CMP#161 Abolitionists versus "The Interest"

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#161 Review: The Interest: A Comprehensive History of the Abolition Debate by Michael Taylor

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. CMP#161 Review: The Interest: A Comprehensive History of the Abolition Debate by Michael Taylor

If you're looking for a comprehensive history of the campaign to abolish the slave trade and slave ownership in Britain's Empire, this book would be a good choice. An astounding amount of research has gone into it and Michael Taylor is a good writer with an eye for the apt quote. He explains the arguments--personal, pragmatic, economic, religious, and political--raised by the influential power brokers who opposed the abolition campaign. Taylor also gives us frequent and vociferous condemnations of slavery. I presume this is not because he feels we, his readers, must be convinced that slavery is bad, but rather to forestall anyone who thinks that if he explains the plantation-owners' point of view, he is somehow defending them. It is jarring to see, for example, cartoons from the time which poke fun at the abolitionists.

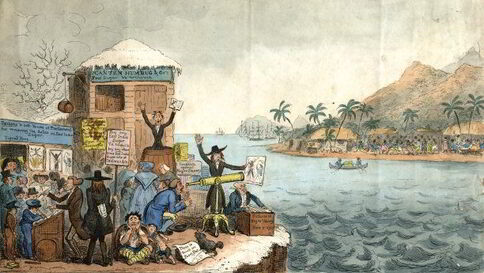

If you're looking for a comprehensive history of the campaign to abolish the slave trade and slave ownership in Britain's Empire, this book would be a good choice. An astounding amount of research has gone into it and Michael Taylor is a good writer with an eye for the apt quote. He explains the arguments--personal, pragmatic, economic, religious, and political--raised by the influential power brokers who opposed the abolition campaign. Taylor also gives us frequent and vociferous condemnations of slavery. I presume this is not because he feels we, his readers, must be convinced that slavery is bad, but rather to forestall anyone who thinks that if he explains the plantation-owners' point of view, he is somehow defending them. It is jarring to see, for example, cartoons from the time which poke fun at the abolitionists.We also have graphic detail of the misery of life on a sugar plantation, where the planters protested that (a) life in the West Indies was delightful, better than living in Africa, and (b) enslaved Africans were naturally so indolent and the work so hot and miserable that there was no alternative but to use the lash. Taylor shows how the economic booms and busts of the early 19th century affected the progress of the campaign to free the slaves, and of course it mattered who was in power in Parliament as well. Few abolitionists thought that immediate and total emancipation was likely, but some readers might be surprised to learn that few of them thought it was feasible, either, or thought that Blacks could or should become the social equals of their former captors. Rest assured that if anyone on the abolition side has feet of clay, Taylor points it out. It was interesting to learn that the sainted William Wilberforce did not approve of women getting involved in anti-slavery campaigns, as it was unfeminine of them to push themselves into public affairs. Taylor also names and shames the politicians who had opposed abolition but then flipped and called it a great moral achievement once it was accomplished.

I appreciated all the detail and nuance that Taylor brings to this history. However, as others have mentioned, it's a lot to read and I skimmed the latter part of the book because I was more interested in what was going on during Jane Austen's time, or during the period when her brother Henry was chosen as a delegate to an abolition convention. In addition to learning about all the principal players in the debate, we have lots of detail about the ground-level campaign, what journalists and cartoonists had to say, as well as the testimony of that handful of emancipated Blacks who were able to tell their own story. I also checked out some of Taylor's primary sources. This book is a rich resource for finding the key documents, publications, and even novels of the period.

Slavery came to an end in the United States after a terrible war, costly both in human and material life. In the British empire, owners of enslaved persons were compensated for giving them up, but the enslaved persons, in either case, received no compensation. Slavery is still not eradicated from the globe. In this 1826 cartoon by Robert Cruishank, "John Bull taking a clear view of the Negro Slavery Question!!" Abolitionists looking at the West Indies from a distance are shown as agitating about the dire conditions of enslaved people when, golly gee, it's actually a paradise over there in the sugar plantations with enslaved folks dancing happily.

The Interest is adapted from Taylor's PhD thesis. The argument of his thesis, insofar as there is one, is that Britain does not deserve to congratulate itself for having abolished slavery and

fighting the slave trade on the high seas;

that rather, we all should learn more about the role slavery paid in Empire, we should knock anyone (like the Duke of Wellington) who opposed the abolitionists off their pedestals, and we should criticize the abolitionists for not doing or thinking what we surely would have done and thought if we'd been in their shoes. We should name the recipients of the compensation monies and also publicize the names of their descendants. There ought also to be frank dialogue about reparations.

The Interest is adapted from Taylor's PhD thesis. The argument of his thesis, insofar as there is one, is that Britain does not deserve to congratulate itself for having abolished slavery and

fighting the slave trade on the high seas;

that rather, we all should learn more about the role slavery paid in Empire, we should knock anyone (like the Duke of Wellington) who opposed the abolitionists off their pedestals, and we should criticize the abolitionists for not doing or thinking what we surely would have done and thought if we'd been in their shoes. We should name the recipients of the compensation monies and also publicize the names of their descendants. There ought also to be frank dialogue about reparations.So far as I can observe, Taylor's point of view is well on the ascendant. For more on what women did to fight slavery, "Women Writers and Abolition," by Deirdre Coleman, in Volume 5 of The History of British Women's Writing 1750-1830, edited by Jacqueline M. Labbe, lists and quotes the female writers, chiefly poets, who used their talents in the abolition campaign. Many women novelists included the abolition debate in their novels, such as Eleanor Sleath in her book The Bristol Heiress. You can find more examples here. The campaign to boycott sugar was called the Anti-Saccharite campaign. I reference it in my novel, A Contrary Wind. One of my characters, the widow of a Bristol ship-builder, refuses to serve sugar at her tea table. Click here for more about my books. Previous post: Book Review: Lady Maclairn

Published on November 16, 2023 00:00

No comments have been added yet.