Lona Manning's Blog, page 13

December 19, 2022

CMP#123 Of Cupids and Chimneysweeps

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

CMP#123 Of Cupids & Chimneysweeps: Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

CMP#123 Of Cupids & Chimneysweeps: Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid

Illustration from an 1875 joke book I'm going to assume that if you're reading this post you've read Jane Austen's novel Emma, and you know that "Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid" is a riddle that Mr. Woodhouse tries to recollect. (You can also check at the bottom of this post for a refresher about the role the riddle plays in the novel.) You probably also know that Austen scholars have pored over and debated every aspect of her novels, including this seemingly-inconsequential riddle.

Illustration from an 1875 joke book I'm going to assume that if you're reading this post you've read Jane Austen's novel Emma, and you know that "Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid" is a riddle that Mr. Woodhouse tries to recollect. (You can also check at the bottom of this post for a refresher about the role the riddle plays in the novel.) You probably also know that Austen scholars have pored over and debated every aspect of her novels, including this seemingly-inconsequential riddle.My research and conclusions about this riddle are now published in the 2022 Jane Austen Society of North America journal, Persuasions online.

But—it's just a riddle, for pete's sake, and only one stanza of it appeared in Emma. (See after the break for the full poem). Why does a riddle deserve so much scrutiny? Allow me to explain...

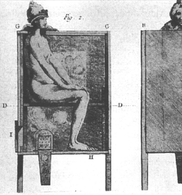

The mercury fume cure--like sitting in a toxic chimney An Obscene Meaning?

The mercury fume cure--like sitting in a toxic chimney An Obscene Meaning?The Kitty riddle leads the reader into thinking the solution is "Cupid" when the answer is actually "chimneysweep." But according to scholar Jillian Heydt-Stephenson, it's really an obscene poem about a man with venereal disease. Here is Kristin Flieger Samuelian succinctly summarizing Heydt-Stevenson’s interpretation in the 2004 Broadview Press edition of Emma:

"[T]he speaker, infected with venereal disease (“a flame I still deplore”) contracted either from Kitty (Kitty and Fanny were common names for prostitutes,) or, alternatively from the prostitutes he is driven to after rejection by the chaste (“frozen” Kitty)—seeks the aid of the “hood-wink’d boy” in effecting a cure… intercourse with a virgin (suggested by the line, “each day some willing victim bleeds”)."

In addition, the second stanza is said to refer to the mercury fume cure for

syphilis, pictured here.

Heydt-Stevenson contends Austen understood this hidden meaning perfectly well and intended for the riddle to establish the themes of Emma: “Austen interweaves into her novel the same topics that the riddle introduces, such as prostitution, venereal disease, and the double standard.”

Hang on, some of you might be saying, I must have missed those parts in Emma.

That may be, but Heydt-Stevenson's interpretation of the riddle has been widely accepted in academic circles,

Kitty, a fair, but frozen maid

Kitty, a fair, but frozen maidKindled a flame I still deplore;

The hood-wink’d boy I call’d in aid,

Much of his near approach afraid,

So fatal to my suit before.

At length, propitious to my pray’r,

The little urchin came;

At once he sought the midway air,

And soon he clear’d, with dextrous care,

The bitter relicks of my flame.

To Kitty, Fanny now succeeds,

She kindles slow, but lasting fires:

With care my appetite she feeds;

Each day some willing victim bleeds,

To satisfy my strange desires.

Say, by what title, or what name,

Must I this youth address?

Cupid and he are not the same,

Tho’ both can raise, or quench a flame--

I’ll kiss you, if you guess. A few months ago, I wrote a series of posts taking issue with Heydt-Stevenson's theories. But her arguments centering on Kitty a Fair but Frozen Maid required a deeper dive. I thought her interpretation of the riddle was doubtful on its face, and wondered if I could build a fact-based case that this is simply a riddle about a cupid and a chimneysweep. If the interpretation of the riddle is unsound, then the theory built upon it is moot.

How did I research and test Heydt-Stevenson's theories about the riddle? I applied my six critical questions, questions that I write about in more detail here. Six questionsFirst, is the scholar's theory supported or contradicted by Austen's text? For example, does the text of Emma support the idea that Mr. Woodhouse is a syphilitic old libertine who wants to recount an obscene riddle to Emma and Harriet?Secondly, is the thing that the critic points to as being unique or noteworthy, in fact something that other authors did too? In this instance, Heydt-Stevenson thinks the Kitty riddle contains violent and disturbing language therefore it must be about a disturbing topic. So the obvious question to ask is: did other poets of that era use "flame," "victims," or "bleeding" to talk about Cupid and his darts, rather than venereal disease? Has this poem been studied in context?Thirdly, does this theory consider probabilities? Is this theory remotely plausible given the times Austen was writing in? For example, would she have referenced having sex with virgins to cure venereal disease in a novel marketed to parents choosing novels for their daughters?Fourthly, if this interpretation represents Austen's true meaning, why did it take 200 years to uncover? Is there any prior commentary about this riddle? What is the publication history of the riddle? Does the publication history support or contradict the theory that the riddle was regarded as a bawdy or obscene?Fifthly--and this may seem counterintuitive to the third question--is the radical idea Austen supposedly hints at spoken of openly in other novels? For example, in prior posts I have demonstrated that many authors wrote about slavery, so the theory that Austen had to be oblique in Mansfield Park is not supported by the written record. In this case, Heydt-Stevenson thinks Austen is opposed to marriage, and compares it to prostitution, but did so very obliquely. Did other authors protest the institution of marriage?Sixth and last, can the interpretation be tested or is it unfalsifiable? Is the theory, in short, pure speculation presented as fact? Is the theory influenced by presentism, i.e., the beliefs and attitudes of modern times? The results of my research are laid out in the Persuasions article, while below are some additional digressions that didn't make it into the article...

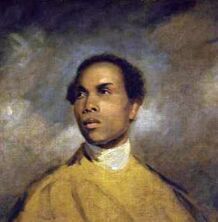

Cupid as a Link Boy Cupid as a Cultural Figure

Cupid as a Link Boy Cupid as a Cultural FigureThe Georgians often referenced Cupid, the son of Venus, in their poetry, plays and novels. Cupid is still around today as a symbol of love, recognizable by his wings and his bow and arrow. Earlier versions of Cupid also had him carrying a torch and wearing a blindfold. A 1729 guide to the Greek and Roman gods says: “Cupid is naked because Lovers delight to be so. Cupid is a boy because he is void of Judgment… and he is blind, because a Lover does not see the Faults of his beloved Object, nor consider in his Mind the Mischief proceeding from that Passion."

The "hoodwink'd boy" in the poem is a reference to Cupid's blindfold and to a chimney-sweep who sticks his head up the hood of a chimney.

Sir Joshua Reynold's portrait at left is of a "link boy" --a little street urchin who was hired to walk ahead of carriages and help drivers find their way through the dark city streets. Reynolds pictures him as Cupid because he is carrying a torch.

Of Chimney fires

Of Chimney fires Kitty’s roaring fire sets the soot in the chimney on fire. Did Kitty do something wrong when she built her fire? The original readers of the riddle understood how Kitty and Fanny built different kinds of fires. In The Domestic Revolution (2020), historian Ruth Goodman discusses the properties of various types of firewood. Hazel wood gets the fire going quickly in the morning. Ash is “the superstar of firewood… which burns beautifully and fairly cleanly even when quite green.” Oak is more long-lasting and gives the fire “staying power,” but it’s slow to get going. Oak, then, is your choice for a "slow but steady" fire.

Austen's contemporaries grew up in an age when relying on a fire for heat, cooking and light was a daily reality. For what it's worth, my family experienced a chimney fire when we lived in South Korea in the late 1950's. My mother was home with two small children when she realized the house was on fire. Without a telephone, she grabbed my sister and me and headed for the neighbor's house, then ran to nearby Yonsei University where my father was teaching. He and his students raced to the house and started throwing all our possessions out the windows before the fire engulfed the upper storey.

