information" as we use it today. "Miss Bertram could now speak with decided information of what she had known nothing about when Mr. Rushworth had asked her opinion; and her spirits were in as happy a flutter as vanity and pride could furnish, when they drove up to the spacious stone steps before the principal entrance."

Jean-Jacques Rousseau may hold an important place in the history of pedagogical theory, but he himself had no experience with children. As Paul Johnson relates in Intellectuals, "it comes as a sickening shock to discover what Rousseau did to his own children." Rousseau abandoned each of his five children by his common-law wife at a foundling home, where he knew they would most likely die of malnutrition, disease or neglect. "How could I achieve the tranquility of mind necessary for my work, [if] my garret [were] filled with domestic cares and the noise of children?"

Fanny Price's brother John and his friend Prudence pay a visit to the Juvenile Library in A Different Kind of Woman, the third volume of my Mansfield Trilogy. Click here for more about my novels.

Published on January 24, 2022 00:00

January 17, 2022

CMP#83 Apprehension and Discernment

"He knew her to be clever, to have a quick apprehension as well as good sense.”

"He knew her to be clever, to have a quick apprehension as well as good sense.”-- Edmund's opinion of Fanny Price in Mansfield Park

Girl Reading (detail) Charles Edward Perugini

Other Mental Qualities: Apprehension, Penetration and Discernment

Girl Reading (detail) Charles Edward Perugini

Other Mental Qualities: Apprehension, Penetration and Discernment

In the previous posts, I've been discussing the way that Austen and other writers of the period described people's personalities and intelligence , as part of my discussion of the themes of Mansfield Park. The ability to learn quickly, what we might describe as "cleverness," was referred to as "apprehension."

"My father," explains the main character in Samuel Johnson's The History of Rasselas, "originally intended that I should have no other education than such as might qualify me for commerce; and discovering in me great strength of memory, and quickness of apprehension, often declared his hope that I should be some time the richest man in Abyssinia."

A biography of the poet Richard Savage says "His judgment was accurate, his apprehension quick, and his memory so tenacious, that he was frequently observed to know what he had learned from others, in a short time, better than those by whom he was informed."

In Constantia Neville, or the West Indian [1800], Miss Neville avoids showing up her superior knowledge when she talks to Mrs. Rochford, aware of that other lady's "dullness of apprehension."

Mrs. Smith has a lot of surprises in store for Anne Elliot Penetration

Mrs. Smith has a lot of surprises in store for Anne Elliot Penetration"Penetration" was another way to refer to cleverness, or to being perceptive. In Mystery and Confidence (1814) "A slight trace of anxiety passed over [Ellen's] countenance, which St. Aubyn perceiving, for in quickness of apprehension and ready penetration no one ever exceeded him, he said: 'Fear nothing, my love....'"

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot muses that Mr. Elliot doesn't know Elizabeth very well, so he might be thinking of courting her: "Elizabeth was certainly very handsome, with well-bred, elegant manners, and her character might never have been penetrated by Mr. Elliot, knowing her but in public, and when very young himself. How her temper and understanding might bear the investigation of his present keener time of life was another concern ..."

Later, Anne is astonished and confused by her friend Mrs. Smith's penetration when she tells Anne: "Your countenance perfectly informs me that you were in company last night with the person whom you think the most agreeable in the world, the person who interests you at this present time more than all the rest of the world put together."

And, there is The Letter from Wentworth to Anne: "Can you fail to have understood my wishes? I had not waited even these ten days, could I have read your feelings, as I think you must have penetrated mine."

In a comic passage in Northanger Abbey, Isabella Thorpe pretends that Catherine Morland has known all along that she, Isabella, is in love with Catherine's brother. “Yes, my dear Catherine, it is so indeed; your penetration has not deceived you. Oh! That arch eye of yours! It sees through everything.”

Catherine replied only by a look of wondering ignorance.

“Nay, my beloved, sweetest friend,” continued the other, “compose yourself. I am amazingly agitated, as you perceive. Let us sit down and talk in comfort. Well, and so you guessed it the moment you had my note? Sly creature!... Your brother is the most charming of men...”

Catherine’s understanding began to awake: an idea of the truth suddenly darted into her mind...”

Read the Room!

Read the Room!

Now let's look at the apprehension, penetration, discernment and judgement of the residents of Mansfield Park.

Tom Bertram's guest Mr. Yates doesn't pick up on the fact that Sir Thomas is not happy about coming home from Antigua to find an amateur theatre in his billiard room. "Mr. Yates, without discernment to catch Sir Thomas’s meaning... would keep him on the topic of the theatre, would torment him with questions and remarks relative to it...."

Read the room Mr. Yates! as we would say today. Mr. Yates talks on and on, "relating everything with so blind an interest as made him not only totally unconscious of the uneasy movements of many of his friends as they sat, the change of countenance, the fidget, the hem! of unquietness, but prevented him even from seeing the expression of the face on which his own eyes were fixed..."

Of course, Mr. Yates is not the only oblivious character in Mansfield Park, not by a long shot. In an editorial aside Austen informs her readers that "Mrs. Norris had not discernment enough to perceive, either now, or at any other time, to what degree [Sir Thomas] thought well of his niece, or how very far he was from wishing to have his own children’s merits set off by the depreciation of hers." At the end of the novel, she tells us bluntly that Mrs. Norris has "no judgment," though she has always thought of herself as being wise and discerning.

Sir Thomas is described by Fanny as "discerning," which certainly isn't true so far as his children are concerned. But he is discerning enough in general that Austen has to get him out of the way for a significant portion of the novel, so she sends him to the West Indies.