Danny Dorling's Blog, page 6

October 11, 2023

The souls of the people of Oxford

Something was done differently on the lands of the University of Oxford during the exceedingly long summer vacation of 2023. Something that had not happened in many a year. Someone, or possibly, a group of someones, made the right call. Our tale concerns river banks, and whether they are crumbling, along with bridges and local participants; including Mole, Ratty, many young swans, and at least one otter. Old Badger was unsure whether it was wise to allow the stoats and the weasels such leniency, but relented. Toad, at first confused over the fuss, slowly came to realise that being seen as aloof, tooting as he passed the lower orders in his car, might no longer be a good look.

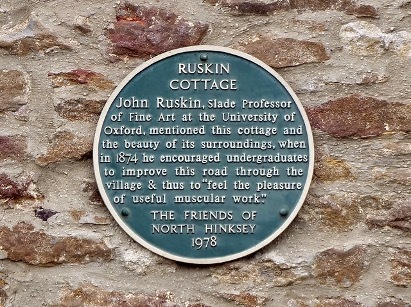

One of the two foot and cycle bridges over the Cherwell prior to 2023 repair.

The events took place not far from the J.R.R. Tolkien bench in the University Parks, and they concerned, above all else, children. What was to happen to the children if access changed?

Children’s stories, when told well, are of jeopardy, suspense and excitement. However, because you are not a child, I will tell you now that this story turns out well in the end. At the least, I hope it does, as the story is not over yet. It continues into the short Michaelmas term, because the bridges it concerns are still shut and the diversion I will tell you of remains in place. It will not be over until a great many years have passed, because it is the part of a much longer story, of how a city and its university changes. Of how ostensibly small things do really matter.

Our story begins many centuries ago, with the seizing of lands, and their dubious transfer of ownership. Its long history concerns the growth of empires and how the most insignificant of river crossings, a ford for oxen became what it is today. But for now let’s skip all those centuries and begin, only 150 years ago, in 1873, when a young man, studying in Dublin decided to apply for the demyship to attend Magdalen College, Oxford. He won the funding and so, in the autumn of 1874, came up to read Greats. His name was Oscar.

In those days it was far harder to traverse some parts of Oxford than it is now, but much easier to move between other parts of the city. To enter the city from the east, if not traveling on the main road, you would travel past the newly built Somerset public house,1 and use the ferry at Marston (marsh town).

To enter the city from the west, if not travelling on the main road, you would have taken a causeway through the often-flooded fields to the Fishes pub, and then used the ferry at the back of the pub to cross the Hinksey stream. Willow Walk would not open until the 1920s, and the route via the Fishes was in disrepair.

It was a time of renewed public spiritedness. Change was in the air. The Slade Professor of Art, John Ruskin had recently established his School of Drawing and Fine Art. He gained national notoriety, and much later a plaque, when he directed his students to repair the road leading to the Fishes ferry. This was both for the common good, and so that the students should each become a little more individually buff, through exercising their muscles.2

Sign at the site of the public spirited works of undergraduates in Oxford in 1874.

Among the many young men Ruskin enrolled was Oscar, who was a little wild. The high-ups were not amused, and the episode was recorded in the chronicles thus: ‘Most controversial, from the point of view of the University authorities, spectators and the national press, was the digging scheme’ not just because it was encouraging the youngsters to use their brawn, rather than direct the labour of others, but because of what effect such activities had on the young men. The chronicle continued: ‘The scheme was motivated in part by a desire to teach the virtues of wholesome manual labour. Some of the diggers, who included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin’s future secretary and biographer W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience: notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen. It helped to foster a public service ethic that was later given expression in the university settlements, and was keenly celebrated by the founders of Ruskin Hall, Oxford.’3

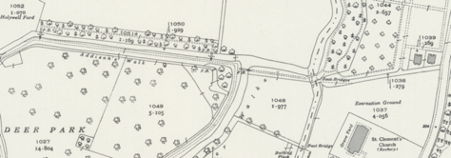

Inset of larger map (reproduced below) showing Addison’s walk and the footbridge behind St Clement’s Church

It can be a dangerous thing, being generous to others. Who knows where it might lead? Once you begin where might it end? Oscar Wilde went on to achieve great things, including writing the essay from which the title of this short story is derived. He was also treated with evil malice. However, Oxford was changing, the country was changing, the world was changing. But why did these fine young men not do their manual work nearer to their colleges? One answer, illustrated by the map above, was that they did not need to. At that time there were public pathways through Magdalen, but, sadly no longer.

There was a bridge across the Cherwell river, not just the bridge that bore the name of Wilde’s college, but dozens of other bridges, and a great many ferries as well. There was a bridge just south of St Clements church (the footings remain today), another just north of the bridge, a third at King’s Mill, a forth crossed from Magdalen School into the land between the rivers just south of Magdalen bridge. Take that route, and then the river could be crossed by two ferries into either Merton’s field or Christ Church meadow. The Cherwell already had a huge number of crossings, which was why Wilde found himself digging out and laying a route for the public to use, in Hinksey.

There was another ferry just 100 yards south again, and many more north of Magdalen College allowing the public to walk across college lands. The penny-farthing had only been invented in 1871, and no one cycled. I would include more maps here, but space is limited. Don’t fear, you can explore the past until your heart is content, by zooming into the wonderful interactive map that the National Library of Scotland now provides, free of charge. Via the Internet anyone can now see how the ancient rights of way cut through the colleges without having recourse to a map library.4 You can change the dates of the map to see when each bridge was removed – because almost all of them, eventually, were closed. Apart from Magdalen bridge itself.

When Oxford became the home of the new motor car, foot and by now some cycle bridges, the punt ferries and public access over college land were mostly consigned to the past. We too easily forget that, before the car, it was the bicycle that made Lord Nuffield his first fortune.

Along with the new cars came buses, which did for the trams that used to run through Oxford. Lord Nuffield was a cunning man and had a financial interest in the buses, but don’t let’s go down that dark track. Instead, let’s just remember that once Oxford had so many bridges and ferries crossing the rivers because people mostly walked and (later) cycled to work along convenient desire lines. Local people continued to mostly walk or cycle in the 1960s and 1970s. The university barred students having cars in Oxford in 1968. Their cars were sometimes made by local men, almost all of whom cycled to work.

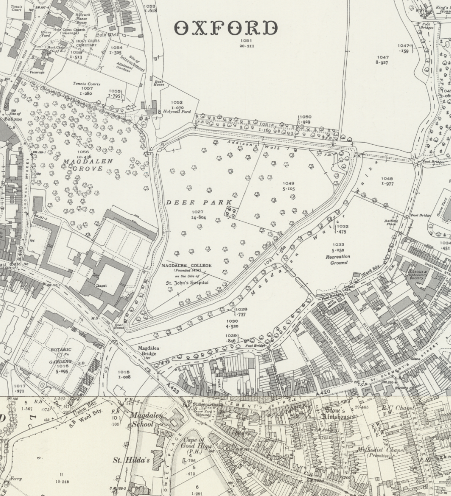

The crossings of the Cherwell in Central Oxford, circa 1873

Oxford University was also changing radically in this period. In 1873, Annie Rogers won first place in Oxford’s senior local exam list. Both Balliol and Worcester offered exhibitions (funding) for such an achievement, but not for a woman, because that was against the rules. Rules exist for a reason, to be changed when the time is right. Annie campaigned for open and full membership of Oxford University for women. She won the right to be awarded a university degree in 1920 and became the university’s first female graduate. In 1937, on her way to an evening lecture, she was killed when hit by a lorry on St Giles’.5 She also has a blue plaque.

