Lona Manning's Blog, page 12

February 21, 2023

CMP#132 Nobility Run Mad, conclusion

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#132 Some nobility, but mostly Bristol vulgarity

In the last post, I introduced the 4-volume novel Nobility Run Mad, or, Raymond and His Three Wives (1802) as an example of the way Bristol merchants were portrayed in the novels of Austen’s era. I got as far as the middle of volume 3, when our noble hero Lord Raymond finally meets our heroine Theodosia.

In the last post, I introduced the 4-volume novel Nobility Run Mad, or, Raymond and His Three Wives (1802) as an example of the way Bristol merchants were portrayed in the novels of Austen’s era. I got as far as the middle of volume 3, when our noble hero Lord Raymond finally meets our heroine Theodosia. Although the title promises the reader a story about nobility behaving badly, Lord Raymond's dissolute dad was just part of the backstory. In this book, we get more emphasis on portrayals of uncouth, small-minded people from the merchant class of Bristol, namely, miserly old Mr. Filmore, his grandson Samuel, and their friends the Middletons who have Theodosia in their clutches. That’s great for my purposes. I am exploring the hypothesis that in the novels of the long 18th century, the objection to Bristol merchants—such as Mrs. Elton’s father in Emma—is not that they were involved in the slave trade, it’s that they were not genteel. In the novels I've been exploring, Bristol merchants and their families are used as comic characters, as foils to the heroine, because of their vulgarity and presumptuous attitudes.

To return to the novel: It seems our (anonymous) author found her comical and villainous characters to be intrinsically more interesting than her hero and heroine. Lord Raymond, says sententious things like: “It would very ill become me, Mr. Milner, to arraign my father’s conduct…” (Even though his dad was a complete waste of space who gambled away large fortunes before dying young in France and leaving huge debts behind him.) We have a sentimental storyline with Lord Raymond and Theodosia, but the more energetic storyline involves the Filmores. Young Samuel elopes with Lady Arabella, a scheming noblewoman. He assures Lady Arabella that Lord Raymond is dying, which means Samuel will succeed to the title. Samuel wants to get his hands on her fortune. Lady Arabella wants to get married to Samuel before he finds out she doesn’t have a fortune...

A repentant Arpasia leaves her lover Show me the money

A repentant Arpasia leaves her lover Show me the moneyIt's often remarked that Jane Austen’s characters are preoccupied with money. Boy howdy, they've got nothing on the characters in this book! Page after page after page of discussions of wedding settlements, proposals and counter-proposals, key documents destroyed, wills altered. The shenanigans of all the characters were interesting, but the extensive passages about money got tedious.

On the hero/heroine side, there were no serious impediments to their romance once a Swiss physician summoned by the devoted Mr. Milner cured the hero. When Lord Raymond is well enough to pursue the lovely Theodosia to Paris, he realizes he’s very much in love with her. But soft! who is she walking with the gardens? Who is that cloaked figure hanging on her arm? Why, it is none other than Arpasia, his ex-wife, who is dying of grief and remorse because she cheated on the best of husbands.

Lord Raymond whisks the ladies into a convent, mostly to protect Theodosia from her guardian, Mr. Middleham, who trying to pressure her out of her East Indian fortune. Defeating Mr. Middleham’s machinations gives our hero something to do, but it brings us another heavy dose of wills, jointures, and settlements.

Suffice it to say that everything works out. Not for Arpasia, obviously. She dies penitent, and her father “rather rejoiced than grieved to hear she was no more.” That sounds extreme, yes, but not much more extreme than Mansfield Park, when Fanny Price supposes the whole family might wish to die of chagrin and horror: “the greatest blessing to every one of kindred with Mrs. Rushworth would be instant annihilation.”

Lord Raymond and Theodosia are married, and they leave the vulgar Mrs. Middleham behind in Paris. They go back to England where Lady Arabella and her mother are horrified to learn that Lord Raymond is alive and well and spoken for, while Lady Arabella is shackled to Samuel. [Lady Arabella's mother] unthinkingly said she believed this was the first instance of a planter’s daughter marrying the heir to a Dukedom.

Filmore, who rejoiced in contradicting her, said, though he could not immediately bring proof that there had, there were many ladies in England married to Noblemen of lower extraction than [Theodosia], whose mother was the daughter of a Baronet, and her father was a man of some family… ‘So pray, my Lady,' he continued, 'don’t hold traders and planters in such contempt, for I must suppose, if you despise the people, you will disdain money got in that way. Mine, for instance, has been got by the sweat of my brow, and I have the liberty of disposing of it as I please at my death, which is more than some titled folks can do.' Yes, the Countess is exceedingly interested in Mr. Filmore's money and she keeps urging him to settle fifty thousand pounds on his new granddaughter-in-law. Despising traders and planters, but taking their money, can hardly be passed off as a moral stance against West Indian fortunes.

The story doesn't end with the marriage of Theodosia and Lord Raymond. Two more surprises await the reader. One major character in this book is not who he claims to be, and another major character is not who he thinks he is.

Sailors tussle with prostitutes after arriving in the harbour Spoiler Spoiler Spoiler

Sailors tussle with prostitutes after arriving in the harbour Spoiler Spoiler SpoilerMr. Milner, the older travelling friend and companion of young Samuel and then Lord Raymond, turns out to be their father! The dissolute nobleman didn’t die in disgrace in France, he faked his death, went out to India, got an East Indian fortune and came back to lead a reformed life. Nobody recognized him because he had a bad case of smallpox and his face was all scarred. The East Indian fortune is not placed in the moral scales against him. Nor does he need to die to atone for his past errors, unlike Arpasia.

Next, we learn that Samuel isn't really Lord Raymond's half-brother. On her deathbed, old Mr. Filmore's wife confesses that Samuel is a changeling—secretly popped in to the cradle to replace a dead infant (that is, the child of the dissolute nobleman and Filmore's daughter Betsy). As Filmore tells Lady Arabella: “Your husband has come out to be the son of one of my sailors, and of my wife’s [secret] bastard daughter, who is no better than she should be, you find; nor am I the first old fool that has been cheated…” That explains why Mr. Milner and Lord Raymond couldn't improve Samuel's manners or morals. He came from lower-class stock. Morality served up

The novel concludes: “Having thus brought our history to a conclusion, we can only say it was written to inculcate the hackneyed maxim that honesty is the best policy; which we hope is exemplified by the various characters we have brought into action, and punished or rewarded according to their deserts, or, to the best of our judgment, as they have abided by, or departed from our favourite maxim."

I don’t know—that rather lacks conviction, I think. True, young Samuel and his titled wife are comically caught in a marriage founded in fraud on both sides. But on the other hand, you have a major character who spends the entire novel masquerading as “Mr. Milner” when he’s really a formerly dissolute nobleman, and he’s presented as a good guy.

The characters in this book get their just deserts according to 18th-century novel morality. I suspect the authoress was writing to meet what the Feminist Companion to Literature in English describes as "romantic orthodoxy." I'm struck by the fact that none of her three novels contain a foreword, and forewords were typically where the author assured the reader that the novel in their hand excoriated vice and promoted virtue. Our authoress, like Austen, just plunges into her story for her first two novels without making this pro forma declaration, as though she refused to comply with the trite and expected disclaimer. The author’s only preface, in Nobility Run Mad, is a sprightly little piece, written in the first person, about a trip to a lending library with a friend, in which gets to overhear the patrons, all women, talking about her novels.

Innocence Between Vice and Virtue, by Marie-Guillemine Benoist, 1790 What was this author's background?

Innocence Between Vice and Virtue, by Marie-Guillemine Benoist, 1790 What was this author's background? As I mentioned in my last post, we don't know the identity of the author of Nobility Run Mad but she identified herself as a young woman. All three of her novels are set, at least in part, on the continent before the time of the French Revolution. She tackles scenarios, such as life aboard ship, the boulevards of Paris, and life in the army, which Austen never ventured to portray, and she makes references to real places such as Wesley’s chapel and St. Michael’s Hill in Bristol. She very probably was of the middling gentry, although she wrote about dukes and earls and marquises. She is respectful in her portrayal of French Catholics, a Quaker merchant, even a Jewish widow. She is contemptuous of Methodists. She follows the conventional morality of her times, but the sole review of this novel in the Annual Review criticized her for giving too many details of Arpasia's adultery. “[I]mproper subjects for young and innocent minds.” Her bawdy joke about the castrati slipped through.... Bonus Castrati Joke

“One of those men there that sing like women, who taught Dousy [Theodosia] at Florence, used to praise her voice up to the skies; [says Mr. Middleham] he was what they call master of his trade, and he had paid dear enough for his voice, God he knows!”

