Lona Manning's Blog, page 16

April 5, 2022

CMP#96 Edgar, the Cinderella hero

"I think it is fair to say that while no-one is ever going to mistake... Meeke’s writing for great literature, she certainly does keep you turning the pages."

"I think it is fair to say that while no-one is ever going to mistake... Meeke’s writing for great literature, she certainly does keep you turning the pages." – Blogger Liz at A Course of Steady Reading CMP#96 The Cinderella Hero, or, The Blue-Blooded Hunks of Minerva

Dashing young man with "Brutus" hairstyle. Here’s the second post in my new occasional series of books that never got a book review when they were published. For the first,

click here.

Dashing young man with "Brutus" hairstyle. Here’s the second post in my new occasional series of books that never got a book review when they were published. For the first,

click here.

This time, I’m reviewing Stratagems Defeated (1811), a four-volume effort by Mrs. Meeke, a prolific authoress who wrote for Minerva Press , a publishing house that specialized in knock-off gothic novels and other sensational fare. It seems her works were a guilty pleasure for the British statesman Thomas Babington Macaulay; he read them avidly, but surreptitiously noted their titles in his journal in Greek.

Mrs. Meeke may have been a stepsister to the successful authors Frances Burney and Sarah Harriet Burney, but she didn’t use the Burney name on her title pages. Instead she published under the pseudonym “Gabrielli,” a name which connotes Italian exoticism. Stratagems Defeated features a wily Sicilian priest and not one, but two people held prisoner by someone trying to force them into marriage, but it is not a gothic novel. Neither is it a tender romance-- the female love interest doesn’t even show up until the final volume, and there are no impediments to keep hero and heroine apart once they meet. In fact, by the time they meet, the hero is the most ridiculously eligible bachelor in the United Kingdom.

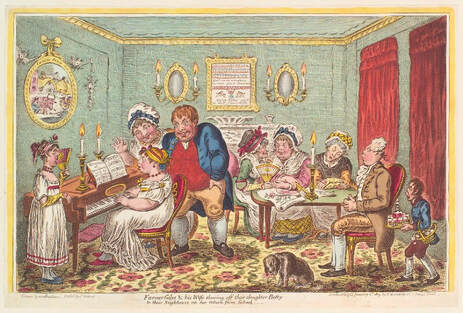

Living large at Vauxhall Gardens Edgar Mortimer is an intelligent and plucky orphan brought up in reduced circumstances. He's handsome, benevolent and level-headed, and before we're done, he inherits three large fortunes and two noble titles. I

earlier wrote

about the importance of death for setting up plots in 18th century novels, especially when the protagonist is an orphan or a foundling; in this case, the authorial slaughter is quite comprehensive on both Edgar's maternal and paternal lines. In the first volume, Meeke sets up a complicated family tree on Edgar’s mother’s side, with step-fathers and step-mothers and half-siblings and a backstory involving impulsive love matches, fraud, bankruptcy, suicide, and parental estrangement. When the dust settles, Edgar is left with his maternal grandmother—whoops, no, she dies too—he's left with a kindly clergyman and a small inheritance, enough to send him to a second-rate boarding school. At eighteen, he starts toiling at a counting-house in London.

Living large at Vauxhall Gardens Edgar Mortimer is an intelligent and plucky orphan brought up in reduced circumstances. He's handsome, benevolent and level-headed, and before we're done, he inherits three large fortunes and two noble titles. I

earlier wrote

about the importance of death for setting up plots in 18th century novels, especially when the protagonist is an orphan or a foundling; in this case, the authorial slaughter is quite comprehensive on both Edgar's maternal and paternal lines. In the first volume, Meeke sets up a complicated family tree on Edgar’s mother’s side, with step-fathers and step-mothers and half-siblings and a backstory involving impulsive love matches, fraud, bankruptcy, suicide, and parental estrangement. When the dust settles, Edgar is left with his maternal grandmother—whoops, no, she dies too—he's left with a kindly clergyman and a small inheritance, enough to send him to a second-rate boarding school. At eighteen, he starts toiling at a counting-house in London.In the first volume we spend all our time with the merchant classes, which I thought was rather unusual since novels of this period are more preoccupied with the wealthy and titled . Meeke gives us a colourful cast of London characters; this first section reminds me more of Dickens than Austen. Are any women engaged in business in Austen, outside of Mrs. Goddard in Emma? In Stratagems Defeated, we meet an avaricious milliner, a gossipy woman who runs an oyster-bar, and several women who competently run inns and “eating-rooms.” As for the men, there are roguish young clerks who live beyond their means, there’s a miserly tobacconist and there are wealthy merchants. There is no condemnation of colonial fortunes ; on the contrary, Mr. Hamilton, a West-India merchant, is one of the good guys. His chief clerk overworks his underlings like a “negro-driver” when the boss is away but apart from that, there is no mention of the slave trade.

Priggish Hirsch with wacky coworkers These colourful characters tend to overshadow the staid hero. Edgar Mortimer is like the level-headed central character surrounded by eccentrics in a situation comedy, like Judd Hirsch in Taxi. Compared to the other spendthrift, wastrel, clerks in the counting house, he is forbearing and self-controlled, a “picture of perfection.”

Priggish Hirsch with wacky coworkers These colourful characters tend to overshadow the staid hero. Edgar Mortimer is like the level-headed central character surrounded by eccentrics in a situation comedy, like Judd Hirsch in Taxi. Compared to the other spendthrift, wastrel, clerks in the counting house, he is forbearing and self-controlled, a “picture of perfection.”Edgar learns that he is the heir to the Earl of Huntingdon because he is the only surviving male relative on his father's side. (This revelation doesn't come at the end of the novel, but near the end of volume one.) Edgar vows to remain on friendly terms with the kindly clergyman who raised him, the schoolteacher who educated him, and his best friend from the counting-house, but soon realizes that his patrician grandfather intends to manipulate him into dropping his lower-class connections. I assumed that we wouldn’t hear anything more about most of the characters from volume one but that wasn’t the case. Their sub-plots and antics formed the most entertaining part of the novel, even as Meeke adds more dramatic complications involving a new cast of wealthy and nobly-born characters.

Stratagems Defeated should make it abundantly clear that Jane Austen was hardly unique in mentioning the income and financial prospects of her characters. Meeke dwells at length on wills and inheritances, lawsuits and marriage settlements. Here, for example, are the details about the Owensons, who are very minor characters: Mr. Owenson “had a very handsome income, and when he died, he left [his daughter] eighteen thousand pounds, independent of her mother, to whom he left Dunraken Castle, and a thousand a-year, which is also secured to her daughter at her demise: Mrs. Owenson is besides heir-at-law to Mr. Tudor, of Carador House, who cannot, I believe, deprive her of the principal part of his Welch estates, though I have heard it whispered that he might cut off the entail."

Exotic Welsh atmosphere

Spoilers follow

Exotic Welsh atmosphere

Spoilers follow

The next question to consider is: did Austen or Meeke intend a social message? Some modern scholars contend that Austen was protesting against her patriarchal society and its institutions like primogeniture. If that is so, then Austen has nothing on Meeke. Sense & Sensibility features three sisters who lose out when their wealthy relative dies. In Stratagems Defeated, we have an absolute smorgasbord of villainy:a girl's brother-in-law claims she’s insane and can’t inherit her father’s estate,a corrupt guardian cheats numerous wards and widows out of their inheritances,somebody forges a will to deprive the heirs of their property and money--not once but twice,a man is bribed to marry a girl he doesn’t love so the hero won’t marry her. Some female characters with power and money abuse their power. The milliner cheats her daughters, a sister schemes to send her sister to a convent, the woman running the dormitory for the clerks feeds them scanty, inedible meals.

Or, if the secret message of Northanger Abbey is that marriage and giving birth is often fatal for women, Austen again has nothing on Meeke. None of the younger main characters have a living mother and father; most have neither.

