Lona Manning's Blog, page 11

May 8, 2023

CMP#142 Plots and Plausibility, Marianne

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.CMP#142 More (Unfounded) Theories about Hidden Stories in Austen

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.CMP#142 More (Unfounded) Theories about Hidden Stories in Austen

Regret

In an earlier post,

I discussed some theories about Austen's plots which struck me as being rather far-fetched. This post is a longer response to one of those theories.

Regret

In an earlier post,

I discussed some theories about Austen's plots which struck me as being rather far-fetched. This post is a longer response to one of those theories.Last year, I attended a talk by Robert Morrison, a prominent expert on Austen and the Regency. (His book, The Regency Years, is an informative and entertaining survey of the Regency period.) I was quite surprised when he floated the theory that Marianne got pregnant in Sense and Sensibility. Further, he didn't claim that this interpretation was his own take on the novel, in which case I wouldn’t raise an objection. He attributes the idea to Jane Austen--he thinks Austen hinted that Marianne got pregnant.

If it was worth Professor Morrison's time to devote a full lecture to this idea, it's worth my time to lay out the reasons why I disagree. And I am glad that mulling over his ideas gave me a good reason to re-read Sense and Sensibility, because I noticed things I hadn't paid any attention to before. That's mostly for my next post. Briefly, my rebuttal is: The text doesn’t support the theory that Marianne got pregnant, but rather contradicts it. The tenor of the times wouldn’t allow for such a book to be published, because you can't have a girl of good family have sex outside of marriage without also being explicit about the consequences which would befall her. The longer rebuttal is below. But first, let's look at the textual evidence in favor of the theory. The timeline of the novel doesn’t contradict the possibility that Marianne had a bun in the oven...

Mrs. Jennings and her daughter Charlotte PalmerHow the timeline works

Mrs. Jennings and her daughter Charlotte PalmerHow the timeline worksSeptember 20-- Marianne and Willoughby meet (according to scholar Ellen Moody’s calendar).

October 30--the planned picnic to view the Whitwell estate and grounds is cancelled by Colonel Brandon’s abrupt departure. Mrs. Jennings wonders if there's a problem with Miss Williams, whom she mistakenly thinks is Brandon’s ‘natural daughter.' This introduces the topic of illegitimacy into the novel. Instead of staying with the rest of the disappointed picnickers, Marianne and Willoughby spend the day together unchaperoned. We are told that they toured Allenham, the home of Willoughby's aged relative Mrs. Smith. Then and now, if a young couple in the first flush of mutual infatuation disappear for hours, what else are we to think?

You could protest that Willoughby wouldn't whisk Marianne into the spare bedroom at Allenham when Mrs. Smith is sitting in the drawing room one floor below and there is a full complement of servants around as well, but let's face it--ardent young lovers will find a place and a time.

Early November--Willoughby leaves abruptly.

Late November--Marianne suspects she is pregnant. She therefore has every reason, in addition to being madly in love, to accept Mrs. Jenning’s invitation to go down to London in hopes of being reunited with Willoughby.

January--Marianne is in her third month of pregnancy in London and expecting to hear from Willoughby every moment. She is anxious, restless and not interested in food. She confides in no-one. She's moody and snappish and barely civil to Mrs. Jennings, who is preoccupied with the birth of her daughter Charlotte's first baby. Marianne and Elinor run into Willoughby, and Marianne’s hopes are shattered when she learns he's engaged to an heiress. Marianne's mother, unaware of her dilemma, thinks it would be better for her to stay in London. In Barton, she would have nothing to do but eat her heart out over Willoughby; London might offer her more diversions.

Colonel Brandon absolves Marianne of wrong-doing. "Her sufferings proceed from no misconduct, and can bring no disgrace.” He contrasts Marianne with Eliza. Marianne can “turn with gratitude towards her own condition, [emphasis added] when she compares it with that of my poor Eliza, when she considers the wretched and hopeless situation of this poor girl… surely this comparison must have its use with her. She will feel her own sufferings to be nothing." Is Austen hinting that Marianne "in an interesting condition," as people used to say? Is this one of Austen's dramatic moments when we, the reader, know the truth but we watch, as Brandon delusively thinks Marianne is pure as the driven snow?

Early April-- Marianne and Elinor travel with the Palmers to their country estate, which gets them partway home. Marianne plans to indulge in long walks, but her shoes and stockings get wet and she falls ill, as one does. Mrs. Palmer hurries her infant to safety away from the infection, and Mr. Palmer follows. Thus there are fewer witnesses to what is really happening; Marianne doesn’t have a bad post-viral infection: she is pregnant and possibly miscarrying.

Mid-April-- Marianne is very ill and Mrs. Jennings fears she will die. Colonel Brandon hurries to fetch Mrs. Dashwood, who hopes to get to Cleveland in time to see her “darling child,” so he is also away from Cleveland at the critical time of her illness.

Marianne either miscarries or has a premature child who is whisked away to a distant cottage.

End of April-- Marianne recovers and is well enough to travel home to Barton. She is chastened by her experience.

HeedlessMarianne – innocent or romantic?

HeedlessMarianne – innocent or romantic?Now, for my objections... When Marianne disappears for hours with Willoughby and then says she toured Allenham, Austen gives more emphasis to Marianne's rudeness than her lack of prudence: “it seemed very unlikely [to Elinor] that Willoughby should propose, or Marianne consent, to enter the house while Mrs. Smith was in it, with whom Marianne had not the smallest acquaintance.” Elinor scolds Marianne: “I would not go while Mrs. Smith was there.” Going “with no other companion than Mr. Willoughby,” is a secondary concern.

If I remember correctly, Professor Morrison suggested that Marianne did not really understand that premarital sex was wrong. I don’t think it would be possible for a girl Marianne’s age to not understand that sex outside of marriage (fornication) was wrong. Not just wrong. Very wrong. She couldn't have been brought up in the Anglican church and not know this very well, or not understood what society thought of fallen women. You couldn’t know about novels like Pamela and Clarissa or The Vicar of Wakefield without understanding that a girl was supposed chose death before dishonor, or she ought to die if she lost her virtue. Also, when Mrs. Jennings raises the issue of Brandon's 'natural daughter,' she lowers her voice and adds: "We will not say how near, for fear of shocking the young ladies.” It's understood that the young ladies are virtuous enough to be shocked,

Jane Shore, famous mistress to Edward IV, was publicly shamed Alternatively, Marianne, as a devoted Romantic, didn’t think extra-marital sex was wrong. After all, she believes that hiding her love for Willoughby was a stupid social convention: “a disgraceful subjection of reason to common-place and mistaken notions.” The “common-place and mistaken notion” referenced here is the idea that ladies absolutely should not show their preference for a man before he has paid his addresses to her. This pops up

again and again

in novels. Is Marianne defying foolish and mistaken conventions and having sex with Willoughby? Professor Morrison points to Marianne saying to Elinor: “if there had been any real impropriety in what I did, I should have been sensible of it at the time, for we always know when we are acting wrong, and with such a conviction I could have had no pleasure.”

Jane Shore, famous mistress to Edward IV, was publicly shamed Alternatively, Marianne, as a devoted Romantic, didn’t think extra-marital sex was wrong. After all, she believes that hiding her love for Willoughby was a stupid social convention: “a disgraceful subjection of reason to common-place and mistaken notions.” The “common-place and mistaken notion” referenced here is the idea that ladies absolutely should not show their preference for a man before he has paid his addresses to her. This pops up

again and again

in novels. Is Marianne defying foolish and mistaken conventions and having sex with Willoughby? Professor Morrison points to Marianne saying to Elinor: “if there had been any real impropriety in what I did, I should have been sensible of it at the time, for we always know when we are acting wrong, and with such a conviction I could have had no pleasure.” But fornication outside of marriage is much more than an “impropriety,” like chewing your food with your mouth open or something. It was regarded as a crime, and that's how Elinor refers to it elsewhere.

Fornication was less serious than adultery, but for centuries, girls and women and sometimes even men were publicly punished by the ecclesiastical courts in England and elsewhere. Up until about the 1770s in England, you could be publicly whipped in front of your community and congregation for fornication.

Check out this link and scroll down to “sexual offences.” The punishment had abated but the strong social stigma remained. And let's not forget that in other parts of the world, adultery and fornication are still punished as crimes today.

