Danny Dorling's Blog, page 38

November 15, 2016

Let’s go back to the future with co-operative schools – and leave grammars in the past

Comprehensive schools have improved our lives. The evidence that they are better for our children and for all of us is overwhelming. Which is why 60 organisations, including the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, put their names to an open letter in October pleading for the ban on new grammar schools to remain. Why, then, in the face of overwhelming expert advice, do so many members of the public, some ministers, and the prime minister want to press ahead with more selective schools?

It is possible to select a subset of grammar schools and to suggest that the minority of children from poorer backgrounds who attend that small set do go on to get better GCSE results, but that does not provide evidence that the grammar school model is good in general. It also does not question the English orthodoxy that it is always better to get higher grades in exams. If all we needed was lots of people who were especially skilled at exam technique, it would be – but that is not what we lack as a country. We lack rounded adults with a wide range of skills who respect and understand each other’s abilities and contributions.

Introducing a grammar school into an area does not only harm schooling in that immediate district but also in neighbouring areas. Despite this, more people are in favour of creating new grammar schools (38%) than would be in favour of ending selection in those that still exist (23%). Among those who attended grammar schools themselves, 61% would like to see more built. It’s the old who are most in favour of selection.

The argument for grammar schools is similar to the argument for leaving the EU. It is about people wanting something better than they currently have, and believing that a return to the past will be an improvement and that “experts” are not to be believed. However it is also an argument against carrying on as we are, and against the rising inequality of recent decades that has resulted in selection by house price.

A Better Politics

Click here for a free low resolution PDF copy of the 2016 book: “A Better Politics”

November 12, 2016

A debate about social goods and social evils

Housing is fundamentally a debate about social goods and social evils – TAP blog 6, 11 November 2016

The provision of housing is a moral issue like the provision of food, fuel and water. That we should not be afraid of using the word “wicked” to describe the selfishness of an immoral minority who profess a moral superiority while profiting from the housing crisis.

We need to rekindle our understanding of kindness as our normal responsibility for each other in spirit and in law. A few people have grown very rich, in monetary terms if not in social standing. They have almost always done this by being greedy and having been allowed to be greedy.

A few more people have third and fourth homes. Millions of others pay far more to be housed than their parents did, often with less security of tenure and peace of mind, often more overcrowded, often in worse material condition, and increasingly beginning to understand that this is not due to immigrants (getting on their bikes!), or welfare cheats, or their own lack of entrepreneurial spirit – but because they are being ripped off by the immoral minority. When they come to cut first they come for the weakest.

Illustration by Joseph P Kelly

November 8, 2016

Schools as the driver of inequality – the ideas behind a talk given at the annual Class conference in London on November 5th 2016

On education the left need to recognise public disquiet over our current system of allocation to state schools by area and hence by housing price. Simply defending comprehensive schools is not enough. The publication of school league tables that started in the early 1990s led to small difference in outcome by schools being magnified into large differences by 2016.

Many of those parents who could afford “choice” brought homes or rented in areas where the schools were doing slightly better than average. Poorer families were priced out of the catchment areas of those schools and what had often started as a small difference grew into a chasm dividing some towns and cities up starkly.

Parents growing increasingly anxious about educational outcomes also helped fuel the speculative bubble in housing prices in the South East of England and further afield. One social problem leads to another. Not publishing school league tables would be too little on its own to reverse the harm that has been done and the spatial divides that have grown over time between our children.

Encouraging schools to compete with each other further exacerbated the problem along with academy and free schools. The left needs new ideas as radical as comprehensive education was when it was first envisaged. It needs to recognise how housing, growing economic inequality and education are linked, not just through who can live in each catchment area, but in the high turnover of young teachers in the south of England.

We need to begin to change how we govern our schools and amalgamate their management so that teachers can work on more than one school site and economies of scale can be used to make it more and more rational for upper middle class parents not to use the private sector. We need our universities to begin to compete less with each other and work more closely with the people of the cities they are based in. So how can we begin to achieve all this?

