Lona Manning's Blog, page 15

June 12, 2022

CMP#106 Julia Marchmont, the Suffering Heroine

“Have you among your story books Mrs. Woodlands Tales, let me my dear child recommend them to you.”

“Have you among your story books Mrs. Woodlands Tales, let me my dear child recommend them to you.”-- Southern gentlewoman Mary Telfair, in a letter to a friend, 1827 CMP#106 Julia Marchmont, the Suffering Heroine

Family harmony In the

previous posts

I introduced a discussion about the “bear and forbear” heroine, a girl who endures mistreatment without resentment. However far such portraits of girls strayed from reality, there is no doubt that heroines of this sort were held up as models to emulate. Bear and Forbear or, the history of Julia Marchmont (1809), shows us just how far an author can carry the moral lesson for young people--to the brink of death, in fact.

Family harmony In the

previous posts

I introduced a discussion about the “bear and forbear” heroine, a girl who endures mistreatment without resentment. However far such portraits of girls strayed from reality, there is no doubt that heroines of this sort were held up as models to emulate. Bear and Forbear or, the history of Julia Marchmont (1809), shows us just how far an author can carry the moral lesson for young people--to the brink of death, in fact. This book, and others, argued that being yielding and sweet-tempered is not only the best course for society and for your family, but also for you. Conduct books suggested that you would have more influence over your husband if you were sweet-tempered and obliging, not cross and demanding. In the opening of Bear and Forbear, we have this advice: “Nothing is more conducive to female happiness, or more certain to insure the affection of those with whom we live, than a yielding forbearing temper. It not only produces that harmony which is so desirable in families, but teaches fortitude and patience; two qualities which cannot be too highly estimated, and which young women cannot too assiduously cultivate.”

Speaking of family harmony, this is the reason Edmund Bertram gives for giving up his attempts to persuade his brother and sisters to abandon the private theatricals: “Family squabbling is the greatest evil of all, and we had better do anything than be altogether by the ears.” We might object that continually biting one’s tongue, or suffering, as Fanny Price does, under the tongue lashes of her Aunt Norris, is not exactly what anyone should call family “harmony."...

Fanny Arlaud, Portrait of a Young Girl Furthermore, the didactic novels stress that these traits of forbearance should be a matter of principle and the result of conscious conviction.

Fanny Arlaud, Portrait of a Young Girl Furthermore, the didactic novels stress that these traits of forbearance should be a matter of principle and the result of conscious conviction.In The Denial, or the Happy Retreat (1792), the tyrannical Lord Wilton is impatient and dismissive of his wife and their marriage is loveless. Lady Wilton “for many years, under patience and humility, [bore] with meekness the insulting tone of obstinacy… She vainly hoped, that such gentle and endearing behaviour would in time soften and meliorate a disposition long known to be callous and obdurate… She has hitherto failed; yet she still perseveres, from her high sense of duty… This does not proceed from passiveness, timidity, want of resolution, or defect of understanding, but from the purest of all motives, a wish to preserve domestic peace and tranquility.”

Likewise, in Bear and Forbear, we are told that “Julia Marchmont… had acquired what is most engaging in woman, a yielding temper and a spirit of forbearance, which being regulated by an excellent understanding, did not degenerate into weakness.”

Julia comes from a respectable middle-class family. The focus in the opening section of the book is on the education Julia receives from her parents. Unlike the Bertram girls in Mansfield Park, she receives a good moral education and learns habits of self-command. The author contrasts her with her spoilt little cousin Maude and Maude's weak and indulgent mother. Maude, weakened by the rich and improper diet she's allowed to eat, dies of the measles.

At eighteen, Julia is accomplished, sweet-tempered, vivacious, and intelligent. She has the good luck to captivate a baronet, Sir Owen Fitz-Ellard, who, we are told, is intelligent and benevolent, though "of an impatient temper."

As she begins her married life, Julia’s father advises her: “The wife who values her husband’s or her own happiness will always keep this in her recollection; she will bear and forbear! And such a wife acquires a lasting empire over the mind of her husband, and sets a bright example to her sex.” Dad adds that Sir Owen “is an excellent man” who “has an irascible, but not a stern or despotic temper. Soothe his moments of impatience with that gentleness so lovely in your sex, particularly in a wife….”

After the honeymoon, Sir Owen’s imperious old grandmother summons him to keep her company at “Lewellen Castle” in Wales. Just as an aside here, in novels of the long eighteenth century, Wales is an exotic destination and its inhabitants are strange and uncouth. I think the reason the author chose Wales for the story is to set up a scenario where Julia goes far, far, away from her parents to the back of beyond. This isolation helps to set up the story of her sufferings.

Exotic, foreign, Wales Spoilers Follow

Exotic, foreign, Wales Spoilers FollowGrandma is something of a Lady Catherine De Burgh. She thinks her grandson married beneath him, and it’s uphill work for Julia to win the old lady over: “the dowager viewed her with ill-will, amounting almost to dislike... she must expect to meet continual mortification while she remained at Lewellen Castle.” But Julia resolves not to complain to her husband or to her own parents by letter, and behaves respectfully toward the old lady. Julia did not “wish to create the slightest dispute or coldness between her beloved husband and his family.”

Julia is gradually winning over the dowager’s good opinion, when some cynical snobbish, cousins of Sir Owen, a brother and sister, come for a long visit. They are curious about the new bride: Sir Tudor is offended that Sir Owen did not marry his sister Jessica: “What! prefer a girl who in beauty, birth, and even fortune, was inferior to his sister? Prefer the alliance of plain Mr. Marchmont to that of Sir Tudor Fitz-Ellard his own relation, and whose family was at least equally ancient? The insult was scarcely to be forgiven! The girl must have been an artful creature, who had inveigled the baronet into marriage; and she would soon, no doubt, give him cause to repent.”

The cousinly brother and sister succeed in planting suspicions into the mind of Sir Owen (because he is an idiot.) Sir Owen accuses her of not liking his relatives, but she does not explain that the reason she avoids their company is because they insult her whenever they get the chance. She meekly takes his criticism and promises to “pay them more attention than ever she had done.”

Julia “suffered cruelly in secret” but “very prudently forbore to confide her sorrows even to her beloved parents; for they had taught her to feel, that nothing is so odious in a wife, as to make her domestic vexations or the faults of her husband the theme of complaint; nor is any thing so destructive to her happiness.”

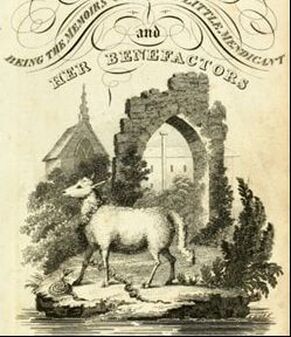

Bear and Forbear, frontispiece We learn that Sir Owen had a first love, Agnes, who died at 17, and he has a little toothpick case she gave him. One day, he realizes he can't find it and the cousins maliciously suggest that Julia has stolen it.

Bear and Forbear, frontispiece We learn that Sir Owen had a first love, Agnes, who died at 17, and he has a little toothpick case she gave him. One day, he realizes he can't find it and the cousins maliciously suggest that Julia has stolen it.“I declare, cousin,” said Jessica, affecting to smile, “If Lady Fitz-Owen were not so sensible a woman, and so sweet tempered, I should really be inclined to think she was jealous, and had purposely hid the toothpick case, to punish you for being so attached to the memory of the amiable Agnes.”

Sir Owen (who, let's remember, is an idiot and a jerk), “began to think that partiality had hitherto made him blind to the faults of his wife… he now believed that she had taken the toothpick-case. That meekness and yielding sweetness which he had before so warmly admired in Julia, now, through the liberal insinuations of Sir Tudor, appeared to him suspicious, and to be the result of art.”

Sir Owen angrily accuses Julia of being manipulative. “Facts speak for themselves, madam; whether you are jealous or not, you have behaved so as to make yourself and me ridiculous. You must have taken the trinket… You have, with all your affected meekness, played the tyrant too long; you have turned me which way you pleased; but my eyes are now opened…”

In high dudgeon, Sir Owen takes himself off to London to look after some business, leaving Julia with his horrible relatives. “[A]ll she could do would be to suffer his injustice with mild and silent resignation.” She still does not complain to anyone, and faithfully nurses Jessica when she catches a slight cold.

