Lona Manning's Blog, page 5

August 1, 2024

CMP#198 3 books that look under Austen's hood

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 198 Three books that look under Austen's hood

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 198 Three books that look under Austen's hood

Bing AI image Now, this is something I'm happy to see in Austen scholarship and I hope it becomes a trend--forget about books that explain how Austen held exactly the same views as a blue-haired tattooed humanities undergraduate in an Ivy League university. These three newly-published books return to the formal scholarship of studying the nuts and bolts of Jane Austen's writing and the artistic choices that impelled her. Is the "under the hood" metaphor unsuitable for Austen? How about embroidery? Turning over the embroidery and looking at the back side, then.

Bing AI image Now, this is something I'm happy to see in Austen scholarship and I hope it becomes a trend--forget about books that explain how Austen held exactly the same views as a blue-haired tattooed humanities undergraduate in an Ivy League university. These three newly-published books return to the formal scholarship of studying the nuts and bolts of Jane Austen's writing and the artistic choices that impelled her. Is the "under the hood" metaphor unsuitable for Austen? How about embroidery? Turning over the embroidery and looking at the back side, then. How does Austen do it? And how did she differ from her predecessors and contemporaries? Let's return to studying the text. And--this is what I am all about--study the text in the context of the literature of Austen's day. This will bring you rewarding realizations and will make it clear that Austen was very much engaged with what she read.

I think this kind of scholarship is just the sort of thing Janeites would enjoy...

Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction by Collins Hemingway

Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction by Collins Hemingway In Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in 'a Style Entirely New' (2024), Collins Hemingway draws on his background as a writer and his research into the literature of Austen's time to examine Austen's creative process. He explores "her development as a writer: what she adapted from tradition for her needs; what she learned novel to novel; how she used that learning in future works; and how her ultimate mastery of fiction changed the course of English literature."

Novels of the time relied on evil villains and perfect heroines and a great deal of coincidence. Austen used real, imperfect people whose actions drove the plot. “A good plot shows how people respond in real situations. Darcy’s rudeness to Elizabeth leads her to believe Wickham’s lies about Darcy’s past behavior. That belief triggers the major events of the first half of Pride and Prejudice. Lydia’s outsized personality and immaturity lead to her disgrace, which leads to Darcy’s largely hidden efforts to salvage the Bennet family honor. Austen’s other books operate on the same model. John Thorpe’s misunderstandings and lies; Marianne’s heedless pursuit of Willoughby; Emma’s inability to read romantic signals; Anne’s years-ago rejection of Wentworth: every behavior has a consequence to someone, and that consequence propels the story along.”

A key point is that "Jane Austen overcame the limitations of early fiction by pivoting from superficial adventures to the psychological studies that have defined the novel since. Her creativity and technique grew as she wrestled with pragmatic writing issues." Collins uses the metaphor of architecture; Austen as builder.

A fuller review is available here at Brenda Cox's website.

Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness by Inger Sigrun Bredkjær Brodey

Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness by Inger Sigrun Bredkjær Brodey “Jane Austen both spoofs and honours the traditional marriage plot.” Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness explores a question which I think preoccupies a lot of us Janeites--how does Austen write novels that manage to be romantic and ironic at the same time? Inger Sigrun Bredkjær Brodey recounts her teenage outrage when she first read Mansfield Park and got to the foreshortened, almost flippant ending. "Why? Why did she do this? Why develop everything so carefully only to rush the conclusion like that?" Even people who adore Jane Austen are sometimes bewildered by her succinct endings, this "let's get this wrapped up" vibe just when it's time for the big romantic clinch.

Brodey explains the special narrative techniques Austen uses in the conclusions to her novels. I found the textual analysis--let's call it the "how" of Austen's technique--especially informative and interesting, but Brodey also looks at the "why." In Jane Austen and the Price of Happiness. Both Brody and Collins Hemingway believe that Austen was impelled by her desire to reform the novel as an art form. This made her into an innovator. I quite agree.

I enjoyed Brodey's knowledgeable explanations of Austen's techniques. The meat of the book is her theory of why Austen chose to go the non-sentimental route. Austen never did anything by accident, or carelessly, and I know this is a question many people have wondered about.

What Jane Austen's Characters Read and Why by Susan Allen Ford

What Jane Austen's Characters Read and Why by Susan Allen FordMr. Collins never reads novels. He picks up Fordyce's Sermons to read to the Bennett sisters instead. Anne Elliot wistfully quotes poetry to herself. Fanny Price loves the poet Cowper. And of course novels are a major topic of conversation in Northanger Abbey. Austen's first readers would have been familiar with all these books and poems in a way that we aren't today. Few of us have read Lover's Vows, the play put on at Mansfield Park, or Fordyce's Sermons, but Susan Allen Ford has read everything that Austen's characters read and shows how Austen uses these allusions in her novels. Why, for example, did Austen choose Shakespeare's Henry VIII for Henry Crawford to read aloud instead of one of his better-known plays? Fanny is reading a history of the 1793 British embassy to China. Is she reading the version by Staunton, which devotes the first volume to the voyage getting there, and "includes foldout maps of the voyage that begins in Portsmouth, proceeds to Madeira and the Canary Islands, heads across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro for water, and then moves back across and south to round Africa and head toward China." No doubt Fanny would be thinking of the travels of her midshipman brother as she read this volume.

This book explores the different genres extant in Austen's time: the conduct, book, sentimental and gothic novels and not only places Austen's novels in context with these works, but explores how Austen related to and critiqued these works by her allusions to them. If you are ready for a deeper knowledge of Austen and her times, if you want to go into her novels with the some of the background knowledge her first readers had, if you want to learn more about the literary allusions lurking between the lines, you'll appreciate this book.

These books are for the serious Janeite. They draw on the scholarly knowledge of their authors, but are written in an accessible style. Collins Hemingway's book is priced for the academic market, but you might be able to persuade your local library or university library to order a copy.

These books are for the serious Janeite. They draw on the scholarly knowledge of their authors, but are written in an accessible style. Collins Hemingway's book is priced for the academic market, but you might be able to persuade your local library or university library to order a copy. It may sound insanely presumptuous to say that Collins Hemingway and I have an insight into Austen that comes from being fiction authors ourselves. Dear me, yes it does sound presumptuous. But if you've gone through the process of writing a novel, it's easier to approach a book from the point of view of an author, to ask yourself, "why is this scene written the way it is, with narration instead of dialogue? what is she doing with this character?". And even, "what is Austen doing with this passage? What would happen if you took the passage out?" That's all I am humbly claiming. No comparisons intended. An example from me is this blog post about Fanny Price and the East Room. Or this post about what happens when Jane Austen makes it rain. More about my books here.

More book reviews: Memoirs and meditations about Austen

And more: Three scholarly books about Austen

Previous post: Portrayals of gay people in novels of the long 18th century

Published on August 01, 2024 00:00

July 22, 2024

CMP#197 Portrayals of gay people

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 197 Portrayals of Gay People in Early Novels

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 197 Portrayals of Gay People in Early Novels

Sexual undercurrents in Rozema's 1999 Mansfield Park movie

In an earlier post

, I shared some strong feminist characters I had saved up from various novels to present all at once. This week, it's time for homosexuals to step up. Yes, they feature in some old novels.

Sexual undercurrents in Rozema's 1999 Mansfield Park movie

In an earlier post

, I shared some strong feminist characters I had saved up from various novels to present all at once. This week, it's time for homosexuals to step up. Yes, they feature in some old novels. The thing is, they didn't have a word for it back then, not in polite society, anyway. Yes, if you consult a Georgian slang dictionary, they had words for everything, but no words a well-bred lady or gentleman would use in company or even in print. The act, between men, was referred to as "the abominable vice" or the "unspeakable vice."