Look for the antecedent models that could become the mainstream of the future. Long before the comprehensive movement was a movement there were a few comprehensive schools. Similarly today, long before there is any movement for a more cooperative ethos to education in Britain, there are already 800 co-operative state schools in the UK up and running today. And they are beginning to organise regionally with more plans in place for extending this in 2017.

What we do not yet have is a model of cooperation in a large town or small city in which all of the state schools begin to work together in a way in which it begins to make less and less sense for parents to worry about the school catchment area they live in and less and less sense to not use the state system for those who could afford to go private.

Financial crisis are often a large part of the impetus for progressive social change. The National Health Service was partly introduced because the middle class could no longer afford a private doctor by the 1930s. Comprehensive schools were partly so popular in the 1970s because the middle could increasingly not afford to use the private sector for their children who failed the 11 plus.

Today we have a financial crisis. State schools may need, as of necessity, to begin to share resources more, science labs, language teachers, sports fields. Why not then share the same senior management team rather than having two teams? Why not make our cities safer to cycle around so that we are happier with the idea of secondary school children moving between different school sites or going to different sites on different days?

For all this to begin to work we need to begin to adopt a more cooperative model of education. We need to realise that the school which records the highest proportion of GCSE results in the city is not an “outstanding school”, but almost always the school with the most expensive catchment area. And we need to understand that children who are very good at passing exams are not necessarily extremely good at anything other than passing exams. Britain needs a well-rounded workforce in future, not a set of adults keenly trained at exam technique, or made to feel inadequate because they were always a problem for their school.

Those speaking (in speaker order) are: Carys Afoko, Faiza Shaheen, Holly Rigby and Danny Dorling (2016) Schools as the driver of inequality, Class: Centre for Labour and Social Studies, annual conference, TUC congress, London, November 5th

November 3, 2016

Leaving Reality: The UK and the rest of Europe

Economically, the financial crash of 2008 set UK society on a course that led to the 2016 EU referendum. Socially, the gaps between the haves, maybe-haves and have-not’s became wider in the UK than anywhere else in the EU. After 2015 the UK was more politically polarized than it had been since the aftermath of any election in the last 120 years. Geographically, the north-south divide continued to deepen as the country split between a London commuter-belt, and the Northern and Western archipelago of declining cities. It was life’s losers and the old who disproportionately voted to leave the EU in June 2016. Losers can be found everywhere, and can appear to be better-off than average, but they believed that in being part of the EU the UK had lost something. Because of differential turnout, a narrow majority of Leave voters lived in the South of England and most were middle class.

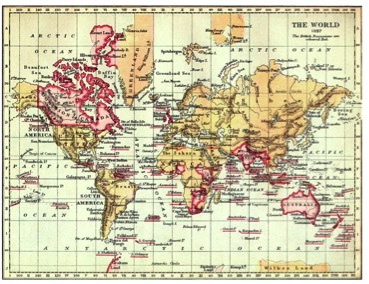

This lecture consider the antecedents to the vote: the rapid decline in living standards after 2010, failing health and rapidly rising mortality due to austerity. A majority of the electorate voted for something other than this. They did not vote for what they will get because no one knows what they will get. The UK fares unfavourably in relation to other large countries in the EU in terms of health, educational fairness, housing, income distribution and poverty. It was not the EU that made us less equal and which created so many of the social problems that result from growing inequality, an ignorant elite, and a state slowly adjusting to no longer being the once ‘great’ centre of an empire.

Danny Dorling giving the Annual John Hamilton Lifelong Learning Lecture, Centre for Lifelong Learning, University of Liverpool, October 14th 2016: “Leaving Reality: The UK and the rest of Europe”.

October 27, 2016

The price we pay for housing is too high

Since 2010 council tax benefit has been cut all across the UK, and rent, gas and electricity costs have gone up. A quarter of British households, mostly with children, can no longer pay for rent, fuel and food and manage to save at least £10 a month. As the pound falls energy costs and food prices rise, then the number of households living in poverty will rise. Relying on charities to help feed the poorest through food banks shows that this government views such activities—being able to live a decent life—as discretionary.

People will go without food and adequate heating before they fail to pay the rent. And yet in London, court summonses for not paying the rent doubled from 7,283 in 2013-14 to 15,509 in 2014-15, and there was a 50 per cent increase in the use of bailiffs. In the UK you pay for your own eviction: £125 in court costs and £400 in bailiff’s fees.

The wealth parade by Ella Furness

Over half a million children in London are now living in poverty. Most of their parents are now privately renting. When their families are evicted, or just move because they cannot afford the rising rents, the children also often have to move school, thus losing friends. Children in poverty and in private rented accommodation move, on average, more than once every three years. London’s recent amazing state school exam result improvement may well soon suffer.

Our government needs to accept its responsibility for the quality and security of rented housing and the quantity of socially rented housing, become involved in rent regulation and bring under control the frenzied buying of properties by buy-to-let landlords. The standard length of private rented tenure in the UK should be three years, or five years for people with, or who subsequently have, children. Rents should be fixed during this period. Social housing rents should not be more than 30 per cent of disposable income.

Tenants such as students could leave their tenancy earlier, but landlords could not insist that they do. Tenants should have the right to improve persistently substandard accommodation, deduct the cost from their rent, and extend the length of their tenancies in proportion to how much they have had to spend. That would ensure our housing stock was improved. Existing laws are simply not good enough.

read more of the ‘Public Sector Focus’ article this is an extract from

Or read the whole book that article was based on – A Better Politics – free low resolution PDF available here

October 25, 2016

Putting people at (and around) the centre of the city

An annual public lecture given by Danny Dorling generalizing from Oxford’s current housing dilemmas for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors and the Sustainable Urban Development Programme, 1 Parliament Square, London, October 24th.

Oxford can be seen as an example of what goes wrong when we do not plan well. In many ways it is now very like London and its problems are very much like those of a London borough, albeit one in which, at its centre are a series of very old buildings and a very old road layout that really cannot be altered very much. So how could a place like this be made better in future in a way that would help not only improve its housing, but also educational possibilities, tourism options and business?

I was born in the city of Oxford in 1968 and left in 1986. I returned, aged 45, to find a city transformed. The main shopping street had been pedestrianized. Cycle lanes had been painted on pavements. Most of the city is a 20mph zone. Many things get better – and they will get better again. It was often anarchists who suggested that such things were possible in the past and their ideas were ridiculed in the 1960s and 1970s. Later planners implemented them.

The city is also now full. It has built up to its greenbelt boundary. Compared to wages and salaries, rents and house prices have never been so high. Just as in London most people leave because they cannot afford to stay. Without wealth, or access to the depleted stock of social housing, a life in Oxford is no longer possible for someone who wants to start a family, unless at least one adult in their household is very highly paid or they inherit wealth.

Progress often takes a step back as the extreme unaffordability of cities such as Oxford and London currently demonstrates. New initiatives can also be bad initiatives, but these cities will be very different in the future, just as they were very different just a few decades ago. So what initiatives are needed if we are to protect the most valuable parts of the green belt and also provide better housing, health care and education. In this lecture the suggestion is made that the humble bike could be at the heart of what is needed, alongside better provision for walking. If people are to be put at the centre of our cities again then we need to make less space available for cars, including less pace on our roads. Read more here or listen below.

October 21, 2016

How much of you is you and how much of you is a product of your geography?

How much of you is you and how much of you is a product of your geography? Have a look at these maps. Areas are coloured red and dark red if many people are poor in those places. And they are coloured green, and especially dark green, if very few people are poor. These maps are produced from data that comes from government, and the government now has very good data. They know at an individual level who is claiming what benefits because their income is too little for them to live on.

We’re starting off around Hay, Hay-on-Wye, and it is much-of-a-muchness. You can’t see very much around here, mainly because there are so few people. There are some very big houses round here, and some very small houses; but because there aren’t enough people we can’t really say much about the areas. So zoom out, zoom out and pan across a bit. Have a look at Hereford. Suddenly you can see the divisions, you can see the poorer parts of Hereford and the richer parts, and you can see how they are separated. But move out again, look at Gloucester, look at Bristol. You get the same pattern in almost every town in Britain. The same division between rich and poor areas.