As for the literary features of this book, I was struck by Meeke’s tendency to spin out lengthy sentences with a never-failing stream of commas and semi-colons. We can speculate that her prolix prose style is a reflection of her financial need to churn out three and four volume novels to support herself after her first marriage fell apart. Therefore we get plenty of details. We learn how people are dressed, whether they eat dinner early or fashionably late, how many servants attend them, and all their travel details. As it happens, most of these every-day details were of interest to me, because they're the kind of details that Jane Austen leaves out. The following excerpt gives an idea of the run-on sentences and the level of prosaic detail: the hero and his friend are travelling to Bath by post-chaise, and Edgar's loyal valet Harris is riding on ahead to an inn owned by his family, to have everything in readiness: At Reading [Edgar and John] alighted while the horses were changing, and as it was past two, they ate some cold fowl and ham, and drank a few glasses of sherry, not meaning to dine before they reached Hungerford, which they told Harris, who begged leave to ride forward from thence; the footman could take his place upon the box, and as he was known at Speen-Hill, he should not be required to wait the arrival of the carriage; but might, by this means, have dinner ready against his Lordship’s arrival. Edgar made no objection to his proposal; and as the postillions were well paid, the day cool, and the roads good, they got on very fast. "Playing With Her Readers' Expectations"

Another feature of the novel that surprised me is that the author teases us about introducing a love interest for the hero. I’ve learned from reviews of Meeke’s earlier novels posted at the “Course of Steady Reading” blog that she specialized in putting surprise twists and red herrings in her plots, which often centered around a male Cinderella figure. She “has fun playing with her readers’ expectations…”

In volume 2 of Stratagems Defeated, Edgar and his friend John witness a carriage accident during the afore-mentioned trip to Bath. Meeke uses the accident to:editorialize against reckless driving,create a sub-plot about the theft of some jewels by an acquaintance of Edgar's who coincidentally was in the wrecked carriage, andtease her readers about the non-appearance of the heroine: (Ahem. Speaking of run-on sentences...) By this time the friends had extricated two ladies and an elderly gentleman from the coach.

“'The heroine, of course," cries a female reader, well versed in such novel adventures. We agree that overturns, runaway horses, running streams, and thunder-storms, are often the means of introducing the hero to his fair intended, but we are not so indecorous as to place the future wife of a peer in a stage-coach, therefore, the ladies above-mentioned are by no means concerned in our story, since they were merely returning to Exeter, having been on a visit to a relation in London…

Les accidents de voiture As the story proceeds we meet several young ladies who might be the love interest for the hero, and it turns out they are not. Lady Elinor, the actual future wife for Edgar, doesn’t appear until Volume 4, and he accepts her as his wife not because he was captivated with her at first sight, but on the recommendation of his uncle. Edgar “was certainly not violently in love with her Ladyship, but he was so well convinced that she would make an excellent wife, he meant, as soon as their very short acquaintance had ripened into friendship, to offer himself to her acceptance….” And this, despite the fact that they meet under highly romantic circumstances. I mean, for a meet cute, you can't do better than rescue a girl from French privateer by dueling with the captain and overcoming him just as you both burst into the cabin where she's hiding, can you?

Les accidents de voiture As the story proceeds we meet several young ladies who might be the love interest for the hero, and it turns out they are not. Lady Elinor, the actual future wife for Edgar, doesn’t appear until Volume 4, and he accepts her as his wife not because he was captivated with her at first sight, but on the recommendation of his uncle. Edgar “was certainly not violently in love with her Ladyship, but he was so well convinced that she would make an excellent wife, he meant, as soon as their very short acquaintance had ripened into friendship, to offer himself to her acceptance….” And this, despite the fact that they meet under highly romantic circumstances. I mean, for a meet cute, you can't do better than rescue a girl from French privateer by dueling with the captain and overcoming him just as you both burst into the cabin where she's hiding, can you?Other features of interest: There is more mention of Bonaparte than you'll find in an Austen novel. The characters twice cite Lord Mansfield (the British jurist after whom Mansfield Park is supposedly named), but they don’t mention his ruling against slavery in the United Kingdom, they reference his thoughts on bankruptcy. The hero remarks that he prefers the novel Celia in Search of a Husband to the original best-seller Coelebs in Search of a Wife. Celia was written to cash in on the popularity of Coelebs, so we have one Minerva Press novel (Stratagems Defeated) recommending another Minerva Press novel (Celia). Talk about product placement.The novel's ending is definitely not one of your concise Austen-style summations. Meeke ties up a lot of plot points with her customary detail, and lets us know the fate of every character of note. I read most of Stratagems Defeated with enjoyment, although I began skimming by the fourth volume. I enjoyed it more for the ways it differed from Austen than for any similarities (there is a mention of a Baron D'Arcy). I think it would serve as a fun resource for writers of Regency fiction because of the every day details of life, down to how much to tip the ostler. About Mrs. Meeke

Scholar Simon Macdonald first discovered that the prolific author Mrs. Meeke was Elizabeth Meeke, a Burney step-sister with a colourful marital history. Some references still list “Mrs. Meeke” as “Mary Meeke,” the wife of a minister. Anthony Mandal says Mrs. Meeke was "The most prolific novelist of the romantic era... whose twenty-six original novels and four translations, published over a period of almost thirty years, eclipsed even Sir Walter Scott’s famous output."

The Feminist Companion to Literature in English says that Meeke wrote to a pattern: "She writes grippingly, especially in dramatic or low-life openings... before the nobility appear." In the preamble to her 1802 novel Midnight Weddings, Meeke wrote that novelists had already exhausted all possible plot ideas. She was not “enough within the vortex of fashion to exhibit the follies of its votaries to great advantage,” that is, she did not move in the highest circles of society and could write more convincingly about a tobacco shop than a stately mansion. She also advised aspiring writers to “consult the taste” of their publishers, “for should you fail of meeting with a purchaser [for your novel], that labour you hope will immortalize you is absolutely lost.”

More modern-day Meeke reviews at this blog, "Only a Novel."

Thomas, William. The Journals of Thomas Babington Macaulay Vol 1. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2021.

Anthony Mandal; "Mrs. Meeke and Minerva: The Mystery of the Marketplace." Eighteenth-Century Life 1 April 2018; 42 (2): 131–151

Published on April 05, 2022 00:00

April 1, 2022

“Fanny found herself obliged to yield”

Note: Last year, I shared a provocative article by noted Austen scholar Lila Proof, which referenced the pioneering work of Dr. Aprille Stulti. To my surprise and gratification, I was subsequently contacted by Dr. Stulti and asked if I would help publicize her exciting research discovery concerning Mansfield Park. Take it away, Dr. Stulti... “Fanny found herself obliged to yield:”

the hermeneutics of the cross and the chain in Mansfield Park

A special guest editorial by Aprille Stulti, Ph.D. “I cannot look out of my dressing-closet without seeing one farmyard, nor walk in the shrubbery without passing another,” Mary Crawford complains in Mansfield Park. Modern readers have often missed or misunderstood Austen's critical stance on the agricultural revolution and the growth of the British empire. On the surface, we see Mary, a quintessential city girl, surprised to find that she is not able to hire a horse and wagon to transport her harp to the parsonage. But a closer interrogation of the text reveals that Jane Austen was working both with and against Mary Crawford’s seeming ignorance of the realities of agricultural life.

“I cannot look out of my dressing-closet without seeing one farmyard, nor walk in the shrubbery without passing another,” Mary Crawford complains in Mansfield Park. Modern readers have often missed or misunderstood Austen's critical stance on the agricultural revolution and the growth of the British empire. On the surface, we see Mary, a quintessential city girl, surprised to find that she is not able to hire a horse and wagon to transport her harp to the parsonage. But a closer interrogation of the text reveals that Jane Austen was working both with and against Mary Crawford’s seeming ignorance of the realities of agricultural life.

This essay will contend that a close reading of language in Mansfield Park—especially of such seemingly innocuous words such as “survey” and “yield”—reveals Austen’s counter-reaction to agricultural development. Mary Crawford is not merely trying to hire a horse, she is protesting the encroachment of capitalist-based agriculture, which ironically supports the prosperity of her own gentry class. Mary is paradoxically presented as both victim and beneficiary--and finally perpetrator--of imperialist violence.

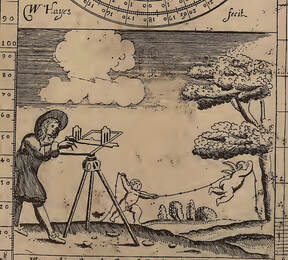

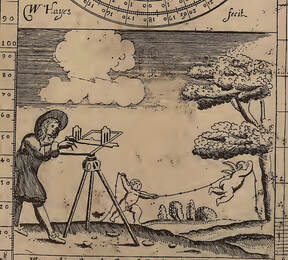

This essay will explore how key scenes in Mansfield Park, especially those concerning the amber cross and chain, might adumbrate Austen's resistance to her times... William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722 "A Full Survey of Her Face"

William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722 "A Full Survey of Her Face"

Fanny Price, the heroine/hostage of the novel, is associated with surveying immediately upon her arrival at Mansfield Park; we are told that the young Bertram sisters, Maria and Julia, “were soon able to take a full survey of her face and her frock in easy indifference.”

A “survey” of Fanny inevitably associates this vulnerable girl in the readers' mind with the imposition of invisible boundaries on open space. The language that describes Fanny's "yielding" is the language of land surveying, cultivation and conquest. It is not insignificant that farmers spoke of “breaking” the land with a plow. Fanny, too, will be cultivated, transformed into a genteel young lady. She is forced to yield to the will of others, just as farmland yields crops: Repeatedly we are told Fanny is "obliged to yield," or "she must yield."

From this introductory chapter, until we come to the Sotherton episode, the references to surveying and improvement are few. However, the more obliquely Austen refers to surveying, the more important it is to our understanding of the novel. Within that negative space created by Austen, the idea of the imposition of control is pointedly invoked by the name of Dr. Grant, the resident clergyman of Mansfield, and the host to Mary Crawford and her brother Henry. Dr. Grant's name is highly suggestive of grants of land, as from a sovereign to a loyal subject. The Grants, significantly, also busy themselves in extending and improving their property. They have “carried on the garden wall, and made the plantation to shut out the churchyard.” This last comment comes from Mrs. Norris, who is "excessively fond" of "planting and improving."

Surveying returns “as the particular object” when the young people go to Sotherton. “How would Mr. Crawford like, in what manner would he chuse, to take a survey of the grounds?" As the print from "The Compleat Surveyor" (above) indicates, surveying was presented as a benign activity carried out by little cherubs, but Austen deploys Henry's survey of the grounds ironically as a powerful metaphor of the tyranny of land ownership.

Of all of the characters, Henry Crawford is most associated with surveying.And before long, Henry's predatory gaze falls upon Fanny.  Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra The Cross, the Necklace, and the Chain

Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra The Cross, the Necklace, and the Chain

"He loves to be doing," his sister says proudly (and suggestively) of her brother's fondness for "improvements." The oppressive heteronormativity and patriarchy of Henry Crawford’s flirtatious games are intertextually allied to surveying and land use through the material objects of the cross and chain in Chapter 26 of Mansfield Park.

The cross and chain were taken at face value by previous generations of Austen scholars; the amber cross was a symbol of the faith practiced by Fanny Price and her creator, and is especially valued by Fanny as a gift from her beloved brother William. The chain is from Edmund, the man she secretly loves, and it enables her to wear the cross. Austen tells us that Edmund’s chain and cross together are “memorials of the two most beloved of [Fanny’s] heart, those dearest tokens so formed for each other by everything real and imaginary.”

But of course, Austen's intent here is ironic. This truth has been acknowledged in post-colonial Austen scholarship for over thirty years. No-one today supposes that Mansfield Park is a love story, that Fanny could possibly love Edmund, or be proud of her colonizing brother William the sailor.

It is agreed that Austen is subverting something with the cross and chain, but opinions still differ as to exactly what she is subverting. One scholar has argued that the chain represents slavery, and the cross represents the Church of England’s complicity in slavery through its ownership of the Codrington plantations. Others have seen a straightforward sexual inference. Henry Crawford’s ornate necklace “would by no means go through the ring of the cross… it was too large for the purpose.” Edmund’s (presumably smaller) “chain” does fit through. It goes without saying that any object that is longer than it is wide is an encoded sexual symbol, but I intend to extend and contest the existing interpretations. Surveying and Suffering

Surveying and Suffering

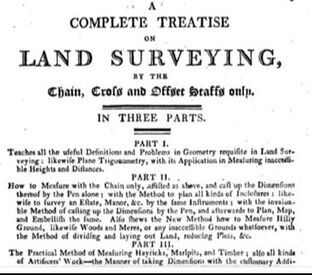

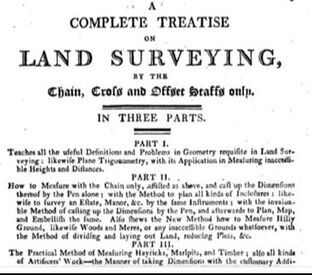

In fact, the chain and the cross together are the tools of the land surveyor, as Austen’s contemporaries would have instantly recognized. In encountering Mansfield Park, they would undertand the remarkable similarities with A Complete Treatise on Land Surveying, by the Chain, Cross and Offset Staffs Only (1798), parallels that critics have not previously noted.

The Treatise is described by the Dictionary of National Biography as a “a popular work which went through five editions by 1813,” which means it preceded, was better known, and was more widely-read than Mansfield Park (published in 1814.)

Space permits only a few examples of the intertextual relations between Mansfield Park and the Treatise. The Treatise states (emphasis added): “Suffer your chain leader to go no farther than the nearer side of the ditch... the ditch being the property of the next field.” Paradoxically, Austen camouflages the allusion by never using the word “ditch” in Mansfield Park; she substitutes the word “ha ha.” This interior joke must have afforded much grim and ironic amusement.

“Suffer” in this sense it means “to permit or allow.”* Edmund, significantly, invokes the term suffering in the scene at the chapel at Sotherton when he ostensibly defends public worship over private prayer: “Do you think the minds which are suffered, which are indulged in wanderings in a chapel, would be more collected in a closet?” Edmund wants anyone capable of independent thought to be "collected," preferably in a place where he can keep an eye on them. Even this chilling pronouncement does not shake Fanny’s misguided loyalty to Edmund.

We move from this unsettling scene to one even more distressing: Edmund argues with Mary Crawford as they walk in the wilderness. And what topic, out of all the topics in the world, are they arguing about? The extent of the wilderness! They have both visually surveyed the wilderness, an artificial simulacrum of unimproved land, and disagree about its extent. Mary says “with feminine lawlessness” that the unconquered area is vast, while Edmund “attacks” her and attempts to “dictate” to her, to force her to acknowledge that the remaining uncultivated land “could not have been more than a furlong in length.”

“Oh! I know nothing of your furlongs,” Mary protests, but before long, she herself becomes complicit when she places Henry's necklace, or rather, his chain, around Fanny's "lovely throat" and waves away Fanny's feeble resistance. Thus, Austen inexorably subverts and intertwines the themes of imperialism and resistance; of conqueror and conquered.

The word "survey" is pointedly used by Austen again in the Portsmouth scenes, but only after Henry Crawford has arrived there. Henry and Fanny are walking around the docks from which England's imperialist fleet sailed: "they were very soon joined by a brother lounger of Mr. Price’s, who was come to take his daily survey of how things went on." And of course the imperialist forces "went on" to the four corners of the earth, with Fanny as supine witness. But she is more than a mere witness at Mansfield, that is to say, Man's field , where everything and everyone is brought under patriarchal dominion. We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit “She could say nothing”

We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit “She could say nothing”

One by one, the characters of Mansfield Park fall in line with the agenda of capitalist-based agriculture and imperial exploitation. Austen adds a further layer of bleak irony when she presents Fanny, in chapter 16, becoming a colonizer herself as the colonizer of the East Room: (emphasis added) “[Fanny] had added to her possessions, and spent more of her time there; and having nothing to oppose her, had so naturally and so artlessly worked herself into it, that it was now generally admitted to be hers. The East room, as it had been called ever since Maria Bertram was sixteen, was now considered Fanny’s, almost as decidedly as the white attic.”

It is in the East Room that Edmund surprises Fanny with the gift of “a plain gold chain, perfectly simple and neat” as from one surveying conqueror to another. She is stunned into almost open revolt by the symbolic associations of such a “gift.” She stammers, “I cannot attempt to thank you… thanks are out of the question. I feel much more than I can possibly express.”

But this is the last flicker of resistance. Fanny Price embraces the values of Mansfield Park at the price of her independence, even at the price of her voice. From the middle of Chapter 46 to the end of the novel--11,560 words--Fanny speaks only three times. Some people speak to her, we are told by the narrator that Fanny answers: (“believing herself required to speak”) but we seldom hear Fanny’s own words. She is groomed to silence, acquiescence and complicity.

The ending of Mansfield Park is unparalleled for its concluding irony, in which Austen can be properly understood as meaning the opposite of the actual words on the page. By giving Mansfield Park such an inarticulate and silenced "heroine," Austen shows us that the narrative force of the novel derives from that which cannot be said. William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise *I would never suggest that a writer of Austen’s subtlety cannot intend more than one meaning, as in the word "suffer." Prior scholarship has established that the “Moor Park” apricot tree--of which Mrs. Norris is so proud--refers not merely to a well-known English estate called "Moor Park,” named after an adjoining moorland, but is an undeniable signifier of the slave trade, because Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor. Thus apricots are a stark reminder of chattel slavery.