18th-century folk knew that sap “bleeds” from uncured firewood. A 1670 treatise published by the Royal Society of London described the behaviours of different species of wood when exposed to heat: “Poles of Maple, Sycamore and Walnut, cut down in open Weather, and brought within the Warmth of the Fire, did bleed in an instant…. Maple and Willow-poles bleed and cease at Pleasure again and again, if quickly withdrawn and balanced in the Hand." Hence, the reference in the poem to bleeding victims refers both to the victims of love and to the fuel throw in the fire.

We might assume that Kitty and Fanny used coal for their fires as most Londoners did at this time. Goodman notes “the chimneys used while burning coal are… at a higher risk of catching fire than those used while burning wood." Coal still required wood kindling to get it going, so when Kitty "kindled a fire," she might have used some wood kindling to ignite her coal. Coal fires produce dirty, tarry, black smoke and households that used coal required chimney-cleaning several times a year.

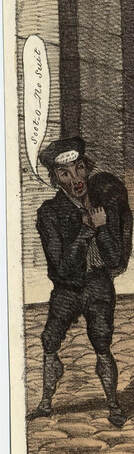

"Of his near approach afraid" Of chimneysweeps and soot

"Of his near approach afraid" Of chimneysweeps and sootThe job of cleaning the chimney often fell to little boys, often orphans taken out of the poorhouse and "apprenticed" to chimneysweeps by parish authorities. The idea of serving an apprenticeship to learn an actual trade was a farce, as there was little to learn about the job, and as soon as a boy was too big to fit up the chimney, he was out of a job. The work was miserable and unhealthy and chimney-sweeps lived, worked, and slept perpetually covered in grimy soot. In the cartoon at left, a clergyman is startled by clouds of soot and the sudden appearance of a black imp in his fireplace.

The soot was collected and sold as fertilizer. In the illustration above, the sweep is crying "Soot O -- no Suit," an indication that the pronunciation of "soot" and "suit" in London at this time was similar enough that people could make puns on the words ("so fatal to my suit before.") This is a detail from a political cartoon about a couple who were suspected to be living together without benefit of clergy.

One more thing

One more thingIn Romania, the chimneysweep is associated with luck. In some extremely improbable tales , the sweep is connected with good fortune in love and so chimney-sweeps are invited to weddings. These Romanian stamps certainly indicate a cultural link between Cupid and chimneysweeps. Is this just a coincidence, or is there an underlying connection between cupids and chimneysweeps that extends further back in literature than the Kitty riddle? I have found a third century Greek poem about Cupid and fireplaces, but that's not quite the same as Cupid and chimneysweeps.

How the Kitty riddle is used in Emma

How the Kitty riddle is used in EmmaIn volume I, chapter 9 of Jane Austen’s Emma, the heroine’s protégé, the sweet but dim-witted Harriet Smith, starts collecting “all the riddles of every sort that she could meet with, into a thin quarto of hot-pressed paper…. ornamented with ciphers and trophies."

Austen lets us know that collecting riddles is a trivial pastime which the girls choose to pursue instead of reading The Theory of Moral Sentiments in their leisure hours. “[Emma’s] views of improving her little friend’s mind, by a great deal of useful reading and conversation, had never yet led to more than a few first chapters, and the intention of going on to-morrow… and the only literary pursuit which engaged Harriet at present, the only mental provision she was making for the evening of life, was the collecting and transcribing all the riddles of every sort that she could meet with, into a thin quarto of hot-pressed paper, made up by her friend, and ornamented with ciphers and trophies."

Austen adds with mock seriousness: "In this age of literature, such collections on a very grand scale are not uncommon.”

Emma’s father, the fussy old “valetudinarian” Mr. Woodhouse “can only recollect the first stanza” of “Kitty, a fair but frozen maid” but he repeatedly assures Emma and Harriet that it is “very clever." Emma tells him that she and Harriet have already transcribed the riddle. “Yes, papa, it is written out in our second page. We copied it from the Elegant Extracts. It was Garrick’s, you know.”

Mr. Woodhouse nevertheless persists in trying to remember the riddle.

What does this passage tell us about Mr. Woodhouse? More thoughts on that later. More background: Examples of 18th century love poetry which use "flames," "bleeding," "victims," etc.

The Kitty riddle, its authorship and variations on the riddle Previous post: I get interviewed! Next post: Riddling with the Georgians

Published on December 19, 2022 06:00

December 11, 2022

CMP#122 Talking about research!

CMP#122 Interview for Regency History I've long been a fan of the Rachel Knowles's

Regency History blog.

It's a great reference for writers and others wishing to know more about the Regency period. I went to her blog especially when I was doing research for my second novel and trying to figure out various walking and riding routes through London.

CMP#122 Interview for Regency History I've long been a fan of the Rachel Knowles's

Regency History blog.

It's a great reference for writers and others wishing to know more about the Regency period. I went to her blog especially when I was doing research for my second novel and trying to figure out various walking and riding routes through London. Rachel's husband Andrew Knowles recently inaugurated a series of YouTube author interviews to share the love of all things Regency and to trade researching know-how. I was able to get in on the ground floor of the interviews and had an enjoyable chat with Andrew, me from my little office in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, and he from England... We got on to some of my favourite research topics, as well as discussing: avoiding anachronisms and historical errors in our writing, and why do we care so much about that, and should we let a few anachronisms distract us from enjoying historical fiction? Anyway, it's great of Rachel and Andrew to reach out to the writing community to get some conversations going like this, which I think will benefit new writers wondering how to get started with their research, a task which can be daunting.

Previous post: An early Austen fan

Published on December 11, 2022 13:50

December 5, 2022

CMP#121 The first Austen book club

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "Six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#121 An Early Austen Fan

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "Six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#121 An Early Austen Fan

Jane Austen's Regency World Nov/Dec 2022 A slightly misleading post title, but I hope I will be forgiven. I was excited to come across a discussion about Jane Austen's novels in an 1829 novel by Mary Jane Mackenzie and I shared it with Jane Austen's Regency World magazine. My article appears in the

November/December 2022 issue.

Jane Austen's Regency World Nov/Dec 2022 A slightly misleading post title, but I hope I will be forgiven. I was excited to come across a discussion about Jane Austen's novels in an 1829 novel by Mary Jane Mackenzie and I shared it with Jane Austen's Regency World magazine. My article appears in the

November/December 2022 issue.

I became very interested in researching the life of the author, Mary Jane Mackenzie, and made some surprising finds which I hope to share in the near future. It's always fun to discover a completely forgotten author.

Mary Jane Mackenzie wrote two novels and an unknown number of short stories, but I don't predict a resurgence of popularity for her work because her writing is highly didactic and overtly Christian. Modern academia will not be interested in this writer unless they decide that she was queer, on account of the fact that she lived the latter part of her life with her "intimate friend" Harriet Auber.

Mackenzie was obviously well read. I've never seen a writer, female or not, drop so many literary and classical allusions into her characters' dialogue as she does. Her 1820 novel Geraldine opens with a conversation between a husband and wife. Over a few pages, the wife refers to a ‘veiled prophet,’ Horne Tooke, Johnson, Lowth, Mrs. Shandy, Griselda, ‘two stars kept their motion in one sphere,’ ‘bestow her tediousness,’ Glumdalclitch, and ‘sonnet to his mistress’s eyebrows.’ (How many did you recognize? I only got 5 out of 10). Mary Jane Mackenzie, whatever her merits as a writer, wasn’t shy about sharing her erudition. She presumes her readers will understand what a reference to the "Cave of Trophonius" is about.

The characters in Geraldine also debate about the theatre, poetry, music, whether French cuisine and music is better than English, and religion.

Whether or not she ever gets an entry in a reference guide to British writers, Miss Mackenzie had the good taste and discernment to be an early Austen fan, and in her novel Private Life the heroine tries to set an addled clergyman's widow straight on which of Austen's novels had a character named Mr. Knightley. The passage is delightful (perhaps the best part of the novel) and you can read it here.