Look across at the whole country. Everywhere is like this, but some places are more divided than others. So zoom into London, because in London you can see the starkest divides within the entire country. And then zoom into the very centre of London. In the very centre of London you’ll see the greatest concentrations of poverty, and some of the greatest concentrations of wealth. And if you are born in, or grow up in, or move to some of these areas, you are most likely poor. But if you are born in, or grow up in, or move to the green areas, you will be growing up in a very different environment and you’ll see very different things and you’ll mix with very different people.

If you look out at the country as a whole and you look at the villages between the cities, the villages between London and Reading, between Reading and Bristol, between Bristol and Gloucester, and between Gloucester and Hereford, then often you’ll see that they are almost all coloured green. So if you grow up in these places today you won’t see the lives that are so typical of so many people in Britain.

So what are you are product of? Is it all about you? Or are you a result of where you have come from? It matters because this country is the most divided country in Europe. Best of luck with you A levels – although the extent to which you might rely on that luck – will also depend very much on where, as well as who, you are.

Danny Dorling speaking on ‘Hay Levels’ on examining the geodemographics of the UK, using maps created by Oliver O’Brien (UCL, CASA) in 2012 and updated in 2015. You can further explore the maps here. Video recorded in Hay on Wye in May 2016.

October 19, 2016

Working for service – not profit

Invited Student Lecture given by Danny Dorling at Ruskin College, Oxford, October 19th, 2016, Introduced by Parveen Alam.

We could talk about health care:

We are currently experiencing the worse health and social care crisis the UK has faced at any time since 1940. Mortality rates of elderly people are rising across the UK. The older you are, and the frailer you are, the worse off you now are as compared to 2010. Very soon we will begin to see the release of data showing that David Cameron was the first post-war British Prime Minster to govern the UK in such a way that life expectancies fell under his watch. A small influenza outbreak in 2015 played a minor part in the rise in deaths. The major part was the result of the post 2010 cuts in health and especially social care funding across the UK.

Or we could talk about housing:

The housing crisis is resulting in a return to mass private renting with almost no protection of tenants’ rights and little understanding of what rights tenants should have. This has resulted in the rise in private renting becoming the main reason more families are becoming homeless, because they are evicted when their landlord raises the rent and they cannot pay it. The numbers of people and families renting privately is rising at an exponential rate. If good rent regulation were introduced that rise would be slowed down and existing tenants would be better protected. The housing market is current highly precarious, partly as a result of landlords speculating on through their property ‘investments’.

But let’s talk mostly about education today…

And begin with a letter in the Guardian: ‘The intellectual and political case for selection has collapsed. So it is now appropriate to ask how the continuation of existing selection arrangements – in 163 grammar schools and a number of selective authorities – can be defended. It has been demonstrated beyond argument that less able children do worse and able children do no better in selective areas compared to non-selective ones, and it is almost always “ordinary, working-class children” who lose out.’

However, that is often as far as we go. We need to begin asking whether that alone is enough or whether we need to be much more imaginative rather than simply attacking attempts to return us to the past – so let’s talk about what a better future might look like and how the balance between service and profit should be altered if we are to achieve that better future.

October 18, 2016

Capitalism on Trial: Rising economic inequality and stalled progress in educational reform in the UK

A thirty minute talk for lower sixth form students studying A levels by Danny Dorling of the University of Oxford, School of Geography & Environment given at 12.30pm on Monday 17th October, 2016 at Eton College, Windsor. Covering issues involving Europe, Brexit, the financial crash, state verses private spending and the future of education and inequality in the UK.

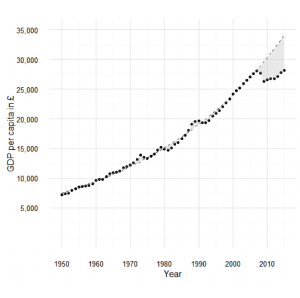

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in the UK 1950-2015

October 14, 2016

Geography is where it’s at – and about the future

A talk for sixth form students at many schools studying A level Geography in Manchester by Danny Dorling of the University of Oxford, School of Geography & Environment given at 4.30pm on Thursday 13th October, 2016 at Loreto Sixth Form College, Manchester. What a university lecture can be like and why university is so different to school.

Map of the British Empire in 1897

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers