CMP#59 Jaw-Dropping 18th Century Kiddie Lit

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times in which she lived. Click here for the first in the series.

Clutching My Pearls is about Jane Austen and the times in which she lived. Click here for the first in the series. This post features another now-obscure female writer of Austen's time. For more, click on "Authoresses" in the Categories. The Rotchfords: a Graphic Novel, and I Don't Mean a Comic Book

You've been warned... The Rotchfords (1786)

is a children’s book by Dorothy Kilner (1755 –1836) about an upright Christian family. Like almost all children’s literature of the Regency and Victorian period, the book is heavily finger-waggy; it is filled with useful moral lessons for the little ones. One of the lessons Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford teach their children is that Blacks are people too.

You've been warned... The Rotchfords (1786)

is a children’s book by Dorothy Kilner (1755 –1836) about an upright Christian family. Like almost all children’s literature of the Regency and Victorian period, the book is heavily finger-waggy; it is filled with useful moral lessons for the little ones. One of the lessons Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford teach their children is that Blacks are people too.While it's good to know that books for children talked about showing humanity to Black people, the graphic detail, the portrayal of the Black servant Pompey, and the actions of the father, are rather jaw-dropping.

Pompey’s recitation of the cruelties he’s witnessed and experienced in the West Indies and in England is brutally frank for a children’s book. As scholar Wylie Sypher wrote in 1942, The Rotchfords goes “from the pathetic to the shocking in the harrowing Pompey episode." And Pompey’s story is just one bizarre episode in a bizarre book – bizarre to our modern sensibilities, that is. Athough Dorothy Kilner and her sister-in-law Mary Anne Kilner wrote children's books which portray real children behaving in realistic ways (for example, squabbling as they ride in the carriage), The Rotchfords reminds us that the 18th century featured more random pain and death, more casual cruelty, and more hunger and misery than we witness at first hand today.

Some examples: the youngest Rotchford boy learns the hard way that you don’t lark about in a carriage – he impulsively sticks his arms though a glass barrier and cuts himself badly. One of his arms has to be amputated, and this was before anesthesia. On another occasion, Mr. Rotchford tells his son about a bad-tempered man who beat his grandson to death for stealing peaches. Moral: don’t steal and don’t lose your temper.

Think that was harsh? Try this: A few days after a local boy pulls the tail off her pet squirrel and then strangles it to death, Kitty is surprised to see it decomposing and being eaten by worms and maggots. She asks her father, “could you have thought it possible for it to alter so?”

Mr. Rotchford uses the dead squirrel to teach a lesson about the uselessness of vanity.

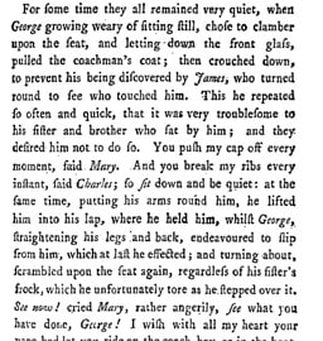

No seat belts in Georgian carriages, so little George jumps around and bothers his brother and sister. Charles raises the glass barrier so Charles will stop bothering James the coachman, but tragedy follows. Patting Kitty on the cheek, dad assures her, “'you yourself will undergo as great an alteration in a very few days after your death. All [your] bloom, my love… will then be entirely gone…'

No seat belts in Georgian carriages, so little George jumps around and bothers his brother and sister. Charles raises the glass barrier so Charles will stop bothering James the coachman, but tragedy follows. Patting Kitty on the cheek, dad assures her, “'you yourself will undergo as great an alteration in a very few days after your death. All [your] bloom, my love… will then be entirely gone…' “'And will such nasty fat-looking maggots eat me up too?” daughter Harriot asks.

“'Yes, indeed,” said Mr. Rotchford, chucking her under the chin as he spoke, ‘they will not pay respect even to your dead body; but will eat my little Harriot with as much relish as if she was but a squirrel….'"

At the time of its publication, the critics did not comment on the graphic nature of The Rotchfords. Amputation, beating children to death, and torturing squirrels, are "common occurrences" in Georgian England. But they thought the dialogue was unpolished.

Black servant as ornamental status symbol Mr. Rotchford’s interactions with Pompey also seem incredibly callous to our modern sensibilities. (Some enslaved men were given Roman names like "Pompey" and "Caesar.") Rotchford and his son Charles come upon 12-year-old Pompey weeping and shivering at the side of the road. He tells how his master, Mr. Chromis, overworked him, beat him and denied him food. Starving, he stole some food and then a little money. Mr. Chromis kicked him out of the house.

Black servant as ornamental status symbol Mr. Rotchford’s interactions with Pompey also seem incredibly callous to our modern sensibilities. (Some enslaved men were given Roman names like "Pompey" and "Caesar.") Rotchford and his son Charles come upon 12-year-old Pompey weeping and shivering at the side of the road. He tells how his master, Mr. Chromis, overworked him, beat him and denied him food. Starving, he stole some food and then a little money. Mr. Chromis kicked him out of the house.Mr. Rotchford replies: “I am sorry for it, but I cannot help it, you ought not to have robbed your master.”

Since this occurs after Lord Mansfield's Somerset decision , Pompey is not a slave. The issue is, will anyone feed him or give him a job? Apparently this was a big problem for hundreds of free Blacks after the Somerset decision. If they left their former owners, they could not necessarily find or keep another job, and since they were not considered to be members of any parish, they could not obtain parish charity. At the same time The Rotchfords was published (1786), the abolitionist Granville Sharp was collecting donations to send 400 indigent Blacks to Africa to start a colony at Sierra Leone.

Young Charles Rotchford pleads for Pompey, and his father answers, “I do not want a black boy; besides, by his own account, he has been dishonest, and robbed his master.”

Charles continues to ask for mercy for Pompey, who, let’s remember, is a crying, starving, half-naked child. Finally Mr. Rotchford smiles and tells Charles, “Believe me, I had no intention of leaving him there to perish, but I wished to hear your sentiments upon the subject.” Thanks to Pompey's suffering, Charles has passed the moral test. They take Pompey home, where he is fed and clothed and handed over to the gardener to be his under-servant.

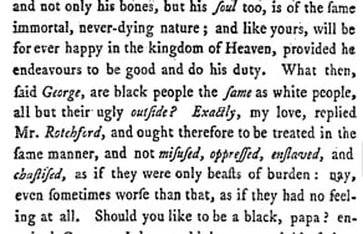

The youngest Rotchfords are alarmed by Pompey's appearance. I've seen this in other books of this era; British children are portrayed as being surprised or frightened at the appearance of Black people, or thinking the black colour will wash off their skins. Mrs. Rotchford reminds the children that standards of beauty are different in different parts of the world and it's not Pompey's fault that his lips stick out. “Is that any reason why [Pompey] should not be treated with kindness?"

Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford are uncompromising about the cruelty and immorality of the slave trade in their lectures to their children. And Pompey tells how he and his mother were abducted from their homes in Africa. His mother fell ill in the West Indies but was whipped in the sugar fields. His older brother was tortured to death for trying to protect her from the overseer’s lash. Then Pompey was sold to a man who brought him to England to be a page boy, but he was passed on to Mr. Chromis, who abused and starved him.

Pompey forthrightly says that he doesn’t like Christians because of what Christians have done to him and his family. Mrs. Rotchford acknowledges: “At present, I am not at all surprised, that he should entertain an ill opinion of a religion, [whose] members he has found to be barbarous, tyrannical and unjust…”

Mrs. Rotchford also lectures her children about the guilt of the slave-trader versus the lesser guilt of the slave-owner.

As scholar George E. Boulukos explains, and as The Rotchfords illustrates, slave-traders were held as being more blameworthy than slave-owners at this time. Slave-traders were motivated purely by greed, but slave-owners "might buy [enslaved persons] with a good intention of preventing their falling into cruel hands, and meeting with unkind treatment, and mean afterwards to give them their freedom, as I believe they have to most of them. We must not, therefore, my dears, presume to condemn every body as wicked, who may be in possession of a negroe, without knowing how, or for what reasons..."

Little George is surprised that Pompey's blood is red like his... Mr. Rotchford continues to express his doubts about allowing Pompey to stay with them. He writes to his former master, Mr. Chromis, to check the truth of Pompey's version of events. Mr. Rotchford's goal was "to endeavour to find out [Pompey's] sentiments and temper; whether he appeared as if indeed desirous of pleasing, and being good; or whether he only liked to stay for the sake of his food... For this reason, therefore, and not for the sake of occasioning him one moment’s suspense or pain, I refrained from telling him my design, till I saw how the thoughts of his departure would affect him; and whether he would esteem his continuing here an obligation worthy of being requited by his gratitude and fidelity.”

Little George is surprised that Pompey's blood is red like his... Mr. Rotchford continues to express his doubts about allowing Pompey to stay with them. He writes to his former master, Mr. Chromis, to check the truth of Pompey's version of events. Mr. Rotchford's goal was "to endeavour to find out [Pompey's] sentiments and temper; whether he appeared as if indeed desirous of pleasing, and being good; or whether he only liked to stay for the sake of his food... For this reason, therefore, and not for the sake of occasioning him one moment’s suspense or pain, I refrained from telling him my design, till I saw how the thoughts of his departure would affect him; and whether he would esteem his continuing here an obligation worthy of being requited by his gratitude and fidelity.”Pompey, in other words, must prove that he is not motivated by mere selfish considerations such as avoiding starving to death by the roadside.

This seems appalling, and yet, how much of Pompey's treatment can we ascribe to the fact of his being Black? Would the Rotchfords have taken in any and every hungry, half-naked boy that they saw? Elsewhere in the book we read about a another hungry child: "As I was walking down the lane this morning before breakfast, [Charles tells his father] I met Bob Swift, as naked and in as bad a condition as Pompey was when we found him, crying most piteously, and gathering sticks for his mother. He begged me to give him an halfpenny… then again, I recollected that you positively ordered none of us to give more to the Swifts, because they have been extremely wicked, and ungrateful.”

It's a harsh world. Pompey has been kidnapped from his home, orphaned and abused, and he'll never see his home or family again, but he must earn his keep.

Mr. Rotchford relents and says Pompey can stay. “'Me be good! me be good!,'” Pompey promises, "kissing his master’s hand, and jumping about the room, hallowing, singing, dancing, and shewing every sign of immoderate joy that he could express; then throwing himself on the floor, he clasped and kissed Ms. Rotchford’s knees; then did the same to Charles.

The Rotchfords ends abruptly, and we are not told what becomes of Pompey as he grows; whether he is paid a wage, whether he stays with the family for the rest of his life, or whether he learns a trade.

Dorothy Kilner (1755 - 1836) The Rotchfords was reprinted and excerpted into the 19th century. Professor Srinivas Aravamudan included the Pompey episode in the anthology series Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period. As he pointed out: “While sterile critical debates have raged over the extent to which a novel such as Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) is anti-slavery in its sensibility… much of this recent criticism has not expanded into a reconsideration of the wider arena."

Dorothy Kilner (1755 - 1836) The Rotchfords was reprinted and excerpted into the 19th century. Professor Srinivas Aravamudan included the Pompey episode in the anthology series Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period. As he pointed out: “While sterile critical debates have raged over the extent to which a novel such as Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) is anti-slavery in its sensibility… much of this recent criticism has not expanded into a reconsideration of the wider arena." And when we look at this wider arena we can clearly see that it was not taboo to write about slavery, as I've noted before . The author of The Rotchfords, Dorothy Kilner was writing to make money, not alienate her readers. There was a market and an audience for pro-abolition literature. The review was critical of Kilner's prose style, but made no objection to the anti-slavery material.

Moira Ferguson calls Kilner's lectures, placed in the mouths of Mr. and Mrs. Rotchford, “one of the fiercest fictional statements by a female writer before abolition.”

Scholar Cheryl Turner describes Kilner as one of the "obscure novelists who have virtually disappeared from our literary histories." Kilner published under the pseudonyms M.P. and Mary Pelham, hiding her authorship to maintain her middle-class respectability. Her best-known work was The Life and Perambulations of a Mouse. If it's true that this was the first children's book written from the perspective of an animal (the most famous example of this genre is Black Beauty), then Kilner was an innovator as well.

Ferguson, M. (2014). Subject to others : British women writers and colonial slavery, 1670-1834, Routledge.

Sypher, W. (1969). Guinea's captive kings : British anti-slavery literature of the XVIIIth century. Octagon Books.

Turner, Cheryl. (1993). Living by the Pen: Women Writers in the 18th Century (1st ed.). Routledge.

Published on July 15, 2021 00:00

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Tammy

(new)

Jul 19, 2021 08:32AM

Jaw dropping indeed. Fascinating.

Jaw dropping indeed. Fascinating.

reply

|

flag