Lona Manning's Blog, page 27

September 19, 2020

CMP#4 Implicit values: Law & Order

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Law and Order

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: Law and Order

In this series, I’m going to discuss the question, what are Austen’s novels about? They are about more than romance and marriage, of course, although many people enjoy them for the love stories. What gives them their universal, timeless appeal? And are we really supposed to like Fanny Price more than Mary Crawford?

In this series, I’m going to discuss the question, what are Austen’s novels about? They are about more than romance and marriage, of course, although many people enjoy them for the love stories. What gives them their universal, timeless appeal? And are we really supposed to like Fanny Price more than Mary Crawford?In an earlier post, I mentioned that I don't think they are about political or social themes. Jane Austen is a moralist who critiqued the world around her, but she's not a revolutionary.

The first example I’m going to look at in depth involves Dr. Helena Kelly's take on the hidden meaning of the militia in Pride & Prejudice.

According to Dr. Kelly, when the militia marches into town, the reader should be feeling an uncomfortable tingle up the back of his neck. “The presence of militia in the novel… introduces layer upon layer of anxiety.”

During the period in which Pride & Prejudice was set, England was at war with France and on alert to repel a French invasion. (One attempt was made but in the end there was no invasion from France). The militia served as a home guard to repel a French invasion while the regular army was fighting on the continent. Marilyn Butler notes that "By the winter of 1794–5 three such regiments—the South Devonshires, Oxfordshires, and Derbyshires—were billeted in counties near north Hampshire, and they caused trouble locally through riotousness, drunkenness, lechery, and bad debts. Their senior officers were either professional soldiers or gentlemen but the men and junior officers were inexperienced and, like Lieutenant Wickham in Pride and Prejudice, might be disreputable."

Austen doesn't dwell on this side of things. Kitty and Lydia go into a tizzy over the officers. Even Mrs. Bennet is excited, ("I remember the time when I liked a red coat myself very well—and, indeed, so I do still at my heart") and Mr. Bennet rolls his eyes and goes to his study.

The militia undoubtedly posed problems but they also caused great excitement and diversion. Just imagine how a regiment of militia would liven up your sleepy country village. The Regency cartoonist George Cruikshank wrote a brief memoir about his happy childhood days playing soldiers with his brother when his father joined the militia. You can picture little boys running around with sticks, watching and imitating the soldiers, while Lydia and Kitty think of every excuse they can to go into town. And those drunken soldiers are paying for their ale in the local tavern--good for business.

Should the people of Meryton be worried about their own safety? There were occasions, notably in Ireland, when the militia was used to put down rebellions. Controlling the populace was the “unspoken reason for having militia in the first place,” Dr. Kelly writes.

Actually, putting down seditious uprisings was the reason for having a militia. Nothing unspoken about it. It was right there in the founding legislation. There was no police force in Regency England, nor could the economy of that time sustain a standing police force everywhere, so gentlemen in every county were appointed officers of the militia and able-bodied men were trained at regular intervals, to be called out in the event of emergencies, such as popular rebellion.

Supposing that a riot erupted in Meryton and the officers were ordered to put it down. Kelly starts with the assumption that someone of Austen's time would not identify with the officers, but with the rioters. Really? Austen is writing for the propertied, monied, class, not landless peasants.

After presenting the militia as threatening, Kelly flips the argument around and suggests Austen wants us to feel sympathy for the soldiers, because “a private had been flogged,” and flogging is a cruel punishment. “There’s a nasty underbelly to all these fun and games.”

Whether we are talking about militia putting down a protest, or soldiers being flogged, we must remember that Georgian sensibilities were not as tender as ours, and certainly not as tender as Dr. Kelly's.

Further, from the point of view of the mechanics of the story, how else could Wickham come to the small town of Meryton? How else could he, an ambitious social climber, the son of a steward, be introduced to the Bennet girls? And why else would he go away to Brighton, and how else could Lydia follow without her family, without the use of the militia as a plot device?

Further, from the point of view of the mechanics of the story, how else could Wickham come to the small town of Meryton? How else could he, an ambitious social climber, the son of a steward, be introduced to the Bennet girls? And why else would he go away to Brighton, and how else could Lydia follow without her family, without the use of the militia as a plot device? Austen uses the same device to explain how Mr. Weston in Emma met his first wife, who was his social superior. He was a captain. Are we to feel anxious and uneasy about Mr. Weston as well? Are we to picture this genial man flogging his troops?

We can look to the reactions of Austen's characters to see if Austen approves or disapproves of something. Is there any evidence that the militia have made the people of Meryton uneasy? Does anybody react with hostility? Even after Wickham elopes with Lydia, Mr. Bennet speaks of taking Kitty to a review (a large gathering where the soldiers march on display), as a reward for good behaviour.

Finally, how can Kelly square her theory that Austen and her readers would be hostile to the militia with the following passage in Northanger Abbey?

The hero of Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney, is funny and fanciful and satirical. He is taking a walk with his sister Eleanor, who is intelligent, kind and thoughtful. And with them is the heroine, young Catherine Morland. They are all nice, good people.

Catherine mentions that she’s heard about a new gothic horror novel: “I have heard that something very shocking indeed will soon come out in London.”

Eleanor misunderstands her and thinks Catherine is speaking of a pending mob uprising. “You speak with astonishing composure! But I hope your friend's accounts have been exaggerated; and if such a design is known beforehand, proper measures will undoubtedly be taken by government to prevent its coming to effect.” Henry clears up the misunderstanding in his jesting way. "Dear Eleanor, the riot is only in your own brain. The confusion there is scandalous. Miss Morland has been talking of nothing more dreadful than a new publication which is shortly to come out... do you understand? And you, Miss Morland—my stupid sister has mistaken all your clearest expressions. You talked of expected horrors in London—and instead of instantly conceiving, as any rational creature would have done, that such words could relate only to a circulating library, she immediately pictured to herself a mob of three thousand men assembling in St. George's Fields, the Bank attacked, the Tower threatened, the streets of London flowing with blood, a detachment of the Twelfth Light Dragoons (the hopes of the nation) called up from Northampton to quell the insurgents, and the gallant Captain Frederick Tilney, in the moment of charging at the head of his troop, knocked off his horse by a brickbat from an upper window. Forgive her stupidity. The fears of the sister have added to the weakness of the woman; but she is by no means a simpleton in general.”

Eleanor speaks with alarm about a populist revolt, Henry with levity. But their sympathies lie entirely with the soldiers and against the mob, whom Henry describes as insurgents. Eleanor expects the authorities will take "proper measures." Does Austen expect her readers to agree with the hero and his very nice sister? And can we not infer from this passage that Austen agrees that violent protests should be met with armed force to keep the peace?

Eleanor speaks with alarm about a populist revolt, Henry with levity. But their sympathies lie entirely with the soldiers and against the mob, whom Henry describes as insurgents. Eleanor expects the authorities will take "proper measures." Does Austen expect her readers to agree with the hero and his very nice sister? And can we not infer from this passage that Austen agrees that violent protests should be met with armed force to keep the peace?As Paula Byrne notes in her biography of Austen, It's quite possible that Tilney's description is based on the frightening experience of her cousin Eliza DeFeuillide, who was caught up in a riot in London in 1792, causing her to miscarry. If so, it's a very light-hearted handling of an event which terrified her cousin, whose driver was injured by a flying projectile.

It’s also possible that Austen revised the novel before her death. Although Northanger Abbey was written shortly after the French Revolution, it was published posthumously. Henry Tilney could be making a glancing reference to the Spa Fields riots of 1816, when a radical named Arthur Thistlewood attempted to raise a mob to storm the Tower of London.

It’s possible too that if Austen had lived long enough to hear about Peterloo, when armed cavalry rushed into a large peaceful crowd, hacking and slashing, she might have moderated her views. But Peterloo occurred almost three years after Austen’s death.

However, based on the the text, it does not appear that the author of Northanger Abbey feels any sympathy for popular uprisings, or assumes that her readers would, either.

Next blog post, more on Pride & Prejudice--is it anti-nobility?

Published on September 19, 2020 20:39

CMP#3: Secret Radical Redux

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction.

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction.

Austen had an irrepressible sense of humour and it might as well be Jane Austen speaking to us directly when her beloved creation Elizabeth Bennet says, “Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies, do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can.” We talk about the crudity of our times--or at least, my times, with our gross-out comedies like American Pie--but you can’t beat the Georgians for cruel humour, and Austen was born a Georgian. She laughed about tragic things like miscarriages and a fat woman mourning the death of her son. Both Elizabeth Bennet and Mary Crawford make wisecracks about an older son dying so his younger brother can inherit.

Austen had an irrepressible sense of humour and it might as well be Jane Austen speaking to us directly when her beloved creation Elizabeth Bennet says, “Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies, do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can.” We talk about the crudity of our times--or at least, my times, with our gross-out comedies like American Pie--but you can’t beat the Georgians for cruel humour, and Austen was born a Georgian. She laughed about tragic things like miscarriages and a fat woman mourning the death of her son. Both Elizabeth Bennet and Mary Crawford make wisecracks about an older son dying so his younger brother can inherit.Austen laughed about the wrenching poverty all around her and the injustices meted out to women. In her mature years, after completing Emma, she wrote a very funny little outline of a novel . In which she writes that the heroine is “often reduced to support herself and her Father by her Talents and work for her Bread; continually cheated and defrauded of her hire, worn down to a Skeleton, and now and then starved to death.”

Of course comedy can tackle serious subjects. That's the entire purpose of satire. Professor John Mullan says Austen is ‘the most unflinchingly satirical of all great novelists." But Jane Austen is never harsh and biting like Swift. I recently learned there is a name for Austen's brand of satire, Horatian satire. "Horatian satire is the mildest and gentlest form of satire there is—it is not seeking to change the world. It is merely focused on highlighting human folly in all its myriad forms, perhaps through anecdotes and characterisation more so than plot, and so its chief purpose is, primarily, to amuse." The term traces back to the Roman Empire and the In an earlier blog series, I critiqued the book, Jane Austen: the Secret Radical. To recap here, Dr. Helena Kelly, while acknowledging that Austen is sometimes comic, argues she is altogether more serious and critical than people realize. The reason people don't realize this is because Austen had to hide her criticisms of society because she lived "in a state that was essentially totalitarian." Kelly says Jane Austen was a writer who wanted to write seriously, critically, about injustice and women's rights, and corruption but hide to hide her message. Austen was really a secret radical.

Kelly claims to find the following themes hidden in Austen and says these themes are controversial: Northanger Abbey: Sex is dangerous (i.e. it could result in death in childbirth). This was a fact of life and not a taboo subject at all.

Pride & Prejudice: Kelly’s vague on this, but pro French Revolution, ie against aristocracy and the class system.

Mansfield Park: Slavery is bad. (Ending the slave trade was official government policy when Mansfield Park was written).

Primogeniture (Sense & Sensibility) and land enclosure (Emma) are bad. (But not illegal to complain about).

Persuasion: life is full of change and uncertainty. (By the end of her book, we suppose, the reader has forgotten the original thesis that Austen was promoting dangerous views.) Yes, people were censored in Austen's time. The government brought prosecutions for "seditious libel," spreading false and/or dangerous views that threatened the stability of the government and the monarchy. Writing about overthrowing the aristocracy would get you in big trouble. Insults directed at the King or the Regent would get you locked up, no question. In my Mansfield Trilogy, a writer gets convicted of seditious libel for criticizing government policy. Some radicals fled the country to avoid imprisonment, others were ostracized socially and professionally.

But the topics Kelly lists? She might have strengthened her case if she had presented actual examples of people charged with seditious libel for writing about abolition, primogeniture, land enclosure, dying in childbirth, or the unpredictability of human events. Mary Wollstonecraft wasn't prosecuted for writing the response to Edmund Burke. William Godwin wasn't prosecuted for writing Caleb Williams. Maria Edgeworth wasn't prosecuted for Castle Rackrent. All of these works are heavily critical of the status quo. Was anyone prosecuted for writing "about a world in which parents and guardians can be stupid and selfish, in which the Church ignores the needs of the faithful, in which landowners and magistrates... are eager to enrich themselves"? So far I haven't found any examples.

And if they were not actually arrested but were condemned socially? Well, we certainly have many instructive examples of people being shamed and cancelled today, for the noblest of motives, by the most virtuous people. Perhaps those people in the Regency period had their reasons. The subjects Dr. Kelly claims to find hidden away in one book are out there, in plain sight, in another book. This doesn't mean I agree that these are significant themes in any of these books, but:

Mansfield Park is supposedly pro-abolition. The word “abolition” doesn't appear in Mansfield Park, but it is found In Emma, when Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Elton mention the slave trade.

Northanger Abbey is supposedly about the terrifying reality that sex could lead to death in childbirth. But Austen jokes in the opening pages of the novel that Mrs. Morland didn’t die when giving birth to Catherine, as might be expected of a heroine’s mother. Nobody’s mother dies of childbirth in Northanger Abbey. In Emma, on the other hand, we have three people whose mothers die young—Emma Woodhouse, Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill.

But Emma isn’t about slavery or dying in childbirth, it’s about land enclosure. Kelly says there is a “preoccupation with land enclosure” in the novel. Yet, despite this preoccupation, the word “enclosure” doesn’t appear in Emma. Not once. It's mentioned twice in Sense & Sensibility. But Sense & Sensibility isn’t about land enclosure, it’s a protest against primogeniture, the practice of leaving the estate to the oldest son. Yet, heirs and inheriting feature in all the novels, such as in Pride & Prejudice, when Colonel Fitzwilliam says that younger sons can't marry where they like.

But Pride & Prejudice isn’t about primogeniture, it’s about class distinctions. But Emma and Persuasion have plenty of explicit discussions about rank and class. But Persuasion isn’t about class distinctions. It’s about the uncertainty of human events. Although it is Emma who exclaims: "Was it new for any thing in this world to be unequal, inconsistent, incongruous—or for chance and circumstance (as second causes) to direct the human fate?" Finally, as I have previously argued, Dr. Kelly is finding allusions in Austen that just aren't there. In this respect, Dr. Kelly's theory is non-falsifiable. Thesis: Austen is advocating class overthrow in Pride & Prejudice.

Me: But she isn't advocating class overthrow in Pride & Prejudice.

Thesis: That's because if she said it openly, she'd be arrested.

Me: So if she isn't saying it, how do you know that's what she meant to say? I will look at the supposed radical views in Pride & Prejudice in a future post. But first, a closer look at another topic Dr. Kelly discusses in Pride & Prejudice: the militia.

Published on September 19, 2020 15:01

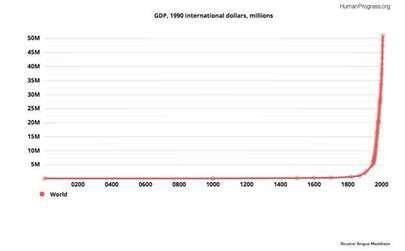

CMP#2: The most important chart in the world

The most important chart in the world - click to see more detailed version Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction to the series.

The most important chart in the world - click to see more detailed version Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the introduction to the series.I’m going to review some of the implicit values in Austen's novels. For example, it is Austen’s conviction that emotions should be kept under control. Personal morality, and not larger social issues, are the explicit themes of Austen's novels.

First though, I'll start with what might appear to an irrelevant diversion. But it’s important because it undergirds everything I’ll be saying about Austen and her times.

When discussing (or condemning) the attitudes and actions of people who lived two hundred years ago, there is one crucially important thing to keep in mind, and it is summed up in this chart which shows global gross domestic product from 0 BCE to the present day. Before the industrial revolution, as economist Carl Benedikt Frey explains, "For the majority of the English as late as 1813, conditions were no better than for their naked ancestors of the African savannah. The Darcys were few, the poor plentiful."

But GDP leaped up like a rocket with the advent of industrialization. The history of mankind up until that time was the history of manual labour, corvee labour, serfdom and chattel slavery. Austen lived and died at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, when that chart was just beginning to curve up.

Most people’s lives were taken up with working to have adequate food and shelter. When Britain led the way with mechanization and free trade, look what happened.

For the first time, people could travel by train, faster than a horse could gallop. For the first time, ships were not at the mercy of the winds. For the first time, people had gas lighting, an alternative to wood fires and candles. As wealth grew, slavery and serfdom decreased. The British government devoted considerable resources to patrolling the seas around Africa and suppressing the slave trade. The difficult, dangerous campaign of the West African Squadron is featured in my Mansfield Trilogy.

Compared to Regency England, the prosperity of our times is staggering. It’s easy to lose sight of this because what has survived from the past are not the many hovels of the poor, but the few stately homes of the rich. The rags of the beggar are gone but some of the embroidered gowns still survive. It is difficult to imagine a world in which the Prince Regent lived in luxury in Brighton, while some of his subjects were literally starving to death as happened in 1816 (“the year without a summer”).

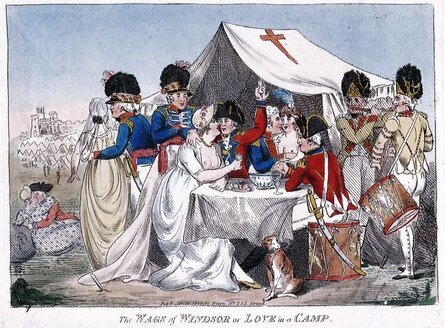

The impression we get from those rollicking Regency cartoons with their fat squires and fat ladies is that England was a land of plenty and security. But half of the poor people in the world today enjoy comforts and luxuries and security that a Regency duke couldn’t have dreamt of. Light at the flick of a switch. Running hot and cold water. Clean, efficient sewage systems. Air conditioning and central heating. Cars, trains, airplanes. Antibiotics and painkillers. Life-saving surgery. Fresh vegetables and fruits from all over the world, year round. Public schools and the internet.

Political cartoon by George Cruickshank

Political cartoon by George Cruickshank

Louis Lépold Boilly Young Woman Ironing about 1800-03 The comforts that wealthy people did enjoy in Austen’s time were brought to them by their servants, not by electricity. Their meals were cooked and served, their hair washed and styled, their houses cleaned, by other hands than their own.

Louis Lépold Boilly Young Woman Ironing about 1800-03 The comforts that wealthy people did enjoy in Austen’s time were brought to them by their servants, not by electricity. Their meals were cooked and served, their hair washed and styled, their houses cleaned, by other hands than their own.If you’re rolling your eyes and saying, “yeah I know, I know” – that's great!

On the other hand, if you don’t know much about the British Empire and colonialism and the Great Divergence, I'm not going to accuse you of not wanting to know about poverty and slavery and people of colour. That’s not where I am going with this. I am laying the foundation for a discussion of the way Austen and her fellow Britons looked at the world.

And of course, there were a variety of opinions in Austen’s day—they were not monolithic in their thinking any more than we are today. In fact, the more I read about this period, the more I am struck by its resemblance, politically, to our present times.

So I’ll be referencing that chart of prosperity more than once, to ground us in Austen’s world, a world that was different from our own. For example, consider the wages of sin in Austen’s time. In a society with a slender margin between survival and death, it only makes sense that hard work, sobriety, and chastity were stressed. People were not shielded from the consequences of their actions.

I’m also going to look at how Austen portrays her heroes and heroines, her fools and her villains, and look at the opinions she puts in their mouths, and the behaviours they display.

Also, I’m going to revisit Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, which I’ve already written about, but I find there is more I want to say and fact-check!

So now that we've laid the foundation, let's lay down some basic postulates.

When we look for clues as to what a book is “about,” the first place to look is in the text. Right in the text, not between the lines.

Let's postulate that if Austen endows a character with likeable qualities, and they occupy the space in the book typically occupied by the hero, (they marry the girl at the end), it is safe to assume that this person is the hero.

Next, let’s postulate that these good, likeable people have opinions which reasonable people of Austen’s time would agree with. Good people are respectful to their parents and elders, for example, and bad people aren’t—this is consistent across Austen’s six novels.

If Austen puts an opinion into the mouth of one of her fools or villains, this also tells us about her own opinions. It’s pretty clear she is opposed to uncharitable, selfish people, by her portrayal of John Dashwood and his dreadful wife Fanny in Sense & Sensibility. Two men who make proposals of marriage (Henry Crawford and Mr. Collins) are guilty of not taking ‘no’ for an answer, of not viewing women as ‘rational creatures.’ Isabella Thorpe is a complete hypocrite. Austen prizes sincerity.

“No, indeed, I shall grant you nothing. I always take the part of my own sex. I do indeed. I give you notice—You will find me a formidable antagonist on that point. I always stand up for women.” Who says this? It’s Mrs. Elton in Emma. So the most overtly feminist statement in the canon comes from the mouth of one of her fools. What are we to make of that? Shall we turn the book upside down and insist that Mrs. Elton isn’t a fool, she’s a heroine? Or shall we admit that Austen can laugh about anything and perhaps she found officious feminists just as irritating as any other species of fool.

“No, indeed, I shall grant you nothing. I always take the part of my own sex. I do indeed. I give you notice—You will find me a formidable antagonist on that point. I always stand up for women.” Who says this? It’s Mrs. Elton in Emma. So the most overtly feminist statement in the canon comes from the mouth of one of her fools. What are we to make of that? Shall we turn the book upside down and insist that Mrs. Elton isn’t a fool, she’s a heroine? Or shall we admit that Austen can laugh about anything and perhaps she found officious feminists just as irritating as any other species of fool.My argument is that Austen was not a secret radical. I think she was an abolitionist, yes. But she didn’t crusade for an end to the slave trade in her books. Of course we can’t help thinking about the slave trade as we read Mansfield Park . When I wrote my Mansfield Trilogy, the issue of the slave trade became an integral part of the plot--how could it not? It is uncomfortable, to say the least, to read about the domestic problems of a family who live off slave labour. Compared to the nightmare that was life on a sugar plantation in Antigua, the hardships Fanny suffers, the persecutions of Aunt Norris, are trifling, they are as a drop of water to the ocean. That’s the context in which we now read this book. But we bring that to the text, not Austen. If you think Mansfield Park is about slavery, I disagree, and I'll explain why later.

In future posts, I’ll be discussing the novels, reacting to some post-modern interpretations of Austen and giving my reasons for thinking that Mansfield Park is about education (not slavery), Sense & Sensibility is about self-control (not primogeniture), Emma is about self-deception (not land enclosure), and Pride & Prejudice is not about class overthrow.