Annie’s Plaque

Sadly, our story now turns down a darker road. The University was also becoming more insular. In 1908 Kenneth Graham explained what can and cannot be said about such matters: ‘The Mole knew well that it is quite against animal-etiquette to dwell on possible trouble ahead, or even to allude to it; so he dropped the subject.’ I have not the space to detail it here and it may be thought impolite, so it may be best to drop the subject. But should you want to know why the last alternative routes were shut, the bridges closed, and one college even built a moat around its grounds in the 1980s, then turn to R. W. Johnson’s account: ‘Look Back in Laughter: Oxford’s Postwar Golden Age.’ Published in 2015 by the one-time Bursar of Magdalen it triggers a warning for our more enlightened times today. Alongside some hurtful comments about local children in Oxford, it tells of why those public routes over college land were shut to keep the children out.6

Our story twists and turns: there was some progress in more recent times. It was not always unrelenting bad news. Two new bridges, Lemond and Fignon, were built to create a new route to alleviate the harm caused by closing so many public routes through Oxford. Whoever named the bridges (around 1990) had a sense of humour: ‘In 1989 Laurence Fignon, after 3,285 km of cycling and 21 stages plus a time trial, lost the Tour de France by 8 seconds to Greg LeMond. This is the smallest margin in the history of the Tour. And as the bridges are separated by an 8-second cycle ride someone had the whimsical idea of naming them after the two rivals.’7

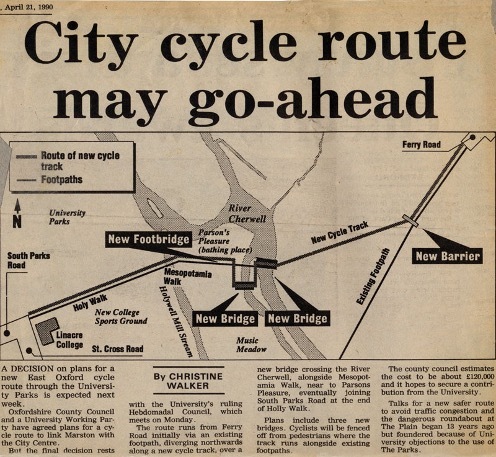

On 21 April 1990 the Oxford Mail announced that an imminent decision was about to be made by the University’s Hebdomadal Council on a new cycle track to be laid across the University Parks with a tarmacked section placed over the River Cherwell meadows.8

The newspaper article ended:

‘Talks for a new safer route to avoid traffic congestion and the dangerous roundabout at the Plain began 13 years ago but floundered because of University objections to the use of The Parks.’

Those talks had begun in 1977. Look closely at the map and you will see that one bridge was originally planned to be set back from the other. This was so that the genitalia of the dons sunning themselves on Parsons Pleasure would not be visible to lady cyclists riding by on that bridge. In the end, nude male-only bathing was brought to an end in 1991 and the path opened with the two bridges aligned. Old Badger may not have approved, but rules exist to be changed.

And this brings us, almost up to the present day. Even in some of the University’s darkest days of closing itself off, the provision of the new track was possible, and the ending of legal flashing by the equivalent of today’s associate professorship was banned. However, after the routes across the colleges and rivers were cut off, new signs began to appear, almost everywhere. More and more signs instructing people to stay out, or if they come into a particular area, to then behave in a certain way. Civility was to be enforced by edict.

In 2022 cyclists expressed their displeasure at the ‘ridiculous and petty’ signs banning bikes in Oxford University Parks. A new sign had just been erected replacing a slightly less offensive one. Below the sign was a notice, printed upon a background of Oxford Blue, and embossed with the University Crest. It informed the reader, standing in University Parks, that ‘CCTV images are being monitored and recorded for the purposes of crime prevention, detection, and public safety. This scheme is controlled by University of Oxford Security Services. For more information call 01865 272944.’

It was kind of them to provide a telephone number, one now spread far and wide by the photographs of the sign ‘going viral’. Interested cyclists from around the world phoned it to ask why pushing a bike was so frowned upon. The Radio 2 presenter, Jeremy Vine, labelled the signs ‘disgusting’. The cyclist who took the photograph reported: ‘this has annoyed me before and it annoys me now. How petty, discriminatory and inaccessible is Oxford University that they don’t even allow cycles to be pushed through Oxford University Parks? Ridiculous restriction in the so-called cycling city.’

Sign erected in the University Parks in 2022.

One commentator did point out that the red circle means ‘not allowed’, and the bar through it means an end to that restriction, so the sign actually implies the end of a no cycling area. Another wondered what would occur were you questioned by a University security official, who presumably had been instructed to give you a sound ticking off should you be found transgressing. What powers did they actually have? To look very upset?

Others did point out that there have been trials to allow cycling in the parks which apparently ‘caused pedestrians distress and it’s nice to have a space just for walkers’. One wonders if smelling salts were made available? The University Parks contain a great many paths, maybe just one could be permitted for bikes to cycle over? However, were that to happen we could no longer pretend that the parks were some oasis of Victorian tranquillity. A relic from a time before the bicycles became commonplace. Perhaps the signs should be altered to permit penny-farthings to allow the charade to continue of trying to pretend nothing ever changes?

And so it was, that nothing changed. The University Parks ban on a bike of any kind, even pushed, remained. Residents of north-east Oxford had only two routes for those who cycle into the city centre: either around St. Clement’s and the Plain and over Magdalen bridge, or along the new cycle path, into Marsh town. Anyone, including children cycling to the many schools from their homes in the South West and West of Oxford were similarly limited. And so it might have remained except that bridges age and fail and new (Swan) schools are built. Thus, many more children began to use the Lemond and Fignon bridges. But suddenly, on July 10th 2023, without warning of the timing, or public consultation, signs appeared at the bridges announcing their closure for ten weeks from mid-August.

Sign that appeared without warning on one of the bridges

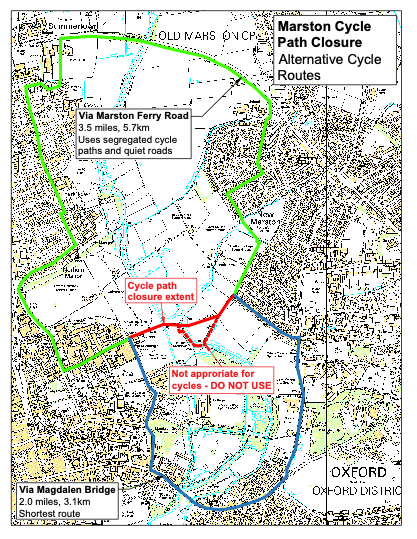

Later, in July, a map was made available telling cyclists that whilst the bridges were closed they must either use the Plain, or take a huge detour around the Marston Ferry road; a route which is now saturated with children cycling to both the Cherwell and Swan schools in morning and evening. The map, unsurprisingly, resulted in anger. The immediate question was: who had drawn it, why had they drawn it and who had approved such ridiculous detours?

A map made available later in July

We now know that on the 22nd of June 2021 a man with a hammer inspected Fignon bridge. He had then reported that: ‘There is wide delamination of the soffit which was hollow sounding when tapped with a hammer. A large area of the soffit concrete cover was missing and additional areas spalled off following light tapping with a hammer.’9 A plan began to be made to repair the bridge which would mean an extensive period of closure, but no local councillors and none of the curators of the parks appeared to have been informed. Some in Oxfordshire County Council must have known, but local residents, university students, older cyclists needing a safe route, parents of school children, cycling organisations, were given no warning almost up to the very point when work was to begin.

When the official notices appeared in summer 2023 people began to take notice and offer suggestions. One city councillor suggested that it might be possible to cycle through the red ‘not appropriate route’ (see map above) and appeared to celebrate that if that occurred, that because a gate was involved, at least life would be made harder for those who ride Deliveroo bikes: ‘so this would rule out the bulkier bikes used by Deliveroo and the like – not a bad thing.’ However, appearing to approve of anything that makes life harder for the servants who bring us our food, is not a good look. What various participants thought of others began to become more and more apparent.

And what of the University’s position? It was almost impossible to find anyone who would claim responsibility, but eventually it was revealed that: ‘The Parks Curators have been kept informed of the discussions but have not formally considered any options involving the Parks, as no alternative routes have been determined viable.’

Determined by who? I and many others asked.

Eventually, on August 1st, an FAQ (Frequently Asked Question) sheet was released by the man who had held that hammer in 2021. The FAQ was only issued to local councillors so that they could parrot some stock answers. It was not made more widely available as there was no public consultation. The FAQ suggested that there was an imminent risk to boaters, apparently. Think of the boaters! Who is thinking of the boaters? But are the boaters, on their punts, more important than local people going about their daily business? Apparently so. And thus it was deemed that something had to happen, urgently, although it was over two years since the after the bridge was tapped with a hammer.