“For shame, Mr. Middleham, for shame!” cried his [wife], alluding to the poor man’s misfortune; “before my daughter!” But you have no more manners than a horse. Senor Carlini had a delightful voice; no one, not even Dousy ever pleased me so much.”

“Well, there is no accounting for taste, Mrs. Middleham,” [her husband quips] “I only know that I could never please you yet, though I am rather more of a man even now than your favourite Senor.”

Samuel made no scruple of laughing aloud… and it was with the utmost difficult the Marquis and Milner refrained from joining him, while Theodosia scarcely knew which way to look, so much was she confused. To relieve her, the Marquis petitioned for a second song; she readily obliged him with a very fine Italian air of Sacchini, and concluded with Handel’s ‘Sweetly soft in Lydian Measures.’” Nobility Run Mad received unenthusiastic praise. “The invention, character, and language are, in many places above mediocrity, seldom below it.” I'd agree with that. I've read worse 18th century writers. Our author tends to very long sentences but she still has a brisk and lively style, she obviously enjoys giving voice to her vulgar characters, and the action unrolls smoothly until we get to the third and fourth volumes with their preoccupation with money. To conclude with where I began: If we look at Mrs. Elton in isolation, naturally our thoughts, as modern readers, turn to her Bristol connection with the slave trade. Scholars and readers in the Jane Austen communities, to say nothing of the wider world, have raised awareness of the historical connection between Bristol and the slave trade, and while earlier analysts of Austen didn't raise the topic, it's certainly front and center today.

But if we look at Mrs. Elton in the context of novels of her time, I think she is an exemplar of a comic type (except of course Austen's writing is so superior).

My research into this is ongoing.... more examples to follow. Last post: Nobility Run Mad, part 1

Published on February 21, 2023 00:00

February 13, 2023

CMP#131 Book Review: Nobility Run Mad (1802)

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.This post is about a forgotten four-volume novel, and is part of an exploration of portrayals of merchants from Bristol and their families in novels of this period. I'm interested in this topic because of Mrs. Elton. CMP#131: Nobility runs mad (and Bristol merchants are vulgar and avaricious) In Emma, we’re told that Mrs. Elton's father was a Bristol merchant. This is narration filtered through Emma’s point of view (emphasis added) She brought no name, no blood, no alliance [to her marriage with Mr. Elton]. Miss Hawkins was the youngest of the two daughters of a Bristol — merchant, of course, he must be called; but, as the whole of the profits of his mercantile life appeared so very moderate, it was not unfair to guess the dignity of his line of trade had been very moderate also. Part of every winter she had been used to spend in Bath; but Bristol was her home, the very heart of Bristol; for though the father and mother had died some years ago, an uncle remained—in the law line—nothing more distinctly honourable was hazarded of him, than that he was in the law line.

Mrs. Elton's first appearance in Highbury was at church.

Mrs. Elton's first appearance in Highbury was at church.

Yes, Emma is being a snob, but Mrs. Elton lives down to her expectations: she is comically inappropriate in social situations, pushy and obnoxious.

Yes, Emma is being a snob, but Mrs. Elton lives down to her expectations: she is comically inappropriate in social situations, pushy and obnoxious.This is no less than what a reader of the time would expect, because Mrs. Elton's father was a Bristol merchant. I'll explain presently.

First, what does Austen's little dash between “Bristol” and “merchant” signify? You can almost hear the the dismissive snicker. is Austen hinting that Mrs. Elton's father was a slave-trader? (cont'd) Bristol and the slave trade

Bristol prosperity in the 18th century was built upon the slave trade. We know plantation owners were called "planters," but were slave-traders called "Bristol — merchants"? I imagine they were called "traders." If I find definite answers to that, I'll let you know.

Saying that Mr. Hawkins did not conduct a "dignified" line of trade is not a very effectual or precise way of accusing him of inhumanity, though. And why say that his income was "moderate"? Should he have done more slave-trading? I just don't see these remarks as pointing toward slave-trading, though certainly he must have been participating in the related economic sphere. I mean, if he was a Bristol merchant, then of course he was at the very least an indirect beneficiary of the slave trade. I think it indicates that he was, in Emma's eyes, just someone who owned a warehouse or shop.

As I read Emma's reaction, her snobbery is not focused on any connection to the slave-trade; Emma is throwing shade because the Hawkinses are not landed gentry; they are people of low origin involved in grubby commerce. Bristol Merchants in novels

To place Mrs. Elton in context, let's look at other novels which feature Bristol merchants and their families. My sample size is small, but so far, the Bristol merchants I’ve encountered in the fiction of this era were not held up to criticism for being involved in the slave trade. No, that was not the thing that made them contemptible or laughable in the pages of a novel. It was their lack of breeding.

That brings us to the 1802 novel Nobility Run Mad: I decided to plow through all four volumes, not because I was interested in another story about the nobility behaving badly, ( they usually behave badly ), but because this book came up in a search for novels of this era that featured the words “Bristol” and “merchant.” I wanted to see if this novel, like some others I’ve read, portray Bristol merchants as being vulgar. Bristol Merchant as a Comic Scrooge: Backstory I

The first Bristol merchant we encounter in Nobility Run Mad is a Mr. Samuel Filmore, a successful but small-minded and miserly importer and exporter. In the opening chapters of the novel, we hear Mr. Filmore’s backstory related by a neighbour. Filmore’s parents were humble labourers. Sam was able to go to a charity-school and at sixteen he got a job as a clerk. In time, he married his employer’s widow, and after she died, he made another advantageous marriage. He acquired enough of a fortune so that his daughter Betsy attracted the attention of a young nobleman. Star-struck, Filmore handed over a dowry of £140,000. He didn't know the Marquis had already gambled away his own patrimony, as well as his first wife’s dowry. Betsy's riches disappeared the same way, at the gaming tables, to Filmore's lasting chagrin.

We might admire Mr. Filmore for his climb from rags to riches in a highly stratified society and the fact that he doesn't gamble away his fortune, but no, he’s a comic villain. Not because he is tangentially involved in the slave trade, but because he is of low origin; he is tight-fisted, close-minded, and uncouth. And --bonus sneer points: he’s a Methodist. Being a Methodist in this instance means that he relies on faith to get him to heaven and not good works, and therefore he needn’t trouble himself about the poor. (For more about how Methodists were portrayed in novels of this era, see here.)

Thus we have a novel, written at the same time as other novelists were writing abolitionist novels, which editorializes about a great many things:It’s bad (and comical) to be uncouth.It’s bad to not pay your debts and to be dishonest in money matters.It’s bad to smuggle French goods into the country to avoid paying taxes.It’s bad to be too severe with your children, because they’ll rebel. And as the story develops, we'll add more strictures to the list:It's bad to make fun of Catholics.It’s bad (very, very bad) to commit adultery.

Samuel Filmore "was, from nine years old to sixteen, a Blue-coat-boy in that excellent school, founded by that most charitable of men, the late Mr. Coulston, of generous memory.”

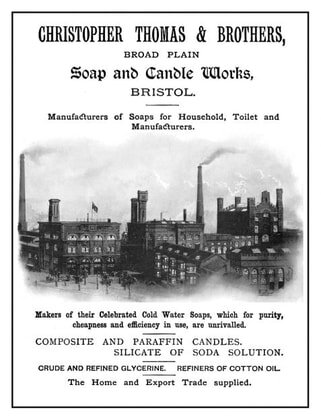

Samuel Filmore "was, from nine years old to sixteen, a Blue-coat-boy in that excellent school, founded by that most charitable of men, the late Mr. Coulston, of generous memory.” This is a reference to Edward Colston, now infamous as a slave-trader, whose statue was recently tipped into Bristol harbour. (Staffordshire figure of a "Colston Boy Bristol") But this book is silent on slavery. It's not mentioned, condemned, or defended. It's an invisible fact of life underlying the vast fortunes which are an integral part of the plot.

References to hogsheads of sugar, to trading ships arriving in harbour--this is presented in a matter-of-fact manner. The praise of the philanthropic Mr. “Coulston,” i.e. Edward Colston, the biggest slave trader in Bristol, tells us that opinions have changed since 1802. Further, the author of this book conjures up vast fortunes as needed for her plot from the East and West Indies. Two characters in the book acquire their riches in East India. Mr. Filmore marries a West Indian heiress. His son-in-law spends his wife's West Indian inheritance at the gaming table. His grandson marries a West Indian heiress. And by "West Indian heiress" I don't mean a woman of color like Miss Lambe in Sanditon. The only reference to a person of color in the novel is a joking reference to a soap advertisement showing a man trying to scrub a "blackamoor" white.

