Danny Dorling's Blog, page 7

June 30, 2023

The crises combine: austerity, cost-of-living, public sector jobs and pay

The UK government may be taxing people more (other than the very well off) than it has done in many decades, but that does not mean it is spending more on public services in real terms, or even living up to what it has previously promised to spend.

In April 2023 it was quietly announced that the Sunak government had halved the funding it had promised to help support the social care workforce. In December 2021, when Sunak had been Chancellor for almost two years, a promise had been made to invest ‘at least £500m over the next three years’ into social care. This was part of the White Paper on adult social care reform. Fifteen months later, in April 2023, that promise was halved to £250 million.

The learning disability charity Mencap reacted angrily, labelling the U-turn as an ‘insult’ and explaining that ‘the plan had now been diluted beyond recognition.’ [1]. There are currently 165,000 too few care workers in place and now there is little hope this will be remedied. One consequence of the previous cuts to social care spending had been rising mortality in Britain since 2012 among many at risk groups, especially the most frail and elderly. When the promise was broken, the charity Age UK explained that funding was no longer even ‘remotely enough’. The King’s Fund health think-tank was also damming in its assessment. The Trades Union Congress labeled the U-turn: ‘slashing’. The GMB union, which represents many care workers, called the decision, ‘disgraceful’.

Cumulative real-terms pay changes for FE staff relative to 2010–11, 2007-2023 (source IFS)

Earlier in the spring of 2023 the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) had noted a dire situation in another state sector: Further Education, one which employs 50,000 teachers. The IFS noted that by 2023, in today’s money, the median pay for a school teacher had fallen to £41,500 a year, but for a Further Education college teacher is was now only £34,500. In real terms, between 2010–11 and 2022–23, the median salary for a school teacher had been reduced by 14%, but the median salary for a college teacher had been slashed by 19%.

As a result of worsening conditions and declining pay , some 16% of all Further Education college teachers leave the profession each year. This compares ‘with 10% of school teachers, 10–11% across most NHS occupations and 7–8% in the civil service.’ [2] The cut in real terms pay was far worse in the most recent year (2023) as compared to any other year, possibly any year since Further Education began. In the 1970s pay tended to increase above inflation. How had we got into this state and what is to be done?

On 29th November 2022 the Office for National Statistics, in effect, nationalized the Further Education college sector by reclassifying it in the public accounts. Further Education colleges were made public bodies overnight, not private anymore. Suddenly those who run them can no longer be paid more than £150,000 a year unless they seek the special permission of government each and every time they try to do this. [3] The government immediately declared that ‘Following the reclassification, colleges and their subsidiaries are now part of central government.’ One implication was that no one in the sector could be paid more than the Prime Minster. Those Further Education bosses who had been setting the salaries of college teachers so low now had to look at their own pay. [4] This is a start, but there is so far to go.

These are just two parts of a British public sector that have, as a whole, now been decimated many times over, but all this is part of a much longer process. It began in the 1970s when the fight to protect jobs and the public sector more widely was lost. The public sector and decent progressive taxation had been won in the 1920s and 1930s through a huge amount of collective action, not least by people striking for their rights.

The strikes of the 1920s were successful in contributing to rising equality, both at the time and especially afterwards. The wave of strikes that began in the 1970s dwindled after the defeat of the miners in 1984/85. The wave that began in 2022 is still extremely small, and has to be highlighted to be visible in this historical series. This is despite the workforce being far larger today and the graph not being corrected for that population growth.

We are still living in a land that was poisoned by Thatcherism. We were brought low by a doctrine of ‘me-first’ selfishness that continues to hobble really effective action. We were torn apart in the 1980s as inequality soared back up to levels not seen since the 1920s. We have not recovered any ground at all. Inequality is now embedded at a very high level.

Socially, the UK is more starkly divided than any other state in Europe. We have a multi-tier education system, a two tier-health system (private and state), and a chasm between those who rent or own their home. And strikes are on the increase again, but as yet are not that widespread. Living standards will continue to fall even as the rate of inflation falls, because prices will still be rising faster than prices for some time to come.

Numbers of days lost per year due to strikes in Britain, 1892-2022 (source ONS)

Politically, the UK is riven with divisions that reflect our underlying economic and social severing. The resentment is rising, and many attempts are being made to stop it becoming more focused. Brexit and the culture wars are still being exploited by charlatans. They have fertile ground to till as social division results in short fuses and little patience and tolerance. We desperately need a more cohesive society with a much higher degree of trust between people and – eventually – a renewed sense of common purpose. The UK is such a long way from this.

Not everything can blamed on Thatcherism. Labour and the Liberals must take part of the blame. Especially in England where there has been such an enormous failure to think differently. New Labour offered a methadone alternative to the Tories’ heroin. It alleviated a few of the symptoms, but we are back and hooked on the true opiates again now. You cannot kick the habit by just watering down the product.

The Corbyn project was viewed by many as an impossibility. However, all it really offered was a bit more tax and spend. This is how salted the earth has become. Even modest proposals have been ruled out of bounds; but today nationalization of Further Education and much else, from Railways to Housing Associations, becomes forced on us or at the very least a topic for consideration, as the privatization experiment of 1980-2020 crashes and burns.

Policy solutions abound – green deals, wealth taxes, common ownership of utilities and public services, a growing co-operative and employee-owned business sector, but they are hard to introduce and sustain while our politics remains poisonous.

As Daniel Chandler recently explained in his book “Free and Equal” (endorsed by Vince Cable Angus Deaton, Stephen Fry, Andy Haldane, David Miliband, Jesse Norman, Amartya Sen, Minouche Shafik, Thomas Piketty, Rowan Williams and Linda Yueh) that we need an entire over-haul of our electoral system, proportional representation, strict controls on any individual person funding political parties more than any another, and very high levels of progressive taxation. I am not sure all those who endorsed the book read to the end and saw the conclusions being made before they wrote their words of praise; but maybe they did.

Proportional representation and a constitutional overhaul are the building blocks required. They seem beyond reach at the moment, but to construct anything you first have to visualize and articulate it, so let’s at least do that with energy and hope. The alternative is no care in our old age, no teachers for our children at college, and little decency left in public life.

As the crises combine and continued austerity mixes with a cost-of-living nightmare, as public sector jobs are being lost and pay in real terms is cut, There are some real signs of hope: nationalization returning and progressive pay deals becoming the norm. [5] However, the sun-lit uplands now appear to be so far away that is easy to give up hope. Perhaps this is what it will take for change to come? The bad times still have to run their course for it to be clear just how wrong the ideas that got us here were.

References

[1] Adam Forrest (2023) Tory ministers accused of ‘insult’ to social care as workforce reform funding halved, The Independent, April 4th, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/social-care-funding-tories-sunak-b2313677.html

[2] Luke Sibieta and Imran Tahir (2023) What has happened to college teacher pay in England?, Institute for Fiscal Studies, March 30th, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/what-has-happened-college-teacher-pay-england

[3] Julian Gravatt (2023) Are universities really at risk of ending up in the public sector?, Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), 21 March, https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/03/21/are-universities-really-at-risk-of-ending-up-in-the-public-sector/

[4] Department for Education (2023) Further education reclassification: government response, Policy Paper, November 29th, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/further-education-reclassification/further-education-reclassification-government-response

[5] Dorling. D. (2023) Are things about to get better? Prospect Magazine, April 5th, May issue, pp.38-41, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/essays/have-we-reached-peak-inequality and at https://www.dannydorling.org/?page_id=9653

For a PDF of the original article and a link to where this was first published, click here.

June 14, 2023

Revisiting the point-source hypothesis of the coronary heart disease epidemic in light of the COVID-19 pandemic

The 20th century coronary heart disease pandemic remains a partial enigma. Here we focus on sex differences in mortality as an indicator of the disease during a time when classification of cause of death was uncertain. We suggest that cohorts born during a few decades around the turn of the century bore the brunt of the pandemic, and propose that the 1889-1895 Russian influenza epidemic may have contributed to this. That some evidence points to the introduction of a human seasonal coronavirus during the 1889-95 pandemic adds contemporary relevance to these speculations. …

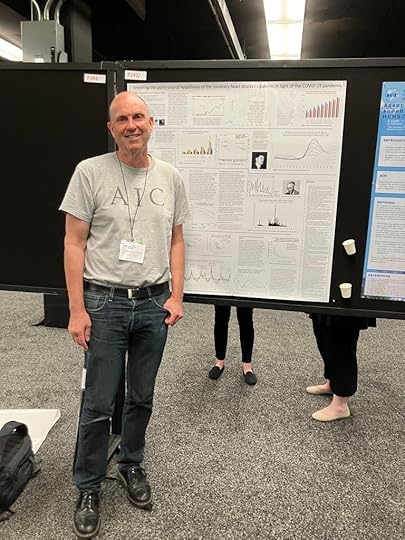

George Davey Smith, Society of Epidemiologic Research annual meeting, Portland (Oregon) USA, 14 June 2023, obscuring the key graph (see link below and here for the full sized poster)

…In the current pandemic, continued elevated risk for overall arterial events (including CHD and ischaemic stroke) has been reported at 36 weeks post infection (Figure 17, Reference 30) and this has persisted beyond this time. Whilst underlying risk could generate this finding, it is possible that repeat infection in an early 20th century population among which artificial vaccination was obviously not available led to a long-lasting relative elevation in risk. Further work on this highly speculative hypothesis will primarily depend upon identifying historical human and bovine samples allowing precise identification of when HCoV OC43 was introduced into human populations. Longer follow up individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 when they were immunologically naïve, with a comprehensive set of sensitivity analyses, will allow better characterisation of possible the long-term cardiovascular effects of a novel HCoV entering human populations.

