Danny Dorling's Blog, page 32

December 22, 2017

120,000 additional premature deaths in the UK 2010-2017

On Thursday 16th November 2017 the Journal BMJ Open published an article which concluded that severe public spending cuts in the UK had contributed to causing 120,000 additional premature deaths between 2010 and 2017. The article was put together by ten researchers who worked at Kings College, UCL and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; at the Medical sciences division in Oxford, at the University of Cambridge and in the Philippines.

We had known for some time that austerity was bringing deaths forward, but not that the rate of death associated with the cuts was rising so rapidly. The large majority of deaths associated with austerity had taken place in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Only a third had occurred between 2012 and 2014 and almost none in 2010 or 2011 when austerity was just beginning. There was a dose response relationship. The greater the austerity and cuts to services the more people died earlier than they otherwise would have. Most of these additional premature were of elderly people, but far from all of them.

Life expectancy flat-lined after 2010. It had be rising at a remarkably steady rate before then. After 2010 it barely rose by a month a year for men and just two weeks for women when Cameron was in power, possibly less around when May took over. The latest figures, published in September 2017 were for the period 2014-2016. Women can now expect to live 83.06 years and men 79.40 years. For the first time in over a century the health of people in England and Wales as measured by the most important consideration has stopped improving.

read more in Public Sector Focus

The graphs below show when people in the UK first began to say that their health was declining:

Trends in UK self-reported health

December 19, 2017

England’s embarrassing tuition fees

As pay scandals continue to embarrass British higher education, with university chiefs receiving eye-watering salaries and golden handshakes, it’s time to ask: why can’t we be more like Germany?

A scandal erupted there a few years ago when the vice-chancellor of Cologne University increased his salary from €78,876 (£69,403) a year in 2006 to €133,781 in 2012. In 2014 a table revealing this was leaked, prompting outrage. Since then top salaries in German universities have been held in check. Germany is far from perfect, but we can only wish we had its problems.

Vice-chancellors’ pay has soared since the introduction of £9,000 annual tuition fees in England, and significant fees throughout the UK, except for Scottish students studying in Scotland. Meanwhile, in Germany, where universities are supported through general taxation and there are no fees, vice-chancellors seem to survive on relatively modest remuneration. Globally, the US has the highest senior pay levels in universities – and a large student debt bubble. As in Britain, the richest students in America do not take out loans; instead their parents pay up front. Is this a system to emulate?

In 1995 some 732,000 babies were born in the UK and 765,000 in Germany – just 33,000 more. And yet 21 years later, in 2016, in Britain there were 2.28 million students at higher education institutions, of whom 1.75 million were undergraduates. In Germany in 2016 there were 2.81 million students – 530,000 more than in the UK. Of these German students, 1.78 million were at traditional universities and another 0.96 million at universities of applied sciences. The number of German students rose by almost a million in the 20 years to 2016.

Read a longer and fully referenced version.

Why Demography Matters?

December 15, 2017

Updating Edwin Chadwick’s seminal work on geographical inequalities by occupation

Researchers at the Universities of Liverpool, Oxford and Glasgow revisited a study carried out 175 years ago which compared the health and life expectancy of people in different parts of the United Kingdom, including Liverpool, to see if its findings still held true.

They found that stark differences still exist and that people living in Liverpool still had lower life expectancy than those living in the rural area of Rutland.

The original study into sanitation conditions by Edwin Chadwick in 1842 charted the average age by death and by occupational group for five areas in the UK — Liverpool, Leeds, Manchester, Bolton and Rutland, a rural county in Eastern England.

The findings revealed a strong correlation between where you lived, what your job was and the age you lived to. This was the first study to demonstrate the huge geographical differences in health and life circumstances. It showed that a labourer in Rutland could expect to live a longer life than a professional tradesman in Liverpool.

The research, led by the Liverpool University’s Department of Geography & Planning undertook a similar analysis using data from the Office of National Statistics and the 2011 census to see if the same pattern still persisted.

The researchers found that whilst the level of inequality wasn’t on the scale it had been between the two areas in 1842, individuals in the middle social class bracket in Rutland still lived longer than those in the highest social class in Liverpool.

Dr Mark Green, who led the study, said: “On the 175th anniversary of this report, which was ground-breaking at the time, we wanted to see if in the 21st century your geography — that is where you live — still determined your health and life expectancy.”