There were characters in novels of this era who argued that strictures on sex outside of marriage were ridiculous and antiquated, but these were the scurrilous villains and they made these arguments to seduce naïve girls, such as in The Farmer of Inglewood Forest. One free-thinking heroine, Adeline Mowbray, ultimately regretted her choices. It's hard to believe Marianne could wave away fornication as an "impropriety."

If Marianne was pregnant, this would have given her a strong claim to demand that Willoughby marry her. She could have turned to her only living male relative, John Dashwood, to insist that Willoughby do the honorable thing. Granted, John Dashwood wouldn't be as generous in Darcy was in bribing Wickham to marry Lydia, but possibly he would have paid out something to keep the scandal from disconcerting his wife and mother-in-law. But Marianne does not assert her claim. She is wild to return to her home and her mother, a course of action that would lead to the inevitable discovery of her condition and the complete disgrace of the family, and the ruin of Elinor and Margaret's marriage prospects. Marianne’s close call – the key passage

The narrator's description of Marianne's own thoughts undermines the theory that she went all the way with Willoughby. After Colonel Brandon hears that Willoughby has jilted Marianne for Miss Grey, he hurries round to Mrs. Jennings and reveals that his ward Eliza was seduced by Willoughby and has recently borne his child. Brandon held the story back when he thought Marianne was engaged; now that she is jilted, he hopes the revelation of Willoughby’s true character will help mend her broken heart. Elinor agrees, and she goes upstairs and tells Marianne the news. Marianne condemns Willoughby's seduction of Miss Williams, and not merely out of jealousy. She condemns the act. And here, I think is a key passage: “She felt the loss of Willoughby’s character yet more heavily than she had felt the loss of his heart; his seduction and desertion of Miss Williams, the misery of that poor girl,”

She feels that she had a close call herself: “and the doubt of what his designs might once have been on herself, preyed altogether so much on her spirits, that she could not bring herself to speak of what she felt even to Elinor.” [emphasis added] "his designs" clearly means, that Marianne is asking herself, did Willoughby have honorable intentions or was he just trying to seduce me?

Could Marianne have had a secret miscarriage?

Could Marianne have had a secret miscarriage?In my opinion, Austen gives an accurate description of a bad cold developing into a post-viral infection, but I won’t repeat it all here. As Marianne falls ill at Cleveland, she does not hide herself away. She insists on staying in the parlour until she is absolutely too ill to do so. She goes to bed only reluctantly, because she still hopes to be on the road to Barton and her mother soon.

The apothecary recognized that whatever was ailing Marianne, it was probably infectious. Marianne possibly has bacterial pneumonia or a strep infection which we don’t think of as fatal today, but they were, and still can be. There is also a forgotten infectious disease called Lemierre’s syndrome which afflicts young adults and which was often fatal before the advent of antibiotics. But many a character in an old novel fell deathly ill without a precise modern diagnosis.

Professor Morrison suggested that Mrs. Palmer's whisking her child away strengthened the supposition that Marianne was pregnant. The word “infant,” the focus on Mrs. Palmer’s child, was intended to bring children to our minds, along with Mrs. Dashwood’s thinking of Marianne, an almost adult, as "her darling child,” as she rushed to Cleveland. I don’t find this at all convincing. I think, given the miserably high infant mortality rates of the day, taking your baby away from a possible case of infectious disease would have been standard practise. And a mother's child is always her baby.

Marianne had round-the-clock attendants at her bedside while she was ill. If Marianne had a miscarriage during the height of her illness, it would be known to Elinor, the apothecary, Mrs. Jennings, Mrs. Jenning’s maid Betsy--who is an inveterate gossip, as is Mrs. Jennings--and perhaps other servants of the household. There is the bloody linen to consider, as well--how could it be hidden from the servants?What's the Point?

If Marianne had a secret pregnancy, what is the point? What is Austen saying? Fornication is okay if you don't get caught? The patriarchy is bad? (This, I think, is the meaning that Morrison ascribes to it, because he reacted very feelingly when he discussed the plight of all the real-life Eliza Williamses of the past).

Next post, why did Willoughby go to Cleveland?

Previous post: Three Scholarly Books

In Mansfield Park, Maria Bertram Rushworth runs off with Henry Crawford and lives with him for some unspecified period of time. There is no mention of any infant. In A Contrary Wind, my variation on Mansfield Park, things turn out differently. For more about my books,

click here.

In Mansfield Park, Maria Bertram Rushworth runs off with Henry Crawford and lives with him for some unspecified period of time. There is no mention of any infant. In A Contrary Wind, my variation on Mansfield Park, things turn out differently. For more about my books,

click here.

Published on May 08, 2023 00:00

April 27, 2023

CMP#141 Three Scholarly Books about Austen

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in.

Click here

for the first in the series.

CMP#141 Three Scholarly Books on Austen

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in.

Click here

for the first in the series.

CMP#141 Three Scholarly Books on Austen

For devoted Janeites, an interest in Jane Austen leads to an interest in learning more about her artistry and her life and times. If you are ready for some deep dives into Jane Austen, either for yourself or as a gift for a friend, there is an overwhelming number of titles to choose from. Even if you limited yourself to books with titles that start with "Jane Austen and..." you'd have enough reading to keep you busy for years. There's ....and Critical Theory, ....and the Enlightenment, ...and Literary Theory, ...and Philosophy, ...and Her Readers, ...and The State, ...and The State of the Nation, ...and Reflective Selfhood, ....and Leisure, ...and The Ethics of Life, ...and Altruism, ....and Her World, ...and Other Minds: Ordinary Language Philosophy, ...and The Reformation, ...and Performance, ...and Animals, ....and Her Art, ...and The Ethics of Description, ...and The Drama of Woman, ...and the English Landscape, ...and so on!

For devoted Janeites, an interest in Jane Austen leads to an interest in learning more about her artistry and her life and times. If you are ready for some deep dives into Jane Austen, either for yourself or as a gift for a friend, there is an overwhelming number of titles to choose from. Even if you limited yourself to books with titles that start with "Jane Austen and..." you'd have enough reading to keep you busy for years. There's ....and Critical Theory, ....and the Enlightenment, ...and Literary Theory, ...and Philosophy, ...and Her Readers, ...and The State, ...and The State of the Nation, ...and Reflective Selfhood, ....and Leisure, ...and The Ethics of Life, ...and Altruism, ....and Her World, ...and Other Minds: Ordinary Language Philosophy, ...and The Reformation, ...and Performance, ...and Animals, ....and Her Art, ...and The Ethics of Description, ...and The Drama of Woman, ...and the English Landscape, ...and so on! All of this reading would be pricey if you were buying the volumes, but if you are a university alumnus, you might check with them to see if you have access to their library. I've also bought a community library card from my local university. You can also speak to your local public librarian about getting inter-library loans. JASNA Canada has an online catalogue of books about Jane Austen and you can borrow from them if you are a member.

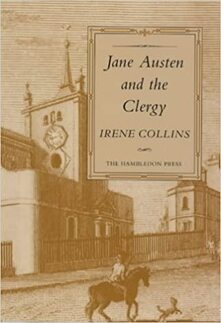

Here are three scholarly books that I've found worthwhile: Jane Austen and the Clergy (1994) by Irene Collins

The scope of Irene Collins's book is much broader than the role of the clergy in Austen's time. I bought it expecting to learn more about the nuts and bolts of a clergyman's life, and though I did learn some things, the author does not delve into explanations of the difference between a rector and a vicar, and she assumes her readers know what a chancel is. Most of the book is a social history of clergyman, with a chapter on clergyman's wives as well. This chapter on wives has much interesting detail from the lives of Austen's family and acquaintances. Mrs. Elton is mentioned in terms of the social duties of the clergyman's wife -- it's hard to picture her bestowing charity hither and thon.

The scope of Irene Collins's book is much broader than the role of the clergy in Austen's time. I bought it expecting to learn more about the nuts and bolts of a clergyman's life, and though I did learn some things, the author does not delve into explanations of the difference between a rector and a vicar, and she assumes her readers know what a chancel is. Most of the book is a social history of clergyman, with a chapter on clergyman's wives as well. This chapter on wives has much interesting detail from the lives of Austen's family and acquaintances. Mrs. Elton is mentioned in terms of the social duties of the clergyman's wife -- it's hard to picture her bestowing charity hither and thon.Collins also discusses the "restraint which Jane Austen felt in speaking and writing about religion" arising out of "austerity of Anglican worship at the time." The differences with evangelists were not just around doctrine, but around modes of worship. ( More on that restraint here ).