Dead willows and the otters

The FAQ sheet was written in response to a local resident’s suggestion (made and ignored) that a pontoon bridge could have been placed just south of Lemond Bridge to land on Mesopotamia in an area of scrub with no trees affected. Apparently every tree, unlike every child, is sacred. Those installing the pontoon bridge would have to be wary of the dead willow, one which by August 2023 had been unsafe for many months with a heavy branch hanging by a slender sliver of wood. The dead tree was clearly just as dangerous to boaters as the decaying concrete under the Fignon bridge. Neither the University, Environment Agency (the successor to the National Rivers Authority) or the County Council had shown any interest in dealing with the dead willow.

Advice from the City Council’s Wildlife Officer mentioned otter sightings, stating that providing that the lower arm of the river along Mesopotamia was kept clear and free for wildlife, then the threat to otters in and around Parsons Pleasure would be alleviated. No otter nests had been found within 150 meters of the bridge work (which could have been a serious constraint on the way the works were handled). So wildlife threat was not a good reason for not building a temporary pontoon bridge. The temporary route would lead straight onto the bridge into Music Meadow from Mesopotamia.

Ben Dodds

Principal Engineer | Oxfordshire Highways

Milestone Infrastructure

Companies that provide temporary pontoon bridges specifically state that their bridges can be suitable for mass gatherings such as festivals. They can deal with large crowds and heavy loads.

A suspicion grew that the project manager for the bridge renovations working in County Hall but employed by Milestone Infrastructure, through an out-sourcing contract with the local authority, had not thought through any of the problems or alternative options that could arise from closure of the bridges for an extended period. Almost inevitably, a commercial company puts profit above public utility. It seems that this has happened here. The project manager had a desk in County Hall, but when asked by a member of the public whether he was a local government officer he categorically denied this, saying that he worked for the private sector.

Oscar Wilde might have a thing or three to say about Milestone Infrastructure and this behaviour. Thinking this through, and coming up with a sensible and safe way of dealing with disrupted cycle traffic, would have been harder work. It was what this private company’s employee was saying which resulted in the University administrators claiming: ‘no alternative routes have been determined viable.’ The buck, it turned out, stopped with the project manager, who was also the man with the hammer in June 2021. Or did it?

On Friday 18 August 2023 the cyclists of Oxford added their voice to the clamour from local parents, as well as those concerned that elderly cyclists were also being directed to the Plain. The cyclists were concerned by a ‘too long and too dangerous’ diversion as the cycle path was closed. They were upset upon learning that ‘Oxfordshire County Council says it had “no choice” but to close the route for bridge repairs, but some have questioned why a “safe” diversion has not been directed through University Parks, with it instead visiting a notoriously dangerous roundabout…’10

The cyclists reported that the most damming of English words had been invoked and someone was – I almost dare not write the word for fear of shocking you (trigger warning) – ‘disappointed.’ A city councillor invoked this damning condemnation: ‘I’m very disappointed that, after six weeks of discussions with the university, county council and local residents we have been unable to find a safe alternative route across Marston Meadows’.

Things became a little heated. Who was it that had acted on the man with the hammer’s advice? Were they willing to stand by it should a child die on the Plain on their way to school? That was the obvious implication of all the questions being asked. The atmosphere became a little unpleasant, but fear not, loyal reader, for here our story finally begins to take a turn for the better.

Committees don’t sit over the summer, someone, somewhere made a decision all by themselves to do the right thing (or a small group of someones). Or, to be more truthful, to make the smallest of possible concessions when the heat of this somewhat tortured tale, became too hard to bear. Someone realized that it is the University of the city, not that the city exists to serve the University. And that anonymous someone gave permission for Andrew Gant of the County Council and Alexander Betts of the University to issue a joint statement.11 Thus it came to be, that exactly a month after the FAQ had been issued, and within days of the schools opening, on the 1st of September 2023, Oxfordshire County Council issued an official notice, on their website. And a new word entered the lexicon of instructions in this tangled tale, a softer word: ‘urged’ – see if you can spot it in the text of the statement below.

One councillor reported: ‘The University reserved the right to pull this diversion if it’s not working, if we can’t get the marshals (or, unlikely, it’s not used). So people are encouraged to volunteer’. This was accompanied with messages such as ‘will hopefully be a jolly experience for those who take part.’

Why were marshals needed? Why were cyclist being urged not to use the now pink dashed route (formally red) on the map below?

Apparently it was because ‘the river banks are very unstable and risked people falling off them into the river as they are not very wide’. My chair is named after a man who once climbed a mountain. It was time I manned up. I knew my duty and so got out on my bike and cycled the pink route. In the spirit of past great explorers entering lands without the appropriate permission, I set forth on my bike.

Andrew Gant of the County Council and Alexander Betts of the University issue a joint statement.

Geographers, of which I am one, have years of training as regards rivers. I have endured the most terrible of horsefly bites while standing still holding a measuring rod in rivers in more than one country. I am, amongst much else, something of an expert on river banks. And I can report that the river banks are not unstable, that you are a very long way away from the river when cycling on the route, and that you would have to try extremely hard to fall into the river. If you are interested in doing that (falling in) then cycle along the cycle path next to Oxford canal, you will find yourself much nearer to water and in much greater danger of falling in. Here, I am not suggesting preventing cyclists from using the canal path, just take it extremely carefully and slowly. And if you want a narrow cycle path – there are many in Oxfordshire far narrower than this that are shared by both bikes and people. But it is the contractors to the county, employed by Milestone who are the ultimate authority on river banks in the city of Oxford today.

The ultimate ownership of Milestone appears to be vested in French private finance multi-millionaires. This company had been sub-contracted by Oxfordshire County Council to carry out their responsibilities, just as the University has in effect, subcontracted its responsibility to ensure a safe well-maintained set of paths into Oxford to the County Council, while retaining ownership of the land. Everyone thought they could sub-contract their responsibilities away. And so the man with the hammer ended up taking the heat. A colleague wrote to me ‘Maybe I haven’t misunderstood this, but sometimes I am ashamed to be part of this university.’

But this story ends well, the marshals appeared, enter the Oxford yellow vests. Sporting their best gilets jaunes (blanche and orange for two stylist dissenters). Five marshals appeared on the first day, and maybe another five on the second. The last time I pushed my cycle along the new Oxford blue route (map above) I only counted two marshals – but let’s not tell the University that. It can be our little secret. On 19th September, following a meeting of the Parks authorities, marshals and councillors, a decision was made to extend the time for using the alternative cycle route through the Parks by half an hour. More importantly, the Park authorities are engaging with others.

Oxford’s yellow vests – those who first marshalled the safer alternative route.

I guess the marshals were required to maintain the Victorian ambiance of the parks – a Victorian park comes with Victorian style marshalling and Victorian attitudes. Someone somewhere really wanted to get the children to get off their bikes and pushing them – even if the alternative is to cycle round the Plain; which becomes a faster route once you require the children to push their bikes through the Parks.

I decided that I would rather not know who that person was, so did not ask.

Previously I had sent hundreds of emails over the summer to try to determine who was responsible, and then plead with them to take action. I was far from alone, I had a vested interest. My nephew cycles that route to school. My youngest son cycles it to serve wine and carry plates of food in the evenings at a college, his only alternative would be the Plain.

In some of the replies I received I detected something I had felt before, as an Oxford child, and later on first arriving back in Oxford over a decade ago but never had the language to describe. I have that language now: The Oxford sneer – the curled upper lip – the sneer has a particular quality to it in this place. It may be subconscious, but it occurs in written communication as much as being a facial feature you might find hard to control. It is less useful, less attractive, and far less well known than the Oxford comma. But it definitely exists. Those who claimed an alternative route for cyclist was needed won out, despite others sneering that none of this was needed. I asked questions (by email) that revealed just how little they knew of the city they lived in. I kept the emails. I always do.

On the 14th of September 2023, former city councillor Roy Darke, one of the most effective campaigners to ensure that the University was not too stupid, had a letter published in the Oxford Times. Its text reminded me of Utopian stories of successful urban design in which the old will look out on children playing, with parades of perambulators being pushed by, young men and women passing merrily, alongside the cycling old maids on their way to evening mass in the autumn mist, and those in wheelchairs also well accommodated. But it also offered up a new vision, or rather a modern vision, of what we once had long before any of us were alive, and how we might win that back again – more active travel routes across the rivers and into city:

‘It is with pleasure that I sit eating breakfast on Edgeway Road and see youngsters (and others) cycling safely in and out of town on the safe ‘alternative route’ whilst the bridges are renovated. But let’s not be too complacent or sycophantic about this temporary reprieve from the fatal and only alternative route offered for cyclists by the County Council. Requiring 11-year-olds to cycle to school via The Plain was downright irresponsible and showed open neglect of public duty and a lack of spirit and imagination.