“We found that whilst life expectancy has nearly doubled since Chadwick’s report, there is still a link between where you live, your social class and how long you live to.”

“It is remarkable that after 175 years, mortality rates in Liverpool are still higher than in Rutland within each occupational group. What this demonstrates is that living in certain locations offers very different life chances and health outcomes for people within the same occupational groups.”

read more about this study here

Or listen to a talk about where how you live matters for how long you might live as this varies across Europe today:

December 3, 2017

The rich, poor and the earth

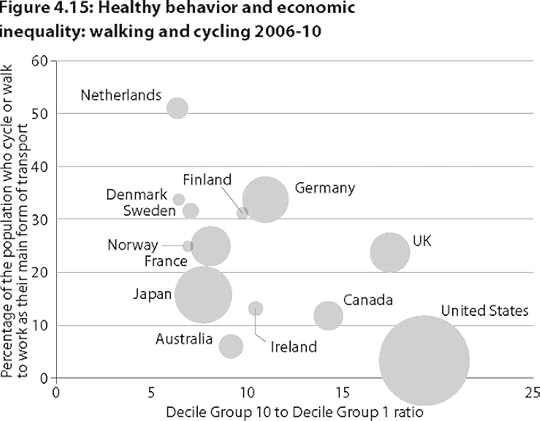

The most important benefit of the equality effect may be that it leads us to behave in ways that are less environmentally damaging. The evidence for this is only emerging now. We can track the effect across a range of indicators by looking at the 25 richest countries in the world, which have varying levels of inequality. Sometimes comparable data does not exist for all of these countries and we have to consider just a subset, as is the case when looking at the proportion who cycle or walk to work everyday in each country:

Relationship between income inequality and walking and cycling to work

The measure of inequality used here is the ratio between the incomes of the best-off 10 per cent of households and those of the worst-off 10 per cent. It is clear that some rich countries are substantially more unequal than others, ranging from the most unequal – the US – to the most equal – Denmark. So what is the environmental effect of living in a country in which households are economically unequal as compared to living in one in which the economic differences are far smaller? The book from which this article is drawn is able to track the effect in detail across 11 different indicators.

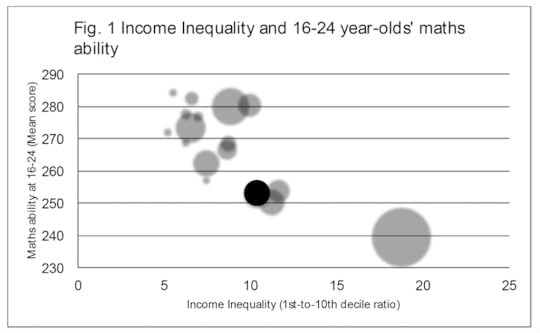

Economic inequality is now being found to be linked to more and more damaging effects, ranging from high pollution to lower education attainment, especially in mathematics and problem solving. People in more economically unequal countries find it much harder to solve not just mathematical puzzles but also how to better organise their societies.

Maths ability for those aged 16 to 24 in 2012

Or read more about the equality effect in general.

November 29, 2017

The latest population projections for Britain suggest a million years of life could disappear by 2058. Why?

Buried deep in a note towards the end of a recent bulletin published by the British government’s statistical agency was a startling revelation. On average, people in the UK are now projected to live shorter lives than previously thought.

In their projections, published in October 2017, statisticians at the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimated that by 2041, life expectancy for women would be 86.2 years and 83.4 years for men. In both cases, that’s almost a whole year less than had been projected just two years earlier. And the statisticians said life expectancy would only continue to creep upwards in future.

As a result, and looking further ahead, a further one million earlier deaths are now projected to happen across the UK in the next 40 years by 2058. This number was not highlighted in the report. But it jumped out at us when we analysed the tables of projections published alongside it.

It means that the 110 years of steadily improving life expectancy in the UK are now officially over. The implications for this are huge and the reasons the statistics were revised is a tragedy on an enormous scale.

…

The stagnation in life expectancy is no longer being treated as a “blip”. It is now projected to be the new norm. But the ONS does not explicitly state this in its projections for the future. To calculate the figure of a million lives lost you have to subtract all the future deaths now predicted in the 2017 report, which was based on data from 2016, from those projected two years ago, based on a 2014 projection.