I found the last three chapters to be the most valuable. "Manners and Morals," "Morals and Society" and "Worship and Belief" contain reflections on Austen's novels and what they reveal about her personal morality and her world view. Collins canvasses the influential thinkers of the day such as Wilberforce, Burke and Locke, and the influence of the Evangelicals versus Church of England traditionalists.

Collins places Jane Austen on the side of the traditionalists. Austen's portrayals of feckless estate-owners like Sir Walter Elliot are not a veiled call for revolution, but an illustration of what happens when people don't live up to their responsibilities. Collins says: "Austen refused to regard the financial difficulties widespread among the gentry as due to anything but mismanagement: Colonel Brandon can soon put to rights the encumbered estate he inherited from his profligate brother and Sir Walter Elliot could have stayed at Kellynch if he had been prepared for modest retrenchment." Later, Collins notes that Austen gives credit where credit is due to merit regardless of birth: "she was by no means hostile to change. Admiral Croft turns out to be a better tenant for Kellynch Hall than Sir Walter Elliot of ancient lineage -- better for the grass, the sheep, the poor and the parish, as well as the house."

And for much more on the clergy, the church, and the role of religion in Austen's time, try also Brenda S. Cox's book , Fashionable Goodness (2022). Jane Austen and the French Revolution (1979) by Warren Roberts

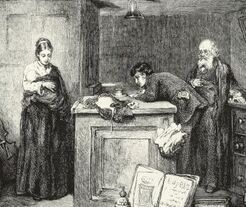

Illustration from "A Tale of Two Cities" by Dickens, Fred Barnard, 1870 This is a useful book for learning more about the historical setting of Austen's novels. Warren Roberts is an historian, not a literary critic, and he explains how the brief and fleeting references to current events in Austen's novels and private letters fit into the tide of history. He also speculates about how the dramatic events taking place around her shaped Austen's novels and her ideas. By "the French Revolution," Roberts means, more broadly, the effects of the French Revolution on English politics and society, the huge debate that opened up between conservatives who were alarmed by the French Revolution and progressives who cheered it on. On the evidence, he concludes that Austen was, broadly speaking, a Tory, a conservative. But he also points to where she shows feminist attitudes, if you think of feminism as being non-conservative.

Illustration from "A Tale of Two Cities" by Dickens, Fred Barnard, 1870 This is a useful book for learning more about the historical setting of Austen's novels. Warren Roberts is an historian, not a literary critic, and he explains how the brief and fleeting references to current events in Austen's novels and private letters fit into the tide of history. He also speculates about how the dramatic events taking place around her shaped Austen's novels and her ideas. By "the French Revolution," Roberts means, more broadly, the effects of the French Revolution on English politics and society, the huge debate that opened up between conservatives who were alarmed by the French Revolution and progressives who cheered it on. On the evidence, he concludes that Austen was, broadly speaking, a Tory, a conservative. But he also points to where she shows feminist attitudes, if you think of feminism as being non-conservative. As I have (ahem) frequently mentioned in this blog, I don't think Austen held radical views for her time. Isn't it interesting that scholars can sift and weigh the same evidence and come to completely opposite conclusions!

I think on the evidence, Roberts is right; Austen's a Tory in a Tory family and she's proud of her sailor brothers who served King and Country. She was not itching to send the aristocrats to the guillotine. But some issues, such as the abolition of slavery, crossed party lines, so a label can sometimes be limiting.

I think the most useful way to ask if Austen is making subtle and veiled allusions to the French Revolution (if this is really a question that exercises you) is to compare her books with the novels of her contemporaries who do bring politics more overtly into their novels. There are novelists who were much more outspoken, pro and con, about the French Revolution. For example, in Consequences or Adventures at Rraxal Castle (1796), young Lord Oswell comes back from a trip to France as a confirmed Republican. He addresses his noble father as "citizen." Oswell comes to a bad end. In this book, you don't have to read deep between the lines, as Roberts does with Austen. I think the question should be, "she was referencing the French Revolution compared to whom?"

John Sutherland, in Is Heathcliff a Murderer?: Great Puzzles in Nineteenth-Century Fiction, makes fun of Roberts. He says: "Roberts' line goes thus: "as is well known, Jane Austen never mentions the French Revolution. Therefore it must be a central preoccupation, and its silent pressure can be detected at almost every point in her narratives." Yes, it's all the more powerful for being completely unstated. T his is exactly what's going on today with "interrogating" Austen to unearth her views on slavery.

However, I agree that Roberts tends to read too much significance into little things. For example, when Henry Tilney scolds Catherine Morland for her gothic imagination, he says that the neighbourhood is full of voluntary spies. Roberts thinks that "spy" sentence jumps out of Henry Tilney's speech to Catherine. He thinks the reference to spies must make us think of government spies, and it must be quite a loaded word. Austen also uses the word in Mansfield Park. Mrs. Norris thought Susan was "a spy, and an intruder, and an indigent niece, and everything most odious." People used some words in contexts we wouldn't use today, including "plantation" (it meant, place that is planted), "slave" ("Your mother must have been quite a slave to your education") and "race" (Austen uses this word to describe the Morlands, instead of just "family."). So "plantation" and "race" don't have the same dark connotation for people in Austen's time that they do for us.

Roberts at least reads the "dead silence" passage in Mansfield Park correctly. Sir Thomas was not silent, it was his daughters. I think Roberts is solid in what he says about Mansfield Park. Similarly to Tony Tanner, he says the novel is about a traditional way of life that comes under threat because the people in charge of that traditional way of life (Sir Thomas and Lady Bertram) fail to guard it from dangerous interlopers (the Crawfords) who are alluring and attractive but dangerous and wrong. He also puts a charitable construction on whatever it was Sir Thomas was doing in Antigua, but it is all speculation in the end.

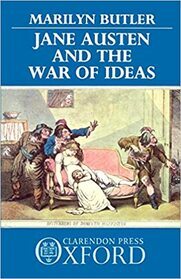

Jane Austen and the French Revolution is filled with useful historical information and cross-references to Austen's books and letters, and I think it's more accessible and readable for an introduction to the question of Austen's political views than Marilyn Butler's Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. I'd read this one first, then go on to Baker, if this topic is of interest to you. Jane Austen and the War of Ideas (1975) by Marilyn Butler

The depth and breadth of Marilyn Butler's knowledge of the long 18th century and the "War of ideas" between (broadly speaking) Jacobins and anti-Jacobins (pro and anti-French Revolution) is humbling. She shows how Austen's novels relate to the prevailing philosophical, moral and political debates of her time. She discusses dozens of other novels written during that period, and shows how novels were used to advocate for social reform, or to teach lessons about the perils of straying from conventional morality. Butler argues that of the two camps, Austen's novels "belong decisively to one class of partisan novels, the conservative..."

The depth and breadth of Marilyn Butler's knowledge of the long 18th century and the "War of ideas" between (broadly speaking) Jacobins and anti-Jacobins (pro and anti-French Revolution) is humbling. She shows how Austen's novels relate to the prevailing philosophical, moral and political debates of her time. She discusses dozens of other novels written during that period, and shows how novels were used to advocate for social reform, or to teach lessons about the perils of straying from conventional morality. Butler argues that of the two camps, Austen's novels "belong decisively to one class of partisan novels, the conservative..."Now that her rivals have dropped away into obscurity,* Austen and her work stands alone, and the modern reader does not have the benefit of understanding the milieu Austen grew up in, and the way her novels made a contribution to a national conversation. For example, many people wonder why it was such a big deal that young people would entertain themselves by putting on a play in a country house. Butler says of Lover's Vows, the play featured in Mansfield Park: "modern commentators sometimes underrate how notorious it was; how critics and satirists from the Anti-Jacobin (journal) had made it a byword for moral and social subversion."

Butler points out that Austen is not a revolutionary in terms of her ideas. She revolutionized the novel. "Her important innovations are technical and stylistic modifications within a clearly defined and accepted genre."

And while Austen's novels can be studied in the context of the "War of Ideas," they are also novels about people who go through crises and suffer and redeem themselves from their errors. The plots revolve around how Darcy overcomes his pride, Elizabeth overcomes her prejudice and Emma realizes she's been deluding herself and hurting other people.

I read this book in short doses with a highliter in my hand, and I think I'll refer back to it again and again to really absorb all the ideas and information presented.

