Lona Manning's Blog, page 22

May 2, 2021

CMP#44 Stock Characters: Fops and Fools

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. Stock Characters of the 18th Century: There to be laughed at

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. Stock Characters of the 18th Century: There to be laughed at

Jane Austen paints Persuasion's Sir Walter Elliot as a dim-witted snob. Throughout the novel, he is obsessed with rank and his own handsome appearance. The Royal Navy is Britain's most potent symbol, but Sir Walter doesn’t care about national identity or the defense of his country when he tells his attorney Mr. Shepherd: “I have two strong grounds of objection to [the Navy]. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and secondly, as it cuts up a man's youth and vigour most horribly... A man is in greater danger in the navy of being insulted by the rise of one whose father, his father might have disdained to speak to, and of becoming prematurely an object of disgust himself, than in any other line.”

Jane Austen paints Persuasion's Sir Walter Elliot as a dim-witted snob. Throughout the novel, he is obsessed with rank and his own handsome appearance. The Royal Navy is Britain's most potent symbol, but Sir Walter doesn’t care about national identity or the defense of his country when he tells his attorney Mr. Shepherd: “I have two strong grounds of objection to [the Navy]. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and secondly, as it cuts up a man's youth and vigour most horribly... A man is in greater danger in the navy of being insulted by the rise of one whose father, his father might have disdained to speak to, and of becoming prematurely an object of disgust himself, than in any other line.”If we were to view Austen’s depiction of Sir Walter in isolation, if we were to look at this caricature independently of the other characters in the book -- and independently of other novels of the period -- we might conclude that Austen is making a larger point about class distinctions in her time. Is she a secret radical?

However, what have we here? What about Mr. Shepherd? Is he portrayed as an educated, self-made man heroically counterpoised against the decadent aristocrat? Not really. The attorney is drawn in subtler terms, but Austen still skewers him. Mr. Shepherd is a flattering, obsequious subordinate: I venture to hint… what I would take leave to suggest is… And I love the quiet touch of: “Mr. Shepherd laughed, as he knew he must, at this wit, and then added—"I presume to observe…”

Sir Walter and Mr. Shepherd are balanced against each other – the former is a snob and the latter is a toady. And what of Mr. Shepherd’s daughter, Mrs. Clay? If Austen has egalitarian impulses, then why does she portray Mrs. Clay as an upstart, a social-climbing gold-digger? And have we forgotten that she throws some serious shade on social climbing ladies who betray themselves through their lack of breeding?

The giddy Mrs. Palmer As I mentioned in a previous post, literary scholars call Jane Austen’s brand of satire “Horatian satire:” “Horatian satire is a gentler form of derision that is motivated more towards amusing the audience, as opposed to repulsing them.”

The giddy Mrs. Palmer As I mentioned in a previous post, literary scholars call Jane Austen’s brand of satire “Horatian satire:” “Horatian satire is a gentler form of derision that is motivated more towards amusing the audience, as opposed to repulsing them.” They are all ridiculous in their own way; Mrs. Clay with her insinuating flattery, Mr. Shepherd with his unctuous servility, and Sir Walter, with his colossal self-regard. Anne Elliot is surrounded, as author Robert Rodi puts it, by an assortment of "grotesques," and she is the only adult in the room. If Austen finds humor in vulgar people, social climbers, and high-born people, then perhaps she isn't making a radical social point so much as amusing herself and her readers.

I’m even more convinced that Austen was poking fun after reading the novels of some of her contemporaries. 18th-century novels tend to feature an assortment of mockable people–- vain young ladies, selfish, spendthrift aristocrats, social-climbing mamas, and of course, the French. There was nothing subtle about these portrayals. These are stock characters. They are also static characters, a literary term for a character who doesn't grow or change during the course of the novel.

With a lack of subtlety which abounds in 18th century novels, these characters are introduced as though the author was wheeling them onstage with a hand-truck, and announcing what they are: "Look! here's a stupid aristocrat! Here's a ridiculous bluestocking!" And although Austen is a better writer than her peers, some of her characters have the traits of typical stock characters.

Mrs. Palmer in Sense & Sensibility is pretty much introduced by way of explanation. Austen makes it clear to us that she is friendly but silly and not very bright or well educated. She "was strongly endowed by nature with a turn for being uniformly civil and happy, [and] was hardly seated before her admiration of the parlour and every thing in it burst forth…. Mrs. Palmer’s eye was now caught by the drawings which hung round the room. She got up to examine them. 'Oh! dear, how beautiful these are! Well! how delightful! Do but look, mama, how sweet! I declare they are quite charming; I could look at them for ever.'"

“And then sitting down again, she very soon forgot that there were any such things in the room.”

For another example, let’s compare Lucy Barclay from Sarah Burney’s Clarentine with Anne Steele in Sense & Sensibility, Austen's earliest novel. Both women try to be more genteel than they are, and they betray themselves with vulgarity and poor grammar.

Miss Barclay lives with her uncle, Reverend Lenham, and her mother, who acts as his housekeeper. As mentioned in a previous post, Clarentine was terribly nervous about meeting her new housemates when she came to live with Mr. Lenham, but within a few hours of her arrival, she regards them both with contempt, especially the daughter.

We learn that Miss Barclay has a florid complexion and fierce eyes, and: “Her dress, the laborious result of indefatigable pains and trouble, was, at least as far as she knew how to make it so, fashionable even to extravagance; and betrayed such a total want of taste, and an affectation of negligence so evidently studied, that to Clarentine… she appeared more like a monstrous caricature, intended to excite ridicule and surprise, than any other thing she could compare her to.”

On the morning after her arrival in the household, Clarentine is taken aback when Miss Barclay enters her bedchamber before breakfast for a chat, and the author tells us so: "Well,' cried that young lady, seating herself as she spoke, and drawing the dressing-glass to the side of the table to reform some error in the set of her cap--- 'how did you sleep? I'm dying for my breakfast -- an't you?"

Clarentine, a little surprised at this early debut, smiled and said, "I have scarcely had time to think of it yet; I am but just dressed.''

[Miss Barclay mentions that her uncle is going away soon.]

"Then pray," resumed Clarentine, "let us go down, I should wish to see all I can of him before he sets out."

"Lord," said Miss Barclay, indolently rising, and still lingering before the glass, "one would think he was your lover, by the anxiety you express over him."

"I hope," said Clarentine, moving toward the door, "to find in him a friend -- and that perhaps may be better than a lover."

"I am sure," cried Miss Barclay, "I should not think so!" Elinor Dashwood, likewise, is taken aback by Miss Steele:

"Miss Steele, who seemed very much disposed for conversation, and... now said rather abruptly, “And how do you like Devonshire, Miss Dashwood? I suppose you were very sorry to leave Sussex.”

In some surprise at the familiarity of this question, or at least of the manner in which it was spoken, Elinor replied that she was.

“Norland is a prodigious beautiful place, is not it?” added Miss Steele.

“We have heard Sir John admire it excessively,” said Lucy, who seemed to think some apology necessary for the freedom of her sister.

[Elinor goes all Jane Fairfax-y here:] “I think every one must admire it,” replied Elinor, “who ever saw the place; though it is not to be supposed that any one can estimate its beauties as we do.”

“And had you a great many smart beaux there? I suppose you have not so many in this part of the world; for my part, I think they are a vast addition always." Elinor leaves Sir John's house "without any wish of knowing [the Miss Steeles] better."

The 2020 adaptation of Emma played up Mrs. Elton's tendency to overdress Mrs. Elton of Emma is from a wealthier family than Lucy Barclay or Anne Steele, but still from a lower class of society. She wants to be thought of as well bred. Like Lucy Barclay, she overdresses. By the time Austen wrote Emma, she was more apt to show rather than tell. Instead of describing Mrs. Elton's characteristics, she has Mrs. Elton betray herself through her dialogue:

The 2020 adaptation of Emma played up Mrs. Elton's tendency to overdress Mrs. Elton of Emma is from a wealthier family than Lucy Barclay or Anne Steele, but still from a lower class of society. She wants to be thought of as well bred. Like Lucy Barclay, she overdresses. By the time Austen wrote Emma, she was more apt to show rather than tell. Instead of describing Mrs. Elton's characteristics, she has Mrs. Elton betray herself through her dialogue:“How do you like [my gown]?—Selina's choice—handsome, I think, but I do not know whether it is not over-trimmed; I have the greatest dislike to the idea of being over-trimmed—quite a horror of finery. I must put on a few ornaments now, because it is expected of me. A bride, you know, must appear like a bride, but my natural taste is all for simplicity; a simple style of dress is so infinitely preferable to finery. But I am quite in the minority, I believe; few people seem to value simplicity of dress,—show and finery are every thing. I have some notion of putting such a trimming as this to my white and silver poplin. Do you think it will look well?”