Every year up until at least the year 2084, people across the UK are now expected to die earlier. Already in the 12 months between July 2016 and June 2017, we calculated that an additional 39,307 more people have died than were expected to die under the previous projections. Over a third, or 13,440, of those additional deaths have been of women aged 80 or more who are now dying earlier than was expected. But 7% of these extra deaths in 2016-17 were of people aged between 20 and 60: almost 2,000 more younger men and 1,000 more younger women in this age group have died than would have if progress had not stalled. So whatever is happening is affecting young people too.

The projection that there will be a million extra deaths by 2058 is not due to the fact that there will simply be more people living in the UK in the future. By contrast, the ONS now projects less inward migration. The million extra early deaths are not due to more expected births: the ONS now projects lower birth rates. The extra million early deaths are simply the result of mortality rates either having risen or having stalled in recent years. The ONS now considers that this will have a serious impact on life expectancy in the UK and population numbers for decades to come.

If you are in your forties or fifties and live in the UK this is mostly about you. Almost all of the million people now projected to die earlier than before – well over four-fifths of them – will be people who are currently in this age group: 411,000 women and 404,000 men aged between 40 and 60. Child, infant mortality and still births have also not improved recently – and again this has recently been linked to under-funding resulting in under-staffing in the NHS.

It easy to dismiss these statistics with remarks such as: “people live too long nowadays anyway” and: “I wouldn’t want to live that long”. But older people are important and grandparents are often a formative part of a child’s life. Because many people in the UK are now having children at older ages, this will translate into more people not seeing their grandchildren grow up. But, above that, longer, healthier lives have been the most important marker of social progress in Britain for well over a century. And now, for the first time in a century, we are no longer expected to see the rates of improvement we have become used to.

And on how demography need not be destiny see (also published November 2017):

Why Demography Matters?

Why Budget 2017 did so little to help students

One week ago today, on Wednesday 22 November 2017, the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, gave a budget speech that was designed to confuse and distract. It was peppered with claims for which the opposite was actually the case. These were inserted to annoy wonks who have an understanding of statistics and to mislead everyone else. For instance, in his speech, Hammond claimed that in the UK ‘today, income inequality is at its lowest level in 30 years.’

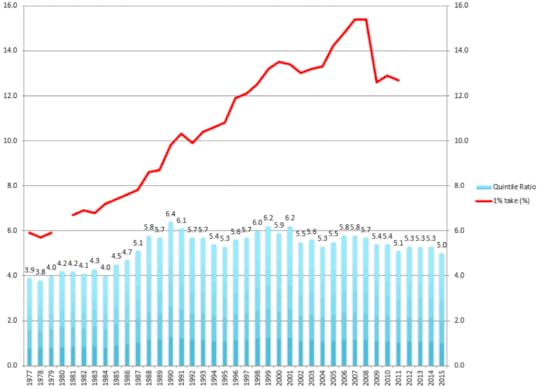

Now, it is true that there is one very bad measure of income inequality that can be used to defend that statement. It is the measure that ignores the entire incomes of the best-off tenth, and the worst-off tenth of the population. It is the measure I used as the first graph in my most recent book to illustrate how in recent years the government has used smoke and mirrors, assuming nobody will uncover the truth and question their statements about inequality.

Fig. 1: UK household income inequality, quintile ratio 1977-2016, 1% take 1977-2012

It is the ratio of the median incomes of the highest and lowest quintiles, shown by the blue bars in the chart above. The red line illustrates why saying that inequality is at its lowest level for 30 years is so misleading, unless you do not consider the best-off 1%, or even best-off 10% (and worst off 10%) as part of society. The red line shows the share of the total income taken each year by the best-off 1%.

So, why would a Chancellor and his advisors place such a claim so brazenly in a budget speech? The answer is that they would like attention drawn to it. They are not stupid. They must know it will be questioned. This is called misdirection. What they really don’t want attention drawn to is what was most important about the speech – everything that was not in it – all the sins of omission. This article is about one of those sins.

Almost inaudible praise

Universities are mentioned just twice by the Chancellor. Once, when they are somewhat slighted in relation to the ‘commercial development labs of our great companies’ and second, in how Hammond aims to capitalise on ‘the global reputations of our two most famous universities’. For those as old as Philip Hammond and me, this is reminiscent of a joke in the 1970s series ‘Yes Minister’. The Minister in question worries that ‘we must do something for the universities’ and his permanent secretary, Sir Humphrey, replies soothingly ‘of course minister, both of them’.