*(Even the best known of them, like Burney and Radcliffe, have a small readership today compared to Austen). Previous post: A Spinster's Tale

Published on April 27, 2023 00:00

April 13, 2023

CMP#140 Caroline, the older heroine

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality.

Click here

for the first in the series. For more about other female writers of Austen's time, click the "Authoresses" tag in the Categories list to the right. CMP#140 The Spinster's Tale (1801), another never-reviewed book

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. The opinions are mine, but I don't claim originality.

Click here

for the first in the series. For more about other female writers of Austen's time, click the "Authoresses" tag in the Categories list to the right. CMP#140 The Spinster's Tale (1801), another never-reviewed book

Carriage accidents and abductions Ann WIngrove's The Spinster’s Tale (1801) caught my eye because of the title. It received no reviews when it was published, so here is another of

my better-late-than-never

book reviews.

Carriage accidents and abductions Ann WIngrove's The Spinster’s Tale (1801) caught my eye because of the title. It received no reviews when it was published, so here is another of

my better-late-than-never

book reviews. The Spinster’s Tale is jam-packed with numerous plot-lines, backstories, and weddings. Plus a separate short gothic novel is stuck in the middle. There are so many characters, it’s difficult to remember them all.

Have you seen people in social media point out that Regency romances are unrealistic because there weren’t that many eligible young dukes and earls in Regency England? Well, that was the case from the get-go; the novels written at the time featured handsome, eligible lords by the bushel. There are half-a-dozen titled men running around in this novel, all of them in want of a wife, and they all marry girls of humbler birth.

One thing that sets this novel apart is that two of the major protagonists, and one minor, are older ladies. The titular spinster, Mrs. Caroline Herbert, ("Mrs." denotes an older lady, not necessarily a married one) is approaching 50. The kind and charitable Dowager Lady Brumpton has a fun back story where she dresses herself in boy’s clothes and climbs out a window after she’s abducted by a libertine. The minor character Miss Woodley is the impoverished authoress of the novel-within-a-novel Langbridge Fort. “Romance is not my forte,” she tells one of the young heroines, “but I had been told nothing would sell now, but the horrible, the wonderful, and the improbable.”

In addition to centering older females, The Spinster's Tale has other features which might be of interest to academics...

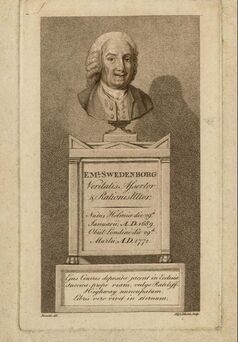

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), Courtesy British Museum Topics and themes in The Spinster's TaleThe author promotes the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish scientist turned Christian mystic, who still has a following today. One of her characters can talk to angels, but her relatives throw her in an insane asylum.Two of the female characters wear men’s clothes for plot reasons, and so does one of the characters in the novel-within-a-novel. If you are interested in cross-dressing women in the long 18th century, this is your book.The admirable characters are always generous and thoughtful to the poor and they delight in useful schemes to improve life for working people. (Examples at the bottom of this post). For a Swedenborgian, works are important in addition to faith.Class is not much of a barrier for the various couples, nor are tyrannical parents. The men choose their wives for their sterling characters, beauty, and modesty. On the other hand, right after Fanny Mordaunt, orphaned daughter of a clergyman, accepts Lord Brumpton's proposal, she becomes her wealthy uncle's heiress, so equilibrium is preserved. There's also the story of a girl who elopes without parental consent and her husband turns out to be a rake and a gambler.Just about everybody finds love in this novel, including the spinster. A few characters die because of the sinful lives they’ve led, but others reform themselves and return to the paths of righteousness. The worst fates are reserved for people who are addicted to gaming and card-playing. “Mrs. Spencer was buried yesterday… this melancholy event has cast a temporary gloom over our social parties; but we shall soon forget her, whose irrational life made it impossible for any one to regret her loss.” Augusta becomes a courtesan and even though her titled lover marries her in the end, she still dies of venereal disease: "the consequence of her horrid connection with the debauched [manservant named] Duval which she thoughtlessly neglected, till it arrived to a most alarming state.” As for empire and colonialism, three times the author resorts to a West Indian fortune to enrich the characters when

money is needed

for plot purposes: “your kind heart will rejoice in hearing our son William is in health and settled in great business with a rich partner in Jamaica, and likely to make a fortune.” There is no mention of the contradiction between preaching morality and benevolence on the one hand, and enriching oneself through slavery. Inheriting a West Indian fortune is like winning the lottery.

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), Courtesy British Museum Topics and themes in The Spinster's TaleThe author promotes the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish scientist turned Christian mystic, who still has a following today. One of her characters can talk to angels, but her relatives throw her in an insane asylum.Two of the female characters wear men’s clothes for plot reasons, and so does one of the characters in the novel-within-a-novel. If you are interested in cross-dressing women in the long 18th century, this is your book.The admirable characters are always generous and thoughtful to the poor and they delight in useful schemes to improve life for working people. (Examples at the bottom of this post). For a Swedenborgian, works are important in addition to faith.Class is not much of a barrier for the various couples, nor are tyrannical parents. The men choose their wives for their sterling characters, beauty, and modesty. On the other hand, right after Fanny Mordaunt, orphaned daughter of a clergyman, accepts Lord Brumpton's proposal, she becomes her wealthy uncle's heiress, so equilibrium is preserved. There's also the story of a girl who elopes without parental consent and her husband turns out to be a rake and a gambler.Just about everybody finds love in this novel, including the spinster. A few characters die because of the sinful lives they’ve led, but others reform themselves and return to the paths of righteousness. The worst fates are reserved for people who are addicted to gaming and card-playing. “Mrs. Spencer was buried yesterday… this melancholy event has cast a temporary gloom over our social parties; but we shall soon forget her, whose irrational life made it impossible for any one to regret her loss.” Augusta becomes a courtesan and even though her titled lover marries her in the end, she still dies of venereal disease: "the consequence of her horrid connection with the debauched [manservant named] Duval which she thoughtlessly neglected, till it arrived to a most alarming state.” As for empire and colonialism, three times the author resorts to a West Indian fortune to enrich the characters when

money is needed

for plot purposes: “your kind heart will rejoice in hearing our son William is in health and settled in great business with a rich partner in Jamaica, and likely to make a fortune.” There is no mention of the contradiction between preaching morality and benevolence on the one hand, and enriching oneself through slavery. Inheriting a West Indian fortune is like winning the lottery.

Union Street, Bath Literary aspectsThe pace is swift. If Austen's favorite author, Samuel Richardson, was notoriously prolix, this author barely sketches out the plots of her novels. The narrative parts of the story read like they were written by a teenager: "Lady Brumpton... had long wished for a friend of her own age, with whom she might converse or correspond without any reserve.” She finds this friend in Mrs. Herbert: “'in short your appearance and manner proclaimed the gentlewoman, and I loved you as a sister the instant I found myself seated by your side. Your sentiments are so congenial to my own, that I feel for you the most perfect esteem…'”Just like the novel Melinda Harley the brisk action is interspersed with sermonettes, and characters often philosophize in their letters to each other. “I would have all young people marry, when they can do it properly; that is where there is a mutual affection, and a fortune on either or both sides united; to live as they have been brought up for I never knew a marriage happy (for any length of time) where a sufficiency was wanting, to support the couple in that style their birth and education required.”Coincidences abound. Whether a character is walking along the beach or in a garden in Portugal, or noticing a carriage with the family arms turning into an inn-yard, they're bound to run into some long-lost relation or be reunited with a lost love.Some plot points might sound familiar: Fanny Mordaunt's friend Harriet loves coquetting around Bath: “As to the Duke [of Mitcham], her vanity had represented his behavior in so flattering a manner, that she expected every day when he would offer to marry her; but till she was certain he was seriously attached to her, she did not like to give up so consequential a lover as Mr. Grant, or the tender attentions of the elegant Major Blandford.”Every now and then the author inflicts her poetry on us.The novel-within-a-novel Langbridge Fort is laugh-out-loud bad. I'm half-convinced it is a parody. I might share some excerpts sometime.The author wraps up the main love stories early in Volume III. The narrator remarks: “As many of my friends have remarked to me, how greatly they were disappointed to have a well-wrote novel or tale, end with the wedding-day of the principal hero or heroine of the piece—I shall beg leave in this my humble attempt to amuse and instruct, to vary from the general mode of my sister authors, by continuing mine for some time longer…” So, we skip ahead to the next generation; the daughter of Lord Brumpton and his wife Fanny. The Duke of Mitcham was in love with Fanny, so he waits 18 years and marries her daughter (for anyone looking examples of Marianne-Colonel Brandon-type pairings.) The story closes with the death of the dowager Lady Brumpton, at the age of 69.