Previous post: Jane Austen and religion

Published on December 05, 2022 07:14

October 23, 2022

Book Review: Fashionable Goodness

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

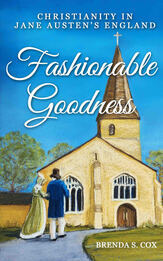

Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen's England, by Brenda S. Cox

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen's England, by Brenda S. CoxBook Review

Often we describe an engrossing book as being "unputdownable." But sometimes you come across a book that you put down so you can think about what you just read. Then you pick it up again, and again. That's the way I enjoyed and lingered over Brenda S. Cox's new book Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen's England. And I know I will return to this book again in the future.

Often we describe an engrossing book as being "unputdownable." But sometimes you come across a book that you put down so you can think about what you just read. Then you pick it up again, and again. That's the way I enjoyed and lingered over Brenda S. Cox's new book Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen's England. And I know I will return to this book again in the future.Cox has thoughtfully, even ingeniously, designed her book for maximum clarity and ease of reference. It begins with a basic overview of the nuts and bolts, shall we say, of the Church of England in Austen's time. Don't know a rector from a vicar? Don't know what a curate does? What's an "advowson"? Cox explains these and other church-related terms in engaging and clear prose. (She also provides a handy glossary).

Cox explains things that Austen's contemporary readers would have known all about: how a clergyman might get a "living," the role he played in society, and the basics of the Anglican church service.

Cox moves on to discuss the influence of the church more broadly, with frequent references to how Austen's Christian faith is reflected in her novels and in her private letters... The title, "Fashionable Goodness," alludes to churchgoers who—as Mansfield Park's Mary Crawford slyly suggested—go to church: "starched up into seeming piety, but with heads full of something very different." In Austen's lifetime, the United Kingdom saw a rise of evangelicalism, a movement to replace lip-service to religion with active, devout, faith. Fashionable Goodness gives a valuable overview of the various "dissenting" or non-conformist factions and how their beliefs differed from mainstream Anglicanism. Scholars have long debated about how Austen herself felt about the evangelicals, because she both criticizes and praises them in her few surviving letters. Cox puts Austen's remarks into their social and historical context.

Religious belief touched on everyday life, of course, including debates around charity and social class. Cox's chapters on the social ills of the Regency are mostly told through the biographies of notable people such as Hannah More, Elizabeth Fry and William Wilberforce, who educated the poor, reformed the prison system, and fought to end the slave trade. Cox shows that, again and again, it was ardent Christians who were the driving force behind these and other fundamental reforms. For example, Thomas Gisborne, author of Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex, doesn't get much love today, but he "promoted laws limiting days and hours of factory work for workers' spiritual good and physical health."

Jane Austen attended Chawton Church while she was writing or rewriting her novels. Her brother Henry, who became an Evangelical clergyman, served as curate here in 1816, earning 52 guineas a year.Photo © Brenda S. Cox, 2022 Throughout, Cox connects her themes to Austen's writing, to what her characters do and say and to what Austen says about them. She shows how Austen is more subtle in expressing her Christianity than many of her contemporaries, but her faith and her beliefs are there in everything she wrote. Remember Austen's description of Sir William Elliot as "a foolish, spendthrift baronet, who had not had principle or sense enough to maintain himself in the situation in which Providence had placed him"? Cox demonstrates that the word "principle" carries more weight than we might realize.

Jane Austen attended Chawton Church while she was writing or rewriting her novels. Her brother Henry, who became an Evangelical clergyman, served as curate here in 1816, earning 52 guineas a year.Photo © Brenda S. Cox, 2022 Throughout, Cox connects her themes to Austen's writing, to what her characters do and say and to what Austen says about them. She shows how Austen is more subtle in expressing her Christianity than many of her contemporaries, but her faith and her beliefs are there in everything she wrote. Remember Austen's description of Sir William Elliot as "a foolish, spendthrift baronet, who had not had principle or sense enough to maintain himself in the situation in which Providence had placed him"? Cox demonstrates that the word "principle" carries more weight than we might realize.  "The poor man at his gate:" The father is on crutches, probably because of a work injury. Therefore this family qualifies as "the deserving poor" who should be helped. Christians appealed to the privileged to help the poor. Austen is also referring, sardonically or not, to the wide-held belief that God ordained everyone's station in life. As the 1848 hymn, All Things Bright and Beautiful, affirmed:

"The poor man at his gate:" The father is on crutches, probably because of a work injury. Therefore this family qualifies as "the deserving poor" who should be helped. Christians appealed to the privileged to help the poor. Austen is also referring, sardonically or not, to the wide-held belief that God ordained everyone's station in life. As the 1848 hymn, All Things Bright and Beautiful, affirmed: The rich man in his castle

The poor man at his gate

God made them, high or lowly

And ordered their estate.

Cox acknowledges that our modern values do not always align with the Regency worldview. The purpose of this book is not to excuse the past—and certainly Cox doesn't hold up the past merely to criticize it. This book explains the past and shows how some of the reform movements begun in the Regency era are still active in the world today.

Cox covers all this and more in a concise, information-packed, and readable style, drawing on scholarly as well as contemporary sources. She brings it all alive with the everyday voices of people from the Regency era. Fashionable Goodness looks at the bigger picture of religion in Austen's England; how people reconciled their faith with new discoveries in science, or the fear that teaching the poor to read would lead to social unrest à la the French Revolution. (There's a delicious quote from the Duchess of Buckingham, who complains that the Methodists, with their insistence that everyone is a sinner before God, are impertinent and disrespectful to their betters.)

Finally, we learn how the moral crusaders of the Regency led into the Victorian era, and how women, inspired by their faith and the desire to help their fellow men, joined together to work at the forefront of social reform.

Recommended!

Fashionable Goodness provides a key to understanding Austen's world--you will see how her values are reflected in her characters and her plots. If you read and re-read Austen, this book will enhance your enjoyment and understanding. If you're a devoted Austenite, you'll love this book, and if you aspire to write Austen-inspired fiction that is true to its source material, Fashionable Goodness is an invaluable source. Where to Buy:

Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England is now available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

About the author:

About the author: Brenda S. Cox has loved Jane Austen since she came across a copy of Emma as a young adult; she went out and bought a whole set of the novels as soon as she finished it! She has spent years researching the church in Austen’s England, visiting English churches and reading hundreds of books and articles, including many written by Austen’s contemporaries. She is a popular speaker at Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA) meetings (including three AGMs) and her articles have been published in Persuasions On-Line (the JASNA journal). She contributes to the blog Jane Austen’s World and her own blog is Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen. Now that her book is finished and launched, Brenda says: "I hope to go back to writing the novel I originally set out to write, but we shall see what happens! Writing is my fourth career, after chemical engineering, homeschooling my children, and training people in learning languages." Other authors

Inspired by Brenda's book, I've added a new category— "Religion in Austen" —which will take you to posts which touch on the subject in this blog. There were many authors who were more didactic and openly preachy than Austen. I discuss some of them in previous posts, such as the Rev. James Thomson , Medora Gordon Byron, and of course Hannah More.

Regardless of one's background, personal beliefs, or religious traditions, I think knowledge of the basics of the Anglican faith is useful (to say the least) for understanding Austen's novels and her world view.. A future post will look at how Methodists were portrayed in the novels of the long 18th century. It was quite a surprise to me, since my Methodist ancestors were the all soul of respectability! I especially enjoyed Brenda's chapter on church music. Her explanation about fitting the lyrics to the meter made me understand why the Methodist hymns of my childhood go bone-deep in my memory.

Published on October 23, 2022 04:00

October 2, 2022

CMP#120: The Love of a Good Woman

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

Echoes of Austen: The love of a good woman

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory

post is here.

Echoes of Austen: The love of a good woman

Dan Stevens as Edward Ferrars Elinor Dashwood might be ready to forgive the man she loves for not telling her he's engaged to Lucy Steele, but modern academics are not prepared to let Edward Ferrars off the hook. They think he’s , deceitful at worst, and Dr.

Helena Kelly

thinks there is a Freudian connotation to his destruction of the “sheath” and the scissors in Chapter 48. Interestingly, a speaker mentioned Kelly’s interpretation at the recent JASNA conference and raised a laugh amongst the large audience of devoted Janeites, an indication that devoted and well-educated Austen fans are not necessarily in accord with the modern academy.