Click on the image below and open it in a new tab to zoom in.

Or click here for a PDF Download PDF (2.7 MB)

Download PDF (2.7 MB)

Revisiting the point-source hypothesis of the coronary heart disease epidemic in light of the COVID-19 pandemic

To see the detail in a pdf of the poster, and where it was originally presented click here

References (with embedded links)

2. James B. Herrick (1919) Thrombosis of the Coronary Arteries, JAMA, 72(6):387-390.

8. Jerry Morris (1957) The Uses of Epidemiology, Edinburgh & London: E. & S. Livingstone.

13. ONS (2011) The 20th Century Mortality Files – 1901-2000, released: 11 March 2011.

14. Jerry Morris (1951) Recent history of coronary disease, The Lancet, Jan 13;1(6646):69-73.

June 6, 2023

Weakened by a decade of austerity: why the UK’s covid-19 inquiry is right to look at policies since 2010

Any concerns that the UK’s covid-19 inquiry would give ministers an easy ride seem to have been dispelled by the determination with which its chair, Heather Hallett, has pursued information held by former prime minister Boris Johnson.1 The government, likely alarmed by the risk of disclosing similar information from current ministers, fought back with a judicial review of her action.2 Inevitably, this unprecedented measure has dominated media coverage, diverting attention from an equally important development: reports that the inquiry will take evidence from former prime minister, David Cameron, and former chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne.3 Given the pandemic began in 2020 and both men had left office four years previously, some may ask what interest their testimony can be to the inquiry.

In fact, the decision to invite them sends out a very important message. Much attention has, rightly, focused on the events during the first few weeks of the pandemic. The release of the questions sent by Heather Hallett to Boris Johnson, a consequence of the government’s legal action, has revealed her interest in why the then prime minister seemed so disengaged from what was happening, and in particular why he failed to attend briefings.4 However, her interest in what political leaders from previous administrations have to say shows that she is also interested in earlier decisions that left the UK weakened, contrary to an independent assessment that suggested that it was well prepared.5

It has almost become a cliché to say that the pandemic shone a light on the fractures in society, picking out communities where many lived precarious lives and where social safety nets had been shredded.6 Yet, in the UK, it is arguable that this illumination should have been unnecessary. The signs were already visible for all to see. Since 2014 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) have repeatedly revised down their population projections,7 with one estimate that a million lives will end earlier than anticipated by 2058 as a result.8 Indeed, we and others had done what we could to draw attention to them.9,10,11,12

Over more than a century humanity has achieved remarkable progress in improving health. This has accelerated over the past two centuries, for reasons that include improved living conditions and, most recently, advances in healthcare. There have been declines in some places and at some times, but usually for reasons that were obvious, such as wars, famines, and pandemics.13 Consequently, any evidence that this progress is being interrupted for reasons that are, at least initially, unclear should give pause for thought. One such decline occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1980s, something we now know was the earliest sign of a failing state.14 Hence, when the first signs emerged that progress in life expectancy, for some groups, was stalling in the UK in the 2010s, those in power should have at least asked why.15

It is almost never the case that patterns of mortality in a population have a single cause. Public health scholars recognise the importance of causes and the “causes of the causes.” Responsibility for the sinking of the Titanic can easily be attributed to the iceberg but further insights are needed to explain why the death rate was so much higher for third class passengers compared with first class passengers.16 An earthquake in a country with high and rigorously enforced building standards will kill fewer people than one of the same magnitude where the construction industry is beset by corruption.17 Similarly, while the immediate cause of the covid-19 pandemic was obviously the SARS-CoV-2 virus, those looking from a public health perspective ask why some countries fared worse than others and, within them, why some groups suffered more than others.18

Seen from this perspective, it is entirely understandable that Hallett will want to talk to political leaders from the 2010-2016 governments. Faced with a global financial crisis, the coalition government chose to adopt a package of extreme austerity measures. This brought the nascent recovery occurring under the previous Labour government to a halt, unlike in other countries that adopted policies to stimulate the economy.19 They included decisions to shrink the role of the state, reducing expenditure across government. By the late 2010s the impact on health was apparent, with the UK falling further down the global ranking of life expectancy,20 competing with the United States, where the term “deaths of despair” was already entering the policy lexicon.

Yet even then, when the UK’s poor performance could no longer be disputed, it seemed impossible to get anyone in a position of authority to take any notice. When they did, it often seemed that their focus was on any reasons other than the effects of austerity that could explain it.21,22 But if anyone had been counting the rising numbers of premature deaths that would not have occurred if the UK had made similar progress to its European neighbours, the alarm bells may have rung.

Many of us suspect strongly that it was the cumulative consequences of austerity policies initiated by the Coalition Government after 2010 that created the conditions that allowed covid-19 to do so much more damage in the UK than in many of its neighbours.23,24,25,26 A greatly depleted civil service struggled to respond. A weakened public health system was often marginalised. Millions of people who had been just about managing were struggling with the public health measures needed to interrupt transmission of covid-19. While our focus is on the poor health of the population and the reasons behind it, the TUC has also highlighted unsafe staffing levels in public services, diminished public service capacity and resource, the weakened social security system, and loss of health and safety protections at work.27 It is therefore entirely appropriate that Heather Hallett should want to hear from the architects of the policies that gave rise to this situation.

Martin McKee, Professor of European public health

Lucinda Hiam, DPhil candidate

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography

Competing interests. MMK is president of the British Medical Association and as a member of Independent SAGE he was requested to submit written evidence to the covid-19 inquiry and has done so.

References

1. What is the UK Covid-19 Inquiry? 2023. https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/ (accessed 2nd June 2023)

2. Government to take legal action against Covid inquiry over Johnson WhatsApps. inews.co.uk, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2... (accessed 2nd June 2023)

3. George Osborne summoned to Covid Inquiry over impact of NHS austerity cuts on pandemic. inews.co.uk, 2023. https://inews.co.uk/news/george-osbor... (accessed 2nd June 2023)

4. Covid inquiry: 12 major new questions facing Boris Johnson from the documents. inews.co.uk, 2023. https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/bor... (accessed 2nd June 2023)

5. Nuclear Threat Initiative. Global Health Security Index Web Site. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security & The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2019.

6. Precarious employment and health in the context of COVID-19: a rapid scoping umbrella review. Eur J Public Health 2021;31(Supplement_4):iv40-9. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckab159 pmid:34751369

7. The end of great expectations? BMJ 2022;377:e071329. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071329 pmid:35512810

8. Life expectancy in Britain has fallen so much that a million years of life could disappear by 2058 – why?: The Conversation, 2017. http://theconversation.com/life-expec... (accessed 3rd June 2023)

9. Things Fall Apart: the British Health Crisis 2010-2020. Br Med Bull 2020;133:4-15. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldz041 pmid:32219417

10. Why has mortality in England and Wales been increasing? An iterative demographic analysis. J R Soc Med 2017;110:153-62. doi:10.1177/0141076817693599 pmid:28208027

11. Why is life expectancy in England and Wales ‘stalling’?J Epidemiol Community Health 2018;72:404-8. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-210401 pmid:29463599

12. Stalled improvements in mortality and life expectancy predate the pandemic. BMJ 2023;380:493. doi:10.1136/bmj.p493 pmid:36868567

13. Mortality trends and setbacks: global convergence or divergence? Lancet 2004;363:1155-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15902-3 pmid:15064037

14. Commentary: the health crisis in the USSR: looking behind the facade. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1398-9. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl237 pmid:17085454

15. Rise in mortality-when will the government take note? BMJ 2018;361:k2747. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2747 pmid:29941609

16. Health Inequalities: From Titanic to the Crash. Policy Press, 2013.

17. Corruption kills. Nature 2011;469:153-5. doi:10.1038/469153a pmid:21228851

18. Inequalities in SARS-CoV-2 case rates by ethnicity, religion, measures of socioeconomic position, English proficiency, and self-reported disability: cohort study of 39 million people in England during the alpha and delta waves. BMJ Med 2023;2:e000187. doi:10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000187 pmid:37063237

19. Austerity: a failed experiment on the people of Europe. Clin Med (Lond) 2012;12:346-50. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-346 pmid:22930881