Union Street, Bath Literary aspectsThe pace is swift. If Austen's favorite author, Samuel Richardson, was notoriously prolix, this author barely sketches out the plots of her novels. The narrative parts of the story read like they were written by a teenager: "Lady Brumpton... had long wished for a friend of her own age, with whom she might converse or correspond without any reserve.” She finds this friend in Mrs. Herbert: “'in short your appearance and manner proclaimed the gentlewoman, and I loved you as a sister the instant I found myself seated by your side. Your sentiments are so congenial to my own, that I feel for you the most perfect esteem…'”Just like the novel Melinda Harley the brisk action is interspersed with sermonettes, and characters often philosophize in their letters to each other. “I would have all young people marry, when they can do it properly; that is where there is a mutual affection, and a fortune on either or both sides united; to live as they have been brought up for I never knew a marriage happy (for any length of time) where a sufficiency was wanting, to support the couple in that style their birth and education required.”Coincidences abound. Whether a character is walking along the beach or in a garden in Portugal, or noticing a carriage with the family arms turning into an inn-yard, they're bound to run into some long-lost relation or be reunited with a lost love.Some plot points might sound familiar: Fanny Mordaunt's friend Harriet loves coquetting around Bath: “As to the Duke [of Mitcham], her vanity had represented his behavior in so flattering a manner, that she expected every day when he would offer to marry her; but till she was certain he was seriously attached to her, she did not like to give up so consequential a lover as Mr. Grant, or the tender attentions of the elegant Major Blandford.”Every now and then the author inflicts her poetry on us.The novel-within-a-novel Langbridge Fort is laugh-out-loud bad. I'm half-convinced it is a parody. I might share some excerpts sometime.The author wraps up the main love stories early in Volume III. The narrator remarks: “As many of my friends have remarked to me, how greatly they were disappointed to have a well-wrote novel or tale, end with the wedding-day of the principal hero or heroine of the piece—I shall beg leave in this my humble attempt to amuse and instruct, to vary from the general mode of my sister authors, by continuing mine for some time longer…” So, we skip ahead to the next generation; the daughter of Lord Brumpton and his wife Fanny. The Duke of Mitcham was in love with Fanny, so he waits 18 years and marries her daughter (for anyone looking examples of Marianne-Colonel Brandon-type pairings.) The story closes with the death of the dowager Lady Brumpton, at the age of 69.

Frederica, Duchess of York (1767-1830), known for having very small feet

Noblesse Oblige

Frederica, Duchess of York (1767-1830), known for having very small feet

Noblesse Oblige

The Spinster’s Tale is dedicated by permission to Frederica, the Duchess of York. Like our modern-day Duchess of York, Frederica didn’t fit into the royal scene, had a reputation for being eccentric, and she separated from her husband. She was an animal lover and was known for being Lady Bountiful to the peasantry around her private estate, Oatlands. A recurring theme in The Spinster’s Tale is noblesse oblige; the privileged class have a duty to be good stewards of their their estates, and to take good care of the peasantry. Ann Wingrove has specific ideas about this which she shares in her novel: The Duke of Mitcham is generous to his honest steward, Mr. Wilmot, who, “with the entire approbation of his noble patron, built sixteen neat cottages, which was to be the habitation of female servants in the decline of life" but there was this interesting proviso, the servants had to "bring a certain assurance they had, during any part of their lives, lived six years in one place…”

Ann Wingrove was definitely of the "teach a man to fish" school of charity. “Two thousand pounds a year, was lent out to young industrious tradesmen, at three per cent, the interest of which was paid to six men, whose incomes would not enable them to live as their infirmities and advanced age required. Schools were opened for the poor of both sexes, where they were instructed in reading and writing, a few hours every day; and the other part passed in employments that would render them good labourers, servants, or mechanics, according as their strength or ability would permit.”

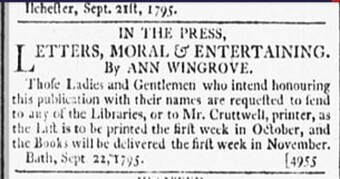

Bath Chronicle & Gazette, Sept. 24, 1795 About the authoress

Bath Chronicle & Gazette, Sept. 24, 1795 About the authoressAnn Wingrove (1745?-1824?) lived in Bath. She has one other attributed work, Letters, Moral & Entertaining (1795). This is a collection of conventional moral lessons for young people. Her "Letter to Delia" on the dangers of reading novels has been noticed by academics. The reviewers praised Letters for its “moral and religious tendencies," but they weren't struck by her writing talents. Two reviews mentioned she should stick to prose and stay away from inserting her poetry. “Mediocrity of talent, and strict purity of design [i.e. motive]…. are yet, in a certain species of composition, abundantly serviceable to the morals of mankind.”

The publication of Letters was funded by subscription, the 18th century equivalent of crowdfunding. Wingrove had over 300 subscribers for Letters, Moral & Entertaining, some of whom ordered multiple copies, a truly impressive accomplishment for a debut effort that was unremarkable both for its subject-matter and its literary merit.

How did an unknown 50-year-old woman garner so much support for her first book? If I have the correct Ann Wingrove, she was the daughter of Benjamin Wingrove, a prosperous Bath baker, maltser and brewer who was part of an extended family of Wingroves engaged in the same trades. They must have been prosperous enough to send their daughters to school and to attain to some gentility. It is possible that Ann and her sister ran their own academy because a "Miss A. Wingrove" taught pianoforte, the harp, singing, and dancing in the 1790’s in Bath. I like to think she was a cross-dressing eccentric who wore breeches to take the male part for her female customers, since she definitely had a thing about cross-dressing. At any rate, she must have met many people who spent time in Bath and wanted lessons for their daughters. Perhaps, too, she made connections through the Swedenborgian community in the United Kingdom. Their small congregations springing up around the country were probably exchanging letters at this time, even before they had established a Swedenborgian journal.

Communal grave marker, photo courtesy Haycombe cemetery. The reason I think I’ve found the correct birth and death dates for Ann Wingrove is that the list of subscribers in Letters, Moral & Entertaining includes some names which also appear in the will of Ann Wingrove of Bath, probated in 1824. Ann left some of her friends “five pounds for a ring” or ten pounds, or more: Mrs. Gregg, Mrs. Bingley, Mrs. Reynolds, Mrs. Wood, Mrs. Tugwell, and Mr. and Mrs. Thomas King of Walcot-House.

Communal grave marker, photo courtesy Haycombe cemetery. The reason I think I’ve found the correct birth and death dates for Ann Wingrove is that the list of subscribers in Letters, Moral & Entertaining includes some names which also appear in the will of Ann Wingrove of Bath, probated in 1824. Ann left some of her friends “five pounds for a ring” or ten pounds, or more: Mrs. Gregg, Mrs. Bingley, Mrs. Reynolds, Mrs. Wood, Mrs. Tugwell, and Mr. and Mrs. Thomas King of Walcot-House.Ann Wingrove's obituary, such as it was, only states that she died in her eightieth year. She might have outlived the people who knew about her books, and the editors of the Bath Chronicle, which posted the obituary, might not have known that 30 years before, her dancing academy was in the same building as their office at 9 Union Street.

Ann Wingrove was buried at St. Michael's burial ground but that cemetery was closed in 1967 and the remains were excavated and re-buried at Haycombe Cemetery.

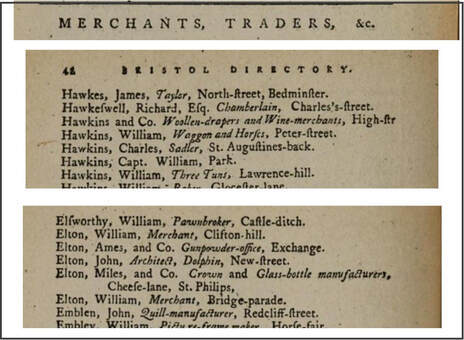

The Spinster’s Tale was available at a circulating library on Milsom-Street, so it’s possible Jane Austen had a laugh over Langbridge Fort while she lived in Bath. She could also have opened Letters, Moral & Entertaining and picked out character names at random from Wingrove’s list of subscribers because Badeley, Bingley, Bennet, Coles, D’Arcy, Elton, Fitzwilliam, Ferrers, Ford, Smith, Ward, Watson, Hawkins, Jennings, and Palmer appear there.

Previous post: The Vicar of Wrexhill wrecks everything In the final book of my Mansfield Trilogy, my character William Gibson entertains little Betsy Price with a tale about a shipwrecked traveler and a Polynesian princess, told in the overblown style of a sentimental novel. For more about my novels, click here.

Published on April 13, 2023 00:00

April 6, 2023

CMP#139 Book Review: The Vicar of Wrexhill

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who think we should speak of the past only to condemn it, but still want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history, have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. She wasn't a radical. Click here for the introduction to this blog. CMP#139: Frances Trollope's The Vicar of Wrexhill (1837)

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times she lived in. Those who think we should speak of the past only to condemn it, but still want to rescue Jane Austen from the dustbin of history, have a bit of a dilemma on their hands. She wasn't a radical. Click here for the introduction to this blog. CMP#139: Frances Trollope's The Vicar of Wrexhill (1837)

Frances Trollope (1779-1863) After wrapping up

my blog series

about unflattering portraits of Methodist ministers in 18th century novels, I came across The Vicar of Wrexhill by Frances Trollope. This 1832 novel is a bit outside the date range of novels I study, and the titular vicar is not a Methodist, but an evangelical in the Church of England. However, like the ministers in 18th-century novels, the evangelicals in this story are ranting fanatics or hypocrites and their followers are deluded fools.

Frances Trollope (1779-1863) After wrapping up

my blog series

about unflattering portraits of Methodist ministers in 18th century novels, I came across The Vicar of Wrexhill by Frances Trollope. This 1832 novel is a bit outside the date range of novels I study, and the titular vicar is not a Methodist, but an evangelical in the Church of England. However, like the ministers in 18th-century novels, the evangelicals in this story are ranting fanatics or hypocrites and their followers are deluded fools.Many people might pass over The Vicar of Wrexhill because its once-controversial subject matter--"High church" Anglicanism versus evangelism--would be of little interest in a post-Christian age. However, the story still offers snarky humour, heroines in peril, a cantankerous old married couple, and romance. The dialogue is sometimes stilted--it's hard to believe that 17-year-old girls actually speak with such complex sentences, but then I feel that way about Marianne Dashwood as well.

I liked the way Mrs. Trollope--like Jane Austen in Mansfield Park--designed her characters to come into conflict because of their differing personalities and world views. But for me, the biggest payoff was realizing I was reading about a 19th century moral panic, with so many parallels to the debates preoccupying society in our own times, specifically in the way people behaved--intimidating one another, condemning one another, freezing people out. Buckle up for a slow-motion train wreck in which you're not sure whether the characters are heading for ultimate tragedy or a happy ending... The Premise

Mr. Cartwright, the newly-appointed vicar for the lovely little parish of Wrexhill, is a handsome widower with two adult children. He devotes much of his time to making pastoral calls at the homes of attractive widows and praying with them in his flamboyant, emotional, style. He quickly fastens on the newly-bereaved Clara Mowbray, who has full command of her husband’s considerable fortune. (No doubt Mr. Mowbray was planning to revise his will once his son Charles came of age but dad drops dead the night after Charles’s 21st birthday.) Charles has two sisters, the angelic Helen and the poetry-loving Fanny. As well, the Mowbrays are guardians to Rosalind Torrington, a high-spirited Irish heiress who serves the role of saucy sidekick. She's the most engaging character in this novel.

Into this grieving family comes Rev. Cartwright, oozing sincerity and piety. Long before the terms were invented, Mrs. Trollope created a portrait of a narcissistic sociopath. The vicar flatters and fawns on 15-year-old Fanny, and she falls completely under his spell. Rosalind and Helen, on the other hand, are immediately repulsed by his manipulative tactics.

The first volume slowly and deliberately sets out the confluence of circumstances which puts the vicar in control of the Mowbray family.

The creepy vicar gets 15-year-old Fanny alone: Mrs. Mowbray's neighbor, the baronet, opines: “Of every family into which this insidious and most anti-christian schism has crept... in nine instances out of ten, it has been the young girls who have been selected as the first objects of conversion, and then made the active means of spreading it afterwards.” The Widow Mowbray is weak and susceptible. The crusty old baronet-next-door refuses to help her negotiate her financial affairs, leaving the field clear for the vicar. Helen, as a

"picture of perfection" heroine,

can do little else but weep. Helen can’t bring herself to say she hates the vicar, but Rosalind certainly can and she engages in some spirited verbal duels with him. At the end of one quarrel, the minister asks to shake her hand. She declines: "But you must excuse my not accepting your proffered hand. It is but an idle and unmeaning ceremony perhaps, as things go; but the manner in which you now stretch forth your hand gives a sort of importance to it which would make it a species of falsehood in me to accept it. When it means any thing, it means cordial liking; and this, sir, I do not feel for you."

The creepy vicar gets 15-year-old Fanny alone: Mrs. Mowbray's neighbor, the baronet, opines: “Of every family into which this insidious and most anti-christian schism has crept... in nine instances out of ten, it has been the young girls who have been selected as the first objects of conversion, and then made the active means of spreading it afterwards.” The Widow Mowbray is weak and susceptible. The crusty old baronet-next-door refuses to help her negotiate her financial affairs, leaving the field clear for the vicar. Helen, as a

"picture of perfection" heroine,

can do little else but weep. Helen can’t bring herself to say she hates the vicar, but Rosalind certainly can and she engages in some spirited verbal duels with him. At the end of one quarrel, the minister asks to shake her hand. She declines: "But you must excuse my not accepting your proffered hand. It is but an idle and unmeaning ceremony perhaps, as things go; but the manner in which you now stretch forth your hand gives a sort of importance to it which would make it a species of falsehood in me to accept it. When it means any thing, it means cordial liking; and this, sir, I do not feel for you." Rosalind tries to warn Charles Mowbray, the son, but he is an optimist, rather like Edmund Bertram in Mansfield Park. He doesn’t see the danger until it is too late. And anyway, filial duty prevents both Charles and Helen from overruling their mother's bad decisions. One contemporary reviewer complained that another character, the vicar’s daughter Henrietta, could have spoken up and exposed her father as a fraud and a hypocrite, but instead she just drops gloomy hints: “[K]eep Mr. Cartwright as far distant from all you love as you can. Mistrust him yourself, and teach all others to mistrust him.—And now, never attempt to renew this conversation.” Awakening his flock

Mr. Cartwright claims to be one of the “elect,” guaranteed a place in heaven. "Every object, animate or inanimate, furnished him a theme; and let him begin from what point he would, (unless in the presence of noble or influential personages to whom he believed it would be distasteful,) he never failed to bring the conversation round to the subject of regeneration and grace, the blessed hopes of himself and his sect, and the assured damnation of all the rest of the world." His words fall on willing ears; one female acolyte declares: "'My life has been passed in a manner so widely different from what I am sure it will be in future, that I feel as if I were awakened to a new existence!"

The vicar replies, "'The great object of my hopes is, and will ever be, to lead my beloved flock to sweet and safe pastures.—And for you,' he added, in a voice so low, that she rather felt than heard his words, 'what is there I would not do?'"

When anyone challenges him, he plays the damnation card on them: "May your unthinking youth, my dear young lady," [he says to Rosalind], "plead before the God of mercy in mitigation of the wrath which such sentiments are calculated to draw down!" Pretty soon, the entire village is divided between those who are "regenerated," (ie "born again") and those who are not. The vicar rewards his followers and punishes the holdouts. The schoolmaster of Wrexhill is “cancelled,” you might say, because he refuses to bring his pupils to Mr. Cartwright’s evening prayer meetings. His objection is not so much doctrinal but that young people and servants can't be entrusted to attend ecstatic evening gatherings which can lead to unbridled passion and rumpty-tumpty in the bushes. {This puts me in mind of what my mother recalls about travelling gospel tent shows in Southern Illinois in her girlhood]. Anyway, the schoolmaster is ruined and ends up in debtor’s prison.

Sweet-tempered Mrs. Richards is condemned and lectured by her daughters: “She is breaking her heart because... her daughters have thought proper to... tell her very coolly, upon all occasions, that she is doomed to everlasting perdition, and that their only chance of escape is never more to give obedience or even attention to any word she can utter."

No-one seems to notice that the vicar has failed to convert his own children. His sarcastic son James escapes to become an actor, while Henrietta, repulsed by his version of Christianity, becomes an atheist--a revelation intended to shock the reader.

There are some dryly comic passages, as when the ladies organize a fund-raising fair for a mission to Africa. One contemporary reviewer compared Mrs. Trollope to Austen in her “slyness and discrimination” in portraying human foibles.

The Vicar triumphantly changes the name of the estate from "Mowbray Hall to "Cartwright Hall" and receives visitors Spoiler time

The Vicar triumphantly changes the name of the estate from "Mowbray Hall to "Cartwright Hall" and receives visitors Spoiler timeThings go from bad to worse for the siblings Charles, Helen and Fanny when Mrs. Mowbray marries the vicar. She tells her family and her servants: “his commands must on all occasions supersede those of every other person. I trust you will all show yourselves sensible of the inestimable blessing I have bestowed upon you in thus giving you a master who can lead you unto everlasting life.” A horrified Fanny realizes that the man she idolized was using her, but she's still terrified of spending eternity in a lake of fire. She sinks into near-madness.

Mrs. Mowbray, now Mrs. Cartwright, is soon pregnant with Rev. Cartwright's child, so the prospects for the Mowbray siblings ever seeing a penny of their inheritance are looking slim. The minister clamps down on his control of the entire household. Colonel Harrington, the son of the crusty old baronet-next-door, sends a marriage proposal to Helen by mail, but Mr. Cartwright burns the letter before she sees it. He intends to force Helen to marry his repulsive cousin Stephen Corbold. The dramatic high point of the novel comes when the two men connive to get Helen alone with Mr. Corbold. The implication is that he will compromise her by sexually assaulting her, and then she will have to marry him. I will say that Helen, the insipid heroine, really redeems herself in this scene. I thought Mrs. Trollope would bring her sweetheart to her rescue in the nick of time, but Helen rescues herself. Instead of fainting, she throws a bottle of “spirits of hartshorn” (aka ammonia) into the creep’s face and makes her escape.

Meanwhile, Rosalind devotes herself to reclaiming Henrietta from atheism as she sinks into the grave. The whole story appears to be heading toward complete tragedy but thanks to some dying revelations from Henrietta, her dad is exposed as a philanderer. It seems one of his parishioners left town to go visit her aunt (as folks used to say), because her religious raptures with the vicar led to something more physical. When Mrs. Cartwright learns about her husband’s love child, the spell he held over her is broken. But, by the logic of the 19th century novel, this doesn’t mean that the vicar must die, it means Mrs. Cartwright and her innocent infant child must die, and they do. At the reading of the will, we learn that although Mrs. Cartwright was virtually kept a prisoner by the vicar, she managed to secretly change her will to reinstate her three children. Happy Ending

Fanny recovers from her obsession with death and salvation and regains her mental equilibrium, Charles, no longer penniless, is free to propose to Rosalind, while Helen marries Colonel Harrington. The vicar leaves town with his still-loyal followers and the remaining villagers resume their old lives. "[T]he pretty village of Wrexhill once more became happy and gay, and the memory of their serious epidemic rendered its inhabitants the most orderly, peaceable, and orthodox population in the whole country.”

Even if you are not conversant with, or could care less about, the battling doctrines of "faith" versus "works" in The Vicar of Wrexhill, you might be interested in Mrs. Trollope's portrayal of a power-hungry person who exploits an uncompromising dogma which splits families and friends apart. This phenomenon, I do believe, is entirely relatable to modern times.

Satiric 1832 American cartoon of Frances Trollope with her family in Cincinnati (detail) About the Authoress

Satiric 1832 American cartoon of Frances Trollope with her family in Cincinnati (detail) About the AuthoressFrances Trollope (1779-1863) is the mother of the better-known novelist Anthony Trollope. Space prevents me from recapping her full biography in this post, but she had an interesting and difficult life and published 40 books in her twenty-year career. As the Victorian Web explains: "Although born in 1779, just four years after Jane Austen, she started writing long after Austen's death, when she was over fifty. Published during the Victorian era, her novels mix an eighteenth century sensibility with a reforming zeal common to the nineteenth century. Her work varies greatly in subject matter, genre, and merit; she quickly published novels that could have benefited from extensive editing."

Frances Trollope's first book was a caustic commentary on America which sold well but of course angered Americans. When she turned her scrutiny to the evangelical movement in England she roused considerable ire at home. An anonymous reviewer for Fraser’s magazine said Mrs. Trollope: “had much better have remained home, pudding-making or stocking-mending, than have meddled with matters which she understands so ill.” (Fuller quote below)

When The Vicar of Wrexhill was published, it was thought that the character of the vicar was based on a real evangelical minister, John William Cunningham, whom Frances Trollope knew and disliked. I think she is not lampooning one man but an entire religious movement. But ewwww, just suppose Rev. Cunningham really spoke to the teenage girls in his parish the way that Rev. Cartwright speaks to Fanny in the novel! "How sweetly does youth, when blessed with such a cheek and eye as yours, Miss Fanny, accord with the fresh morning of such a day as this!—I feel," [Rev. Cartwright] added taking her hand and looking in her blushing face, "that my soul never offers adoration more worthy of my Maker than when inspired by intercourse with such a being as you!"

"Oh! Mr. Cartwright!" cried Fanny, avoiding his glance by fixing her beautiful eyes upon the ground.

"My dearest child! fear not to look at me—fear not to meet the eye of a friend, who would watch over you, Fanny, as the minister of Heaven should watch over that which is best and fairest, to make and keep it holy. Let me have that innocent heart in my keeping, my dearest child, and all that is idle, light, and vain shall be banished thence, while heavenward thoughts and holy musings shall take its place. Have you essayed to hymn the praises of your God, Fanny, since we parted yesterday?" One of Mrs. Trollope's friends, Henrietta Skerrett, had a miserable experience with evangelism, though I don't know the details. But surely this is why the vicar's daughter in the book was named Henrietta.

Mrs. Trollope also wrote a pro-abolition novel and a novel exposing the harsh life of children who worked in factories. In other words she was much more outspoken than Jane Austen. Fraser's Magazine, January 1838

"With a keen eye, a very sharp tongue, a firm belief, doubtless, in the high church doctrines, and a decent reputation from the authorship of half-a-dozen novels, or other light works, Mrs. Trollope determined on no less an undertaking than to be the champion of oppressed Orthodoxy. These are feeble arms for one who would engage in such a contest, but our fair Mrs. Trollope trusted entirely in her own skill, and the weapon with which she proposed to combat a strong party is no more nor less than this novel of The Vicar of Wrexhill. It is a great pity that the heroine ever set forth on such a foolish errand; she has only harmed herself and her cause (as a bad advocate always will), and had much better have remained home, pudding-making or stocking-mending, than have meddled with matters which she understands so ill.

"There can be little doubt as to the cleverness of this novel, but, coming from a women's pen, it is most odiously and disgustingly indecent. As a party attack [on the Whigs], it is an entire failure; and as a representation of a very large portion of English Christians, a shameful and wicked slander."

Previous post: Guest post: Jane Austen, anti-capitalist

In the second novel of my Mansfield Trilogy, an unctuous clergyman, the Reverend Edifice, becomes interested in Fanny Price, especially because he thinks she will receive a handsome bequest when her friend Mrs. Butters dies. My story also features Lord and Lady Delingpole, an older couple who quarrel a lot but ultimately feel a lot of respect for each other, rather like the baronet and his wife in Trollope's story. For more about my books, click here.

In the second novel of my Mansfield Trilogy, an unctuous clergyman, the Reverend Edifice, becomes interested in Fanny Price, especially because he thinks she will receive a handsome bequest when her friend Mrs. Butters dies. My story also features Lord and Lady Delingpole, an older couple who quarrel a lot but ultimately feel a lot of respect for each other, rather like the baronet and his wife in Trollope's story. For more about my books, click here.