William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise *I would never suggest that a writer of Austen’s subtlety cannot intend more than one meaning, as in the word "suffer." Prior scholarship has established that the “Moor Park” apricot tree--of which Mrs. Norris is so proud--refers not merely to a well-known English estate called "Moor Park,” named after an adjoining moorland, but is an undeniable signifier of the slave trade, because Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor. Thus apricots are a stark reminder of chattel slavery.

But in addition, the reference to “moors” weaves Mansfield Park together with the Treatise, with its references to "inclosure" and "improvement": “if moors, marshes, bogs, heaths, shallows, pools of water, shrubs or rocks, belong to and adjoin the estate, measure what is improvable first; and if any of the rejected part will admit of improvements, measure and return it as such; the remainder should appear in your map as unprofitable ground.”

The assonance between “moor” and “more” ratifies the connection between agriculture and imperialism. "Moors” are not always "improvable," and if not improvable, are "unprofitable." We instinctively recoil from the capitalism of "profit."

the hermeneutics of the cross and the chain in Mansfield Park

A special guest editorial by Aprille Stulti, Ph.D.

“I cannot look out of my dressing-closet without seeing one farmyard, nor walk in the shrubbery without passing another,” Mary Crawford complains in Mansfield Park. Modern readers have often missed or misunderstood Austen's critical stance on the agricultural revolution and the growth of the British empire. On the surface, we see Mary, a quintessential city girl, surprised to find that she is not able to hire a horse and wagon to transport her harp to the parsonage. But a closer interrogation of the text reveals that Jane Austen was working both with and against Mary Crawford’s seeming ignorance of the realities of agricultural life.

“I cannot look out of my dressing-closet without seeing one farmyard, nor walk in the shrubbery without passing another,” Mary Crawford complains in Mansfield Park. Modern readers have often missed or misunderstood Austen's critical stance on the agricultural revolution and the growth of the British empire. On the surface, we see Mary, a quintessential city girl, surprised to find that she is not able to hire a horse and wagon to transport her harp to the parsonage. But a closer interrogation of the text reveals that Jane Austen was working both with and against Mary Crawford’s seeming ignorance of the realities of agricultural life.This essay will contend that a close reading of language in Mansfield Park—especially of such seemingly innocuous words such as “survey” and “yield”—reveals Austen’s counter-reaction to agricultural development. Mary Crawford is not merely trying to hire a horse, she is protesting the encroachment of capitalist-based agriculture, which ironically supports the prosperity of her own gentry class. Mary is paradoxically presented as both victim and beneficiary--and finally perpetrator--of imperialist violence.

This essay will explore how key scenes in Mansfield Park, especially those concerning the amber cross and chain, might adumbrate Austen's resistance to her times...

William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722 "A Full Survey of Her Face"

William Leybourn's "The Compleat Surveyor" 1722 "A Full Survey of Her Face"Fanny Price, the heroine/hostage of the novel, is associated with surveying immediately upon her arrival at Mansfield Park; we are told that the young Bertram sisters, Maria and Julia, “were soon able to take a full survey of her face and her frock in easy indifference.”

A “survey” of Fanny inevitably associates this vulnerable girl in the readers' mind with the imposition of invisible boundaries on open space. The language that describes Fanny's "yielding" is the language of land surveying, cultivation and conquest. It is not insignificant that farmers spoke of “breaking” the land with a plow. Fanny, too, will be cultivated, transformed into a genteel young lady. She is forced to yield to the will of others, just as farmland yields crops: Repeatedly we are told Fanny is "obliged to yield," or "she must yield."

From this introductory chapter, until we come to the Sotherton episode, the references to surveying and improvement are few. However, the more obliquely Austen refers to surveying, the more important it is to our understanding of the novel. Within that negative space created by Austen, the idea of the imposition of control is pointedly invoked by the name of Dr. Grant, the resident clergyman of Mansfield, and the host to Mary Crawford and her brother Henry. Dr. Grant's name is highly suggestive of grants of land, as from a sovereign to a loyal subject. The Grants, significantly, also busy themselves in extending and improving their property. They have “carried on the garden wall, and made the plantation to shut out the churchyard.” This last comment comes from Mrs. Norris, who is "excessively fond" of "planting and improving."

Surveying returns “as the particular object” when the young people go to Sotherton. “How would Mr. Crawford like, in what manner would he chuse, to take a survey of the grounds?" As the print from "The Compleat Surveyor" (above) indicates, surveying was presented as a benign activity carried out by little cherubs, but Austen deploys Henry's survey of the grounds ironically as a powerful metaphor of the tyranny of land ownership.

Of all of the characters, Henry Crawford is most associated with surveying.And before long, Henry's predatory gaze falls upon Fanny.

Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra The Cross, the Necklace, and the Chain

Austen's sailor brother Charles gave crosses to Jane and Cassandra The Cross, the Necklace, and the Chain"He loves to be doing," his sister says proudly (and suggestively) of her brother's fondness for "improvements." The oppressive heteronormativity and patriarchy of Henry Crawford’s flirtatious games are intertextually allied to surveying and land use through the material objects of the cross and chain in Chapter 26 of Mansfield Park.

The cross and chain were taken at face value by previous generations of Austen scholars; the amber cross was a symbol of the faith practiced by Fanny Price and her creator, and is especially valued by Fanny as a gift from her beloved brother William. The chain is from Edmund, the man she secretly loves, and it enables her to wear the cross. Austen tells us that Edmund’s chain and cross together are “memorials of the two most beloved of [Fanny’s] heart, those dearest tokens so formed for each other by everything real and imaginary.”

But of course, Austen's intent here is ironic. This truth has been acknowledged in post-colonial Austen scholarship for over thirty years. No-one today supposes that Mansfield Park is a love story, that Fanny could possibly love Edmund, or be proud of her colonizing brother William the sailor.

It is agreed that Austen is subverting something with the cross and chain, but opinions still differ as to exactly what she is subverting. One scholar has argued that the chain represents slavery, and the cross represents the Church of England’s complicity in slavery through its ownership of the Codrington plantations. Others have seen a straightforward sexual inference. Henry Crawford’s ornate necklace “would by no means go through the ring of the cross… it was too large for the purpose.” Edmund’s (presumably smaller) “chain” does fit through. It goes without saying that any object that is longer than it is wide is an encoded sexual symbol, but I intend to extend and contest the existing interpretations.

Surveying and Suffering

Surveying and Suffering

In fact, the chain and the cross together are the tools of the land surveyor, as Austen’s contemporaries would have instantly recognized. In encountering Mansfield Park, they would undertand the remarkable similarities with A Complete Treatise on Land Surveying, by the Chain, Cross and Offset Staffs Only (1798), parallels that critics have not previously noted.

The Treatise is described by the Dictionary of National Biography as a “a popular work which went through five editions by 1813,” which means it preceded, was better known, and was more widely-read than Mansfield Park (published in 1814.)

Space permits only a few examples of the intertextual relations between Mansfield Park and the Treatise. The Treatise states (emphasis added): “Suffer your chain leader to go no farther than the nearer side of the ditch... the ditch being the property of the next field.” Paradoxically, Austen camouflages the allusion by never using the word “ditch” in Mansfield Park; she substitutes the word “ha ha.” This interior joke must have afforded much grim and ironic amusement.

“Suffer” in this sense it means “to permit or allow.”* Edmund, significantly, invokes the term suffering in the scene at the chapel at Sotherton when he ostensibly defends public worship over private prayer: “Do you think the minds which are suffered, which are indulged in wanderings in a chapel, would be more collected in a closet?” Edmund wants anyone capable of independent thought to be "collected," preferably in a place where he can keep an eye on them. Even this chilling pronouncement does not shake Fanny’s misguided loyalty to Edmund.

We move from this unsettling scene to one even more distressing: Edmund argues with Mary Crawford as they walk in the wilderness. And what topic, out of all the topics in the world, are they arguing about? The extent of the wilderness! They have both visually surveyed the wilderness, an artificial simulacrum of unimproved land, and disagree about its extent. Mary says “with feminine lawlessness” that the unconquered area is vast, while Edmund “attacks” her and attempts to “dictate” to her, to force her to acknowledge that the remaining uncultivated land “could not have been more than a furlong in length.”

“Oh! I know nothing of your furlongs,” Mary protests, but before long, she herself becomes complicit when she places Henry's necklace, or rather, his chain, around Fanny's "lovely throat" and waves away Fanny's feeble resistance. Thus, Austen inexorably subverts and intertwines the themes of imperialism and resistance; of conqueror and conquered.

The word "survey" is pointedly used by Austen again in the Portsmouth scenes, but only after Henry Crawford has arrived there. Henry and Fanny are walking around the docks from which England's imperialist fleet sailed: "they were very soon joined by a brother lounger of Mr. Price’s, who was come to take his daily survey of how things went on." And of course the imperialist forces "went on" to the four corners of the earth, with Fanny as supine witness. But she is more than a mere witness at Mansfield, that is to say, Man's field , where everything and everyone is brought under patriarchal dominion.

We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit “She could say nothing”

We must inevitably see Fanny as complicit “She could say nothing”One by one, the characters of Mansfield Park fall in line with the agenda of capitalist-based agriculture and imperial exploitation. Austen adds a further layer of bleak irony when she presents Fanny, in chapter 16, becoming a colonizer herself as the colonizer of the East Room: (emphasis added) “[Fanny] had added to her possessions, and spent more of her time there; and having nothing to oppose her, had so naturally and so artlessly worked herself into it, that it was now generally admitted to be hers. The East room, as it had been called ever since Maria Bertram was sixteen, was now considered Fanny’s, almost as decidedly as the white attic.”

It is in the East Room that Edmund surprises Fanny with the gift of “a plain gold chain, perfectly simple and neat” as from one surveying conqueror to another. She is stunned into almost open revolt by the symbolic associations of such a “gift.” She stammers, “I cannot attempt to thank you… thanks are out of the question. I feel much more than I can possibly express.”

But this is the last flicker of resistance. Fanny Price embraces the values of Mansfield Park at the price of her independence, even at the price of her voice. From the middle of Chapter 46 to the end of the novel--11,560 words--Fanny speaks only three times. Some people speak to her, we are told by the narrator that Fanny answers: (“believing herself required to speak”) but we seldom hear Fanny’s own words. She is groomed to silence, acquiescence and complicity.

The ending of Mansfield Park is unparalleled for its concluding irony, in which Austen can be properly understood as meaning the opposite of the actual words on the page. By giving Mansfield Park such an inarticulate and silenced "heroine," Austen shows us that the narrative force of the novel derives from that which cannot be said.

William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise *I would never suggest that a writer of Austen’s subtlety cannot intend more than one meaning, as in the word "suffer." Prior scholarship has established that the “Moor Park” apricot tree--of which Mrs. Norris is so proud--refers not merely to a well-known English estate called "Moor Park,” named after an adjoining moorland, but is an undeniable signifier of the slave trade, because Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor. Thus apricots are a stark reminder of chattel slavery.

William Davis (1771-1807), author of The Treatise *I would never suggest that a writer of Austen’s subtlety cannot intend more than one meaning, as in the word "suffer." Prior scholarship has established that the “Moor Park” apricot tree--of which Mrs. Norris is so proud--refers not merely to a well-known English estate called "Moor Park,” named after an adjoining moorland, but is an undeniable signifier of the slave trade, because Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor. Thus apricots are a stark reminder of chattel slavery.But in addition, the reference to “moors” weaves Mansfield Park together with the Treatise, with its references to "inclosure" and "improvement": “if moors, marshes, bogs, heaths, shallows, pools of water, shrubs or rocks, belong to and adjoin the estate, measure what is improvable first; and if any of the rejected part will admit of improvements, measure and return it as such; the remainder should appear in your map as unprofitable ground.”

The assonance between “moor” and “more” ratifies the connection between agriculture and imperialism. "Moors” are not always "improvable," and if not improvable, are "unprofitable." We instinctively recoil from the capitalism of "profit."

Published on April 01, 2022 00:00

March 28, 2022

CMP#95 Chains of Love

Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#95 Chains of Love: did Austen have a potty mouth and a dirty mind?

Modern readers who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. CMP#95 Chains of Love: did Austen have a potty mouth and a dirty mind?  "'It's well hung." "Wait, what?" I’m going to do some heavy-duty pearl-clutching in this post, as I fall back on my fainting couch after having read Jane Austen’s Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History (2005) by Jill Heydt-Stevenson.

"'It's well hung." "Wait, what?" I’m going to do some heavy-duty pearl-clutching in this post, as I fall back on my fainting couch after having read Jane Austen’s Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History (2005) by Jill Heydt-Stevenson.The “subversive laughter” of the title refers to Heydt-Stevenson’s thesis that Austen’s novels, so genteel on the surface, are actually full of humorous sexual imagery which she included not only for its own sake but to subversively undermine the patriarchy.

That is my restatement of her thesis. In her own words, as stated in article in Nineteenth-Century Literature: "Specifically, Austen's bawdy irreverence becomes part of a radical critique of courtship as she closes the gap between fallen women and proper ladies, critiques sensibility's ideological sentimentalization of prostitution, and undermines patriarchal modes of seeing."

Heydt-Stevenson finds many examples of sexual double entendre in Austen. I won't dispute her about Mary Crawford’s “rears and vices,” which sure looks like a sodomy joke, although it bewilders me that Austen would do that, but apparently when Austen uses words like “make” and “tumble" she is hinting at sexual intercourse. (By the way, this post is not exactly g-rated)...

For example, when John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey says his carriage is “well hung” he really means.... Un-hunh, get it? Of course you do. According to Heydt-Stevenson, It would not be possible for a young man to boast about the suspension in his carriage without being understood to also be speaking of large penises.

For example, when John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey says his carriage is “well hung” he really means.... Un-hunh, get it? Of course you do. According to Heydt-Stevenson, It would not be possible for a young man to boast about the suspension in his carriage without being understood to also be speaking of large penises. It's true that during Austen's lifetime, you could purchase bawdy or even explicit material. But what about context? What about taking your intended audience into consideration? When readers of Austen’s time consulted a cookbook and read, “Take a loin of mutton that has been well hung,” did they always snicker? When we hear the phrase “happy ending” used in relation to a fairy tale, it means that the prince is marrying Snow White. When we hear the phrase used in relation to a massage parlor called “The Garden of Eden,” it means something else.

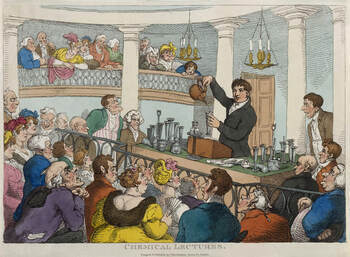

We think of the past as a time when female sexuality was repressed, or it was denied that women had sexual urges at all (with some exceptions, as we see in the 1825 satirical print below which includes a visual double entrendre for "muff.")

"I wish I had I know what, And I know who could give me, I wish I was I know where, And I know who was with me." However, by asserting that Austen had a potty mouth and a dirty mind, Heydt-Stevenson is not aligning Austen with bold, confident and bawdy women in literature like Chaucer’s Wife of Bath or Shakespeare’s

servant girls

. No--the sexually-charged allusions are really subversive “protests against patriarchal privilege.”

"I wish I had I know what, And I know who could give me, I wish I was I know where, And I know who was with me." However, by asserting that Austen had a potty mouth and a dirty mind, Heydt-Stevenson is not aligning Austen with bold, confident and bawdy women in literature like Chaucer’s Wife of Bath or Shakespeare’s

servant girls

. No--the sexually-charged allusions are really subversive “protests against patriarchal privilege.” According to Heydt-Stevenson, Austen sees courtship is just another word for sexual barter. Austen "exposes the patriarchal/heterosexual world of conventional courtship as a dangerous, violent, and even life-threatening arena for both men and women," in fact. And here you thought you were reading a novel with a happy ending.

To recap: the assertion that Austen was subverting the patriarchy hangs on the first assertion that Austen's novels are filled with double entendres, and I am not convinced by the first assertion. I don’t think it’s beyond dispute, anyway.

Ironic usage? The Cross, the Necklace and the Chain

Ironic usage? The Cross, the Necklace and the ChainHaving laid out Heydt-Stevenson's thesis, let's move on to compare her interpretation of the amber cross and gold chain in Mansfield Park with the interpretation put forward in Jane Austen: the Secret Radical by Helena Kelly. Elsewhere, I've written about Kelly's assertion that the cross gifted to Fanny by her brother and chain given to her by Edmund represent the Codrington plantations, owned by the Church of England. (Austen uses "chain" to distinguish Edmund's gift from the Crawfords' "necklace." What other word could she have used? "Chain" is the word for the thing people hang crosses around their necks with.) Kelly argues that although Austen tells us Fanny unequivocally loves William and Edmund and she loves her gifts, we, the reader, should be thinking of the hypocrisy of the church, the sins of empire, and the misery of enslaved persons.