It is sad when national budgets become a mixture of half-truths and bad jokes. What the Budget should have announced was the beginning of the end of tuition fees and student loans, or at least a significant change to them. But Philip Hammond and his colleagues appear to like the student loan system as it is, with November’s budget giving only small hints and little tangible evidence of the promised “major review” that government hinted at this summer amounting to much in reality.

Tinkering won’t work

Returning to the Budget, Philip Hammond is often portrayed as a boring person – ‘spreadsheet Phil’ or an ‘economic Eyeore’. At least Hammond did not announce new cuts to university budgets for government spending (with the two-year freeze on fees already known), but he also doesn’t like talking about student loans, or tuition fees – as is evident from his budget speech.

Nothing was mentioned in the Budget about student loans. In fact, students were not mentioned at all other than that Hammond wants a few extra computer science teachers in schools, at some point in the unspecified future. In the small print of the Budget’s supporting documents there is a promise to stop charging graduates more than they actually owe once they have paid the loan off – due to the currently archaic and faulty system – but that was known about before the Budget.

Opposition to student loans is growing. The system allows rich families to pay many billions of pounds less tax overall. This is as compared to what the rich pay in more equitable countries, where such loans do not exist and where university tuition fees are either very low or not charged at all. By contrast, the richest students in England do not use the current student loans system at all. The existing system is also defended most loudly by some of the wealthiest and best-paid people in our society.

November 28, 2017

Health – why the Conservatives have the worst record since at least 1891

London, November 2017: Research linking cuts in government health spending to higher mortality rates in England has been published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ Open). Ten leading medical researchers from universities including Oxford, Cambridge, and UCL found that spending cuts, in particular cuts to public expenditure on social care were associated with 120,000 excess deaths estimated to have occurred in England between 2010 and 2017.

Professor Lawrence King, who contributed to the study, said: “It is now very clear that austerity does not promote growth or reduce deficits — it is bad economics, but good class politics. This study shows it is also a public health disaster. It is not an exaggeration to call it economic murder.”

Simon Wren-Lewis, an economist later commenting on the study explained: “It is one thing for economists like me to say that austerity has cost each household at least £4,000: this can be dismissed with ‘what do economists know’? But when doctors say the policy has led to premature deaths, that is something else.”

The findings published in the British Medical Journal align almost perfectly with earlier findings derived from studying the differences between two sets of Office for National Statistics Projections which show not only how many more people have already died earlier than were expected to die in recent years but also that in future many more earlier deaths are now expected due to the faltering government record on health.

To date the stalling of improvements in overall life expectancy, the recent rapid increase in poor health of the population, and the very poor recent improvements in the infant and child health record across the UK, are now convincingly linked to austerity. There is no other plausible explanation. Today, when national life tables are compared, the Conservatives now have the worst record in progress in health since at least 1891.

A talk on all these very recent developments given in Oxford on November 27th:

November 21, 2017

The chancellor must end austerity now – it is punishing an entire generation

Alongside the human costs, cuts have hurt our economy, and we’ve now reached a dangerous tipping point, say Joseph Stiglitz, Ha-Joon Chang and 111 others

Letters, The Guardian, 19 November 2017, GMT

Seven years of austerity has destroyed lives. An estimated 30,000 excess deaths can be linked to cuts in NHS spending and the social care crisis in 2015 alone. The number of food parcels given to impoverished Britons has grown from tens of thousands in 2010 to over a million.

Children are suffering from real-terms spending cuts in up to 88% of schools. The public sector pay cap has meant that millions of workers are struggling to make ends meet.

Alongside the mounting human costs, austerity has hurt our economy. The UK has experienced its weakest recovery on record and suffers from poor levels of investment, leading to low productivity and falling wages. This government has missed every one of its own debt reduction targets because austerity simply doesn’t work.

The case for cuts has been grounded in ideology and untruths. We’ve been told public debt is the outcome of overspending on public services rather than bailing out the banks. We’ve been told that while the government can find money for the DUP, we cannot afford investment in public services and infrastructure. We’ve been told that unless we “tighten our belts” we’ll saddle future generations with debt – but it’s the onslaught of cuts that is punishing an entire generation.

