CMP#5 "Talking of rank, people of rank, and jealousy of rank"

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: The distinctions of rank should be preserved

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Click here for the first in the series. Implicit Values in Austen: The distinctions of rank should be preserved

In the previous blog post, I talked about the militia in Pride & Prejudice and disagreed with the idea that Austen used the militia to bring a menacing undertone to this light, bright and sparkling comedy.

In the previous blog post, I talked about the militia in Pride & Prejudice and disagreed with the idea that Austen used the militia to bring a menacing undertone to this light, bright and sparkling comedy. The main theme of Pride & Prejudice, Dr. Helena Kelly posits, is class warfare. It's the Jacobins versus Burke. This refers to an important conflict in English politics and society in reaction to the French Revolution which we'll refer to several times in this series.

At first, progressives in England greeted the French Revolution with excitement, hailing it as a new era in democracy, and one that they hoped would have an influence in reforming the United Kingdom. But when the Revolution was followed by the Terror, when innocent people were rounded up and guillotined, or set on rafts and drowned, there was a huge backlash in England. Government censors cracked down on radical writers like Thomas Paine.

In the cartoon at left, Paine is pulling the stays of Britannia. The joke is that Paine is destroying her constitution, a pun on the British constitution and the idea that wearing too-tight corsets was bad for women's health. Paine was originally a corset-maker by trade. He is wearing the red cap of liberty, a symbol of the revolution.

In my book A Different Kind of Woman, Fanny Price accidentally meets up with a large group of millworkers marching into Manchester for a big protest rally. She is quite uncomfortable when she see that some of them are carrying the red cap--with everything that it signifies--on a flagstaff.

Dr. Kelly thinks Austen would have been on the Jacobin side of the debate, despite the fact that (as Kelly notes) her cousin's husband was executed on the guillotine. Kelly sees Austen's satirical portrayal of Lady Catherine as an argument for overthowing the entire class system. Why else, Kelly asks, would Austen use the name "de Bourgh" for Lady Catherine and "Darcy" for the hero? Why use French-sounding names "if you don't want to bring up what happened in France--the abandoning of titles, the confiscation of estates, the guillotining?"

The reason de Bourgh and Darcy "sound and look French" is because the names of England's nobility derive from French (that is, Norman) names, due to the Norman conquest in 1066. Bertram, de Bourgh, Fitzwilliam, and Darcy are all Anglo-Norman names.

When Elizabeth and Mr. Wickham sit and gossip about Lady Catherine, Kelly calls it "a revolutionary moment" in a "revolutionary novel." Later, Elizabeth meets Lady Catherine, and is certainly not cowed by her.

"From the corner of our eyes," writes Kelly, "we can see the shadow of the guillotine."

"He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” Very well, Elizabeth is saucy to Lady Catherine. But she is saucy to everyone. Does this really mean she, or Austen, wants to see Lady Catherine's head on a pike? Or is it possible to be just a little more nuanced here?

"He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” Very well, Elizabeth is saucy to Lady Catherine. But she is saucy to everyone. Does this really mean she, or Austen, wants to see Lady Catherine's head on a pike? Or is it possible to be just a little more nuanced here? If Pride & Prejudice is intended as a rejection of social class, how about the important climactic moment when Lady Catherine confronts Elizabeth? When Lady Catherine says: “If you were sensible of your own good, you would not wish to quit the sphere in which you have been brought up.”

Does Elizabeth pump her fist in the air and exclaim, “Who cares if I am not his social equal? To hell with the class system! Viva la revolución, bitch!”

No, she doesn't. Elizabeth responds that she is of the same class as Mr. Darcy. Her father is a “gentleman.” That is, her father does not work and he lives off the income from his fields and his tenants. "So far we are equal."

And Lady Catherine concedes the point! “True. You are a gentleman’s daughter.” (And Bennet is also an Anglo-Norman name.) She follows that up with other objections, but the point is that Elizabeth defends herself to Lady Catherine by asserting her membership in the privileged class. This is a key exchange in the novel.

In their reviews of Jane Austen: the Secret Radical, YouTube vloggers Blatantly Bookish and Books and Things both point out that the real rebel in the story is Lydia, who runs off without getting married, while Elizabeth is embarrassed because her family can't behave properly. Elizabeth is mortified when Mr. Collins talks to Darcy at the Netherfield Ball, "without [an] introduction... it must belong to Mr. Darcy, the superior in consequence, to begin the acquaintance." Lady Catherine is not even the most ridiculous member of the privileged class in Austen. That honour goes to Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion. Here is one of those occasions when Austen breaks the fourth wall and tells us directly that Sir Walter is "a foolish, spendthrift baronet, who had not had principle or sense enough to maintain himself in the situation in which Providence had placed him." So the most offensive thing about Sir Walter Elliot is not that he was born a baronet, but that he has failed to live up to the responsibilities and duties incumbent upon him.

Likewise, Mary Crawford says of the wealthy Mr. Rushworth of Sotherton, "I often think of Mr. Rushworth's property and independence, and wish them in other hands." She does not say, "I often think the Rushworths should be kicked out and Sotherton should be broken up into a cooperative farming venture." Her complaint is that Mr. Rushworth is too stupid to be worthy of his position in life. The idea that people were born in their station in life, that God intended some people to be dukes and other people to be peasants was in fact the mainstream view in Austen's time. The hymn, "All Things Bright and Beautiful" speaks of: "The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, God made them high and lowly, And ordered their estate."

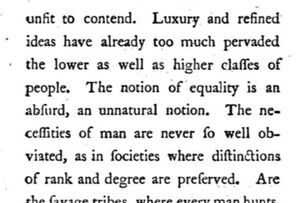

In the novel The Two Cousins, published in 1794, the wise mother Mrs. Leyster, who is the moral arbiter of the book, tells her daughter that "the notion of equality is an absurd, an unnatural notion. The necessities of man are never so well obviated, as in societies where distinctions of rank and degree are preserved."

In the novel The Two Cousins, published in 1794, the wise mother Mrs. Leyster, who is the moral arbiter of the book, tells her daughter that "the notion of equality is an absurd, an unnatural notion. The necessities of man are never so well obviated, as in societies where distinctions of rank and degree are preserved." A footnote was added to Mrs. Leyster's speech to point out that The Two Cousins was written during the backlash over the French Revolution. It appears that the author, Elizabeth Pinchard, felt she needed to explain or justify Mrs. Leyster's strict views as to rank.

Mrs. Leyster's speech reminds us of Mr. Collins: "Lady Catherine will not think the worse of you for being simply dressed. She likes to have the distinction of rank preserved.”

Mrs. Leyster's speech reminds us of Mr. Collins: "Lady Catherine will not think the worse of you for being simply dressed. She likes to have the distinction of rank preserved.” This is a dig both at Mr. Collins and at Lady Catherine, but is

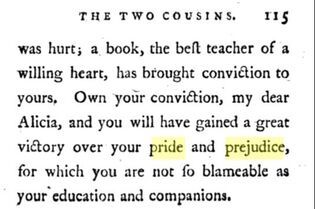

it a hint at class overthrow? Incidentally, the phrase "pride and prejudice" appears in The Two Cousins:

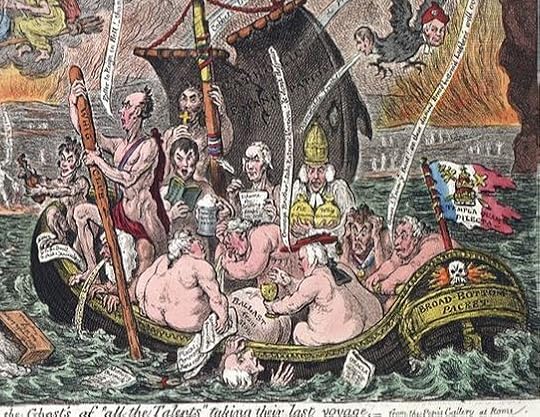

Recall that Dr. Kelly argues that Austen can only hint at her theme of class overthrow due to the repressive nature of her government and society. The same claim is made by the Extra Credits YouTube series, in "Jane Austen - Sarcasm and Subversion." But it would be a gross exaggeration to suggest that criticism of the high-born was prohibited in Austen's time, or that ladies especially could not write critically about society. Of course people gossiped about aristocrats and made fun of politicians and even high churchmen. James Gillray's cartoon, below, shows the aristocratic members of the British cabinet buck naked, except for the Bishop of London, who gets to keep his clothes on.

Recall that Dr. Kelly argues that Austen can only hint at her theme of class overthrow due to the repressive nature of her government and society. The same claim is made by the Extra Credits YouTube series, in "Jane Austen - Sarcasm and Subversion." But it would be a gross exaggeration to suggest that criticism of the high-born was prohibited in Austen's time, or that ladies especially could not write critically about society. Of course people gossiped about aristocrats and made fun of politicians and even high churchmen. James Gillray's cartoon, below, shows the aristocratic members of the British cabinet buck naked, except for the Bishop of London, who gets to keep his clothes on.  And of course other British novels contained unflattering portraits of the nobility. The corrupt nobleman attempting to ravish an innocent young virgin was a staple of the 18th century novel, (such as in Lydia: or Filial Piety, and Sir Charles Grandison) Returning to Jane Austen, it is true that she gives due credit to people who are not born gentlemen, like Elizabeth Bennet's uncle Gardner, who is a merchant.

And of course other British novels contained unflattering portraits of the nobility. The corrupt nobleman attempting to ravish an innocent young virgin was a staple of the 18th century novel, (such as in Lydia: or Filial Piety, and Sir Charles Grandison) Returning to Jane Austen, it is true that she gives due credit to people who are not born gentlemen, like Elizabeth Bennet's uncle Gardner, who is a merchant. Elizabeth "gloried in every expression, every sentence of her uncle, which marked his intelligence, his taste, or his good manners," as he speaks with Mr. Darcy. But her uncle doesn't talk to Darcy until Darcy asks to be introduced.

In Austen, vulgarity and ignorance are greater shortcomings than being poor or low-born, and those who are born into privilege have duties as well. Elizabeth's opinion of Darcy begins to change when she hears his housekeeper praise him. He fulfills all of his duties and responsibilities--to his sister, his servants, and his tenants.

And in the end, Elizabeth marries the rich, high-born guy with the French-sounding name. Next post: So what is the moral of Pride & Prejudice?

Published on September 19, 2020 21:23

No comments have been added yet.