Introducing Robert Ferrars Another thing I have learned to pay attention to is whether the stock characters are brought into the novel "just to be laughed at" as the 19th century critic Adolphus Alfred Jack says, or if they actually move the plot along. Clarentine, for example, meets and disdains a female scholar who has nothing to do with the plot whatsoever, apart from being the mother of a fashionable fop who plays a very slight part in the story. (In Sense & Sensibility, Robert Ferrars, with his toothpick case, is our foolish fop). He plays a crucial role in the happy ending, though he's a minor character.

Introducing Robert Ferrars Another thing I have learned to pay attention to is whether the stock characters are brought into the novel "just to be laughed at" as the 19th century critic Adolphus Alfred Jack says, or if they actually move the plot along. Clarentine, for example, meets and disdains a female scholar who has nothing to do with the plot whatsoever, apart from being the mother of a fashionable fop who plays a very slight part in the story. (In Sense & Sensibility, Robert Ferrars, with his toothpick case, is our foolish fop). He plays a crucial role in the happy ending, though he's a minor character.In Clarentine, vulgar Lucy Barclay is friends with the designing widow who has her eyes on the hero, so she is useful to the plot in that respect. Likewise, Mrs. Jennings and her daughter are coincidentally related to the Steele sisters, which brings them into the story. They also play an essential role in taking Elinor and Marianne from Devonshire to London and back again, which facilitates the meetings and separations of the plot. Mrs. Jennings is also a valuable conduit of news in the novel.

Anne Steele's most important interventions in Sense & Sensibility happen offstage. She betrays her sister's secret engagement through her stupidity. Later, she eavesdrops on a crucial conversation. Both Anne Steele and Mrs. Jennings' daughter Lady Middleton are left out of the wonderful Emma Thompson 1995 movie adaptation as unessential to the plot. But we can't imagine Emma without Mrs. Elton.

In the small and confined society of Highbury, Emma will be continually brought into contact with the Eltons, even though they would all gladly never see each other for the rest of their lives. Mr. Elton must perform the marriage ceremony for Emma and Mr. Knightley. Because of their relative social positions, Emma must have the Eltons over for dinner and meet them at other people's houses regularly. Surely Emma pays dearly for her sins! Austen has succeeded so brilliantly in her portrait of Mrs. Elton, that she rouses pity on our behalf for Emma.

I was surprised to discover that the pedantic bluestocking is a stock 18th-century novel character. Female novelists are merciless to the female pedant, and I'll talk about that next time we look at stock characters.

Next post: Your mother cannot spare you.

In A Marriage of Attachment, I provided Fanny Price's friend Mrs. Butters with an obnoxious daughter-in-law. Cecilia Butters is ungrateful and always looks on the negative side of things. She pushes Mrs. Butters' buttons, that's for sure! Click here for more about my books.

Published on May 02, 2021 00:00

April 25, 2021

CMP#43 Guilt , Misery, & Plot Devices

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. For the first post on this series about Mansfield Park and slavery, click here. "The students who were Jane Austen fans felt instantly complicit for liking stories where slavery might be present without an explicit critique."

-- Patricia A. Matthews, "Jane Austen and the Abolitionist Turn."

Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 61 no. 4, 2019, p. 345-361

"Let Other Pens Dwell on Guilt and Misery:" Colonialism as a Plot Device In previous posts, I shared some of the non-fiction and fictional literature around slavery and abolition written in Austen's time, to demonstrate that slavery was a much-discussed and debated topic. The novels I mentioned stand in contrast to Mansfield Park for their explicit detail; in the examples I gave, the authors readily expressed their abolitionist sympathies. There were also novels in which the worst thing to be said about West Indian planters was that they were vulgar and indolent.

I now come to the most dangerous part of my thesis. There are also many examples of fictional works which referred to the West Indies, to West Indian planters, even to a slave uprising (in the case of Belinda) without editorial comment. Authors such as Maria Edgeworth and Barbara Hoflund who wrote pro-abolition fiction also wrote books in which colonial wealth, such as could be acquired in India, was simply a handy plot device.

Boiling down the sugar syrup In an earlier post I talked about how the death of parents and guardians was often used to set up the plot in 18th century novels. These timely deaths provided the starting point for the friendless hero or heroine.

Boiling down the sugar syrup In an earlier post I talked about how the death of parents and guardians was often used to set up the plot in 18th century novels. These timely deaths provided the starting point for the friendless hero or heroine.Going to the East or West Indies to seek one's fortune is a convenient plot kickstarter. Fictional parents sometimes died on long sea voyages. For example, the father of the heroine in the popular comic opera Rosina "went to the Eastern Indies to better his fortune," but he and his wife are lost in a shipwreck. Rosina is orphaned and raised by a loyal servant.

In Whose the Dupe, a 1779 comedy, a character says his brother will "speak to Sir Jacob Jaghire to get me a commission in the East Indies: and, you know, everybody grows rich there." The Chevalier de Croustillac in A Romance of the West Indies "had dissipated his fortune, killed a man in a duel [and] had adapted the dangerous part of going to the West Indies to seek his fortune." He hoped to marry a rich widow with a plantation.

If you need to raise a character from poverty to wealth for your happy ending, the sudden acquisition of a colonial fortune is just the thing. Mrs. Davenport, The Merchant's Widow, is left in reduced circumstances with seven children after her husband's business fails and he dies. After years of privation, word arrives of an enormous inheritance from her late uncle in "Rio Janeiro" in "Peru." The actual source of the monies with which "Providence blessed" the family is not discussed; the money is presented as a fitting reward for the family's industry, filial loyalty, and piety. The Merchant's Widow came out the same year as Mansfield Park.

Likewise, in the next-to-last paragraph of Persuasion, Austen raises Mrs. Smith from poverty to comfort after Captain Wentworth untangles a problem with her late husband's property in the West Indies "with the activity and exertion of a fearless man and a determined friend."

The popular comedy The Liar (1762, but played in theatres in Austen's time) features an heiress with a huge fortune left to her by her father, "an India governor." "A governor!" exclaims the fortune-hunter. "Bushels of rupees and pecks of pagodas, I suppose."

Dr. Samuel Johnson was an ardent abolitionist, but even he uses the conveniently-acquired fortune in his 1751 essay

#153: A second son of a gentlemen, who knows he needs to work for a living, is "trifling in uncertainty" before choosing a career, when "an old adventurer, who had been once the intimate friend of my father, arrived from the Indies with a large fortune." There's not a word about how that fortune was acquired. The focus of the story is how well everyone treats the young man when they think he's the old man's heir, and how they shun him when the old man dies before altering his will.

The West Indian, (1771) another popular comedy, is not about colonialism or enslaved persons. It's about a high-spirited planter who is a bit of a rogue. It's also about timely surprise inheritances. (Though one character remarks, "girls of her sort are not to be kept waiting like negroe slaves at your sugar plantations," which presumably means "waiting" in the sense of "serving," like "wait upon you" or "waitor.")

Maria Edgeworth's 1809 tale Maneuvering concerns a scheming widow. She hopes her late husband's friend, who has returned to England from Jamaica, will leave his fortune to her family. Her schemes, not the evils of slavery, are the theme of the novel. Wealthy Mr. Palmer is presented as a kind but credulous old duffer, not as an evil slave-owner.

Mr. Vincent, distraught over his gambling debts, is rescued by the hero If you need a romantic foil to compete for your heroine, and you want someone with a touch of sexy exoticism, a West Indian planter is a good choice. That’s Mr. Vincent in Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801) who comes complete with a black servant. He doesn't succeed with our heroine, who rejects him because he's a gambler--not because he owns slaves.

Mr. Vincent, distraught over his gambling debts, is rescued by the hero If you need a romantic foil to compete for your heroine, and you want someone with a touch of sexy exoticism, a West Indian planter is a good choice. That’s Mr. Vincent in Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801) who comes complete with a black servant. He doesn't succeed with our heroine, who rejects him because he's a gambler--not because he owns slaves.The nouveaux-riche planters were also sometimes portrayed as being social upstarts. In The Gipsy Countess (1799) Colonel Cary is a "nabob," that is, a man who obtained his fortune of "half a million" in India. His low-born second wife is the "rich widow of a West India planter." Author Elizabeth Gunning has much to say about his vulgarity, but apart from a passing reference to "ill-gotten wealth," little to say about how he obtained his fortune. At most you could say that Gunning's vulgar nabob and his wife are behave horribly because that's what nabobs and slaveowners do. But the focus is not on the people they enslaved and exploited. The stepmother is a villain because of the way she treats her stepdaughter, not because she's a slaveowner.

The sudden acquisition of a colonial fortune was sometimes used to raise the hero from poverty to riches. As D.N. Ghosh (2001) points out being a West Indian planter was actually more respectable than being a merchant, to Austen's contemporaries. It’s a more gentlemanly profession; it’s akin to farming. So, Savillon in Julia de Roubigné goes to the West Indies. So does Captain Sunderland in Belinda -- he needs to make a fortune so he can court the beautiful Virginia whom he has seen but never spoken to. Unbeknownst to him, while he is away, Virginia falls in love with his portrait. He returns a few years later with his friend Mr. Hartley, who--what a coincidence--turns out to be the father of Virginia.

“My dear daughter,” [says her father], “give me leave to introduce to you a friend, to whom I owe more obligations than to any man living…. This gentleman was stationed some years ago at Jamaica, and in a rebellion of the negroes on my plantation he saved my life...”

No-one asks about the fate of the negroes, or how many of them were killed during the uprising or afterwards. The entire focus is on the first meeting of the lovers, and we move straight on to the happy ending.

Finally, If you need to send one of your characters away for a long time for plot purposes, the East or West Indies are handy. Henry St. Clear, hero of The Gipsy Countess, reunites with his long-lost sister when he returns to England. Amelia Opie used the distant heir who shows up to claim his inheritance in Appearance is Against Her (1813). Elizabeth Helme's pro-abolition novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest (1796) has two main characters who disappear for years and who then re-appear when the plot calls for them. Uncle Henry tells his niece "cheer up, my girl, I am getting rich for thee," and he sets off for India, but he disappears for more than a decade, until a remarkably coincidental meeting occurs in a jeweler's shop. Another character goes to the West Indies and marries a rich widow, returning years later to liven up the final volume with his terrible villainy.

In Sense & Sensibility, Colonel Brandon goes to the East Indies to forget his broken heart over Eliza after she is forcibly married to his brother. He returns too late to save her from disgrace and death. Unspecified financial trouble in Antigua is the excuse to get rid of Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park, but Austen's purpose in getting rid of him was to serve her plot. If the troubles in Antigua were intended to raise a plot conflict over slavery, then there should be some mention of it and some resolution of the issue in the novel. There is none.

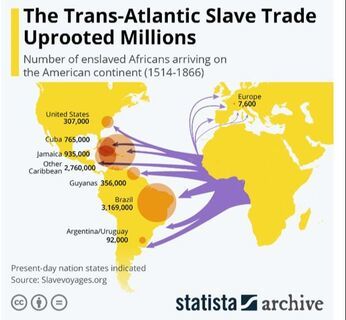

The impressment of sailors from American ships by the British was one of the causes of the war of 1812 So, hear me out: consider the possibility that Fanny's question about the slave-trade, asked of a slaveowner, is not as explosive as modern critics assume it to have been. It was not the equivalent of tossing an atom bomb into the narrative. Not all references to India or the West Indies were intended as stark criticisms of colonialism. There were plenty of West Indian planters and East Indian nabobs in 18th century literature and they weren't all villains.

The impressment of sailors from American ships by the British was one of the causes of the war of 1812 So, hear me out: consider the possibility that Fanny's question about the slave-trade, asked of a slaveowner, is not as explosive as modern critics assume it to have been. It was not the equivalent of tossing an atom bomb into the narrative. Not all references to India or the West Indies were intended as stark criticisms of colonialism. There were plenty of West Indian planters and East Indian nabobs in 18th century literature and they weren't all villains. Austen's use of the Bertram properties in Antigua and the "slave trade" question more closely resembles the novels I've listed above, than it does the explicitly anti-slavery stories I mentioned in the previous post.

Consider also how the "dead silence" passage serves the plot. Austen appears to have entirely prosaic reasons for the conversation between Edmund and Fanny. It reinforces dynamics which come to fruition later in the story. We learn that Fanny is rising in Sir Thomas’s estimation, and Fanny is less intimidated by him. The other young people find the evenings boring now that Sir Thomas is home. Maria and Julia can't wait to get out of there and get to Brighton and London, and Edmund is besotted with Mary Crawford; he continually, unthinkingly, wounds Fanny by talking about her.

I am not the only heretic on this issue. Critic A.J. Downie writes: “Once again, Austen’s point appears to be not about the slave trade but about the manners of Sir Thomas’s daughters.” Austen places her emphasis in the “dead silence” passage on Maria and Julia's silence, not on Sir Thomas’s answer, whatever it was. I suggest that the passing reference to the ‘slave-trade” is treated in a similar fashion to Tom Bertram's passing reference to “this business in America.” If the impressment of men into the Navy was as historically fraught for modern scholars as chattel slavery, we’d have essay after essay explaining the serious symbolic meaning behind a funny throwaway line that Tom uses to cover up the fact that he's been gossiping about Dr. Grant. Instead we have a host of critics and readers reading anti-slavery into Mansfield Park. This same scrutiny isn't brought to bear on lesser-known novels like The Merchant's Widow or The Gipsy Countess. The difference, of course, is that Mansfield Park was written by a beloved author whose work is canonical.

To repeat one more time, it is factually not the case that authors of Austen's time didn't mention slavery in their novels. In my survey, I came across only one novel in which the author herself writes disdainfully of Africans (as opposed to novels where people who are clearly intended to be bad people say or do cruel things.) The others are either neutral on the subject (the ones listed above) or are pro-abolition (discussed here). If I find more good examples, I'll add them.

"She had to do so indirectly through metaphor and small hints... [slavery] wasn't something novels ever talked about." Nope. Wrong. To recap: Austen could have explicitly emphasized the slavery in Mansfield Park, had she chosen to, but she didn't. Scholars who insist that Mansfield Park is about slavery are relying upon hidden symbolism, not the text or the plot. In my opinion, these interpretations are (1) questionable and (2) overthrow the structure and meaning of the novel.

"She had to do so indirectly through metaphor and small hints... [slavery] wasn't something novels ever talked about." Nope. Wrong. To recap: Austen could have explicitly emphasized the slavery in Mansfield Park, had she chosen to, but she didn't. Scholars who insist that Mansfield Park is about slavery are relying upon hidden symbolism, not the text or the plot. In my opinion, these interpretations are (1) questionable and (2) overthrow the structure and meaning of the novel. My conclusions are not driven by a wish to avoid the subject of slaver, or a fear of acknowledging it. Slavery and colonialism were not "erased" from my school textbooks or from what I have read on my own. I was reading about world history and the British abolitionist movement 50 years ago. I first learned learned about slavery when my parents were active in the civil rights movement. “Every generation thinks it invented sex, and every generation is wrong,” said the American writer Robert Heinlein. In the same fashion every generation thinks it has discovered the sins of the past.

Now, if it is true that Mansfield Park is not an abolitionist document in any significant sense, where does that leave us? Can a novel about a slave-owning family still be a great novel and a literary masterpiece? Can it be a novel with profound moral lessons? It is for me, but I recognize that others may feel differently. It's still worth discussing, I think, but on another occasion.

I've talked about what I think Mansfield Park is not about. Later I'll go back to discussing what I think it is about. I'll take a break and talk about fops and fools for a change! In A Contrary Wind, my character William Gibson, a poet and admirer of Fanny Price, is pressed into the navy and ends up with the West African Squadron, helping to suppress the slave trade. Click here for more about my Mansfield Trilogy.

Published on April 25, 2021 00:00

April 23, 2021

CMP#42 Was Slavery a Taboo Topic? Part 2

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. "Habit, the tyrant of nature and of reason, is deaf to the voice of either; here she stifles humanity, and debases the species—for the master of slaves has seldom the soul of a man.”