Other novels of this same period, some of them from the same publisher, were written from an abolitionist point of view. It goes to show that opinions varied on this subject, from support to indifference to outrage, but you could still be an accepted member of society at this time and view slavery as a fact of life and use a West Indian fortune as a plot device, not as a political statement.

Off to France!

Off to France!After all the opening exposition, in which fortunes are acquired and lost and wives and useless noblemen die, we have a wealthy gentleman named Milner who is planning a long trip to the continent for his health. He hears about Mr. Filmore’s grandson, the orphaned offspring of Betty and the dissolute nobleman. This grandson, also called Samuel Filmore, has an older half-brother by his father's first marriage. Despite the fact that young Samuel is rightfully Lord Samuel, a member of the nobility, he's been ignored by his paternal grandfather and brought up in Filmore's counting house. Our wealthy stranger, out of pity for Samuel, takes him along to France so he can acquire the kind of cosmopolitan polish he'll need if he ever wants to fit in with his late father’s relatives.

Though published in 1802, the story is set in the year 17---, that is, some vague year before the French Revolution. France is chock-a-block with aristocrats and the Bastille is a notorious prison but there is no political foreshadowing in this novel. Instead, we have a lot of dialogue from the loquacious young Samuel. You can take the young man out of Bristol, but it’s going to be uphill work taking the Bristol vulgarity out of the young man. He is selfish, self-satisfied, and parochial in his outlook. He has no interest in art or culture, and he’d rather save a guinea than spend it.

Milner and Samuel are staying at an Inn in Saint-Omer on the way to Paris. Looking out the window, Sam admires an exceedingly handsome carriage with an entourage of horses and servants. Samuel admires the coat of arms on the carriage. They apply to a servant for information and Sam learns that the traveler is his own noble half-brother, Gustavus Osmond, the Marquis of Raymond. But he doesn't get a chance to meet him. (Ahem, Janeites, does this remind you of anything?)

An adultress leaves her husband shackled in the stocks. He has taken a viper to his bosom. Backstory II

An adultress leaves her husband shackled in the stocks. He has taken a viper to his bosom. Backstory IILord Raymond's first wife was “the widow of a Jew merchant, whom report made out to be worth a million.” In the first iteration of the story, this sounds pretty callous but later, Lord Raymond tell his own story which softens the details. The widow fell in love with him. The marriage was a transactional one but he had affection for her. The marriage gave him, at 19, independence from his grandfather the duke so he was free to do what he was longing to do--pay all of his late father's debts so he could restore the family honor. After his first wife died (and nothing unusual about that, wives drop like flies in this book for the convenience of the plot), he married again. Arpasia Ermington was a beautiful girl of good family but she was unfaithful to him so he divorced her. He fought a duel with his wife’s seducer, survived his injuries, but has been in poor health ever since, mostly because of the shock and heartache of the faithless Arpasia’s betrayal. HIs only pleasure in life is in doing good for others. Our story resumes

For example, during his brief stay in Saint-Omer, the Marquis learned of an Englishman and his wife who have been imprisoned for debt. He generously pays off their debts in full and gives an additional sum to help the stranded couple.

Samuel thinks his noble brother was naïve: “I think I know how to make a good bargain better than the Marquis. I am rather more up to things of this kind; so in my Lord’s place, why I would have sent for all these here French creditors, and when I had got them all together—‘Now, gentlemen,’ says I, (always give such low traders a little palaver when one wants to make a good bargain—it is granddad’s maxim, and a very good one) ‘now gentlemen, what is your demand,’ says I, ‘upon my countryman?’ They all tell me, of course—‘Well then,’ says I laying a good round sum upon the table before me, just to set their mouths a watering, ‘there,’ says I, ‘lays the money as you see. Now what are you willing to take?...I will give you half the sum he owes you, if you will all give a proper receipt for the whole; and if you won’t comply with my terms, why he must starve in prison; that’s all I have got to say, for depend upon it, you will never have so generous an offer again. A prison never pays debts, you know: so I should think, gentlemen, if I was in your places, that half a loaf is better than no bread, and I ain’t obliged, you know, to give you a single sixpence…" etc. etc At any rate, and despite his mercenary first marriage, Lord Raymond is the hero of our story. Mr. Milner is disappointed to see that Samuel is clearly interested in his older half-brother's visible decline. Lord Raymond's death would elevate Sam to the peerage.

headless gothic squirrel in Germany On to Paris for some family drama

headless gothic squirrel in Germany On to Paris for some family dramaMr. Milner and Samuel make the acquaintance of Lord Raymond in Paris and the young nobleman kindly acknowledges Samuel as his brother, despite Samuel's unprepossessing personality. The section set in Paris is taken up with Lord Raymond’s re-encounter with his faithless wife Arpasia, now the kept mistress of the army captain who seduced her. Everyone—Lord Raymond, her parents, her brother Lord Bewdly—are absolutely gutted by this turn of events.

Arpasia's father refuses to forgive her. And she turns down the suggestion that she enter a convent to atone for her sins. “I must be either happy, miserable, virtuous, or wicked, my own way.” We see her at her salon, playing the harp or bedecked with jewels in a box at the opera.

The Marquis resolves to try to forget her and move on. He joins forces with his uncouth half-brother and Mr. Milner (who turns out to be an old friend of his late father, who has reformed from gambling), and they journey together to the healthful climes of southern France.

They pause in the city of Dijon in Burgundy and rent a castle, which leads us into a gothic interlude. Or rather a gothic satire, because only young Samuel is affected by the rumors of ghosts and hauntings while Lord Raymond and Mr. Milner laugh at him. He is frightened by strange rustlings and movements in his bedroom, but it's only the housekeeper's pet squirrel. He listens to scary stories of a loup-garou (a French werewolf) prowling the castle at night. He decides to go out and kill it, and ends up shooting a goat.

It’s interesting the author chooses to make fun of gothic tropes, à la Northanger Abbey, because her publisher, Minerva Press, was a leading purveyor of blood-chilling gothic tales. Some academics have theorized that the reason the first publisher who bought Northanger Abbey held it back from publication was because it spoofed gothic novels which were very popular and he didn't want to give offense to the readers or writers of gothic novels. Here we have an example that you could have your gothic cake and spoof it, too. Another Vulgar Bristol Merchant

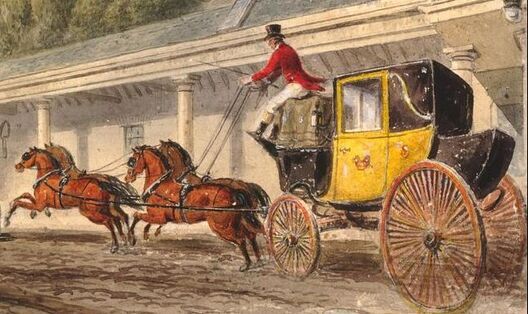

So far, apart from the dissolute off-stage antics of Samuel's late father in the backstory, we haven't had any nobility running mad. We do get more Bristol merchants, though. Walking around Dijon, Sam is surprised to encounter Mr. Middleham, another small-minded Bristol merchant, with his family. “He is a soap-boiler and tallow-chandler, and in a devil of a line—exports and imports by wholesale,” Samuel explains. In other words, he renders animal fat to make soap and candles, a smelly and undignified trade. He's got people to do the boiling for him, of course. Even in 1802 you have the rise of factories and the mass manufacture of commercial items, the earliest glimmers of the industrial revolution.

Bristol was home to some large soap-making factories, or "soap works." Is "Mr. Middleham" a satire of a real soap and candle magnate? In the book, he's dishonest, miserly, coarse and vulgar. If that weren't bad enough, he's also a Methodist. Despite their wealth, the Middlehams live very frugally. While abroad, they stay in cheap lodgings. Mr. Middleham and Samuel’s grandfather had long planned to join Middleham’s ward Theodosia (known as Dousy) and Samuel in matrimony. There is yet another great fortune at play here, since Mrs. Middleham, who spends all her time quarreling with her husband, is the widow of “a great West India planter” and Theodosia is her step-daughter and heir to her late father's fortune. I presume Mrs. Middleham is specified as being a step-mother, not a mother, to explain how such a fat, ignorant, common, woman could be mother to such a lovely, accomplished girl. This is a book that sets a lot of store by bloodlines. Theodosia "cordially despises" them both and is just waiting until she's 21 and can get away from them.