Jessica and Sir Tudor finally leave. The author continues to recommend and praise Julia’s meekness even though the miseries she endured “preyed upon her health” and “threw poor Julia into a fit of illness, which only a strong mind and good constitution could have undergone without the loss of life.”

The old dowager is about to send for a nurse to look after Julia, when Hannah, a faithful servant-girl, cautions her that Julia is raving in her delirium about “Sir Tudor, and Miss Jessica, and my master, and a toothpick-case… that it would break your ladyship’s heart to hear. I would not have mentioned this to any living soul, had not your ladyship wanted to send for strangers, and so I thought I had better tell your ladyship the truth, than suffer the concerns of my dear lady and Sir Owen to be talked of by every body.” In this way the grandmother begins to learn how Julia has been suffering.

Meanwhile, in London, a faithful old servant comes to tell Sir Owen, you know that toothpick-case you were looking for? I found it here in your writing desk.

Meanwhile, in London, a faithful old servant comes to tell Sir Owen, you know that toothpick-case you were looking for? I found it here in your writing desk.“Good god!” exclaimed the baronet… “I now remember… Rash fool that I was!” He promptly blames his cousins, not himself: “why did Sir Tudor and his sister make me believe that my wife must have it, when they saw how angry it made me? Why did they interfere to do mischief?”

“Why, if I might be so bold as to speak without giving offence, I could tell your Honour something that would surprise you, Sir…” says “honest Gregory,” who forbears to add, and what would have been obvious to a five-year-old.

The baronet is dumbfounded when the truth is revealed and sends an abject letter of apology to Wales, but Julia, being on the brink of death, is too sick to read it. When she starts to recover, the dowager, who is now perfectly convinced that Julia is a wonderful girl, writes to Sir Owen: “Your amiable Julia… is now informed of your lively repentance…. and she begs me to assure you, that she has not a moment ceased to love and esteem [you]… the only request she has to make is, that all past troubles may be buried in oblivion, and every body forgiven. There, I must own, I dissent from her.”

Sir Owen gets trouble-making Sir Tudor a government posting out of the country and Jessica finds a husband—although, the narrator assures us, “they were not truly happy.”

So the moral of the story is, bear and forbear even if it almost kills you. Who would write or publish such an over-the-top story? The answer might surprise you. Next post.

Yes, Jane Austen also made use of a toothpick case in Sense & Sensibility, in a comic sequence.

Yes, Jane Austen also made use of a toothpick case in Sense & Sensibility, in a comic sequence.The denouement of Bear and Forebear relies upon disclosures made by servants. Servants tend to play lesser roles in Austen, and people who chat with or about servants are vulgar characters in Austen, as discussed in this earlier series of posts.

Franco Moretti in his Atlas of the European Novel (1998) maps the locations of all the scenes in Austen's novels (apart from mentions of places like Ireland or Antigua) and shows that she never strayed very far: “a pattern does indeed emerge here of exclusion, first of all. No Ireland, no Scotland no Wales; no Cornwall. No ‘Celtic fringe,’… only England… And not even all of England: Lancashire, the North, the industrial revolution—all missing.”

Young men were also advised to bear and forbear, as in this 1870 Christian novel: Bear and Forebear, or, the Young Skipper of Lake Ucayga.

Published on June 12, 2022 00:00

June 8, 2022

CMP#105 The Bear and Forbear Heroine, pt 2

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. When I say "my take," I very much doubt that I could find anything new or different to say about Austen, not after her admirers have written so much. But I am not trying to be new, rather I am pushing back at post-modern portrayals of Austen as a radical feminist. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. When I say "my take," I very much doubt that I could find anything new or different to say about Austen, not after her admirers have written so much. But I am not trying to be new, rather I am pushing back at post-modern portrayals of Austen as a radical feminist. Click here for the first in the series.CMP#105 "Lady--Wife--Mother!" To Bear and Forbear

Helen Burns in Jane Eyre: "the Bible bids us return good for evil." In my previous post, I introduced a type of character I called the "bear and forbear" heroine. This is a girl or woman who endures hardship and suffering and is tolerant and forgiving--not out of weakness, but out of personal conviction. I mentioned the medieval character of Patient Griselda as an archetype of this character. We meet some Griseldesque (if that's a word) wives as well in the literature of the 18th and 19th century. Both male and female authors created Griselda-like characters.

Helen Burns in Jane Eyre: "the Bible bids us return good for evil." In my previous post, I introduced a type of character I called the "bear and forbear" heroine. This is a girl or woman who endures hardship and suffering and is tolerant and forgiving--not out of weakness, but out of personal conviction. I mentioned the medieval character of Patient Griselda as an archetype of this character. We meet some Griseldesque (if that's a word) wives as well in the literature of the 18th and 19th century. Both male and female authors created Griselda-like characters.In Jane Eyre, the rebellious main character is contrasted with the gentle and forbearing Helen Burns. Jane listens to what Helen tells her about turning the other cheek, she acknowledges Helen's goodness, but she cannot be another Helen in meekness. Helen is supposedly modelled on Maria Brontë, the oldest of the five Brontë sisters.

In The Denial, or the Happy Retreat (1792), by the Rev. James Thomson. Lady Wilton's husband was chosen for her by her parents. Lord Wilton has not treated her well; in fact he is a tyrant to her and their children. She carries out her wifely duties and carries herself so as to be above reproach. She advises her daughter to study to please her husband and "even if you do not meet with a reciprocation of tendernesses and good offices, remember, and let me caution you, that it is still your indispensable duty to act your part with cheerfulness and good nature; for the errors of the husband are no precedents to the wife; and retaliation will certainly render you contemptible here and miserable hereafter.” ... In Anna, or, the Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1785), the mother of the hero bears with a profligate husband who spends the family fortune and neglects her in favour of his mistresses. He gives her venereal disease. The narrator explains, “Mrs. Herbert, as I informed my reader, had long lived on terms of the most miserable distrust of a husband she tenderly and passionately loved; --Still he offended, and still he was forgiven; till the consequence of his indelicate connections had injured her health –from that period she declined his bed; and his conduct since had been so little adapted to heal the shock her virtuous love for him had received, that she had gradually felt herself superior to the man who was continually wounding her pride and affection.”

Eventually, Mr. Herbert is arrested for debt and thrown into prison. Her grown children plan to return to Wales, but she insists on staying in London: “Mrs. Herbert declined accompanying them; she had hitherto fulfilled, to the utmost of her power, her conjugal duties, now could she now, in the hour of distress, notwithstanding his libertine conduct, prevail on herself to desert her husband. He had forbid her coming to him, but she chose to stay within reach of serving the father of her children.”

Theda Bara as the wife who didn't bear and forbear (1916 movie) The Victorian potboiler East Lynne (1861) was a tremendously popular novel and stage play which survived well into the 20th century. It involves a wife who leaves her husband then bitterly regrets it. The narrator exhorts the reader: "Oh, reader, believe me! Lady—wife—mother! should you ever be tempted to abandon your home… whatever trials may be the lot of your married life, though they may magnify themselves to your crushed spirit as beyond the nature, the endurance of woman to bear, resolve to bear them; fall down upon your knees, and pray to be enabled to bear them—pray for patience—pray for strength to resist the demon that would tempt you to escape bear unto death, rather than forfeit your fair name and your good conscience; for be assured that the alternative, if you do rush on to it, will be found worse than death.”

Theda Bara as the wife who didn't bear and forbear (1916 movie) The Victorian potboiler East Lynne (1861) was a tremendously popular novel and stage play which survived well into the 20th century. It involves a wife who leaves her husband then bitterly regrets it. The narrator exhorts the reader: "Oh, reader, believe me! Lady—wife—mother! should you ever be tempted to abandon your home… whatever trials may be the lot of your married life, though they may magnify themselves to your crushed spirit as beyond the nature, the endurance of woman to bear, resolve to bear them; fall down upon your knees, and pray to be enabled to bear them—pray for patience—pray for strength to resist the demon that would tempt you to escape bear unto death, rather than forfeit your fair name and your good conscience; for be assured that the alternative, if you do rush on to it, will be found worse than death.”

Lady Ann welcomes her husband's daughter by a first marriage Although Mr. Palmer of Sense & Sensibility is by no means so reprehensible a husband, we are reminded that the same scenario can be played for comedy as well as tragedy. Mr. Palmer is rude and dismissive of his wife, and her response is to "laugh heartily" when her mother reminds him that he is married for life. "The studied indifference and the discontent of her husband gave [Mrs. Palmer] no pain; and when he scolded or abused her, she was highly diverted."

Lady Ann welcomes her husband's daughter by a first marriage Although Mr. Palmer of Sense & Sensibility is by no means so reprehensible a husband, we are reminded that the same scenario can be played for comedy as well as tragedy. Mr. Palmer is rude and dismissive of his wife, and her response is to "laugh heartily" when her mother reminds him that he is married for life. "The studied indifference and the discontent of her husband gave [Mrs. Palmer] no pain; and when he scolded or abused her, she was highly diverted."When I read the play The Deserted Daughter (1795), I was honestly confused as to whether I was reading tragedy or comedy. The injured wife, Lady Ann, was so over-the-top, I thought her scenes were supposed to be played for laughs. Then I read the contemporary reviews and saw that, no, while her servant is a stock comic character, the wife is not a comic character.

Lady Ann swans around making speeches like: “What is the test of an affectionate wife? It is that, being wronged, her love remains undiminished, having cause of complaint, she scorns to complain, convinced that any misery is more welcome than the possibility of becoming the torment of her bosom’s Lord!”

Her servant Mrs. Sarsnet snarls: “He is a barbarian Turk! And so I as good as told him.”

Mrs. Sarsnet intercepts a letter to Lady Ann’s husband, but Lady Ann returns it to him without looking at it. “The heart, which I cannot secure by affection, I will not alienate by suspecting,” she tells him.

Mordent: Pshaw! Meekness is but mockery, forbearance insult.

Lady Ann: How shall I behave? Which way frame my words and looks, so as not to offend? Would I could discover?...

Mordent: Ay, ay! Patience on a monument…

Lady Ann also offers to turn over her marriage settlements to her husband to help him out of his financial difficulties. In the end, they are reconciled and Mr. Mordent admits: “Let me do her justice; She is a miracle of forbearance. I have hated and spurned at the kindness I did not deserve. Her perseverance in good has been my astonishment and my torture.”

Mrs. Pope, the actress who originated the role, was known for her Shakespearean and tragic parts, so I guess she played it straight. Adding to my confusion is that in the afterward (a comic soliloquy given at the end of a play), Mrs. Pope comes out and winks at the audience: yeah, we know that this is completely unrealistic... And now, thrice gentle friends, our plotting ended,

We hope you’re pleased –at least, not much offended.

Surely, you’ll own it was a little moving

To see a modern wife so very loving!

Who deems the marriage vow a thing expedient,

And is at once meek, faithful, and obedient.

Such whims were common in the Golden Age

But still they may be met with –on the Stage

But grant they now are false, past contradiction,

We hope they yet may be endured—in fiction

Mrs. Pope emoting in The Gamester So, even though not everyone seriously supposedly that all wives should "bear and forbear," the fact is that exaltedly virtuous heroines like Lady Ann were mainstream figures in plays and literature during the long 18th century. Another example--aimed at young readers--in the next post.

Mrs. Pope emoting in The Gamester So, even though not everyone seriously supposedly that all wives should "bear and forbear," the fact is that exaltedly virtuous heroines like Lady Ann were mainstream figures in plays and literature during the long 18th century. Another example--aimed at young readers--in the next post.

Published on June 08, 2022 00:00

June 6, 2022

CMP#104 The Bear and Forbear Heroine

Since I've begun my look at Jane Austen, I've become very interested in studying the now-obscure novels of her time. I think they shed a light on Austen's work. Click here for the first in the series. Click on "Authoresses" on the right for more about other authors in Austen's time. CMP#104: Absolutely angelic--the "bear and forbear" heroine

Since I've begun my look at Jane Austen, I've become very interested in studying the now-obscure novels of her time. I think they shed a light on Austen's work. Click here for the first in the series. Click on "Authoresses" on the right for more about other authors in Austen's time. CMP#104: Absolutely angelic--the "bear and forbear" heroine  Suffering in a garret In

earlier posts, we've looked

at "pictures of perfection" heroines who have no faults. These heroines can be contrasted with imperfect, deluded heroines such as Emma Woodhouse or Catherine Morland who start out with mistaken notions which are corrected in the course of the novel. The "picture of perfection" heroine does not undergo a character arc because they start out perfect. They suffer and endure and they are rewarded in the end.

Suffering in a garret In

earlier posts, we've looked

at "pictures of perfection" heroines who have no faults. These heroines can be contrasted with imperfect, deluded heroines such as Emma Woodhouse or Catherine Morland who start out with mistaken notions which are corrected in the course of the novel. The "picture of perfection" heroine does not undergo a character arc because they start out perfect. They suffer and endure and they are rewarded in the end.Now I’m going to talk about another type of heroine--a more extreme version of the "picture of perfection" heroine--the “bear and forbear” heroine. This type of heroine suffers intensely through no fault of their own, and puts up with a great deal of mistreatment. She is explicitly held up to the reader, particularly the female reader, as someone to admire and emulate.

A prime example of this type of heroine is Fanny Belton, the heroine of The Woman of Letters (1783). I referred to this novel previously in my list of heroines named Fanny. Fanny Belton, the daughter of a poor curate, is orphaned early in the story. She behaves impeccably through her various travails, fleeing would-be seducers, and bearing with the unkindness of her aunt and cousins. Tossed out of the house by her aunt, she supports herself by her pen while nearly starving in a garret and fends off more would-be seducers. She doesn’t get to marry the man she loves because he was forced to marry someone else. When she comes home from church after marrying a man she doesn’t love, she gets a letter from the man she does love, announcing that he is now a widower and wishes to marry her. So she misses her happy ending by one day. Fanny stays loyal to her worthless husband who only married her for her meagre savings. He takes all her money and spends it on drink and loose women. She and her child end up dying in debtor’s prison...

Epictetus (50 – c. 135 AD) The Woman of Letters is not an angry protest against the patriarchy. Apart from exhorting the reader to show more Christian charity toward fallen women and to help women in debtor’s prison, there is no call to action, no demand for criminal charges to be brought against titled and powerful sexual predators, no plea to change the common law that deemed that women’s property belongs to their husband, no call for reforms to the divorce laws, no calls, even, for reforms to the system of throwing people in prison for debt. Instead, the sufferings of Fanny Belton are intended to showcase her sublime rectitude. The virtue is the point, not the probabilities of the plot. Fanny's only consolation is the hope of happiness in the afterlife; there will be no justice for her here in this vale of tears. And the only fault the author ascribes to Fanny is that maybe, just maybe, she should have spent more time doing needlework and less time studying Greek and Latin as a child and thereby she’d be better able to support herself. However, Fanny’s study of the classical scholars such as Epictetus enables her to bear her sorrows with fortitude.

Epictetus (50 – c. 135 AD) The Woman of Letters is not an angry protest against the patriarchy. Apart from exhorting the reader to show more Christian charity toward fallen women and to help women in debtor’s prison, there is no call to action, no demand for criminal charges to be brought against titled and powerful sexual predators, no plea to change the common law that deemed that women’s property belongs to their husband, no call for reforms to the divorce laws, no calls, even, for reforms to the system of throwing people in prison for debt. Instead, the sufferings of Fanny Belton are intended to showcase her sublime rectitude. The virtue is the point, not the probabilities of the plot. Fanny's only consolation is the hope of happiness in the afterlife; there will be no justice for her here in this vale of tears. And the only fault the author ascribes to Fanny is that maybe, just maybe, she should have spent more time doing needlework and less time studying Greek and Latin as a child and thereby she’d be better able to support herself. However, Fanny’s study of the classical scholars such as Epictetus enables her to bear her sorrows with fortitude. The adage “bear and forbear" appears to originate with Epictetus. A book about classical proverbs explains: “Bear and forbear, a phrase frequently used by Epictetus, as embracing almost the whole that philosophy or human reason can teach us—Of this Epictetus as a memorable example, no man bearing the evils of life with more constancy or less coveting its enjoyments.” This explanation is by Robert Bland in his book, Proverbs, Chiefly Taken from the Adagia of Erasmus, with Explanations and Further Illustrated by Corresponding Examples from the Spanish, Italian, French and English Languages.