Dan Stevens as Edward Ferrars Elinor Dashwood might be ready to forgive the man she loves for not telling her he's engaged to Lucy Steele, but modern academics are not prepared to let Edward Ferrars off the hook. They think he’s , deceitful at worst, and Dr.

Helena Kelly

thinks there is a Freudian connotation to his destruction of the “sheath” and the scissors in Chapter 48. Interestingly, a speaker mentioned Kelly’s interpretation at the recent JASNA conference and raised a laugh amongst the large audience of devoted Janeites, an indication that devoted and well-educated Austen fans are not necessarily in accord with the modern academy.Like it or not, Edward Ferrars occupies the post of the hero for Sense and Sensibility. Flatly declaring that he is not a hero confuses and muddles the entire novel. Plenty of people are “meh” about the Colonel Brandon/Marianne pairing, and if we also conclude that the guy who marries Elinor at the end is a wimp, a liar and a pervert, where does that leave the message of the book and where does that leave the reader?

I thought you might be interested in knowing about Coraly, an 1819 novel whose hero is a blend of Edward Ferrars and Colonel Brandon. The heroine in this novel unquestionably is stronger than the hero, especially in her Spartan adherence to a rigid moral code. Yet, she loves the hero, he’s her guy, and they get married. So maybe our expectations for heroes are not quite the same long 18th century expectations. Something to ponder...

Dad's a kindly old clergyman Coraly's backstory

Dad's a kindly old clergyman Coraly's backstoryThere are other echoes of Austen in Coraly. There is a minor character named Middleton and the opening starts out like Emma. You have to wonder. Overall though, the plot has much more drama than you’ll find in an Austen novel.

Coraly did not sell out and more than a hundred volumes of the 500 volume printing were remaindered. It looks like the author only got 35 pounds at best for her efforts. Maybe it failed to sell out because the La Belle Assemblée, while praising the book, gave away the entire plot in its review. Anyway, our heroine Coraly is “an excellent and almost faultless character.” The reviewer thought she was “not unnaturally faultless,” but that’s a matter of opinion, I suppose. She’s quite a gal, and the book centers on her hardships and struggles and how she overcomes them while helping others. This leaves the hero with little to do.

But before we meet the hero, we have to arrange matters so that Coraly, who has already lost her mother at an early age, loses her father and becomes an orphan. “To say she had attained her eighteenth year without ever having felt sorrow, real or imaginary, would be to talk of impossibilities; but she did attain it without feeling what, in reality, deserved that name.”

Dad is a clergyman and he’s also well-off financially. He gives Coraly an excellent education. But he falls ill and father and daughter go to Bristol to see if the spa waters will help him. I might as well let the La Belle Assemblée explain what happens: Reverend Fitzharland “meets with Lady Mary de Montford, a most amiable and lovely woman, the widow of a nobleman, and who, in Fitzharland’s youth, was his first love. Lady Mary is accompanied by her son, who realizes all the heroes, in his appearance, of whom Coraly has been used to read of in her favourite romances.”

The Reverend and his daughter and his long-lost love and her son spend a lot of time together, and soon Lady Mary promises to take care of Coraly after the Reverend dies, which he does.

Coraly’s father is scarcely deposited in his grave when the successor to the living shows up at the parsonage with his friend and “without any ceremony entered.”

Coraly’s father is scarcely deposited in his grave when the successor to the living shows up at the parsonage with his friend and “without any ceremony entered.”“What a cursed dull old place!” Coraly hears him exclaim. “I have half a mind to give it up at first sight. Can you conceive such an infernal bore, as to be obliged to be here or a certain time every year of one’s life? Such a sacrifice for a paltry nine hundred a year!”

Coraly is shocked at this clergyman, who clearly plans to leave all the work of the parish to an underpaid curate, so unlike her virtuous late father. He is the kind of clergyman that Henry Crawford assumes Edward Bertram will be in Mansfield Park. Coraly herself, having no place to live, has to leave behind the parishioners for whom she has cared so diligently and go visit her vulgar cousins, the wealthy-through-trade Mandevilles. Emmeline Mandeville is angling for a society marriage, even if she has to marry a fusty old baronet. The heroine is delighted with a tour of the baronet’s castle, while Emmeline is bored. If she marries the baronet he “will have something to do to make that castle a fit place for her to live in. In the first place, all those avenues must come down; and those frightful clump of great overgrown trees; and as to the house, heaven knows how that is to be set about…”

Shades of Sotherton and Norland! So again we see it was not uncommon to portray people who didn’t like the traditions of Merrie Olde England as being mercenary and shallow. Unsurprisingly, the baronet prefers Coraly but she turns him down because she doesn't love him.

Coraly is much happier living with Lady Mary, her father’s old flame, than with the Mandevilles, but she gets the impression that her son Major De Montford avoids her company—can he dislike her? Like Colonel Brandon, the major has “a fixed and settled melancholy over his countenance and manners.” And he’s got a secret. The mystery deepens when Coraly attends the opera and accidentally bumps into a vulgar, painted, woman who drops a locket at her feet. It's a miniature of the Major!

As the major eventually confesses to Coraly—he’s married! To that floozy!

While visiting an acquaintance on the continent, he was given some drugged wine and when he woke up, he was told he had made improper advances to the daughter of the house, a girl he didn’t much care for. As he explained, he was accused of wounding “the delicacy of a virtuous woman, who well acted the part of innocence… I was completely deceived and blinded, and I offered what I conceived the only reparation in my power, my hand to the daughter of my injured host.” Like Edward Ferrars, De Montford is stuck in a situation he can’t fix, and that limits his heroic potential.

When Lady Mary dies in her turn, Coraly needs a new place to live--because she can’t live with the major, obviously--so she shares lodgings with Mrs. Stanley, a gentlewoman from the West Indies who has fallen on hard times. Money Changes Everything

The author editorializes about how money makes the world go around. Poor Mrs. Stanley, struggling to provide for her children, “had thought most liberally, most benevolently of human nature; and it was with many a bitter tear, and many a grating sigh, she was compelled to acknowledge, that, with the exception of a few, a very few honourable instances, money is the main spring of the large majority of mankind: that with it you are every thing—without it, nothing."

One is reminded about Emma’s musings on the difference between Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Campbell: “The contrast between Mrs. Churchill’s importance in the world, and Jane Fairfax’s, struck her; one was every thing, the other nothing—and she sat musing on the difference of woman’s destiny…”

Coraly is not “nothing” because she inherited money. Though she can't have the man she loves, she builds meaning into her life by helping Mrs. Stanley, with the help of Mrs. Stanley’s long-lost West Indian aunt, Mrs. Cunningham who pops up out of nowhere. Strange how you never see both of them in the same place, though.

The major, as I mentioned, has nothing to do but mope around in despair because even if he gets a divorce, Coraly won’t marry him. Divorce is not sanctioned by the Church of England. “Coraly had told him, under such circumstances she could never be his. He knew her delicacy, her purity, her undeviating rectitude; and if in a moment of passion he wished her less strict, he was compelled, when reason resumed her power, to confess he never had loved her as he did, had she been any thing but what she was…”

With time on his hands, our hero pursues an affair with an artful, designing widow, and he although he professes to love Coraly, he neglects her in favor of the widow. Plus he manages to get himself wrongfully accused of murdering his wealthy brother Lord Valhurst (a name also used by Fanny Burney). Coraly’s court testimony helps him out of that scrape. Then the major’s dissolute and conniving wife dies, so now they can get married, right?

Not yet! The artful widow arranges to have Coraly kidnapped and locked up in a house by the coast. She’s locked up for some time, but fortunately she escapes, thanks to a young smuggler who also uses the house, who recognizes her as someone who helped his dear old mother.

De Montford’s contribution to this crisis is to contemplate suicide.

Coraly forgives him for his weakness—suicide is both a crime and a sin—but she “corrected his errors” through her superior piety. The writer quotes the poem “Henry and Emma”:

‘O powerful Virtue!

O victorious fair!

At least excuse a trial too severe;

Receive the triumph, and forget the war’.

English smugglers “[T]he dénoúement of this interesting work may be easily guessed at.”

English smugglers “[T]he dénoúement of this interesting work may be easily guessed at.” There are more amazing coincidences and discoveries before we get to our happy ending. The vulgar Emmeline Mandeville gets her comeuppance when she marries the lazy clergyman and he discovers that her family is broke. (Coraly gives the Mandevilles some of her own fortune.)

(Final spoiler) And, it turns out that the kindly West Indian aunt, Mrs. Cunningham, is Coraly with a wig, face stain and an eye patch! What a gal!

“Yes, De Montford, young, handsome, brave, noble, and accomplished; a scholar, a soldier, regarded by all classes with admiration; with honours and wealth poured on him by an approving sovereign—had let to learn one lesson; he learned it from the gentle, unassuming, pious daughter of the excellent Fitzharland—that a true and genuine sense of religion is above all other advantages, and that without its aid, they are insufficient in the hour of trial and affliction.” (I presume that “they” refers to De Montford’s attributes listed at the beginning of this sentence.)

Novels of this period often contained a disclaimer in the foreword, explaining that the novel does not offend morality and can be safely read by the ladies. The authoress of Coraly saves this disclaimer for her conclusion, and she also mentions “social duties.” This is presumably a reference to Coraly’s many charitable actions but also reminds us of how Elinor Dashwood performs the social duties both for herself and her sister until Marianne sees the error of her ways:

“Should the historian of Coraly live to old age, one recollection only will make her feel proud, and that pride will arise from the conviction, that none of her fair country-women will be worse from the example of her heroine. From the genuine and early inculcated principles of religion, she derived all her virtues; and, by their influence, she won from error the husband of her heart."

Elinor's moral and mental excellence makes Edward protest that Indeed, he is not worthy of her. Austen handles this fact with gentle, ironic humour, not a ringing moral lecture: "in spite of the modesty with which he rated his own deserts, and the politeness with which he talked of his doubts, he did not, upon the whole, expect a very cruel reception. It was his business, however, to say that he did, and he said it very prettily. What he might say on the subject a twelvemonth after, must be referred to the imagination of husbands and wives."

Published on October 02, 2022 20:43

August 15, 2022

CMP#119 "The Negro is Our Fellow Creature"

Thanks to Debatenstein of Twitter for my new logo, "Side-eye Jane Austen"!

Thanks to Debatenstein of Twitter for my new logo, "Side-eye Jane Austen"!This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. CMP#119 Representations of Black Georgians: Laugh When You Can In my last two posts, I reviewed a forgotten 1812 novel about a Black man living in Georgian England.

British novelists, poets, and playwrights played an important role in the long struggle to end slavery. No-one living in the United Kingdom in the late 18th century could pretend not to notice the poems, novels, plays and essays which portrayed the cruelty and horror of the slave trade. Dramatic poems like “The Dying Negro” were intended to awaken the consciences and appeal to the emotions of British readers. A poem for children, written in the cadences of the Old Testament, associated the consolations of religion with the fight against slavery: "Negro woman, who sittest pining in captivity,

and weepest over thy sick child;

though no one seeth thee, God seeth thee;

though no one pitieth thee, God pitieth thee: raise thy voice, forlorn and abandoned one;

call upon him from amidst thy bonds, for assuredly he will hear thee."

Naturally enough—since these poems were intended to raise empathy and spur people to action—these representations of enslaved persons emphasized their suffering and vulnerability. In the famous Wedgewood portrait “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” the enslaved man is pictured kneeling, raising up his shackled arms, pleading for help.

Naturally enough—since these poems were intended to raise empathy and spur people to action—these representations of enslaved persons emphasized their suffering and vulnerability. In the famous Wedgewood portrait “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” the enslaved man is pictured kneeling, raising up his shackled arms, pleading for help.However, Georgian playwright Frederick Reynolds took a different approach—he used the vehicle of comedy, not tragedy, to stress the humanity of people of colour...

Abusive to Zebby, her servant Laugh When You Can

Abusive to Zebby, her servant Laugh When You CanReynold’s play Laugh When You Can debuted at the Covent Garden Theatre in December 1799. A comic farce with a complicated plot involving marital misunderstandings, a thwarted seducer and a love-struck spinster, it enjoyed great popularity and was performed well into the 19th century.

The main plot of Laugh When You Can has to do with Mr. Delville, a man-about-town who plots to seduce the lovely Mrs. Mortimer while her husband is out of the country. He lures her to an inn but she refuses to cheat on her husband. Delville threatens to have his way with her. She is rescued by the light-hearted Mr. Gossamer, who was alerted to her plight by Mr. Delville’s servant.

The clever servant who outwits his master was a familiar stock character in theatre—not just in England, but all around the world and as far back as ancient Greece. But Reynolds added a twist to the familiar story.

The servant’s name is Sambo and he is a black man. Despite his stereotypical slave name, Sambo defies the typical caricatures of the times. Black characters in books and plays often spoke using a crude dialect and referred to themselves in the third person, as we saw with the novel Yamboo. The slave Zebby in the novel The Barbadoes Girl (1816) is abused by her spoiled young mistress, but speaks up in her defense: “Sir, me hopes you will have much pity on Missy, she was spoily all her life, by poor massa, and when Missy pinch Zebby, and pricky with pin, massa say only – poo! poo! she be child! naughty tricks wear off in time.” In Elizabeth Helme’s Modern Times (1814) another spoiled girl orders her slave Juba to wade into the ocean to retrieve her riding crop before it drifts away. He balks: “Me fear, missy, something matter. Dog no go—he always please with water.” Juba is ordered into the surf where he is bitten in half by a “sea monster.”

Isabella Mattocks No Pidgin Here

Isabella Mattocks No Pidgin HereIn marked contrast, Sambo in Laugh When You Can speaks the King’s English, the same as the other characters. Historian John A. Hodgson points out that Sambo is “virtuous, well-educated, well-spoken, and thoughtful.”

Sambo carries himself confidently and intercedes in the other character's lives several times. He scornfully turns down a bribe to falsely testify that Mrs. Mortimer has been unfaithful to her husband. Because he has read his employer’s law books, he saves Mr. Delville from being arrested for debt. He recounts: “there was a flaw in the indictment—they arrested him in the wrong county!... The writ was made out into Middlesex; and we, being the other side of the bridge, were in Surry, you know!—so we snapp’d our fingers, and defied them!”

Reynolds uses Sambo as a device to criticize English society. He scolds Mr. Delville with: “the natives of my country are all very healthy, and for two simple reasons—first, because we’ve no doctors, and next because we’ve no such enlighten’d disorders as ingratitude, false friendship, seduction!” He tells Mrs. Mortimer she shouldn’t have allowed Mr. Delville to get her alone: “Begging your pardon ma’am, in your own thoughtlessness – don’t be angry – but the world judges by appearances.”

Reynolds tailored the parts in his play to the comic abilities of the Covent Garden regulars. Isabella Mattocks had been a member of the troupe for over thirty years. She was cast as Miss Gloomly, a writer of sentimental novels. When Dorothy, her flattering maid, describes her novels as “moral and entertaining,” Miss Gloomly angrily retorts: “Entertaining!—why the girl’s mad! –I never wrote anything entertaining in my life! No—all my works are calculated to excite sighs, and tears, and terror, and distress… in the thirty-six volumes I have published, I defy you to produce a single joke.” When another character jokes about challenging the troublemaking spinster to a duel, Sambo agrees: “Challenge her--shoot her and welcome.”

Blackface on the stage

Blackface on the stageActor John Fawcett originated the part of Sambo at Covent Garden. Fawcett looks rather dark-complected in this youthful portrait but other portraits make it clear he is a typical fair-skinned Englishman. During his career, however, he "blacked up" for many roles. Fawcett started his stage career playing the tragic role of Oronooko, an African prince sold into slavery, and he also undertook Othello. But according to the Dictionary of National Biography, Fawcett didn’t shine as a tragic actor and made the switch to comedy. Reynolds appears to have written the role of Sambo to play up Fawcett’s strengths, because the Dictionary says “in representations of bluff honesty and rude manly feeling [Fawcett] had no equal.” Accordingly, Reynolds gave Fawcett lines like: “as it is my duty to serve my master in a good cause, it is my duty to thwart him in a bad one.”

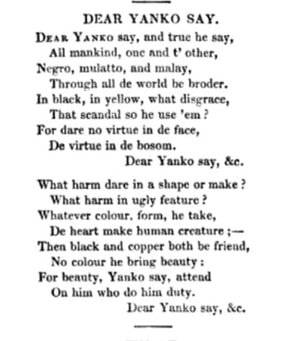

Fawcett was also known for his fine singing voice. Sambo repeatedly sings a comic song by Charles Dibdin, Dear Yanko Say, which declared (albeit in pidgin English) that all men are brothers and that virtue is not to be found in the face, but in the heart. The lyrics are below.

Black servant in livery Does Laugh When You Can have cringe-making dialogue and outdated attitudes? Of course it does, but the character of Sambo was arguably a ground-breaking one. Sambo is not a comic, carefree fool and neither is he a pious Uncle Tom. Since Laugh When You Can is a farce, one-liners abound, and Sambo gets his share. Some of his jokes are made at his own expense as when he says, “and for the falsehood I told about you, ma’am, why ‘twas but a white one, and we blacks tell lies of no other colour.” Or: “it’s a Negro’s business to mind he goes to heaven as well as a white man’s, and we who have so much of the black gentleman in this world, I’m sure must be heartily glad to keep clear of him in the next.”

Black servant in livery Does Laugh When You Can have cringe-making dialogue and outdated attitudes? Of course it does, but the character of Sambo was arguably a ground-breaking one. Sambo is not a comic, carefree fool and neither is he a pious Uncle Tom. Since Laugh When You Can is a farce, one-liners abound, and Sambo gets his share. Some of his jokes are made at his own expense as when he says, “and for the falsehood I told about you, ma’am, why ‘twas but a white one, and we blacks tell lies of no other colour.” Or: “it’s a Negro’s business to mind he goes to heaven as well as a white man’s, and we who have so much of the black gentleman in this world, I’m sure must be heartily glad to keep clear of him in the next.”As well, the specific directions for Sambo's costume ("a white jacket, silver shoulder knot, white waistcoat, glazed round hat, gold band, cockade, boots, and leather breeches"), indicate that he wore elaborate livery, playing into the stereotype that Black people prized finery.

Bluff and manly: John Fawcett out of blackface. British Museum Laugh When You Can was also performed in the United States in the early part of the 19th century. Here, a reviewer in Boston took issue with the character of Sambo. He praised the play as “most pleasing,” with humor and sprightly dialogue. But, the reviewer objected, the play “introduced one character, which has no prototype on earth… a West Indian negro, who talks morality, religion, and law, with more fluency and copiousness than half the lawyers and clergymen of the state.” He declared the character “an outrage upon common sense, and directly opposite to the character of the whole tribe.”

Bluff and manly: John Fawcett out of blackface. British Museum Laugh When You Can was also performed in the United States in the early part of the 19th century. Here, a reviewer in Boston took issue with the character of Sambo. He praised the play as “most pleasing,” with humor and sprightly dialogue. But, the reviewer objected, the play “introduced one character, which has no prototype on earth… a West Indian negro, who talks morality, religion, and law, with more fluency and copiousness than half the lawyers and clergymen of the state.” He declared the character “an outrage upon common sense, and directly opposite to the character of the whole tribe.”The play was better received in England. A reviewer writing in the Monthly Mirror (1798) understood that the portrayal of Sambo was something new on the stage: the “sentiments… put into the mouth” of Sambo “are calculated to prove that the negro is our fellow creature, with moral and intellectual faculties… like those of other men.” The reviewer added, “The tendency of this character must atone for some improbabilities annexed to it. It is certainly good to maintain that a difference of complexion should be considered as the only difference between the European and the African.”

To this reviewer, Reynold’s underlying message was clear: “Fawcett, in the [role of the] black, felt and spoke like a determined enemy to the Slave Trade.” West Indian Fortunes

I should mention too, the sub-plot involving Mr. Gossamer and the girl he loves, because their marriage only comes about because she is a West Indian heiress and owns plantations. Mr. Gossamer tricks her uncle into thinking the plantation has been destroyed by a hurricane--thinking his niece is now a pauper, he quickly gives permission for her to marry, to have her off his hands. But her plantations are just fine and she gets her happy ending with Mr. Gossamer.

Laugh When You Can was a popular success for its author, and it was performed around the country. Jane Austen might have seen the play while she was living in Bath. I think she would have laughed at the character of Miss Gloomly. The Black actor Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) (who also played Othello and King Lear) performed as Sambo at the Royal Coburg Theatre in London in a musical adaptation of the play.

According to a history of the theatre in New York, Laugh When You Can “for half a century remained a favorite with actors and audiences.”

More about blackface in a future post... The song Dear Yanko was reproduced in the best-selling Elegant Extracts. If you can sight read or play, (alas, I cannot), the music for the

song is here.

More about blackface in a future post... The song Dear Yanko was reproduced in the best-selling Elegant Extracts. If you can sight read or play, (alas, I cannot), the music for the

song is here.

For more examples of anti-slavery literature in Austen's time, check here and also here. There was of course, literature produced by anti-abolitionists, including cartoons ridiculing the abolition movement and depicting people of colour in stereotypical fashions.

Timely West Indian fortunes were a frequently used plot device for many an 18th century novel and play. For more, click here.

Hodgson, John A.. Richard Potter: America's First Black Celebrity. University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Ireland, Joseph Norton. Records of the New York stage, from 1750 to 1860. 1866.

Published on August 15, 2022 00:00

August 9, 2022

CMP#118 Yamboo: Slave, Servant, Squire

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#118 Yamboo, or, the North American Slave, conclusion

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#118 Yamboo, or, the North American Slave, conclusion

Black Georgians In

my previous post

, I introduced a now-forgotten 1812 novel entitled Yamboo, or, the North American Slave which is far more explicit than anything you'll find in Austen, the go-to girl for literary discussions about slavery in the long 18th century.

Black Georgians In

my previous post

, I introduced a now-forgotten 1812 novel entitled Yamboo, or, the North American Slave which is far more explicit than anything you'll find in Austen, the go-to girl for literary discussions about slavery in the long 18th century.As explained in my previous post, Yamboo is released from slavery and becomes a loyal and affectionate servant to the Beresford family in New Brunswick. He is introduced to Christianity. He begs to be allowed to accompany Colonel Beresford on a military campaign to India.

Okay, to resume our story....

Colonel Beresford goes missing in battle at Seringapatam. While searching for him, Yamboo discovers a captain left for dead and brings rescuers to carry him off the battlefield. Colonel Beresford remains missing, but Captain Longford survives. Yamboo feels strongly drawn to serve and protect the captain, even though he has a reputation for being a quarrelsome and difficult man. “Is it,” he would sometimes mentally exclaim, “that Yamboo must love everybody who speak kind to him, or why him love Captain Longford so much? Him no like him good colonel, for he swear, scold, almost frighten every one; yet Yamboo feel he must love him, pray for him.”

The captain, likewise, is surprised at the degree of gratitude and affection he feels for Yamboo. And yes, there is a reason for his affinity for the artless servant! When Yamboo tells his life story to the captain as he recuperates, the captain realizes that Yamboo is… is…

Before the walls of Seringapatam Teasers

Before the walls of Seringapatam TeasersOne recurring feature of this novel is that the writer likes teasing us when a plot revelation is on the way.

Anyway, yes, Yamboo is… Longford’s son! Longford is consumed by guilt for his past dissolute life when he learns how much Yamboo suffered when enslaved, but he can’t bring himself to confess this guilty secret.

