Lona Manning's Blog, page 14

July 1, 2022

CMP#114 Ann Ryley: Runaway, Wife, Actress

This post concludes my series on Ann Ryley (1760-1823), forgotten Regency novelist. For the first in the series,

click here.

For the first post in "Clutching My Pearls," a blog about Jane Austen and her times,

click here.

This post concludes my series on Ann Ryley (1760-1823), forgotten Regency novelist. For the first in the series,

click here.

For the first post in "Clutching My Pearls," a blog about Jane Austen and her times,

click here.

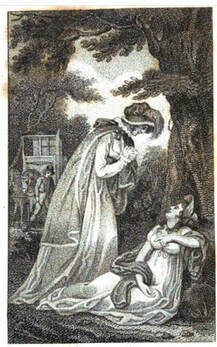

Bartolozzi after Morland, "The Elopement" CMP#114 Ann Ryley: Comedy and Tragedy

Bartolozzi after Morland, "The Elopement" CMP#114 Ann Ryley: Comedy and TragedyI've been examining the outspoken political opinions of the forgotten novelist Ann Ryley for a full week and I haven't really gotten into her portrayals of snobby aristocrats! I will return to that later as part of a more general discussion of the portrayal of the nobility in novels of this era. For now, I'll finish off my tribute to Ann Ryley with a look at her life.

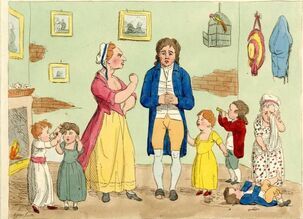

As I mentioned in the last post, Ann tread the boards with her husband, who was an actor, comedian, and sometime theatre-manager. One of the plays in the Ryleys' repertoire is The Clandestine Wedding (1766), a comedy about young lovers who marry secretly. (Jane Austen saw this play performed at Covent Garden, but she did not see the Ryleys because they never made it out of the provinces to the big time.)

In this comedy, Ryley's husband played a rickety old nobleman who mistakenly thinks Ann's character has fallen for him. This is especially awkward for Ann's character (Fanny) because she's already secretly married to her father's clerk. Fanny’s sister, meanwhile, is looking forward to a mercenary marriage, exchanging her father’s wealth for a noble title. “Love in a cottage!” she sneers to Fanny. “Ah, give me indifference and a coach and six!”

Ann Ryley knew all about love in a cottage... She and her husband eloped when she was just 16 years old. Her father was a woolen cloth manufacturer, and Samuel Ryley was his apprentice, but Sam couldn't care less about wool--he was, according to someone who knew him then, the life and soul of the party who loved hunting and carousing. As Sam Ryley's memoir recounts: “Behold me now, in my twentieth year, up to the heart in love, and very ignorant of the business I was bound to learn, added to which my irregularity and dissipation were become proverbial; Miss K[enworthy] was cautioned to keep me at a distance but that was impossible… I pressed my suit, and in my twentieth year prevailed on Miss K[enworthy], aged sixteen, to accompany me to Gretna Green, attended by a female friend…”

Ann was not disinherited for running off with the happy-go-lucky Sam, but her parents would have done well to withhold some or all of her settlement until she was older. The newlyweds spent their entire inheritance in a few years, living the high life, and ended up penniless, rather like Mrs. Smith and her husband in Persuasion. Unlike Mrs. Smith, there was no convenient West Indian property for them to recover. In financial desperation, Sam Ryley launched his acting career, overcoming the genteel reservations of Ann, who recognized that going on the stage was a "degradation." Ann was drawn more and more into the concerns of the play-acting company, copying the scripts and so forth, and she became an actress herself. In the 1780's, the couple lived in Manchester, a rapidly-growing city soon to be on the forefront of the Industrial Revolution.

Disguising a suitor as an old woman in "Who's the Dupe" Ann Ryley usually played saucy sidekicks and comic parts, such as Charlotte, who sorts out the romantic troubles of Elizabeth in Who's the Dupe (1779). Her husband played Elizabeth's father, who insists that she marry a learned scholar. The young hero tells his friend: “I am not one of those sighing milksops, who could live in a cottage on love, or sit contentedly under a hedge and help my wife to knit stockings; but... I had rather marry Elizabeth Doiley with twenty thousand pounds, than any other woman on earth with a hundred thousand.”

Disguising a suitor as an old woman in "Who's the Dupe" Ann Ryley usually played saucy sidekicks and comic parts, such as Charlotte, who sorts out the romantic troubles of Elizabeth in Who's the Dupe (1779). Her husband played Elizabeth's father, who insists that she marry a learned scholar. The young hero tells his friend: “I am not one of those sighing milksops, who could live in a cottage on love, or sit contentedly under a hedge and help my wife to knit stockings; but... I had rather marry Elizabeth Doiley with twenty thousand pounds, than any other woman on earth with a hundred thousand.”In Which is the Man (1782), Ann Ryley played Sophy Pendragon, a naïve village girl from Cornwall who follows Lord Sparkle, a Henry Crawford type, to London. She['s deluded into thinking he loves her because he quotes the most romantic passages of novels to her. Because the play is a comedy, nothing bad happens to Sophy, she just goes back home to Cornwall.

In a comedy called The Agreeable Surprise (1784), Sam Ryley played Lingo, a butler who likes to spout Latin and make classical allusions. Ann played Cowslip, a dairymaid. Some of the comedy arises out of Lingo's dialogue with Cowslip when she misunderstands what he is saying. I might as well inflict some Latin grammar jokes (who doesn't like a Latin grammar joke?) and some terrible puns on you:

Lingo: Ay, ay, all my Latin is Greek to these people... Not a soul in the house will listen to me but Cowslip the dairy maid… (Enter Cowslip, with a bowl of cream.) My sweet Cowslip, properly called Cowslip, Nominitivo, hanc hunc et hoc.

Lingo: Ay, ay, all my Latin is Greek to these people... Not a soul in the house will listen to me but Cowslip the dairy maid… (Enter Cowslip, with a bowl of cream.) My sweet Cowslip, properly called Cowslip, Nominitivo, hanc hunc et hoc.Cowslip: I have put the hock into the syllabub, Mr. Lingo, and here it is!

Lingo: …Cowslip sit down, you’re a noun adjective and must not stand by yourself. Let’s have a toast.

Cowslip: I’ll go bake one, Sir.

Lingo: No, I’ll make one. Here’s that the masculine may never be neuter to the feminine gender.... Jupiter was a fine god. He swam on a bull to Europe. He went into a flash of fire for Semele.

Cowslip: Yes, sir, he’d go any lengths for his ale.

Lingo: I mean, his amours.

Cowslip: O ay; he’d drink with Moors or Turks either.

Lingo Drink! Who?

Cowslip: Who! Why, Jew Peter, the old clothes-man. (Groan)

Reading personality types from faces The Deserted Daughter (1788), by Thomas Holcroft, blends melodrama with comedy. A widower hides the fact of his first marriage from his upper-class second wife. He neglects his daughter, who people think is his natural daughter but she is really legitimate. This daughter, Joanna, is taken to a brothel to be sold off. A strange gimmick of this play is that Joanna is a student of the physiognomist Lavater. Joanna can read people's faces to discern their personalities. She figures out that everybody is lying to her. She escapes from the brothel in men's clothes (titillating!) plus there is an incest tease. This, I think, would be another play that Fanny Price would think unfit for home representation. I previously discussed this play when writing about the

"bear and forbear"

type of heroine. My guess is that Ann Ryley played the comic part of the maid who sympathizes with her long-suffering mistress, rather than the lead part of Joanna.

Reading personality types from faces The Deserted Daughter (1788), by Thomas Holcroft, blends melodrama with comedy. A widower hides the fact of his first marriage from his upper-class second wife. He neglects his daughter, who people think is his natural daughter but she is really legitimate. This daughter, Joanna, is taken to a brothel to be sold off. A strange gimmick of this play is that Joanna is a student of the physiognomist Lavater. Joanna can read people's faces to discern their personalities. She figures out that everybody is lying to her. She escapes from the brothel in men's clothes (titillating!) plus there is an incest tease. This, I think, would be another play that Fanny Price would think unfit for home representation. I previously discussed this play when writing about the

"bear and forbear"

type of heroine. My guess is that Ann Ryley played the comic part of the maid who sympathizes with her long-suffering mistress, rather than the lead part of Joanna.Although the plays of the day offered plenty of comic parts for older ladies, It appears that Ann Ryley retired from the stage before her husband did. Love in a cottage

Sam Ryley tried and failed with various business ventures, including being a wine merchant and managing a theatre. Charles Dibdin, the composer and playwright, described Ryley as being "peculiarly unfortunate in his theatrical pursuits." Only once did Ryley have an opportunity to perform upon the London stage, at the Drury Lane theatre--but the theatre burnt down and so he lost the engagement. After so many setbacks, Ryley's youthful exuberance gave way to misery and pessimism, so much so that his fellow-comedian, Charles Mathews, based an Eeyore-like comic character, Mundungus Triste, on Ryley.

It appears that through all their ups and downs, the Ryleys remained very much in love. Ryley described his wife as having a “natural cheerfulness, and flow of animal spirits, [and] seldom suffer’d depression, even under misfortunes that drove me to despair.” Ryley's love for his wife shines through the clichés in his memoir: “Oh, happy state! Avaunt, ye scoffers! This blessed bond of union between the sexes, brings with it a solace for sorrow… whilst the fair hand of Affection wipes away the tear of Sensibility…”

After some time in Manchester and on the Isle of Man, the Ryleys moved to “a little white cottage overlooking the sea in Parkgate near Liverpool.” Mr. Ryley went out on the road, while Ann stayed home and worked on Fanny Fitz-York. One final humiliation lay in store for them, however.

Theatrical Disaster

Theatrical DisasterAbout the same time that his wife published her novel, Sam Ryley offered a comic play he had written to the Drury Lane theatre, and it was accepted. Eagerly, he hurried down to London to watch the rehearsals. The play, registered with the censors as Castles in the Air, concerned a cast of eccentric characters and a tumble-down Welsh castle. A deluded man thinks he is Welsh royalty and he treats everyone around him as a vassal. Miss Helicon, a female pedant, advertises for a secretary at the same time as her room-mate, a widow, advertises for a husband. A comic mix-up ensues: "Do you think yourself competent to the task?" Miss Helicon asks a fortune-hunting Irish soldier, who thinks she's looking for a husband. He replies, "Competent! Don't afflict yourself about that, Honey!"

The first-read through with the actors did not go well. Ryley recalled: “I soon found that what may appear very well in the closet, bears a very different aspect, when read before critics, some of whom are not disposed to be favourable.” (Here, "closet" means, one's private bedchamber or changing room.)

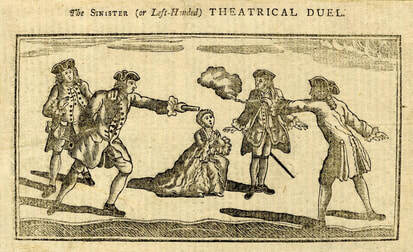

Ryley was, of course, in attendance when the play, retitled the Castle of Glendower, made its debut on March 2, 1818--and was an unqualified disaster. As Ryley recounts: “a benumbing silence attended the representation, which at length burst forth in a hiss so tremendous… it will never be out of my recollection; and after that, although the play proceeded, not one line was heard. During the third act, the disapprobation became pretty general; though for what, no one could tell, for the language was inaudible, and the performers, to do them justice, bore the brunt of the storm without flinching from their duty.”

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Mary, and their friends, the journalist Leigh Hunt and his wife. were in the audience for the theatrical catastrophe. Mary's journal merely notes: "Go to the play in the evening — b[ox] with Hunt & Marianne — a new comedy damned."

The reviews were scathing. The Theatrical Inquisitor: “We never witnessed so complete and so deserved a condemnation… We cannot conceive how any one who ever before saw or read a play, could have imagined that it would succeed…”

Sam Ryley's dreams of financial security evaporated again, with public humiliation heaped on top. His friends held a benefit to raise some money so he could afford to go home to Liverpool.

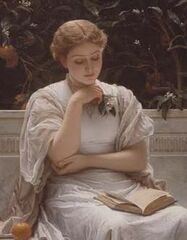

In his memoirs, Ryley describes a scene of homecoming after he had been three months on the road: “seated at her cottage door, intent upon a book, sat my friend of forty years—the stimulant to all my labours, the ample reward of all my toils. She saw me not. Standing at the wicket, my mind whispered, ‘Oh Fortune! – if thou wouldst but even gently smile upon our latter days! --her eye caught mine—the book fell on the grass—and—conceive the rest, ye who can—smile, ye who may."

Sam Ryley was away from home, touring Scotland, when Ann died suddenly in March 1823. Her epitaph in Neston churchyard read: "Beneath this stone the Remains of Nanny Ryley, formerly of Parkgate, aged 63, are deposited, and with them every hope of happiness that this world can bestow on her disconsolate husband, in whose breast a warm and enthusiastic affection, of seven and forty years’ standing, remains unabated; which time can never obliterate, nor ought but death destroy."

Sam Ryley was clearly proud of his wife and boasts of her intelligence in his memoirs. He married again, but I think it was simply because his second wife, Ann Ryley's niece, needed a home, and he needed a nurse for his old age.

I have found no portrait of Ann Ryley. Sam Ryley cherished a miniature portrait of her, but perhaps it was buried with him when he died in 1837. The Ryleys had no children.

From the play, The Castle of Glyndower, aka, Castles in the Air: The main character meets another man in debtor's prison and learns he has lost his wife: "Had he? Had he? So had I a wife, an amiable wife! (to his daughter) Thy dear mother. Poverty! Imprisonment! Trifles light as air. But the loss of a wife, an amiable wife..." Sam Ryley's memoir, The Itinerant, is a blend of fiction and fact, so it is not always possible to know which anecdotes of his life on the road with Ann are true. Dibdin, Thomas. The Reminiscences of Thomas Dibdin: Of the Theatres Royal, Covent Garden, Drury Lane, Haymarket, &c. and Author of The Cabinet, &c. Henry Colburn, 1837.

From the play, The Castle of Glyndower, aka, Castles in the Air: The main character meets another man in debtor's prison and learns he has lost his wife: "Had he? Had he? So had I a wife, an amiable wife! (to his daughter) Thy dear mother. Poverty! Imprisonment! Trifles light as air. But the loss of a wife, an amiable wife..." Sam Ryley's memoir, The Itinerant, is a blend of fiction and fact, so it is not always possible to know which anecdotes of his life on the road with Ann are true. Dibdin, Thomas. The Reminiscences of Thomas Dibdin: Of the Theatres Royal, Covent Garden, Drury Lane, Haymarket, &c. and Author of The Cabinet, &c. Henry Colburn, 1837.Procter, Richard Wright. Literary Reminiscences and Gleanings. T. Dinham, 1860.

Procter, Richard Wright. Manchester in Holiday Dress. Simpkin, Marshall & Company, 1866.

Ryley, Samuel William. The Itinerant; Or, Memoirs of an Actor. Taylor and Hessey, 1817.

Castles in the Air: Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Eighteenth Century Drama, http://www.eighteenthcenturydrama.amd... [Accessed May 25, 2022]. The manuscript of the play is written in at least three different hands and some scenes are crossed out.

Published on July 01, 2022 00:00

June 30, 2022

CMP#113 Treading the Boards with Ann Ryley

Fanny took "up the volume which had been left on the table, and begin to acquaint herself with the play of which she had heard so much... she ran through it with an eagerness which was suspended only by intervals of astonishment... that it could be proposed and accepted in a private theatre! Agatha and Amelia appeared to her in their different ways so totally improper for home representation—the situation of one, and the language of the other, so unfit to be expressed by any woman of modesty, that she could hardly suppose her cousins [Maria and Julia] could be aware of what they were engaging in... -- Fanny Price reading Lover's Vows in Mansfield Park CMP#113 Fanny Fitz-York, part 5: Unexceptionable as to morals

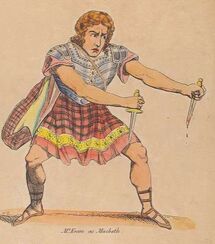

Edmund Kean as Macbeth In previous posts, I've looked at the forgotten novel Fanny Fitz York (1818) in terms of its plot, its female characters. and the moral and political opinions the characters express. In this post, we're going to the theatre and dealing with some other bits and pieces.

Edmund Kean as Macbeth In previous posts, I've looked at the forgotten novel Fanny Fitz York (1818) in terms of its plot, its female characters. and the moral and political opinions the characters express. In this post, we're going to the theatre and dealing with some other bits and pieces.Lady Ann, the mother of the heroine, carefully safeguards her daughter's morals. When they are invited to take in a play, Lady Ann asks if the actors are any good, then asks: "And the piece-- is it a moral one?” When she is assured it is “Unexceptionable,” she decides to take a box. “The young folks no doubt will be highly gratified, and if, as you say, the play is unexceptionable, improved. The drama, under proper restrictions, would not merely be an innocent amusement, but a very high source of edification…”

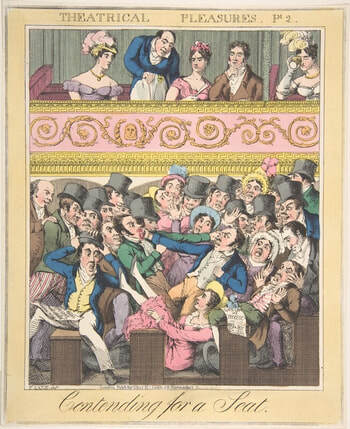

It's not surprising that Anne Ryley has opinions about the theatre. Her husband, S.W. Ryley, was an itinerant actor and comedian, and she herself trod the boards as a young wife. No doubt the scenes described in Fanny Fitz-York are based on Ann Ryley's real experiences playing in front of rowdy Georgian audiences.

On this first trip to the theatre, young Fanny is enthralled by everything. She pays “close attention to the performance,” which draws the sarcastic attention of other theatre-goers, because “any attention to Shakespeare, or those whose acting is his brightest illustration, is an offence so barbarous, vulgar, and unfashionable, that it is universally rated a bore…”

Fanny and her friends go to the theatre and the opera frequently in Fanny Fitz-York, and some little incident always occurs. Author Ann Ryley has thoughts about noisy, inattentive theatre patrons...

Hijinks at the theatre

Hijinks at the theatreIn an early scene the vulgar young lieutenant Matty Gaskell is hissed and hooted out of the theatre for being drunk, loud, and obnoxious.

In another foray to the theatre, Matty's vulgar sisters are sharing a box together when some strange men burst in on them and start molesting them. The rest of the audience stands up on behalf of the girls: “the pit had warmly taken up the female cause, and insisted so strenuously upon the offending party being turned, that their companions, more reasonable, because less inebriated, forced them from the box, and once more restored the house to order.”

Mrs. Bloomfield, an opinionated dowager we met in previous posts , turns this into a teachable moment for the Gaskell girls, (though today this would be called “slut shaming”). “When females forget the delicacy of their sex, and appear in public almost in a state of nudity, they cannot wonder that men should forget it also, and treat them with the disrespect appearances too well justify…” she goes on to say that anybody might mistakenly assume “the profession” of girls dressed in such scanty clothing.

On another occasion, Mrs. Bloomfield sarcastically tells a raucous group in another box that if the rest of the audience had known in advance that by coming to the theatre they would disturb a private party they would all have stayed home, “but as this information was withheld, I move, that you leave the place and no longer interrupt the amusement of rational creatures.” The rest of the audience applauds.

There is also this exchange between Lady Anne and her friend Mr. Strictland, where she opines that actors and actresses who play heroic and virtuous characters on the stage, ought to be influenced for the better as a result: “I fear many of the sons and daughters of the stage, exhibit a beautiful theory of virtue, without reducing it to practice.”

“My dear Lady Ann,” [her friend responds] “do you expect players to be better than other people?”

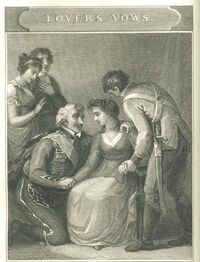

The Baron kneels to Agatha as Amelia, Anhalt, and Frederick look on in Lover's Vows. Austen opines on an improper play

The Baron kneels to Agatha as Amelia, Anhalt, and Frederick look on in Lover's Vows. Austen opines on an improper playThis week I've been comparing Ann Ryley's unvarnished views as a counterpoint to the widely-held belief that Jane Austen had to share her beliefs "warily and subtly," because of social and political repression. Fanny Fitz-York came out the same time as Northanger Abbey/Persuasion and I've been comparing author Anne Ryley's outspoken views with Jane Austen's avoidance of political controversy.

It occurs to me that I can point to one tiny thing that Jane Austen actually opined about, and I quoted the relevant passage at the top of this post. In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price thinks that the play Lover’s Vows is unfit for home representation, and we can presume that Jane Austen thought so as well. The “situation” of Agatha, an unwed mother, and the “language” of Amelia, a forward flirt, in a play well known to Austens first readers, made the play unsuitable for chaste young ladies to portray in private theatricals.

Critics in the increasingly genteel Regency age--leaving behind the rowdy, bawdy Georgian age and looking forward to the Victorian age--considered the play Lover's Vows to be improper. One critic complained of the “radical defects and absurdities of the piece” and opined, “the Play of Lovers’ Vows, drawn from the polluted sources of the German School, however it may occasionally strike upon our feelings, has no moral influence upon the heart, and leaves no permanent impression behind it. That it should have maintained a place among our acting plays, is a serious impeachment of the taste and judgment of the public..."

Whether or not Austen saw Lover's Vows performed, she was aware of the criticisms against it, and the first readers of Mansfield Park would have known of the controversy around the play as well. See Claudia Johnson for a discussion of this play and its significance in Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel. United Kingdom, University of Chicago Press, 1990.

And-- oh yeah, some spoilers--the end of the novel

And-- oh yeah, some spoilers--the end of the novelIf you've been reading along this week, you'll know that Fanny Fitz-York has a lot going on in its pages and has a large cast of characters. I gave an outline of the beginning of the novel here. If anyone would like to know the conclusion of the novel, here it is.

I mentioned the mystery of the missing natural son of Fanny's late uncle Frederick. This son does show up, Out of financial desperation brought on by bad luck, he turns highwayman, and through an amazing coincidence, robs a noble relation of Lady Anne, then he robs a carriage containing his own mother (whom he does not recognize), and and is rescued from an angry mob when Lady Anne also rolls by in her carriage. (Our older novels depend upon death, coincidence, and misunderstanding for their plots, and much of the misunderstanding has to do with the inability to communicate with people in the days before mobile phones and the internet.) Anyway, Lady Anne refuses to turn the highwayman over to the law, preferring to urge him to repent. She discovers he is her nephew and she helps him regain a respectable footing in society (though of course much lower on the social scale, given his illegitimacy). She sets him up as a small-town merchant.

The highwayman's mother makes for an exciting villainess. She had abandoned her son as a child when she went abroad. Returning to England, she learns of the death of Frederick, and she hires an imposter son to try and shake down the rich and noble family for some support money. There are some lively court-room scenes where we have the Big Reveal when her true son shows up and announces himself (Not a big surprise, but still fun).

Rosette's sister Julia, whose fall from virtue is forgiven by her brother the curate, marries the man who seduced her but he is a horrible villain and his shenanigans add interest to the final volume.

Mrs. Bloomfield the outspoken widow carries on being Mrs. Bloomfield. Lord Moseley, who fell in love with Fanny in volume one, finds happiness elsewhere. A random rich uncle shows up from the West Indies to bestow his inheritance on Fanny, and promptly dies. Lady Anne, Fanny's mother, receives a marriage proposal but turns it down, preferring to maintain her widowed state. One of Fanny's early suitors, the amiable Henry Tudor, dies of consumption. I guess he served as a love-interest decoy in volume one, and wasn't needed after that. Both Fanny and her friend/governess Rosette make happy marriages--Rosette to a baronet, Fanny to a titled and wealthy young lord whose parents really like her, unlike her snobby relatives.

More on Ann Ryley's life and theatrical career in the final post in this series.

Published on June 30, 2022 00:00

June 29, 2022

CMP#112 Outspoken A__ R___y

If you want superb writing and amazing delineations of character, you can't top Jane Austen. If you want a female author of the Regency period who discusses slavery, the status of women, race and class, there are plenty of writers who were more explicit on these issues. Trying to re-imagine Austen into being someone she's not makes no sense to me. CMP#112 Fanny Fitz-York, part 4: Who's Outspoken? A____ R_____y, That's Who It used to be the conventional wisdom that Jane Austen didn't express political opinions in her novels—that if you read Austen, you'd barely notice there was a war going on. Now, modern scholars argue that she does express political opinions, but they are oblique and subversive.

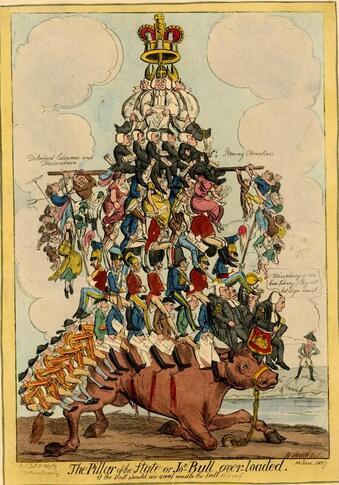

If you want superb writing and amazing delineations of character, you can't top Jane Austen. If you want a female author of the Regency period who discusses slavery, the status of women, race and class, there are plenty of writers who were more explicit on these issues. Trying to re-imagine Austen into being someone she's not makes no sense to me. CMP#112 Fanny Fitz-York, part 4: Who's Outspoken? A____ R_____y, That's Who It used to be the conventional wisdom that Jane Austen didn't express political opinions in her novels—that if you read Austen, you'd barely notice there was a war going on. Now, modern scholars argue that she does express political opinions, but they are oblique and subversive.Austen had to be covert, they explain, because opinions were dangerous in general and opinions from women were not acceptable. In Austen's time, you could get sent to prison for writing or publishing anything deemed too critical of the King or the government, as I've mentioned before. Some scholars have pointed to this fact when suggesting that Austen's novels contained veiled allusions to the events of her day—veiled, that is, because she had to protect herself from reprisals. Let’s talk about being courageous. Let's talk about not writing obliquely. Fanny Fitz-York, as I mentioned , was published in the same month as Northanger Abbey. Its author, Ann Ryley (1760-1823), didn't pull any punches. Ryley, like Jane Austen, detested the Prince Regent and supported his estranged wife Princess Caroline. Unlike Austen, Ryley didn't confine her thoughts to her private life and correspondence. Ryley also swings hard against the prime minister and his cabinet, some Royal Dukes, the war against Napoleon and government in general. Let's see some examples:

Mudslinging on both sides Just as people took sides between Prince Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales, public opinion was divided between the Prince Regent and his estranged wife Caroline.

Mudslinging on both sides Just as people took sides between Prince Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales, public opinion was divided between the Prince Regent and his estranged wife Caroline.The unhappy Royal marriage became a politicized issue. At the time of Ryley's novel, the princess had survived an official enquiry (called the "delicate investigation") into a rumour that she had had an illegitimate son (this at a time when King George’s four sons had dozens of illegitimate children). Ryley puts her opinions in the mouth of her character Mrs. Bloomfield, whom we met in the previous post.

Mrs. Bloomfield declares “There is, at this moment, but one topic of conversation from Hyde Park-corner to Tower-wharf... I tell you [the princess] has everything to dread from a cabal headed by __________ but I won’t call names, though my tongue can scarcely be kept within bounds.” (In keeping with the conventions of the day, when Mrs. Bloomfield mentions a politician or a Royal personage, the name is blanked out. This provided a legal fig leaf against being sued for libel.)

“The investigation has certainly acquitted the [Princess] of criminality,” said Lady Ann [the heroine's mother]; “but imprudence must attach to her.”

“Define what imprudence is, my dear lady,” replied the Widow, “before you attack her with it.”

“A want of decorum, —the improper admission of male visitors—"

“This is imprudence in England, but it bears another interpretation on the continent. A want of decorum here is the height of decorum in other countries; and, it would be cruel indeed, situation as she is, to limit the number or sex of her visitors. Listen, my dear Madam, to a short history….”

Then Mrs. Bloomfield gives a lengthy recap of Caroline of Brunswick’s history and the cruel way she was treated by the Prince Regent, concluding with “Every virtuous heart burns with indignation at her wrongs, and curses the foul faction that oppress injured and exalted worth.”

This lengthy editorial has nothing to do with the plot of the story. Ryley chose to announce her allegiance to #TeamCaroline, which pits her against the supporters of the Regent. But wait, there's more!

“After discussing many fashionable topics [at Fanny’s birthday party], Mrs. Bloomfield descanted upon what she pleased to call the faults of the Regent. No one choosing, however, to controvert, or second her, we suppose the company thought the time or place ill suited for such discussion. But the widow consulted neither, when the foibles or follies of the great appeared to deserve reprehension; in such case no delicacy appalled her--no punctilio restrained the license of her speech—she dashed through thick and thin, and the more elevated her object, the more spirited were her philippics.”

Unlucky in love: Catherine Tylney Long Ripped from the Headlines

Unlucky in love: Catherine Tylney Long Ripped from the HeadlinesMrs. Bloomfield also drops a chatty mention of an “unaccountable [political] transaction” into her correspondence with Lady Anne: "How do the Devon politicians relish the re-appointment of a R___l D___e to the situation his enlightened countrymen thought him unworthy to occupy? … what then are we to think of an appointment which runs counter to the wishes of the people; an appointment neither sanctioned by judgment or policy, but that it betrays weakness or depravity; and, in either case, reduces the rising sun to a mere rush-light.”

For R___l D___e, read “Royal Duke.” I believe Mrs. Bloomfield is referencing Prince Frederick, Duke of York, the second son of King George III, who had recently been re-appointed to his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Army. I think the “rising sun” must be a reference to the Regent. Mrs. Bloomfield is suggesting that if younger brother Frederick is at the head of the army during a time of global conflict against Napoleon, he will outshine the Regent, who is busy overseeing the decorations of his pavilion at Brighton or something.

Ryley throws some shade at another Royal Prince when Lord Moseley escorts the ladies to the Opera. During the interval, “Lord Moseley entertained his young friends by pointing out different characters of celebrity in the fashionable and political world. Amongst the former, he drew their attention to the wealthy Miss T___y L____g, who preferring love and a commoner to ambition and a R_____l D____e, had set her sex an example worthy of imitation.”

“And has your Lordship,” asked Lady Ann, “so poor an opinion of the sex as to suppose this a rare instance of humility? For my own part, I cannot see the excessive merit in such a refusal; the wonder to me would have been that any female in her situation could have acted otherwise. Youth, health, splendour, and the man of her choice, when contrasted with the comparative age, dissipation, debt, and indifference—and to add the greatest objection of all, the father of ten [illegitimate] children… I say, when the two characters are considered, the female must not only want delicacy, but be absolutely depraved, to barter the affections of her heart even for the high sounding title of a R____l Duchess.”

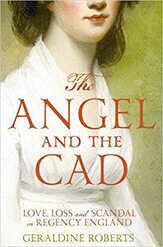

The characters are speaking of the real-life heiress Catherine Tylney Long, who turned down a proposal of marriage from Prince William, the third son of George III, who was deeply in debt and already had a mistress and a family. Sadly, Miss Tylney Long's chosen husband turned out to be a wastrel and a profligate and their marriage was miserable. If she had married William, she would have become Queen Catherine, because William briefly held the throne after his older brother died.

In any case, Ryley's support of Princess Caroline and Catherine Tylney Long appears to reflect the maxim that "the enemy of my enemy is my friend."

Some saw Sir Francis Burdett as a threat Political Boys' Club

Some saw Sir Francis Burdett as a threat Political Boys' ClubIt is said that Austen did not write all-male dialogues. There are some brief dialogues in Austen's novels, but Ryley includes entire scenes at gentlemen’s clubs and dinners where the men discourse on politics. During one of these, she goes after a “stubborn and inflexible politician, whose only merit was consistency, and the lustre of that was diminished, by his constant support of a weak cause.” He is described as being very flexible “in private life,” because he was always agreeing to do something and causing “bitter disappointment... for those, whose petitions or requests are forgotten the moment his word is passed to assist or relieve them.”

"Much more discourse, generally, to S_____n’s disadvantage, resulted from this observation…”

I don't know who S_____n is and I hope somebody can tell me.

In another conversation, young Lord Moseley talks about his dislike of faction and party. His cynical father Lord Mountcastle always represents the interests of the aristocracy and the landed gentry. Moseley admires “one independent member” of Parliament “who will never act against what he thinks the rule of right, or barter self approbation for pecuniary or honourary rewards.”

His father replies, “The person you allude to is as great as enthusiast as you are, and not less a martyr to popular opinion…. The Baronet, to whom you seem so partial, is rich and independent; but, see him reduced to comparative poverty, and there will be an end of his vaunted patriotism.”

I think they are speaking of the reform politician Sir Francis Burdett, who married an heiress to the Coutts banking fortune. The word "enthusiast" is not a compliment.

Again, Ann Ryley is letting her freak flag fly. Sir Francis was extremely popular with the people, not with the establishment. In 1810, he was arrested for publishing a blistering editorial against the government. There were riots in the street in his support. He spent some time in the Tower of London but then returned to his parliamentary duties. Consequences

It's clear that Ann Ryley was very interested in politics and current events and had no qualms about sharing her opinions. Fanny Fitz-York poses a bit of a challenge to the assertion that women could not be outspoken in Austen's time. Aha, but maybe that's why Fanny Fitz York did not get reviewed when it came out.

Perhaps, but a lot of novels never got reviewed. We can only speculate. I think if Ryley's novel had been considered truly outrageous, someone would have commented on it. Also, the Dictionary of National Biography (in the entry about her husband) said the novel was "successful," an assessment which must have been based on some kind of evidence.

One data point does not a refutation make, but there is certainly a striking contrast between Ryley and Austen.

Austen disapproved of travelling on Sunday, being flighty and thoughtless, and other matters of private conduct. She stayed out of commenting on public policy. I can think of one thing that Austen expressed an opinion about—next post.

Caroline Tylney Long's story is told in The Angel and the Cad: Love, Loss and Scandal in Regency England, by Geraldine Roberts

Caroline Tylney Long's story is told in The Angel and the Cad: Love, Loss and Scandal in Regency England, by Geraldine RobertsThis brief but informative blog post from the UK Parliament website lays out the political ramifications of Caroline's estrangement from her husband.

Another novel of the period, A Winter in London (1806) lavishly praises the Prince Regent and he even makes a brief cameo appearance.

In A Different Kind of Woman, the third volume of my Mansfield trilogy, an outspoken political reporter is sent to prison. More about my books here.

I discuss my objections to the "Austen was a radical" school of scholarship in more detail here.

Published on June 29, 2022 00:00

June 28, 2022

CMP#111: Satirical or Seditious? Fanny Fitz-York

“The reader fond of unravelling plots may gratify his—or her—curiousity at some old-fashioned, superseded circulating library, where Fanny Fitz York may yet be consulted…”

“The reader fond of unravelling plots may gratify his—or her—curiousity at some old-fashioned, superseded circulating library, where Fanny Fitz York may yet be consulted…” -- Richard Wright Proctor, Memorials of Bygone Manchester, 1880 CMP#111 Fanny Fitz-York, Part 3: Satirical or Seditious? Mrs. Bloomfield

Outspoken widows It's Ann Ryley week here at Clutching My Pearls. In which I'm examining the novel Fanny Fitz-York, Heiress of Tremorne (1818), by Ann Ryley (1760-1823).

Outspoken widows It's Ann Ryley week here at Clutching My Pearls. In which I'm examining the novel Fanny Fitz-York, Heiress of Tremorne (1818), by Ann Ryley (1760-1823). Richard Wright Proctor, quoted above, described Ann Ryley's writing style as "engaging." I agree; in fact, I find Ryley's style more engaging than the actual plot of Fanny Fitz York, which abounds with the usual amazing coincidences which you find in novels of this sort.

Mostly, though, I am amazed at Ryley's outspoken radical opinions, which Proctor does not mention.

Proctor is the only person I've found who discussed Fanny Fitz York, half-a-century after it was published. It received no book reviews when it came out in 1818. I think Ryley's novel deserves some scholarly attention, particularly from academics who tell us that women novelists of this era were constrained from giving their opinions because of the social and political climate of the times. In the previous post , I shared some of the opinions of the heroine and her mother around the sexual double-standard and the harsh penalties society meted out to fallen women. But there's still more, much more, to be shared about Ryley's political views. Rich, Outspoken Widows

The most spirited character in Fanny Fitz York is the wealthy widow Mrs. Bloomfield. Ryley's portrait of Mrs. Bloomfield demonstrates that--the patriarchy aside--widows with money had quite a bit of freedom and could say and do what they pleased. Escorted by her driver, groom, and footman, a widow can travel freely, like Mrs. Jennings in Sense & Sensibility. In Fanny Fitz York, Mrs. Bloomfield shows up unannounced and uninvited at other people's homes and proceeds to make sarcastic remarks about the other guests. However, nothing bad happens to Mrs. Bloomfield as a consequence of her unbridled tongue; her age and wealth protect her. The people she castigates are "types," such as fops and people who are noisy at the theatre--people who are put in the novel on purpose to be satirized. Mrs. Bloomfield is a comic character, but not a villain or a rogue.

True, there is a bit of a disclaimer directed to young ladies. Lady Anne's old friend Mr. Strictland observes that she is "more feared than loved," and that "satire is a dangerous, an unfeminine talent" which he advises the young heroine to avoid. Nevertheless, I think Mrs. Bloomfield is basically a device for Ann Ryley to share her own political views. And she is unabashedly against the Tory government and very critical of the Prince Regent. Have you been told that Jane Austen was a radical but could not share her views openly? Check this out:

Anti-War Statements

Anti-War StatementsIn Fanny Fitz York, Mrs. Bloomfield is vehemently opposed to the long-running war against Napoleon. The equivalent in a contemporary novel would be if one of the characters kept making long speeches unrelated to the plot condemning neo-con foreign policy and the way it exploded the national debt.

“The once-flourishing merchant or manufacturer is become bankrupt," Mrs. Bloomfield proclaims, "the shopkeeper looks in vain for his former customers; those who used to expend liberally, are, by the complexion of the times, obliged to limit their out-goings; and the poor are rising en masse for want of the commonest necessaries of life.

"These crying evils are produced by a war, in which we have no real interest, and burthens under which we groan, to pamper those who were before gorged; or to raise people from obscurity, who have neither private virtue nor public desert. But they allied to men in power, are placed upon the pension list, as an easy way of providing for poor relations without considering that every such pension adds to the load of those already sinking under the pressure of poverty.

"Do away all sinecures, and places filled by proxy—pension none but those who have substantial claims upon their country—and there would be no real cause for murmurings; but to know that the earnings of the poor are lavished upon the idle and the indolent—upon the drones in the hive of industry—who can wonder that complainings are heard in our streets, and that curses, not loud, but deep! follow the footsteps of our rulers!”

You want outspoken? Here's some outspoken

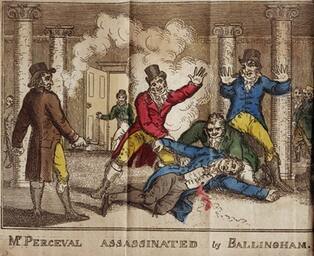

You want outspoken? Here's some outspokenOkay, so Mrs. Bloomfield says Britain has no real interest in fighting Napoleon and the poor are on the verge of rising up. All right. But I really sat up and took notice when Mrs. Bloomfield rushed into the drawing room and exclaimed:

“He’s shot in the House of Commons!....

“Shot! Who?”

“Percival,” replied the widow. “Killed by an assassin!” Mrs. Bloomfield is referring to the real-life assassination of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval on May 11, 1812.

Then she adds, “Had I guided his hand, the pistol should have been pointed elsewhere----"

Wait, what? Whoa! I don't think Mrs. Bloomfield is saying she would point the pistol in the air so it would discharge harmlessly and not kill the prime minister. She is saying that if it were up to her, some other political figure (maybe Castlereagh, but who knows) would be assassinated. Or... do you think she means the Prince Regent? Holy snapping turtles. Outspoken enough for you?

Just, wow. Okay, to resume the dialogue:

"'Had I guided his hand, the pistol should have been pointed elsewhere--but that between ourselves. What effect his death will have on the body politic I know not, but… we cannot change for the worse…”

Mrs. Bloomfield goes on to acknowledge Spencer Perceval's personal virtues and that he cared about his country. But his policies have led to “an impoverished revenue—a starving people—and the misery of thousands of individuals, who deplore the loss of husbands—fathers—brothers—and friends in this unjust, unnecessary, and destructive war. The most vicious character in existence could not have been a greater enemy to his King, his country, and his fellow citizens, than this reputed good man…”

Then she goes on to criticize the late William Pitt the younger: “Pitt, for instance, you’ll say was an honest man. He was so far honest that he would neither rob a church, nor cheat his tradesmen; but he took the money out of the pockets of the industrious to carry on unnecessary wars, and to subsidize powers, who laughed at our credulity…" She goes on in this vein for several pages until someone else rushes into the room with an actual plot point and the action resumes.

Robert Southey (1774 – 1843) Dangerous Sedition

Robert Southey (1774 – 1843) Dangerous SeditionThese anti-Tory diatribes have nothing to do with the plot, and in fact, I don't think Mrs. Bloomfield even plays a role in the plot in the way, say, that Mrs. Jennings does in Sense & Sensibility. She's there to act as a mouthpiece for Ann Ryley. Nobody else in the novel contradicts her, once she gets going.

I got to wondering about Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, the publishers of this novel, because they ultimately are responsible for the decision to print a novel with so much outspoken political material in it. Their chief claim to fame is that they published the earliest account of Parkinson's disease by Dr. Parkinson himself. But there is another episode in the history of this firm that sheds some light on their political views.

In 1813, the poet Robert Southey was appointed poet laureate, a sinecure that called for him to compose the occasional ode to the Royal family. In his youth, Southey--in common with other many literary figures--had been inspired by the French Revolution and the promise of reform, but his political views changed over time and he came to appreciate the stability of England's institutions. Southey's old radical friends regarded him as a sell-out.

In early 1817, Sherwood, Neely, and Jones brought out Wat Tyler, a verse drama about the leader of the 1381 Peasant's Revolt. The author of the poem was not given on the title-page but people who knew Southey recognized the poem as something he had written back in his radical days. He had shopped the manuscript around 23 years earlier and somehow Sherwood, Neely, and Jones had gotten their hands on it. Other publishers also printed it, as historian Stephen Basdeo explains: "[Southey] never registered the poem with the official Stationers back in 1794, [so] the work was technically out-of-copyright."

British radicals used Wat Tyler to poke the government in the eye by confronting them with the views of their own poet laureate.

Celebrity Evolution: from Commie to Cannes The publication of Wat Tyler was even raised in the House of Commons. The barrister and MP Sir Samuel Romilly charged that “a more dangerous, mischievous, and seditious publication had never issued from the press—clothed in the most seductive language, it was calculated to excite a spirit of disaffection and hatred to the Government and Constitution of the country, as well as open rebellion against the Sovereign.” I think Romilly was laying it on thick because he was a reform MP daring the government to prosecute their own poet laureate during a time when they had suspended habeas corpus and were clamping down on antigovernment protests. (But I'm not an expert. For a discussion of the Wat Tyler kerfuffle, try the Romantic Circles website.)

Celebrity Evolution: from Commie to Cannes The publication of Wat Tyler was even raised in the House of Commons. The barrister and MP Sir Samuel Romilly charged that “a more dangerous, mischievous, and seditious publication had never issued from the press—clothed in the most seductive language, it was calculated to excite a spirit of disaffection and hatred to the Government and Constitution of the country, as well as open rebellion against the Sovereign.” I think Romilly was laying it on thick because he was a reform MP daring the government to prosecute their own poet laureate during a time when they had suspended habeas corpus and were clamping down on antigovernment protests. (But I'm not an expert. For a discussion of the Wat Tyler kerfuffle, try the Romantic Circles website.)I don't see any record that the government took official action against Sherwood, Neely, and Jones for publishing Wat Tyler. Fanny Fitz York, with its anti-war diatribes and anti-Royalist sentiment, came out at the end of 1817 and I haven't found a record of an official--or unofficial--reaction. Yet in its pages, we have a female character saying that the only thing wrong with the assassination of Spencer Perceval is that the assassin picked the wrong target.

I can only say that Fanny Fitz York provides an example of an outspoken female author making her political opinions clear, and neither she nor her publisher were officially punished.

And we're still not done! Hang on for more Mrs. Bloomfield... After Napoleon escaped from Elba in March, 1815, and re-took the French throne, not everybody agreed that it was England's job to use its army to re-install the Bourbon royal family. Ann Ryley was certainly opposed to the high cost and the death toll of the war against Napoleon, and so were the radicals of Manchester, which tells you where Ryley stood on the political spectrum. I've already mentioned that Ryley, like me, is a late-blooming author. And I was pretty tickled to see that we both used the assassination of Spencer Perceval in our novels! Spencer Perceval was the only British Prime Minister to be assassinated, and naturally at first people wondered if it was the first step in a popular uprising or rebellion. But the assassin turned out to be a bankrupt man whose disappointment and frustration had sent him over the edge.

For my novel A Marriage of Attachment, Fanny Price befriends Mrs. Bellingham, the wife of the assassin, who has to struggle to support her children while her husband stalks the corridors of power in London.

Today Robert Southey is best remembered for giving us an early version of the story of the Three Bears and for writing a discouraging letter to Charlotte Bronte. (1:27) Female Radicals of Manchester: "the indelible disgrace of having been engaged in the late unjust, unnecessary, and destructive war against the liberties of France that closed its dreadful career on the crimson plains of Waterloo, where the blood of our fellow-creatures flowed in such mighty profusion that the fertile earth seemed to blush at the outrage offered to the choicest works of heaven." Richardson, Megan. 2015. “Authors and Their 'Mischievous' Books: The Salutary Experience of Southey v Sherwood.” Authorship (Gent) 4 (1).

Published on June 28, 2022 00:00

CMP#110 Of Wives and Prostitutes

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels.

Click here for the first

in the series. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. This is the second post about Ann Ryley (1760-1823) and her forgotten novel, Fanny Fitz-York (1818). CMP#110:

Fanny Fitz York, part 2:

Outspoken Women, Conventional Morality

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels.

Click here for the first

in the series. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. This is the second post about Ann Ryley (1760-1823) and her forgotten novel, Fanny Fitz-York (1818). CMP#110:

Fanny Fitz York, part 2:

Outspoken Women, Conventional Morality

In my last post

, I introduced a long-neglected novel, Fanny Fitz-York: the Heiress of Tremorne (1818). Fanny Fitz-York is very much female-centered. There are love interests, of course, and there is a hero, but for much of the novel, we've no idea which one he is. There are also two older male characters, the curate and the kindly old advisor, but really, they are only necessary to the plot because they are escorts. Without them the female characters could not, with propriety, move from "A" to "B" as needed. There is also a villain, but the driving energy of the story comes from the supporting cast of female characters.

In my last post

, I introduced a long-neglected novel, Fanny Fitz-York: the Heiress of Tremorne (1818). Fanny Fitz-York is very much female-centered. There are love interests, of course, and there is a hero, but for much of the novel, we've no idea which one he is. There are also two older male characters, the curate and the kindly old advisor, but really, they are only necessary to the plot because they are escorts. Without them the female characters could not, with propriety, move from "A" to "B" as needed. There is also a villain, but the driving energy of the story comes from the supporting cast of female characters.In her preface, author Ann Ryley makes the pro forma disclaimer—very typical for the times—that she would rather be accused of lack of wit or invention, rather “than hear myself accused of shocking the nicest delicacy by a hint or an innuendo, that could raise a blush in the cheek of modesty.”

Yet, Ryley takes us to places Jane Austen never did—to a courtroom, to a bordello in London, to prison cells. Ryley shows poverty and destitution on the streets of London. And the curate’s sister Julia brings “everlasting disgrace” on her family by becoming a prostitute.

Repentance Compassion for fallen women

Repentance Compassion for fallen womenJulia Cavendish, whose older sister Rosette is a governess/companion to the heroine, runs off with a Wickham-like character. He soon abandons Julia in London and she becomes a prostitute, sinking much lower than Lydia in Pride & Prejudice. Also as with Pride and Prejudice, Julia's lapse seriously threatens the marital prospects of her sister Rosette. The curate fears “’tis more than probable a sister’s peace may be the sacrifice, for what mother would willingly yoke her son to a tainted stock?” Rosette's suitor is Sir Herbert the baronet, who starts out as a bit of a flighty man-about-town, but reforms when he falls in love with Rosette.

Julia is found—in fact she’s retrieved by Sir Herbert, just as Darcy helps to retrieve Lydia. (Sir Herbert doesn't have to lay down a lot of money to do it, but he takes Julia back to her brother.)

In Pride & Prejudice, Mr. Bennet rejects the advice of Mr. Collins to "forgive Lydia as a Christian" but forbid her from returning home, ("That is his notion of Christian forgiveness!").

In Fanny Fitz-York, Miss Simpkin, the spinster aunt who runs the curate's household, is quite unhappy that Julia has been given shelter there. She asks Fanny, the young heroine, to “ask your mamma to speak to his reverence. He will mind her more than any body else, and I dare say she might persuade him to turn her out.”

“Turn her out, madam!” said Fanny, in amazement. “Turn out his own sister!... That I am sure my mother will never do.”

Miss Strictland's answer makes you wonder just how poor Julia is managing living under the same room with this Mrs. Norris-like character: “Why, surely, Lady Ann cannot approve of his keeping her here, to the scandal of his cloth and the disgrace of his profession!”

Fanny replies: "The scandal and disgrace, madam, would be in turning her out. His profession teaches repentance and forgiveness of sins; but, by discarding her, he would shut out all prospect of the one, and by the same rule, all possibility of the other; and be, in fact, answerable for her misery here and hereafter.”

I should mention that Fanny Fitz-York's mother Lady Anne takes the same compassionate approach with both men and women who stray from the path of virtue. She rescues a highwayman who is captured by a mob and is in danger of being beaten to death. She gets him medical attention, listens to his story, and gets him back on his feet.

In other words, this is not just about female sexuality, it's about Christian beliefs around sin and redemption. The author also protests the strict criminal codes of the day.

Although Julia is reclaimed and repentant (and, surprisingly, she does not die of wasting heroine disease), her sister Rosette knows this is a dire scandal. Rosette insists that her lover Sir Herbert tell his mother the whole unhappy truth. Luckily, Sir Herbert's mother is broad-minded and Rosette and the baronet are wed.

By the way, I am mentioning these parallels to Austen not because I think Ann Ryley borrowed them from Pride & Prejudice. I think, rather, both novels touch on situations which frequently arose in real life and were widely used in novels.

However, Ann Ryley goes farther than Austen. She also goes out of her way to criticize what we might call conservative or evangelical elements in her society. Another minor character, Mary Leigh, is left destitute in London in winter. When she rushes up to a strange man in the street, deliriously thinking it is her husband, the man assumes she is a prostitute:

beating hemp He was a member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice; and with those gentlemen, feeling is lost in what they falsely conceive to be duty. With savage brutality he shook her from him; and in accents loud and authoritative, threatened the watchhouse for this offence, and in case of repetition, painted the miseries of beating hemp in Bridewell; "an employment,' he continued, 'well befitting such pests as you."

beating hemp He was a member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice; and with those gentlemen, feeling is lost in what they falsely conceive to be duty. With savage brutality he shook her from him; and in accents loud and authoritative, threatened the watchhouse for this offence, and in case of repetition, painted the miseries of beating hemp in Bridewell; "an employment,' he continued, 'well befitting such pests as you."As he uttered the last words, Mary dropped senseless to the pavement, where this humane and religious member of a society, whose partial edicts leave the rich unmolested, but punish the poor with unjust and cruel severity, left her to recover, or die... The Society for the Suppression of Vice was a real society aimed at discouraging profane language and disorderly conduct, among other things. William Wilberforce was one of the founding members. Was this little kick at the Society necessary to the story? Ryley could have had included a heartless man without explicitly linking him to the Society and suggesting that every member of that Society was equally heartless. So we see that, although she risked alienating readers on one end of the political spectrum, Ryley went ahead and portrayed this evangelical group as lacking mercy and benevolence.

The Sweet Delights of Love, Gillray Spirited Women

The Sweet Delights of Love, Gillray Spirited WomenAnn Ryley also gives us a strong feminist statement from Lady Maria, Fanny's cousin, who writes to say she longs to be allowed to visit her aunt Lady Anne, but unlike her brother Lord Moseley, she can't just hop on a horse and go to Tremorne: “as I wear a petticoat—alias, a badge of slavery,—I must yield, though reluctantly, to imperious necessity." That one statement is more pointed that anything Austen ever wrote about the status of women.

Despite the restrictions on their lives, Ryley’s female characters act their parts with brio and self confidence. Even Miss Simpkin, the stereotypical spinster we met above, is very sure of herself and we're told the curate has to handle her with care.

Another minor character, Major Stokes, is totally dominated and henpecked by his wife: “and thus, passive obedience and non-resistance not only injured his peace at home, but ruined his character abroad.” Both he and his brother-in-law Mr. Gaskell eventually rebel against their wives and obtain legal separations. Clearly, Ryley has no issue with leaving a spouse you no longer love, as opposed to sticking it out 'til death do you part.

Another character, Lady Milford, drops a wicked reflection on her husband in front of their nephew George when Lord Milford tries to persuade him to enter politics: "Lady Milford entered the room, and hoped her lord was not going to spoil a rational creature by transforming him into a politician.

“'Are rationality and politics at variance?' enquired her nephew.

“'Entirely, my dear George, rationality, and sociability, and politeness, and all the common courtesies of domestic life are sacrificed—and for what? jealousy, heart burnings, envy, and a thousand other bad passions, which I sure are a great torment to their possessor. I was bewitched after what I saw at home to marry a statesman, who is good for no earthly thing out of the counsel-chamber, whatever he may be in it.'” In Volume III, Lord Milford is laid up with the gout and he orders Lady Milford to stay at home with him. She writes to a friend that she hopes for a visit from their mutual acquaintance Mrs. Bloomfield: “[It] will be an act of charity where I would join her in railing at the follies of mankind, than which she will never find a better subject than the lord of this noble mansion who, between politics and the gout, is most insufferably tiresome... Would fate have woven a different web for me! Though the world had thereby been deprived of an example of fortitude and philosophy every female is not endowed with.”

In addition to the strong opinions expressed by her female characters, Ryley also drops in her own editorials, such as this one in Volume III: “A gentleman of spirit may ruin his tailor, his shoemaker, his hosier, with impunity, and not, thereby, lessen his credit with his associates, but let him contract a gambling debt, and be either unwilling or unable to pay it, he is posted for a poltroon, and rendered incapable of mixing with honourable men. There is something vitally wrong in this…”

An Old Maid, Rowlandson Outspoken views but conventional morality

An Old Maid, Rowlandson Outspoken views but conventional moralityAlthough Ann Ryley is what we might call liberal or progressive in her views, she is still very conventional in her emphasis on female chastity. Ryley made a point of protesting that she stayed away from anything remotely ribald in Fanny Fitz York. The market called for chaste heroines, and the critics gave a thumbs down to novels which had no "moral tendency." Ann Ryley complied with this expectation. Julia's downfall is just that—a falling off from the expected high standard of virtue.

Back then, it was all about the morality. Authors very often declared themselves to be on the side of morality. As I mentioned above, Ryley protested she didn't want to “raise a blush in the cheek of modesty.”

And she finished her novel with: “I declare, honestly and candidly, that to instil virtue and morality has been my aim, however I may have erred in the means."

You don't put disclaimers like that in your preface and your conclusion unless you are responding to strong social sanctions. In those days, authors and publishers had to reassure everyone that they weren't contributing to moral degeneracy. It's like a company posting their diversity statement or movie credits assuring everyone that no animals were injured or harmed. Novels were in themselves controversial and a disclaimer like Ann Ryley's was a way of saying the novel could be safely read by young ladies. As you can see, Ann Ryley is much more explicit with her editorials than Jane Austen. Well hang on, we've barely gotten started. You haven't met Ryley's most outspoken character, Lady Milford's friend Mrs. Bloomfield. Next post. The Society for the Suppression of Vice also makes an appearance in my novel, A Different Kind of Woman. The president of the Bristol chapter raises a ruckus when he discovers that French prisoners of war have been making and selling naughty carvings and pictures.

Published on June 28, 2022 00:00

June 26, 2022

CMP#109 Fanny Fitz-York: the "Slighted Heroine"

It's Ann Ryley week at Clutching My Pearls! A new post every day about Ann Ryley (1760-1823), a forgotten novelist, and her novel Fanny Fitz-York, which was not reviewed when it was first published. For more reviews of obscure and forgotten novels, click "Authoresses" at the right. I'm excited to introduce author Ann Ryley to you... CMP#109: Fanny Fitz-York: the "slighted heroine." Ann Ryley, part 1

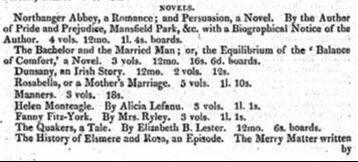

It's Ann Ryley week at Clutching My Pearls! A new post every day about Ann Ryley (1760-1823), a forgotten novelist, and her novel Fanny Fitz-York, which was not reviewed when it was first published. For more reviews of obscure and forgotten novels, click "Authoresses" at the right. I'm excited to introduce author Ann Ryley to you... CMP#109: Fanny Fitz-York: the "slighted heroine." Ann Ryley, part 1  A listing of new novels for 1818 in The Quarterly Review includes Austen's two last novels and Ryley's Fanny Fitz-York I got a lot more than I bargained for when I started reading Fanny Fitz-York, Heiress of Tremorne (1818.) I expected just another novel of the long 18th century and I picked this one up as part of my investigation into whether the name “Fanny” connoted “sex worker” for 18/19th century novel readers. (It didn't). In Fanny Fitz-York, I discovered a novel filled with social and political criticism and strong female characters.

A listing of new novels for 1818 in The Quarterly Review includes Austen's two last novels and Ryley's Fanny Fitz-York I got a lot more than I bargained for when I started reading Fanny Fitz-York, Heiress of Tremorne (1818.) I expected just another novel of the long 18th century and I picked this one up as part of my investigation into whether the name “Fanny” connoted “sex worker” for 18/19th century novel readers. (It didn't). In Fanny Fitz-York, I discovered a novel filled with social and political criticism and strong female characters.Fanny Fitz-York came out in late 1817, the same time as Jane Austen's posthumous novels Northanger Abbey and Persuasion (though all are officially designated as having been published in 1818). Author Ann Ryley was 58 years old when her novel was published, so I've got some kindred feeling for her. I'll share more of her life story later this week.

The Dictionary of National Biography entry for Ann's husband R.W. Ryley described Fanny Fitz-York as a "successful" novel but the only thing approaching to a review or reaction that I've found is a brief paragraph from 1860. Richard Wright Proctor, a literary historian and travel writer, called Fanny Fitz-York “a cleverly-written novel, of considerable interest, especially to women." He added, "though Fanny Fitz-York is now unknown to the majority of readers, who, in their eager pursuit of something new, are apt to overlook the treasures of the past, it still has an abiding place in the circulating library. Here the curious may find this slighted heroine of romance, this forgotten belle of a season, taking her natural rest, half buried in kindred dust, and literally shelved...”

Should we wake Fanny Fitz-York from her slumbers? I think so, given the current academic focus on the social and historical context of novels, as opposed to intrinsic literary merit. Which is not to say Ryley is a mediocre writer; I think she's better than many of her contemporaries. And she holds up much better than her husband, who published five volumes of memoirs clogged with clichés: “A fortnight ago, seated in my cottage, enjoying the height of human felicity—peaceful, domestic, rural comfort—now on my way to the metropolis, preparing to merge into the vortex of public life, and plunge into the troubled sea of dramatic misery!”

Ryley hasn't gotten any attention from scholars but I think she's worth studying because she offers a striking contrast to Jane Austen, for reasons I'll explain.

But first, a bit about the story itself... The novel starts in typical fashion with a re-cap of the genealogy, social status and income of two neighbouring families in a small village. Like many of her contemporaries, (for example, as Austen does in Sense & Sensibility,) Ryley uses death to kick off the plot; she starts by pruning unnecessary characters from the family tree for both families.

The opening reminds us that people of this era were used to high infant mortality rates and could read a sentence like this without blinking: “Mr. Fitz-York married Lady Ann Grosvenor under the fairest auspices; and for several years, during which period they had six children, though only one daughter survived, no couple could be found whose happiness surpassed theirs.”

But alas, Lady Anne, mother of our heroine, loses her husband and her beloved brother Frederick in a boating accident. At the reading of their wills we learn that the late lamented Frederick has a natural son, about ten years old, but nobody knows where the mother and son are.

The late Mr. Fitz-York didn't want his only daughter to be the prey of fortune hunters, so it's given out that she has only a 5,000 pound inheritance.

So after all the introductory deaths, we’re left with one desolate widow and her little daughter living in a gloomy tower. In the adjoining village we have a widowed curate, his "old maid" sister-in-law, and his twin babies. There's also Henry Tudor, a nice young man living with the curate for a private education, just as Edward Ferrars was privately educated in Sense & Sensibility.

Young girl and her governess, Jean-François Portaels Supporting characters

Young girl and her governess, Jean-François Portaels Supporting charactersLady Anne has some relatives who have managed to not die, but they are snobby aristocrats. We’ll meet them later. First, the childhood of Fanny, which gives the author a chance to expound on educational theories for children. ( As we have seen , this is a huge topic in novels of the day, especially as regards the consequences of a good or bad education on the future conduct of the characters). The lovely Rosette, sister to the curate, is hired as Fanny’s governess so Fanny can have a youthful companion in her isolation.

Sweet and artless little Fanny is not allowed to receive “bribes” for good behaviour, only “rewards.” Her favourite rewards are reading the bible and making clothes for the poor children of the village. I might mention at this point that the author Ann Ryley never had children and there’s no indication in her life story that she ever met any children. But to continue.

The story expands out to some of the other inhabitants of the quiet village. The Gaskell family consists of a gossiping Greek chorus of mother, two silly daughters and a wastrel son, living with a very disappointed Mr. Gaskell. Mrs. Gaskell is a narrow-minded, vulgar woman who doesn’t understand what her embittered husband says. Like the Bennets in Pride & Prejudice, there is no meeting of minds. The three Gaskell offspring are used in the novel as examples of ignorance, selfishness, and vulgarity. Their stories serve as a contrast to the amiable Fanny and her friend/governess Rosette.

Anyway, soon Fanny is 16, old enough to see something of the world and commence her adventures as a heroine. Ryley playfully indicates to her readers that she cannot bring herself to obey novelistic conventions with asides such as: “unlike many heroines, our Fanny was sometimes hungry," and "the amiable timidity,—the overwhelming modesty, —and excessive pusillanimity, of some heroines, may throw ours into the shade. Be that as it may, we are incapable of altering her…”

Lady Ann, Fanny, and Rosette set out for a tour of seaside attractions with a family friend, an older man named Mr. Strictland. They visit Lyme Regis and attend a public ball, giving the reader a picture of Lyme Regis as it was when Jane Austen visited with her family. The novel is set in 1812, the same year that pioneering paleontologist Mary Anning dug up an ichthyosaur skull, but there is no mention of fossils, just those flint-hearted noble relatives. The relatives keep Lady Anne and Fanny at arm’s length because they erroneously suppose that Fanny is poor and they don’t want her to catch the eye of her cousin Lord Moseley. But during their travels, Lady Anne’s carriage breaks down and a handsome gentleman offers them his own carriage to get out of the rain. He calls himself ‘Moseley.’ He pretty much joins Lady Anne’s party, travelling along the coast with them.

Flawless disguise Spoilers follow

Flawless disguise Spoilers followIn the silliest contrivance of the plot, it turns out that 'Moseley" is indeed Lord Moseley, who courts Fanny while wearing a wig and calling himself just Moseley. Everyone remarks on the amazing resemblance between this Moseley guy and Lord Moseley, but nobody says, “what do you mean? that’s just Lord Moseley wearing a wig.” Also, I don’t think a cautious prudent widow like Lady Ann would let some complete stranger, no matter how gentlemanly, hang around her daughter unless he could provide some personal references. Were we, the readers, supposed to be hoodwinked as well, or were we supposed to wonder if 'Moseley' is really Fanny's cousin, the missing illegitimate son of the late Frederick? Or is it all a tongue-in-cheek joke?

In addition to Lord Moseley, we've got other possible contenders (not counting the villain) for Fanny’s hand. In Volume I there’s her childhood friend Henry Tudor; more suitors pop up after Fanny gets to London.

Regency-era Court Dress A false start in matters of the heart

Regency-era Court Dress A false start in matters of the heartLady Ann is astonished and vexed when a false marriage report is printed in the newspaper, announcing Fanny’s engagement to Lord Moseley. “To have [her daughter’s] name bandied about in the public prints, was a matter so repellant to her native delicacy, and to every sense of propriety, that she would have shrunk from the exposure, even had the statement been correct…”

The snobby relatives are likewise vexed and accuse Lady Ann of having spread the rumour. Lady Ann is so annoyed that she tells them that there is no way she would allow Fanny to marry Lord Moseley because of the rude and shabby way they’ve always treated her, and they would no doubt treat Fanny badly as well.

When Fanny attends her debut at St. James’ Court, Lord Moseley shows up and makes a scene. “Fanny, you have undone me! You, and your dear mistaken parent have driven me to the edge of the precipice, and this interview decides my fate as far as respects the present world.”

If I were a beautiful young heroine making my bow to the Queen at St. James’s Court I wouldn’t be impressed by a hero who drags me into a private corridor (thus compromising my reputation) to threaten he’s going to kill himself, then gets into a physical altercation with another admirer—whose bloody nose spatters on my court dress—then challenges him to a duel so now I have to worry about them killing each other. Not to mention that bizarre business about wearing a wig and lying about it for weeks.

I think Austen would have made more of the entire Lord Moseley sub-plot; there would have been some moral lesson behind building up a potential hero and then taking him off the chess board, which I can't discern in this novel. I don't think Fanny learns anything from this experience. She is already a "picture of perfection" heroine and has nothing to learn. And that’s enough about the plot. This is a long novel, at least one-third as long as Emma or Mansfield Park, and it wasn’t the plot that kept me turning the pages, it was the author’s social commentary and the way she openly shared her political opinions. Most of her opinions are put in the mouth of an outspoken widow, whom we'll meet later in this series.

"Can we talk?" We can't mention debuts at the court of St. James without mentioning how ridiculous hoops look under a high-waisted Regency-style dress. Ann Ryley thought the same: "of all the unnatural deformities which the caprice of fashion has at various times invented, the whalebone petticoat is the most unwieldly, the least easily managed, and grace is no longer grace, so encumbered…” Of her heroine, Ryley spares herself the effort of a detailed description: “I dare say my youthful female readers will think me unpardonably deficient if I omit the description of our heroine’s dress on this grand occasion. I once hoped the newspapers would have anticipated me, but guess my mortification, when the one I daily take was served up with my breakfast, to find no mention whatever made of Miss Fitz-York. I waded twice through the monotonous description of court costume, and court presentations, without finding my favourite Fanny’s person, dress, or behaviour noticed; although the former and the latter were, according to my old-fashioned judgement, unrivalled that day at St. James’s…. A fire in the palace of St. James in 1809 put an end to court levees for a while. Ann Ryley mentions that "there had been no public Court for a considerable length of time" when her heroine made her appearance. I used the 1809 fire in my novel, A Contrary Wind, to disappoint the hopes of the Bertram girls, who are unable to make their curtsey to the queen.