– Savillon, in Henry MacKenzie’s Julia de Roubigné (1777) Was Slavery a Taboo Topic in Austen's Time, Part Two: "This Vilest Traffic"

Children's story by Mary Pilkington, 1807 In my previous post, I gave a sampling of non-fiction books of the late 18th and early 19th century, including books for children, which discussed slavery and colonialism.

Children's story by Mary Pilkington, 1807 In my previous post, I gave a sampling of non-fiction books of the late 18th and early 19th century, including books for children, which discussed slavery and colonialism. Mansfield Park, as previously discussed, is not explicit about slavery. In fact, as I discussed, references to Sir Thomas Bertram's trip to Antigua in the novel tend to be sympathetic to him, the poor guy who must make the journey away from his family.

Critics nevertheless insist that Austen's third novel is all about slavery, and they prove this by pointing out that Austen never talks about slavery in the novel. "The second major social issue that Austen makes notable by its absence from discussion is slavery.""Austen "mask[s] the issue of slavery throughout the novel.""Disengaging the subject of slavery from the Mansfield Park estate seems to be the implied

critique of slavery in Austen’s Mansfield Park.""Slavery plays an important, though subverted, role in the novel." "Austen's art is ironic and subtly allusive" In this respect, they sometimes rely on the incorrect claim that Sir Thomas Bertram was silent when Fanny Price asked him about the slave trade:"whatever political and colonial critique might have been implied by Fanny’s statement about Sir Thomas’s silence is subordinated to the familial drama of surrogacy and marriage and parenting... The world of the colonies is represented or subsumed by the terms of representation by the other world of the domestic." "the text disintegrates at 'dead silence,' a phrase that ironically speaks ..."“Austen deliberately invokes the dumbness of Mansfield Park concerning its own barbarity

precisely because she means to rebuke it.""The unanswered question is a kind of Machereyan silence which ‘uncovers what it cannot say’ (Macherey 1978: 84). Slavery may haunt the novel as a negative presence - in the title, in Fanny’s preference for Cowper’s poetry, a noted abolitionist poet, and so on - but Austen keeps it off-stage..." Thus, so subtle is Austen's art that the less she mentions slavery, the more important it is to her narrative.

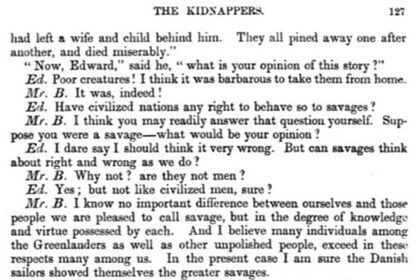

Below are some examples of novels which are not quite so subtle, There were also many plays which touched on the West Indies and the subject of enslaved persons, but for reasons of length, I'll stick with novels. In these novels the topic of slavery was raised without symbolism, allegory, implication, irony, haunting, veiling, or cloaking. As well there are many examples of people of colour being portrayed with sympathy, if not authenticity.

In the Advantages of Education (1793) by Jane West, Mrs. Williams joins her husband in the West Indies but leaves her daughter behind in England with a guardian. She doesn’t want her daughter exposed to the unhealthy climate, or to her dissolute father. “His faults,” [said Mrs. Williams of her husband], “are no more than the common vices of the island. The planters, generally speaking, countenance each other in irregularities, at which an English libertine would blush. The redundant fertility of their tropical climes, and the bad habits which slavery introduces, are not favourable to the cause of virtue. The Lord of the soil, accustomed to the mean subservience of those around them… soon overcomes every restraint of conscience."

It is clear that she is referring to sexual concubinage. Mrs. Williams also blamed the “too great distinction,” that is, the power disparity, between slave-owners and the enslaved, which led to “pernicious examples of pride, cruelty, and luxury, which is unhappily prevent.” The emphasis is more on the harms to English virtue than to the enslaved persons, but if Jane West could say this in 1793, in a novel aimed at mothers and daughters, how can critics claim that Austen had to be more reticent in 1814?

A spoilt girl tosses beer at her maid in The Barbadoes Girl. She later reforms. As scholar George Boulukos has explained, the trope of the "grateful negro" was a common one in literature of this period. A grateful "mulatto" woman features in Amelia Opie's novel Adeline Mowbray (1804). When the heroine rescues her husband from debtor's prison, Savanna vows her eternal loyalty.

A spoilt girl tosses beer at her maid in The Barbadoes Girl. She later reforms. As scholar George Boulukos has explained, the trope of the "grateful negro" was a common one in literature of this period. A grateful "mulatto" woman features in Amelia Opie's novel Adeline Mowbray (1804). When the heroine rescues her husband from debtor's prison, Savanna vows her eternal loyalty. A young African tells how he was abducted from his parents while the girl he loved was murdered before his eyes in Cephisa, A Moral Tale (1802) by Mrs. Crowther. Unusually for this type of literature, the boy speaks in eloquent, grammatical English, instead of a cringe-inducing pidgin English. He is so grateful to the planter who freed him that he sits and pines to death by the planter's grave.

The sufferings of black people in Cephisa and in the next two examples are used to provide a moral awakening to selfish white people.

The Barbadoes Girl: A Tale for Young People (1825) by Barbara Hoflund is about the spoilt daughter of a West Indian planter who comes to live with a family in England. Her moral reformation is the central theme of the book, not emancipation. The tale includes graphic detail about the cruelties of slave-owners and there are discussions of emancipation.

In Elizabeth Helme's Modern Times (1814) a selfish girl orders her slave, Juba, to jump into the ocean to rescue a whip she dropped which the waves are carrying away. He protests, but obeys, and is killed by a sea-monster. Fanny eventually becomes a better person through the good examples of others.

Maria Edgeworth’s 1804 short story The Grateful Negro tells of an enslaved African man who is purchased from a cruel planter by a more humane one. In gratitude, he alerts his master to a pending slave revolt.

The story is problematic for modern readers, but there is also a brief but significant passage where Edgeworth has her two planters debate the economic rationale for slavery: “Granting it to be physically impossible that the world should exist without rum, sugar, and indigo, why could they not be produced by freemen, as well as by slaves?” the kind planter asks. Likewise, Henry MacKenzie’s Julia de Roubigné (1777) features an extended section in the second volume in which the hero, Savillon, improves the conditions of life on the plantation. He also wonders if paid labour or using cattle would work as well or better.

John Moore's potboiler Zeluco (1789) also features a slavery debate; a humane doctor argues with a cruel slaveowner. This kind of debate between a defender of slavery and an abolitionist also occurs in Charlotte Smith's Desmond (1792). Smith repeated her anti-slavery message in The Wanderings of Warwick (1794). Sarah Scott's Sir George Elliot (1766), is an admiring account of a reform-minded West Indian planter. It details how he manages his plantation and how he attempts to protect the enslaved persons from maltreatment after his death.

Amelia Opie, (1769 – 1853), author and abolitionist My next examples are two fictionalized memoirs that feature slave uprisings.

Amelia Opie, (1769 – 1853), author and abolitionist My next examples are two fictionalized memoirs that feature slave uprisings.In The History of the Life and Adventures of Mr. Anderson (1754), by Edward Kimber, a rebellion of enslaved persons is portrayed sympathetically. Slaves are punished with death for attempting to help the heroine escape. The uprising occurs just as the heroine is about to be ravished by the plantation owner’s son, so the actions of the slaves are used by the author to effect the rescue of the heroine.

The Memoirs Of The Life And Travels Of The Late Charles Macpherson (1800) compares the outcome of two different attempts to improve the situations of enslaved persons, but I can’t enter into the details without causing offense to modern sensibilities. Suffice it to say that one attempt at reform results in rebellion and another, different approach, doesn’t. The novel makes an argument in favour of education and moral instruction; amelioration, in other words. If Austen had wanted to include a Black character in Mansfield Park, she could have had Sir Thomas bring an emanicipated slave back from Antigua with him. She didn't, and instead, scholars have resorted to Fanny-is-just-like-a-slave parallels. But other authors of the period did portray Black characters. Perhaps the topic was going to come to the fore in Sanditon, her unfinished novel, which features a "half mulatto" heiress from the West Indies.

Sarah Burney's Traits of Nature (1812) features a servant, Amy, who is devoted, but not slavishly so, to the heroine. Amy speaks her mind freely, (although in pidgin) and has some agency in the novel. The heroine's brother (who is a jerk to everybody) refers to her appearance in insulting terms, but Amy retains her dignity and self-possession. The most remarkable thing about Amy is that she is not presented as being anything remarkable. The same author featured a black servant in another novel, Geraldine Fauconberg (1808). Caesar is repulsed by a Welsh servant girl when he tries to flirt with her. The encounter is presented comically.

In The Farmer of Inglewood Forest (1796), by Elizabeth Helme, Julia and Felix are emancipated from servitude. In the novel they serve a similar role as "Noble Savages" -- they are virtuous and wise, yet innocent. They provide commentary on English society. Felix is sent to sell a valuable watch so his friend Mrs. Palmer can bury her child. He explains she “must sell [the watch] to pay those rites which your country’s custom demands before the body of her child can be permitted to mingle with the dust; to hire men who assume the semblance of sorrow with a black coat, and pay for a peculiar spot of earth, as if all on which the sun shines was not equally hallowed!”

Julia and Felix also have agency in the novel -- they serve, rescue, and otherwise support the white people to whom they are devotedly grateful. Julia, more recently arrived in Jamaica, speaks in pidgin English. She defends a young lady from abduction at the risk of her life. ("Bad white man -- wicked Christian -- me die before let take away Missey.") This novel features branding, flogging, rape, and slave uprisings but even these lurid events are a minor sub-plot compared to the main plot of the story which focusses on an English family.

Elizabeth Helme wrote about slavery repeatedly, including child slavery in India, and she wrote approvingly of African society (the Hottentots) at a time when Africans were inevitably referred to as savages. She also outsold Austen in her day.

Africans are actually main characters in Anna MacKenzie's Slavery, or The Times, (1793). The novel features an inter-racial marriage between an Englishwoman and the son of an African prince.

Mary Brunton (1778 – 1818) Lastly, I'd like to compare Mary Brunton's Discipline with Austen's Mansfield Park. Discipline came out the year after Mansfield Park. Both have main characters who leave England for an extended period to manage their plantations. In both cases, these characters are not portrayed as villains (Maitland is the hero) but they are enriched by their colonial holdings. In both books, the slavery connection is a minor part of the plot. Broadly speaking, female rectitude is the theme of both Discipline and (leaving the "symbolic" argument aside for a moment) Mansfield Park.

Mary Brunton (1778 – 1818) Lastly, I'd like to compare Mary Brunton's Discipline with Austen's Mansfield Park. Discipline came out the year after Mansfield Park. Both have main characters who leave England for an extended period to manage their plantations. In both cases, these characters are not portrayed as villains (Maitland is the hero) but they are enriched by their colonial holdings. In both books, the slavery connection is a minor part of the plot. Broadly speaking, female rectitude is the theme of both Discipline and (leaving the "symbolic" argument aside for a moment) Mansfield Park.Brunton and Austen both need to remove characters from the action for plot purposes -- while Sir Thomas is away, the Crawfords get up to mischief at Mansfield; while Maitland is away, the selfish, coquettish heroine is disciplined by tribulation. But Brunton puts the West India connection to a double use -- she speaks out against slavery. She tell us Maitland is a “West India merchant and interested [that is, benefitting from] the continuation of the slave-trade, he opposed, with all the zeal of honour and humanity, this vilest traffic that ever degraded the name and the character of man. In [Parliament] he lifted up his testimony against this foul blot upon her fame—this tiger-outrage upon fellow-man—this daring violation of the image of God.”

After failing to overturn slavery in Parliament, Maitland returns to the West Indies “to mitigate the evil which he could not cure.”

Compare that explanation to the one which sends Sir Thomas to Antigua: "Sir Thomas found it expedient to go to Antigua himself, for the better arrangement of his affairs."

Unlike Brunton, Austen does NOT take the opportunity to say something about slavery or Sir Thomas's attitude toward it. The explanation is short as possible, and quite vague. There is no need to search for symbolic allusions to slavery in the novels I've listed above. There is no need to produce essays about how the absence of mentions of slavery means the book is about slavery. But then, none of the books I've listed above have been as read, studied, commented upon, or pored over nearly as much as Mansfield Park.

To sum up:

None of the novels I have listed above would be considered equal to Austen in terms of literary merit. But all of them are much more explicit on the subject of slavery and abolition.

I think Jane Austen had abolitionist sympathies but she chose not to be explicit about slavery in Mansfield Park. Why? We can only speculate, but I trust I have demonstrated that it could not have been out of fear of government censorship or social sanctions. This is a charming tribute to Austen, but no fan of Elizabeth Helme would be reduced to pointing to references to apricots to demonstrate her "bravery" about speaking up about slavery. References:

The Cambridge University Press Orlando database was a valuable source of information.

Campbell, Elaine. “Oroonoko's Heir: The West Indies in Late Eighteenth Century Novels by Women."

Caribbean Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 1/2, 1979, pp. 80–84. JSTOR

Moretti,Franco. Atlas of the European Novel, 1999

The managers of the colony for freed slaves at Sierra Leone were hard-pressed to accommodate the influx of freed slaves and to provide them with food, clothing and housing. The struggles of the West Africa Squadron are vividly portrayed in Sweet Water and Bitter by Siân Rees. This book was inspirational in helping me to write the second volume of my Mansfield Trilogy, A Marriage of Attachment. Click here for more about my books.

The managers of the colony for freed slaves at Sierra Leone were hard-pressed to accommodate the influx of freed slaves and to provide them with food, clothing and housing. The struggles of the West Africa Squadron are vividly portrayed in Sweet Water and Bitter by Siân Rees. This book was inspirational in helping me to write the second volume of my Mansfield Trilogy, A Marriage of Attachment. Click here for more about my books.

Published on April 23, 2021 00:00

April 21, 2021

CMP#40 In Defense of Sir Thomas

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. “Of all the fathers of Jane Austen’s novels, Sir Thomas is the only one

to whom admiration is given [by Austen]." - Lionel Trilling

"The catastrophe of the novel depends upon our moral sympathy with Sir Thomas"

-- Marvin Mudrick In Defense of Sir Thomas

Harold Pinter as a guilty Sir Thomas in the 1999 movie adaptation Sir Thomas Bertram of Mansfield Park is almost certainly a slave owner. That being the case, it may seem not only impossible to rehabilitate his character, but indefensible to make the attempt. The question of slavery hangs over the novel, as I discussed in the previous post about symbolism.

Harold Pinter as a guilty Sir Thomas in the 1999 movie adaptation Sir Thomas Bertram of Mansfield Park is almost certainly a slave owner. That being the case, it may seem not only impossible to rehabilitate his character, but indefensible to make the attempt. The question of slavery hangs over the novel, as I discussed in the previous post about symbolism.In Jane Austen: Writing, Society, Politics, Tom Keymer points out “Austen could perfectly well have positioned [Sir Thomas] as a self-serving anti-abolitionist, or she could have made him a reformist like the hero of Mary Brunton’s Discipline (1815)...”

Yes, she could have made him a villain or a reformer, but she does neither. She tells us nothing about Sir Thomas's holdings in Antigua or how he manages them. The 1999 movie adaptation portrays him as a menacing and perverted man who forced himself on captive women, but even people who like this movie understand it is not a faithful representation of the novel.

On the other hand, some have suggested that Sir Thomas must have sold his plantation when he went to Antigua, or that after all, the income from Antigua probably didn’t represent much of the family income compared to his local rents, and so on. Yes, perhaps he was the most benevolent slaveowner in Antigua. I won't bother attempting to speculate, because while, as we have seen, emancipation versus amelioration was discussed in Austen's time, freedom versus slavery is not contentious today. No-one today would be inclined to give Sir Thomas a patient hearing on the matter. And in the end it is unproven and unprovable because he's a fictional character. I am not defending the fact of Antigua. Austen didn't tell us anything about Antigua.

So when I say I am writing in defense of Sir Thomas, I am defending the role Sir Thomas plays in the novel, because his character is crucial to the meaning and structure of Mansfield Park. Scholar Mary Nardin points out: "Sir Thomas’s failures as a parental guide drive the plot: the union he permits between Maria and Mr. Rushworth ends in divorce; the matches he promotes never occur; and the marriage between Fanny and Edmund that concludes the novel is the very marriage that he had determined to prevent when he agreed to adopt his niece."

Does Austen defend Sir Thomas? How does she intend for him to be seen?

In my opinion, Austen presents Sir Thomas as a man with flaws who made mistakes, but she does not portray him as a villain. He is excessively formal in his speech and ponderous in his thinking. Critic Adolphus Alfred Jack declared in 1899 that he was a "of a genus extinct." He seems to have been born with his wig and knee breeches; it is impossible to imagine him as a child, difficult even to imagine him courting the beautiful Maria Ward.

Bernard Hepton and Sylvestra La Tousel as Sir Thomas and Fanny in the 1983 adaptation Whenever Austen-as-narrator addresses us directly, she is setting up her character-driven plot. She directs our attention here and there. Early in the novel, she gives us a heads-up about Mrs. Norris's character: she "might so little know herself" as to believe herself to be "the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world." She tell us Lady Bertram "was not disturbed by any alarm for Sir Thomas's safety, or solicitude for his comfort [when he went to Antigua] being one of those persons who think nothing can be dangerous, or difficult, or fatiguing to anybody but themselves."

Bernard Hepton and Sylvestra La Tousel as Sir Thomas and Fanny in the 1983 adaptation Whenever Austen-as-narrator addresses us directly, she is setting up her character-driven plot. She directs our attention here and there. Early in the novel, she gives us a heads-up about Mrs. Norris's character: she "might so little know herself" as to believe herself to be "the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world." She tell us Lady Bertram "was not disturbed by any alarm for Sir Thomas's safety, or solicitude for his comfort [when he went to Antigua] being one of those persons who think nothing can be dangerous, or difficult, or fatiguing to anybody but themselves."Austen foreshadows the consequences that arise when her characters, with their individual strengths and failings, come into contact or conflict with others, as when she tell us Maria has "contempt of the man she was to marry."

Austen's comments on Sir Thomas have more of extenuation about them. She explains why he makes the mistakes that he makes, but she does so without explicitly condemning him. For example, she gives a lengthy explanation for why he lets Maria's marriage to Rushworth go ahead. And none of her authorial commentaries about Sir Thomas touch on support for, or guilt about, slavery. Let's review them.

Austen introduces Sir Thomas as a man of "pride" but also "principle," who gives a living to his clergyman friend Rev. Norris, and helps the impecunious Price family. Little Fanny is so frightened of him that she cannot love him, yet she completely imbibes the principle that she should show respect for her elders. In contrast, Julia does not acquire "that just consideration for others... that principle of right." Austen tips us off that "Sir Thomas did not know what was wanting" in the moral education of his daughters, "because, though a truly anxious father, he was not outwardly affectionate, and the reserve of his manner repressed all the flow of their spirits before him."

Austen introduces Sir Thomas as a man of "pride" but also "principle," who gives a living to his clergyman friend Rev. Norris, and helps the impecunious Price family. Little Fanny is so frightened of him that she cannot love him, yet she completely imbibes the principle that she should show respect for her elders. In contrast, Julia does not acquire "that just consideration for others... that principle of right." Austen tips us off that "Sir Thomas did not know what was wanting" in the moral education of his daughters, "because, though a truly anxious father, he was not outwardly affectionate, and the reserve of his manner repressed all the flow of their spirits before him." Sir Thomas is very much the paterfamilias of the household. In one reference to his relationship with his servants, he speaks respectfully of "my friend Christopher Jackson" the carpenter, whom he holds blameless for building a theatre in the billiard room. In contrast, Mrs. Norris harasses the servants and Maria makes a rude remark about their coachman Wilcox. Mary Crawford praises Sir Thomas as the ideal husband, and Mrs. Grant explains to Mary that his household suffers when he's away -- "nobody else can keep Mrs. Norris in order."

Henry Crawford assumes that Edmund will be an absentee clergyman. He'll throw some money at a curate to do all the work and keep most of the income for himself. As Henry says to his sister, "a sermon at Christmas and Easter, I suppose, will be the sum total of sacrifice.” Sir Thomas corrects Henry: Edmund will live amongst his parishioners, and he, as a father, would be "deeply mortified" if his son did less. Edmund chimes in with, “Sir Thomas undoubtedly understands the duty of a parish priest. We must hope his son [referring to himself] may prove that he knows it too."

The glib and worldly Henry is silenced, and "bowed his acquiescence." Today, we would counter a "little harangue" from Sir Thomas with: "Um, yeah, you know what's worse than being an absentee clergyman? Slavery, maybe?" But surely Austen intended for the reader to agree with Sir Thomas and Edmund, pompous though they may be.

Furthermore, as scholar J.A. Downie points out, Fanny -- our heroine -- sees things the way Sir Thomas sees them. Fanny knows Sir Thomas would disapprove of putting on a play, particularly one as racy as Lover's Vows, and so she thinks the young people shouldn't do it. Sir Thomas expects Fanny to treat her horrid Aunt Norris "with the respect and attention that are due to her," and Fanny expects Mary Crawford to speak respectfully of her dissolute old uncle. “[S]he ought not to have spoken of her uncle as she did. I was quite astonished."

Sir Thomas returns from Antigua in the 1983 adaptation to find Mr. Yates ranting Austen explains the mistakes Sir Thomas makes. He realizes his daughter Maria doesn't love her dullard of a fiancé, but he doesn't resist when she goes ahead with the marriage. "It was an alliance which he could not have relinquished without pain... Mr. Rushworth was young enough to improve... Such and such-like were the reasonings of Sir Thomas, happy to escape the embarrassing evils of a rupture... happy to secure a marriage which would bring him such an addition of respectability and influence, and very happy to think anything of his daughter’s disposition that was most favourable for the purpose." Austen goes on at greater length, I've only excerpted part of it.

Sir Thomas returns from Antigua in the 1983 adaptation to find Mr. Yates ranting Austen explains the mistakes Sir Thomas makes. He realizes his daughter Maria doesn't love her dullard of a fiancé, but he doesn't resist when she goes ahead with the marriage. "It was an alliance which he could not have relinquished without pain... Mr. Rushworth was young enough to improve... Such and such-like were the reasonings of Sir Thomas, happy to escape the embarrassing evils of a rupture... happy to secure a marriage which would bring him such an addition of respectability and influence, and very happy to think anything of his daughter’s disposition that was most favourable for the purpose." Austen goes on at greater length, I've only excerpted part of it.Sir Thomas misinterprets Fanny's refusal of Henry Crawford's marriage proposal. He can't understand it; he gives his arguments in favour of the match and they are pretty sound, pragmatic, 18th-century reasons. This is the dramatic moment of rupture in the good understanding between Fanny and Sir Thomas. He, like Edmund, has been beguiled by the Crawfords, and poor Fanny is left completely alone, clinging to her principles and her own judgement of Henry's character. Yet, even as she trembles under his anger, we are told she thinks of him as discerning, honourable, and good. Later, when Sir Thomas's eyes are opened, once he understands why Fanny refused Henry, he agrees with her whole-heartedly. Their principles are the same. Their outlook on life is the same.

We are also reminded that Sir Thomas is the moral lodestar of the book when Austen tells us Lady Bertram, "did not think deeply, but, guided by Sir Thomas.... thought justly on all important points." When Maria leaves her husband and runs off with Henry Crawford, Lady Bertram "saw, therefore, in all its enormity, what had happened," Sir Thomas can't be our moral guide if we are are compelled to respond, "You know what's worse than running off with another man within a year of your wedding? Slavery, that's what." We can either accept what Austen says -- Sir Thomas is the moral guide -- or find some way to interpret her as meaning the opposite of what she says, or meaning two opposite things at once in a very complicated and nuanced way.

Fanny and her younger sister Susan in Portsmouth After Maria's marriage ends in disaster and Julia elopes with the trifling Mr. Yates, Sir Thomas suffers tremendously and for a long time: "the anguish arising from the conviction of his own errors in the education of his daughters was never to be entirely done away... Bitterly did he deplore a deficiency which now he could scarcely comprehend to have been possible. Wretchedly did he feel, that with all the cost and care of an anxious and expensive education, he had brought up his daughters without their understanding their first duties, or his being acquainted with their character and temper." Anguish. Bitter. Wretched. Austen uses strong terms to describe Sir Thomas's self-recrimination.

Fanny and her younger sister Susan in Portsmouth After Maria's marriage ends in disaster and Julia elopes with the trifling Mr. Yates, Sir Thomas suffers tremendously and for a long time: "the anguish arising from the conviction of his own errors in the education of his daughters was never to be entirely done away... Bitterly did he deplore a deficiency which now he could scarcely comprehend to have been possible. Wretchedly did he feel, that with all the cost and care of an anxious and expensive education, he had brought up his daughters without their understanding their first duties, or his being acquainted with their character and temper." Anguish. Bitter. Wretched. Austen uses strong terms to describe Sir Thomas's self-recrimination.The quote above is a brief excerpt from a much longer passage, near the end of the novel, when Austen is summing up the story.

It begins with "Sir Thomas, poor Sir Thomas, a parent, and conscious of errors in his own conduct as a parent, was the longest to suffer." Austen then wraps up Tom Bertram's storyline -- his redemption makes him "useful to his father" -- then returns to Sir Thomas's thoughts while Edmund is consoling himself by talking to Fanny. Then another long passage about Sir Thomas thinking about his failures as a parent.

Next Austen briefly sums up Mrs. Norris, after which she returns to Sir Thomas again. Then Austen moves on to wrap up Henry Crawford, Julia, the Grants, then Mary Crawford, then back to Edmund, then back to Sir Thomas again, to assure us that he and Fanny are are the best of terms, (who cares if, he's a villain?), then we go briefly to Lady Bertram, Susan Price, and then the Price brothers, to praise Sir Thomas for his charity towards them. Fanny and Edmund's marriage and the success of the Prices form the chief consolation for broken-hearted Sir Thomas. Then we have two more brief paragraphs about Fanny and Edmund. The End.

Sir Thomas gives his blessing to the union of Fanny and Edmund Austen devotes more space to Sir Thomas in her concluding chapter than any other character, including Fanny. His reaction to the union of Fanny and Edmund is accorded as much emphasis as the feelings of Fanny and Edmund themselves.

Sir Thomas gives his blessing to the union of Fanny and Edmund Austen devotes more space to Sir Thomas in her concluding chapter than any other character, including Fanny. His reaction to the union of Fanny and Edmund is accorded as much emphasis as the feelings of Fanny and Edmund themselves.In contrast, Mrs. Norris is curtly dismissed from the stage, without a whiff of sympathy. "She was regretted by no one at Mansfield." We are assured that her departure was a "supplementary comfort" for Sir Thomas. Most significantly, Sir Thomas's self-accusations have nothing to do with slavery. None of his remorse relates to the fact that he (probably) keeps people captive on an island to grow sugar cane for profit. If this is really a novel about slavery and the patriarchy, it makes no sense to leave this issue not only unresolved, but undiscussed. Moreover, if Sir Thomas is the villain, how can he also be the moral arbiter at Mansfield Park? If Sir Thomas is an utter villain, why is he not punished as Maria or Mrs. Norris are?

Why is Sir Thomas the most important character in the conclusion, one for whom Austen shows sympathy, not condemnation? And how can feminist critics wave all this away?

Sir Thomas, Fanny, and Edmund are the ones left standing at the end of the book, while the attractive, seductive Crawfords are rejected. Sir Thomas is one of those who Austen calls "not greatly at fault."

J.A. Downie says, "Does Austen mean her readers to question and to reject the moral outlook espoused by all three of these central characters in Mansfield Park?" Either Austen intends us to side with Sir Thomas, Fanny and Edmund, or she intends for us to take the whole thing ironically, to see her as meaning the opposite of what she says for 159 thousand words. That's quite the sustained use of irony.

While Mansfield Park's stern moral universe is often unappealing to modern readers, I think the upside-down interpretation is completely untenable.

Next post: I've mentioned that slavery was not a taboo subject in Austen's time. I'll present some evidence. In my Mansfield Park variation, A Contrary Wind, Sir Thomas does not return home in time to stop the rehearsal of the play Lover's Vows. I took the title from Henry Crawford's remark to Fanny, "I think if we had had the disposal of events—if Mansfield Park had had the government of the winds just for a week or two, about the equinox, there would have been a difference. Not that we would have endangered [Sir Thomas's] safety by any tremendous weather—but only by a steady contrary wind, or a calm. I think, Miss Price, we would have indulged ourselves with a week’s calm in the Atlantic at that season.” Click here for more about my books.

J.A. Downie, "Rehabilitating Sir Thomas Bertram," SEL Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Volume 50, Number 4, Autumn 2010, pp. 739-758

Published on April 21, 2021 00:00

April 18, 2021

CMP#39 Symbolism in Mansfield Park?

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. Disclaimer: To repeat something I mentioned at the beginning of this series of posts about Mansfield Park, "When I say I disagree that Mansfield Park is an anti-slavery novel, it does not mean I want to shut my eyes and ears and read my dear sweet Jane without troubling my conscience about the ugly underbelly of Regency England." I read Mansfield Park for its literary merit. I read about slavery in books that are actually about slavery.

Symbolism in Mansfield Park: Is the Novel Named after Lord Mansfield? Most any discussion or presentation about Mansfield Park includes a mention of how the title is a shrewd allusion to Lord Mansfield:"One of the first historicizations of Mansfield Park was Margaret Kirkham’s suggestion in 1983 that the name of the house, and village, was an allusion to the famous judge, Lord Mansfield.""Rightly, some of these readings connect Mansfield Park to the important slave trial after which Austen named it: the 1772 case of Somerset against Stewart, heard in the King’s Bench before Lord Mansfield, which freed the enslaved black man, James Somerset,from his master, Charles Stewart."Significantly, Lord Mansfield, the noted eighteenth-century jurist whose name is invoked by the title of Austen's novel, did more than lend his name to an important legal case on slavery...""She points out that the title of the novel alludes to Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, who stipulated in 1772 that slaves could not be forced to return from Britain to the Caribbean."

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, (1705 – 1793) As we can see, this connection started as a hypothesis but is now pretty much taken as a fact, along with the assumption that a reader in Austen's time who heard the name "Mansfield" would think "Lord Mansfield." And having thought of the former Lord Chief Justice, they would think of slavery. Perhaps. Perhaps a novel titled Marshall House would make people think of Thurgood Marshall.

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, (1705 – 1793) As we can see, this connection started as a hypothesis but is now pretty much taken as a fact, along with the assumption that a reader in Austen's time who heard the name "Mansfield" would think "Lord Mansfield." And having thought of the former Lord Chief Justice, they would think of slavery. Perhaps. Perhaps a novel titled Marshall House would make people think of Thurgood Marshall. Scholar Helena Kelly thinks that using the title might have been controversial -- might even have brought government attention down on Austen's head. Before the novel was published, Austen wrote in a note, "Keep the name to yourself. I should not like to have it known beforehand." Kelly wonders if this is a "sensible precaution in an age when pressure was often brought to bear on publishers to prevent politically or personally damaging material from ever seeing the light of day." But, if the title is a reference to Lord Mansfield, why would an allusion to a law established 40 years earlier be controversial, let alone dangerous? How does this supposed allusion enhance an anti-slavery message? Sir Thomas Bertram's elegant estate, funded by the proceeds of slavery, remains in the hands of the slave-holding family at the end of the novel (as opposed to being burned to the ground, or sold, or something). Fanny Price hates her parents' home in Portsmouth so much that she remembers Mansfield as the abode of "elegance, propriety, regularity, harmony... peace and tranquility." When she marries Edmund Bertram, everything within the sphere of Mansfield is "thoroughly perfect in her eyes."

So how is naming this elegant home after Lord Mansfield illustrative of anything? There are no consequences for the slavery and no-one expresses contrition or determination to change anything. Sir Thomas feels remorse over how he raised his daughters, not about being a slave-owner. (And as I will discuss, interpreting Sir Thomas as an utter villain destroys the narrative arc of the story.) What’s the point, exactly?

We must resort to irony. Austen actually means the opposite of what she says. Lord Mansfield's judgement hangs like a silent rebuke over the Bertram family. However, the Bertrams appear not to have noticed, any more than the critics. This inescapable allusion was first remarked upon in print about 170 years after the novel was published.

The Old Hall at Mansfield Woodhouse, by Jack Sims No other name of a family home (Pemberley, Hartfield, Rosings) in Austen has attracted similar scrutiny. Mrs. Elton's Bristol relatives in Emma, who are also associated with the slave trade, live at Maple Grove.