Given the unprecedented economic uncertainty posed by Brexit negotiations and the private sector’s failure to invest, we cannot risk exacerbating an already anaemic recovery with further public spending cuts. We’ve reached a dangerous tipping point. Austerity has failed the British people and the British economy. We demand the chancellor ends austerity now.

Joseph Stiglitz Professor, Columbia University

Ha-Joon Chang Professor, University of Cambridge

David Graeber Professor of anthropology, LSE

Ann Pettifor Director, Prime Economics

Danny Dorling Professor, University of Oxford

Saskia Sassen Professor, Columbia University

Sir Richard Jolly Emeritus professor, Institute of Development Studies

Mike Savage Co-director of International Inequalities Institute, London School of Economics

David Blanchflower Professor of economics, Dartmouth College

Richard Murphy Director of Tax Research UK, University of London

Kate Pickett Professor of epidemiology, University of York

Richard G Wilkinson Emeritus professor of public health, University of Nottingham

Beverley Skeggs Academic director of International Inequalities Institute Atlantic fellows programme, LSE

Diane Elson Emeritus professor, University of Essex

Frances Stewart Director for research on inequality, human security and ethnicity, University of Oxford

Simon Wren-Lewis Professor of economic policy, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Malcolm Sawyer Emeritus professor of economics, University of Leeds

Victoria Chick Emeritus professor of economics, University College London

John Weeks Emeritus professor of economics, Soas

Gurminder Bhambra Professor of sociology, Warwick University

Jason Hickel Department of anthropology, Goldsmiths University of London

Özlem Onaran Department of international business and economics, University of Greenwich

Howard Reed Director, Landman Economics

Valpy FitzGerald Emeritus professor of international development finance, University of Oxford

Ruth Pearson Emeritus professor, University of Leeds

Len McCluskey General secretary, Unite

David Prentis General secretary, Unison

Tim Roache General secretary, GMB

Mark Serwotka General secretary, PCS

Manuel Cortes General secretary, TSSA

Sally Hunt General Secretary, UCU

Kevin Courtney Co-general secretary, NEU

Mary Bousted Co-general secretary, NEU

Ronnie Draper General secretary, BFAWU

Horace Trubridge General secretary, MU

Dave Ward General secretary, CWU

Mick Whelan General secretary, Aslef

Doug Nicholls General secretary, General Federation of Trade Unions

Matt Wrack General secretary, Fire Brigade’s Union

Shakira Martin General secretary, NUS

Janet Davies General secretary, Royal College of Nurses

Radical Housing Network

UK Uncut

Sam Tarry President, Class

Faiza Shaheen Director, CLASS

Omar Khan Director, Runnymede Trust

Mary-Ann Stephenson Co-director, Women’s Budget Group

David Hillman Chair, Robin Hood Tax

Asad Rehman Director, War on Want

Sarah-Jayne Clifton Director, Jubilee Debt Campaign

Sam Fairbairn National secretary, People’s Assembly Against Austerity

Linda Burnip Founder, Disabled People against Cuts

Fran Boait Executive director, Positive Money

Will Snell Director, Tax Justice UK

Miatta Fahnbulleh Chief executive, New Economics Foundation

Kayleigh Garthwaite Fellow, department of social policy, sociology and criminology, University of Birmingham

Ruth Patrick Postdoctoral researcher, School of Law and Social Justice, University of Liverpool

Tracey Jensen Lecturer in media and cultural studies, Lancaster University

Stewart Lansley Visiting fellow, Bristol University

Andrew Cumbers Professor, Adam Smith Business School

Prem Sikka Professor of accounting, University of Essex

Christine Cooper Professor of accounting and finance, University of Strathclyde

Jo Michell Associate professor of economics, UWE Bristol

David Spencer Professor of economics and political economy, University of Leeds

Alfredo Saad-Filho Professor, Soas

Simon Reid-Henry Reader in geography, Queen Mary University of London

Mary Mellor Emeritus professor, Northumbria University

Hugh Willmott Professor of management, University of London

Steve Keen Professor of economics, Kingston University London

Susan Himmelweit Emeritus professor of economics, Open University

Gideon Calder Senior lecturer in public health, policy and social sciences, Swansea University

Simon Mohun Emeritus professor of political economy, Queen Mary University of London

Klaus Nielsen Professor of institutional economics, Birkbeck University of London