Next post: Secret Radical Redux

Published on September 19, 2020 14:22

September 11, 2020

CMP#1 Introduction to the series

La lecture chez Diderot Hello and welcome to a new blog series which I’m calling “Clutching My Pearls.”

La lecture chez Diderot Hello and welcome to a new blog series which I’m calling “Clutching My Pearls.”I have thoughts. And a lot of those thoughts have to do with disagreeing with the proposition that Jane Austen was a fierce social and political critic of the times she lived in.

Unquestionably, her world was much poorer and crueler than our own. Austen was 6 years old when the last man was hung, drawn and quartered for treason. She was 13 when the last woman was burned at the stake (for counterfeiting money, not for witchcraft.) The year before she died, a massive famine afflicted Europe and England, and there were widespread riots for bread.

It was also an extraordinarily eventful time in history. Austen stands at the crossroads between the rowdy Georgian age and the strait-laced Victorians, at a time of important innovations in agriculture and manufacturing. During her life, Britain was convulsed with political and social unrest, not unlike our own time. England was at war for almost the entire course of her life. The British Navy sailed to the four corners of the earth, and slave ships transported slaves to British colonies in the West Indies.

Austen was a child of the Enlightenment, a flowering of thought whose importance to human progress cannot be understated. The long 18th century also saw the dawn of the Romantic period, the time of Byron and Beethoven and Sir Walter Scott.

And yet, in the midst of all this upheaval, change, cruelty, racism and poverty, Austen's genteel characters talk pleasantly and drink tea and go for walks in the shrubbery. Austen doesn’t write about battles or social unrest (with one notable exception). She seldom alludes to public events, and then only in passing. She focusses on people’s private conduct, their wishes, their mistakes, their follies. In her wry examination of human nature, fans and critics have found plenty to enjoy, re-read, think about, and write about.

So, is there anything more to her books? Is there yet another layer beyond the personal, the individual relations of her characters? Did she intend anything more?

Many have claimed to find a great deal. In this series, I will be arguing that readers are finding radical messages in Austen because they want--in fact they need--to find them there. The modern academics who despise England’s colonial past and despise “Whiteness” can’t, in good conscience, enjoy the works of a white woman who belonged to a privileged social class and used sugar produced by slaves. The only way they can continue to enjoy Austen is to believe that she also despised and condemned her own culture, that she seethed with resentment against the patriarchy.

I am not speaking of taking Austen and creating something new--writing a variation of her novels set in modern times, or with a same sex-couple, or what have you. That's perfectly legitimate artistic expression. I'm talking about wanting to see things in Austen that are not there, and not wanting to see the things that are there.

If you don’t view Western civilization as entirely a force for evil and if you don’t condemn everything that has happened on this globe since Columbus got lost on his way to China, you might not even know who or what I’m referring to. Those not familiar with this culture war might think I am criticizing a very small group of people whose nihilistic views are inconsequential. This is not the case, and I’ll have more to say about that later. In public discourse today, people are being bullied into making binary choices. When someone defends the advances of Western Civilization, they are attacked for being indifferent about human suffering, colonialism, and the slave trade. I'll be arguing for nuance.

The ideas I'll be presenting are mine, but I don't claim that they are all original. Much has been written about Austen.

To start with, I’ll assert that politically, Austen was a Tory. She was not remotely radical or revolutionary.

To start with, I’ll assert that politically, Austen was a Tory. She was not remotely radical or revolutionary.Secondly, Austen is a superb writer, and a genius at sketching characters, but she deliberately declined to grapple with politics and controversial public topics.

Austen doesn’t touch on politics, except in passing. “A strange business this in America, Dr. Grant!,” says Tom Bertram to the local clergyman. “What is your opinion? I always come to you to know what I am to think of public matters.” We never hear Dr. Grant's answer, and it doesn't matter. Austen uses the "strange business" as a funny bit of diversion, because Tom's afraid Dr. Grant overheard the rude thing he just said.

Neither does Austen take on social issues. Tithing, for example, is a social issue. Tithes—a portion of the agricultural produce of a parish—were given to the clergymen of that parish. Naturally, “[t]he collection of tithes was the cause of much ill-feeling between farmers and clergy,” as Eileen Sutherland writes in Persuasions. Austen’s father was a clergyman; she would have heard about tithes all her life. But Austen laughed at the suggestion that she include the issue of tithing in one of her novels. She lampooned it in her Plan of a Novel which includes a clergyman who inveighs against the system. “[T]he poor Father, quite worn down, finding his end approaching, throws himself on the Ground, and after 4 or 5 hours of tender advice and parental Admonition to his miserable Child, expires in a fine burst of Literary Enthusiasm, intermingled with Invectives against holders of Tithes."

I can’t say it better than Professor Robert Garnett:

"[Austen's] novels dramatize not social ills, but individual failings: vanity, greed, pride, selfishness, arrogance, folly. For all her humor and wit, she was a rigorous moralist. Adult life demanded adult behavior: self-awareness, propriety, kindness, good sense." Austen's view of human conduct was profoundly shaped by the ideas in Adam Smith's book, A Theory of Moral Sentiments . If we want to understand Austen, it helps to understand the theories that underlie the implicit values in Austen--such as attitudes about poverty, class distinctions, savages and civilization--and explicit values like self-command.

I’ll quote Austen’s novels and letters to support my argument, looking especially for those occasions when she “breaks the fourth wall” and addresses her readers directly. Also, I’ll look at the plot and structure of the novels and her depiction of the characters to search for the ideas and beliefs (or as Austen would put it, the convictions and sentiments), most important to her. I'll also re-visit and dispute the assertion that Austen was a secret radical. And I'll share some examples of Austen's genius.

Next post: The most important chart in the world

Published on September 11, 2020 19:36

August 31, 2020

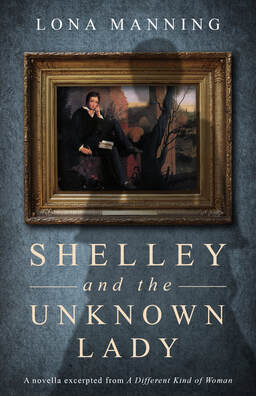

Book Cover and ARCs

I'm so excited about this book cover for the novella that I can't wait any longer. Here it is, by Tim Barber of Dissect Designs. There's Shelley at the Baths of Caracalla. The novella, which is excerpted and expanded from my latest novel, "A Different Kind of Woman," will come out on October 5th in e-book on Kindle and other platforms. I'm offering ARC's (Advanced Reader Copies) through BookSprout, so just follow this link and help yourself, or contact me for technical assistance.

For both this book and ADKW, I did a deep dive into Shelley's life and times and I'm still fascinated by him. He was brilliant, but also at times incapable of seeing (or feeling) anyone else's point of view. Also, his friends say he had a vivid imagination, or was there more to it? I am sure I'm going to be researching and writing more about that strange incident in North Wales in 1813.

Here's a brief blurb about the novella: Percy Bysshe Shelley’s brief and turbulent life was as passionate as his poetry. Romantic, idealistic and impulsive, Shelley had several intense love affairs. When Shelley drowned at sea in 1822, he took his secrets with him.

Did a beautiful, lovelorn lady really follow him throughout Europe, as he claimed? Did Mary Shelley ever learn about this rival for her affections?

Shelley and the Unknown Lady is a carefully researched imagining of the true-life tragedy behind the mystery.

This novella is a stand-alone story excerpted from Lona Manning’s Mansfield Trilogy.

Published on August 31, 2020 18:09

August 30, 2020

Mary Shelley's Birthday....

...is today, so perhaps it's appropriate (or not inappropriate, as a Regency writer would say) to post a portion of my forthcoming novella, which mentions her birthday.

...is today, so perhaps it's appropriate (or not inappropriate, as a Regency writer would say) to post a portion of my forthcoming novella, which mentions her birthday.In this excerpt, Mary Crawford (a character from Jane Austen's Mansfield Park,) is having an affair with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and decides to reveal herself to Mary Shelley. They are in Bagni di Lucca, a resort in Italy.

My novella, Shelley and the Unknown Lady, which is excerpted from my Mansfield Trilogy, will be released on Kindle on October 5th. The last day of August was the hottest day of the year, and also the day which saw the end of Mary’s patience. She could endure it no longer. She would declare herself to Mrs. Shelley. She took up her bonnet and parasol, and marched up the quiet, sleepy street to the Casa Bertini. The heat was so oppressive she had to pause at the top of the street to catch her breath. Her breakfast was disagreeing with her and she felt light-headed. She took a few deep breaths, then knocked at the door of the Shelleys’ home.

After a few moments of dreadful suspense, the door was opened by a man she had never seen before; not a servant, but an older English gentleman, carelessly attired in rumpled clothing, with thinning hair and a prodigious nose.

“Yes, madam?” the man said.

“I am Mary Bertram,” Mary heard herself say. “Is Mrs. Shelley within?”

The man opened and closed his mouth twice, then said, “I—well—just a moment please.”

He turned back into the hallway and called, “My dear! My dear, there is a young lady here—she is looking for Mary....” A female voice answered from within, and at last, a handsome-looking older woman, plainly but neatly dressed, came to the door.

She looked up and down at Mary with an intelligent, appraising look and said, “I am Mrs. Gisborne, a friend of Mrs. Shelley. I’m sorry, I did not hear your name.”

“I am Mary Bertram—I have been staying here at Bagni di Lucca, and made the acquaintance of...” Mary stopped herself—she could not actually claim acquaintance with Mrs. Shelley, because the lady might appear in a moment and deny it.

“Oh! Mary told me, most positively, she had met no-one at all since coming here.”

“Yes,” added the man. “We thought she would be passing her birthday all alone, you know. That’s why we came from Livorno.”

Mary nodded. “Her birthday—yes, just so.” She had not anticipated having these two strangers for an audience and was adjusting her thoughts, when the lady asked: “Did Mrs. Shelley not inform you of her departure? Did she send you no note? But, to be sure, it was unplanned and she left in such a hurry!”

“What—is she gone then, ma’am?”

“Yes,” the man chimed in. “Yes, Mrs. Shelley and the children left for Venice this morning.”

“Not Venice, Mr. Gisborne,” the lady corrected him. “They are going to—”

“But wait!” cried the man, looking at Mary suspiciously. “You are not enquiring in any official capacity, are you?”

Mary was too confused by the question to make any sort of reply, even in denial.

Claire Clairmont, Mary Shelley's step-sister “Perhaps she was sent by the landlord? Mary asked us—”

Claire Clairmont, Mary Shelley's step-sister “Perhaps she was sent by the landlord? Mary asked us—”“Oh, tush, husband!” cried the lady. “She is English. Pardon me, madam,” she added, turning back to Mary. “Mrs. Bertram, you say? Mrs. Shelley, I am certain, did not mention meeting a Mrs. Bertram.”

“Rather,” Mary suddenly thought to say, “that is, my acquaintance was with Miss Clairmont, in point of fact—you say they are gone?” Mary tried to look past the Gisbornes, into the house behind them. “All gone?”

“Yes, this morning,” Mrs. Gisborne repeated politely.

“And—she took the dear, dear children with her?”

This last improvisation convinced Mrs. Gisborne that the stranger on the doorstep was indeed a friend of the family, and she responded in a more confiding manner: “Yes, gone very early in the morning, and the poor baby was most unwell. She is teething. I am very anxious for her. It is dreadful to be travelling with little children in this heat! I advised Mrs. Shelley against it, but she would go!”

“I am quite surprised—that is, I was given to understand they intended to remain here for another month at least, so I did not expect to hear they are gone so abruptly.”

“Yes!” nodded the man. “In point of fact, Mary—I mean Mrs. Shelley—had just invited us to come and stay with her here, whilst her husband was gone. It is her birthday, you know. Poor girl. Then a letter arrived from Shelley yesterday, urgently demanding she come away, and now, here we are, left behind to pack up the last of their things.”

“How very obliging of you, Mr.—Mr. Gisborne?” Mary murmured uncertainly.

“Yes,” his wife repeated patiently. “I am Maria Gisborne, and this is my husband.”

“So very pleased to make your acquaintance,” Mary returned, trying to think of an opening, more questions to pose. The sun was beating down on her back and she longed to be invited in. “Perhaps, Mrs. Gisborne,” she ventured, “perhaps Mrs. Shelley’s sudden departure has to do with the Italian servant, and the—incident. Perhaps they wanted to remove their manservant from the reach of the authorities here.”

“Incident?” said Mr. Gisborne.

“You recall, dear, Mary mentioned it to us. A stabbing in the village,” Mrs. Gisborne replied, then turning again to Mary, she added decisively, “I think not, Mrs. Bertram. Why would Mrs. Shelley risk the health of her child for a servant of no very good character? Especially if he was the culprit? And I do not imagine that word of the affray would have reached Mr. Shelley by the time he sent his letter. But he was most insistent that she leave immediately—immediately!”

“I see. Then—where did you say they were going?”

“Dear, recollect that Mary asked us—” Mr. Gisborne said.

“Oh, very well, Mr. Gisborne, but she surely she meant, not to communicate anything to the landlord or the tradespeople. Mrs. Bertram,” Mrs. Gisborne added, turning to Mary with a nod, “no doubt Miss Clairmont will send you word of their new direction, but you see, we cannot, after promising Mrs. Shelley so faithfully. I do know she is not gone to Venice, and Mr. Shelley and Miss Clairmont have departed Venice as well.”

“I—I see,” Mary said again, and for perhaps the first time in her life, words failed her. She did not know what else to say, or to ask.

“Well, then,” said Mrs. Gisborne, placing her hand upon the doorknob.

Bagni di Lucca, where the Shelleys lived in the summer of 1818 Mary nodded, defeated, and started to turn away, but the courtyard began to tilt and swirl around her, and she grabbed on to the door frame to support herself.

Bagni di Lucca, where the Shelleys lived in the summer of 1818 Mary nodded, defeated, and started to turn away, but the courtyard began to tilt and swirl around her, and she grabbed on to the door frame to support herself.“You are unwell, I fear, Mrs. Bertram!” she heard Mr. Gisborne say. “Pray, come inside, come inside.”

“I shall fetch you a glass of water,” added his wife. “Pray, sit here, ma’am. Fortunately, we still have the furniture which belongs to the house.”

Mary glanced furtively about her and perceived the remains of a household in disarray—cupboard doors hanging open, a few books and papers strewn about, dirty platters on the table, a child’s hoop and stick abandoned in a corner. Everything spoke of a hasty removal.

“Do you mean to say, ma’am—is it your understanding, then, that the Shelleys have no intention of returning?” said Mary faintly.

“I hardly know. I doubt it. And at any rate, you may know enough of Mr. Shelley to be aware of his predilection for revising his plans with very little notice. They were going to settle in Pisa, then they left Pisa, they were going to live with us in Livorno, but—”

“Shelley did not care for Livorno,” Mr. Gisborne interjected. “He did not think it interesting enough.”

“Here is some water. Plain boiled water, from the kettle. May I offer you my smelling salts, Mrs. Bertram? You are very pale. Are you indisposed? Is there anything else I can do for you?”

“No, no, nothing—nothing at all, I thank you. It is only the heat. Just permit me to rest for a moment.” Mary leaned her head against the wall behind her and closed her eyes. Out of the turmoil of her mind arose certain conviction—and despair.

Published on August 30, 2020 10:05

May 10, 2020

A Contrary Wind on sale this week in the US and UK

The first book of my Mansfield Trilogy is on sale this week for 99 cents. Just the thing to read to mom if she's a Jane Austen fan! (But that scene in Chapter 11 is a bit racy). In the USA and UK only, sorry. author.to/LonaManningauthor

The first book of my Mansfield Trilogy is on sale this week for 99 cents. Just the thing to read to mom if she's a Jane Austen fan! (But that scene in Chapter 11 is a bit racy). In the USA and UK only, sorry. author.to/LonaManningauthor

The best thing about the 1999 Mansfield Park movie was Lindsay Duncan in the dual role of Lady Bertram and her younger, less fortunately married sister, Frances Price.

Published on May 10, 2020 13:34

April 26, 2020

Tune in for an interview with me on Monday April 27th!

Every day I thank our collective lucky stars that we have the internet to help us through this pandemic. Just imagine what our lives would be without it. We're staying in touch with family and friends online, I teach English as a Second Language online, we hold meetings online, we divert ourselves online, shop online, and the list goes on and on.

One little diversion I could mention is that on Monday, April 27th, I'm interviewed on The Authors Show. Just scroll down for my name, the interview is being audio broadcast all day, I believe.

One little diversion I could mention is that on Monday, April 27th, I'm interviewed on The Authors Show. Just scroll down for my name, the interview is being audio broadcast all day, I believe.

Published on April 26, 2020 09:38

March 12, 2020

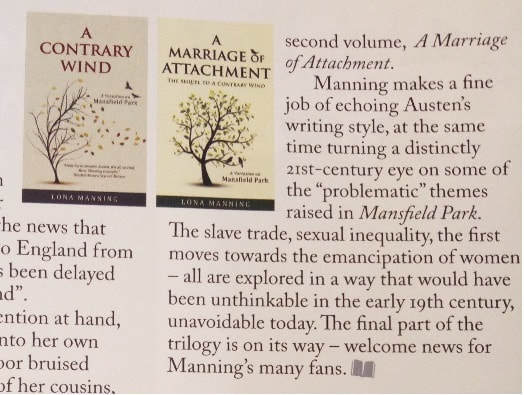

The Mansfield Trilogy reviewed in Jane Austen's Regency World Magazine

Published on March 12, 2020 13:59

March 1, 2020

On Health Care in China

New hospital in a third-tier City in Shandong, China This morning, while sipping my coffee and looking at my Twitter feed, I saw a much re-tweeted blog post that contained misinformation about health care in China. The writer was arguing that medical innovation does not arise out of a single-payer hospital system. Medicine and medical breakthroughs only come about in the robust environment of capitalism.

New hospital in a third-tier City in Shandong, China This morning, while sipping my coffee and looking at my Twitter feed, I saw a much re-tweeted blog post that contained misinformation about health care in China. The writer was arguing that medical innovation does not arise out of a single-payer hospital system. Medicine and medical breakthroughs only come about in the robust environment of capitalism.I could quibble, but I'm not going to argue about that. What I took exception to was the blog writer's portrayal of a Chinese hospital and Chinese medical care as squalid and dirty. Overall, that's a misleading picture.

First, China has prosperous provinces (the ones on the coast, the ones filled with factories and trade) and it has poorer provinces. Better health care is available in the more prosperous areas and in the bigger cities. That applies to us as well -- if you live in a dinky little small town, there is no giant gleaming hospital down the road, is there?

But they are building giant gleaming hospitals in China and perhaps you'd like a description of what happens when you go to one, as I did a number of times when I lived there.

But they are building giant gleaming hospitals in China and perhaps you'd like a description of what happens when you go to one, as I did a number of times when I lived there.Also, China abandoned communism a long time ago. Health care is not socialized. it's not free for everybody. When you go to the hospital, you register and pay some money and you get a smart card with your ID and your credits. Suppose you want to talk to a doctor. You then go to the relevant department and wait in the hallways until you get called into the consultation room.

The Chinese are, in my experience, more casual about the concept of medical privacy than we are in the West. Some other patient might come in to talk to the doctor while you're trying to talk to him. He slides your card through a little gadget attached to his computer and assigns the tests. Then you go line up in public to have you blood drawn; you are not whisked away to a little cubicle. You present your card again.

To get your blood results, you return in a few hours, insert that your hospital card into a machine, and it prints out your results. Then it's back to talk to the doctor, if necessary. Its all very brisk and efficient.

Take a number and give a blood sample at one of the stations

Take a number and give a blood sample at one of the stations  Consulting room

Consulting room  Station for taking blood samples

Station for taking blood samples  Getting blood test results I had the very great pleasure of teaching medical English to some doctors in China and I learned something of their lives. They do not enjoy the prestige and of course, nothing like the salaries, of their counterparts in the West. It was pretty routine, however, for a family to "tip" the surgeon with a substantial bribe before an operation in the hope that he or she would give their best efforts, or give them some lavish gift. So far as I could understand, the Chinese do not have a family doctor. In Canada, the GP is the gateway to specialists. If you want to see an arthritis specialist or a hearing specialist, you must be referred through your family doctor. Then you might wait for weeks or months. That is a single-user system. In terms of the facilities themselves, most of the hospitals and clinics I went to in China could stand comparison with the oldest parts of my local hospital in Canada (endless corridors, linoleum everywhere, that sort of thing) and the new hospitals could stand comparison with ours as well.

Getting blood test results I had the very great pleasure of teaching medical English to some doctors in China and I learned something of their lives. They do not enjoy the prestige and of course, nothing like the salaries, of their counterparts in the West. It was pretty routine, however, for a family to "tip" the surgeon with a substantial bribe before an operation in the hope that he or she would give their best efforts, or give them some lavish gift. So far as I could understand, the Chinese do not have a family doctor. In Canada, the GP is the gateway to specialists. If you want to see an arthritis specialist or a hearing specialist, you must be referred through your family doctor. Then you might wait for weeks or months. That is a single-user system. In terms of the facilities themselves, most of the hospitals and clinics I went to in China could stand comparison with the oldest parts of my local hospital in Canada (endless corridors, linoleum everywhere, that sort of thing) and the new hospitals could stand comparison with ours as well.But China is, on a per-capita basis, a much poorer country than the West, so yes, there are going to be clinics in rickety old buildings, and ancient-looking equipment. But China had advanced rapidly in economic terms, if not in terms of personal liberty.

My husband getting acupuncture treatment

My husband getting acupuncture treatment  Original hospital building founded by Western missionaries Some doctors study Western medicine, some study Chinese Traditional Medicine and some hospitals offer both kinds of treatments.

Original hospital building founded by Western missionaries Some doctors study Western medicine, some study Chinese Traditional Medicine and some hospitals offer both kinds of treatments.  A display of medicinal plants in a Traditional Chinese Medicine hospital At right: Traditional Chinese Medicines on display at a TCM hospital

A display of medicinal plants in a Traditional Chinese Medicine hospital At right: Traditional Chinese Medicines on display at a TCM hospital

Published on March 01, 2020 15:47