Lona Manning's Blog, page 19

September 16, 2021

CMP#71 Sleath and Slavery

CMP#71 "Other Subjects of Discourse:" Sleath on Slavery

CMP#71 "Other Subjects of Discourse:" Sleath on Slavery

Unattractive caricatures In my mini-series on Mansfield Park and the topic of slavery, I shared examples of authors of Austen's era who were far more explicit about slavery

than Austen

. More recently, I came across the 1809 novel The Bristol Heiress by Eleanor Sleath and was curious to read it because it was about an heiress from Bristol. Bristol was notorious as a place where fortunes were made from the slave trade and related industries.

Unattractive caricatures In my mini-series on Mansfield Park and the topic of slavery, I shared examples of authors of Austen's era who were far more explicit about slavery

than Austen

. More recently, I came across the 1809 novel The Bristol Heiress by Eleanor Sleath and was curious to read it because it was about an heiress from Bristol. Bristol was notorious as a place where fortunes were made from the slave trade and related industries.While slavery does not play a role in the plot of The Bristol Heiress, two other families derive their wealth directly or indirectly from the slave trade, and another character gets a fortune from a rich relative in the East Indies. (For more about colonial wealth as a plot device, see this post.)

I outline the plot of The Bristol Heiress here. I discuss the similarities to Northanger Abbey here. It's main theme is the moral pitfalls arising out of faulty education. But because the references to slavery in the book are both so jarring and so telling, I saved this topic to discuss separately.

If you'd like to read a fictional conversation about slavery published in 1809 which represents different points of view, including the point of view of a plantation-owner, read on. If you think it would distress you more than inform you, please don't read it. I have left out the worst of the worst.

This conversation takes place in the "saloon" with the ladies, after the ladies and gentlemen have separated after dinner. The characters that author Eleanor Sleath brings together in the saloon are:Mrs. Trevallian, the wife of a wealthy West Indian planter who has recently returned to England “with all that showy magnificence usually displayed by those who, having suddenly become rich, are anxious to impress others;”Mrs. Wilkinson, a Bristol fabric merchant's wife, who is “ignorant, ill bred… [and] possessed of an intolerable share of confidence and self-conceit;”Lady Harcourt, a proud London aristocrat who is heavily in debt;Caroline Percival, the beautiful young heroine of the book. Her father is the host of the dinner party and he's still at the dining-table with the gentlemen. Caroline is the youngest person in the conversation and she is under Lady Harcourt's sway and tutelage; andan unnamed lady.

Old Maiden Lady The conversation starts with Mrs. Trevallian bragging about her life back in the West Indies: "her extensive rooms, her costly carpets, and her gilded sofas, the number of her carriages, of her servants; her train of black slaves …” She boasts to the aristocrat: “''You would be charmed, my dear Lady Harcourt, with that enchanting island, where money, you know, can procure one everything tasteful and elegant from London, without being incommoded by the English impertinence of one’s attendants.'”

Old Maiden Lady The conversation starts with Mrs. Trevallian bragging about her life back in the West Indies: "her extensive rooms, her costly carpets, and her gilded sofas, the number of her carriages, of her servants; her train of black slaves …” She boasts to the aristocrat: “''You would be charmed, my dear Lady Harcourt, with that enchanting island, where money, you know, can procure one everything tasteful and elegant from London, without being incommoded by the English impertinence of one’s attendants.'”Lady Harcourt, though very irritated, says nothing because a "description of her own house and establishment, splendid as it was, would appear insignificant, after that of Mrs. Trevallian.... A mortified silence, therefore, succeeded on the part of Lady Harcourt, which was interrupted… by Mrs. Wilkinson’s demanding of Mrs. Trevallian, whether she could abide to be waited upon by those blacks she had mentioned?”

“'Frightful creatures!' [says Mrs. Wilkinson] ''I would rather die than take any thing from their hands, for I am sure they are not the same flesh and blood as we are.'”

“'Dear Mrs. Wilkinson,' cried a stiff maiden-lady of about five-and-fifty, who was known to be a great reader, and who, though she had never before spoke, had paid great attention to Mrs. Trevallian’s relation, 'I wonder you can talk so; you forget, it seems, that they are all God’s creatures as well as we are, and that they are only distinguished from us by a difference of colour.'”

Mrs. Wilkinson and Mrs. Trevallian both deny the equality of black people, and Mrs. Trevallian adds, "'I am much surprised our legislators should be absurd enough to suppose them otherwise,'” a reference to the on-going Parliamentary debates around the abolition of slavery. (This book was published two years after the abolition of the slave trade, but not the abolition of slavery in British territories.)

“'But you will allow, Madam,' said Caroline, who had felt a sensation little short of horror, on hearing Mrs. Trevallian express herself in a manner so unfeeling towards these unfortunates of the human race, 'that their treatment has been sometimes very cruel…”

The plantation-owner’s wife protests that reports of the harsh treatment have been exaggerated and furthermore, harsh treatment is necessary. She refers to enslaved persons as "poor wretches" but adds "'severity is the only discipline that can be used with effect'" because without the use of force, "'whence must we procure our sugars, and a thousand other necessaries? Where all our comforts, all our luxuries?'”

“'Where indeed?'” echoes Mrs. Wilkinson, declaring she wouldn’t give up sugar “'for all the black-a-moors in the kingdom.'”

"The old maiden-lady, who had first undertaken to defend the cause of humanity, darted a look of severe contempt at Mrs. Wilkinson, and then, addressing herself to a lady who sat next her, she entered with her into a discussion on the merits of a new novel, which continued till coffee was brought in, when the entrance of the gentlemen, and the arrangement of card-tables, led to other subjects of discourse."

These other subjects of discourse include playing cards for high stakes, and the affectation of learning Italian.

Servant in livery There is a second, brief, allusion to the West Indies in Volume I.

Servant in livery There is a second, brief, allusion to the West Indies in Volume I.Mrs. Trevallian complains again about the insolence and independent spirit of English servants. “'a dismissal from our service is the only punishment we can inflict. How different is the situation of those menials who are doomed to attend us abroad! A woman may there be said to reign with an absolute dominion… her power is uncontrolled, her will her only law.'"

Lady Harcourt snaps back that she "‘had rather enjoy a limited, yet secure government in my own country, over free men, than an arbitrary, yet dangerous one, in the West Indies, over a wretched parcel of negro slaves.'” (By "government," she means her own authority over her servants and by "dangerous," she is referring to the possibility of a slave uprising.)

Caroline's father cheerfully supposes that Caroline will have at least one black servant to attend her after she makes a good marriage, in addition to "half a dozen European ones, with gold-laced liveries."

There is a lot more for academics to work with in these conversations from The Bristol Heiress than a "dead silence" in Austen. Lady Harcourt, Mrs. Wilkinson and Mrs. Trevallian are portrayed as contemptible people in this conversation, and they are portrayed as contemptible people whenever they appear in the book. The reader is not expected to pass over what they say with indifference. On the other hand, this conversation, as I mentioned, is far from being a focus of the book. It's just another proof that these ladies are contemptible. Lady Harcourt is contemptible because she is a haughty aristocrat who doesn't pay her bills and who lives only for fashion and society. Mrs. Wilkinson and Mrs. Trevallian have been granted a place in the social pecking order because they are rich, but we are invited to look down on them first and foremost because they are vulgar social climbers with lots of money but no breeding. Looking at the conversation about slavery in this context, we see that their attitude toward slavery is presented as an example of their vulgarity.

The two characters who speak in defense of enslaved persons are Caroline and the "old maiden-lady." Caroline is a young person still making her way in society and she is shown as being tender-hearted and appalled by what she is hearing. But what about the "stiff maiden lady" who "had undertaken to defend the cause of humanity?" In my opinion, the character of the "stiff maiden lady" is not a particularly flattering one. Why does Sleath specify that she is "stiff" and "old" and unmarried? She is "known to be a great reader." Perhaps this is a suggestion that she parrots her ideas from books.

Sleath does not even bother to give her a name, and she does not appear anywhere else in the five volumes of The Bristol Heiress. Perhaps she, too, represents a stock character, the Abolitionist do-gooder who is as much a object of satire as the planter's wife. I get the feeling that this is a portrait that Sleath's contemporary readers were expected to recognize.

I also think this conversation could be usefully compared to the brief exchange between Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Elton, the Bristol merchant's daughter, in Emma. I think the character of Mrs. Elton is derived from the stock character of the vulgar Bristol merchant's wife who appears in this and other novels. Mrs. Elton is also "possessed of an intolerable share of confidence and self-conceit."

I have found only one reference to The Bristol Heiress in the current academic literature, and it is a reference to the use of the word 'verandah.' I think an examination of this conversation, by these characters, would be useful. The conversations cited are from Volume I of The Bristol Heiress by Eleanor Sleath, pps 42 to 48 and 140 to 142. For another example of a vulgar Bristol merchant's wife, see Mrs. Ludford in Charlotte Smith's Ethelinde. Click here for the introductory post in my "Clutching My Pearls" series. For more about Mansfield Park, click on "Mansfield Park" in the menu to the upper right. For more about obscure female writers such as Eleanor Sleath, click on "Authoresses."

The campaign to boycott sugar was called the Anti-Saccharite campaign. I reference it in my novel, A Contrary Wind. One of my characters, the widow of a Bristol ship-builder, refuses to serve sugar at her tea table. Click here for more about my books.

Published on September 16, 2021 00:00

September 13, 2021

CMP#70 Austen and the Test of Time

CMP#70 Austen and the Test of Time: "It Ain't Just About Being Old."

CMP#70 Austen and the Test of Time: "It Ain't Just About Being Old."

A prominent and influential educator recently tweeted: “Did y’all know that many of the ‘classics’ were written before the 50s? Think of U.S. society before then and the values that shaped this nation afterwards. THAT is what is in those books. That is why we gotta switch it up. It ain’t just about ‘being old.’”

A prominent and influential educator recently tweeted: “Did y’all know that many of the ‘classics’ were written before the 50s? Think of U.S. society before then and the values that shaped this nation afterwards. THAT is what is in those books. That is why we gotta switch it up. It ain’t just about ‘being old.’”Twitter doesn’t allow for nuance, so I am going to assume this educator is in fact aware that we don’t read books just because they are old, despite the fact that she actually says, “It ain’t just about ‘being old.’”

I knew there were plenty of novels published in Jane Austen’s day, but I didn't know there were hundreds and hundreds of novels. Over the decades, the others have fallen away, and Austen’s works remain standing. The test of time takes time.

Just a handful of the many novels published in 1812 The immortals and the others

Just a handful of the many novels published in 1812 The immortals and the others Jane Austen's nephew wrote about his aunt's modest reputation in his lifetime: "Sometimes a friend or neighbour, who chanced to know of our connection with the author, would condescend to speak with moderate approbation of Sense and Sensibility, or Pride and Prejudice; but if they had known that we, in our secret thoughts, classed her with Madame D’Arblay or Miss Edgeworth, or even with some other novel writers of the day whose names are now scarcely remembered, they would have considered it an amusing instance of family conceit. To the multitude her works appeared tame and common-place, poor in colouring, and sadly deficient in incident and interest."

George Howard, Earl of Carlisle, an early fan of Austen's, wrote the following tribute in 1835. Addressing a female reader, Howard writes:

Beats thy quick pulse o'er Inchbald's thrilling leaf,

Brunton's high moral, Opies's deep wrought grief?

Has the mild chaperon claimed thy yielding heart,

Caroll's dark page, Trevelyan's gentle art?

Or is it thou, all perfect Austen? Here

Let one poor wreath adorn thy early bier

That scarce allowed thy youth to claim

Its living portion of thy certain fame

Every other author mentioned above would be known today to very few; only to people who specialize in reading 18th century literature. Everyone knows Jane Austen's name.

It ain't just about being old. It's about being excellent.

Excellent or not; it's interesting

Excellent or not; it's interesting

One consequence of this winnowing-out of hundreds of other 18th century authors, is that we don’t read Austen in the same context and we do not make the same comparisons her first readers did. Except for scholars and other aficionados of 18th century novels, we don’t read the books Austen read. (Those of us who do, most likely picked up the bug after reading Austen.) As I've discussed in previous posts, many talk about Austen's focus on money or social class as though this was something unique to her, when it wasn't.

I have been delving into these now-obscure authors and sharing my discoveries and thoughts on this blog. I've been learning about recurring novelistic tropes such as (death, coincidence , misunderstanding and rich uncles ) and I've met some stock characters .

I first began reading these obscure books to research the question: "Was it controversial or dangerous to discuss slavery back in Jane Austen's time?" I suspected the answer was "no," but I wanted to check for myself. (The answer is indeed "no"). For those who read literature for social history, I have found many authors who were more explicit about social issues than Austen was. Within the pages of these novels I've found authorial voices speaking out against slavery , dueling, gambling, corrupt aristocrats, forced marriage, the military establishment, cock-fighting, religious fanaticism, and a host of social evils and excesses. Within these pages, I've learned more about how our values have evolved.

And I've read opinions which would jar on modern sensibilities. I've wondered if these authors were reflecting widely-held ideas or if they were censoring themselves in some respects. Speaking of the "values" that are in these "old books," did anyone seriously expect young women to behave like "perfect heroines" in real life?

I have learned about authors whose life stories--insofar as we know their life stories from the scanty records--are inspiring and touching.

But, in case you were wondering, I haven't yet found a forgotten author whose talent, in my opinion, approaches Austen. I love historical fiction and I love bringing history into my fiction. My Mansfield Trilogy touches on the amazing changes that were happening during Austen's time--the uprising of the Luddites at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the fight for autonomy for women, the coming revolution of steam power, the creation of societies to fight slavery and assist the working poor. Click here for more about my books. Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series. For more about obscure authors of Austen's era, click on the "Authoresses" category in the right-hand menu.

Published on September 13, 2021 00:00

September 9, 2021

CMP#69 The Bristol Heiress, part two

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath.

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath. For more posts about now-obscure 18th century authors, click the category "Authoresses" to the right CMP#69 I'll See Your Three Volumes and I'll Raise You Two More

Nobleman seeks rich merchant's daughter for matrimony In

my last post

, I shared some similarities between an 1809 novel, The Bristol Heiress, and Northanger Abbey. Most of the Austenesque coincidences came in the first and second volume of The Bristol Heiress. There's a lot more novel to get through. Spoilers ahead!

Nobleman seeks rich merchant's daughter for matrimony In

my last post

, I shared some similarities between an 1809 novel, The Bristol Heiress, and Northanger Abbey. Most of the Austenesque coincidences came in the first and second volume of The Bristol Heiress. There's a lot more novel to get through. Spoilers ahead!This novel features the popular themes of: (1) faulty education for girls and (2) London as a sinkhole of vice

Caroline Percival, our heroine, is the daughter of a rich but low-born (ie merchant family) mother and a well-born banker. The wife's money is necessary to the plot, but she isn't, so she's dispatched at the beginning of the novel. The father sends his only child, Caroline, to a boarding school in London to learn from the best masters. She grows up to be a beauty and she's taught all of the basic ladylike accomplishments. Her aristocratic aunt Lady Harcourt takes her up. Dad is thrilled because with Lady Harcourt to escort her around London society, Caroline has a good chance of making a brilliant match.

Decadent Lady Harcourt fastens on dad like a parasite, telling him he has to build a mansion and buy expensive clothes and jewels for his daughter, but a lot of the money goes into her pocket. Although Mr. Percival's fondest dream is to see his daughter with a coronet on her head, he lets the handsome but poor young clergyman Mr. Griffiths escort his lovely young daughter around the countryside every day to give her painting and sketching lessons. Of course the young people fall in love, but he can't speak because of the wealth gap between them and she won't admit her love because her ambition is to marry a rich aristocrat.

"Methodist Parson, Stark Mad!" After going to London with Lady Harcourt, Caroline makes a sensational debut with the ton and attracts the attention of a number of suitors, but dad and Lady Harcourt hold out for the best offer--from the son of an Earl who is in the market for an heiress-bride. Caroline also meets an assortment of selfish and unlikeable people. Her aunt hosts nightly card games at which everybody loses money. In other words, London society is presented as a venal and unpleasant world where everyone is obsessed with appearances. Yet, this is where everybody wants to be, including Caroline.

"Methodist Parson, Stark Mad!" After going to London with Lady Harcourt, Caroline makes a sensational debut with the ton and attracts the attention of a number of suitors, but dad and Lady Harcourt hold out for the best offer--from the son of an Earl who is in the market for an heiress-bride. Caroline also meets an assortment of selfish and unlikeable people. Her aunt hosts nightly card games at which everybody loses money. In other words, London society is presented as a venal and unpleasant world where everyone is obsessed with appearances. Yet, this is where everybody wants to be, including Caroline.Then things go badly for our heroine; dad loses all his money in a bank failure and dies. The engagement is called off, and Lady Harcourt even kicks Caroline out of the house. As with other novels of this type, (such as Ethelinde) this means she has to go and live with other various disagreeable relatives, including an aunt who is being preyed upon by a Methodist preacher who is really just a grifter. (I've recently read several novels with unflattering portraits of Methodists and puritans, so this will be another future blog post).

Caroline is not a "picture of perfection" heroine. At several points in the novel, she has the chance to turn her back on worldly ambition and marry the young clergyman Mr. Griffiths, and every time, she rejects him in favour of the pursuit of wealth. The dramatic tension in the story arises out of her fruitless quest for happiness through vain and worldly pleasures.

There is also a subplot about a " picture of perfection " heroine named Matilda, her brother Darnley, and her long-lost husband. This subplot starts when Caroline is riding around London with her friend Lady Mary. In a heavy-handed scene, Lady Mary is distraught when her dog's leg is injured but indifferent when her carriage rolls over a little child in the street and breaks his leg. Caroline goes back a few days later to enquire if the child is all right and meets Matilda, a beautiful and well-born lady who is down to her last shilling. While she calls herself 'Mrs.," the landlady is skeptical and hence rude to her. Caroline also isn't sure if she should give charity to a fallen woman, let alone be in the same room with her, but she helps out for the sake of the lovely little boy. In time we learn Matilda's mysterious backstory and through a string of amazing coincidences, which are handled very briskly in comparison to the main plot, Matilda is happily reunited with her husband and her brother. This is one of those plots which would never work today in our modern age with cell phones and email. Romeo to Juliet: U dead? Juliet: Lolz No!

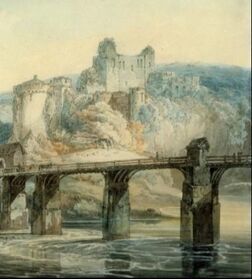

Chepstow Castle, detail, Turner, 1793 Meanwhile, Caroline manages to captivate Lord Castleton, a very wealthy but older nobleman. But we're just at volume 4 and there's another volume to go. More tribulations and misunderstandings follow.

Chepstow Castle, detail, Turner, 1793 Meanwhile, Caroline manages to captivate Lord Castleton, a very wealthy but older nobleman. But we're just at volume 4 and there's another volume to go. More tribulations and misunderstandings follow.Volume 5 is padded out with a segment set in an old castle in Wales, where Caroline has been banished when her husband suspects her of infidelity. Caroline hasn't been unfaithful, but she has been vortexing -- that is, getting caught up in the London social whirl, losing money at the card table, flirting too much. A jealous rival, Miss Moreland, manages to plant suspicions in her husband's mind. While there, Caroline comes across an old manuscript which I've excerpted below; a gothic tale which is a complete break from the main narrative.

With the help of the clergyman of the parish (what a coincidence, it's Mr. Griffith!), the misunderstandings are cleared up. Then everybody goes travelling. We have a travelogue about Wales and a digression on the poet Ossian . Finally we see Caroline--and basically everybody else--happy. Plus Miss Moreland gets religion and dies, and the evil Lady Harcourt gets her comeuppance but Caroline graciously forgives her.

I do think Eleanor Sleath was playing with our expectations a bit when Caroline didn't end up with the handsome clergyman from Volume I. Is Sleath subverting the typical marriage plot? We don't even meet Lord Castleton until Volume 4 and he's not a young romantic hero. He is a bit of a hypochondriac and very strait-laced. He does learn however, that he is happiest when he is fulfilling his responsibilities to his tenants and to his fellow man. Caroline wasn't really cut out for life as a clergyman's wife, so all's well that ends well.

The Awakening Conscience (detail) by Hunt, 1853 Sleath concludes: “Let those, then, who have endeavoured, like [our heroine], to win the phantom, worldly enjoyment, through the mazes of dissipation and luxurious indulgence, learn from her history to see that wealth and splendour can only be valuable when usefully applied—that a life devoted to fashionable pleasure is a life of labour, vexation, and pain—and that true satisfaction and sound enjoyment can only be expected and found in such pursuits as are founded upon good sense and wisdom, resting upon such principles as religion may dictate, and sound morality approve.”

The Awakening Conscience (detail) by Hunt, 1853 Sleath concludes: “Let those, then, who have endeavoured, like [our heroine], to win the phantom, worldly enjoyment, through the mazes of dissipation and luxurious indulgence, learn from her history to see that wealth and splendour can only be valuable when usefully applied—that a life devoted to fashionable pleasure is a life of labour, vexation, and pain—and that true satisfaction and sound enjoyment can only be expected and found in such pursuits as are founded upon good sense and wisdom, resting upon such principles as religion may dictate, and sound morality approve.”To return to the consideration of money and class in books of this sort, it seems to me that this is a kind of "have your cake and eat it too" story. We read many details about lavish wealth and the high life in London, and both of our heroines end up rich, but at the same time the author assures us that money does not bring happiness.

I do not see the treatment of money and class in The Bristol Heiress as representing a critical examination of social class in England, I see it as a book written to meet the prevailing tastes of a middle-class audience who are fascinated with a lifestyle they want to vicariously live while at the same time condemn. The poems supposedly by Ossian, a mythic Gaelic bard, are now generally thought to have been written by James MacPherson (1736–1796). The debate over whether Ossian's poems were genuine or fabricated was a hot topic at the time.

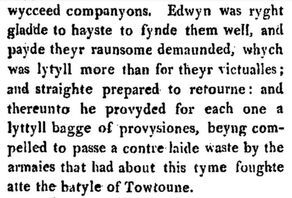

Eleanor Sleath also tried her hand at some old timey language in the fifth volume of The Bristol Heiress, when she threw in a short story for the heroine to read about a medieval lady in distress during the Wars of the Roses. More about Eleanor Sleath (1770-1847) at the "SleathSleuth" website.

excerpt from The Bristol Heiress, Vol. 5, p. 164 In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford is attracted to Edmund Bertram, but she doesn't want to be a clergyman's wife in a small English village; she wants to live in London, which would more than what their "incomes united could authorise." If Mary wants a better lifestyle, she needs to find a richer husband. In my Mansfield Trilogy, I explore the possibility, what if Mary and Edmund did get married?

Click here for

more about my books. Click here for the introductory post in the "Clutching My Pearls" blog series.

excerpt from The Bristol Heiress, Vol. 5, p. 164 In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford is attracted to Edmund Bertram, but she doesn't want to be a clergyman's wife in a small English village; she wants to live in London, which would more than what their "incomes united could authorise." If Mary wants a better lifestyle, she needs to find a richer husband. In my Mansfield Trilogy, I explore the possibility, what if Mary and Edmund did get married?

Click here for

more about my books. Click here for the introductory post in the "Clutching My Pearls" blog series.

Published on September 09, 2021 00:00

September 5, 2021

CMP#68 The Bristol Heiress, part one

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath.

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath. First, some coincidences between this novel and Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey. Then, a bit about the author, and a real-life Bristol heiress.

For more posts about now-obscure 18th century authors, click the category "Authoresses" to the right. CMP#68 Caroline and Catherine, a tale of two heroines

In

my last blog post

, I looked at some 18th-century novels which scholars say might have influenced Jane Austen in terms of characters, themes, or plot points. Here's an example of some things that could have served as inspiration but must surely be a coincidence--what do you think?