Colonel Beresford is presumed dead, and the captain takes Yamboo back to England to live with his sister. Longford wants to tell everyone the truth, but “honour and justice were combated by pride and worldly prudence.” He already has one illegitimate (but acknowledged) son, Henry, who is his heir, by a different (white) mother. Asking everyone to acknowledge his mixed-race son is something he can’t bring himself to do.

I’ve referred to Yamboo as the titular character, rather than the main character, because from this point in the novel, the half-brother, Henry Longford, steps up as the villain and dominates the story. This author is not the first writer to create a villain who is more interesting than the hero, of course. Henry Longford is a lying, scheming, cad who breaks girl’s hearts when he isn’t running up huge gaming debts. Yes, the term “vortex of dissipation” Is used.

Henry greatly resents this new servant whom his father is so fond of. He invites Yamboo along on a trip to London, then arranges for him to be kidnapped and impressed into the Navy.

This doesn’t work out so well because, although Yamboo can’t use pronouns properly, he can speak well enough to explain the situation to the captain, who stops off in Portsmouth and gives Yamboo shore leave, while they try to sort out the truth of the matter. While walking along the beach, Yamboo sees a young lady being carried off on a runaway horse; he steps up and rescues her, and who should it be but… Emmeline Beresford, one of the two Beresford girls!

And Colonel Beresford isn't dead, he's been reunited with his family, because he’s been liberated from Tippoo Sultan’s prisons! Now Yamboo’s heart is torn between the two families he loves—who shall he live with and serve?

‘Yamboo but slave, then him know what to do, for him duty leave no choice; now him own heart deceive him; it say,’ looking anxious at Mrs. Beresford and her daughters as he spoke, ‘it say Yamboo must stay here, here only him happy; in a moment it travel far off, see Captain Longord, sick, lame, unhappy; no one do for him what Yamboo do, and then him think Yamboo not live for himself, and he must go to him poor captain: when Yamboo have one masser, him know but to be happy; now him two, love both, and him miserable.’

No longer a servant The Secret Revealed

No longer a servant The Secret RevealedColonel Beresford decides to take Yamboo to Captain Longford to discuss the dilemma. The prospect of losing Yamboo to the Beresfords compels the captain to confess his true relationship to the boy, plus, he credits Yamboo not only with saving his life, but redeeming his soul and making him an active Christian.

‘I was rescued from destruction, nay perdition, for why should I hesitate to own it, and by whom--the child who owed me life, but whom I refused to own, had never seen! Who, with its distressed and wretched mother, I basely neglected, only because they differed from me in complexion…to me he is indebted for the scars which tell the miseries of his infant years... Oh! I know all; I have heard his sad story, wept over his past agonies, would have clasped him to my penitent heart, and told him who he was; but the world triumphed over gratitude and nature’s claims…”

Henry, meanwhile, manages to convince his father that he had nothing to do with the whole kidnapping thing. The captain is deceived into thinking Henry is happy to have an older brother, which “proves how powerfully the ties of nature plead, and will doubtless soften the disappointment of [Henry] resigning to an elder brother privileges he has so long enjoyed; his fortune would have been a handsome one; neither will he have reason to complain of that portion which will still, as a younger brother, fall to his share.”

So Yamboo ceases being a servant and becomes the acknowledged oldest son of the family, sitting down at the breakfast table with the rest of them, dressing like a gentleman, and receiving a generous allowance, which he expends on charity in the village. He starts to receive the rudiments of an education. We get no details of this, but we are told he enjoys reading. At one point, he actually says: “Are you ill, Mrs. Forrester, you look faint; let me help you,” Instead of “Yamboo help Mrs. Forrester.” I don’t know if this was a slip-up on the author’s part, or if Yamboo briefly figured out how to use pronouns.

Yamboo in peril

Yamboo in perilAnyway, the jealous Henry, who has lots of sketchy acquaintances, arranges for a hired assassin to move to the village, posing as an itinerant labourer fallen on hard times. He’s under orders to murder Yamboo at the first opportunity. Yamboo greets the newcomer and his wife and child with his usual generous thoughtful charity. From here, we see Yamboo, due to his good nature, being unaware of the duplicity going on around him. The author does not match the brilliance of the way Austen showed Emma deluding herself about Harriet and Mr. Elton, but we are made aware that something sinister is afoot.

Henry is killed instead of Yamboo. In the conservatory with a gun, like a game of Clue. The circumstantial evidence strongly implicates Yamboo and he's arrested for the murder. He is exonerated when the real killer confesses. Yamboo's innocence is proven, thanks to a string of amazing coincidences including an attempted highway robbery which brings about another unexpected reunion.

By now I was really wondering—if the author is presenting Yamboo as deserving of legal and social equality with English people, does this mean he will fall in love and get married?

No, that’s a bridge too far, isn’t it? We are told that Yamboo adores Emmeline, (the girl he rescued from the runaway horse), but “while her image engrossed his whole heart, he would have deemed it profanation to have breathed her name—of so pure, so exalted a nature was his sentiments towards her.”

And anyway, Emmeline’s engaged to somebody else. Yamboo never marries. He lives out his life as a propertied English gentleman, dedicated to performing kind actions for his fellow man: "and men of worth proudly boasted that he was once their friend." Say what you like about the writing and the portrayal, but the treatment of the issues of race and slavery is far, far, more explicit than you will find in any Austen novel, and is illustrative of the leading role that evangelical Christians played in opposing the slave trade by humanizing Black people. It's also notable that Yamboo is worthy of being a main character in a novel without being the son of an African prince as in Oronooko (1688) or Slavery, or The Times, (1793). He is a "noble savage" without being actually of noble birth.

In addition to the slavery theme, the novel handles the issue of female virtue. There is a subplot where Henry trifles with the affections of a sweet young girl, who is drawn to him but virtuously fights her feelings when she understands how bad his character is. The pure and chaste Louisa, as well as Mrs. Beresford and her daughters, serve as a contrast to the two mothers of Captain Longford's sons, fallen women who are described as "wretched."

General Hunter - pretty easy on the eyes! Strategic Dedication

General Hunter - pretty easy on the eyes! Strategic DedicationAs mentioned in the previous post, the author of Yamboo is unknown, but she described herself as a wife and mother and she lived at least part of her life in New Brunswick.

Yamboo is dedicated to Major-General Martin Hunter, then the military and civil leader of New Brunswick, and the author cannily weaves some of Hunter’s extensive military service into her story. When he was a colonel returning to England from the West Indies, Hunter's ship encountered a hurricane, just as the Beresfords did in Yamboo. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography says: “In 1783 Hunter left Britain for ten years’ service in India. He participated in a number of engagements in the Mysore War, including the decisive night attack in February 1792 on Tipu Sahib’s entrenched camp under the walls of Seringapatam, when he commanded the 52nd and was credited with keeping the commander-in-chief, Lord Cornwallis, from being taken prisoner. In one of the charges of the 52nd, he was severely wounded.”

In an attempt to discover the author's name, I checked the General’s journal and his wife’s letters, available online, to see if either of them mentioned having a book dedicated to him. I could find no leads. Lady Hunter reproduces some poetry dedicated to them by one John Odell but there is no mention of a book. I will add that Lady Hunter’s letters and descriptions of life in New Brunswick are livelier and more humorous than our author’s, whose style tends toward the trite and the ornamental. Ahem: “But even their [felicity] was not always to be uninterrupted; few indeed had been the thorns mingled with those roses which had hitherto strewed their path through life..."

So yes, this anonymous author is not a writer on a par with Edgeworth or Austen. However, modern academia is taken up with contextualizing literature as history, as opposed to focusing on literary merit. Given the current preoccupation with race, this fictionalized portrayal of a black man in Georgian England is deserving of scholarly attention. This BBC podcast explores the lives of Black people living in the United Kingdom during the Georgian era. There were of course some inter-racial marriages, though Yamboo is denied his HEA.

Published on August 09, 2022 00:00

August 8, 2022

CMP#117 Yamboo, or, the North American Slave

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#117 “Soon everybody forget poor black boy:” Hey, what about Yamboo?

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#117 “Soon everybody forget poor black boy:” Hey, what about Yamboo?