Bristol was home to some large soap-making factories, or "soap works." Is "Mr. Middleham" a satire of a real soap and candle magnate? In the book, he's dishonest, miserly, coarse and vulgar. If that weren't bad enough, he's also a Methodist. Despite their wealth, the Middlehams live very frugally. While abroad, they stay in cheap lodgings. Mr. Middleham and Samuel’s grandfather had long planned to join Middleham’s ward Theodosia (known as Dousy) and Samuel in matrimony. There is yet another great fortune at play here, since Mrs. Middleham, who spends all her time quarreling with her husband, is the widow of “a great West India planter” and Theodosia is her step-daughter and heir to her late father's fortune. I presume Mrs. Middleham is specified as being a step-mother, not a mother, to explain how such a fat, ignorant, common, woman could be mother to such a lovely, accomplished girl. This is a book that sets a lot of store by bloodlines. Theodosia "cordially despises" them both and is just waiting until she's 21 and can get away from them. Samuel is complacent at best about the idea of marrying Theodosia. He does not put himself out to win her affections. Theodosia has been to boarding school and she can play and sing and draw and paint. Samuel says he is “no judge" of her talents but "I had rather my wife should know how to make a good pudding or a pie.”

Lord Raymond graciously invites the Middlehams to the castle for tea, despite their vulgarity and bickering, and so he and we meet Theodosia. Lord Raymond is instantly taken with her accomplishments, good sense, and beauty, and he pities her for having to put up with the Middlehams.

Hmm, so here we have a rich, handsome, high-born guy finding himself attracted to a young lady with vulgar relatives.

Elizabeth Johnson by Reynolds Lord Raymond can't resist inviting the Middlehams to stay with him at the castle so he can enjoy Theodosia's company. “who displayed as much knowledge as any female ever ought to aspire to, if she wishes to render herself an agreeable companion to the other sex.” Mr. Middleham is delighted to save money on food and lodging and they move into the castle promptly. It's obvious that Theodosia and Samuel are completely unsuited for each other.

Elizabeth Johnson by Reynolds Lord Raymond can't resist inviting the Middlehams to stay with him at the castle so he can enjoy Theodosia's company. “who displayed as much knowledge as any female ever ought to aspire to, if she wishes to render herself an agreeable companion to the other sex.” Mr. Middleham is delighted to save money on food and lodging and they move into the castle promptly. It's obvious that Theodosia and Samuel are completely unsuited for each other. Will Lord Raymond die of his wasting illness before he can find love and happiness again with the girl intended for his brother? Will Lord Raymond's grandfather, the Duke, succeed in promoting a match with a haughty noblewoman whom our hero doesn't love? Will the fascinating but fallen Arpasia survive to the end of the novel, or will she be paid out for her transgressions? And do Samuel’s manners ever improve? Next post....

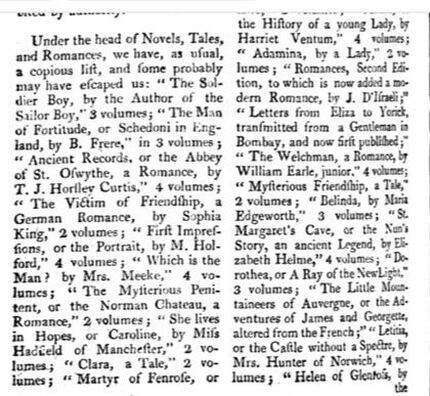

Just some of the many novels of 1802 The Anonymous Authoress

Just some of the many novels of 1802 The Anonymous AuthoressWe don't know who wrote Nobility Run Mad, except that she's also the author of The Sailor Boy (1800) and the Soldier Boy (1801). She is not Rosalia St. Clair, (real name Agnes C. Scott) a Scottish novelist who also wrote novels titled The Sailor Boy and The Soldier Boy three decades later.

Our authoress identified herself as the "author of" as Jane Austen did, (see opposite) but did not add "by a lady."

As we see in the listing of novels opposite, some female authors gave their names, such as "Miss Hadfield of Manchester." Sometimes you can't tell if the writer is a man or a woman as in "T.J. Hortley Curtis," some were "by a Lady," some mention no authorship at all, just the title.

Notice the publication of First Impressions, or the Portrait, which of course was Austen's first name for the novel that came out as Pride an Prejudice. Previous post: Plots and Plausibility

The Bristol Heiress and Strategems Defeated also feature Bristol merchants.

Published on February 13, 2023 00:00

February 7, 2023

CMP#130 Plots and Plausibility

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#130 Does Austen have secret, hidden, sub-plots?

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#130 Does Austen have secret, hidden, sub-plots?

Sir Felix adjusting himself after dallying with Ruby in the woods. My book club is reading The Way We Live Now (1875) by Anthony Trollope, so I was in the mood to re-watch the 2001 BBC mini-series with Matthew Macfadyen playing the irredeemably useless and selfish Sir Felix Carbury. In the novel, Sir Felix invests a lot of time into trying to seduce Ruby Ruggles, a working-class girl, who deludes herself that he will marry her. Sir Felix and Ruby meet secretly in the woods. He “got his arm around her waist,” he “talked of love,” but he dared not "ask her to be his mistress.” In the mini-series, however, Sir Felix and Ruby (played by Maxime Peake) do more than chat and kiss and cuddle.

Sir Felix adjusting himself after dallying with Ruby in the woods. My book club is reading The Way We Live Now (1875) by Anthony Trollope, so I was in the mood to re-watch the 2001 BBC mini-series with Matthew Macfadyen playing the irredeemably useless and selfish Sir Felix Carbury. In the novel, Sir Felix invests a lot of time into trying to seduce Ruby Ruggles, a working-class girl, who deludes herself that he will marry her. Sir Felix and Ruby meet secretly in the woods. He “got his arm around her waist,” he “talked of love,” but he dared not "ask her to be his mistress.” In the mini-series, however, Sir Felix and Ruby (played by Maxime Peake) do more than chat and kiss and cuddle.The mini-series version seemed more probable to me. Of course Sir Felix wouldn’t waste his time travelling down to the country to see Ruby, or take her out to the music hall in London, if she didn’t put out.

And I wonder whether Trollope’s readers would have assumed the same. Yet I don't see Trollope hinting that they actually have sex. When push comes literally to shove in the novel, Ruby screams for help. She goes on to marry respectably. Her complacent fiancé asserts that she is a good girl. I think if she wasn't, she would have been fated to die by the end of the story.

In Emma, Jane Austen references Goldsmith's short poem: "When lovely woman stoops to folly." I think Austen mentioned the "dying from shame" trope in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Recently, however, I’ve come across some examples of readers and critics arguing that there are some artfully hidden clues about sexual liaisons and love children in Jane Austen’s novels..

Hetty and Harriet. Miss Bates (Miranda Hart) and Harriet Smith (Mia Goth) in the 2020 adaption of Emma Did Jane Austen intend for her readers to understand that Miss Bates had an illegitimate child? Or that her younger sister did?

Hetty and Harriet. Miss Bates (Miranda Hart) and Harriet Smith (Mia Goth) in the 2020 adaption of Emma Did Jane Austen intend for her readers to understand that Miss Bates had an illegitimate child? Or that her younger sister did?“Nothing in the book remains a mystery if we read it carefully,” says Dr. Helena Kelly in Jane Austen: the Secret Radical. We know that Harriet Smith in Emma is the “natural daughter” of somebody. We learn at the end of the book that her father is a tradesman. But who is her mother? “Someone not altogether unconnected with the Bates family, perhaps,” Kelly suggests delicately. “Miss Bates twice refers to her mother calling her Hetty, which can be short for Harriet. Where other characters speak of ‘Harriet Smith,’ Miss Bates makes a point of never using Harriet’s first name… it’s not proof, but the indications seem to nudge us in the direction of concluding that Harriet and Jane Fairfax may well be half sisters."

That is, Miss Bate’s younger sister Jane married Lieutenant Fairfax, and they had a daughter, also named Jane. Lieutenant Fairfax died abroad and his widow sank “under consumption and grief soon afterwards" when little Jane was only three. But, perhaps before the unhappy Mrs. Fairfax died of tuberculosis, she had an illegitimate child with the well-off tradesman, and named the child after her older sister Harriet (aka Miss Bates). Young Harriet subsequently grows up in Mrs. Goddard’s boarding-school, never publicly acknowledged by either her father or mother’s family.

Another “Hetty” theory, first suggested in 1985 by Edith Lank, is that Harriet Smith is Miss Bates’s secret love child. This possibility has been bruited in Jane Austen fan fiction as well. Fan fiction, of course, can go in whatever direction the author chooses to take it, but the "Hetty" theories mentioned above have to do with what Austen herself intended.

A secret confinement? How secret, exactly? I just don’t see the connection between this plot complication and the actual plot of the novel. If Harriet Smith is Miss Bate’s unacknowledged daughter or niece, and we get to the end of the novel without the truth coming out, what, exactly, has been accomplished? What would a 19th-century reader make of that? What would a reviewer of the period make of that, given that they so very often stressed the moral lessons of the novel? In my opinion, Miss Bates is never presented as a hypocrite in Emma, never shown as a woman pretending to virtue but hiding a secret past. She is never held out as a woman nursing a secret sorrow and I can't think of any guilty or self-conscious interactions with Harriet. We're told of her "contented and grateful spirit" which she would not deserve, not in the world of the 18th- and 19th- century novel. That is, Austen and her publisher would think twice before giving the readers a woman who had borne an illegitimate child who was not racked with guilt and remorse, and who manages to be alive at the end.

A secret confinement? How secret, exactly? I just don’t see the connection between this plot complication and the actual plot of the novel. If Harriet Smith is Miss Bate’s unacknowledged daughter or niece, and we get to the end of the novel without the truth coming out, what, exactly, has been accomplished? What would a 19th-century reader make of that? What would a reviewer of the period make of that, given that they so very often stressed the moral lessons of the novel? In my opinion, Miss Bates is never presented as a hypocrite in Emma, never shown as a woman pretending to virtue but hiding a secret past. She is never held out as a woman nursing a secret sorrow and I can't think of any guilty or self-conscious interactions with Harriet. We're told of her "contented and grateful spirit" which she would not deserve, not in the world of the 18th- and 19th- century novel. That is, Austen and her publisher would think twice before giving the readers a woman who had borne an illegitimate child who was not racked with guilt and remorse, and who manages to be alive at the end. I had the same reaction after hearing Professor Robert Morrison’s talk at the recent JASNA convention in Victoria concerning Sense & Sensibility. He floated the idea that Austen intended for us to understand that Willoughby and Marianne had sex when they were supposedly touring his aunt’s house, and that Marianne’s subsequent illness was not a bad cold but a delivery or miscarriage of their secret love child. The reactions from the large audience ranged from, “oh, that’s an interesting idea,” to some serious pearl-clutching. Maybe I’ll delve into that more deeply another time.

In other novels of this era, the illegitimate child is not illegitimate after all, but the product of a secret marriage. Fallen women usually suffer a severe fate. Apart from the earlier Georgian novel The History of Tom Jones (1749), I’ve encountered only one novel where a well-born lady had an illegitimate child (Consequences, or the Adventures of Rraxal Castle, 1796). The “consequences” of the title refer to the inevitable death of this girl (and her misguided brother, in a separate plotline) which are presented as Heaven's judgement visited on the Earl of Rraxal because he neglected the moral education of his children.

I’ve encountered only one novel (Fanny Fitz-York, Heiress of Tremorne, 1818) where a girl from a good family ran off with her lover, sank into prostitution, and was forgiven and welcomed back home. Other such fallen women think too poorly of themselves to ever go back home, as in The History of Fanny Belton (1783), or they stumble home before they die, as in The Farmer of Inglewood Forest (1796).

Could any of Austen's characters have borne an illegitimate child and then gone about their lives, as Tom Jones's mother basically did? We are told that Austen did not approve of Fielding's writing. Her brother said, "She did not rank any work of Fielding quite so high. Without the slightest affectation she recoiled from every thing gross. Neither nature, wit, nor humour, could make her amends for so very low a scale of morals." We know from her own letters that she returned Madame de Genlis's novel Alphonsine (1806), to the lending library. Alphonsine is the story of an unwed mother secretly raising her love-child in a cave to which her husband has confined her. Austen wrote, "We were disgusted in twenty pages, as, independent of a bad translation, it has indelicacies which disgrace a pen hitherto so pure.”

Edmund Bertram objects to his sister Maria playing the lead in Lover's Vows because Agatha is an unwed mother. Colonel Brandon's lost love Eliza in Sense & Sensibility dies after having an illegitimate child, and this girl repeats her mother's unhappy fate, thanks to Willoughby. To the colonel, these are catastrophic events, and they are kept off-stage.

Yes, I should acknowledge the Lydia exception in Pride & Prejudice. Lydia engaged in fornication and suffered no consequences, apart from being stuck with “one of the most worthless men in Great Britain.” She doesn’t feel remorse and she doesn’t die. And if she has a bun in the oven on her wedding day, the child will be born legitimate, even if the gossips of Meryton count on their fingers and nod knowingly.

Yes, I should acknowledge the Lydia exception in Pride & Prejudice. Lydia engaged in fornication and suffered no consequences, apart from being stuck with “one of the most worthless men in Great Britain.” She doesn’t feel remorse and she doesn’t die. And if she has a bun in the oven on her wedding day, the child will be born legitimate, even if the gossips of Meryton count on their fingers and nod knowingly.Maria Bertram, as we know, does not get off so lightly for adultery in Mansfield Park. She is banished from all good society forever. There is no mention of a child, but I think it is reasonable to assume that this would be a consequence of living with Henry in the hope that he would marry her after her divorce from Mr. Rushworth.

Author Lucy Knight’s debut Austenesque novel makes the logical assumption that Maria had an illegitimate child. Knight's heroine, Henrietta Rose, is passed off by Maria and Mrs. Norris as an orphaned relative whom they have charitably taken into their home. Soon, young Henrietta is off to school and has many subsequent adventures in this fast-paced novel. Knight’s next, Lydia Wickham’s Daughter, is forthcoming from Meryton Press.

In my Mansfield Trilogy, Maria's affair with Henry also led to a problem pregnancy, but with different outcomes. Click here for more about my novels.

And again, these books are fan fiction, a sequel and a variation respectively, not a re-interpretation of Austen's intentions.

When it comes to plots and plausibility, I think people should ask themselves a few questions before formulating their theories and the first question is, given how exhaustively Austen has been scrutinized and written about, why hasn't anyone noticed these hidden sub-plots until the modern era?

Published on February 07, 2023 00:00

January 30, 2023

CMP#129 The East Room

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. She alone was sad and insignificant: she had no share in anything; she might go or stay; she might be in the midst of their noise, or retreat from it to the solitude of the East room, without being seen or missed. She could almost think anything would have been preferable to this. -- Fanny Price at her most Eeyore-ish in Mansfield Park CMP#129 About the East Room

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. She alone was sad and insignificant: she had no share in anything; she might go or stay; she might be in the midst of their noise, or retreat from it to the solitude of the East room, without being seen or missed. She could almost think anything would have been preferable to this. -- Fanny Price at her most Eeyore-ish in Mansfield Park CMP#129 About the East Room

Edmund and Fanny in the East room Our heroine Fanny is perplexed and distressed. She needs time for reflection--but before we get to those internal deliberations, Austen takes time to describe the contents of the East room in a way that she perhaps never does for any other room in her novels. She also explains how Fanny came to use it as her own private day-room, even though Aunt Norris will not allow the comfort of a fire. We learn what having this room means to Fanny. (the relevant excerpt is posted at the end of this blog for anyone wanting a refresher).

Edmund and Fanny in the East room Our heroine Fanny is perplexed and distressed. She needs time for reflection--but before we get to those internal deliberations, Austen takes time to describe the contents of the East room in a way that she perhaps never does for any other room in her novels. She also explains how Fanny came to use it as her own private day-room, even though Aunt Norris will not allow the comfort of a fire. We learn what having this room means to Fanny. (the relevant excerpt is posted at the end of this blog for anyone wanting a refresher).The East room is Fanny's refuge, her “nest of comforts,” even though it’s chilly and she has only battered school-room chairs to sit in and it’s decorated with drawings and furniture “too ill done for the drawing-room.” Here she keeps objects of sentimental value, like a sketch from her seafaring brother. She has her geraniums and her books. Fanny is a collector of books and she likes reading. In one scene set in the East room, Edmund awkwardly tries to segue out of an uncomfortable disagreement by talking about her books: “[Y]ou will be taking a trip into China, I suppose. How does Lord Macartney go on?”

He babbles nervously: “And here are Crabbe’s Tales, and the Idler, at hand to relieve you, if you tire of your great book. I admire your little establishment exceedingly; and as soon as I am gone, you will empty your head of all this nonsense… and sit comfortably down to your table. But do not stay here to be cold.” And poof! he’s out the door, down the stairs and down the hill to Mary Crawford at the parsonage...

Chinese standard bearer by William Alexander, official draftsman for McCartney's visit to China When Fanny first arrived at Mansfield Park as a frightened child, she had “never heard of Asia Minor.” Now she is reading a “great book:” the Embassy to China, Being the Journal Kept by Lord Macartney During His Embassy to the Emperor Chʻien-lung, 1793-1794.

Chinese standard bearer by William Alexander, official draftsman for McCartney's visit to China When Fanny first arrived at Mansfield Park as a frightened child, she had “never heard of Asia Minor.” Now she is reading a “great book:” the Embassy to China, Being the Journal Kept by Lord Macartney During His Embassy to the Emperor Chʻien-lung, 1793-1794.Edmund hopes the descriptions of the fabled, the almost mythical Orient in The Embassy will transport Fanny far, far away, so she'll have something more consequential to think about than his about-face on the propriety of private theatricals. Likewise, the descriptions of the East room have fired the imaginations of Austen scholars. As Kirstyn Leuner puts it: "Fanny Price’s East room in the Bertram estate attracts not only characters in Jane Austen’s 1814 novel Mansfield Park to knock on its door and peer inside, but literary scholars as well." While “there was no reading, no China, no composure for Fanny," contemplation of the East room has sent scholars on a quest for meaning, and lo, they return, not with tea and silk and spices, but with rich and subtle symbolism.

One scholar has drawn parallels between the power struggle between Fanny Price and the Bertrams and Lord McCartney’s negotiations with the Chinese emperor. Others see Mansfield Park as the British Empire in microcosm. “Intellectual history, material history that combines the social and the aesthetic, and Britain’s colonial geopolitical history coalesce in Fanny Price’s East Room…. Fanny’s belongings in the East room [include objects] enabled by colonial enterprise.” The East room is compared to the British Museum and Fanny to a curator.

Well, any room in a prosperous gentleman’s house is going to include material objects which are the products of imperialism, as well as chinoiserie of all kinds. I'd expect you'd find more of these objects in any room in the house other than the old school-room, though. East is East and West is West

But surely, the “East” in “East room,” is significant? One scholar opines that Fanny’s room is “appropriately called the East Room” because it conjures “a growing global awareness.” It draws our thoughts toward the East, where the East India Company clippers plied the waves between Canton and Madras and Calcutta before returning to the docks of London.

Well, I think we can find a more prosaic reason for the name of the room. I can assure you that the East room is called the East room because it faces east. Why am I so certain? Because it was the school-room.

Once the gentry stopped living in stone castles and stopped worrying about how to fend off marauders, they were living in mansions and were able to think about which way the windows faced, or the “aspect,” in their home designs.

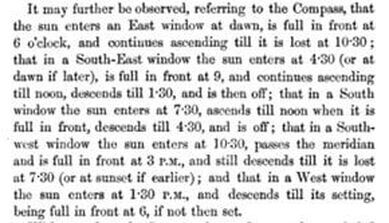

The Gentleman’s House, published in Victorian times, pays a lot of attention to “aspect.” In describing school-rooms, the author advises: “The light ought to be abundant, for various educational reasons.” A description of an Irish mansion specifies that the “Gentleman’s room” —that is, the room men used for business, going over their books, meeting with their bailiff and steward— “is lighted from the North and East.” We recall that soon after Lady Catherine de Burgh enters the Bennet’s parlour, she announces: “This must be a most inconvenient sitting-room for the evening in summer: the windows are full west.”

The “aspect” of the East Room is so favourable that it stays tolerably warm without a fire, thanks to passive solar heating. It might even be a corner room with windows running along two of its four walls, facing south-east or north-east.

I have spent some time in classrooms in China. The architect of the school where I taught designed the building to take advantage of natural light. The school was built around an open courtyard, not for aesthetic reasons, but so the corridors had windows, letting in natural light. The outer walls of the classrooms had windows and clerestory windows ran along the tops of the interior walls. No artificial light needed.

I have spent some time in classrooms in China. The architect of the school where I taught designed the building to take advantage of natural light. The school was built around an open courtyard, not for aesthetic reasons, but so the corridors had windows, letting in natural light. The outer walls of the classrooms had windows and clerestory windows ran along the tops of the interior walls. No artificial light needed. incidentally, just as Fanny did not have a fire, the college radiators never made it past a feeble lukewarm in the winter. If you put your hands directly on them, you might sense some warmth. The students and I wore our coats, and sometimes gloves, in class. More about my time in China if you click the subject "China" at upper right.

excerpt from The Gentleman's House, a Victorian guide to home design.

excerpt from The Gentleman's House, a Victorian guide to home design.

The East room doesn't look too shabby in this Brock illustration. What happens in the East room, stays in the East room

The East room doesn't look too shabby in this Brock illustration. What happens in the East room, stays in the East roomWe know that Fanny uses the East room for her private sitting-room because her own bedroom is too small. But look at the East room from the point of view of a writer. Consider for a moment the needs of the plot. What happens in the East room? It hosts a number of private—and important—conversations between Fanny and Edmund, Fanny and Mary Crawford, and Fanny and Sir Thomas. And it also hosts a rehearsal of a love-scene between Mary and Edmund, with Fanny as unwilling looker-on, one of the many scenes in which Austen sets up our heroine so we can watch her being tortured.

Could any of these scenes take place anywhere else? Outside, possibly, in the shrubbery, if the weather was warm enough and it wasn't raining. Fanny does have several important conversations outdoors, away from the servants and everyone else. Can Fanny entertain Edmund in her poky little bedroom? No, because although they grew up like brother and sister, she is going to marry him later. It’s not proper. Could she have had these conversations down in the sitting room? No, in any of the downstairs rooms, the conversations might be overheard or broken in upon. Once, Fanny places a conversation between (the adult) Edmund and Fanny on the staircase going up to the second floor, “and the appearance of a housemaid prevented any farther conversation.” That conversation is deliberately broken off by Austen.

Mary specifically seeks out Fanny in the East room to go through her part in the play before the evening rehearsal with Edmund, in front of all the others. Later in the novel, Fanny stays in the breakfast room, hoping to avoid a conversation with Mary before she leaves Mansfield, but "Miss Crawford was not the slave of opportunity." She steers Fanny up to the East room.

Without the East room, Fanny would have to run out to the shrubbery every time she needed to have a private word with someone. Or Edmund would need to give her the gift of a necklace on the stairway or, heaven forbid, in the sitting-room in front of Aunt Norris and you know how that would have gone.

Instead, we learn in Chapter 16 that Fanny had, for some time although it hadn’t been mentioned yet, been using the East Room for her private sanctuary. The narrative passage is a bit of backstory, but also takes us into Fanny's inner feelings and thoughts.

That’s why the East Room comes into the novel—it is necessary for plot purposes.

When you ask yourself, why does Austen do such-and-so? or in this case, what's the big deal with the East room? You can start by asking yourself, what would have happened if this wasn't in the novel? And in the case of the East room, it would have meant Fanny had no indoor space where she could have a private conversation or even have a moment to herself. A commentator on the “Reading Jane Austen” podcast remarked: "I experienced the introduction of the East Room in Chapter 16 as a real turning point, because that is where you get the first extended section of Fanny’s internal deliberations. And it comes right after Mrs. Norris’s insult in the chapter before—just when a reader would want to know how Fanny survives in such an environment."

Whether the East room means more—whether it's symbolic of Fanny's solitude, or of her growing independence, or a simulacrum of Empire, colonized by Fanny, I will leave to others. But I think analysis of the East room might start with the basic facts I've mentioned here. Austen's description of the East room:

Mansfield Park, Chapter 16, excerpt:

"The little white attic, which had continued her sleeping-room ever since her first entering the family, proving incompetent to suggest any reply, she had recourse, as soon as she was dressed, to another apartment more spacious and more meet for walking about in and thinking, and of which she had now for some time been almost equally mistress. It had been their school-room; so called till the Miss Bertrams would not allow it to be called so any longer, and inhabited as such to a later period. There Miss Lee had lived, and there they had read and written, and talked and laughed, till within the last three years, when she had quitted them. The room had then become useless, and for some time was quite deserted, except by Fanny, when she visited her plants, or wanted one of the books, which she was still glad to keep there, from the deficiency of space and accommodation in her little chamber above: but gradually, as her value for the comforts of it increased, she had added to her possessions, and spent more of her time there; and having nothing to oppose her, had so naturally and so artlessly worked herself into it, that it was now generally admitted to be hers. The East room, as it had been called ever since Maria Bertram was sixteen, was now considered Fanny’s, almost as decidedly as the white attic: the smallness of the one making the use of the other so evidently reasonable that the Miss Bertrams, with every superiority in their own apartments which their own sense of superiority could demand, were entirely approving it; and Mrs. Norris, having stipulated for there never being a fire in it on Fanny’s account, was tolerably resigned to her having the use of what nobody else wanted, though the terms in which she sometimes spoke of the indulgence seemed to imply that it was the best room in the house.

"The aspect was so favourable that even without a fire it was habitable in many an early spring and late autumn morning to such a willing mind as Fanny’s; and while there was a gleam of sunshine she hoped not to be driven from it entirely, even when winter came. The comfort of it in her hours of leisure was extreme. She could go there after anything unpleasant below, and find immediate consolation in some pursuit, or some train of thought at hand. Her plants, her books—of which she had been a collector from the first hour of her commanding a shilling—her writing-desk, and her works of charity and ingenuity, were all within her reach; or if indisposed for employment, if nothing but musing would do, she could scarcely see an object in that room which had not an interesting remembrance connected with it. Everything was a friend, or bore her thoughts to a friend... Sidebar: Since MIss Lee had "lived" in the East room, this implies that her bedroom was attached to it.

So here's another thought—it ought to have occurred even to Lady Bertram that Fanny could move to Miss Lee’s bedroom, once the former governess was let go. The governess’s bedroom was very often placed next to the school-room. But wherever Miss Lee's bedroom was, it would have been a nicer room than any rooms assigned to the lower servants.

Well-lit, airy class room Or, once Maria is married and Julia is away for an extended period, Fanny could have moved to one of their bedrooms!

Well-lit, airy class room Or, once Maria is married and Julia is away for an extended period, Fanny could have moved to one of their bedrooms!But no, Fanny still uses the little white attic. She gets dressed ("makes her toilet") there, as we know from the description of her preparations for the ball. In that respect, I disagree with the academic who thinks Fanny has turned the East room into her own "dressing room." She does not dress or undress there, and so she can receive gentlemen in the East room. "The room was most dear to her, and she would not have changed its furniture for the handsomest in the house, though what had been originally plain had suffered all the ill-usage of children; and its greatest elegancies and ornaments were a faded footstool of Julia’s work, too ill done for the drawing-room, three transparencies, made in a rage for transparencies, for the three lower panes of one window, where Tintern Abbey held its station between a cave in Italy and a moonlight lake in Cumberland, a collection of family profiles, thought unworthy of being anywhere else, over the mantelpiece, and by their side, and pinned against the wall, a small sketch of a ship sent four years ago from the Mediterranean by William, with H.M.S. Antwerp at the bottom, in letters as tall as the mainmast... and as she looked around her, the claims of her cousins to being obliged were strengthened by the sight of present upon present that she had received from them. The table between the windows was covered with work-boxes and netting-boxes which had been given her at different times, principally by Tom; and she grew bewildered as to the amount of the debt which all these kind remembrances produced."

Previous post: Methodists in the Long 18th Century

In my Mansfield Trilogy, Fanny Price runs away from Mansfield Park instead of nursing her sorrows in the East room. She becomes a governess for a family living near Bristol, and soon meets a young abolitionist. Her bedroom in her new home is nicer than the little white attic, though still modest. Click here for more about my novels.

In my Mansfield Trilogy, Fanny Price runs away from Mansfield Park instead of nursing her sorrows in the East room. She becomes a governess for a family living near Bristol, and soon meets a young abolitionist. Her bedroom in her new home is nicer than the little white attic, though still modest. Click here for more about my novels.

Published on January 30, 2023 16:56

January 23, 2023

CMP#128 Methodists in the Long 18th Century

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#128 Portrayals of Methodists in the long 18th Century, part two (with some additional comments about a now-suggestive word)

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#128 Portrayals of Methodists in the long 18th Century, part two (with some additional comments about a now-suggestive word)

Poor minister using a barrel for a pulpit

In my previous post,

I gave some examples of novels and plays of the long 18th century that depict Methodist ministers as grifters and con artists. According to these writers, Methodism appealed to the simple, the ignorant, and the credulous. Here are some examples of novels which featured poor working people who were attracted to Methodism. (We capitalize "Methodism" and "Methodists" but the early novels often didn't).

Poor minister using a barrel for a pulpit

In my previous post,

I gave some examples of novels and plays of the long 18th century that depict Methodist ministers as grifters and con artists. According to these writers, Methodism appealed to the simple, the ignorant, and the credulous. Here are some examples of novels which featured poor working people who were attracted to Methodism. (We capitalize "Methodism" and "Methodists" but the early novels often didn't).In Secrets Made Public (1808), “a poor shoemaker, of weak intellects, but inoffensive manners” is “seduced to methodism by the eloquence of an itinerant orator.” At the end of the day, by the light of a dim rushlight, the shoemaker pores over William Huntington 's books about predestination and "antinomianism." [Let's not bother with explaining what all that means, but if you want to know... I don't think Huntington was literally a Methodist but, like many other nonconformist ministers, he had no formal education. He became a popular fire-and-brimstone preacher].

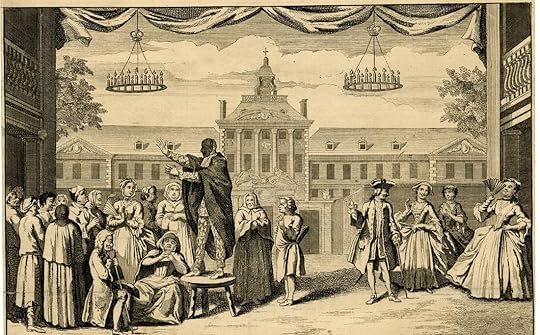

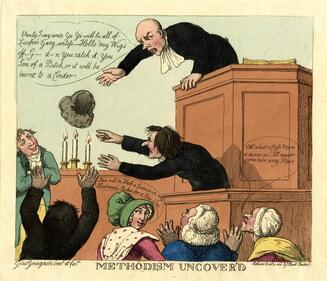

At any rate, some young men, members of the idle rich, decide to play a prank on the cobbler. They dress up as “demons and… various poetical monsters” and one springs into his house one night as the cobbler sits reading his religious tracts. "“He entered the apartment of the cobbling enthusiast, who was devoutly lifting up his eyes and hands, and exclaiming with fervour, ‘We are all d[amne]d!” when the horrible spectre encountered his vision." The cobbler is terrified out of his wits. "With a last exertion of strength, he fell on his knees and ejaculated, or attempted to ejaculate, ‘Lord have mercy on us!’ " (cont'd after break) In the print below, the Methodist preacher is shown wearing the costume of a Harlequin, suggesting that the preacher is just masquerading and is not sincere. The crowd is gathered in front of Bedlam, suggesting insanity. Notice that the people listening to the sermon are mostly poor people in humble garb, while the rich toffs on the right are recoiling in distaste and amusement.

Methodist preacher George Whitefield supported by the personifications of Deceit and Hypocrisy, detail of Enthusiasm display'd: or, the Moor Fields congregation The anonymous author of The Fair Methodist (1794) demanded: “And we may ask to what fell demon of this isle are we indebted for all the cant and hypocrisy, ignorance and deceit, that prevail among a deluded people, called Methodists?”

Methodist preacher George Whitefield supported by the personifications of Deceit and Hypocrisy, detail of Enthusiasm display'd: or, the Moor Fields congregation The anonymous author of The Fair Methodist (1794) demanded: “And we may ask to what fell demon of this isle are we indebted for all the cant and hypocrisy, ignorance and deceit, that prevail among a deluded people, called Methodists?” I haven't read this novel but it is reportedly a bizarre and bitter tract which combines doctrinal arguments with a personal account of a man who was jilted by a girl who converted to Methodism. Scholar Allene Gregory says: “The novel itself deals with a young woman who behaves very treacherously to all her friends, and then becomes a Methodist and assumes airs of great sanctity. There are numerous passages directed against all forms of belief in which faith and an emotional experience (ie, being “saved”) are considered as an equivalent for [doing good] works.”

