Lona Manning's Blog, page 10

August 24, 2023

CMP#149 Modern Manners and Mansfield

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality.

Click here

for the first in the series. For more about other female writers of Austen's time, click the "Authoresses" tag in the Categories list to the right. CMP#149 Modern Manners, part two: of Meaning and Mansfields

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality.

Click here

for the first in the series. For more about other female writers of Austen's time, click the "Authoresses" tag in the Categories list to the right. CMP#149 Modern Manners, part two: of Meaning and Mansfields

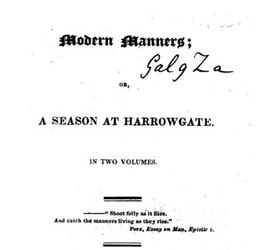

English nabob smoking a hookah In my last post, I gave a synopsis of an 1817 novel, Modern Manners, or a Season at Harrowgate, which featured a big cast of characters, two sets of romantic triangles, a comic subplot, misunderstanding, and moral lessons. Now I'd like to discuss some other features of interest.

English nabob smoking a hookah In my last post, I gave a synopsis of an 1817 novel, Modern Manners, or a Season at Harrowgate, which featured a big cast of characters, two sets of romantic triangles, a comic subplot, misunderstanding, and moral lessons. Now I'd like to discuss some other features of interest.Every time I read one of these forgotten novels of the long 18th century, I make note of any references to slavery and colonialism, women's rights, and other topics of current academic interest. For example, several characters in this book have colonial wealth; most notably, Lord Fitzgerald, who came back from India with a large fortune. He intends to marry his son to an heiress with an East Indian fortune. While Lord Fitzgerald has his faults as a parent, he is not critiqued in the novel for the source of his wealth, though of course it is inferior to inheriting your wealth but a class/rank standpoint. The heiress, Elvina Dorrington, is not faulted for her Indian riches, but for her lack of sound religious principle and her "languid" and sensual character.

Turkish princess masquerade costume Slavery and Colonialism

Turkish princess masquerade costume Slavery and ColonialismThere is no reference to slavery or plantations in Modern Manners even though the term "slave" is used a number of times. Lord Wimbledon can’t get to sleep because his friends are noisily drinking 'til the wee hours. One of them shouts, “time is made for slaves.” Wimbledon picks up a book the heroine had been reading—it’s Cowper’s poem “The Task,” in which the poet references slavery and Lord Mansfield's Somerset case ("We have no slaves at home --then why abroad?") although this is not mentioned. Cowper is referenced to show that the heroine Emma Osborne is no airhead, and therefore Wimbledon grows ashamed of his own pleasure-seeking, trivial life.

Arabian harems were a source of fascination for the Brits, and the wealthy Fitzgeralds dress up in exotic costumes for a masquerade ball. Lady Fitzgerald dresses as a “slave,” Lord Fitzgerald is a sultan, their daughter Julia is a veiled Arab princess. There are no reflections on the irony of dressing up as a slave when the source of your wealth is East Indian exploitation.

Julia Fitzgerald elopes from the ball with the flashy Captain Farquarson, but when she realizes he's an unprincipled fortune-hunter, she tells him ‘”I am no longer your slave.” Later, she sorrowfully tells Emma: “do not sink me into a mere child, the slave of passion… I have inflicted the wound myself.”

These examples show us how casually people used the term “slave” at this period to describe any kind of constraint. Slavery was a fact of life, but Arab slavery--that is, seraglios or harems--were sexually titillating and exotic.

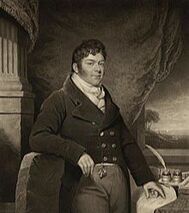

William Murray, Lord Mansfield (1705 - 1793) The Meaning of Mansfield

William Murray, Lord Mansfield (1705 - 1793) The Meaning of MansfieldNow I finally come to the reason why I lighted on Modern Manners in the first place: I have been seeking out novels of this era with characters named "Mansfield." "Lord Mansfield" is the secondary romantic hero in this book, who patiently woos and wins the lively Julia Fitzgerald. If we are to argue that the title "Mansfield Park" was recognized by Austen's readers as a reference to the real Lord Mansfield, what does it mean when an author names one of her characters "Lord Mansfield"? Did the name "Lord Mansfield" in a book published three years after Mansfield Park send a message about slavery? (If you don't know about the Lord Mansfield/slavery connection here is a backgrounder).

Personally, I don’t think the author of Modern Manners is trying to send an anti-slavery message with the name "Lord Mansfield." I think it’s just another solid English name. More broadly, I'm dubious about the idea that authors of this period introduced highly subtle allusions about social issues in the middle of their love stories. If they wanted to inveigh against slavery or masquerade balls or the depravity of London, they went ahead and inveighed, or had one of their characters do so. Nor, contrary to what you might have been told, was there any danger or difficulty around discussing slavery in a novel at this period.

There is no biographical similarity between this fictional Lord Mansfield and Lord Mansfield the Chief Justice, who died 24 years before this book was published. But I concede that others might think it is no coincidence that after Julia tells Captain Farquarson, “I am no longer your slave,” the character named Lord Mansfield springs into the garden, sword drawn, ready to rescue her.

As for contemporary critics, If the name "Lord Mansfield" raised associations in the readers' minds back in the day, the one reviewer who wrote a lengthy and favourable review of the novel in the Gentlemen's Magazine did not think it worth mentioning. He names and describes four other main characters, but he doesn't discuss Lord Mansfield. Mansfield is dismissed in one sentence with the “the rest of the gallants [who] are all very fine young men—very hopeful specimens indeed.”

The Dangers of Novel Reading

The Dangers of Novel ReadingIf novel-readers of the day were not as preoccupied with the horrors of slavery as we think they ought to have been, what were they preoccupied with? Well, female chastity, of course, female education, and whether novel-reading had a tendency to overheat female imaginations. As Jane Austen remarks in a famous passage in Northanger Abbey, novelists were guilty of “degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding.” There is a particularly extended example of this in Modern Manners, in which the secondary heroine Julia (representing "Modern Manners," jousts with some older minor characters who fear that "all fictions are immoral, their very source springing in falsehood, and supported by the extravagant vagaries of fancy." The character of Mr. Seymour is given several soliloquies in the book on various topics, and I think he is the author's alter ego: “And does Miss Fitzgerald ever read novels?” cried a maiden lady, looking very superciliously at Julia as she spoke.

[An old gentleman asks if “any lady could resist them?”]

“Resist them?” cried the lady, looking both angrily and haughtily, ‘you must have a very contemptible opinion of the female understanding but I, sir, never read them.”

“And I, madam,” said Julia, “pity you for a prejudice, which deprives you of a gratification, which works of imagination, when written with taste and feeling, must create.”

“As works of imagination merely, my dear young lady,’ returned the old gentleman, (whose name was Seymour), “I should not plead for them; no, not even if written with taste and feeling… we folks of the last century will have our opinions, and an obstinate one of mine is, that these weapons are often so bright and dazzling, that the sentiments and morals, are lost amidst their fascination and brilliancy…."

[He acknowledges there are some excellent authors who are exceptions to the rule. This conversation continues for several pages and then segues into a discussion of female education, which allows Julia to exclaim:] “Surely, Sir... you are not an advocate for intellectual blindness in the female sex? Are not our powers of mind equal to you lords of the creation? And have we not a right to exercise them? Would you confine us to the grim country mansions of our forefathers, to gain our only knowledge from the tapestry figures, and the housekeeper’s receipt book? Fie, my good Mr. Seymour, I thought you had been more liberal.”

[the conversation continues until it is interrupted by the sudden entrance of another character who announces that Lord Wimbledon is racing against a famous jockey.]

Published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, London, 1817 About the Author

Published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, London, 1817 About the AuthorThe lady who wrote Modern Manners probably had never met a Lord in her life or attended a masquerade ball. One critical reviewer pointed out how incorrect it was for "gentlemen to address ladies by their Christian names on the first day of their acquaintance" as Nevison does with Elvina. The author seems to have lived outside of London, because she apologizes for the number of typographical errors in the book because “the Business of the Press has been conducted at such a Distance as to preclude any Correction.” Perhaps she lived in or near Harrogate, which she spells "Harrowgate."

If you read my synopsis of this book, you might wonder if the anonymous author has borrowed some of her plot points from Austen, although that is by no means certain, since multi-generational stories, lively girls who fall for cads, or dislike of private theatricals, aren’t unique to Austen. The author appears to admire the writer Jane West, because she emulates her traits of explicit moralizing, winking at her readers about novelistic tropes, and referring to herself as a “spectacled old woman,” à la West’s alter ego of Prudentia Homespun. The character of Mr. Seymour includes “West” in his list of good authors who are worth reading despite being novelists: ‘while we have the works of an Edgeworth, an Hamilton, a West, and a Moore,* who, by lashing the follies of the times, and making (if I may be allowed the expression) fiction the vehicle of truth; yes, while their lessons exist, shall we quarrel with the mode in which they are conveyed?."

Alas, "Austen" does not make the list of Mr. Seymour's admirable authors. although by the time Modern Manners was published, four of Austen's novels had been published. Perhaps Austen didn't lash the follies of the times as severely as the anonymous author thought she should.

Modern Manners received two reviews. The Monthly Review found it "improbable without being fanciful, and in which the observations meant to be moral and religious are… trite and wearisome.”

The other review, in the Gentlemen's Magazine, was lengthy and favorable, and the reviewer even surmised about the identity of the writer: “Judging from the internal evidence we should pronounce this to be a juvenile performance, thought the fair author has chosen to represent herself as an elderly spinster. We would not be so impolite as to call a lady’s word in question; but there is a graceful and easy veracity in the narrative, and a spirited versatility in the delineation of the characters, which cannot well be reconciled with the idea of matronly sedateness… In this conclusion we are persuaded that every Reader will concur; it will be quite as natural to him as that which he would form in overhearing from the next apartment a fine song delightfully executed and accompanied; he would never, by any possible range of conjecture, imagine the unseen warbler to be an old lady in spectacles.”

Despite that one good review, Modern Manners was not picked up by many circulating libraries, only 3 out of 20, according to the invaluable British Fiction website. This is perhaps why we don’t see any further novels from “the author of ‘Modern Manners,’ etc.”

*The authors Mr. Seymour lists are Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849), Elizabeth Hamilton (1756-1816), Jane West (1758–1852), and John Moore (1729–1802), although possibly this is a reference to Hannah More (1745-1833). I reviewed John Moore's Edward: various Views of Human Nature, Taken from Life and Manners, Chiefly in England (1796), in an earlier post.

Previous post: Modern Manners synopsis

Published on August 24, 2023 00:00

August 17, 2023

CMP#148 Book Review: Modern Manners

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#148 Book Review: Modern Manners, or, a Season at Harrowgate (1817) Note: I've included details that resemble Austen, while leaving it to my clever readers to spot them.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#148 Book Review: Modern Manners, or, a Season at Harrowgate (1817) Note: I've included details that resemble Austen, while leaving it to my clever readers to spot them.

Harrogate spa well, Wikicommons, detail Synopsis

Harrogate spa well, Wikicommons, detail SynopsisModern Manners, an 1817 novel by an anonymous authoress, starts with the marriages of the parents of our main characters. Amelia has the good luck to captivate Henry Fitzgerald, a “gentleman from the Indies” (aka a man with a colonial fortune) who all the “Mamma’s” of the neighbourhood are angling after. Amelia’s match means she goes off to live in London and mingle with the ton. Her sister Matilda marries Mr. Oswald, a respectable vicar with a small independent fortune. Matilda “sighed at the idea of… her sister [Amelia] being lost in the fashionable vortex of dissipation and vanity."

The years pass, the countrified Oswalds have a daughter and the city-dwelling Fitzgeralds have two sons and a daughter. Mr. Fitzgerald becomes an MP and then is elevated to the peerage; now, instead of being the wife of a nouveaux riche Indian nabob, Amelia is Lady Fitzgerald. An easy-going woman of no strong opinions, Amelia is more engaged with her morning visits and playing cards than paying attention to the education and moral upbringing of her daughter Julia.

The Fitzgeralds come to visit the Oswalds and their lovely, sensible, daughter Emma. Julia Fitzgerald is a social butterfly and an enthusiast for Rousseau, rugged scenery, and defying whatever it is her parents want her to do. We learn that the oldest son, Frederic, is not very attentive to his fiancée. She is Elvina Dorrington, an Indian heiress. Emma Oswald, our main heroine, is intelligent, virtuous, principled and sincerely devout, and the author struggles to make her as interesting as Elvina and Julia. But Emma is firm as a rock in her principles, while Elvina and Julia don't really have principles... Romantic triangles

When the Fitzgeralds move on from the Oswald’s quiet parsonage for a visit to Harrowgate (a spa town in North Yorkshire), they take Emma with them to give her a taste of high society and a chance to meet some eligible men. Many more characters join the tale. This novel is set amongst the privileged and titled, although it’s quite likely the anonymous author never met a lord in her life. Other surnames in the novel include: Montreville, Wimbledon, Seymour, Nevison, Beaumont, Percival, Farquarson, and Mansfield.

Elvina the heiress is frequently described as “indolent,” and “languid,” which was typical for descriptions of people from the East or West Indies. If we had actually met Miss Lambe, “chilly and tender” in Jane Austen’s unfinished Sanditon, she might have been indolent and languid, too. Elvina's languid beauty temporarily attracts the intelligent and gallant Captain Nevison, until he realizes she’s engaged to Frederic Fitzgerald, then he hastily backs off.

Meanwhile, Julia has fun flirting with the outgoing Captain Farquarson and she ignores another suitor, Lord Mansfield. By the way, this is not THE Lord Mansfield, if you know who Lord Mansfield is. This Lord Mansfield is just an eligible but rather quiet and strait-laced young lord in want of a wife. Mansfield is dazzled by Julia's “beauty and commanding powers.” Yet, some of her beliefs and actions distress him. "Lord Mansfield had a dislike to any thing like private theatricals,” so he is more than merely jealous when Julia acts in dialogues with the flashy Farquarson as part of an evening’s entertainment. Farquarson moves in hard on Julia: he “was almost a constant inmate of the house, and if he sometimes took an opposite view of the subject to Julia, in the end, he always professed himself convinced by her arguments… the more delicate admiration of Lord Mansfield, compared with his, was insipid.”

When the young people make an evening tour of the ruins of the nearby Cistercian Abbey, Emma Oswald and Captain Nevison have a grand old time pondering the mutability of life together.

When the young people make an evening tour of the ruins of the nearby Cistercian Abbey, Emma Oswald and Captain Nevison have a grand old time pondering the mutability of life together.Then the young people all go boating on the lake, and Elvina accidentally falls in. Her fiancé can’t be bothered to rescue her, but Captain Nevison promptly dives in and fishes her out, so of course she falls madly in love with him, just as he is realizing he is in love with Emma.

More complications: Emma has another suitor, a titled Lord no less, Lord Wimbledon. His fashionable friends laugh at him for mooning over a “country parson’s daughter,” but he realizes that she is a superior young woman and the way she conducts her life makes him feel ashamed of how he has trifled away his.

He proposes, Emma politely turns him down, a refusal which causes consternation and surprise with her fashionable Fitzgerald cousins. Turn down a Lord? She can’t help it, she loves the intelligent and principled Captain Nevison, and although he’s got to go join Wellington in the Peninsula to fight Napoleon, she agrees to an engagement.

The same plot point occurs in Jane Porter's Thaddeus of Warsaw Impediments and Spoilers

The same plot point occurs in Jane Porter's Thaddeus of Warsaw Impediments and SpoilersSince there are no impediments of class or wealth to create difficulties for our hero and heroine, we must turn to misunderstanding to keep them apart: Elvina Dorrington can’t keep her lust for Nevison under control. She goes to the inn where he’s staying and literally throws herself at him: “'Tis you have made me abhor the rest of mankind, and I loathe their very sight; and yet—and yet—you can seek another!'… she threw herself before him, and embracing his knees, exclaimed, ‘Oh, save me! Save me!' Her bonnet fell, her beautiful hair with the motion escaped, and her tresses floated in wild disorder. ‘Would,’ cried he, with a look of agony, ‘that I could save you from yourself—from the torment of your own reproaches!’"

(This is similar to a scene in Jane Porter’s wildly popular novel, Thaddeus of Warsaw, down to the discarded bonnet, the loosened hair and hero's reference to the fates of fallen woman to make the girl come to her senses.)

Unfortunately, the false rumor comes back to the Oswalds that Nevison and Elvina have eloped together, and Emma sorrowfully renounces him:

“I still love….[but] never will I unite my fate with a libertine, a destroyer of the honour and peace of one of my own sex. It is true I feel, tenderly feel; for had I not reposed my trust, and placed my confidence in his virtue and truth?”

Nevison, in far-off Portugal, is unable to clear up the mystery for the time being, and the Emma/Nevison plot recedes to the background.

Turkish delights at the Masquerade Fortune-hunting Farquarson

Turkish delights at the Masquerade Fortune-hunting FarquarsonThe Julia/Farquarson/Mansfield love triangle takes center stage. As you'll recall, Lord Mansfield loves the imprudent Julia, “even against his better reason” while Julia is infatuated with Captain Farquarson, unaware that he’s a slimy fortune hunter. (He’s Irish, so what can you expect).

Madcap Julia elopes with Captain Farquarson from a masquerade ball (never go to a masquerade ball, girls, you are just asking for trouble). Retrieved in the nick of time by her father, the family tries to hush the whole thing up, but Farquarson blackmails Julia for breach of promise money. By an amazing coincidence, Julia meets his impoverished sister, who tells her that she has to find a job because her brother does nothing to help her, or their widowed mother. Julia also learns that he already has a wife!

And I’m going to mention another subplot which gives the main heroine something to do while she’s nursing her broken heart back at the parsonage. Emma’s friend Harriet Merton comes to visit and meets Mr. Oswald’s new curate, fresh out of university. Mr. Roberts doesn’t know much about women and he ignores Emma while he sits and discusses Greek and the classics with Mr. Oswald. But when he hears Emma discourse on appropriate topics such as moral philosophy, his "curiosity was awakened. He had a vague notion, that the knowledge of women was very circumscribed, that their conversation must be on the topics of the day, dress, or at best on the occupations of domestic life. It is true, his information was merely derived from periodical papers, which lashed the follies of the times, represented the beautiful simpletons, or a disgusting picture of pedantry and affected learning. A new class of beings seemed to rise before him as he beheld Emma Oswald and her friends.”

Harriet figures that the curate is falling for Emma, but “Emma drew more just conclusions. She saw him surprised and amused with the power of Harriet, and she saw likewise that he was gratified by her never-failing appeal to him on any subject on which she was uninformed.” Yes, Emma is right—the young minister is falling for Harriet.

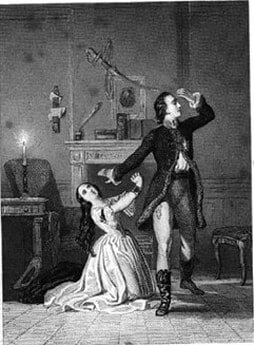

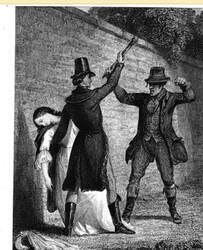

Actually, that's Thaddeus of Warsaw again, but you get the idea Nice guys finish last

Actually, that's Thaddeus of Warsaw again, but you get the idea Nice guys finish lastBack in London, Julia agrees to meet the blackmailing Farquarson secretly in her back garden at night. (Again, ladies, just—don’t do this). She intends to confront him with the fact that he’s already married, so he can stop badgering her for money. Like a proper villain, Farquarson announces he plans to abduct her and compromise her. He sneers, “are you not completely in my power?” Luckily, Lord Mansfield, knowing that Farquarson has been hanging around, has also been watching Julia’s house. He springs in to rescue her.

Julia is safe, but the shock of the confrontation makes her fall ill with a severe fever, as one does, or at least as one does in novels of the long 18th century. Her illness is serious and prolonged and Emma comes to nurse her because Lady Fitzgerald just isn’t up to it.

Julia sinks into depression as she reflects with great remorse on her past conduct. She concludes that a good and principled man like Lord Mansfield shouldn't want to have anything to do with her. She sends him away: “'It is all futile.—Shall I be so base as to take advantage of a passion which, when its brilliancy passes off, will see me in a different light, because possessed of opposite opinions to yourself?—No, it can never be.'

“In vain Lord Mansfield pleaded his devotion, his affection; in vain he declared them unalterable…”

Meanwhile, over in Portugal, Julia’s brother Edward runs into Captain Nevison, and also into his brother's ex-fiancée Elvina, who has disguised herself as a young cadet in order to get close to Nevison. The misunderstanding is sorted out. Elvina repents her wild conduct and takes ship for England. Coincidentally, Emma and her father witness the shipwreck which brings Elvina, half-dead, to the shores of England and Emma nurses her. Mr. Oswald helps her prepare to meet her maker before she dies.

Continued in the next post.... Previous post: A copy/paste children's book Next post: What do you mean by "Mansfield"?

Published on August 17, 2023 00:00

August 10, 2023

CMP#147 An Excursion from London to Dover

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#147 Book Review: An Excursion from London to Dover

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#147 Book Review: An Excursion from London to Dover

By her own account, Jane Gardiner (1758–1840) was fortunate in her employers when she went to work in her mid-teens as governess for a genteel family with six daughters. Ten years later, she started her own school so she could offer a home to her parents and her invalid sister. By the time she retired at age 78, she had taught over 600 girls and worked for more than sixty years.

By her own account, Jane Gardiner (1758–1840) was fortunate in her employers when she went to work in her mid-teens as governess for a genteel family with six daughters. Ten years later, she started her own school so she could offer a home to her parents and her invalid sister. By the time she retired at age 78, she had taught over 600 girls and worked for more than sixty years.Gardiner also published some children’s books. Her 1806 book, An Excursion from London to Dover, is explained by its subtitle: “Containing some account of the Manufactures, Natural and Artificial Curiosities, History and Antiquities of the Towns and Villages. Interspersed with Historical and Biographical Anecdotes, Natural History, Poetical Extracts, and Tales. Particularly Intended for the Amusement and Instruction of Youth.”

The book is narrated by Jeanette, who is travelling with her friend Adelina and Adelina's father Mr. A____. It’s like an 1806 version of The Magic Schoolbus but without the magic.

All of this improving information is roughly tied to something approaching a plot, in which Mr. A_____ encounters several old school-mates or acquaintances on the journey. These additional adults give impromptu lectures to the children, speaking off-the-cuff about everything from the development of paper to to the anatomy of the snail. Adelina and Jeanette also recite poems from memory, whether the topic under discussion is the ocean, hedgehogs, spiders, war, clouds, cuckoos, etc, and Jeanette has perfect recall of the biographies of eminent rulers, scientists, and statesmen. Gardiner also works in some short moral tales and a backstory or two.

Writing after her mother’s death, Jane Gardiner’s daughter said of An Excursion: “Though this work does not possess much originality of thought, the reviewers allowed it to evince sound judgment, great taste, and an earnest desire to promote the improvement of the rising generation.”

“Originality of thought,” is a euphemism for the fact that most of the book was what we today would call plagiarized.

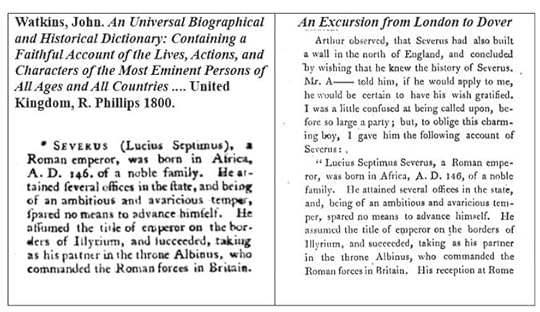

Madame Jerome Bonaparte by Gilbert Stuart "Pray, explain metals and semi-metals."

Madame Jerome Bonaparte by Gilbert Stuart "Pray, explain metals and semi-metals."It turns out Gardiner copied her useful information directly from other people’s travel guides and children’s books, re-phrasing and adapting as necessary for her plot. I’ll come back to that. But first, some observations:Anyone who thinks genteel girls in Jane Austen’s time were not expected to have a good education should crack open some of their school books. The curriculum was broad and extensive, covering history, geography, botany, what we would call today social studies, and children were expected to memorize reams of poetry. How many girls today can “tell the principal rivers in Russia” as young Julia and Maria Bertram can? Their governess Miss Lee could very well have used An Excursion to cover most of the curriculum mentioned in Mansfield Park. It even includes a biography of the Emperor Severus.I like coming across references to, or predictions about, the future in these old books. Mr. A____ and the children are strolling along the beach at Margate while he descants on the metals and semi-metals, but the sighting of a fish “turned the discourse” and he exclaims: “Should man ever be enabled, by any future discovery, to traverse the bottom of the sea, what wonders would be opened to his view! What numberless examples would appear of contrivance and sagacity, directed by the same wisdom that has instructed the bees to gather honey, and the beaver to construct his habitation!”It appears that Jane Gardiner also designed a Trivial Pursuit-type of board game for children, because she plugs it in the book: Jeanette reports that the travelers and their friends relaxed with “Gardiner’s Evening Amusements, a game which I intend to purchase; it is a large flat box, divided into thirteen partitions, containing thirteen packs of cards, with questions on as many different subjects.” “[A] great deal of instruction is to be acquired from this game. Mr. A_____ was much pleased with it.” I haven’t been able to find any other reference to this game.In Volume 2, we encounter a real-life celebrity, Madame Jerome Bonaparte, formerly Betsy Patterson of Baltimore, who must have created a sensation when she arrived in England after being turned away from the continent by Napoleon. “She was dressed with great simplicity and modesty; on her head she wore no ornament but her hair, seeming to trust entirely to that Nature, which had been so bountiful to her.” Napoleon’s younger brother Jerome had married the Baltimore beauty impulsively and incurred the anger of his brother, who refused to recognize the marriage.

Grandma's sight restored by Mr. Bennett, HEA for Simon and Anna Improving stories

Grandma's sight restored by Mr. Bennett, HEA for Simon and Anna Improving storiesAs befits a children’s book from this period, the inset backstories and tales all serve to teach some moral lesson, such as the importance of being charitable. In one of these tales, the “poor but virtuous” Anna refuses to marry Simon, the town’s most eligible working-class bachelor, who has a “very neat cottage on the skirts of the town, a cow, three pigs, etc.” Like Austen’s Emma, Anna “resisted [Simon’s] solicitations to become his wife; and though she acknowledged his merit, and that she esteemed him very much, she would not consent to marry him, because, she said, she should then have household affairs to attend to, and could not take proper care of her grandmother.” (Gardiner herself may have lived by this precept, because she did not marry until after her parents died.) Luckily, Ann's blind grandmother receives a cataract operation from the local surgeon, Mr. Bennett (who happens to be an old acquaintance of Mr. A____), which means she can help look after herself.

The most dramatic incident in the book is a shipwreck on the coast of Margate, which throws several bodies on the shore, including a “rich planter from Jamaica” and his slave. Another one of Mr. A____’s long lost friends knew the planter and also knew the enslaved man’s backstory: “‘This negro,” said he, ‘was a powerful prince of Congo; and, being at war with the King of Loango, was taken prisoner, and sold by him to Ganna, of Dacard, a noted manstealer, employed as such by the slave-merchants there. Being thus taken, he was brought to Goree, where he was sold to a planter, one of the greatest of tyrants. This poor prince, after suffering unheard-of cruelties inflicted on him by this wretch, in a fit of despair stabbed himself; but the wound not proving mortal, he was again sold to this [new] planter, and now met his death in a watery grave.’

Adelina is inspired to write a poem commemorating Yanko’s sad life, which in fact is an abridged version of the then-famous poem, The Dying Negro. Interesting that a school teacher has a child plagiarizing a poem, although it’s not presented as plagiarism.

Yanko is portrayed as a prince, which is typical for narratives of this era, as though a African who wasn't blue-blooded would not merit as much sympathy. We also see the distinction made at this time between the slave-trade and slave-owners. Slave-traders were unequivocally condemned but slave-owners were not. The owner who drowned with Yanko, according to Mr. Mansfield, “was a worthy, humane, man, and, he had no doubt, had ever treated him with lenity.”

But hold! Stop! Mr. Mansfield, did you say? Mr. A____’s old friend is named Mansfield? A subtle allusion?

Is this juxtaposition of the name Mansfield with the story of an enslaved man a subtle reference to Lord Mansfield? (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, click here for a backgrounder, and if you don't care, you can skip this section).

Well actually, no, there is no connection intended. For one thing, "subtle" and "early English children's literature" have nothing to do with each other. Yes, many scholars believe, but no-one can prove, that Austen named her novel Mansfield Park after Lord Mansfield. But I can explain why Jane Gardiner chose the name Mr. Mansfield, and it wasn’t in homage to the eminent jurist. She named her character Mr. Mansfield because she copied the character and much of his dialogue from another children’s book, A Visit to a Farm House. (1804).

In "A Visit to a Farmhouse," grandfather Mansfield teaches Charles and Arthur about wheat and how to mill it, while Uncle Mansfield teaches his nephews Charles and Arthur about wheat and how to mill it in "An Excursion."

In "A Visit to a Farmhouse," grandfather Mansfield teaches Charles and Arthur about wheat and how to mill it, while Uncle Mansfield teaches his nephews Charles and Arthur about wheat and how to mill it in "An Excursion."

Grandfather Mansfield in "A Visit to a Farmhouse" Excursion covers a much broader range of subjects than Farmhouse, and the shipwreck episode about Yanko does not appear in the source material. Jane Gardiner extended Mr. Mansfield’s role and gave him a backstory (he’s a rich uncle who made a huge fortune in India. He gives his money to his virtuous niece). So Uncle Mansfield is also a colonizer, but Gardiner uses him, and yet another rich uncle later in the narrative, to bestow handy fortunes on the deserving. This is a

very common plot device

of the era and demonstrates that broadly speaking, people were not inclined to condemn colonial fortunes out of hand.

Grandfather Mansfield in "A Visit to a Farmhouse" Excursion covers a much broader range of subjects than Farmhouse, and the shipwreck episode about Yanko does not appear in the source material. Jane Gardiner extended Mr. Mansfield’s role and gave him a backstory (he’s a rich uncle who made a huge fortune in India. He gives his money to his virtuous niece). So Uncle Mansfield is also a colonizer, but Gardiner uses him, and yet another rich uncle later in the narrative, to bestow handy fortunes on the deserving. This is a

very common plot device

of the era and demonstrates that broadly speaking, people were not inclined to condemn colonial fortunes out of hand.The original Farmhouse Mr. Mansfield is a gentleman farmer, not an abolitionist. And I doubt either book had any influence on Austen, even though Gardiner’s version of Mr. Mansfield helps an old family servant named Bertram. Small world, isn’t it? No wonder Mr. A____ keeps running into people he knows as he travels from London to Dover.

So here we have two books for children, one of which includes an anti-slavery message, both published less than ten years before Mansfield Park, where the name “Mansfield” is just a sturdy old English name. I'll resume my explorations about Lord Mansfield and whether invoking the name "Mansfield" had a particular meaning for Regency readers at a future date.

Gardiner acknowledged only some of her sources in her Table of Contents Intellectual Theft

Gardiner acknowledged only some of her sources in her Table of Contents Intellectual TheftI think An Excursion From London to Dover would be interesting for any historians of the evolution of intellectual property laws. It’s clear that Gardiner did not regard her literary borrowings in the same light as we do today. At least one of the authors she cribbed from, John Evans, called her out: “The Proprietor of the Juvenile Tourist has been advised to prosecute, and no doubt can be entertained of damages being awarded to him. The Author, however, has in the mean time thought proper thus to lay this plain statement before the public—leaving Mrs. Jane Gardiner, of Elsham Hall, to the consideration of the eighth commandment, and to her own reflections."

Gardiner acknowledged some, but not all, of her sources in her table of contents, (which, of course, is not the same as obtaining permission or compensating those writers whose work she used.) For example, she shows where she cribbed her biographies and poems from, but she does not acknowledge her debt to “S.W.,” the author of A Visit to a Farmhouse.

I wouldn't be surprised if Gardiner's inset stories (and I didn't even get to the story about the foundling who survived the shipwreck) are also borrowed from other writers.

Gardiner and her publisher might have been egregious about their copying, but she obviously didn't view it as being wrong, much less sinful. However, as scholar Benjamin Colbert notes: "Whether coincidentally or otherwise, Gardiner published no more after" Evans complained of her "plagiarisms" in the 1809 edition of his book.

In a final ironic twist around intellectual property, the author of A Visit to a Farmhouse, Sarah Scudgell Wilkinson, made a living by condensing and abridging dozens of successful novels and selling them as small chapbooks, a sort of early Readers’ Digest Condensed Books.

Hadrian's Wall was once called Severus's Wall. Jeanette's "confused" is more like our "embarrassed." Maria and Julia Bertram studied the Roman Emperors "as low as Severus" in Mansfield Park. Severus was the only Roman Emperor to have died in England.

Hadrian's Wall was once called Severus's Wall. Jeanette's "confused" is more like our "embarrassed." Maria and Julia Bertram studied the Roman Emperors "as low as Severus" in Mansfield Park. Severus was the only Roman Emperor to have died in England.

Wilkinson also wrote many gothic novels About Jane Arden Gardiner

Wilkinson also wrote many gothic novels About Jane Arden GardinerJane Gardiner (1758–1840) published several grammar books, although I couldn't say if they were all her own original work. She was a youthful friend of Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft also worked as a governess (but was fired) and started a girls’ school (which failed). Wollstonecraft's personal life (i.e. becoming an unwed mother) led to widespread condemnation of her ideas after her death. Gardiner preserved some of Wollstonecraft's early letters and later recalled: “She was a very amiable young woman… I must greatly lament, as her friend, that her great talents were misapplied, and that she so grossly degraded herself."

Gardiner's students and their parents thought well of her. Her daughter published an affectionate brief biography but it has the barest biographical details and page after page of attestations to her piety, and her emphasis on faith before works as the key to salvation. The book includes an extended description of her final illness: “All the support she could occasionally take, was the smallest portion of arrow-root.” Here again her fate differs from Emma's Jane Fairfax's. Gardiner had no Frank Churchill to rescue her.

Sarah Scudgell Wilkinson, (1779–1831) Gardiner’s unacknowledged co-author, was culturally of the middle class but poor all her life. She wrote prolifically, worked as a teacher and as a small shop-owner, but ended up dying in a workhouse. Like many other authors, she applied for and received monies from the Royal Literary Fund. So far as we know, Jane Austen never considered working as a governess or teacher. After her father's death, she, her sister and mother were dependent on her brothers for an income. Her creation Jane Fairfax gets a fairy-tale ending, but that doesn't mean Austen was insensitive about the problems faced by her countrywomen. In adulthood, she became firm friends with the governess who worked for her brother Edward.

Gardiner's thoughts on Wollstonecraft are quoted in Percy, Carol. "Paradigms for their sex? Women's grammars in late eighteenth-century England." Histoire épistémologie langage 16.2 (1994): 121-141.

John Wiltshire debunks the search for hidden meanings in Austen's choices of names in "Some Names in Mansfield Park: A Critique of Margaret Anne Doody's Jane Austen's Names: Riddles, Persons, Places," in Persuasions, the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America, No. 42, 2020.

When Jerome Bonaparte abandoned his wife in compliance with Napoleon's wishes, she found it very difficult to go back to being just Betsy Paterson of Baltimore. Her brief taste of fame and moving in the highest circles eventually lured her back to Europe and an independent life which shocked her father. Geri Walton tells her story here.

Thanks to A Visit to a Farmhouse, I learned what Mrs. Norris was talking about in Mansfield Park when she described Dick Jackson “making up to the servants’ hall-door with two bits of deal board in his hand.” Grandfather Mansfield explains that “the wood of the fir, when cut up into timber, is called deal.”

Previous post:

Some lovers of Jane Austen think that borrowing her characters is also a form of intellectual theft, though at least no copyright laws are being violated.

Some lovers of Jane Austen think that borrowing her characters is also a form of intellectual theft, though at least no copyright laws are being violated.In my novel A Contrary Wind, Fanny Price runs away from Mansfield Park and takes a job as a governess. The proper education of children was a common theme and topic of discussion in literature of the long 18th century. Considering that girls were largely homeschooled, no wonder this was a preoccupation of the time. Publishers like Tabart specialized in books to help parents teach their children at home. Click here for my series on female education in Regency times. Click here to read more about my novels.

Published on August 10, 2023 00:00

August 3, 2023

CMP#146 More Chimney-sweeps

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#146 Chimneysweeps and Cupids, again Last December, my research into Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid (the riddle which Mr. Woodhouse tries to recall in Emma)

was published in

Persuasions

online, the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America. I also published some pages and blog posts with more background information about Georgian love poetry and riddles.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#146 Chimneysweeps and Cupids, again Last December, my research into Kitty, a Fair but Frozen Maid (the riddle which Mr. Woodhouse tries to recall in Emma)

was published in

Persuasions

online, the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America. I also published some pages and blog posts with more background information about Georgian love poetry and riddles.My research is intended to refute the theory that the Kitty riddle about a chimney-sweep is actually a very dark and scurrilous poem about venereal disease and deflowering young virgins. So I won't recap all of that here, but I have come across some more riddles about chimney-sweeps, which I want to share because it gives us more context into what people of the long 18th century said about chimney sweeps.

As we know, the job of sweeping chimneys was miserable and sometimes fatal. Poorly fed, unwashed, overworked, dressed in rags, they were a daily sight on city streets. Many sympathetic poems and ballads were written about them.

But Georgians, being Georgians, could joke about anything. The blackness of chimney-sweeps was a frequent topic for humor, of course, and the same terms--"sooty," "dusky,"--were used interchangeably for them.

Jolly, light-hearted Christmas card

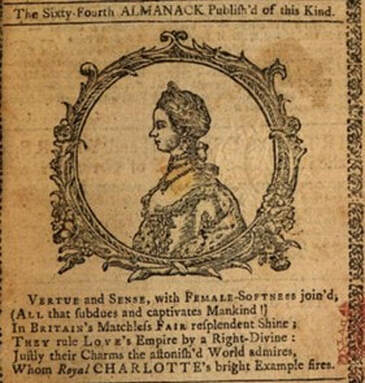

Jolly, light-hearted Christmas card  Okay, on to the chimney-sweep riddles. These two riddle-poems appeared in The Ladies' Diary: Or, The Women's Almanack, a long-running magazine for women. The readers affectionately referred to the Ladies' Diary as "Lady Di," and "Lady Dia." The title page shows Queen Charlotte and praises the "virtue and sense" of "Britain's matchless fair," a reminder that English women considered

themselves fortunate

compared to women in other countries. "Justly their charms the astonish'd world admires."

Okay, on to the chimney-sweep riddles. These two riddle-poems appeared in The Ladies' Diary: Or, The Women's Almanack, a long-running magazine for women. The readers affectionately referred to the Ladies' Diary as "Lady Di," and "Lady Dia." The title page shows Queen Charlotte and praises the "virtue and sense" of "Britain's matchless fair," a reminder that English women considered

themselves fortunate

compared to women in other countries. "Justly their charms the astonish'd world admires." The Diary was a collective effort; readers sent in their own poems, enigmas (aka riddles), charades, general queries, and even algebra problems. Then readers would mail in their answers which the editors would publish in the following issue. Readers sometimes even composed their answers to the riddle-poems in the form of a poem, as we will see.

It's interesting to see that the hive-mind was not an invention of the internet age. The following lengthy riddle-poem about a chimney-sweep was first published in 1767 and it gives various hints as to the identity of the speaker which all play on common tropes about sweeps. It starts with a masquerade at the Pantheon--you can learn more about the Pantheon at Regency History. The poet points out that all ranks and characters of people ("all conditions"), including pensioners (old people living on charity), can mingle in their masquerade disguises. We also have a reference to cross-dressing, for all you historical gender-bending cross-dressing aficionados. When the Pantheon rises now complete,

Delighting all the fashionable great;

Where, in fantastic, motley, masquerade,

To Folly’s shrine, devotion’s duly paid;

Where all conditions each disguise admit,

And ignorance assumes the mask of wit;

Where pensioners in masks with peers may vie,

And law puts on the mask of honesty;

Where sex itself is lost in garbs uncouth;

And falsehood wears the sacred form of truth;

Undaunted I appear the group to grace,

All dark disguis’d my person and my face

Interior of the Pantheon, Oxford Road, London, Hodges and Pars Leeds Museums & Galleries

Interior of the Pantheon, Oxford Road, London, Hodges and Pars Leeds Museums & Galleries

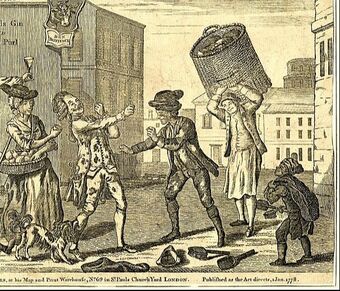

By the way, this satirical print "The Return from the Masquerade: a Morning Scene" from 1784 (British Museum) suggests that a chimney-sweep has attended a masquerade dressed as a Turk with a turban and mask. We know he's a chimney-sweep because he's carrying a brush and a bag of soot. Sweeps sold the soot they collected. The lady, who is drunk or asleep, is dressed as a shepherdess with her shepherd's crook.

By the way, this satirical print "The Return from the Masquerade: a Morning Scene" from 1784 (British Museum) suggests that a chimney-sweep has attended a masquerade dressed as a Turk with a turban and mask. We know he's a chimney-sweep because he's carrying a brush and a bag of soot. Sweeps sold the soot they collected. The lady, who is drunk or asleep, is dressed as a shepherdess with her shepherd's crook. Genteel men might also dress up as chimney-sweeps for masquerades and there is a record of a man going as "half miller, half sweep," a black and white costume of a miller of flour and a chimney sweep, as the contrast of black and white was endlessly amusing. There's also references to real sweeps going to masquerade balls pretending to be genteel people disguised as sweeps. So going in "blackface" had a different meaning.

But, let's get back to our riddle. Next, the riddler goes on to drop hints about rising, as though speaking of rising in a profession: By early education taught to please, (a reference to the fact that sweeps started young at 5 or 6 years old)

I rose by slow and regular degrees;

And by much study, and by cunning slight,

Reach’d an exalted, elevated height…. Then the riddler compares clearing the chimneys to a doctor applying a cure. The chimney is compared to intestines and to veins. Still I’ve perfections—be they now proclaim’d;

I’m a physician eminently fam’d;

No common quack, whose med’cines only tease,

Giving, at best, but temporary ease;

Nor one of those whose patent-royal pill,

Or noted nostrum, cannot cure, but kill;

For all my patients, whether rich or poor,

I soon relieve, and never kill, but cure;

And, in the compass of a single hour,

I prove my matchless medicating pow’r:

Like the magicians of remotest days,

With dark, disguis’d, insinuating ways,

Myself into th’infected parts instil,

Then on my patients exercise my skill

Their bowels penetrate, and inmost veins,

Where foul disorder and obstruction reigns,

At once cathartic and emetic prove,

Risking my life, tho; every part I move,

Till all is well, pursue the ailment close,

Myself the doctor and myself the dose.

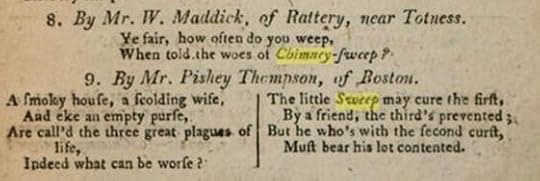

Black and white humor:. A barber covered with white hair powder fights with a chimney-sweep. 1778 Finally, the riddler references the fact that since sweeps were covered in soot, people obviously avoided brushing against them when they walked down the street. Avoiding chimney-sweeps is compared to the respect and reverence given to exalted persons. Similarly, the 1740 essay below right, jokes that chimney-sweeps should become government ministers because everyone "gives way" to them. He returns to the idea of disease, and the last reference in the riddle is to the repeated cry of the chimney-sweep ("sweep, soot, sweep") as he walks down the street. He compares it to an august churchman chanting the church service. The word "suite" in the final line is a play on "soot." When condescending to parade the street,

Black and white humor:. A barber covered with white hair powder fights with a chimney-sweep. 1778 Finally, the riddler references the fact that since sweeps were covered in soot, people obviously avoided brushing against them when they walked down the street. Avoiding chimney-sweeps is compared to the respect and reverence given to exalted persons. Similarly, the 1740 essay below right, jokes that chimney-sweeps should become government ministers because everyone "gives way" to them. He returns to the idea of disease, and the last reference in the riddle is to the repeated cry of the chimney-sweep ("sweep, soot, sweep") as he walks down the street. He compares it to an august churchman chanting the church service. The word "suite" in the final line is a play on "soot." When condescending to parade the street,Respect is paid me from all ranks I meet;

And, whether it proceeds from love or fear,

All clear the way whenever I draw near.

Perhaps from those I cure contagion flows,

Infects my breath, and hangs about my clothes.

Grave and collecting, still I move along,

Bidding defiance to the common throng,

While the attendants of my solemn pace,

All I proclaim, with repetitions, grace;

Monntomy from each salutes the ears,

And thro’ my suite one uniform appears.

The editors of the Ladies' Diary praised the riddle: "This last enigma, and that immediately preceding it, by Tasso [no doubt a pseudonym, and not the Italian poet], appeared both so well deserving to be the prize one, that we fairly determined the chance for that honour between them by lots." "Tasso" apparently sent in a third riddle which the editors didn't use because it was too risqué for a ladies' magazine: "The enigma on a Candlestick is too indelicate for insertion." [Insertion into the magazine, that is, but that sure looks like a pun].

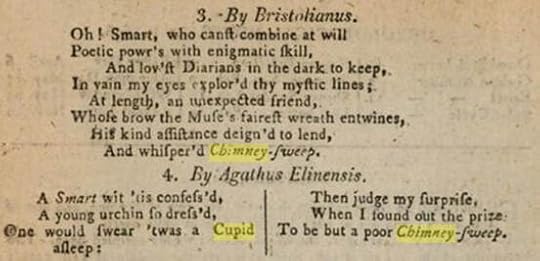

The editors of the Ladies' Diary praised the riddle: "This last enigma, and that immediately preceding it, by Tasso [no doubt a pseudonym, and not the Italian poet], appeared both so well deserving to be the prize one, that we fairly determined the chance for that honour between them by lots." "Tasso" apparently sent in a third riddle which the editors didn't use because it was too risqué for a ladies' magazine: "The enigma on a Candlestick is too indelicate for insertion." [Insertion into the magazine, that is, but that sure looks like a pun].Of course you can buy scurrilous material in all ages, but this publication is for ladies and there were some lines the editors would not cross. Therefore, the reference to disease and contagion in the chimney-sweep riddle is not necessarily a reference to sexually transmitted diseases; after all, contagious diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis were a daily fact of life. Many readers figured out the answer to the riddle and sent in their responses, often using pseudonyms. Here are a few of the answers, one of which references Cupid and uses the word "urchin," just like the Kitty riddle, but I am not sure why since the riddle does not play with the theme of love as the Kitty riddle does. Mr. W. Maddick reminds us that the life of a chimney-sweep is actually quite miserable. Mr. Pishey Thompson references the popular ballad, also a proverbial saying, "A smoky house and a scolding wife are two of the greatest evils in life."

Intermission: here is an example of a crude cartoon involving a chimney-sweep: "The Black Joke." The caption reads:

Intermission: here is an example of a crude cartoon involving a chimney-sweep: "The Black Joke." The caption reads:

Sweep-Sweep-soot hoa! Young Sooty cries

And shakes his Bag in Masters eyes,

But when by choleric Tom knock’d down

His head gets under Mamma’s gown,

Sweep saw the Joke with half a peep,

And archly cry’d, Sweep soot hoa! Sweep!

Courtesy British Museum and WikiCommons. "His bag" refers to the bag of soot. "Master" is the term of address for a genteel male youth. We recall that in those days, women did not routinely wear underwear. Petticoats yes, underwear no. Subtle, the Georgians were not.

The Ladies' Diary published another riddle about chimney-sweeps in 1794, by Mr. T.R. Smart, excerpted below. This one more closely resembles the Kitty riddle in its imagery and phrasing. However, in this riddle, the person who summons, but is afraid of the sweep, is a girl. Although afraid, she begs a "cure." "Fair" is basically the word used to refer to females at this time and is used as a noun. This riddle emphasizes the theme of disease and curing illness and also uses the trope of being afraid of being near the sweep, and perhaps also being afraid that he'll make a big mess with a cloud of soot in the house. Nor rest, nor ease, the weeping fair can know;

The Ladies' Diary published another riddle about chimney-sweeps in 1794, by Mr. T.R. Smart, excerpted below. This one more closely resembles the Kitty riddle in its imagery and phrasing. However, in this riddle, the person who summons, but is afraid of the sweep, is a girl. Although afraid, she begs a "cure." "Fair" is basically the word used to refer to females at this time and is used as a noun. This riddle emphasizes the theme of disease and curing illness and also uses the trope of being afraid of being near the sweep, and perhaps also being afraid that he'll make a big mess with a cloud of soot in the house. Nor rest, nor ease, the weeping fair can know;The nymph no longer able to endure,

On me she calls, from me she begs a cure,

Yet wond’rous strange! Tho’ I’m the only friend,

On whose kind aid she can for health depend

Her inconsistency of temper’s such,

Dreads my approach, and trembles at my touch!

When I appear, she , who before could rail,

At my neglect, now at my sight turns pale!

Yet why, fair maid, should you thus tim’rous be,

Or tremble at an urchin such as me?

Your faithful servant? Nay, were I inclin’d,

Say what could harm you? Could an elfin blind?

At length she bids: obedient to the fair,

Her flame I quench and upwards mount in air;

And oft the strains I chaunt while swift I rise,

Will reach her ears when far beyond her eyes; Joyful the maid with pain opprest no more,

Deems the worst part of this dread business o’er;

How weak mortality! Ah! Sanguine dame!

Quick I descend, perhaps relight the flame,

Add sevenfold fuel to the kindling fire,

Enjoy the blaze, and with a smile retire,

Fiercer than erst the gathering ruin grows,

Far brighter flames, and more infuriate glows!

Ye lovely maids to whom the lay belongs.

Who oft have smil’d, and oft approv’d my songs,

Vain the attempt at permanent disguise,

For what to[o] dark to [e]scape your piercing eyes?

Much less the simple tale which now I sing,

A flimsy covering to a noted thing;

Draw off the shade, my name and merits know,

Full soon declare me, for full well ye know. In the long preamble, there is also a reference to a "Popinaria," which Google tells me means "barkeeper" in Latin, maybe a lady who manages a pub. The riddle also suggests it was common for sweeps to whistle or sing at their work, but who knows. Maybe the acoustics of a chimney are excellent.

I submit that a ladies' magazine would not place a riddle that alludes to a fair lady needing a "cure" if the implication was that she needs to be cured from venereal disease. So here we have a riddle that is very similar to the Kitty riddle, but which has an innocent meaning.

When drawing conclusions about the Kitty riddle, we should study the riddle in the context of its times, not our own.

The chimney-sweep walks serenely through a crowded London street because everyone stays away from him. "Grievances of London," 1812, British Museum.

Previous post:

Shelley's "singular stories"

The chimney-sweep walks serenely through a crowded London street because everyone stays away from him. "Grievances of London," 1812, British Museum.

Previous post:

Shelley's "singular stories"

Published on August 03, 2023 00:00

July 27, 2023

Tremadoc#3: Shelley's "singular stories"

This is the third post in a series about the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his dubious version of an assault that supposedly occurred in February 1818 in the town of Tremadog (formerly Tremadoc) in North Wales. For the first post,

click here.

Shelley's biographer Richard Holmes believes that an assault did occur. I don't, and here I explain why I don't believe Shelley.

This is the third post in a series about the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his dubious version of an assault that supposedly occurred in February 1818 in the town of Tremadog (formerly Tremadoc) in North Wales. For the first post,

click here.

Shelley's biographer Richard Holmes believes that an assault did occur. I don't, and here I explain why I don't believe Shelley.

Tremadoc, or Tremadog, circa 1865 Shelley's "singular stories"

Tremadoc, or Tremadog, circa 1865 Shelley's "singular stories"The morning after the mysterious attacks, the Shelleys fled to a nearby government official, the solicitor-general, who put them up until Shelley's publisher sent them some money to book passage to Ireland. (That's how broke Shelley was). Shelley was nearly prostrated with nerves. He and Harriet learned of the slanders from Tremadog accusing Shelley of fleeing to avoid his debts and renege on his promises of financial support for the embankment project. Although it was true that Shelley was leaving unpaid debts behind him, including his rent, the Shelleys were highly offended that their veracity was called into question concerning the attacks.

As we have seen, it was Harriet who responded to the slur that Shelley had faked the attacks, writing a letter to Shelley’s publisher and to his other close friends, giving Shelley's version of events on his behalf. In her letter, Harriet also named the man Shelley blamed for instigating the attack, the chief labour contractor for the embankment project, Robert Leeson. William Madocks, booster of the Tremadog embankment project, had initially welcomed Shelley's involvement as a well-connected and well-spoken son of a baronet and member of parliament. But as Shelley made himself known to the small community of gentry in the area, they realized how radical his political views were. Leeson thought Shelley would bring discredit to the embankment project. Leeson was a High Tory; during Shelley’s brief stay in Tremadog, political and personal animosity had arisen between them. Harriet boasted that Leeson was refused entry into their house on account of his support for the politicians that Shelley despised. Leeson reciprocated the disdain, and in fact sent a copy of Shelley's printed speech about Irish emancipation to the authorities, to alert them to his radical views (they already knew).

Would Leeson have hired English-speaking thugs to go up to the house and fire off their pistols at Shelley? He definitely wanted to drive Shelley out of Tremadog, but what would have been the best way of doing it, supposing that Leeson was a man of more than moderate intelligence, which he was? It makes no sense

I think the entire episode as described by Harriet is melodramatic and improbable.

It is the hypothetical assailant’s point of view I’m trying to understand here. You pick a miserably wet, moonless night to go up to Shelley’s house on the hill. You enter, with or without taking your shoes off, and, as per the theory of Richard Holmes, Shelley's biographer, you search around in the pitch darkness for samples of Shelley's radical writings to be used to prove that he is a seditious traitor.

You hear approaching footsteps, or perhaps you hear Shelley's voice calling out, "who's there?" You head for the window. Shelley appears. Instead of legging it, you turn back and fire a shot at Shelley, escalating your crime from housebreaking to attempted murder.

Did Shelley's assailant wear a mask like these 18th century housebreakers? Notice that they are in their stocking feet. One of the burglars carries a candle, otherwise they wouldn't be able to see anything, and he's ready to point that pistol if the sleeper wakes up. But this means his hands are occupied. The other man's hands are free so it makes sense for burglars to work in pairs. If you're in your stocking feet, you've left them behind, though of course Harriet doesn't mention strange boots or footprints. Shelley pursues you--you succeed in knocking him down, but instead of running, you stay and grapple with him on the lawn. He manages to keep hold of his second pistol and he shoots you in the shoulder. You speak, thus giving him a chance to identify you by the sound of your voice. Of course, after this encounter, he could handily identify you as a man with a bullet wound. There were no reports of a wounded man seeking medical help in Tremadog.

Did Shelley's assailant wear a mask like these 18th century housebreakers? Notice that they are in their stocking feet. One of the burglars carries a candle, otherwise they wouldn't be able to see anything, and he's ready to point that pistol if the sleeper wakes up. But this means his hands are occupied. The other man's hands are free so it makes sense for burglars to work in pairs. If you're in your stocking feet, you've left them behind, though of course Harriet doesn't mention strange boots or footprints. Shelley pursues you--you succeed in knocking him down, but instead of running, you stay and grapple with him on the lawn. He manages to keep hold of his second pistol and he shoots you in the shoulder. You speak, thus giving him a chance to identify you by the sound of your voice. Of course, after this encounter, he could handily identify you as a man with a bullet wound. There were no reports of a wounded man seeking medical help in Tremadog.You escape into the darkness. So now you are aware that Shelley has pistols. Why would you return in the dark of night to try a second attack? Do you intend to murder him, after he's had a chance to describe you to everyone in the household? You give up your element of surprise by punching a hole in the window with your pistol or your fist, perhaps because you're unaware that lead bullets fired at close range can pass through glass. You fire at Shelley, and miss. You run away again when Shelley thrusts a sword through the window at you.

Was all of this necessary? Couldn't the Shelleys have been intimidated into leaving Tremadog with an anonymous threatening letter or two, or maybe a sheep's head thrown on the porch for good measure? At least, wouldn't you start with something like that and then escalate if need be?

Regency night attire Forced to make up more lies

Regency night attire Forced to make up more liesLet's go back to that interval between the first assault which happened at 11:00 pm and the later assault which happened around 4:00 am. Let's suppose that the conversation in the Shelley household came around to the necessity of gathering evidence to present to the local magistrate of the near-deadly assault on Shelley. This catches Shelley off-guard, as he anticipated that everyone would just go pack up their things and get ready to leave town by first light once he told them about the assault. He is used to having his wife believe anything he tells her, but at least one other member of the household, we might surmise, is showing skepticism or wants to investigate and bring the assailant to justice.

Dawn is six hours away and soon the entire household will be assiduously searching inside and out for physical clues in the morning light. If he had lied about the first incident, Shelley would have been in a real quandary at that point. For the first fabricated incident, he claimed that the assailant shot at him and missed while inside the house, and therefore, his listeners reasoned, that bullet must have lodged somewhere. As his biographer Richard Holmes acknowledges, nobody ever claimed to find a bullet in the billiard room or in the smaller room called "the office." Shelley was therefore compelled to improvise a second act in his drama to amplify the supposed danger and he needed to manufacture some physical evidence.