20. Falling down the global ranks: life expectancy in the UK, 1952-2021. J R Soc Med 2023;116:89-92. doi:10.1177/01410768231155637 pmid:36921623

21. When experts disagree: interviews with public health experts on health outcomes in the UK 2010-2020. Public Health 2023;214:96-105. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2022.10.019 pmid:36528937

22. Austerity, not influenza, caused the UK’s health to deteriorate. Let’s not make the same mistake again. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021;75:312. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-215556 pmid:33004658

23. Is austerity a cause of slower improvements in mortality in high-income countries? A panel analysis. Soc Sci Med 2022;313:115397. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115397 pmid:36194952

24. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the age of austerity. J Epidemiol Community Health 2022;76:743-5. doi:10.1136/jech-2022-219011 pmid:35667853

25. Austerity and old-age mortality in England: a longitudinal cross-local area analysis, 2007-2013. J R Soc Med 2016;109:109-16. doi:10.1177/0141076816632215 pmid:26980412

26. Local government funding and life expectancy in England: a longitudinal ecological study. Lancet Public Health 2021;6:e641-7. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00110-9 pmid:34265265

27. TUC. Austerity left UK “hugely unprepared” for the Covid pandemic – TUC. 2023. https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/austerity... (accessed 5th June 2023)

For a PDF of this article and link to original publication and all endnote references in full, click here

May 27, 2023

Slowdown means the end of pervasive capitalism

Danny Dorling discusses the end of the age of speed in his book Slowdown. While examining the phenomenon of “slower progress” in the face of the ever-increasing population, workforce and capital in the world under the spell of progress, the book draws attention to sustainable solution steps that can be taken in line with future expectations.

First published 27 May 2023

The cover of “Slowdown”, Turkish Edition

Questions by Gunay DEMIRBAG

The fact that what we see of as the rapidly growing world appears to be on the edge of burnout has brought the concepts of slowdown and sustainability, which have been talked about for a long time, higher up the agenda. We asked British writer Danny Dorling our questions about the global ‘Slowdown’.

What do you mean by slowing down and when was the first thought in the world to slow down?

Slowing down (a word first used in the 1890s to mean going slower) affects many things today. It was first seen globally in the context of human population growth, which began to slow around 1968 and has since slowed. The increase in the number of people corresponds to a smaller percentage each year compared to the previous year. Soon there will be a smaller absolute numbers being added. According to UN projections, when we reach 2086, our numbers will start to decrease every year, which will be a first in human history. At least as far as we know.

Slowing down affects all areas. In addition to our population, our global economic growth and innovation speed are declining. The slowdown now affects much more than the population growth rate. It affects almost every area of our lives. Our current slowdown represents a major challenge to the expectation of acceleration and a step into the unknown.

To what extent are our current belief systems (economic, political, and others) built on assumptions of future rapid technological change and sustained economic growth? It’s hard to accept the slowdown that awaits us. Areas that haven’t slowed down yet are: carbon pollution, temperature rises, and the number of global students studying at university. But these will also start to slow down soon, some sooner than others.

Acknowledging the slowdown that awaits us will require us to change our fundamental view of change, innovation and discovery, which we see as purely beneficial. Can we accept that we have to stop waiting for endless technological revolutions? The possibility that we might not be able to do this reasonably is in itself frightening.

Assuming slowdown is unlikely and new big changes are just around the corner, what mistakes will we make? What if everything stays as it is now while the pace of change slows down?Will the slowing world be a better place?

Yes, probably. Emotionally, life may become closer to that of our hunter-gatherer ancestors than to the lives of our 20th-century ancestors. We do not know what will happen, but in order to achieve a better future, we must first imagine it. The slowdown means the end of pervasive capitalism. Capitalism could never last forever, as it was based on the expectation of ever-expanding markets and insatiable demand, creating such a peculiar concentration of wealth that it made democracy look ridiculous.

It’s hard for a shrinking and ageing population to make money.

It will be very difficult to sustain large economic inequalities during and after the slowdown. The less things change, the more difficult it will be to make money from a shrinking and aging population, a population that is more intuitive and not easily tempted by the ‘new’.

Most advertisements aim to convince us that we want things we don’t need; we should buy it, or at least covet it, and despair if we can’t even imagine owning it. However, as more and more people are studying psychology and social sciences, as well as having more advanced numeracy skills, it will become more difficult to fool the majority.

In a slower future, sleight of hand and psychological tricks won’t work because they won’t be new anymore, especially if the “new” is becoming less and less new due to the slowdown in technological innovation. The slowdown means that our institutions (universities, schools, hospitals) and homes (kitchens and bathrooms) will not change as much as they used to, but this will be unlike our attitudes which could change more quickly.

Slowing down means more time to question that our grandparents never had time to question because they were dealing with so many new things.

Slowdown requires products that last longer mean less waste. It means that many of the things that we now see as major social and environmental problems will not be a problem in the future.

Of course, we will have new problems, many of which we cannot even imagine right now. And of course always; We will continue to do what we did before, during, and after the speed age – to have fun and have fun with our friends and family.

What are the links to slowing down and sustainability? How do these two entities support each other?

Of course, people will also move in the future, they will change places. In a calmer and more rational world, they should have a lot more time to do it. But they will no longer have to relocate to where their business is or go far from a place that has become unproductive.

As is often written, we won’t have to spend so much time producing so many things of almost no real value. We will have more time to ourselves, but we will need to use this time sustainably – so there will be an ecotourism boom.

Tourism in the future will mostly take the form of ecotourism, just as paints in most countries are now mostly lead-free paint. One way to think of the current global economy is to see it as something rooted in the events of 1492. Since then, we have been globalising, and more and more people have been drawn into it.

In some ways, our economy and resources are similar to what happened to the land when you first farmed. The soil is quickly depleted and you cannot grow a crop. You get diminishing returns. Capitalism seems to have been such a learning process, rather than the final state. What’s next? We don’t know; we cannot say. But whatever it is, it will have to be sustainable. This is not a plea, just an observation.

Should deceleration be a state policy, and when should the decision to switch to deceleration be made?

Yes, some policy makers are better at doing this than others. In December 2019, the wealthy world’s most unequal countries were mostly ruled by far-right men: Donald Trump in the US, Vladimir Putin in Russia, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, Sebastián Piñera in Chile and Boris Johnson in the UK.

Simultaneously, however, women have been gaining power in more and more equal countries: Finland’s prime minister, Sanna Marin, of the Social Democratic Party, who took office a few years ago, was the most notable example. Marin subsequently led the country in coalition with Li Anderson (Left Alliance), Katri Kulmuni (Center Party), Maria Ohisalo (The Greens) and Anna-Maja Henriksson (Swedish People’s Party). Stop and think about how much has changed in such a short time, because when you look at it that way, one becomes more optimistic. Until recently, women were not even allowed to receive basic education.

Several male physicists and mathematicians developed the phase space diagrams used in the book shortly before the introduction of the first universal birth service in the 1870s to stop the most human aspect of slowing down, to aid the birth of fewer people. They did this at a time when a large part of human life was really accelerating. According to one 21st-century study of the rate of social change that chose fertility as the change to be measured, “interpreters often observe that the rate of social change is accelerating in the 20th century.”

Another study begins: “If the stability in life that facilitates a degree of control and planning is seemingly undermined, thus giving rise to feelings of social acceleration, I investigate its nature and how it manifests in its location before questioning why.” But we are not accelerating. If we feel that we are, it is time to change that feeling.

In which areas can it be done and after how long will the results take to arrive?

The slowdown is already happening, and in some cases has been going on for quite some time. Over the past 160 years, our population has doubled, doubled again, and then nearly doubled again. We have never seen such an increase in human population over such a small number of generations. We will not see it again. Our population growth rate is slowing down today.

Charles Darwin wrote in 1859 of “innumerable recorded cases of the astonishingly rapid growth of various animals under natural conditions, when conditions are favourable in two or three successive seasons.” Using examples ranging from tiny seedlings to gigantic elephants, he discussed situations in which exponential population growth rarely seen in nature has occurred. Indeed, the best example he could have chosen would have been his own species, humans, whose exponential growth has not been seen before and has just begun its worldwide proliferation.

Since 1968, 109 years after Darwin wrote these sentences, we began to slow down, and the results are already happening.

What do you think about the role of artificial intelligence in this equation?

Today we are told that artificial intelligence is our future, and there are widespread claims that computers could quickly think like us if they were fast enough, programmed well enough, or programmed themselves well enough. As we do, the way we do, and ultimately better than us. I clearly remember being told this when I first programmed a computer as a kid in the 1970s. Since then, the pace of progress in AI has been rather slow.

In my doctoral thesis in the 1980s, I mentioned it as slow as a mischievous sea slug, because at that time it was the only creature that was somehow simulated using a computer. No one has yet created a pet robot that realistically behaves like a real animal, let alone an artificial human. The rate of technological progress before the 1970s was remarkably rapid. But the later rate is surprisingly slow.

Artificial intelligence is still pretty artificial and not that smart.

The machine cannot know the moral truth.

It’s not because we’re great thinkers that people are so hard to imitate. Since we are not machines, it is very difficult to create an artificial mind. We think in very strange ways. Not necessarily good, fast, or clever ways, just weird ways… So a computer can be programmed to recognise license plates, then text, then words. Given enough source text that has been carefully translated by experts working specifically for European Union countries (so Google Translate works best for European languages), it can learn to translate between languages through “machine learning”.

But a computer cannot be built with a deep understanding of why it is wrong to let other people starve or to care about the long-term consequences of their actions. A computer can’t worry about climate change like a 15-year-old Swedish girl.

Think about moral judgements. William Armstrong’s tombstone in the churchyard in Rothbury has the inscription: “His scientific achievements have earned him worldwide fame and his great philanthropy the gratitude of the poor.”

There is no mention that he actually made his money through the manufacture and sale of weapons. And artificial intelligence today is far from imitating human interest in such vices, as it was when it was first invented. This morning I asked Alexa, the robot in my kitchen: “Why is it bad for people to starve?” “Hmm, I don’t know about that,” she replied. Google it and you might find an economist saying whether it makes economic sense to let people go hungry (and unfortunately someone probably made those calculations). ChatGPT only mimics.

The machine cannot intuitively know if something is morally wrong. You have to be human to know, treating other people as less human requires indifference – which some people can do wonderfully. It would be pretty hard to get a response other than explaining all this to an AI engine and parroting your own words to you. All ChatGPT gives you is the vulgarest of politically balanced answers, combining canned answers available on the internet. Imagination? No, it doesn’t have it.

What will happen in the future?

Try to imagine what your grandchildren might be worried about in 2222, when the global human population has been declining for decades, economic equality is high, and the planet is no longer warming or even cooling with current interglacial warming having ended. At some point before that year, sea levels will become more stable than they are today, although much higher than they are now.

Power supplies will be safe and largely non-polluting. While artificial intelligence can benefit, it will still be very artificial and not very intelligent. In this future, we will all be pretty well fed, but very few of us will be fat. So what should we worry about then? Whatever this is, it’s definitely going to be a major concern. To be human is to worry with the imagination; To always seek a utopia is to fear disaster.

‘Number growth’ will stop soon: The belief that we are being thrown rapidly into an unknown future is decreasing day by day; but we are just emerging from the dense fog of our bumpy past, and now we are beginning to see the clouds parting as our journey slows. There are beautiful seasons to see, but these are not fertile seasons in which our numbers, inventions, and total wealth increase exponentially. Because the increase in our numbers will stop very soon. The last few generations have seen a trajectory and many painful events involving the worst of all wars in terms of deaths and holocausts, and the most despicable of all human behaviour, including the planning and construction necessary for the mass nuclear annihilation of our species.

It is emphasised that after such an event that we have experienced globally since the beginning of the pandemic, nothing will be the same as before. Now that the pandemic is over, what do you think are the most important changes in the world since 2020?

The pandemic has made the slowdown that awaits us more obvious.

We still don’t travel by plane as much as we used to. Only a very small minority of us have flown on this planet – most people have never been on a plane, and nearly all of the children born this year will never fly. Most children in the world have never been and will never get on a plane. But the pandemic was the beginning of a slowdown in flight – this slowdown is still on the rise, but not as fast as in 2018 and 2019. The pandemic has made the slowdown that awaits us more obvious, and it’s something to be thankful for.

The alternative—an ever-increasing total human population, more economically divided societies than ever before, per capita consumption more than ever—could be a disaster. Without both population growth and economic growth, capitalism—the economic system we’ve become so used to as we can’t imagine the end of it—turns into something else.

To something much more stable and logical. It is impossible to know whether people will be happier in that future world. They may more often come face-to-face with the fact that we cannot find happiness by acquiring more possessions and having more exotic experiences. There’s a lot we don’t know. But at least we have to acknowledge that the slowdown is upon us and can now happen in many surprising areas.

Less destruction less poverty.

It may take some time for us to accept that we are now faced with fewer discoveries, fewer new mysteries, and fewer “big men”. But is this a very difficult bite to swallow? And we will see less despotism, less destruction and less poverty. For example, we will never again blindly believe in the “creative destruction” that twentieth-century economists foolishly praised at the height of the great acceleration.

It was the weird idea that things got better as companies went bankrupt, because only those firms that deserved to go bankrupt went bankrupt. This nihilistic rhetoric made sense according to the bizarre (but popular at the time) survival of the fittest theory of corporate evolution. The pandemic has only helped to increase the speed of slowdown. At the most basic level, fewer babies were born than predicted, both during and after the pandemic.

Next: In Turkish, from which the text above was translate by AI and only minimally corrected!

Danny Dorling: “Yavaşlama, yaygın kapitalizmin sonu demektir”

Danny Dorling, Yavaşlamak adlı kitabında hız çağının sonunu ele alıyor. İlerlemenin büyüsü altında kalan dünyada gitgide artan nüfus, iş gücü ve sermayesi karşısında “daha yavaş ilerleme” olgusunu farklı disiplinler içerisinde irdelerken gelecekten beklentiler doğrultusunda atılabilecek sürdürülebilir çözüm adımlarına dikkat çekiyor.

Dünya Gazetesi

YAYINLAMA27 Mayıs 2023

Günay DEMİRBAĞ

Hızla büyüyen dünyanın tükenmişlik sınırlarında seyretmesi nedeniyle uzun süredir konuşulan yavaşlama ve sürdürülebilirlik kavramlarını daha da gündeme taşıdı. Küresel çapta yaşanan ‘Yavaşlama’ konusunda sorularımızı İngiliz yazar Danny Dorling’e yönelttik.

Yavaşlamak derken neyi kastediyorsunuz ve dünyada ilk kez ne zaman yavaşlamak gerektiği düşünüldü açıklar mısınız?

Bugün yavaşlama (ilk olarak 1890’larda kullanılan, daha yavaş ilerlemek anlamında gelen bir kelime) birçok şeyi etkiliyor. Küresel olarak ilk kez 1968 civarında yavaşlamaya başlayan ve o zamandan beri yavaşlayan insan nüfusu artışı bağlamında görüldü. İnsan sayısındaki artış her yıl bir öncekine kıyasla daha küçük bir yüzdeye denk geliyor. Yakında daha küçük bir mutlak sayı olacak. BM projeksiyonlarına göre 2086’ya geldiğimizde sayımız her yıl düşmeye başlayacak ki bu da insanlık tarihinde bir ilk olacak. En azından bildiğimiz kadarıyla.

Yavaşlama her alanı etkiliyor

Nüfusumuzun yanı sıra küresel ekonomik büyümemiz ve inovasyon hızımız da düşüyor. Yavaşlama artık nüfus büyüme oranından çok daha fazlasını etkiliyor. Hayatımızın neredeyse her alanını etkiliyor. Mevcut yavaşlamamız, hızlanma beklentisine yönelik büyük bir meydan okumayı ve bilinmeyene doğru bir adımı temsil ediyor.

Hali hazırdaki inanç sistemlerimiz (ekonomik, politik ve diğerleri) ne ölçüde gelecekteki hızlı teknolojik değişim ve sürekli ekonomik büyüme varsayımları üzerine inşa edilmiştir? Bizi bekleyen yavaşlamayı kabul etmek zor. Henüz yavaşlamayan alanlar şunlar: karbon kirliliği, sıcaklık artışları ve üniversitede okuyan küresel öğrenci sayısı. Ancak bunlar da yakında yavaşlamaya başlayacak, bazıları diğerlerinden daha erken yavaşlayacak.

Bizi bekleyen yavaşlamayı kabul etmek salt fayda olarak gördüğümüz değişime, inovasyona ve keşfe ilişkin temel görüşümüzü değiştirmemizi gerektirecek. Bitmek bilmeyen teknolojik devrimler beklemeyi bırakmamız gerektiğini kabul edebilecek miyiz? Bunu makul bir şekilde yapamama ihtimalimiz başlı başına korkutucu. Yavaşlamanın olası olmadığını ve yeni büyük değişimlerin hemen köşede olduğunu varsayarsak hangi hataları yapacağız? Değişim hızı yavaşlarken her şey şu anda olduğu gibi kalırsa ne olacak?

Yavaşlayan dünya daha iyi bir yer mi olacak?

Evet, muhtemelen. Duygusal açıdan hayat, 20. yüzyıldaki atalarımızın hayatlarındansa avcı toplayıcı atalarımızınkine daha yakın hale gelebilir. Ne olacağını bilmiyoruz ama daha iyi bir geleceğe ulaşmak için önce onu hayal etmeliyiz. Yavaşlama, yaygın kapitalizmin sonu demektir. Kapitalizm, sürekli genişleyen pazarlar ve doyumsuz talep beklentisine dayalı olduğu ve servet kavramına demokrasiyi gülünç duruma düşürecek denli tuhaf bir yoğunlaşma yarattığı için asla sonsuza kadar süremezdi.

Küçülen ve yaşlanan nüfusun para kazanması zor

Büyük ekonomik eşitsizlikleri yavaşlama sırasında ve sonrasında sürdürmek epey zor olacak. Her şey daha az değişir hale geldikçe, daha sezgili ve “yeni”nin cazibesine kolay kolay kanmayan, gitgide küçülen ve yaşlanan bir nüfustan para kazanmak çok daha zor hale gelecek.

Çoğu reklam, bizi ihtiyacımız olmayan şeyleri istediğimize ikna etmeyi amaçlar; onu satın almalı ya da en azından ona göz dikmeli ve ona sahip olmayı hayal bile edemiyorsak umutsuzluğa düşmeliyiz. Bununla birlikte, gitgide daha fazla insan psikoloji ve sosyal bilimler okuduğu, ayrıca daha ileri aritmetik beceriye sahip olduğu için çoğunluğu kandırmak daha zor hale gelecektir.

Daha yavaş bir gelecekte, el çabukluğu ve psikolojik hileler işe yaramayacak, çünkü artık yeni olmayacaklar, bilhassa teknolojik inovasyondaki yavaşlamadan dolayı “yeni” olan gitgide azalıyorsa. Yavaşlama, kurumlarımızın (üniversiteler, okullar, hastaneler) ve evlerimizin (mutfaklar ve banyolar) eskisi kadar değişmeyeceği, ancak tutumlarımızın aksine daha hızlı değişebileceği anlamına gelir.

Yavaşlama, büyükanne ve büyükbabalarımızın yeni olan pek çok şeyle uğraştıkları için asla sorgulamaya zaman bulamadıklarını sorgulamak için daha fazla zaman demektir. Yavaşlama; daha uzun süre dayanan ürünler, daha az atık demektir. Şu anda toplumsal ve çevresel açıdan büyük sorunlar olarak gördüğümüz pek çok şeyin gelecekte sorun teşkil etmeyeceği anlamına gelir.

Elbette yeni sorunlarımız olacak ki bunların çoğunu şu anda hayal bile edemiyoruz. Ve tabii ki her zaman; hız çağı başlamadan önce, hız çağı boyunca ve sonrasında yaptığımız şeyleri yapmaya devam edeceğiz -arkadaşlarımızla, ailemizle keyifli vakitler geçirip eğleneceğiz.

Yavaşlamak ve sürdürülebilirlik bağlantıları nelerdir? Bu iki oluşum birbirlerini nasıl destekliyor?

İnsanlar elbette gelecekte de hareket edecek, yer değiştirecekler. Daha sakin ve daha mantıklı bir dünyada bunu yapmak için çok daha fazla vakitleri olmalı. Ama artık işlerinin olduğu yere taşınmak ya da verimsiz hale gelen bir yerden uzağa gitmek zorunda kalmayacaklar.

Sık sık yazıldığı gibi, gerçek değeri neredeyse olmayan bu kadar çok şey üretmek için bu kadar zaman harcamak zorunda kalmayacağız. Kendimize ayıracak daha çok zamanımız olacak, ama bu zamanı sürdürülebilir şekilde kullanmamız gerekecek -dolayısıyla bir ekoturizm patlaması yaşanacak.

Gelecekte turizm çoğunlukla ekoturizm şeklinde gerçekleşecek, tıpkı çoğu ülkede boyaların artık çoğunlukla kurşunsuz boya olması gibi. Mevcut küresel ekonomiyi düşünmenin yollarından biri, onu köklerini 1492’de yaşananlardan alan bir şey olarak görmektir. O zamandan beri, gitgide daha fazla insan içine çekilse de küreselleşmenin gerçekte ne olduğunu bilmiyoruz.

Zaman zaman, özellikle II. Dünya Savaşı’ndan sonra onu yönetmeye çalıştık. Bazı yönlerden ekonomi ve kaynaklarımız, ilk tarım yaptığınızda toprağa olana benzer. Toprak hızla tükenir ve mahsul yetiştiremezsiniz. Azalan getiriler elde edersiniz. Kapitalizm, nihai durumdan ziyade, böyle bir öğrenme süreci olmuş gibi görünüyor. Sırada ne var? Bilmiyoruz; söyleyemeyiz. Ama her ne ise sürdürülebilir olması gerekecek. Bu bir yalvarış değil, sadece bir gözlem.

Yavaşlama bir devlet politikası mı olmalı ve yavaşlamaya geçiş kararı ne zaman verilmeli?

Evet, bazı politika belirleyiciler bunu yapmada diğerlerinden daha iyi. Aralık 2019’da varlıklı dünyanın en eşitsiz ülkeleri çoğunlukla aşırı sağcı erkekler tarafından yönetiliyordu: ABD’de Donald Trump, Rusya’da Vladimir Putin, Türkiye’de Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Şili’de Sebastián Piñera ve Birleşik Krallık’ta Boris Johnson.

Bununla birlikte, eş zamanlı olarak gitgide daha fazla eşitliğin kazanıldığı ülkelerde kadınlar güç kazanıyordu: Finlandiya’da o ay göreve gelen yeni başbakan, Sosyal Demokrat Parti’den Sanna Marin bunun en kayda değer örneğiydi. Marin sonrasında ülkeyi Li Anderson (Sol İttifak), Katri Kulmuni (Merkez Parti), Maria Ohisalo (Yeşiller) ve Anna-Maja Henriksson (İsveç Halk Partisi) ile koalisyon halinde yönetti. Durup bu kadar kısa sürede ne kadar çok şeyin değiştiğini düşünün, böyle bakınca insan daha iyimser oluyor. Kısa zaman öncesine kadar kadınların temel eğitimi almasına bile izin verilmiyordu.

Birkaç erkek fizikçi ve matematikçi, kitapta kullanılan faz uzay diyagramlarını, yavaşlamanın en insani yönü olan daha az insanın doğmasını durdurmak için 1870’lerde ilk evrensel doğum hizmetinin getirilmesinden kısa bir süre önce geliştirdi. Bunu, insan yaşamının büyük bir bölümünün gerçekten hızlandığı bir zamanda yaptılar. Ölçülecek değişiklik olarak doğurganlığı seçen, toplumsal değişimin hızına ilişkin 21. yüzyılda yapılmış bir çalışmaya göre, “yorumcular, toplumsal değişim hızının 20. yüzyılda yükseldiğini sık sık gözlemliyorlar.”

Başka bir çalışma şöyle başlıyor: “Hayatta bir dereceye kadar kontrol ve planlamayı kolaylaştıran istikrar, görünüşte baltalanıyorsa ve bu nedenle sosyal hızlanma duygularına yol açıyorsa, bu durumun nedenini sorgulamadan önce doğasını ve bulunduğu yerde nasıl ortaya çıktığını araştırırm.” Ama hızlanmıyoruz. “Öyle olduğumuzu hissediyorsak, bu duyguyu değiştirmenin zamanı gelmiştir.”

Hangi alanlarda yapılabilir ve sonuçları ne kadar süre sonra gerçekleşir?

Yavaşlama hali hazırda gerçekleşiyor, hatta bazı durumlarda epeydir devam ediyor. Geçtiğimiz 160 yıl boyunca nüfusumuz ikiye katlandı, tekrar ikiye katlandı ve sonra neredeyse tekrar ikiye katlandı. Bu denli az kuşak sayısı boyunca insan nüfusunda böylesi bir artışı daha önce görmemiştik. Bir daha da görmeyeceğiz. Bugün nüfus artış hızımız yavaşlıyor.

Charles Darwin 1859’da “doğal şartlarda, birbirini izleyen iki veya üç mevsimdeki koşullar uygun olduğunda, çeşitli hayvanların şaşırtıcı derecede hızlı artışına ilişkin sayısız kayıtlı vaka” hakkında yazmıştı. Küçücük fidelerden devasa fillere kadar uzanan örnekleri kullanarak, doğada nadiren görülen üstel nüfus artışının meydana geldiği durumları tartışmıştı. Esasen seçebileceği en iyi örnek, üstel artış sayısında örneğine rastlanmamış ve dünya çapındaki çoğalmasına yeni başlayan kendi türü, yani insanlar olabilirdi. 1968’ten beri, Darwin bu cümleleri yazdıktan 109 yıl sonra yavaşlamaya başladık ve sonuçlar çoktan gerçekleşiyor. “Yapay zekâ halen oldukça yapay ve o kadar da zeki değil. “

Yapay zekânın bu denklemdeki rolü hakkında ne düşünüyorsunuz?

Bugün bize yapay zekânın geleceğimiz olduğu söyleniyor ve bilgisayarların yeterince hızlı olmaları, yeterince iyi programlanmaları veya kendilerini yeterince iyi programlamaları halinde hızla bizim gibi düşünebileceklerine dair yaygın iddialar var. Bizim yaptığımız gibi, bizim yaptığımız şekilde ve nihayetinde bizden daha iyi. 1970’lerde çocukken bir bilgisayarı ilk kez programladığımda bana bunun söylendiğini çok net hatırlıyorum. O zamandan beri yapay zekâdaki ilerleme hızı oldukça yavaş.

1980’lerde doktora tezimde ondan muzipçe bir deniz sümüklüböceği kadar yavaş diye bahsetmiştim, çünkü o zamanlar bilgisayar kullanılarak bir şekilde taklit edilen tek yaratık oydu. Henüz hiç kimse, bırakın yapay bir insanı, gerçekçi bir şekilde hakiki bir hayvan gibi davranan evcil bir hayvan robotu bile yaratmadı. 1970’lerden önceki teknolojik ilerleme oranı dikkate değer ölçüde hızlıydı. Ancak daha sonraki oran şaşırtıcı derecede yavaş.

“Makine ahlaki açıdan doğruları bilemez’’

İnsanların taklit edilmesinin bu kadar zor olmasının nedeni büyük düşünürler olmamız değil. Makine olmadığımız için yapay bir zihin yaratmak çok zor. Çok garip şekillerde düşünüyoruz. Mutlaka iyi, hızlı veya akıllıca yollar değil, sadece garip yollar… Böylece bir bilgisayar plakaları, ardından metni, sonra da kelimeleri tanıyacak şekilde programlanabilir. Bilhassa Avrupa Birliği ülkeleri için çalışan uzmanlar tarafından dikkatlice çevrilmiş yeterli kaynak metin verilirse (bu nedenle Google Çeviri, Avrupa dilleri için en iyi sonucu verir) diller arasında çeviri yapmayı “makine öğrenimi” yoluyla öğrenebilir.

Ancak bir bilgisayar, diğer insanların aç kalmasına izin vermenin neden yanlış olduğunu veya eylemlerinin uzun vadeli sonuçlarını umursamayı derinlemesine anlayacak şekilde inşa edilemez. Bir bilgisayar, 15 yaşında İsveçli bir kız gibi iklim değişikliği konusunda endişelenemez. William Armstrong’un Rothbury’deki kilise bahçesinde bulunan mezar taşında şu kitabe yer almaktadır: “Bilimsel kazanımları ona dünya çapında bir ün ve büyük hayırseverliği yoksulların minnetini kazandırdı.”

Gerçekte parasını silah üretimi ve satışı yoluyla kazandığından hiç söz edilmiyor. Ve yapay zekâ bugün, ilk icat edildiğinde olduğu gibi, bu tür ahlaksızlıklara yönelik insani ilgiyi taklit etmekten çok uzak. Bu sabah mutfağımdaki robot Alexa’ya sordum: “İnsanların aç kalması neden kötü?” “Hmm, onu bilmiyorum,” diye cevap verdi. Google’da arattığınızda, insanların aç kalmasına izin vermenin ekonomik açıdan mantıklı olup olmadığını söyleyen bir ekonomist bulabilirsiniz (ve ne yazık ki biri muhtemelen bu hesaplamaları yapmıştır).

Makine, bir şeyin ahlaki açıdan yanlış olup olmadığını sezgisel olarak bilemez. Bilmek için insan olmanız gerekir, diğer insanlara daha az insan muamelesi yapmak umursamamayı gerektirir –ki bazı insanlar bunu harikulade yapabiliyor. Tüm bunları bir yapay zekâ motoruna açıklayıp size kendi kelimelerinizi papağan gibi tekrar etmesi dışında bir karşılık almak epey zor olurdu. ChatGPT’nin size verdiği tek şey, internette mevcut olan hazır cevapları bir araya getiren, politik olarak dengeli cevapların en bayağısıdır. Hayal gücü? Hayır, buna sahip değil.

Gelecekte neler olacak?

Küresel insan nüfusunun onlarca yıldır düştüğü, ekonomik eşitliğin yüksek olduğu ve gezegenin artık ısınmadığı, hatta mevcut buzullar arası ısınmayla birlikte soğumaya başladığı 2222’de torunlarınızın ne için endişelenebileceğini hayal etmeye çalışın. O yıldan önce bir noktada, deniz seviyeleri şimdikinden çok daha yüksek olmasına rağmen bugünkünden daha istikrarlı hale gelecek.

Güç kaynakları güvenli olacak ve büyük ölçüde çevreyi kirletmeyecek. Yapay zekâ fayda sağlasa da hâlâ epey yapay olacak ve pek de zeki olacağını söyleyemeyiz. Bu gelecekte hepimiz oldukça iyi besleneceğiz ama çok azımız şişman olacak. Peki o zaman ne için endişeleneceğiz? Bu her ne ise, kesinlikle büyük bir endişe kaynağı olacak. İnsan olmak, hayal gücüyle endişelenmektir; daima bir ütopya arayışında olmak, felaketten korkmaktır.

Sayı artışı yakında duracak

Bilinmeyen bir geleceğe hızla savrulduğumuz inancı gitgide azalıyor; ama inişli çıkışlı geçmişimizin yoğun sisinden daha yeni çıkıyoruz ve şimdi, yolculuğumuz yavaşlarken bulutların aralandığını görmeye başlıyoruz. Görecek güzel mevsimler var ama bunlar, sayımızın, icatlarımızın ve toplam zenginliğimizin katlanarak arttığı verimli mevsimler değil. Çünkü sayımızın artışı çok yakında duracak. Son birkaç kuşak, ölümlerle soykırımlar açısından tüm savaşların en kötüsünü ve türümüzün kitlesel nükleer imhası için gerekli planlamalar ve inşaları da dahil olmak üzere tüm insan davranışlarının en aşağılık olanlarını içeren bir gidişat ve birçok acı verici olay gördü.

Pandeminin başından beri, küresel çapta deneyimlediğimiz böyle bir olaydan sonra hiçbir şeyin eskisi gibi olmayacağı vurgulanıyor. Artık pandemi bittiğine göre, sizce 2020’den beri dünya genelinde yaşanan en önemli değişiklikler neler?

Pandemi, bizi bekleyen yavaşlamayı daha açık hale getirdi.

Halen eskisi kadar uçakla seyahat etmiyoruz. Bu gezegende sadece çok küçük bir azınlığımız uçtu – çoğu insan asla uçağa binmedi ve bu yıl doğan çocukların neredeyse tamamı asla uçamayacak. Dünyadaki çoğu çocuk hiç uçağa binmedi ve binmeyecek. Ancak pandemi, uçuşta yavaşlamanın başlangıcı oldu – bu yavaşlama halen yükseliyor, ancak 2018 ve 2019’daki kadar hızlı değil. Pandemi, bizi bekleyen yavaşlamayı daha açık hale getirdi ve bu müteşekkir olunacak bir şey.

Alternatif -sürekli artan toplam insan nüfusu, ekonomik olarak her zamankinden daha fazla bölünmüş toplumlar, kişi başına her zamankinden daha fazla tüketim- bir felaket olabilirdi. Hem nüfus artışı hem de ekonomik büyüme olmadan, kapitalizm -sonunu düşünemeyeceğimiz kadar alıştığımız ekonomik sistem- başka bir şeye dönüşür.

Çok daha istikrarlı ve mantıklı bir şeye. İnsanların o gelecek dünyada daha mutlu olup olmayacağını bilmek imkânsız. Daha fazla mülk edinerek ve daha egzotik deneyimler yaşayarak mutluluğu bulamayacağımız gerçeğiyle daha sık yüz yüze gelebilirler. Bilemeyeceğimiz çok şey var. Ancak en azından yavaşlamanın üzerimizde olduğunu ve artık pek çok şaşırtıcı alanda gerçekleşebileceğini kabul etmeliyiz.

Daha az yikim daha az yoksulluk

Artık daha az keşif, daha az yeni gizem ve daha az “büyük adam” ile karşı karşıya olduğumuzu kabul etmemiz biraz zaman alabilir. Ama bu yutulması çok zor bir lokma mı? Hem daha az despotluk, daha az yıkım ve daha az yoksulluk göreceğiz. Yirminci yüzyıl iktisatçılarının büyük hızlanmanın zirvesinde aptalca övdüğü “yaratıcı yıkım”a bir daha asla körü körüne inanmayacağız mesela.

Firmalar battıkça her şeyin daha iyiye gittiğine dair tuhaf bir fikirdi bu çünkü sadece batmayı hak eden firmalar iflas etti. Bu nihilist retorik, şirket evriminin tuhaf (ama o zamanlar popüler olan) en güçlünün hayatta kalması teorisine göre mantıklıydı. Pandemi olsa olsa yavaşlama hızının artmasına yardımcı oldu. En temel düzeyde, hem pandemi sırasından hem de sonrasında tahmin edilenden daha az bebek doğdu.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published on-line click here.

The cover of “Slowdown”, Turkish Edition

May 26, 2023

The long shadow of the cost of living emergency

In ‘The long shadow of the cost-of-living emergency’, Amy Baker and Hannah Paylor revealed that: one in six people by early 2023 were less able to exercise, two in six less able to afford a healthy diet, and three in every six much less able to partake in the norms of society than they were just a year ago. Eating out with friends or family is no longer a sensible option for most. The cinema has become unaffordable to half of society.

At the extremes, a growing number in the most recent winter talked of being ‘freezing cold to the point of feeling ill… [too] scared to turn on the heating.’ Corroborating the findings of the Carnegie work, the 2023 UK Living Standards Report from the Resolution Foundation showed that most children with a brother and a sister (two siblings) in the UK now go hungry at least once a week.

Even the well-off are now affected. More than a fifth of people in families with a household income of £70,000 or more say they are now finding it hard to maintain a healthy diet as the cost of food, rent or mortgage, fuel and many other essentials soar.

In mid-2023 there is no sign of prices falling, just a vague hope that soon they will not rise much higher. More people are becoming physical ill. Anxiety rises. Increasing numbers of adults are saying: ‘I can barely afford to exist.’ Families with children are especially badly impacted.

Two thirds of parents say they are less able to participate in leisure activities in 2023 as compared to 2022, which will include taking their children on an annual holiday. Even before the cost-of-living crisis began, more than a third of all British families no longer had an annual holiday because they could not afford one. This has been the case for at least twenty years, as the government’s annual ‘Household Below Average Incomes’ report regularly reveals in a story that is now such old news that it is hardly ever reported.

Almost no one believes that is acceptable and a majority of all adults in all families earning less than the top 1% believe that ‘the government is offering too little support to help people through the rising in cost of living’. Only people in the very richest of families, with household incomes of over £150,000, are home to a minority of adults not dissatisfied by government. However, even two in every five of them are now sympathetic to the need for action.

Illustration in Dorling, D. (2023) The long shadow of the cost of living emergency, Carnegie UK Trust, May 23rd

The consensus is now so strong that it is likely that government will act further than it has done to date.

“At Carnegie UK we are advocates for collective wellbeing. This is achieved when everyone has what they need to live a good life, individually and together. As a social change organisation, we are concerned by the implications of rising living costs for tackling poverty and reducing inequalities; the quality of our relationships; and the extent to which we are able to exercise individual and collective power over our own lives.”

Read the report here

Data used in the graph above is taken from the full YouGov dataset, commissioned by Carnegie UK. If you’d like to learn more or see the full dataset, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with Hannah Paylor.

See: https://www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/publications/the-long-shadow-of-the-cost-of-living-emergency/

For a PDF of this article or link to where it was originally published click here.

Sir, Is Lord Sumption aware that the Roundheads won?

In Response to: Oxford Magazine, No. 452, 0th Week, TT, “The New Roundheads”

Sir, Is Lord Sumption aware that the Roundheads won?

Danny Dorling

St Peters College

Which elicited this reply in the next issue of the Magazine.

Sir – Danny Dorling (Letters, Oxford Magazine, No. 453, Second Week, Trinity Term 2023) could usefully extend his thinking. The Roundheads, having won the Civil War, then managed to cling to power for barely an arid decade. In 1660 Restoration of the monarchy was followed immediately by foundation of the Royal Society, along with initiation of a new golden age of English literature, philosophy, music and the performing arts, comparable to that of the Tudors.

The Great Plague and Great Fire of London (1666) were tragedies along the way, but did not overshadow the cultural achievements.

In 2023 the challenge going forward is to ensure that Irene Tracey’s assumption of office proves likewise to be a Restoration not merely of approaches to the Vice-Chancellorship, but of academic priorities in the governance of the University.

Yours sincerely,

Peter Oppenheimer

Christ Church

I decided that discretion might possibly be the better part of valour, and did not reply in turn.

There is much that could be said about arguments which appear superficially clever, but are not bright.

On the ‘golden age’, said to have begun after 1660, the views of people from elsewhere in the world might well be worth extending our thinking to, including those places not directly under the rule of the newly golden lands, such as China.

Many billions of people had their destines hugely altered by those few who thought themselves so very superior to all others around them.

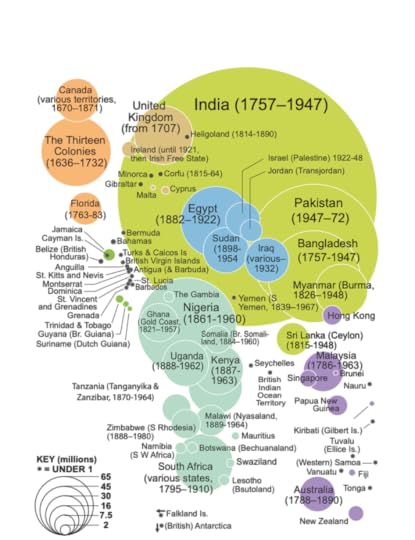

[Below – a map of the extent of the British Empire. much of a Caribbean was initially, or mostly ‘settled’ at the start of the ‘golden age’, and a link to where these letters were originally published, which was in response to this lecture.]

The demographic extent of places that were once part of the British Empire, rough dates of capture/independence

For a PDF of this short article or link to original place of publication click here.

April 28, 2023

Most people in the UK now share Robert Owen’s views

From 1798 to 1822 Britain suffered it longest ever fall in wages and a huge drop in living conditions due to prolonged wars in Europe alongside the early effects of new technology and industrialization. This was a 24 year record which will only be broken if real wages do not recover to the levels the reached in 2008 until after 2032. That is possible very possible – but it can be averted.

Prolonged cost-of-living crises, coupled with high inequality, have often brought about profound change. In 1817, after almost two decades of this national suffering, the Welsh business man, Robert Owen, turned to what was then called socialism. On March 12th he wrote to the chair of the House of Commons committee discussing the Poor Laws. Owen outlined a ‘New View of Society’ to the committee.

Owen appealed to the self-interests of the new capitalists. He proposed that in future life in Britain would better be organised along communal lines, with communities the size of the model village of New Lanark in Scotland. Robert Owen had become the manager of the cotton mill in that village in 1800. He had slowly come to understand that if things carried on as they were, this would end in disaster. Life expectancy fell.

Slave picked and planted cotton had become more expensive to import into Britain after the American plantation owners won their independence. The British mill owners tried to minimise their potential loses by making their workers toil harder for less reward. The mill owners left labourers to fend for themselves and argued for small government and low taxes.

Robert Owen suggested that communities should be collectively organised; that education should be provide by the community, beginning with free child care for all from the age of three. These communities would work together, aided by government, to ensure that standards of living rose and that life could be enjoyed. Ideas like his spread, but it took time for them to be enacted. The Poor Law he so opposed was not abolished until 1948.

From 1921 to 1931 Britain suffered its next longest fall in wages. The Prince of Wales met hungry miners in 1929. There had been a general strike, then a banking crash and mass unemployment. Inequality was again at an all time high. Most of the rest of the colonies were followed the United States and fought for independence. Ireland split off. Britain was becoming poorer again. Inequality in the UK began to fall. The rich were being taxed more than they ever had been before. Greater changes then came in the 1940s and 1960s in a form that Robert Owen might well have recognised as mirroring many of his ideas (including establishing playgroups).

From 2008 onwards, Britain suffered its next longest fall in wages. Scotland introduced new Child Payments and in November 2022 increased them to £25 per child per week aged 16 below, for all children living in families in receipt of Universal Credit or other state benefits (what could be thought of as yet another new Poor Law). Although the Scottish Child Payments were entirely affordable, Scotlands’ other ambitions to be a better country with free university education, a high quality health service, and good housing for all, were not achievable given the funding existing arrangements with Westminster. By 2020 it became obvious it would soon become untenable for Scotland to remain in the Union.

But what of Robert Owen’s dream of quality childcare and pre-school education? In 2023 it was revealed that the average hourly pay for people looking after children in our nurseries is now only £7.42. That is much lower than the minimum wage because of sexism. Almost all early years workers are women. Many are classed as apprentices and so can be paid lower than the national minimum wage.

In April 2023 the minimum wage was £10.42. It was only £10.18 for 21-22 year olds; £7.49 for 18-20 year olds; and just £5.28 for 16-17 year olds. The national minimum wage for apprentices is even less: £4.81 per hour. Should you wish to compare this to what you were paid when you were young, that wage is the equivalent of receiving the following hourly pay in the past:

2010: £3.40

2000: £2.76

1990: £2.12

1980: £1.22

1970: 38p

1960: 26p

1950: 18p

1940: 11p

1930: 9p

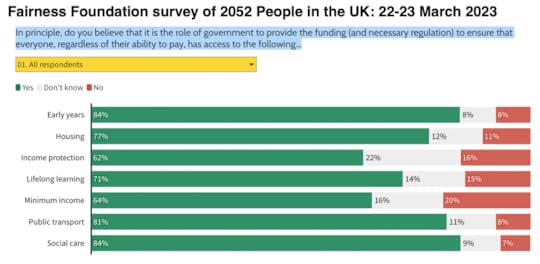

A few weeks later, the Fairness Foundation reported that when polled, more than four in five people in Britain agreed that the government should fund minimum levels of provision for social care (84%); for good quality childcare and pre-school education (84%); and ensure cheap public transport (81%). More than seven in ten agreed that government should provide the funding to ensure basic decent provisions in relation to social or rented housing (77%); and lifelong learning (71%); and more than three in five agreed that the government should provide a to minimum income (64%); and also that people who lose their job should be paid a percentage of their income by government to help them get back to work (62%).

Fairness Foundation Survey: https://fairnessfoundation.com/role-o...

In their press release, the Fairness Foundation explained that a shift towards huge popularity for these stances began long before 2023. That shift was now imbued in many of those who were doing well of themselves too. The economist, Minouche Shafik, then Director of the London School of Economics (LSE), a Board Member of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a former the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, had written a book: ‘What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract’, back in 2021, and the Foundation cited that as an example of how these beliefs were becoming much more widespread.

This trend is accelerating, in 2023 Daniel Chandler, an economist and philosopher based at LSE, published a book titled ‘Free and Equal: What would a fair society look like? The former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane greeted its publication as ‘energising and timely’. David Miliband, who had once been Britain’s Foreign Secretary, claimed it was: ‘clear, brave and compelling’. Rowan Williams, a past Archbishop of Canterbury, described it as: ‘exceptional’. The national treasure, Stephen Fry, summarised Free and Equal as: ‘…timely, wise, authoritative and clear’. Minouche Shafik urged people to: ‘Read Free and Equal and feel hopeful about the future.’

So what was in the book that had so excited these luminaries? It is possible that some of them did not read through to the latter pages, but maybe most of them had? The second half of his book is better than the first. In it Daniel Chandler writes approvingly of how Belgium limits the amount any individual can donate to a political party to €500 per year. He suggests that it should be a little less than that, with the state matching personal donations or even exceeding them.

Chandler writes in supportive terms about the introduction of a Universal Basic Income. He suggests that there is no evidence of any economic detriment from very high taxes, although he is unsure of whether tax rates of over 75 per cent on incomes of over $500,000 a year might encourage tax avoidance. He describes inheritance taxes for billionaires of 80 to 90 per cent that should be a first priority and shows that – combined with decent income taxes on capital – ‘a seemingly low annual wealth tax of 1-2 per cent could see some people paying most if not all of their capital income on taxes’ (page 238).

Why were so many of the British great and good drawn to these suggestions, people who had not advocated such policies so vocally before 2023? The answer might be that they were simply now fitting in better with the common attitudes of the rest of society. Our times are changing rapidly. Chandler suggests that his ideas are not socialist. But socialism has many meanings. At its heart it means to be social. Robert Owen, on his death bed in1858, claimed: ‘My life was not useless; I gave important truths to the world, and it was only for want of understanding that they were disregarded. I have been ahead of my time.’

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here

What would it take to persuade Rishi Sunak to join the Patriotic Millionaires?

I suspect they would agree to him joining, were he to ask. He is, after all, both patriotic and a multi-millionaire. I believe that he could understand their arguments, should he wish to. However, he would have to discard some of the beliefs he has picked up over the years, possibly from as early as his school days. That is difficult for anyone to do. Sunak has written three publications that help explain where he is coming from: A Portrait of Modern Britain (2014), A New Era for Retail Bonds (2017) and The Free Ports Opportunity: How Brexit Could Boost Trade, Manufacturing and the North (2018). He would have to rethink a lot of what he wrote and believed then to be persuaded.

However, the countries of the UK have changed greatly since he wrote those tomes. In 2023, a majority of children in larger families in Britain were going hungry ever month. Sunak may begin to realise that something has gone badly wrong, and that the promises that we would one day reach the sunlit uplands – the promises that his party have given every year from 2010 onwards – were false promises. He may be persuaded by the evidence and do the maths.

Ultimately, it is down to his aspiration. Does he aspire to be to be the kind of Conservative Prime Minister who is remembered, such as Disraeli or Macmillan, for moving towards a one-nation conservatism, in outcome and not just in rhetoric? Or would he be satisfied with being a footnote? Most past Conservative Prime Ministers are no longer remembered. Most are merely footnotes.

Sunak’s one great skill, where through real work experience he is far more qualified than any previous Prime Minister has ever been, is that he understands what would be required to tax the wealth and income of the rich properly and prevent them using loopholes to evade such action. Why waste such a talent?

What role do you think land value taxation could play in helping to resolve the housing crisis, especially the problem of ever-increasing house prices?

Even in a society without land taxes, house prices are never ever-increasing. The best long term data series that demonstrates this is from the Netherlands.

The longest house price series in the world (this graphic is from the book ‘Slowdown‘).

However, without land taxation (and other forms of wealth regulation), a society is doomed to keep repeating the spiralling booms and crashes of the past. The Dutch in previous centuries have demonstrated to us what a free market achieves and how inefficient such a market is where housing is concerned. Countries such as Austria that better regulate their housing have better housed populations. The USA has some of the worst housing outcomes in the rich world. Seventy years ago the UK was the envy of the world in terms of its housing policies because of what those policies were achieving.

Land taxation can be a part of that solution. One great advantage of land is that you cannot hide it. Again, Mr Sunak’s super power, his special skills, could be harnessed to address this problem. He has greater experience than any other Member of Parliament concerning the ownership of multiple valuable homes and other assets, including owning a very large property in North Yorkshire.

It may sound ridiculous to suggest that he might apply his skills in this area; but perhaps one reason why Conservative party members did not vote for him to be their leader was that some of them realised that he knows, should it be required, how what may have to be done can be done. He may not like the idea, but people can learn and begin to question their instincts. It was mostly Conservative Prime Minsters that were in power for the period from 1920 to 1970 when Britain last became so very much more equal. They may not have liked it, but in various ways they aided it, because there was no other acceptable option.

Would a land value tax not lead to increased food prices if most farmers own their land? Or should it only apply to residential land?

A land value tax should apply to all land. Once you begin to introduce loopholes, people will start to claim that the gardens of their Mayfair mansions are farms. The value of agricultural land without development permission tends to be very low in comparison to other land, so the tax would be very low too. The price of our food has little to do with British farmers. It did not rise by a fifth in the last twelve months because we had bad harvests in Britain. Other countries in Europe successfully control the food prices people have to pay. The Greeks even do this on food sold on their beaches and in other public places. If people ever tell you that something is not possible, first look to see what is happening elsewhere in Europe and then ask: “if it is possible there, why is it not possible here”?

How can the law be changed so that the wealthy are subject to it in exactly the same way as people with less wealth?

That would best be done if someone who knew the wealthy well was involved in drafting the law. Similar things have been achieved in many impressive ways in the past. For instance, when the National Health Service was created doctors were, at first, offered the salaries that they had been reporting to the tax authorities. When they complained that they could not live on such little money, they were offered a bit more. However, the minister, Bevan, did not publicly shame them, instead he said that he had “stuffed their mouths with gold”, which may have made them feel more respected.

Wealth taxes can be enforced simply by changing the law to state that you do not own an item, land or shares, that you do not pay the proper tax on. People are very keen to pay stamp duty on houses because otherwise they do not own their home. One of the most effective ways of changing the law so that the wealthy pay their taxes is to do what is done in some Nordic countries where the tax that everyone pays is published annually and anyone may view it. You can easily discover if your neighbour with three very large cars outside their property is declaring very little income. Others will be nosey but they may choose to say nothing. However, wealth tax dodgers do tend to make annoying neighbours; and even the thought of possibly being investigated tends to encourage the wealthy to be cleaner.

Imagine that any of your friends, neighbours, work colleagues, ex-partners, annoyed siblings, or other rivals might be tempted to point out to the authorities that you appear to be stealing from the people (evading tax). Such openness may be impossible to imagine ever coming to Britain; but have you ever stopped to wonder what the sunlit uplands actually are? Sunlight is the best disinfectant; ultimately, it is transparency that eventually ensures that the wealthy are subject to laws, such as on taxation, as much as the rest of us.

There are many other ways in which the wealthy can abuse the law: malicious prosecutions for libel and slander are two examples. In the end, the wealthy are treated much more like other people when they are less wealthy. In Britain they became dramatically less wealthy one hundred years ago. In the decades that followed most could soon no longer afford servants. Hardly anyone ever complained that they, or their children, could not be servants.

Would you ban private schools to achieve social justice?

No, because it is not necessary. Finland, one of the countries with the best state education systems in the world, still has a few private schools. It does not have many such schools, because it makes very little sense for a parent to send their child to one. But it is a useful check on the state system to allow private schools to continue so that you can monitor the numbers going, and then know if you might have a problem in the state sector if that number rises.