The University and local authorities should more openly take joint responsibility for making Oxford a safer and more equal place. A safe city means looking to create more vehicle free routes for cyclists and pedestrians. A series of Calatrava-style cycle bridges across Magdalen (Addison’s Walk), Christchurch Meadow (linking to Meadow Lane), through LMH etc. would add enormously to cycle safety and excite the aesthetic scene in this inspirational city.’

There are many different Calatrava style cycle bridges to be seen all around the world. Most are short and subtle, but some are large enough to span the Thames and allow shipping to pass. One is shown here.12 We are a long way behind the Dutch (in so many ways, including, when it comes to travel), but there are many ways in which new bridges can be built. As well as new platforms across meadows, over steps, and through Fellows’ Gardens.

A Calatrava style bridge – in the Netherlands.

Like Newcastle and Gateshead have now across the Tyne, and Oxford once had, there should be again seven bridges, cycle and foot, across the river Cherwell. We should have so many ways to cycle that when one route needs to be repaired it causes no problems. Far better to donate money for a bridge to save lives, than for yet another university building that doesn’t. The many colleges that border the river could all have a bridge for cycles and walkers, or make the existing ones open. Since I have returned to Oxford in 2013 the only new bridges that have been built were two, both built to ensure that students (unlike Oscar Wilde) would not have to mix with the public.

If you don’t know by now, why all this has to change, and why this is not the end but only the beginning of a story, then think of what happens when everything changes, forever, with no trigger warning. Don’t think of the child necessarily, or of the old lady who gained the first degree cycling across St Giles, on her way to an evening lecture. Don’t think of the mother of two, or the husband, wife, boyfriend or girlfriend. And don’t necessarily think of those school children. Instead think of their parents, their friends, their siblings (like me), and their children, their partners, those who live with what happened for the rest of their lives; and – if you can, think also of the drivers. When a car, or bus, van, or lorry hits a cyclist hard – without any trigger warning – everything changes, forever.

On the 28th of April this year the BBC ran a story featuring Ling Felce who was killed when she was hit by a lorry on 1st march 2022 on the Plain.13 The story was about how just one extra incremental change was being made to the design of Oxford’s still most dangerous roundabout. Lorries were to be banned from loading and unloading goods between 7am and 10am and 4.30pm and 7pm on or by the Plain. But what happens outside of those hours? What will happen when the next University scientist dies on the roundabout?

Ling Felce

Ling Felce’s husband has spoken out, including to the BBC, about thinking of the family of the vehicle drivers –which is very admirable and something rarely seen in public.14

The County Council, as the democratic planning authority, needs to establish a review group to reassess cycling in the city. Its aim should be to ensure no road deaths of cyclists, of pedestrians, of drivers or passengers (vision zero) and that far fewer are injured every year. The colleges, the University, the city and county local authorities need to work together to establish safe connections between all the University’s sites, the city’s schools and homes. The University itself should employ a cycling expert to coordinate action for safer cycling throughout the collegiate university, and to work closely with the local authorities so that the university, and especially the colleges, are helpful – rather than being a hindrance.

Finally, the Cycle Track and Mesopotamia are always closed on 25 December and 1 January. Do we really want to increase the chances of a death on the Plain on Christmas Day because we are so scared of re-establishing what was once a nearby right of way?

1 http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/stree...

2 http://openplaques.org/plaques/3780

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ru...

4 https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/side-...

5 http://www.oxonblueplaques.org.uk/pla...

6 http://www.threshold-press.co.uk/memo...

7 https://www.cyclox.org/index.php/2023...

8 https://www.headington.org.uk/maps_tr...

9 https://docs.planning.org.uk/20230220...

10 https://road.cc/content/news/cyclists...

11 https://web.archive.org/web/202309030...

12 https://inhabitat.com/arching-melkweg...

13 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england...

14 https://www.roadpeace.org/prevention/

Danny Dorling is a patron of RoadPeace, the national charity for road crash victims in the UK, and the brother of Benjamin Dorling (1971-1989), who was killed by a car when cycling on his bike, coming home, in Oxford.

For where this article was original published and a PDF of it click here.

October 9, 2023

Ed Balls and George Osborne’s new podcast is essential listening – but not for the reasons they think

In an apparent attempt to “talk across the political divide”, former chancellor George Osborne and former shadow chancellor Ed Balls have launched a podcast.

Political Currency has been billed as a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the rooms and minds where the key decisions are made. But what is perhaps more evident from the opening episodes is not how politicians of different parties can communicate so much as how they can collude.

It hasn’t taken long for the two men to use the podcast to celebrate their joint achievements. This began with the current Labour party “sticking with the two-child limit on welfare, which I [Osborne] introduced.”

Balls’s response was telling:

Well, that takes you to an interesting thing in British politics which is that in the end, however contested things are, the only things that last are the things that become consensual. So, the Conservatives opposed the minimum wage in 1997, you [Osborne] ended up boasting about raising it. The Conservatives opposed Central Bank independence in 97/98, you ended up being a champion of it. The trade union reforms of the 1980s, which many Labour People hated at the time – clearly Tony Blair and Gordon Brown carried on with them. So, things which are contested can become consensual and when people agree, that is often how our county moves forward.

Issues on which Balls and Osborne appear to happily agree have so far included setting a very low minimum wage for huge numbers of workers and greatly curtailing the ability of trade unions to protest and organise.

Those of us who listened on learnt how cross-party consensus was achieved in Westminster on the policy to restrict benefits so that parents can only claim support for two children – not a third or any subsequent child.

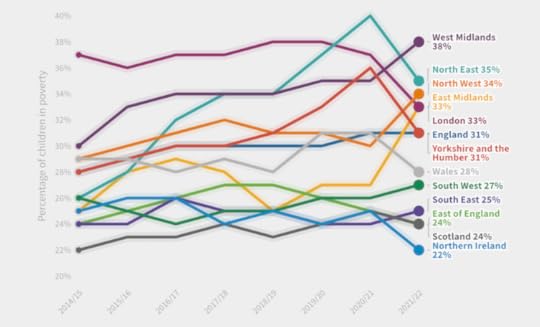

This policy has been a key driver of child poverty in England and Wales, where a majority of children who have two or more siblings go hungry several times a month. The policy does not apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland, which are now the two places in the UK where child poverty rates are lowest.

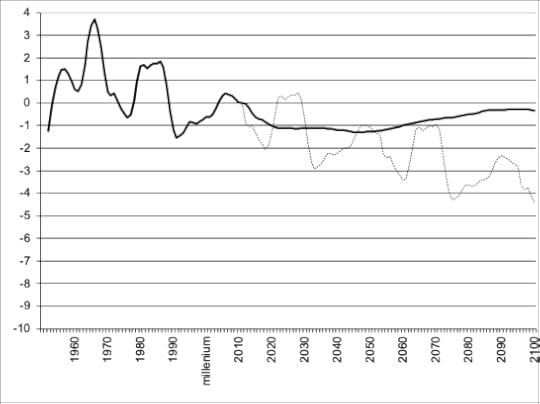

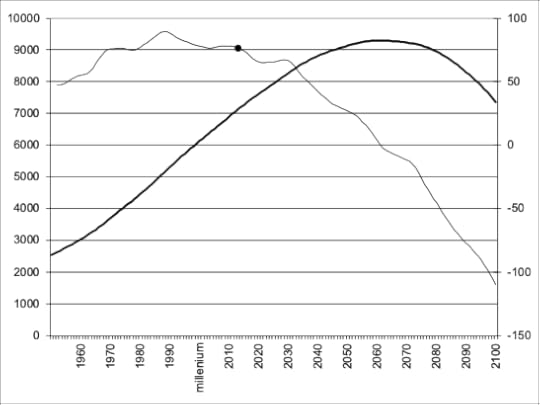

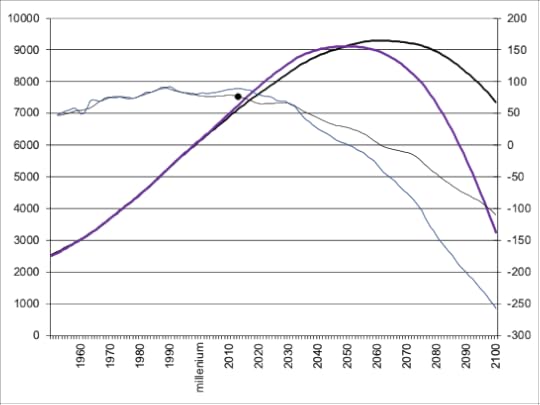

Child poverty, 2014-2022.

Child poverty, 2014-2022.End Child Poverty Coalition, CC BY

And yet poverty itself has so far only been mentioned once on the podcast, around halfway through episode one. Even then, our hosts were talking about pensioner poverty – an issue that matters, they explained, because so many votes are involved.

In the same episode, Osborne revealed how the New Labour and Conservative parties had colluded (or “worked together”, as he put it) to “see the state pension age go from 65, to 66, to 67, to 68”. He continued with another example of how key issues were agreed by both sides rather than being put to the electorate:

I remember Peter Mandelson coming to me before the 2010 general election, he was the [Labour] deputy prime minister, and saying “we want to put up student fees, tuition fees, but we can’t do that before an election, its too difficult for Labour, why don’t we set up a report, and while you as Conservatives hopefully want to see the tuition fees go up so that the universities are better funded, why don’t you sign up to this commission and it can report after the election?”

Balls agreed that this was the right way to go about things, that the two main political parties of the UK should agree policy between themselves, as the “grown-ups in the room” while ensuring that it appeared as if each election mattered.

The two men appear to agree on almost everything of any substance. Or if they don’t, they’ll work out their differences between themselves and tell us the result later.

Listen to the ‘grown-ups’

So far, Balls and Osborne have been in a celebratory mood in their discussions. They appear very happy with the current state of British politics and the people in charge. There is much bile disguised as banter.

Both have particular contempt for Boris Johnson, Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn, with most of their anger directed at Miliband, who they linked, at length and unfairly, to Russell Brand. They both disagree with Brexit but accept it. For them, in 2023, the grown-ups are back in charge again – and that includes their gaining air time.

Listening to them, I’ve thought of how the austerity policies they speak about have led to deprivation in the UK on such a scale that many children no longer grow up properly, physically or mentally. How the average height of five-year-old boys in the UK has risen and fallen since 1990.

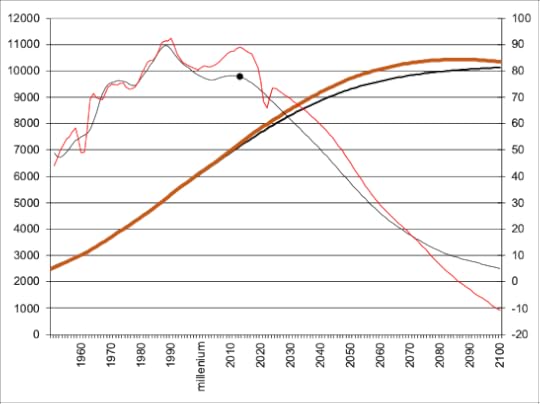

Average height of five-year-old boys, 1990-2020:

Average height of five-year-old boys.

Average height of five-year-old boys.The Lancet/ITV, CC BY

If Balls or Osborne have an explanation other than child deprivation for the above trends, it would be interesting to hear it. The most convincing explanation I have heard as to why we have tolerated such high inequality and poverty in the UK for so long was reportedly given at a private dinner in Hampshire in 2002, when Margaret Thatcher was asked what her greatest achievement had been. She replied: “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.”

There is an older parallel to be drawn, too. In 1940, three journalists of three different political persuasions wrote a book together: The Guilty Men. They were Michael Foot, Peter Howard and Frank Owen and their targets were the British public figures who appeased 1930s Germany.

A similar book could be written today about the appeasers of market forces who promised that we could live with “tough decisions” under austerity and that children would not go hungry or grow up stunted.

But instead we have the two-men-talking-to-each-other podcast format. In every episode, Balls and Osborne happily outline the thinking behind their actions – the actions that just a few in my generation, given the best starts in life, have taken and have caused such harm to others.

I am grateful to them for using their show to put so much on the record about their time in charge, years before their cabinet papers and other secret documents will be released to the public.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For another link to the the original article and a pdf of it click here

October 2, 2023

How Britain became a shattered nation

In this excerpt from his new book, academic Danny Dorling exposes a new geography of inequality and social fissures across the country.

Where did you grow up?

For the first few years of my life, I lived in a house on a road between a cemetery and a shopping centre. I don’t remember much of those years, and I suspect that I was too young to really know where I was living within the city. I now know that there was near full employment around me, and that my rose-tinted recollections of smiling faces fitted the mood of the times. People had never had it so good. Britain had never been so equal. Life chances had never been as fair as they were then, and they were better for more people than they had ever been before, even for those who fared worst.

When I was aged six, in 1974, my family moved to a house close to a major roundabout on the east of the city. In the 1970s, which neighbourhood a child lived in mattered far less for their life chances, and which local school you went to was less important than it is today. House prices varied far less between areas, and children who grew up in private housing and council housing more often played together, largely unaware of whose parents paid rent or had a mortgage.

There were two general elections in 1974. These were becoming turbulent times, but the turbulence had not yet affected my neighbourhood. I later learnt that in the shipyards of Belfast, on the Clyde and on the Tyne, people were losing their jobs. But the car factories in the city of Oxford were still employing thousands. I had no way of knowing that the children in my school year would be the final cohort taken on in such large numbers to work in those factories. The wave of manufacturing unemployment that swept down from the North did not reach Oxford until my later teenage years.

Shattered Nation illustration by Emma Balebela

The ravages of the 1980s swept away most well-paying jobs in the city’s car factories. Deindustrialisation was masked by gentrification as the two local universities expanded. The cheaper neighbourhood on one side of our roundabout had begun to be gentrified. The more affluent neighbourhood on another side had become unaffordable for most people who worked locally. When the manual work began to dry up, the first to lose their jobs were the parents living on the council estate beside a third segment of the roundabout. Many school-leavers could not find work. The reputation of the council estate began to fall, while estate agents talked in ever more glowing terms about the wonderful houses in the more affluent neighbourhood.

The lives of the teenagers I went to school with became increasingly determined by what side of that roundabout they had grown up on. Place mattered much more in the 1980s than it had done in either the 1960s or 1970s. The borders of the local primary school catchment areas became more rigidly defined and apparently important. Children played a little less freely across those borders. A tiny few of us went away to university. Almost without exception, those who did so lived in the ‘better’ segments. I was one of those few.

I came back in my forties to live again in the same city. Recently a local councillor told me that there were over 200 places available on Airbnb in the council estate next to the roundabout. I checked on the website, and at first it appeared he had exaggerated. However, whenever I zoomed in to any part of the estate, a few more Airbnb offers would appear; and not just in the estate, but all around the roundabout. It can be a shock to see that so many of the homes your friends grew up in have been sold on, and bought not by a family to live in, but just to be rented out to tourists.

The Oxford neighbourhood that once had the cheapest private housing – where the majority of homes were originally owned by car-factory workers – is now too expensive for most university academics to afford. Today, it’s increasingly inhabited by London commuters, including political reporters and business folk, many benefiting from being able to work from home while in theory working in London. The most expensive enclave in the neighbour- hood has become an investment opportunity for overseas buyers and more up-market buy-to-let landlords. What was once the local pub is today a drive-through McDonald’s. Fields that I played in as a child are now fenced off. There are also fewer children playing outside; and fewer children overall. Today, children mix far less with other children.

If you grew up in Britain, think of what has now become of your home neighbourhood. Very few areas of the country have become less divided over time. Those that have tend to be places that have been abandoned by money and are becoming more similar because poverty is rising more uniformly. They are now areas of increasingly widespread and severe deprivation. Conversely, many cities now thought of as affluent have some of the greatest local social inequalities within their boundaries.

I left Oxford at the age of eighteen, and lived for ten years each in Newcastle and Sheffield. The place I grew up in is hardly recognisable to me now. Most buildings are the same, but the city has become a completely different social world.