Given the reticence which prevailed around the subject, I am not someone who is driven to identify and tote up as many examples as possible or to declare that every strong-willed woman from Joan of Arc onwards and every unmarried man in an old novel must be gay. My aim is to give you some actual examples of how homosexuality was depicted in novels read by young ladies. Frankly, some 18th-century habits and expressions strike us differently today and I think some people are misinterpreting behaviour that was normal between the sexes back then. Mr. Elton walks arm-in-arm with Mr. Cole in Emma, and Sir Walter walked arm in arm with his heir, W.W. Elliot, in Persuasion. One modern scholar looks at the affectionate loyalty Emma has toward Miss Taylor/Mrs. Weston and concludes their relationship had a sexual component. As for Harriet, "her beauty happened to be of a sort which Emma particularly admired" and this is enough for some moderns to conclude that there's an erotic attraction there--Emma likes girls. How was Emma supposed to react to a pretty girl? With jealousy? Is that the only natural and authentic reaction they think girls have toward another beautiful girl? I mean, what are the options here?

Are they or aren't they?

Are they or aren't they?Let's remember that this was a society that was much more segregated by sex than ours. Whether or not people have a natural propensity toward same-sex activity, things happen in same-sex boarding schools, which might not recur in adult life. Same-sex friendships might have a greater intensity. Men and women raised so differently and kept apart in their growing-up years might find they have much less in common with each other, than with their same sex friends. That's just the way things go in sex-segregated societies. Herewith some ambiguous examples:

"I am not a young romantic girl, to fall in love, or commence violent friendships at first sight,” says Lady Susan of female friendship in Ellen and Julia. So does expressing love or strong same-sex friendship include an erotic dimension? Perhaps it does.

Pharos No. 26 (1787) by Laetitia-Matilda Hawkins, is a short essay-epistle, of the type that was popular back in the 18th century. It is written in the character of "Arabella Single" who is unhappy because although she enjoys “all the ease, the luxury, and the liberty that the beloved and only daughter of a gentleman, descended from an ancient family, and blessed with a plentiful estate can look for," she wishes she “could change [her] situation with some one much my inferior.”

Her parents brought her up and educated her with a view to the "rapid acquisition of every accomplishment, and by all other possible means, to facilitate their design of marrying me to some one of the many wealthy gentlemen in our country.” She hates “shewn like a puppy dog” and “exposed like a wild beast."

Arabella had one "female friend who occupied every softer sensation of my soul… I could have rested contented where I was.” Hmmm. what is she saying here? That her friend satisfied her intellectually and emotionally, so that's all she needed, or is the author hinting at something more?

The collection of essays called Pharos is attributed erroneously on the internet to favourite of this blog, Eliza Kirkham Strong, (later Eliza Kirkham Mathews), my candidate (bless her heart) for worst poet of the Regency. Below is one of her early sonnets, dedicated to a female friend. The references to "thrilling bliss" and "sacred fire" that "dart[s] thro my soul" and "ecstatic transports" might lead to only one conclusion in modern times, and it gives a new connotation to tuning one's lyre. But the "sacred fire" is "more chaste than Alpine snow," so who knows...

"Comedy unveiling to Mrs Cowley," by James Heath, British Museum Sonnet: Inscribed to Miss N-T-E

"Comedy unveiling to Mrs Cowley," by James Heath, British Museum Sonnet: Inscribed to Miss N-T-ESWEET is the fragrant breath of early Spring!

Sweet is the winding of the mellow horn!

Sweet is the woodlark’s chaunt in summer morn!

But sweeter far, the thrilling bliss I sing,

O! gratitude! To thee I tune my lyre!

Soft flows the strain, wak’d by thy magic skill,

Raptur’d I touch the chord, thy praise to trill,

Enchanting nymph! I feel thy sacred fire

Dart thro’ my soul, more chaste than Alpine snow,

Ecstatic transports kindle in my breast,

And e’en my soul, with thy bright name’s imprest;

Nor can hoar time’s keen scythe the blossoms mow,

OF GRACIOUS GRATITUDE, in heav’n they’ll bloom,

When death’s empoison’d dart hath struck me to the tomb. "Sooooo gay"

Last summer, the Evening Standard asked popular Austen scholar John Mullan about the TV series Sanditon and how it related to the brief fragment titled Sanditon that Austen left unfinished in her final illness. "'The TV Sanditon no longer has anything whatsoever to do with Austen,' said Professor Mullan... 'Andrew Davies really is veering off piste'... noting a new romantic sub-plot that involves a Duke who is gay. “Jane Austen is the most hetero-normative of novelists,' said Mullan, 'there were, of course, posh men who were gay in the Regency period, but not in Austen’s novels or, indeed, her letters.'"

Mullan was challenged on Twitter: "Oh come on! Tom Bertram [in Mansfield Park] is soooo gay.

Possibly, but Austen isn't explicit about it.

And Austen joked about James I and Robert Carr when she was a teen. She had brothers in the navy!!!"

Sure, she knew what homosexuality was--that's not the question. The question is, did she create gay characters?

Let's look at some examples of how a "soooo gay" character was described in a novel of the long 18th-century below.

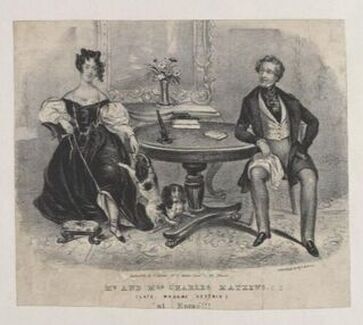

Edwin as Bob in the Man Milliner The man-milliner

Edwin as Bob in the Man Milliner The man-millinerThis first passage is well-known; it is from Frances Burney's Evelina: "At the milliners... we were more frequently served by men than by women; and such men! so finical, so affected! they seemed to understand every part of a woman’s dress better than we do ourselves; and they recommended caps and ribbands with an air of so much importance, that I wished to ask them how long they had left off wearing them."

"Man-milliner" became a euphemism for an effeminate man. In the 1787 play The Man-Milliner, a boy is intended to be apprenticed to an apothecary but is apprenticed to a milliner instead. Hilarity ensues, I suppose, I haven't read the play.

In a section about neighbourhood gossips talking about the titular heroine in Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1786), Anna is--as is usual for foundling heroines--wrongly suspected of being of easy virtue. A gossiping femboy spreads the rumour: “a very pretty, delicate young man, designed by nature for a retailer of gauze, but jumbled by chance into a brandy merchant, as he was called, assured the ladies, in the softest lisping tone imaginable, that he was certain she had been in high life…”

Devoted gal pal Black Rock House's effeminate officer

Devoted gal pal Black Rock House's effeminate officer I wrote about Black Rock House here. Mr. Silvertop is not essential to the plot, he is brought on for comic interest. "Mr. Silvertop was another officer [friendly with Gertrude’s worthless husband]. Nothing could be more analogous than the name to the man; --he was finical to a fault, precisely neat, and far more fitted to be a milliner in Paris, than to meet the enemies of Old England in the field of battle! His conversation was of the most puerile and trifling kind; he could descant on the alteration in the cut of a coat… half the day was generally employed in beautifying his hand and polishing his conical nails… “He was infinitely ingenious in making charades, and in netting work-bags; he could assist at a lady’s toilette, and was initiated in the arcana of her wardrobe... He wished to be thought a lady’s man; and while his brother officers were engaged in manly pursuits and athletic amusements, he liked to place himself in a circle of females, to arrange their music, to wind their cotton, to hold their thread on his wrists, as they wound it into balls, sometimes amusing them with an amorous melting sonnet of his own composition, or racking his brains to solve a conundrum with which his fair companions had tasked him.” "The sex of His Lordship's soul"

I've seen some mild ribbing of gay men and women in these early novels, like the brief excerpts above, and you can tell from this Regency cartoon that dandies and fops were not invisible in the popular culture, but I've never seen anything like this passage from Volume One of Modern Character s (1808) by Edward Montague. The narrator is describing one of the nobleman who make overtures to Emily Henderson, a girl who was seduced and abandoned and who becomes a courtesan to support herself and her children. The reference to a "female" soul predates modern thinking about gender and sex being two different things by over two hundred years:

"Lord Fopley is the generalissimo of the female part of the male creation… no person, on viewing his toilette, could possibly conclude that it belonged to a man: there rouge boxes, patches, washes and unctuous compositions, for softening the skin and removing freckles, powder to erase superfluous hair, cream of roses, and all the whole magazine of essences are displayed to view… His Lordship’s most favorite amusement is painting screens, bunches of flowers, groups of shells, ornamenting patch boxes, inventing fashions for ladies, and in decorating his own sweet person.

"Lord Fopley is the generalissimo of the female part of the male creation… no person, on viewing his toilette, could possibly conclude that it belonged to a man: there rouge boxes, patches, washes and unctuous compositions, for softening the skin and removing freckles, powder to erase superfluous hair, cream of roses, and all the whole magazine of essences are displayed to view… His Lordship’s most favorite amusement is painting screens, bunches of flowers, groups of shells, ornamenting patch boxes, inventing fashions for ladies, and in decorating his own sweet person."Perhaps the reader will wonder that, with all those pretty female amusements, his Lordship should think of such a manly one as that of keeping a Lady, but it was only for outward show that he did it for it is not recollected that any virgin ever accused his Lordship of attempting her innocence…

"No; it is, therefore, concluded that some mistake was made in the sex of his Lordship’s soul—if souls are sexual, and that a female one was inserted in his Right Honourable male form; therefore, as the soul guides the senses in all their various appetites and desires, his Lordship’s soul could have no wish of sleeping with a soul of his own gender… when Lord Fopley, under a promise of secrecy, condescended to explain certain matters, Emily found no difficulty in assenting to his request... Emily certainly had no complaint to make of his Lordship’s ever attempting to deviate from his private promise..." Rears and vices

So as you can see, some authors did depict gay characters--contemptuously, teasingly, comically, or with a hint of sympathy. Austen never went near that sort of thing in my opinion.

Oh-ho, but what about Mary Crawford's sodomy joke in Mansfield Park? Wasn't that a bold thing to do? Truthfully, I don't see how, given the times and the context, it could be a sodomy joke. But I can't suggest a different interpretation at this point.

More about "rears" and "vices" and Jane Austen's sailor brothers in this informative article by Seth LeJacq.

In an earlier post, I mentioned a novel with a female poet whose adoring female friend thought she was "quite a model for the bust of Sappho." There's also the mannish female character, the Amazon.

Published on July 22, 2024 00:00

July 18, 2024

CMP#196 My guest blog post at Quill Ink

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#196 Blessed Be Her Shade Thanks to Christina Angel Boyd for inviting me to contribute a guest blog post, which she has posted to commemorate the anniversary of Jane Austen's death. The post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#196 Blessed Be Her Shade Thanks to Christina Angel Boyd for inviting me to contribute a guest blog post, which she has posted to commemorate the anniversary of Jane Austen's death. The post is here. Prior thoughts at this blog for the anniversary of Austen's death are here and also here.

Jane lies in Winchester, blessed be her shade!

Jane lies in Winchester, blessed be her shade!Praise the Lord for making her, and her for all she made.

And while the stones of Winchester—or Milsom Street—remain,

Glory, Love, and Honour unto England's Jane!

-- Rudyard Kipling

Published on July 18, 2024 00:00

July 11, 2024

CMP#195 Subversive feminism in early novels

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#195 Subversive Feminism in Early Novels

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#195 Subversive Feminism in Early Novels

Very often, when reading old novels, I come across some striking passage when the author or authoress, or one of their characters, delivers their strong views about something, such as slavery or empire or women's rights. I've long since realized that Jane Austen was not outspoken about any of these issues, compared to her peers. I conclude that people who think she was outspoken or radical have not read enough of the popular literature of the time to have a basis for comparison.

Very often, when reading old novels, I come across some striking passage when the author or authoress, or one of their characters, delivers their strong views about something, such as slavery or empire or women's rights. I've long since realized that Jane Austen was not outspoken about any of these issues, compared to her peers. I conclude that people who think she was outspoken or radical have not read enough of the popular literature of the time to have a basis for comparison. But if I bang on that drum every time I review an old novel, I'll sound like a broken record. (ooh, mixed metaphors). So I've excerpted these three examples about feminism from novels I've recently read, to present them together. The first two are examples of feminists--okay, tragic, doomed, feminists, but they are given the chance to have their say. The third is a speech from a "mixed character," someone presented as flawed, but essentially good.

The feminist message is delivered not by the heroine, but by a side character. Then it is made clear to us that this side character may be sympathetic, but is not entirely admirable.

The word "subversive" is widely used in academia these days, often when arguing that the author has a message which she barely hints at, but i think introducing feminism in this way is truly subversive...

Bing AI Image "[A]n impassioned advocate of female rights"

Bing AI Image "[A]n impassioned advocate of female rights"Cecily Fitz-Owen, or, a Sketch of Modern Manners (1805), discussed here. Scholars of feminism in novels will be most interested in an acquaintance of Mr. and Mrs. Delamere who are the mentors of the heroine. Mrs. Maria Arnold is an intelligent, attractive and outspoken woman. Too outspoken perhaps? Mrs. Delamere murmurs: “Her talents are brilliant, her knowledge extensive; but does she possess the genuine graces of the feminine character. It may be, that I shrink before superior merit; but boldness of assertion, a commanding and decisive tone, repel my feelings.”

We learn Mrs. Arnold’s backstory through the device of a lengthy letter. Brought up by a stern father and a cruel step-mother, married off against her will to a rich man who repulses her, she turned to education to give meaning and purpose to her life: “I gradually drew a little band of learned men around me, and the career of my mental improvement was rapid and brilliant... [W]hat philosophy could be more congenial than that which pointed out to me the rights and injuries of my sex; first, slaves to those with whom they are connected by the ties of nature, to harsh fathers and unfeeling brothers, and then in turn, to connections, which the habits of society have forced on them, without power of dissolution! Myself the victim of successive slaveries—freedom became the object of my idolatry. I wished the blessing confined neither to country, age, nor sex; and commenced an impassioned advocate of female rights. Three years ago, my little Anna, my only child, was born… I rejoiced that I had not given birth to a son, who, I knew would have been brought up to all the follies and prejudices of rank. Whilst a daughter would be committed, exclusively to her mother’s care…. My child… shall never know what it is to be the slave, either of a parent or a husband… to my father, my husband, who have successively destroyed the happiness of my life, I owe nothing; and the opinions of a malignant ill-judging world sink into insignificance, when put in competition with the satisfaction to be derived from the society of a tender and beloved friend…”

She escapes to the continent with her lover. Her husband will not grant her a divorce.

The Delameres conclude that although Mrs. Arnold is much to be pitied, and that women ought to have the means of divorcing their husbands in outstanding circumstances, she will end up unhappy and remorseful.

Considering that this book was published six years after William Godwin ruined Mary Wollstonecraft's reputation with his memoir of her, (a period during which no respectable woman had a good word for her) this is a pretty strong and sympathetic portrait of a Wollstonecraft-like figure. The author still supports the strict prevailing moral code, but does not deny the cruelties and injustice faced by women.

Madwoman on the cliff --"as if the soul were sexual"

Madwoman on the cliff --"as if the soul were sexual"What Has Been (1801), discussed here, is a typical sentimental novel with a beleaguered heroine, but Eliza Kirkham Mathews works in a little feminism and an explicit anti-slavery message not directly connected to the plot. In Volume I, we meet an eccentric woman, dressed in black, haunting the Teignmouth Cliffs. She is Agatha, the half-crazed abandoned mistress.

Emily the poverty-stricken orphaned heroine cherishes a hopeless love for Frederick who also has no money. Emily is soliloquizing on the beach and is joined by Frederick, when they are interrupted “by the sudden appearance of a woman who issued from a small cavern in the cliffs."

"Her figure was tall and thin, her complexion sallow, her eyes black and penetrating. She approached with a solemn and steady step, and in a voice full, awful, and commanding, she thus addressed Emily: 'But where, in all created Nature, is there a being so weak, defenceless, unprotected, and oppressed as woman? Even in the earliest days of childhood, her mind is enervated by the imbecile education which the folly of custom bestows on her. Her understanding is narrowed by the prejudices which the unthinking preceptress instills into her plastic mind; she is early taught to respect the dignity of man (as if the soul were sexual) to look up to him as a being of a superior order, whose decisions are just, whose judgment is infallible, but she is a woman, and therefore a slave!'”

Agatha then relates her own backstory of how she was seduced and abandoned. “Thus saying, she clasped her hands, in frantic agony, and ran swiftly up the cliff.”

More about the author, Eliza Kirkham Mathews, here.

Courtesy British Museum Ellinor (1798) -- a "champion for the rights of women"

Courtesy British Museum Ellinor (1798) -- a "champion for the rights of women"Lady John Dareall is an Amazon, a stock character of the sentimental novel. Amazons loved horses and hunting, could jump a five barred gate, liked to wear riding habits all the time, spoke loudly and took no guff from anybody. Usually they are figures of ridicule but Lady John, who becomes Duchess Dreadnaught later in the book, acts as a second mother to the heroine. After a masked ball, she regales the titular heroine of Ellinor (discussed here) with a long speech:

“I have, from the time I threw off my frock [at age 16], stood up a champion for the rights of women; have boldly thrown down my gauntlet to support their equality, immunities, and privileges, mental and corporeal, against the encroachments of their masculine tyrants.

“I commiserate the infirmities of my sex, who, with susceptible hearts, and minds enervated by an education calculated to debilitate both the corporeal and mental system, they look not into themselves for support, but lean on men, whose vaunted strength arises from their weakness. Did we make greater exertions, and call into action those powers entrusted to us by the Creator of the universe, we should find that he has distributed his gifts nearly equal between the sexes.

“It is so evidently the interest of these self-created lords of the universe, to maintain their usurped authority, which is only to be done by pretending to admire in women those qualities for which they ought to feel contempt; ignorant imbecility, which they soften down under the denomination of a feminine delicacy; that is, to tremble at a breeze, weep over a novel, and faint with ecstasy at the unnatural note of an opera singer; whose mind is too debilitated to enter into an argument with her husband, by which she acquires the character of the milder virtues, because she prefers the joys of lassitude to any triumph that might be gained by exertion.”

“It is so evidently the interest of these self-created lords of the universe, to maintain their usurped authority, which is only to be done by pretending to admire in women those qualities for which they ought to feel contempt; ignorant imbecility, which they soften down under the denomination of a feminine delicacy; that is, to tremble at a breeze, weep over a novel, and faint with ecstasy at the unnatural note of an opera singer; whose mind is too debilitated to enter into an argument with her husband, by which she acquires the character of the milder virtues, because she prefers the joys of lassitude to any triumph that might be gained by exertion.”But wait! She's not done! Now she's going to complain about female education: "“Let us examine what are their real acquirements; they are to totter a minuet, rattle the keys of a piano forte, twang the strings of a harp, scream an Italian song, daub a work-basket, or make a fillagree tea-caddie; they are just able to decipher a letter of intrigue, and scrawl an answer; have French enough to enable them to read by the help of a dictionary, La Nouvelle Heloise, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Les Malheurs de l'inconstance,, and the Chevalier Faublas. [That is, naughty French novels they shouldn't be reading]. Of the authors of their own country, of its history, ancient and modern, of its laws or policy, they know as little as a native of Kamschatka…"

An inspiring speech, but perhaps the timing left something to be desired. Ellinor just fended off a nobleman who attempted to sexually assault her in the summerhouse, and then she was publicly blamed and shamed for the whole thing.

This novel provides several examples of men who are called to account socially for exploiting powerless women, at a time when in many novels, perhaps most, the predatory nobleman gets away scot-free.

A parting shot: Lady Dareall declares that: "There are very few arts and sciences that women are not capable of acquiring, were they educated with the same advantages as men."

"I always stand up for women"

"I always stand up for women"So what is Austen's most explicit feminist statement? I don't think it's Anne Elliot's factual remark that "the pen has been in their hands," (i.e. the hands of men) because she precedes that with heartfelt sympathy for the hardships faced by men. "You are always labouring and toiling, exposed to every risk and hardship. Your home, country, friends, all quitted. Neither time, nor health, nor life, to be called your own." Then she postulates that men and women are essentially different in their natures. "It would be hard, indeed” (with a faltering voice), “if woman’s feelings were to be added to all this.”

No, Austen's most outspoken feminist is Mrs. Elton. She takes Mr. Weston to task for opening his wife's letter: "I must protest against that.—A most dangerous precedent indeed!—Upon my word, if this is what I am to expect, we married women must begin to exert ourselves!" After Mr. Weston, speaking of the redoubtable (and powerful) Mrs. Churchill, says: "Certainly, delicate ladies have very extraordinary constitutions, Mrs. Elton. You must grant me that.” She responds: “No, indeed, I shall grant you nothing. I always take the part of my own sex. I do indeed. I give you notice—You will find me a formidable antagonist on that point. I always stand up for women."

Feminist runner-up is Lady Catherine De Bourgh, who observed: "I see no occasion for entailing estates from the female line." Previous post: Ellinor, whose beauty is her curse

Published on July 11, 2024 00:00

July 5, 2024

CMP#194 Ellinor, whose beauty is her curse

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 194 Ellinor, or the World As It Is (1798), by Mary Ann Hanway

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP# 194 Ellinor, or the World As It Is (1798), by Mary Ann Hanway

Apart from a brief note at the beginning of Northanger Abbey, Austen--unlike other novelists of her era--did not write prefaces for her novels. Author Mary Ann Hanway came out swinging against the gothic novel in her preface to Ellinor, “having been long convinced that the most baneful consequences must result to the rising generation, from reading the monstrous productions that for some years past have issued from the press [involving} 'valorous knights,' 'goblins dire,' 'charnel-houses.'" She promised that her novel would reflect “nature as it is," that is, she advocated for a more probable and realistic novel plots. Let's see how she succeeds!

Apart from a brief note at the beginning of Northanger Abbey, Austen--unlike other novelists of her era--did not write prefaces for her novels. Author Mary Ann Hanway came out swinging against the gothic novel in her preface to Ellinor, “having been long convinced that the most baneful consequences must result to the rising generation, from reading the monstrous productions that for some years past have issued from the press [involving} 'valorous knights,' 'goblins dire,' 'charnel-houses.'" She promised that her novel would reflect “nature as it is," that is, she advocated for a more probable and realistic novel plots. Let's see how she succeeds!Ellinor is a “picture of perfection” heroine but not an obnoxious one. She faces malicious slanders but holds on to her dignity and always hopes for better days. Janeites might spot some interesting similarities in the synopsis…

Ellinor opens with our heroine sitting in a carriage, on the final leg of her journey back from a convent in Paris. She has no idea who her parents are. Every now and then a forbiddingly cold woman visits her, and on this occasion, since Ellinor has refused to convert from Catholicism and take the veil, the mysterious woman sends her to be a companion to a young lady in the home of the gentlemanly Sir James Lavington.

Sitting in the carriage with Elinor is Mr. Howard, an older man—we’re talking an Emma/Mr. Knightley age gap here. She tells him her backstory. He is absolutely smitten and can’t stop thinking about her, but he is not rich, and his gouty old uncle will never let him marry a portionless girl of unknown background.

Bing AI image A lamb amongst society's wolves

Bing AI image A lamb amongst society's wolvesEllinor is placed in Sir James Lavington's family, and for a while—surprise! Everything goes well. Ellinor improves the sulky Augusta’s character, and “by perseverance, and her judicious choice of them, had induced her first to listen to, and then by an easy and almost imperceptible transition, to become fond of reading, as an amusement.”

Ellinor’s beauty is her curse. Because she has no male relatives and is unprotected, Ellinor is terribly liable to being insulted, ie, men want to make her their mistress. She fends off the very determined dishonourable advances of Colonel Campley. More trouble comes in the person of Lady Fanny Flutter, who spreads gossip and trouble.

Between the insinuations that she was encouraging Campley's attentions and her vague background, Ellinor is gossiped right out of the neighbourhood: Perhaps she is the “product of an illicit intercourse between a parson and his housekeeper, or some stale virgin and her favourite footman.”

Meanwhile Mr. Howard is stuck overseas in a healthful climate with his gouty old uncle, so he’s unable to play a part in the novel but even if he were there, propriety would prevent him from giving Ellinor any shelter or financial assistance. She comes darn close to having to find a job to support herself, but she is taken in by a kindly noblewoman who doesn’t give two figs what the rest of the gossiping world says. More on Lady Dareall coming up in a blog post about early feminists. “to esteem the person we don’t love, and to love the person we cannot esteem."

Ellinor finally learns who her parents are, thanks to a guilty conscience, a manuscript and a coincidental reunion. I'm not going to give a complete synopsis but if you want more detail, you can read this contemporary review. She is illegitimate, the fruit of a single night of passion between two lovers who were parted by tyrannical parents. And she has already met her dad and fortunately (whew!) there was no incest tease. Not to speak of, anyway. And now she has an inheritance from her mother. And Mr. Howard is back from Italy with his uncle’s inheritance.

Ellinor chooses Mr. Howard even though she does not feel passion for him, turning down Lady Dareall's son, a handsome, rich, nobleman. When she was a poor nobody, he asked her to be his mistress--and that insult ruined his chances with her forever.

Features of interest for JaneitesThe ton is surprised that Ellinor, "young, handsome, accomplished, and rich," marries an older man.The term “caro sposo” is used six times, and each time it’s used ironically.The scheming Lady Fanny, who left her booby of a husband to go with the lady-killer Campley, learns to her outrage that he will bed her but not wed her.When speaking of some dispossessed peasants from the time of William the Conqueror, the narrator remarks: “The world is not their friend, nor the world’s law!"Hanway is scathing in her caricatured portrayal of the gossipy spinster Letitia Liptrap who, even though she is not poor, is referred to as a frightful tabby, a “frozen piece of chastity”, of “cadaverous countenance” and a “mouldy spinster”.

Features of interest for JaneitesThe ton is surprised that Ellinor, "young, handsome, accomplished, and rich," marries an older man.The term “caro sposo” is used six times, and each time it’s used ironically.The scheming Lady Fanny, who left her booby of a husband to go with the lady-killer Campley, learns to her outrage that he will bed her but not wed her.When speaking of some dispossessed peasants from the time of William the Conqueror, the narrator remarks: “The world is not their friend, nor the world’s law!"Hanway is scathing in her caricatured portrayal of the gossipy spinster Letitia Liptrap who, even though she is not poor, is referred to as a frightful tabby, a “frozen piece of chastity”, of “cadaverous countenance” and a “mouldy spinster”.

Harriet Byron's rescue in Sir Charles Grandison Meta-narration and putting down novels

Harriet Byron's rescue in Sir Charles Grandison Meta-narration and putting down novels While they travel by carriage to London, the narrator remarks: “We grieve that the misadventures which are so constantly occurring to the heroines of contemporary novelists, did not happen to ours, that we might have been enabled to oblige our young readers with a chapter of the marvelous.”

Yet, during a different carriage ride, the heroine is nearly abducted by the persistent Sir Charles Campley!

More novel-slagging: Lady Fanny's maid, Miss Homely, “had read every novel that had been produced in the last ten years, good, bad, and indifferent; those, assisted by her propensities, had made her a perfect adept in intrigue.”

About the author/reviews

Mary Ann Hanway was a friend of Jane Porter, one of the two forgotten female authors whom Devoney Looser has brought back into the spotlight. Hanway lived in Blackheath, London but appears to have some Scottish connections. Her other novels are Falconbridge Abbey, Christabelle, The Maid of Rouen. According to the invaluable The Feminist Companion to Literature in English, Hanway favoured the emancipation of blacks and better civil rights for Catholics.

Ellinor got a good review from the Anti-Jacobin Review, a publication pushing back against those dangerous French Revolutionary ideas, so the conservative anti-Jacobins were not too bothered by the pro-peasant and feminist views. The review includes, as they often did in those days, a complete summary with spoilers. The Analytical Review mixed praise ("a lively manner") with snark: "A beautiful and accomplished female foundling, thrown upon the world... with heaven taught excellencies and qualities, exciting the envy and malice of one sex, and the passions and admiration of the other, led through various vicissitudes to the discovery of rich and honourable parents, ultimately triumphing over her enemies—is in the beaten track of novelists." The reviewer notices that Hanway followed the novelistic convention that Ellinor's "beauty, elegance, and virtue" stamps her as being of noble rank, yet Hanway included many populist comments that "bespeak the writer… an advocate on the side of democracy." The reviewer liked Lady John Dareall, an intrepid champion for female rights (who will be excerpted in a future post).

"The purpose, which the author professes to have in view… is 'to convince the patient sufferers of undeserved persecution, that truth, honour, rectitude and virtue, will decidedly triumph... However well intended... a few steps into the world must teach the most careless observer, that the deductions are evidently false."

The Critical Review allowed: “It would be well if the circulating libraries contained no worse books than Ellinor.”

Previous post: Ellen and Julia, a tale of two sisters

Published on July 05, 2024 00:00

June 27, 2024

CMP#193 Ellen and Julia, the sister heroines

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here.

Bing AI image CMP#193 The "novel-reading miss": Ellen and Julia (1793)

Bing AI image CMP#193 The "novel-reading miss": Ellen and Julia (1793) The next few books, I think, all mention novel-reading, if only in passing. In her famous defense of the novel in Northanger Abbey, Austen wrote of the novelists who disparage novels in the pages of their own novels, "joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust."

Here is a prime example: Sensible Julia “selected such books only as could improve, and admired no characters, but such as placed virtue in its most amiable light, and was equally free from the absurdities of romance, or the pernicious follies delineated in modern Novels." Her sister Ellen grows up reading novels and wants to be a romantic heroine.

That's a big reason why I am reading and sharing information about these forgotten books--the fun of connecting them to Austen and placing Austen's works in the context of the time they were written. Scholar Susan Allen Ford, speaking on the Jane Austen Society podcast, speaks of the pleasure of finding relevant items in other novels: "I was always making little discoveries... They certainly give you an insight into Austen's playful mind... You can read Austen forever without knowing any of this, but once you do, it just adds these extra layers of complexity but also extra layers of pleasure."

Ellen and Julia is a novel full of unrealistic coincidences and several incredibly fortunate inheritances, but the message of the novel is supposedly: beware of the insidious effects of novel-reading, or you’ll end up like Ellen!

The novel is typical in that a slender narrative is stretched out with unconnected and lengthy backstories--in this case, the backstories of fairly minor characters. I guess they were regarded as bonus short stories included with the novel. And of course, these backstories have a moral purpose, illustrating some fault or vice and the miserable consequences thereof... Welcome to Cumberland, enjoy your exile

The first forty pages of Ellen and Julia give the backstory of Mr. and Mrs. Woodville, the parents of the sisters. Mr. Woodville was a wealthy young man who squandered his estate in gambling. Bitter and poor, he retires to a remote home in the north of England, to recoup what income he can for his two daughters, the beautiful but moody Ellen and the sweet-tempered Julia. (Ellen quite understandably, is annoyed about being a lovely teen-aged girl having to live in complete isolation in the countryside.)

While ambling around a nearby abandoned Abbey, the girls discover a tunnel leading to a secret underground apartment, where they find a genteel woman on her deathbed. Mrs. Danvers fled, just like their father, to this remote spot to atone for her wrongdoings. Mr. Woodville’s backstory warned against being careless with money; Mrs. Danvers warns about frivolity and infidelity. She has hidden underground ever since, dying of remorse and (presumably) Vitamin D deficiency. Upon her death, the Woodvilles contact the local curate, Charles Evelyn, who is the first young gentleman either girl has ever seen or spoken to. He's handsome, intelligent, courteous, and poor.

Shortly afterwards, Mr. Woodville suddenly commits suicide. His death releases his long-suffering widow and daughters from living in the middle of nowhere. They first travel to the family mansion which Mr. Woodville had leased out, to make arrangements for handing it over to the next male heir. The estate, apart from a reasonable cash inheritance for the girls, goes to Lord A-- (that's how his name is given in the book) who (small world!) is the same Lord A— who deprived Charles Evelyn of a long-promised clerical living. That's why Charles is stuck in the back of beyond, serving two remote parishes for a pittance and barely able to support his widowed mother.

Ellen, understandably, is ecstatic about the prospect of being seen and admired in society: “she already anticipated conquests, adventures, duels, and many other strange and unnatural events, such as are too often retailed in those dangerous publications [novels], that poison the minds of young inexperienced girls, and embitter their future days.”

Charles Evelyn listening to Mr. Hammond's lengthy backstory. Bing AI Image Middle-aged Man sneaks around with naive girl

Charles Evelyn listening to Mr. Hammond's lengthy backstory. Bing AI Image Middle-aged Man sneaks around with naive girlLord A— is a rake and the unsophisticated Ellen is a sitting duck for him. She falls for his "love-can’t-survive-the-shackles-of-marriage" ploy and they run off to Paris.

Mrs. Woodville and Julia chase after them but make it no farther than London where Mrs. Woodville falls ill with shock and horror. An acquaintance of Lord A—, young Lord Meanwell (yes really) and his sister Lady Susan befriend the stricken pair. Lord Meanwell’s housekeeper Mrs. Norris kindly finds them respectable lodgings. When Mrs. Woodville dies of a broken heart, Julia goes to live with Lady Susan. Lady Susan, while attractive, widowed, and witty, is a genuinely decent person; she's not like Austen’s Lady Susan.

Meanwhile, back in nowheresville, Charles Evelyn stumbles across another (our third!) repentant hermit who fled to the same neighbourhood to atone for his wrong-doing. Mr. Hammond’s backstory, which he relates to Charles, goes on for 44 pages and would take a full hour to listen to. I skimmed it, but the gist is, he believed some false friends and unjustly accused his best employee and his wife of cheating on him. He discovers his mistake too late.

These backstories are drawn together when everyone ends up in or near London. Charles conveniently inherits a baronetcy from an eccentric uncle. A minor female character, Miss Chancely, inherits an East Indian fortune from another long-lost relative, and unaccountably, Julia falls in love not with Charles Evelyn but with Lord Meanwell. No reason is given for why she prefers one kind, handsome, virtuous, eligible, rich man to the other, and I was rooting for Charles. He manages to transfer his undying affection to Miss Chancely.

Julia always behaves impeccably and considering that she can’t be more than eighteen, she is quite impressive when she confronts Lord A— when he briefly returns from Paris to London. She tears a strip off him for taking advantage of the naïve Ellen. “For shame, for shame, do not seek to palliate your crimes… you knew she was a poor unprotected female, no father, no brother, to call you to account; you was by affinity and choice the man who ought to have preserved her from insult, from degradation, and from infamy. Would a man of honour… steal an unsuspecting young woman from her friends, carry her from the country with persons the most improper in the world for companions… and give the finishing blow to the existence of that excellent parent whose sole happiness and comfort was centered in her children? These, my Lord, are facts that cannot be controverted, no sophistry can overcome such glaring proofs of deception and cruelty, nor can fashion, gallantry, or libertinism, justify such detestable actions.”

Julia always behaves impeccably and considering that she can’t be more than eighteen, she is quite impressive when she confronts Lord A— when he briefly returns from Paris to London. She tears a strip off him for taking advantage of the naïve Ellen. “For shame, for shame, do not seek to palliate your crimes… you knew she was a poor unprotected female, no father, no brother, to call you to account; you was by affinity and choice the man who ought to have preserved her from insult, from degradation, and from infamy. Would a man of honour… steal an unsuspecting young woman from her friends, carry her from the country with persons the most improper in the world for companions… and give the finishing blow to the existence of that excellent parent whose sole happiness and comfort was centered in her children? These, my Lord, are facts that cannot be controverted, no sophistry can overcome such glaring proofs of deception and cruelty, nor can fashion, gallantry, or libertinism, justify such detestable actions.”Lord A— is so impressed that he goes back to Paris and marries Ellen to make her a respectable woman.

About the author

About the authorEliza Parsons (1739-1811) turned to writing novels after the death of her husband, a turpentine-distiller and business man. Her father was a wine-merchant. She was from the merchant class, although like other novelists she wrote of baronets and East India nabobs. She had eight children. She is the author of two of the "horrid "novels Isabella Thorpe recommends to Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) and The Mysterious Warning (1796).

Of Ellen and Julia, the reviewer said: “When the immoral tendency of some novels, and the romantic turn of many others, are recollected, it may appear in some sort meritorious that a work of this kind is entitled to the bare praise of affording a temporary amusement, without leaving any injurious impression on the reader’s imagination [but this novel] possessed something more than this negative merit. It is well adapted to inculcate on young minds several lessons of prudence and virtue.”

I found the extended backstories to be tiresome, and the narration, especially in the second volume, plods along. People came and went, visiting back and forth for tea and dinner, as the various aspects of the plot unfolded. But Mrs. Parsons herself was modest about her work: "I Trust, Tho' Perhaps Deficient in Wit and Spirit, Are at Least Moral and Tend to Amend the Hearts." Kudos to her for picking up her pen at age fifty to support her family. Scholar Karen Morton has written a biography and critique of Mrs. Parsons: A Life Marketed as Fiction: An Analysis of the Works of Eliza Parsons. Valancourt Books, 2011.

Published on June 27, 2024 00:00

June 18, 2024

CMP#192 Gertrude, who elopes and repents

“Oh, these faintings, so often, and then again directly, will soon do her business, I warrant, poor honey!” said Mrs. O’Flarty; but “but hould, hould a bit, now she is coming to herself, and now she sighs…”

“Oh, these faintings, so often, and then again directly, will soon do her business, I warrant, poor honey!” said Mrs. O’Flarty; but “but hould, hould a bit, now she is coming to herself, and now she sighs…” -- the Irish landlady in Black Rock House

CMP#192 Black Rock House: a psychological thriller from 1808

CMP#192 Black Rock House: a psychological thriller from 1808Synopsis with Spoilers by Mrs. E.G. Bayfield

Pop quiz: which events in Black Rock House cause our heroine, Gertrude Wallace, to faint dead away?When the man she loves pressures her to elope with him.When her husband leaves the ballroom with a beautiful woman, leaving her behind, seven months' pregnant.When she realizes that her husband is having an affair.When her husband threatens to blacken her name so he can divorce her.When she hears her husband has killed a man in a duel.When she’s reunited with her father who had cast her off. If you answered: “all of the above,” you’re right! Poor Gertrude suffers a great many travails in these three volumes—the book is punctuated with the thud of Gertrude hitting the carpet. Yet, she is a plucky girl--she does stay upright and conscious when she’s abandoned by her soldier husband and left behind, first in Bath and then in Ireland, when she’s in two storms at sea, when she’s caught in a flood, and when she's kneeling beside her husband’s “mangled corpse” after he kills himself. Many tears are shed of course... The purpose of the tale is to warn girls against impulsively eloping against their parent’s commands. This novel is firmly didactic and explicitly Christian in its message. (The author referenced the outstanding popularity of Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife to assert that religion is not “out of place when found in a novel”).

Just as with Charlotte Temple, the heroine agrees to meet her handsome, charming, ardent, lover, Lionel Audley, and tell him she won’t elope with him, then she faints and he scoops her away. I wonder if this is intended to absolve the heroine at least in part for her actions. If she knowingly steps into a carriage with a man to whom she is not married and travels to Scotland, perhaps the readers of the day would abandon all sympathy for her. (We recall that Lydia was laughing in this same situation in Pride and Prejudice, and wasn't at all dismayed when they didn't go to Gretna Green).

“All the combined emotions of her heart contributed to overwhelm her at this eventful moment; when she heard his expressions of eager expectation, when she saw the chaise which was designed to bear her away, she experienced an instantaneous stagnation of feeling, and fainted in the arms of Audley!”

“All the combined emotions of her heart contributed to overwhelm her at this eventful moment; when she heard his expressions of eager expectation, when she saw the chaise which was designed to bear her away, she experienced an instantaneous stagnation of feeling, and fainted in the arms of Audley!”On the Road to Gretna Green, Heywood Hardy

Mrs. Falconbridge sets her sights on the baronet. Bing AI image. However, Black Rock House is more sophisticated in plot than Charlotte Temple. Our heroine Gertrude, only 17, assumes she and her adored Lionel will have a happy ever after. He assures her that their respective parents will forgive them--but they don't. Both are disowned and cut off financially.

Mrs. Falconbridge sets her sights on the baronet. Bing AI image. However, Black Rock House is more sophisticated in plot than Charlotte Temple. Our heroine Gertrude, only 17, assumes she and her adored Lionel will have a happy ever after. He assures her that their respective parents will forgive them--but they don't. Both are disowned and cut off financially.After they've settled down in officer's quarters in Manchester, Lionel laughs as he reveals why Mrs. Falconbridge, the local merry widow, connived to help lure Gertrude away for the elopement. Gertrude was just a pawn in her game. The widow had her eye on Sir Russell, the local eligible baronet who was quietly in love with Gertrude and she wanted to clear her rival off.

“There was something very mortifying in the reflection, especially as Gertrude had hitherto plumed herself on possessing some penetration —'Never more must I pretend to any,’ thought she; ‘and yet, so fascinating, so specious was Mrs. Falconbridge, who but would have believed her amiable as she appeared?’”

It turns out that Lionel was also a deluded pawn—later, Gertrude learns from Mrs. Falconbridge herself that she had a double motive. The widow knew Lionel’s proud father would disinherit him for marrying a nobody. Mrs. F wants revenge--she wants the utter destruction of the Audley family, for reasons I’ll save.

Gertrude professes love and loyalty to Lionel although he soon tires of her, mocks her, ignores her, abandons her, cheats on her, ignores his little daughter because it’s not a boy, bankrupts himself through gaming, and flees after killing one of his creditors in a duel... And that’s not all. He meets and is infatuated with the beautiful heiress his father had picked out for him, whom he had rejected sight unseen in favor of Gertrude. Regretting his marriage to Gertrude, he wants a divorce, which means he must blacken her reputation. He wants her to be unfaithful to him so he'll have grounds for divorce. He leaves her with no money and turns her over to his superior officer, who wishes to make her his mistress.

I thought the author did a good job of drawing the net of doom around Gertrude and placing her in a horrendous situation—a situation which, despite the melodrama and the remarkable coincidences which abound in the tale, could have happened in real life. With barely any social safety net, and with no legal rights, a married woman really could find herself and her children abandoned and destitute in a strange town and be pressured to survive by selling herself.

box decorated with paper quilling Back in England

box decorated with paper quilling Back in EnglandA kindly older army officer rescues Gertrude from this fate and gives her enough money to travel back to England. In this section, the author uses some “ripped from the headlines” current events like the Battle of Corunna in Spain and a massive flood which hit Bath and a large swath of Britain in January 1809.

There’s also a strange interlude where Gertrude, trudging through the snow in search of a cheap lodging, encounters a giant (that is, a man with gigantism) who has escaped his confinement. He is a “freak” in a travelling exhibition and he makes a passionate and eloquent speech about his horrible life. As Gertrude informs him to his face, God must have sent him to cross paths with her, so that she can be reminded that some people have it worse than she does. (Gee, glad I could help!) He lopes off through the snow like Frankenstein's monster and we don’t see him again.

Gertrude writes her father, begging him to take her baby under his roof, while she earns a living somehow or other. While waiting for his answer, she makes and sells boxes (probably filigree boxes?) while worrying about her husband, who is on the lam. “’Oh! That [Lionel] were but here, in this little room!’ cried Gertrude; ‘these hands would cheerfully, unceasingly pursue their office; and sweet would be the morsel which they earned, did they conduce to a husband’s maintenance, a husband’s comfort!’” And this is after all of the above...

After losing her trunks in a flood, Gertrude has only the clothes on her back and enough money to travel back to her home town.

Reconciliation Small World!

Reconciliation Small World!The unintentionally hilarious denouement comes when all the major characters converge at the same moment at the same Inn, Black Rock House, where Lionel commits suicide in the courtyard—his father arrives, the avenging villainess (who is Sir John’s illegitimate daughter, resentful half-sister to Lionel) arrives to crow in triumph over the destruction of the family, then Gertrude’s father and stepsister arrive. At this moment of tragedy, Gertrude's little daughter, also named Gertrude, is a picture of innocence who melts all hearts.

Gertrude’s repentant father-in-law announces that little Gertrude Jr. will be the heiress to his estate but he leaves the baby to be raised by the Wallace family because “I have forcibly shown that neither by instruction or example am I fitted for the arduous task of education.” Seeing as his daughter is an avenging psychopath and his son was a cheating, whoring, gambling waste of space.

Gertrude and her daughter go home to her father’s estate. Gertrude dies of a decline, i.e, consumption, leaving her gentle stepsister Catherine to raise the little girl. Catherine eventually marries the eligible baronet, Sir Russell.

Bing AI image Other Features

Bing AI image Other FeaturesOne of the army officers, Mr. Silvertop, is used for comic relief and gets a lengthy description. He is “effeminate.” I’ll save that for another post on depictions of homosexuals in novels of this era. Another comic character is the spinster/heiress who foolishly thinks that Audley’s friend Major Perceval is marrying her for love. She is a female pedant , and the comedy of her malapropisms outstays its welcome.

Sir Russell Powis, the baronet who holds a torch for Gertrude, is a single man in possession of a good fortune in want of a wife. We’re supposed to believe that he’s a dud socially because he is so timid and reserved. Seriously? He’d have husband-hunting mamas all over him and more dinner invites than he could accept. Gertrude is not rewarded with a happy marriage with him after her first husband kills himself. That wouldn’t send the right message to the young readers. Gertrude must die. The point is that after her first serious error in eloping, she behaved impeccably and she will go to heaven.

The villainess, Mrs. Falconbridge, would be a candidate for scholars looking for subversive pro-feminist messages because she is no helpless shrinking violet. She makes her own way in the world quite capably.

Crazy ladies on a cliff: I recently reviewed the novel What Has Been (1801) . A contemporary critic slammed that novel for being derivative. He said, "The wild insanity of the lady at Teignmouth [who warned the heroine to beware the wiles of men] has numerous prototypes…" Well, here we are seven years later, and novelists were still using crazy ladies on a cliff as a foreshadowing device. Gertrude sees one right after her wedding at Gretna Green. The crazy lady tells Gertrude that she eloped twenty years ago: “Oh! Then—oh! Then, what day-dreams of delight went with me!... I left my tender father, and pursued my fated way to Scotland—with a villain!... And here I wander… placed as a beacon… to warn the trusting female to turn back ere yet too late—ere yet she tempts a father’s curse!”

Rifleman at Battle of Corunna About the author

Rifleman at Battle of Corunna About the authorMrs. E.G. Bayfield is thought to have been an army wife herself. She adds a disclaimer that although several of the officers she portrayed in the book are utter rotters, she did not want to “be accused of attempting to lower the character of our soldiers. We honour our heroic defenders,” and she “purposely introduced” the decent old stick Colonel Purbeck. Likewise, she has both good and bad members of the nobility.

The reviewer assumed the author was a man. “With respect to the moral, he has in a great measure done his best to shew how extremely wrong young women are, who, despising the experience and common sense of their parents, rush wild and foolish on a world of trouble, quitting a parent’s protecting arms and comfortable home, with love, blind love only for their guide, to the embraces of a dissipated young officer for their husband.” The reviewer objected to Audley’s suicide: “the story might have been wound up with equal or more interest if the hero had been made rather to bear the ills he had, than fly to others that he knew not of.” The reviewer also objected to the villainess: “his natural daughter is so truly diabolical, that it spoils the whole piece by its unnatural wickedness.”

Despite my criticisms, I think Black Rock House is worth a look for those who want a comparison to the Lydia/Wickham marriage in Pride and Prejudice, that is, who want to compare a tragic approach to Austen's approach. Also, the gradual way Mrs. Falconbridge's villainy is uncovered, makes this novel an early example of a slow burn thriller. It's also an example of how some female novelists prescribed the ideal of loyalty to a husband, no matter what, in the "bear and forebear" vein.

Previous post: Foundling plots and seduction plots

Published on June 18, 2024 00:00

June 12, 2024

CMP#191 Foundling Plots & Seduction Plots

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#191 Two minor novels--the foundling plot and the seduction plot

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#191 Two minor novels--the foundling plot and the seduction plot Here are two brief examples of two popular genres of the long eighteenth century. Both novels rely on improbable coincidence for their resolutions:

Miriam (1800) by Mrs. E.M. Foster

Miriam (1800) by Mrs. E.M. Foster“Oh, for mercy’s sake turn back! You know not on what a precipice you stand—a terrible gulph yawns beneath it, and you will be swallowed up for ever!”

The young man standing on the edge of a cliff, about to jump, must be impressed at our heroine’s eloquence, because at a moment of crisis she is speaking metaphorically, not literally, as she warns him of the damnation awaiting the person who commits suicide.

“Think of your merciful Creator; --for what did he send you into this world? Oh blessed, thrice blessed are those whom he chasteneth! Turn back, I conjure you turn back…”

The persuasions of this beautiful girl who has appeared out of nowhere does the trick, and our unknown young man steps back from the edge, totally smitten. But he soon disappears and Miriam only knows that his name is Henry....

Seductive houseguest: Mr. Crawford in Mansfield Park Thus we have the dramatic opening to Miriam. Miriam, since finishing her education, has been living in a big empty old castle with two garrulous but loyal servants. Her guardian Mr. Fitzpatrick made his fortune in India and he brought young Miriam back to England with him. Who her parents are, or how he came to be her guardian is a mystery, but he likes to remind Miriam that she owes every meal she eats and the clothes on her back to him. Miriam resents this—she’s a bit feistier than Fanny Price in Mansfield Park.

Seductive houseguest: Mr. Crawford in Mansfield Park Thus we have the dramatic opening to Miriam. Miriam, since finishing her education, has been living in a big empty old castle with two garrulous but loyal servants. Her guardian Mr. Fitzpatrick made his fortune in India and he brought young Miriam back to England with him. Who her parents are, or how he came to be her guardian is a mystery, but he likes to remind Miriam that she owes every meal she eats and the clothes on her back to him. Miriam resents this—she’s a bit feistier than Fanny Price in Mansfield Park.And when her guardian and his haughty new wife bring houseguests from London for a visit, Miriam, despite her dependent status in the household, doesn’t hesitate to call out the dashing Mr. Mortimer for the dangerous flirtation he's embarked on with Mrs. Fitzpatrick. Fanny Price said nothing about the shenanigans going on around her but Miriam scolds: “What is the honour of him, who…. while an inmate of the house of him whom he calls friend, is privately stabbing at his peace, is undermining his happiness, is plotting the everlasting ruin of his wife!”

Another houseguest is Henry, the handsome young man she saved from jumping, who turns out to be Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s brother. He is harboring a secret (obviously) and seems to have a secret understanding with the young woman who just married his rich old uncle, both of whom are also visiting. These mysteries lead to misunderstandings which keep Henry and Miriam apart.

Pushed into Mr. Jason's arms Bing AI Image Creator Unlike Fanny, Miriam flees

Pushed into Mr. Jason's arms Bing AI Image Creator Unlike Fanny, Miriam fleesMiriam flees her unhappy home situation when Mr. and Mrs. Fitzpatrick try to force her into marriage with a vulgar old farmer. Her luck turns when she meets a benevolent older man, also back from India, in the very first mail coach she hops in to. He is so taken with her that he offers her a home. And although some gossipers in Bath assume she’s a kept mistress, he truly is a nice fatherly guy who already has one young female ward.

Her new guardian, Mr. Seymour, is struck by Miriam’s resemblance to his beloved late wife who--so far as he knows—perished with his baby daughter when the ship bringing her to India sank. Aaaand I think we can leave it at that.

The mystery of Miriam’s parentage is cleared up, her stolen inheritance is returned to her, and the misunderstandings between her and Henry Stafford are also cleared up.

At the same time that Mr. Fitzpatrick’s villainy comes to light, his life falls apart. Let’s let the faithful but garrulous old servant Joanna break the news: “Oh Miss! This comes of old gentlemen or elderly gentlemen marrying young beauties, never no good can come, I’m very sartin, but howsomedever I’ll tell you—Last night, ‘twas near ten o’clock, and Joseph was just a-stirring out the fire, and I was unpinning my cap when (etc. etc., etc.)… Well, Miss, the short and the long is that Mrs. Fitzpatrick has ‘loped, and carried off a deal of money with her…. All the servants know was ‘tis with a young East Indian, as she keept company with a great while...”

So, lots of object lessons: don’t marry just for wealth and rank, but marrying when you’ve got no money is a bad idea as well. Instead, marry the impetuous man of sensibility who consistently misinterprets your actions and even accuses you of being a kept woman because he overheard some gossip at the opera.

For all the mention of India, there is no reflection on the cruelties of empire. The social conflict is between the monied nouveau riche and the proud but purse-poor nobility.

I am so used to reading about people being bled when they develop fever after a horrible shock, when Miriam fell ill, I was thinking: Hurry! Summon the apothecary--aren't you going to bleed her? And I was relieved when they did! I guess that's what comes of reading so many old novels. About the Author:

There are no available biographical details about Mrs. E. M. Foster. She wrote feverishly, publishing four novels in one year (1800) for the Minerva Press. Or, perhaps the name is an all-purpose pseudonym used for the work of several anonymous writers. It could be --her name is tangled up in the mystery of who wrote The Woman of Color.

The Critical Review sniffed: “there is nothing new or surprising in the history of Miriam;—we found little to blame, and less to praise.” The Monthly Magazine was even more dismissive. “We could enumerate a great many more [just published] novels—“The Irish Excursion,” “Miriam,” –“Midsummer Eve, or the Country Wake," &c. &c. &c., but many of them are scarcely worth the trouble of transcribing." Modern Characters (1808) by Edward Montague

This novel begins with a warning about the pernicious effects of romance novels and ends with an entirely improbable romance. Modern Characters is a seduction novel, warning of the dismal fate of girls who surrender their virtue before marriage, in the vein of Charlotte Temple . Emily Henderson is particularly vulnerable, since she has an apathetic father, a cold-hearted step-mother, and she read too many romance novels at boarding school. Her best friend Miss Fordyce is not only addicted to romance novels, but she’s an aspiring author. Emily is a sitting duck for the blandishments of the charming Charles Stanly. Modern Characters gives us a tour of the places in London where couples could meet for assignations: fruiterers’ and milliners’ shops were sometimes fronts for brothels. Most of the novel, in fact, is set in brothels disguised as boarding houses, amongst heartless panderers and corrupt, drunken men of the gentry class.