Pritam Singh Professor of economics, Oxford Brookes Business School

Matthew Watson Professor of political economy, University of Warwick

Mary V Wrenn Professor, UWE Bristol

Geoffrey Hodgson Research professor of business studies, University of Hertfordshire

Daniela Gabor Professor of economics and macro-finance, UWE Bristol

Gary Dymski Professor of applied economics, Leeds University Business School

Tony Thirlwall Professor of applied economics, University of Kent

Kalim Siddiqui Senior lecturer, University of Huddersfield

Stuart Holland Economist, University of Coimbra

David Bailey Professor of industrial strategy, Aston Business School

Roberto Veneziani School of Economics and Finance, Queen Mary University of London

Neil Lancastle Director of Finance and Banking Research Centre, De Montfort University

Michael Lipton Research professor of economics, University of Sussex

Marjorie Mayo Emeritus professor of community development, Goldsmiths

Andrew Simms Fellow, New Economics Foundation

Leslie Huckfield Academic and activist, Yunus Centre for Social Business and Health

Hugo Radice Economist, University of Leeds

Satoshi Miyamura Senior lecturer, Soas

Sue Konzelmann Director of the London Centre for Corporate Governance and Ethics, Birkbeck University of London

Bruce Conin Professor of economic sociology, University of Greenwich

David Hall Professor, public services international research unit, University of Greenwich

Jonathan Perraton Senior lecturer in economics, University of Sheffield

Teddy Brett Professor of international development, LSE

Robert Calvert Jump Lecturer, UWE Bristol

Jeff Powell Senior lecturer in economics, University of Greenwich

Kat Chzhen Academic, co-editor of Children of Austerity

Dominic Harrison Visiting professor of public health, University of Central Lancashire

Lisa McKenzie Lecturer in sociological practice, Middlesex University

Satbir Singh Chief executive, Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants

Costas Lapavitsas Professor, Soas

Engelbert Stockhammer Professor, Kingston University London

Annette Hastings Professor of urban studies, University of Glasgow

Ruth Lupton Professor of education, University of Manchester

Kitty Stewart Associate professor of social policy, LSE

Canon Giles Fraser Parish priest, St Mary’s Newington

Anna Minton Programme leader MRes architecture: Reading the Neoliberal City, University of East London

Sam Friedman Associate professor of sociology, LSE

Pilgrim Tucker Community organiser, Grenfell Action Group

Canon Steve Saxby Chair, Unite Faith Workers

Paul Parker Recording clerk, Quakers in Britain

Click here for pdf and link to the Guardian Newspaper where the letter was published

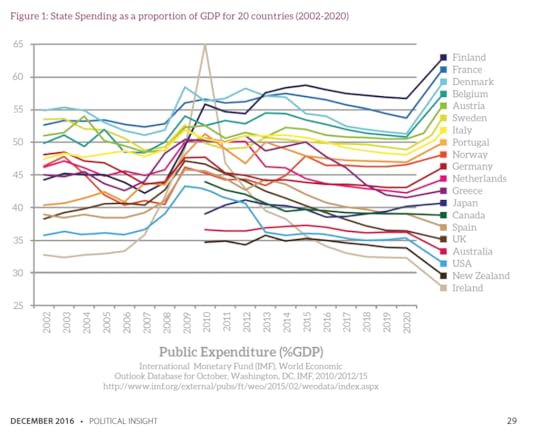

State Spending as a proportion of GDP for 20 countries, IMF estimates and projections

November 17, 2017

Lessons from more equitable European countries: Rent Regulation

Almost all European countries both have lower income inequality than the UK and also ensure by law that tenants who rent their homes enjoy much longer tenancies. To be able to do this, they have to give tenants a degree of certainty about how much rents can rise during the time they live in a property; otherwise the landlord can easily evict them simply by raising the rent. This is why rent regulation is so important. It is the only defence against arbitrary eviction.

■ In Germany half of all householders rent privately. Often they are renting via very standard long-term leases. This compares to standard tenancy agreements in the UK that at most give you a right to stay for the first 12 months and then allow your landlord to evict you at just two months’ notice. Rents are also not permitted to rise at all quickly. Tenants’ groups organize to complain when landlords are not penalized for breaking the law.