A similar story can be told of almost anywhere in Britain, but the story of what has happened to Oxford illustrates how nowhere has escaped the crisis of a shattered nation. The city of Oxford is a far more unaffordable, tense, anxious and restless place than it was in my childhood. There are far more students now, many of them coming from overseas and featuring as part of the ‘export earnings’ of the nation. Those who are not from the United States are normally shocked to see how many homeless people sleep on Oxford’s streets. People hardly ever had to sleep on the streets of the city during my childhood.

In 2019 Oxford made national news when it was revealed that the city had one of the UK’s highest rates of homelessness as well as of deaths among homeless people. What most shocked local officials was just how many of those who had died had grown up in the city, had gone away, and then come back. What most shocked me was that many were around my age, and I even recognised some of the names of those who had died. In one case, I was able to provide a name when shown a photo of a deceased person the authorities were trying to identify. He had attended my school.

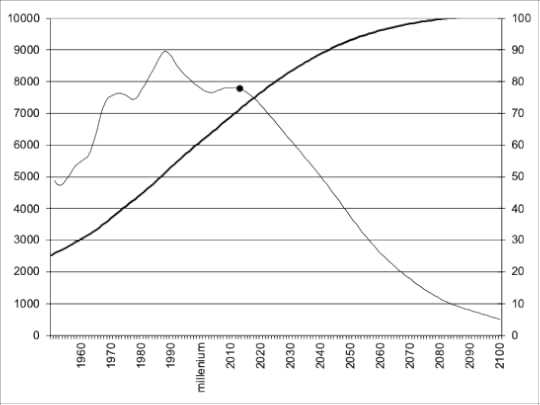

If you live in the UK, it is easy to believe that everything must be getting worse everywhere. But in most of the world, most things to do with human lives and livelihoods are getting better. People are living longer. Life expectancy is rising steadily almost everywhere, except in the UK (and the US). Almost everywhere, infant mortality is falling faster than in the UK. Almost (but not quite) everywhere, people are better off than their parents were. Economic inequality is falling in the majority of countries, and population growth is slowing even in the poorest nations. The social statistics suggest that elsewhere in Europe people have never had it so good, although in the most equitable and advanced European countries folk tend to be sceptical about social progress and are far more vigilant in tracking signs of a lack of progress than we are in the UK. Other parts of the continent have experienced the socio-economic decline of which the UK is an extreme example, but they are the parts that have more often followed the UK policy mantras of privatisation and individualisation. These mantras are now being questioned more intensely than before.

Shattered Nation illustration by Emma Balebela

We now expect the global human population to peak in number within the current century. Educational opportunities are widening, and that is linked to the global population slowdown, as well as rising rates of equality in so many countries. There is terrible poverty in much of the world, but it is now more often falling than rising. Other economic inequalities are also falling worldwide, although falls in income inequality, and states becoming more stable and safer, never seem to make the news headlines. I can show students hundreds of statistics from all over the world that suggest we are not travelling towards hell in a handcart. But I can find hardly any social statistics about the UK that are particularly positive, and I spend much more time looking for them than most people do.

Climate change, our great global concern, is now being taken far more seriously than it was a decade or two ago. Carbon emissions per person are lower in more equitable countries as compared to the more profligate unequal ones, and especially the most unequal richest countries. We can see what we have to do to reduce pollution. Much may have been left too late to avoid serious harm, but some good things will be achieved. Even the numbers of people directly involved in wars have been falling for decades, although we are rightly shocked by each new war. The threat of nuclear war, something we once thought would be almost impossible to avoid, has fallen over recent decades, although it rose again as a concern after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

I am not pessimistic when it comes to global trends. It is just that closer to home the statistics are all a great deal less rosy. As a nation, we have travelled down a road that people in other nations have almost always been far more successful in avoiding. That has brought us to a particular point and resulted in a particular human landscape in the UK, one that is hard to summarise but perhaps can be best described as shattered: people feeling shattered. Hopes shattered. Much of the fabric of society shattered. The ability of our schools to educate our children well, of our social housing system to cope with need, of the National Health Service to care for us, and so much else – all shattered. Many of those previously just coping can no longer cope. Food banks are proliferating. Levels of debt have increased for millions of people, while a very few of the extremely wealthy have seen their riches soar. So many people are feeling shattered by all of this.

As a nation shatters there is a tendency to see each new crack as being the most important issue of the day. Often the retaliatory response is to say that each such event is just part of a global process that happens to be a little worse for the UK than elsewhere. But there comes a time when bad luck strikes too often, in the same place and repeatedly, for all of it simply to be blamed on bad luck. Geographical comparisons show that most places have not been as badly affected by so-called global processes as Britain has. In fact, many of those slow-running processes have had benign or even beneficial effects elsewhere.

Britain reached its current peak of overall income inequality a very long time ago, in the mid-1990s, and has remained extremely unequal every year afterwards. Ever since then changes have taken place that were not seen elsewhere in Europe. By the time the Labour Party led by Tony Blair came to power in 1997, no other European social-democratic party had placed itself and its policies so far to the right. People joked that Blair was doing things that the right-wing Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher would never have dared to attempt.

At a private dinner in Hampshire in 2002, Thatcher was asked what her greatest achievement had been. She replied: ‘Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.’ This may be a little unfair on Blair, and is certainly unfair to many of the MPs in his governments. But, partly in order to outmanoeuvre New Labour, the Conservative Party was subsequently pushed even further to the right. Indeed, in the European Parliament in 2014, British Conservative Party MEPs left the large centre-right European People’s Party group to instead ally themselves with a small far-right group that included the German political party Alternative für Deutschland.

What had pushed the Conservatives so far to the right? It was the rightwards shift in Labour during the thirteen years the Conservatives were out of office. New Labour introduced university tuition fees of £1,000 a year in 1998, raised them to £3,000 a year in 2004, and then set the stage for them to be increased again to the highest levels seen worldwide by 2012 (the average US state university fees are second highest). Most importantly, the Labour governments of 1997–2010 did not bring inequality levels down.

Britain went on to suffer more severely from the global economic crash of 2008 than almost any other nation. This was because the Blair government, seeing financial services as paramount and seeking to avoid upfront payments by government, had made financial sleight of hand central to its plans, such as by massively extending what was then called the Private Finance Initiative. New Labour had become reliant on the continued growth of the City of London. Austerity, imposed from 2010 by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government, was deeper and longer in Britain than anywhere else in Europe. This was partly the result of decisions made by Labour between 1997 and 2010, and not simply because the coalition government, and the Conservative government that succeeded it in 2015, was so callous, although that callousness significantly exacerbated the suffering.

Britain was shattered as a result of the actions of all three main political parties.

And while the leaders of all three opposed Brexit in 2016, it still happened, eventually, in January 2020.

Shattered Nation illustration by Emma Balebela

The key ramifications of the shattering of the UK are threefold. First, we are growing spatially and socially further apart from each other. Second, the five giants of poverty first identified in the 1940s – want, squalor, idleness, ignorance and disease – are returning in new forms. Third, we have growing internal political divisions. These spreading cracks in the social structure are all classic signs of a failing state.

When a state begins to fail, attempts are made to suggest that claims of its shattering are exaggerations. Typically, a list of apparent problems faced by other countries will be produced whenever their people are said to be doing better than the British: ‘What about suicide rates in Finland?’, ‘What about Germany’s reliance on Russian gas?’, ‘What about the rise in “populism” in the US, Brazil, Hungary, Turkey and Russia?’ This response is so common that it now has its own label: ‘whataboutery’, which itself dates back to responses to the Troubles in the shattered province of Northern Ireland in the 1970s

One of the functions of whataboutery is to paper over the cracks by diversion and subterfuge. It draws people’s attention away from what they should be looking at by attempting to make false comparisons or confusing the terms of reference. In June 2021 it was revealed that ‘British diplomats [are] being told to change the way they speak about the UK, referring to it as “one country rather than the four nations of the UK”’.

In fact, hardly anyone tries to present the UK as a single nation, but the decision by the government to refer to it as such is another illustration of an attempt to paper over the expanding cracks. The United Kingdom is nothing of the sort. It is actually becoming increasingly disunited.

When London-based Conservatives mention ‘this nation’, for them there is only one. At the very least, it encompasses all of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a sacred indivisible whole. For some of them, Gibraltar (whose residents were allowed to vote in the Brexit referendum), the Falklands and a myriad of other rocks and islands dotted around the world are also part of their imagined British nation. One idea of a nation is of a place or a people worth fighting for. The few shattered remains of a once vast empire are clutched close to the hearts of a particular group of people who would happily send others to fight to defend every remaining offshore holding.