Patient Griselda

We cannot understand how any age could have been interested in Patient Griselda. -- Lionel Trilling

Patient Griselda, Frank Cadogan Cowper The ur- “bear and forbear” heroine is Patient Griselda, from The Decameron, a fourteenth-century collection of tales by the Italian writer Boccaccio. Chaucer retold the story of patient Griselda in his Canterbury Tales, and I think it was generally well-known as a folk tale. Griselda is an ordinary peasant woman who marries a nobleman. He treats her horribly--

here are the details,

if you want them--and she responds with submission and loyalty. Her virtue is rewarded in the end.

Patient Griselda, Frank Cadogan Cowper The ur- “bear and forbear” heroine is Patient Griselda, from The Decameron, a fourteenth-century collection of tales by the Italian writer Boccaccio. Chaucer retold the story of patient Griselda in his Canterbury Tales, and I think it was generally well-known as a folk tale. Griselda is an ordinary peasant woman who marries a nobleman. He treats her horribly--

here are the details,

if you want them--and she responds with submission and loyalty. Her virtue is rewarded in the end. I have no idea how readers of the day responded to the story of Patient Griselda, but to modern minds it is bizarre. How can being reunited with someone who has subjected you to horrible psychological abuse and deception be regarded as a “happy ending”?

Scholar Lois Bueler calls Patient Griselda an archetype of the "tested woman plot" and she finds many examples in literature.

Another example of a heroine who is tested and harbors no resentment is Hero in Much Ado About Nothing. Falsely accused of being unchaste --by her groom! --at the altar! She goes away (and presumably cries) until her good name is restored and she marries the man who defamed her.

Maria Edgeworth spoke approvingly of the heroine who bears her wrongs with quiet resignation in her novel Leonora, and we have a bit of a reminder of the difference between Elinor and Marianne in Sense & Sensibility: “The sacrifice of the strongest feelings of the human heart to a sense of duty is to be called mean, or absurd; but the shameless phrensy of passion, exposing itself to public gaze, is to be an object of admiration. These heroines talk of strength of mind; but they forget that strength of mind is to be shown in resisting their passions, not in yielding to them. Without being absolutely of an opinion, which I have heard maintained, that all virtue is sacrifice, I am convinced that the essential characteristic of virtue is to bear and forbear. These sentimentalists can do neither. They talk of sacrifices and generosity; but they are the veriest egotists—the most selfish creatures alive.”

Edgeworth also wrote a satirical novella, A Modern Griselda, about a neurotic, manipulative woman who destroys her marriage. A culturally literate person in Austen's time knew the tale of Patient Griselda. Heroines of Filial Piety

In Lady Jane’s Pocket, (1815) we meet the minor character of Miss Bromley, the only daughter of a widow who has grown deaf, senile, and peevish.

“Nothing can be more pitiable than her situation;” explains her friend Mrs. Sinclair, “doomed to be shut up with that poor superannuated woman all day, and in the evening obliged to make up a card party with a set that hardly know clubs from spades.”

But worse, Miss Bromley can’t leave her mother to emigrate to Canada to be with Major Knightley, the man she loves. “I do not know any one who has more merit. To bear and forbear has ever been her fate, and her filial piety has hardly any example.”

In Agatha, or a Narrative of Recent Events, (1796), we meet Jemima, a poor cottager, who takes care of her aged grandmother rather than leave the village to be with the man she loves. The heroine Agnes, touched by her sorrowful looks, comes to visit her and hear her story. Jemima’s “face was pale, and bore the strongest marks of sorrow; yet of a sorrow tempered with resignation, and which spoke the calm submission of a mild and gentle spirit, which had early learned to ‘bear and forebear.’” Her virtue is soon rewarded when she is reunited with her lover.

In Agatha, or a Narrative of Recent Events, (1796), we meet Jemima, a poor cottager, who takes care of her aged grandmother rather than leave the village to be with the man she loves. The heroine Agnes, touched by her sorrowful looks, comes to visit her and hear her story. Jemima’s “face was pale, and bore the strongest marks of sorrow; yet of a sorrow tempered with resignation, and which spoke the calm submission of a mild and gentle spirit, which had early learned to ‘bear and forebear.’” Her virtue is soon rewarded when she is reunited with her lover. However, not all other heroines who “bear and forbear” do not get a happy ending, including the heroine Agatha herself. Agatha agrees to take her vows and become a nun in France in the name of filial obedience, because her mother made a vow that Agatha would do so. In France, Agatha is caught up in the French Revolution, which persecuted priests and nuns. If she had instead ignored her mother’s injunction and married the man she loved, she and everyone she knows would have been happy, including her parents, who end up being guillotined by the revolutionaries. Instead, everyone ends up miserable or dead while Agatha, “blest with a spotless and self-approving heart… leads a life of peaceful resignation,” far from the troubled world, “in the firm hope and assurance of Eternal Happiness hereafter.”

You might be interested to know that here, at least, the reviewer for The Analytical Review felt he had to draw the line on this whole “sacrifice” thing, especially when they sacrifice involves Catholicism, for Pete’s sake: The conduct of Agatha, however glossed over with the specious names of heroism and filial piety, is in reality both weak and criminal: the sacrifices which she makes are not to reason and utility, but to prejudice and fanaticism…. to make rash vows is folly, to keep them vice; to promise for another person, or to suppose that other person under an obligation to perform such a promise, under which this story turns, though made by a parent, is still wilder and more absurd. Works of fiction, in order to render virtue lovely and imitable, should place it upon a just foundation… To draw characters, in which every thing human is hunted out of the composition, as in the heroine of the present work, is not to propose models for imitation. I think understanding this "bear and forbear" philosophy, (whether or not you agree with it) and the fact that it forms a thread in Western thinking, will shed light on the character of Fanny Price in Mansfield Park better. If you, like many others, don’t care for Fanny Price, I don’t expect to reconcile you to her, I only aim to help people understand her better. My intention is to place Fanny within her context in literature of this sort.

First, other examples of “bear and forbear” wives and heroines in literature, and some information which might surprise you about the publisher of one of these stories. At the end of A Marriage of Attachment, the second book in my Mansfield Trilogy, Fanny stops bearing and forbearing and has a confrontation of sorts with her Aunt Norris. Go here for more about my books.

Robert Bland’s guide to proverbial sayings of the classical authors was published in the same year as Mansfield Park and by the same publisher, Egerton. I’m not saying that there is a connection between these two books, it’s just that no Austenite who had noticed this fact could omit to mention it.

An entertaining modern review and analysis of Agatha, or, A Narrative Of Recent Events is to be found at the “Course of Steady Reading” blog. Bueler, Lois E.. The Tested Woman Plot: Women's Choices, Men's Judgments, and the Shaping of Stories. United Kingdom, Ohio State University Press, 2001.

Published on June 06, 2022 00:00

May 30, 2022

CMP#103 Fanny, the forgiving heroine

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who speak of the past mainly to condemn but also want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP# 103 Book Review: Fanny, or, the deserted daughter

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who speak of the past mainly to condemn but also want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP# 103 Book Review: Fanny, or, the deserted daughter  Admired by Lord de Grey I've been talking about the Austen interpretations of scholar Jillian Heydt-Stevenson and why I disagree with them. To recap, I looked at whether the name "Fanny" had the same connotations in Austen's time as it does today. I concluded that it was fine to name your daughter "Fanny" back then. There were a lot of nice Fannies around. As well, I expressed my doubt about the theory that Austen wanted readers of Mansfield Park to think of an essay by Dr. Johnson concerning a girl who had been groomed into prostitution by an older male relative. I noted that the supposed similarity between Mansfield Park and Johnson's essays were not remarkable or noteworthy at all. It isn't at all difficult to find many novels which share plot points with Mansfield Park, particularly novels with the theme of a poor dependent heroine.

Admired by Lord de Grey I've been talking about the Austen interpretations of scholar Jillian Heydt-Stevenson and why I disagree with them. To recap, I looked at whether the name "Fanny" had the same connotations in Austen's time as it does today. I concluded that it was fine to name your daughter "Fanny" back then. There were a lot of nice Fannies around. As well, I expressed my doubt about the theory that Austen wanted readers of Mansfield Park to think of an essay by Dr. Johnson concerning a girl who had been groomed into prostitution by an older male relative. I noted that the supposed similarity between Mansfield Park and Johnson's essays were not remarkable or noteworthy at all. It isn't at all difficult to find many novels which share plot points with Mansfield Park, particularly novels with the theme of a poor dependent heroine. Here, for example, is another novel featuring a sweet and faultless Fanny as its heroine. This story has some “remarkable similarities” to both Mansfield Park and Johnson’s essays about Misella the prostitute. But this novel does not have a radical anti-patriarchal theme, as we will see.

In Fanny, or, the deserted daughter (1792), Fanny Vincent, a girl of unknown birth (it's complicated) is raised in the home of a baronet, Sir Peter Sinclair, and is looked down upon by the baronet’s daughter...

The Prince Regent setting a bad example Starts out like Mansfield Park

The Prince Regent setting a bad example Starts out like Mansfield ParkFanny’s guardian, Sir Peter Sinclair, a baronet, is so debauched that after his wife’s death, his home “was by turns the prey of gamblers, parasites, and harlots. Women, were, however, his prevailing passion, and his house was perpetually filled with a tribe of loose, disorderly, females, who excluded all better company, and fixed a stigma on Sinclair-house…”

This is rather similar to Mary Crawford’s situation in Mansfield Park; after her aunt dies and she has to leave her uncle’s house because he brought his mistress to live with him openly. I think there are other similarities too, but I'll leave them for Austenites to spot.

Augusta Sinclair, the baronet’s daughter, is actively cruel to Fanny. After her mother--who was Fanny’s protector—dies, Augusta maliciously downgrades her from companion to waiting woman. Augusta discontinues Fanny’s piano lessons as not suitable for her station in life. Fanny "determines to relinquish all accomplishments" except needlework. She has to eat with the upper servants and is constantly reminded of her dependent position.

Fanny grows into a beautiful young woman and Augusta’s father, Sir Peter, notices. He holds a ball for the neighbourhood and gives Fanny a gift of some diamonds for her hair and his own miniature portrait, set in diamonds, for her to wear to the dance. The gift makes Fanny feel awkward. She doesn’t want to wear the jewelry to the ball, but Sir Peter insists. Spoilers Follow

From there, the plot diverges from Mansfield Park and is more like Johnson's essay about Misella. After the dance, (where everybody notices Sir Peter's attentions to Fanny and rumours start to circulate about her), Sir Peter tells our vulnerable, dependent heroine that she has a choice: she can become his mistress and be well-rewarded, or he will take her by force. He carries her off to a remote farmhouse where he has taken other girls in the past. Mary, a young servant, helps her escape in time.

Fanny finds work as a governess in London but, as is typical with novels of this type, she encounters cruelty through no fault of her own. The problem is, she is a beautiful girl and there are two young men in the house: Edmund and Matthew, who are, to say the least, distracted by her presence in the household. Edmund in particular pursues her, but she wants nothing to do with him. He is boastful and speaks wildly, rather like John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey. The women of the household resent her and want her out.

Then Fanny is offered a home by a society lady, but she goes from the frying-pan into the fire. She is preyed upon by a new admirer, Lord Montraville. Fanny repels his attempts to seduce her, and he feels guilty, which is a new sensation for him.

So let's compare the fictional Fanny Vincent to Dr. Johnson's Misella of my previous post. Both are penniless dependents. Both are pressured by their guardians into becoming kept women. Misella succumbs, but Fanny, though utterly powerless, has moral agency. She flees and tries to support herself. The tension and drama centers around Fanny being able to maintain her chastity. And we can add that Misella's story has the stamp of reality, while Fanny's story is a Cinderella fantasy, because of what comes next. Never mind the why and wherefore,

love can level ranks and therefore.... Love Can Level Ranks?

Lord de Grey, the nobleman next door, loves Fanny and begs her to marry him. She hesitates because she knows his parents won't approve. She calls herself "the unknown offspring at best of penury, perhaps of vice and infamy." In other words, she doesn't know if she comes from a good family and in fact she was probably born out of wedlock.

Lord de Grey declares that he doesn't care: “Oh! Miss Vincent, you cannot imagine that motives of no real consequence will ever outweigh with me the real happiness of the heart; that feeling the most blessed of men in your society, in your love, the whole world could offer any thing to my mind which could teach me to know regret.”

Here is an outright declaration that love levels ranks. Love conquers all. The class system doesn't matter. Compare this egalitarian message to Harriet Smith in Emma, the natural daughter of nobody knows who. She is not good enough to marry Mr. Elton, let alone Mr. Knightley. Or compare this to Ann Elliot's reaction to possibly having Mrs. Clay for a stepmother. Or compare this to Fanny Price's humility. Though she loves Edmund, "To her he could be nothing under any circumstances; nothing dearer than a friend. Why did such an idea occur to her even enough to be reprobated and forbidden? It ought not to have touched on the confines of her imagination."

After a lot of weeping and angst, Lord de Grey persuades Fanny to marry him in secret. Yes, Lord de Grey marries Fanny not knowing who she is. Can the author really intend such an egalitarian message?

Not really. Because soon after the marriage, we have the Big Reveal, which re-asserts the social order. By virtue of an the amazing coincidence, Fanny meets the one woman who knows who her parents are. Lord Montraville is actually her dad! Of course Fanny is blue-blooded and the offspring of legal marriage.

So we have it both ways: the message of Fanny, a deserted daughter is that love conquers all but also that bloodlines and family matter. Lord de Grey couldn't possibly have fallen in love with, say, the daughter of the dustman. The English class system is vindicated, just as occurs in The HMS Pinafore (1878), a hundred years after the Fanny novel. Nothing much changed with foundling plots.

Fanny Price too, was a powerless dependent. Everyone knew who her parents were, everyone knew who she was, but nobody knew her true worth, not until the family was rocked by scandal and crisis.

"Love has never crossed such boundaries of class." The author of Fanny, a deserted daughter does not like dwelling on guilt and misery any more than Jane Austen. This author resolves the storyline with a lesson about forgiveness. There is no comeuppance for the repugnant Sir Peter. The heroine, out of Christian charity, "cordially forgave" him, "willingly losing all remembrance of intended injury in gratitude for former favours" (i.e. she forgives the fact that he abducted her and was going to take her by force, because he paid for her upbringing and education.) And he is repentant because he is ill and will soon meet his Maker.

Fanny (now Lady de Grey) also forgives Lord Montraville, not only for trying to seduce her when he didn't know she was his daughter, but because she got misplaced, so to speak, as a baby. We know that Fanny Price's father made a "coarse joke" about her, and that Sir Thomas also remarked appreciatively on Fanny's improved complexion and figure. But that's nothing compared to the incest teases of other sentimental and gothic novels of the period. It's weird stuff.

Augusta, who made Fanny's life miserable when she was a poor nobody, is not repentant but the author makes sure that her life is hollow and tawdry. Now married, Augusta had "neither sense nor principle," and "[h]er character was totally lost, while she appeared in all public places... covered with jewels, exceedingly rouged, and attended by the minions of the present moment."

This tale, though bizarre to modern sensibilities, contained nothing to offend the reviewers of the time. The anonymous critic writing in the Monthly Review approved of the “moral tendency of the tale.” The author herself loftily declared in her preface, that if she were “conscious of a single line inimical to the interests of virtue, she would burn the book, rather than present it to the public, though she were sure of being celebrated as the first novel-writer of the age.” Whatever we might think of the moral lessons of Fanny, or, a deserted daughter, I think it is intended to valorize the saintly, forgiving, heroine. No matter what the Fates throw her way, no matter how she is misused and abused, she is never resentful. However, the moral lesson is packaged in a Cinderella fantasy. Fanny is rewarded in the end with true love, high status, and wealth.

Coming up on the blog, more examples of the "bear and forbear" heroine... Fanny, a deserted daughter, was advertised as "the first literary attempt of a young lady." Some sources give the author as Margaret Holford of Cheshire, but, but this looks to be a confusion with Holford's publication Fanny and Selima. In 1801, Holford published a novel titled First Impressions, which was of course Jane Austen's chosen title for her unpublished story of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy. Austen changed the name to Pride & Prejudice.

Whoever the author is, she is more explicit than Austen in describing scenes of vice and sexual peril. There are fallen women in Austen, but the crimes and the consequences are kept offstage. Other writers such as Elizabeth Helme, Anna Maria Bennett and Maria Smyth were more explicit about bawds, brothels, prostitutes, venereal disease, and powerful men preying on vulnerable females. There's a whole other discussion to be had about the way that this and other novels portray the nobility, but I'll get to that.

Published on May 30, 2022 00:00

May 24, 2022

CMP#102 The Misery of Misella

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who speak of the past mainly to condemn--but also want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history--have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#102 Did Dr. Johnson's Misella influence Austen's Mansfield Park?

In the last post

, I outlined scholar Jillian Heydt-Stevenson’s arguments in favour of her contention that the message of Mansfield Park is that marriage is akin to prostitution. I’ll repeat those arguments here:

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who speak of the past mainly to condemn--but also want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history--have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#102 Did Dr. Johnson's Misella influence Austen's Mansfield Park?

In the last post

, I outlined scholar Jillian Heydt-Stevenson’s arguments in favour of her contention that the message of Mansfield Park is that marriage is akin to prostitution. I’ll repeat those arguments here:  Dr. Johnson (1709-1784) The name “Fanny” suggests lady parts and prostitution.Fanny Price shares her name with Fanny Hill, a prostitute in a famous book which is still read today.Dr. Johnson, one of Austen’s favourite authors, wrote two essays about a prostitute, and the prostitute’s life story has plot similarities to Mansfield Park. Austen intended for her readers to notice this connection.A lewd riddle referenced in Emma includes the name “Fanny," a name associated with prostitutes, see #1.In the previous post I looked at (1) and (2). In this post, I’ll look at (3) and later, (a very deep dive), I’ll examine (4). Did a pair of essays by Dr. Johnson provide Austen with the narrative building blocks and the theme for Mansfield Park, supposing the theme is that marriage is like prostitution?

Dr. Johnson (1709-1784) The name “Fanny” suggests lady parts and prostitution.Fanny Price shares her name with Fanny Hill, a prostitute in a famous book which is still read today.Dr. Johnson, one of Austen’s favourite authors, wrote two essays about a prostitute, and the prostitute’s life story has plot similarities to Mansfield Park. Austen intended for her readers to notice this connection.A lewd riddle referenced in Emma includes the name “Fanny," a name associated with prostitutes, see #1.In the previous post I looked at (1) and (2). In this post, I’ll look at (3) and later, (a very deep dive), I’ll examine (4). Did a pair of essays by Dr. Johnson provide Austen with the narrative building blocks and the theme for Mansfield Park, supposing the theme is that marriage is like prostitution?Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), known as “the Doctor,” was--as Austenites know--Austen’s favorite moral writer in prose. The compiler of a famous dictionary and author of many essays, memoirs, and other works, he is a towering figure in English letters. Here is Heydt-Stevenson’s passage about Dr. Johnson where she asserts a definite connection between Mansfield Park and two essays by Dr. Johnson. “Austen also associates courtship with prostitution through the significant intertextual relations between [Fanny Price’s] story and [two essays by Dr. Johnson] numbers 170 and 171 from [the periodical] The Rambler. “The History of Misella Debauched by her relation” and “Misella’s Description of the Life of a Prostitute,” a sentimental narrative of a poor young woman seduced by her cousin/guardian.”

and

“The remarkable parallels between these two narratives—parallels that critics have not previously noted—suggest that Austen was working both with and against Johnson’s (apparently) nonfictional account.” My response:Yes, both stories start off the same way.But they diverge: Misella is groomed into prostitution and a life of misery and infamy, while Fanny Price is pressured to marry someone she doesn't love and then marries the man she loves.Heydt-Stevenson assumes that somebody who reads a story about a girl being pressured to make a financially advantageous marriage would think of prostitution and would think specifically of Johnson's essays. However,I can point to many stories featuring dependent females, so the "remarkable" parallels between Johnson and Austen are not so remarkable. It was a standard literary trope of the day and the starting point for many novels.I can point to stories in which the vulnerable female is pressured to become a courtesan; in other words, these stories more closely resemble Johnson's story than does Mansfield Park. I can point to stories that more closely resemble Mansfield Park than does Johnson's essay.I can point to stories where "fallen women" aka "deviant sisters," are treated sympathetically, as in Johnson's essay.But "deviant sisters" are not treated sympathetically in Mansfield Park.By tracing the roots of Mansfield Park to Johnson’s essay, Heydt-Stevenson attempts to strengthen her contention that Fanny Price’s story “collapse[s] the boundary between marriage and prostitution." But her assertion that there's a connection between Mansfield Park and Johnson's essays is nothing more than that--an assertion.

Progress of a Woman of Pleasure (detail) 1) However “remarkable” the resemblance between Johnson’s Misella and Austen’s Fanny Price might appear, a survey of 18th-century literature quickly reveals that stories about dependent female relations were not at all unusual and certainly not unique to Johnson and Austen. Further, dependent female relations, vulnerable to neglect, abuse, and sexual exploitation, were very common in real life. So, I disagree that the similarity between the Misella essays and Mansfield Park is “remarkable” at all.

Progress of a Woman of Pleasure (detail) 1) However “remarkable” the resemblance between Johnson’s Misella and Austen’s Fanny Price might appear, a survey of 18th-century literature quickly reveals that stories about dependent female relations were not at all unusual and certainly not unique to Johnson and Austen. Further, dependent female relations, vulnerable to neglect, abuse, and sexual exploitation, were very common in real life. So, I disagree that the similarity between the Misella essays and Mansfield Park is “remarkable” at all. The only similarity between the two essays and Mansfield Park occurs at the beginning of Johnson’s first essay in which Misella, (telling her story in the first person) explains: “I am of a good family, but my father was burthened with more children than he could decently support. A wealthy relation, as he travelled from London to his country seat, condescending to make him a visit, was touched with compassion… and resolved [to take] the care of a child upon him.”

2) After this opening, the plot, and as I will argue, the theme, diverges completely from Mansfield Park. Misella, financially dependent on her guardian, “saw with horror that he was contriving to perpetuate his gratification, and was desirous to fit me to his purpose, by complete and radical corruption.” She gives in, becomes pregnant, and it looks like she induces an miscarriage: (“He provided all that was necessary and in a few weeks congratulated me upon my escape from the danger which we had both expected with so much anxiety.”) Misella subsequently becomes the mistress of other men, and finally sinks to common prostitution. This is a story of sexual grooming that was undoubtedly all too true then and still true today.

3) Heydt-Stevenson equates the pressures placed on Fanny Price to marry Henry Crawford with the sexual bondage endured by Misella. Here we bump up against the Heydt-Stevenson thesis that courtship is like sexual grooming and is tied to money. This supposes that both Austen and Dr. Johnson thought that marriage was like prostitution. Or it supposes that anyone who read Dr. Johnson would read his essays and think to themselves, "you know what? marriage is kind of like what happens to this Misella girl."

3) Heydt-Stevenson equates the pressures placed on Fanny Price to marry Henry Crawford with the sexual bondage endured by Misella. Here we bump up against the Heydt-Stevenson thesis that courtship is like sexual grooming and is tied to money. This supposes that both Austen and Dr. Johnson thought that marriage was like prostitution. Or it supposes that anyone who read Dr. Johnson would read his essays and think to themselves, "you know what? marriage is kind of like what happens to this Misella girl."This is a remarkably wild leap in the dark for Heydt-Stevenson to make in the face of all the contrary textual evidence. She can of course believe whatever she wants about marriage and prostitution. But to assert so confidently that Johnson--a man who held orthodox religious views--would see things the same way, is rather bewildering.

Johnson's message and purpose was NOT to equate marriage with being a sex worker. Misella's story is both a warning and a call for compassion. Misella writes: “I am one of those beings from whom many, that melt at the sight of all other misery, think it meritorious to withhold relief; one whom the rigour of virtuous indignation dooms to suffer without complaint, and perish without regard…" The prostitute is an outcast from society. Johnson's purpose was to urge compassion for women who have few economic choices in life and no legal independence, who are essentially forced into the sex trade.