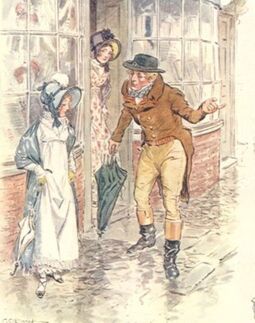

In

my last blog post

, I looked at some 18th-century novels which scholars say might have influenced Jane Austen in terms of characters, themes, or plot points. Here's an example of some things that could have served as inspiration but must surely be a coincidence--what do you think?In volume I of The Bristol Heiress, Mr. Griffiths, a charming and handsome young clergyman, goes walking with the heroine and her friend. He points out the beauties of the landscape to them. Later, he also explains the principles of drawing and perspective to the young heroine--just like Henry Tilney. In Northanger Abbey, Catherine Moreland "confessed and lamented her want of knowledge," so Henry Tilney "talked of foregrounds, distances, and second distances—side-screens and perspectives—lights and shades." Caroline Percival, the Bristol heiress, “knew little of design, and less of colouring; and in the arts of grouping and perspective, she was strangely deficient. Mr. Griffiths "united a thorough knowledge of the science and a thorough fondness for it."

In Volume II of The Bristol Heiress, when Caroline comes to London, she is young and naïve, and sometimes asks herself if the behaviour of her wordly new acquaintances is proper. She meets a social butterfly named Miss Wilmore who says things like "I hate dress and I never care what I wear," and then covets the heroine's necklace, calling it "the sweetest, most enchanting thing I ever saw!" She complains of being admired by passing men: “Dear me, how shockingly impertinent these creatures are! they can never see any thing decent but they must stare so horridly, I’m sure it’s very rude; I declare if I an’t quite out of countenance.” Does that remind you of anybody, Northanger fans?

Northanger Abbey's Isabella Thorpe says: "For heaven’s sake! Let us move away from this end of the room. Do you know, there are two odious young men who have been staring at me this half hour. They really put me quite out of countenance."

A secondary character in the novel is named Miss Moreland, though she is a foil for the heroine, not the heroine herself. The author of The Bristol Heiress and Henry Tilney's sister share a first name: Eleanor.

Yet, how could The Bristol Heiress have influenced Northanger Abbey?

Yet, how could The Bristol Heiress have influenced Northanger Abbey? As we know , Jane Austen's manuscript for Northanger Abbey, then called Susan, had been sold to the publisher Benjamin Crosby in 1803. He didn't publish it, she wrote to him about it in 1809 and she finally bought it back from him in 1816. We know there had to have been some revisions. She changed the heroine's name and hence the title of the book. Scholars surmise that she dropped the name "Susan" because another book of the same name had come out recently. She added a mention of Maria Edgeworth's book Belinda, which was published in 1801 while Susan sat on the shelves at the publisher's.

But we do not know to what extent Austen made other revisions. She was still apparently unsatisfied with it, and worried that the entire idea of a spoof on gothic novels was now dated, even "obsolete."

Northanger Abbey is the only novel for which Austen wrote a preface and it is just a very brief author's note. (More typically, an author's note of this period would ask the public's indulgence, ie, to please give the book a kind reception, along with an assurance that the story upholds the highest moral standards, and does not give a sanction to vice. Austen evidently felt she could forego this practise.)

In her note, Austen took a little jab at Crosby without naming him, writing: "This little work was finished in the year 1803, and intended for immediate publication. It was disposed of to a bookseller, it was even advertised, and why the business proceeded no farther, the author has never been able to learn. That any bookseller should think it worth-while to purchase what he did not think it worth-while to publish seems extraordinary."

She added, "the public are entreated to bear in mind that thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes."

Although Austen wrote this brief preface, she obviously still had doubts about publishing the book, and put it back on the shelf. It was not published until after her death in 1817.

So, unless one surmises that some or all of the similarities in The Bristol Heiress that I mentioned above were only added to the manuscript after Austen got it back the year before she died, there is no way that The Bristol Heiress could have influenced Northanger Abbey. Likewise, there is no way Northanger Abbey could have influenced The Bristol Heiress because in 1809, the manuscript was sitting on a shelf and Eleanor Sleath could not have seen it. Eleanor Sleath's novel was published by Lane, Darling & Co. It would have been quite tantalizing if it had been published by Crosby & Co., that is, brought out by the publisher who held the unpublished manuscript of Susan on its shelves, but it was not.

We do know that Austen read, or was familiar with, another book by the author of The Bristol Heiress -- the gothic thriller The Orphan of the Rhine (1798). It is one of the seven horrid novels that Isabella Thorpe recommends to Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey! First editions of The Bristol Heiress and the Orphan of the Rhine are exceedingly rare. A copy of each survived in the library of an eccentric German aristocrat, known today as the, available through university libraries with a digital subscription. The Orphan of the Rhine has been republished in modern editions because of its connection to Northanger Abbey.

We do know that Austen read, or was familiar with, another book by the author of The Bristol Heiress -- the gothic thriller The Orphan of the Rhine (1798). It is one of the seven horrid novels that Isabella Thorpe recommends to Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey! First editions of The Bristol Heiress and the Orphan of the Rhine are exceedingly rare. A copy of each survived in the library of an eccentric German aristocrat, known today as the, available through university libraries with a digital subscription. The Orphan of the Rhine has been republished in modern editions because of its connection to Northanger Abbey.I haven't read the Orphan but here is a discussion of it by Ellen Moody, who wrote the foreword for a 2014 re-issue.

The scholars Rebecca Czlapinski and Eric C. Wheeler have pointed out that Catherine Morland mentions the very gothic names "Laurentina" and "St. Aubin" from the Orphan when she talks to Isabella Thorpe. Click here for a pdf chapter of their discussion of the Northanger--Orphan connection, along with a biography of Eleanor Sleath.

Rebecca Czlapinski's research into the interesting life story of Eleanor Sleath (1770-1847) is also available at her website SleathSleuth. Sleath was left in debt and with a baby boy after her husband died and later in life there were rumours about her and a married clergyman. Looks like the rumours were true.

Most of Sleath's novels were gothic novels. The Bristol Heiress is a sentimental novel with a short gothic tale interjected into the fifth volume, which I'll discuss briefly in the next post. The real-life Bristol Heiress

I had wondered if the Bristol Heiress novel owed anything to the real-life Bristol heiress, Clementina Clerke, whose elopement—or abduction—from a Bristol boarding school caused a sensation in 1791. She is a real-life example of someone who inherited a West Indian fortune from a rich uncle. You can read the true story here at Naomi Clifford’s website. I also came across a reference to a portrait of Clementina Clerke painted by the artist Samuel Woodforde but have been unable to find this portrait online.

The rich uncle was a common figure in 18th-century novels, very often an offstage character, who conveniently dies and leaves a large fortune. Eleanor Sleath uses this handy solution for one of her minor characters in The Bristol Heiress. We learn that: “A friend of Darnley’s, hang the fellow for his good luck, an East Indian Director, a collateral branch of his own family, lately deceased, has left him, with the exception of a few legacies, his sole heir; and his property, on a very moderate calculation, is supposed to amount to above eighty thousand pounds.”

But I see no connection between Caroline and Clementina.

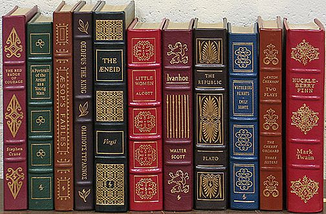

The Errors of Education

The Errors of EducationThe Bristol Heiress, or The Errors of Education by Eleanor Sleath was published in 1809. The subtitle makes it clear that this is a story about the consequences of not educating your daughters properly. Many books of this period take up this theme, including Austen's Mansfield Park. Sleath's tale received a good review, although the first sentence must have caused Sleath a little bit of alarm when she read it. It starts with a sneer: “This is one of those numerous publications which issue almost daily from the press, striving, seemingly in vain, to sate the appetite of the public for novels and romances.” But then the reviewer goes on to say: “It were greatly to be wished that all compositions of this kind were calculated, like the present work, to inculcate some useful truth; for then that class of readers, who take up a book merely for the most indolent exercise of the attention, would often be betrayed into instruction, and pass their hour with at least the possibility of receiving some benefit.” This is the highest praise a reviewer of the day could bestow: commending the novel for its moral value.

“The authoress of this work undertakes to shew, that those persons are greatly mistaken who educate their daughters wholly with a view to fashionable life: for that happiness does not consist in splendid pleasures, but rather in the rational exercise of the benevolent affections. This is exemplified in the history of Caroline Percival, the daughter of a banker at Bristol, a person of an ancient but decayed family, who had himself risen to opulence through his marriage with the daughter of a tradesman, and was now eagerly anxious to raise his only daughter… into the first ranks of the gay and fashionable world."

More about the plot of The Bristol Heiress in my next post.

Published on September 05, 2021 00:00

August 31, 2021

CMP#67 Austen Antecedents

One Evening in December as my Father, my Mother and myself, were arranged in social converse round our Fireside, we were on a sudden greatly astonished, by hearing a violent knocking on the outward door of our rustic Cot.

One Evening in December as my Father, my Mother and myself, were arranged in social converse round our Fireside, we were on a sudden greatly astonished, by hearing a violent knocking on the outward door of our rustic Cot.My Father started—“What noise is that,” (said he.)

“It sounds like a loud rapping at the door”—(replied my Mother.)

“it does indeed.” (cried I.)

“I am of your opinion; (said my Father) it certainly does appear to proceed from some uncommon violence exerted against our unoffending door.”

“Yes (exclaimed I) I cannot help thinking it must be somebody who knocks for admittance.”

“That is another point (replied he;) We must not pretend to determine on what motive the person may knock—tho' that someone DOES rap at the door, I am partly convinced.”

--- Love and Freindship, Jane Austen (juvenilia) CMP#67 The Antecedents of Austen: or, Chance or Design?

Before Jane Eyre on the moor, there was Louisa My article in

the current issue

of Jane Austen's Regency World magazine discusses the similarity of two distinct plot points in Austen's unfinished novel Sanditon that also occur in the 1796 novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest.

Before Jane Eyre on the moor, there was Louisa My article in

the current issue

of Jane Austen's Regency World magazine discusses the similarity of two distinct plot points in Austen's unfinished novel Sanditon that also occur in the 1796 novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest. Jane Austen’s characters and stories are so beloved that some of her devotees might think it treasonous to suggest that she drew inspiration and ideas from other novelists. Her own voice is so distinct and her genius shines so bright. We discuss her literary creations as though they are living, breathing people. How could anyone think that Austen draw on other writers for plot ideas and characters?

Many scholars do think so. And of course, we know she lampooned existing novels for her juvenile parodies. For example, the opening of Elizabeth Helme's 1789 novel Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor, is parodied in Austen's hilarious juvenile work Love and Freindship.

Helme's story begins: On a frosty night, the latter end of December (when the mild radiance of the moon, to a mind at ease, might have made even this rough scene delightful)--the inhabitants of the cottage were disturbed by a loud knocking, which was answered by a female voice, who from a window in the upper story demanded the reason of this late alarm!

Who knows, perhaps the idea of a heroine wandering on the moor and ending up at a lonely house inhabited by poor but honest genteel folk inspired more than one novel.

Northanger Abbey parodies the trope of gothic novels. But scholars think Austen did more than laugh at novels. Some scholars have pointed to Charlotte Smith's Celestina (1791) and The Old Manor House (1783) as forebears of Mansfield Park. Sarah Burney’s Clarentine (1796) also features a dependent niece and a cruel, domineering aunt who is concerned that Clarentine will marry her cousin. As well, Clarentine is pursued by a Henry Crawford-type of character who comes to visit her after she leaves the equivalent of Mansfield Park and goes to live by the seashore. (I discussed and compared Clarentine and Fanny Price in previous posts).

It is widely thought that Elinor and Marianne Dashwood are partly inspired by the sisters Louisa and Marianne in Jane West’s A Gossip’s Story (1796).

Scholar Jocelyn Harris has turned up possible inspirations for Persuasion. A girl is harassed by a little boy climbing on her back and she can’t get him off without help in The Wanderer (1814). This reminds us of Anne Elliot’s predicament with her little nephew. She suggests that sweet, retiring Anne Elliot resembles the heroine in Millennium Hall (1762), and another character in the book, Lady Lambton, is a possible precursor to Lady Russell: “a person of admirable understanding, polite, generous, and good-natured, who had no fault but a considerable share of pride.”

One of Charlotte Turner Smith's sentimental heroines I'm no expert about this, but perhaps borrowing a cup of inspiration from another author was a widespread practice.

One of Charlotte Turner Smith's sentimental heroines I'm no expert about this, but perhaps borrowing a cup of inspiration from another author was a widespread practice.In the podcast series Hidden Histories, three female academics point out that the poet William Wordsworth acknowledged his debt to the poet and novelist Charlotte Smith. Sir Walter Scott, credited with being a pioneer of the historical novel, was "quite upfront in some ways" in his borrowings-- "he lifts themes and images" from previous writers.

There are many, shall we say, glancing similarities to Austen to be found in other novels. Are we looking at similarity or inspiration? Jocelyn Harris, in Jane Austen’s Art of Memory, suggests that the haughty Miss Bingley is drawn from Miss Cantillon, a minor character in Sir Charles Grandison (1753), who is described as “pretty: but visibly proud, affected, and conceited” and who sometimes gave “affected smiles.” Likewise, she thinks Mr. Bingley owes something to another minor character, Mr. Singleton, a man “in possession of a good estate.”

Sir Charles Grandison is an early novel, and one of Austen's favourites, but I'm sure that many contemporary novels featured snobby young ladies, because they serve as useful foils for the heroine. Modern romances have them too! They are pretty much a stock character. And, as we have seen, announcing the income and social standing of a young man when he walks on to the pages of a novel was standard practice for the time.

Look at Ethelinde, or the Recluse of the Lake (1789) by Charlotte Smith. The overall plot of this novel bears no resemblance to Austen. But there are some similar characters and some similarities of incident: a baronet’s wife is described as indolent and vacant-minded and indifferent to her children, like Lady Bertram. Ethelinde is accidentally flung out of a boat during a pleasure excursion, just as Jane Fairfax almost comes to grief in Weymouth. Ethelinde turns down a marriage proposal in a carriage, like Emma turns down Mr. Elton. A cold-hearted wife urges her rich husband that he doesn’t need to give any money or assistance to his young relatives because he has his own family to support, like Fanny Dashwood. A father's "fortune was so conditioned as to leave it little in his power to provide for his daughters in a manner suitable to their rank," like Mr. Bennet. His wife frightens away her daughter’s potential suitors, like Mrs. Bennet. “It had been the study of her Ladyship’s life to get them well married; but in this important object she had hitherto failed, probably from the ill judged avidity with which she pursued it.”

Likewise, Constance (1785), Clara and Emmeline, or the Maternal Benediction (1788), Belinda (1801) and Coelebs in Search of a Wife (1809)--and no doubt other novels--feature heroines who refuse to marry well-born, wealthy suitors because of their vices, just as Fanny rejects Henry Crawford. We wouldn't expect Austen to be the only author who creates a heroine who puts love and self-respect ahead of money.

Did Austen pick up on any of the examples I've mentioned? Or, were all these authors ringing the changes on the basic marriage plot engaged with the same social milieu, and the resemblances arise from the fact that everyone is working with the same raw materials?

Sir Charles Grandison rescues Harriet Byron Whether or not Austen drew from this novel or that novel (and in the end it is all speculation), I feel I've gained a lot of insights by reading them-- in terms of how Austen's characters compare to other books, how she approached teaching her moral lessons, and how she eschewed melodrama and tragedy in favour of the subtle ironic comedy at which she knew she excelled. And now that these old novels are more widely available in digital versions, they provide a window into a

fascinating period

in history.

Sir Charles Grandison rescues Harriet Byron Whether or not Austen drew from this novel or that novel (and in the end it is all speculation), I feel I've gained a lot of insights by reading them-- in terms of how Austen's characters compare to other books, how she approached teaching her moral lessons, and how she eschewed melodrama and tragedy in favour of the subtle ironic comedy at which she knew she excelled. And now that these old novels are more widely available in digital versions, they provide a window into a

fascinating period

in history.The more old novels I read, the more interested I become in novelistic techniques and tropes. For example, I was surprised by the very complicated exposition techniques of this otherwise lightweight romance novel, and I think the author deserves some credit for it.

Those who have looked for traces of the influence of other writers in Austen's novels have tended to look at the best-known writers of the era--Maria Edgeworth, Frances Burney, Charlotte Smith, as well as the best known essayists of the past--Adam Smith, Samuel Johnson. But I've been finding connections with now-obscure writers, with the ones who wrote novels for the masses. I previously quoted Devoney Looser's remark in her Great Courses series on Austen that Jane Austen’s juvenilia shows that the young Austen was acquainted, not only with good books, but “with the opposite of great literature."

With that in mind, I'll look at the strange case of a novel with many coincidental similarities to Northanger Abbey in my next post. For an outline of Sir Charles Grandison and discussions of its resemblance or otherwise to Austen's novels, try this enjoyable blog series. I've written in earlier posts about 18th century stock characters who appear in Austen novels: the female pedant, the saucy sidekick, and the vulgar underbred lady and the fop. Many of the novels which contain examples of these characters are forgotten today, while Austen's creations are immortal.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Click here for the first in the series.

Published on August 31, 2021 00:00

August 26, 2021

CMP#66 Elizabeth Helme's five reasons

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series.

CMP#66: A Tribute to Elizabeth Helme

My article about the connection between Jane Austen's unfinished fragment Sanditon and Elizbeth Helme's novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest appears in the current issue of Jane Austen's Regency World magazine. Here is more about Elizabeth Helme.

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. I’ve also been blogging about now-obscure female authors of the long 18th century. For more, click "Authoresses" on the menu at right. Click here for the first in the series.

CMP#66: A Tribute to Elizabeth Helme

My article about the connection between Jane Austen's unfinished fragment Sanditon and Elizbeth Helme's novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest appears in the current issue of Jane Austen's Regency World magazine. Here is more about Elizabeth Helme.

Elizabeth Helme's writing career spanned almost thirty years. She wrote gothic novels, historical novels, and sentimental novels. Her sentimental novels are: Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor (1787), Clara and Emmeline, or the Maternal Benediction (1788), The Farmer of Inglewood Forest (1796), Albert, or The Wilds of Strathnavern (1799), and Modern Times (1814). These books have everything: virtuous heroines, dauntless heroes, suffering orphans, dastardly villains, rich uncles, dissipated aristocrats, untrustworthy foreigners, loyal servants, scheming servants, duels, runaway carriages, surprise inheritances, fainting, blushing, frenzy fits, life-threatening fevers, abductions, seductions, amazing coincidences, and.... some things that also show up in Jane Austen novels, too. While some scholars have touched on Helme's work in relation to abolition, black characters in 18th-century fiction, and other social issues, it appears she has not been discussed in relation to her possible influence on Jane Austen. I am convinced that Austen read at least three of her novels: She read Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor, because she parodies it in her juvenile fiction Love and Freindship.I believe Austen borrowed two plot devices from The Farmer of Inglewood Forest for Sanditon, andI contend that the character of Admiral Croft in Persuasion owes much to a character in another Helme novel.

Elizabeth Helme's writing career spanned almost thirty years. She wrote gothic novels, historical novels, and sentimental novels. Her sentimental novels are: Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor (1787), Clara and Emmeline, or the Maternal Benediction (1788), The Farmer of Inglewood Forest (1796), Albert, or The Wilds of Strathnavern (1799), and Modern Times (1814). These books have everything: virtuous heroines, dauntless heroes, suffering orphans, dastardly villains, rich uncles, dissipated aristocrats, untrustworthy foreigners, loyal servants, scheming servants, duels, runaway carriages, surprise inheritances, fainting, blushing, frenzy fits, life-threatening fevers, abductions, seductions, amazing coincidences, and.... some things that also show up in Jane Austen novels, too. While some scholars have touched on Helme's work in relation to abolition, black characters in 18th-century fiction, and other social issues, it appears she has not been discussed in relation to her possible influence on Jane Austen. I am convinced that Austen read at least three of her novels: She read Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor, because she parodies it in her juvenile fiction Love and Freindship.I believe Austen borrowed two plot devices from The Farmer of Inglewood Forest for Sanditon, andI contend that the character of Admiral Croft in Persuasion owes much to a character in another Helme novel.I'll follow up on that soon. The difficulties facing women writers

Many scholars interpret Jane Austen's "silent years" in Bath and Southampton as resulting from her social and domestic obligations and the lack of a congenial atmosphere in which to write. In addition, her novel Susan had been accepted by a publisher, but was never published, and Thomas Cadell turned down her novel First Impressions sight unseen. Years later, these books would appear as Northanger Abbey and Pride & Prejudice, but Austen must have been disappointed by these setbacks in her writing career.

All this is well known to my fellow Austenites, and I hope I don't offend them when I suggest that Elizabeth Helme--and many others like her--could not wait for a congenial atmosphere to write. They had to feed their families and many knew dire poverty. Charlotte Smith actually spent some time in debtors' prison because of her husband's debts, as did playwright Maria Barrell.

Helme had five children, worked as a teacher, produced ten novels and as many non-fiction works, as well as doing translation work. But little is known about her life. We have a rare glimpse of Helme in her preface to Clara and Emmeline, in which Helme referred to a speech that actress Sarah Siddons made when she left Bath for London. Siddons told the audience that her children were “three reasons... that bear me from your side." Helme wrote, “I have five as powerful reasons to induce me to write," adding that in addition she had "a natural inclination for the employ."

Mrs. Siddons acting in "Isabella" with her son, detail, National Portrait Gallery

Mrs. Siddons acting in "Isabella" with her son, detail, National Portrait Gallery

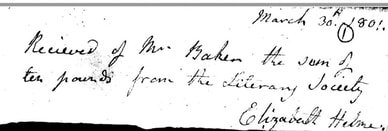

from the archive of the Royal Literary Fund So, I feel utmost respect for the tenacity of Elizabeth Helme and others like her. I can easily imagine that there were many genteel women, many impoverished women, even desperate women, who turned to novel-writing during this period. Of that group, some plucked up their courage and took their manuscripts to a publisher. Still fewer found a publisher, especially someone willing to buy the manuscript (as opposed to the author paying for the book to be published), and still fewer sold enough copies to make it worthwhile to keep writing. Scholars Michelle Levy and Reese Irwin note that sixty-six percent of the women published by Cadell & Davies published only one novel, and only a handful, like Hannah More, authored multiple volumes.

from the archive of the Royal Literary Fund So, I feel utmost respect for the tenacity of Elizabeth Helme and others like her. I can easily imagine that there were many genteel women, many impoverished women, even desperate women, who turned to novel-writing during this period. Of that group, some plucked up their courage and took their manuscripts to a publisher. Still fewer found a publisher, especially someone willing to buy the manuscript (as opposed to the author paying for the book to be published), and still fewer sold enough copies to make it worthwhile to keep writing. Scholars Michelle Levy and Reese Irwin note that sixty-six percent of the women published by Cadell & Davies published only one novel, and only a handful, like Hannah More, authored multiple volumes. Helme was one of those who became a prolific author. She wrote for the Minerva Press, which was not a prestigious publishing house, but one which "catered to the popular taste" for the sensational and the gothic, according to A Literary History of England. Despite her success, she was forced to turn to the Royal Literary Fund for financial assistance in 1801 and again two years later. The Fund was a private charity set up to provide authors with temporary emergency assistance. Beneficiaries of the Fund include Thomas Coleridge and Robbie Burns' widow.

One of Helme's letters to the Fund survives, dated October, 1803.

“Gentlemen: Sinking under mental and bodily evils, I have no recourse but to throw myself on your humanity... for seventeen years I have written for the public, and by that means supported myself respectably, and materially assisted a large family, but a very close application for the last three years, rendered necessary by the failure of all other [financial] means, have entirely destroyed my health… [and] reduced me to the painful necessity of making this application..."

Helme received a grant of ten pounds from the Fund in 1801 and again in 1803 at a time when the average grant was for eight pounds, equal to the annual wages of a poor labourer. Receiving ten pounds for a letter was the best return on the investment of her writing time that Helme ever knew. We can be pretty certain Helme's payments from her publisher did not reflect the hours of effort it took to write a novel. And if she had held out for more money--well, there were dozens of other aspiring novelists and translators to take her place. As scholar Clare Brant remarks in a review of a book about female authors of this era, "profits for authors were generally pitiful." But the work could be done at home, and writing was one of the few things genteel women could do.

As scholar Kate Scarth points out, Helme's "works did well critically and commercially" even though she has now sunk into obscurity. Scarth's podcast about Helme reviews what little is known about her life.

The prodigal daughter returns in "The Farmer of Inglewood Forest" The Farmer of Inglewood Forest

The prodigal daughter returns in "The Farmer of Inglewood Forest" The Farmer of Inglewood ForestAs I've previously pointed out, if you are interested in abolition and slavery in Austen's time, and you've been told novel-writers of the period shied away from the topic, you should know about The Farmer of Inglewood Forest.

Helme is unequivocally anti-slavery. The Farmer includes depictions of enslavement, branding, flogging, the rape and murder of a female slave, and uprisings in which planters are killed. Two emancipated Africans, Felix and Julia, have agency in the novel. They openly condemn their former masters and they criticize English society. This novel was reprinted well into the 19th century.

Some modern readers might be put off by the emphasis on female chastity and the religiosity of the story. But we must bear in mind that Helme was writing to a market, and this kind of melodrama was what the market wanted.

William Godwin (1756-1836) There's one additional point I wanted to make about the Farmer of Inglewood Forest, and it has to do with the name of the titular farmer: Godwin.

William Godwin (1756-1836) There's one additional point I wanted to make about the Farmer of Inglewood Forest, and it has to do with the name of the titular farmer: Godwin. The main theme of The Farmer is virtue versus vice. A brother and sister raised in the country by virtuous parents are seduced by the glittering lures of London. The young daughter in particular is taken in by the blandishments of a "new age" thinker. She abandons Christian morality and is seduced (groomed, I think we would say) by her lover. Elizabeth Helme, the author, arranges dire consequences for her.

I think Helme must have chosen the surname "Godwin" for a reason. William Godwin was, at the time, a very well-known name. He was an anarchist philosopher, and he was best known for his belief that marriage and monogamy were artificial social constructs which should be done away with. He was also the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft. He married her when she became pregnant with his child. They apologized to their radical friends for backsliding on their principles, but the fact was that illegitimacy was a terrible social burden to place on a child. At any rate, naming the farm family "Godwin" is surely intended to bring William Godwin to mind.

I have argued that there is no compelling reason to believe that Mansfield Park is named after Lord Mansfield, the chief justice whose legal ruling led to the end of slavery within the British Isles. As I've said, why name a mansion owned by the slave-owning Bertrams after Lord Mansfield? The Bertrams don't lose the house; they aren't punished as a result of owning slaves. So I don't see what the message is. ( See here for more speculation about the choice of "Mansfield").

But here, I must admit, Helme has named her virtuous Christian family with a sly allusion to a philosopher whose ideas were widely condemned at the time. It's a counter-example to my argument that Austen would not give the name of an abolitionist to the home of a slave-owning family.

I discuss Helme's novel Modern Times here. More about Helme to come. Brant, Clare, review of Women Writing About Money, in The Review of English Studies, Volume XLVIII, Issue 190, May 1997, Pages 259–261

Baugh, A. (Ed.). (1959). A Literary History of England Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Routledge. Two quotes:

"In the sub-literary depths of romanticism there were hundreds of stories in imitation of Mrs. Radcliffe, Lewis, and the horror-mongers of the Continent. Here iniquity rioted in ruined castles and dim oratories and crypts and dungeons, where monstrous villains oppressed the innocent, and ghosts walked, and demons lured their victims to destruction. But into these noisome fastnesses we need not descend."

"The happiest and most productive years in the life of Jane Austen were passed in two small towns of Hampshire... In the uncongenial atmosphere of Bath she accomplished little; nor were the three years in Southampton, where, after her father's death, she lived with. her mother, more fruitful. Not until she breathed again the congenial air of the provincial town of Chawton did the creative instinct reassert itself."

Cross, Nigel. Authors and the Literary Fund. Thesis. 1980. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint...

Very interesting reading!

Levy, Michelle and Irwin, Reese, "The Female Authors of Cadell and Davies," in Women's Literary Networks and Romanticism : A Tribe of Authoresses. Liverpool University Press, 2017.

Published on August 26, 2021 00:00

August 17, 2021

Guest Post at The Book Rat

Misty at

The Book Rat

hosts an annual online event called "Austen in August" and invites participation from Janeites around the world to celebrate Jane Austen.

Misty at

The Book Rat

hosts an annual online event called "Austen in August" and invites participation from Janeites around the world to celebrate Jane Austen.My guest blog is based on a bit of advice that Jane Austen sent to her niece Anna Austen LeFroy concerning novel-writing.

Austen didn't care for the phrase "vortex of dissipation." She thought it was what we would call today a cliché. And a lot of authors used the term, as well as a lot of essayists! I supply just a sample in my blog post. Many 18th century novels showed dissipated characters, but for the purposes of morality, it was important that they either be reformed or be punished by the end of the story. Thus they provided both titillation and a moral lesson.

I think my favourite dissipated character in 18th century literature is Lady Delacour from Belinda by Maria Edgeworth, though she doesn't use the word "vortex."

I've got more about the Vortex of Dissipation at this earlier post.

Published on August 17, 2021 13:00

CMP#65 Austen and Social Class

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here

for the first in the series.

CMP#65 Austen Plus Money Plus Social Class

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past. Click here

for the first in the series.

CMP#65 Austen Plus Money Plus Social Class

Distinctions of rank: Emma disapproves when Robert Martin woos Harriet Smith Just as many critics have commented on the focus on money in Austen, some critics have read deep meaning into the fact that most of Jane Austen’s characters move in a higher social sphere than she did in real life. Austens' parents were pseudo-gentry, or of the middling class. They did not own property. Their sons (except Edward and their disabled brother George) had to work for a living. Jane and her sister Cassandra had almost no income of their own, not enough to make them financially independent.

Distinctions of rank: Emma disapproves when Robert Martin woos Harriet Smith Just as many critics have commented on the focus on money in Austen, some critics have read deep meaning into the fact that most of Jane Austen’s characters move in a higher social sphere than she did in real life. Austens' parents were pseudo-gentry, or of the middling class. They did not own property. Their sons (except Edward and their disabled brother George) had to work for a living. Jane and her sister Cassandra had almost no income of their own, not enough to make them financially independent. In a New Yorker article , "How to Misread Jane Austen," Louis Menand asks if there is any significance in the fact that her main characters are wealthier than she was. “Does this mean that she was pressing her nose against the glass, imagining a life she was largely excluded from?” Or, Menand asks: “does it mean that she could see with the clarity and unsentimentality of the outsider the fatuity of those people and the injustices and inequalities their comforts were built on?” That is, does Austen write about the magnificent grounds at Pemberley out of fascination or envy?

Well, before speculating on that point, I think it would be useful to ask: was Austen different from her fellow authors in this respect? Was she, the daughter of a country clergyman, unusual in her choice to write about people who were richer and of higher social standing than herself?

Of course she wasn't. While some aristocratic ladies wrote novels, most female novelists were educated women from the middling classes. Lady Sydney Morgan sounds like she's an aristocrat but she was the daughter of an actor and she worked as a governess before her marriage. A uthors such as Elizabeth Helme or Eliza Kirkham Mathews came from the lower middle classes, and they wrote about gambling dens and masked balls and travelling by post-chaise and sending messages by footman and long-lost extremely rich uncles -- people and situations they could have known little about from first-hand. Mary Jane MacKenzie lived in genteel poverty but her characters lived in beautiful mansions and travelled to France and Italy. Jane Austen maintained her genteel status, that is, she never had to take a job to survive. Selina Davenport worked as a teacher and ran a little shop to support her two daughters. Her first novel was The Sons of the Viscount and the Daughters of the Earl, a tale of fashionable life.

Novel-readers liked to read about people with carriages and mansions. They liked to read about virtuous young men and women who were elevated to wealth and comfort by various fortuitous if implausible plot twists. They liked to tut-tut at dissolute noblemen gambling their fortunes away and sinking into a vortex of dissipation .

Many readers, and writers, of novels did not move in the high social spheres described in them. An entire genre arose in the 1820s focused on the lives of the privileged classes. The authors of these silver-fork novels , as the critic William Hazlitt pointed out, were middle-class people.

Lifestyles of the rich and titled When 18th-century authors tell us how rich somebody is, they usually couple it with an explanation of their social rank. Anthony Trollope (1812 - 1885) was of a later generation, but he too opened his novels by sketching out the social class, family background, and financial expectations of his main characters. Framley Parsonage (1860) begins with the father of a clergyman, "a gentleman possessed of no private means, but enjoying a lucrative [medical] practice." His son is lucky enough to befriend young Lord Lufton at school, and Lady Lufton, his friend's mother, gives him a living worth 900 pounds a year. The newly-minted clergyman marries an agreeable girl who "had been left with a provision of some few thousand pounds." The clergyman's ambitious entrée into a higher social class peopled by bishops, dukes and politicians leads to him into financial trouble.

Lifestyles of the rich and titled When 18th-century authors tell us how rich somebody is, they usually couple it with an explanation of their social rank. Anthony Trollope (1812 - 1885) was of a later generation, but he too opened his novels by sketching out the social class, family background, and financial expectations of his main characters. Framley Parsonage (1860) begins with the father of a clergyman, "a gentleman possessed of no private means, but enjoying a lucrative [medical] practice." His son is lucky enough to befriend young Lord Lufton at school, and Lady Lufton, his friend's mother, gives him a living worth 900 pounds a year. The newly-minted clergyman marries an agreeable girl who "had been left with a provision of some few thousand pounds." The clergyman's ambitious entrée into a higher social class peopled by bishops, dukes and politicians leads to him into financial trouble. Just like the earlier novels I referenced, Framley Parsonage has page after page of financial detail. We hear all the details of a last will and testament and we see the dire consequences of marrying on a limited income or getting mired in debt. Class barriers are a big issue in this novel as well. Lady Lufton doesn't want her son to marry Lucy, the clergyman's sister -- her social standing is too low and she'll bring no fortune or land to the marriage.

The suspense of many novels turned on whether the handsome young lord would be able to marry the girl of his choice. The number of eligible rich noblemen in the pages of novels far exceeded the reality, then as now. As Anthony Trollope says: "young, good-looking bachelor lords do not grow on hedges like blackberries." The lifestyles of the rich and titled were a widespread fascination, and sold a lot of novels.

Mrs. Reynolds calls Darcy the best master, and Elizabeth is impressed To return to Menand's question, did Jane Austen admire the privileged class or quietly despise them? How about both, depending upon the exigencies of the plot? Austen portrays Sir Walter Elliot as a conceited fool who neglects his tenants. Lady Catherine De Bourgh is laughed at for being overzealous in the attention she pays to her tenants: "she was a most active magistrate in her own parish, the minutest concerns of which were carried to her by Mr. Collins; and whenever any of the cottagers were disposed to be quarrelsome, discontented, or too poor, she sallied forth into the village to settle their differences, silence their complaints, and scold them into harmony and plenty."

Mrs. Reynolds calls Darcy the best master, and Elizabeth is impressed To return to Menand's question, did Jane Austen admire the privileged class or quietly despise them? How about both, depending upon the exigencies of the plot? Austen portrays Sir Walter Elliot as a conceited fool who neglects his tenants. Lady Catherine De Bourgh is laughed at for being overzealous in the attention she pays to her tenants: "she was a most active magistrate in her own parish, the minutest concerns of which were carried to her by Mr. Collins; and whenever any of the cottagers were disposed to be quarrelsome, discontented, or too poor, she sallied forth into the village to settle their differences, silence their complaints, and scold them into harmony and plenty." Are we supposed to be similarly critical of Darcy or Mr. Knightley for their privileged lives? They are presented as men who responsibly discharge their duties as landlords and local administrators. They uphold the roles in life to which they were born, unlike Sir Walter. Lady Russell of Persuasion is an intelligent, dignified, well-meaning woman, not a monster. I don't see these various portraits as an indictment of the entire social order.

It's true that aristocrats like Lady Catherine De Bourgh do not escape Austen's satiric pen. She dismisses the Dowager Viscountess Dalrymple and her daughter in Persuasion as being undeserving of any special deference because, without their titles, they are quite ordinary people. But where Austen used a barb, others used a bludgeon. For example, Charlotte Smith's Ethelinde features several scathing portrayals of rich, decadent aristocrats who gamble, carouse and go after pretty girls, including the heroine. In Albert, or, the Wilds of Strathnarven, a young nobleman lusts after the pretty daughter of one of his tenants. He offers her a job as a housemaid on his estate, then rapes her. His fiancée refuses to marry him once she hears about it. She marries the son of a merchant and she is cast out of her family as a result.

Furthermore, while Austen laughs at snobs, she also laughs at social climbers. As John Mullan says: "The snobs and arrivistes of her England are remorselessly skewered." Sir Walter Elliot is a snob, Mrs. Elton is an arriviste. Mr. Collins is a toady, Mrs. Clay is a gold-digger. But again, this is true of other authors of the era as well. Ethelinde contains a withering portrait of a Bristol family of merchants. The Ludgates are vulgar social climbers with money but no elegance. The villain in The Gipsey Countess is a step-mother who flaunts her newly-acquired wealth in tasteless displays.

So, if we are going to expound on Austen's daring social criticism, I think it's important for the sake of context to point out that many authors wrote critical portraits of their world. In fact, I have yet to encounter a writer of the era who did not. If Austen is a social critic, I'd ask, compared to whom? More about Austen and social class in this post .

Anne Elliot is elegant, principled and sweet-natured. She fell in love with Lieutenant Wentworth, who was beneath her socially. But Anne doesn't want Mrs. Clay, a widow from a lower social class, to marry her father. I revisit the story of Persuasion from Mrs. Clay's point of view in "The Art of Pleasing," a short story in the anthology Rational Creatures, from Quill Ink.

Published on August 17, 2021 00:00

August 9, 2021

CMP#64 The Meaning of Money

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about Jane Austen and the beliefs of her times. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#64 The Meaning of Money, or Plot versus Protest

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about Jane Austen and the beliefs of her times. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#64 The Meaning of Money, or Plot versus Protest

Mr. Bennet, not the most involved father In my last

two posts

, I shared examples demonstrating that many authors of Austen's time focused on money in their novels; the topic was by no means unique to Austen.

Mr. Bennet, not the most involved father In my last

two posts

, I shared examples demonstrating that many authors of Austen's time focused on money in their novels; the topic was by no means unique to Austen. Many critics do more than point out how important money matters are in Austen's novels; they draw conclusions about Austen's attitudes toward her society, based on the mentions of money in her novels. Professor Robert D. Hume, for example, is certain that Austen intended a critique of her patriarchal society. He is more indignant on behalf of the Bennet girls than Austen is herself. In "Money in Jane Austen" he spells out the very unfunny failures of Mr. Bennet, who hasn't saved money for his daughters, and concludes that we ought to despise him. Although Hume acknowledges that Austen does not condemn Mr. Bennet, he nevertheless thinks "Pride and Prejudice is a glum but telling satiric protest against the socio-economic position of early nineteenth-century women, elegantly camouflaged in a fantasy romance." Before defining Austen as a writer of protest novels, shouldn't we ask, are her situations or themes notably different for her era? Was Austen singular or remarkable or in her treatment of parents, daughters and money? Is it unusual for an 18th century novel to feature as its heroine a girl of good birth but modest means? Was it unusual for a heroine to have a despotic or flawed father?