Shelley sent all the women to bed, but the loyal Dan Healy insists on staying up to help guard the house, and since he intends to guard Mr. Shelley, he sticks by Mr. Shelley like glue. For three hours, Shelley is chatting with Dan but he's feverishly thinking about how he's doing to stage a second attack with Dan right at his elbow. Finally he thinks of an excuse to send Dan out of the room, and not just to the adjoining room but to do something that will require him to go to the other side of the large villa. As soon as Dan's footsteps fade away, Shelley sprints to a window at one corner of the room. He grabs the window curtain and the skirt of his nightdress, holds them up, and fires his pistol through them, perhaps angled in such a way as to hit the wainscoting on the adjoining wall. When Dan Healy comes running back, alerted by the gunshot, he sees Shelley bashing his sword around a jagged opening in the window. Shelley explains that he was fighting off the intruder. As soon as Harriet arrives, he shows her the physical evidence and says that had he been standing broadside at the window instead of sideways, he surely would have been killed.

Now Shelley has demonstrated that the household is under attack by determined enemies who won't give up, and he has produced some physical evidence. It was enough to silence any doubts in his household, but not in the wider world.

William Godwin (1756 –1836) A man of principle

William Godwin (1756 –1836) A man of principleI conclude that Shelley staged the entire episode as an excuse to leave Tremadog to get out of his fervent promise to support the embankment project until his last breath, and also because he literally had no way to pay his rent, his servants, or his food and fuel bills--this in a time when creditors could arrest a debtor and send him to jail. Escaping his debts was a lifelong habit with Shelley, and apparently required no justification. But whenever he broke a solemn promise, such as breaking his marriage vows to Harriet, he always managed to persuade himself that it was because he was following a higher principle. In the case of Tremadog, he had impulsively involved himself in the project, then concluded that Madocks didn't deserve his support after all, and Leeson, who was in charge of contracting the labour, was an absolute brute. Therefore, it would have been unprincipled to keep to the commitments he'd made to support the project, no matter how publicly and how fervently he'd made them. And why should he pay rent or pay tradesmen's bills to a community that had betrayed him and turned against him, that refused to find and punish the assassin in their midst? And if they hadn't, literally, sent an assassin to kill him, if he had been compelled to manufacture the assassin, he was doing no more than symbolically illustrating the reality of his estrangement from the town leaders and their hostility to him.

In the case of ending his first marriage, which fell apart two years later, Shelley was following the higher principle of honesty when he left Harriet, then pregnant with their second child. He had fallen out of love with her, and fallen in love with 16-year-old Mary Godwin, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and his mentor and idol, William Godwin. He explained to his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg that by fulfilling himself with Mary, he was: "deeply persuaded that thus ennobled, [I shall] become... a more useful lover of mankind, a more ardent asserter of truth & virtue." Thus, Mankind would benefit from Shelley's adultery with teenage Mary Godwin. It followed that the obverse case was, if Shelley didn't commit adultery with teenage Mary Godwin, Mankind would pay the price.

Thomas Love Peacock (1785 – 1866) Shelley and the hat

Thomas Love Peacock (1785 – 1866) Shelley and the hatRationalizing your actions is one thing, and Shelley was a master at finding reasons why the self-serving thing he wanted to do was actually a highly principled action. But did Shelley, the apostle of truth and virtue, tell outright lies? His friend Thomas Love Peacock thinks he did. Peacock related an episode which occurred when he visited the poet at his temporary home in Bishopsgate in the early summer of 1816. By this time, Shelley was married to Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin.

Mary told Peacock that Shelley had just received a visit from a friend from Tremadog, Madock's trusted overseer John Williams, who had come all the way from Wales to personally warn the poet that his father Timothy Shelley was plotting to “entrap him and lock him up,” that is, have him declared insane and confine him. Once again, Shelley faced a crisis, for which the only thing to do was run and hide, even if it meant leaving behind unpaid bills for furniture, dishes, and the statues he'd ordered to decorate the library with.

Peacock was unconvinced, and said so. Mary left the room, and soon after, Shelley entered, hat in hand, as though just returning from a walk, and he affirmed that indeed, he had just come back from a long walk with his benefactor Williams. Peacock saw that the hat in Shelley’s hand was not Shelley’s hat, but his own hat, which he had left in the front hall upon entering the house. Peacock told Shelley to put the hat on, and it fell over his eyes, being much too large for Shelley’s notably small head. Shelley, nonplussed, said that he had carried the hat in his hand for the entire walk and so he hadn't noticed that he'd picked up the wrong hat from the front hall.

Shelley then insisted that Williams was staying at a hotel in London and offered to walk there with Peacock to prove he was telling the truth. Peacock agreed and they set off, but Shelley abandoned the walk half-way there.

Opera hat, Metropolitan Museum A few days later, Shelley claimed he’d received a letter from Williams containing a diamond necklace. He could not show the letter to Peacock, he said, but he could show the necklace. “Surely," said Peacock, "your showing me a diamond necklace will prove nothing but that you have one to show.”

Opera hat, Metropolitan Museum A few days later, Shelley claimed he’d received a letter from Williams containing a diamond necklace. He could not show the letter to Peacock, he said, but he could show the necklace. “Surely," said Peacock, "your showing me a diamond necklace will prove nothing but that you have one to show.”“Then,” said Shelley, “I will not show it to you.”

Mary professed to believe Shelley, Peacock could not.

A quote from Shelley biographer Richard Holmes is apropos here: "Shelley could be very unscrupulous in adjusting the truth when the need arose. What is most disturbing is that it is difficult to tell how far Shelley really realized — or admitted to himself — what he was doing."

Another fact to note is that Shelley had a habit of being suddenly and violently attacked by strangers just prior to removing from one place to another. In January 1811, a year before the events in Tremadog, Shelley and Harriet were living in a cottage in Keswick, near the poet Robert Southey. Shelley claims to have answered the door and been instantly knocked down by a stranger, who disappeared when the landlord, who lived nearby, responded to the commotion. Shelley and Harriet left Keswick for Ireland early the next month. When Shelley was in Italy in May of 1819 and going to the post office to get his letters, he claimed that a tall English officer, upon hearing his name, exclaimed, "What! Are you that damned atheist Shelley?" and knocked him to the ground. Biographer James Bieri adds that Shelley initially said his attacker in the post office was none other than his nemesis from Tremadog, Robert Leeson, and therefore they had to move immediately. Another early biographer, William Michael Rosetti, comments: "This is another of the singular stories told by Shelley, and discredited by most of his hearers or biographers." Tremadog aftermath

No assailant was ever caught. The local officials investigated the crime (remember that in those days there was no such thing as a police force, especially in a small Welsh village, and the local magistrates were the local gentry, often serving in voluntary positions). According to John Cordy Jeaffreson, they concluded that Shelley made the whole thing up and the bullet mark on the wainscot could not have been made by someone firing from outside the window into the house. (Again, others have quibbled over this, but...) Richard Holmes surmises that the authorities in Tremadog thought the best thing for all concerned was to hush up the scandal. Capital always flees from uncertainty, and they wanted the project to go ahead. Despite his private protestations to his friends, Shelley also had good reason for burying the whole thing. But months later, he told Mary Godwin's sister Claire that he was worried about walking the streets of London, for fear Robert Leeson would come up and stab him with a knife.

As Holmes notes, Shelley was personally and impulsively generous but: "one has the impression that he owed rather more than he gave away." Before leaving England for Italy, Shelley did make half-hearted attempts to pay off his Tremadog and other debts. It appears that whatever funds were set aside for paying them was not sufficient. One of his Tremadog creditors wrote that Shelley lied about the extent of the debts he'd left behind in Wales: "he is actually guilty of abundant falsities... did you ever hear of a more ungrateful fellow!"

What did Dan Healy see? "Ungrateful and insolent:" the silencing of Dan Healy

What did Dan Healy see? "Ungrateful and insolent:" the silencing of Dan HealyWhen we ask whether both of these attacks were faked, the circumstantial evidence points away from implicating Healy as the antagonist or a hoaxer, and towards the possibility that he was either a confederate or a dupe of Shelley's. I am leaning towards dupe.

Shelley appears to have been considerate enough to Dan Healy insofar as while Dan was in prison for following Shelley's instructions, Shelley did not decamp from Tremadog, leaving no forwarding address, which was his usual method of avoiding his creditors. Had Shelley done so in this case, Healy would have been left stranded without a job, without a character reference, and probably with no money. So the day after Healy’s return was the earliest possible date that Shelley could have left Tremadog and still done the decent thing by Healy, and that is when he in fact left.