Published on April 06, 2023 00:00

March 31, 2023

CMP#138 Guest Post: Jane Austen, Anti-Capitalist

It's always a pleasure to encourage young scholars, so I'm pleased to welcome Lura Amandan to "Clutching My Pearls" this week. Ms. Amandan is a postgraduate student at the University of Reinlegen in Germany. Her doctoral thesis is focused on early critiques of capitalism in European literature, and with the kind permission of her faculty advisors, I am sharing an excerpt from her truly groundbreaking work-in-progress concerning Jane Austen and capitalism. My six questions for Austen scholars post is here. Jane Austen, "A Marxist Before Marx"

It's always a pleasure to encourage young scholars, so I'm pleased to welcome Lura Amandan to "Clutching My Pearls" this week. Ms. Amandan is a postgraduate student at the University of Reinlegen in Germany. Her doctoral thesis is focused on early critiques of capitalism in European literature, and with the kind permission of her faculty advisors, I am sharing an excerpt from her truly groundbreaking work-in-progress concerning Jane Austen and capitalism. My six questions for Austen scholars post is here. Jane Austen, "A Marxist Before Marx"

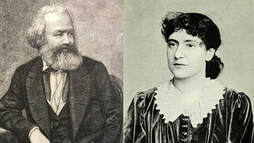

Karl Marx and his daughter Eleanor: was her name inspired by Austen? (Source: British Library) As many scholars of Austen have long pointed out, Jane Austen intended to use Sanditon to explore the social and moral consequences of capitalism. Sadly, Austen laid the manuscript aside during her final illness. Interrogating Austen through a critical lens reveals that she was a committed anti-capitalist who was determined to fight back in the only way she could--through her pen.

Karl Marx and his daughter Eleanor: was her name inspired by Austen? (Source: British Library) As many scholars of Austen have long pointed out, Jane Austen intended to use Sanditon to explore the social and moral consequences of capitalism. Sadly, Austen laid the manuscript aside during her final illness. Interrogating Austen through a critical lens reveals that she was a committed anti-capitalist who was determined to fight back in the only way she could--through her pen.I am not referring to Austen's well-known portrayals of the landed gentry and the lesser nobility, but rather, her subtle attacks on the pernicious influence of consumerism. To a startling extent, the buying and selling of things and the rise of the urban bourgeoisie forms a backdrop to her so-called marriage plot novels. Scholar David Daiches called Austen "a Marxist before Marx."

It is no exaggeration to say that Austen shows us whether a character is good or bad by their reaction to consumerism. Two of Austen’s heroines never step inside a store--Elizabeth Bennet and Fanny Price. And, significantly, the heroines who do go shopping always live to regret the experience. It is only the fops and fools who like to shop, as we will see. Austen’s message could not be clearer: Capitalism is the root of all evil. Let’s critically take the novels one by one...

CE Brock illustration, Lydia and her bonnet In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings invites Elinor and Marianne Dashwood to go shopping with her after they reach London. Marianne, perhaps the most highly principled character in all of Austen, refuses to go at first. Whenever she is in a store, she is “restless and dissatisfied” and refuses to give her opinion on any of the “articles of purchase,” that is, the products made by the exploitation of the workers. Later, Austen lets us know what a worthless human being Robert Ferrars is by telling us he wastes his time inspecting and selecting a toothpick case... Eleanor and Marianne can't wait to get out of Gray's jewelry store. In Pride and Prejudice, long before Lydia runs away with Wickham, she stands condemned in Austen’s eyes (and ours) for wasting her money on an ugly bonnet. Her remark: “I do not think it is very pretty; but I thought I might as well buy it as not” is a perfect encapsulation of the emptiness of consumerism.

CE Brock illustration, Lydia and her bonnet In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings invites Elinor and Marianne Dashwood to go shopping with her after they reach London. Marianne, perhaps the most highly principled character in all of Austen, refuses to go at first. Whenever she is in a store, she is “restless and dissatisfied” and refuses to give her opinion on any of the “articles of purchase,” that is, the products made by the exploitation of the workers. Later, Austen lets us know what a worthless human being Robert Ferrars is by telling us he wastes his time inspecting and selecting a toothpick case... Eleanor and Marianne can't wait to get out of Gray's jewelry store. In Pride and Prejudice, long before Lydia runs away with Wickham, she stands condemned in Austen’s eyes (and ours) for wasting her money on an ugly bonnet. Her remark: “I do not think it is very pretty; but I thought I might as well buy it as not” is a perfect encapsulation of the emptiness of consumerism.Fanny Price of Mansfield Park is the most misunderstood and maligned of Austen's heroines today. But it is long past time for a critical reappraisal, starting with the fact that Fanny never goes near a store. This should put an end to the endless debates in Austen circles about Fanny Price—she is in fact a courageous anti-capitalist. Even when she visits her family in Portsmouth and is hungry after dinner, she sends her brothers out to buy biscuits and buns for her, rather than go into a shop herself.

Edmund Bertram commissions his older brother Tom to buy a piece of jewelry for Fanny while Tom is in London, but Mary Crawford is the truly admirable character who recycles a superfluous necklace that she doesn't wear very much, and gifts it to Fanny.

In Emma, it is the foolish air-headed Harriet Smith who admires every shiny item at Ford’s store. Just as Mrs. Palmer aggravates Elinor in Sense and Sensibility because her “eye was caught by every thing pretty, expensive, or new; who was wild to buy all, [and] could determine on none,” Harriet cannot make up her mind about anything and wants to buy everything when she shops at Ford's. When Mrs. Weston and Frank Churchill happen to walk by, Emma is embarrassed to be seen in the store and she is quick to let them know “I am here on no business of my own." She is still at Ford's trying to hurry Harriet along with her purchases, when she discovers she is trapped--Miss Bates comes in and begs her to come and listen to Jane Fairfax's new pianoforte. There is no escaping the disagreeable duty, and it wouldn't have happened unless Harriet had been lingering over figured muslin and yellow ribbons. But even though she has to pay an unwanted social call, Emma feels relief when "they did at last move out of the shop." Even listening to Miss Bates prattle on about nothing is preferable to being at Ford's.

At Molland's on Milsom Street Ford's is a uniquely sinister representation of capitalism in Austen. A critical examination of the plot reveals that Mr. and Mrs. Ford exercise a monopoly over all the citizens of Highbury. As Frank Churchill puts it, Ford's is "the very shop that every body attends every day of their lives, as my father informs me." Unhappy about the social pressure to engage in mindless consumerism, Frank complains: "to be a true citizen of Highbury. I must buy something at Ford’s." In this clever way Austen softens our perception of Frank Churchill, and we realize, as even Mr. Knightley acknowledges later, that he is "a very good sort of fellow."

At Molland's on Milsom Street Ford's is a uniquely sinister representation of capitalism in Austen. A critical examination of the plot reveals that Mr. and Mrs. Ford exercise a monopoly over all the citizens of Highbury. As Frank Churchill puts it, Ford's is "the very shop that every body attends every day of their lives, as my father informs me." Unhappy about the social pressure to engage in mindless consumerism, Frank complains: "to be a true citizen of Highbury. I must buy something at Ford’s." In this clever way Austen softens our perception of Frank Churchill, and we realize, as even Mr. Knightley acknowledges later, that he is "a very good sort of fellow."In Persuasion, Molland’s is the setting for an encounter between Anne, Captain Wentworth and Mr. Elliot which leaves Captain Wentworth with the notion that Mr. Elliot and Anne will be married. Austen could have placed this unhappy turn of events in a park, or at the Pump Room, but—significantly—she chose a shop. While Anne is stuck at Molland's, waiting for Mr. Eliot's return, there is not a single mention of her looking around at whatever is on sale in the store. She looks outside and up and down the sidewalk, never around her. She can't wait to get out of there: "She now felt a great inclination to go to the outer door." Who does have some kind of shopping errand in this scene? The two villains of the piece, Mr. Elliot and Mrs. Clay.

In another subtle and deft touch in Persuasion, Anne encounters Admiral Croft as he stands outside a shop, contemptuously rejecting the paintings for sale within. This stamps him as one of Austen's upright and good characters.

Admiral Croft and Anne Wentworth Catherine Morland has no choice but to go to shop after shop with Mrs. Allen after they arrive in Bath in Northanger Abbey. Some analysts of this novel point to the difference in tone between the scenes set in Bath and the scenes set at the Tilney’s home, Northanger Abbey. But the real reason for the difference has been right beneath our noses all along—Bath is filled with shops, it is a capitalist hell-hole and Catherine has one disagreeable experience after another so long as she is there. Isabella Thorpe is a selfish, shallow, character who--no surprise--wants to buy even more gaudy fashions than she can possibly afford: "Do you know," she tells Catherine, "I saw the prettiest hat you can imagine, in a shop window in Milsom Street just now—very like yours, only with coquelicot ribbons instead of green; I quite longed for it."