Did Austen intend to blend Fanny's tender feelings of affection with the horrors of chattel slavery? Is Austen using the cross and chain as Madonna has irreverently used the crucifix--for its shock value?

Many of Austen's readers were women who wore crosses and chains as emblems of their faith, not as mere decoration. It's likely that many of those women were gifted their crosses by family members, like a grandparent. Why would the cross and chain represent slavery only inside the pages of Mansfield Park? What were women who wore the cross and chain supposed to think of themselves? Does every cross remind us of the Codrington plantations or only the crosses suspended on a chain? What about crosses on coral beads or strings of pearls? Whenever Ackerman's Repository showed a fashion plate of a lady wearing a cross, was that publication sending a message?

Many of Austen's readers were women who wore crosses and chains as emblems of their faith, not as mere decoration. It's likely that many of those women were gifted their crosses by family members, like a grandparent. Why would the cross and chain represent slavery only inside the pages of Mansfield Park? What were women who wore the cross and chain supposed to think of themselves? Does every cross remind us of the Codrington plantations or only the crosses suspended on a chain? What about crosses on coral beads or strings of pearls? Whenever Ackerman's Repository showed a fashion plate of a lady wearing a cross, was that publication sending a message? And finally, what is the message? By wearing the cross and chain, is Fanny complicit in slavery, or is she protesting it?

Ostentatious mourning How does the notion that the chain and cross represent something dark and terrible make sense narratively or symbolically? As Austen states in the text, Fanny is delighted to be wearing the cross and chain. She loves the men who gave her the cross and chain. Nothing bad happens to or with the cross and chain. Henry's necklace, on the other hand, makes Fanny uncomfortable--and Austen says so.

Ostentatious mourning How does the notion that the chain and cross represent something dark and terrible make sense narratively or symbolically? As Austen states in the text, Fanny is delighted to be wearing the cross and chain. She loves the men who gave her the cross and chain. Nothing bad happens to or with the cross and chain. Henry's necklace, on the other hand, makes Fanny uncomfortable--and Austen says so. Instead of a slavery connection, the cross and necklace have sexual implications for Heydt-Stevenson (naturally). The amber with which the cross is made is smooth and sensual. In the episode when Fanny consults Mary about her attire for the upcoming ball, Austen lets us know that Fanny is uneasy when Mary offers to give her a necklace. She feels something is not quite right. Fanny reluctantly takes the necklace but discovers that Henry’s necklace is too big to fit through the ring of William’s cross.

Well, that was too easy, right? That’s nothing! Wait until you read Maria Edgeworth’s The Absentee (1812) and get to the part about Lord Colombre “ejaculating over one of Miss Nugent’s gloves.”

Mary later confesses that Henry put her up to it: "It was his own doing entirely, his own thought. I am ashamed to say that it had never entered my head, but I was delighted to act on his proposal for both your sakes.”

The Crawfords were duplicitous because they knew that Fanny's delicacy would prohibit her from receiving a gift from a man. As culpable as they are however, Heydt-Stevenson's description of the episode makes me want to defend them! In her hyperbolic interpretation, Mary's references to Fanny's "lovely throat" are "sly violence," she's a "bawd," (meaning she's grooming Fanny), she "objectifies" Fanny "sexually," Fanny is a "purchasable item," "Henry's chain [necklace, actually] becomes a painfully obvious signifier of entrapment," etc., etc. And is Mansfield Park the only novel which has used the material object of a cross and a chain for narrative purposes? I found another example, a 1811 sentimental short story translated from the French. A long-lost son finds his mother and he gives her a cross and chain, a gift from his wife which was intended for his sister, who he discovers has died. Everybody cries.

Okay, so does this mean that the sister was a slave or a sexual object? Or the wife? Or the mother? Why is nobody pestering deep meanings out of Marcellus, or the Old Cottager?

If popular songs of the last century could use lyrics like "My baby's got me locked up in chains" then surely it was possible that a writer of 200 years ago might use the word "chain" in reference to jewelry without drawing down the assumption that it's a covert protest of chattel slavery or a reference to the commodification of female sexuality. Problematic: "So tighter! Pull them tighter! 'Til I feel that sweet pain. 'Cause these chains of love keep me from going insane." Certainly the word "chain" as a noun and a verb has been used for millenia when discussing slavery, but there are other kinds of chains. As well, I concede that in Austen's time, it was not uncommon to speak of love in terms of slavery. Mary Crawford blithely speaks of her brother glorying in his chains.

But the cross represents the sacrifice and resurrection of Jesus and the promise of salvation for the faithful, or as Heydt-Stevenson puts it, the cross has "spiritual connotations." She notes that "Austen does not emphasize" those connotations. However, a writer crafting novels for the general public in the early 19th century would think twice before publishing something that associates the cross of Christianity with sex. And then they wouldn't do it, because if they did, there would be outrage. Or, if Austen did intend it, she could have thanked her lucky stars that nobody "got" the sexual allusion for two hundred years. I’ve written a lot about the Kelly hypothesis that Austen was a radical. I would sum up Heydt-Stevenson by saying that in my opinion her central assertion-- bawdy humour means Austen is subverting the patriarchy --is poorly supported by argument. There's a lot of vague academic talk about "doubling" and "subverting" and "irony," but basically it is Heydt-Stevenson's assertion that this or that bawdy allusion (supposing Austen intended one) would cast a straight line in the readers' mind to thoughts of the inherent violence of the patriarchy.

Yes, there was plenty of bawdy humour around, especially in Georgian times, but Austen was a lady. Ladies didn't make coarse jokes in public. Nor did Austen take as bleak a view of the relations between the sexes as Heydt-Stevenson ascribes to her. I will not crawl over everything I object to in Heydt-Stevenson's book, but I am going to do a deep dive on two other arguments from Unbecoming Conjunctions in future. Problematic:

Chains, well, I can't break away from these chains

I can't run around / Cause I'm not free

Whoa, oh, these chains of love Won't let me be, yeah Heydt-Stevenson lays out her theories in “‘Slipping into the Ha-Ha’: Bawdy Humor and Body Politics in Jane Austen’s Novels.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 55, no. 3 (2000): 309–39 and in her book, Jane Austen's Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History. United Kingdom, Palgrave Macmillan US, 2016.

The sexualized interpretation of putting a chain through the ring of the cross originated in an article by Alice Chandler: "However, no one to my knowledge has pointed out that the rakish Henry Crawford's chain is too big to fit through the hole in Fanny's cross but that her beloved Edmund's chain slips through quite nicely." Chandler. (2019). "A Pair of Fine Eyes": Jane Austen's Treatment of Sex. Studies in the Novel, 51(1), 36–50.

Kelly, Helena. Jane Austen, the Secret Radical. United States, Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

Published on March 28, 2022 00:00

March 21, 2022

CMP#94 Seraphina, the lively heroine

“Here I am once more in this scene of dissipation and vice, and I begin already to find my morals corrupted."

“Here I am once more in this scene of dissipation and vice, and I begin already to find my morals corrupted."-- Jane Austen in a letter from London, August 1796 CMP#94 Better Late Than Never: A Book Review for Seraphina, or A Winter In Town

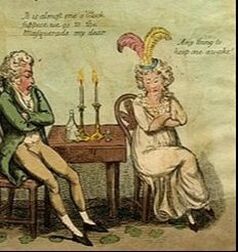

Fashionably late Londoners: "It is almost one o'clock, suppose we go to the Masquerade?" Scholar Anne Hawkins estimates that almost five hundred women brought out novels between 1789 and 1824. One of those women was Jane Austen, whom you might have heard of. Another was Caroline Burney, author of Seraphina, or A Winter in Town (1809), who you probably haven't.

Fashionably late Londoners: "It is almost one o'clock, suppose we go to the Masquerade?" Scholar Anne Hawkins estimates that almost five hundred women brought out novels between 1789 and 1824. One of those women was Jane Austen, whom you might have heard of. Another was Caroline Burney, author of Seraphina, or A Winter in Town (1809), who you probably haven't.One proviso: we can’t be certain that Caroline Burney was a woman. The name is probably a pseudonym, an attempt to cash in on the fame of Frances Burney and her half-sister Sarah Harriet Burney. When Sarah Harriet’s publisher brought out Traits of Nature, he advertised: “'The publisher of this Work thinks it proper to state that Miss Burney is not the Author of a Novel called "Seraphina," published in the year 1809, under the assumed name of Caroline Burney.” Well, Caroline Burney identified as a female, so that should be good enough for our purposes.

In addition, the subtitle A Winter in Town is an echo of the best-selling A Winter in London by Thomas William Surr, which I reviewed here. According to scholar Chris Stevens, Surr’s novel created such a sensation that it briefly inspired its own “microgenre,” the “Season” novel, meaning of course the social season in London, Bath, Brighton, or wherever. These “Season” novels featured wealthy and titled characters behaving badly. Sometimes these portraits were obviously based upon real people, which added to the appeal of the books. London as a sinkhole of vice was such a popular theme in novels that Jane Austen jokes about it in a letter to her sister Cassandra, quoted above.

Some of the older novels I’ve been reading were reviewed in their day, but many came out to no fanfare, and Caroline Burney’s three-volume effort is one of those. So, out of fellow-feeling for these neglected authoresses, I’m instituting an occasional series of book reviews for novels that never got a book review. This post, (I think), is the very first review of Seraphina, or A Winter in Town...

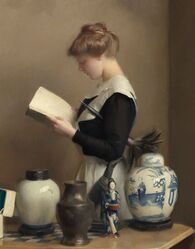

Beautiful blushes: Mrs Russell (nee Cox) by John Smart, 1781 A Lively Heroine

Beautiful blushes: Mrs Russell (nee Cox) by John Smart, 1781 A Lively HeroineWe first meet Seraphina, a beautiful, high-spirited girl, as she carries a basket of clothes to the poor of her quiet Welsh village. She is not a sensitive, weeping, fainting, fluttering, “picture of perfection” heroine but I suppose that's because her situation is not dire. She is a foundling but she has an inheritance. She loves her foster-parents and she’s not particularly curious about how she came to be in their care one mysterious night in London when she was a baby.

Her foster-father Dr. Melbourne resolves to bring her to London to establish her true identity although he's very anxious about exposing his lovely, innocent ward to the depravity of town. His wife assures him: “Seraphina is not of the common cast; her mind is too well stored with elegant resources, and her heart too strictly guarded by delicacy, to yield to the puerile temptations of fashion and folly.”

Seraphina's neighbour Edward Pembroke has been like an older brother to Seraphina. He helped educate her, just as Edmund Bertram educated Fanny Price, and he occasionally rebukes her like Mr. Knightley admonishes Emma. “In all these little contests the mild steadiness of Edward’s temper triumphed over the vivacity of Seraphina’s, and although she would not always acknowledge that she thought him right, her prompt correction of the fault he had censured, evinced the respect she felt for his opinion, and never failed of obtaining for her the approbation she secretly wished for.”

Edward is also very worried about the snares of London. What if Seraphina is caught up in the vortex of dissipation like his sister Sophia? “Oh Seraphina! Happy thoughtless being, how little do you dream of the anxiety that throbs within this bosom upon your account! However, I will warn her of the precipice she stands upon; and if for one moment she can be serious, perhaps the impression may be indelible.”

While Seraphina is quite intelligent in most respects she doesn't realize that Edward is madly in love with her. In fact, she protests, “Edward… is the last person in the world that would think of me in that light; why, he does nothing but find fault with me from morning till night. My lessons were never perfect enough for him…” We must excuse her, however, and blame her obtuseness on the conventions of the romantic novel.

Seraphina and Dr. Melbourne stay with Lord and Lady Avondale (Sophia Pembroke as was) and Seraphina is launched into the fashionable world. Despite the extensive foreshadowing mentioned above, Seraphina is never tempted by the vortex of vice. Our heroine goes to the opera to see the (real life) diva Catalani, but she recoils from the late hours of society and refuses to play cards. She laughingly parries the overblown gallantry of some foppish courtiers. "There was a witchery in her gaiety that was irresistible;

for her wit

so playfully delicate, was pointed without being severe; it had the rare talent of delighting the ear without wounding the heart.”

Seraphina and Dr. Melbourne stay with Lord and Lady Avondale (Sophia Pembroke as was) and Seraphina is launched into the fashionable world. Despite the extensive foreshadowing mentioned above, Seraphina is never tempted by the vortex of vice. Our heroine goes to the opera to see the (real life) diva Catalani, but she recoils from the late hours of society and refuses to play cards. She laughingly parries the overblown gallantry of some foppish courtiers. "There was a witchery in her gaiety that was irresistible;

for her wit

so playfully delicate, was pointed without being severe; it had the rare talent of delighting the ear without wounding the heart.” Her hostess Lady Avondale is addicted to gaming, and takes advantage of Seraphina's naivete by borrowing every guinea she has. Dr. Melbourne takes Lord Avondale to task for not keeping his wife under control. “My dear Dr. Melbourne,” answered Lord Avondale, “what can I do? I should be lampooned and ridiculed in every society, were I to pretend to prescribe rules for the conduct of my wife whilst she keeps within the bounds of decorum.”

The Dandy's Toilette The Other Characters

The Dandy's Toilette The Other CharactersThere are a number of secondary characters who are not deployed to maximum advantage. They are briefly introduced as recognizable stock characters (the fop! the sprightly sidekick!) but they are given little or nothing to do.

There’s also Edward and Lady Avondale's sister Fanny, a sweet-tempered auxiliary heroine languishing back in Wales. Their sailor brother Robert drops by as well but it’s hard to see why, unless as an excuse to touch upon current events, ie, the war against “Bony.” “There was something so droll and good-humoured in the honest sailor… although Lady Avondale could not help wishing he was a little more refined, yet as he was much talked of for his late exploits at sea, she felt gratified in being pointed out as the sister of the celebrated naval hero.”

Sir Effingham Wilson, another minor character, is an older man who makes himself ridiculous by dressing like a young buck. Seraphina can’t help laughing at him because “as he disclaimed the reverence due to old age by his foppery, my usual inclination to laugh at whatever is ridiculous, will certainly prevail.”

As is often the case with novels of this era, (but seldom with Austen) servants serve as devices for exposition. Old Peter laments how London has turned Sophia Pembroke into the decadent Lady Avondale: “I should never have guess it was our Miss Sophia as was, for lack-a-daisy! how she was painted, if she had blushed ever so, you could not have seed it…” Servants are also essential for furthering or thwarting the evil intentions of their employers. Lady Avondale instructs her lady's maid to get her hands on Seraphina’s jewels so she can exchange them for fakes. Another knock against Lady Avondale’s character, which contemporary audiences would have understood, is that she gossips with and confides in her maid. Seraphina, by contrast, refuses to let her maid gossip about Lady Avondale.

There are a few characters who are more fully drawn. Seraphina’s foster-father Dr. Melbourne is eccentric and humorous at home, but switches to being a severe moralizer in London. A typical reflection: “How much more painful is it to tread the crooked mazes of vice and folly, beneath the roses that adorn that deceitful labyrinth, lurk the serpent’s remorse, repentance, and unpitied anguish, ready to punish with their stings the errors of the thoughtless crew that tread their forbidden haunts.”

There is also a love-rival for Edward in the form of Lord Claredown, a Henry Crawford type. “Numberless innocent unsuspecting hearts had been beguiled of all their happiness long ere they were aware of the danger that awaited them. Several victims had sunk into premature graves, and others had sought revenge for his perfidy [by marrying] the objects of their aversion.” This reminds us of how Maria Bertram married Mr. Rushworth rather than admit that Crawford had scorched her heart. Spoilers Follow

Seraphina is drawn to the sexy and magnetic Claredown until she realizes he’s the man who broke her friend Fanny’s heart, “and he who could trifle with her happiness, shall never endanger mine.”

Lord Claredown is not the only man who is attracted to Seraphina, even before her true identity is known. When Sir Effingham proposes marriage, she is so astonished that she “was unable to answer for some minutes.” When he tries to “construe her silence into an assent to his proposals,” Seraphina “could no longer command herself, but burst into a fit of laughter.” Seraphina is oblivious to the growing evidence that she is the long-lost daughter of Lady Cremona, who died under mysterious circumstances. Almost everywhere she goes in London, someone sees her and gasps in surprise, because she is the perfect image of her late mother. I was reminded of the comic sequence in Kung Fu Panda 3 when Po meets his father. Although Seraphina’s not so good at putting two and two together where her own interests are concerned, she is resolute and courageous when she is abducted by some treacherous Italians (are there any other kind?) who want to replace her, the true heiress, with an imposter. The entire truth about the Cremona mystery comes out through a series of remarkable coincidences and Seraphina's noble parentage is revealed. This is another blow to Edward's hopes for winning her hand, for, in addition to the gap in fortune between them, there is the wide gulf of social class. The first problem is solved at a stroke when a rich uncle with an East Indies fortune makes Edward his heir. (This is a frequently used device in novels of this era). The social gulf remains. Seraphina solves this problem by telling Edward that she loves him. Essentially, she proposes to him, though of course she is blushing madly while doing so. I’m going to have to do another post about the incredible amount of attention that blushes get in the literature of this period.

Edward and Seraphina are married, and other minor characters are also matched in matrimony in a swift summing-up. Vice Confounded and Virtue Rewarded

I’d say three and a half stars out of five for Seraphina. I'm not judging it against great literature but how it stacks up against other novels of the same genre. While the author misses out on some possibilities, and the coincidences are so frequent and improbable as to be comical, the heroine isn’t insipid and the action moves briskly. An 18th-century book reviewer would add that virtue is rewarded and the dissipated characters repent and reform.

Although Seraphina didn't get a book review, we know that it was available at 9 of 22 circulating libraries throughout the kingdom, according to the British Fiction database ,

Novels like A Winter in London may be obscure, but every novel I read teaches me more about the tropes and literary conventions of Austen's time and how she related to them. It also teaches me about how Regency England saw itself, and how novels prescribed ideal conduct for men and women. No doubt reality was far different from novels (this was something that Austen laughed about) but it's interesting to explore the expectations that abounded in the literature of the day. In future, I'll be talking about a different kind of heroine than the lively Seraphina: the "bear and forbear" heroine. I’m always amused when I think of the argument that Pride & Prejudice was a revolutionary novel because of its critical portrayal of the aristocratic Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Novelists of the long 18th century made their bread and butter by criticizing the aristocrats.

Here's an earlier post I wrote about blushing girls and how it is still a thing in China, where I lived for four years.

Lorna Clark quotes Anne Hawkins in "The Literary Legacy of Sarah Harriet Burney." Eighteenth-Century Life 1 April 2018; 42 (2).

Rachel Howard, Domesticating the Novel : Moral-Domestic Fiction, 1820-1834. 2007.

Chris Stevens, "The Season Novel, 1806-1824: A Nineteenth-Century Microgenre." Victoriographies, (2017), 7(2), 81–100.

Published on March 21, 2022 00:00

March 14, 2022

CMP#93 The Right of a Lively Mind

"Your wit and vivacity, I think, must be acceptable to [Lady Catherine de Bourgh], especially when tempered with the silence and respect which her rank will inevitably excite." -- Mr. Collins to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice

CMP#93 The Endowments of Wit and Talent

In earlier posts in my series on Mansfield Park and education, I discussed innate qualities like disposition and understanding. Now I'd like to circle back to the qualities of wit and cleverness. In Fanny Price we see a heroine with no aptitude for wit contrasted with the delightfully witty Mary Crawford. No wonder so many people prefer Mary to Fanny.

"Your wit and vivacity, I think, must be acceptable to [Lady Catherine de Bourgh], especially when tempered with the silence and respect which her rank will inevitably excite." -- Mr. Collins to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice

CMP#93 The Endowments of Wit and Talent

In earlier posts in my series on Mansfield Park and education, I discussed innate qualities like disposition and understanding. Now I'd like to circle back to the qualities of wit and cleverness. In Fanny Price we see a heroine with no aptitude for wit contrasted with the delightfully witty Mary Crawford. No wonder so many people prefer Mary to Fanny.Edmund Bertram, the man they both love, disclaims having any wit: "there is not the least wit in my nature. I am a very matter-of-fact, plain-spoken being, and may blunder on the borders of a repartee for half an hour together without striking it out.”

But their creator Jane Austen was very witty. Sly and subtle jokes abound in her private letters and in her novels, even in the more serious Mansfield Park. Her earlier works are hilarious. Why did such a witty author create Fanny Price, a heroine without wit? Why did she create a heroine so unlike herself?

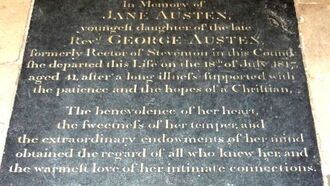

Jane Austen’s memorial plaque at Winchester Cathedral praises the “benevolence of her heart, the sweetness of her temper and the extraordinary endowments of her mind.”

Jane Austen’s memorial plaque at Winchester Cathedral praises the “benevolence of her heart, the sweetness of her temper and the extraordinary endowments of her mind.” Endowment is related to the word dower, as in dowry. Edmund Bertram says regretfully of Mary, "For where shall we find a woman whom Nature had so richly endowed?"

Endowments are gifts from God, and referred to variously as gifts from a Creator, or Providence, or Nature, as in "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights." Today, we might also use the phrase "God-given talents."

To the innate qualities we've discussed in the previous posts, such as understanding, disposition, and temper, we can add qualities or endowments such as artistic ability and wit. Being witty is allied to being quick in apprehension, or being “quick-sighted.” But not everyone appreciated a witty disposition in Austen's time.

Hannah More (1745--1833) Never Trust a Witty Woman

Hannah More (1745--1833) Never Trust a Witty WomanThe influential writer Hannah More argued at length against wit in females in her Essays on Various Subjects: “[T]hose who actually possess this rare talent, cannot be too abstinent in the use of it. It often makes admirers, but it never makes friends.”

“The fatal fondness for indulging a spirit of ridicule," More explains, "and the injurious and irreparable consequences which sometimes attend the too prompt reply, can never be too seriously or too severely condemned. Not to offend, is the first step toward pleasing. To give pain is as much an offence against humanity, as against good breeding…”

More notes that under the rules of gallantry, a gentleman cannot say unkind things of a lady, but women are not so constrained. “It is this very circumstance which renders them more intolerable. When the arrow is lodged in the heart, it is no relief to him who is wounded to reflect, that the hand which shot him was a fair one.”

Another author who disparaged wit was Arabella Argus. In Ostentation and Liberality (1821), the governess opines that “Wit is the union of cultivated intellect with a lively imagination. Of course, we do not expect to meet it in the young. I believe the talent to be most rare; and even where it does exist, I never heard that it added to the happiness of its possessor, or increased the number of friends.”

Austen was not a fan of Hannah More, or at least she had mixed feelings about her. But I believe Austen thought about, the issues that More raises about wit and raillery.

Austen clearly saw that wit in females was not the prescribed ideal in her society. The idealized heroines of the fiction of Austen's day were not witty. Wit was reserved for the wise-cracking female sidekick, and I’ve got more to say about that in this blog post . In her satirical plan of a novel, Austen lampooned these heroines, who are “faultless… with much tenderness and sentiment, and not the least Wit.” Austen’s hypothetical heroine's “friendship [was] to be sought after by a young woman in the same Neighbourhood, of Talents and Shrewdness… but having a considerable degree of Wit, Heroine shall shrink from the acquaintance."

But many of Austen’s own heroines and heroes are witty, like Elizabeth Bennet and Henry Tilney. Some drop a few dry witticisms, such as Elinor “it is not everyone who has your passion for dead leaves" Dashwood. I think even Edmund Bertram has a subtle, dry wit, as when Fanny worries that the others will crow with triumph when he comes down off his high horse and agrees to join the private theatricals. "They will not have much cause of triumph when they see how infamously I act," Edmund responds.

We are told that Emma Woodhouse is "clever," and she is. But Emma's quip at Miss Bates's expense is a turning point in the novel. Miss Bates says of herself: "I shall be sure to say three dull things as soon as ever I open my mouth, shan’t I?" Emma replies: "Pardon me—but you will be limited as to number—only three at once.” After Mr. Knightley rebukes her, Emma realizes that her retort was cruel and thoughtless. Wit can go over the line.

The Crawfords, 1999 movie version The Right of a Lively Mind

The Crawfords, 1999 movie version The Right of a Lively MindIn Mansfield Park, Edmund and Fanny discuss Mary Crawford's wit on several occasions.

Mary had remarked, "What strange creatures brothers are! You would not write to each other but upon the most urgent necessity in the world; and when obliged to take up the pen to say that such a horse is ill, or such a relation dead, it is done in the fewest possible words."

Fanny was peeved at Mary's raillery and later asks Edmund: "And what right had she to suppose that you would not write long letters when you were absent?”

“The right of a lively mind, Fanny," [Edmund answers] "seizing whatever may contribute to its own amusement or that of others; perfectly allowable, when untinctured by ill-humour or roughness; and there is not a shadow of either in the countenance or manner of Miss Crawford: nothing sharp, or loud, or coarse."