The Old Hall at Mansfield Woodhouse, by Jack Sims No other name of a family home (Pemberley, Hartfield, Rosings) in Austen has attracted similar scrutiny. Mrs. Elton's Bristol relatives in Emma, who are also associated with the slave trade, live at Maple Grove. It was not Austen's custom to use heavily significant personal names, although many other authors did. There is no Squire Allworthy, no Farmer Thoroughgood, no Wackford Squeers, no Snidely Whiplash, in any of her books. At most, you could say the upright, sensible women have good old-fashioned names, like Anne, Elizabeth and Elinor, and the shallow or trivial women have fancier names like Augusta, Isabella, Henrietta and Louisa.

When Austen first began to be studied intensively, scholars surmised that she took the title from some minor characters named Mansfield in Sir Charles Grandison, the favourite novel of her girlhood.

Professor E.J. Clery notes that an important patron of Henry Austen's bank lived at Mansfield Woodhouse in Nottinghamshire, which could have supplied Austen with key names for two of her novels. Perhaps she liked the name or it was a friendly shout-out to a important business associate of her brother. Personally, I find this suggestion convincing -- supposing that Austen took the name from anywhere, as opposed to choosing a good, solid English name that sounded well.

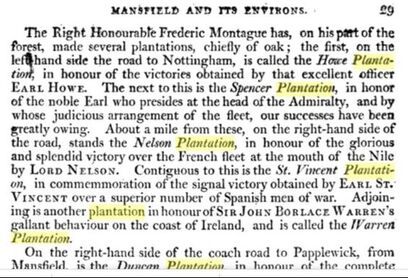

Another word used in Austen, which has strong negative connotations for us today, is the word "plantation." But in Austen's time, "plantation" simply meant land under cultivation. One scholar incorrectly asserts that Austen used "plantations" in the novel to refer to Sir Thomas's property in Antigua. She didn't. She uses "plantations" when she's referring to the cultivated forests around Mansfield Park which belong to Sir Thomas.

Another word used in Austen, which has strong negative connotations for us today, is the word "plantation." But in Austen's time, "plantation" simply meant land under cultivation. One scholar incorrectly asserts that Austen used "plantations" in the novel to refer to Sir Thomas's property in Antigua. She didn't. She uses "plantations" when she's referring to the cultivated forests around Mansfield Park which belong to Sir Thomas.Did readers in Austen's time automatically think of fields of toiling slaves when they saw the word "plantation"? I don't think so. An 1801 book about the history of the market-town of Mansfield, of which Mansfield Woodhouse is a part, uses the word "plantations" to refer to areas planted with trees, just as Austen uses the word in Mansfield Park. These plantations were named in honour of men whom modern critics would accuse of being warmongers and imperialists. Maybe the Right Honorable Frederick Montague was being ironic, too?

Likewise it is often asserted that Mrs. Norris, the odious, interfering aunt in the story, is named after John Norris, a slaver who is mentioned in Thomas Clarkson's history of the successful abolition of the slave trade, a book which Austen is known to have read.

Likewise it is often asserted that Mrs. Norris, the odious, interfering aunt in the story, is named after John Norris, a slaver who is mentioned in Thomas Clarkson's history of the successful abolition of the slave trade, a book which Austen is known to have read.Dr. Kelly also traces a connection to a prominent Anglican churchman named Henry Handley Norris (1771–1850). Norris was a leader of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and he feuded with the more evangelical Bible Society. This Rev. Norris was a High Church Tory at a time when the Church of England actually owned slave plantations in the West Indies.

It is interesting that Mrs. Norris, of all the characters in Mansfield Park -- in fact of all the characters in Austen -- talks the most about charitable activities. She's the only one who talks about the poor-basket (sewing clothes for poor people, a common activity for gentlewomen). She's the only one who talks about nursing servants when they're ill. When she talks about how much she worries about over-taxing the horses, or about poor old Wilcox's rheumatism, we know she is a Pharisee. Because yes, Austen did use irony a lot. There is no ambiguity around the question of whether Mrs. Norris is a warm-hearted person who cares about the poor basket and the servants. And we are certain about this because Mrs. Norris -- unlike Sir Thomas, the actual slaveowner -- gets her comeuppance.

Perhaps she is based on a real person, or inspired by some character trait in a real person. But are we supposed to think of slavery when we think of her? I said that a reference to Lord Mansfield's ruling, made 40 years before Mansfield Park was published, would not be controversial in 1814. But I can't say the same about a comparison of Fanny to a slave. It's true that some radical English writers did occasionally compare women, or the English working poor, to slaves. Mrs. Norris says, "I have been slaving myself till I can hardly stand, to contrive Mr. Rushworth’s cloak without sending for any more satin." But did Austen actually intend an allegorical comparison to chattel slavery? I don't think so.

The idea that Austen intended for us to see Fanny as a slave and Mrs. Norris as an overseer was first broached about 40 years ago. I think comparing downtrodden girls living in elegant mansions to enslaved Africans will become increasingly problematic in the future. Given the rapid evolution of academic discourse around race, this is not a comparison anyone will be comfortable making 40 years from now, perhaps not even one year from now. And insofar as the interpretation relies on the notion that Austen couldn't discuss slavery explicitly, well, that is just not the case -- writers of the time could and did discuss slavery explicitly, so that leg of the argument falls away. And if inductive theories about Austen ("this is what she really meant") can rise and fall, perhaps that means they were never definitive in the first place.

But, other candidates for symbolic references to slavery remain, including Fanny's amber cross on a chain, apricots, madeira and pheasants. Yes, pheasants.

Next post: Is Sir Thomas a villain? Did you know that Mrs. Norris gets her own backstory in JAFF (Jane Austen Fan Fiction)? She does, in Becoming Mrs. Norris, by Alexa Adams.

Published on April 18, 2021 15:16

April 14, 2021

CMP#38 Amelioration

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series.

Amelioration: What Fanny asked and Sir Thomas answered

As discussed in my previous post, Sir Thomas Bertram was an educated man, and a member of Parliament. He would have been thoroughly familiar with the slavery debate as it played out in Parliament and the press in the decades leading up to the evening that. He would have known the many arguments pro and con. He was also almost certainly a slaveowner.

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series.

Amelioration: What Fanny asked and Sir Thomas answered

As discussed in my previous post, Sir Thomas Bertram was an educated man, and a member of Parliament. He would have been thoroughly familiar with the slavery debate as it played out in Parliament and the press in the decades leading up to the evening that. He would have known the many arguments pro and con. He was also almost certainly a slaveowner. In Chapter 21 of Mansfield Park, Fanny Price asks her uncle Sir Thomas a question about the slave trade, a question he answers. (Previous posts about this passage here and here). We know that Fanny showed interest and pleasure in his answer to her question. So what could that question have been, and what was the answer?

I think scholar George Boulukos gives a plausible answer: the question had to do with amelioration.

"Amelioration" means improving the living and working conditions of enslaved persons. Examples of benevolence include: not separating families, giving them their own little plots of land to cultivate in their spare hours, and converting them to Christianity. Disclaimer: My motive in this post is to explain, not to excuse.

I am sharing what I have learned about the slavery debate.

However -- and it must be the contrarian in me -- I don't feel compelled to assure anyone that the views of 18th-century abolitionists are not nearly so enlightened as my own.

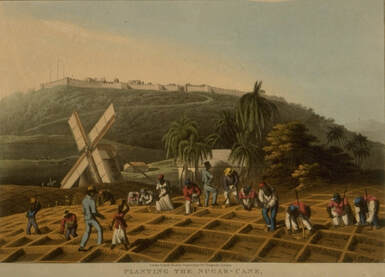

Idealized view of life in the West Indies Experts generally agree that Mansfield Park is set in the years after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 (slavery itself was not abolished in British territories until 1833). When Fanny asked her question, the British Navy was patrolling the waters off Africa, attempting (with mixed success) to capture slave ships setting out across the Atlantic. Ending the slave trade, in other words, was official government policy when Mansfield Park was published. Furthermore slavery was widely disputed, written and talked about in England at this time. (For this reason, as I've mentioned before, the notion that it was risky or courageous for Austen to mention slavery in her novel is just not accurate).