Sir Charles Grandison rescues Harriet Byron (4 to 7) Heydt-Stevenson is looking through the wrong end of the telescope when she traces a backwards line from Mansfield Park to Johnson's Misella essays. A broader survey of the literature of the day will show how frequently poor dependent females appeared as heroines.For more novels about poor dependent females living with relatives or other benefactors, consider Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1797),

The Bristol Heiress

(1809), Motherless Mary, (1816), The Woman of Letters (1783), and The Gipsey Countess (1799).There are many, many stories about innocent girls being pressured into becoming courtesans including the influential Samuel Richardson novels Pamela and Clarissa. Or try The Woman of Letters (1783), Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1797), Constance (1785), or The Officer's Daughter (1810). See also

"the fate worse than death."

For novels with similarities to Mansfield Park, try Celia in Search of a Husband (1809), Maria Edgeworth's Madame Panache (1806), Clarentine (1796), Geraldine (1820), and Fanny, a novel, in a series of letters (1786).For heroines who are benevolent to "fallen women," try Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarven (1799), Celia in Search of a Husband (1809), The Officer's Daughter (1810), and Fanny Fitz York (1818).The History of Fanny Seymour (1769) is notable for its protest of the way girls were forced into marriage as a financial arrangement between families and it also treats a "fallen woman" very sympathetically. But it still doesn't "collapse the boundaries" between sex work and marriage insofar as the attitudes of the characters are concerned.In an age when marriages were about alliances between families, and not about romantic love, males as well as females were pressured or forced into marriages they didn't want. Men are coerced in The Woman of Letters (1783), Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1785), The Denial, or The Happy Retreat (1792), Consequences or Adventures at Rraxal Castle (1797), Thinks I to Myself (1812), Coraly (1819), and both the hero and heroine face this dilemma in the play The Runaway (1776).

Sir Charles Grandison rescues Harriet Byron (4 to 7) Heydt-Stevenson is looking through the wrong end of the telescope when she traces a backwards line from Mansfield Park to Johnson's Misella essays. A broader survey of the literature of the day will show how frequently poor dependent females appeared as heroines.For more novels about poor dependent females living with relatives or other benefactors, consider Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1797),

The Bristol Heiress

(1809), Motherless Mary, (1816), The Woman of Letters (1783), and The Gipsey Countess (1799).There are many, many stories about innocent girls being pressured into becoming courtesans including the influential Samuel Richardson novels Pamela and Clarissa. Or try The Woman of Letters (1783), Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1797), Constance (1785), or The Officer's Daughter (1810). See also

"the fate worse than death."

For novels with similarities to Mansfield Park, try Celia in Search of a Husband (1809), Maria Edgeworth's Madame Panache (1806), Clarentine (1796), Geraldine (1820), and Fanny, a novel, in a series of letters (1786).For heroines who are benevolent to "fallen women," try Albert, or the Wilds of Strathnarven (1799), Celia in Search of a Husband (1809), The Officer's Daughter (1810), and Fanny Fitz York (1818).The History of Fanny Seymour (1769) is notable for its protest of the way girls were forced into marriage as a financial arrangement between families and it also treats a "fallen woman" very sympathetically. But it still doesn't "collapse the boundaries" between sex work and marriage insofar as the attitudes of the characters are concerned.In an age when marriages were about alliances between families, and not about romantic love, males as well as females were pressured or forced into marriages they didn't want. Men are coerced in The Woman of Letters (1783), Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1785), The Denial, or The Happy Retreat (1792), Consequences or Adventures at Rraxal Castle (1797), Thinks I to Myself (1812), Coraly (1819), and both the hero and heroine face this dilemma in the play The Runaway (1776).

Happy ending or bitter ironic joke? Having it both ways

Happy ending or bitter ironic joke? Having it both ways8) Heydt-Stevenson argues that “Mansfield Park provides the opportunity to break down oppositions between respectable women and their deviant sisters, insofar as their bodies are negotiated as agents of exchange.”

But--quite obviously--Mansfield Park is the most judgmental of Austen’s novels when it comes to “deviant sisters.” Maria Bertram is punished for adultery, in contrast to Lydia Bennet, who is not punished for fornication in Pride & Prejudice. The compassion that Dr. Johnson urges his readers to show to fallen women is on display in Sense & Sensibility, in Colonel Brandon’s anguish over his lost love Eliza who was forced into marriage and the ran away with a lover. In Mansfield Park, Edmund and Sir Thomas are so disgusted by Maria and Henry’s “crime” that they don’t want her to marry Henry, and Maria can never darken the door of Mansfield Park again.

Heydt-Stevenson handles disjunction between her anti-patriarchal theories and the actual tone of Mansfield Park by explaining that Austen is intentionally having it both ways (emphasis added): “The remarkable parallels between these two narratives—parallels that critics have not previously noted—suggest that Austen was working both with and against Johnson’s (apparently) nonfictional account.” And: "Austen denounces the unequal ratio between male freedom and female constraint... [but she] also seems to acknowledge the irony [that she's written a marriage-plot novel] even though she is aware of the disturbing possibilities inherent in courtship..."

That "seems to" is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

Heydt-Stevenson's theory is therefore unassailable: everything that accords with her theory supports her theory, and everything that contradicts it, supports her theory as well. Because irony.

The Outcast (detail), Richard Redgrave Turning the story upside down to fit your thesis

The Outcast (detail), Richard Redgrave Turning the story upside down to fit your thesisFor Heydt-Stevenson's theory to hold together, we must conclude that Fanny and Edmund are not a happy couple who love and respect one another. Edmund doesn't mean it when he says Fanny is "too good" for him. Fanny is a willing accomplice in the bleak masquerade that is courtship and marriage. “Austen’s final joke is that one of the fallen women is in the parsonage.” And: “in such a society, all women are fallen." I know many people are not satisfied with the Edmund/Fanny pairing, but that's not the same as declaring the novel is a dark satiric attack on marriage and the patriarchy.

(9) As mentioned, Heydt-Stevenson's flimsy chain of reasoning relies on the assumption that she, Austen, and Dr. Johnson all have the same attitudes towards marriage and prostitution, that the former was just a prettied-up version of the latter. I don't think so. I don't think Austen, as a conventional churchwoman, held so low a view of matrimony. Here are some quotes from Dr. Johnson on marriage. I don't see any quotes where he says it's like prostitution. See also a discussion of 18th century attitudes about female chastity. I think Heydt-Stevenson's effort to connect Johnson's essays and Mansfield Park--in terms of either plot or theme--is unconvincing. Critics hadn’t previously noted a connection between the two because there was nothing worth noting. I don’t think Heydt-Stevenson has made a discovery here.

In future posts I'll tell you about: a novel that resembles Mansfield Park much more closely than the Misella essays, and a novel that takes up the topic of prostitution far more explicitly than Austen. For more critiques on modern Austen scholarship, see here. When I got to the end of A Contrary Wind, my novel based on Mansfield Park, I decided that Fanny Price was just not ready for marriage. She needed to grow up and find herself first. So the book became a trilogy. Click here for more about my books.

Scholar Elaine Bander gives an excellent overview of the Georgian novel and how Austen both parodied and adapted its tropes in her own work, in "Jane Austen and the Georgian Novel," in The Routledge Companion to Jane Austen. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2021.

Heydt-Stevenson, Jillian. Austen's Unbecoming Conjunctions : Subversive Laughter, Embodied History / Palgrave Macmillan, 2005

"I'm felicitous since during the course of the penultimate solar sojourn, I terminated my uninterrupted categorisation of the vocabulary of our post-Norman tongue."

Published on May 24, 2022 00:00

May 17, 2022

CMP#101 "Why do I not see my little Fanny?"

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who think we should speak of the past only to condemn it, but still want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history, have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#101 Did Austen want us to think about lady parts?

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who think we should speak of the past only to condemn it, but still want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history, have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#101 Did Austen want us to think about lady parts?  Game of Billiards (detail), 1807, Louis-Léopold Boilly “Where is my Fanny? Why do I not see my little Fanny?” asks Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park, and posterity snickers.