In a shattered state the invisible walls separating areas grow ever higher. But those walls remain mostly invisible because we are repeatedly told that they don’t really exist, and that there is opportunity for everyone out there. Lip service is paid to levelling up, even as most people are being beaten down. A peculiar map emerges as a result, a geography of places with decaying fortunes encroaching on the enclaves of success.

Those enclaves are found in the more affluent streets of London, but also in the country retreats concentrated mostly within rural parts of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and in pockets close to the roundabout I grew up beside. The few people who have done well for themselves increasingly occupy the enclaves. In my childhood the better-off were more evenly spread out geographically. However, no enclave of affluence is now very far from other places that are going bankrupt.

In May 2022, a stone’s throw from Eton College, the borough of Slough was ordered to sell off all its assets in the wake of being forced to declare bankruptcy over outstanding debts of

£760 million. These assets included the town’s public libraries, all of its children’s centres, its community hubs and what remained of its council housing stock.

The story received very little media coverage. This had already happened in so many other places. By September 2023 the list of places going bust had even extended to the UK’s largest local authority, Birmingham. It was also becoming clear that the same fate was about to befall more and more local authorities facing escalating fuel bills and eviscerated by decades of central-government policy designed to privatise public goods and services. Most secondary schools had been transferred out of local authority ownership long ago, and most primaries more recently. At least they could not be sold off, but they would now have to face the coming storm on their own.

The pillaging of the state has seen the numbers of UK public sector workers – in other words, people working for the public good – plummet from 23 per cent of all those in work in 1992 to just 17 per cent of the much larger total national workforce today. The proportion is redefined over time by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to allow for changes in definitions of who is a public servant. The most recent large fall in the share of public sector employment began under the New Labour government in 2005 and has continued ever since, despite a temporary halt when the Covid-19 pandemic arrived in 2020. Overall, UK public spending as a proportion of GDP fell below that of Spain in the 1980s, and below that of Greece in the 1990s. It was already lower than almost every other Western European nation following the cuts that began in the late 1970s.

It is worth reflecting on the fact that it was only the least democratic of Western European nations that spent less on public goods after 1980: Spain was still recovering from the dictatorship of Franco, and Greece from the junta of the generals. While the UK continues to be an outlier in the paucity of its spending on public goods, both Spain and Greece are now much more democratic and more like the rest of the European mainland in having large public sectors than the UK.

A country’s spending statistics are presented by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a proportion of GDP. The IMF also reports on what countries plan to spend in the future. The current UK government has said it intends to spend less than almost everywhere else in Europe, even though it will allocate a higher share of its public monies to its military than any other Western European country, and a huge amount to its debt repayments. Here are the percentages for 2023: France and Belgium will spend 55 per cent of their GDP on public services, followed in descending order by Finland, Greece, Austria, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany and Spain, and finally both Portugal and the Netherlands at 45 per cent, with the UK way below at only 41 per cent. While the IMF’s projection for the UK for 2023 is two percentage points higher than the 39 per cent spent in 2019, that is a reflection of the rising costs of debt repayment and the projected further increase in military spending, rather than representing any rise in spending on public well-being.

The position of the UK is even worse than the numbers above suggest because in recent years its GDP has not risen as much as that of other European countries. Meanwhile the pound has fallen in value. By the first quarter of 2022 the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) was reporting that average real earnings per person in the UK were a massive £11,000 lower than they would have been had the slow upward trend seen through 1990–2008 continued.

You can still find parts of the UK to visit that have picture- postcard looks and which on the surface appear impervious to change. But even there, when you scratch beneath the surface, all is not well. Behind the Regency facades of Chelsea and inside the barn conversions of the Cotswolds there is growing anxiety. Very affluent people now ask me, much more frequently than they used to, what I think will happen when most people realise what has happened to the UK. I do not have a simple answer for them. The decay is clearest in the suburbs, where families now increasingly rent a home that a generation ago they would have owned.

In Middle England neighbourhoods like the one I grew up in, I get asked to give public talks about how people might cope with the latest cost-of-living crisis. In poorer areas, where things have been so bad for so long, there is less of a sense of crisis and more one of bitter resignation. The crisis of 2022/23, as mortgage rates rose, was very much a middle-class affair, affecting almost everyone who had got on the housing ladder in the current century. It was no longer among the poorest where the pain was most concentrated. The children of the winners from Thatcher’s Britain are now losing out. They face unprecedented spikes in their energy bills, pay rises below inflation and, if lucky enough to have them at all, the prospect of their private pensions becoming increasingly insecure. That was partly why Liz Truss tried to offer them Thatcher Mark II, and why Rishi Sunak presents a re-spinning of Tony Blair–like enthusiasm. But the deeper the malaise becomes, the more any solutions will need to go in the opposite direction to Thatcherism, and the more the question arises: when will so few benefit from the system, a system that already fails so many, that it ceases to be tolerated?

The multiple crises that afflict Britain are worse and have deeper roots than those affecting other European states. The UK is now very likely to be the most economically unequal country in Europe (although until early 2022 it was ranked just slightly more equal than Bulgaria). The repercussions are widespread. It really matters that Britain has the most divisive education system in Europe, tainting our institutions and affecting individuals for life. It matters greatly that the UK has the most expensive and poorest-quality housing, the most precarious and often lowest-paying work for so many people, the lowest state pension and the stingiest welfare benefits. Recently Britain has also experienced the sharpest declines in health in all of Europe, especially in the health of its children. A whole state is being plunged ever deeper into poverty. This is failure. It is not surprising that even the rich are now worried.

As the crisis deepens, geographical inequalities grow and, cruelly, these disparities help to sustain the crisis because they serve to hide the exploitation it involves. The very rich increasingly live apart from the rest of us, leading parallel lives. But so too do the fairly rich, who control most of what is left of the opposition (both within Parliament and the mainstream media), and who tell us that the only rational alternative to our shattered present is a watered-down version of more of the same.

This book is not utopian. Its core argument is that sooner or later Britain’s divisions will have to be addressed because they are now so great that they are becoming unsustainable: too few people now benefit. However, addressing these divisions will not result in a sudden arrival at the sunlit uplands.

Nonetheless, we have been this shattered before, and other states have been too. In every case it took decades to put the pieces back together again. We can choose now either to cultivate hope, so that we have the energy to persevere, or to burn out in exhaustion at the collective trauma that the shattering induces, and allow those who have divided us to continue to do so. This is the choice we face.

For where this article was originally posted and a PDF of it click here.

September 24, 2023

When we were young: Inequality revisited, a commentary on Geoffrey DeVerteuil’s essay

Not very long ago, the world had a different shape. The cities were shaped differently too. Anglophone geographies brought into life theories about what all this meant. Global Urban Studies was a little prince world. A world in which each prince, each scholar, created their own theory. Theories were plentiful. In Le Petit Prince the Geographer is ‘…too important to go wandering about. He never leaves his Study.’(1) He believes that geography books are ‘…the finest books of all. They never go out of fashion.’ The geographical scholar (who Antione de Saint-Exupéry had brought to life) distained the ephemeral, that ‘which is threatened by imminent disappearance.’ That particular little prince world is no more. The 1990s theories turned out to be ephemeral. Geoffrey DeVerteuil’s essay breathes a little life back into some of them, arguing for not forgetting – not becoming too distracted by the new, especially not by the more obviously ephemeral ideas that often dominate today.

In times within living memory, we talked more about class. It was class, we said, that shaped our cities. City structures reflected our class hierarchy. Flat corrugated iron roofs were the symbols of poverty. Roofs that barely kept out the rain and held in no warmth. Grand homes with high-pitched gables displayed affluence, projected authority, and gave material comfort.

Billions grew up under the deafening sound of the rain on iron. Others, little princes, were driven in cars past those ramshackle homes in their childhoods. They glimpsed lives they could only barely envisage living themselves. They learnt not to imagine. It was the city of walls, of quartz, of iron roofs and townhouses.

The squeezed middle was shrinking. Increasingly, you were either privileged or poor; prince or pauper. The city used to be more corrugated. The elite ridges separating everyday valleys were of lower social elevation in that past. The working-class grooves between them, were higher. The undulations, are more closely packed.

Back then, rich lived nearer poor. But the middle was slowly squeezed out as inequalities rose. Back then, rich were less rich and poor less poor than now. Society, though, was being stretched thin. It was, increasingly, those with more princely childhoods who were writing the new theories. There was so much more to the story of inequality, they suggested. principally, that they had so often, more often, been brought up set apart by money was not of most importance anymore. The princes were aware, they implied, of their positionalities; of their privilege.

DeVerteuil’s analogies of corrugated and lopsided are apt. Today the city is more lopsided. Gentrification has now filled up the gaps between a few of the highest hills of wealth. Proletarianization has levelled down other parts of the city. Now the city looks more like a giant volcano than a series of flattened low-lying valleys. A lopsided volcano with steep cliffs.

The once corrugated city is no more.

Today the very richest little princes own the townhouses, maybe more than one, but those dwellings are now worth so much more than before. In increasingly unaffordable enclaves, in almost every city, the grown-up children of the rest of the rich colonise the tiny homes of those that were once poor. Refurbished at great expense, these residences are named after French jewellery (‘bijoux’).

Said to be worth a fortune, bijoux homes are increasingly purchased for show and because of the princes’ growing fears of living elsewhere. Supposedly a safe investment, they are places where most of their value is derived from being high up on the cliffs of the volcano, up far above the poor. Their purpose is not to display affluence, project authority, or give great material comfort; but to be safe spaces. The princes think they live in modest homes.

As the city became more lopsided, concerns on the cliff sides transformed with the rising up of the social cliffs. To princes, those with the least began to look more like ants, no longer so human, as others are now so far below. Children who had learnt not to imagine being poor, began to see themselves more often as suffering too, in an increasing variety of ways.

You may inhabit a jewel of a home, a bijoux home, but now you too can be just as much a victim of inequality in the new lopsided city.

Today, little prince, your gender, race, sexuality – or one of many possible disabilities and neurodivergences – increasingly matter to your life on the cliff side. Your grievances, you are told and begin to tell others, are of equal importance and deserve as equal respect as any other feelings. Whether as a child you slept on silken pillows or under a corrugated iron roof is just one aspect of your fascinating individual identity.

In London, in 2023 candles began appearing again in the rooms of homes at the bottom of the cliffs. Homes in which the paupers can no longer afford to feed the electricity meter. In Baltimore, and across the United States, is it no longer unusual to have known eviction as a child. In my home city of Oxford, the poorest babies are again being brought up never having been washed in warm water. The fuel prices rose too high in 2023 and in the year before.

As yet, it is only a few who suffer the worst extremes of this new pauperisation in the richest of countries. But it was not like this in the 1990s; and it is all now taking place under the shadow of the princes’ homes, under the shadow of streets ‘worth’ billions. There are far worse stories to be told from the periphery of the United Kingdom, and much worse from the most shattered badlands of the United States.

It is the lopsided nature of the suffering that most grates. The rich, in a time of fuel inflation, do not know how high their heating bill is; they simply pay it. A few also pay the heating bills for their stables and swimming pool, their second, third and fourth homes, and perhaps for their garage too, to keep the car warm.

In Buckingham Palace, a prince who recently became king, turns down his thermostats. But he does it because he cares so much about the planet and he worries, like Antione de Saint-Exupéry’s creation did, about the future of a flower he holds in a pot in his hands. The planet matters more today, and the poor matter less. He wanted to be a defender of all faiths, not just one. Intersectionality matters to him too. He would never ask a guest where they were really from.

This kind of inequality – new extremes of poverty and riches coupled with greater sensitivity for other differences – is today just one inequality among many in our newly more lopsided world. All inequalities have become of near equal importance: racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, and the recognition and respect for a myriad of forms of your and others’ neurological different strengths and challenges. But if, little prince, you can claim to suffer from more than one of these prejudicial victimisations, that intersectionality is of greater importance.

Suggest that racism tends to disappear when and where inequalities in income and wealth narrow, and you, little prince, might be greeted with derision and the accusation of not taking deep-seated prejudice seriously enough. Suggest that at the heart of misogyny is an inequality in power, and that above all else it is money that confers power, money that lets some people buy other’s time and lives, and that might imply that you just do not understand and empathise enough with the other, or understand affect and that you concentrate too much on the material. Point out that violence against trans people is disproportionately suffered by those in poverty, particularly those in forced sex work, and you may be suspected of belittling the harm caused by micro-aggressions.

More people in your city may now be hungry each day, but hunger has become just one of many possible sections of a greater intersectionality. As today’s scholarly geographer might observe to a visiting little prince, such distinctions are most commonly (and increasingly) made in the two countries that are home to those who contribute most to geography and urban studies journals. It is where hunger has grown the most in the rich world, where income inequalities have grown highest, that class has been most demoted to now become just one inequality among others.

As the paper that this commentary addresses makes clear, concern for intersectional thinking has become most common in the ‘more neoliberalized contexts such as the United Kingdom and the United States’ (DeVerteuil, 2023). And hunger and poverty of others are now seen as being of greatest concern in places where hunger has become most rare, in the least neoliberalized contexts, in the most equal of affluent nations.

In the 2020s hunger is most rare in the Nordic states and in Japan, France and Germany, in those countries where culture wars are less dominant; where the cities are far less lopsided; and where the poor have more power, still the least power, but they are not as comprehensively so often ignored as they are by today’s Anglophone geographers and avant-garde global urban studies scholars.

Acute poverty is accepted as a part of the new social landscape in the risk-taking U.S./U.K. context. A new arena where what increasingly matters is the multidimensional imagined playing field of opportunities to be made more equal. The fields in which the little princes play.

Among today’s young princelings, those most awake point out that if 16-year-olds can join the army then – if a child is old enough to consent to murder people for their country – they are old enough to know their own mind and arrange for their own medical operations concerning their own gender identity. You hear such arguments less often in the less neoliberalized states.

Yesterday’s young, who were awake, suggested that it was wrong to travel abroad to murder people for your country, whether you were a child or not, whether you were conscripted or had volunteered. They wore flowers in their hair and dreamed of a future in which one day their grandchildren would walk hand in hand.

So much changed in such a short space of time. What was it that transformed the corrugated city to be so lopsided, especially in the homelands of the theorists? Perhaps it was the fastest international growth over time in income inequality being in the United States and United Kingdom? Maybe that lies behind this shift from anti-war protesting to arguing that being permitted to kill is a valid reason for a child determining for themselves whether to have a life-changing operation on their genitals?

It was only a small minority of the old that marched against war and cared so much about the 16th of March 1968 Mỹ Lai massacre. Did the marchers succeed? Do you know of that massacre?

It was just a minority of their children that rallied against growing inequalities in the United Kingdom and United States in the 1990s. They certainly failed. But do you know of their failure or was that just part of so many other battles, all of equal importance?

So, too, it is only a small minority of the young, of the grandchildren of the hippies, arguing that what they think of what lies directly beneath their own navels is one of the most important issues of the day – and it might be. The old often resort to saying it is too early to know.

The lopsided city is a city of growing grievances where the old among the affluent still worry that the pitchforks are coming for them, while their children complain that their parents simply do not understand their problems. All the while, the poor look up bemused, necks craned ever more painfully in the ever-shortening spaces of time they have, between jobs, to contemplate what is happening high up above them.

The poor say of those with power: ‘they are all the same’. Which is worth bearing in mind when thinking about the growing myriads of inequalities now widely recognised within rich families.

What do people argue about in multi-million-pound townhouses? What intersectionality of class, culture war and generational difference matters most to those who do not have to worry about hunger, heat or cold? In the lop-sided city, the debate within these palaces is amplified by what has come to be called social media, which is the platform little princes use to project their views.

You might take great offence at what you see as your right to exist being debated. However, if more and more of us princelings take offence at anything we see as infringing our chosen identities, we will end up spending much of the rest of our lives taking offence. Proclaiming our offence can ever so easily offend other little princes, so we start to dance with our words.

Grow up as an affluent child in the lopsided city and, as an adult, mention your concerns over the comments of others and you may be less aware than, less awake than, and less conscious than the children of the corrugated city are in how badly thoughts can land. Complain that you ‘do not have a right to exist’ because not everyone agrees with your ideas on gender identity, and you probably do not notice the wry smile of the old person whose parents and grandparents were denied their right to exist through the gas chambers. Soon, none of that generation and their memories will remain.