In G.; Or the Child of Sin (1820), the author shows how Methodism was viewed as a threat to the established church, and the competition posed by Methodist sermons, songs, and modes of worship was an ever-present irritant to a clergyman in the management of his parish. In a passage describing the travails of a country clergyman, we are told: “the poor and the simple were often as hard to be pleased… they were very susceptible of affront, nor spared their threatenings.—“I’ll turn Methodist,” (this was the anti-church note through the parish.) “I’ll turn Methodist,” was no uncommon threat, not only when their sittings were monopolized by the great farmers, but if the singers did not wish the discordant note of some tuneless ear—if the [bell] ringers objected to some awkward handy-man—if the arrangement of a christening or a burial did not agree with individual requirement, still the cry was—“I’ll turn Methodist.”

Novelists sometimes paired their criticism of the perils of Methodism with critiques of the Anglican church–-if the established church would only reform itself, then Methodism could not get a foothold amongst the people. For example, in Coraly (1819), after the heroine’s clergyman father dies, his parish at Ashbury is given to a dissolute younger son of a nobleman who has no vocation for the ministry. The new minister appoints a curate to carry out his religious duties, just as Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park assumes that Edmund Bertram will do the same when he takes the living at Thornton Lacey. (I'm not suggesting Austen took this idea from Coraly, rather, that this was a common critique of the absentee clergy.)

Later, our heroine Coraly comes across one of her old parishioners who has fallen on hard times and he explains the disastrous consequences of such corruption and neglect: “So, miss, soon after our present curate came to reside, the church got deserted; we went, indeed, but we did not return as we used to do, better and happier than we went: and so a fine preacher came every Sunday and preached in our great barn, which is facing the blacksmith’s shop, and here, by degrees, we all went. God forgive us forsaking our right church… but indeed, it was sad, dull, work, to go and only hear a very short sermon all about what we could not understand; while the man at the barn, bless you, anybody could understand him…"

This poor cottager is swindled by the “fine preacher” who borrows sixty pounds from him, “but miss, would you believe me, in three weeks he never came again, and from that day to this I have never heard of my money. I thought my poor wife would have gone mad—and everything went wrong with us. It was a judgement in leaving my own church…”

Elsewhere in the novel, Coraly’s paternal aunt accuses her late brother of having methodistical tendencies. Coraly angrily refutes the charge. “Oh niece,” said Mrs. Mandeville, “you must acknowledge my poor brother was himself very far gone in that way.”

“No, madam," our heroine replies, “in a voice of reproach.” “I never will acknowledge what I know to be otherwise! My dear father was free from every taint of methodism!”

The knock against dad was probably that he was sincerely pious and devoted. The charge of “methodism” or “fanaticism” was an easy way for the cynical to dismiss anyone who upbraided you on religious grounds. In Mansfield Park, after Edmund Bertram tells Mary Crawford he's shocked and disgusted at her blasé attitude toward Maria's adultery with her brother, Mary is nettled and responds with scorn. ‘A pretty good lecture, upon my word. Was it part of your last sermon? At this rate you will soon reform everybody at Mansfield and Thornton Lacey; and when I hear of you next, it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists, or as a missionary into foreign parts.’

Mary looked at Maria and Henry's adultery as "folly," as a social problem to be finessed. Edmund saw it as a sin, a betrayal of family ties, and a breaking of sacred vows. Today, many readers think Mary is in the right here. They argue that she's pragmatic, as well as compassionate, but that's another conversation. This post is about the portrayals of Methodists in novels of the long 18th century. The point is that Mary is scornful of Edmund's severe views about adultery. The Mary vs Edmund confrontation was adapted for modern audiences in the 1999 movie to add the shock of Mary's calm statement that it would be better if Edmund's older brother died, so Edmund could inherit. Therefore, I think Austen's reference to Methodists is not so much a dig at Methodists but a reflection on Mary’s worldly ways. Likewise, in The Little Beggar Girl and her Benefactors (1813), a servant gently urges his master to be charitable to the little beggar girl. Sir Solomon Mushroom refuses his aid on the grounds that the little girl’s mother has brought hardship upon herself. She is a fallen woman and a drunkard who is a blight on the parish. Sir Solomon scoffs at his servant and accuses him of being a Methodist.

“A Methodist, your honour! What is that?” protests the servant.

“One who talks about what he does not understand, as thou dost.”

“Then please your honour, I am no Methodist, I am only a man.”

Clearly, our sympathies are to rest with the beggar girl and the servant, not Sir Solomon.

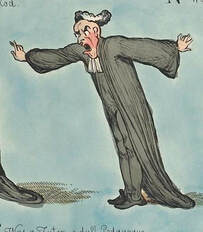

This Methodist minister is preaching in the great outdoors. Some sailors heckle him when he threatens them with hellfire. The preacher exclaims, "Only consider, if you go on in this way--when the day of judgement arrives--even I your pastor--your shepherd, your guide must bear witness against you--." The sailor cheekily answers, "Now that's just the way it goes at the Old Bailey--the greatest rogues always turn King's Evidence!" To conclude, here's a portrayal of poor working-class Methodists which, though condescending, is not negative. In Husband Hunters!!! (1816) by Amelia Beauclerc, we open with a “poor but industrious” Methodist couple, John and Margery Barnes. John and Madge speak in rustic dialect, as comic characters, but they are also shown as being charitable, hard-working, honest, and virtuous.

This Methodist minister is preaching in the great outdoors. Some sailors heckle him when he threatens them with hellfire. The preacher exclaims, "Only consider, if you go on in this way--when the day of judgement arrives--even I your pastor--your shepherd, your guide must bear witness against you--." The sailor cheekily answers, "Now that's just the way it goes at the Old Bailey--the greatest rogues always turn King's Evidence!" To conclude, here's a portrayal of poor working-class Methodists which, though condescending, is not negative. In Husband Hunters!!! (1816) by Amelia Beauclerc, we open with a “poor but industrious” Methodist couple, John and Margery Barnes. John and Madge speak in rustic dialect, as comic characters, but they are also shown as being charitable, hard-working, honest, and virtuous.We are told Margery “had been bred up piously, but was as superstitious as pious.” One stormy night, they hear a horseman ride up to, then retreat from, their isolated cottage in the woods. Madge is afraid to go downstairs. The more level-headed John insists that they investigate, and they discover a foundling baby girl in a basket on their doorstep.

“Madge had been at a Sunday school, and could have deciphered a letter, had there been one in the basket,” but this particular foundling has been left with a supply of money but no note.

"Sunday school" refers to free schools set up not only by Methodists but charitable members of the upper classes to educate poor working-class children and adults. Sunday afternoon was of course the only time they had some daylight hours to spare out of their week to learn to read some Bible verses.

The foundling, by the way, is the legitimate infant daughter of Emily and Henry Beaumont, who married privately and secretly to avoid the wrath of his father, Lord Harbingdon. I'm sure everything will work out in the end.

Brenda S. Cox's book, Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen's England, has a lot more about the Methodists and evangelicals who challenged the established church, and Jane Austen's reaction to the religious debates of her day. Previous post: Grifting Methodist preachers Bonus discussion:

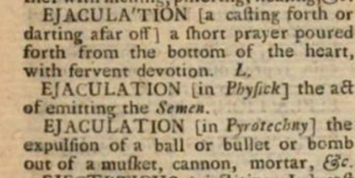

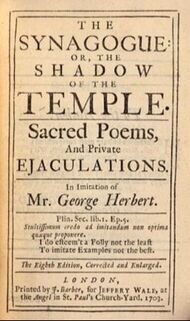

Note: A 1737 dictionary lists the different meanings of the word "ejaculate."

Note: A 1737 dictionary lists the different meanings of the word "ejaculate."I checked a few editions of Dr. Johnson's dictionary and he omits the definition relating particularly to male emissions. Some academics like to suggest that any use of certain words must imply an allusion to sex--words such as "come," and "tumble," and "chimney-sweep," but I think, at bottom, they are reading an unintended double-entendre into the text.

It means fervent prayer, people! Here's a 1902 compendium of "anti-Methodist" literature of the eighteenth century which calls the novel, The Fair Methodist, "a disgraceful, corrupt, and libidinous piece of writing." Even the "libidinous" part does not make me inclined to read it.

It means fervent prayer, people! Here's a 1902 compendium of "anti-Methodist" literature of the eighteenth century which calls the novel, The Fair Methodist, "a disgraceful, corrupt, and libidinous piece of writing." Even the "libidinous" part does not make me inclined to read it.Gregory, Allene. The French Revolution and the English Novel. United Kingdom, G. P. Putnam's sons, 1915.

Published on January 23, 2023 00:00