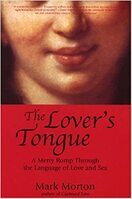

Game of Billiards (detail), 1807, Louis-Léopold Boilly “Where is my Fanny? Why do I not see my little Fanny?” asks Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park, and posterity snickers.Where I'm from, "fanny" means a derriere, as in "get your little fanny over here." But I've read that it's also a slang term for lady parts. I wanted to confirm this, then I got embarrassed when I thought about my Google search history, so I stopped. Then I found a useful book called The Lover's Tongue, which says "fanny" “emerged around 1928, and is now a familiar, albeit quaint, euphemism for the buttocks. The word fanny might have been inspired by John Cleland’s 1749 erotic novel, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, the protagonist of which, Fanny Hill, is frequently exposing her bottom.”

Author Mark Morton adds: "Fanny has also been used to refer to the female genitals which might make a connection to Fanny Hill even more feasible.” So there you go.

Anyway, there are many slang names for lady parts, that’s for sure. And the derriere is undeniably an important part of female charms and is particularly in vogue today, it seems.

The question is, when we think of Fanny Price, are we supposed to think about lady parts? And when we think about lady parts, are supposed to think about prostitutes? And when we think of prostitutes, are we supposed to reflect that, after all, marriage is pretty much like prostitution? And are we intended to go on and realize that Mansfield Park "rigorously links prostitution to courtship and courtship to corruption in the culture at large"? Because, look at how Fanny's brother William got promoted to lieutenant...

In Austen's Unbecoming Conjunctions, Subversive Laughter, Embodied History, scholar Jillian Heydt-Stevenson argues Austen intended for her readers to follow this ramshackle train of thought...

Sir Thomas and Fanny, 1983 mini-series I don’t want to quote Heydt-Stevenson out of context. She presents more than one argument in support of her thesis that we’re supposed to think of prostitutes when we think of Fanny Price. Heydt-Stevenson contends:The name “Fanny” suggests lady parts and prostitution and "Price" suggests prostitution.“Fanny” shares her name with Fanny Hill, a prostitute and protagonist of a famous book which is still read today. Two 1751 essays by Dr. Samuel Johnson, one of Austen’s favourite authors, bear similarities to Mansfield Park. These essays tell the story of a girl whose older relative and guardian is a sexual predator.A riddle referenced in Emma includes the name “Fanny,” which makes us think of prostitutes, which makes us, etc…Fanny's brother William is the beneficiary of Henry Crawford's intervention on his behalf, a promotion tied to power and sex. The corrupt system of patronage in the Royal Navy is but one aspect of "the way the patriarchal system objectifies both men and women" and "both Fanny and William become negotiable commodities..." In this post I’ll look at (1) and (2). Next, I’ll look at (3) and in the future (a very deep dive), I'll examine (4). As for (5), I think we have only to reflect on how intensely proud Austen was of her sailor brothers Francis and Charles, and how positively she portrays William Price in Mansfield Park and the navy in general in Persuasion but maybe I'll take that up in future. Anyway, on with the look at Fanny and her fanny... “[Fanny’s] very name signifies prostitution: the price of the body, a fact that seems to link her etymologically to the infamous Fanny Hill, the heroine of John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1749), familiarly referred to as Fanny Hill, the narrative that helped codify the name Fanny as slang for female genitalia… I am not suggesting that by including the name Fanny, a common enough appelation, Austen alludes to the Memoirs.” Declining popularity of the name "Fanny" Notice how Heydt-Stevenson suggests and then disclaims; the sly use of “seems” in “seems to link her etymogically,” followed by a disclaimer … “I am not suggesting that… Austen alludes to the Memoirs.”

Sir Thomas and Fanny, 1983 mini-series I don’t want to quote Heydt-Stevenson out of context. She presents more than one argument in support of her thesis that we’re supposed to think of prostitutes when we think of Fanny Price. Heydt-Stevenson contends:The name “Fanny” suggests lady parts and prostitution and "Price" suggests prostitution.“Fanny” shares her name with Fanny Hill, a prostitute and protagonist of a famous book which is still read today. Two 1751 essays by Dr. Samuel Johnson, one of Austen’s favourite authors, bear similarities to Mansfield Park. These essays tell the story of a girl whose older relative and guardian is a sexual predator.A riddle referenced in Emma includes the name “Fanny,” which makes us think of prostitutes, which makes us, etc…Fanny's brother William is the beneficiary of Henry Crawford's intervention on his behalf, a promotion tied to power and sex. The corrupt system of patronage in the Royal Navy is but one aspect of "the way the patriarchal system objectifies both men and women" and "both Fanny and William become negotiable commodities..." In this post I’ll look at (1) and (2). Next, I’ll look at (3) and in the future (a very deep dive), I'll examine (4). As for (5), I think we have only to reflect on how intensely proud Austen was of her sailor brothers Francis and Charles, and how positively she portrays William Price in Mansfield Park and the navy in general in Persuasion but maybe I'll take that up in future. Anyway, on with the look at Fanny and her fanny... “[Fanny’s] very name signifies prostitution: the price of the body, a fact that seems to link her etymologically to the infamous Fanny Hill, the heroine of John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1749), familiarly referred to as Fanny Hill, the narrative that helped codify the name Fanny as slang for female genitalia… I am not suggesting that by including the name Fanny, a common enough appelation, Austen alludes to the Memoirs.” Declining popularity of the name "Fanny" Notice how Heydt-Stevenson suggests and then disclaims; the sly use of “seems” in “seems to link her etymogically,” followed by a disclaimer … “I am not suggesting that… Austen alludes to the Memoirs.”On the other hand, Heydt-Stevenson confidently asserts that the last name Price “signifies prostitution," as though no other allusion to “price” could possibly occur to mind, as though the only thing people purchase with money is other people’s bodies. Why, for example, would genteel readers not think of the King James Version of Proverbs 31:10?

Who can find a virtuous woman? for her price is far above rubies. The heart of her husband doth safely trust in her.

Fanny’s virtue, in fact, is one reason Henry Crawford wants to marry her; she is “well principled and religious." “I could so wholly and absolutely confide in her [he tells his sister], and that is what I want.” “Confide” in this context means “trust.”

If Austen intended symbolism by the name "Price," maybe she means that Sir Thomas and Edmund discover her true value at the end of the book. Sir Thomas by then is "Sick of ambitious and mercenary connexions, prizing more and more the sterling good of principle and temper..." Look at the words Austen uses: "prize" "sterling"...

Fanny Murray (1729 – 1778) "A common enough appellation"

Fanny Murray (1729 – 1778) "A common enough appellation"“Frances” and its diminutive “Fanny,” were "common enough" in the past, but not so common today (see the chart above). There was the well-known real-life Frances Burney, aka Madame D’Arblay, the author. The poet John Keats fell in love with Fanny Brawne. Jane Austen had a sister-in-law named Fanny, of whom she was very fond.

Still, there's no denying that Fanny Murray was one of the most famous courtesans of the 18th century and maybe she inspired the creation of Fanny Hill, the protagonist of Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Her own life was the subject of a 1759 memoir. But if “Fanny” inevitably brought lady parts and prostitution to the readers’ minds, as Heydt-Stevenson suggests, it is difficult to understand why so many authors chose the name for their singularly virtuous and virginal characters. Fanny Hill the prostitute is just one of dozens of fictional Fannies. There are Fannies in novels, plays, and poems. There are fatherless Fannies, faithful Fannies, friendless Fannies.

If you asked any well-read person today to name books in which the main character is named “Fanny,” The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure might well come to mind. It might be true today that the name "Fanny" is suggestive, but in Austen’s time, there were plenty of fictional Fannies who were as pure as the driven snow. Except for Fanny Price, Fanny Hill, and a few others--like Fanny Dashwood in Sense & Sensibility--these other fictional Fannies have largely been forgotten. The following examples will also illustrate attitudes toward chastity, marriage, and prostitution in the novels of the time, which is the larger topic I’m exploring here.

"Before," 1736, William Hogarth As Pure as the Driven Snow

"Before," 1736, William Hogarth As Pure as the Driven SnowLet’s start with Fanny Goodwill, the faithful sweetheart of Joseph Andrews in Henry Fielding’s The Adventures of Joseph Andrews (1742): In this satirical romp of a novel, Fanny is rescued from a ravisher, rejects a seducer, and comes to her marriage bed as a virgin.

In The Clandestine Marriage (1766), a play by Colman and Garrick, the cynical gold-digging sister's name is Betsey, the heroine's name is Fanny. She marries for love, not money.