Chawton House, the center for early women's writing and former home of Jane Austen's wealthy brother, has made a number of obscure novels

available for study

on their website. You would think that scholars would fall on a novel entitled Yamboo, or, the North American Slave, like a duck on a June bug. But no, they are too busy studying attitudes toward slavery by poring over Mansfield Park. Too bad there are no actual enslaved persons in Mansfield Park and slavery is never discussed, let alone condemned.

Chawton House, the center for early women's writing and former home of Jane Austen's wealthy brother, has made a number of obscure novels

available for study

on their website. You would think that scholars would fall on a novel entitled Yamboo, or, the North American Slave, like a duck on a June bug. But no, they are too busy studying attitudes toward slavery by poring over Mansfield Park. Too bad there are no actual enslaved persons in Mansfield Park and slavery is never discussed, let alone condemned.How about looking at an 1812 novel which actually has an enslaved person as the titular character? Yamboo's anti-slavery message is far more explicit than Mansfield Park and serves as yet another refutation of the notion that authors, particularly women authors, couldn't talk about slavery back then.

Leaving aside the literary merits of the book and focusing on its message, we can say this in favour of Yamboo:The novel strongly asserts the titular character’s humanity.It confronts the issues of racial as well as class prejudice.Yamboo is portrayed as having agency; that is, he acts and is not merely acted upon... All right, we should also mention the cringey stuff, that is, the stuff which might make any self-respecting modern push it aside with disdain:The name "Yamboo." Well, according to scholar Kenneth E. Marshall, the name Yamboo “has been identified among the Mende, Bobangi, and Hausa peoples.”Yamboo consistently refers to himself in the third person and speaks pidgin English, despite living with English-speaking people all his life. At least he speaks, which is more than we can say of Miss Lambe of Sanditon, and look at how much ink has been spilled in speculation about her.He definitely is in the mold of the “grateful negro” and the “noble savage;” that is, he is supernaturally virtuous and exceedingly grateful. His virtuous character is presumably essential to the argument that he is worthy of humane treatment.The novel is told from a Christian viewpoint with a heavy emphasis on conversion and salvation. Yamboo is a child of god who accepts Christianity. As I've mentioned elsewhere, if Jane Austen had evangelical tendencies, that likely means she was in favour of converting heathens like Yamboo. But, as always, my purpose is not to excuse the past, but to explain it. I think this novel deserves some of the attention now being lavished on the famous “dead silence” because it is an authentic representation of attitudes which were prevalent at the time. You don't need to read into a dead silence to surmise what the author is trying to say. In addition, this novel is also one of the earliest novelistic depictions of New Brunswick, so it should be of interest to Canadian scholars in particular.

I can’t find one scholarly discussion of this novel, which makes me question just how sincere scholars even are about the whole “interrogating the past through literature” kick. Why such neglect? And the poor novel never received a review when it came out in 1812, either. Time to rectify this oversight!

Plot spoilers follow:

Plot spoilers follow:Mrs. Beresford and her two little daughters, living in the English colony of New Brunswick, find young Yamboo weeping, “stretched on the damp earth. His tattered clothes too plainly bespoke him the child of poverty; the situation left little room to doubt of his being friendless… He was one of those unfortunate beings, brought into the world only to be stigmatized with the opprobrious epithet [bastard]…. He knew no father; and the wretched mother to whom he owed his being, careless of a mother’s rights, willingly resigned [him to slavery because] she was too idle to work, too proud to beg.”

Nor was this the least of his misfortunes: “Nature had fixed on him an indelible mark; she had given him a heart, that, if known, might have ranked him with the fairest of her sons; but, alas! That heart was enshrined in an ebon casket, and shewed not, in the dark lineaments of his fine features, the workings of a generous and noble mind.” The author goes on to describe Yamboo as being “superior” to his slave-master “save in colour,” because he is superior in natural goodness.

During this time, New Brunswick was part of British North America, sending timber, beaver pelts, and cod back to England, and slavery was legal and there was also a small population of free Blacks.

Yamboo has run away from his master, and “the mother who had abandoned him was now dead,” and only a kindly Indian (that is, a native,) had given him a little food, for “to the houseless child of misery, who will open the door? Again, he was black, and who believes a negro’s story?”

Mrs. Beresford takes Yamboo home. The scars on his back bear testimony to the hardship of his life, but her husband, Colonel Beresford, wants to test Yamboo’s veracity before offering to buy him from his old master. He doesn’t want to take a dishonest servant into his house. This is similar to the story of Pompey in the children’s story, The Rotchfords.

Fortunately, it turns out that the cruel master is dead and the Beresfords resolve to keep Yamboo as a servant. He is doggedly grateful, and begs to never be sent away: “Yamboo no longer a slave! Then what him be, if masser no obliged to keep him? Perhaps get angry, bid him go away, and young misses never beg so hard again for Yamboo; lady, all, all get tired of black boy.”

In addition to his gratitude and devotion, the author emphasizes Yamboo’s innate goodness: “From an infant, he had witnessed every enormity of which drunkenness is capable, in the wretch he called master—had been accustomed to hear only blasphemy issue from lips that knew not how to pray; of religion... Yet the heart thus cast off by every natural tie, bereft of every incitement to virtue, reared, educated but in vice, was incapable of performing a base or unworthy action, detested a falsehood, uttered no expression offensive to the chastest ear, was grateful, feeling, and humane….”

Col. Beresford is called back to England, so the family packs up and takes passage for England. They survive a hurricane in the crossing to England and Yamboo acquits himself well in manning the pumps.

Col. Beresford is called back to England, so the family packs up and takes passage for England. They survive a hurricane in the crossing to England and Yamboo acquits himself well in manning the pumps.Upon returning to England, Yamboo almost drowns when he rushes into the ocean to save another servant who had gone sea-bathing. They are both rescued by the family’s Newfoundland dog. But Yamboo’s carelessness in changing out of his wet clothes leads to unfortunate consequences; he catches a fever (as one does) and nearly dies.

As he recovers, Mrs. Beresford tutors him in the doctrines of Christianity, “impressing upon his hitherto untaught mind the sacred truths which illumined her own.”

He “willingly received all that his limited capacity allowed him to comprehend; the veil of ignorance, which had hitherto obscured it, was cautiously withdrawn by his benevolent friend… she taught him also carefully to avoid those violent extremes, which too often, in illiterate minds, amount to absurdities, by the external professions they deem laudable convictions of their conversion to Christianity; hence Yamboo was the humble trusting believer, silently adoring the Power, whose gracious works he now delighted to trace in all around him…”

Colonel Beresford is sent to India and Yamboo insists on going along; As he explains, he is doing it for the colonel's wife and daughters. Mrs. Beresford "love nothing so well as him colonel, and now him going far off. Yamboo must go take care of him, bring him safe back.”

I believe the time period must be the Third Anglo-Mysore War, 1790-1792, because the author mentions Tippo [aka Tipu] Sultan, who was not killed by the British until the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War.

So, off they go to India to fight Tippoo [aka Tipu] Sultan... Let’s pause here and consider whether you could imagine Jane Austen, with her cool and ironic voice, writing about Sir Thomas returning from Antigua with a little slave boy with scars on his back, a slave boy who gives Fanny Price a run for her money in terms of faultless behaviour. And although there are military men and sailors in her novels, Austen never follows them to the cannon’s mouth as this author does. Austen just did not take on dramatic or melodramatic subjects. Her sense of humour always crept in--Austen knew her own voice. Could this not in itself explain why Austen doesn’t delve into slavery as a subject, regardless of her personal opinions?

Or, we could go on enthusing about how Jane Austen named her book after Lord Mansfield, even though this is nothing more than a supposition. If you want a book with a little more meat on the bones, try Yamboo...

Next post: the conclusion to the story of Yamboo, or, a whole lot of coincidences.

Soldier of the New Brunswick Fencibles (later the 104th) About the anonymous author

Soldier of the New Brunswick Fencibles (later the 104th) About the anonymous authorThe author of Yamboo was a wife and mother who lived in the province of New Brunswick from at least as early as 1810. It seems probable her husband was in the military, and that she was an Englishwoman.