■ In Sweden private-sector rent levels are set through negotiations between representatives of landlords and tenants in a very similar way to how trade unions and employers negotiate over pay levels. The rent caps do not cause shortages, just as not having rent caps in the UK doesn’t result in a great increase in the supply of high-quality rental housing at reasonable cost.

■ In the Netherlands government officials inspect for quality and then fix the rents permitted. The factors involved in assessing quality include the amount of space both inside and outside the property and the quality of the building, such as whether it has double-glazing. Location is not a factor in assessing quality. For prime properties that are large, well built and also very well maintained by the landlord, no rent regulation is imposed.

■ Denmark has various forms of rent regulation. This is one of the reasons why children in Denmark fare so well relative to children in most other affluent countries. Denmark also does not suffer homelessness on the scale of countries with a supposedly more ‘free market’. ‘Free’ housing markets merely give a free rein to those with most money.

■ In France a new set of rent regulations came into force in the capital, Paris, in August 2015. These regulations state that private rents ‘must be no more than 20 per cent above or 30 per cent below the median rental price for the area.

The evidence from more unequal countries such as the UK and USA is clear: being able to charge whatever you like does not result in enough housing being made available.

This is an edited extract from Danny Dorling’s 2017 Book: The Equality Effect: Improving Life for Everyone, Oxford: New Internationalist, which can be consulted to see all the references to these claims and for references to many others’ work.

Read the original article as a PDF

November 10, 2017

Short Cuts – future life expectancy in the UK

Life expectancy for women in the UK is now lower than in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Men do little better.

In almost every other affluent country, apart from the US, people live longer than in the UK, often several years longer and the best countries are pulling away.

Between 2011 and 2015 life expectancy rose by a year in both Norway and Finland. It rose by more than a year in Japan, despite the Japanese already having the highest life expectancy in the world.It hardly rose at all in the UK. Why?

In the UK official projections have now been altered because of the tens of thousands of people who have died earlier than expected. If you subtract the latest ONS figures from the figures published two years ago, you can see that a further one million earlier deaths are now projected in the next forty years (the ONS itself doesn’t publish this number – it is shown in the table below).

Extra deaths now projected to occur every year in the UK from 2016 to 2058, by ONS

2016-based projection as compared to the 2014-based projection

— Extra — Cumulative — Time Period

—- Deaths —- Total

39,307 — 39,307 — 2016 – 2017

25,668 — 64,975 — 2017 – 2018

27,246 — 92,221 — 2018 – 2019

28,521 — 120,742 — 2019 – 2020

29,581 — 150,323 — 2020 – 2021

307,031 — 457,354 — 2021-2030 (ten years)

246,302 — 703,656 — 2031-2040 (ten tears)

178,483 — 882,139 — 2041-2050 (ten years)

17,310 — 882,139 — 2050 – 2051

17,463 — 899,602 — 2051 – 2052

17,582 — 917,184 — 2052 – 2053

17,650 — 934,834 — 2053 – 2054

17,600 — 952,434 — 2054 – 2055

17,404 — 969,838 — 2055 – 2056

17,050 — 986,888 — 2056 – 2057

16,524 — 1,003,412 — 2057 – 2058

Source – calculated directly from ONS tables of expected deaths by age and year

What has happened is no longer being treated as a temporary decline; it is the new norm. On 26 October 2017 the Office for National Statistics announced that it estimates that, by 2041, life expectancy for women will be 86.2 years and for men 83.4. Both figures are almost a whole year lower than last projected, then based on 2014 data.

In future people living in the UK are no longer projected to live as long as we thought would be the case just a few years ago. Tens of thousands more people have died earlier recently than were expected to die and this has lead to the national population projections being revised downwards.

The most plausible explanation would blame the politics of austerity, which has had an excessive impact on the poor and the elderly; the withdrawal of care support to half a million elderly people that had taken place by 2013; the effect of a million fewer social care visits being carried out every year; the cuts to NHS budgets and its reorganisation as a result of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act; increased rates of bankruptcy and general decline in the quality of care homes; the rise in fuel poverty among the old; cuts to or removal of disability benefits. The stalling of life expectancy was the result of political choice.

But the decline can be prevented from continuing for the next forty years. It does not have to continue as currently projected. Given that it is now clear that the cause was not some outside event, such as an influenza epidemic, we should ask why government continues to chose to ignore this worsening trend? Why is it of not interest to them?

Read more in the Lonodn Review of Books, and a fully referenced version of that article here

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers