Lona Manning's Blog, page 18

January 2, 2022

CMP#80 "Give A Girl An Education"

"Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody."

"Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody." -- Mrs. Norris, Mansfield Park CMP#80 Mansfield Park and the Theme of Education: an Introduction

1983 Mansfield Park mini-series Mansfield Park is--by far--the most misunderstood of Jane Austen’s novels in modern times. Canadian author Douglas Glover says: "Mansfield Park is a brilliant book, a great book, breathtaking in its invention and orchestration. The British critic of the novel Q. D. Leavis called it 'the first modern novel in England.' And yet it is alien territory for the contemporary reader."

1983 Mansfield Park mini-series Mansfield Park is--by far--the most misunderstood of Jane Austen’s novels in modern times. Canadian author Douglas Glover says: "Mansfield Park is a brilliant book, a great book, breathtaking in its invention and orchestration. The British critic of the novel Q. D. Leavis called it 'the first modern novel in England.' And yet it is alien territory for the contemporary reader."Notice that Glover speaks of invention and orchestration; his first focus is on Austen's craft, her innovations as a writer. I hardly feel qualified to opine about the development of the novel, but I am afraid that many university students today are signing up to learn about English literature and they get a history lesson instead, and they walk out having learned nothing about the development of the novel.

Yes, Glover's "alien territory" refers to Austen's stern moral universe. If you have an understanding of the economics and the religious beliefs of the Regency period, then you can better understand that moral universe. However, I am speaking of history which treats the past not as a chronicle of progress but a catalogue of crimes.

Elsewhere, I have disputed the contention that Mansfield Park is an extended symbolic protest of slavery. I’ve shared evidence to show that it was not controversial or dangerous to oppose slavery in Austen's day and many novelists did so . See here, here, and here .

But go ahead and enjoy or condemn Mansfield Park however you like. If you think Fanny’s a wimp and Mary Crawford is the real heroine, that’s your call. If you cannot stomach a novel about a family who reap no punishment for owning enslaved persons, I respect your feelings. When Sir Thomas feels anguish and remorse over his failures as a parent—but not over owning people like property—I understand why it’s just too jarring. When Edmund rejects Mary Crawford as being morally flawed, while he's been living off the proceeds of slavery--well, I take your point.

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris I merely differ with those who argue that Austen intended for us to think that Mary Crawford or Maria Bertram are the real heroines of Mansfield Park. Despite the fact of Sir Thomas's West Indian property, I think Edmund Bertram and Sir Thomas are in fact intended by Austen to be the moral arbiters of the novel, along with Fanny. In this post, and in future posts, I will lay out my reasons for concluding that Mansfield Park is chiefly a novel about educating your children properly and what happens when people neglect their duties.

Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris I merely differ with those who argue that Austen intended for us to think that Mary Crawford or Maria Bertram are the real heroines of Mansfield Park. Despite the fact of Sir Thomas's West Indian property, I think Edmund Bertram and Sir Thomas are in fact intended by Austen to be the moral arbiters of the novel, along with Fanny. In this post, and in future posts, I will lay out my reasons for concluding that Mansfield Park is chiefly a novel about educating your children properly and what happens when people neglect their duties.It’s a novel about how easy it is to deceive oneself. And Austen writes brilliant dialogue showing people deceiving themselves.

Austen shows us that in real life, evil does not announce itself with devil’s horns. Austen gives us nuanced portraits of well-meaning people who cause harm.

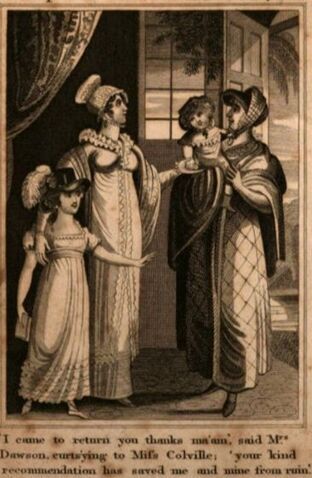

She gives us an unforgettable portrait of a self-satisfied hypocrite. She shows us that standing up for virtue, for correct behaviour, can be a lonely business... Female education--specifically, how to educate females properly--was a common theme in novels of Austen's time. Examples include Jane West's The Advantages of Education (1793) and A Tale of the Times (1799), Elizabeth Helme's Albert, or, the Wilds of Strathnavern (1799), Hannah More's Coelebs in Search of a Wife (1809), Henry Kett's Emily, a Moral Tale (1809), Eleanor Sleath's The Bristol Heiress, or, The Errors of Education (1809), Edward Nares' Thinks I To Myself (1811), Mrs. Green's I'll Consider of It (1812), Mary Brunton's Discipline (1814), Susan Ferrier's Marriage (1818), and Ostentation and Liberality (1821), by Arabella Argus.In The Advantages of Education, Mrs. Williams is reunited with her daughter Maria after many years’ separation and undertakes to finish her education. The author devotes all of Chapter V to an editorial on female education. “She clearly saw that, like a rich neglected garden, her daughter’s uncultivated mind ran into disorder and irregularity…”In Coelebs in Search of a Wife, the bachelor Charles takes advice from his mother about finding a well-educated wife: “The education of the present race of females is not very favourable to domestic happiness. For my own part, I call education, not that which smothers a woman with accomplishments, but that which tends to consolidate a firm and regular system of character; that which tends to form a friend, a companion, and a wife.”In I’ll Consider Of It, a grandfather disputes with his daughter over the education of his granddaughter Emily: “this was a point they never could agree upon—he hated all boarding-schools; but was particularly averse to his grand-daughter being kept any longer, now she was grown a fine tall girl, in a place where he declared she would now learn nothing but deceit and vanity, without any kind of domestic economy.”Grizilda Twist in Thinks I To Myself “had many masters, (ie expert tutors in various subjects), and therefore might naturally be expected to know much;--far more than I thought it necessary for her to know:--she had learnt I know not what;--music, dancing, painting, these were common, vulgar accomplishments;--she had attended a world of fashionable lectures, and was therefore supposed to understand Chemistry, Geology, Philology, and a hundred other ologies, for what I know, enough, as I thought, to distract her brain…”In Discipline, the spoiled young heiress recalls her boarding-school days: “We were taught the French and Italian languages; but in as far as was compatible with these acquisitions, we remained in ignorance of the accurate science, or elegant literature to which they might have introduced us. We learnt to draw landscape; but, secluded from the fair originals of nature, we gained not one idea from the art, except such as were purely mechanical.” People who read Mansfield Park when it was published would have recognized that it dealt with a familiar and widely-discussed theme. Perhaps that understanding has been lost today, because while we still read Mansfield Park, few people read those other novels.

One reason Mansfield Park has endured while other novels are forgotten is Austen's subtlety in comparison with the didactic tomes of other authors of the day. Unlike her peers, Jane Austen seldom breaks off from her story-telling to lecture and moralize. Her characters are more than stereotyped walking, talking points of view, and her humour is subtle and delicious. Compare any of the passages on education in the novels I've listed above with the hilarious conversation of the Bertram girls with Mrs. Norris when they boast of their knowledge of all the "metals, semi-metals, planets, and distinguished philosophers" to really appreciate how Austen makes her point without lecturing her readers.

So, two things here: first, I think professors should be teaching their students about Austen's craft, not inviting them to fulminate against the patriarchy. Good heavens, if young people can't handle a little patriarchy, they must, to quote Henry Crawford, "have a constitution which nothing could save."

Liz Crowther as Julia Bertram, 1983 Secondly, when Austen does comment on the action in her stories, or talk to us about her characters, these rare occasions should be noted.

Liz Crowther as Julia Bertram, 1983 Secondly, when Austen does comment on the action in her stories, or talk to us about her characters, these rare occasions should be noted.I think we can safely conclude that when she addresses her readers directly, she is pointing something out to us, something she thinks is important.

There are more of these moments of direct comment from Austen in Mansfield Park than in any other of Austen's novels.

Almost invariably, her editorial interjections in Mansfield Park have to do (broadly speaking) with education and the consequences of a faulty upbringing.

Below I've quoted one of the most notable examples but I will discuss these authorial interjections in greater detail further along; “The politeness which [Julia Bertram] had been brought up to practise as a duty made it impossible for her to escape [the boring company of Mrs. Rushworth]; while the want of that higher species of self-command, that just consideration of others, that knowledge of her own heart, that principle of right, which had not formed any essential part of her education, made her miserable under it." In addition, the topic of education arises in dialogue: “’I know [Mary Crawford’s] disposition to be as sweet and faultless as your own,’ [Edmund tells Fanny] but the influence of her former companions makes her seem—gives to her conversation, to her professed opinions, sometimes a tinge of wrong…’

“’The effect of education,’ said Fanny gently.” In short, Mansfield Park is an exploration of the consequences of faulty education. The Bertrams neglected the formation of their daughters’ characters. Henry and Mary Crawford are also brought up in ignorance of virtuous principles. The Bertram girls and the Crawfords are intelligent people, and the Crawfords are witty and discerning. But they are all flawed human beings. The novel lays out the circumstances which lead to Maria Bertram's elopement with Henry Crawford, and the consequences that arose from it.

I’ll expand on this idea, and compare Mansfield Park to some other novels of this period that took up the same theme, in future posts. I'll be talking about the Regency version of nature versus nurture, Regency ideas about intelligence and knowledge, the vast gulf between Regency notions of female chastity and the present day, how education is tied to social class, and the debate around female education and accomplishments in Austen's time. In my variation on Mansfield Park, A Contrary Wind, we briefly meet Miss Lee, the Bertrams' former governess, who is an off-stage character in Austen's novel. We learn a little about her backstory too. Click here for more about my books. Harriet and Ellen of the Reading Jane Austen podcast have begun their close reading of Mansfield Park.

Maggie and Kristin of First Impressions podcast have three episodes on Mansfield Park and more episodes on the various adaptations of the novel. The first episode is here . Both podcasts are a treat for Austenites.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality. Much has been written about Austen. Click here for the first in the series.

Published on January 02, 2022 00:00

December 16, 2021

CMP#79 My Article in Persuasions On-line

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series.

CMP#79 Jane Austen and Elizabeth Helme

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series.

CMP#79 Jane Austen and Elizabeth Helme

The Jane Austen Society of North America has published my article "Admiral Croft and the Rich Uncle" in their December online edition of Persuasions. The article is about some striking similarities that I've come across between a 1799 novel by Elizabeth Helme and two of Austen's novels.

The Jane Austen Society of North America has published my article "Admiral Croft and the Rich Uncle" in their December online edition of Persuasions. The article is about some striking similarities that I've come across between a 1799 novel by Elizabeth Helme and two of Austen's novels.I previously wrote about Elizabeth Helme in this blog post. She was a hard-working author who enjoyed considerable popular success although she died in illness and poverty. I would not say that Helme was an influence on Austen in the sense that Austen emulated her. I would not compare Helme to Samuel Johnson, Cowper, or Fanny Burney--all writers whom Austen particularly admired. However, I think the evidence is clear that Austen read Helme's novels and made use of some of her dialogue, characters, and plot contrivances.

In this case, the novel I'm speaking of is called Albert, or, The Wilds of Strathnavern. It contains a rich uncle, a character named Colonel O'Bryen, who I argue is the prototype of Admiral Croft.

Albert also makes use of private theatricals for plot purposes. Other Austen scholars have pointed to other contemporary novels which mention private theatricals as the possible source for Austen's use of them in Mansfield Park, but in Albert, the private theatricals are--as with Maria Bertram and Henry Crawford--used for the purposes of seduction.... Here is what The New London Review had to say about Albert: "There is some ingenuity in the construction of this novel, and an agreeable diversity in the dramatis personae, that entitles its author to be ranked, though not in the first, yet not below the second class of novelists. Her language, however, is frequently incorrect, and sometimes, we think unnecessarily debased by colloquial expletives and barbarisms." (This is a reference to Colonel O'Bryen's dialogue. He says "Zounds" and "What the Pie" a lot.)

Another reviewer wrote: "This novel contains little originality or strength of character but it is amusing in its story, and respectable for the propriety of moral sentiment. Many false notions of honour are properly exposed, and the vices of dissipation are painted with a truth of colouring that confers equal credit on the intentions and the abilities of the authoress."

Austen's happiest couple I won't recap my entire article here, but I will add that an alternate or additional source of inspiration for Admiral Croft's sanguine attitude to matrimony might be that sailors apparently had the reputation for quick courtships in general. In an 1817 novel, Elizabeth, Her Lover and Husband, Captain Beverly marries in haste: “With the proverbial carelessness of a sailor, he married a widow lady, after having seen her three times at a place of public amusement…. This union was productive of but little happiness-contracted without any knowledge on his side of her character, habits, or pursuits, and on hers from pecuniary, or, as they are sometimes called, prudential considerations.”

Austen's happiest couple I won't recap my entire article here, but I will add that an alternate or additional source of inspiration for Admiral Croft's sanguine attitude to matrimony might be that sailors apparently had the reputation for quick courtships in general. In an 1817 novel, Elizabeth, Her Lover and Husband, Captain Beverly marries in haste: “With the proverbial carelessness of a sailor, he married a widow lady, after having seen her three times at a place of public amusement…. This union was productive of but little happiness-contracted without any knowledge on his side of her character, habits, or pursuits, and on hers from pecuniary, or, as they are sometimes called, prudential considerations.” Of course, Admiral and Mrs. Croft's marriage worked out very well. They are an entirely devoted couple.

I had known that sailors had the reputation of spending their money quickly once they reached port, and some kept a girl in every port, but perhaps they also had a reputation for hasty marriages. If there is a specific proverb about sailors and carelessness, I don't know about it. Speaking of proverbs, Admiral Croft uses the expression: "breaking a head and giving a plaster," meaning to give someone an injury and then offer them a remedy for the injury. Plasters, plaisters, or poultices, were called "emplastrums" by doctors and apothecaries. These were topical mixtures which could be prepared at home and applied to various parts of the body. The best-known example is the mustard plaster for chest colds and coughs. In the TV series Tales from the Green Valley, domestic historian Ruth Goodman prepares a mustard plaster for her colleague Alex Langlands (at 20:00). She adds that most home remedies were merely placebos. "Mind you," she says, "one shouldn't underestimate the power of a placebo." Happy Holidays to all. Barring breaking news, Clutching My Pearls will resume in the New Year.

Published on December 16, 2021 00:00

December 5, 2021

CMP#78 "The Common Trash of Novels"

"As for the common trash of novels, under which the press has groaned, which have introduced so wretched a taste of reading, and have been so hurtful to young minds, particularly of the female sex, they are unworthy to be named, except in the way of censure."

"As for the common trash of novels, under which the press has groaned, which have introduced so wretched a taste of reading, and have been so hurtful to young minds, particularly of the female sex, they are unworthy to be named, except in the way of censure."-- The English Review, Or, An Abstract of English and Foreign Literature, Vol V, 1785 CMP#78 A Novel Satire from 1818

Catherine Morland engrossed in a novel When Jane Austen wrote in Northanger Abbey about book reviewers who "talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans," she wasn't exaggerating. Reviewers in periodicals and journals during this period often expressed their contempt for novels in exactly these terms.

Catherine Morland engrossed in a novel When Jane Austen wrote in Northanger Abbey about book reviewers who "talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans," she wasn't exaggerating. Reviewers in periodicals and journals during this period often expressed their contempt for novels in exactly these terms. Charles Robert Maturin was a writer of gothic novels. But he was also one of the critics who wrote dismissively of sentimental novels and the people who read them and wrote them.

“The path of novel-writing once laid open was imagined easy by all, and for about forty years the press was deluged with works to which we believe the literary history of no other country could produce a parallel. The milliner’s prentices who had expended their furtive hours, and drenched their maudlin fancies with tales of kneeling lords and ranting baronets at the feet of fair seamstresses, fair as they believed themselves to be, and in narrow back parlours as dark as their own, soon found it easy to stain the well-thumbed pages of a circulating library book with flimsy sentiments, and loose descriptions of their own..."

Just like Austen, Maturin wrote a pretty funny parody of this type of novel. Read on for more...

The Novel Reading, Josef Danhauser Austen famously defended the novel as "some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." She also wrote a satirical outline of sentimental novels, poking fun at the tropes of the genre. If you haven't read it, it's here.

The Novel Reading, Josef Danhauser Austen famously defended the novel as "some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." She also wrote a satirical outline of sentimental novels, poking fun at the tropes of the genre. If you haven't read it, it's here.Austen wrote her parody for private family amusement, but the above-quoted critic, Charles Robert Maturin, published an extended satire of sentimental novels, specifically the epistolary novel.

The entire satire is here, and I have excerpted most of it below.

“The heroine must be exquisitely, unimaginably beautiful, though two chapters are usually devoted to the description of her charms, or, as we should word it, “her transparent loveliness:” on the subject of her eyes being black or blue, we find nearly a division of authorities, and therefore do not dare to decide on a question of such delicate importance…

"She must be an orphan (if a foundling, so much the better), left mysteriously in the care of some opulent and noble family, who most unaccountably (considering their character for prudence) suffer her to board and lodge with them, and water her geraniums until the decisive age of sixteen, though conscious that the noble and enamoured heir of the family has been in love with her from their mutual cradles, which by a malicious contrivance of Cupid were placed next each other in the nursery.

"Now comes on the trying part of the business, the heroine is distracted by the ambition of the father, the pride of the mother, and the jealous insults of the sisters, not forgetting a snug misery of her own arising from the persecution of some desperate baronet, who, every night leaps the garden wall for the cold consolation of seeing the farthing candle twinkle in his mistress’s garret, where she weeps over the indignity of proposals urged by the steward’s nephew in the house, or the grocer’s heir in the village, to whom all the family…. are resolved on uniting her as a punishment for her presumption, and a security against their own disgrace. This supposed lover, this interloper in Cupid’s territories, must…. [have] a squint, and red hair, but in any case his legs must be bandy.

"Persecuted by love and hatred, she flies, flies over mountains without a stain on her white satin slippers, and is rumbled two hundred miles in a stage coach without a rent in her gossamer drapery. She must be run away with five or six times before she reaches the end of her journey (a trifling interruption, as she happens not to know where she is flying to), and it is on such occasions that she displays that extraordinary contrast of physical debility and mental independence, of fragility and hardihood, that constitutes the very essence of a novel heroine.

"Overturning carriage in front of Vienna," Anonymous “She is intoxicated with the smell of a lily, and faints at the murmurs of an Eolian harp, she melts in elegy over a dying linnet… [she] lies down in her clothes, which never require washing or mending, in spite of being made to do double duty, watches through the nights, and weeps through the day, without any diminution of the lustre of the eye…

"Overturning carriage in front of Vienna," Anonymous “She is intoxicated with the smell of a lily, and faints at the murmurs of an Eolian harp, she melts in elegy over a dying linnet… [she] lies down in her clothes, which never require washing or mending, in spite of being made to do double duty, watches through the nights, and weeps through the day, without any diminution of the lustre of the eye…"[A]nd after all this, she has resolution enough, though she never drew a trigger, to hold a loaded pistol to the head of her profligate seducer; to burst, scramble, and tear her way through casement, thicket, forest, and fence, to secure her retreat; and then, with the strength of a horse and the courage of a lion, to seat herself, without a sous in her pocket on the top of a stage-coach….

"When the vehicle breaks down (for this it must do) she can tramp in her silk stocking feet, and her whole wardrobe in a cambric handkerchief (that has never been washed but in her tears) straight up Piccadilly, and then new troubles begin: every gentleman she sees follows her, and, at last, sinking under the consciousness of beauty, misfortune, and wet feet, she trembles, totters, or glides into the back parlour of a shop in the Strand, to beg for a glass of water; for heroines at the last gasp must never take anything stronger; finds a congenial soul in the interesting face of the shopkeeper, who, with incredible liberality, offers her a gratuitous asylum (so like London shopkeepers) and, lovely and humble… she takes her station in a slip of a room where half the peerage crowd the shop every day to peep at her through a canvass blind.

The Lace Maker, Charles-Amable Lenoir "Here she maintains herself by her marvelous talents in embroidering or painting fan-sticks, the sale exceeding not only possibility, but even her utmost expectations….

The Lace Maker, Charles-Amable Lenoir "Here she maintains herself by her marvelous talents in embroidering or painting fan-sticks, the sale exceeding not only possibility, but even her utmost expectations…."At length, the interesting matron turns out a procuress in due form; and in spite of the industry and taste of the heroine (which by this time ought to have secured her a comfortable property in the three per cents) arrests her for board and lodging, or charges her with theft, drags her before a magistrate, and just as she is about to be fully committed... the magistrate ogling at her all the while, and is disappearing through one door, the hero enters through the other, clasps her to his bosom… swears that nothing shall divide them, and in proof of his asseveration draws his sword...

"[I]n the struggle, her wig or her handkerchief (we forget which) drops off, and her mole cinque-spotted, or strawberry-mark, or something equally conclusive or satisfactory, is discovered, by which she is proved to be a duke’s daughter or a peeress in her own right; her noble family in the same breath recognize her, and give their consent to her marriage; her disappointed lovers, one and all, pair off with the “sweet friends,” into whose sympathizing ears her epistolary sorrows have been poured through five volumes.

"The ten last pages are devoted to a description of the dress for the wedding; much honourable mention is made of white satin, and due notice of hartshorn…" I've been reading a lot of the literature of the long 18th century and I've enjoyed getting to know its tropes, improbabilities, and conventions myself, so I enjoyed Maturin's parody. I laughed when I read the part about the heroine watering her geraniums because Fanny Price has geraniums in the East Room! This satire appeared in the British Review and London Critical Journal (1818), and was quoted in The Oxford History of the Novel in English (2011). And yes, I've read 18th century novels which employ one or more of these tropes.

Although this is a satire, I think we can learn from it, because it is a distillation of dozens and dozens of novels. We recognize the theme of the heroine as damsel in distress who is buffeted about by fortune but maintains her dignity and of course her chastity. The theme of the orphan or foundling is also apparent. The friendless situation of Fanny Price in the great house at Mansfield is hardly unique in the literature of the long 18th century. The heroine gets her reward in the end and it means she no longer has to work for a living; her rank and status in society is confirmed and she marries her Prince Charming.

This is one reason why I am skeptical of feminist interpretations of--for example--Fanny Price in Mansfield Park. Why are modern scholars so certain that Fanny's relationship with the overbearing Sir Thomas must be an allegory of slavery? If Fanny is an allegorical enslaved person, then what about the literally hundreds of other heroines in similar straits? Are they also representative of chattel slavery? Or, are they variations on the standard Cinderella story? To quote from my Quillette article: Dependent, poverty-stricken relatives were ubiquitous in life and in novels, but Mansfield Park‘s Fanny Price is not just another poor English girl, she’s the “white counterpart” of a slave (an argument made by Moira Ferguson in an influential 1991 essay)... To take one of many examples, in a recent article, Sarah Marsh says when Sir Thomas tells Fanny to leave the ballroom with “the voice of absolute power,” Austen is reminding us of a “system that grants English enslavers absolute power over their human chattels.” Opinions in anti-racist discourse are evolving rapidly, so I suggest that anyone planning to compare white girls dancing at balls to enslaved Africans might want to think again. I think it's crucial to look at what Austen was doing with her plots and characters in comparison to other novels of her period, before drawing conclusions that she was doing something subversive or unique in terms of illustrating the injustices which beset dependent young females. I've banged on this drum before and will no doubt do it again! More blog posts about the dangers of reading novels, particularly romance novels, here and here . The Oxford History of the Novel in English attributes the essay I've quoted from to Charles Robert Maturin, (1780-1824) Maturin himself wrote gothic novels, so, like Austen, he could enjoy novels while laughing at them, I suppose. And he had a wife and four children to support.

Published on December 05, 2021 00:00

CMP#78 A Novel Satire

"As for the common trash of novels, under which the press has groaned, which have introduced so wretched a taste of reading, and have been so hurtful to young minds, particularly of the female sex, they are unworthy to be named, except in the way of censure."

"As for the common trash of novels, under which the press has groaned, which have introduced so wretched a taste of reading, and have been so hurtful to young minds, particularly of the female sex, they are unworthy to be named, except in the way of censure."-- The English Review, Or, An Abstract of English and Foreign Literature, Vol V, 1785 CMP#78 A Novel Satire from 1818

Catherine Morland engrossed in a novel When Jane Austen wrote in Northanger Abbey about book reviewers who "talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans," she wasn't exaggerating. Reviewers in periodicals and journals during this period often expressed their contempt for novels in exactly these terms.

Catherine Morland engrossed in a novel When Jane Austen wrote in Northanger Abbey about book reviewers who "talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans," she wasn't exaggerating. Reviewers in periodicals and journals during this period often expressed their contempt for novels in exactly these terms. Charles Robert Maturin was a writer of gothic novels. But he was also one of the critics who wrote dismissively of sentimental novels and the people who read them and wrote them.

“The path of novel-writing once laid open was imagined easy by all, and for about forty years the press was deluged with works to which we believe the literary history of no other country could produce a parallel. The milliner’s prentices who had expended their furtive hours, and drenched their maudlin fancies with tales of kneeling lords and ranting baronets at the feet of fair seamstresses, fair as they believed themselves to be, and in narrow back parlours as dark as their own, soon found it easy to stain the well-thumbed pages of a circulating library book with flimsy sentiments, and loose descriptions of their own..."

Just like Austen, Maturin wrote a pretty funny parody of this type of novel. Read on for more...

The Novel Reading, Josef Danhauser Austen famously defended the novel as "some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." She also wrote a satirical outline of sentimental novels, poking fun at the tropes of the genre. If you haven't read it, it's here.

The Novel Reading, Josef Danhauser Austen famously defended the novel as "some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language." She also wrote a satirical outline of sentimental novels, poking fun at the tropes of the genre. If you haven't read it, it's here.Austen wrote her parody for private family amusement, but the above-quoted critic, Charles Robert Maturin, published an extended satire of sentimental novels, specifically the epistolary novel.

The entire satire is here, and I have excerpted most of it below.

“The heroine must be exquisitely, unimaginably beautiful, though two chapters are usually devoted to the description of her charms, or, as we should word it, “her transparent loveliness:” on the subject of her eyes being black or blue, we find nearly a division of authorities, and therefore do not dare to decide on a question of such delicate importance…

"She must be an orphan (if a foundling, so much the better), left mysteriously in the care of some opulent and noble family, who most unaccountably (considering their character for prudence) suffer her to board and lodge with them, and water her geraniums until the decisive age of sixteen, though conscious that the noble and enamoured heir of the family has been in love with her from their mutual cradles, which by a malicious contrivance of Cupid were placed next each other in the nursery.

"Now comes on the trying part of the business, the heroine is distracted by the ambition of the father, the pride of the mother, and the jealous insults of the sisters, not forgetting a snug misery of her own arising from the persecution of some desperate baronet, who, every night leaps the garden wall for the cold consolation of seeing the farthing candle twinkle in his mistress’s garret, where she weeps over the indignity of proposals urged by the steward’s nephew in the house, or the grocer’s heir in the village, to whom all the family…. are resolved on uniting her as a punishment for her presumption, and a security against their own disgrace. This supposed lover, this interloper in Cupid’s territories, must…. [have] a squint, and red hair, but in any case his legs must be bandy.

"Persecuted by love and hatred, she flies, flies over mountains without a stain on her white satin slippers, and is rumbled two hundred miles in a stage coach without a rent in her gossamer drapery. She must be run away with five or six times before she reaches the end of her journey (a trifling interruption, as she happens not to know where she is flying to), and it is on such occasions that she displays that extraordinary contrast of physical debility and mental independence, of fragility and hardihood, that constitutes the very essence of a novel heroine.

"Overturning carriage in front of Vienna," Anonymous “She is intoxicated with the smell of a lily, and faints at the murmurs of an Eolian harp, she melts in elegy over a dying linnet… [she] lies down in her clothes, which never require washing or mending, in spite of being made to do double duty, watches through the nights, and weeps through the day, without any diminution of the lustre of the eye…

"Overturning carriage in front of Vienna," Anonymous “She is intoxicated with the smell of a lily, and faints at the murmurs of an Eolian harp, she melts in elegy over a dying linnet… [she] lies down in her clothes, which never require washing or mending, in spite of being made to do double duty, watches through the nights, and weeps through the day, without any diminution of the lustre of the eye…"[A]nd after all this, she has resolution enough, though she never drew a trigger, to hold a loaded pistol to the head of her profligate seducer; to burst, scramble, and tear her way through casement, thicket, forest, and fence, to secure her retreat; and then, with the strength of a horse and the courage of a lion, to seat herself, without a sous in her pocket on the top of a stage-coach….

"When the vehicle breaks down (for this it must do) she can tramp in her silk stocking feet, and her whole wardrobe in a cambric handkerchief (that has never been washed but in her tears) straight up Piccadilly, and then new troubles begin: every gentleman she sees follows her, and, at last, sinking under the consciousness of beauty, misfortune, and wet feet, she trembles, totters, or glides into the back parlour of a shop in the Strand, to beg for a glass of water; for heroines at the last gasp must never take anything stronger; finds a congenial soul in the interesting face of the shopkeeper, who, with incredible liberality, offers her a gratuitous asylum (so like London shopkeepers) and, lovely and humble… she takes her station in a slip of a room where half the peerage crowd the shop every day to peep at her through a canvass blind.

The Lace Maker, Charles-Amable Lenoir "Here she maintains herself by her marvelous talents in embroidering or painting fan-sticks, the sale exceeding not only possibility, but even her utmost expectations….

The Lace Maker, Charles-Amable Lenoir "Here she maintains herself by her marvelous talents in embroidering or painting fan-sticks, the sale exceeding not only possibility, but even her utmost expectations…."At length, the interesting matron turns out a procuress in due form; and in spite of the industry and taste of the heroine (which by this time ought to have secured her a comfortable property in the three per cents) arrests her for board and lodging, or charges her with theft, drags her before a magistrate, and just as she is about to be fully committed... the magistrate ogling at her all the while, and is disappearing through one door, the hero enters through the other, clasps her to his bosom… swears that nothing shall divide them, and in proof of his asseveration draws his sword...

"[I]n the struggle, her wig or her handkerchief (we forget which) drops off, and her mole cinque-spotted, or strawberry-mark, or something equally conclusive or satisfactory, is discovered, by which she is proved to be a duke’s daughter or a peeress in her own right; her noble family in the same breath recognize her, and give their consent to her marriage; her disappointed lovers, one and all, pair off with the “sweet friends,” into whose sympathizing ears her epistolary sorrows have been poured through five volumes.

"The ten last pages are devoted to a description of the dress for the wedding; much honourable mention is made of white satin, and due notice of hartshorn…" I've been reading a lot of the literature of the long 18th century and I've enjoyed getting to know its tropes, improbabilities, and conventions myself, so I enjoyed Maturin's parody. I laughed when I read the part about the heroine watering her geraniums because Fanny Price has geraniums in the East Room! This satire appeared in the British Review and London Critical Journal (1818), and was quoted in The Oxford History of the Novel in English (2011). And yes, I've read 18th century novels which employ one or more of these tropes.

Although this is a satire, I think we can learn from it, because it is a distillation of dozens and dozens of novels. We recognize the theme of the heroine as damsel in distress who is buffeted about by fortune but maintains her dignity and of course her chastity. The theme of the orphan or foundling is also apparent. The friendless situation of Fanny Price in the great house at Mansfield is hardly unique in the literature of the long 18th century. The heroine gets her reward in the end and it means she no longer has to work for a living; her rank and status in society is confirmed and she marries her Prince Charming.

This is one reason why I am skeptical of feminist interpretations of--for example--Fanny Price in Mansfield Park. Why are modern scholars so certain that Fanny's relationship with the overbearing Sir Thomas must be an allegory of slavery? If Fanny is an allegorical enslaved person, then what about the literally hundreds of other heroines in similar straits? Are they also representative of chattel slavery? Or, are they variations on the standard Cinderella story? To quote from my Quillette article: Dependent, poverty-stricken relatives were ubiquitous in life and in novels, but Mansfield Park‘s Fanny Price is not just another poor English girl, she’s the “white counterpart” of a slave (an argument made by Moira Ferguson in an influential 1991 essay)... To take one of many examples, in a recent article, Sarah Marsh says when Sir Thomas tells Fanny to leave the ballroom with “the voice of absolute power,” Austen is reminding us of a “system that grants English enslavers absolute power over their human chattels.” Opinions in anti-racist discourse are evolving rapidly, so I suggest that anyone planning to compare white girls dancing at balls to enslaved Africans might want to think again. I think it's crucial to look at what Austen was doing with her plots and characters in comparison to other novels of her period, before drawing conclusions that she was doing something subversive or unique in terms of illustrating the injustices which beset dependent young females. I've banged on this drum before and will no doubt do it again! More blog posts about the dangers of reading novels, particularly romance novels, here and here . The Oxford History of the Novel in English attributes the essay I've quoted from to Charles Robert Maturin, (1780-1824) Maturin himself wrote gothic novels, so, like Austen, he could enjoy novels while laughing at them, I suppose. And he had a wife and four children to support.

Published on December 05, 2021 00:00

November 28, 2021

CMP#77 Book Review: A Winter in London

This post continues my exploration of the literature of Jane Austen's contemporaries. Here's another long 18th century book review, this time for a "novel of fashion." CMP#77 A WINTER IN LONDON -- Three Genres in One

This post continues my exploration of the literature of Jane Austen's contemporaries. Here's another long 18th century book review, this time for a "novel of fashion." CMP#77 A WINTER IN LONDON -- Three Genres in One

A Winter in London (1806) by Thomas Skinner Surr is a peculiar blend of a novel, with a melodramatic quasi-gothic plot awkwardly rubbing shoulders with celebrity gossip and social criticism. By quasi-gothic, I mean that there is nothing supernatural in the plot, but there is treachery, a villainous foreigner, anti-clericalism, titillating hints of incest narrowly averted, and a dungeon or two. The young hero, Edward Montagu, is a foundling.

A Winter in London (1806) by Thomas Skinner Surr is a peculiar blend of a novel, with a melodramatic quasi-gothic plot awkwardly rubbing shoulders with celebrity gossip and social criticism. By quasi-gothic, I mean that there is nothing supernatural in the plot, but there is treachery, a villainous foreigner, anti-clericalism, titillating hints of incest narrowly averted, and a dungeon or two. The young hero, Edward Montagu, is a foundling.The handy thing about a Georgian-era foundling narrative is that you can show the foundling as a plucky and virtuous character struggling to find their way in a society based on birth and rank rather than merit, but, in the Big Reveal of True Parentage, you can explain that the foundling IS of good birth! Their good looks, excellent character and intelligence had to come from somewhere, after all.

Are novels about foundlings an attempt to subvert the social order, or does the Big Reveal reinforce the social order? Is this a way of having your cake and eating it too?

Tom Jones, the foundling in Fielding’s 1749 novel, is of illegitimate birth but other foundlings such as Edward Evilen (1796) or Rosalie in the Mystic Cottager of Chamouny (1795) and Edward Montague of A Winter in London all have married parents who have been separated through some combination of bad luck and perfidy. The Big Reveal comes about as a result of amazing coincidence: the lovely Rosalie strums her guitar in the Swiss Alps until the one person in the world she wasn't supposed to meet seeks lodging in her remote cottage. Edward Montagu is raised in a cottage within sight of his true ancestral home. He accidentally meets his father--who wrongly thinks his wife, Edward's mother, was unfaithful to him--while they are both roaming moodily around the neighbourhood. “'I-I, your father!' said the stranger, breaking from the arms of Edward, which entwined his knees. 'No—poor wretch! Thou art the fruit of crime, the offspring of adultery! Thou hast no parents; for thy guilty mother and her paramour, thy father, perished in that hour when thou wast rescued from destruction.'”

[At this horrible news], "Edward, relinquishing his hold, fell prostrate on the earth… the mysterious stranger, with a wild shriek of despair, smiting his forehead, exclaimed, 'Where, where shall I fly to escape from misery!' and in a moment he was out of sight.” More high drama ensues before everything and everyone is sorted out, and Dad continues to use the gothic convention of using “thou” and “wast” instead of “you” and “were” in moments of high emotion. As for the hint of incest I mentioned, I've come across several foundling novels in which the young man falls in love with a beautiful girl, and it appears for a time that she must really be his sister or half-sister, but she isn't. I had no idea that so many writers teased their readers with incestuous love. In her guide to gothic novels , Ann B. Tracy's index has many entries for incest. These entries distinguish between "Incest: Actual" and "Incest: Literary Flirtation with, including false alarms, foiled attempts, threats, and unconsummated incestuous passion."

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire in costume, by Maria Cosway

Decadent London, tsk, tsk, tsk

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire in costume, by Maria Cosway

Decadent London, tsk, tsk, tsk

The title, A Winter in London, does not refer to the gothic-y foundling plot but to a separate and major theme of the novel: the vapid, dissolute world of the London ton in which everybody is absolutely miserable, caught in a vortex of dissipation and consumed with envy of those higher on the social ladder than themselves. The London-based characters are gossiping, quarrelsome, and extravagant, partying at night and sleeping during the day, running up gambling debts, ignoring the bill-collectors pounding on their doors, etc., etc. This genre of novel is called "novel of fashion," or a novel of fashionable life.

Surr’s leading exemplar of this decadent lifestyle the Duchess of Belgrave, a character said to be based upon Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. The duchess died not long after the book came out, and some said she was hastened to her grave because of Surr's satirical portrait. Another minor character is a thinly-veiled portrait of successful society physician, Sir Walter Farquhar.

Just as foundlings are both a rebuke and a reinforcement of the class system, so Surr criticizes London society while at the same time providing his readers with enticing descriptions of the lifestyles of the rich and famous. He gives a lengthy description of a lavish masked ball, with “superb” decorations and costumes.

“Passing through this apartment [fitted up to look like a Moorish palace], the visitor next entered a long gallery, which was formed into an Egyptian temple, the effect of which was truly grand and striking…” The branches of the “artificial cypress trees” wave about thanks to “invisible machinery, and thus appeared to be really agitated by the air.”

A pavilion is erected in an indoor garden “built in the rotunda form; the roof was supported by pillars of gold studded with precious stones, around which were entwined wreaths of variegated lamps; from the centre of the dome, which was painted in a masterly style, with the luxuriant representation of every species of oriental fruit, foliage, and flowers, was suspended a superb chandelier, and beneath its trembling splendour, a fountain of curious workmanship played rose-water into golden vases.”

The Duchess of Belgrave attends, dressed as Diana. Our hero Edward looks fetching in tights, and our heroine Emily is a Moorish princess. But as Surr's readers well knew, if you throw a lavish masked ball, you are just asking for trouble. I'll have to do a post in the future about the many plot complications that arise during masked balls.

Posterity has not been so kind to the Prince Regent. The Prince of Wales makes several appearances in the novel, including the masked ball. Surr has nothing but great things to say about the future George IV. “The elegant deportment, the graceful manners, the noble mien, and the refined wit, of the most accomplished prince in Europe, were not to be concealed beneath the guise of a Spanish grandee. His royal highness was soon discovered, and wherever he bent his steps, there was the point of attraction.”

Posterity has not been so kind to the Prince Regent. The Prince of Wales makes several appearances in the novel, including the masked ball. Surr has nothing but great things to say about the future George IV. “The elegant deportment, the graceful manners, the noble mien, and the refined wit, of the most accomplished prince in Europe, were not to be concealed beneath the guise of a Spanish grandee. His royal highness was soon discovered, and wherever he bent his steps, there was the point of attraction.”The prince is even shown behaving heroically when the inevitable trouble arises at the ball. Signor Belloni, an evil scheming Italian, stalks our hero Edward. The fair heroine Emily pleads for someone to intervene: "I am sure there is danger of some kind!" The prince responds to her plea “with a gallantry that put the rest of the gentlemen to the blush... His example was electric. Every gentlemen was then ready to rush forth after Edward” who, they discover, has been stabbed in the breast by a poniard. It was definitely the Italian, then. Emily loses no time in doing her part: she "utters a loud shriek," and faints dead away. Thus concludes Volume II.

Grub Street, home of aspiring hack writers in London

Characters who editorialize

Grub Street, home of aspiring hack writers in London

Characters who editorialize

In addition to the foundling plot and the “London is a sinkhole of vice” theme, the third thread in this novel is eclectic commentary on the social issues of the day. These dialogues are mostly carried on between wise old Dr. Hoare, who is tutor to a feckless young nobleman, and his old friend, Mr. Ogilvy, with Edward sometimes chiming in. For me, this was the most interesting aspect of the novel.

These conversation cover a broad array of issues. but not colonialism or slavery. The story opens with the shipwreck of an East India trading ship, but this is merely a plot device to introduce the shipwrecked foundling, who is brought ashore by a Chinese man who cannot speak English and who promptly dies.

As for slavery, what could be more neutral or oblique than this passive voice passage: “unhappily a dispute arose among some of the leading men in power, relative to our colonial settlements in the West Indies. Several pamphlets were published on the occasion. Among others my nephew Charles wrote one in defense of the opinions espoused by his patron, which were also honestly his own.”

The key point in this inserted tale isn't the West Indies; the story is an opportunity for Surr to vent his spleen against book reviewers. Poor Charles is crushed when he receives a very personal and sarcastic review. Mr. Ogilvy goes to the editorial office and rebukes the reviewer at length: "No, sir, it was reserved for the present day to bring forth a fry of young critic imps, the mingled spawn of arrogance and envy hatched by mischief, who were to entail disgrace for ever on the word reviewer, by making it synonymous with libeller and assassin.... You may proceed in your career… grin over the collection of hopes destroyed, of fortunes injured, of feelings outraged, of intellects deranged, of hearts broken by your merry malice, or your venomous corruption; enjoy the feast infernal!”"

Snarky book reviewers are just one of the issues which appear to exercise Surr more than colonialism or slavery. He also has opinions about the theatre and prison reform.

Snarky book reviewers are just one of the issues which appear to exercise Surr more than colonialism or slavery. He also has opinions about the theatre and prison reform.Dr. Hoare’s friend Mr. Ogilvy criticizes the European custom of having soldiers stationed inside theaters. Better, says Mr. Ogilvy,” that we should be pelted now and then with the rind of an orange, than that our lives should be exposed to the malice or mistake of some hot headed grenadier; --better too that we are occasionally a little incommoded by noise, than that the rude or even riotous jollity of British freedom should be changed to the servile silence or effeminate decency of an enslaved people.”

Female education is also discussed: “I don’t approve of the present system, of making prattling philosophers in petticoats.” [says Mr. Ogilvy] I see no good that is to result to society from having our wives or daughters discharging electric or Galvanic batteries at our heads, or of converting our cookmaids into chemical analysers of smoke and steam.”

“But are not the scientific pursuits of the present day at least as beneficial to society as the old amusements of working carpets and chair bottoms?” doctor Hoare asks, but he is just kidding. He concurs that “it is impossible there should be a difference of opinion” on the subject of females studying the sciences.

Surr is bullish on England and believes it is superior to other countries in terms of social mobility and equality.

“If in one coach you see the family of a duke who have inherited without labour the estates of their ancestors,” Dr. Hoare enthuses, “the very next that follows it will, in all probability, be that of some industrious and fortunate trader, whose splendour, instead of discouraging, animates the spectators, as an emblem of the reward which in this free country is held out, without exception, to the industrious and the enterprising.” (Again, Surr has it both ways when it comes to social mobility. One of the characters is a waiter who works hard, saves money and rises up the world, but he's presented as a sort of scheming, grasping, undereducated skinflint. His son marries the beautiful daughter of a noble family that's fallen on hard times but it's not a love match. There's an ambivalence about the whole thing.)

Surr also counteracts his earlier descriptions of London opulence by having Edward's father, the long-lost duke, inveigh against the heartlessness of the wealthy: “Ah, how many children of misery and woe might the affluent, the skillful, and the powerful rescue from the pallet of disease, the chains of madness, or the debtor’s den, with but a thousandth part of the useless energy wasted in pleasure’s toils!” Topics and Topicality

The Critical Review noted that A Winter in London was in “great demand” at the “circulating libraries,” but called the story “trite,” and filled with clichés. “The little that is not common-place, is improbable.” As for the editorial commentary, the reviewer notes that the sad tale of the young writer who goes mad when his pamphlet gets a snarky review “is introduced abruptly and without having any connection with the story.”

The Monthly Review said of the gothic plot: “Will the Italians ever revenge, or ever redeem, the stigma which our writers almost constantly throw on them, when an individual of that nation has a part to act in the drama?”

Georgiana, Duchess of Cavendish, by Anne Foldsone Mee I think it was Surr's portraits of real people and the descriptions of London opulence—not the gothic plot and not the topical conversations—which explains why A Winter in London went into at least 13 editions when it came out. (In contrast, only one of Austen’s novels--Mansfield Park--had a second edition and she lost money on when it failed to sell). The topicality of A Winter in London made it popular in its time, but of course this is what makes it seem dated today.

Georgiana, Duchess of Cavendish, by Anne Foldsone Mee I think it was Surr's portraits of real people and the descriptions of London opulence—not the gothic plot and not the topical conversations—which explains why A Winter in London went into at least 13 editions when it came out. (In contrast, only one of Austen’s novels--Mansfield Park--had a second edition and she lost money on when it failed to sell). The topicality of A Winter in London made it popular in its time, but of course this is what makes it seem dated today.While A Winter in London has since fallen into obscurity, one of its characters casts her eye upon posterity. The imitation Duchess of Devonshire character, the Duchess of Belgrave, writes to her sister: “I hope you have carefully preserved the numerous epistles I have written you… it is impossible to estimate how large a fortune they may produce to your posterity in the year of our Lord two thousand and odd… [but] be careful in concealing them at present, lest they should fall into the [wrong] hands before the two hundred years I allude to have rolled over my grave…”

Just as I like dipping into the past, I like the thought of the people of the past thinking about the year "two thousand and odd."

Edward recovers from his stab wound, by the way, and the errors and tragedies of the past are all cleared up. He has the bluest of blue blood, which is more than can be said for Emily, since her dad is nouveaux riche. There is one last-minute further misunderstanding between Edward and Emily, but when that's dealt with, they live happily and wealthily ever after.

The Wiley Online Library says Thomas Skinner Surr (1770–1847) is "perhaps the most famous author of novels of 'fashionable life'." "[H]his work was a touchstone for debates about the moral and cultural worth of novels." That might explain why he inserted the unrelated debates about the issues of the day; to give his novels additional moral gravitas.

The Wiley Online Library says Thomas Skinner Surr (1770–1847) is "perhaps the most famous author of novels of 'fashionable life'." "[H]his work was a touchstone for debates about the moral and cultural worth of novels." That might explain why he inserted the unrelated debates about the issues of the day; to give his novels additional moral gravitas. In addition to novels, Surr wrote books on the subject of banking. He worked as a clerk in a London bank. His novels sold well but it looks like he kept his day job. His father was a wheelwright and a grocer and his mother was the daughter of a mayor of London, which explains why his name includes his mother's maiden name of "Skinner." He was therefore from the merchant class and never rose to the ranks of the people that he wrote about.

The website: UK Red: The Experience of Reading in England , captures remarks from everyday people from 1940 to 1945, culled from their letters and diaries and other records. Here is the entry for A Winter in London

Published on November 28, 2021 00:00

November 22, 2021

CMP#76: A Guide to Gothic Novels

Nobody is entirely safe; nothing is secure. The Gothic world is quintessentially the fallen world, the vision of fallen man, living in fear and alienation, haunted by images of his mythic expulsion, by its repercussions, and by an awareness of his unavoidable wretchedness.

Nobody is entirely safe; nothing is secure. The Gothic world is quintessentially the fallen world, the vision of fallen man, living in fear and alienation, haunted by images of his mythic expulsion, by its repercussions, and by an awareness of his unavoidable wretchedness.-- from Ann B. Tracy's introduction

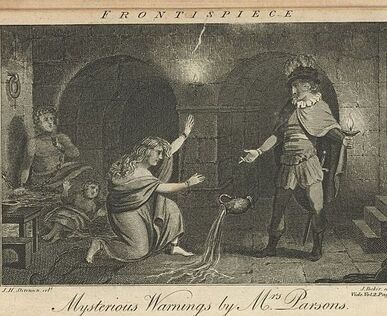

Book Review: The Gothic Novel 1790–1830: Plot Summaries and Index to Motifs “I will read you their names directly; here they are, in my pocketbook." [says Isabelle Thorpe to Catherine Morland] "Castle of Wolfenbach, Clermont, Mysterious Warnings, Necromancer of the Black Forest, Midnight Bell, Orphan of the Rhine, and Horrid Mysteries. Those will last us some time.”

“Yes, pretty well," [answers Catherine] "but are they all horrid, are you sure they are all horrid?”

Isabella and Catherine are binge-reading gothic novels in Bath, a popular pastime when Jane Austen wrote her first draft of Northanger Abbey. Because of the long delay before its actual publication in 1817, Austen felt compelled to note in her foreword that "thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes."

Isabella and Catherine are binge-reading gothic novels in Bath, a popular pastime when Jane Austen wrote her first draft of Northanger Abbey. Because of the long delay before its actual publication in 1817, Austen felt compelled to note in her foreword that "thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes."A hundred years later, Isabella Popp tells us , Isabella's seven horrid novels had fallen into such obscurity that they "were often presumed to be invented by Austen." In 1927, "Michael Sadleir, a British publisher, novelist, and book collector, located copies of all seven novels." The last one to surface was Orphans of the Rhine.

This should be a reminder to us that prior to our digital age, finding copies of rare old book was a much more difficult and expensive challenge. Thanks to the internet and thanks to digitization, hundreds of these spine-chilling 18th-century novels are readily available, either for purchase or through your local university or community library.

You can also dive into the world of the gothic novel thanks to Professor Ann B. Tracy and her reference book: The Gothic Novel 1790-1830: Plot Summaries and Index to Motifs.

Tracy's introduction is written in clear and engaging prose, not obtuse academic-speak. She expands on the religious underpinnings of the gothic, seeing it as a "fallen world" in which man is "haunted by images of his mythic expulsion." For that reason, I would have expected to see a reference to the anti-Catholicism which pervades so many of these novels. The index has entries and sub-entries for "abbess, bad" and "monk, unusually mysterious," as well as entries and sub-entries for monasteries.

Tracy's introduction is written in clear and engaging prose, not obtuse academic-speak. She expands on the religious underpinnings of the gothic, seeing it as a "fallen world" in which man is "haunted by images of his mythic expulsion." For that reason, I would have expected to see a reference to the anti-Catholicism which pervades so many of these novels. The index has entries and sub-entries for "abbess, bad" and "monk, unusually mysterious," as well as entries and sub-entries for monasteries.Gothic novels are also part travelogue, with depictions of Italian scenery that most readers of the time could not expect to ever visit themselves, and most of the authors of the novels never saw at first-hand, either. "[T]he one place the protagonist almost never finds himself is at home," explains Tracy.

"Do not imagine that you can cope with me in a knowledge of Julias and Louisas," Henry Tilney says to Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey. Nor could anyone compete with Tracy's knowledge of gothic heroines; she provides an index for the Julias and Louisas, and for the heroes too. All seven of the "horrid" novels which Isabella recommended to Catherine are summarized in this volume and many more besides.

For fun, let's check out one of the openings of Isabella's horrid novels at random from Tracy's guide: here is The Mysterious Warning, by Eliza Parsons, which deals with two well-born brothers by two different mothers.

"As the novel begins, the boys, now grown, are very different from each other; briefly, Rhodophil is bad, Ferdinand good. But Rhodophil is so accomplished a hypocrite that Ferdinand fails to see through his displays of fraternal affection. When Claudina, whom they both fancy, chooses and marries Ferdinand, Rhodophil makes a show of soliciting his father’s pardon for Ferdinand’s unprofitable match. In fact, he manages to keep the two from reconciliation and causes Ferdinand to miss a deathbed blessing. Further, he hides the latest will and magnanimously buys Ferdinand a commission in the army. This enables him to keep and seduce his sister-in-law.

"As the novel begins, the boys, now grown, are very different from each other; briefly, Rhodophil is bad, Ferdinand good. But Rhodophil is so accomplished a hypocrite that Ferdinand fails to see through his displays of fraternal affection. When Claudina, whom they both fancy, chooses and marries Ferdinand, Rhodophil makes a show of soliciting his father’s pardon for Ferdinand’s unprofitable match. In fact, he manages to keep the two from reconciliation and causes Ferdinand to miss a deathbed blessing. Further, he hides the latest will and magnanimously buys Ferdinand a commission in the army. This enables him to keep and seduce his sister-in-law. "When Ferdinand comes home on leave, a mysterious voice (belonging to Ernest the discerning servant) tells him to flee Claudina as he would sin and death. She agrees that this warning is justified and goes to a convent without letting Ferdinand know where.

"In the course of subsequent melancholy wandering, Ferdinand finds and rescues a couple who for twelve years have been locked in separate dungeons by a sadistic recluse. The male victim, Count M--, becomes Ferdinand’s companion after his wife decides to go into a convent. They meet two girls, one of whom (Louisa) has been victimized by wicked Count Wolfran, who married, discarded, denied, and imprisoned her...."

This reference guide to the gothic novels of yesteryear is not necessarily a book you'd read cover-to-cover. It's fun to dip into here and there, to enjoy the plot summaries and especially to read over the index to motifs. Tracy has built a comprehensive index of popular gothic tropes which have a fun, tongue-in-cheek quality. The entry for "skeleton" for example, includes sub-entries for:

This reference guide to the gothic novels of yesteryear is not necessarily a book you'd read cover-to-cover. It's fun to dip into here and there, to enjoy the plot summaries and especially to read over the index to motifs. Tracy has built a comprehensive index of popular gothic tropes which have a fun, tongue-in-cheek quality. The entry for "skeleton" for example, includes sub-entries for:"skeleton, animated; at banquet; in bed with; in closet; costumed; in dungeon; hand of, clutching murder weapon; hanging; in quantity; spectral; in trunk; wearing familiar ring."

I am going to check out the novels listed under "novels, reading, dangers of," to find more examples of those authors who, as Jane Austen complained, degrade "by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding." More on the dangers of novel-reading here. As Professor John Mullan points out in this lecture, the Scooby Doo plot, in which the supernatural threat turns out to be a contrivance of the villain, is a direct descendant of Ann Radcliffe's gothic novels. ("And I would have gotten away with it too, if it weren't for you pesky kids!")

In A Marriage of Attachment, my second novel of the Mansfield Trilogy, Fanny Price is alone in an empty warehouse at night and is spooked by thoughts of the Ratcliffe Highway murderer, who is at large in London. Click here for more about my books.

Published on November 22, 2021 00:00

November 15, 2021

CMP#75: The Perils of Petticoat Government

Austen scholars: “Austen’s novels are preoccupied with class and wealth in England!”

Austen scholars: “Austen’s novels are preoccupied with class and wealth in England!”Silver Fork novelists: “Hold my beer.” Book Review: Mrs. Armytage, or, Female Domination, by Catherine Gore

Formidable dowager (A portrait of Victorian art expert Mary Doyle, not Mrs. Armytage, but you get the idea) Mrs. Armytage (1831) by Catherine Gore is a three-volume novel of the “Silver Fork” school, meaning that it's a novel set in the upper echelons of English society and it follows the lifestyles of the rich and titled. Actually, Gore’s descriptions of country estate life, racing meets, carriages, and sprightly, cynical conversation are the least interesting parts of this story: the chief interest arises out of a clash of conflicting personalities. This is very much a character-driven novel.

Formidable dowager (A portrait of Victorian art expert Mary Doyle, not Mrs. Armytage, but you get the idea) Mrs. Armytage (1831) by Catherine Gore is a three-volume novel of the “Silver Fork” school, meaning that it's a novel set in the upper echelons of English society and it follows the lifestyles of the rich and titled. Actually, Gore’s descriptions of country estate life, racing meets, carriages, and sprightly, cynical conversation are the least interesting parts of this story: the chief interest arises out of a clash of conflicting personalities. This is very much a character-driven novel.“There is something, perhaps, of Jane Austen’s influence to be traced in the novels of Catherine Grace Gore,” says the 1915 edition of the Cambridge History of English Literature. Yes, Gore has collected together her three or four families in a country village, except for the fact that the families are of higher rank and wealth than is to be found in Austen.

We have Mrs. Armytage, a Yorkshire widow who has the full control of her late father’s and late husband’s lands and wealth. She is an assiduous manager of her property, a competent landlord, and benevolent patroness of many charities, but she is proud, controlling, and inflexible.

Her son and heir Arthur is good-natured but thoughtless. He makes an impulsive marriage to a pretty girl from a much lower social class, which creates a breach between himself and his mother, especially when the new bride's vulgar relatives show up uninvited. Add to the mix an envious gossiping neighbour, and you have a slow-motion train wreck which I found pretty engrossing for the first two-thirds of the novel.

Read on to spot the hints of Austen to be found in Mrs. Armytage:

Rosamund is the namesake of the Fair Rosamund of legend Petticoat Government

Rosamund is the namesake of the Fair Rosamund of legend Petticoat GovernmentJust as with Austen, (and scads of other novelists) we have critical, satirical portraits of the upper class. Just as with Austen, we see people who live up to the responsibilities of their rank and position, and others who do not. Mrs. Armytage is an upholder of the traditional values of the squirearchy. She has no use for the Duchess of Spalding, a maneuvering socialite whose daughters are in the mold of Miss Bingley. The decadent Spaldings are set against the upright Duke of Rotheram and his family and the rustic, old-fashioned Maranham sisters, each of whom represents a different caricature of spinsterhood: the Amazon, the female pedant , and the invalid. But the time we spend with the Spaldings at Spalding castle dragged for me: especially the vapid conversations of the foppish Spalding son and the other houseguests.

The Maranham spinsters have a mysterious and beautiful ward living with them. A veil of mystery hangs over the lovely Rosamund Devenport's parentage. Her beauty and simplicity enchants the foppish son of the Duke of Spalding. He comes a-courting, but it’s not easy to get past the three spinsters. Over lunch, the oldest sister testily informs him: “We do not boast, like your mother, the Duchess, six acres of glass in our garden… (but) we can produce an apricot worth eating. The overgrown, washy things your famous Horticultural Societies are poisoning the country with, appear to my palate little better than pumpkins…”

The subtitle of the book, after all, is Female Domination, and it is clear that female domination is not a good thing. Mrs. Armytage’s son and daughter are adults, but they are treated like children. The Duchess of Spaulding dominates her husband to such an extent that he withdraws from family life, like Mr. Bennet but without the humour. He only takes a part in the narrative when his son asks him to bless his marriage with Rosamund Devenport, the girl of unknown parentage. The Duke’s “pride and prejudices” forbids the match until Rosamund's dramatic backstory is finally explained.

Mrs. Armytage’s gentle daughter Sophia and a deserving young man (kept offstage until the end of the novel) are another ill-starred couple, but they don't get a happy ending. Sophia’s suitor doesn’t have enough money to propose marriage. Sophia is doomed to suffer “disappointed hopes” and “blighted affections.” The kindly old vicar, Dr. Grant, consoles and supports her.

Marian's father is a loud and vulgar racing fan Social Critique?

Marian's father is a loud and vulgar racing fan Social Critique?So is this novel a critique of the snobbery of the upper classes and the stultifying restrictions of society? Not unequivocally. Just as with Austen, we also have scathing portraits of social climbers, people from the lower ranks who only want to be accepted by the upper ranks. They are not presented as sympathetic figures merely by virtue of being from the middling classes. Marian, the daughter-in-law Mrs. Armytage deplores, has an uncle who is a West Indian planter and another relative who is a Bristol merchant. Both of these characters represent the type of nouveaux riches vulgarity that makes Mrs. Armytage shiver.

There is also a rich planter from the Southern United States who comes for a visit and becomes enamored with the idea of marrying into the nobility, although he is so unaccustomed to life in English country-houses that he mistakes a duke for an upper servant.

There are some comic touches but overall, the tone of Mrs. Armytage is darker and a little more didactic than Austen.

I thought the surprise visit of Marian's father to Mrs. Armytage's manor was a masterpiece of psychological realism, and I liked the portrayal of her household of ancient servants who shuffle slowly along through the corridors of the stately home while registering their approval or disapproval of events. Psychological Drama (and spoiler alert)

A contemporary reviewer said of Catherine Gore: "[She delineates] with truth and delicacy, those lighter shades of character by which society is checquered. In her fine appreciation of character, we are reminded of Miss Austen."

What I admired about the first two volumes of Mrs. Armytage was the fact that we saw flawed human beings contending with a difficult situation. The title character has her flaws, but so does her son Arthur. He is a coward who uses his sister Sophia to bear the brunt of parental displeasure. Instead of escorting his new wife to present her to his mother, Arthur sends Marian all by herself, to introduce herself, while he lingers behind in the village. Then, having obtained this wife, with whom he was so infatuated during their courtship, he leaves her to live with her formidable mother-in-law for weeks and months at a time.

But after the character-driven action of the first two volumes, Gore resorted to melodrama to wind up her storylines. Mrs. Armytage goes from being domineering to being insanely unreasonable. A rich uncle appears out of nowhere to leave his fortune to the Sophia's deserving young man; he writes to ask for her hand but Mrs. Armytage destroys the letter. Broken-hearted Sophia dies of Wasting Victorian Heroine Disease (aka consumption). Then Mrs. Armytage is so eager to publicly condemn her daughter-in-law for a perceived indiscretion (of which she is innocent) that she is deaf to the voice of reason.

A last will and testament comes to light which overthrows Mrs. Armytage's entire world; she flees to the continent. Her son and her daughter-in-law suddenly become highly-principled and unselfish. They go searching for her and find her dying in Italy. Arthur and Marian arrive unexpectedly at her villa in the middle of the night. Mrs. Armytage fears that she is going to die in a home invasion: “With hasty steps, the intruders traversed the floor, and approached her; while, overcome by weakness, she sank into a chair under the expectation of an assailing arm—perhaps a mortal blow! A single humble and heartfelt ejaculation to Heaven avowed her apprehensions and her resignation.

“But the arm that encircled her was no hostile arm—the sobs that reached her ear burst from no alien bosom. It was her son—her afflicted son—who was hanging over her! It was Marian who was kneeling at her feet!

“‘Will you receive us?—will you accept us!’ -–faltered Arthur, again embracing her.

“A kiss imprinted on his clasped hands, and the burning tears that fell upon them, silently avouched the repentance and the renewed affections of his mother!” After this climax of filial devotion, Gore wraps up her story swiftly. Mrs. Armytage dies in the bosom of her family, and Arthur and Marian become excellent proprietors of the estate and beloved patrons of their community.

Catherine Gore (1798 – 1861) Catherine Grace Frances Gore was the daughter of a wine merchant; in other words, like most silver fork novelists, she came from the middle classes, not the gentry.